Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.27 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Different children, equal citizens and a diverse team of teachers: a safe space for unique persons and equal citizens

Ina ter Avest

PhD (Children and God, narrated in stories). Utrecht University. Netherlands. ina.teravest@inholland.nl

ABSTRACT

'I see no differences between my pupils, I treat them all equal'. This sentence is frequently quoted - a statement that meets approval from most of the teachers and parents. However, a teacher who does not see any difference, won't be able to acknowledge the uniqueness of each child either. What remains is a classroom full of middle-of-the-road pupils, or - even worse - a classroom full of children of whom at least half of their identity is not visible. In my contribution I argue that it is the difference, the in-equal-ity, that has to be articulated in order to stimulate the development of an authentic worldview of pupils as future citizens in contemporary societies that are characterized by cultural diversity and subsequently different life orientations. Not only the difference between pupils, but even more so the diversity amongst teachers should be promoted to present to pupils a variety of role models as examples of good practice of (future) equal citizenship.

The collaboration with Cornelia Roux made me aware of the huge importance and relevance of Human Rights and more specifically Children's rights. So I start my contribution referring to the Convention on the Rights of the Child in which it is stated that every child has the right to be stimulated in spiritual, moral and social development, and has the right to enjoy the own culture, religion or language. The Vygotskian elaboration on the constructive role of contrasting in-equal-ities for the development of pupils is an important and inspiring source for our plea for 'teaching and learning in difference'.

Next to that I give a brief description of the multicultural character of the Dutch society and its consequences for citizenship education including children's rights. I will argue that included in 'freedom of thought, conscience and religion' is the right to learn from various religious and secular worldview traditions (cf. Morgan 2007); the right to be educated in difference. Awareness of difference stimulates development (Vyggotsky 1978). In a similar way the encounter with the otherness of 'the other' challenges the construction of an own authentic worldview.

Teachers as role models are of pivotal importance, creating a safe space and a rich learning environment to learn about and from differences in life orientations and from the encounter with 'the other' (Arendt 2004; Duyndam & Poorthuis 2005). I present an example of teacher behaviour showing in an RE class on citizenship education that 'to be different is just normal' (a vivid example of the child's right to be different/ unique), and 'living together: just do it!' (a vivid example of a teacher's attitude of openness towards 'the other').

I conclude with a plea for diversity in teams of teachers representing, acknowledging and actively tolerating cultural and religious diversity - as such exemplifying a safe space of human rights in vivo: teaching and learning in difference to become unique persons and equal citizens.

Keywords: children's rights, spiritual development, diversity, (in-)equality, encounter

Introduction

Doing research with teachers in classrooms characterized by diversity in a variety of ways, confronts the researcher with teachers' sayings about their pupils like: 'I love them all in an equal way', or 'They are all naughty darlings', or: 'Children are children, whether they are raised in China, in Brasil, in Turkey or in the Netherlands'. What teachers probably mean is that in their eyes all pupils have the same status of being a learner, that they as a teacher bear the same responsibility for the learning process of each and every child, that each pupil has the same right for good education.

Some fifty years ago teachers might have formulated it not in terms of national context, the country where children live ('whether they are raised in China, in Brasil, in Turkey or in the Netherlands), but in terms of religious socialisation, like: 'Children are children, whether they grow up in Protestant families or in Catholic families' . In the second half of the twentieth century the Dutch society was organised according to religious dividing lines in three so called 'pillars': a protestant, a roman catholic and a humanistic pillar; Holland was labelled as a 'pillarized' society. Children whose parents adhered to the protestant religious tradition would attend classes in protestant schools, be a member of a protestant sports club, their parents would read a protestant newspaper and be a member of a protestant church community. In an equal way children raised in a catholic family went to catholic schools and attain a membership of a catholic football club and children whose parents did not favour a religious socialisation at school would send their children to state schools and their children would participate in humanistic activities after school hours. This pillarized way of organzing the country was seen as a reasonable way of socializing, doing justice to the upbringing of the child. Article 23 of the Dutch Constitution facilitates and enables parents to realise this particular and one of the far reaching Children's Rights, that is: to educate and to be educated according to the worldview the parents adhere to. Whereas in the last decades of the twentieth century pillarization included a vivid religious community life in three separate circles, in the second decade of the twenty first century religious community life - since the 1980's and due to processes of secularisation and individualization - is not that vivid anymore and consequently the participation in the respective circles diminishes. The process labelled as secularization is held responsible for the decrease of commitment to religious communities; globalization is perceived as related to interculturalization, changing the Netherlands from a homogeneous society where 'diversity' is related only to religious difference, into a heterogeneous society, where 'diversity' is connected to gender, ethnicity, and religion. These days 'being different is just normal', whether the difference refers to a sexual identity, a mixed-race identity or an unaffiliated religious identity. Diversity is all over the place.

