Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.32 n.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2019/v32n2a1

ARTICLES

Unpacking the Socio-Political Background of the Evolution of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria: A Social Movement Theory Approach1

Dr Kingsley Ekene AmaechiI; Dr Rendani TshifhumuloII

ICentre for African studies School of Human and Social Sciences University of Venda. Kingsley101Amaechi@gmail.com

IICentre for African studies School of Human and Social Sciences University of Venda. Rendani.tshifhumulo2@univen.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In the last decade, Boko Haram (BH) has become notorious across the world, because of its militancy and ultra-fundamentalist activities. Its violent activities have in many ways surpassed other similar African Salafi-oriented organizations, such as the AQIM in Algeria and al-Shabaab in Somalia. This article traces the socio-political and organizational background upon which this organization evolved in Northern Nigeria. Drawing from the social movement theory, it harnesses data, collected mostly from semi-structured interviews on some Salafi leaders, security personnel, politicians, and ordinary civilians who worked in the area. The study explains how the evolution of such an organization is rooted in context-specific political structures within Northern Nigeria. The argument is that these are enabling mobilization resources and political opportunities upon which initial BH activists established the organization in the region.

Keywords: Armed violence, Boko Haram, Northern Nigeria, Salafi-oriented movement organizations, Salafism, Social movement theory

Introduction

The last few decades have seen the rise of Salafist-oriented Movement Organizations (SOMO)3 (Teplesky 2016) and an increasing adoption and use of armed violence tactics by such organizations in the sub-Saharan Africa (Solomon 2015). Often arising as minor regional-based groups (Amaechi 2017), SOMOs4 have capitalized on social discontent, economic failures, and dissatisfaction with corrupt governments, to mobilize a mass insurgency against the existing state governments (Burke 2018). From their point of view, this collective activism would eventually lead to the acquiescence of the political/religious demands by their host societies (Amaechi 2017).

To be fair, this kind of activism is not unique to SOMOs within sub-Saharan Africa. SOMOs from other parts of the world (particularly in Asia) have all evolved and used such advocacy as a means for the attainment of their goals (Juergensmeyer 2003; Wiktorowicz 2004). In fact, before the 1990s, there was not much armed violence activism in sub-Saharan Africa. Most SOMOs who use violent activism are from other parts of the world, particularly from Asia (Teplesky 2016). It was not until after the 1990s that SOMOs, with a more explicit commitment to armed violence, began to evolve in sub-Saharan Africa (Hentz & Solomon 2017). Organizations with no religious affiliations have also arisen in other contexts (Franks 2006; Juergensmeyer 2003). In the face of what has been considered as a 'conducive environment' for armed activism (Amaechi 2019:4), such sociopolitical sensitive organizations (that adopt armed violence activism) have evolved (Amaechi 2019; Franks 2006; Wiktorowicz 2004; 2006; Gunning 2009). Drawing on the mobilization opportunities that such political structures generate within their environment, socio-political sensitive activists have established these organizations and have used them to achieve certain construed socio-political goals (Juergensmeyer 2003).

In this article, we expand this argument, focusing specifically on a SOMO popularly known as Boko Haram, which first evolved in Northern Nigeria (Amaechi 2017). Borrowing ideas from a political opportunity process and resource mobilization models within the social movement theory, we argue that such organizations do not evolve from a vacuum; they rather evolve as a result of the interaction of different socio-political conditions around these groups and the environment in which they identify themselves. Such conditions, identified as the Northern Nigerian culture of Islamic activism, the Nigerian colonial legacy, al-Shari 'a advocacy, the intra-ideological dispute between Yusuf and the main Salafi networks in Northern Nigeria (Jama'at Izalat al Bid'a Wa Iqamat as Sunna and Ahlus Sunna), as well as the group's initial leaders' cooperation with al-Qaeda networks, often regarded as ' political opportunity structures' within the social movement theory literature (Gunning 2009; Wiktorowicz 2004), provide the sociopolitical and organizational background upon which it was possible for BH's initial leaders to establish the organization in the North-eastern parts of Nigeria.

Some previous studies have also identified similar opportunity structures as the main conditions propitious for the evolution of BH (Alao 2013; Anonymous 2012; Brigaglia 2015; Kassim 2018; Loimeier 2012; Onuoha 2015). Brigaglia (2015) particularly explains how the intra-ideologi-cal disputes between two main Salafi networks in the region (Jama'at Izalat al Bid'a Wa Iqamat as Sunna - also known as Yan Izala - and Ahlus Sunna) on the one hand, and the persistent poor economic situation following the region's adoption of Sharia law in the early 2000s on the other hand, had provided the most important incentive for the motivation and justification of the establishment of BH in the region. The disenchantment with the Sharia implementation, he argues, among other things, created the conditions for the hybridization and subsequent evolution of the group. The organization as propagated by Yusuf Mohammad resonated with a sector of young Muslims (almost in an unconscious way), mainly because it had a renewed promise to address the young Salafis' quest for socio-political and cultural change in the region.

The forthcoming analyses on the evolution of BH will draw on these kinds of analyses. However, more than identifying one or two of these conditions, it will also draw from the idea of political opportunity within the social movement theory, to explain how these conditions are inter-connected to the availability of financial resources from the late al-Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, in the evolution of the organization. Within the political opportunity model, such conditions, conceptualized as propitious for the evolution of these organizations, are treated as fluid and responsive (Amaechi 2017; Gunning 2009). The emphasis is not on any particular condition, but rather on the interactions between the conditions - how they influence each other to impact the individual's and group's appeal for subscription and devotion to an organization such as BH. Our argument is that even though the disposition to establish a religio-political activist group may exist due to several reasons, such disposition do not necessarily translate to the actual establishment of such an organization without corresponding access to resources. Thus, the evolution of the organization is not necessarily a result of a cultural or cosmological imperative that emanated from the Salafi-jihadism or the region' s mere economic conditions, but the product of socio-political debates among the movement activists and functional power struggles that were motivated and encouraged by different levels of access to resources and competing interactions of the activists' interests and identities within the region.

Data and Method

The study mostly relied on semi-structured and focus group interviews of individuals with an in-depth knowledge of the socio-political contexts from which BH evolved. These individuals include

• security personnel working within the area (members of the recently formed Multi-National Joint Task Force [MNJTF], members of the Nigerian Joint Task Force, and ordinary policemen and women working in the area);

• politicians, particularly those within the three main North-eastern states of Nigeria;

• religious clerics from the Izala and Ahlus Sunna; and

• victims of BH violence.

These interviews were conducted between January and May 2016.

