Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal for the Study of Religion

versão On-line ISSN 2413-3027

versão impressa ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.31 no.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n1a11

ETHICS FROM THE AFRICAN CONTEXT

Larry Kaufmann

Former Lecturer, Unilever Centre for Comparative and Applied Ethics, University of Natal (Now University of KwaZulu-Natal). larrykaufmann1954@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The main question of this article, 'Can Ethics be Taught?', is a critical reflection on the years I spent in association with Prozesky developing and presenting ethics training modules to a broad cross-section of professional and other groups. It describes the component parts of the workshops, comments on the rationale behind them, and also provides an analysis of both strengths and weaknesses. In a sense this is a critique of the discipline of Applied Ethics, yet at the same time it offers a possible pedagogy for what Prozesky and I would call 'ethics at the coalface'.

Keywords: ethics, ethics training, workshops, strengths, weaknesses, Applied Ethics, pedagogy, integrity, moral/ morality, integrity, authority, culture, religion, case study

The title of this article echoes a question Martin Prozesky and I would frequently hear when conducting ethics training workshops for a variety of groups across the country. Business ethics workshops would often include witty comments like 'isn't "business ethics" an oxymoron?' Humorous at best and cynical at worst, the questions nevertheless raise important concerns, not least the assumptions and prejudices we often bring to discussions on ethics, to say nothing of techniques and approaches to ethics training.

This article, recalling the happy years I spent in collaboration with Martin Prozesky developing and presenting ethics training modules to a cross section of professional and other groups, aims at a critical reflection on my work in developing a pedagogy for ethics training. Describing the component parts of a workshop which I designed, I comment on the rationale behind them, looking at both strengths and weaknesses. In a sense I am attempting a critique of my own praxis in the discipline of applied ethics and at the same time invite readers to engage critically with the model I present.

Let us begin by putting before us an image. The image is presented in a story told at the very start of the workshop in order to set the tone for the approach I normally followed.

Story

A wealthy and powerful Texan cattle rancher visited South Africa. He wanted to compare his cattle farming methods with those here.

His wanderings brought him to the vast open spaces of the Free State and the Karoo. But he got carried away one day about how things back home were 'the biggest and best in the world'. He boasted to the South African farmer: 'On my cattle ranch I have the largest herds of the largest cattle held in vast fields behind the largest fences and the largest gates in the world. But here in your country I see no fences or gates at all, only a couple of old wind-mills'.

The local farmer listened quietly and then responded with a smile: 'Ah yes, in your country you build big fences to keep your cattle in. Here in Africa we dig deep wells. And where there's good water, cattle don't stray far away'.

This little story contains in essence much of what I want to develop in the presentation. It lays emphasis not on laws and regulations (the fences that keep people and systems 'in'), but on deep sources that nourish the mind. For me true ethical imagination and all ethics training must lead to 'deep wells'. In sourcing that well (pun intended) several steps are followed. For the sake of preliminary overview these steps are:

-

Reading the moral barometer;

-

Drawing a personal moral map;

-

Models of integrity;

-

Appeal to authoritative sources;

-

The contribution of culture;

-

The contribution of religions; and

-

Case study.

Reading the Moral Barometer

In any interactive workshop or seminar, after introductions and what is termed 'appropriate self-disclosure' (more about that later), it is vital in my opinion to get participants to be participant as soon as possible. It sends the signal that this will not be a long boring day of listening to lectures. It taps in immediately to collective wisdom and energy. And it also reveals differences of interpretation and perhaps even a few prejudices and stereotypes.

The workshop would begin by trying to establish the level of ethical awareness and practice in the relevant organisation using the image of a barometer, which I would project on an overhead slide or power-point. Explaining that I sought the group's own analysis of ethos, the culture of ethics (or lack thereof) in its organisation or group, I would also ask that this analysis be situated within a broad national and indeed global context. One may recall here the maxim, 'think globally, act locally'. It is not enough to simply point fingers at the boss or the company without acknowledging the influence of the national and even the global ethical climate. A barometer is about the weather, changeable as it always is, but using the criterion of measuring atmospheric pressure. Participants would enjoy identifying the high pressures and low pressures of the organisation, and from that estimate the general ethical atmosphere of their workplace.

