Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Psychology in Society

On-line version ISSN 2309-8708

Print version ISSN 1015-6046

PINS n.36 Stellenbosch Jan. 2008

ARTICLES

Using photo-narratives to explore the construction of young masculinities1

Malose Langa

School of Community and Development, University of Witwatersrand. Private Bag X3, 2050. malose.langa@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article illustrates the use of photo-narratives to explore a group of adolescent boys' constructions of young masculinities. The boys were from Alexandra Township, an historically working-class and black community in Gauteng. The participants in this study were provided with disposable cameras to take 27 photographs using My life as a boy as the theme. Arrangements were made for the photographs to be collected and processed. In the follow-up interviews, the boys were asked to give a description of each photograph and why and how they had decided to take that photograph to represent aspects of their masculinity. Some of the photographs taken depicted cars, girls, shoes, smoking, drinking, reading books, cleaning and cooking. The photo-narrative method proved useful in allowing boys to represent multifaceted aspects of themselves and their lives and also seemed to highlight both individualised and subjective aspects as well as dominant or normative aspects of masculinity. In talking about their photographs, it is clear that the construction of young township masculinities is characterised by feelings of ambivalence, hesitation and contradiction. The boys in this study seemed to simultaneously comply with and oppose hegemonic norms of masculinity in the narrative images. The boys' photo-narratives reveal that negotiating alternative voices of young township masculinities is fraught with emotional costs and sacrifices.

Key words: hegemonic masculinity; young masculinities; township boys; photo-narrative

Many studies on masculinities have been conducted with adult male populations (Seidler, 2006), but currently there is a growing interest in young masculinities. British researchers, Frosh, Phoenix and Pattman (2002, 2003) have led the way in doing research focusing on young masculinities. The value of conducting research with young boys in order to understand how they negotiate the multiple voices of masculinity has been widely acknowledged. Frosh, Phoenix and Pattman (2003) argue that young masculinities are multiple, and that different versions of masculinity always compete for dominance. Young boys' views on masculinity are also fluid rather than fixed or static, and are dependent on the situation in which they find themselves.

In reviewing studies of masculinity among young boys, Frosh et al (2002, 2003) emphasised that the ways in which boys enact their masculine identities seem to be contradictory. Adolescent boys express multiple positions, reflecting conflict and contradictions in their constructs of masculinity. Male peers use the power of language to "police" one another in the production and regulation of a range of masculinities. Boys who do not comply with traditional norms of masculinity tend to be "othered" (Renold, 2004) and called derogatory names such as "losers" (Connell, 1995), "sissies" (Frosh, Phoenix & Pattman, 2003), "nerds" (Gilbert & Gilbert, 1998) and "yimvu" (sheep) (Bhana, 2005). One area of contestation amongst adolescent school boys appears to revolve around academic achievement in, and heterosexual experience outside school. In their study in the United Kingdom, Haywood and Mac an Ghaill (1996) found that the lack of heterosexual experience on the part of academic achievers and A-level learners became a resource for other boys in the school to impose definitions of what it means to be a "real boy".

In this study, a "real boy" was seen as one who engages in risk-taking behaviours such as smoking, drinking and having sex with multiple partners. These boys interpret academic achievers' heterosexual inexperience as illustrating immaturity. Terms like "kgope" or "lekgwala" (a boy without a single girlfriend) or ibhari (a boy who is too scared to talk to girls) are used to insult and ridicule academic achievers in local African and South African contexts (Niehaus, 2005; Pattman, 2005). On the other hand, the academic achievers ridicule the other boys as inarticulate and stupid, referring to them in class as "cripples", "cabbages" and "spanners" (Haywood & Mac an Ghaill, 1996; Gilbert & Gilbert, 1998). This shows that the interpretation of successful masculinity amongst boys can be highly contested. Masculine identities compete with each other for legitimacy and dominance. These contestations and preferences over masculinities will differ from one context to another.

The changing nature of masculinities may also be influenced by socio-historical and political contexts. The current study looks at the shifting nature of young masculinities in Alexandra Township after 15 years of democracy. Various studies had been conducted with youth in the townships in the early 1990s (cf. Mokwena, 1991; Freeman, 1993; Glaser, 2000). These studies indicate that the political environment in the 1990s played a central role in shaping the masculine identities of young boys at the time. All boys were expected to be politically active (Freeman, 1993; Xaba, 2001; Langa & Eagle, 2008).

After 1994, the notion of a "lost generation" gained popularity in the mass media, with reference to young black males who had lost interest in politics (Stevens & Lockhart, 1997). Unlike the youth of 1976, the lost generation was constructed by these writers (Stevens & Lockhart, 1997) as largely a cohort of "Coca-cola kids" who were more concerned with material possessions than social. Other studies too have documented the obsessive embrace of all things American by South African youth, including speaking English with an American accent, wearing baggy jeans, playing basketball, and listening to RAP music (Pattman, 2005).

