Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.29 n.2 Pretoria 2016

ARTICLES

Reflecting on a Decade of Religion Studies Implementation in the FET Phase: Case Study of Gauteng, South Africa1

Johannes A. SmitI; Denzil ChettyII

ISchool of Religion, Philosophy and Classics College of Humanities University of KwaZulu-Natal smitj@ukzn.ac.za

IIDepartment of Religious Studies & Arabic College of Human Sciences University of South Africa chettd@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Post-Apartheid South Africa witnessed a major shift from Christian National Education to a multi-religion educational approach that sought to treat all religions within an impartial academic context. The National Policy on Religion Education (2003) provided the framework in which the objectives of a multi-religion education found its expression in Life Orientation (Grades R-12) and more fully in the Further Education and Training (FET) Phase with Religion Studies as a subject for Grades 10-12. Through this curriculum transformation, the State aimed to conscientize students to the religious diversity and topical issues within the country, and thereby contribute to the transformation of civil society leading to the materialization of ideal citizens within a democratic society. A decade later while Religion Studies has found a familiar footing among students nationally (i.e. with an increase in student participation in the National Senior Certificate Examinations), concerns on the implementation of the subject are being raised by the Department of Basic Education. Based on a collaborative research initiative with the Gauteng Department of Basic Education (GDBE), this paper aims to explore the challenges confronting educators with the implementation of Religion Studies.

Drawing on a cross-sectional survey using questionnaires as a data collection method, this paper analyses the responses of 19 participants (n = 19), comprising Religion Studies educators and Subject Advisors in Gauteng Province. The paper concludes with the following findings: (1) a notable lack of qualifications and experience; (2) a gap in conceptual clarity of the subject; (3) a lack of adequate content and teaching materials; (4) the absence of critical pedagogical, assessment and moderation skills; (5) need for career advocacy; (6) need for national support; and (7) the need for professional development.

Keywords: Religion Studies, curriculum transformation, implementation challenges, pedagogy skills, assessment and moderation, religious literacy

Introduction

During the Apartheid regime the South African government had implemented a compulsory non-examinable Bible Education in schools for all students from Grades 1-12. In addition, Biblical Studies was offered as an examinable elective (similar to history, geography, accounting, etc.) for Grades 10-12. The curriculum and 'dogma' of these subjects were determined by the Dutch Reformed Church and Christian National Education (cf. Louw 2014: 175). The positioning of Bible Education and Biblical Studies within Bantu Education2served an ideological purpose, in which it further perpetuated the cultural hegemony of the Apartheid Government by spawning citizens who could be culturally and politically controlled. Transformation in post-Apartheid South Africa saw the then Minister of Education, Kader Asmal announce the enactment of the National Policy on Religion and Education (2003) as approved by the Council of Education Ministers3. The application of the policy paved the way for (1) the teaching of Religion Education in Life Orientation (Grades R-12), and (2) the introduction of a new examinable subject called Religion Studies (Grades 10-12) (cf. Religion and Education Policy 2003: 14).

The end of the year 2015 marked a decade since the implementation of Religion Studies in the FET phase (Grades 10-12). Since its inception in 2006 (Grade 10), with the first cohort of Grade 12 writing the Religion Studies National Senior Certificate (NSC) Examination in 2008, the subject has found a familiar footing among students nationally. In 2008, the number of students participating in the first Religion Studies NSC Examination was 1 471 (cf. Molete 2010). The following year indicated potential for the subject when student numbers increased by 399 with a total of 1 870 students (cf. ibid.). Over the next five years (cf. Graph 1 below), there was a remarkable growth in student numbers. In 2010, a total of 2 279 students participated in the Religion Studies NSC Examinations; 2011 saw an increase by 942 students, with a total of 3 221 students; 2012 saw a further increase to 4 212 students; 2013 increased by 1 002 students with a total of 5 214; and in 2014, the student numbers increased to 5 802 (cf. Mweli 2015). 2015 saw the largest increase of 1 235 students with a total of 7 037 students participating in the Religion Studies NSC Examination (cf. Perumal 2016). An overall analysis reveals a notable growth of 5 566 students over an eight year period, and a total of 31 106 students participating in the Religion Studies NSC Examinations from 20082015.

In addition to the remarkable growth of student participation in the Religion Studies NSC Examination, which indicates 'market' potential for the subject, the national pass rate over the past decade has been averaging above 80%. In the first cohort of Grade 12s in 2008, the national pass rate was 87.3%, with 86.3% in 2009 (cf. Molete 2010). The past four years (2012-2015), according to the 2015 National Senior Certificate Report, saw the pass rate in Religion Studies averaging 90% and above (cf. Department of Basic Education 2015: 59).

