Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal for the Study of Religion

versión On-line ISSN 2413-3027

versión impresa ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.28 no.1 Pretoria 2015

ARTICLES

A REDCo study: Learners' perspectives on religious education and religious diversity in Catholic schools in South Africa

Marilyn Naidoo

Department of Philosophy, Systematic and Practical Theology, University of South Africa. Naidom2@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Societies are changing rapidly, and in many countries there is an ongoing debate on the role of multiculturalism and religious diversity. REDCo, an international comparative research project set out to investigate whether developing ideas on multiculturalism and religious diversity influenced school pupils' views on these issues. A South Africa project was conducted to understand how learners experienced religious diversity within a new approach to religious education in South Africa. To answer the research question, the REDCo II questionnaire was used in Catholic schools. The descriptive study revealed that learners are generally positive towards the role and function of religion in schools. This indicates that Catholic schools are approaching religious education from a multi-faith perspective where teaching about other religions does not threaten the identity of the Catholic schools. Further research of qualitative nature is required to deepen the findings and to formulate theoretical and practical approaches to teaching religion education for use in religious schools.

Keywords: Religion education, religious diversity, Catholic schools, South Africa, independent education, religious socialization, tolerance, REDCo

1. Background

The 'REDCo: Religion in Education. A Contribution to Dialogue or a Factor of Conflict in Transforming Societies of European Countries' project was a European comparative research project aimed at establishing young people's views of religion, religious diversity and possibilities for dialogue in education. It was conducted from 2006 to 2009 in eight countries (England, Estonia, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Norway, Russia, and Spain), focusing mainly on the 14-16 age group.

More specifically, the project's main aim was to establish and compare the potential and limitations of religious education in the educational systems of the selected European countries (Valk et al. 2009). The correlation between low levels of religious education and a willingness to use religion as a criterion of exclusion and confrontation had already been pointed out (Jackson et al. 2007). Instead, the project planned to investigate how theoretical and practical approaches could support openness towards others, mutual respect across religions and strengthen cultural differences in the context of religious education in schools and universities. Historical depth and analytical clarity were obtained by comparing different approaches to addressing the core questions of dialogue and conflict in Europe and the search for ways to stimulate a process of supporting the growth of a European identity or identities.

In studying religion, the focus was not on abstract belief systems but rather focused on forms of religion and worldviews as presented by the adherents themselves (Jackson et al. 2007). The main theoretical stimulus for the project is the interpretative approach (Jackson 1997) with key concepts of representation, interpretation and reflexivity. With reference to E. Levinas, attention was directed to 'neighbor-religions' (Weisse 2003); the views of the neighbours in the classroom. This project planned to look into how theoretical and practical approaches could support openness towards others and mutual respect across religious.

One of the important overall research questions of the project was: ' what role can religion in education play concerning the way pupils perceive religious diversity?' (Friederici in Valk et al. 2009). To answer the research questions, a mixed method was used. First, an analysis was carried out of the developments, debates and contexts of religion and education in the eight participating countries (Jackson et al. 2007). This formed the foundation for empirical research, in which a large-scale qualitative study of teenagers' views on religion in schools was conducted (Knauth et al. 2008). Students were asked about their experience with religion, and also about their attitudes to the social dimension of religion in wider society, as well as in school. The qualitative study was used as a basis for the development of a set of hypotheses and a grounded questionnaire for a quantitative survey of young people's views (Valk et al. 2009) aimed at generalising the qualitative findings to much larger samples. In addition, studies of classroom interaction (Avest et al. 2009) and a study of teacher-strategies (van der Want et al. 2009) were included in the research.

After the REDCo project had been concluded, researchers decided to continue their cooperation as the REDCO NETWORK as a way of continuing their research exchange. In 2012 REDCo II, a quantitative follow-up study was established involving a variety of European countries (England, Estonia, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Finland, and Ukraine) and a global perspective (South Africa and Mexico) with the aim of learning from different contexts (Bertram Troost et al. 2014:18).

Both REDCo studies aimed to study the role of religion in education, and specifically to establish how school pupils perceived and dealt with religious diversity (Bertram Troost et al. 2014:19). REDCo II aimed to establish if the views of students had changed as compared to those in the REDCo I study in 2008. REDCo I found that the way religion was discussed in public had an influence on pupils' opinions (Bertram-Troost 2009:420). Rapid societal change had brought an ongoing debate in many countries on the roles of multiculturalism and religious diversity, and the aim of this project was to investigate whether this development had influenced pupils' views on these issues (Bertram Troost et al. 2014:18).

Specifically, the aim of the 2012 study was to provide insight into the reliability and validity of the 2008 findings. By relating the outcomes of 2008 and 2012 to the specific (historical) contexts, it was hoped to gain deeper insights into the role of religion in education with regard to the way pupils perceive and deal with religious diversity. The REDCo II study used an online survey as an instrument for more extensive surveys on religion and education (Bertram Troost et al. 2014:19).

2. The South African Project

A South African sample was not part of the original research, but the country was invited to join the study in 2012 so that the project could learn from different non-European contexts. The research question was focused on understanding how learners saw religion education in school so as to understand how learners perceived religious diversity. It was important to establish as few empirical studies (Dreyer, Pieterse & Van der Ven 2006; Roux & Du Preez 2006) in schools have been conducted and it was important to understand how learners perceived religion in a newly democratic society with a new approach to religious education. To answer this research question, the REDCo questionnaire was used within independent education in the context of a selection of Catholic schools.