At about the same time, the term, "Y generation", also emerged in reference to urban "youth" culture in post-apartheid South Africa (Mtebule, 2003). The term "Y" is borrowed from the Yfm radio station, whose audience is urban black youth in Gauteng. The Yfm station focuses mainly on issues of young urban lifestyles, fashion, music, and social issues. Like the Coca-cola kids, the "Y generation" has been berated by the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL), amongst others, as being politically and academically feeble. The "Y generation" is generally criticised for being more concerned with street bashes and parties than political issues. Moreover, the role models for a "lost or Y generation" are not struggle heroes such as Steve Biko, Oliver Tambo and Robert Sebokwe. Instead, their icons are movie and music stars like Tupac, 50 cent, Eminem and Ja Rule (Pattman, 2005). However, other writers (for example, Freeman, 1993) have contested the construction of young people as a "lost or Y generation". Freeman argues that these descriptions are unhelpful and incorrect in that they encourage society to give up on the youth.

Given this background, it is important to continue to explore masculine identities amongst adolescent boys in South Africa, particularly given that they are the future leaders and also given the risks that they face in contemporary society, including HIV contraction and exposure to violence. The main aim of this study is therefore to explore how township boys are developing and living different forms of masculinity.

BOYS TAKING PHOTOGRAPHS ON WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A BOY

Twenty-five adolescent boys between the ages of 13 and 18 years in grades 10 and 11 were recruited from two secondary schools in Alexandra Township (after permission to conduct research was obtained from the relevant authorities). Schools are useful sites for research on adolescents and have been the sites of some of the British and Australian studies that have influenced the research project on which this article is based (Haywood & Mac an Ghaill, 1996; Frosh et al 2002, 2003). These studies have shown that schools influence the formation of gendered identities, marking out "'correct' or 'appropriate' styles of being a male" (Butler, 1990, in Haywood & Mac an Ghaill, 1996:19).

The researcher advertised the study by visiting classes of grade 10 and 11 to meet with boy learners to explain the nature of the research project, and to provide them with an information sheet and parental consent and participant assent forms. Only boys who returned the signed forms were included in the study. The number of participants exceeded 18, the initial number that the researcher had targeted. Many boys wanted to be part of the research project, in part perhaps because of the prospect of access to disposable cameras. All the boys who became participants were excited to be given disposable cameras to take 27 photographs (the total available on the film) under the theme "My life as a boy". In taking their photographs, boys were encouraged to think about the following questions: What is it like to be a boy? What are the things that make boys feel like "real boys"? How do boys spend their time? What are some of the challenges that boys face? What do other people (for example, friends, parents, teachers and girlfriends) expect from young boys? What makes some boys more popular than others? Are there alternative ways of being a boy?

The boys were then given a period of two weeks to take photographs. The space and time afforded to the participants enabled them to think about how they wanted to represent themselves (cf. Noland, 2006), but also required them to focus on the task.

After two weeks, arrangements were made for the researcher to collect all the disposable cameras. Two sets of the photographs were processed and one set was placed in an album and returned to the participants. Following the photograph collection phase, a set of narratives to accompany the photographs were collected from the participants by means of semi-structured individual interviews and focus group discussions.

BOYS TALKING ABOUT THEIR PHOTOGRAPHS IN THE INDIVIDUAL INTERVIEWS AND FOCUS GROUPS

Individual interviews were arranged with each boy. In the individual interviews, boys were asked to provide a description of each photograph they had taken and why and how they decided to take that particular image. This kind of interview process in which photographs are used to prompt interview responses, is referred to as photo-elicitation (Noland, 2006; Blackbeard & Lindegger, 2007).

The boys were also asked to describe the ways in which the photographs they had taken represented aspects of their masculinities. In the individual interviews, the researcher also ensured that a wide range of issues, in keeping with the scope of topics covered in other related research (Frosh et al, 2002, 2003) were covered, including the boys' self-definition as male or masculine; their role models; their relationship with other boys and girls; intimacy and friendships; HIV/AIDS; violence; careers; and substance abuse.

As indicated, focus group discussions were combined with individual interviews. Using focus groups in this research was in line with the research aim of assessing whether constructions and enactments of masculinity are structured by the situations in which boys find themselves. Would the photo-narratives that boys shared in individual interviews remain the same when in a focus group with other boys or would they feel more pressurised to comply with dominant norms of hegemonic masculinity and present a more normative version of themselves? The boys were invited to a group interview following their individual interviews. Most of the participants elected to take part in the focus group discussions and seemed curious about other boys' outputs. Their participation in the focus groups was voluntary. Three focus groups were facilitated. The first focus group had five boys and the second and third focus groups had six boys each. The focus groups took place two weeks after the individual interviews. Again the researcher used photographs as a springboard to elicit discussion. In the group interviews, the boys were asked to choose only five photographs (out of their 27 photographs) that best described them as boys and to show them to the other boys in the group. This helped to set the mood for the group discussions.