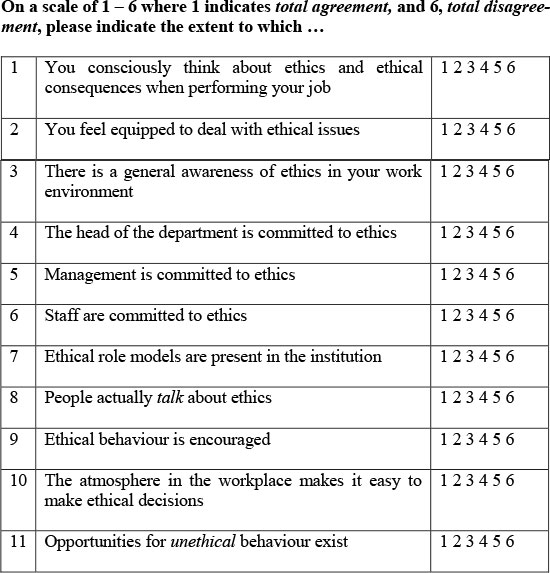

Sometimes complementary to this exercise and in later years replacing it, I adapted to local circumstances a questionnaire found in Deon Rossouw's Business Ethics (2004). Participants would fill in the questionnaire as quickly as possible (to capture their knee-jerk responses), share their answers with a neighbour, and then we would collate all the scores and work out an aggregate assessment which then became the basis of general discussion. I reproduce the questionnaire here:

Drawing a Personal Moral Map

Martin Prozesky would be the first person to agree that attention to conscience is absolutely necessary in the pursuit of ethical wisdom. As he defines it, 'Conscience is the inner voice of ethics, of right and wrong, of good and evil. We can think of it as our built-in guidance system in the search for the good life' (2007:19).

For this next step in the applied ethics workshop, I tried to elicit in participants an examination of the events, situations and personal circumstances that had influenced and shaped their consciences, their moral awareness and transformation. Each of us has a story. So the exercise establishes plurality and diversity as well as commonalities within the group.

As the SANCODE puts it:

Ethical behaviour builds on core moral values while respecting cultural diversity …. Ethics is about personal and individual ethical judgement …. We regard the moral development of the individual through processes initiated in our homes, in religious settings, and through education and cultural upbringing as essential to moral behaviour in the workplace.

One of my personal ethical principles is never to expect of others what I am not prepared to do myself. This is what I mean by 'appropriate self-disclosure'. I would start the ball rolling with a personal anecdote.

As a young boy growing up in the 1950s and '60s in the capital of apartheid ideology - in Pretoria - I was exposed at an early age to the pain and inhumanity of racism. We were at the dinner table and 'the girl' (it is necessary for the sake of this narrative that I retain the racist terminology of the time) came in to inform us that 'a boy' (note her own use of the terminology!) was at the kitchen door looking for my father. My dad went through, while, peeping through the kitchen latch, the rest of us watched and eavesdropped. There was a black gentleman, well-dressed in suit and tie. He introduced himself as Doctor Fabian Ribeiro whose priest had referred him to a 'sympathetic' attorney (my dad). I will never forget my father's response: 'Would you do me the honour of coming in my front door?' at which he led Dr Ribeiro round the house and in through the front door to the lounge. In time Dr Ribeiro and his wife Florence became close friends of ours. One day Fabian came to the house, agitated and upset. He explained how he had come across a motor accident with people bleeding on the side of the road. He got out to assist, explaining that he was a doctor. But suddenly he found himself punched all over the face and sworn at (in words that those of us who lived through that era will no doubt remember). His comment is something that has stayed with me my whole life: 'Is a white life not worth being saved by a black doctor's hand?'

I would tell this story to highlight how personal experience contains within it elements of the learning curve, or the development of conscience. The wonder of the narrative model is that it always encourages reciprocity. In no time others are telling their stories!

This exercise is eminently related to my opening story about fences and wells, namely, that ethics is about tapping into sources before it's ever about putting up fences. In this instance, what exactly are we tapping into? By telling their stories, participants are sourcing some of the values and principles that make us fully human; that enable us to answer with ever greater maturity the question: Who am I?