Independent Schools

The South African School Act recognises two broad categories of schools; namely public and independent (DoE 1996). Government policy provides for independent schools by recognising that it offers citizens the freedom to practice the education of their choice and thereby allows for diversity of schooling (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004). The independent schools sector has expanded considerably, but nevertheless it represents only 4% of the total provision of education in the country, representing a total student population of almost 500 000 learners as compared to almost 12 million learners in public education, or 93% of the total number of learners (DoBE 2013). Research on the independent sector, specifically through a sample of Catholic schools, has highlighted the centrality of an ethos of the assimilation of white, Western and largely capitalist dominant values by learners (Christie 1990). More recently the Private Education and Development Project (PRISED) 2001-2002 survey explored the extent of the independent school sector's contribution to equity and quality (Dieltiens 2003), while the Human Science Research Council (HSRC) assessed the extent of independent education provision in the General Education and Training (GET) band, though it did not explore the details of demographic issues such as learner characteristics (Du Toit 2004).

Independent schools, which are in the main high-fee traditional institutions, once catered mainly for white learners, but currently the majority of learners in the sector are black, and diversity and socio-economic spread have increased significantly (Hofmeyr & McCay 2010). The growth in the number of independent schools has resulted in an increase in pupil migration between all schools, but racial and class stratification still largely coincide in independent schools (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:81). Government places much emphasis on regulation in the sector with the aim of ensuring quality, equity and a commitment to following the national curriculum guidelines, among other things (Motala & Dieltiens 2008:134). Using Kitaev's classification (1999), there are five types of independent schools; community schools, profit-making schools, spontaneous schools, expatriate schools and religious schools.

This article focuses is on religious schools, which continue to be popular in South Africa, since they not only provide a quality education that is affordable but one that is embedded in a religious value system. The roots of independent schooling in South Africa are strongly religious and go back to the earliest mission or church schools (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:146). Some 80% of independent schools established in the 25 years before 2001 were religiously affiliated; since then ownership patterns have changed from church to individuals and companies (Dieltiens 2003). There is a trend of religious (mainly Catholic and Anglican) schools converting to public schools on private property owing to cost considerations (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:154). The result of these trends has been the emergence of a continuum of private and public education and a blurring of the traditional differences between public and private education (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:82).

According to the HSRC, over 46% of all independent schools can be classified as religious (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:154). Within the Independent Schools Association of South Africa (ISASA) membership, the database also shows that 44 percent of its schools were faith-based in 2001 (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:154). There is however a wide range of different religious schools, encompassing Christian, especially of the fundamentalist variety, Jewish, Hindu and increasing numbers of Muslim schools. The PRISED survey in 2001 (Dieltiens 2003), found that 71% were Christian schools, 5% Muslim, 3% Jewish and 0, 5% were Hindu schools.

Catholic Schools in South Africa

The Catholic Church seeks to ' serve and participate as a meaningful partner in the ongoing development of South African society through its mission in Catholic schools' (CaSPA 2010:1). Catholic schools have focused their work largely in rural and peri-urban schools, situated in the poorer, less developed parts of Southern Africa and are known to offer superior education in spite of being under resourced. Currently, Catholic schools educate about 160 000 learners representing diverse cultures and religions, with Catholics forming the minority (27%), and have a racial make-up of 90% black pupils and 10% white (CIE).

In total, there are 346 Catholic schools in South Africa; some 250 of these are public schools on private property. In most other countries such institutions would be considered private, but in South Africa they are considered to be public schools and governed by Section 14 of the South African Schools Act (DoE 1996). Under agreements signed with provincial education departments, such schools have the right to promote and preserve their own special religious character. The remaining 95 schools are independent and owned by dioceses and religious congregations. In both types of schools, the school has a right to preserve its Catholic ethos and character, a situation made possible by the deeds of agreement between the state and the Catholic Church (CaSPA 2010).

In terms of teaching religion, Religious Education (RE) 'lies at the heart of the school curriculum which reflects the special character of the school and is part of the Church's evangelizing mission' (Fostering Hope, 2006:2). Because religious freedom is guaranteed by the Constitution as a fundamental human right, Catholic schools with their particular religious identity, have a RE Policy (Fostering Hope 2006) endorsed by the South African Catholic

Bishops' Conference and is in line with the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (DBE 2011). According to the Catholic Institute of Education (CIE), the school curriculum includes a substantial Religious Education programme which is ' life-centred, integrated, encompassing areas of explicit religious exploration and aspects of personal growth' (CIE). The RE programme follows a multi-religious approach and ' strives to be respectful and sensitive to the diversity of chosen and inherited religious paths of students' (CIE). It ' actively endeavours to promote mutual understanding and respect among people of different religious and other world-views' (Fostering Hope, 2006:6). The programme is rooted in the Catholic tradition but the scope of this accommodation includes other Christian traditions, while those from other religions are welcomed to participate in ways that nurture their own spiritual development (CaSPA 2010:2). Typically the RE programme in secondary schools follows the CORD curriculum (CIE) and both Catholics and non-Catholics attend the same RE classes about three classes per week, with attendance of Mass being compulsory. Many of the lessons (Theological Education, Education for personal growth and relationships, Education for religious communities, etc.) in the religious education programme are link to the compulsory subject Life Orientation, for all grades, that promotes the teaching of life skills.