The discussion of "living" masculinity in the focus groups was markedly different from the individual interviews. In the focus groups, some boys were embarrassed to show their photographs, while for others the group interview seemed to become a game with participants competing against each other to provide the most comprehensive information about their photographs. Of note, some boys changed their previous narratives about the photographs. In the individual interviews, the participants were willing to embrace alternative voices, but in the group interviews they appeared shy to talk about certain photographs or embarrassed to express certain views that might have led to them being viewed as "sissies" and "inappropriate". Thus, there was a strong sense that in a group situation, boys wanted to be seen to conform to the norms of hegemonic masculinity (Frosh et al, 2002; Lindegger & Maxwell, 2007; Ratele et al, 2007).

The combination of individual interviews and focus group interviews thus provided varied information, insight and ideas about what it means to be a boy. The researcher was able to observe how boys "police" and "regulate" one another in a group context. The use of photographic images as a route into discussing masculinity in both contexts seemed to enhance the discussion and produced a heightened level of engagement on the part of the boys. Both the content of the images as well as the participants' discussions on the images provided useful data, as will be illustrated in the subsequent discussion.

BENEFITS OF USING PHOTO-NARRATIVES IN RESEARCHING YOUNG MASCULINITIES

In line with the work of Collier and Collier (1986), Noland (2006) and Blackbeard and Lindegger (2007:30-31), the following benefits of using photo-narratives to research young masculinities have been identified in the present study:

Participants take the role of an "expert guides" leading the interviewer through the content of the photographs

In describing their photographs, the participants in this study were authors of their own stories or narratives. They shared their personal experiences of what it means to be a boy with the aid of their photographs. Photo-narratives seemed to offer a gratifying sense of self-expression, as participants in this study were able to express and educate the interviewer about the photographs taken. The use of photo-narratives also allowed boys to tell their stories about what it means to be a boy spontaneously, without feeling pressurised about what might be wrong or right. Participants seemed to enjoy explaining the context of an image to the interviewer, for example why a particular brand of clothing (see Photograph A below) was construed in a particular way. In a sense, they became aware of having "cultural capital" and being experts on their own lives and life contexts. This allowed for an inversion of roles, in that the researcher was constructed as a recipient rather than provider of knowledge.

Participants take an active role and participatory role in data collection

The boys were active participants in data collection and in the selection of images that best described and represented their masculine identities. When asked about the process of taking photographs on what it means to be a boy, Themba2, William, Thabiso and Simon responded as follows:

Themba: "It was a nice experience that I wish I can do it again. I wish there were 30 to 50 photos".

William: "I needed to think if I take this photo what I'm going to say this and that. I take this picture and analyse the story yeah".

Thabiso: "Taking photos was okay because you were taking photos of things that you value".

Simon: "Ja. I actually think of who I take a photo of. At first when you gave me [the camera] that first day; I thought about it, and I was like okay; I am gonna come back to this idea. And then I thought about it a lot, and then I thought who can I take? Where I can I take this camera to? A photo of who can I take? What am I gonna say about this photo?

It is clear that the participants put considerable thought and reflection into deciding which photographs to take. The quotations suggest that they experienced a sense of agency (as suggested by salience of the personal pronoun, "I", for example) and also had a strong sense of responsibility in undertaking the task. It is almost as if they felt that the researcher had handed over something of value to them (not just materially) and that they were entrusted with a task which required care. This is particularly evident in the last quotation. Both William and Simon also indicated that the act of taking photographs led to the process of self-reflection. In questioning how they would account for their decisions, they engaged in internal dialogue. It also seemed that the actual activity required walking around, composing images and taking pictures, all of which were considered stimulating and worthwhile by the boys.

Using photographs is non-intrusive and open-ended

In this study photographic images functioned as the starting point for discussion. Photo-interviewing gave the participants a significant degree of freedom to express their own views about what it means to be a boy. This was particularly the case in the individual interviews. The participants also seemed to feel less pressurised to complete the interview process. Many photographs reflected the boys' everyday experiences, but also allowed them to create and express their fantasies about life and their futures as young males. This could be seen in photographs taken that included flashy cars and big houses with swimming pools (see Photograph B), suggesting a projection into a different desirable future. Although sometimes initially shy, the participants seemed eager to share their images and insights, which is not always the case when interviewing adolescents. The ambiguity of the meanings attributed to with the pictures (even when apparently concrete in content) allowed the participants to elaborate their ideas in the directions that made sense to them, thus allowing for somewhat more open-ended data collection.

Building rapport and collaboration

Taking photographs helped the researcher to establish rapport with the participants. Before the initial interview, the researcher spent a lot of time with the participants, teaching them how to use their disposable cameras. Two weeks later the researcher returned to collect the photographs so as to have them processed. He subsequently set up the interviews. The repeated visits to the schools and contact with the boys enhanced the researcher's relationship with the participants. The researcher took care to return the photographs to the boys, placing them in a photo-album. The fact that the boys received something tangible back as a reminder of the research process also seemed to enhance the rapport. Given the personal content of some of the photographs (some of the photographs, for example, were of important family members) the individual interview discussions were sometimes surprisingly intimate, with disclosure of revealing material. While this may in part have been attributable to the interviewer's training as a counselling psychologist, the photo-narrative method nonetheless appeared to enhance the depth of disclosure and rapport.