While the notable increase in student numbers and the equally inspiring pass rates in the Religion Studies NSC Examination over the past decade offers much potential for the subject, there is an emerging anomaly with the implementation of Religion Studies. In reporting on the 2008-2009 NSC results in Religion Studies Molete (2010: 5) noted three major challenges. Firstly, there was a need for Subject Advisor and educator training, secondly, a need for ongoing monitoring and support; and thirdly, the need to develop quality assessment tasks and tools. This is further enhanced by the independent observations of Smit and Chetty (2009: 347-350), which affirmed that problems with the implementation of Religion Studies both provincially and nationally in 2008 and 2009 could be attributed to conceptual problems between Biblical Studies and Religion Studies; the nature of the Religion Studies educator; challenges with assessing the critical competencies in Religion Studies; and identification of potential career paths (cf. ibid.). In reviewing the Religion Studies NSC results from 2010-2014, Mweli (2015: 20) noted three major concerns: (1) few qualified teachers; (2) the textbook is inadequate and does not meet the needs of the learners to prepare them for NSC Examination; and (3) educators focus on few religions in which they have knowledge as opposed to the full curriculum. In reporting on the 2015 NSC pass rates in Religion Studies, Perumal (2016) further noted critical challenges with the assessment of Religion Studies in the NSC Examinations, and the nonexistence of School-Based Assessment (SBA) tasks and assessment rubrics.

The above inconsistencies stemming from the implementation of Religion Studies poses critical challenges for the future of the subject. While increasing student numbers and high pass rates create the facade of a stable implementation, the reoccurring concerns articulated by the Department of Basic Education in national reports indicate that the implementation of Religion Studies in the FET phase is problematic. It is against this background, that this paper aims to explore the challenges confronting educators with the implementation of Religion Studies in the FET phase. In order to achieve this, this paper employs a cross-sectional survey using Gauteng Province as a case study.

Key Concepts

The National Policy on Religion Education (2003) makes a clear distinction between 'Religion Education' and 'Religious Instruction'. Religion Education is defined as a 'curricular programme, with clear and age appropriate educational aims and objectives for teaching and learning about religion, religions, and religious diversity in South Africa and the world', with emphasis on 'values and moral education' for the 'purposes of achieving religious literacy' (cf. Department of Basic Education 2003: 9). The policy further cautions on the use of this space for the propagation of confessional or sectarian forms of religious instruction in public schools, which is deemed 'inappropriate for a religiously diverse and democratic society' (cf. ibid.). Religious Instruction is defined as including 'instruction in a particular faith or belief, with a view to the inculcation of adherence to that faith or belief, which ' is primarily the responsibility of the home, the family, and the religious community' (cf. ibid.: 20). While the policy encourages religious instruction, it cautions that ' the provision of religious instruction by religious bodies and other accredited groups must occur ' outside the formal school curriculum .

The concept 'Religion Studies' as employed in this paper, refers to the subject offered in the FET Phase (Grades 10-12). The Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) for Religion Studies sets the context for the subject by defining its parameters as the study of ' a universal human phenomenon and of religions found in a variety of cultures , where ' religion and religions are studied without favouring and/ or discriminating against any, whether in theory or in practice, and without promoting adherence to any particular religion' (cf. Department of Basic Education 2011: 8). The CAPS document further articulates Religion Studies as leading to the ' recognition, understanding and appreciation of a variety of religions within a common humanity , which culminates with ' a civic understanding of religion and with a view to developing religious literacy' (cf. ibid.). The subject comprises four topics, namely, (1) variety of religions; (2) common features of religion as a generic and unique phenomenon; (3) topical issues in society; and (4) research into and across religions. The subject aims to enhance the constitutional values of citizenship; develop the learner holistically; enhance knowledge through the understanding of a variety of religions and how they relate to one another; and to equip the learner with the necessary skills for research into religion and across religions (cf. ibid.).

An understanding of these key concepts, provides a basis for unpacking the challenges emerging with the implementation of Religion Studies in the FET Phase.

Contextualizing the Case Study

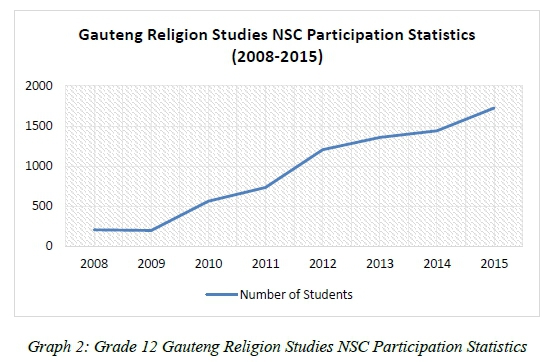

In reflecting on a decade of Religion Studies implementation in the FET phase, Gauteng Province offers an insightful case study with a steady growth of student participations in the Religion Studies NSC examination (cf. Graph 2 below). In terms of national statistics, Gauteng Province has seen the second highest number of student participations, with Mpumalanga Province maintaining the highest student participation numbers over the past decade (cf. Molete 2010; Mweli 2015; Perumal 2016).