Religion education in the national curriculum is designed to advance knowledge about the many religions in South Africa and the world, and also to cultivate an informed respect for diversity (DoE 2003). The national Policy on Religion and Education (DoE 2003) made a radical break with Christian National Education (CNE), imposed by the apartheid regime, which required confessional religious instruction in schools. As a subject, religion is taught in two ways: the first, Religion Education is a component of the learning area of Life Orientation, and is studied by learners throughout their school career and as an examinable subject, the second is Religion Studies, a subject that learners can elect to study until graduation.

While the national curriculum's infusion with the respect for values, cultural and religious diversity is positive, it is clear that the conditions and context for effective implementation of the curriculum are not in place in most public and independent schools (Zinn & Keet 2010:79).

Legislators have made the assumption that teachers will un-problematically adopt a multi religious approach, but teachers have to be sensitized to the different values embedded in each belief system and have to be equipped to facilitate these values (Moodley 2010). At the same time certain concessions are made that allow independent schools to maintain their particular ethos, in many cases confessional or sectarian Christian religious education is still being offered. Hence within independent schooling there is much debate about the role of religious schools in terms of the goals of nation-building (Motala & Dieltiens 2008:123). For example, a recent report on the Pew Research Forum and Public Life, Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa (Lugo 2010) showed a high rate of religious illiteracy in South Africa with 76% of Christians in South Africa saying that they know very little about Islam. It is of course possible a Christian student may respect Muslims or Hindus while not want to know anything about them. Research is needed to understand the impact of religion education on such attitudes.

It must be said that for South Africa, the concept diversity does not accumulatively build on existing notions of ' multiculturalism' or 'co- existence' but rather on new ways of thinking about diversity (Zinn & Keet 2010:76). Ambivalence towards particular notions of diversity needs to be viewed against the political, socio-historical realities of South Africa's recent past, a past that continues to impact strongly on present realities and orientations. Despite the remarkable political changes since the first democratic elections and subsequent attempts to improve national unity, there have been mixed and often marginal effects upon inter-group relations (Steyn & Foster 2008:25). In divided societies like South Africa people identify more readily with one of its ethnic, racial or religious components than with the society as a whole (Mattes 2002). In addition, it may seem that one of the ways religious diversity is obscured is precisely by creating an image of South Africa as a ' Christian country' .

With significant increases in the growth of private education one has to question whether religious schools in South Africa take seriously the focus of citizenship education (and religious diversity) since no explicit monitoring of the Policy is in place (Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:83). According to Treston (2008:4) 'Catholic schools are called to be a witness to authenticity and integrity, but there are daily challenges of reconciling the tensions between compliance and identity and of remaining authentic within a multicultural and multi-faith context' . This then, became the motivation of this research project to understand how learners in Catholic schools perceived religious diversity in schools and whether these perceptions could indicate support for a multi-religious, inclusive approach to Catholic education.

3. The Research Project

With regard to the REDCo II study, it was decided that each country could choose specific topics/ sub research questions that were most relevant in their own context, within the framework of the questionnaire used. The aim of the South African project was to understand how learners perceived religious diversity by exploring their views on religion in school. Given the motivation above and since there is a dearth of empirical studies in the independent school sector (Motala & Dieltiens, 2008:133; Hofmeyr & Lee 2004:146) it was considered worthwhile to conduct a study within this group.

Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire for the REDCo II quantitative research was worked out by adapting the questionnaire from the REDCo I. Valk et al. Friederici (2009) describes the steps of the research process that were taken in developing the REDCo I questionnaire. First, the problems and phenomena related to the research topic (religious dialogue and conflict in school) were explored. Qualitative data was discussed from as many perspectives as possible in order to formulate hypotheses which could be used in the quantitative study. A tree of variables was constructed on the basis of these hypotheses in order to operationalise them. The research team searched for dependent and independent variables which could describe in total the hypotheses. These variables formed the basis of the questions of the questionnaire. After the questionnaire had been formulated, careful attention was paid to translating them into the relevant languages using the TRAPD process (Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pre-testing and Documentation) (Bertram-Troost & Miedema in Valk et al. 2009). The protocol establishes a clear procedure, but it was noted that it did entirely prevent translation problems with regard to specific research concepts.

The questionnaire from 2008 was shortened, to sharpen the focus on the societal aspect of religion in relation to dialogue and conflict (Bertram-Troost et al. 2014). The 2008 questionnaire was paper-based, but in 2012 an online questionnaire was developed. The online version was more convenient to pupils, and it was not necessary for the researchers to visit schools to arrange the distribution and answering of the questionnaires. The data obtained were directly uploaded into an SPSS file, which made the processing of data easier and more accurate.

