Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.36 n.2 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2023/v36n2a6

ARTICLES

The Sabbath Year and Socio-Economic Issues in Lev 25:2-7

Ndikho Mtshiselwa

UNISA

ABSTRACT

Leviticus 25:2-7 has its closest parallel in the Pentateuchal and other post-exilic texts, namely Exod 23:10-11; Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18 and Neh 5; 9:32-37 and 13. The texts are about the Sabbath year, YHWH, the land and socio-economic issues. A convincing consensus on the directionality of influence and dependence between Lev 25:2-7 and these texts is hardly reached. In addition, there is room for further research on the function and significance of Lev 25:2-7. The article argues that inner-biblical exegesis shows that Lev 25:2-7 depended on some Pentateuchal texts and served to legitimise the Sabbath tradition and to address socio-economic issues in the Persian period. In addition, the text influenced the production of some texts in the book of Nehemiah. First, the essay considers the grammatical features, style and content of Lev 25:2-7. Second, the article discusses the dating of the Pentateuchal scribal activity with specific focus on the Covenant Code (CC), versions of Deuteronomy and the Holiness Code (H). Third, the reception of Exod 23:10-11 and Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18 in Lev 25:2-7 is examined. Lastly, the study probes the reception of Lev 25:2-7 in Neh 5; 9:32-37; and 13 and submits that Lev 25:2-7 depended on earlier Pentateuchal texts and subsequently influenced post-exilic texts on the subject of the Sabbath year in order to address the socio-economic issues of the time.

Keywords: Leviticus, Sabbath year, Land, Socio-economic justice, Food, Hunger

A INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, biblical scholarship has produced various interpretations of Lev 25:2-7. As Nihan notes, Lev 25 "rehabilitates against D an interpretation of the seventh year as serving exclusively for the 'rest' of the land (v. 2-7)."1Further, "the law of 25:2-7 is clearly modelled upon Exod 23:10-11, as various scholars have noted."2 Nihan is also of the view that the apparent emphasis on the religious function of Lev 25:2-7 and the significance of the Sabbath year replaced the "former 'humanitarian' motivation (concern for the poor) of Exod 23:11."3 As Nihan observes, the concern for the poor and the socially and economically disadvantaged people as well as for socio-economic justice that is expressed in Lev 25:8-55 is missing in verses 2-7.4 Leviticus 25:2-7 also has its closest connection in other Pentateuchal texts (Exod 23:10-11; Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18) and post-exilic texts (Neh 5; 9:32-37; 13) where allusions to the Sabbath tradition are made. However, the directionality of influence and dependence between Lev 25:2-7 and other texts remains debatable.

In his analysis of the grammatical and persuasive features of Lev 25, Meyer offers a valuable contribution to the study of Lev 25:2-7.5 He claims that the text is about the Sabbath laws. The authors of the Holiness Code (H) address "those who are about to receive the land" (Lev 25:2b) as well as those who either owned or had a legal claim to the land (Lev 25:3-5).6 Drawing on the book titled, A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar,7 Meyer presents the semantic functions of the words, phrases and grammar that are employed in the text. For instance, as he argues, the semantic function of the imperfect verbs in verse 3 is to indicate habitual actions that ought to be performed during the six years of the seven-year cycle.8 Furthermore, not only does Meyer describe the function of '7 in Lev 25:27 as indicative of the goal of the Sabbath year, he also suggests that the preposition also served to point out the beneficiaries in that year.9 Given the persuasive features of the text, "the beneficiaries of the Sabbath laws were primarily the land itself and YHWH, and that the different groups of people introduced by  in the chiastic structure of vv. 6 and 7 appear as an afterthought."10

in the chiastic structure of vv. 6 and 7 appear as an afterthought."10

In contrast to the literary-historical critical readings of the text, Van Deventer suggests that Lev 25:2-7 exhibits ecological undertones.11 The text introduces a law that elevates the idea of caring for the land. Van Heerden also views Lev 25:2-7 as a text that reflects concerns for the environment and the land and that is about the Sabbath year which features YHWH and human beings.12 He states that "the Sabbath year is not primarily for the sake of the land (otherwise it would amount to pantheism)."13 Further, "It is also not primarily for the sake of human beings (otherwise it would boil down to anthropocentrism)."14 Van Heerden claims that Lev 25:2-7 expresses the need to care for the land that is in turn a human response to the holiness of God.15

