Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.33 n.2 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2020/v33n2a3

ARTICLES

Religious Associational Life amongst Black African Christian Students at Howard College Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Anthonia Omotola IshabiyiI; Sultan KhanII

IDepartment of Sociology, University of KwaZulu-Natal. paduatonia@yahoo.com

IIDepartment of Sociology, University of KwaZulu-Natal. khans@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Historically, religion has played a key role in the destiny of human beings. It has provided reasons for its existence and shaped the social, cultural, economic, and political behavior of individuals and society. Specifically in the 21st century, the globe has become a multi-faith space with diverse religious philosophies, ways of religious expressions, norms, and values. For the young university students, it provides a space for critical reflection, awareness of one's self and an environment in which one's values and norms are tested and perhaps reshaped. Given the abstractness of the university environment and exposure to a vast range of beliefs and practices, it may challenge the religious belief structure of students to an extent that one may go on to question long held religious beliefs and practices. It is against the background of this context that this article tests the nature of religious associational life of on-campus black African Christian students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Campus. The methodological approach to the study embraced both qualitative and quantitative data gathering tools. Semi-structured self-administered questionnaires were used to gather data. A total of 123 respondents, selected purposively, participated in the study. The results of this study suggest that on-campus, religious associations play an integral role in reinforcing the religious and spiritual identity of students. It impacts both their personal and academic life. Additionally, the study highlights that although religious tolerance featured in the study, there was a need for inter-religious dialogue, given the diversity of faith groups in the country.

Keywords: Religion, association, university life, identity, belief

Introduction1

South Africa is viewed as a very religious nation in which between 85% and 94.1% of the populace consider religion to be an essential part in their lives (Statistics South Africa 2013:32). Given the different religious groupings that constitute the South African way of life, it is no surprise that these are transferred onto a variety of social institutions. Institutions of higher learning as such are not spared from this influence, which provides students with a sense of religious identity and life satisfacion (Diener, Tay, & Myers 2011:1279). The study of religious beliefs and practices in general is a sensitive matter and often not explored. In this regard, this study aims to ascertain how black South African Christian undergraduate students on the Howard College Campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) express their religious identities through religious associations, and the ways in which religion contributes to their life experience on campus. A literature scan in South Africa and in the continent proved a futile exercise. Nonetheless, research undertaken in the more developed parts of the globe provided us with an insight into understanding the nature of the religious associational life among young people. In this instance, journals, periodicals, books, dissertations, and internet articles were reviewed, serving as important reference points to build on knowledge pertaining to youth and religion at a local level. It is in this context that this study aims to ascertain the underlying features of the religious associational life of students on campus through a socio-religious lens, by finding possible explanations on how and why students sustain such associations.

Role of Religion in a Student's Life

Religion is an indispensable issue in various ways in society. It serves as a support system, which guides norms and beliefs through which to decipher one's experiences and encounters, providing it with significance (Park 2007:319; Sherkat 2007:4). Researchers have observed that current students are more religious than those in past eras of college and university life. However, they do not have a clear picture of why. A few investigations assert that religious students are better students, and that religion provides them with different options to other social activities (Donahue & Benson 1995: 156). However, studies on university life fail to consider the bigger picture, since religion, and particularly fundamentalism can affect learning at university negatively. On the contrary, religious factors could be positive as it could affect career goals and promote academic success and the successful completion of a degree (Glass & Jacobs 2005:574).

Religion's commitment to youth development has been conventional and it has been described as a positive influence in youth development and a defensive factor against deviant behavior such as drug addiction and alcohol abuse (Regnerus, Smith, & Fritsch 2003:26). Others have also noticed that religious principles tend to regulate young people' s behavior towards premarital sex and having multiple sexual partners (Odimegwu 2005:127; Donahue & Benson 1995:153). Religion not just appears to help in protecting the youth from bad habits, as it also appears to promote healthy adolescent growth (Regnerus, Smith, & Fritsch 2003:125). Religious students also seem to handle stress more effectively compared to their non-religious peers, since they identify with a religious association and receive adequate support and counseling (Regnerus, Smith, & Fritsch 2003:20). Researchers have also distinguished between religious and non-religious youths. Active religious students have a positive drive to life, are academically driven, have parental support, and have a controlled or balanced social life (Gunnoe & Moore 2002:620).