Equality and Equity

Diversity is all over the place, but this does not provide sufficient evidence of the valuation and appreciation of differences, and of the variety of sub- cultures in a diverse culture. In many diverse societies there is one dominant culture, to which children belonging to a variety of sub-cultures to a more or lesser extent have to adjust, assimilate or integrate (Walzer 1997: 98-112) . In the Netherlands, with amongst others a Moroccan, Turkish, Surinam, Ghanaian and Nigerian sub-culture, it is in the Dutch culture that all other cultures are expected to integrate (Eldering 2002: 27-59; Scheffer 2000; 2007). Policy makers talking about social cohesion and integration are pointing to the foreigners' lack of knowledge of the Dutch culture and language. Talking about the participation of persons with a migrant background, amongst policy makers this is said to be a matter of equal representation in positions and jobs in the public domain. Each group, each culture, religion and gender for example should be represented in equal numbers and have the same status. Others however are of the opinion that fairness requires special treatment for groups are culturally or religiously different or who are otherwise disadvantaged; these groups should be allowed a preferential treatment (positive discrimination, motivated by striving at equity). Others again suggest that - in order to arrive at the same position as people from a majority group - persons from a minority group should be offered extra possibilities and funding for catching up with a majority status. With regard to a minority with an economic and educational disadvantage and different cultural habits, toleration has to be learned - for the majority to develop an attitude of tolerance and a practice of toleration with regard to a minority's habits and points of view; for the minority to persist in their viewpoints and accept a position of being tolerated. Difference makes toleration necessary; toleration makes differences visible and liveable (Walzer 1997: xii).

Diversity

Differences are at the heart of the concept of diversity. Everybody knows diversity has 'something' to do with in-equal-ity, but there is discussion about the interpretation of the concept of 'diversity'; amongst scholars it appears to be a highly contested concept. In education diversity in the first place points to differences in pupils' characters and their learning styles (Bakker 1999: 59). To start with, these differences were interpreted as hindering the study progress. In a group of pupils, where one or two of the whole group need far more teacher explanation in order to understand their Mathematics task, teachers fear that for those with 'high potential' the fun of Mathematic is soon fading away. However, in the Russian psychology on teaching and learning, differences are not perceived as hindering the learning process, but on the contrary as enriching the process for the pupils involved. As early as 1962 Vygotsky in Theory in Thought and Language wrote about learning styles and developmental processes, elaborated thereupon in 1978 in pointing to the consequences of differences in learning processes, that is on the constructive role of contrasting in-equal-ities on study progress. In the Vygotskian psychology on learning the role of language in the relation between the teacher-educator and the learner is central. In Vygotsky's view the role of the context and more concrete the role of the teacher-educator is crucial in the process of mastering tasks and in the acquisition of knowledge. Learning according to Vygotsky is not an individual but a relational process. Key concepts in his theory are the 'zone of proximal development' and 'scaffolding'. These concepts describe the tasks

the child cannot master alone but is able to do with the assistance of adults and more accomplished peers (who represent the zone of proximal development) become independently achievable through a system of support (scaffolding), which gradually abdicates responsibility to the child (Shweder 2009: 121, 562).

The difference with 'adults and more accomplished peers' is crucial in the stimulation of a child's development. Following the Vygotskian line of thought development cannot take place but for the presence of diversity.