The question, 'Who am I?' is fundamentally an ethical question. It raises deep issues about what it means to be moral, how we can develop the kind of self that makes ethical choices and what human values we want to live by; or perhaps fail to choose and allow ourselves to be pushed, without respect for freedom and responsibility, without respect for conscience, in the direction that others want us to go, with negative consequences. The opposite can of course be equally true: not to be pushed by parents and teachers but liberated by them because of their mature approach to the formation of the young.

Thus in answer to the question, 'Who am I?' - while I can say truthfully that I am someone's son or daughter, someone's cousin or uncle, someone's niece or nephew, a citizen of this or that city, a member of this or that guild or profession, I can also say, in virtue of personal integrity and the development of conscience, that I am my own person. One thinks of the wisdom of the Jewish mystic, Susha, who is reported to have said: 'When I die, God is not going to ask me, why were you not Moses, why were you not Isaiah, but, why were you not Susha?'

The journey to becoming an ethical person flourishes with one's own embodiment of consciously chosen positive values. This step of the workshop aimed at facilitating expression of this.

Models of Integrity

Lest the above exercise degenerate into a celebration of narcissism it is quickly complemented with an examination of recognised models of integrity, whether historical or contemporary. What I specifically ask participants here to do is draw out the experiences of suffering, adversity and challenge that have helped shape the integrity found in one prominent individual. Nelson Mandela would come readily to mind for most, but I would immediately suggest that they choose someone with whom they are more familiar, either personally (often a parent was chosen) or through reading or study.

Sharing the stories would lead naturally to the emergence of a kind of narrative 'collage' of the characteristics of integrity. The advantage of this is to see ethics pertaining to human beings per se - to people of flesh and blood - and not simply to a study of academic theories, as important as they may be but always as secondary to lived experience.

In affirming this step on the journey towards a greater appreciation of ethics, I wonder if the African respect for ancestors can also teach us something here? This respect has been described somewhere as 'solidarity in memory'. In the solidarity between the dead and the living, those who remain behind remember among their ancestors both those who were victims of suffering and oppression as well as those whose lives were lived in relative peace yet who worked tirelessly to ensure the best future for later generations. Their collective lifetime experiences are passed on as wisdom to their offspring. In Africa it is precisely in this solidarity in memory with the ancestors that moral norms can be found.

But remembering for edification is not limited to the dead. Those who are still alive are also included in this remembering, especially if they have helped to shape the present in which we now continue to live and work. Elderly people can be fonts of wisdom and moral integrity.

It is in recounting the lives and stories of the living and the dead that we are able to drink from the deep well of moral integrity. It is important to keep the stories of saints, heroes and prophets alive if we are to construct a moral regeneration appropriate to our present reality. The Letter to the Hebrews in the Christian Scriptures states: 'With such a cloud of witnesses on all sides around us, we should never let go of the hope that we have' (Heb. 12:1)

Since by this stage of the workshop it has been established that ethics pertains primary to the personal - both in autobiography and biography - it is now appropriate to explore written and other authoritative sources which are also helpful for building up a culture and a climate of ethical goodness. Person before systems. Yet words of wisdom have their authoritative place.

Appeal to Authoritative Sources

This subtitle may suggest that we're now going to start building ethical fences. On the contrary, the image of the windmill and the well remains in place. The operative word in this subsection's title is still 'sources'. The first written source I would present to participants is the South African Constitution. However, I would immediately add an important qualification: the source of its ethical contribution is not in the letter but in the process, i.e. the origin and spirit of the Constitution.

There is an old story told of a couple of tourists travelling through Ireland. They got lost along the road, and stopped to ask a farmer for directions. He responded: 'Well if I were you I wouldn't start from here!' We can appreciate the humour. We know very well that as human beings we can only start from where we are.

The exercise of examining and drawing on the South African Constitution would be to consider its own starting point. We need to remember its origins. We need to remember what problems and aspirations the Constitution sought to address, and what vision it encapsulates for our society. In short, what are the values and norms encapsulated in the Constitution which our society cherishes and intends to uphold?