INTERPRETING PHOTOGRAPHS

Interpreting photographs involves going beyond the simple description of the images. Interpreting photographs is to tell someone else what you think about the photographs taken. Zillier (1990, in Seedat, Baadtjies, van Niekerk & Mdaka, 2006) argues that photographs set up a discourse between the photographer and the viewer. The photographer is compelled to attend selectively to elements of personal interest; he or she decides what to show the viewer and how it will look to the viewer, and anticipates how viewers might react to it. This sense was evident in the previous quotations. Riley and Manias (2003, in Seedat et al, 2006:304) identified three ways of looking at photographs: "(1) looking at the image to analyse information internal to it; (2), looking at the image to examine the way in which the content is presented; and (3) looking behind the image to examine the context, or the social and cultural relations that shape its production and interpretation".

Pink (2001, in Seedat et al, 2006) supports the idea that researchers should attend to the internal meanings of a photograph, how the photograph was produced and how it is made meaningful by its viewers. In this study, the researcher followed Riley and Manias's three steps outlined above in interpreting photographs to understand the construction of young masculinities among adolescent boys in Alexandra Township, but placed greatest weight on the third aspect given the intention of the research study.

THE PHOTOGRAPHS: REPRESENTATIONS OF BRANDED MASCULINITY

The participants took a range of photographs, representing what could be understood as both hegemonic and alternative versions of young masculinities. It is clear that in some of the depictions of themselves the participants resisted, subverted and challenged the existing popular norms of "hegemonic" masculinity that are dominant within the township of Alexandra. The boys seemed to vacillate between the two discourses of the "new" and the "traditional" attributes of being a boy or man (Ratele, Fouten, Shefer, Strebel, Shabalala & Buikema, 2007).

A particular version of hegemonic masculinity was "reproduced" (Connell, 1995) in some of the photographs. For example, many photographs included flashy cars (for example, BMWs, Benzes, Mini Coopers, Hummers, Volkswagens and Volvos). Other depictions also included brand labels of shoes (for example, All Stars, Superega and Carvella), clothes (for example, Nike, Polo, Lacoste and Adidas) and cell phones (for example, Nokia, Samsung and Motorola). These represent what Alexander (2003) calls consumer or branded masculinity, which is all about representing oneself as desirable or "hip" by choosing an expensive brand name, which connotes something significant about one's masculinity as a township boy (Alexander, 2003). In discussing their photographs, the boys talked about the importance of having money, owning a car, having beautiful girlfriends, and also wearing expensive brand clothes and shoes. This is illustrated with specific images in the section below:

I found Simon's photograph of Absa Bank to be quite a compelling representation of the dominant norms of capitalist masculinity (Connell, 1995; Edley & Wetherell, 1995). In his narrative about this photograph, Simon asserts that having money symbolises something important for many young boys in Alex. According to him, boys who do not have money are simply viewed as "that", that is, as lacking in status, which means they are "nothing" in the male peer group. Interestingly, Simon compares having money to "having a girlfriend"; in part because "if you don't have money first of all girls won't like you". It is important for young men to publicly demonstrate their status relative to other men, either by showcasing their wealth in some form or by having access to beautiful girlfriends. These seem to be prototype aspirations associated with masculinity.

It is also interesting how women are objectified as a kind of commodity to be won in this discursive construction of masculinity. It sounds as if Simon is angry with "the typical girls of Alex", who only like "sugar daddies" (men who are already working, drive flashy cars such as BMWs and Mercedes Benzes, and can afford to buy them expensive gifts) (Hunter, 2005; Lindegger & Maxwell, 2007). These sugar daddies can afford to go to ABSA Bank and withdraw more money to attract "the typical girls of Alex". The boys in this study complained bitterly and also expressed their anxieties and frustrations about being rejected by girls who were too materialistic as well as their powerlessness in relation to these older, rich men (Hunter, 2005; Lindegger & Maxwell, 2007). The anger was not only directed at sugar daddies, but also at boys who come from rich families who could also afford to buy their girlfriends expensive gifts. In the group interview below, working class boys commented on their relationship with boys who have money:

William: "In most cases [these are] boys who have rich parents. They drive their parents' cars. They wear expensive clothes and girls want them."

Researcher: "How do you feel about these boys from rich families?"

William: "I do envy them, [but] what I feel about these boys [is] they are spoilt now. They don't know how to do things for themselves. If something happens to their parents they will struggle big time."

Thabiso: "It is their time. Our time will come."

