Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Psychology in Society

On-line version ISSN 2309-8708

Print version ISSN 1015-6046

PINS n.42 Stellenbosch Jan. 2011

Does belonging matter?: Exploring the role of social connectedness as a critical factor in students' transition to higher education

June PymI; Suki GoodmanII; Natasha PatsikaIII

IEducation Development Unit (Commerce) University of Cape Town Rondebosch June.Pym@uct.ac.za

IIOrganisational Psychology University of Cape Town Rondebosch Suki.Goodman@uct.ac.za

IIIOrganisational Psychology University of Cape Town Rondebosch Natasha.patsika@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Widening access to Higher Education throughout the world has meant an increase in the number of students who do not necessarily have the types of capital that universities require. This means an increasing need to engage with the issues that separate students from connecting with their modes and places of learning. This paper describes a successful Academic Development programme that is focused on equity students in the Commerce Faculty at the University of Cape Town (South Africa). The programme actively promotes academic and affective factors that will contribute toward affirming students' identity and developing a learning community. The paper reports on the results of a research project that combined qualitative and quantitative research methods to investigate how fostering social connectedness impacts on the transition of students to higher education and their academic performance.

Keywords: Social connectedness, sense of belonging, transition to higher education, academic performance.

1. INTRODUCTION.

Widening access to Higher Education throughout the world has meant in increase in the number of students who do not necessarily have the types of capital that universities require. This means an increasing need to engage with the issues that separate students from connecting with their modes and places of learning. Equally the increasing size and anonymity of the large learning environment also militate against promoting student involvement and development (MacGregor, Cooper, Smith, & Robinson, 2000). A variety of theorists (Piaget, 1952; Perry, 1970; Vygotsky, 1978; Gilligan, 1982; Belenky et al, 1986) focus on the importance of social interaction as a way of developing higher-order thinking skills and providing a strong psychological support to engage with the often threatening environment in higher education learning.

Higher Education in South Africa is presently in a stage of transformation and under pressure to provide increased access, quality education and improved graduation rates. Research by Scott et al (2007) shows that in the 20-25 age group, the White participation rate (60%) is five times higher than Black students' participation (12%). The low graduation rate of 35% of all first-time entering students in the 2005 national cohort in a five-year period is an indicator that the Higher Education sector is performing poorly. However, a specific focus on admissions and throughput rates can lead to an abstraction from the concrete conditions that should be transformed so that redress of the imbalances caused by the Apartheid system can be achieved.

There has been a range of studies exploring what impacts on students' academic success or failure at tertiary level in South Africa. This includes rote learning at school-level; poor career guidance, language of instruction, financial and economic issues (Springer et al, 1999; Stanne & Donovan, 1999; Walton & Cohen, 2007; Chen & Lin, 2008; Peterson, Louw & Dumont, 2009). Sixteen years into the new South Africa, the structural barriers for black students are still considerable, despite the existence of Academic Development (AD) programmes. These programmes cater for students who are admitted on the basis of equity1 considerations. In probing what makes a difference to students' success a range of factors come into play, and there is clearly a relationship between school leaving grades and a variety of university entrance tests and academic success. However, there has been little exploration in relation to a range of socio-cultural and psychological factors that could impact on academic performance.

This paper describes a successful Academic Development (AD) programme in the Commerce Faculty at the University of Cape Town (UCT) that has moved away from a deficit model toward a programme which has a broad focus with multiple dimensions, and works at various levels that impact to change practices in the faculty. The programme has managed to achieve a far better graduation rate in recent years by moving towards a flexible, value-added model that focuses on harnessing students' agency and actively nurturing their social connectedness and sense of community.

Drawing on social theorists Vygotsky (1978), Gee (1990) and Bourdieu (2002), AD in this context has focused on academic life as a form of social practice by providing a range of engagements and interactive learning experiences. This paper outlines the work of the AD programme and then explores how developing and nurturing social connectedness impacts on the academic performance of undergraduate students within the context of an AD programme.