The operative word is 'intends'. Intention is one of the key ingredients in any ethical discourse. We retrace our historical steps from the birth of our new democracy, back to the efforts to bring about a peaceful solution to that struggle, back again to the suffering endured by millions in the struggle against apartheid. This is what we mean by the starting point of the Constitution, by its original intent. Not the long hours which lawyers and writers put into drafting the wording of it, but the living witness and stories of countless South Africans who wrote the Constitution with their tears, their sweat, their blood, and their good will. In this sense the Constitution is for us a 'source' for ethical reflection. Its personal dynamic is perhaps best captured in the immortal words of Mandela at his inauguration as president in 1994:

Out of the experience of an extraordinary human disaster that lasted too long, must be born a society of which all humanity will be proud. Our daily deeds as ordinary South Africans must produce an actual South African reality that will reinforce humanity's belief in justice, strengthen its confidence in the nobility of the human soul and sustain all our hopes for a glorious life for all.

The 'Preamble' to our Constitution is clear in its affirmation of moral values: justice, honour, respect, unity in diversity, healing, improvement of quality of life. To quote a few lines:

We ...

… honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land;

… respect those who have worked to build and develop our country;

… believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.

The first chapter of the Constitution is founded on the following values (italics my own):

-

Human dignity, equality, advancement of rights and freedoms;

-

Non-racialism and non-sexism;

-

Supremacy of the Constitution and the rule of law; and

-

A system of democratic government to ensure accountability, responsiveness and openness.

Ethics is all about values, and, for the social beings that we are, it is about shared values. What else is our national South African Constitution, but the gathering together of a vast array of ideals, values, hopes and dreams of all the people of this country?

One could describe this gathering together of values and ideals in terms of 'the common good'. By definition 'the common good' is the shared values or goods of a political association. Philosophers describe common good as the sum-total of those conditions of social living, whereby human beings are enabled more fully and more readily to achieve their full potential.

As a guide, the notion of the common good helps us to discern the concerns of our society, from environmental problems to the social make-up that is necessary to sustain our communities. The ongoing challenge within South Africa, in response to the diverse needs of all her people, is related to an understanding of the common good. One of the problems is to find values held in common by conflicting parties. I have suggested in this section that the shared desires expressed in our Constitution are a valuable starting point, precisely because that starting point itself has deep foundations. It is a nourishing well from which we may drink.

The ethical spirit of the Constitution is captured well by Martin Prozesky when he says that our Constitution engages in 'a renewed, shared quest for greater well-being, based on a renewed conscience, [and] a renewed ethic that is effective' (2007:30).

By way of concluding this section, admittedly I have only used the Constitution as an example of an authoritative source. However, my principal interest in developing the above reflections has been method rather than content. Recall my affirmation of 'original intent'. In the methodology that I propose the primary focus is not on raw text but rather on extrapolating the personal and social dynamic contained within the words of the chosen authoritative source. The same approach thus applied when the workshop drew on other texts such as the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights; the King Report on Corporate Governance; the SA Moral Regeneration Movement's Charter of Positive Values; the SANCODE and other ethics codes or vision statements. Unless texts deemed authoritative for good ethics are seen to be written in 'blood, sweat and tears', they will not be worth the paper they are printed on.

There are other wells wherein to source good ethical values: culture and religion. To these we now turn.

Culture

Martin Prozesky refers briefly in his book, Conscience, to the role played by culture in shaping conscience and ethical behaviour, yet he is quick to point out the ambiguities of culture. I agree with him. In my earlier workshops I was probably rather naïve and idealistic in my attitude to culture and its place as a source of ethical wisdom. In particular, post-1994, I had unwittingly romanticised 'African culture' in the belief that a return to its more ancient roots would suddenly produce a new moral society. So, for example, I would promote concepts like 'ubuntu' and 'seriti' which, while remaining valuable sources, I had undoubtedly treated superficially.

This is not to denigrate the crucial contribution of anthropology to ethics. I still want to affirm the historical roots of culture, but for me now there are certain 'riders' to which I will return in due course. But first, a brief journey into the importance of culture in doing ethics in an African context.