It sounds as if both William and Thabiso feel resentful of boys who come from rich families because they drive their parents' cars and have access to pretty girls. In the township, boys who come from rich families are called derogatory names such as "cheese boys" or "amabhujwa" (Stevens & Lockhart, 2003). In the above narrative, the participants also seem to be using subtle messages to express envy, and to wish cheese boys ill fortune. The subtle communication in Thabiso's narrative is that cheese boys will be punished in the future when "our time comes", apparently to also own cars and have access to pretty girls. In expressing his feelings of envy, William mentioned that cheese boys will struggle "if something happens to their parents". William states that the cheese boys will struggle "if their parents die and their suffering" will be worse because "they don't know how to do things for themselves".

In the above extract, cheese boys are constructed as "spoilt brats". They are accused of bragging about things that they have not worked for. The working-class boys seem to be expressing such negative feelings towards cheese boys as a coping strategy to deal with their own internal feelings of envy and deprivation. However, rather than this coping taking the form of a rejection of the consumerist markers by which the cheese boys lead their lives, the poorer boys project themselves into an ideal future in which they will "outreach" the indulged middle-class boys through their own material achievements. Class seemed to be an important factor determining how boys negotiate the multiple articulations of masculinity.

In this study, all 25 boys took one or more photographs of girls. In both the individual and group interviews, the participants spent a lot of time talking about their relationships with girls. All the boys argued that it is important for a boy to have a girlfriend. However, simply having a girlfriend is not enough to prove that "you are a real boy" (Pascoe, 2007). In addition, "your girlfriend must be pretty" (Simon). The use of "must" in Simon's narrative connotes the necessity of having girlfriends deemed "pretty" in order to gain recognition. For example, in choosing five photographs that best described them, in one of the group interviews, the boys were clearly competitive about who had a picture of the most beautiful girl. In this group, boys bragged about the beauty of their girlfriends. According to Hunter (2005) dating a beautiful girl accords a boy the status of being ingagara (a "real" boy), a status that is not accorded to those boys who date girls that are not deemed "pretty".

Simon: "You see if your girlfriend is not pretty - I mean your friends won't like the girl because your friends are gonna say your girl is ugly".

William: "I do not think there is a guy who would want to settle with an ugly chick. That is what I think".

Dating an "ugly" girl brings shame. William goes further and states: "If you have an ugly chick we will say your mama will kick you out if you come with such a thing at home. And we will tease around and stuff". Simon agrees with William that dating an "ugly" girl is "something you are gonna be ashamed of, and asking yourself how your child is gonna look like, would the child be ugly like the mother". Simon and William contend that dating an "ugly" girl brings disgrace, humiliation and embarrassment. In the case of William, his mother would not be proud to see her son dating an ugly girl and would reject him for bringing such a "thing ... home". Here William implies that mothers also expect their sons to date beautiful girls. "Ugly" girls are seen as nothing, but a "thing" that is nameless and dirty (Pascoe, 2007). This objectification of girls as either "beautiful" or "ugly" continued throughout the discussion.

Intriguingly, the boys also worried about what their children would look if they were dating an "ugly girl" and she fell pregnant: "would the child be ugly like her mother"? Here boys seem to be thinking about the economy of reproduction and again projecting themselves into an ideal future in deciding who should be the mother of their children.

Simon: "But if the girl is nice and fly and hot; and maybe let's say the condom bursts or something; you wouldn't like // like you feel started at first because you are young, but you wouldn't regret having a child with her, because she is beautiful."

William: "It's like a jackpot!"

In this group interview, William supports Simon's view that having a child with a beautiful girl is like winning "a jackpot". It is interesting to note that in this context, unplanned pregnancy is celebrated and great value is attached to having a child with a "hot" girl. It is possible that boys might have been posturing in the groups when producing this kind of sexist talk. Nevertheless, there is a suggestion that it is every boy's wish to date, get married and have children with a beautiful girl. This involves what Hollway (1989) calls the "commercialisation" of women in terms of their good looks. When boys were asked to elaborate on their expectations in the relationships with pretty girlfriends, Simon said, "It is status. I had sex with this girl".

Kann's research (2008) found that boys feel entitled to have sex with girls. It is only through having sex that boys are able to claim their positions as "real" boys. The findings in this study are consistent with Kann's (2008) and also Khunwane's (2008) findings. Sexual activity is interwoven with masculine identity. Being sexually active boosts boys' status in the male peer group, especially if the girl is pretty. Boys also seem to feel more powerful and competent for having had sex with a beautiful girl. It is an achievement that needs to be celebrated with other male peers (Pascoe, 2007). Many young boys see sex as a sport (Lindegger & Maxwell, 2007).

Frosh et al (2003) and Pascoe (2007) reported a tendency amongst boys to speak about the bodies of girls that they fancied and desired. Girls were expected to have sexy bodies:

Thabiso: "For me, I want a slender one." Mpho: "The beauty, the sexy body."

Herman: "But they have forgotten one thing, we want girls who are fit."