The paper reports on research that combines qualitative and quantitative enquiry. The quantitative analysis provides some tentative generalised findings and identifies patterns regarding the relationships between social connectedness and academic performance. The qualitative component provides more nuanced and detailed data through the analysis of student narratives related to their experiences of social connectedness and performance.

2. THE CONTEXT.

The university is an historically White institution and is probably regarded as one of the most elite universities in South Africa. Academic access to the institution is difficult and only students who have excelled in their formal school examinations would be considered for admission.

The Commerce AD programme is made up of students who have been placed in the programme as they have not acquired sufficient school leaving grades to be accepted to the mainstream; some students have chosen to be on the programme and some students' bursars request that they are on the programme. In their first year, students are mostly in separate small classes. Thereafter, students continue their studies in the "mainstream".

The history of AD has in many ways exacerbated students' experience of being marginalised in the university as students' identities have been constructed as being "less able" and ill prepared. In South Africa, these stereotypes have been compounded with race and class. A deficit assumption (Boughey, 2010) has predominated which focuses on filling the gaps created by students' lack of preparation to cope with tertiary studies. There has also been a strong emphasis on assimilating students into higher education with a "cultural literacy" model (Knoblauch and Brannon, 1984) foregrounding middle class, White, Anglicised norms and values.

At a structural level, there is an argument for retaining a separate structure that provides specialised support because, as Bertram (2003) argues, equity of access is not enough to ensure equity of outcomes. In a society that still bears the scars of discrimination, treating students the same has the potential to reinforce inequality as, implicitly, those who have acquired the linguistic, social and cultural competencies of the discourse are favoured (Bernstein, 1990). The AD programme therefore has the challenge of addressing the "unequal playing fields" and attempting to shift the marginalisation of students' experiences, as well as, creating a space to attract mainstream attention to consider different ways of contextualizing and developing the Commerce Faculty's students' higher education experience. Theorists such as Gee (2001) and Haggis (2004), motivate for a socio-cultural perspective on student learning which moves beyond learning as a cognitive process and takes cognisance of broader aspects related to the student learning experience with a recognition that studying in higher education involves taking on a new identity in the world, a challenging experience requiring personal development.

AD draws on its own experience of working in this context over the past ten years, as well as, a growing body of educational theory which shows that social networks are an essential resource in the formation of identity (Soudien, 2008) and central to learning. There is an intention to develop both a supportive community and a culture of learning by focusing on the provision of academic skills and creative workshops that attempt specifically to promote social connectedness and agency throughout the student's degree.

The programme now reflects a Vygotskian (1978) influence insofar as it acknowledges the social and interactive aspects of learning. In the classroom, lecturers know the students by name and much of the learning takes place using small group and collaborative work. A variety of learning structures in addition to the traditional lectures and tutorials are used. Prior learning and varied experiences are used as a resource, rather than framing students' schooling in deficit terms. Students are constructed as active participants and the various disciplines use case studies, annotated texts which mediate conceptual understanding, problem-solving scenarios, problem-based learning, simulations and experiential situations to facilitate learning. Home languages are used as a resource in the learning environment whereby students sometimes explain a particular concept in their language. A cross-disciplinary collaboration among lecturers has helped the development of an explicit meta-language which plays a role in developing students' capacity for reflective learning and facilitates transfer of knowledge and skills across disciplines. Overall, the teaching and learning environment for first year students could be described as being outstanding. This is evidenced by two of the lecturers having received the university's prestigious "Distinguished Teacher Award", higher pass rates than mainstream students in all courses and very positive feedback from students regarding their engagement in their learning.

