Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal for the Study of Religion

On-line version ISSN 2413-3027

Print version ISSN 1011-7601

J. Study Relig. vol.27 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Mapping the curriculum-making landscape of religion education from a human rights education perspective

Shan Simmonds

Curriculum Studies. North-West University. Potchefstroom Campus. Shan.Simmonds@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

With the advent of democracy in South Africa, religious education became a contested topic in the education sector. Contestation stemmed from the desire to embrace religious plurality rather than Christian National Education (CNE) that dominated the curriculum pre-1994. This contestation initiated the reconceptualisation of religion in curriculum-making. Together with other scholars, Roux, a scholar-activist, has played a seminal role in conceptualising religion in the curriculum as religion in education (RiE) and more recently, religion and education (RaE). In disrupting the boundaries of religion, she has also made human rights the departure point for engagement with RaE. The concomitant blurring of the boundaries between religion education (RE) and human rights education (HRE), has made it necessary to explore the complexities of the foundations of human rights. In response, this article uses Roux's work to extend the argument by exploring the possibilities of human rights literacy (HRLit) in curriculum-making for HRE. To conclude, this conception of HRLit is considered juxtaposed to Roux's most recent scholarship, which interrogates gender as a specific position within HRE. In engaging with this scholarship, this article takes a critical HRLit perspective so as to embrace Roux's work through an alternative theoretical lens.

Keywords: curriculum-making, religion education, human rights education, human rights literacy, gender

Curriculum-making in South Africa: Religion Education since 1994

Prior to her professional career, which commenced in the late 1970s, Cornelia Roux's upbringing in a multi-denominational family and her education trajectory within Christian National Education (CNE) inspired her activism for and scholarship in religion education (Roux 2012a). In curriculum development in South Africa since 1994, her scholarship has initiated and shaped three prominent trends in reaction to curriculum reform and education ideologies: critique of religious education, religion in education (RiE) discourse and religion and education (RaE) discourse. She has been a leading contributor to the paradigm shifts in this discipline.

Critique of Religious Education

CNE underpinned the previous education dispensation, pre-1994. It was viewed as the appropriate foundation on which to build religion since it was the belief and value system of the majority of South African citizens. Infused with political ideology, religious education comprised the curricula of Bible Education, Religious Instruction or Right Living (Roux & Du Preez 2005). For Makoella (2009:71) the Christian dogma underpinning the curriculum, in fact, 'had nothing Christian about it' as it entrenched racial hatred through a separate and unequal schooling system while at the same time ignoring what were regarded as minority religious and beliefs systems. It was only when the democratically-elected political party came into power post-1994 that the doctrine of CNE was removed from curriculum-making.

With the advent of democratic governance in South Africa, knowledge of different beliefs and values became an integral part of the formal, national school curriculum (Roux 2012a). This more democratic curriculum post-CNE, was principally informed by South Africa's core constitutional values namely, freedom of religion, conscience, thought, belief and opinion, equity, equality, and freedom from discrimination (Chidester 2002:91), and came to be referred to as RE (religion education) (South Africa 2003). However because Religion Education was premised on being both a formal academic subject and an observation of diverse religious practices (Potgieter 2011:402), Roux is one of the scholars that prefer the concept RiE as opposed to RE.

Religion in Education (RiE) Discourse

Advocates for RiE, rather than RE, base their argument on the view that RiE more appropriately meets the wider aims that RE espouses (Roux & Du Preez 2005:274). Roux (2012a:140) argues that the main goal of RiE is to bridge the gap between curriculum development, subject knowledge and classroom praxis. Such an approach entails

... developing philosophical ideas and theories on religion and education; carrying out empirical studies and research involving educators, students and learners; developing curricula; and exploring innovative methodologies for teaching and learning of religion in education (Roux & Du Preez 2005:274) .

Deeply inscribed in this conception of RiE is the need to embrace the perceptions, experiences and reflections of educators, students and learners through a curriculum space where their difference and contrasting ideas are deliberated (Roux 2012a:140). The classroom therefore becomes a meeting place where educators, students and learners from diverse religions and cultures come to learn about their own and others' beliefs and cultural practices.

Religion and Education (RaE) Discourse

RiE underpinned curriculum-making for almost the last two decades, but with the most recent curriculum reform that was conceptualized in mid-2009 and began to be implemented in 2012 (South Africa 2010), a shift was necessitated. In this currently implemented curriculum called CAPS (Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement), religion is on the periphery as it is no longer a subject on its own but rather positioned 'within other subject matters (e.g. human rights education, social justice and values)' (Simmonds & Roux 2013:79). By broadening the composition and boundaries of RiE, the broader social milieu in which learners exist is acknowledged, and this gave rise to what Roux termed RaE (Simmonds & Roux 2013:80).

As a result, religion has not only been a factor in conceptualizing religious and cultural belief and value systems in the national curriculum. The emphasis on teaching religion through human rights, social justice and values, has meant that a human rights education discourse has been etched into the curriculum. This discourse has initiated a novel approach to curriculum-making, one that needs to consider the attributes of HRE.

The arguments in the rest of this article are based on a HRE perspective as these reflect my own position. Therefore my intention is to contribute to Roux's conception of RaE and its discourse by:

- elaborating on the boundaries between RaE and HRE;

- exploring the possibilities of curriculum-making underpinned by HRLit; and

- responding to Roux's most recent scholarship on gender-based research from a critical HRLit perspective.

