Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Sports Medicine

On-line version ISSN 2078-516X

Print version ISSN 1015-5163

SA J. Sports Med. vol.26 n.4 Bloemfontein 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJSM.543

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

DOI:10.7196/SAJSM.543

Junior cricketers are not a smaller version of adult cricketers: A 5-year investigation of injuries in elite junior cricketers

R A Stretch

DPhil; Sport Bureau, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Injury surveillance is fundamental to preventing and reducing the risk of injury

OBJECTIVES: To determine the incidence of injuries and the injury demographics of elite schoolboy cricketers over five seasons (2007 - 2008, 2008 - 2009, 2009 - 2010, 2010 - 2011 and 2011 - 2012

METHODS: Sixteen provincial age group cricket teams (under (U) 15 , U17 and U18) competing in national age-group tournaments were provided a questionnaire to complete. The questionnaires gathered the following information for each injury sustained in the previous 12 months: (i) anatomical site; (ii) month; (iii) cause; (iv) whether it was a recurrence of an injury from a previous season; (v) whether the injury had reoccurred during the current season; and (vi) biographical data. Injuries were grouped according to the anatomical region injured. All players were invited to respond, irrespective of whether an injury had been sustained, resulting in a response rate of 57%. The sample Statistical Analysis System was used to compute univariate statistics and frequency distributions

RESULTS: Of the 2 081 respondents, 572 (27%) sustained a total of 658 injuries. The U15 and U17 groups sustained 239 (36%) and 230 (35%) injuries, respectively, more than the 189 injuries sustained by the U18 group (29%). These injuries were predominantly to the lower limbs (38%), back and trunk (33%) and upper (26%) limbs, with 3% occurring to the head and neck. The injuries occurred primarily during 1-day matches (30%), practices (29%) and with gradual onset (21%). The primary mechanism of injury was bowling (44%) and fielding (22%). The injuries were acute (49%), chronic (41%) and acute-on-chronic (10%), with 26% and 47% being recurrent injuries from the previous and current seasons, respectively. Some similar injury patterns occurred in studies of adult cricketers, with differences in the nature and incidence of injuries found for the various age groups. The youth cricketers sustained more back and trunk injuries, recurrent injuries and more match injuries than the adult cricketers. The U15 group sustained less-serious injuries, which resulted in them not being able to play for between 1 and 7 days (58%), with more injuries occurring in the preseason period (24%) and fewer during the season (60%) compared with other age groups. The U15 and U17 groups sustained the most lumbar muscle strains, while the U18 groups sustained more serious injuries, resulting in them not being able to play for >21 days

CONCLUSION: Young fast bowlers of all ages remain at the greatest risk of injury. Differences in the nature and incidence of injuries occurred between youth and adult cricketers, as well as in the different age groups. It is recommended that cricket administrators and coaches implement an educational process of injury prevention and management

Injuries in elite adult cricketers have been well researched over the years, with long-term injury surveillance being carried out in Australia,[1] England[2] and South Africa (SA).[3] However, there remains a relative lack of published studies on injury patterns and risk factors in young cricket players, particularly studies reporting injuries with large sample sizes and over more than one season. Seven studies have described injuries in junior cricketers in SA,[4-7] Australia[8,9] and New Zealand.[10] These studies reported that young cricketers sustain proportionally less overuse injuries than elite players, but were more susceptible to acute traumatic injuries.

In a retrospective study on schoolboy cricketers,[4] the seasonal incidence of injury was reported to be 49%, with the most common sites of injury being the back and trunk (33%), and upper (25%) and lower (23%) limbs. Bowlers sustained more injuries (47%) than batsmen (30%) and fielders (23%). The injuries occurred equally during matches (46%) and practices (47%), with 30% of the injuries recurrent from previous seasons and 37% recurring again during the same season.

A 34% seasonal incidence, with injuries occurring during matches (72%) throughout the season due to repetitive stresses sustained during matches and practices (15%), during practice (12%) and during other forms of training (1.5%), was reported for 196 schoolboy cricketers who competed in an under (U) 19 provincial competition.[5 Bowling accounted for 51% of the injuries, fielding 33%, batting 15% and the remaining 1.5% occurred while warming up or training. The primary mechanism of injury occurred during the delivery stride and follow-through of the fast bowler (34%). A large number of injuries (41%) reported were severe and took the cricketers >21 days to recover.