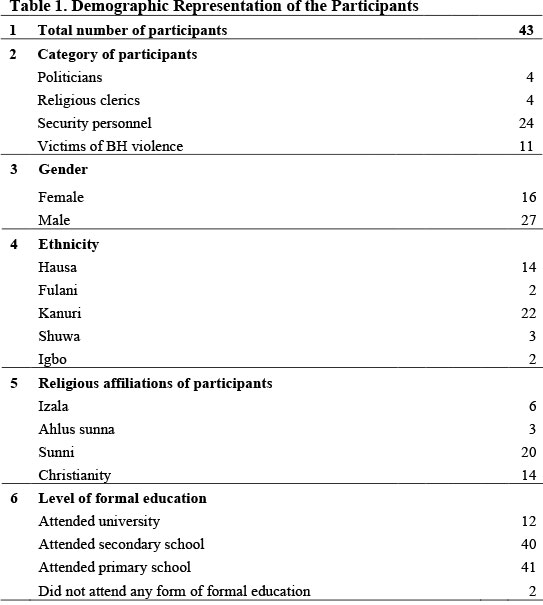

Initially, the data included information from self-proclaimed active or former members of BH who were (as of 2015) incarcerated in different Nigerian prisons as possible participants for the study. The idea was that these individuals would give the study access to unique primary data about the emergence of the group in Northern Nigeria. Our understanding was that none of the previous researchers (as of 2016) have been able to interview such activists or got information from their point of view (Amaechi 2019). However, when permission and access to these participants were not obtained due to security concerns and the sensitivity of the study5, a decision was made to limit the participants to the above listed individuals. Below is a demographic representation of these participants.

Thus, a total of 43 individuals were interviewed. Although these participants were not members of BH, they all had personal contacts with the group. They therefore had significant information about the origin of the group. They could also empirically relate how different conditions influenced the evolution of BH within the region. The participants' personal experiences with the members of the group gave them a meaningful understanding of how the organization operated in the region. Such insights were needed to make a meaningful construction of the evolution of BH in the region.

In addition to these interviews, the study also used secondary sources such as recently released letters between BH and the AQIM leaders6 about the internal functions of BH. These sources contain data which was uses to contextualize the importance of resources and different socio-political conditions in the evolution of the organization in Northern Nigeria.

In analyzing the data, a thematic analytic approach (built on the grounded theory), first developed by Braun and Clarke (2006)7, was adopted. Rather than their six-step model, a modified four-step model was used, namely:

• familiarization with the data and generation of initial codes;

• organization of codes into themes;

• review of themes; and

• write-up.

However, the sequence of these steps was not considered. In most cases, there was a movement back and forth between the steps in an iterative and recursive way. What was important was to identify, analyze, and interpret the data in ways that depict a true representation of the dataset.

Using the Analytic Approach, the study was able to identify significant themes (as conditions) that emerged in the development of the organization. Through repeated coding and an arrangement of these conditions as codes (using the Microsoft Excel program), it was possible to make sense of how the different identified conditions interacted and were interrelated with each other. This method was consistently followed throughout the analysis in both the interviews and the secondary data.

Political Opportunity Structures that Influenced the Evolution of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria

In investigating the evolution of the organization, the study identified five conditions as the most important 'political opportunity structures' that influenced the evolution of BH:

• The Northern Nigerian culture of Islamic activism.

• The Nigerian colonial legacy.

• Al-Shari 'a advocacy at the dawn of the democracy in 1999.

• The fallout from the al-Shari 'a advocacy vis-a-vis an intra-ideologi-cal dispute between Yusuf and the main Salafi networks in Northern Nigeria.

• Cooperation with al-Qaeda.

Below is a descriptive analysis of how these conditions provided the sociopolitical background upon which an oppositional SOMO such as BH emerged in Northern Nigeria.

The Northern Nigerian Culture of Islamic Activism

The dataset shows that the use of armed violence as a means for goal attainment in Northern Nigeria did not start with BH. In fact, the second phase8 of Islamic tradition itself in the region was founded on armed violence activism, when a famous Fulani9 preacher, Usman dan Fodio, propagated what is still regarded in the region as a 'great jihad against infidels' (Comolli 2015; Smith 2015). Built on the removal of the original Habe leaderships of the Hausa states10, this 'jihad' established Islam - through violence - as the dominant religious tradition across communities in Northern Nigeria (Comolli 2015: 15). Through this jihad, the respected religious cleric brought all the Hausa communities together as a united Islamic-based Sokoto Caliphate, based on the Islamic theocratic al-Shari'a system. He became the first Sultan of the Caliphate. The Caliphate did not only grow in the present-day Northern Nigeria, but in other areas as well, like parts of Cameroon, the Niger Republic, and Chad.

One of the major factors that attributed to dan Fodio's success, was his ability to use Islam to frame his socio-political activism against the Hausa kings (Comolli 2015; Smith 2015). The argument is that dan Fodio had capitalized on the growing resentment among the population to mobilize and obtain legitimation for his religio-political activism (Haron 2016). Drawing on Islam's religio-political history, the cleric was able to frame the opposition against the despotic Hausa kings as a sort of a 'jihad', within which participation was a kind of moral and religious duty incumbent on all Muslims within the newly founded Islamic community (Comoli 2015). Within dan Fodio' s conceptualization of socio-religious activism, the Hausa rulers were simply regarded as apostates who had moved away from the principles of Islam in terms of their beliefs and practices. Hence, they were considered as legitimate targets. Amidst shared frustrations and resentment, this framing proved effective and would result in a wide range of support among many Muslims within both the Fulani nomadic communities and beyond (Haron 2016).

However, one main effect of these actions in the region is the 'concretization' of Islam's role as a mobilization resource upon which the opposition's political activism was galvanized. Dan Fodio subtly introduced framing activism around Islam as a tool to mobilize forms of political activism against the state. His use of Islamic religious texts as a tool to justify socio-political activism against the despotic Hausa kings, subtly legitimized a violent contention and activism against state authorities. Thus, a formation of a sound organization built upon Islamic theological concepts consequently became an important way to engage with the state.

The fact that the religious tradition itself has a similar jihadi history, further exacerbates this phenomenon. The understanding of politics along religious lines is nothing new within the Islamic tradition. Prophet Muhammad himself, the founder of the religion, was both a political and religious leader during his lifetime (Gilles 2002). Following the opposition at Mecca, the Prophet migrated (it was called hijra) to Medina around July 622. There he became the political head of the Umma community and created a system that did not only combine religious and political power in one entity, but also the first Islamic community (umma) under an Islamic constitution - the Sharia law (Gilles 2002). Members of this community were bound to demonstrate their religious commitment through waging a religious/political 'jihad' (Falola 1998). Using this kind of framing, the Prophet and his immediate successors were able to establish Islam in both Mecca and beyond. Dan Fodio's jihad and establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate replicates Muhammad's 'religio-political' activism. By relocating to Gudu (a replication of the Prophet's hijra) and evoking the similar religious framing for his socio-political activism in the region, this religious leader, respected by the Fulani, was able to indirectly bequeath a religious quality to what could now be termed a 'socio-political affair'. This not only helped in popularizing his activism, but also explains why political activities in this region are often seen and cast in religious terms.