In many instances, the carryover of one's faith in the context of a diverse university life and culture, provides an opportunity for the extension of religious life during the course of the students' studies. Considering that students are exposed to a wide range of social issues ranging from premarital sex, drug abuse, alcoholism, depression, and so on, religious associations on campus can act as an important safety net to regulate such behavior (Odimeg-wu 2005:126; Galen & Rogers 2004:474). The influential theory of Park (2005) proposes that higher institutions of learning such as colleges and universities provide an important support system, as well as challenges of different kinds that could help to nurture and promote religious growth. As adolescents decide to enter a new community (college or university), religion influences their behaviors, norms, and beliefs, which directly affect their growth as a whole. Religious associations can be an important agency to help students to cope with the stress of life that they may encounter, both within their respective communities and for the duration of their studies (George, Ellison, & Larson 2002:194). It can help students to enlighten themselves about their religious beliefs and practices, protect them from negative behavior that may distract them from their studies, provide them with a sense of belonging, enrich them about different faiths, and provide comfort, given the pressures of the academic life (Regnerus, Smith, & Fritsch 2003:45). Moreover, it provides them with a balance on their spiritual life, academic aspirations and diverse forms of learning that are characteristic of university life (George et al. 2002:194).

Religious Associational Life on Campus

The different campus associations that characterize university life have made a significant impact on universities and their members (Marsden 1994). Religious associations within universities serve as a way to effectively support students in their faith and provide a safe learning environment for them (Mooney 2010:211). In the modern era, religion has been a matter of concern for some researchers and students, particularly with the advent of post-modernism. However, the attitude of the university community and higher education has continued to be uncertain towards religion (Love & Talbot 2000:363). College and university communities are not spared from religious influence, since the attitudes of several students towards religion have obviously increased (Bryant 2005:4). The membership of these organizations has increased in numbers, based on the dedicated time on evangelization and recruitment (Bryant 2005:3). Cases like these lead to questioning the nature of these religious associations and how they come to influence campus students and their academic goals.

Sociologists' increasing interests in the study of religion and youth have focused their arguments on secularization and higher education, though religion has been considered an essential part of student identity. Scholars such as Wuthnow (1988) and Berger (1967) argue that college attendance leads to the evolution from traditionalism to secularization. College attendance serves as a liberalizing factor on students' behaviors and values. Graduates' religious views become less doctrinaire and more personal and the religious tolerance amongst people of different faith groups becomes prevalent (Bryant 2005:5). More recently, Uecker, Regnerus, and Vaaler (2007) have discovered that on the measures of religiosity, adolescents who attended college in the 21st century, experience a bigger decline in their religious belief compared to those who did not attend college. The decline results from a change in traditional religion, less church attendance, and a change in religious doctrines (Pascarella & Terenzini 1991; 2005).

On the other hand, it may be argued that although the youth' s church attendance is low, college attendance may or may not have contributed to this change in religious attendance and affiliation (Uecker, Regnerus, & Vaaler 2007:1669; Mooney 2010:198). Likewise, a national longitudinal survey of freshmen from selective colleges and universities in the USA points out that even though students' religious participation reduces when attending college, it is actually the students who were not religiously inclined in high school that had a lower church attendance, while those who were religiously inclined in high school, were able to cope with their transition to college (Mooney 2010:210). Studies also show a significant outcome of the positive effect of religious attendance on college goals, most specifically among women (Miller & Stark 2002:1400). These observations are made on the assertion that most women are more religiously inclined compared to men. Young women with academic aspirations tend to be studious, hardworking, and likely to complete their degrees (Miller & Stark 2002:1401).

There is also an indication that college residence can affect religious beliefs and values. In a study conducted at two universities in the USA, a comparison between students who stayed at home and those who stayed in residence halls found that there was a decline in religious activities among students who lived on campus. There was also a decline in religious activities among those who stayed at home, due to parental religious values being reinforced and where they were less likely to explore other religious practices (Moos & Lee 1979). Gunnoe and Moore (2002:621) observe that the presence of mentors as well as religious parents and friends positively influenced religious practices and spirituality.

Further study of religion and civic engagement among the youth in the USA, undertaken by Gibson (2008), shows that not attending college was one of the major factors for religious disaffiliation, a lower rate in church attendance, and reduced religious beliefs. A study of religious ways at the University of Minnesota-Morris, cited by Hodges (1999). found that students have an interest in active multi-faith programs that promote a diversity of religious practices. Another study on students' religious affiliation conducted by the Teagle Foundation in New York, claimed that students who are new on campus, are provided with a sense of community by religious associations (Hurtado & Carter 1997:328). They are then more likely to engage in religious and spiritual programs and to become members of other clubs and societies on campus. For instance, they are involved in community outreach programs and participate in cultural and social events, are satisfied with college, and are positive about the college environment where they can ease off academic stress and have more time for extra-curricular activities.