Although Vygotsky saw the learning progress as a culture-related process, his theory is coined as a social-contextual theory of development, the cultural aspect - in the sense of culture-related differences in habits, practices and subsequent value orientation - is less covered. These days - in plural societies - research has to focuses on progress in relation to mutual understanding and toleration of value-oriented ways of doing. The concept of 'Bildung' anew comes to the fore, be it in a slightly different way than it was meant originally by Wilhelm Von Humboldt in the 19th century. 'Bildung' in the 21st century refers to a process of inculturation, including the competency of participatory citizenship in a society that is characterized by diversity -with regard to ethnicity, gender, worldview and religion (to name but a few). We will come back to this below.

Education in a Diverse Context

In the Netherlands people with different ethnic, cultural and religious backgrounds live together, amongst others due to economic and political migration. As a result the Dutch population these days is a mixture of native Dutch people and people with a migrant background, referring to persons of whom one or both parents are born in one of the other European countries or in a non-Western country. People with a migrant background can be first generation migrants (they themselves arrived at the Netherlands), either to participate in the labour force as a so-called 'guest worker', or as refugee. Their children, born in the Netherlands, are categorized as second or third generation migrants.

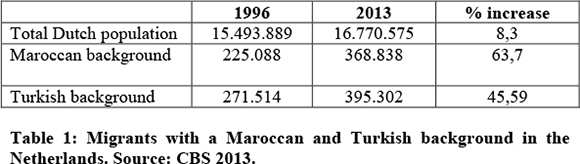

To give an impression of the change in the composition of the Dutch population, and subsequently the increase in ethnic and religious diversity, we present the statistics of 1996 and 2013 below.

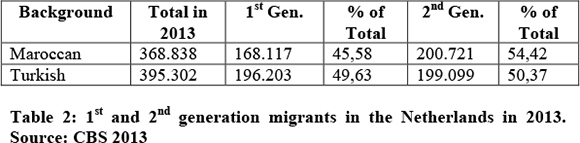

In the next table we split the number of persons with a Maroccan or Turkish background living in the Netherlands in 2013 in 1st and 2nd generation persons.

The increase in cultural and religious diversity as a result of the growth of people with a migrant background in the Netherlands, in 1985 resulted in the introduction of a new school subject, called 'Geestelijke Stromingen' (Spiritual Movements), aiming at informing all pupils in primary education about different religious and secular worldviews. This subject is compulsory in all schools, be it Protestant, Catholic or State schools. In addition Protestant and Catholic schools socialize their pupils in the respective denomination of Christianity by starting every day with prayer and a morning circle including telling Bible stories, and celebrating the Christian festivals like Christmas and Easter. In state schools it is possible for pupils on request of their parents to attend lessons in Christianity; these lessons are characterized by a confessional or oecumenical approach. The pillarized educational system, including the implementation of Christian religious lessons on a voluntary base in state schools, responded to one of the core elements of Human Rights Education, in particular to the right of the child to be educated according to the religious or secular worldview of the parents (which points to the duty and responsibility of parents to socialize their child in the worldview they adhere to, including the socialization in school). This was seen as a reasonable way to socialize children in their own religious culture. This segregated way of religious education was organized from the perspective of equity of treatment: teaching and learning each child what was needed for that child to adjust to the religious or secular circle into which s/he was born.

Today, what is called the post-pillarized era, socializing in the religious or secular worldview parents adhere to does not meet the requirements of citizenship in a plural society anymore. That is the reason that in 2006 the government introduced a new school subject called 'Burger-schapsvorming' (Citizenship Education). This subject aims at the development of competencies of participatory citizenship, including respect for the otherness of 'the other'. From an approach of 'learning about diversity (in Spiritual Movements) the educational approach changed into a 'learning from' diversity (Citizenship Education).

Learning With and From Each Other

At the Utrecht University the pedagogue Trees Andree, in 1991 in the public lecture at the start of her professorship challenged teachers to focus in their educational activities on the development of self-awareness and respect for otherness, in order to become competent in dialogicality - in Andree's view preconditional for good citizenship. Her pedagogical strategies are characterized by 'togetherness'. Andree prefers to talk about 'learning with and from each other' (Andree & Bakker 1996; Andree & Bakker 1997), as such including 'the other' as a partner in conversation and giving way to the possibility of the construction of new knowledge based on the experience of encounter (see also Hull 1991; Ter Avest 2006). Andree's ideas are elaborated upon by her successor at the Utrecht University, the theologian and scholar in educational sciences Cok Bakker and by the pedagogue Siebren Miedema (VU University) and concretized in supporting the idea of religious education as a compulsory subject for all pupils at all schools (Miedema & Bertram-Troost 2006).

