Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.31 n.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a6

POP CULTURE, FAKES, AND PLASTICITY

'Everything is Plastic': The Faith of Unity Movement and the Making of a Post-Catholic Religion in Uganda

Asonzeh Ukah

Department of Religious Studies, University of Cape Town. asonzeh.ukah@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

One of David Chidester's long-term fascinations in the academic study of religion is his nuanced scrutiny of the sensorial features of contemporary religious life. Chidester uses an approach of multi-sensorial imagination of matter to investigate the plasticity and elasticity of religion to innovate and accommodate changing religious and spiritual desires and how such adaptions ensure the popularity of religious participation in a contemporary, technology-saturated society. Based on an ethnographic investigation of a new religious movement in Uganda, this essay mobilizes some of the analytical concepts developed by Chidester to think through the material dynamics of African religious life in the context of changing socio-economic, cultural, and political contexts of Africa.

Keywords: David Chidester, Owobusobozi, Faith of Unity, post-Catholic, material religion, African religion

Introduction

For David Chidester, in the scholarly study of religions in contemporary societies, 'the imagination of matter' matters1. The critical study of the phenomenon of religion provides an interpretive framework and insight that guides scholars of religion in the attempts to understand the changing interaction between humans and the sacred. In doing this, the material forms of being sacred and performing religion are important. In the long career of Chidester, this is what drove him on in his intense scholarship on religion and society. Mapping and reconstructing the religious through historical imagination are key in understanding how he engages with religious persons, organizations, and institutions. It is helpful to employ similar methodologies in understanding the African sociohistorical environment which brittles with intense religious imagination, producing equally intense and varied new religious personalities and movements. Sociologically, a new religious movement is an organization or a community that exists to produce or prevent change in the religious life of a society or an organization (Bainbridge 1997:3). The generation or prevention of change in the religious consciousness of a society requires the (re)negotiation of identity and the meaning of the sacred. In this sense, Chidester (2003:xi) characterizes a new religious movement as a ' utopian community' , the studying and understanding of which demand 'reconstructing the worldview' that animates the movement. A movement's worldview constitutes its public discourses about what is important and what not; reconstructing the social history of a religious movement is as much reassembling its social world as it is discursively reconstituting its worldview. It maps out the distinctive characters that structure the discourses, practices, and performances that define ' the parametres of a worldview' within which a group or community of faith participate and live their life (Chidester 2003:xiii). A worldview, whether religious or not, functions 'through classifying persons and orienting persons in time and space' (Chidester 2003:xviii). Specifically, a religious worldview classifies persons, time, space, and things into sacred and profane, in the Durkheimian sense (Durkheim [1912] 1995:303-311) and orients believers towards a relationship not only to non-empirical entities, but to material things with special meanings and signification (Allen 2013:109). The articulation of the internal coherence and consistency in the discourses and practices of a movement is an important method in making sense of its worldview. It offers an interpretation of the movement and the material and discursive ways in which it produces its worldview. Such interpretation, Chidester (2003:xv) maintains, 'opens up a body of material to new possibilities of meaning, significance, and understanding'. The sociocultural landscape of Africa pulsates with religious imagination and new religious movements. To understand religion in this context would be to adequately describe how it works in enabling believers to make sense of their quotidian experience and anxieties as well as how it generates the disgust of tension, conflict, and violence.

While Chidester was particularly interested in the evolution and social history of American religions, some of his analytical tools for understanding these movements could enable the present enterprise of understanding a new religious movement in Africa that has achieved both social following and political presence in parts of Africa. That a new religion attracts and retains followers implies that its unique message resonates with the believers who subscribe to its worldview, who participate in it, and in so doing reproduce and sustain it. As Chidester (2003) observes regarding Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple, the participation in the worldview that a new religion or a religious personality creates, indicates a received message. The reception of the messages as well as material cultures of new religions address how concrete social anxiety is in a society to which the religion targets its discourses and performances of 'making sacred'. Some of the interpretative and theoretical insights which Chidester deploys in his study of the Jim Jones and Jonestown disaster hold significant promise in investigating a myriad of African new religions. The rest of this article provides an analysis of the Faith of Unity religious movement in Uganda and how its material cultural production articulates a coherent and meaningful interpretation of the world according to the material experience of the founder and majority of his followers, an articulation that points to the production of a post-Catholic religion.

The Faith of Unity religion

Scholars of religion in Africa, especially anthropologists and theologians, are quick to assert that Pentecostalism, that subset of Christianity that emphasizes the power and gifts of the Holy Spirit in bringing to spiritual birth a new person with a new destiny, is the fastest growing religion on the continent (Gornik 2011; Jacobsen 2011; Wilkinson 2012; Afolayan, Olajumoke & Falola 2018). Relying on projections and estimates (in fact, guesstimates in many cases), the case is made that Pentecostal Christianity is transforming Africa, not just in the sphere of religious world-making, but in material terms of producing wealth and health, transforming the educational sector as well as political behavior of sub-Saharan Africa. Nigeria, Zambia, Kenya, and the Ivory Coast are usually used as indications of how the newfound Pentecostal religious culture has reworked the social and spiritual life of most of the people of these countries (Drenen 2013; Asamoah-Gyadu 2013; Wariboko 2014; Lindhart 2015; N'Guessan 2015; Gaiya 2015; Heuser 2015; Zurlo & Johnson 2016; Ilo 2018). In Uganda, however, the most popular and fastest growing religion is neither a branch of Christianity nor of Islam, but the Faith of Unity (FoU) religion. The country is not a stranger to new religious movements, especially considering the violent death of 924 worshipers that occasioned the finality of the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God (MRTCG) in March 2000 (Cesnur 2000; cf. Walliss 2005). Similarly, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Auma continues to be a source of concern for the security of life and property of the population in Eastern Uganda as well as Central Africa in general (Le Sage 2011). Yet, even in the face of these recent experiences of new religious movements associated with violence of apocalyptic proportion, the FoU continues to attract massive numbers of converts to its vision and version of religious experiments in the production and dissemination of the sacred in the affairs of people.