Disrupting the Boundaries of Religion: HRE

Roux's scholarship (Du Preez, Simmonds & Roux 2012; Roux, Du Preez & Ferguson 2009; Roux, Smith, Ferguson, Small, Du Preez & Jarvis 2009; Roux 2010) recognizes that RE forms part of curriculum-making on the periphery of disciplines such as HRE. Thus it requires another discourse to inform curriculum-making. Roux's (2010:1000) view that HRE has the potential to promote RaE stems from the fact that the formal, national curriculum is firmly based on the human rights democratic principles enshrined in the Constitution (South Africa 1996). To elaborate, HRE and how it operates within the education domain will be explored. In addition, Dembour's (2010) four schools of human rights which underpin HRE are presented so different interpretations of HRE and how these might shape RaE discourses can be considered.

The Nomenclature of HRE in the Education Domain

Keet (2007:50-52) describes the development of HRE in a three-phase model. This model comprises a pre-1947 HRE phase, the formalization of HRE phase and the proliferation of HRE phase. These phases illustrate that HRE is not a new concept as ' educational efforts and teachings that center around civic, civic-mindedness, democracy, justice and governance; and law, human rights, duties and responsibilities' have been part of education systems directly or indirectly, even before the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (Keet 2007:51). The shifts in HRE post-1947 demonstrate how HRE became part of the formal curriculum, in some countries sooner than others, through different interpretations and methods. For Flowers (2003:1), Mihr (2009:179) and Tibbitts (2002:160), HRE was a response in the late 1980s to the end of the Cold War. Others see HRE as emanating from joint endeavours by the United Nations Organization (UNO) and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to develop a tool to promote antinuclear, peace, moral and citizenship movements (Keet 2007:64; Nieuwenhuis 2007:30). The decade after the Cold War resulted in the negotiation and ratification of numerous international and national human rights treaties, government policies and private initiatives, which are reflected in the formalization and proliferation of HRE phases (Keet 2007). Since this time HRE has had various 'face lifts' as part of its continuous development (Simmonds 2012). Mihr (2004:9) elaborates:

... HRE is more sustainable than all preceding peace, tolerance and anti-bias teaching concepts and . we should learn from the misinterpretation and short term impact of re-education, civic-education and peace-education in the past, giving HRE its own notion. HRE is more than it aims to teach all people, regardless of their citizenship, ethnic background, legal status or if they have been former enemies and combatants.

As Mihr (2004:9) points out, HRE as a means of sustainability further highlights its ability to change and adapt to the current, prominent or relevant situations at any particular time and/ or in any context. In addition, the underlying desire for HRE to 'teach all people' underlines its association with the UDHR 1948 and related constitutions. These are manifest reasons for the integration and infusion of human rights into education.

Another point that has been made is that HRE has provoked a ' rights revolution' (Keet 2009:216) in education institutions that has impelled educational thinking in South Africa, and globally, towards a different interpretation of HRE, namely education as a right, or, a rights-based approach to education, HRE and human rights in education in particular. Invested in each of the priorities mentioned by Keet (2009) lies the central aim of the 1948 UDHR namely to protect the integrity and dignity of human beings. It is vital for the various HRE stances to be understood as a means of clarifying the dimensions of HRE, positions that are adopted, meanings that are constructed and/ or arguments that are made. This requires an engagement with what HRE could entail within an education domain.

Education Domain

HRE emerges from and finds common ground with education domains such as: Democracy Education, Peace Education, Conflict Resolution Education, Civic Education, Citizenship Education, Political Education, International Education, Global Education, World Education, Moral Education, Environmental Education, Development Education, Religion Education, Multicultural Education and Anti-racism Education (Keet 2007:188; Kiwan 2005; Kusy 1994:386; Lohrenscheit 2002:179; Mihr 2009:181; Tibbitts 2002:162). HRE thus sources meaning from broader concepts such as human rights, democracy, morality, social justice, peace, politics, equity, economics and citizenship. Within these broader concepts, there are specific concepts such as religion, class, gender, race, values and age. Keet (2007:47) states that 'the multitude of topics to be covered by HRE ... is probably the primary reason why HRE has taken on so many different related forms, each informed by particular theoretical assumptions about the conceptual structure of HRE'.

Fritzsche (2008), Gearon (2012), Keet (2007), Lynch, Modgil and Modgil (1992), Osler (2005), Suarez and Ramirez (2004), Tibbitts and Fernekes (2011) and Tibbitts and Kirchschlaeger (2010) provide in-depth and descriptive accounts of the definitions of the education domains in relation to HRE. These accounts reflect the view that although education domains 'are disciplines with their own histories and conceptual configurations' (Keet 2007:211), they are often regarded as ' shar[ing] many common features' (UNESCO 2011:43), in 'close relationship' (Fritzsche 2008:40) and synonymous with HRE.

It is a universal phenomenon that within these education domains HRE is a ' central, core or important pedagogical configuration' (Keet 2007:188). However, within each of these conceptual frameworks, there is a particular understanding of HRE (UNESCO 2011; Simmonds 2013). Thus HRE has epistemological foundations in many different frameworks and is faced with the possibility of having no specialised epistemology. Tibbitts (2002:169) elaborates on this stance, arguing that HRE faces the possibility of being regarded as a collection of interesting and discrete programmes and not an established field. It can also be argued that HRE becomes diluted in education contexts because it is spread across and between all conceptual frameworks to the extent that its ontological and epistemological foundations are absent, superficial and/ or limited (Keet 2007; Simmonds 2013). However, the multiplicity and complexity of HRE may also be seen as a strength rather than a limitation.

