Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.31 n.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a11

AFRICAN INDIGENOUS RELIGION, AFRICAN CHRISTIANITIES, AND THE FUTURE OF RELIGION

A Faith that Does Justice: The Public Testimony of Oliver Tambo1

Jonathan D. Jansen

Education Policy Studies, Stellenbosch University. jonathanjansen@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Throughout the 20th century, mission-educated black men rose to prominence in the African National Congress while simultaneously holding leadership positions in the church. Yet, less is written about the faith of these men, and more about their politics; even less studied is the spiritual life of political leaders, what Nelson Mandela, in reference to his struggle companion, Oliver Tambo, called 'the essence' of man. Drawing on the construct of inferiority, this article offers a re-assessment of public testimonies about the ANC's longest serving president, demonstrating how the internal workings of Tambo's faith came to be expressed in the external life and leadership of this devout Christian activist.

Keywords: religion and politics, interiority, biography

'We may never be able to discover what it was in your essence which convinced you'

(Nelson Mandela at the funeral of OR Tambo 2 May 1993)

Introduction

Many people testify to the fact that some of the great leaders of the African National Congress (ANC) were men of faith2. The founding president, John Dube (1871-1946), who studied at Oberlin College, was an ordained priest in the Congregational Church. The Nobel laureate, President Albert Luthuli (1898-1967), the son of John Bunyan Luthuli, was confirmed in the Methodist Church and became a lay preacher. Similarly, President Oliver Tambo (19171993) applied and was accepted for ordination as a priest in the Anglican Church - an ambition derailed by his arrest with others, shortly afterwards, on a charge of high treason.

At first glance, none of this is surprising, since black African elites at the turn of the 20th century were normally sent to mission schools, given the lack of state schools at the time (Elphick 2012; Freedman 2013; Moloantoa 2016). Their parents were often converts to Christian faith and reared their children in the values of the church. It is in this context that one should understand Nelson Mandela's reflection: 'Without the church, without religious institutions I would never have been here today...Religion was one of the most motivating factors in everything we did' (Mandela 1999:4).

What was different about mission-educated men like Oliver Tambo, was the fact that they found a way to reconcile their Christian faith with their liberation politics. These were not cloistered priests or pastors detached from the pressing social, economic, and political concerns of the day. This observation is compelling - how great men (in this case) of Africa's oldest liberation movement lived their faith through the long and difficult struggle for freedom which none of these three leaders (Dube, Luthuli, and Tambo) would see fulfilled in their lifetime. A further point of interest is the kind of politics that was made possible within the ANC by the people with these faith commitments and how that might contrast with the moral state of the party 25 years since the death of perhaps its most devout leader, Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo.

This meditation is also necessary because liberation movements generally eschew open talk about religion, let alone the spiritual life of each of their leaders. There are many reasons for this in the context of the ANC. One is an awareness of the potentially divisive role of competing religious commitments of members. When a department of religious studies was eventually set up, it was already towards the end of the exile years (1987) and then probably to manage the growing stream of South African visitors, often including representatives of churches, to meet with leaders of the ANC (Macmillan 2013:184). Even so the ANC's approach has been to speak of itself, the irony of language notwithstanding, as 'a broad church' that accommodates diversities of ideology and belief.

Another reason for the avoidance of religious talk in liberation circles was the discomfort of dwelling on spiritual matters often regarded among the communists in the movement as other-worldly concerns where the focus should be on the material basis of the struggle here-and-now. In the exiled community, Christian talk was even sometimes associated with spies trying to infiltrate the organization3. The ANC's way of dealing with this discomfort was to relegate religious issues to the private sphere, as a personal thing and not a matter of public testimony4. In this regard the emeritus Anglican Archbishop, Desmond Tutu, tells with his trademark humor of a Thabo Mbeki who 'paced up and down outside smoking his pipe' while he was administering the sacraments to Oliver Tambo inside a London house (Tutu 2017:359).

References like these to the spiritual life of OR Tambo - or for that matter, any other ANC leader - are sparse and appear as single lines on his life and have not yet been the subject of a concentrated study. Brigalia Bam5, an Anglican woman and civic leader comments: 'Very little is often said about Oliver Reginald Tambo's lifelong, abiding and militant Christianity' (Bam 2017), and in the wake of Tambo's death, his dear friend, Father Trevor Huddleston, would lament: 'It hasn't come out nearly sufficiently in the obituaries, what a deeply religious person Oliver was and how much principle, ethical and moral principle mattered to him, far, far more than any political philosophy'6.

The concept of interiority in the life of Oliver Tambo

In telling the full story about the spiritual life of OR Tambo, I want to take a different approach to the place of religion in the life of liberation leaders than some of the references. Of the little known about the devotion of Oliver Tambo (and others, like Mandela), the primary treatment is on the exteriority of his faith - that is, the public expression of his Christian values and commitments7. First, many tributes refer to Tambo's association with Canon Collins (Canon of St Paul's Cathedral, London) who famously referred to Tambo as his African son (an appellation he himself would claim on occasion), and with Father Trevor Huddleston (Missionary of the Community of the Resurrection sent from England to St Peters in Rosettenville, Johannesburg) to whom Tambo wrote that memorable and moving letter in his last days: 'Nothing is more precious to me than our unbroken friendship over 50 years' and then, 'your concerns, Father, are also mine' 8.

Using the same frame of reference, Tambo's faith is often claimed in relation to his family's conversion, or his attendance of a series of mission schools (Methodist and Anglican), or his membership of an Anglican Hall of residence at the then Fort Hare University College, or his church attendance and familiarity with church rituals, or even his annual retreat at the Community of the Resurrection in Yorkshire, England. All of these exteriorities together reflect Tambo's circumstances and choices over the 75 years of his life. However, these exteriorities do not in themselves reveal his deep and abiding inner commitments as a Christian, that can be referred to as the interiority of his faith. What does this mean?

This notion of interiority is what the Jesuit theologian and intellectual, Bernard Lonergan, describes as foundational self-presence, a realm in which each person dwells within him/herself9 (O'Sullivan 2014:62). Interiority in this vein means both an alertness and a responsiveness to the call of the divine, something that originates from within the self. Where, for others, the response to duty might come from ingrained habits or social pressure, interiority is a response to an inner voice which calls for commitment (Dupre 1997).