There have been some instances where academic success was positively influenced by religious affiliation. Mooney (2010:211) found that church attendance increases college satisfaction and college marks. In other words, regular attendance to a mosque, church, synagogue, temple, or any religious services offer guidance and organization to students, which has a positive influence on their performance. It was hypothesized that students would benefit from a religious group which provides them with a support system and creates orderliness in their lives (Mooney 2010:211). Furthermore, studies show that certain characteristics of a spiritual person (modesty, uprightness, and selfless service) are positively related to leadership attributes, self-esteem, and development, that is, students who embrace these qualities and values are more likely to be involved in leadership roles (Astin, Astin, & Lindholm 2011:58).

In addition, researchers have found traditional religion to have a negative effect on educational attainment. It shows that fundamentalists are less likely to progress academically as they could be alienated or discriminated against at their religious practices, which reduce participation in their academic work, while some religious associations may demand more time from these students, resulting in them becoming less focused on academics which may lead to social isolation from the mainstream campus life (Jeynes 2003:40).

Methodology

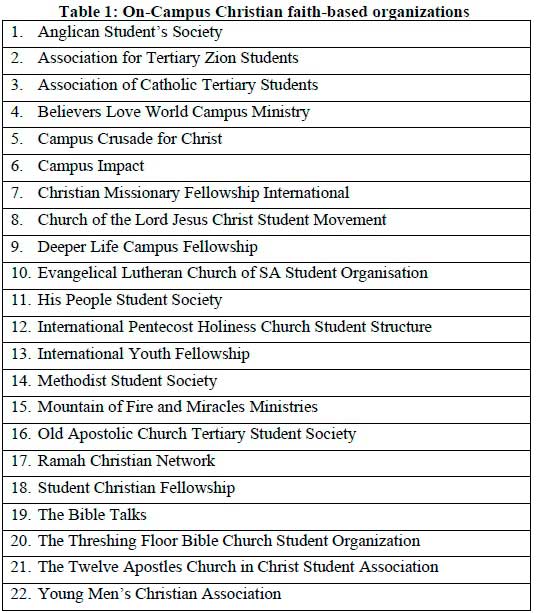

Upon investigation, 22 Christian faith-based organizations were found to be active on the Howard College Campus. The entire population was chosen to participate in the study as listed in Table 1 below. Upon requests to the executive committees of these on-campus faith-based organizations to participate in the study, only 15 agreed. This translates to 68% of the total population of Christian faith-based organizations which were included in the study. Those organizations who did not offer to participate in the study indicated that time was a constraint and that they would not be in a position to request members of their congregations to participate in the study, whilst others were indifferent towards the study.

As far as the sample is concerned, ten respondents from each of the 15 organizations were selected purposively to participate in the study. This study used the non-probability sampling technique to ensure that the desired number of respondents are represented in the study.

The 15 religious organizations that agreed to participate in the study were requested to identify ten undergraduate students (between their 1st year and 4th year of study). These respondents were selected purposively to participate in the study. With this distribution, a total number of 150 participants were identified by the respective faith-based organizations. A semi-structured self-administered questionnaire was used for the study. The nature and structure of the questionnaires were explained to the officials of the faith-based organizations as to how it should be administered. The administration of the semi-structured questionnaires lasted for a month, which was the cut-off date for its completion and to be returned to the researchers. Not all organizations were able to complete the required ten questionnaires as requested. In total, 123 completed questionnaires were returned for analysis. This constituted a response rate of 82% of the total number of respondents identified to participate in the study. The number of completed semi-structured questionnaires for each of the religious organizations ranged from five to nine respondents with a mean of seven questionnaires for each organization.

Discussion

In this study, the gender distribution of respondents was adequately represented, with 53% of the respondents being males and 47% females. A wide distribution of age ranges among respondents was noted with just more than half (54%) of the respondents falling in the age range of 16-20 years, and 38.2% in the age range of 21-25 years. When the two distributions are combined, it constitutes 92.2% of the respondents who ranged between the age group of 16-25 years. The remaining respondents (6.2% and 1.6%) fell in the age ranges of 26-30 and 31-35. This distribution is in keeping with the age definition of youths (35 years and below) in the country. In keeping with the national age trend for young people, the majority of the respondents in this study are classified as youths.

The year of study amongst respondents varied markedly. Just less than half (44.7%) of the respondents was in their first year of study, compared to respondents in the second year and third year comprising 22% and 28.5% respectively. Respondents in their fourth year of study constituted 4.8% of the sample. This distribution suggests that most of the respondents (95.2%) in the study ranged between their first and third year of study, which is in keeping with the university norm for the completion of a three-year undergraduate degree.

The extent of one's religiosity can be measured by the frequency with which one conforms to religious prescriptions, abide by religious rituals, and one's attendance at religious activities and programs. In this study, 98.4% of the respondents reported that they attend religious programs at least once a week. By virtue of church attendance, respondents reported that it provided a 'sense of belonging to their religious group' where they experienced 'a stronger sense of solidarity', where they became 'spiritually inclined', and were able 'to inspire and motivate others' , 'pray more' and finally, 'love God and respect people'. These responses suggest some of the positive outcomes derived by respondents through their participation in a religious associational life on campus.