Old Testament scholars have therefore offered various interpretations of Lev 25:2-7. The point that there is hardly a clear consensus on the function as well as the direction of the influence and dependence of the text makes room for further research. As far as I know, Lev 25:2-7 is yet to be read as a text that likely depended on numerous earlier Pentateuchal texts, with the aim of addressing the Sabbath year and socio-economic issues. There is also room for investigating the probable influence of Lev 25:2-7 on other later sources in the post-exilic period. The hypothesis of the present essay may be formulated in this manner: Inner-biblical exegesis reveals that not only did Lev 25:2-7 serve to legitimise the Sabbath tradition and address socio-economic issues in the Persian period, but it also influenced the author of the book of Nehemiah to address related religious-ethnic and socio-economic issues in the post-exilic context.

On a methodological level, inner-biblical exegesis is employed to verify the hypothesis. Stackert defines inner-biblical exegesis as an "interpretive revision, reuse, expansion, or application of biblical source material in subsequent biblical compositions."16 His definition is consistent with Fishbane's idea of inner-biblical exegesis.17 As noted by Meek, "inner-biblical exegesis is methodologically preferable if a scholar is attempting to make a case that later authors are referring to a previous text in order to explicate, comment on, expand, or in some other way make it applicable to a new situation."18

B GRAMMATICAL FEATURES, STYLE, AND CONTENT OF LEV 25:2-7

Based on grammatical features, style and content, Lev 25:2-7 can be divided into three parts (vv. 2, 3-5, 6-7). The text is centred on the Sabbath year, which forms part of the religious tradition of ancient Israel. As will be shown below, the text also alludes to the use of productive land and socio-economic issues. First, some remarks on the grammatical features of the text are in order.19

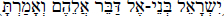

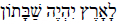

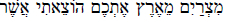

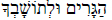

Not only does the command statement in Lev 25:2a, "Speak to the people of Israel and say to them," ( ), introduce the Sabbath year text, it also designates the addressees as the Israelites. Verse 2b which reads,

), introduce the Sabbath year text, it also designates the addressees as the Israelites. Verse 2b which reads,  ("When you enter the land that I am giving you..."), is a direct conditional speech formulated using the conditional and/as temporal particle

("When you enter the land that I am giving you..."), is a direct conditional speech formulated using the conditional and/as temporal particle  (when) together with an imperfect verb

(when) together with an imperfect verb  (enter) as well as the noun

(enter) as well as the noun  (the land) and an immanent particle

(the land) and an immanent particle  (give). Verse 2b presents the Sabbath year as a futuristic event, suggesting that the verse was written at a time when the addressees had not yet possessed the land that was given to them by

(give). Verse 2b presents the Sabbath year as a futuristic event, suggesting that the verse was written at a time when the addressees had not yet possessed the land that was given to them by  (the Lord). The point that verse 2b addresses "those who are about to receive the land"20 suggests various possible implications. Verse 2b was either written in exile as a promise to possess the land or a reminder to the returnees in the post-exilic period that the land they now possess belonged and still belongs to YHWH. Hence, the land is to rest in order to observe

(the Lord). The point that verse 2b addresses "those who are about to receive the land"20 suggests various possible implications. Verse 2b was either written in exile as a promise to possess the land or a reminder to the returnees in the post-exilic period that the land they now possess belonged and still belongs to YHWH. Hence, the land is to rest in order to observe  ("a Sabbath to the Lord"; Lev 25:2b). The waw consecutive ] that is attached to the imperfect verb to form

("a Sabbath to the Lord"; Lev 25:2b). The waw consecutive ] that is attached to the imperfect verb to form  in verse 2b directs what is to happen with the land when it is in the possession of the addressees. It therefore makes sense to view verse 2b as a text, which in its final form was employed by H to remind the post-exilic Judeans that the ultimate owner of the land is YHWH. This does not rule out the possibility that in the late exilic period, the text was intended to be a promise of land.

in verse 2b directs what is to happen with the land when it is in the possession of the addressees. It therefore makes sense to view verse 2b as a text, which in its final form was employed by H to remind the post-exilic Judeans that the ultimate owner of the land is YHWH. This does not rule out the possibility that in the late exilic period, the text was intended to be a promise of land.