The original questionnaire (see appendix for a full version) was mainly relevant to the European context of secularisation. Questions 80-84, for example, involved issues of country of birth of the learners and/or their parents and dealt with migration background information and were therefore an extension of the 2008 study. However, the generic nature of the questions was found to be useful in generating descriptive data from the South African context. The structure of the questionnaire was divided into four parts;

1. How do pupils see religion in school?

2. What role has religion in pupils' lives and their surroundings?

3. How do pupils consider the impact of religions for dialogue and conflict?

4. Biographic/personal details

The first part represents the school level, the second one the personal level and the third section represents the social level. For this article only part one will be discussed as the focus in this article is how learners experience religious diversity within a new approach to religious education in Catholic schools. A more complete accounting of the REDCO II project (Bertram Troost et al. 2014) and the South Africa project (Naidoo 2014) is found in the Journal of Religious Education of Australia.

Procedure

An online questionnaire supplied by REDCo II was targeted at school children aged between 14 and 16 (Grade 8 to Grade 10), to be administered in Catholic schools. Permission to conduct the research was obtained from the Unisa Ethics Committee and the Catholic Institute of Education (CIE); because learners were below the legal age, consent was also obtained from parents and guardians.

The administration of the questionnaire was carried out by the teachers of the schools during school hours, with the researcher providing the questionnaires and guidelines. Due to the nature of the country's developing educational context, the questionnaire could not be administered online because of a lack of computer facilities in the targeted schools, and a pen-and-paper survey was therefore provided. The questionnaire was captured online by the researcher and the data was recorded on SPSS software.

Some 795 questionnaires were sent to the selected schools and 784 were completed and returned; after cleaning, 646 were entered on the database. The data was further filtered to 637 responses, representing an 80% response rate. A significant number of the responses were discarded because they did not fall within the 14-16 target groups. It can be noted that this speaks to a contextual challenge, in that many of the respondents were older learners still in school.

An analysis was carried out to produce descriptive statistics using cross-tabulations and the chi-square, which allowed for non-normal distributions of responses and yielded more information on specific patterns in the answers than using means and standard deviations with t-test would have. The main trends in the data were described in terms of frequencies and percentages. Variables used focused on gender, location of school, type of school and religious background.

Sample

Given the limited resources available to the national REDCO groups, it was decided to constitute carefully selected sample groups (Béraud 2009:24). However, these cannot be considered representative samples in the strict sense of the term. The goal of the research was not to describe a bounded population but instead to generate some initial understanding of the issue of religious diversity in a subset of South African schools, and a sample was therefore constructed to reflect heterogeneity in Catholic schools. There is a lack of information on the overall population of religious schools in South Africa, as Motala and Dieltiens (2008:133) show. South Africa mirrors the experiences of other developing countries in that there is a lack of consistent and reliable information to define the sector (2008:133). For these reasons, non-probability sampling methods were used with the focus on heterogeneity, including urban and rural school contexts, public and private education, and pupils with or without religious affiliation. Comparisons between countries using non-probability samples must be treated with caution. The results of this analysis must be interpreted as applying to the sample, and should not be generalised.

The sample (N = 637) was made up three schools; a large public rural school (co-ed) and two smaller independent urban schools from Gauteng province, one an all-girl school and the other all-boy. There are 50 Catholic schools in Gauteng (43 independent and seven public) with 33 130 learners; they represent 14% of schools (CIE). This sample represents 6% of the total population.

The sample included 269 male (42%) and 367 female (58%) learners; the average age of the respondents was 14.5 years. The three schools represent a split of 48% rural/public schools and 52% urban/independent schools. The languages spoken at home were African languages from four language groups; Sepedi, Setswana, isiZulu and isiNdebele (80%) and (20%) were English speaking. Some 98% of respondents in the sample participated in compulsory non-confessional Religious Education in classes. Some 35% of learners had studied Religious Education for one year, 19% for two years and 13% for three years.

Religious Background of Learners

In this sample 87% of respondents stated that they have a religion, comprised of: Evangelical 55% (made up of Christian denominations and African Independent churches), Catholic 30% (which is in line with the 27% profile of Catholic schools) and Other Religions (12%), made up of African Religion (10%) and minority religions like Islam (1%) and Hinduism (1%).

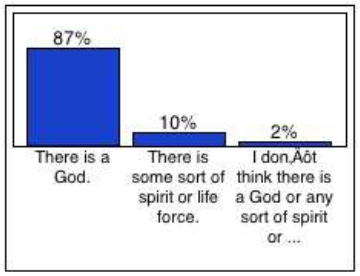

Some 87% of respondents said they believed that a god existed, 10% said they believed in some sort of spirit or life force and 2% said that they did not believe that a god existed. To the question 'how important is religion to you?' , which was asked on a five-point scale (with 1 indicating ' not important at all' and 5 indicating ' very important' , some 24% of the learners responded with 'important' and 57% with 'very important'. In the international sample, South Africa was the only country where a majority (57%) chose point 5. It was interesting to note that 65% of girls as compare to 35% of boys said that religion was very important.