In 2008 the number of students participating in the first cohort of the Religion Studies NSC examination was 205, this was followed by 196 students in 2009 (cf. Molete 2010). In 2010 the number of students increased to 562, with 733 students in 2011, 1 205 students in 2012, 1 358 students in 2013, and 1 439 students in 2014 (cf. Mweli 2015). In 2015, the total number of students writing the Religion Studies NSC examinations was the highest in the past decade with 1 7244 (cf. Perumal 2016). The total number of students participating in the Religion Studies NSC examinations over the past eight years in Gauteng Province is 7 422, with a provincial growth of 1 519 students from 2008 to 2015.

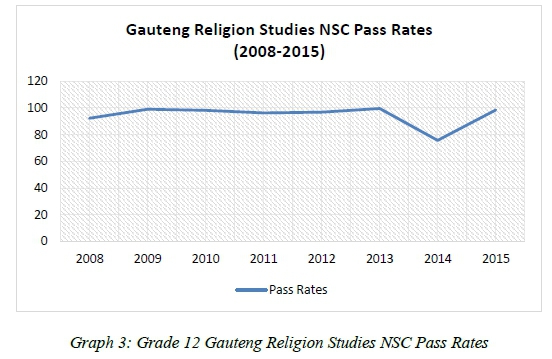

In terms of the pass rate in the Religion Studies NSC Examination, Gauteng Province has maintained a remarkable pass rate averaging above 90% with an exception of 2014 (cf. Graph 3), making it the province with the highest pass rates. In the first Religion Studies NSC examination in 2008, Gauteng Province achieved a 92.23% pass rate, followed by a 98.98% in 2009 (cf. Molete 2010). The following years (as illustrated in Graph 3) saw a relatively stable pass rate, with 98.22% in 2010, 96.32% in 2011, 96.76% in 2012, and 99.56% in 2013 (cf. Mweli 2015). However, in 2014 the provincial pass rate dropped to 75.7% (cf. ibid.). This drop in provincial pass rate can be attributed to the change in the national education system, which saw a shift from Outcomes Based Education (OBE) to the new Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), which was implemented for the first time in 2014 in Grade 125. However, in 2015 despite the increase in student numbers participating in the Religion Studies NSC Examination (as compared to previous years), Gauteng Province achieved a 98.49% pass rate.

The consistent increase in student numbers participating in the Religion Studies NSC Examinations, and the fairly remarkable pass rates over the past decade, make Gauteng Province an ideal case study to explore the challenges confronting educators with the implementation of Religion Studies.

Methodology

In terms of research design, this paper employs a cross-sectional study approach. A cross-sectional study approach allows for the production of a 'snapshot' about a population of interest at a given point in time or over a short period (cf. Lavrakas 2008). The purpose of a cross-sectional study is often descriptive and explorative, and in the form of a survey (cf. ibid.). In terms of sampling technique, this paper employs ' purposeful sampling , whereby 19 participants (n = 19) comprising 16 Religion Studies educators and 3 Subject Advisors were identified and invited by GDBE to participate in the survey to explore the challenges with the implementation of Religion Studies in the FET Phase. At the time of this survey, Gauteng Province had 21 schools offering Religion Studies as part of its curriculum, with 4 Subject Advisors. The 19 participants identified by GDBE was on the basis of (1) active involvement in the subject, and (2) willingness to participate. A key motivation for this specific sampling technique is that the authors do not intend on making any generalizations, but rather to explore the challenges confronting educators and Subject Advisors within a given context6.

Questionnaires were used as the preferred research instrument for data collection. Questionnaires comprised 'open-ended' questions, to ensure that we do not constrain responses and allow the participants to express their own concerns and challenges. The questionnaire comprised three major constructs. The first construct aimed at ascertaining the qualification and experiences of the educators and Subject Advisors in Religion Studies; the second construct focused on challenges experienced with the implementation of Religion Studies; and the third construct focused on issues pertaining to professional development.

In order to be compliant with the ethical considerations posited by the Department of Basic Education (DBE), the survey was conducted through the office of the Gauteng Provincial Coordinator of Religion Studies. In addition, each questionnaire contained a participant indemnity, which articulated the purpose of the survey, the use of the data collected, voluntary participation, and the non-disclosure of the participants identity in any research publication derived from the data.

In early June 2016, all participants included in the sampling frame were invited via email to participate in the survey. Respondents were initially provided with two weeks to complete and return the questionnaire via email. Based on the response rates after the initial invitation, a second follow-up email reminder was sent by the Gauteng Provincial Coordinator of Religion Studies to those who had not managed to respond on time. This finally resulted with the 19 identified participants (n = 19) completing the survey by end of June 2016.

Data Analysis: Findings and Interpretation

Due to open-ended questions offering a variety of responses, the questionnaires were analysed using ' thematic text analysis' procedures. Thematic text analysis is based on looking for occurrence and co-occurrence of themes. This is one of the most common forms of analysis in qualitative research (cf. Ryan & Bernard 2003: 87). This paper employed the six step procedure as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) reading through the responses to familiarize yourself with the data; (2) generating initial codes - i.e. coding interesting features of the data; (3) search for themes - i.e. collating codes into potential themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes - i.e. generating clear definitions and categories for each theme; and (6) analysing the themes. The authors employed a ' flat' coding system, whereby all codes were treated as being of the same level of specificity and importance. Codes were created using an 'inductive coding style', which implied that codes were generated directly from the survey responses.