The master on the interior life in Western thought was of course Augustine. For him, interiority is a place of contemplation to which one returns, for it is there, in that inner world where that truth resides, light is found, and the inner self discovered. And it is in that place of constant and anxious seeking after the divine that the call can be heard (Harding 2010).

For Lonergan interiority positions the devotee as 'always already, open to the world and to ourselves precisely because of the reflexive and relational character of our inwardness' (O'Sullivan 2014:62). Interiority does not therefore mean private, individual devotion in the sense of 'a spirituality of detachment from the engagement with the public realm' (O'Sullivan 2014:62); it is rather the outward expression of an inward devotion. Exteriority, the opposite, is not possible therefore without being present to oneself (Morelli 2012).

He heard the call

This quest to inquire more deeply into the fervent faith of Oliver Tambo emerged from a critical passage in the speech that his comrade, Nelson Mandela, delivered at his funeral, and is worth quoting at length (Mbeki 2017b:xxi):

Somewhere in the mystery of your essence, you heard the call that you must devote your life to the creation of a new South African nation. And having heard that call, you did not hesitate to act.it may be that all of us will never the able to discover what it was in your essence which convinced you that you, and us, could, by our conscious and deliberate actions, so heal our fractured society that out of the terrible heritage, there could be born a nation. All humanity knows what you had to do to create the conditions for all of us to reach this glorious end (emphasis added).

Nelson Mandela was onto something. There was much more to Oliver Tambo than the fact that he was educated at mission schools, or that he had prominent Christian friends. There was something in the deep interior of his life, however elusive, that could possibly explain his remarkable life as a moral leader of a liberation movement.

Mandela refers to the interiority of Tambo's spiritual life, as 'essence', as the area in which to try and make sense of someone once described as 'a man imprisoned by his Christian hope' (Brown 2017:331).

One way, methodologically, to make sense of the Christian, Tambo, is to rely on public testimonies. A testimony is of course a standard form of witnessing in the evangelical churches, to tell others about your spiritual transformation. This was not unfamiliar territory to Oliver Tambo at all, like on an occasion when he addressed the mainline church leaders in Britain and Ireland in order to counter the demeaning of the ANC and its leaders as 'terrorists' by the Thatcher government. Those leaders would learn of his Christian devotion and his ambitions to become a priest; they have heard of the inspiration that his mentor, Albert Luthuli - 'a Christian first, a politician second' (Samuel 2017:53)10 - had on his spiritual life. On that occasion the Tambo speech and the questions-and-answers that followed 'felt rather like an old-time testimony meeting' (Brown 2017:331).

On the road he asked his disciples: 'Who do men say that I am?' (Mk 8:33) The intention here is to draw on the testimonies of others in relation to Tambo's spiritual and humane values, as there are abundant testimonials about Tambo and his life. The goal is to compile a range of testimonies - principally, but not only from Pallo Jordan's 2017 collection of tributes (Oliver Tambo remembered) (Jordan [2007] 2017a) - that focus on his spiritual life and then to (re)interpret those eye- and ear-witness accounts with reference to the interiority or essence of the man. In the process of reinterpreting Tambo, some of the common misconceptions about the man among his closest friends will be challenged - for example, that he separated his faith from his activism. We should begin, however, with his roots.

The wellspring of his faith

Tambo's first contact was with charismatic Christians near his home - those hellfire-and-brimstone believers of the Full Gospel Church. Their Pentecostal campaign of 1930 no doubt influenced the family's spiritual trajectory, starting with the conversion of his father, Mzimeni. It was the personal and spontaneous expressions of faith among these evangelicals that touched Tambo deeply in contrast to the more scheduled rites and rituals of the Anglicans. As he witnessed an evangelist, called Matthew, kneeling in earnest prayer, Tambo remembers a life-changing moment:

I was thunderstruck. It seemed like he was talking to a friend. This was more than the prayer as I understood it. He was talking to somebody. I said to myself.. .Why can't we talk to [God] as a friend, and converse, talking to a person? That struck me, and it introduced a new dimension to my own prayer. Even as I now went back to school, some of the results were remarkable. And I knew that my prayer was very powerful (Callinicos [2011] 2017:56-57).

These 'born-again' Christians with their fiery faith were not, however, the place where Oliver Tambo would find his spiritual home. Could it be that his oft-described personality - reticent, reserved, and retiring - drew him towards the much less bouncy Christianity of mainstream Anglicanism? As he put it, reflecting on his college campus experiences (Fort Hare) that, having met the Pentecostals, 'my religious life took on a new and more personalized character. I developed a liking for the early morning Holy Communion [Anglican] service that would normally be held in a chapel, which, because it was early, attracted few people. Often I was the only one attending' (Macmillan 2013:17).

However, long before this precocious youth entered University College, he started off in a Methodist primary school where learning tonic solfa in particular shaped his long-term love of spiritual music. But school was generally boring to the young boy and so he played truant. Then a priest invited him and one of his stepbrothers to the Anglican Holy Cross Mission (near Flagstaff, Eastern Cape) and a profound episode in his Christian journey touched him:

I arrived there on Easter Day with one of my stepbrothers, and I shall never forget the moment. We entered the great church while the Mass of Easter was being sung. I can still see the red cassocks of the servers, the grey smoke of the incense, the vestments of the priests at the altar.. .it was a new world (Macmillan 2013:12).

As he moved from the transformative influence of the evangelicals in Kantolo to the Ludeke Methodist School to the Anglican Mission School of Holy Cross, Tambo was baptized at least three times - twice by immersion in a local river (evangelicals, Methodist) and the third time by the pouring of water over his head (Anglican). These acts of baptism confirmed for the young man that he had 'now' become a Christian, 'an acknowledged Christian' and a member of the church (Macmillan 2013:57). This soft competition among rural missions for the soul of Oliver Tambo had the opposite effect on the convert, for he developed a strong sense of ecumenism and the inclusion of all faiths to which he was open, being impressed by them throughout the formative years of his youth. 'As far as I was concerned', Tambo would later reflect, 'it made no difference if I was a Methodist or an Anglican' (Macmillan 2013:58).