The organization, formally called the Faith of Unity Religion, used to call itself in the official Runyoro language, Itambiro ly 'Omukama Ruhanga Owamahe Goona Ery 'Obumu ('The Association for the Healing Place of God of All Armies')2. It has transmuted from an 'association' into a full-fledged 'original African religion' as described by one of the elders of the movement3. The FoU is a deliberately reclusive and world-avoiding organization - at least this was the case during the nascent years of its establishment. Founded in a village far removed from the glittering neon lights of Kampala and national gaze, FoU is located in Kapyemi, a village on the cusp of a hill in Muhurro town, with a population of 20,000 residents in the district of Kagadi, Western Uganda, some 251 kilometers from Kampala. Kapyemi also serves as the headquarters of the FoU, and its most important sacred space and sight. Until 2016, Kagadi was subsumed under the Kibaale district, which, together with the Hoima, Kiryandongo, Kakumiro, Masindi, and Buliisa districts constitutes the Bunyoro homeland. According to the National Population and Housing Census of 2014, which was released in 2017 (Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017:8), the population of Bunyoro is estimated around 2.02 million people distributed in 1,998 households, nearly 90% of who are rural-based and practice different forms of agriculture and animal husbandry. The staple crops include bananas, millets, potatoes, and cassava. As an agrarian community, land was the primary and most important economic resource for both wealth generation and status creation (Akugizibwe 2012:11). The language of Bunyoro is Nyoro or Runyoro. Historically, the present Bunyoro is the leftover or remnant of the ancient empire of Bunyoro-Kitara, founded in the 15thcentury and renowned for its feudal system of governance under a (hereditary) king known as Omukama, who combined both sacred and secular functions in his person (Kiwanuka 1968a; 1968b; Doyle 2006). The prosperous kingdom went into a steep decline because of its encounter and confrontation with the British colonialists, who perceived the kingdom 'as a bastion of the slave trade and Islam and a threat to peace and civilization' (Doyle 2000:437).

The FoU was founded by Dosteo Bisaka, popularly known and called Owobusobozi by both his followers and detractors. To the followers of Bisaka this honorific title means ' Almighty God' in Runyoro (Ndyabahika 1997:206). The primary source material for the reconstruction of the biography of the founder and the early history of the movement is the founder himself and the written records and documentation he produced in the course of the establishment of the movement. The key text the group uses, is their scripture, written by Bisaka, titled, The book of God of the age of oneness (1987)4. Understanding the context of his birth and upbringing is necessary in reconstructing the sort of worldview which Bisaka designed the FoU to produce, sustain, and reinforce among followers and neighbors. This worldview is intricately forged by careful and creative intermingling and reconstitution of elements from the Bunyoro indigenous religion and culture, its missionary Christianity, and especially its Catholic strand.

Bisaka was born on 11 June 1930 in the Kitoma Kiboizi village, in Buyanja county, Kibaale district in Western Uganda. His parents were Petero Byombi and Agnes Kabaoora. Both of them were staunch members of the local Catholic parish of Bujuni (Bisaka 1987). According to Bisaka, he spent little time with his parents, as he lived and grew up with his grandparents from the age of eight years. His father was a Catholic catechist, as was his grandfather, Alifonsio Wenkere, who was a pioneer convert at Bujuni Catholic parish. His grandmother, Martha Nyakaka, was also a Catholic convert and a captive in the palace of Mengo, where she witnessed to the martyrdom of Charles Lwanga and 21 other Ugandan martyrs in the 19th century (Ateenyi 2000:67-68). While his grandfather was occupied with church activities at the local parish, young Bisaka was tutored in Catholic teachings and doctrines by his grandmother, whose spiritual life formed a backbone and religio-moral compass for her grandson. As would become evident later in Bisaka's life, his grandmother did not only transmit the Catholic doctrines of the time to him, but also her experience of horror, conflict, violence and intolerance, and divisiveness which missionary Christianity heralded at the time in their local communities.

The grandmother's experience of the religious intolerance and violence in the Kingdom of Buganda, especially under the reign of Mwanga II of Buganda (who was the Kabaka of Buganda from 188488; 1889-97), must have left an indelible mark in the mind of young Bisaka to influence the emphasis on religious unity which is the distinctive doctrine of the FoU (Ukah 2018:15).

According to Bisaka's own testimony, 'this woman...used to teach him a lot about the goodness of God. The words he was taught stayed in his mind for a long time' (Bisaka 1987:7). The socio-religious and political consequences of the upheaval surrounding the complex martyrs of Uganda will continue to reverberate in the formation of Ugandan polity, Catholic community formation, and local religious consciousness such as the establishment of the FoU (Kassimir 1991).