Concerted attempts to define HRE have been made in other domains such as the political and social (Simmonds 2013). However, as Flowers (2003:1) explains, 'a definition is elusive because today such a variety and quantity of activity is taking place in the name of HRE' . Moreover, 'HRE defies definitions because its creative potential is far greater than we can imagine' (Flowers 2003:17). For the present, it may be more valuable to embrace its diverse meanings. Rather than become overwhelmed with questions pertaining to 'What is in the name of HRE?', answers to questions such as 'What human rights stances could underpin HRE?' and 'How would different human rights stances influence HRE curriculum-making for RaE?' should be sought.

These questions prove significant when mirrored against Keet's (2007:206) statement that:

... it is the inability within the HRE field to reflect on the conceptual assumptions that underpin its pedagogical practices that renders HRE theoretically and pedagogically uncritical.

Keet's (2007) statement echoes the need to embrace human rights stances invested in HRE as a way of thinking laterally about it. In doing so, the UN Decade for Human Rights Education, 1995-2004 (UN 1997) can be acknowledged as one of the principle initiatives that encouraged the elaboration and implementation of comprehensive, effective and sustainable strategies for HRE at the national level (UN 2010). Since this Decade (UN 1997), the UN has proposed a World Programme for Human Rights of which the first phase (2005-2009) has already been implemented. The second phase of the World Programme for Human Rights Education (2010-2014) is currently being implemented and focuses on HRE for higher education and for human rights training of teachers and educators, civil servants, law enforcement officials and military personnel (UN 2010). Drawing on this Programme as one of the UN's (2010) initiatives in practice, possible human rights stances that could underpin the UNs conception of HRE are elaborated on.

Dembour's (2010) Four Schools of Human Rights Underpinning HRE

The World Programme for Human Rights (2010-2014) regards HRE as encompassing three dimensions: (1) Knowledge and skills; (2) Values, beliefs and attitudes; and (3) Action (UN 2010:4-5). These dimensions will now be discussed from the perspective of Dembour's (2010) four schools of human rights so as to present possible stances to approaching RaE in HRE curriculum-making.

Knowledge and Skills as a Dimension of HRE: Natural Human Rights Stance

The UN (2010:4) defines knowledge and skills as 'learning about human rights and mechanisms as well as acquiring skills to apply them in a practical way in daily life'. Learning 'about' human rights assumes that knowledge is to be shared and the natural school of human rights is a possible avenue to introduce this.

Dembour (2010) refers to the natural school of human rights as rights people possess because they are human beings. Scholars of the natural school of human rights ' see human rights law [as] in direct continuation with . human rights [as a] concept' (Dembour 2010:6). Tibbitts and Fernekes (2011) posit the view that within the realm of HRE, human rights are expressed through legal and normative dimensions. The legal dimension contributes to the underlying tenets of natural rights. It is primarily concerned with providing knowledge and content 'about international human rights standards as embodied in the UDHR and other treaties and covenants to which countries subscribe' (Tibbitts & Fernekes 2011:93). Within HRE, the natural school is thus preoccupied with knowledge about human rights as a legal construct and with the rights that citizens are entitled to simply because they are human beings.

The need for natural rights stems, for example, from a desire to provide a shield against different forms of despotism. At the same time, the human rights movement has the potential to become 'absolutist' by 'insisting on a list - and a constant growing list - of human rights as the sole and sufficient justification for all political action' (Scruton 2012:120). A human rights stance such as this could initiate 'political literacy' and a 'compliance approach' towards human rights (Keet 2007). Political literacy and compliance approaches construe human rights as the knowledge one has of the legal obligations of the state to the people and of the people to be accountable and responsible towards the rights they are accorded by the state (Keet 2007:216). People cannot exercise their rights if they do not have knowledge of the legal obligations of the state and of their own rights in relation to such obligations. In addition to being excluded from participation in domains such as social, political and economic rights through a lack of knowledge, people could have only a partial, selective or superficial knowledge of their rights (Simmonds 2010). Such a situation might lead to political illiteracy and incompliance. A human rights knowledge paradox could emerge in which a lack of human rights knowledge could result in the exclusion of participation, and partial, selective or superficial human rights knowledge could result in restricted participation. It is important to be aware that the promotion of universal human rights is (to a lesser or greater extent) dependent on the citizens' awareness of their rights as well as their exercising their rights.

For RaE this could imply that one's right to religious freedom and belief becomes a legal commodity rather than a complex system of value driven principles. Educators, students and learners become exposed to RaE as a market place that merely displays knowledge about diverse religions and not a meeting place where diversity can be embraced and deliberated.

Values, Beliefs and Attitudes as a Dimension of HRE: Deliberative Human Rights Stance

The UN's World Programme for Human Rights Education (2010:4) dimension values, beliefs and attitudes, aims at 'developing values and reinforcing attitudes and behaviour which uphold human rights'. The national curriculum of South African schools shares this desire. This is reflected in its ' attempts to infuse human rights into the curriculum' and emphasise ' skills and attitudes that lead to the positive development and appreciation of human rights' as well as ' values that underpin human rights' (Carrim & Keet 2005:102). In the exploration of this situation, a deliberative human rights stance is considered.

Dembour's (2010) deliberative school of human rights thought deems values, beliefs and attitudes as significant for consideration within the realm of the HRE dimension. This school of thought depicts human rights as political values that societies choose to adopt. Human rights thus ' come into existence through societal agreement'; this occurs 'only when and if everybody around the globe becomes convinced that human rights are the best possible legal and political standards that can rule society' (Dembour 2010:3). This school also stresses the risk that this approach could lead to governing the state as a political entity, underestimating moral and social human life (Dembour 2010:3). In effect, human rights are only possible if they are agreed upon by individuals in society, in such a way that people 'buy into' them or are convinced of their value. In discussing this aspect, Keet (2007:215) refers to the notion of 'social cohesion' and argues that when human rights emerge from societal agreement, societies unite to promote respect for human rights, human dignity and diversity.