Bakker underpins his plea for religious education for all pupils refering to Braster's 'chameleon-hypothesis' (1996). Braster states that a public school's identity is hardly ever strictly neutral - as might be expected from a 'pillarized' perspective. In Braster's analysis, only a quarter of the researched public schools represents an 'unbiased market-place' of philosophies and religions. The majority of public schools adapts largely to contextual factors, e.g. the context of the school (neighbourhood) and as a result of that the composition of the schoolpopulation. Related to the situatedness of schools, Braster distingishes public schools with many migrant children, making multiculturality a core issue, or a public school in a conservative Christian context (as in the so called 'Bible Belt' in the Netherlands), that pays a lot of attention to Christianity and national cultural festivities. In this respect it is interesting to mention recent research confirming this 'chameleon-hypothesis' for religious affiliated schools. A Protestant school in the inner-city of Rotterdam appears to differ profoundly from a Protestant school in the Veluwe-region, which is part of the Dutch 'Bible Belt' (Bakker 2004). These differences show similarities with the differences in identities of public schools. This shows that nowadays the pillarized structure of the Dutch educational system is heavily under debate (Ter Avest, Bakker, Bertram-Troost & Miedema 2007; Ter Avest & Miedema 2010). These societal developments support Bakker's plea for a school subject aiming at every pupil's development of an authentic life orientation, taking its starting point as the world the child lives in. Bakker concretizes this plea in a proposal for curriculum innovation with the implementation of a subject called 'Levon for all ('LEVensbeschouwelijk ONderwijs voor alle leerlingen'; Bakker 2004; Bakker & Ter Avest 2013).

Whereas Bakker focuses primarily on the development of the unique person, Miedema's focus is on the development of equal citizens. Miedema speaks of 'Levensbeschouwelijk Burgerschapsvorming' (Religious Citizenship Education; Miedema & Bertram-Troost 2008; Ter Avest & Miedema 2010). Miedema is of the opinion that the subject 'Geestelijke Stromingen' and 'Burgerschapsvorming' should be brought together in a new school subject called 'Levensbeschouwelijk Burgerschapsvorming' (Religious citizenship Education), in line with Andree's pedagogical strategy of 'learning from and with each other'. This pedagogical strategy allows for getting to know about the other, and co-operative learning with the other and from each other's cultural and religious background, including the variety in views on 'the good life' and 'good education' (cf. Sandel 2010: 288 ff).

In a recent interview Harvard Professor Michael Sandel states that since we are afraid to impose our values upon others, or other's values to be imposed upon us, we try to be as neutral as possible in the public domain. We ask people to leave their moral convictions at home before entering the public domain. Although this is understandable, it is - according to Sandel - not the right thing to do. It decreases the public debate. As a consequence the resulting empty space might be taken by intolerant convictions of fundamentalists (interview with Sandel by Bas Heine 2013). The 'learning from and with each other' -approach as favoured by Andree and later by Bakker as well as by Miedema prevents the upcoming of fear for 'the other' by enabling pupils to recognize similarities as well as differences. Pupils are taught and learn to tolerate the otherness of 'the other' as well as to be tolerated, and by doing so they learn to live together in their private life as well as in the Dutch public domain characterized by cultural and religious diversity; education in diversity.

These days some people argue that religion and subsequently religious practices should be restricted to a family's private life; others are of the opinion that although religion is part and parcel of a person's private life, at the same time its contribution to a person's positionality in the public space is immense (Van de Donk et al. 2006; Miedema, Bertram-Troost & Veugelers 2013). It is in terms of this latter aspect that we join Bakker and Miedema in their plea for a school subject answering the right of each child to be educated according to the religious or secular worldview as this is lived by the parents, while at the same time responding to society's need for citizens competent to tolerate and be tolerated, and to live together in a community characterized by diversity (cf. Bakker & Ter Avest 2013).