In the statements above, girls are clearly objectified as sex objects and the informants support the idea that it is a dream of every boy to have a girlfriend who has "the sexy body" (cf. Pascoe, 2007). In supporting the objectification of girls, Herman reminds his fellow group members that they have forgotten to mention an important thing, that girls must also be "fit". All these boys seem to be drawing on popular discourses where there is constant pressure on young girls and women to "watch their weight" (Szabo & le Grange, 2002) and strive for slenderness (Edwards & Moldan, 2004). The thinness of girls was clearly associated with beauty, glamour and being sexy.

PHOTOGRAPHS REPRESENTING ALTERNATIVE YOUNG MASCULINITIES

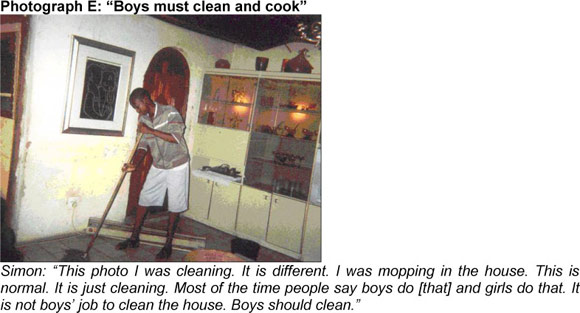

Not all photographs taken by boys represented traditional views of young masculinities. Some of the photographs included boys cleaning, cooking, washing clothes, going to church and reading or studying at school (see photographs E to G). With these photographs, it seems as though the participants are contesting, rejecting and resisting hegemonic norms of masculinity. However, this process comes with emotional tensions and contradictions.

In the above photographs, the boys seem to be rejecting the gender stereotype that only girls must clean the house, wash dishes and cook. Both Simon and Peter contend that boys should also do house chores. It seems that some boys are embracing alternative versions of young masculinities and showing some positive reception to aspects of gender equality (cf. Segal, 1990). Taking this step is not easy because it involves exposing oneself to ridicule and being called derogatory names such as "moffie" (Ratele et al, 2007), "man-woman" (Ampofo & Boateng, 2007) or "sissy" (Frosh, Phoenix & Pattman, 2002; Pascoe, 2007). Both Simon and Peter were embarrassed to show these particular photographs of themselves cleaning and cooking to other boys in the group interview. Their narratives in the group interview were also not the same as the narratives they shared in the individual interviews, namely that it was an acceptable that boys clean and cook. In the group interview, they joked about their roles in the photographs and made comments that were clearly belittling to girls and gay boys. It seems both Simon and Peter struggled to hold onto alternative versions of masculinity in a group setting and instead conformed to socially acceptable views about what it means to be a "real" boy (cf. Butler, 1990). They confirmed observations that in a group, boys feel pressurised to conform to the norms of hegemonic masculinity (Connell, 1995; Frosh et al, 2002; Lindegger & Maxwell, 2007; Ratele et al, 2007).

In the study, it became evident that there are different "types" of boys at school in Alexandra, for example, tsotsi boys and cool boys. Tsotsi boys are boys that miss classes, defy teachers' authority and perform poorly at school. Conversely, cool boys conform to school rules and perform well academically. Tommy classifies himself as one of the cool boys because he values academic achievement. It seems both tsotsi and cool boys compete for power, visibility, legitimacy and dominance in the school environment. Tsotsi boys hold more power outside the classroom context, on the soccer fields or during break in the toilets, while cool boys hold more power in the classroom context, due to their active participation in answering maths and science-related questions and doing school homework. However, because of this, cool boys are accused by tsotsi boys of being "teachers' pets" or "Mr.Goodboys":

Herman: "Ja, they sometimes call me that you are acting like you know it all, when I am holding books, you think you are Mr. Goodboy".

Simon: "They are labelled as losers...they are teachers' pets. And other boys refer to them as snaai [fool].

It seems that cool boys are consistently the target of insults. They are teased and called derogatory names such as "losers" and "snaai" [fools]. Cool boys complain that tsotsi boys are not only popular with teachers, but also popular with girls:

Simon: "But then if you disrespect the teachers you become popular in that group of becoming popular, in that bad way. But then if you play sport, and not being teachers' pet necessarily, and you [don't] do your home work, you become popular amongst the girls. And the girls would like you that this guy".

Nathan: "...// I don't know, these girls of these days, when they see a boy drinking, smoking and missing classes they get proud of the boy".

Despite their commitment to their studies, as represented in some of the photographs, cool boys feel disadvantaged, and feel girls don't like them, "especially girls of these days". Simon complains that "you don't do your homework but girls would like this". In talking to girls, Frosh et al (2003) found that they do like more academically inclined boys because they do not harass or abuse girls and they also respect their teachers. However, girls tend not to view them as potential boyfriends. Girls see such boys as being too effeminate and lacking the key characteristics of hegemonic masculinity, those of roughness and toughness. Cool boys are still puzzled by girls' preference for tsotsi boys as potential boyfriends, and it is clear in the extract below that some of the boys who classify themselves as cool boys feel conflicted and ambivalent about their masculine identities:

William: "Yes. It's like I am that simple guy. I wouldn't say I am popular, I wouldn't say I am a looser. I feel that I am in-between."