We offer the following as an analysis of our data within the three constructs noted.

Construct 1: Qualification and Experience

In order to profile the qualification and experiences of the participants teaching Religion Studies, this construct posed three questions. The first question probed whether the participant held any 'qualification' in Religion Studies. 16 participants indicated ' No' they do not possess any qualification in Religion Studies, with 3 participants indicating ' Yes' they do possess a qualification. When asked to list the qualifications, 1 participant recorded a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) completed at Unisa, where 1 module focused on the ' Pastoral Role of the Educator' ; and the remaining 2 participants indicated a form of theological training. The two participants recording ' theological training' , were pastors serving as ad hoc Religion Studies educators in schools where the subject was offered as a seventh subject.

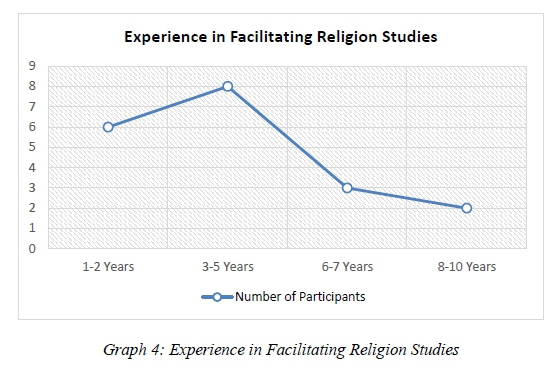

The second question probed ' experience' in teaching Religion Studies by posing the question of how long the participant was involved in facilitating Religion Studies. 6 participants indicated that they are fairly new to Religion Studies and have been facilitating the subject between 1-2 years. 8 participants indicated experience between 3-5 years; 3 participants indicated experience of 6-7 years; and only 2 participants indicated having experience of 8-10 years (cf. Graph 4). Majority of the participants (14) have between 1-5 years of experience.

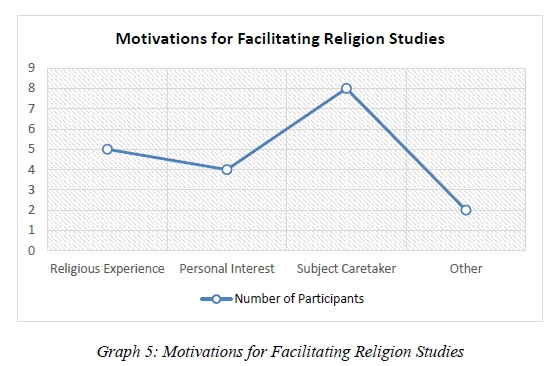

The third question aimed to understand what motivated the participant to teach Religion Studies. The responses were categorized into four themes (see Graph 5). 5 participants indicated ' Religious Experience' <T1.1>7. Religious Experience as denoted in <T1.1> implied being a pastor, or occupying an office within the local church - i.e. elder or treasurer. 4 participants indicated ' Personal Interest' <T1.2>. Personal interest as denoted in <T1.2> implied a ' passion' for the subject. 8 participants noted that they served as a ' Subject Caretaker' <T1.3>. All 8 participants indicating <T1.3> were identified as ' Life Orientation' educators that were tasked to facilitate the subject until a suitable educator is found. 2 participants indicated ' Other' <T1.4>. In this theme, <T1.4> implied that they were compelled to teach Religion Studies due to a lack of educators in the subject. 1 participant in <T1.4> indicated that his background in Biblical Studies (within the old Christian National Education curriculum) made him the ' preferred' candidate to teach Religion Studies.

A decade of Religion Studies implementation by unqualified educators in the subject, with limited experience, is emerging as an area of concern. The National Policy on Religion Education (2003: 14) notes that as an educational programme, teaching religion must be done by ' appropriately trained professional educators registered with the South African Council of Educators (SACE)'. The policy further expresses that teaching religion is not a 'mere technical transmission of factual information', its 'comprehensive role is demonstrated in the teacher's reflexive, foundational, and practical competencies to facilitate learning by (1) reflecting on the ethical issues in religion; (2) understanding the principles and practices of the main religions in South Africa; (3) being familiar with the ethical debates in religion; (4) understanding the intersections of class, race and gender with religion; and (5) being able to respond to current social and educational problems that include religion (cf. ibid.). In articulating the above, which aims to position the teaching of religion on par with other subject electives, the National Policy on Religion Education (2003: 16) also notes that ' there is a legitimate concern about the widespread "religion illiteracy" found among teachers, who call for and deserve the support that will enable them to deal with religion in the classroom'. While the policy does make 'space' for representatives of various religious groups to serve as ' occasional' guest facilitators on an ' equitable basis', a 'Pastor' serving as an ad hoc Religion Studies educator creates space for religious interest of a particular religious group to take precedence in the curriculum (vis-a-vis religious instruction), which is in contradiction to the National Policy on Religion Education (2003).