A discussion with several respondents corroborates this notion. In fact, most of the respondents, particularly the religious scholars and politicians representing some of the constituencies in the region, argue that Islam gave political armed violence activism its meaning in the region. This is how one of the politicians, representing one of the North-eastern states in the region, puts it:

Islam teaches people to stand up for their rights...From our fathers we have learnt to stand up for what we believe in, with our religion as our guiding principle. Without religion, people would not see the need to speak up against the evils of the state politicians. This is our history.

Another politician who claims to be a descendant of dan Fodio (but not necessarily a supporter of BH) gives a similar argument:

For US, our great grandfather (referring to Usman dan Fodio) had shown us the way. Our people follow his footsteps, to defend our faith and our communities. They hold him in awe and try to emulate how he had followed the faith...We take our religion to be at the center of everything we do. We defend it with passion and without shame ...with our blood, our soul, and everything we have. Even if this is interpreted as violence, we don't care.

From a Salafi perspective, an Ahlus Sunna representative similarly argues:

How can you remove religion from politics? [he rhetorically asks]. Islam helps us to articulate our thoughts, actions, and political positions...Following the teachings of the Holy Qur'an, the Hadith, and the consensus of the approved scholarship, every Muslim would be able to live an authentic Islamic lifestyle, like it was ...during the memorable days of the Sokoto Caliphate. Why would we not follow in these footsteps, preach as they did, do what they did, and change our societies as they did? This will always be our mission. It is the beauty of our religion. I don't subscribe to that Western nonsense of separating politics from religion. These two things are inseparable. We need our religion to guide our every action. I am sure you get it.

Even though this logic may not quite apply in other contexts, it is clear that the political inclusion is an integral part of Islam - as a complete system, making the religion susceptible to a religio-political mobilization. This is particularly applicable in the region where such activism had obviously been concretized by dan Fodio's jihad. Since the fusion of Islam with sociopolitical activism has been concretized, the religion was easily seen as a tool to mobilize people around a socio-political agenda, especially against the state. In this case, it becomes a viable force to unite activists around a collective social or political system, against what could be perceived as a marginalization from the state.

The Northern Nigerian Colonial Legacy (1900-1960)

The European colonial legacy is also connected to the region's culture of Islamic activism. The interviews revealed that the arrival of the British and the subsequent colonization11 of the region in the late-19th century, changed the social and political landscape of the region. Initially, the colonialists' relationships with people in the region were mostly trade-related, revolving around the expansion of the Royal Niger Company12 which controlled trade and British interests in Southern Nigeria. The British were not much of a direct threat to the political structures of the Sokoto Caliphate; however, the British amalgamation of the region with the rest of the British protectorate in the south brought about sweeping changes that inevitably changed the region's socio-political landscape.

The first change was on the socio-political level, where the region's al-Shari'a Sokoto Caliphate system had to be substituted by a Western-oriented colonial system. This, inter alia, meant the introduction of a new political system and a new social value system - both incompatible with the Sokoto Caliphate. At the dawn of colonialism, the British had inherited (what I call) a distinctively conservative and close community. Different from the reality in the Southern part of the country (where diverse ethnic autonomous communities lived side by side), the British found a region that was remarkably separated from the liberal influences that existed outside the region, particularly in Southern Nigeria and in the Western world (Comolli 2015:14). Arguably, few signs of 'modernity' or the Western lifestyle existed, as the region had more relations with people from the Arab world than people from other parts of the country. Such people were generally despised and were considered as mostly belonging to another world (Comolli 2015:14). This was a very big problem for the British13.

Another significant change came in the education system. Before the arrival of the British, the most popular form of education in the region was the traditional Islamic education, known as the Tsangaya school system14.

This system of education was mostly influenced by contacts with the Arab world. It dated back to the 13th century, when Islam first arrived in the region. The system basically entailed an intensive study of the Qur'an, whereby a teacher (al-aramma) pitches a camp, often in a place at the outskirts of a town, and invites students (almajirai). Up until the arrival of the British, this system was clearly the preferred form of education for the majority of people within the region. In fact, when Lugard took over as the governor of Northern Nigeria in 1914, he found over 25,000 of these Qur'anic schools, with a total enrolment of 218,618 pupils (Fafunwa 1991:207). However, when he realized how culturally and socially challenging allowing such a system was for the new united country, as well as its incompatibility with the Western values in the colonial system, he worked towards devaluing its relevance. His administration stopped funding the Qur'anic schools. He also introduced Western colonial education in the region, not only to align the region with its Southern counterpart, but also to make it less challenging for administrative purposes.

This practically devalued the traditional Islamic system in the region. It also seriously challenged the hegemonic position of the Islamic authorities in the region and soon created the opportunity for resentment towards the colonial state. In more practical terms, certification from the newly established colonial schools became a prerequisite for getting any assistance from the colonial government. To get anything from the colonial state, including employment (civil services), people were expected to attain a certain level of scholarship, or certificates (degrees) from these newly established colonial schools. Both students and teachers who studied or taught in the traditional Islamic schools were either disregarded (seen as 'illiterates') or forced to change to the new system. This had a serious effect on the activism in the region.

It is not surprising that respondents noted that people in the region construed the effects of these changes as the cause of a deep-seated resentment against the colonial state. Due to Lugard's decision to stop funding the Qur'anic schools, some of the respondents argued that his actions were purely discriminatory and simply unforgivable. In their estimations, the colonial state's lack of funding the traditional Qur'anic schools left the schools completely on their own (Salisu & Abdullahi 2013). As the schools relied on the minimal support of parents, the teachers started to send their pupils to beg for food and money. This further tarnished the image of the schools and undermined the integrity of the teachers as well as their pupils until today.

Other respondents, who did not fully interpret the effects of colonialism, restricted their thoughts on the effects that the substitution of the Qur'anic system by the Western style education had on the subsequent mobilization of the political activism against the colonial government. One of the most eloquent respondents, who claims to have conducted research himself on the 'negative impact of colonialism on the region's traditional Qur'anic system of education', argues that 'this [referring to colonialism] was the most single element that made our people begin to revolt against the colonial state'. He continues: 'The British, by trying to force us to change our system, made a mockery of our traditional values...and sometimes, when you make people feel that their traditions are valueless, they are forced to prove you wrong' .