Bisaka grew up and attended Mugalike school where, in 1944, he applied to enrol into the Catholic seminary where local priests were being trained. Failing to be admitted to the Catholic priesthood training program, he went to Nsamizi Teachers College, Mityana, where he was trained to become a teacher. On graduation, he was employed at Muhorro Catholic Primary School, where he taught for 35 years. Like his father and grandfather who were catechists in the local Catholic parish, Bisaka was a prominent member of the local church and leader of the parish laity. He was parish council secretary, a position that gave him access to a high-level decision-making platform in the management of the ritual life of the church. Because the ecclesiastic leadership noticed his fervent devotion, he was also appointed as the advisor to the group known as the Legion of Mary Mother of Grace Confraternity. Here he had to guide the members of the laity in their devotion to Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, as well as teach the group elements of Catholic doctrines and liaise between the group's leadership and parish and diocesan leadership of the Catholic Church. Significant in Bisaka's future ambition and mission was his musical gifts and skills which led to his appointment into the Catholic diocese of Hoima's liturgical committee. As the choirmaster of the parish in Muhorro, he was a composer of liturgical hymns for the church beyond the parish level - a practice that soon brought recognition and popularity to him, but also a grudge: The Catholic diocese of Hoima made use of his hymns in its rituals without adequately remunerating him for it (Bisaka 1987:8-10)5.

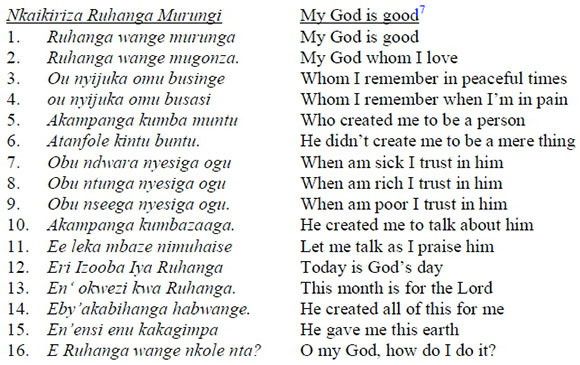

While Bisaka's sacred hymn composition started in 1966, it was not until 1975 that a radical change occurred that would ultimately precipitate the formation of the FoU. He claimed to compose sacred music through inspiration: 'What resulted from composing of hymns was that in composing a new one, he would not search for it. Instead he would receive special inspiration until he would write it down, accompanied by its melody (Bisaka 1987:9-10). In 1975, Bisaka composed a hymn, Nkaikiriza Ruhanga Murungi (My God is good). As the lyrics of this song indicate, it is theologically meaningful and cheerful - hence its popularity within and outside the Catholic Church in East Africa as far away as Rwanda6.

It is claimed that from the time this song was first used in Catholic liturgy, Bisaka started experiencing unusual vibrations in his hand: '[T]here started coming in his arms a special kind of power whenever he would sing it [Nkaikiriza] in church' , a phenomenon that increased with time and became noticed by a large circle of church members including some of the clerics, who attributed it to the 'composing of the hymn, Nkaikiriza' (Bisaka 1987:10). After five years of trying to understand the spiritual and bodily change that he was experiencing, Bisaka claimed to have heard a voice: ' [T]here came a voice of God commanding him, "You shall heal people by touching them"'. For three months Bisaka was hesitant, even afraid and unsure of what to do, but the voice was repeatedly insistent as well.

The effective date for the establishment of the FoU is 22 February 1980, the day Bisaka reluctantly touched a young woman suffering from severe and debilitating feverish conditions (generally) associated with malaria. She was instantly healed and restored to health8. The news of the event quickly spread to the nearby communities and villages resulting in people bringing many sick people to him to be healed, by physically touching them.

Doctrines and self/social construction

Over the nearly four decades since the formation of FoU, Bisaka has gathered a large following; he is explicitly believed by followers (Omwikiriza, singl: Abaikiriza) to be 'God in the flesh'. The core doctrine of the FoU is about the divinity of Bisaka. Soon after his healing activities started, Bisaka had another spiritual experience, which is described by some elders of the movement as a trance-like event where 'he went to see the Lord of hosts'; it was an experience that lasted for three days9. From this experience emerged a tripartite conception of the deity of which Bisaka was elevated into godhood with a full title of Omukama Ruhanga Owobusobozi Bisaka, loosely translated as 'the Lord God of the power of God' (Bisaka 1987:54). The remaining two personalities of the deity are the Lord God of hosts and the Lord God of holiness. His sacred duty is to fight satan and unify humankind through preaching unity, using healing to draw people together and capture their attention.