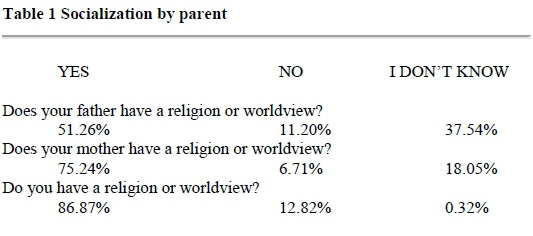

The most influential sources of religious information were: family, 74%; school, 54%; books, 50%; faith community 42%; friends, 20%; and the internet, 15% and media, 12%. Family was therefore seen as very important as a source of information about religion. A variable was added, the sharing of religious ideas by the respondent and their parents, to assess whether respondents' views depended on socialisation by their parents. It was assumed that respondents who did not know their parents' beliefs were not influenced by their beliefs. In Table 1 we see that in 37% of respondents did not know whether or not their father had a belief system, which reflected the fact that in many cases their fathers were absent, while only 11% knew their faith did not a belief system. Significantly more learners (75%) knew their mothers had a belief system, reflecting the general trend for women to be more religious than men and for children to have a closer relationship with their mother (ter Avest, Jozsa & Knauth 2010:302).

4. Results

Part one of the questionnaire looked at learners' views on religion in school; how religion should function in school, the way religion could manifest in school in terms of religious accommodation and cooperative models of religious education. This was to understand the role of religion in education and how it impacted learners' perception of religious diversity.

a. Experience of Religion in Schools

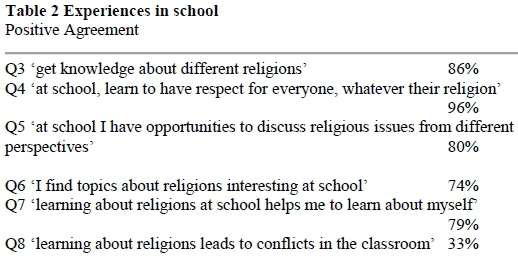

In Table 2, learners had strong positive agreement on the whole towards their experiences of religion in school.

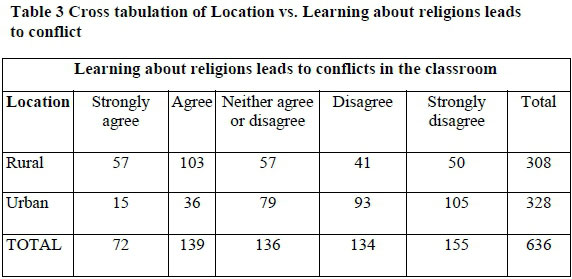

Q8 provided the least overall agreement: more rural schools strongly agreed (57%) with this statement compared to urban schools (15%). Table 3 shows the relationship between location and learning about religion leads to conflict.

The results from the Pearson Chi test revealed that there was a significant relationship between the two variables (Chi square value = 99.52 DF =4, p< 0.0001). A significantly lower proportion of urban schools (15/72 = 20.83%) compared to the rural school (57/72= 79.17%), strongly agreed with 'learning about religions leads to conflicts in the classroom'. The strength of this association is moderate indicated by the Cramer's V value of 0.4. In addition, more female learners agreed (35%) that Q8 religion leads to conflict than males (30%). Catholic learners agreed by 29%, Evangelicals by 28% and Other Religions by 47%. It would seem that rural learners, female learners and adherents of other faiths were more likely to support the idea that learning about religions leads to conflicts in the classroom.

b. Appearance of Religion in Schools

Learners were generally positive about the way religion appeared in schools, like indicators of religious food requirements, facilities for prayer and voluntary religious service as part of school life. The exception to this were the questions that dealt with making allowances for learners' religious needs; Q11 'learners should be able to wear religious symbols at school,' only 13% of respondents strongly agreed with visible symbols (like headscarves) with a 32% unsure response, although 37% of the sample had strongly agreed with discreet ones (Q10 e.g. small crosses). The reason for learners supporting discreet symbols over more visible ones could be because the example of headscarves is not a common experience in this school (as there are fewer Muslim students), religious indifference or religious illiteracy.

Another question in this category was Q13 'learners should be excused from taking some lessons for religious reasons' - a well-known example in the South African context would refer to Muslim children that leave school to go to a mosque for prayers on Fridays. Only 15% of learners strongly agreed and 26% agreed. Catholic learners strongly agreed to the statement by 13%, Evangelicals by 13% and Other Religions by 22%. Learners from Other Religions support this idea most. There was 26% unsure response; with Evangelicals being more uncertain by 31%, Catholics by 24% and learners from Other Religions being the least unsure (18%).

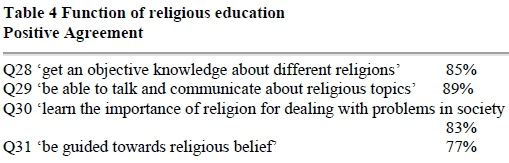

c. Function of Religious Education in Schools

In terms of the function of religious education in schools there was very positive agreement for the suggestions that school could serve in this capacity (see Table 4).

With Q31 'be guided towards religious belief we see more female learners strongly agreeing (46%) than males (31%). This is in agreement with the finding that 65% of girls compared to 35% of boys stated that religion is very important. The high agreement to this question could be because learners are studying in a religious school. Catholic learners strongly agreed with the statement by 39%, Evangelicals by 40% and other religions by 44%. It seems there is a tension between studying in a religious school and its religious formation versus learning RE in an objective way. This question correlates with Q21 that religion helps ' to learn about my own religion' where 86% of respondents agreed, with rural schools strongly agreeing by 48% and urban schools by 64%. Urban schools are owned by dioceses and religious congregations and have a stronger Catholic ethos.