These kinds of sentiments are reminiscent of Alao's observation in his analyses of the role of colonialism in the 'Islamic radicalisation' in Northern Nigeria (Alao 2013). In his study, this British-based Nigerian scholar explained that many Muslims in the region were frustrated by the way in which the colonial government devalued the traditional Islamic schools. According to him, the lack of recognition for the traditional schools by the colonial government was so bad that the Muslim population was practically forced to attend ' Christian schools', where they were almost forcefully converted to Christianity. Suleiman Baba Ali, a former commissioner of health from one of the states in the region, recounted how he 'felt that there were conscious attempts by the educators of the colonial government to subtly convert Muslims to Christianity'. This, in Alao's assumption, felt like a promotion of Christianity and as a result, caused a lot of frustration and backlash in the region. Under these circumstances, most Muslims felt that this was an attack on their religion, leading to a resistant religious response.

The religious neutrality (secular) that guided the colonial state at the executive level of the colonial government did not contribute to the situation. Even though the colonial government made some effort to accommodate the political structures of the Sokoto Caliphate15, a bureaucratic system operated at the center of the government, that de-emphasized their religion and tried to replicate the Western modern state. In separating the state from religion, it pioneered the establishment of different arms of the government (the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary), as well as a vibrant civil society and secular civil service system. Within these systems, Christian holidays (such as Easter and Christmas), rather than Islamic holidays, were used as public holidays. Saturdays and Sundays which, in the Sokoto Caliphate, were nothing more than ordinary days of the week, were regarded as weekends and weekly work holidays. This was a completely different framework from the Sokoto Caliphate. While people grudgingly went along with it, they quickly translated it as 'foreign and dangerous' for the region's Islamic identity. One of the respondents argued:

How do you justify the fact that our people have to follow the colonial system which was Christianity-inspired? The Gregorian calendar which was introduced by the colonial government is completely a Christian thing, not Muslim. The Muslim calendar was ignored as if it did not even exist. They preserve Saturdays and Sundays as holidays rather than Thursdays and Fridays, which we used to have from our learning days (Tsangaya Qur'anic school). Is Sundays more holy than Fridays, which is [sic.] the Muslim days of worship? The colonial system in a way forced us to follow their ways which are inspired by Judeo/Christian religion, rather than our own Islamic ways. We are still suffering because of these things.

Although these sentiments may not have been articulated in such a manner in those days, it is easy to see why they could create a conducive avenue for resentment against the colonial state in the region. After rendering the previously acquired certification from the Islamic schools as useless in the public sphere and devaluing the people's traditional values, colonialism created an opportunity for resistance against the colonial state, either in the form of individual resentment or collective resistance. In the context where Islam, through its history in the region, had been established as the most potent weapon to galvanize activism against the state, it became an easy tool to mobilize people for socio-political activism. This is probably the reason why many Islamic resistance groups that evolved in the region against both the colonial state and the post-colonial state after independence (Comolli 2015), were framed along Islamic terms. The evolution of these groups and the little success they achieved could further cement the political role of Islam, both as an instrument for mobilization and the evolution of a resistant oppositional organization.

Al-Shari'a Advocacy in Democratic Nigeria (1999)

The concretization and the use of Islam as a potent tool for socio-political mobilization became more evident in the al-Shari 'a16advocacy that ensued in Nigeria at the dawn of the country's fourth Republic (1999). Al-Shari 'a had always been a major issue in the region since independence. However, the advocacy took a more vibrant and urgent tune after 1999. This was largely due to two reasons: First, the opening of political opportunities that came with the dawn of democracy. Democracy came with the perception of the freedom of expression and opening-up of political opportunities for advocacy. Within such contexts, activists in the region felt empowered and energized to take their activism to the heart of the Nigerian political arena without fear of political intervention from the state17. Thus, without much political intervention, they were also able to rekindle their al-Shari'a campaigns, giving TV and radio interviews, and making audio tapes as a way of mobilizing other activists for support in the region.

The second factor that accelerated al-Shari' a activism in the region at the time was the perception of 'political marginalization' that was ensued after the electoral victory of Olusegun Matthew Obasanjo (a Christian Southerner and former military head of state) and his subsequent emergence as the Nigerian President. The interpretation of Obasanjo's emergence as political marginalization in the region was largely because of Nigeria's ethnic and religious identity politics. One major effect of colonialism in the Nigerian politics was the propagation of regional and ethno-religious identity, as a marker of identity in Nigerian politics. The ' divide and rule' colonial policies had incubated a sharp political status quo, which made religion, regional division, and ethnicity the pre-eminent markers of identity and political agitation in the country, especially at federal government level where the utmost power lies. The situation was further exacerbated by the civil war, which was fought along regional and religious lines.

Fighting along these different ethnic and religious fronts in the Nigerian federal government, identity politics became entrenched in the social and political consciousness of the people. Loyalties to regional ethnicity and religious affiliations often superseded that of the state. Hence, a lack of representation of one ethnic/regional or religious group at the federal government level became easily interpreted as political marginalization, and as such created negative grievances and opportunities for political activism to represent it at the center. This was the case with Obasanjo's electoral victory. Given that he was both a Christian and a Southerner, his victory was almost automatically interpreted as political marginalization, further fueling the al-Shari'a advocacy as the only way to return power back to the region.

Things became worse in 2001, when Obasanjo began to actively campaign for a second tenure against the wish of many within the region. Attempts to make Obasanjo change his mind, fell on deaf ears. At this stage many more activists and politicians in the region began to openly call for a change of government and the deposition of Obasanjo. In light of this opportunity, members of different religious activist groups embarked on a barrage of consistent campaigns for the establishment of Sharia law and al-Shari 'a in the region. By 2001, all the states within the region - 12 of them - had introduced Sharia law as their respective states' legal penal code. People like Yusuf Mohammed, the would-be spiritual leader and one of the main founders of BH, who had worked with some of the main established Salafi networks in the region in their al-Shari 'a advocacy, started openly calling for the enthronement of al-Shari'a in the Nigerian federal government. By 2003, most of the respondents explained, they had started encouraging Salafi-oriented youths to follow Mohammed Ali, and relocated to a camp in Kanama (a remote village close to the Nigerian border with the Niger Republic), in pursuit of a true Islamic lifestyle that they hoped would enthrone real al-Shari'a.