Construct 2: Challenges with Religion Studies Implementation

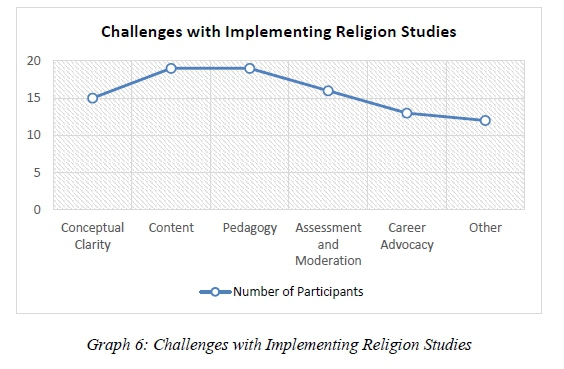

The second construct focused on ascertaining the challenges with the implementation of Religion Studies. In order to achieve this, the survey posed the following open-ended question: Discuss your challenges with the implementation of Religion Studies. The responses received by participants can be categorically grouped within six notable themes (as seen in Graph 6 below).

The first theme emerging in this construct is 'Conceptual Clarity' <T2.1>. The theme denoted as <T2.1> can be sub-divided into two dominant sub-themes: <T2.1.1> lack of understanding what Religion Studies is; and <T2.1.2> lack of engagement with the National Policy on Religion Education (2003). 15 of the participants responded that they do not understand what Religion Studies entails. 13 respondents in <T2.1.1> noted that they do not see a distinction between Biblical Studies offered in the old Christian National Education curriculum and the new Religion Studies. It became evident from the responses in <T2.1.1> that participants could not distinguish between 'Religion Studies', 'Biblical Studies' and 'religious instruction'. In addition, 6 participants in <T2.1.1> saw Religion Studies as a subject offering ' spiritual growth for students to function with ' piety in their local communities. The lack of conceptual clarity became more evident in <T2.1.2> when 12 respondents made reference to not knowing that there was a National Policy on Religion Education, and positioned the policy as being developed by the School Governing Bodies (SGBs). This lack of conceptual clarity has serious ramifications for the implementation of Religion Studies. This challenge is partially the result of not deconstructing the historical prejudices that existed with the implementation of Biblical Studies in the old Christian National Education curriculum. The replacement of Biblical Studies with Religion Studies, was seen by many of the respondents as a way of embracing diversity, by creating a subject that creates the facade of being inclusive while allowing educators the 'space' to continue the old Biblical Studies. This type of Religion Studies conceptualization stands in contradiction to the aims of the new curriculum, which Chidester (2006) regarded as being more 'educational', rather than 'religious', with the aim of ruling out any form of 'privileged' religious education. The lack of conceptual clarity and the substitution of Biblical Studies with Religion Studies may offer some insight into understanding why the student racial profile for the Religion Studies NSC Examination in Gauteng Province reflect the racial profiling of a majority ' black student cohort that was historically accustomed to Biblical Studies.

The second theme emerging in this construct pertains to ' Content <T2.2>. All 19 participants noted that this is one of their core challenges with Religion Studies implementation. <T2.2> comprises four sub-themes. The first sub-theme highlighted an ' inadequate textbook <T2.2.1>. The respondents noted that with the shift from OBE to CAPS, the only available textbook that complied with the CAPS requirements was the Shuter's Top Class Religion Studies books for Grade 10-12. However, while this book is prescribed, the book does not cover the full curriculum. This culminates with a lack of teaching materials to adequately facilitate the curriculum (cf. curriculum outline for Grades 10-12, Department of Basic Education 2011: 10). This brought to the fore the second sub-theme, 'authentic content' <T2.2.2>. Due to the lack of content, many educators opted to use information that they could access online. However, the challenge emerging in <T2.2.2> pertains to how does one identify content that is ' authentic' and free from religious biasness (for example finding content relating to abortion, homosexuality, etc.). As a result of <T2.2.1> and <T2.2.2>, the third sub-theme that came to the fore is 'partial curriculum facilitation' <T2.2.3>. Due to a lack of content, participants noted that for Grades 10-11 since it is assessed and moderated internally, they facilitate only what they are knowledgeable about8. In preparing students for the Religion Studies NSC Examination, participants noted that past year exam papers, exam memos, and the NSC Examination guidelines (that provide clarity on the depth and scope of the content to be assessed) form the basis of their teaching schedule, as opposed to the curriculum outlined in the CAPS. The fourth sub-theme focused on the need for 'Lesson Plans' <T2.2.4>. Due to a lack of content, participants noted that they require Lesson Plans, which could guide them through what needs to be taught - i.e. what content should be covered and how it should be assessed. The gap in content creates the ideal opportunity for the creation of Open Educational Resources (OERs) that could be remixed and reused for classroom application in Religion Studies.