If ethics in general is about the strengthening, growth and well-being of life, then in Africa moral action is about the growth of life of the whole community. Where for instance a Western approach may be considered 'conceptual' in Africa it is probably more 'consensual' - striving for consensus. Thus, for example, traditionally the first responsibility of community leaders is to guard the common welfare and to promote the growth of life. But the ethical community in Africa is not restricted to the earthly community. It also includes the invisible world of the living-dead. As Bénézet Bujo states:

The ancestors play an important role in shaping morality. Their task is not exhausted through passing on (physical) life which they did in their earthly existence. They are still responsible that their offspring remain brave and strong. In addition, the ancestors have set up moral directives for the welfare of their children. These directives reflect the ancestors' experience; they give wisdom and life (1998).

At stake here is the importance of the communal dimension common to all African cultures as a vital source for morality. The human and social sciences have clearly indicated the role that our entire social context plays in the formation of our moral principles and behaviour. All of us owe some allegiance to various groups within our society and this in turn helps to shape moral values - for better or for worse. The praxis of ethics is to focus on the 'for better' part of that statement! The question before us, quite simply, is how the very best of culture and cultures can enhance and regenerate moral values in our society. This step of the workshop aimed to affirm that.

I stated earlier, however, that there were riders to this. Indeed, in this regard I find inspiration in the pastoral exhortation of Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), a document in which the pope shows a remarkably balanced approach to culture, affirming it yet at the same time pointing out its shortcomings. For example, the pope draws attention to the culture of individualism which not only permeates Western countries but which, thanks to modern media and entertainment, has reached even to most remote areas of other continents. From his own perspective on the 'prevailing culture', Pope Francis sees that 'priority is given to the outwards, the immediate, the visible, the quick, the superficial and the provisional. What is real gives way to appearances'. Tragically, he says, this often marks a hastened deterioration of people's cultural roots adding the disturbing words: '… and the invasion of ways of thinking and acting proper to other cultures which are economically advanced but ethically debilitated' (e.a.).

Pope Francis points to Africa as an example, re-affirming his predecessor John Paul II's lament about attempts to make the African countries 'parts of a machine, cogs in a gigantic wheel', without any 'respect [for] their cultural make-up' (1995:52).

Pope Francis adds another dimension: the loss of a sense of the transcendent, which for him 'has produced a growing deterioration of ethics' and 'a general sense of disorientation' (EG 64). Significantly, the pope does not suggest that the 'transcendent' to which he refers must necessarily be the God of Christianity. Indeed, he has shown through his gestures a profound respect for people of other faiths or no faith at all. At his first gathering with journalists, for example, instead of the traditional opening prayer he suggested that they all keep a moment of silence, acknowledging that some may not only not be Christians like himself but may in fact be without any faith.

But let us return to his reflections in Evangelii Gaudium. He says something which in my view is eminently pertinent to the principal concern of this article.

We are living in an information-driven society which bombards us indiscriminately with data - all treated as being of equal importance - and which leads to remarkable superficiality in the area of moral discernment. In response we need to provide an education which teaches critical thinking and encourages the development of mature moral values (EG 64 - e.a.).

Apart from the influence of media and entertainment on the development of a corresponding global culture, Pope Francis also refers to the role of the modern metropolis city, where in their daily lives people must often struggle for survival. 'New cultures are constantly being born in these vast new expanses …. A completely new culture has come to life and continues to grow in the cities' (EG 73).

Francis does not exclude the rural areas, as I have already pointed out, stating in the same paragraph that these too 'are being affected by the same cultural changes, which are significantly altering their way of life as well' (EG 73).

If I may use one of my favourite expressions again: the operative word. In the paragraph above it is 'changes'. It is operative because it indicates the exact issue that has challenged me out of my idealising of culture in relation to ethics. No longer do I simply see culture in a romantic way as fixed and as a perennial source of ethics. It is something that is forever changing and today globally. Perhaps we need to draw on a bit of evolutionary theory here. How is culture changing? Where is it changing? Into what is it changing? I have suggested that Pope Francis has provided some useful guidelines. Earlier on I suggested that culture is a source of ethics. I now submit the need to acknowledge that culture is in turmoil and in our times is increasingly marked by individualism and superficiality. Yet understood in a differentiated way it remains a necessary source for ethics.