Fallouts from the al-Shari'a Advocacy vis-a-vis Intra-Ideological Dispute between Yusuf and the Main Salafi Networks in Northern Nigeria Before becoming the spiritual leader of BH, Ustaz Mohammed Yusuf was a well-known and charismatic figure within the two main Salafi networks in the region (Izala and the Ahlus Sunna), rising to the position of youth leader at the Ndimi mosque18. At the peak of the al-Shari 'a advocacy in 1999, he had travelled to different parts of the region, preaching and representing the Ahlus Sunna in several TV and radio debates. By the early 2000s, he had become a leading protégé of Ja'far Adamu, one of the leadership figures in the Ahlus Sunna. At some point he was known to have been considered by Adamu as one of the most promising upcoming leaders in the Ahlus Sunna circle (Amaechi 2017; Brigaglia 2012a; 2012b). The relationship between the two men had grown during their time at the Ndimi mosque. All these changed after 2002, when Yusuf began to insist on the traditional Salafi teachings and strict adherence to Salafism, which was, inter alia, an abandonment of the Nigerian constitution, in exchange for an al-Shari 'a-based theocratic state. This was at odds with both Adamu and many within the Ahlus Sunna position. In the succeeding years, it would culminate into heated public verbal disputes that probably increased Yusuf s proclivity to establish and encourage the youths to join the Kanama camp and later establish his own organization.

In recent BH scholarship (eg. Anonymous 2012; Kassim 2015), Yusuf s doctrinal disputes with the main Salafi establishments has been identified as a local manifestation of the tension existing between the two main trends in the global Salafi discourse - the 'quietist' (representing Salafis who focus on nonviolent methods of propagation, purification, and education) and the ' jihadist' (those who call for violence and revolution to overthrow the governments of their countries). In a broad sense, it can be argued that Yusuf took the latter, more extreme, and austere position. While agreeing with the Ahlus Sunna on the desired struggle to establish a Muslim form of government he, however, vehemently disagreed with them on how this system would be attained. For him, it was 'lawful'/'permissible' to change to that system through violence. He rejected a participating in democratic elections, employment in the government, and acquisition of Western education.

For him, all these were products of democracy, and hence are haram (unlawful/forbidden)19. All these did not 'sit well' with the main Salafi establishments. By the end of 2002, it ultimately led to the expulsion of Yusuf from the Ndimi mosque. However, before his expulsion, Yusuf had already won the hearts and souls of many youths whom he worshiped with and who studied under him at the Ndimi mosque. Under his doctrinal tutelage, most of them later relocated to Kanama to start the new organization, which was devoted to the ousting of the corrupt Nigerian government and Western education which they regarded as antithetical to the true al-Shari 'a system.

Two main issues made joining the Kanama camp very appealing for the new generation of Salafi youths. First, the inability of the implementation of the Sharia law by Salafi activists, to live up to its religious promise to work with other Islamic establishments in the implementation of Sharia law in the region. Kassim (2018:14) calls it 'jihadi revisionists'. They shelved some of their Salafi radical tenets, choosing to become more 'moderate and less critical of the State' (Kassim 2018). This meant amending their ideologies or framing it in such a way that it accommodated the possibility of working within a Western democratic system. Paradoxically, the Sharia reforms, which had been championed by activists within the main Salafi networks, ended up empowering the Sufis and forced the Salafis to accept a doctrinal compromise. This was the very canon they had always wanted to correct. Second, the implementation of the Sharia law did not necessarily create any economic boom20 or a secure and corrupt-free environment, as many Salafi activists, who had been very vocal during the al-Shari'a campaign, had claimed. Despite the region's public show of religious consciousness and the implementation of Sharia law, the region remained characterized by political corruption and a lack of accountability in the public offices. There was also a tremendous lack of basic infrastructure and health care, as well as poor education systems and youth unemployment. The government's public offices not only remained platforms to acquire easy wealth, as they still acted as avenues for other lucrative criminal enterprises. Instead of the expected dividends of democracy, the citizens remained impoverished.

All these further exacerbated the tensions between the older Salafi leadership and younger generation of Salafi activists, who created silent protests among the young Salafis. Thus, they increasingly perceived the older Salafis as colluding with the government in sabotaging the region's al-Shari'a project. Hence, they found a solution in the Kanama camp and therefore an opportunity to live an authentic Salafi lifestyle, with prospects of economic prosperity and freedom from all the anti-Islamic practices of the Nigerian government and the old Salafi establishments. With the encouragement of Yusuf and under the leadership of the Nigerian-born member of the al-Qaeda movement, Mohammed Ali, the group took the name Jama'atuAhlis Sunna Lidda'awatiwal-jihad (the People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad). However, for their austere Salafi-motivated lifestyle that mimicked the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Nigerian public started referring to them as the ' Nigerian Taleban' (Onuoha 2015).

Al-Qaeda Influence: Connecting Material Resources to the Establishment of the Kanama Camp

Before now, it was difficult to relate al-Qaeda to the establishment of the Kanama camp. In fact, some previous research (Smith 2016; Walker 2016; Amaechi 2017) saw the Kanama camp more as a secluded community that housed mostly youths from the Ndimi mosque and other Salafi centers in the region, rather than a specific al-Qaeda camp. However, in the aftermath of recent research (Kassim & Nwankpa 2018; Kassim 2018) and some newly released letters detailing the internal functions and the cooperation between BH and al-Qaeda, it became clear that al-Qaeda was involved in the formation of the Kanama camp that influenced the evolution of BH.

Letters between members of BH and AQIM, as well as internal al-Qaeda documents detail how the Kanama camp may have been fully funded by the al-Qaeda top leadership. The documents explain how Mohammed Ali, who acted as the leader of the camp, was not just a member of al-Qaeda, but a direct coordinator of the Osama bin Laden violent intended jihadi activity in Nigeria. He (Ali) had contact within the main al-Qaeda leadership and its affiliate group, the Salafi Group for Preaching Combat (GSPC)21. Before returning to Nigeria, he studied from 1991 to 1996 under the late al-Qaeda leader's teachers at the International University of Africa in Khartoum in Sudan (Kassim 2018:9). During this period, he fought in Afghanistan with al-Qaeda. Before leaving Sudan, he reportedly met with Osama bin Laden, during which the latter asked him to organize a cell in Nigeria, with a budget of 300 million naira (approximately US$3 million at that time). It was probably some of these funds which enabled Ali to establish the camp when he returned to Nigeria in 2002.

This idea of al-Qaeda's connection in the founding of the Kanama camp was further corroborated by interview data from the respondents. In discussing the role of Yusuf in the actual establishment of the Kanama camp, two interviewed Salafi scholars were quite certain that Yusuf could not be involved in the actual formation and running of the Kanama camp. They explained how Ali had traveled to many states in the region when he returned to Nigeria around 2002, trying to propagate his new 'extreme jihadi ideology' to the religious leaders in the region, including the Salafi scholars. The only person who supported that kind of message, as they explained, was Yusuf. However, two of them were quick to point out that Yusuf also differed22 from Ali when it came to the question of the appropriate time to start the jihad in Nigeria:

On the issue of when was the right time to start jihad, Yusuf and Ali never agreed. While for Ali, Nigeria as at then was ripe for jihad, Yusuf favored the idea that they should delay the jihad until there is no excuse of ignorance by the political leaders that they should govern by the only law approved by Allah.. .Other than this, Yusuf also wanted to wait until they have more popular support in the region.