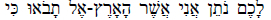

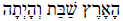

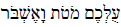

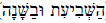

Verses 3-5 present what is to occur during the seven-year cycle of using the agricultural land. In verse 3, H employs imperfect verbs  (shall sow) and

(shall sow) and  (shall prune) as well as the concluding waw consecutive and a perfect verb

(shall prune) as well as the concluding waw consecutive and a perfect verb  (and will gather) to present a command about the use of the agricultural land during the six years of a seven-year cycle. The concluding waw consecutive and a perfect verb guarantee the collection of the produce of the land when it is consistently (or habitually)21 and productively used. The six years is followed by the Sabbath year. The conjunction 1 "but" at the beginning of verse 4 connects verses 3 and 4 in a contrasting manner to render a negative command, which includes imperfect verbs

(and will gather) to present a command about the use of the agricultural land during the six years of a seven-year cycle. The concluding waw consecutive and a perfect verb guarantee the collection of the produce of the land when it is consistently (or habitually)21 and productively used. The six years is followed by the Sabbath year. The conjunction 1 "but" at the beginning of verse 4 connects verses 3 and 4 in a contrasting manner to render a negative command, which includes imperfect verbs  and

and  . Verse 4 prohibits the Judeans from working the land thus placing a moratorium on the habitual actions relating to the use of the agricultural land. The negative command in verse 4, "you shall neither sow your field, nor prune your vineyard,"(

. Verse 4 prohibits the Judeans from working the land thus placing a moratorium on the habitual actions relating to the use of the agricultural land. The negative command in verse 4, "you shall neither sow your field, nor prune your vineyard,"( ), sheds light on how the land should be rested. Verse 4 also contains objects, that is, nouns representing something and a being that receives the action of the verbs. The command,

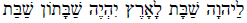

), sheds light on how the land should be rested. Verse 4 also contains objects, that is, nouns representing something and a being that receives the action of the verbs. The command,  ("shall be a Sabbath a complete rest of the land, a sabbath to the Lord"; Lev 25:4), presents both

("shall be a Sabbath a complete rest of the land, a sabbath to the Lord"; Lev 25:4), presents both  (the land) and

(the land) and  (the Lord) as objects. The clause

(the Lord) as objects. The clause  in verse 5 also presents the land as an object. On account of the preposition

in verse 5 also presents the land as an object. On account of the preposition  that is attached to the nouns, both the land and YHWH could be the objects as opposed to subjects, as Meyer opines.22 The land and YHWH do not necessarily represent the person or thing (a noun or pronoun) that does the action. Regarding the action of Sabbath in verses 4 and 5, both the land and YHWH are the beneficiaries of the action.23Interestingly, Meyer observes that,

that is attached to the nouns, both the land and YHWH could be the objects as opposed to subjects, as Meyer opines.22 The land and YHWH do not necessarily represent the person or thing (a noun or pronoun) that does the action. Regarding the action of Sabbath in verses 4 and 5, both the land and YHWH are the beneficiaries of the action.23Interestingly, Meyer observes that,

[U]p to v. 5 the "somebody" being addressed is asked to refrain (the marked word order clauses in vv. 4 and 5) from the actions that this person does every year (as described in v. 3). Yet the addressee does not benefit from his actions and the beneficiaries are either the land itself or YHWH or both.24

Based on verse 2ab, the addressees-the people of Israel who received or obtained the land and even had somewhat of an entitlement and power over the agricultural land-are not the main beneficiaries of the Sabbath year in verses 4 and 5.