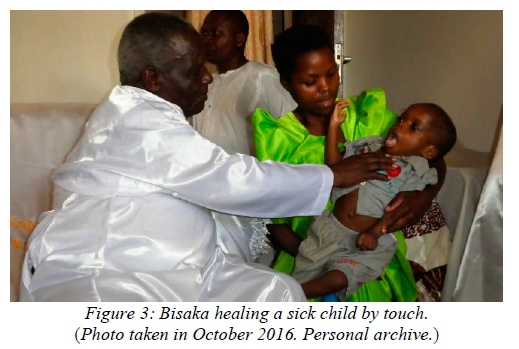

Another key doctrine of the group is to be found in its motto, Obumu nigo mani, the Runyoro for 'Unity is power". It is a pointer to the primary organizational goal of the association, which is the dissolution of disunity and materialization of ' the age of oneness' . Healing is a strategic instrument for drawing people together for Bisaka - imbued with 'the power of the Lord God of hosts' - to disseminate the message of unity. While unity is abstract and intangible, often imperceptible, healing is directly relevant and perceptible to Bisaka's followers. Primarily, Bisaka heals by physical contact (see Figure 3 below), but there are claims that the sick can even be healed when he appears to them in dreams and visions10. Healing by touch is a strong and significant symbolism of the unity of the sacred and the material; the body is the site of sacred inscription and analysis. To be touched by a god is a powerful motivation for followers of Bisaka. The FoU, who characterizes themselves as healers of disunity, both in the human body and among humanity, prides itself on being a (completely?) new religion. 'We are new and indigenous', says one of the elders with pride. With its own unique written scripture, the FoU has an unapologetically (even aggressively) antagonistic, anti-Christian (more appropriately anti-Catholic)11, anti-Western, and anti-neoliberal market ideology12. Although incorporating and claiming to restore original African religio-cultural values (such as polygyny13, the use of single names, and kneeling before elders as a form of social respect)14, the FoU is unabashedly critical of significant aspects of African indigenous religious practices and values (such as the use of charms and the honoring of local deities)15. These features make FoU a new religion in its own right, with new ideas, new scripture, new rituals and ritual economy, new sacred functionaries and vocabulary, new processes of structuring divine-human encounters, and negotiation produced in the crucible of 'sacral trauma' (Kaczyñski 2012), resulting from the interaction between Roman Catholicism and the Bunyoro religious culture16.

The national and international center of the FoU is in Kapyemi, a hilltop village in Muhorro town. Because of the role of healing in this religion and the large crowds of people who throng the venue each week, it is morphing into a healing city in its own right. The healing city of Owobusobozi is characterized by greenness, serenity, and near-absolute absence of any world reference with the exception of the majestic palace, which is the residential quarters of the leader and his wives17. With a sitting capacity of about 1,500 worshippers, the Itambiro, the hall of healing, is marked by an interior of white paint, austerely decorated with floating white and yellow ribbons and flowers - white and yellow/gold are the corporate colors of the organization (see Figure 1 above). Yellow (or gold) symbolizes heaven18.

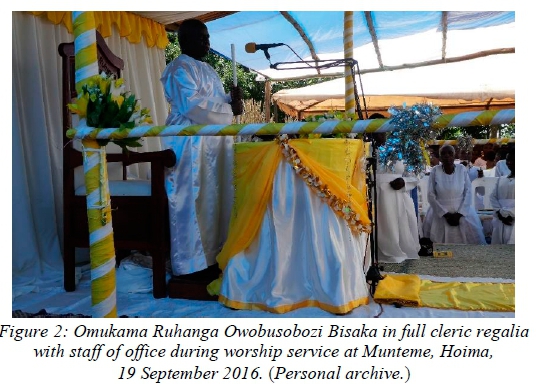

Rank and social status are important in the FoU; they help to facilitate order, peace, and the efficient performance of duty. Similarly, the color white and its significance (holiness, beauty, being set apart, purity, and elegance) are important to the FoU. To signify their new heightened awareness of the 'age of oneness', which the birth of Bisaka heralded in 1930, members change into their liturgical white robes, called kanzu, girded with a waist sash called kitara (a girdle symbolizing 'the believers' sword to fight omwohya, the Runyoro for the tempter or satan)19. They wear this white robe once they have gone through the ritual confession and spiritual scrutiny that Bisaka performs at the beginning of every worship event. Only Bisaka, who also dresses in a long white robe reminiscent of white cassock or soutane that Catholic bishops use, wears shoes or sandals on the campground. He alone wears a robe of silk; others wear robes made of cotton. The leader's kitara is designed differently: It is a look-alike of a Catholic bishop's cincture, and it is broad, elegant, made of silk, like his soutane, and knotted on the right-hand side. To crown his role and position as the inaugurator of a new ritual world and order, Bisaka carries a white crozier - a pastoral staff - symbolizing his kingship and power. This instrument of authority, made of a straight piece of stick, about 3.65 centimeters in diameter and 1.5 meters long, is only in use during liturgical services (see Figure 2 above). The social world of the FoU encapsulates continuity and change, tradition and innovation, and a careful blending of the old and the new, in restructuring both ritual aesthetics, movement, time, and space. FoU membership is ordered and organized into four categories:

-

Abakwenda (messengers of God, elders, and enforcers of norms; their kanzu has two buttons on the chest as a distinguishing mark; a special sacerdotal order of wo/men who teach and 'do not dig'20);

-

Abaheraza (servants of God; their kanzu has two knots in front instead of buttons);

-

Abakiriza (those recently incorporated into the group; new converts);

-

Abandeya (children)21.

Those outside the group are called omutali, the unconverted/unbeliever in Owobusobozi.

The sitting arrangement in the Itambiro is ranked and color-coded; the leader sits on a throne chair, with his three wives sitting on decorated white plastic chairs to his left-hand side in order of seniority. Bisaka's children sit on white plastic chairs on the left-hand side of the leader farther away from the wives. The senior leaders of the group (abakwenda) sit on blue plastic chairs. Teachers and workers at FoU schools sit on green plastic chairs. Finally, guests or visitors sit on orange-colored plastic chairs. All other members outside these categories sit on the bare floor covered with pieces of cloth they bring from home.