Adolescent cricketers reported musculoskeletal injury in the lower (39%) and upper (36%) limbs and the lower back (18%).[6] Direct physical trauma and overuse were the main causes of this musculoskeletal pain, with the knee being the primary site of injury.

Findings for the current study were reported after the initial 3-year period and showed that 366 (28%) of the 1 292 respondents sustained a total of 425 injuries.[7] The U15 and U17 groups sustained 166 (39%) and 148 (35%) injuries, respectively, more than the 111 injuries sustained by the U18 group (26%). These injuries were predominantly to the lower (46%) and upper (35%) limbs, and occurred primarily during 1-day matches (31%), practices (27%) and with gradual onset (21%). The primary mechanism of injury was bowling (45%) and fielding, including running to field the ball (33%). Forty-two lumbar muscle strains, 18 hamstring strains, 17 spondylolisthesis injuries and 17 ankle sprains occurred. The injuries were acute (50%), chronic (42%) and acute-on-chronic (8%), with 24% and 46% being recurrent injuries from the previous and current seasons, respectively. Slight differences in the nature and incidence of injuries were found for the various age groups. The U15 group sustained less-serious injuries, which resulted in them not being able to play for between 1 and 7 days (54%), with more injuries occurring in the preseason period (28%) than the other groups. The U17 group sustained the most lumbar muscle strains (n=23), while the U18 group sustained more serious injuries, with 60% of the injuries resulting in not being able to play for >8 days.

Traditional cricket was associated with more injuries than modified cricket, with batting (49%) and fielding (29%) accounting for the majority of injuries. Impact by the ball was responsible for 55% of the injuries. The introduction of compulsory wearing of protective head gear when batting resulted in a decrease in head, neck and facial injuries from 62% to 35% to 4% over a three-season period.[8]

In junior club cricketers, injury rates increase with age and level of play,[8] and injuries to fielders and batsmen occur as frequently as to bowlers.[9] Match injury rates (per 1 000 participations) were 3.57 for U14 participations compared with 4.80 for U16 participations. Training injury rates were 4.20 per 1 000 U14 participations compared with 5.11 per 1 000 U16 participations. In matches, more injuries occurred while batting and fielding, while more injuries occurred while bowling and batting during training sessions. Most of the 47 injuries were acute and traumatic in nature, with many associated with being struck by the ball.

Data on the cricketers hospitalised after sustaining an injury showed differences among age groups, with 50% of the injuries to players <10 years of age being head injuries as a result of being struck by the bat.[10] Those cricketers between the ages of 10 and 19 years sustained head (34%), upper (28%) and lower (29%) limb injuries primarily as result of impact from the bat or ball.

A further four studies have focused on injury prevention strategies in young high-performance fast bowlers in SA,[11] Australia[12] and England.[13,14] In addition, there is a report on injury risk of junior Australian cricketers, associated with ground hardness.[15] In the SA study, 31 of the 46 fast bowlers assessed sustained an injury during the season, with strains to the knee (41%) and lower back (37%) being the most common injuries.[11]

A relationship between a high bowling workload and injury in the young Australian fast bowlers was reported, with the injured bowlers being those who bowled more frequently with shorter rest periods between bowling sessions than uninjured bowlers. The bowlers who bowled more than 50 deliveries per day and who bowled on average more than 2.5 days per week were at the greatest risk of injury.[12]

A study investigating the incidence of injury in young spin and fast bowlers reported fewer injuries for the spin bowlers (0.066 per 1 000 balls) compared with fast bowlers (0.165 per 1 000 balls).[13] In fast bowling, the incidence of injury (per 1 000 balls) was greatest at the knee (0.057), ankle (0.043), lower back (0.029) and shoulder (0.007), while for spin bowlers the shoulder (0.055) and lower back (0.011) were the primary sites of injury. Strategies for the prevention and reduction of lower back injuries in fast bowlers have been undertaken, but there is a need to address shoulder injuries in wrist spinners before it becomes a major concern. The overall incidence of bowling injury was 32.8 injuries per 100 fast bowlers, with bowlers with a workload of <1 000 deliveries showing a lower risk of injury than those with a greater workload.