A number of factors are shaping religiosity. The primary catalyst that inspires the respondents' religiosity was their parents. Cumulatively, 73.2% of the respondents strongly agreed that the influence of their parents had a positive impact on their present state of religiosity. Apart from parents having influenced the respondents' level of religiosity, other variables also influenced the religious beliefs of the remaining 26.8% of respondents. In this respect, friends, extended families (uncles, aunts, and grandparents), pastors, community members, high school and college attendance, and even the media (such as TV, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) had in one way or the other influenced their religious beliefs. The finding that the family, through the parents, inspired the religiosity of respondents is similar to a study at the Brigham Young University that was carried out by Dollahite and Thatcher (2005) who have found that religion was largely a family affair, linked to family satisfaction, which provides the cradle in which religious values are inculcated since childhood. They also observe that families that are devout, socialize their children in keeping with their personal belief structure.

The religious grounding provided by parents and significant others enhanced the identity of respondents, which was nurtured further through an association with on-campus religious associations. A vast majority (80.5%) of respondents reported that on-campus religious associational life reinforced their religious identity. As a consequence, they could sustain their spirituality and derive a sense of solidarity through these associations. Through their identity and the solidarity that they have experienced, they were in a stronger position to contribute to community outreach programs initiated by their respective religious associations, help, inspire, and motivate people, and influence their personal upliftment and perception of life. In addition, they reported becoming more disciplined, well-behaved to their family, friends, and community, inspired and empowered through the skills and workshops offered by the religious associations, and they became more focused on important aspects of their lives, more tolerant of other religious groups and sexual orientations (e.g. the LGBTQI community), have been able to identify more with their inner self, and have reduced their bad habits (smoking, drinking, clubbing, and engaging in sexual activities). A similar study of South African students has been conducted by Patel, Ramgoon, and Paruk (2009), who found that there was a correlation between religious life and life satisfaction. For instance, between 1999 and 2001, numerous World Values Surveys were conducted, and the findings showed that 62.1% of South Africans between the ages of 18 and 24 viewed religion as an imperative factor in their lives. 98.7% demonstrated that they trusted in God, and 69.3% revealed that God was essential in their lives (Lippman & Keith 2006:111).

Respondents also felt that a connection with their religious associations has helped them to reinforce their spiritual identities on campus. Responses such as those mentioned below, suggest that respondents have derived positive spiritual benefits, which define their identities by associating themselves with the respective religious associations on campus.

Leoane: It has given me more insight into my faith and there are weekly activities that take place that allow me to frequently be in touch with my spirituality, even at times when it is hard to do so by myself.

Clare: I pray frequently. Having religious groups on campus has helped to improve my understanding of my faith and has helped me to answer unanswered questions about my faith.

Mcebo: I study the Bible more, talk to God through prayer, and also do more teaching of the word of God which has impacted greatly on my social skills.

Moses: I now pray more and read my Bible more often and I am more at peace. It has also played a major role in growing the revelation of Jesus Christ, to pray frequently and to love the word of God.

Ayanda: Praying frequently destresses me. I usually feel calmer when I have spoken to the Lord. It feels like I have communicated to God and my heavy troubles have been decreased.

Wiseman: It has brought me closer to God and sometimes I attempt to read the Bible. Also finding this religious association has given me the tools not only on understanding the word but also applying it to my daily life.

Augustine: I pray more often than I used to, and I understand that prayer is important and has become my habit. I try to go to Bible sharing as often as I can. It helps. I have become more conscious of what I am supposed to do, and I dress modestly.

Sanele: The sense of togetherness makes it easy to practice religion and exchange religious views, etc. It creates awareness and that there are other people alike out there, therefore making the reinforcing of religious identity easier.

Thumeka: To appreciate life and the reasons we are here - knowing that God has plans for us all and to be content with existence.

From these narratives, it is obvious that religion had a positive impact on these respondents' lives. It has shaped the way in which they think and believe in their faith, provided consolation during troubled moments, provided a moral compass and direction in life, helped to form relationships with similar faith individuals and groups, engage in prayer activities, have a better understanding of their faith, pray more often, and helped them with their studies. These findings are contrary to Wuthnow (1988), Berger (1967), Feldman and Newcomb (1969), and Uecker et al. (2007) who assert that college attendance leads to the evolution from traditionalism to secularization, and that college serves as a liberalizing factor on students' behaviors and value, while their religious views become less doctrinaire and more personal, while religious tolerance amongst people of different faith groups becomes prevalent.