The third emerging theme shifts the focus from content (what is learned) to ' Pedagogy' <T2.3> (how it is taught and learned). All 19 participants recorded a lack of pedagogical skills. 8 of the participants noted that a background in Life Orientation provided some basis for teaching Religion Studies, but the classroom skills needed was much more than what they possessed. 1 participant responded that ' Religion Studies was introduced to us as a subject that we would be baby-sitting. Thus, we were not capacitated with any pedagogies since the onset'. Dominant issues emerging in <T2.3> pertained to how does the educator address religious disagreements and conflicts that arise in the classroom in a constructive way; how does the educator manage religious diversity in the classroom; how does the educator present multiple religious perspectives in an unbiased way; how does the educator create an environment of religious tolerance and a safe space for student engagements; how does an educator facilitate a topical issue such as ' religion and abortion' when the educator has a view on the issue; and what happens to the religious identity of the educator, when he/ she strives to be neutral. The complexities of these sub-themes became more evident when 1 participant noted that in order to be unbiased, she suppresses her religious identity and positions herself as an 'atheist', while another participant noted that he is a 'pastor' and will 'not compromise on his beliefs'. The lack of pedagogical competencies creates the ideal space for religion studies experts to engage with educational theorists to address this deficit9, where content and pedagogy competencies are qualification for teaching Religion Studies, regardless of the personal religion, or lack thereof, of the educator.

The fourth theme emerging in this construct pertains to 'Assessment and Moderation' <T2.4>. 16 participants indicated that they have challenges with 'assessing' and 'moderating' Religion Studies. <T2.4> comprises three notable sub-themes. The first sub-theme is the 'lack of School-Based Assessment (SBA) tasks for Religion Studies' <T2.4.1>. SBA tasks are the continuous assessment tasks that serve as the purposive collection of the students' work. SBA marks are formally recorded for progression and certification purposes. Hence, it serves as a compulsory component for all students - i.e. students who do not comply with the SBA requirements may not be eligible to enter the Religion Studies NSC Examination. The lack of a set of agreed SBAs implies that the quality assurance process in assessment is lacking. The second sub-theme focuses on the 'formal assessment' <T2.4.2>. Formal assessment in Religion Studies caters for a range of cognitive levels, i.e. 30% recall (knowledge), 40% comprehension, and 30% analysis, application, evaluation and synthesis (cf. Department of Basic Education 2011: 24). However, the challenge experienced with assessing within this structure pertains to the lack of adequate content to prepare the student for such assessment. The third sub-theme focuses on 'moderation' <T2.4.3>. Moderation refers to the 'process that ensures that the assessment tasks are fair, valid and reliable' (cf. ibid.: 29). At Grade 10 and 11 assessment tasks are moderated internally by the head of the department or subject head at a school. However, Grade 12 tasks are moderated at provincial level. The challenge noted by the participants is that due to a lack of content knowledge and assessment skills, quality assured moderation is not possible. This notable challenge with assessment and moderation competencies provides an opportunity for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to reskill educators and develop the SBA tasks to adequately prepare students for the formal assessments, more especially for the Religion Studies NSC Examinations.

The fifth theme emerging in this construct relates to 'Career Advocacy <T2.5>. 13 participants noted that they experience challenges with articulating what students can do with Religion Studies after completion of the subject. A lack of career advocacy could cause a decrease in student enrolments, which would impact the ability to offer the subject in the FET Phase. However, this could be an opportunity to rectify the historical misconceptions of Religion Studies with Biblical Studies. The critical skills articulated within Religion Studies and its interdisciplinary scope, broadens career opportunities. With the globalization of religion and the relationship of religion with contemporary current affairs, opportunities exist in journalism, television broadcasting, community development, international relations, nongovernmental organizations, and as a religion-political analysist, university academic, school educator, social worker, social media analyst on religion, museum curator, digital curator, etc.

The sixth emerging theme in this construct is ' Other <T2.6>, in which we grouped issues relating to 'support'. 12 participants related challenges with support stemming from the local school to the national office. The first sub-theme relates to the implementation of Religion Studies as a seventh subject, and not being included in the school timetable <T2.6.1>. Participants noted that by not including the subject in the official school timetable, educators were compelled to teach the subject before the commencement of the school day or after hours. This had implications for the completion of the curriculum due to time constraints. The second sub-theme was the lack of administrative and general support from the national office <T2.6.2>. 1 participant noted, 'We have been excluded from all processes such as marking, memo discussions, etc. yet we are expected to complete Religion Studies improvement plans, Religion Studies support strategies and to report at national level in this regard' . These two issues under <T2.6> have greater implications for the 'quality assurance' of the subject.