The facility symbolizes restful, pure, elemental simplicity and is open to all. On campground, members walk barefoot because the site is holy, and it is a sign of respect not to wear shoes or hats in the presence of the holy. Building a city that responds to, and satisfies Africa's deep-seated spiritual roots and needs, is a fundamental function which contemporary African cities often ignore but taken up by ritual entrepreneurs like Owobusobozi. Through the healing rituals performed at the Camp - mainly long hours of singing, dancing, and laying on of hands by Bisaka on all present - the FoU aims to reconstitute its members' self-understanding and perception of the world around them and its immediate environment, and from there to the larger society and world, by creating a new religio-cultural system and worldview that are based on divine imperative, direction, and intervention22. This new worldview is undergirded by the supernatural insurrection in the epiphany of Owobusobozi - a metasocial construction that supplants Euro-Christian modernity (cf. Lofland & Stark 1965).

Religious plasticity: FoU as a Catholic palimpsest

It is important to understand why a complex religion such as the FoU is flourishing in the context of Uganda which has experienced a great deal of violence connected with new religious movements. Despite coming under official government prohibition between 1989 and 1995, and the founder being persecuted by both the state and strong and powerful religious institutions such as the Catholic and Anglican churches in Uganda, twice jailed for fear of spreading unorthodox religious ideas, the FoU has more than seven million followers in seven countries (Ukah 2018:362). During an Orubung (official visit) of Bisaka to the Munteme community in Hoima on 19 September 2016, Bisaka initiated more than 800 new converts in their white flowing kanzu, waving copies of The Book of God (which is a symbol of stepping into revelatory light and right) over their heads, into the religion in one single night23. The expansion of the religion is not only in rural Uganda, it is also growing in urban and peri-urban environments, often as a challenge and an interrogation of mainstream religions such as Islam and Christianity.

In his recent book, Religion: Material dynamics (Chidester 2018), Chidester offers useful and dynamic insights into researching and understanding religion in contemporary society by stressing how religious things are put into motion, into circulation and order, and how such behavior is inherently implicated in the social construction of religion. Such an insight clarifies how the FoU mobilizes 'religious things' in constructing a new worldview as well as a social world to which converts recreate their mode of being in the world, their self-realization. Chidester (2018:177) identifies 'plasticity' as a feature of contemporary religion which ensures that it endures and reinvents its relevance: 'Plasticity signifies everything important in the imagination of matter' . On several levels and dimensions, the FoU demonstrates the cultural, social, theological, and organizational plasticity. Such elasticity enables the FoU to fabricate a dense social world necessary for the creation and maintenance of a religious worldview. According to David Unruh (1980:277), 'social worlds are amorphous and diffuse constellations of actors, organizations, events, and practices which have coalesced into spheres of interest and involvement for participants'. Social worlds are made of smaller units, namely imageries, processes, interactions, and relationships. For Unruh, social worlds produce worldviews which encapsulate and permeate 'practices, procedures and perspectives' and are marked by voluntary identification, partial involvement, and multiple identifications - for example, a participant can be a tourist or a visitor/stranger, a regular member or an insider (Unruh 1980:272, 283).

The FoU is attractive to numerous people, partly because it offers a new worldview and pushes out old colonial and missionary religions such as Roman Catholicism. As a former catechist of the Catholic Church, Bisaka was routinized in Catholic doctrines and rituals. These formed the ingredients with which he reinvented himself, a new worldview or social world, and a new religion. The metamorphosis from 'the association for healing' to 'the Faith of Unity is itself scriptural: Ephesians 4:13 speaks of 'the unity of faith and knowledge of the son of God'. The Faith of Unity is the oneness of faith necessary 'to be a perfect man' (Eph. 4:13b NKJV). The Catholic doctrine of the Trinity is reproduced with Bisaka as a replacement for God, the Son and Savior. The kanzu is a near replica of Catholic vestment or clergy attire such as the habit, and the cincture. The FoU is scriptural: The Book of God is doctrine, history, autobiography, hymnal, testimonial and polemics, and an important instrument for the scribal management of the members. Healing by touch or religious tactility resonates powerfully with some of the healing narratives of the Christian gospel. It indicates the intimacy between the sacred and the embodied or the material. The liturgical gowns, the healing city on the hill at Kapyemi, the vibrant rituals, singing and dancing, colorful environments, and unique doctrines and practices - all these are significant elements that create the FoU worldview where a new identity is made for members and communities of believers. The FoU, as a sacred worldview, is also a government for its believers: It is a power structure of creedal identity in dialogue with the values of the past - a point Kwame Anthony Appiah (2018:65-67) has recently made. As Chidester (2003:160) so succinctly says of the Jim Jones tragedy, new religious movements are individually a 'religious experiment of being human'. This human experiment is made possible through the process of ecclesiastical and theological plasticity which is evident in the FoU, where Catholic liturgical and doctrinal culture are emptied and remade in the image of the Bunyoro. Evident within the FoU is the critical analysis and strategic reversals of Catholic ritual performance, aesthetics and materiality of religion. From the vestment to the color of ritual gowns, to the staff of office, rectangular design of the Itambiro and altar, the Catholic Church and its ritual world and performativity are the palimpsest with which the FoU experiments with religion and being human in the world.