Outside the formal classroom a suite of opportunities are provided that attempt to promote social connectedness. Specific interactive interventions exist in subject knowledge, academic and language literacies and broad life, presentation and leadership skills. The induction program at the beginning of the year for all our new students aims to forge a close family network which provides a sense of belonging and identity. A well developed web site, communication network, birthday / examination / graduation wishes and newsletter enhance contact, news and information. Monthly class meetings are held for all cohorts in order to ensure continuity, receive feedback, identify appropriate interventions and use role-models to inspire and motivate. A yearly awards ceremony acknowledges academic excellence and progress, as well as, providing a platform for students' dance, music and poetry creations.

In all these interventions, there is a deliberate attempt to create a sense of belonging to a community which offers a safe space in which students can express their fears and anxieties, but also to help foster coping mechanisms. This is in keeping with a number of theorists who have argued that if we want learners to be invested in their learning, they need to feel a sense of belonging and social connectedness (Lee and Robbins, 2000; Tinto, 2006-2007; Martin & Dowson, 2009).

The interventions throughout the degree are focused on creating a developmental and incremental impact, rather than providing support only. Students' progress is constantly monitored with a strong emphasis on working proactively in terms of both academic and psycho-social support.

3. WHY A FOCUS ON SOCIAL CONNECTEDNESS?

While the AD students have a range of diverse histories, experiences and contexts it would be true to say that many students' families are 'under siege': there are single care-givers; many students either do not know their fathers or do not have physical contact with them. This is coupled with high degrees of poverty. These onerous burdens place a powerful expectation on a particular child in the family to succeed academically and 'lift the siege'. Many of the AD students register for their Commerce degrees for instrumental reasons, as a conduit out of poverty and not necessarily because of a considered career choice. Most of the students are away from home, are not English speakers and find themselves in an environment that has very little synergy with their lives at home. This is both a source of excitement coupled with great stress around the perceived demand to adapt and fit in. These students experience varying levels of alienation and demoralisation as they attempt to negotiate their transition into this unfamiliar place.

It is this context that the programme coordinators moved to develop both a supportive community and a culture of learning by focusing on a range of interventions that attempt specifically to promote social connectedness.

4. UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL CONNECTEDNESS AND ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE.

Social connectedness (which is a sense of belongingness) relates to "one's opinion of self in relation to other people" (Lee & Robbins, 1995: 239). People exercise great effort in fostering relationships with one another, even when distance and material circumstances limit interaction (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Such behaviour makes it evident that social connectedness is a fundamental need among humans (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Lee & Robbins, 2000) that can predict favourable outcomes (Walton & Cohen, 2007) in relation to cognition, emotion, behaviour and mental wellbeing (Baumeister & Leary, 1995)

In an attempt to develop a measure for belongingness amongst university students Lee and Robbins (1995) developed a self-report scale designed to tap into aspects of belongingness amongst students. Their sample consisted of undergraduate students from a large urban south-eastern university in America. Since its development, various versions of the social connectedness scale have been used in research among college students in America (Lee & Robbins, 2000). The current study used an adapted form of Lee and Robbins's (2000) campus connectedness scale, which underwent a language review to make it suitable for the South African context.

High-quality interpersonal relationships are important in improving one's capacity to function effectively in academic life (Allen, Robbins, Casillas & Oh, 2008; Martin and Dowson, 2009) with existing research suggesting a positive relationship between healthy interpersonal relationships and academic performance (McDonald Culp, Hubbs-Tait, Culp, & Starost, 2000; Morrison, Rimm-Kauffman & Pianta, 2003; Walton & Cohen, 2007).

5. METHOD.

5.1 Research design.

The type of study conducted was descriptive in nature, taking on the form of survey research, which generated quantitative findings. In addition to the survey, six years of qualitative data about students' perceptions of social connectedness were analysed and interpreted to make greater sense of the quantitative findings.

5.2 Research hypothesis.

H1 is that there is a positive and significant relationship between social connectedness and academic performance.