The mission schools that shaped Tambo were nonetheless costly. His school fees were partly paid by his two sisters in England and he wrote regular letters of thanks to them, one of which revealed that he was baptized by a Bishop just before his eleventh birthday. Tambo repeated a few years of primary school, in part because he was waiting for a secondary school place that he could afford. Another priest helped him go to school at St Peter's school in Rosettenville, Johannesburg, which belonged to the Anglican Community of the Resurrection. He did exceptionally well at St Peter's and was one of the few first class passes in the country, writing a common examination (black and white) with a distinction in mathematics.

At Fort Hare he continues his Christian devotion - an abstainer from alcohol and, apparently, celibate as a student (Macmillan 2017)11, while leading the college choirs. He landed in trouble with the university authorities on a dispute whether a campus tennis court could be used on a Sunday. The authorities pronounced that the strike had to end, and with that they demanded a pledge of good behavior in the future. 'I asked the warden for time to pray about this', said Tambo and after some time in the chapel, he refused: 'It would have killed my religion stone dead - this strange agreement with the Almighty'. He was promptly expelled, but first went back to the chapel to pray where a light near the Blessed Sacrament told him '[t]hat somewhere, however dark, there is a light' (Macmillan 2017:20). Tambo left Fort Hare for a teaching position at St Peters and from there he went on to meet Father Huddleston and eventually became an active member and later on the leader of the ANC, before fleeing into exile.

Faith in hard places

It was in the difficult years of exile that Tambo's political ideas evolved, and his spiritual commitments would be tested in the furnace of material hardship, the separation from his family, the longevity of apartheid, and the death of comrades at the hands of the regime. It is this furnace that Jeremy Cronin refers to when he speaks of 'the sociology of exile, its paranoias and factionalisms' (Macmillan 2013:8), and to which Hugh Macmillan (2013:1) would attribute 'homesickness, loneliness, pain, alienation, sense of loss, and the waste of energy and time'. If one wanted to really know the essence of a man like Tambo, it would surely be revealed under those exacting years of exile.

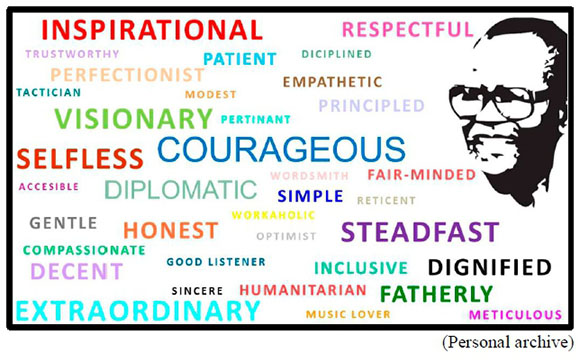

What then are the testimonies of people about this remarkable activist, humanist, and believer? The responses to this question are framed through a creative display of the keywords used at least twice - some many more - by Tambo's friends, family, and associates, and that together describe his leadership over the course of the exile years. Here is what they said of this man:

The church for and against apartheid

The faith context in which Tambo lived his life as a liberation leader is itself revealing. Through the dark night of struggle under colonialism, segregation, and apartheid, there was the fervent faith of the white Afrikaner nationalists and their political leaders expressed through the Dutch Reformed Church. These pious, devout believers saw no contradiction between the oppression of black people and the teachings of scripture. And then there were the black African nationalists and their leaders who, reading the same scriptures, came to understand the evils of racial subjugation by a white government. South Africa must have been one of a few countries where, on a Sunday, both the oppressor class and the oppressed prayed to God for deliverance from the other.

For Tambo there were two churches: Those who justified the oppression of black people, and those who fought for their liberation. In one breath he could criticize what he called 'the civilising mission' (Brown 2017:327) of the church, while acknowledging that he was a graduate of mission schools in rural and urban South Africa. He would condemn the behavior of church leaders who supported apartheid violence and at the same time seek out church leaders to join the struggle against apartheid. As already indicated, his closest friendships included great churchmen of his generation, like Collins and Huddleston. In short, for Tambo the church was neither innocent nor irrelevant in the anti-apartheid struggle and became one of the fronts of the fight for justice (Kleinschmidt 2017).

It is in this very contrast - between the false piety of white nationalists in the mainstream South African churches and the spiritual devotion of Tambo - that his interiority shines through and his witness speaks volumes. As Judith Scott (2017:353) would testify of him, 'I had witnessed so much racism and inhumanity perpetrated by those who purported to be Christian...What a contrast to the warmth of the hospitality I received at Muswell Hill (the Tambo family home in London)'.

Tambo did not therefore stand apart from the church in his personal testimony; in other words, the church was not something else, external to himself, a body to be criticized or embraced. He lived church. In Luli Callinicos' single-paragraph reference to Tambo's inferiority titled But what of Tambo's inner life?, his biographer in this studied account of the leader recognizes that he was

a private man who by and large expressed his inner self through his spiritual resources...No matter how gruelling his schedule, he would find time to pray, and whenever possible, attend church - sometimes in the early hours of the morning before the day's work began. Joe Matthews, who was his personal assistant in the sixties, observed Tambo's prayers, and the need - far too seldom - to take stock of himself (Callinicos [2011] 2017:447).

This is what church meant to him - a living testimony to the outside of what he believed in the inside. In this sense, even his closest comrades failed to understand the interiority of the man as inextricably linked to the exteriority of his testimony.

Tambo did therefore not live two lives or two compartmentalized existences as wrongly suggested by Ben Turok (2017:229): 'Oliver kept various roles and values in distinct compartments, rarely allowing overlap between them. This was why Christians with deep faith were able to relate to him in a special way as one of their own'. These two sentences contradict each other in terms of Christian witnessing. It is in fact Tambo's internal faith, his essence, that shone through in his public testimony, that drew all towards him - atheist and believer alike - as the testimonies below will show. He was not one person on the inside and another on the outside. Emeka Anyaoku (2017:270) states correctly: 'Oliver derived unfailing strength and inspiration from his faith.. .His faith bred in him a steadfastness to truth, justice and fellow feeling'.