Fowler (1981:14) draws on what he calls 'faith development theories'. These theories propose that the youthful stage is a crucial time for young people to re-assess the belief of their adolescence based on new encounters, discuss their relationship with others, and their affiliation with groups that assist them in their journey of personal discovery. In the context of student life, students may be involved in organizations that provide safety and build on their faith. This offers ' refuge in a conventional, unexamined faith' (Parks 2000:198). These religious groups are effective in enrolling people, despite their position. This may lead to faith development, including having a larger comprehension of people, the difficulty of life, and the world at large (Parks 2000:198). This study has established a positive relationship between students' religious affiliation and active participation in diverse projects. It was observed that respondents were found to be engaged in diverse projects and programs (i.e. religious, cultural, community work, social, sporting, and academic) before and after joining the association.

Religious associational life also had a positive impact on the respondents' academic performance. Studies have also shown a relationship between achievements on college level and religiosity, although it was often difficult to resolve the direction of that relationship (Mooney 2010:200). For example, based on data from a nationwide sample of college freshmen, Alyssa Bryant (2007:11) found only a minimal correlation between religion and academic success, and concluded that in the first year of college, students who participated in religious groups succeeded academically because they arrived at college, demonstrating promising academic records. It was also found that some of the Evangelical students with a strong childhood religious conservatism had a negative impact on later educational attainment due to devoting much time to their religious commitments resulting in the fact that their study time suffered because of that (Bryant 2007:11). In this study, almost half of the respondents (47.3%) affirmed that religious associational life has a positive influence on their academic life, and felt that they found a better way to study (group study), that they were motivated through mentoring programs from colleagues within their respective religious groupings, that they worked harder and were positively driven, and that they trusted in God, while being more prayerful to achieve success. This is supported by remarks made by respondents that a religious associational life made them 'get motivated and inspire them to study more', that they 'found someone in the religious group who can share my academic burdens during exams and assignments', 'feel more comfortable and confident hoping for good results because of prayers', and 'by praising the Lord, my attitude towards academic work has changed as well as my marks', 'helped in time managing', and 'being committed in my studies in order to pass'.

Apart from being members of on-campus religious associations, respondents were also affiliated with other campus associations and groups. 48.2% of the respondents reported being members of other associations. The membership of other associations was spread along with a variety of clubs and societies which were prevalent on campus. Some of the clubs and societies that respondents identified with, are the South African Students Congress (SASCO), Black Lawyers Association, political organizations, sporting clubs, the LGBTQI society, and the Golden Key Honor International Society. When respondents were asked as to whether their membership of these clubs and societies affected their sense of religiosity and identity, 86.2% reported that there was no effect. However, they reported that, by associating with secular clubs and societies, it exposed them to many new programs that enhanced their intellect, they found an opportunity to experience other secular values, and they transferred what they learned from these groups into their own religious group. Some reported that it had a negative effect because it could change their religious orientation and make them judgmental of others, so that they did not have ample time for their religious activities.

The above findings are supported by Chickering and Reisser (1993:277) who contend that the establishment of different associations on campus encourages social assimilation among students and increases personal growth during university days. These establishments include student residences, clubs, and student associations. It is alluded to, that this process is best in creating conducive environments for friendships and to learn from one another (Chickering & Reisser 1993). Religious participation on campus forms part of social integration. This means that faith groups play an important role in forming and building friendships and close relationships with fellow members (Bryant 2007:11). This also leads to spiritual and psychological growth and serves as a support system (Bryant 2007:13). The benefit of belonging to social groups is highlighted by Parks (2000:199), who believes that a mentoring community can provide the necessary combination of support and motivation to encourage spiritual growth among its members. For instance, for youths who leave their families to join college life and embrace college challenges, spirituality will help them to grow their own strength while concurrently building their trust in their own ability to accomplish growth.

As far as respondents' perception of other faith groups on campus was concerned, most of them (85%) had a positive perception. More than half of the respondents (56.1%) were positively disposed to enter into a dialogue and share their faith with other religious groups on campus whilst more than a quarter of the respondents (26.8%) were undecided, and the remaining 17% provided no response. In addition, more than half of the respondents (57%) welcomed the idea of having multi-faith programs on campus. They felt that it would help to foster peace, help with a better understanding of other faith groups, and unite different race groups. Since South Africa subscribes to being a rainbow nation, exposure to different cultures reduces discrimination and allows for greater tolerance amongst different religious groups on campus. This is in keeping with the earlier assertion made by Emile Durkheim (1965:62), who views religion as benefitting social integration through a unified system of beliefs and practices that set things apart and forbid transgression of long held religious beliefs in forming one single moral community.