In a study that assessed the risk of injury associated with ground hardness, Twomey et al.[15] categorised field hardness as unacceptably hard (>120 gravities (G)), high/normal (90 - 120 G), preferred range (70 - 89 G), low/normal (30 - 69 G) and unacceptably soft (<30 G). Grounds rated as having unacceptably high hardness (82%) resulted in 6.5% of the 31 injuries sustained, which included grazes and lacerations sustained when diving to catch the ball. A further 16.1% were possibly related to the ground hardness, indicating either that the low injury rates may be as a result of players changing their behaviour when playing on hard surfaces, i.e. not diving to field or catch the ball, or that ground hardness is a true reflection of the risk of injury, and harder grounds are needed to play cricket.[15]

Injury surveillance is fundamental for preventing and reducing the risk of injury. However, it is not appropriate to use the data from adult injury surveillance studies to design coaching and training programmes to reduce injuries in young cricketers. Therefore, the objective of this study was to expand on the first 3 years of this study[7] in order to understand the seasonal incidence of injuries and injury demographics between elite schoolboy cricketers across player age groups and to make recommendations to protect these young cricketers from injury.

Method

The sample comprised provincial cricketers competing in three national age-group cricket tournaments (U15, U17 and U18) from the 2007 - 2008, 2008 - 2009, 2009 - 2010, 2010 - 2011 and 2011 - 2012 seasons, with some players participating in multiple tournaments during that period. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University's ethics committee. A questionnaire was handed out to all the players by the team coach, and they were required to complete the questionnaire, irrespective of whether an injury had been sustained or not. The questionnaire was designed to obtain the following information for each injury: (i) anatomical site; (ii) month; (iii) cause; (iv) whether it was a recurrence of a previous injury; (v) whether the injury had reoccurred during the season; and (vi) biographical data. No other medical records or records of other sports played were obtained.

An injury was defined as an injury that prevented a player from being fully available for selection for a match or which prevented the player from completing the match, with all injuries classified according to the Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS).[16]

Injuries were grouped according to the anatomical region injured as follows: (i) head, neck and face; (ii) upper limbs; (iii) back and trunk; and (iv) lower limbs. Injuries were classified according to whether they were sustained during batting, bowling, fielding (including catching and wicket-keeping), fitness training and other. The time of the year when the injury occurred was recorded, with off-season being the time of the year when no specific cricket practice or matches took place (April - July). The pre-season (August and September) was that part of the year when specific cricket training and practice were undertaken in preparation for the season and before the commencement of matches. The season (October - March) was defined as the period when matches were played.

To allow comparisons to be made between the phases of play during which the injuries were sustained, the number of injuries was expressed as a percentage of the total number of injuries sustained. Similarly, to allow comparisons to be made between the injuries sustained by the players in the various age groups, the number of injuries was expressed as a percentage of the number of injuries sustained in that particular age group.

All personal and injury data were precoded, double-entered and edited before being transferred to the sample Statistical Analysis System (SAS) to compute univariate statistics and frequency distributions.

Results

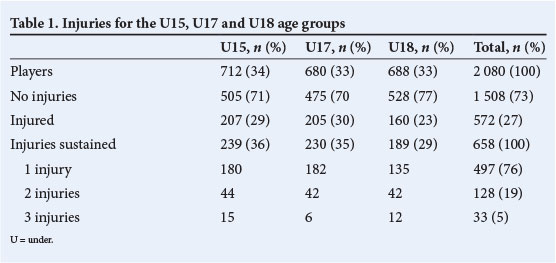

The response rate was 57%. Of the 2 080 respondents, 712 (34%) were U15, 680 (33%) were U17 and 688 (33%) were U18. Of these, 1 508 did not sustain any injury, while the other 572 players sustained 658 injuries, with 497 players sustaining 1 injury, 64 sustaining 2 injuries each (128 injuries) and 11 sustaining 3 injuries each (33 injuries) (Table 1). Of the 658 injuries sustained, similar patterns were found for the three age groups, with the U15 sustaining 239 (36%) injuries, the U17 sustaining 230 (35%) injuries and the U18 groups sustaining 189 (29%) injuries.