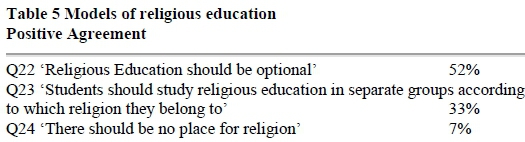

d. Models of Religious Education

To questions on different models of religious education and how it supported dialogue (see Table 5), there were mixed responses.

Q25 'Religious education should be taught to learners together, whatever differences there might be in their religious or denominational background'

67%

Q27 'Religious Education should be taught sometimes together and sometimes in separate groups for each religion students belong to'

40%

To the question Q22 'religious education should be optional' there was an overall 52% agreement; with Catholic learners strongly agreeing by 15%, Evangelicals by 17% and other religions by 30% - other religions show highest support for optional religious education. Many respondents were opposed to the suggestion that Q23 'learners should study religious education in separate groups according to which religion they belong to;' Catholic learners strongly disagreed by 30%, Evangelicals by 24% and other religions by 17% - learners from Other Religions show the most agreement with the idea. The proposal Q27 'Religious Education should be taught sometimes together and sometimes in separate groups for each religion learners belong to' received an ambivalent response: 26% of respondents were neutral, on the whole 29% agreed and 34% disagreed. Catholic learners strongly disagreed with this statement by 17%, Evangelicals by 14% and other religions by 8%.

e. Qualitative Responses

There was a small percentage (13%) of qualitative responses. Of these more than two-thirds support for Religious Education and diversity. For example, one responded: ' ever since I started to learn about other religions at school I am able to be friends with people of other religions'. Another wrote: 'every single school must teach religion education because this will reduce the hate and fighting at communities and at school'. Another's view was: 'I personally think that everyone is different and all have different views, we just have to respect these views'.

5. Discussion

The aim of the South African project was to understand how learners understood the presence of religion in school so as to gain insight into how learners perceive religious diversity. Given their experience in schools, learners revealed support for the goal and function of multi-religious religion in school and indicated an open to dialogue on religious issues. The very positive response was different from the rest of the international sample as South Africa is often described as a highly religious country and many consider their religious beliefs to be central to their lives. In a general way, this is also reflected in this study. This should also be understood within the dramatic socio- political changes of the country, the establishment of a secular state, a stress on religious freedom, tolerance and a democratic ethos from political and religious leaders. In addition, religious organizations have at their disposal a political theology that supports human rights, democracy and development (Piper 2009:72). Catholic schools historically have had a strong focus on interreligious dialogue and tolerance however results could have been different in another type of religious school. In spite of this, the overall finding is significant in a highly intolerant society where discriminatory structures and practices are sewn into the very fabric of society (Zinn & Keet 2010:83).

In general it can be said that the majority of learners relate to religion in a positive way and since religion is very important to a larger majority of respondents, it determines the whole of life, so there is respect for other people who 'believe' and religion is not regarded as nonsense. This appears to be the most decisive factor for the way the learners view religious diversity, with learners tending to be generally more positive, the more important religion is to them. At the same time their ideas of religion are open to change. In this sample it was evident that learners appreciated the school as an institution that transfers knowledge about religions with a focus on the societal and the communicative dimension of religion. In school there were opportunities to discuss religious issues from different perspectives however this was the experience more for those in urban schools and from Christian learners. Learners acknowledged that learning about religions can lead to conflict in the class. There was support for religious accommodations in school however there was more support for this from adherents of other religions. In terms of different models of religious education, Catholic learners were most in favour of different religions studying together whereas it seemed that those from other religions were least in favour of this. At the same time, half the sample felt that religious education should be optional with the main supporters of this being those from other religions.

In spite of the fact that objectivity with regard to knowledge about religions is preferred, learners also felt that religious education should guide them towards religious beliefs which could be due to the fact that learners are attending a religious school. It seems there is some tension between studying in a Catholic school with the goal of religious formation versus experiencing RE from a multi-faith perspective in line with the national RE Policy. The presentation of education through the perspective of a Catholic 'world view' or anthropology and its accompanying values needs to be balanced with the encounter of other faiths, without also falling into religious relativism (Pollefeyt & Bouwens 2010:200). This is a tension which is difficult to manage but if Catholic schools are to function in a religiously and culturally pluralistic setting, it needs to relate positively with different denominations, faiths, and ideologies (Sullivan 2002:10). Further research and explorations are needed to understand how religious schools with their particular religious doctrine, ethos and socialisation, engage with a multi-religious principle of teaching and learning to achieve an objective survey of the expressions of religions.