The ' normative dimension' of deliberative schools of human rights thought has made a significant contribution to shaping HRE. It strives to transform the lives and realities of individuals and societies so that they are ' more consistent with human rights norms and values' (Tibbitts & Fernekes 2011:93). For RaE this would mean advocating less for curriculum knowledge of diverse religions and putting more emphasis on the norms and values that underpin them.

Action as a Dimension of HRE: Protest Human Rights Stance

Within the UN's World Programme for Human Rights Education (2010) 'action' in the form of ' taking action to defend and promote human rights' (UN 2010:5) is the third and final dimension. A term like this is open to ambiguous and abstruse interpretations. The interpretation used in this article is tied to the protest human rights stance.

For Dembour (2010:1) protest scholars regard human rights as ' fought for' rather than given, agreed upon or talked about. There is thus a shift away from human rights as entitlements to human rights as 'claims and aspirations that allow the status quo to be contested in favour of the oppressed' (Dembour 2010:3). Inquiry into power and privilege characterise the struggles for authentic change and challenge of dominance. As Dembour (2010:3) notes, the ultimate desire resides in 'the concrete source of human rights in social struggles' for ' redressing injustice' . Within the same stance, Keet (2007:215) refers to a human rights 'resistance approach' that internalises ' human rights as a form of resistance against human rights violations' . Thus for protest scholars, human rights beget human rights injustice and therefore human rights are embraced as the premise to challenge, combat and disrupt injustice. In doing so, there is a tendency to ' view human rights law with suspicion' on the pretext that human rights orthodoxy promotes a 'process that tends to favour the elite and thus may be far from embodying the true human rights idea' (Dembour 2010:3). However, protest scholars (who view human rights on a metaphysical and not an instinctive basis) advocate the internalisation of human rights with regard to oneself as well as others (Dembour 2010:7). This underlines their desire for HRE to be used as an avenue to explicitly and implicitly engage with human rights violations and thus bring about greater awareness of human rights injustices. RaE could provide a similar avenue, namely to explicitly and implicitly engage with religious violations and thus bring about greater awareness of religious injustices.

Critique of HRE: Nihilism Human Rights Stance

Having rejected the UN's three dimensions of HRE (UN 2010), the fourth school of human rights considers a nihilist human rights stance. Dembour (2010) places discourse scholars in this school of human rights thought. These scholars argue that 'human rights exist only because people talk about them' and not because they ' believe in human rights' , and thus human rights cannot be realised (Dembour 2010:4). Human rights imperialism is feared as a means of limiting individual human rights; there is thus a perception of the foundation of human rights as reflecting ' disdain and as fundamentally flawed' (Dembour 2010:7). These scholars advocate instead that 'superior projects of emancipation . be imagined and put into practice' (Dembour 2010:4). Perhaps the parallel for RaE would be the inference that atheism or secularism is the point of departure.

Dembour (2010:10) cautions that, philosophically, nihilism need not imply a rejection of all human rights principles but rather the desire 'for new values to be created through the re-interpretation of old values that have lost their original sense' . This might be a proposal for a deconstructive, post-structuralist prospect of human rights. In terms of HRE, Keet (2012:7) posits:

Studies on HRE predominantly focus on the conversion of human rights standards into pedagogical and educational concerns with the integration of HRE into education systems and practices as its main objective. Together with the apparent legitimacy of HRE, these studies constructed HRE as a declarationist, conservative and uncritical framework that disallows the integration of human rights critiques into the overall HRE endeavour. Thus, instead of facilitating the transformative radicality of human rights, the dominance of this approach ... limits the pedagogical value of HRE.

Keet's (2012) disquiet about current HRE studies and education practices led him to plead for a renewal of HRE from a discourse approach to human rights. A discourse approach 'invites critique to disclose the operations of the rules of discourse and to make visible the anchoring points for transformative practices' (Keet 2012:8).

To some extent echoing this plea, in the next section, I introduce the notion of human rights literacy (HRLit) to re-interpret HRE. HRLit is neither a rejection of human rights nor an uncritical reflection of it, but rather a new way of thinking of the multifaceted nature of the UN's three dimensions of HRE.

Curriculum-making Underpinned by Human Rights Literacy (HRLit): Its Possibilities

Janks (2010:2-3) expresses caution that 'many languages do not have a word for literacy' and so resort to translations such as ' educated or schooled' . Such translations become problematic because of the associations with defining or labelling people as 'refined, learned, well-bred, civilized, cultivated, cultured, [and] genteel', for example (Janks 2010:3). Research conducted by Janks (2010:1), in South Africa and internationally, indicates that languages that do not have a word or translation for literacy include isiXhosa, Sesotho, German and French.

The competing definitions and approaches to literacy are so dramatic that they have been referred to as the 'literacy wars' (Janks 2010:xiii). Broadly speaking, this is a war between the conception of literacy as a cognitive skill or as a social practice. As a cognitive skill, literacy alludes to the ability to read, write, memorise patterns, comprehend meaning, evaluate content, synthesise information and so on (Janks 2010:xiii & 2). This was formed as an ' antithesis to illiteracy' where literacy denotes that a person is ' liberally educated or learned' whilst an illiterate person is not (Janks 2010:23). Literacy as a social practice, on the other hand, involves the different socio-cultural orientations to literacy that take cognizance of 'patterned and conventional ways of using written language that are defined by culture and regulated by social institutions: different communities do literacy differently' (Janks 2010:2). In other words, embracing literacy as a social practice advocates that individuals be ' agents who can act to transform the social situations in which they find themselves' (Janks 2010:13).