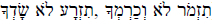

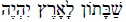

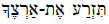

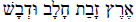

The phrase,  ("and the sabbath produce of the land") in the text of Lev 25:6 links verses 3-5 and 6-7 because it is a continuation of the clause

("and the sabbath produce of the land") in the text of Lev 25:6 links verses 3-5 and 6-7 because it is a continuation of the clause  ("complete rest of the land") in Lev 25:5. Additionally, the reference to the land, Sabbath and harvest relates verses 3-5 and 6-7. These relate to the actions and beneficiaries during the Sabbath year. With the reference to YWHW and Sabbath, H attaches a religious interpretation of rest for the land to agricultural production of food. The religious connotation in the reference to

("complete rest of the land") in Lev 25:5. Additionally, the reference to the land, Sabbath and harvest relates verses 3-5 and 6-7. These relate to the actions and beneficiaries during the Sabbath year. With the reference to YWHW and Sabbath, H attaches a religious interpretation of rest for the land to agricultural production of food. The religious connotation in the reference to  (Sabbath) and the economic inference in

(Sabbath) and the economic inference in  (the produce) in verse 6 were meant to highlight the needed provision of food. Furthermore, the beneficiary of the Sabbath year in verse 6 is "you," which includes various groups of people, namely the addressee in verse 2 or

(the produce) in verse 6 were meant to highlight the needed provision of food. Furthermore, the beneficiary of the Sabbath year in verse 6 is "you," which includes various groups of people, namely the addressee in verse 2 or  (you/ the Israelites) and other people identified with the nouns following the waw consecutive:

(you/ the Israelites) and other people identified with the nouns following the waw consecutive:  ("and your male slave");

("and your male slave");  ("and your female slave");

("and your female slave");  ("and your hired worker") and

("and your hired worker") and  ("and your settler who is sojourning"). The different groups of people are brought together to show that H was concerned about socioeconomic justice, as the wealthy elites and the poor had to share the agricultural produces. Meyer's observation that various groups of people "will benefit from these laws along with the person primarily addressed up to now" is correct.25 The provision of food for the economically underprivileged possibly sought to address the problem of hunger.

("and your settler who is sojourning"). The different groups of people are brought together to show that H was concerned about socioeconomic justice, as the wealthy elites and the poor had to share the agricultural produces. Meyer's observation that various groups of people "will benefit from these laws along with the person primarily addressed up to now" is correct.25 The provision of food for the economically underprivileged possibly sought to address the problem of hunger.

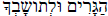

Although related, verse 7 is different from verse 6. The latter is concerned about people, whilst the former focuses on animals. However, both verses are about the provision of food for YHWH's creation during the Sabbath year. Furthermore, worthy of note is the function of the chiastic structure in verses 67. Based on grammar and style and from the perspective of persuasion, the chiastic structure in verses 6-7 makes the verses significant. In addition, the use of the preposition  is striking. Drawing on Van der Merwe, Naudé and Kroeze,26Meyer describes the function of

is striking. Drawing on Van der Merwe, Naudé and Kroeze,26Meyer describes the function of  as indicative of the goal of the process, namely the Sabbath year in the case of the present text and notes that the preposition also serves to point out the beneficiaries of that Sabbath.27 In verses 6-7, the food is transferred to the various groups of people and animals. These beneficiaries join the persons primarily addressed in verses 2-5 who are about to be the possessors of the productive land (v. 2) and those who either have the legal claim to the land or already own the land (vv. 3-5).

as indicative of the goal of the process, namely the Sabbath year in the case of the present text and notes that the preposition also serves to point out the beneficiaries of that Sabbath.27 In verses 6-7, the food is transferred to the various groups of people and animals. These beneficiaries join the persons primarily addressed in verses 2-5 who are about to be the possessors of the productive land (v. 2) and those who either have the legal claim to the land or already own the land (vv. 3-5).

In sum, some inferences may be made from the grammatical features, style and content of Lev 25:2-7. Leviticus 25:2-7 was composed and finalised to address, initially, the Israelites who were about to receive the land promised to them and later, the Israelites who possessed the agricultural land. Thus, H juxtaposed religious connotation in  and the economic undertone in

and the economic undertone in  to highlight the need for provision of food to various groups of economically disadvantaged people and to animals.

to highlight the need for provision of food to various groups of economically disadvantaged people and to animals.