Conclusion

The FoU frames its message and product as 'good news', the message of salvation from disunity which sickness and disharmony bring, a message to prepare humanity for the end time24. Bisaka is an apocalyptic figure with a new ethical vision and practice for humankind. For the FoU and its founder, religion and the quest and desire for the supernatural present a template of religion that frames and materializes what normality is; it shows that the deviance/normality conundrum is relative to society and the sacred. One reason why the FoU has defied serious academic study until recently, is its entrenched and pervasive public perception as a cult, a dangerous, deviant, even mysterious and risky organization with religious vestiges and pretensions. Town residents and neighbors furnish legends of diablerie about the FoU and its leaders that forewarn non-members to be permanently on their guard against possible entrapment or bewitchment. Even while researching the movement, many neighbors and academics in Uganda describe the group as an evil and 'satanic' organization that did not merit the investment of academic rigor and time in understanding or explaining. The history of the FoU indicates that even in the presence of deviance or unorthodoxy of faith, is salvation, a redemptive rethinking and reorientation to human destiny and the myriad of things that threaten order and meaning in human experience. The FoU qualifies as a new religion, albeit an alternative and marginal articulation of how humans may sanely and safely approach the divine and relate with the potential threats of disorder/disunity with time, which illness and death inexorably bring to the fate of being human. This type of empathetic analysis is one of the orientations David Chidester's entire scholarship brings to the study of religious unorthodoxy as an experiment at being human.

References

Afolayan, A., Y.-H. Olajumoke, & T. Falola (eds.) 2018. Pentecostalism and politics in Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Allen, N.J. 2013. Durkheim's sacred/profane opposition: What are we to make of it? In Hausner, S.L. (ed.): Durkheim in dialogue: A centenary celebration of the elementary forms of religious life. New York: Berghahn. [ Links ]

Appiah, K.A. 2018. The lies that bind: Rethinking identity - creed, country, colour, class, culture. London: Profile Books Ltd. [ Links ]

Asamoah-Gyadu, K.J. 2013. Contemporary Pentecostal Christianity: Interpretations from an African context. Oxford: Regnum Books International. [ Links ]

Ateenyi, M.P. 2000. New religious movements in post-independent Uganda. PhD thesis, Department of Religious Studies, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. [ Links ]

Akugizibwe, J. 2012. Social impact of Owobusobozi Bisaka's religious movement on Nyoro culture: A case study of Muhorro sub-county, Kibaala district. BA dissertation, Department of Social Anthropology, Makerere University, Uganda. [ Links ]

Bainbridge, W.S. 1997. The sociology of religious movements. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bisaka, O. 1987. The book of God of the age of oneness: We are one in the Lord God of Hosts - Disunity has ended. Kapyemi: Faith of Unity Press. [ Links ]

Cesnur. 2000. Centrum for studies om new religions. Available at: https://www.cesnur.org/testi/uganda_004.htm. (Accessed on 28 February 2018. [ Links ])

Chidester, D. 2003. Salvation and suicide: Jim Jones, The Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Rev. ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Chidester, D. 2018. Religion: Material dynamics. Oaklands: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Cox, H. [1995] 2001. Fire from heaven: The rise of Pentecostal spirituality and the reshaping of religion in the twenty-first century. Cambridge: De Capo Press. [ Links ]

Doyle, S. 2000. Population decline and delayed recovery in Bunyoro, 18601960. Journal of African History 41, 3: 429-458. [ Links ]

Doyle, S. 2006. Crisis and decline in Bunyoro: Population and environment in Western Uganda, 1969-1955. Oxford: James Currey Publishers. [ Links ]

Drenen, T.S. 2013. Pentecostalism, globalisation, and Islam in Northern Cameroon: Megachurches in the making? Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Durkheim, E. [1912] 1995. The elementary forms of religious life. Fields, K.E. (trans. with an introduction). New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Echtler, M. 2015. Shembe is the way: The Nazareth Baptist Church in the religious field and in academic discourse. In Echtler, M. & A. Ukah (eds.): Bourdieu in Africa: Exploring the dynamics of religious fields. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Gaiya, M. 2015. Charismatic and Pentecostal social orientation in Nigeria. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 18, 3: 63-79. [ Links ]

Gornik, M.R. 2011. Word made global: Stories of African Christianity in New York city. Cambridge: William Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Heuser, A. (ed.) 2015. Pastures of plenty: Tracing religio-scapes of prosperity gospel in Africa and beyond. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Ilo, S.C. (ed.) 2018. Wealth, health, and hope in African Christian religion: The search for abundant life. New York: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Jacobsen, D. 2011. The world's Christians: Who they are, where they are, and how they got there. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Kaczyñski, G.J. 2012. Religious movements in Africa as expression of the sacred trauma: The explanatory approach reconsidered. Hemispheres: Studies on Cultures and Societies 27: 5-19. [ Links ]

Kassimir, R. 1991. Complex martyrs: Symbols of Catholic Church formation and political differentiation in Uganda. African Affairs 90, 360: 357-382. [ Links ]

Kiwanuka, M.S.M. 1968a. Bunyoro and the British: A reappraisal of the causes for the decline and fall of an African kingdom. The Journal of African History 9, 4: 603-619. [ Links ]

Kiwanuka, M.S.M. 1968b. The empire of Bunyoro Kitara: Myth or reality? Canadian Journal of African Studies/La Revue candaienne des études africaines 2, 1: 27-48. [ Links ]