Street's (1984; 2011) models of literacy (autonomous and ideology model) echo the two forms of literacy depicted by Janks (2010). In more recent work, Street (2011) has highlighted that engaging in aspects of inequalities necessitates adopting an ideological model of literacy. A primary aspect of the ideological model of literacy is its intention to explicitly reveal underlying conceptions and assumptions; to consider the use and meaning of literacy in different contexts; and to underpin the notion that it is 'less important to say what literacy is than what it does' (Street 2011:581). Conversely the autonomous literacy model defines literacy independently of cultural context and meaning and thus makes ethnocentric and universal claims (Street 2011:581).

HRLit as a normative ideal will be discoursed from the perspective of literacy as a socio-cultural and ideological construct. Keet's (2012) conception of a discourse approach to human rights begets an underlying précis of HRLit. Keet (2012:8) argues that if human rights are 'unaware of its own discursive nature [it] will be reproductive and not transformative'. A discourse approach to HRE is a ' dynamic pedagogical interlocution' that ' root[s] normative human rights frameworks within human rights critiques' (Keet 2012:9). The discursive space(s) create 'the language of human rights and the practices ensuing from it must forever remain in a space of contestation, contention, disputation, public debate and social engagement' (Keet 2012:9). It is this space and the various spaces it creates that I regard as paramount for HRLit.

Thinking of HRE anew ' does not require better methods or assessment strategies. It simply yearns to be educational' (Keet 2012:22). Furthermore, a HRE is required, ' one whose fidelity is spawned by incessant betrayals and by relentless human rights critiques. To do otherwise is to be anti-educational and anti-human rights' (Keet 2012:21). Making human rights critiques the centre of a discourse approach to HRE indicates that ' critiques do not constitute a dismissal or rejection of human rights but rather fidelity towards it . so that the social practices and relations that constitute HRE are in a permanent state of renewal' (Keet 2012:22). Qian Tang (2011:5), Assistant Director-General for Education at UNESCO, stresses that only through taking a holistic and cooperative approach to HRE in conjunction with embracing the forever changing human rights landscape can HRE be truly effective in guaranteeing respect for the rights of all. Thus I argue for the need to conceptualise HRE from a HRLit stance and consider how to foster a disposition which is informed by HRLit.

Figure 1 demonstrates my interpretation of the potential of HRE to include the three HRE dimensions: knowledge and skills, values, beliefs and attitudes as well as action. Within a democratic education, the desire is for HRE to address all three dimensions adequately. Tibbitts and Kirchschlaeger (2010:21) argue that HRE must 'fill the "action" gap between HR awareness and knowledge and participation in the political domain by taking steps to change behaviours in inter-personal relationships'. I acknowledge that HRE has the inherent capacity to initiate and facilitate inter-personal relationships. However, I question the extent to which HRE can bring about change, especially transformative change. On this note, I turn to HRLit.

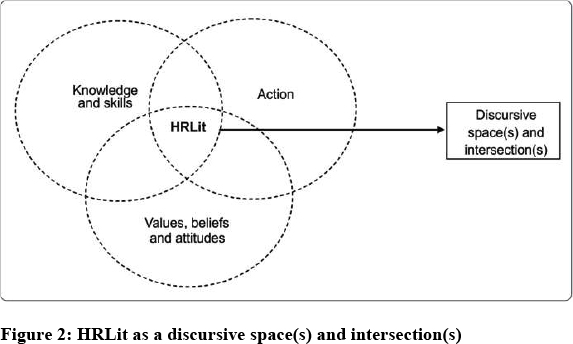

HRLit presents a different picture because it is not the three dimensions of HRE that define it, but rather intersection(s) of these dimensions. From a HRLit stance, curriculum becomes a discursive space wherein human rights stances and issues are deconstructed, challenged and critiqued. Therefore, it echoes Keet's (2012:9) view that 'the language of human rights and the practices ensuing from it must forever remain in a space of contestation, contention, disputation, public debate and social engagement' . It is in this space(s) and intersection(s) that human rights injustices as well as justices can be embraced in a critical and transformative manner. It leads to curriculum that engages with and fosters dispositions for values and awareness, accountability and transformation of human rights (cf. Tibbitts 2002). This is reflected in the desire of HRLit to create a platform for engaging in social issues such as poverty, gender, religion and social justice from a safe space that is rigorous but also underpinned with fidelity towards human rights and education. The implication of this is that the dimensions of HRE must not be seen in isolation, but rather as intertwined and in interlocution to enhance the socio-cultural nature of human rights. This demonstrates the strength of the diversity of the nature of human rights - the very thing that makes a definition of human rights elusive. This diversity makes it possible not only to deconstruct, but also challenge human rights injustices: naming these injustices become less significant than engaging with them. See Figure 2.