When it became obvious that Yusuf was not going to give in on the issue of starting an armed struggle against the Nigerian state after the Kanama camp has been established, Ali and his group declared takfir23on Yusuf. Yusuf recounted this takfir in an audio lecture many years later24. However, considering Osama bin Laden's long-term strategic interest for the region, funding this project made perfect sense. Through such financial support, he would not only have the opportunity to recruit new activists to the al-Qaeda cause, he would also have a better opportunity to attack the Western interests in the region.

Through al-Qaeda's support, Ali was able to establish the camp at Kanama. He attracted youths from different parts of the region to the camp. Given the huge financial resource and the disposition to flee the antecedents of the intra-Salafi disputes at the time, he did not have significant problems attracting many other youths to become Salafi adherents to the Kanama camp. By mid-2003, he and his activists had also (probably in line with al-Qaeda's directive) started training and waging an 'armed violence struggle' from Kanama against the Nigerian state. They attacked government buildings, including police stations, a local government secretariat, and a government lodge (Kassim 2018:11). Specifically on 21 September 2003, they staged attacks against police stations in Bama and Gwoza (in the neighboring Borno state). In this instance, they overpowered the police officers at the stations and stole most of their local ammunition, including at least five AK 47s. The Nigerian government could not just sit and watch them start such a violent attack. In collaboration with the local Yobe state police, they launched a violent crackdown that dismantled the Kanama camp within four days. The result of the raid was that Muhammed Ali and dozens of his troops from the camp were killed. Yusuf himself, who was at this time known by the Nigerian authorities, fled to Saudi Arabia. He stayed there for about one year. He was only allowed to return to Nigeria through the assistance of many political figures within the region (particularly the then deputy governor of the Borno state, Alhaji Adamu Shettima Yuguda Dibal, and Adamu, his old mentor), on the promise that he would not propagate violence anymore. Following his return, he moved the group's base from Kanama to Maiduguri. Given more funding from Saudi Arabia, he built a new center that attracted some of the former troops from the Ndimi mosque, who were part of the dismantled Kanama camp. Thus, the group grew from strength to strength, becoming one of most vocal activist jihadi group in the region.

Conclusion

This article presented the socio-political and organizational background upon which BH evolved in Northern Nigeria. This was presented through an analysis of five main political opportunity structures: The Northern Nigerian culture of Islamic activism, its colonial legacy, the Nigerian democracy in 1999, the fallout from the al-Shari'a advocacy and the intra-ideological dispute between Yusuf and the Salafi networks, and the financial support they received because of their cooperation with al-Qaeda. The central argument was that these main structures/conditions laid the foundation and provided the political opportunities upon which Mohammed Ali (2002 in Kanama) and later Mohammed Yusuf (2005 in Maiduguri) established the organization in the region.

First, the article traced BH's religio-political activist nature to the history of the Islamic activism of Usman dan Fodio's jihad and the subsequent establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate, where the use of violent activism was justified as a legitimate tool against Hausa despotic rulers and the state. It explained how this unique religio-political history had bequeathed the region with a unique identity that encouraged the formation of activist groups and the use and justification of violence as a legitimate tool against the state. Based on this history, Islam became an important resource upon which political activism was galvanized and mobilized against the state within the region.

This phenomenon was further exacerbated by the colonial legacies and consequent secular Nigerian state that emerged at independency. With the region' s al-Shari'a foundation being threatened by the Western-based system from the colonial state, more opportunities for religious opposition against the state emerged. The Nigerian political agitations also played a part in making Islam the marker of identity and a tool for political contention in the region.

In a situation where one region or religious group is not represented in the country's federal character, it is easily interpreted as political marginalization, and Islam is easily used as a tool to galvanize a sociopolitical activism against the state. This was the case in the dawn of a new democracy in 1999, when Obasanjo, a Southern Christian and former military head of state became the President of Nigeria. The political opportunity that emanated from this led to an increased advocacy for Sharia law activism, conceived to be the right system to return the region to its correct economic, religious, and political path. Led by different Islamic organizations, this became the trademark of socio-political activism within the region. By 2001, all of the 12 states in the region had adopted Sharia law as their respective states' penal codes. The democratic freedom made this pretty easy. However, the enthronement of the Sharia law did not create the much desired 'true Islamic' environment, as most of the activists who championed it within the Salafi networks had promised. It also did not necessarily create the much-needed economic boom or the procurement of a corrupt-free environment, as the Salafi activists had advocated during the al-Shari 'a advocacy. This, as time went on, ignited a silent protest among young Salafi adherents, who felt betrayed by the main Salafi establishment.

Empowered by the young rising Salafi activist, Yusuf, who had pounced on the political opportunity created by this unrest, as well as the feelings of political marginalization in the region (from Obasanjo's presidency), these young Salafi adherents left the old Salafi establishments to join the newly established al-Qaeda-funded movement in Kanama. At Kana-ma, these groups of youths easily found a natural home to practice their faith without being compromised by the corrupt Islamic establishments and their Nigerian state collaborators. However, within a few months of its establishment, the Nigerian government dismantled the camp. Ali, the leader of the group and many other members of the group were killed, but Yusuf, the spiritual leader of the group, was not killed. He fled to Saudi Arabia. Upon his return he moved the group's base from Kanama to Maiduguri and reconnected with some of the former Kanama adherents whom he nurtured at the Ndimi mosque before they moved to Kanama.

All these demonstrate the significance of political opportunity structures in the formation of the Salafi-oriented groups. As the analysis validates, Salafi-oriented groups are much like ordinary social movement organizations. They do not evolve from a vacuum - instead, they are sensitive to specific conditions and political structures within the socio-political environment that they identify with. These structures provided the necessary political opportunity to establish these groups. In the presence of such political structures, activists can draw from these political opportunities to establish their organizations.

In contrast to previous analyses on the origin of BH, this article shows that political structures (particularly in the form of the availability of funds) are also a very significant condition for the establishment of SOMOs. The ability to form new associations or collectivize activism (religio-political or not) by religious activists such as Mohammed Ali and Mohammed Yusuf, had a lot to do with their ability to mobilize resources. These resources provide movement activists with the political opportunity and rational orientation for action. These activists are like ordinary social movement activists. They do not necessarily operate under the sway of ideological conflicts, sentiments, or emotions. Instead, they operate in terms of the logic of the availability of incentives, costs, and benefits, as well as opportunities. In the absence of these resources, even when there are many grievances and ideological motivations, activists may not be necessarily able to mobilize and form new organizations.