Construct 3: Professional Development

The Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa (2011-2025) calls for the reskilling of educators by putting forward a plan for improving and expanding teacher education and development opportunities in order to improve the quality of teaching and learning in schools (cf. Department of Basic Education and Higher Education Training 2011). The plan defines the role of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) by noting that 'universities are responsible for ensuring that their teacher education and development programmes are responsive to national and provincial priorities, are accessible to teachers and meet their professional needs, and are relevant and of high quality'. The plan further proposes that educators take responsibility of their own professional development by (1) identifying gaps in subject knowledge; (2) learning with and from colleagues in Professional Learning Communities (PLCs); (3) accessing funding to do quality-assured courses that are content rich and pedagogically strong and that address their individual needs; (4) understanding curriculum and learning support materials; and (5) achieving the targeted number of Professional Development (PD) points. It is within this context that Mweli (2015) stressed the need for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to collaborate with the Department of Basic Education to address the skill deficit in Religion Studies implementation in the FET Phase.

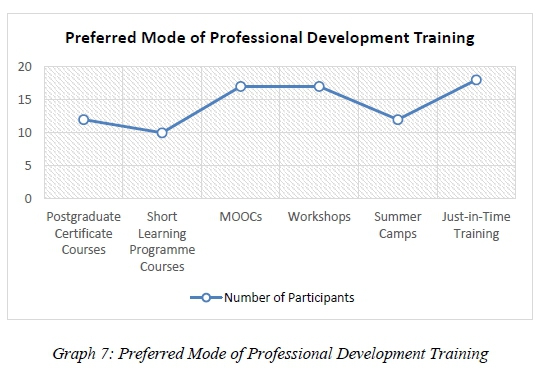

Based on this background, this construct focused on ascertaining the preferred modes of professional development training desired by the Religion Studies educators and Subject Advisors in Gauteng Province. In order to ascertain this, the following question was posed: ' List your preferred mode of professional development training'. The survey yielded an array of possibilities (cf. Graph 7). 12 participants listed 'Postgraduate Certificate Courses'; 10 participants listed 'Short Learning Programmes'; 17 participants listed 'MOOCs'10; 17 participants listed 'Workshops'; 12 participants listed summer camps; and 18 participants listed 'Just-in-Time Training'. Two important comments were identified in the listing, (1) that the professional development training cater for the time schedules of the educator, i.e. is flexible; and (2) that the training contribute towards their Professional Development (PD) points, which implies that it must be accredited and conceptualized at the appropriate National Qualifications Framework (NQF) level.

The responses yielded in this construct, highlight the possibilities that exist for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to develop Professional Development training that meets the needs of the Religion Studies educators and Subject Advisors, while taking into consideration their preferred modes of training11. This creates further opportunities for Religious Studies departments in HEIs to assist with the conceptualization of the subject, and develop the much needed content, pedagogy, assessment, and moderation competencies lacking in the implementation of Religion Studies within the FET Phase.

Conclusion

In this paper, we sought to engage with a reflection on the implementation of Religion Studies in the FET Phase over the past decade. At first glance, the increasing student numbers and the fairly stable pass rates created the impression of a fairly stable implementation. However, on closer analysis of reports produced by the Department of Basic Education on the subject, one notes that there are ' critical' problems with the actual implementation. Using Gauteng Province as a case study, the paper engaged with a cross-sectional study using open-ended questionnaires to gain a ' snapshot' of the state of Religion Studies implementation in the Province where n = 19. The findings in this paper reveal that there is a need for qualified Religion Studies educators and Subject Advisors; clarity on what Religion Studies entails and a differentiation with its historical predecessor, namely Biblical Studies; the need to produce adequate content that meets the curriculum needs outlined in the CAPS; the development of pedagogical, assessment and moderation competencies that speaks to the subject matter; a broadening and marketing of career opportunities; the need for support of the subject both provincially and nationally; and finally, the collaboration of Basic Education with Higher Education Institutions to meet the deficit in professional development. While this paper offers an alternative reflection of the state of Religion Studies in the Province, as opposed to the large student numbers and high pass rates, it highlights the opportunities for Departments of Religious Studies in Higher Education Institutions to collaborate with the Department of Basic Education to shape the subject matter, so that it is contextually relevant, and meets the basic quality standards as articulated in other subject electives.

We hereby offer this paper, as a baseline study for further research within Gauteng Province.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper hereby acknowledge the assistance of the Gauteng Provincial Coordinator of Religion Studies, Mrs Martha Joy Bernard-Phera for facilitating the questionnaire surveys among Religion Studies educators and Subject Advisors in Gauteng Province; and the National Coordinator of Religion Studies, Dr Krishni Perumal in providing and attaining permission to use the unpublished reports on Religion Studies statistics produced over the past decade.