What does HRLit mean for curriculum-making? A shift of curriculum studies in the 1970s brought a wide range of scholarly sources to the fore, such as diverse philosophies, literary and artistic works and a range of social, political and economic perspectives. Thus, the seminal questions of curriculum studies are pursued relative to whatever configurations human association or community lend themselves to, and such pursuits are not limited to school alone. According to Schubert (2010:229), curriculum studies thus deal with a robust array of sources that provide; (a) perspectives on questions about what curriculum is or ought to be; (b) alternative or complementary paradigms of inquiry that enable explorations of such questions; and (c) diverse possibilities for proposing and enacting responses to the questions in educational theory and settings of educational practice. This approach to curriculum-making embraces the curriculum as 'a verb, an action, a social practice, a private meaning, and a public hope' (Pinar 2010:178). Because of its normative concerns, curriculum is engaged with in a complicated conversation by asking ontological questions.

Drawing on dimensions of critical pedagogy, this framework of curriculum-making places emphasis on the interests of equity and social justice, as well as self-realization and identity (Schubert 2010:229-230). In addition, HRE ' has emerged as the inversed image of the violations it is meant to combat' and has its 'value as the dominant moral universal vernacular of our time, is dependent on a critical educational form that provides the productive interface between human rights and the counter-image of suffering of the real-existing communities in whose name they speak' (Keet 2012:8-9).

It is from this stance that gender, ethnicity, religious, cultural, socioeconomic and other violations are human rights, curriculum and HRE concerns and thus of direct concern for HRLit. Therefore, this view reiterates the value of HRLit for RaE as well as other facets of curriculum-making.

Going from the General to the Specific: Taking a Gender Stance

In her most recent work, Roux has shifted her scholarship towards gender-based research. Although this shift is still underpinned by an RaE approach to HRE, Roux's scholarship has been informed by gender, social justice and other feminist discourses. She has thus positioned her work in what she terms an 'auto-ethnographic feminist research paradigm' (Roux 2009). This specific focus, which arises from the findings in her previous research (Roux, Smith, Ferguson, Small, Du Preez & Jarvis 2009), took form during an international SANPAD (South Africa and the Netherlands Research Programmes on Alternatives in Development) project she led from 2009-2012 entitled Human Rights Education in Diversity: Empowering Girls in Rural and Metropolitan School Environments (Roux 2009). Some of the core publications depicting her gender-based research stance include:

- A Social Justice and Human Rights Education Project: A Search for Caring and Safe Spaces (Roux 2012b)

- Girls' and Boys' Reasoning on Cultural and Religious Practices: A Human Rights Education Perspective (De Wet, Roux, Simmonds & Ter Avest 2012).

- Engaging with Human Rights and Gender in Curriculum Spaces: A Religion and Education (RaE) Perspective (Simmonds & Roux 2013).

In reflecting on Roux's most recent gender-based research scholarly focus, I suggest using a critical HRLit discourse as a means of exploring her gender-based research stance from another perspective.

In Response: A Critical HRLit Discourse for Gender-based Research

Literacy invokes a multiplicity of meanings through deconstructing language in use. From this viewpoint, literacy is ' an act of sensitization to the political implications of contestation over a diversity of conceptual meanings' (Hughes 2002:3). In this regard, the need for critical literacy to be well established as a term comes to the fore. Critical literacy ' signals a move to question the naturalized assumptions of the discipline, its truths, its discourses and its attendant practices' (Janks 2010:13). A conception such as critical literacy ' forces us to think about how all discourses, not just discourses of literacy, produce truth, how they are produced by power and how they produce effects of power' (Janks 2010:14). More explicitly, critical literacy is an,

... analysis that seeks to uncover the social interests at work, to ascertain what is at stake in textual and social practices. Who benefits? Who is disadvantaged? In short, it signals a focus on power ... (Janks 2010:12-13).

The constituencies of critical literacy are therefore a valuable means of exposing hegemonic discourses and engaging with power and privilege. In addition, critical literacy creates the space to deconstruct and reconstruct the oppressed, the oppressor as well as other contributing forces. From another perspective, if HRLit displays the discursive spaces within and between dimensions of HRE (see Figure 2) then critical HRLit deconstructs these discursive spaces and engages with their meanings (Simmonds 2013). Of significance is the potential for critical HRLit to disrupt knowledge and create gender awareness. According to Janks (2010), critical literacy has four distinct nuances. I will refer to these nuances as necessary conceptual tools when engaging in gender-based research.

- Domination. In its poststructuralist form, domination refers to power in terms of revealing hidden ideologies when posing questions such as: Who benefits? Who is disadvantaged? (Janks 2010:36). Critical deconstruction becomes paramount in this regard. For gender-based research Foucault's (1977) theory of power proves insightful. For Foucault (1977) power is not an exchange between oppressors and oppressed; power is part of all social relations on multiple, interwoven levels. Janks (2010:58) elaborates this stance by stating that 'speaking and writing cannot be separated from embodied action (doing), ways of thinking and understandings of truth (believing), and ethics (valuing)'. Critical HRLit encourages HRE to grapple with gender-based topics through domination discourses so it can grapple with the ideologies of power that construct and underpin these. Therefore, such domination discourses are embedded in feminist pedagogy and can further been regarded as situated critical pedagogies.

- Design. Design is used as a metaphor by Janks (2010:61) to depict the way communities 'do' literacy; it denotes 'their way of seeing and understanding the world'. For critical HRLit, taking cognizance of how different individuals and societies 'do' gender creates a platform to inquire how gender can be 'done', 'undone' as well as 'done/ undone' simultaneously. Gender topics, as elusive and opaque social constructs, must be disrupted rather than accepted at face value. Furthermore, critical HRLit regards gender topics as social constructions that can be ' resisted and reshaped' because their 'enactment is hemmed in by the general rules of social life, cultural expectations, workplace norms and laws' (Lorber 2005:20). In curriculum-making, it also takes account of the experiences that teachers and learners bring to the classroom, in terms of unconscious or hidden curricula (De Wet et al. 2012).