References

Alao, A. 2013. Islamic radicalisation and violent extremism in Nigeria. Conflict Security and Development 13, 2: 127-147. [ Links ]

Amaechi, K.E. 2017. From non-violent protests to suicide bombing: Social movement theory reflections on the use of suicide violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram. Journal for the Study of Religion 30, 1: 53-78. [ Links ]

Amaechi, K.E. 2019. Violence and political opportunities: A social movement study of the use of violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram. PhD thesis, Department of Department of Religious Studies and Arabic, Unisa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Anonymous. 2012. The popular discourses of Salafi radicalism and Counter-radicalism in Nigeria: A case study of Boko Haram. Journal of Religion in Africa 42:118-144. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & V. Clarke (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77-101. [ Links ]

Brigaglia, A. 2012a. Ja'far Mahmoud Adam, Mohammed Yusuf and al-Muntada Islamic trust: Reflections on the genesis of the Boko-Haram phenomenon in Nigeria. Annual review of Islam in Africa 11: 35-44. [ Links ]

Brigaglia, A. 2012b. The career and the murder of Shaykh Ja'far Mahmoud Adam (Daura, ca. 1961/1962-Kano 2007). Islamic Africa Journal 3, 1: 1-23. [ Links ]

Brigaglia, A. 2015. The volatility of Salafi political theology, the war on terror and the genesis of Boko Haram. Diritto e Questioni Pubbliiche 15, 2: 175-202. [ Links ]

Burke, C.J. 2018. The culture of terrorist propaganda in Sub-Saharan Africa: A case study on Al-Shabaab's use of communication technologies in Somalia and Kenya. Master's dissertation, Fletcher School, Tufts University, Medford. [ Links ]

Comolli, V. 2015. Boko-Haram Nigeria's Islamist insurgency. London: Hurst. [ Links ]

Fafunwa, A.B. 1991. A history of education in Nigeria. Ibadan: NPS. [ Links ]

Falola, T. 1998. Violence in Nigeria, the crisis of religious politics and secular ideologies. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. [ Links ]

Franks, J. 2006. Rethinking the roots of terrorism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Gilles, K. 2002. Jihad: The trail of political Islam. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Gunning, J. 2009. Social movement theory and the study of terrorism. In Jackson, R., M. Smyth & J. Gunning (eds.): Critical terrorism studies: A new research agenda. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Haron, M. 2016. The walking Qur'an: Islamic education, embodied knowledge, and history in West Africa. African Historical Review 48, 1: 178-181, DOI: 10.1080/17532523.2016.1227605. [ Links ]

Hentz, J. & H. Solomon (eds.) 2017. Understanding Boko Haram and insurgency in Africa. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Juergensmeyer, M. 2003. Terror in the mind of God: The global rise of religious terrorism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Kassim, A. 2015. Defining and understanding the religious philosophy of Jihadi-Salafism and the ideology of Boko Haram. Politics, Religion & Ideology 16, 2-3: 173-200. [ Links ]

Kassim, A. 2018. Boko Haram's internal civil war: Stealth Takfir and Jihad as recipes for Schism. In Zenn, J. (ed.): Boko Haram beyond the headlines: Analyses of Africa's enduring insurgency. A report for the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, United States Military Academy. Available at: https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2018/05/Boko-Haram-Beyond-the-Headlines.pdf. (Accessed on 14 October 2018. [ Links ])

Kassim, A. & M. Nwankpa (eds.) 2018. The Boko Haram reader: From Nigerian preachers to the Islamic State. London: Hurst. [ Links ]

Loimeier, R. 2012. Boko Haram: The development of a militant religious movement in Nigeria. Africa Spectrum 47, 2/3: 137-155. [ Links ]

Moghadam, A. 2008/2009. The Salafi-Jihad as a religious ideology. A report for the Combating Terrorism Centre at WestPoint, CTC SENTINEL 1, 3: ff. Available at: https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2010/06/Vol1Iss3-Art5.pdf. (Accessed on 17 October 2018. [ Links ])

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 2017. Closing the book on Bin Laden: Intelligence community releases final abbottabad documents. Available at: https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/press-releases/press-releases-2017/item/1737-closing-the-book-on-bin-laden-intelli-gence-community-releases-final-abbottabad-documents. (Accessed on 17 October 2018. [ Links ])

Onuoha, F. 2015. Boko Haram and politics: From insurgency to terrorism. In Pérouse de Montclos, M. (ed.): Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria. Los Angeles: Tsehai Publishers. [ Links ]

Salisu, A.M., & S.A. Abdullahi 2013. Colonial impact on the socio-communicative functions of Arabic language in Nigeria: An overview. Canadian Social Science 9, 6: 204-209. [ Links ]

Smith, M. 2015. Boko Haram inside Nigeria' s Unholy War. London: I.B. Tauris Publishers. [ Links ]

Solomon, H. 2015. Terrorism and counter-terrorism in Africa - fighting insurgency from Al Shabaab, Ansar Dine and Boko Haram. Basing-stoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Teplesky, M.J. 2016. Salafi-Jihadism: A 1400-year-old idea rises again. Monograph from the School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Available at: https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2018/05/rise%20of%20salafi-jihadist%20groups.pdf. (Accessed on 17 October 2018. [ Links ])

Thurston, A. 2015. Nigeria's mainstream Salafis between Boko Haram and the state. Islamic Africa 6, 1: 109-134. [ Links ]

Walker, A. 2016. Eat the heart of the infidel: The harrowing of Nigeria and the rise of Boko Haram. London: Hurst. [ Links ]

Wiktorowicz, Q. 2004. Islamic activism and social movement theory. In Wiktorowicz, Q. (ed.): Islamic activism: A social movement theory approach. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Wiktorowicz, Q. 2006. Anatomy of the Salafi movement. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29: 207-239. [ Links ]

1 The ethical clearance number obtained from the University of South Africa for the research done in this article is 2016-CHS-013.

2 The authors express special gratitude to Prof Johan Strijdom and Prof Auwais Rafudeen for their insightful comments on the study that led to this article. The authors are also grateful for the two anonymous reviewers of the original manuscript. Their constructive criticism and comments have helped in shaping this article to its present form.

3 Rather than to use the term 'Salafi-jihadism' which is frequently used within certain literature (Anonymous 2012; Brigaglia 2012a; 2012b; 2015; Thurston 2015; Kassim 2015; 2018), we have intentionally adopted the term 'Salafi-oriented Movement Organization' as a more appropriate term to designate a group such as BH. Even though Salafi-jihadism points to a more precise ideological representation of these kinds of organizations, it seems to connote an ' exceptionalization' of one form of activism called 'jihadi armed violence' as an element defining such groups. This is regarded as slightly problematic.

4 SOMO is here used in a very broad sense. It refers to those activist groups within the Salafi tradition who use ideologies within Salafism to propagate or implement what could be regarded as political, social, or religious activism within the context of the modern nation-state (Amaechi 2019). These agendas include a broad repertoire of social movement activism such as protests, campaigns, seminars, general da'wa (religious proselytizing), etc. Typical examples of such organizations are al-Qaeda, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al-Shabaab, Islamic State (IS), and the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA, known in English as the Armed Islamic Group).