Kusosha, I. & I. Musingusi 2018. Museveni hails Bisaka. New Vision (Kampala), 11 June 2018. Available at: https://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1479498/museveni-hails-bisaka. (Accessed on 30 November 2018. [ Links ])

Le Sage, A. 2011. Countering the Lord's resistance army in Central Africa. Strategic Forum 270: 1-16. DOI: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a546468.pdf [ Links ]

Lindhart, M. (ed.) 2015. Pentecostalism in Africa: Presence and impact of pneumatic Christianity in postcolonial societies. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Lofland, J. & R. Stark 1965. Becoming a world-saver: A theory of conversion to a deviant perspective. American Sociological Review 30, 6: 862-875. [ Links ]

Mugerwa, F. 2012. Owobusobozi Bisaka: The self-styled god in Bunyoro region. Daily Monitor, 12 May 2012. Available at: https://www.monitor.co.ug/SpecialReports/Owobusobozi-Bisaka--The-self-styled-god-in-Bunyoro-region/688342-1403840-jjbokk/. (Accessed on 28 November 2018. [ Links ])

N'Guessan, K. 2015. Côte d'Ivoire: Pentecostalism, politics, and performances of the past. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 18, 3: 80-100. [ Links ]

Ndyabahika, J.N. 1997. The attitude of the Anglican Church of Uganda to the new religious movements and in particular to the Bacwezi-Bashomi in South Western Uganda: 1960-1995. PhD thesis, Department of Religious Studies, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Rappaport, R.A. 1979. Ecology, meaning, and religion. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [ Links ]

Sithole, N. 2016. Isaiah Shembe's hymns and the sacred dance in Ibandla LamaNazaretha. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Sogolo, G. 1993. Foundations of African philosophy: A definitive analysis of conceptual issues in African thought. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press. [ Links ]

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2017. The national population and housing census 2014 - national analytic report. Kampala: The Government of Uganda Press. [ Links ]

Ukah, A. 2018. Emplacing God: The social worlds of miracle cities: Perspectives from Nigeria and Uganda. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 36, 3: 351-368. DOI: 10.1080/02589001.2018.1492094 [ Links ]

Unruh, D. 1980. The nature of social worlds. Sociological Perspectives 23, 3: 271-296. [ Links ]

Walliss, J. 2005. Making sense of the movement for the restoration of the Ten Commandments of God. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 9, 1: 46-66. [ Links ]

Wariboko, N. 2014. Nigerian Pentecostalism, Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press. [ Links ]

Westerlund, D. 2006. African indigenous religions and disease causation: From spiritual beings to living humans. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Wilkinson, M. (ed.) 2012. Global Pentecostal movements: Migration, mission, and public religion, Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Zurlo, G. & T. Johnson 2016. Religious demographies on African Christianity, 1970-2025. In Phiri, I.A., D. Werner, C. Kaunda & K. Owino (eds.): Anthology of African Christianity. Oxford: Regnum Books International. [ Links ]

1 John Modern, in the blurb of Chidester's latest book, Religion: Material dynamics (2018).

2 Two phases of ethnographic fieldwork in the FoU was done in 2016 and 2017 in Kampala, Kapyemi, Munteme, and Kihuuru - all in Uganda. The author acknowledges funding support from the John Templeton Foundation through Nagel Institute for the Study of World Christianity project on 'Religious Innovation and Competition: Their Impact in contemporary Africa', sub-project, 'Miracle Cities: The Economy of Prayer Camps and the Entrepreneurial Spirit of Religion in Africa' (ID: 2016-SS350). The author thanks Omukama Ruhanga Owobusobozi Bisaka for granting permission to research the FoU as well as Livingstone Akugizibwe, elder Tumuheire, and Dr Janice Desire Busingye for assisting during fieldwork in Uganda and with translation from Runyoro to English. Finally, thanks to the two anonymous reviewers of JSR for their comments and suggestions; the usual caveats hold.

3 Personal interview with Omukwenda Sabomu Walugembe, Kapyemi, Kagadi, Western Uganda, 12 September 2016.

4 In 1985, the original scripture was written and published in Runyoro, the ritual and official language of practice of the FoU.

5 According to the Vicar General of Hoima Catholic Church, Msgr. Mathias Nyakatura, representing the local and official Catholic opinion on Bisaka and his FoU, claims that Bisaka was after self-enrichment: 'He wanted money because he was not being paid well. He tricks people to get money, but we pray for him and his followers to repent'. If Bisaka 'was not being paid well', it was the fault of the Catholic Church that exploited him for his labor and underpaid him (Mugerwa 2012).

6 In Africa, religions, music, singing, drumming, and dancing act as an important prelude to a healer going into trance or possession and gaining access to the sacred. Through music the sacred is invoked or awakened, and a fresh revelation about the causes and remedies for specific illnesses is revealed. In the history of the AICs, we have many church founders who started off as composers of church music. Isaiah Shembe of Nazareth Baptist Church is one such leader (Echtler 2015; Sithole 2016; cf. Cox [1995] 2001:139).

7 The English translation is provided on 5 May 2018 by Dr Janice Desire Busingye, the DVC/AF, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda.

8 Personal interview with A. Livingstone, Kampala, 8 September 2016. Since the malaria diagnosis was not performed through clinical tests, it is safe to understand it as conforming with local, cultural knowledge and interpretation about illness conditions (Sogolo 1993:91-118; Westerlund 2006:165f).