C SCRIBAL SCHOLARSHIPS IN THE FORMATION OF LEV 25:2-7

Inner-biblical exegesis in some of the Pentateuchal compositions is evident and is worth considering in the discussion of the scribal formation of Lev 25:2-7. Some authors as well as redactors often read and reused earlier sources with in order to address certain issues in their respective contexts. The authors of H read and used earlier sources, that is, texts ascribed to the Deuteronomistic writers (D), Priestly authors (P), authors of CC and non-Priestly writers (non-P). The similarities and differences between Lev 25:2-7 and other related earlier texts such as Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18 and Exod 23:10-11, support this point. Before investigating the possibility of H using other earlier sources, namely CC and D, it is important to address first the issue of the dating of the Pentateuchal scribal activity.

1 Dating Pentateuchal Scribal Activity

1a Dating CC

The CC possibly fits the eighth-century BCE dating. This view is based on the relations between the CC, Deuteronomic Code (DD), the Vassal Treaties of Esarhaddon (VTE), the Laws of Hammurabi and the Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions. The idea that DD is dependent on CC presupposes that CC was revised by D to make the laws of CC relevant in a different context.28 However, the direction of revision is debatable. The point that holds though is that Deut 15:12-18 is both consistent and inconsistent with Exod 21:2-11. First, worthy of consideration is the direction in which D revised CC. Whilst CC suggests that the legal ritual of the changing of the debt-slave's status from a temporary to a permanent slave was to take place in the sanctuary, D prescribes that it occur at the owner's home.29 In this case, either D revised the position of the CC or the other way round. In addition, unlike CC (Exod 21:2-6), D foregrounds the law in the Israelites' experience of divine manumission from slavery in Egypt (Deut 15:15).30 Furthermore, as Wright opines, D changed CC's call to leave the crops in the field for the poor to purely a release of debt slave and relief from debts in the cycle of seven years (see Deut 15:1-11; Exod 23:10-11).31 Attempting to address the issue of poverty and establishing an annual subvention for the poor, "D kept a version of CC's agricultural subsidy for the poor in prescribing that they be allowed to gather produce left in the field or vineyard after harvesting."32Thus, D focused on CC's apodictic laws that featured primarily "the themes of the cult, the poor, and justice (the poor: Exod 22:20-26; 23:9-12; the cult: 20:2326; 22:28-30; 23:14-18; justice: 23:1-8)."33

On the alternative claim that CC is dependent on D, Van Seters34 argues that the laws of CC were composed during the exilic period in Babylonia by the Yahwist author (non-P)35 who used the material of D and H as paradigms.36 Van Seters' thesis is weakened by the point that the so-called Yahwist (non-P) was also the author of the casuistic case laws in Exod 21:1-22:16 and there are no such laws in Deuteronomy. Furthermore, the exilic dating of the reception of the Laws of Hammurabi by the so-called Yahwist (non-P) is not convincing, as the use of the laws only happened in the neo-Assyrian period between 740 and 640 BCE.37

On the scribal and chronological levels, since "CC and its narrative may be seen as setting the stage for D's more explicit and extended use of Neo-Assyrian treaty and loyalty oaths,"38 D is proximate to CC. Based on the probability of D's use of VTE, which "provides a relatively secure guide for dating basic Deuteronomic laws to the second half of the seventh century BCE," the dating of CC to the first half of the seventh century is reasonable.39 Therefore, CC cannot be much earlier than D. At the least, CC is likely forty or fifty years earlier than the first edition of the Deuteronomic Code.40 Furthermore, because of the point that the Laws of Hammurabi41 were used by various scribes only between 740 and 640 BCE, an eighth century BCE dating of CC may therefore not be ruled out. The CC is consistent with the laws and the inscriptions. The influence of Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions on CC is glaring. The CC's appendix in Exod 23:20-33 was influenced by Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions.42 Exodus 23:20-33 not only shares "the motifs of the deity or his avatar going before the people or army (the vanguard motif)" and displays the divine presence as well as the conquest of foreign land, the appendix also provides theological legitimisation for the laws of the CC.43 The point that the influence of Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions on CC's appendix is dated from the beginning of the seventh to the eighth century BCE allows for the dating of CC to later eighth century BCE.44 It is therefore likely that the socio-economic issues in CC reflect the response of the non-P to the realities of the eighth century BCE in Judea.