- Diversity. For Janks (2010), diversity refers to the social identities embodied by people. She advocates 'imagining identity as fluid and hybrid; [saying] we resist essentialising people on the basis of any one of the communities to which they belong or to which we assign them' (Janks 2010:99). From a gender stance, Lorber (2012:331) argues for ' gender diversity' to draw ' attention to the ways that women men, boys and girls are not homogenous groups but cross-cut by cultures, religions, racial identities, ethnicities, social classes, sexualities and other major statuses'. Together with gender diversity, gender identities and the blurring of gender boundaries become the foci for gender topics within critical HRLit.

- Access. When access is perceived as 'a type of right, the right to enter and get through the gates, the right not to be excluded' (Janks 2010:153), then the question: 'Who gets access to what?' arises (Janks 2010:127). From a gender perspective access can be regarded as a form of gate-keeping. Gender gate-keeping can ask questions such as: Who is giving and who is gaining access? And: Access to what? Connell (2011:7) claims that gender-just societies involves institutional change as well as ' change in everyday life and personal conduct, and therefore requires widespread social support' . Gate-keeping is the key to critical HRLit as it deconstructs who is included, excluded, when and how.

These constituencies present four conceptual tools that can be applied in HRE curriculum-making to explore, expose and exhibit gender topics in order to engage with gender equity in its complexity. Critical HRLit constituencies overlap and should be viewed as interrelated and at the same time disclose, critique and disrupt their embedded constituencies. Therefore, Keet's (2012:9) need for HRE to 'forever remain in a space of contestation, contention, disputation, public debate and social engagement' resonates with a critical HRLit approach.

Conclusion

The curriculum-making landscape of RE as viewed through the lens of Roux's scholarship, captures the intricate scope and focus of this discipline. Curriculum reforms and ideologies underpinning curriculum-making in South Africa, have influenced Roux's conceptualisation of RaE and its concrete underpinning in human rights principles and values reflected in HRE. This article has interrogated this scholarship, positioning HRE within the education domain and exploring the human rights stances that inform it. This article has articulated the need to rethink HRE and has put forward HRLit and critical HRLit discourses. I challenge Roux to consider (or even contest) the critical HRLit discourse mooted in this article and grapple with its implications for her gender-based research stance within RaE. In this regard, I pose the following questions to her:

- What trend(s) do you foresee post-RaE?

- Will the trend(s) be conceptualised within HRE or should we be shifting the boundaries beyond HRE and towards a broader conception such as social justice or gender justice, for example?

References

Carrim, N. & A. Keet 2005. Infusing Human Rights into the Curriculum: The Case of the South African Revised National Curriculum Statement. Perspectives in Education 23,2: 99-110. [ Links ]

Chidester, D. 2002. Religion Education: Learning about Religion, Religions and Religious Diversity. In Asmal, K. & W. James (eds.): Spirit of the Nation: Reflections on South Africa's Educational Ethos. Cape Town: HSRC. [ Links ]

Connell, R. 2011. Confronting Equality: Gender, Knowledge and Global Change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Dembour, M. 2010. What are Human Rights? Four Schools of Thought. Human Rights Quarterly 32,1:1-20. [ Links ]

De Wet, A., C. Roux, S. Simmonds & I. ter Avest 2012. Girls' and Boys' Reasoning on Cultural and Religious Practices: A Human Rights Education Perspective. Gender and Education 24,6:665-681. [ Links ]

Du Preez, P., S. Simmonds & C. Roux 2012. Teaching-learning and Curriculum Development for Human Rights Education: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Journal of Education 55:83-103. [ Links ]

Flowers, N. 2003. What is Human Rights Education? Available at: www.hrea.org/erc/library/curriculum_methodology/flowers03.pdf. (Accessed on 18 June 2012. [ Links ])

Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Allan Lane. [ Links ]

Fritzsche, K.P. 2008. What do Human Rights Mean for Citizenship Education? Journal of Social Science Education 6,2:40-49. [ Links ]

Gearon, L. 2012. Introduction. In Roux, C. (ed.): Safe Spaces: Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Hughes, C. 2002. Key Concepts in Feminist Theory and Research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Janks, H. 2010. Literacy and Power. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Keet, A. 2007. Human Rights Education or Human Rights in Education: A Conceptual Analysis. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Keet, A. 2009. Reflections on the Colloquium within a Human Rights Discourse. In Nkomo, M. & S. Vandeyar (eds.): Thinking Diversity while Building Cohesion: Transnational Dialogue on Education. Pretoria: UNISA Press. [ Links ]

Keet, A. 2012. Discourse, Betrayal, Critique: The Renewal of Human Rights Education. In Roux, C. (ed.): Safe Spaces: Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Kiwan, D. 2005. Human Rights and Citizenship: An Unjustifiable Conflation? Journal of Philosophy of Education 39,1:37-50. [ Links ]

Kusy, M. 1994. Human Rights Education, Constitutionalism and Interrelations in Slovakia. European Journal of Education 29,4:377-389. [ Links ]

Lohrenscheit, C. 2002. International Approaches to Human Rights Education. International Review of Education 48,3-4:173-185. [ Links ]

Lorber, J. 2005. Breaking the Bowls: Degendering and Feminist Change. New York: Norton & Company. [ Links ]