Simon: "Ya, being like in-between, you wouldn't impress people doing bad things. And again you wouldn't be that guy that doesn't socialise, like you lock yourself out."

Here boys talk about the benefits of being "in-between". It is better to be a "simple guy" who is neither popular nor a "loser". However, being in the middle is a dilemma, in that they want to do well academically, but they do not want to be boxed-in as teachers' pets or sissy boys. They still want to be considered to be "real" boys by doing what other boys do (for example, socialising and spending time with other boys at the street corners). The balance is difficult to achieve. It is clear that being a cool boy is not an uncomplicated identity. Like adolescent boys in Reay's (2003) study, both William and Simon are also caught between two opposing positions: attempting to make sure that their tough masculinities are kept intact and simultaneously still endeavouring to maintain academic success. Thus, the discussions around self-representations of oneself as bookish or academic led to an examination of the contradictions in adolescent masculinity and the costs of adopting what are perceived as non-popular masculine positions.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In conclusion, the photo-narrative method has proved to be an innovative and creative research tool in researching young masculinities amongst adolescent boys in Alexandra. This research method allowed young adolescent boys to represent their worlds through "their own lived experiences" and as actors in the processes of storytelling and explaining their photographs. The onus was also on the research participants to take responsibility for producing and reproducing their own biographies in the images taken, explaining their sense of their masculine identities and their perceptions of masculinity as well as who they want to be in the future. This process was reflexive in allowing boys to develop new ways of thinking about themselves as young adolescent boys. At close inspection, the photographs also revealed the participants' emotional worlds and the contradictions in negotiating multiple meanings of masculinity. Through their photographs, many boys were comfortable talking to me, as the researcher, about ambivalent identifications, risk-taking behaviours, uncertainties over friendships and disappointment with girlfriends. It is clear in the boys' photo-narratives that they draw upon multiple voices and versions of masculinity. These voices are unstable, contradictory and fluid. Boys continuously occupy multiple positions along the continuum of being a "new" or "traditional" boy (Ratele et al, 2007). Boys also appear to simultaneously accept and reject certain norms of masculine identities, depending on the context in which they find themselves (for example, being at home with parents or at school with male peers in a group). There was however some evidence that some boys were slowly embracing alternative voices of young masculinities. However, this is not an easy process and comes with considerable emotional costs, sacrifices and feelings of self-doubt. The photo-narrative method served as a useful research tool in exploring multiple voices of masculinity amongst this sample of adolescent boys in Alexandra.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to take this opportunity to thank my PhD supervisor, Gill Eagle, for her in-depth, detailed editorial and constructive comments on the first draft of this article. Thanks also to Graham Lindegger (the SANPAD project leader), Peace Kiguwa and the anonymous reviewers for their detailed reviews. Lastly, thanks to all the boys who took their time to take photographs and participate in the interviews.

REFERENCES

Alexander, S M (2003) Stylish hard bodies: Branded masculinity in Men's Health Magazine. Sociological Perspectives, 46 (4), 535-554. [ Links ]

Ampofo, A A & Boateng, J (2007) Multiple meanings of manhood among boys in Ghana, in Shefer, T, Ratele, K, Strebel, A, Shabalala, N & Buikema, R (eds). From boys to men: Social constructions of masculinity in contemporary society. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Bhana, D (2005) Violence and the gendered negotiation of masculinity among young black school boys in South Africa, in Ouzgane, L & Morrell, R (eds), African masculinities: Men in Africa from the late 19th century to the present. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Blackbeard, D & Lindegger, G (2007) Building the wall around themselves: Exploring adolescent masculinity and abjection with photo-biographical research. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(1), 25-46. [ Links ]

Butler, J (1990) Gender trouble. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Collier, J & Collier, M (1986) Visual anthropology: Photography as a research method. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. [ Links ]

Connell, R W (1995) Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Edley, N & Wetherell, M (1995) Men in perspective: Practice, power and identity. Maylands Avenue: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Edwards, D & Moldan, S (2004) Bulimic pathology in black students in South Africa: Some unexpected findings. South African Journal of Psychology, 34(2), 191-205. [ Links ]

Gilbert, R & Gilbert, P (1998) Masculinity goes to school. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. [ Links ]

Freeman, M (1993) Seeking identity: Township youth and social development. South African Journal of Psychology, 23(2), 157-167. [ Links ]

Frosh, S, Phoenix, A, & Pattman, R (2002) Young masculinities: Understanding boys in contemporary society. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Frosh, S, Phoenix, A, & Pattman, R (2003) Young masculinities: The trouble. The Psychologist, 16(2), 84-86. [ Links ]