5 Several efforts made to obtain permission and interviews were without success. Amaechi (2019:64-66) provides detailed information regarding efforts to get access to BH activists.

6 Cf. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2017).

7 Braun and Clarke (2006) have developed a thematic analytic approach that aims to identify important and significant patterns in qualitative data. This approach entails six main steps for identifying and analyzing data: Step 1: Become familiar with the data; Step 2: Generate initial codes; Step 3: Search for themes; Step 4: Review themes; Step 5: Define themes; and Step 6: Write-up.

8 The first phase of Islam came through trade relations in the 12 century, when Islamic scholars and North African trade merchants made in-roads in the trade routes of the Sahara desert (Comolli 2015:13; Smith 2015:31).

9 Fulani or Fula is believed to be one of the largest ethnic groups dispersed in the Sahel and West Africa, especially in Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea. The group is known mostly for its political sagacity and nomadic lifestyle. The biggest group of Fulanis now lives in Northern Nigeria and Senegal.

10 The Hausa city states represent a group of neighboring pre-colonial autonomous states that dominated the present-day Northern Nigeria. They are situated north of the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers (in the present-day Northern Nigeria), between the Songhai empire in the west and that of the Kanem-Bornu or Bornu in the east. Prior to the jihad of dan Fodio and his subsequent domination of Islam, these city states had lived side by side and were interconnected in the mid-14 century by loose alliances. It was until the jihad of dan Fodio that some of these states were united under one Islamic Caliphate known as the Sokoto Caliphate.

11 British colonization, by the way, was achieved through conquest and subjugation. During this dark era in the region's history, states and semi-independent communities around the Caliphate were forcefully conscripted as part of the British state.

12 The Royal Niger Company was a mercantile company, chartered by the British government in the 19 century. The company existed for a comparatively short time (1879-1900) and was instrumental in helping the British in the colonial days to take control over the area of the lower Niger river, against the German competition.

13 It is important to note that, while enthroning the colonial system, the British had retained the region's pre-existing administrative structures. However, the incompatibility of the deeply entrenched Islamic cultural values within the region would still make governing the region very challenging.

14 Studying the Qur'an under the Tsangaya school system, they were supposed to share in the same characteristics as the al-mahajirun of Medina. The students were expected to have left their homes and families and should have no other means of livelihood. However, on study-free days (mostly Thursdays), they could engage in menial jobs normally assigned to them by their teachers. With this, the students were able to sustain themselves on an economical level. The teacher himself did not necessarily reside in one particular place or town. He was often expected to be engaged in fulltime studies and learning of the Qur'an and other Islamic sciences.

15 The British had developed a distinctive policy of indirect rule, which made it possible for them to govern the region with the consent of the traditional rulers. They retained the administrative system of the Sokoto Caliphate, with Sharia law as the recognized legal system, even to the areas in the region where the majority of the population were ' pagans'. Emirs were allowed to largely exercise their administrative powers as they had done before, as long as they were accountable to the colonial government. These concessions, however, have been described as made for administrative convenience (Falolo 2009), rather than to accommodate the region's cultural values.

16 It is easy to confuse the idea of al-Shari 'a, as one Salafi scholar explained, with a mass conversion of all Nigerians to Islam. What al-Shari 'a meant for most of its advocates is 'a unification of political authority and religious authority...a situation, whereby the country's political and moral compass would be drawn from Islam...and not from the Western secular values'. Activists who campaigned for this, wanted the region to be under a system of government whereby the Sharia law would serve as the state's legislation guide. They favored a situation whereby the state's legitimacy would be drawn from Islamic traditions rather than from the Western civilization. This appeared as a step towards freedom from colonialism, from Western subjugation and emancipation that were associated with colonialism within the region.

17 This is different from the situation before this time. Al-Shari 'a activism in both the colonial and independent state had always been contentious and evoked ethnic/religious tensions. The situation was so bad that a 1988 al-Shari'a constitutional proposal brought forward in the country's National Assembly, brought the House to a standstill. The then new military president, General Ibrahim Babangida, had to intervene and ban all Shari'a-related discussions in the House of Assembly (Falola 1998:94).

18 The Ndimi mosque was a very popular mosque in the city of Maiduguri, partly because of its impressive structure. The name 'Ndimi' is derived from one Alhaji Muhammad Ndimi, an influential businessman who financed the erection of the Mosque.

19 A more detailed description of the schism between Yusuf and the Ahlus Sunna can be found in Amaechi (2019). In recent scholarship, Brigaglia (2015) had also criticized the categorizing of schisms within Salafism based on the above-mentioned two themes.

20 In advocating for Sharia law, the activists had also argued that the introduction of Sharia law would open doors for an economic boom in the region. This by no means materialized. Three years after the 12 states in the region adopted Sharia law, they remained the poorest region in the country.

21 Since 2007, the GSPC has changed its name to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), after its alliance with al-Qaeda in 2007.

22 The schism between Ali and Yusuf has also been corroborated by recent studies (Kassim 2018:10-11). In discussing this schism, Kasim explained that they differed on two main positions that other Salafi clerics in the region (especially after 2000) commonly accepted: First, the issue of ruling by any source other than God's laws or replacing the Sharia law with secular laws. For both men, this was a major unbelief and polytheism, and in fact should lead to excommunication from Islam (Kassim 2018:13). The second issue was about al-'udhr bi-l-jahl and Iqamat al-dalil/al-Hujja (the issue of the declaration of takfir on political rulers). Here both men also agree that it is accepted to declare takfir even before tafsil (investigation by Islamic scholars) on such rulers who rule by laws other than al-Shari'a. However, both men disagreed on when it would be appropriate to declare this, and thus on the time for jihad. For Ali, it was not obligatory to establish the Islamic evidence on the political rulers before declaring jihad against them, because none of them could claim to be ignorant of God's command to rule with his laws as opposed to secular laws. Yusuf, on the other hand, believed that, before embarking on jihad on such apostate rulers, Islamic evidence (Iqamat al-dalil/al-Hujja) should be established against them through proselytism.

23 Takfir is the process of labeling fellow Muslims as infidels for the purpose of supporting or justifying the use of violence as representing 'the ultimate form of devotion to God and the optimal way to wage jihad' against such labeled individuals (Moghadam 2008/2009:62).

24 Yusuf Mohammed details this in his lecture, ' Clearing the doubts', recorded in 2006/2007 in Kano. We have not heard the audio version of this lecture ourselves. However, a detailed written version of the lecture has been presented by Kassim and Nwankpa (2018:35-41).