Encounter in Diversity

It is the teacher's pedagogical task to teach and be a role model of the twin principles of freedom of belief and tolerance of the belief of others. This task is directly related to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

In the second half of the last century something significant has been accomplished with the protection of the right to practice and to teach one's (religious or secular) worldview. In 1948, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, religion was referred to in Article 18:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and, in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

In 1959, in the Krishnaswami Report, a list of practices is mentioned that concretise one's religious beliefs, like worship, pilgrimage, marriage, as well as dissemination practices and training of teacher-educators. In 1966, in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, article 18 mentions the liberty of parents 'to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions'. Complementary to article 18 in the previous mentioned Covenant, in the articles 27 - 30 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child it is stated that every child has the right to be stimulated in spiritual, moral and social development, and has the right to enjoy the own culture, religion or language. 'The own culture' however is replaced by a general classroom culture the moment the child enters school.

The introduction of the Rights of the Child means that not only should the teacher look for sameness in her pupils ('I see no differences between my pupils, I treat them all equal') and solidarity with others, but even more so should teachers articulate differences and the alterity of each participant in multicultural, multiethnic and multireligious classrooms (cf. Wright 2001; 2004) and accordingly approach each pupil on grounds of social justice and equity. In all classes 'a rich and plural array of religious "subject matter" in the form of religious frames of reference, models, practices, rituals and narratives' (Miedema and Bertram-Troost 2008) are represented and as such fulfil a necessary precondition for pupils to learn with and from each other.

Encountering the other can be a surprising experience. Not because 'I' recognise myself in 'the other', but even more so because 'I' meet 'myself', meeting the other. A necessary prerequisite to meet oneself is to open up for the other, to develop an attitude of curiosity. Curiosity to new things that are different from what the child is used to at home. Strangeness, however, can be met with anxiety but also with fear, or with the wish of a child to assimilate with the other so that there is no strangeness anymore. It also may trigger the wish to colonize the other, stating that 'the other is just like me, just a bit different' (Levinas 1994). Then the other is not alien anymore, but familiar and to some extent the same as I am, which ends up in the disappearance of the uniqueness of the other. Strangeness can also raise curiosity. Whatever the feelings, the confrontation with strangeness needs reflection. Reflection upon the difference and what this difference means with regard to one's own identity, one's own comfort zone, one's own feelings of homeness. The task of the teacher is to scaffold the child in the process from possible feelings of anxiety and fear, to feelings of curiosity, a pedagogical approach labelled 'guided openness' (Ter Avest 2003; 2009) and 'cultivating strangeness' (Streib 2006). Encountering 'the other' is a gift to the child, since such a meeting results in conscientization of one's own positionality. As such the encounter with 'the other' is the basic right of each child.

Hosting Diversity

The responsibility for creating a learning environment of encounter can be clarified with the metaphor of a host, answering in an appropriate way to the guest, 'the other', entering into a house. Inviting guests to enter the safe space of the personal sphere of the private domain means that the host has to open him or herself to the guests. In order to 'open up' there must be something to 'open'. The same is true for the guests: in order to leave the public domain where persons are equal citizens, and bring in their uniqueness in the new (and alien) private domain of 'the other', they must have something that they bring with them. The teacher as a host has to create a hospitable, welcoming and safe environment in classes - literally a safe space. Teachers should avoid creating a kind of sameness, an arbitrary solidarity, but instead should open up to diversity. The contrasting 'colours' of all unique pupils will result in the deepening of each individual colour (Ter Avest 2007). The deepening of one's own colour, the continuous development of one's own (religious or secular) worldview, is one of the children's rights, a civil right - being future citizens. When schools do not provide a sense of such a base and are not directive for their pupils, they make them vulnerable to powerful agendas like the economic agenda, or the agenda of the market and advertisements, resulting in the devaluing of the school community and regression into an empty space that might be filled by the intolerant convictions of fundamentalists.

Diversity on the Surface

Teachers as role models are of pivotal importance - as professionals trained to create a safe space and a rich learning environment to learn about and from differences in life orientations and for the encounter with 'the other'. In teacher behaviour it is expected that it is visible that 'to be different is just normal' (a vivid example of the child's right to be different/ unique), and 'living together must be done - by you!' (a vivid example of a teacher's attitude of openness towards 'the other').