With Christian learners being the majority (85%), this sample could be viewed as a relatively homogenous. This raises a number of questions. Are Christian perspectives emphasized at the expense of others in these schools? Is there enough space made for learners from other religions? From this study we find learners almost resistant to religious diversity - adherents of other religions are most likely to view learning about religion as leading to conflict, and prefer separate religious education classes and feel there are less opportunities to discuss religious issues from different perspectives. On the other hand, adherents of other religions (14%), mostly made up of African Religion prefer that at school they be guided towards religious belief, are less likely to prefer mixing with others from other religions and are more likely to discuss religious opinions and to want to convince others of their religious beliefs. Christie's (1990) analysis suggests that sooner or later significant cultural challenges and a new school culture will come about, because the presence of black learners will demand a new school culture. Further research is of a qualitative nature (Chidester & Settler 2010:215) would be helpful to understand how indigenous religion deals with the secular concept of religious diversity.

It is important to note that a significant majority of South Africans, even though Christian, still subscribe to traditional beliefs and ancestral rituals where the African worldview is a religious worldview (Mbiti 1990:15). Actually a broader discussion needs to be had of the intellectual and cultural hegemony of the West and the growing discourse that demands the acknowledgement and inclusion of indigenous knowledge systems in education. In speaking about traditional African religions of South Africa, Amoah and Bennett (2008:19) state that 'non-discrimination is essential to ensure diversity, and until equal rights are fully mobilized, diversity will not be attained nor will traditional religions be revived to compete on their own terms in the free marketplace of faith'. The politicising of religious environments and traditions and the focus of a human rights perspective needs to impact on the teaching and learning of religion (Roux 2007:481. It must be noted that in this project the extent of traditionalism could have been more pronounced if the categories of choice of religion on the questionnaire had been clearer.

Gender appears to be a distinctive factor in the importance of religion; significantly more females compare to males stated that religion is very important. Girls more than boys tend to be in favour of religion as a school subject, they want to know more about and from other religions, and are more positive about the possibilities to live together with people of different religions in society and also felt that religion leads to conflict, more than the male response. This was found in other REDCo samples as well (ter Avest, Jozsa & Knauth 2010:302). The strong opinion by females towards religion may be because mothers are more active in the religious socialization process.

What was also evident in this study was responses of Catholic learners who generally were most in favour of cooperative religious education models, mixing with others from different religions, least likely to convince another about religious beliefs and most likely to state that respecting the religion of others helps to cope with differences. This may indicate the unique religious socialization within the tradition and in Catholic schools and could point to the inclusive approach to religious education. As the Catholic Institute of Education states, the religious education programme in Catholic schools strives to be 'respectful and sensitive to the diversity of chosen and inherited religious paths of learners' (CIE). Catholic schools have a history of actively striving for tolerance and respect for cultural and religious differences, and were racially integrated even during apartheid (Christie 1990). They see their schools ' not as private initiatives but an expression of the reality of the Church, having a very public character' (CaSPA 2010:4) and fulfill a service of public usefulness.

6. Conclusion

This descriptive study was useful in that it found that learners are positive towards religion in school and religious diversity broadly. However it must be noted that attitudes of religious diversity and actions are not simple and linear. The relationship between the cognitive, affective and behavioural components are much more complex than once assumed and may be determined by factors such as intentions, priorities and the contextuality of time and place (Van der Ven 1993:136-137). Hence deeper research is needed into these findings to determine how and why learners perceive and deal with religious diversity in particular ways. This could create an orientation into personal development and can help develop theoretical and practical approaches to teaching religion education. Research is also needed into the hidden curriculum; how school culture and identity shape learners attitudes towards diversity. These initiatives can ultimately support the process of democratic citizenship and social cohesion.

References

Amoah, J. & T. Bennett 2008. The Freedom of Religion and Culture under the South African Constitution: Do Traditional African Religions Enjoy Equal Treatment? Journal of Law & Religion 24,1: 1-20. [ Links ]

Avest, K.H. ter, D-P. Josza, T. Knauth & G. Skeie (eds.) 2009. Dialogue and Conflict on Religion. Studies of Classroom Interaction in European Countries. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Béraud, C. 2009. Who to Survey? Considerations on Sampling. In Valk, P, G.D. Bertram-Troost, M Friederici, C. Béraud (eds): Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Quantitative Study. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Bertram T.G., O. Schihalejev & S. Neill 2014. Religious Diversity in Society and School: Pupils' Perspectives on Religion, Religious Tolerance and Religious Education. An Introduction to a series of articles related to the REDCo Network. Religious Education Journal of Australia 30,1:17-23. [ Links ]

Bertram-Troost, G.D. 2009. How do European Learners see Religion in School? In Valk, P, G.D. Bertram-Troost, M Friederici, C. Béraud (eds): Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Quantitative Study. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Bertram-Troost, G.D. & S. Miedema 2009. Semantic Differences in European Research Cooperation. In Valk, P, G.D. Bertram-Troost, M Friederici, C. Béraud (eds): Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Quantitative Study. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Bertram Troost, G., O. Schihalejev & S. Neill 2014. Religious Diversity in Society and School Pupils' Perspectives on Religion, Religious Tolerance and Religious Education. An Introduction to a Series of Articles Related to the REDCo Network. Religious Education Journal of Australia 30,1:17-23. [ Links ]

CaSPA (Catholic Schools Proprietors' Association). 2010. Briefing and Discussion Document for the Meeting with the Minister of Basic Education: A Motshekga and CaSPA. Unpublished document. [ Links ]

Christie, P. 1990. Open Schools: Racially mixed Catholic Schools in South Africa 1976-1986. Johannesburg: Ravan. [ Links ]