Tambo could clearly not be, as another close observer confirms, a 'disembodied machine by his Christian values' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:448). His deep interior life would come to be expressed in his perspective on his life. For example, Luli Callinicos tells that in his intimate letters to his wife as well as his taped memoirs, Tambo would often refer to the unexpected course of his life and his altered ambitions as a consequence of divine intervention:

...his choice of school, his hope for a career as a medical doctor, his plans to become a parish priest, and Luthuli's sending him into exile to tell the world about Apartheid immediately after Sharpeville. OR and Adelaide earnestly discussed the instruction from the ANC [and] both concluded that this was God's plan for them (Callinicos 2018)12.

It could therefore not be true that of 'his Christian faith.he never spoke,' as Ronnie Kasrils puts it (Kasrils 2017:85). Here was a man who explained to Diana Collins who counseled him, that he could not rest, because, as he said, 'I was born to become a priest and talk to people of love and reconciliation' (Wastberg 2017:317). He then took to the pulpit at the funeral of her husband (Canon Collins) and read to the assembled congregation the powerful story of The Good Samaritan. Referencing the Samaritan story, Tambo concluded his commentary with the urgent question: 'Why are our fellow humans even today still being robbed along the Jericho road?' (Jordan 2017b:22).

Tambo certainly spoke his faith. One of his bodyguards recalled: '[Tambo] ensured that all of us went to church, especially on significant days such as Good Friday' (Msimanga 2017:160). When pastors or priests in the exiled movement went to seek his counsel, Tambo would encourage them to 'keep doing what you're doing to assist those in need of faith' (Mokhele 2018)13. It was the same man who, at an international consultation organized by the World Council of Churches, and disrupted by both black power and white right activists, would conclude his stirring address with the Christian preacher's clarion call: 'Who is on the Lord's side?' (Webb 2017:24).

Parenthetically, this kind of public testimony is reminiscent of the well-known and, for some in the liberation movement, uneasy declaration of his Christian mentor, Albert Luthuli, that ' the road to freedom is via the cross' (Suttner 2010)14. This is as powerful a statement of Christian conviction as any other, for the cross is central to the Christian gospel and, in particular, represents the symbol of ultimate sacrifice in the place of someone else (substitutionary death). Is this perhaps what Nelson Mandela understood about the interiority of Oliver Tambo as a Christian when his daughter, Zinzi, delivered her imprisoned father's message to a packed Jabulani Stadium in Soweto, 1985?:

Oliver Tambo is much more than a brother to me. He is my greatest friend and comrade for nearly fifty years. If there is any one amongst you who cherishes my freedom, Oliver Tambo cherishes it more, and I know that he would give his life to see me free. There is no difference between his views and mine (Mandela 1985).

The clause 'he would give his life to see me free' might sound a little over the top, but these words formed part of a revolutionary statement by Mandela to reassure the crowds that he was not making deals from prison for his own freedom without consulting the exiled leader of the ANC, his friend, Oliver Tambo. Fact is that Mandela's speeches were never hyperbolic - bold and persistent, yes, but not emotionally excessive. This is therefore a considered reflection from the other person in the duo that has been described as 'a biblical David and Jonathan relationship' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:283): Tambo would give his life for Mandela if such a sacrifice was required for his freedom.

In Matthew 27:21, 24, 25 we read the words of Jesus: 'Not everyone who says to me "Lord, Lord", will enter the Kingdom of Heaven but only the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven...Therefore everyone who hears these words of mine and puts them into practice is like a wise man who built his house upon a rock. The rains came down, the streams rose, and the winds blew and beat against that house; yet it did not fall, because it had its foundations on the rock'.

This selflessness is another way in which Tambo referred to his faith, not in words but in deeds. It is the Christian doing something rather than just say something, as Jesus said in John 14:15, 'If you love me, keep my commands'. This notion of living one's faith through what one does rather than what one professes is fundamental to the public testimony of the believer - and nobody in the ANC leadership carried this testimony to the outside world more powerfully than Tambo.

In the next quote, Kader Asmal also misunderstands this outer expression of the inner life of faith when he, like others, says of Luthuli and Tambo that '[b]oth...were profoundly religious though neither allowed [their] beliefs to obtrude on personal relationships' (Asmal 2017:34). This is only true if one regards personal faith as a barrier to inter-human relationships -something that inevitably causes friction among those who believe differently or not at all.

This was not Tambo's ecumenical and inclusive understanding of his faith - something captured in a different observation of Asmal. On receiving and reading John Bunyan's classic on Chief Luthuli, Asmal concludes that 'OR's life resembled the life of Christian in Pilgrim's Progress' (Asmal 2017:33). In short, it was in fact Tambo's faith that made such warm and inclusive human relations possible in the first place.

Tambo, in Christian terms, therefore lived the fruits of the Spirit - the outward expression of a deep, inner transformation - and everybody witnessed it. Reg September gives Tambo high honors with this extraordinary appellation: '[O]ne of the world's greatest revolutionary Christian gentlemen' (September 2017:201), thereby capturing three shades of his indivisible devotion: The freedom fighter, the believer, and the humanist. Once again, his mentor, Chief Luthuli, echoes this understanding of the oneness of faith and politics with his famous remark: 'I am in Congress precisely because I am a Christian' (Couper 2010) - almost an unthinkable public statement by an ANC leader in the 21st century.

But how does this three-part devotion come together in the life of Oliver Tambo during the hard days of exile? Consider this recollection by Rita Mfenyana. The terrible news had just reached the exiled community and its leader that the freedom fighter, Solomon Mahlangu, had been executed by the apartheid regime. Then Tambo responded: 'They have done it; they have killed him'. Mfenyana observes this about the man and that moment: 'There was pain and dejection in his face; the burden was too heavy...Then the singing of hymns and freedom songs started' (Mfenyana 2017:131).

Albie Sachs also tries to make sense of these interconnections of his devotion when he observes that 'at the core of his [Tambo's] faith was a set of principles very close to [the] humanist and rationalist values' (Sachs 2017b:254). What becomes clear from these testimonies is the notion of one man whose exterior life flowed seamlessly from his interior devotion, and people witnessed it, including his family on his infrequent visits to their London home. His son, Dali Tambo, would recall the following as he listened through the walls of their London home: ' When he would come, my mother and him would talk for hours, through the night into the next morning.