Living together starts with the willingness to open up for the other, to respect the alterity of the other and to tolerate the other's uniqueness. However, these theoretical concepts are difficult to observe, hard to notice and not easy to track down in concrete behaviour. It needs reflection and recognition, and judgement inspired by a secular or religious worldview or tradition (Todd 2007). Most of all it needs willpower to live accordingly, to bring in-spiration out onto the surface of everyday actions.

Below we present an example of 'good practice': a teacher who makes clear enough her implicit and invisible inspiration and motivation for equality in learning opportunities, and equity regarding the unique learning processes of each pupil involved; clear enough for intangible concepts like equality and equity to be noticed and experienced by all pupils (Ter Avest 2009).

Making a Difference

Miss Helena is employed by an Islamic primary school in one of the medium-sized towns in the country of the Netherlands. The pupils have a diverse cultural (mainly Turkish and Maroccan) and socio-economic background; the lowest social-economic layer is over-represented. Her pupils are the ages of 10 - 11 years; there are 24 of them in her class, 13 girls and 11 boys.

Aware of the divisions in society and thus the importance of children learning to get on with one another, Miss Helena this morning focuses her lesson on 'working together'. She starts the lesson with an exercise in 'looking carefully', in order to cultivate sensitivity to both similarities and differences. She starts with this so that she can come back to it later in connection with similarities and differences in the qualities of people who have to work together. In the first exercise the children pair off, then each pair takes an orange from a bowl and looks at it carefully so that later, when they have put it back in the bowl, they can recognize that particular orange as their own. When each pair has taken a good look at their orange and put it back in the bowl, she asks one of the children to mix up the oranges. Then she invites one of each pair of children in turn to retrieve their own orange. 'Was it easy', she asks, 'to pick out your own orange?' Then she asks her pupils to show they went about picking out their own orange from so many. One pupil says: 'Miss, ours had a slightly different colour'. Another pupil states: 'With ours it was the shape, Miss, that made me recognize our own orange' . And again another pupil says it was the size that was the distinguishing factor.

Miss Helena continues with her lesson. 'We have just looked at similarities and differences in oranges, now we're going to look at similarities and differences between people' . She invites the children to do the following exercise: two children sit back to back on the floor, joining hands behind their backs, with their legs stretched out in front of them. What they have to do is to stand up in one smooth movement, ending up standing back to back, without letting go of each other's hands. Two boys are the first to try. Their first attempt is not successful and they end up rolling over the floor in fits of laughter. Then two girls want to give it a try. Silently the children watch in suspense, waiting to see of the two girls now sitting inside the circle will be able to do it. The girls sit very calmly, count to three and stand up together in one movement. Cries of surprise and admiration are heard in the circle. Then Miss Helena decides to make the exercise a bit more challenging. She introduces the next step as follows:

'Now usually at home and often at school as well, when you have to do something together and have to choose someone, a boy will nearly always choose a boy and a girl will nearly always choose a girl. That's what just now happened, and it's comfortable. But just imagine: you're a girl and you have to work together with a boy; or you're a boy and later in an office you have to consult a girl every day. Then she puts the question to her pupils: 'Who wants to try to work together like that? Who of the girls doesn't mind trying to do the exercise with a boy? Who of the boys would like to give it a try with a girl? Silence. Nobody responds to this question. 'Nobody at all?', is the conclusion of the teacher. 'Then let's try something else' - and she invites a little boy and a tall boy into the circle. The boys sit down, and try to stand up. They don't succeed and there is laughter in the circle of pupils. 'Have one more go', says the teacher. The boys talk over their shoulders, then push off against each other and then stand up, back to back. 'Very well done!'. The teacher compliments the boys on this achievement. 'Working together is hard when one is taller than the other, when you're different. Everybody clap hands! You two did really well. This was hard, because you are not equal, you differ in height and strength. It helped that you discussed your strategy!' (adapted from: Ter Avest 2009: 21-23).