5.3 Survey sample.

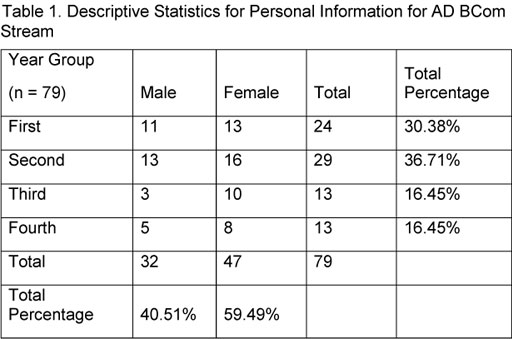

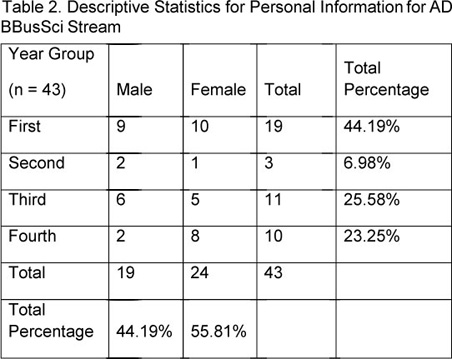

The sample was selected using convenience sampling. Of the 801 students registered in the 2009 AD programme, 129 participated in the survey, which represented a response rate of 16.1%. However, seven cases with missing data and three cases of outliers were excluded from the final analysis that made the final sample size 119. Table 1 and 2 show descriptive statistics for personal information for the AD BCom and AD BBusSci (completing a Bachelor of Commerce and Business Science Degree respectively) streams, where n = 122.

5.4 Sample description for qualitative data.

The qualitative data has been extracted from initial entry questionnaires (1200 students), formative feedback (approximately 2400 responses) and approximately 30 individual interviews. The sample characteristics represent the characteristics of students in the AD programme; the respondents are all black and are made up of equal numbers of males and females.

5.5 Materials.

The campus connectedness scale (Lee & Robbins, 2000) measured social connectedness among students in the AD programme.. The scale had 14 items, measured on a 6-point Likert scale with responses ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (6). An example of a scale item is "I can relate to my fellow classmates" (Lee & Robbins, 2000).

A review of Lee and Robbins's (2000) campus connectedness scale revealed that some of the language used was not entirely appropriate to the South African context; hence, the researcher adjusted the scale. The major changes related to language, for example, the word "university" replaced "college", the former being more commonly used within the South African context. Although the scale, which was developed in the United States, had been proven to be valid and reliable in previous studies (a = 0.91), these minor changes in language had to be made to ensure that it was contextually appropriate. Owing to the changes made to the scale, the researchers conducted a factor analysis to check the quality of the scale. It revealed that the items measuring social connectedness related to one main factor. These results are presented in the Results section.

5.6 Final composite questionnaire.

The final questionnaire developed had 13 items measuring social connectedness. The questionnaire included additional items that recorded demographic variables such as first generation participation in higher education and lecture attendance, as well as, personal information such as gender.

An analysis was conducted which took a closer look at the correlations between items that measured social connectedness. Lee and Robbins (1995) in their study sought to eliminate any scale items that showed word overlap as evidenced by a high correlation. They recommend following this procedure when developing a new scale. For the social connectedness scale, no two items had a correlation above 0.63, which suggests that the scale had no duplicate items that required deletion.

5.7 Academic performance.

Cumulative GPA scores, extracted from the student information management system (PeopleSoft), measured the academic performance of students. Cumulative GPA was calculated by combining the actual performance of students (expressed as a percentage) in their various courses multiplied by the weighting for the specific course The cumulative GPA scores used were from students' academic results at the end of the first semester in 2009.