Religion

On the question of religion and its potential as a source of ethics I defer to my mentor, Martin Prozesky. He has made a profound contribution on the role of religions in human history to the discussion of ethics, insisting always on including the term 'comparative' - as he did even in the name of the ethics centre he established at UKZN ('The Unilever Centre for Comparative and Applied Ethics'). Martin has contributed enormously to the value of comparative religion in ethics. But he also notes ambiguities and paradoxes. In his book Conscience he has two sub-sections, one entitled Religion: Blessing and Curse (2007:27) and one entitled The Value and Limits of Religious Motivations (ibid. 67).

Religion in the broadest sense has undoubtedly played a vital role in the development of ethics and spirituality. This is not to deny its potential, through abuse, for fomenting conflict and division as well as apathy. A perfectly valid question often raised by critics of religion is the following: 'Do we have to be religious to be moral?' Or framed another way: 'Do we have to believe in God to be good?' It is sometimes argued that ethics precedes faith. Human beings, for millennia before they came to any form of belief in a divine being and authority, of necessity had to find ways and means of getting on with each other, of establishing the 'ground rules' of social living. In the history of humanity, religion is a relatively recent phenomenon. Social mores existed long before its advent.

Now I'm not trying to put myself out of a job. (I am after all a Catholic priest!). I am merely trying to put the question of religion in proper perspective in relation to ethics. Morality is not and can never be the exclusive prerogative of the religions - the churches, the temples, the synagogues or the mosques. Morality belongs to society as a whole. It belongs to humanity as a whole. I want to suggest that the role religion plays is that of 'midwife' - bringing to birth and nourishing moral norms and values rooted in the human heart.

Take South Africa as a small example. Gone are the days when one branch of Christianity - a certain limited Calvinist interpretation - imposed itself through legislation and other ways on the majority of the people, whether it had to do with allowing us to have television (banned until 1976) or fishing on a Sunday. Instead, our Constitution celebrates religious pluralism and diversity. We now have the possibility of mutual enrichment and open dialogue.

A clear example of this was seen at the 'Morals Summit' in November of 1999, a national event that brought together politicians and religious leaders in South Africa for commitment to a common code of conduct in religious and political leadership. On that occasion the head of the Jewish community, the late Chief Rabbi Harris, remarked that to his knowledge nowhere else in the world had it be known for religious and political leaders together to meet in such shared commitment to promoting the common good of our society. The advantages of the public witness of religious leaders in dialogue with each other cannot be overestimated.

A final word on the potential role of religion. Mahatma Ghandi, a Hindu, could comfortably quote from scriptures other than his own. It is told that on one occasion, during his travels by train around India prior to independence, he was met at a station by a vast crowd waiting for a word of encouragement from him. He took out his pocket edition of the Christian gospels and read the Beatitudes from the sermon on the mount of Jesus Christ. Afterwards he exclaimed: 'That is all I have to say'.

Case Study

I am a firm proponent of the case method in applied ethics. It certainly gets energy levels up in group work, but it also serves the important task of relating theory to real life situations. I was introduced to the case method by Robert (Bob) Evans who has written a book on it. I still have my notes from his workshops and draw on them now. For Evans, case studies are one way to capture past occurrences with a view to assist in resolving present ethical dilemmas and choices.

Ethical decisions are made on a number of levels. Individuals follow gut-level intuitions and muddle through situations reactively. This is fine if the individual is caring and the situation is uncomplicated. Mostly, however, making ethical choices is both difficult and complex. There are often conflicting facts. There is the difficulty of abstract reasoning. Application of relevant norms is tricky. Intersecting problems and relationships are noticed. There are always exceptions to the rule. Most challenging of all is the complexity of human relationships!

Case study can help provide some critical distance. As Bob Evans would say, cases help sort out the choices and give the opportunity to move down the path from the identification of norms through the maze of intersecting

facts and exceptions to the selection of the best alternative.