This teacher apparently knows about the culture related family habits. She practices a provocative pedagogical strategy (Ter Avest & Bertram-Troost 2012) in her teaching, stimulating sensitivity for equality and 'living in difference' in her classes. Concluding from this teacher's behaviour each and every pupil is stimulated in her or his social, cultural and religious development in her or his own way, irrespective of the pupil's family background. This teacher is a role model, practicing the concepts of equality and equity with her pupils and as such creating a safe space for unique persons and equal citizens in the future. To make such a strategy even more effective a team of teachers should consist of people with different cultural and religious backgrounds, so that in their everyday consultations they present living examples of living together in difference. I plead for diversity in teams of teachers representing, acknowledging and actively tolerating cultural and religious diversity (Brighouse 2006) - as such an example of human rights in vivo. A safe space in a diverse team of teachers is preconditional for the encounter with 'the other' with and from whom to learn to live together in difference without becoming indifferent.

In the above given example of 'good practice' we see how identifying and articulating a difference is used by a sensitive teacher, in a safe space, to stimulate pupils' will power to give it a try to work together despite differences, even making use of their differences. Starting with the characteristics of oranges, and moving over to people's qualities this teacher helps her pupils in the transfer of experiential knowledge. She is good at scaffolding her pupils towards the zone of proximal development. By questioning self-evident habits ('Now usually at home and often at school ...') she invites her pupils to open their eyes for different customs, and paves the way to construct new knowledge. Anxiety changes into curiosity - not for all the pupils at the same moment! Learning processes do differ for both pupils and their teachers. Difference is all around as is the need for reflection on equality and equity amidst diversity.

References

Andree, T. & C. Bakker 1996. Leren Met en Van Elkaar. Op Zoek Naar Mogelijkheden voor Interreligieus Leren in Opvoeding en Oonderwijs. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum. [ Links ]

Andree, T. & C. Bakker 1997. Feesten Vieren in Verleden en Heden: Visies vanuit Vijf Wereldgodsdiensten; Leren Met en Van Elkaar. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. 1999. Politiek in Donkere Tijden. Essays over Vrijheid en Vriendschap. Amsterdam: Boom. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. 2004. Vita Activa. Amsterdam: Boom. [ Links ]

Bakker, C. 1999. Diversity as Ethos in Intergroup Relations. In Chidester, D., J. Stonier & J. Tobbler (eds.): Diversity as Ethos; Challenges for Interreligious and Intercultural Education. Cape Town: Institute for Comparative Religion in South Africa. [ Links ]

Bakker, C. 2004. Demasqué van het Christelijk Onderwijs? Over Onzin en Zin van Een Adjectief. Public lecture at the start of his professorship, Utrecht University. [ Links ]

Bakker, C. & I. ter Avest 2013. Life Orientation in Public Schools. Presentatie at Annual REA Conference, Proceedings REA Conference Boston. [ Links ]

Braster, J.F.A. 1996. De Identiteit van het Openbaar Onderwijs. [The Identity of Public Education.] PhD thesis. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff [ Links ]

Brighouse, H. 2006. On Education. London/New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group [ Links ]

Donk, van de W.B.H.J., A.P. Jonkers, G.J. Kronjee & R.J.J.M. Plum (red.) 2006. Geloven in het Publieke Domein. Verkenningen van een Dubbele Transformatie. Amsterdam: University Press. [ Links ]

Duyndam, J. & M. Poorthuis 2005. Kopstukken Filosofie: Levinas. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij Lemniscaat. [ Links ]

Eldering, L. 2002. Cultuur en Opvoeding. Interculturele Pedagogiek vanuit Ecologisch Perspectief. [Culture and Education. Intercultural Pedagogics from an Ecological Perspective.] Rotterdam: Lemniscaat. [ Links ]

Heine, B. 2013. 'Breng het morele debat weer tot leven'. NRC/HB, 31 mei 2013. [ Links ]

Hull, J. 1991. Mishmash: Religious Education in Multi-cultural Britain: A Study in Metaphor. Birmingham: University of Birmingham. [ Links ]

Miedema, S. & G. Bertram-Troost (ed.) 2006. Levensbeschouwelijk Leren Samenleven: Opvoeding, Identiteit & Ontmoeting. [Learning to Live Together in Religious Diversity: Education, Identity & Encounter.] Zoetermeer: Uitgeverij Meinema. [ Links ]