Lorber, J. 2012. Gender Inequality: Feminist Theories and Politics. Fifth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lynch, J., C. Modgil & S. Modgil 1992. Human Rights, Education and Global Responsibilities. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Makoella T.M. 2009. Outcomes Based Education as a Curriculum for Change: A Critical Analysis. In Piper, H., J. Piper & S. Mahlomaholo (eds.): Educational Research and Transformation in South Africa. Potchefstroom: Platinum Press. [ Links ]

Mihr, A. 2004. Human Rights Education: Methods, Institutions, Culture and Evaluation. Available at: http://www.humanrightsressearch.de. (Accessed on 20 June 2012. [ Links ])

Mihr, A. 2009. Global Human Rights Awareness, Education and Democratization. Journal of Human Rights 8:177-189. [ Links ]

Niewenhuis, J. 2007. Growing Human Rights and Values in Education. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Osler, A. 2005. Teachers, Human Rights and Diversity. Staffordshire: Trentham Books. [ Links ]

Pinar, W.F. 2010. Currere. In Kridel, C. (ed.): Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies. Volume 2. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Potgieter, F.J. 2011. Morality as the Substructure of Social Justice: Religion in Education as a Case in Point. South African Journal of Education 31:394-406. [ Links ]

Roux, C. & P. du Preez 2005. Religion in Education: An Emotive Research Domain. Scriptura 89,2:273-282. [ Links ]

Roux, C., P. du Preez & R. Ferguson 2009. Understanding Religious Education through Human Rights Values in a World of Difference. In Miedema, S. & W. Meijer (eds.): Religious Education in a World of Difference. Münster: Waxmann. [ Links ]

Roux, C., J. Smith, R. Ferguson, R. Small, P. du Preez & J. Jarvis 2009. Understanding Human Rights through Different Belief Systems: Intercultural and Interreligious Dialogue. Research Report: South Africa Netherlands Research Programmes on Alternatives in Development (SANPAD). [ Links ]

Roux, C. 2009. Human Rights Education in Diversity: Empowering Girls in Rural and Metropolitan Environments (2010-2013). Research proposal submitted and proved by international funders, South Africa Netherlands Research Programmes on Alternatives in Development (SANPAD). [ Links ]

Roux, C. 2010. Religious and Human Rights Literacy as Prerequisite for Interreligious Education. In Engebretson, K, M de Souza, G Durka & L Gearon (eds): International Handbook of Inter-religious Education. London: Springer. [ Links ]

Roux, C. 2012a. Conflict or Cohesion? A Critical Discourse on Religion in Education (RiE) and Religion and Education (RaE). In ter Avest, I (ed): On the Edge: (Auto)biography and Pedagogical Theories on Religious Education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Roux, C. 2012b. A Social Justice and Human Rights Education Project: A Search for Caring and Safe Spaces. In Roux, C. (ed.): Safe Spaces: Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Shubert, W.H. 2010. Curriculum Studies, Definitions and Dimensions. In: Kridel C. (ed.): Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies. Volume 1. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Scruton, R. 2010. Nonsense on Stilts. In Cushman, T. (ed.): Handbook of Human Rights. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Simmonds, S. 2010. Primary School Learners Understanding of Human Rights Teaching-learning in Classroom Practice. Unpublished MEd dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Simmonds, S. 2012. Embracing Diverse Narratives for a Postmodernist Human Rights Education Curriculum. In Roux, C. (ed.): Safe Spaces: Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Simmonds, S. 2013. Curriculum Implications for Gender Equity in Human Rights Education. Unpublished PhD thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Simmonds, S. & C. Roux 2013. Engaging with Human Rights and Gender in Curriculum Spaces: A Religion and Education (RaE) Perspective. Alternation Special Edition 10:76-99. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Available at: www.info.gov.za/documents/constitution/1996/a108-96.pdf. (Accessed on 1 June 2010. [ Links ])

South Africa 2003. National Policy on Religion and Education. Government Gazette. 12 September. No. 25459. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa 2010. Government Gazette. 16 September. No. 34600. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Street, B. 1984. Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Street, B. 2011. Literacy Inequalities in Theory and Practice: The Power to Name and Define. International Journal of Educational Development 31,6:580-586. [ Links ]

Suarez, D. & F. Ramirez 2004. Human Rights and Citizenship: The Emergence of Human Rights Education. Available at: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. (Accessed on 12 June 2012. [ Links ])

Tang, Q. 2011. Forward. In UNESCO (eds): Contemporary Issues in Human Rights Education. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Tibbitts, F. 2002. Understanding What We Do: Emerging Models for Human Rights Education. International Review of Education 48,3-4:159-171. [ Links ]

Tibbitts, F. & W.R. Fernekes 2011. Human Rights Education. In Totten, S. & J.E. Pedersen (eds.): Teaching and Studying Social Issues: Major Programs and Approaches. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Tibbitts, F. & P.G. Kirchschlaeger 2010. Perspectives of Research on Human Rights Education. Journal of Human Rights Education 2,1:1-31. [ Links ]

UNESCO 2011. Contemporary Issues in Human Rights Education. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. [ Links ]

United Nations 1995. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/. (Accessed on 15 June 2010. [ Links ])

United Nations 1997. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR): United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education and Plan of Action (1995-2004). Report of the Secretary General. 20 October 1997. Available at: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/education/training /decade.htm. (Accessed on 15 June 2010. [ Links ])

United Nations 2010. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR): Draft Plan of Action for the Second Phase (2010-2014) of the World Programme for Human Rights Education. 27 July 2010. Available at: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/ 15session/A.HRC.15.28_en.pdf. (Accessed on 15 June 2010. [ Links ])