In my workshops I would always provide a broad selection of cases. But the following one always provoked the most discussion and debate:

A Nazi Gestapo officer during World War II approaches the Mother Superior of a convent orphanage and asks her if there are any Jews among the 400 or so orphans (there are in fact dozens of Jewish children among them). She says 'No'. Is she lying?

To my consternation some participants would say that she was wrong to lie, that lying is unethical in all circumstances. Never mind that those Jewish children would be captured and sent to their deaths! However, most participants would argue that the value of human life is higher than simply telling the truth to a man representing an evil system. In ethics one must often choose the greater good (protecting life) over the lesser good (in this case telling the truth). To my delight, however, some participants saw hidden nuances in the case. In the ethical imagination, nuance is often very important. They argued (from the notion of intention) that de facto the Gestapo officer was asking: Do you have any Jewish orphans for execution? She replied truthfully by saying, 'No (I don't have any Jewish children for your gas chambers)'.

How important are the parentheses! They provide the key to interpreting the case. Using this as a model, the participants would then examine other cases and even present cases of their own.

Conclusion

Keeping to the title of this paper the question remains: Can ethics be taught? What I have shared from my experience conducting ethics workshops is, I suppose, an affirmation that indeed it can. However, I leave the final word to Martin Prozesky. Not only have I been inspired by his passion for ethics, and his passionate teaching of ethics (which means that for him, ethics can indeed be taught). I also see in him a model of integrity that speaks louder than words. The Epilogue to his book Conscience is more than simply Martin's academic condensation of the values which he believes will give rise to greater global flourishing. I submit that it captures Martin Prozesky's embodiment, in his own person, of the very things he proposes:

-

Be actively concerned for the well-being of all whom you affect;

-

Resist the pull of selfish desire;

-

Care especially for the weak, the poor, the vulnerable, and the innocent;

-

Live honestly, respectfully, justly, and with integrity;

-

Seek always to understand;

-

Enfold sexuality with love, faithfulness, responsibility, and respect;

-

Use freedom kindly;

-

Protect the earth and all living things;

-

Add beauty to the world; and

-

Live as friends.

References

Comment:

The references that follow have been consulted mainly in terms of their respective approaches to comparative and applied ethics. My article, I readily concede, has not attempted to engage with pressing ethical issues, be they economics, sexuality and gender, medical ethics, environmental concerns, politics and other topics. My primary focus has been foundational ethics, and, in this paper a methodology for a pedagogy of ethics.

Appelbaum, D. & S. Lawton 1989. Ethics and the Professions. London: Pearson College Div. [ Links ]

Brown, M.T. 1999. The Ethical Process: An Approach to Controversial Issues. 2nd Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Bujo, B. 1998. The Ethical Dimension of Community: The African Model and the Dialogue between North and South. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. [ Links ]

Callahan, D. & P. Singer (eds.). 2012. Encyclopaedia of Applied Ethics. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Connors, R. & P. McCormick 1998. Character, Choices and Community. Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press. [ Links ]

Mackey, J.P. (ed.) 1969. Morals, Law and Authority. Dublin: Gill & MacMillan. [ Links ]

McCabe, H. 2005. The Good Life. London & New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

McCormick, R. 1989. The Critical Calling. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. [ Links ]

Pope Francis 2014. Evangelii Gaudium. Given in Rome, at Saint Peter's, on 24 November 2013. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available at: https://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html [ Links ]

Pope John Paul II 1995. Ecclesia in Africa. Given at Yaoundé, in Cameroon, on 14 September 1995. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available at: http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_14091995_ecclesia-in-africa.html [ Links ]

Prozesky, M. 2003. Frontiers of Conscience: Exploring Ethics in a New Millennium. Cascades: Equinym Publishing. [ Links ]

Prozesky, M. 2007. Conscience: Ethical Intelligence for Global Well-Being. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press. [ Links ]

Rossouw, D. 2004. Business Ethics: A Southern African Perspective. 3rd Edition. Cape Town: OUP, Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Stivers, R. (with Christine Gudorf and Alice Evans and Robert Evans, eds.) 1995. Christian Ethics: A Case Method Approach. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Villa-Vicencio, C. & J.W. de Gruchy (eds.) 1994. Doing Ethics in Context: South African Perspectives. Claremont: David Philip. [ Links ]