5.8 Procedure.

5.8.1 Quantitative.

The researchers used an online survey tool to develop the final questionnaire. The survey tool recorded survey responses electronically and exported these into a spreadsheet for analysis. The researcher then approached staff within the AD programme and consulted with them regarding the best method to use for sending out the survey. Based on their recommendations, a web link to the questionnaire was posted on the AD programme's course web page. Students then received a notification via email, which invited them to complete the online survey. The email provided details on the topic of research together with instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. In order to fulfil ethical standards, instructions outlined in the email stated that students' responses would remain anonymous and confidential. The researcher obtained ethical clearance from the Commerce Faculty's Ethics in Research Committee prior to the data collection process.

The researchers calculated a composite score for social connectedness and matched this score to each student's GPA score, in order to investigate the relationship between social connectedness and academic performance. The results section below presents an analysis of these variables.

5.8.2 Qualitative.

AD survey and procedure for qualitative data collection. Qualitative data had been collected over a period of six years as students complete a survey with open-ended questions when they first enter the university and then complete formative evaluations during AD class meetings that are held throughout the degree. Qualitative data were also collected through a range of individual interviews, focus groups, as well as, filmed narratives focused on students' experiences.

6. QUANTITATIVE RESULTS.

STATISTICA 8 was chosen to analyse the quantitative data collected. Statistically significant relationships were evaluated using the Pearson's correlation test, which was conducted at a significance level of p < .05.

6.1 Reliability and validity analysis.

The reliability analysis conducted for the campus connectedness scale resulted in a high Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α = .86), which was similar to the result obtained by Lee and Robbins (2000) in their study.

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the social connectedness scale and student GPA. The theoretical maximum for the Social Connectedness Scale is 78, and hence the mean score for this sample must be viewed in this context.

6.2 Testing for normality.

The Shapiro-Wilk's test for normality indicates that the assumption of normality for both the independent variable and dependent variable GPA was not violated.

Bivariate correlations between the variables of social connectedness and academic performance. A Pearson Product Moment correlation was computed in order to investigate the relationships between the variables in the study. A significant positive relationship was found between SC and GPA (r = .259; p = .004). However, the low correlation suggests that this relationship is weak.

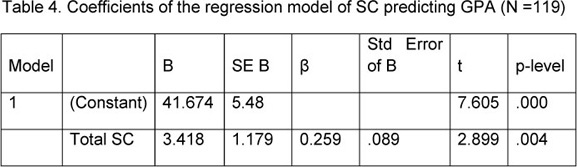

6.3 Regression analysis of social connectedness and academic performance.

Using a multiple regression analysis, a predictive model was developed using SC as a predictor and GPA as the outcome variable. The model was found to be significant (p = .004) and 6.7% of the variation in GPA is explained by the variation in SC (R2 = .067, adjusted R =0.59).

7. QUALITATIVE RESULTS.

The qualitative data used in this study was analysed using Miles and Huberman's (1991) thematic analysis technique for analysing qualitative data. Multiple readings of the text resulted in the identification and categorisation of a series of themes related to the students' experiences of social connectedness. These themes are presented below and direct quotations are used as evidence to substantiate the validity of the theme. The quotations are referenced to individual respondents who have been allocated a respondent number.

7.1 The transition from school to university.

Evidence from the entry surveys and formative evaluations suggests that, while students come with a range of experiences and backgrounds, there is usually an overwhelming shock experienced by most at the difference in the size of the university as compared to school, the great deal of talent and competitiveness in comparison to their high school experiences, the large work load demands, as well as, the conceptual sophistication required to operate successfully within the university environment. These experiences are exacerbated by the often extreme differences in life style, independence, language, food, and diversity.

"Because I've been living away from my friends and my family and I have to kind of find myself away from all, find out who I am away from all those things that used to define me, ja". (Respondent 1).

"Varsity, the pace and the way you do things is completely different to school and one of my teachers did try and give us a university way of teaching us but I don't think, I think because it was only in that one subject, it wasn't effective, like it didn't teach me to come up with new skills that I could practice and develop whilst I was in school so that when I come here I am able to implement them and be successful in varsity". (Respondent 8).