Sometimes I would hear them singing hymns for like 3 hours, seriously 3 hours in their bedroom' (Tambo 2018).

Indeed, many others would have felt the strength of this witness in their own life. Scott (2017:353) witnesses: 'My abiding memory is of the generosity of spirit and deep humanity that pervaded Oliver's whole being'. Even Tambo's protégé, and future president of the party, would acknowledge that he has set the standard for public leadership and commitment: 'OR became our exemplar' (Mbeki 2017b:269).

This capacity to reconcile the gentleness of his humanity, the strength of his faith and the resoluteness of his political mission comes together powerfully in this frequently quoted passage from Tambo's address to the World Council of Churches in 1980:

When those who worship Christ shall have, in pursuit of a just peace, taken up arms against those who hold the majority in subjection by force of arms, then shall it truly be said of such worshippers also: 'Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called the sons of God' (Macmillan 2013:184).

It is these connected qualities of Tambo, the man that gave him the moral authority to lead in those hard years. His very presence commanded respect and channeled appropriate behavior among those who fought for the liberation of their country. Commander Tsietsie Mokhele from the Angolan campus remembers that while nobody really got very close to Tambo, 'we felt strongly that we knew him enough to follow him' and that 'a significant part of what kept you going in the years of exile was leaning on him' (Mokhele 2018).

That moral authority also captured the attention of those in the broader international community whose support Tambo sought and regarded as vital to the struggle to end apartheid. Michael Siefert (2017:257) was one of those who noticed ' the enormous moral authority and dignity that permeated everything he said. People knew they were in the presence of someone whose integrity was absolute'.

Others too would tell of 'the consistent humanity of his vision and its reliance on the highest ideals of ethical conduct' (Bindman 2017:237) - an orientation which had its roots in Tambo's upbringing, for he was no doubt 'trained since childhood in the moral discourse of Christianity' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:276).

The man who held the ANC together in exile

Apart from his role in international diplomacy, selling the cause of the ANC to foreign governments, this is the most common description of Tambo's role in exile. According to his biographer, 'the bulk of Tambo's emotional energy was directed at holding together the movement' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:452).

It was Tambo's exteriority - that public witness of a private faith - that gave him the moral authority to hold together the ANC's factions and manage its fissures under the trying conditions of exile. He did more than appeal to the policies of the movement or the righteousness of the struggle: What Tambo could and did offer was the example of his life.

The challenges of life in exile threatened to destroy the ANC. A few well-researched publications, such as Stephen Ellis' External mission: The ANC in exile, 1960-199015(Ellis 2013), emerged in the past few years. These publications cast a sharp light on the long years of banishment and the struggle to survive as an organization:

-

The relentless assault on the front-line states as apartheid military power, including agents and assassins, crossed borders at will, spied on the movement, and murdered comrades. There was paranoia.

-

The abuses in the campus, including the executions of suspected collaborators. There was bitterness.

-

The early signs of corruption both among leadership and the rank and file as one dreary day passed into another. There was disillusionment.

-

The constant movement on the ground to escape death. There was genuine fear.

-

The wavering commitment under apartheid pressure of some of the front-line governments that would expose the movement, such as the Nkomati Accord between the governments of South Africa and Mozambique. There was deep disappointment.

-

The failed military endeavors such as Wankie and Sipolilo. There was dejection.

-

The threat of rival organizations - from the Pan Africanist Congress to the South African Communist Party - at various points in the exile period. There was wariness16.

-

The reports from home of mass detentions and murders before, during, and after States of Emergency. There were defections.

-

The support of the maj or Western powers for the apartheid government which presented itself as the last bulwark against a Communist takeover during the Cold War. There was frustration.

Somebody extraordinary and tough had to hold together this 1912 organization against these formidable odds, and the source of this leader's resilience was his faith. This is what one of his loyal fighters - who named his son Reginald -concluded after a long period of thinking about how Tambo kept 'all the streams' in the ANC together:

The issue of his spirituality, from where I am sitting.you needed somebody to sustain all the strengths, the streams, for we were dependent on the energies of this one person. I do not believe he was able to offer this only with his physical strength; it must have been because he is anchored spiritually (Mokhele 2018; emphasis added).

How did the anchor of his faith express itself in his behavior as a leader? We know now that he was, in the first instance, a humble and reluctant leader who referred to himself as 'Acting President in recognition of Mandela, the real President, but for his imprisonment on Robben Island'17. There was no personal ambition here and certainly no opportunism to elevate himself in the absence of the Islanders.

We know that he listened carefully and empathetically to every member, big or small, who wanted to talk to him. Once everyone around a table had stated their views or made their case he would come in, summarize the inputs and offer a position informed by virtue of what he heard. There was no rush of blood to the head or even the kind of spontaneous leadership decisions that would resolve a matter on the spot. This frustrated some, but Tambo was ponderous even if his resolve was firm.

Tambo's views as a leader of the movement evolved over time on a number of critical issues. Like others, he did not initially agree on broad membership of an essentially black African movement that once excluded Coloreds, Indians, and Whites from membership, and later from senior executive positions. He was constantly suspicious of the South African Communist Party and its likely undue influence in the ANC18. Like his mentor, Luthuli, Tambo's views on violence evolved over time to the point where he accepted the necessity of violence in response to the unrelenting violence of the South African state against black people. This position must again be seen against the backdrop of decades of petition to the post-Union government and to Western powers for relief from racialized oppression.

The point is not so much that Tambo changed his views, but that he was flexible, thoughtful, and open to conviction on the basis of argument and experience. When challenged, he was considered not intemperate, but more likely to concede a point than simply to demolish critics or dismiss hecklers. This sense of fairness in exchange and of consideration of others, enabled him to lead. Indeed, for him, '[y]ou were all equals in a debate' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:450). These qualities endeared him to restless comrades and wary representatives of foreign governments.

He was present at the river

Tambo was always present in those most difficult years of struggle. He sacrificed seeing his family in London, being mainly on visits for ANC work where the demands on his time meant far too few moments with his wife and children. He was always elsewhere as far as his family was concerned and yet always there as far as the struggle was concerned. On this point Mbeki sees his shadow hovering over much of the movement's history: 'Oliver Tambo was present.. .at all seminal moments in the evolution of the ANC and our struggle' (Mbeki 2017a:6).