However, the remaining 43% reported that hosting multi-faith programs on campus could lead to conflict and confusion among faith groups, resulting in a lack of understanding and a poor response from students. This is attributed to some students who, by virtue of being deeply devoted to their faith, might want to stay clear of influences from such programs which might conflict with their faith. Such a response suggests the devoutness of respondents to adhere to their religious upbringing and not to deviate from it. Those that support multi-faith programs (57%), suggest that they are open to entering into a discourse with other faith groups while at the same time adhere to their own religious identity. This finding is somewhat similar to the study cited by Hodges (1999) at the University of Minnesota which found that students have an interest in active multi-faith programs that promote a diversity of religious practices. This, to a large extent, contributes to religious tolerance.

Moreover, at the same time, 69.1% of the respondents have indicated that they have friends that belong to different faith groups, while 30.9% reported that they have no friends originating from a different faith group. As far as being comfortable in the company of other faith groups, 78.9% of the respondents felt comfortable engaging with other students from other faith groups, as their respective religious associations did not pressure them not to engage with other religious groups. Hence, there was freedom of choice as to which religious group one would like to interact with. A significant number of respondents (20.3%) felt uncomfortable interacting with students of different faith groups as they felt that they might offend them and be rejected, as other religious groups might express their religious belief as being superior to others. In addition, they felt that an encounter with other faith groups may result in a lack of understanding of their religious values, ideology, and interpretation of their religious texts and the message that emanates from them.

As far as the prevalence of religious tolerance on campus was concerned, interestingly a third of the respondents (33.3%) felt that there was an intolerance among the different faith groups which could be as a result of differences in religious beliefs, ideologies, and practices. Some students shy away from students of other faiths and tend to identify and socialize with students who share similar religious doctrines in order to avoid conflict and maintain peace. The remaining two-thirds (66.7%) felt that religious beliefs were not imposed on students, which suggests a positive attitude towards religious tolerance on campus. Those respondents that felt that there was no religious tolerance on campus, argued that it originated largely from individual prejudices about other students' faith. Some respondents referred to the nature of religious intolerance on campus, especially those of the Islamic faith and those who subscribed to polytheistic beliefs. It was observed that Muslim students were scorned for their religious code of dress (most especially females) and those students that subscribed to polytheistic beliefs were looked down upon. This attitude is also underscored by racism as most Indian students are of the Islamic and Hindu faith groups while most black Africans are Christians. More so, some religious associations among the Christian faith group discriminate among themselves on the belief that their faith was superior compared to others.

Religious conflict can also lead to alienation from faith groups. However, in this study, only a minority of the respondents (16.3%) felt alienated. They reported a lack of movement among religious associations, a lack of religious expression that was prevalent on campus, the absence of a warm reception from other religious groups, and their inability to form friendships among students of other faith groups. One of the major reasons cited for alienation was the fundamental difference in religious beliefs, which made them believe that their religious traditions and practices were superior to others. Finally, respondents suggested ways in which some social ills in society can be reduced by prioritizing peace and unity among all races, cultures, and genders through religious dialogue. It was felt that South Africa as a democratic nation should practice what it preaches by educating and empowering the youth to be future leaders through an engagement in the activities of religious associations which will fight, among others, social injustice, immorality, disunity, and violence in the country.

Strength and Limitation of the Study

The limitations of this study are worth addressing. The study lacks local literature on the religious life of university students, both in South Africa and in the African continent. Most studies on religion and youth originate from developed countries. Nevertheless, the literature reviewed in this study can serve as a baseline to compare how the religious associational life impacts youth lives on campus and elsewhere in the world. In the South African context, this study provides a basis for replication at other institutions to observe how a religious associational life impacts on youth campus life. Additionally, it will be interesting to undertake a comparative study of religious and irreligious students and its impact on various aspects of their campus life.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the religious associational life of students on campus. The nature of such association, its impact on sustaining their religious identity, and ways in which it shapes their lives whilst at university, was explored. It highlights how the religious associational life on campus reinforces their religious identity, which is transferred from secondary school. An important dimension of the study is the illustration that the secular nature of campus life had little or no impact on the religiosity of the research participants. In fact, the continuity of their religious beliefs from school to university has been reinforced through a participation in religious associations on campus. It illustrates that students in this study have displayed an overwhelming sense of religiosity as compared to elsewhere in the developed world such as the USA, UK, and New Zealand. Since South Africa is a developing country, this trend is not indifferent.

The rationale behind students joining religious associations is highlighted in the study. A variety of factors such as deriving a sense of belonging, sustaining their religious identity, and spiritual growth are key for respondents who join on-campus religious associations. This rationale has been overwhelmingly supported by respondents in terms of benefits derived from a religious associational life on campus. Such a finding is not confined to the religious associational life on campus but is also extended off campus.