References

Baumfield, V. 2008. Demanding RE: Engaging Research, Scholarship and Practice to Promote Learning. British Journal of Religious Education 30, 1: 1-2. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & V. Clarke 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3,2: 77-101. [ Links ]

Chetty, D. 2013. Connectivism: Probing Prospects for a Technology-Centered Pedagogical Transition in Religious Studies. Alternation, Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa. Special Edition No. 10: 172-199. [ Links ]

Chidester, D. 2006. Religion Education in South Africa: Teaching and Learning about Religion, Religions, and Religious Diversity. British Journal of Religious Education 25,4: 262-278. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Religion Studies (Grades 10-12). Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/CD/National%20Curriculum%20Statements% 20and%20Vocationa l/CAPS%20FET%20_%20RELIGION%20STUDIES%20_%20GR%2010-12%20_%20WEB_32D7.pdf?ver=2015-01-27-154241-517. (Accessed on 01 December 2016. [ Links ])

Department of Basic Education 2015. 2015 National Senior Certificate Examination Report. Department of Basic Education Printers: Pretoria. Available at: http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2015%20NSC%20Technica l%20Report.pdf?ver=2016-01-05-050208000. (Accessed on 01 December 2016. [ Links ])

Department of Basic Education and Higher Education Training 2011. Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa (2011-2025). Pretoria: Government Printers. Available at: http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/ISPFTED%20Booklet_Frequently %20Asked%20Questions.pdf?ver=2013-12-26-211924-000. (Accessed on 01 December 2016. [ Links ])

Department of Education 2003. National Policy on Religion and Education. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/religion_0.pdf. (Accessed on 01 December 2016. [ Links ])

Grimmitt, M. (ed.) 2000. Pedagogies of Religious Education: Case Studies in the Development of Good Pedagogic Practice. Essex: McCrimmons. [ Links ]

Ipgrave, J., R. Jackson & K. O'Grady (eds.) 2009. Religious Education Research through a Community of Practice: Action Research and the Interpretive Approach. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Lavrakas, P.J. 2008. Cross-Sectional Survey Design. In Lavrakas, P.J. (ed.): Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Louw, F. 2014. Religion and Education: A South African Perspective. In Wolhuter, C. & C. de Wet (eds.): International Comparative Perspectives on Religion and Education. Bloemfontein: Sun Press. [ Links ]

Molete, K. 2010. Department of Basic Education Report on Religion Studies Statistics NSC Grade 12 Examination Results 2008-2009. Unpublished. [ Links ]

Mweli, H.M. 2015. Department of Basic Education Report on Religion Studies Statistics NSC Grade 12 Examination Results 2010-2014. Unpublished. [ Links ]

Perumal, K. 2016. Department of Basic Education Report on Religion Studies Statistics NSC Grade 12 Examination Results 2015. Unpublished. [ Links ]

Ryan, G.W & H.R. Bernard 2003. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods 15,1: 85-109. [ Links ]

Ryan, M.B., J.H. Hofmeyr & J.E.T. Stonier 2014. Top Class Religion Studies. South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal: Shuter and Shooter Publishers. [ Links ]

Smit, J.A. & D. Chetty 2009. Advancing Religion Studies in Southern Africa. Alternation, Special Edition 3: 331-353. [ Links ]

Stern, L.J. 2010 Research as Pedagogy: Building Learning Communities and Religious Understanding in RE. British Journal of Religious Education 32:2: 133-146. [ Links ]

Union of South Africa 1953. Bantu Education Act No. 47 of 1953. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/bantu-education-act,-act-no-47-of-1953. (Accessed on 01 December 2016. [ Links ])

1 FET Phase = Further Education and Training Phase (Grades 10-12).

2 Bantu Education = a system enforcing racial compartmentalizing of education (cf. Union of South Africa, Bantu Education Act No. 47 of 1953).

3 For a further exposition on the way towards the National Policy on Religion and Education (2003) see Smit and Chetty (2009: 333-336).

4 A profiling of the 1 724 students in terms of gender and race provides further contextualization of the case study. In terms of gender profiling, there seems to be an even distribution of male and female with 885 females and 839 males constituting the 1 724 students. In terms of racial profiling, there is a notable historical pattern (i.e. similar to Biblical Studies) emerging with 1 465 Black students constituting the majority and a smaller cohort of 4 Asian, 47 Coloured, 53 Indian, and 155 White students forming the remaining 259 students.

5 In his analysis of the 2010-2014 Religion Studies NSC results, Mweli (2015) argued that the transitioning from OBE to CAPS with its first implementation in Grade 12, saw many teachers and learners struggle to become familiar with the content and the new assessment structure.

6 The authors acknowledge that different provinces face different challenges; therefore, this paper does not attempt to make generalizations.

7 Themes were coded using the prefix 'T' for theme, with a numerical value to denote the construct number and the theme number - i.e. <T1.1>.

8 Response from 1 participant: ' I leave out the Eastern Religions. These religions are not too familiar to me. At times, it is difficult even to know about the different sects within the same religion. Distinguishing practices, beliefs and sacred texts is not easy' . Most participants noted familiarity with Christianity, Islam, Judaism and African Religions, which became the focus of the curriculum.

9 For further exposition on pedagogies in Religion Studies see Baumfield (2008), Grimmitt (2000), Ipgrave, Jackson and O'Grady (2009), Stern (2010), and Chetty (2013).

10 MOOCs = Massive Open Online Courses.

11 Some Higher Education Institutions recognize this 'developmental' work as part of their community engagement initiatives.