Chidester, D. & F.G. Settler 2010. Hopes and Fears: A South African Response to REDCo. Religion & Education 37:213-217. [ Links ]

CIE - Catholic Institute of Education. www.cie.org.za. (Accessed 15 April 2014. [ Links ])

Dieltiens, V. 2003. Private Secondary Institutions. Quarterly Review of Education and Training in South Africa 10,2:3-12. [ Links ]

DoE (Department of Education) 1996. South African Schools Act, Act 86 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DoE (Department of Education) 2003. National Policy on Religion and Education. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2013. Education Statistics in South Africa 2011. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DBE (Department of Basic Education) 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Life Orientation. Further Education and Training Phase Grades 10 - 12. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DBE (Department of Basic Education) 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Religion Studies. Further Education and Training Phase Grades 10 - 12. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Du Toit, J. 2004. Independent Schooling in Post-Apartheid South Africa: A Quantitative Overview. Cape Town: HSRC. [ Links ]

Friederici, M. 2009. From the Research Question to the Sampling in Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Quantitative Study. In Valk, P, G.D. Bertram-Troost, M Friederici, C. Béraud (eds): Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Quantitative Study. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr, J. & S. Lee 2004. The New Face of Private Schooling. In Chisholm, L (ed.): Changing Class: Education and Social Change in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr, J. & L. McCay 2010. Private Education for the Poor: More, Different, Better. The Journal of the Helen Suzman Foundation 56:50-56. [ Links ]

Jackson, R., S. Miedema, W. Weisse & J-P Willaime (eds.). 2007. Religion and Education in Europe. Developments, Contexts and Debates. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Knauth, T., D-P. Jozsa, G.D. Bertram-Troost & J. Ipgrave (eds.). 2008. Encountering Religious Pluralism in School and Society. A Qualitative Study of Teenage Perspectives in Europe. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Kitaev, I. 1999. Private Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Examination of Theories and Concepts Related to its Development and Finance. Paris: Unesco/IIEP. [ Links ]

Lugo, L. 2010. Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: Pew Research Forum and Public Life. [ Links ]

Mattes, R. 2002. South Africa: Democracy without the People? Journal of Democracy 13,1: 22-35. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1990. African Religions and Philosophy. Heinemann: Oxford. [ Links ]

Moodley, K 2010. South African Post-apartheid Realities and Citizenship Education. In Reid A., J. Gill & A. Sears (eds.): Globalisation, the Nation-state and the Citizen. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Motala, S & V. Dieltiens 2008. Caught in the Ideological Crossfire: Private Schooling in South Africa. South African Review of Education 14,3:122138. [ Links ]

Naidoo, M. 2014. Student Attitudes towards Religious Diversity in Catholic Schools in South Africa, Religious Education Journal of Australia 30,2: 32-37. [ Links ]

Piper, L. 2009. Faith-Based Organisations, Local Governance and Citizenship in South Africa. In Brown, D. (ed.): Religion and Spirituality in South Africa: New Perspectives. Pietermaritzbrg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Pollefeyt, D. & J. Bouwens 2010. Framing the Identity of Catholic Schools: Empirical Methodology for Quantitative Research on the Catholic Identity of an Education Institute. International Studies of Catholic Education 2,2:193-211. [ Links ]

Roux, C. & P. du Preez 2006. Clarifying Students' Perceptions of Different Belief Systems and Values: Prerequisite for Effective Educational Praxis. South African Journal for Higher Education 30, 2:514-531. [ Links ]

South African Catholic Schools 2006. Religious Education Policy: Fostering Hope. Johannesburg: CIE. [ Links ]

Steyn, M. & D. Foster 2008. Repertoires for Talking White: Resistant Whiteness in Post-apartheid South Africa. Ethnic and Racial Studies 31,1: 25-51. [ Links ]

Sullivan, J. 2002. Catholic Education Distinctive and Inclusive. London: Kluwer. [ Links ]

Treston, K. 2008. Challenges for Catholic Education: A Global Perspective, Catholic Education 17,1, 4-5. [ Links ]

Valk, P. 2009. The Process of the Quantitative Study. In Valk, P, G.D. Bertram-Troost, M Friederici, C. Béraud (eds): Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Quantitative Study. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Valk, P., G. Bertram-Troost, M. Friederici & C. Beraud (eds.) 2009. Teenagers' Perspectives on the Role of Religion in their Lives, Schools and Societies: A European Qualitative Study. Muenster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Want, A., van der, C. Bakker, K.H. Avest & J Everington (eds.). 2009. Teachers Responding to Religious Diversity in Europe. Researching Biography and Pedagogy. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Van der Ven, J.A. 1993. Practical Theology: An Empirical Approach. Kampen: Kok Pharos. [ Links ]

Weisse, W. 2003. Difference without Discrimination: Religious Education as a Field of Learning for Social Understanding? In Jackson, R. (ed.): International Perspectives on Citizenship, Education and Religious Diversity. London. [ Links ]

Zinn, D. & A. Keet 2010. Diversity and Teacher Education. In Sporre, K. & J. Mannberg (ed.): Values, Religions and Education in Changing Societies. New York: Springer. [ Links ]