One of the common refrains from the exile narrative is that he was there at the river - that critical moment in the Wankie military campaign as fighters dropped from the banks of a river along a rope into the darkness of the Zambesi below. Tambo was there as inspiration and example. There was no turning back as he baptized this group The Luthuli Attachment going to war. That sense of presence was not only physical but also spiritual and emotional, offering the connective tissue that held people together. One of his senior colleagues recalls: 'OR's life with the men...being at the river...being in the bush.his very simplicity and style, have won him substantial support and he is holding together.what is patently clear is that his leadership has been established, amongst the men in the camps and internationally' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:452).

Commander Mokhele makes a similar point, stating: 'When we were in Angola he used to come quite regularly to the MK camps. He as the Commander in Chief came even more frequently than the people below his rank who should have been doing so' (Mokhele 2018).

That sense of presence and simplicity of lifestyle was a key window into the moral leadership of OR Tambo. He was not extravagant, and he certainly was not corrupt. Comrades recalled that he sometimes slept on the floor, while traveling through the continent. He moved frequently in order to escape capture or death. He was an ordinary man eschewing displays of privilege and not abusing the authority of his standing as leader of the ANC. That is why one of his comrades observed 'a very bread-and-butter type of Christianity' and conclude that 'I haven't seen anybody more Christian than Oliver Tambo' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:448). It was also this sense of practical Christianity that lent him 'the ability to inspire the cadres spiritually, rekindling in them a sense of selfhood and personal fulfilment' (Callinicos [2011] 2017:467).

This certainly did not mean that Tambo was perfect (Callinicos 2018) or that his moral leadership prevented a minority within the exiled community from corrupt, abusive or exploitative behavior19. But the comrades knew without a doubt where their leadership stood on these matters and many would take their lead from the reluctant president. As Albie Sachs recalls, '[Tambo's] intrinsic sense of political honour made him totally and utterly opposed to attempts by people to use the name of the struggle for material accumulation, personal or family enrichment, sexual favours or individual ambition' (Sachs 2017a:7).

'The end of an error'

This was a media headline as the fourth president of the democratic South Africa was effectively fired. Jacob Zuma was in every way the antithesis of OR Tambo. Venal, corrupt, incompetent, tribal, manipulative, and vindictive, this senior leader of the movement had to defend himself against rape charges in court, face 783 charges of fraud, corruption and money-laundering, and was found by the highest court of the land to have 'failed to defend, uphold and respect the Constitution as the supreme law of the land' (Mogoeng 2016).

Zuma did not elect himself; he was the product of a movement that, despite some outstanding leaders within the party, had become corrupted at its core and this was reflected in, inter alia, the disastrous state of the public service and the state-owned enterprises. One after the other simmering publication would bring to light the depth of the corruption within the state, including the selling-off of the state to a wealthy family that South Africans have come to describe as 'state capture' (cf. Jacques Pauw 2017; Crispian Olver 2017; Adriaan Basson & Pieter du Toit 2017). It is very likely that the former president could have charges reinstated against him and that he might end up in prison.

How did the once glorious movement of Dube, Luthuli, and Tambo fall into such disrepair? What at root was the cause of the demise of the ANC not as an electoral force, yet, but as the liberation movement that held the moral high ground by virtue of its founding values and fighting history as the party that helped bring South Africa democracy? One of the main reasons for the demise of the organization was the loss of moral leadership as demonstrated in the life of Oliver Tambo. There was, again, this strong connection between the private man and the public leader; his protégé puts this well, that ' [i]t was not possible that Oliver Tambo could achieve what he did as a leader of the ANC.unless he had the personal capacity and attributes in this regard...the character of this eminent patriot and leader of our people' (Mbeki 2017a:1).

Needless to say, such moral leadership does not need to emerge from spiritual or religious devotions of leaders, and here Mandela is a good example of a moral leader who was respectful and even acknowledging of the life of faith, but for all intents and purposes Madiba was largely non-observant with respect to religion - as he once told Charles Villa-Vicencio in an interview on the subject, 'No, I am not particularly religious or spiritual' (Makgoba 2017:122). For Tambo, on the other hand, the strength of his leadership derived from his interior life, his spiritual devotion.

The difference, therefore, between Zuma and his post-apartheid administration, and Tambo and his organization-in-exile, is moral leadership. Albie Sachs, a close observer of Tambo, makes this point well, no doubt with the Zuma government in mind:

So much depended on the quality of the leadership being given at the time. If those at the top had been avid for the spoils of war, our struggle would soon have turned in on itself and imploded.. .Fortunately for us, for our struggle and for South Africa, people like Oliver Tambo... provided honest, principled and dedicated leadership.if our top leader and those around him had lacked integrity and been corrupt, then soon the whole organisation all the way down would have been engulfed by opportunism, maneuvering and self-enrichment (Sachs 2017a:20).

That was then, in the long years of exile under the leadership of Tambo. Now, under the Zuma presidency, the moral pendulum had swung the other way, as Thabo Mbeki observed of his beloved organization when he bemoaned 'the entrenchment within the ANC of a rapacious and predatory value system and the ascendance to positions of authority or major influence in the leadership structures of the ANC.at all levels of leadership' (Mbeki 2017a:17).

The question that remains is this: Is this decay of the movement, the government, and the country reversible?

Conclusion

As the Anglican Archbishop Thabo Makgoba moved towards the casket, carrying the body of Oliver Tambo for purposes of 'incensing and blessing his remains', he felt an unexpected jolt:

Accustomed to photos of OR looking like a venerable grandfather in suit and whiskered face, I was startled when I opened the lid of the coffin to find a body in full military uniform. For a moment I thought it was a trick of the forces of apartheid, but on recognising the familiar markings of the amaMpondo people on his face, I realised it was indeed OR, in the uniform of an MK soldier (Makgoba 2017:100).

In death as in life, discipleship and duty were the same thing. There could be no more powerful testimony to a faithful life devoted to the freedom of his people.