In terms of the agency that has been influential in shaping the religiosity and identity of respondents, the family was the key socialization unit that influenced the students' religious beliefs. However, their religious identity was intra-directed as they maintained contact with individuals with the same faith. Despite this trend, there is a strong indication that they were tolerant of other faith groups. Studies by Hodges (1999), Hurtado and Carder (1997), as well as Kuh and Gonyea (2005) found that students have an interest in active multi-faith programs that promote a diversity of religious practices, whereas religious associations provide them with a sense of community. Students also like to engage in religious and spiritual programs and are more likely to be members of other clubs and societies, participate in community outreaches, as well as cultural and social events. This suggests that a religious associational life positively influences and shapes students' life experiences.

Despite being intra-directed with respect to their faith, the respondents found that an association with other campus groups have enhanced their worldview about people in general and helped them to develop positive attitudes towards themselves. This was because of their participation in projects and programs outside their religious grouping, which was common to the students on campus. The effects of engaging with other programs and projects within the student body helped them to develop a certain amount of solidarity, inspiration, and motivation to aspire academically through an on-campus religious associational life. There is evidence that a regular attendance to mosques, churches, synagogues, and other religious activities increases college satisfaction and college marks. It offers them guidance and organization, having a positive influence on their performance. Through religious associations, it provides them with a support system and creates orderliness in their lives which is conducive to academic achievement (Mooney 2010). In addition, a religious associational life helps students to overcome certain anti-social and socially unacceptable behavior whilst on campus.

From the findings of the study, it is recommended that on-campus religious associations should undertake university-wide awareness programs with regards to a risky lifestyle with too much alcohol, smoking, and substance abuse. There should be an educational and personal development, as well as career and life coaching support programs for students who are not self-motivated or lack family support with respect to their studies. Religious associations should motivate their members to be politically involved, both on and off campus, since they are the future generation. They should therefore be active advocates for those who experience poverty, inequality, and oppression. It is quite important to create multi-faith platforms in order to understand different religions without any prejudice or judgment that arise from the lack of knowledge about the other. In light of this, common programs and activities within and outside faith groups can have a positive impact on religious encounters in different forms. It can foster religious tolerance and promote unity and peaceful co-existence. However, these programs and activities need not be restricted to the on-campus student community but should also extend to communities from which students originate. Religious associations on campus should join similar associations by inviting scholars and experts of repute to discuss matters on religious diversity and co-existence with the wider student community. In this way, they would be enlightened about the social issues challenging different faith groups in the country, the continent, and the globe at large.

Broadly speaking, research on religion and youth development has not been investigated in the country. Hence, it is imperative that future research on the religious identity of students include other minority faith groups like Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism to spread throughout other campuses where a similar study can be replicated to ascertain whether a correlation exists in terms of their nature or any religious differences that may exist. The effect that religion has on youth development related issues in the country can assist in finding solutions to the various socio-economic dilemmas being experienced. Considering that the youth are marginalized in various ways in the country, and exposed to anti-social behavior, the study can provide an insight on how religion can play an effective role in shaping their behavior. More so, considering that the 21st century is characterized by religious intolerance (Brander 2012) and a lack of peaceful co-existence on the globe, attempts need to be made to engage students in a way that they can co-exist as a student community and carry this over to their future adult life.

References

Astin, A.W., H.S. Astin, & J.A. Lindholm 2011. Assessing students' spiritual and religious qualities. Journal of College Student Development 52, 1: 39-61. [ Links ]

Berger, P.L. 1967. A sociological view of the secularization of theology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 6, 1: 3-16. [ Links ]

Brander, P. 2012. Compass: Manual for human rights education with young people. Council of Europe. Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass. (Accessed on November 25, 2018. [ Links ])

Bryant, A.N. 2005. Evangelicals on campus: An exploration of culture, faith, and college life. Religion and Education 32, 2: 1-30. [ Links ]

Bryant, A.N. 2007. The effects of involvement in campus religious communities on college student adjustment and development. Journal of College and Character 8, 3: 1-25. [ Links ]

Chickering, A.W. & L. Reisser 1993. Education and identity. The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Clark, D., S. Tse, M. Abbott, S. Townsend, P. Kingi, & W. Manaia 2006. Religion, spirituality and associations with problem gambling. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 35, 2: 77-83. [ Links ]

Diener, E., L. Tay, & D.G. Myers 2011. The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101, 6: 1278-1290. [ Links ]

Dollahite, D.C. & J.Y. Thatcher 2005. How family religious involvement benefits adults, youth, and children and strengthens families. Draft Paper. Brigham Young University, Provo. [ Links ]

Donahue, M.J. & P.L. Benson 1995. Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues 51, 2: 145-161. [ Links ]