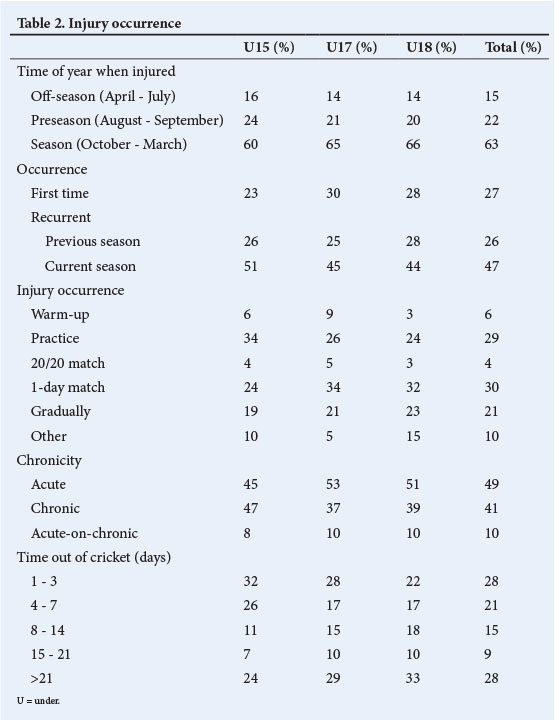

The injuries occurred primarily during the season (63%) (Table 2). New injuries accounted for 27% of the injuries, while 26% were recurrent injuries from the previous season and 47% of the injuries recurred during the same season.

The injuries occurred primarily during 1-day matches (30%), practice (29%) or were of gradual onset (21%), with differences for the various age groups. The younger players (U15) sustained more injuries in practice (34%) and less in 1-day matches (24%) than the older players. Similar injury patterns occurred for the older (U17 and U18) players, with injuries occurring mostly during 1-day matches. Similarly, the U15 players sustained more chronic and less acute injuries than the U17 and U18 groups, which showed similar injury patterns to each other. The U15 players sustained more injuries during the warm-up or playing other sports such as touch rugby, as part of the training session (Table 2).

The length of time that the players were unable to train or play matches due to injuries showed that 49% of the injuries were less-serious injuries (1 - 7 days), with injuries of this nature occurring less with increasing age groups (U15: 58%; U17: 45%; U18: 39%). U18 players sustained more serious injuries (33%) than the U17 (29%) and U15 (24%) groups, which resulted in them being unable to practise or play matches for >21 days (Table 2).

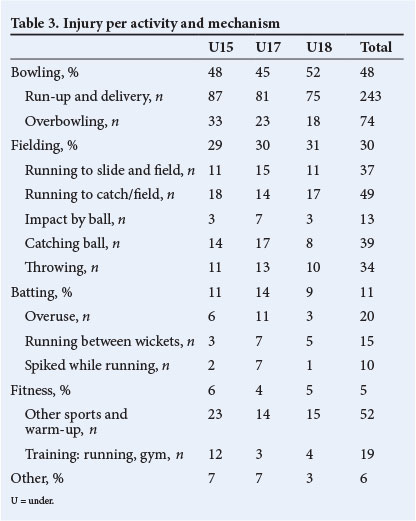

The primary activity leading to injury was bowling (48%), with the runup and delivery the primary mechanisms of injury (Table 3). Bowling injuries were acute in nature, showing a similar pattern for the three age groups. This was followed by injuries of a chronic nature as a result of over-bowling, with more occurring in the U15 group than the older groups. The second major activity resulting in injury was catching, fielding and throwing (30%), with similar findings for all three age groups. In batting injuries (11%), the primary cause of injury was batting for a long period of time, as well as running between the wickets.

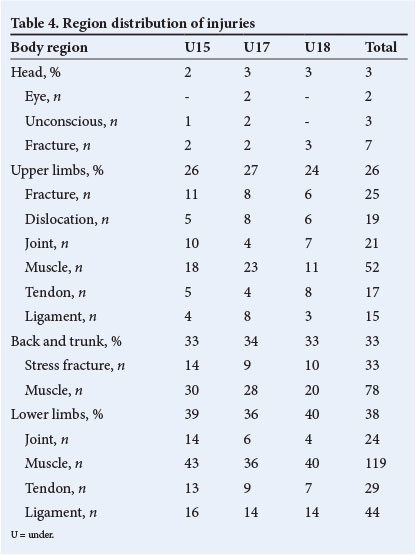

The regional distribution of injuries (Table 4) showed similar patterns for the age groups, with injuries predominantly to the lower limbs (38%), back and trunk (33%) and upper limbs (26%). Lower-limb injuries were predominantly soft-tissue injuries to muscles (n=119), ligaments (n=44) and tendons (n=29). Back and trunk injuries were predominantly muscle (n=78) and stress fracture (n=33) injuries, with the younger players sustaining more stress fractures than the other two groups.

The overall injuries were mainly muscle strains (32%), acute sprains (18%) and fractures (15%), which comprised stress (9%) and acute (6%) fractures.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study was that while there are similar findings with regard to bowlers being at the greatest risk of injury and the lower limbs being the most commonly injured site, the injury patterns for schoolboy cricketers differ in a number of areas to those of adult cricketers.