Gibson, D & Lindegaard, M R (2007) South African boys with plans for the future: Why a focus on dominant discourses tells us only a part of the story, in Shefer, T, Ratele, K, Strebel, A, Shabalala, N & Buikema, R (eds) From boys to men: Social constructions of masculinity in contemporary society. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Glaser, C (2000) Bo-tsotsi: The youth gangs of Soweto, 1935-1976. London: Heineman. [ Links ]

Haywood, C & Mac an Ghaill, M (1996) Schooling masculinities, in Mac an Ghaill, M (ed) Understanding masculinities. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Hollway, W (1989) Subjectivity and method in psychology: Gender, meaning and science. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Hunter, M (2005) Cultural politics and masculinities: Multiple-partners in historical perspective in KwaZulu-Natal, in Reid, G, & Walker, L (eds) Men behaving differently. Cape Town: Double Storey. [ Links ]

Kann, L (2008) Youth and sex - a dangerous game: Male adolescents' perceptions and attitudes towards sexual consent. Unpublished Masters thesis: University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Khunwane, M N (2008) Exploring the perceptions of sexual abstinence amongst a group of young black students. Unpublished Masters thesis: University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Langa, M & Eagle, G (2008) The intractability of militarized masculinity: Interviews with former combatants in East rand. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(1), 152-175. [ Links ]

Lindegger, G & Maxwell, J (2007) Teenage masculinity: The double bind of conformity to hegemonic standards, in Shefer, T, Ratele, K, Strebel, A, Shabalala, N & Buikema, R (eds) From boys to men: Social constructions of masculinity in contemporary society. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Mokwena, M (1991) The era of the Jackrollers: Contextualising the rise of youth gangs in Soweto. Paper presented at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, Seminar No. 7, 30 October 1991. [ Links ]

Mtebule, N (2003) Identity in the making: Researching young black urban masculine identity in the post-apartheid era. Unpublished Masters thesis: University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Niehaus, I (2005) Masculine domination in sexual violence: Interpreting accounts of three cases of rape in the South African Lowveld, in Reid, G & Walker, L (eds) Men behaving differently. Cape Town: Double Storey. [ Links ]

Noland, C M (2006) Auto-photography as research practice: Identity and self-esteem research. Journal of Research Practice, 2(1), 1-19. [ Links ]

Pascoe, C J (2007) Dude, you're a fag: Masculinity and sexuality in high school. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Pattman, R (2005) "Ugandans," "cats" and others: Constructing student masculinities at the University of Botswana, in Ouzgane, L & Morrell, R (eds) African masculinities: Men in Africa from the late 19th century to the present. Pitermaritzburg: UKZN Press; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ratele, K, Fouten, E, Shefer, T, Strebel, A, Shabalala, N, & Buikema, R (2007) "Moffies, jock and cool guys": Boys' accounts of masculinity and their resistance in context, in Shefer, T, Ratele, K, Strebel, A, Shabalala, N & Buikema, R (eds) From boys to men: Social constructions of masculinity in contemporary society.Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Reay, D (2003) Troubling, troubled and troublesome? Working with boys in the primary school, in Skelton.C, & Francis, B (Eds). Boys and girls in the primary classroom. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Renold, E (2004) "Other boys": Negotiating non-hegemonic masculinities in the primary school. Gender and Education, 16(2), 654-63. [ Links ]

Seedat, M, Baadtjies, L, van Niekerk, A & Mdaka, T (2006) Still photography provides data for community-based initiatives. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 16(2), 303-314. [ Links ]

Segal, L (1990) Slow motion: Changing masculinities changing men. London: Virago. [ Links ]

Seidler, V J (2006) Young men and masculinities: Global cultures and intimate lives. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Solomon, K (1982) The masculine gender role: Description, in Solomon, K & Levy, N B (eds) Men in transmission: Theory and therapy. New York: Plenum. [ Links ]

Stevens, G & Lockhart, R (1997) Coca-cola kids: Reflections on black adolescent identity development in post apartheid South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 27(4), 250-266. [ Links ]

Stevens, G and Lockhat, R (2003) Black adolescent identity during and after Apartheid, in Ratele, K & Duncan, N (eds) Social psychology: Identities and relationships. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Szabo, C P & le Grange, D (2002) Eating disorders and the politics of identity: The South African experience, in Nasser, M, Katzman, M & Gordon, R (eds) Eating disorders and cultures in transition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Xaba, T (2001) Masculinity and its malcontents: The confrontation between 'struggle masculinity' and 'post-struggle masculinity' (1990-1997), in Morrell, R (ed.) Changing men in Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. [ Links ]

1 The article is based on my PhD research. As part of data collection for my PhD I use photo-narrative as a research tool to explore multiple voices of masculinity with adolescent boys in Alexandra Township. The research is part of the broader project funded by the South African Netherlands Partnership on Alternative Development (SANPAD).

2 All names have been changed to protect the privacy of the participants.