Like the external scarification on his cheeks marked the Pondo identity of Tambo, so too did the internal scarification on his heart leave no doubt as to his Christian devotion. This quest to understand his 'essence' has revealed a man whose political convictions were borne from a deep inner persuasion of the duty to serve. As a result, his politics was neither cynical nor self-serving, but committed and selfless. In this his Christian identity was indivisible from his struggle identity.

What does this meditation on the life of OR Tambo mean for the moral crisis faced by his beloved organization and the country for which he fought? It is clear from Tambo's life that leadership matters, especially under conditions of crisis and duress. However, his is a particular kind of leadership that held together a community and changed the fate of a nation. Tambo's leadership came from within through a deep conviction to a set of core values that expressed itself outwardly through service, selflessness and single-minded devotion to the struggle over decades. It is a leadership that was remarkably influential over a large territory and diverse groupings of followers inside and outside South Africa.

It may be too early to foretell the prospects for a deepening of democracy, decency, and development within a post-Zuma South Africa. There are, however, indications that the new leadership in government under President Ramaphosa might well chart a new path that reverses the erosive corruption within the state (such as in the state-owned enterprises and the tender system), the weakening of democratic institutions (such as the public protector and the prosecuting authority), and the growing inequality in basic services (such as school education and public health).

Nobody talks about rainbows anymore

Above all, the new leadership has the vital task of reinspiring hope among those who still feel exiled from the social and economic freedom for which Tambo and many others sacrificed their life. As this meditation has shown, such Tamboan leadership will have to deliver much more than well-intentioned policies (such as land reform) or sophisticated plans (such as the NDP - the national development plan). What will be required is nothing less than a courageous and determined moral leadership founded on those values that inspired OR Tambo so that those policies and plans find real purchase in the life of ordinary South Africans.

A faith that does justice

In 2017, Georgetown's president, John DeGioia, led a moving apology on behalf of the university community to the descendants of 272 slaves who were sold in 1838 and the money used to pay off the university's debts (Sullivan 2017). There is no doubt that Oliver Tambo, for whom Georgetown University has a Lecture named in his honor, would today own these words of courage and compassion spoken by DeGioia (2017): '[T]he urgent demands of justice still present in our time [and that] we build a more just world with honest reflection on our past and commitment to a faith that does justice' (emphasis added). Those words powerfully summarize the essence of Tambo - a faith that does justice - and sets the standard for moral leadership and social activism whether in post-apartheid South Africa or in Trump's America.

References

Anyaoku, E. 2017. Heroism of an exceptional order. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Asmal, K. 2017. Our lodestar. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Bam, B. 2015. The village girl who became the mother of SA elections. Sunday Times, 28 June 2015. Available at: https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/sunday-times/20150628/282054800683789. (Accessed on 11 August 2018. [ Links ])

Bam, B. 2017. Oliver Reginald Tambo: A legacy for Africa, Oliver & Adelaide Tambo foundation, 29 November 2017. Available at: https://www.mbeki.org/2017/11/10/oliver-regmald-tambo-a-legacy-for-africa/. (Accessed on 11 August 2018. [ Links ])

Basson, A. & P. du Toit 2017. Enemy of the people: How Zuma stole South Africa and how the people fought back. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Bindman, G. 2017. A model for all lawyers. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Brown, B. 2017. Social historian and theologian. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Callinicos, L. [2011] 2017. Oliver Tambo: Beyond the Ngeli mountains. 2nd corrected impression. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers. [ Links ]

Callinicos, L. 2018. OR Tambo and the moral high ground. Notes received by e-mail on 9 March 2018. [ Links ]

Couper, S. 2010. Albert Luthuli: Bound by faith. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal Press. [ Links ]

DeGioia, J. 2017. Remarks at the 'Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition and Hope'. Georgetown University, 18 April 2017. Available at: https://president.georgetown.edu/ liturgy-remembrance-contrition-hope-remarks-april-2017. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Du Bruyn, S. 2018. Personal communication with author, 7 March 2018, OR Tambo International Airport. [ Links ]

Dupre, L. 1997. Seeking Christian interiority: An interview with Louis Dupre. The Christian Century 114, 20: 654-660. [ Links ]

Ellis, S. 2013. External mission: The ANC in exile, 1960-1990. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Elphick, R. 2012. The equality of believers: Protestant missionaries and the racial politics of South Africa. Part III. Charlottesville, London: University of Virginia Press. [ Links ]

Forster, D. 2014. Mandela and the Methodists: Faith, fallacy and fact. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 40, Supplement: 87-115. [ Links ]

Freedman, S.G. 2013. Mission schools open world to Africans but left an ambiguous legacy. New York Times, 27 December 2013. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/28/us/mission-schools-ambiguous-legacy-in-south-africa.html. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Harding, I. 2010. Augustinian interiority. Available at: https://www.clarepriory.org.uk/foa/augustinianinteriority.pdf. (Accessed on 11 August 2018. [ Links ])

Huddleston, T. 1993. Obituary: Oliver Reginald Tambo. Third Way, June 1993: 8-9. [ Links ]

Jordan, P.Z. [2007] 2017a. Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Jordan, P.Z. 2017b. Speech on the occasion of the 3rd annual Oliver Reginal Tambo Memorial Lecture, 5 October 2017, University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

Kasrils, R. 2017. The glue that bonds us together. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Kleinschmidt, H. 2017. Underground Links to religious groups. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Macmillan, H. 2013. The Lusaka years, 1963-1994: The ANC in exile in Zambia. Auckland Park, Johannesburg: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Macmillan, H. 2017. Oliver Tambo, a Jacana pocket biography. Auckland Park: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Makgoba, T. 2017. Faith & courage: Praying with Mandela. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. [ Links ]

Mandela, N.R. 1985. Speech by his daughter, Zinzi, at a UDF rally to celebrate Archbishop Tutu receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, Jabulani Stadium, Soweto, 10 February 1985. Available at: http://www.mandela.gov.za/mandela_speeches/before/850210_udf.htm. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Mandela, N.R. 1999. Speech to the 1999 Parliament of the World's Religions, 5 December 1999, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Mbeki, T.M. 2017a. Lecture by the patron of the TMF, Thabo Mbeki, on the occasion of the celebration of the centenary of the birth of Oliver Reginald Tambo, 27 October 2017, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mbeki, T.M. 2017b. Oliver Tambo: 'A great giant who strode the globe like a colossus'. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Mfenyana, R. 2017. A man of many talents. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Mogoeng, M.T.R. 2016. Constitutional court of South Africa in the matter of Economic Freedom Fighters v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others; Democratic Alliance v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others. ZACC 11, Cases 143/15 and CCT 171/15, Section 83:41. [ Links ]