The findings of adult studies[1-3] report that bowlers were at the greatest risk of injury (sustaining between 40 and 45% of the injuries), with the primary mechanism of injury being delivery and follow-through (25%). Similarly, the primary activity for injury to schoolboy cricketers was bowling (48%), with run-up and delivery the primary mechanisms of injury. The next major activities resulting in injury were to the adult fielders (25 - 33%) and batsmen (17 - 21%), with the schoolboys showing similar findings for fielders (30%), but less risk of injury while batting (11%).

Similar injury patterns were found for the lower limbs (adult 45 -49.1%; schoolboy 38%) and upper limbs (adult 23 - 29%; schoolboy 26%). However, schoolboy cricketers sustained more back and trunk injuries (33%) than the adult cricketers (18.1 - 23%).

While the injuries to adult cricketers were predominantly sustained during matches (52 - 58%), schoolboy players sustained injuries during 1-day matches (31%), practice (29%) and gradual onset (21%). Adult cricketers' injuries occurred during the first 2 months of the season (35%), while the majority of injuries to schoolboy players occurred throughout the season (63%).

The findings show a large difference between the nature of injuries. Between 65 and 92% of the adult injuries sustained were new injuries, between 8 and 22% were recurrent injuries from the previous season and 12% recurred in the same season.[1-3] New injuries accounted for 27% of the injuries for schoolboy cricketers, while recurrent injuries accounted for 73% of the injuries: 26% from the previous season and 47% recurring during the same season.

The chronicity of the injuries showed a difference between the two groups for acute (adult cricketers 65%; schoolboy cricketers 49%) and chronic (adult cricketers 23%; schoolboy cricketers 41%) injuries, with a similar pattern for injuries of an acute-on-chronic nature (adult cricketers 10%; schoolboy cricketers 10%). Schoolboy cricketers sustained more bowling overuse injuries (11%) than adult cricketers (9%), but fewer batting overuse injuries (3%) than adult cricketers (7%).

A closer look at the rate of injury and injury patterns with regard to age reveals further differences. Younger U15 players sustained more chronic and less acute injuries than older players, and more injuries in practice than in matches. One of the possible reasons could be that the younger players generally do not play as many matches for their school as the U17 and U18 players. However, whether playing a match or not, they would still attend the same number of weekly practices as the older players. Coaches need to be aware of potential risk factors and modify the practice sessions to avoid excessive injuries during practices. However, in order to achieve this, evidence-based research is needed to provide coaches with the necessary guidelines.

The rate of injury did not increase with age as previously found in junior club cricketers,[9] which could be as a result of the lower age group of the players represented in the earlier study, as well as the modified nature of the games for these younger players. However, the severity of the injury increased as the age of the players increased, with the younger players sustaining less-serious injuries, U17 players sustaining moderately serious injuries and U18s sustaining more-serious injuries. Players and coaches need to be aware of this and adapt their match, practice and training programmes to try to reduce the risk of injury in the various age groups. However, this requires additional research to provide coaches with the necessary guidelines.

The findings of the first 3 years of this study[7] show a number of areas that are very similar and which reflect the injury profile staying the same from year to year. These include bowling being the greatest cause of injury, with the majority of injuries being to the lower limbs, and a similar pattern of U18 cricketers sustaining fewer injuries, but of a more serious nature and resulting in being out of cricket for a longer period of time. While recommended guidelines have been established with the view of reducing the risk of injury in young fast bowlers,[17] it would appear that these are not being followed.

Similar to previous studies on adult cricketers,[1-3] where bowling was the primary cause of overuse injuries, the run-up and delivery were the primary mechanisms of injury in the current study, with a similar pattern for the three age groups. While more overuse injuries occurred in the U15 group than the older groups, the rate of stress fractures increased with the age and level of play for the U15 (8%) to the U17 (10%) and U18 (12%) players. The current study showed similar findings with regard to practice and match injuries as the studies of junior club cricketers[9] and elite senior cricketers.[1-3] However, there was a decrease in injuries in practice as the age and level of play increased, and an increase in match injuries as the age and level of play increased.

Therefore, it is important that schools, clubs, and players, coaches and parents, continue to monitor the workloads of these young bowlers to ensure that they do not exceed the recommended guidelines.[17] At particular risk are fast bowlers who practise and play for their school during the week, in addition to practising with an adult club team during the week and playing matches for them over the weekend. In addition, young fast bowlers need to use an appropriate technique and be adequately conditioned to deal with the demands of fast bowling.