9 Interview with senior elder of the FoU, 10 September 2016, Kapyemi, the HQ of FoU.

10 According to an informant, Bisaka possesses an enormous pharmacological knowledge and expertise which is often deployed clandestinely in healing people with protracted illnesses such as HIV positive people and those suffering from insanity. For these and similar cases of illness, herbal medicinal preparations are made and offered to them at a cost. They are instructed to keep both the source of medicine and the cost secret as a condition for their healing.

11 Although the FoU claims to be anti-Christian, it is more appropriate to argue that the Catholic Church is the liturgical and doctrinal palimpsest upon which Bisaka worked out his new religion.

12 Personal interview with Omukwenda Sabomu Walugembe, 11 September 2016, Faith of Unity Camp, Kapyemi.

13 Men are permitted to have as many wives as they can take care of. According to elders of the FoU, this practice is in accord with African tradition and it is also necessary to stem the consequences of prostitution. 'Restricting a man to marrying only one woman so that many women go without, is to encourage prostitution. This is because those who remain without have to roam about, looking for support. As a result of this promiscuity, many of them contract dangerous diseases some of which are difficult to cure. They may even transmit such diseases to the married ones if any one of them contacts them' (Bisaka 1987:arts 200, 201; original emphasis). As single ladies are not permitted to refuse marriage advances from men, according to female informants, the possibility of acquiring women as wives is a strong attraction of FoU to men.

14 Kneeling is also a sign of submission, the acknowledgement of another's worth and superiority and public humility. In this respect, Roy Rappaport (1979:199) maintains that '[fjormal postures and gestures may communicate something more, or communicate it better, than do the corresponding words. For instance, to kneel subordination, it is plausible to suggest, is not simply to state subordination, but to display it, and how may information concerning the state of a transmitter better be signalled than by displaying that state itself?'

15 Claiming to be ' indigenous' does not imply here that the FoU is part of the complex of African indigenous or traditional religion. It will be a categorical mistake to group the FoU with the Bunyoro indigenous religious culture, because this new religion is evidently opposed to and critical of indigenous religious ideas and practices, as their scripture recommends its followers to be aware of and avoid it. Members are meant to answer a list of 23 questions before every service. These questions deal with a renunciation of indigenous Bunyoro religious practices and ideas (Bisaka 1987:55-56).

16 The theory of sacral trauma explains the emergence of new religious movements in Africa as a response to individual and collective problems and conflicts demanding solutions, which are not offered by existing religio-cultural systems. Religious movements, such as FoU, are social movements responding to collective trauma caused by the disruption of the African worldview and its way of life by the violence of missionary religions (Christian and Islamic) and European imperialist and colonial interventions.

17 Ugandan lawmakers are proposing to formally designate the palace as a tourist attraction in order to draw visitors to the interior, thereby opening it for business.

18 Personal interview with Magezi. Even though members of the FoU deny any relationship with Christianity, it is important to note that the Vatican flag is a vertical bicolor of gold and white, with the red coat of arm imposed on the white portion of the flag. It is no accident that the liturgical reconstitution of the FoU is a hallowing out, a remaking and reinterpretation of Roman Catholicism.

19 Personal interview with senior elder, Tihumuwire Munteme, Hoima, 19 September 2016.

20 Personal interview with Omuhereza Byamukama, Kapyemi, 13 September 2016. ' Digging' is the euphemism for farm work.

21 Personal interview with Orac N. Kagadi, 23 September 2016.

22 The FoU is a politically active organization. Because of the presence and activities at the FoU HQ in Kapyemi, the Muhorro Town Council is now designated as 'Kihereza town' (or 'Local Council 1'), 'FoU believers' town', a new geopolitical entity recognizing the socio-political power of Owobusobozi and his followers. According to Bisaka, his organization and the political party in power in Uganda (the National Resistance Movement [NRM]) share the same objectives of bringing unity, development, and security to the people of the country (personal interview with Bisaka, 12 September 2016, Kapyemi). During Bisaka's eighty-ninth birthday celebration, the president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni hailed the religious leader for this vision and political alignment of his organization with the ruling party's National Resistance Movement's policies. Museveni's message read in part: ' Owobusobozi, we thank you for faithfully serving God for all the years. You have touched many people's lives and enabled many to come back to God. You have inspired many by your servanthood spirit.. .Owobusobozi, we wish you many years of happy returns and good health. Happy birthday celebrations'. The present was represented at the celebrations in Kapyemi by his Prime Minister, Dr Ruhakana Rugunda, who also presented Bisaka with presidential gifts of UGX10million (ca. US$2,690.00) (Kusosha & Musingusi 2018).

23 Bisaka conducts official ecclesiastical visits, called Orubung in Runyoro, to remote communities in Western Uganda. A typical Orubung lasts from late evening, say 7 pm, till the next morning, say about 5 am. During such visits, new converts are welcomed into the organization and the sick are brought from neighboring villages, and in some cases, hospitals and clinics, to be touched and healed by Bisaka (a fieldnote made on 19 September 2016).

24 The Book of God opens with the following declaration: 'THE GOOD NEWS OF THE LORD GOD OF HOSTS; WRITTEN BY OMUKAMA RUHANGA OWO-BUSOBOZI BISAKA ABOUT THE ITAMBIRO LY'OMUKAMA RUHANGA OWAMAHE GOONA ERY'OBUMU' (Bisaka 1987:7). This beginning is closely framed after Mark 1:1.