Analysis of the formative evaluations suggests that the shift to English medium as the mode of instruction and the predominant lingua franca in the university exacerbated students' sense of isolation, their conceptual misunderstandings and their experience of English as a "silencing" force. "I'm finding it difficult to understand ... very fast and strictly in English". (Respondent 66).

7.2 Prior experiences of isolation.

A key theme to emerge from the qualitative analysis is students' sense of isolation prior to entering the university and the AD. Parents often work long hours, are far away from home and some are absent, elderly or ill. A number of students moved between a parent's, a grandmother's or a relative's home as family circumstances changed, often with consequent change of schools.

"For the past 2 years, I have been feeling a bit isolated, since my mother passed away I haven't had anyone to talk to" (Respondent 34).

Many of the students perceive their parents to have been relatively uninvolved in their school education in that they rarely attended school meetings, did not help with homework and did not exert much discipline. The analysis suggests that parents of students from working-class schools were not part of the students' decision to come to university and sometimes had to be convinced to allow this to happen. "I came from a school where the students all believe that none of them can become a success ... So, it was extremely difficult for me to pursue without support and understanding of everyone else". (Respondent 22).

The results of the qualitative analysis point to the reality that many of the students in the AD programme have had an inordinate amount of responsibilities at a young age, have often experienced little adult guidance and have had to make decisions and negotiate the world alone. Equally, there are a minority of students with very loving families, strong mothers or grandmothers who are critical "life lines" for the students. The notion of family almost always extends beyond the nuclear family and will include a range of extended family members. The experiences of those students who have come from fairly isolated circumstances have meant that students have built their own internal resources to cope and often have strong religious sponsoring discourses: "I've gone through so much in life, nobody understands the trials and tribulations I've been through but through God I've overcome most of them". (Respondent 27).

7.3 The AD family: Providing a sense of belonging.

Students who have experienced a great degree of isolation are particularly appreciative of being in a newfound context of interest, support, care and shared journey. Those who have experienced caring contexts, view the AD as a home away from home. A key theme that emerged throughout the qualitative data sources is students' experiences of the AD as a family and the impact of the AD on their sense of belonging and connectedness.

"Being on the AD has been the turning point in my life ... I feel like a part of a family here". (Respondent 23).

For most students there is a fairly strong adjustment to be made from their home context and negotiating this with support and fellowship is strongly appreciated.

"Some days would be really tough but the words of encouragement they would give us during our class meetings meant a lot. At times I felt like giving up but the support I received from AD I felt I had to so keep fighting and was encouraged to work harder" (Respondent 40).

"I was more than just a number". (Respondent 33).

The qualitative data suggests that the experiences implicit in the AD programme have impacted strongly on the students' sense of worth and motivation and have helped energise them to cope within the university environment.

"Varsity has made us realise the importance of having support from the AD family to remind us of our dreams and goals because the journey can sometimes throw you off track". (Respondent 21).

"Being a part of the AD family has given me a great sense of belonging because all my life I have felt out of place" (Respondent 26).

"AD has given me a sense of belonging and family life." (Respondent 20).

"The relationships I have built are ones I hope will last a lifetime" (Respondent 20)

Students who have had supportive family or community experiences have also strongly endorsed the sense of belonging experienced in the AD.

"In AD you feel at home and I never felt and don't think I will feel alone". (Respondent 27).

"I came here very scared, but the last 3 years have been the best years of my life and I have found my 'second family', the AD programme." (Respondent 32).

8. DISCUSSION.

8.1 Social connectedness and academic performance.

This study confirms the hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between social connectedness and academic performance. While statistically significant the weakness of the relationship has a bearing on the practical significance of this result. There are a multitude of possible explanations for the weak but statistically significant relationship ranging from the appropriateness of the scale, to the nature of the GPA measure. While the GPA measure is commonly used to study academic performance, it might not be the most robust measure when doing research with students from multiple years completing a vast range of diverse courses. There is an opportunity here for future studies to experiment with alternative ways of measuring academic performance and assessing if this may influence the strength of the relationship. For example, researchers can attempt to isolate one or two common courses within students' degrees and use the results of these courses to calculate academic performance.