1b Dating D

Dating the Pentateuchal text by external and internal comparisons seems to be reliable.45 The similarities between the loyalty oath (adê) of Esarhaddon discovered in the temple of Tayinat and Deut 28 suggest that the authors of the first version of Deuteronomy influenced Neo-Assyrian texts, which can be "dated quite precisely to 672" BCE.46 This connection hints at a seventh-century date for the core of the book of Deuteronomy.47 However, the sixth and fifth century dates for the edition and revision of the book remain plausible.48 As such, D was possibly composed in the pre-exilic period and later revised in both the exilic and post-exilic periods.49 The argument is consistent with the views of Otto and Römer. Otto argues that, "If we agree with Römer's perspective that the Deuteronomistic scrolls of the preexilic period were originally independent literary units, then the question becomes central how these scrolls grew together and became a literary unit."50 The latter conditional statement suggests a pre-exilic dating for the first layer of D.51 Noth's dating however contrasts with the pre-exilic dating of D. Noth is of the view that D was only active in the late exilic period under the neo-Babylonian reign52 based on apparent parallels between the end of the Deuteronomistic History (DH) and the last chapter of Kings (2 Kgs 25:27-30), which narrates the release of Jehoiachin from the Babylonian exile. If one considers Noth's position, on the one hand and Otto's claim that D was revised in the late exilic and post-exilic period, on the other, then, Römer's claim of a pre-exilic dating of D seems plausible. Nuancing his argument, Römer asserts that, "it is clear that Hezekiah's reign constitutes a first climax in the DH. But it is quite difficult to assume that there was a first edition of the DH that ended somewhere in 2 Kings 18-20."53 Römer places D at the time of Hezekiah's reign based on the statement in 2 Kgs 22:5 that, "There was no one like him [Hezekiah] among all the kings of Judah after him, or among those who were before him." If 2 Kgs 22 is a distinct D text, as I am inclined to accept, then, there is a clear presupposition of Hezekiah's reign (716-687 BCE) in the works of D. Moreover, Prov25:1 hints at an intense scribal activity during the reign of Hezekiah, "Therefore, one cannot rule out the possibility of dating D to Hezekiah's reign."54 That 2 Kgs 22-23 points to Josiah's reign (640-608 BCE) also implies the period of Hezekiah and supports a pre-exilic dating of D. The latter text supports the plausibility of the composition of D in the period of Josiah's rule. In addition, dating D's activity to the time of Hezekiah and Josiah makes sense especially when one considers 2 Kgs 19:5-7, which mentions Hezekiah's ownership of slaves. The text suggests a practice of acquiring and owning slave, which D strongly condemns. The typical D noun  (remission) and the release of slaves (Deut 15:12) supports a dating of D's activity to the time of Hezekiah. Thus, D was probably active during the rule of Hezekiah and was later documented at the time of Josiah.

(remission) and the release of slaves (Deut 15:12) supports a dating of D's activity to the time of Hezekiah. Thus, D was probably active during the rule of Hezekiah and was later documented at the time of Josiah.

As aforementioned, the first layer of D was likely revised in the exilic and post-exilic periods.55 The point that the Israelites who were deported to Babylonia lost their homeland56 suggests that a late exilic or an early post-exilic dating of the revisions of D about the promise of land resonates with a community that did not possess land. In Deut 1:8, D states: "See, I have set the land before you; go in and take possession of the land that I swore to your ancestors, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, to give to them and to their descendants after them." Deuteronomy 6:10 also states: "When the Lord your God has brought you into the land that he swore to your ancestors, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, to give you - a land with fine, large cities that you did not build."57 These texts present Judeans as landless and as a community which had a promise to possess the land. Locating these references to the promises of the land at a time when people did not possess land is reasonable. The promise of land "would have been of immediate relevance to those who aspired to return to Judah in the late neo-Babylonian or early Persian period."58 A dating of the earlier version of D to the pre-exilic period and of the subsequent revisions both in the exilic and post-exilic periods is therefore plausible. Based on the supposition that H read and used earlier sources, a discussion of the dating of H is warranted.