Mokhele, T. 2018. Telephonic interview conducted on 11 March 2018 between the author and Mokhele. [ Links ]

Morelli, E. 2012. After theory: A commonsense approach to interiority. Emory University, 28 October 2012. Available at: https://www.lonergan-resource.com/pdf/contributors/LOE-2012-11 Eric Morelli.pdf. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Moloantoa, D. 2016. The contested but pivotal history of missionary education in South Africa. The Heritage Portal, 15 September 2016. Available at: http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/contested-pivotal-legacy-missionary-education-south-africa. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Msimanga, T. 2017. OR's security unit in exile. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

O'Sullivan, M. 2014. The spirituality of authentic interiority and the option for the economically poor. Vinayasadhana 5, 1: 62-74. [ Links ]

Olver, C. 2017. How to steal a city: The battle for Nelson Mandela Bay. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Pauw, J. 2017. The president's keepers: Those keeping Zuma in power and out of prison. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. [ Links ]

Pityana, B. 2015. The inter-faith movement and the Mandela dream. Inter-Faith Council Lecture, Nelson Mandela Foundation, 5 December 2015, The Centre for Memory, Houghton, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Sachs, A. 2017a. The quiet South African. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Sachs, A. 2017b. Oliver Tambo's dream: Four lectures by Albie Sachs. Cape Town: African Lives. [ Links ]

Samuel, H. 2017. Gandhi, Luthuli, Mandela: The struggle for non-violence in South Africa. Johannesburg: C&R Printing Works. [ Links ]

Scott, J. 2017. Hospitality at Muswell Hill. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Scholtz, L. & I. Scholtz 2017. Oliver Tambo en die kommunisme. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 57, 4: 939-954. [ Links ]

September, R. 2017. A culture of service and sacrifice. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Siefert, M. 2017. A vigilant guardian. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Sullivan, S. 2017. Georgetown University, Jesuits formally apologize for role in slavery. USA Today Network, 18 April 2017. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2017/04/18/george-town-university-jesuits-slavery-apology/100607942/. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Suttner, R. 2010. 'The road to freedom is via the cross': 'Just means' in Chief Albert Luthuli' s life. South African Historical Journal 62, 4: 693-715. [ Links ]

Tambo, D. 2018. The son of Oliver Tambo in the television documentary, Have you heard from Johannesburg? Available at: http://www.clarityfilms.org/haveyouheardfromjohannesburg/. (Accessed on 12 August 2018. [ Links ])

Turok, B. 2017. The ANC incarnate. In Jordan, P.Z. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Tutu, D. 2017. Reluctant freedom fighter. In Jordan, Z.P. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Wastberg, P. 2017. An inner compass. In Jordan, Z.P. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

Webb, P. 2017. Father of a boisterous family. In Jordan, Z.P. (ed.): Oliver Tambo remembered. Johannesburg: Pan Macmillan South Africa. [ Links ]

1 An earlier version of this manuscript was presented on 15 March 2018 in the form of the OR Tambo Memorial Lecture at Georgetown University, USA. I am grateful to the reviewer and editorial comments that improved the original version for journal publication.

2 The ANC has not yet had a woman president of the organization.

3 This interesting point was made by Sophie du Bruyn whose home in exile was often a dwelling place for the traveling Tambo (Personal Communication, 7 March 2018, OR Tambo International Airport).

4 For an excellent treatment of the ANC and religion, see Barney Pityana (2015).

5 Brigalia Bam recalls receiving messages from the International Red Cross after they visited Mandela in prison, and they would communicate the same to Tambo in London by his codename 'Holy Cross Mission' - a school attended by both of them (Bam 2015).

6 Trevor Huddleston in May 1993, quoted in notes shared with the author by Luli Callinicos (2018).

7 For an example of this exteriority principle applied to the analysis of a spiritual life of a liberation leader, see Dion Forster (2014).

8 Trevor Huddleston (1993) recalls in his published Obituary to Tambo these exact words from the letter sent to him by Tambo five months earlier.

9 Lonergan is insightfully interpreted on the concept of interiority by Michael O'Sullivan (2014).

10 This, says Harold Samuel, was Chief Luthuli's public witness (Samuel 2017:53).

11 This is according to the simple and well-written account of his life by Hugh Macmillan (2017).

12 I am very grateful to Professor Callinicos for sharing these notes from her continuing research into the life of OR Tambo, in an e-mail sent to me on 9 March 2018.

13 These are recollections of 'Commander' Tsietsie Mokhele who served in the Angolan camps and studied in the Soviet Union. The telephonic interview was conducted on Sunday 11 March 2018.

14 Raymond Suttner, one of the ANC's freedom fighters, makes an attempt to unravel the possible meanings of the cross in Tambo's famous Road to freedom speech (Suttner 2010).

15 The strength of this book is the quality of its overall research program. One of its weaknesses is an obsession with proving Mandela's membership of the Communist Party, as if it mattered in the broad, tactical support of African nationalists for the mix of liberation movements and ideas.

16 Thabo Mbeki has listed these competitive challenges threatening to destroy the ANC as coming from among movements like the All African Convention (1930s), the PAC (1950s), the so-called Gang-of-Eight, as well as the Black Consciousness Movement (1970s). Of these and other challenges, 'none of these developments succeeded to displace the ANC as...the preeminent and historic representative of the oppressed' (Mbeki 2017a:3).

17 Tambo was in fact elected president of the ANC at the 1985 ANC Consultative Conference held in Kabwe, Zambia.

18 The argument that Tambo was a dishonest politician who was always an ardent supporter of the Communists is the kind of right-wing fantasy of those still fighting the Cold War today. One such fantasy is the recent article by Leopold and Ingrid Scholtz (2017).

19 From letters to Adelaide it appears that Tambo must have been at pains to explain his family's residence in London and who paid for her travels to be with her husband in Lusaka (Callinicos 2018).