Conclusion

As in the previous reports on adult cricketers, young cricketers show similar findings with regard to bowlers being at the greatest risk of injury, and the lower limbs being the most commonly injured site. However, there were areas where the injury patterns for schoolboy cricketers differed to those of adult cricketers, with further differences in the injury patterns between the different age groups and level of play.

The primary goal of all involved with the administration, coaching, training and playing of cricket at schoolboy level should be to protect young cricketers from injury. Here, education is key, particularly with respect to the reduction and prevention of overuse injuries to young fast bowlers. This study is important to key role-players, as it provides details of the effect of practice and matches, role of the player in the team and the mechanism of injury to players at different ages and levels of play. However, further research is required in a number of areas, including providing coaches with evidence-based results that could assist with optimum coaching, training and practice methods to optimise technical and tactical skills while reducing the risk of injury, particularly in younger players who do not play as many matches, but still need to attend practice sessions.

Finally, the differences in injury patterns between schoolboy and adult cricketers should reinforce that young cricketers are not a smaller version of adult cricketers, and point to a need for different types of practice and match play at different ages and levels of play.

References

1. Orchard J, James T, Alcott E. Injuries in Australian cricket at first class level 1995/1996 to 2000/2001. Br J Sports Med 2002;36(4):270-275. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.36.4.270] [ Links ]

2. Leary T, White J. Acute injury incidence in professional country club cricketer (19851995). Br J Sports Med 2000;34(2):145-147. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.34.2.145] [ Links ]

3. Stretch RA, Venter DJL. Cricket injuries: A longitudinal study of the nature of injuries to South African cricketers. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 2005;17(2):4-9. [ Links ]

4. Stretch RA. The incidence and nature of injuries in schoolboy cricketers. S Afr Med J 1995;85(11):1182-1184. [ Links ]

5. Millsom NM, Barnard JG, Stretch RA. Seasonal incidence and nature of cricket injuries among elite South African schoolboy cricketers. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 2007;19(3):80-84. [ Links ]

6. Noorbhai M H, Essack FM, Thwala SN, Ellapen TJ, Van Heerden JH. Prevalance of cricket-related musculosketal pain among adolescent cricketers in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 2012;24(1):3-9. [ Links ]

7. Stretch RA, Trella C. A three-year investigation into the incidence and nature of cricket injuries in elite South African schoolboy cricketers. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 2012;24(1):10-14. [ Links ]

8. Shaw L, Finch C. Injuries to junior club cricketers: The impact of helmet regulations. Br J Sports Med 2008;42(6):437-440. [ Links ]

9. Finch CF, White P, Dennis R, Twomey D, Hayden A. Fielders and batters are injured too: A prospective cohort study of injuries in junior club cricketers. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13(5):489-495. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2009.10.489] [ Links ]

10. Walker HL, Carr DJ, Chalmers DJ, Wilson CA. Injury to recreational and professional cricket players: Circumstances, type and potential for intervention. Accid Anal Prev 2010;42(6):2094-2098. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.06.022] [ Links ]

11. Davies R, Du Randt R, Venter DJL, Stretch RA. Cricket: Nature and incidence of fast-bowling injuries in elite, junior level and associated risk factors. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 2008;20(4):115-118. [ Links ]

12. Dennis RJ, Finch CF, Farhart PJ. Is bowling workload a risk factor for injury to Australian junior cricket fast bowlers? Br J Sports Med 2005;39(11):843-846. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.018515] [ Links ]

13. Gregory PL, Batt M, Wallace W. Comparing injuries of spin bowlers with fast bowlers in young cricketers. Clin J Sport Med 2002;12(2):107-112. [ Links ]

14. Gregory PL, Batt M, Wallace W. Is the risk of fast bowling injury in cricketers greatest in those who bowl the most? Br J Sports Med 2004;38(2):125-128. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2002.000275] [ Links ]

15. Twomey DM, White PE, Finch CF. Injury risk associated with ground hardness in junior cricket. J Sci Med Sport 2012;15(2):110-115. [http://dx doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.08.005] [ Links ]

16. Orchard JW, Newman D, Stretch R, Frost W, Manshing A, Leious A. Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. J Sci Med Sport 2005;8(1):1-14. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1440-2440(05)80019-2] [ Links ]

17. Stretch RA, Gray J. Fast bowling injury prevention. Johannesburg: United Cricket Board of South Africa Publication, 1998 [ Links ]

Corresponding author: M Lambert (mike.lambert@uct.ac.za)