8.2 Social connectedness as a key component of the AD programme.

Applying the definition of social connectedness as "one's opinion of self in relation to others", (Lee & Robbins 1995: 239) it is evident that the students in the AD programme feel a strong sense of connection with one another, as confirmed by their high mean scores on the campus connectedness scale. This result is corroborated by the results of the qualitative analysis which suggest that there is an overwhelming acknowledgement amongst students that the AD provides a sense of belongingness and a safe space that is nurturing, encouraging and supportive. In the formative evaluations and interviews the word "family" is frequently used to describe the programme.

This is particularly pertinent given the South African context in which high degrees of alienation, and numerous stress factors and socio-economic issues weigh heavily on vulnerable students. Coping with the rigours of a demanding academic degree in the midst of sometimes profound levels of alienation is clearly a recipe for failure. Paying attention to a range of interventions, language, ways of being and support, the AD is providing an alternative space for students to experience and negotiate their academic demands. The results of this study suggest that the AD programme has, through its various activities, succeeded in developing social connectedness and a sense of belonging among students. The positive correlation between social connectedness and academic performance confirms that a student with a strong sense of belonging or connectedness is likely to obtain a higher GPA than a student who experiences less of a sense of belonging. This result is consistent with previous studies which have concluded that healthy interpersonal relationships have a positive effect on academic performance (Bennett, 1997; Pianta et al 1997; Culp, Hubbs-Tait, Culp, & Starost, 2000). It is evident from these results that the way in which social connectedness is engendered into the programme appears to be contributing positively to the performance of students.

Social connectedness may also have another positive benefit in that it decreases feelings of loneliness. Ginter and Dwinell (1994) suggest that students who experience less loneliness and higher levels of social support are more likely to exhibit greater academic persistence. Although they did not find a link between academic persistence and academic performance, academic persistence increased the likelihood of staying at university (Tinto, 2006-2007). In the South African context, in which a large proportion of students drop out of university after their first year of study (Groenewald, 2005 as cited in de Klerk, et al, 2006), fostering academic persistence becomes important if it contributes to higher student retention rates.

The AD programme has made concerted efforts to ensure that students form strong bonds with one another in order to develop a sense of belonging. This exploratory quantitative research indicates that these efforts have made a minimal impact on student performance, while the qualitative work indicates strong positive feedback regarding AD initiatives that promote social connection toward students' general sense of well being. Whether this will eventually impact on a stronger statistical significance, remains an area for future work and investigation.

9. CONCLUSION.

The research presented in this paper suggests that a range of activities and teaching pedagogies throughout the degree that will enhance social connectedness are necessary and valuable. The imperative of this research is to signal the development of a more robust and nuanced way of ascertaining and measuring social connectedness and academic performance. This will then provide a solid case study to implement the variety of interventions, pedagogies and value added experiences that will enhance social connectedness and ultimately academic performance.

REFERENCES.

Allen, J, Robbins, S, Casillas, A & Oh, I (2008) Third-year college retention and transfer: Effects of academic performance, motivation, and social connectedness. Research in Higher Education, 49, 647-664. [ Links ]

Badat, S (1995) Educational politics in the transition period. Comparative Education, 31,2, 141-159. [ Links ]

Baumeister, R F & M R, Leary (1995) The need to belong: Desire for Interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin,117,3, 497-529. [ Links ]