Durkheim, E. 1965. The elementary forms of the religious life 1912. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Feldman, A.K. & T. Newcomb 1969. The impact of college on students. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Fowler, J.W. 1981. Stages of faith: The psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. San Francisco: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Galen, L.W. & W.M. Rogers 2004. Religiosity, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and their interaction in the prediction of drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 65, 4: 469-476. [ Links ]

George, L.K., C.G. Ellison, & D.B. Larson 2002. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry 13, 3: 190200. [ Links ]

Gibson, T. 2008. Religion and civic engagement among America's youth. The Social Science Journal 45, 3: 504-514. [ Links ]

Glass, J. & J. Jacobs 2005. Childhood religious conservatism and adult attainment among black and white women. Social Forces 84, 1: 555-579. [ Links ]

Gunnoe, M.L. & K.A. Moore 2002. Predictors of religiosity among youth aged 1722: A longitudinal study of the national survey of children. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41, 4: 613-622. [ Links ]

Hodges, S. 1999. Making room for religious diversity on campus: The spiritual pathways series at the University of Minnesota-Morris. About Campus 4, 1: 25-27. [ Links ]

Hurtado, S. & D.F. Carter 1997. Effects of college transition and perceptions of the campus racial climate on Latino College students' sense of belonging. Sociology of Education 70, 4: 324-345. [ Links ]

Jessor, R., J. Van den Bos, J. Vanderryn, F.M. Costa, & M.S. Turbin 1995. Protective factors in adolescent problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology 31, 6: 923-933. [ Links ]

Jeynes, W.H. 2003. The effects of black and hispanic 12th graders living in intact families and being religious on their academic achievement. Urban Education 38, 1: 35-57. [ Links ]

Kuh, G.D. & R.M. Gonyea 2006. Spirituality, liberal learning, and college student engagement. Liberal Education 92, 1: 40-47. [ Links ]

Lippman, L.H., & J.D. Keith 2006. The demographics of spirituality among youth: International perspectives. In Roehlkepartain, E.C., P.E. King, L. Wagener, & P.L. Benson (eds.): The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Love, P. & D. Talbot 2000. Defining spiritual development: A missing consideration for student affairs. NASPA Journal 37, 1: 361-375. [ Links ]

Marsden, G. 1994. The soul of the American university. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

McBride, D.C., P.B. Mutch, & D.D. Chitwood 1996. Religious belief and the initiation and prevention of drug use among youth. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Miller, A.S. & R. Stark 2002. Gender and religiousness: Can socialization explanations be saved? American Journal of Sociology 107, 6: 1399-1423. [ Links ]

Mooney, M. 2010. Religion, college grades, and satisfaction among students at elite colleges and universities. Sociology of Religion 71, 2: 197-215. [ Links ]

Moos, R. & E. Lee 1979. Comparing residence hall and independent living settings. Research in Higher Education 11, 3: 207-221. [ Links ]

Odimegwu, C. 2005. Influence of religion on adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviour among Nigerian university students: Affiliation or commitment? African Journal of Reproductive Health 9, 2: 125-140. [ Links ]

Park, C.L. 2005. Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of social issues, 61, 4: 707-729. [ Links ]

Park, C.L. 2007. Religiousness/Spirituality and health: A meaning systems perspective. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 30, 4: 319-328. [ Links ]

Parks, S.D. 2000. Big questions, worthy dreams: Mentoring young adults in their search for meaning, purpose, and faith. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Pascarella, E.T. & P.T. Terenzini 1991. How college affects students. Vol. 3: 21st century evidence that higher education works. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Pascarella, E.T. & P.T. Terenzini 2005. How college affects students. Vol. 2: A third decade of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Patel, C.J., S. Ramgoon, & Z. Paruk 2009. Exploring religion, race and gender as factors in the life satisfaction and religiosity of young South African adults. South African Journal of Psychology 39, 266-274. [ Links ]

Regnerus, M., C. Smith, & M. Fritsch 2003. Religion in the lives of American adolescents: A review of the literature. A research report of the National Study of Youth and Religion, No. 3. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. [ Links ]

Sherkat, D.E. 2007. Religion and higher education: The good, the bad, and the ugly. SQL Server Reporting Services (SSRS). Available at: http://religion.ssrc.org/reforum/Sherkat.pdf. (Accessed on November 30, 2018. [ Links ])

Statistics South Africa 2014. General household survey. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

Uecker, J.E., M.D. Regnerus, & M.L. Vaaler 2007. Losing my religion: The social sources of religious decline in early adulthood. Social Forces 85, 4: 1667-1692. [ Links ]

Wuthnow, R. 1988. The restructuring of American religion: Society and faith since World War II. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

1 Ethical clearance number: HSS/0952/016M - University of KwaZulu-Natal.