Miedema, S. & G. Bertram-Troost 2008. Democratic Citizenship and Religious Education: Challenges and Perspectives for Schools in the Netherlands. British Journal of Religious Education 30,2:123-132. [ Links ]

Moran, G. 2006. Religious Education and International Understanding. In Bates, D., G. Durka & F. Schweitzer (eds.): Education, Religion and Society. Essays in honour of John M. Hull. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

Levinas, E. 1994. Tussen Ons. Essays over het Denken aan de Ander. Baarn: Ambo. [ Links ]

Miedema, S., G. Bertram-Troost & W. Veugelers 2013. Onderwijs, Levensbeschouwing en het Publieke Domein. Inleiding op het Themanummer. Pedagogiek 32,2: 73-90. [ Links ]

Roux, C. 2013. Safe Spaces. Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts. Rotterdam/ Boston/ Tapei: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Sandel, M.J. 2010. Rechtvaardigheid. Wat is de Juiste Keuze? Kampen: Ten Have. [ Links ]

Scheffer, P. 2000. Het Multiculturele Drama. [The Multicultural Disaster.] NRC Daily Newspaper January 29. [ Links ]

Scheffer, P. 2007. Het Land van Aankomst. [Country of Destination.] Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij. [ Links ]

Sheder, R.A. (ed.) 2009. The Child. An Encyclopedic Companion. Chicago and London: the University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Streib, H. 2006. Strangeness in Inter-religious Classroom Communication: Research on the Gift-to-the-Child Material. In Bates, D., G. Durka & F. Schweitzer (eds.): Education, Religion and Society. Essays in Honour of John M. Hull. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I. 2009. Dutch Children and their 'God': The Development of the 'God' Concept among Indigenous and Immigrant Children in the Netherlands. British Journal of Religious Education 31,3: 251-263. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I. (ed.) 2009. Education in Conflict. Münster/ New York/ München/ Berlin: Waxmann. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I. 2006. Verandering in Ontmoeting. Van Kennis Nemen van Naar Kennis Maken met Tradities. In Miedema, S. & G. Bertram-Troost (eds.): Levensbeschouwelijk Leren Samenleven. Zoetermeer: Uitgeverij Meinema. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I., C. Bakker, G. Bertram-Troost & S. Miedema 2007. Religion and Education in the Dutch Pillarized and Post-pillarized Educational System: Historical Background and Current Debates. In Jackson, R., S. Miedema, W. Weisse & J-P. Willaime (eds.): Religion and Education in Europe: Developments, Contexts and Debates. Münster/New York/München/Berlin: Waxmann [ Links ]

ter Avest, I. (ed.) 2011. Contrasting Colours. European and African Perspectives on Education in a Context of Diversity. Amsterdam: Science Guide/Gopher bv. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I. (ed.) 2009. Education in Conflict. Münster/ New York/ München/ Berlin: Waxmann. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I. & S. Miedema 2010. Noodzaak tot Recontextualisering van Onderwijsvrijheid vanuit (Godsdienst)Pedagogish Perspectief. Tijdschrift voor Onderwijsrecht & Beleid 1-2: 77-88. [ Links ]

ter Avest, I., G. Bertram-Troost & S. Miedema 2012. Provocative Pedagogy, or Youngsters Need the Brain to Challenge Worldview Formation. Religious Education 107,4: 356-371. [ Links ]

Todd, S. 2007. Teachers Judging without Scripts, or Thinking Cosmopolitan. Ethics and Education 2,1:25-38 [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. [1962] 1992. Thought and Language. Cambridge/ Massachusetts, London: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Vygotskty, L. 1978. Cultuur en Ontwikkeling. Meppel: Boom. [ Links ]

Walzer, M. 1997. On Toleration. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Wright, A. 2001. Religious Education, Religious Literacy and Democratic Citizenship. In Francis, L.J., J. Astley & M. Robbins (eds.): The Fourth R for the Third Millennium. Education in Religion and Values for the Global Future. Dublin: Veritas Publications. [ Links ]

Wright, A. 2004. Religion, Education and Post-modernity. London: Routledge. [ Links ]