Belenky, M F, Clinchy, B M, Goldberger, N R & Tarule, J M (1986) Women's ways of knowing: The development of self, voice, and mind. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B B (1990) Class, codes and control. Volume IV: The structuring of pedagogic discourse. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Boughey, C (2010) Academic development for improved efficiency in the Higher Education and Training system in South Africa. Unpublished draft 1 to DBSA. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P (2002) Forms of capital, in Biggart, N (ed) Readings in economic sociology. Malden, Mass: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Chen, J & Lin, T F (2008) Class attendance and exam performance: A randomized experiment. Journal of Economic Education, 39 (3), 213-227. [ Links ]

Culp, A, Hubbs-Tait, L, Culp, R E & Starost, R (2000) Maternal parenting characteristics and school involvement: Predictors of kindergarten cognitive competence among Head Start children. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 15, 5-17. [ Links ]

De Klerk, E, van Deventer, I & van Schalkwyk, S (2006) Small victories over time: The impact of an academic development intervention at Stellenbosch University. Education as Change, 10,2, 149-169. [ Links ]

Gee, J (1990) Social linguisitics and literacies: Ideology in discourse. Basingstoke: Falmer. [ Links ]

Gee, J (2001) Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education, 25, 99-125. [ Links ]

Gilligan, C (1982) In a different voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Ginter, E J & Dwinell, P L (1994) The importance of perceived duration: Loneliness and its relationship to self esteem and academic performance. Journal of College Student Development, 35(6), 456-460. [ Links ]

Haggis, T (2004) Meaning, identity and "motivation": Expanding what matters in understanding learning in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 29,3, 335-352. [ Links ]

Knoblauch, C & Brannon, L (1984) Rhetorical traditions and the teaching of writing. Upper Montclair, NJ: Boynton Cook. [ Links ]

Lee, R M & Robbins, S B (2000) Understanding social connectedness in college women and men. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78,4, 484-491. [ Links ]

Lee, R M & Robbins, S B (1995) Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 422, 232-241. [ Links ]

Martin, A J & Dowson, M (2009) Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practices. Review of Educational Research, 79,1, 327-365. [ Links ]

McDonald Culp, A, Hubbs-Tait, L, Culp, R E & Starost, H J (2000) Maternal parenting characteristics and school involvement: Predictors of kindergarten cognitive competence among head start children. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 15,1, 5-17. [ Links ]

MacGregor, J, Cooper, J L, Smith, K A & Robinson, P (2000) Strategies for energizing large classes: From small groups to learning communities. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 81, Spring. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Morrison, E F, Rimm-Kauffman, S & Pianta, R C (2003) A longitudinal study of mother-child interations at school entry and social and academic outcomes in middle school. Journal of School Psychology, 41,3, 185-200. [ Links ]

Nicpon, M F, Huser, L, Blanks, E H, Sollenberger, S, Befort, C & Kurpius, S E R (2006) The relationship of loneliness and social support with college freshman's academic performance and persistence. Journal of College Student Retention, 8,3, 345-385. [ Links ]

Perry, W G (1970) Forms of intellectual and ethical development during the college years. Austin: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Peterson, I, Louw, J & Dumont, K (2009) Adjustment to university and academic performance among disadvantaged students in South Africa. Educational Psychology, 29,1, 99-115. [ Links ]

Piaget, J (1952) The origins of intelligence in children. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Pianta, R C, Nimetz, S L & Bennett, E (1997) Mother-child relationships, teacher-child relationships, and school outcomes in preschool and kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,12, 263-280. [ Links ]

Soudien, C (2008) The intersection of race and class in the South African university: Student experiences. South African Journal of Higher Education, 22,3, 662-678. [ Links ]

Springer, L, Stanne, M E & Donovan, S S (1999) Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 69,1, 21-51. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche, M & Durrheim K (eds) (1999) Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Tinto, V (2006-2007) Research and practice of student retention: What next? Journal of College Student Retention, 8,1, 1-19. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L S (1978) Mind and society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Walton, G M & Cohen, G L (2007) A question of belonging: Race, social fit and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92,1, 82-96. [ Links ]

1 Generic term to be used for all previously disenfranchised people in South Africa.