1c Dating H

Against Milgrom's position59 that the origins of H lie in the eighth century as well as Knohl's arguments60 of a pre-exilic dating, which is based on the view that the exile mentioned in Lev 26 was to Assyria and not to Babylonia,61 Meyer supports a post-exilic dating for H.62 The disregard of the possibility that both Lev 25 and 26 refer to the Babylonian exile and a liberated people weakens Knohl's argument.63 Grünwaldt and Otto argue for a late exilic dating of H (the second half of the sixth century BCE) based on the view that H used earlier traditions such as P, CC and D.64 In my view, a convincing argument for a late exilic dating lies in H's futuristic presentation of the Sabbath year in Lev 25:2b. The text addresses "those who are about to receive the land"65 that is given to them by  (the Lord). Thus, a late exilic date for H is likely.

(the Lord). Thus, a late exilic date for H is likely.

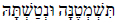

A post-exilic dating of H is also probable for two reasons. First, Lev 26, a text which forms part of the Holiness Code (Lev 17-26), suggests a post-exilic dating. Leviticus 26:13 reads, "I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, to be their slaves no more; I have broken the bars of your yoke and made you walk erect." Grünwaldt and Meyer consider a post-exilic dating for H because the Israelites are addressed as people who are already delivered.66The clauses  ("who brought you out of the land of Egypt") and

("who brought you out of the land of Egypt") and  ("and I have broken the bars of your yoke") support their claim. Leviticus 26:13 alludes to the liberation and/as deliverance from the Babylonian exile, represented by Egypt. The "theme of deliverance from Egypt, though originally P," was "re-used by H in both Lev 25 and 26."67 A post-exilic dating of H is therefore justifiable. Second, in Lev 25 H presents an "attempt by the élites to counter the loss of land and reclaim it after their liberation from the Babylonian exile"68 That the Babylonian exile of the Israelite ended in the fiftieth-year tallies with the fifty years cycle of the Jubilee is persuasive. The argument in favour of a post-exilic dating of H that is grounded on the association of the Jubilee cycle with the forty-nine years in exile, with the liberation on the fiftieth year makes sense. It is therefore possible that H was composed from the late exilic period to the post-exilic times.

("and I have broken the bars of your yoke") support their claim. Leviticus 26:13 alludes to the liberation and/as deliverance from the Babylonian exile, represented by Egypt. The "theme of deliverance from Egypt, though originally P," was "re-used by H in both Lev 25 and 26."67 A post-exilic dating of H is therefore justifiable. Second, in Lev 25 H presents an "attempt by the élites to counter the loss of land and reclaim it after their liberation from the Babylonian exile"68 That the Babylonian exile of the Israelite ended in the fiftieth-year tallies with the fifty years cycle of the Jubilee is persuasive. The argument in favour of a post-exilic dating of H that is grounded on the association of the Jubilee cycle with the forty-nine years in exile, with the liberation on the fiftieth year makes sense. It is therefore possible that H was composed from the late exilic period to the post-exilic times.

Against the background of the grammatical features, style and content of Lev 25:2-7 as well as the dating of the texts ascribed to non-P and D, sources earlier than H, we now investigate the inner-biblical exegesis in the final form of the Lev 25:2-7 in order to tease out socio-economic issues and the content of the Sabbatical year. The text bears some resemblance to other Pentateuchal texts, indicating that H and probably "the final redactor and redactions refer to the formation of the Pentateuch in terms of the reference to the Torah and the awareness of the entire Pentateuch."69 The discussion of the relations between Lev 25:2-7 and Exod 23:10-11 as well as Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18 is now in order.

2 Reception of Exod 23:10-11 in Lev 25:2-7

There is a resemblance between Lev 25:3 and Exod 23:10, both of which refer to the "six years" of crop production. On a linguistic level, they differ in the phrases  ("sow your field"; Lev 25:3) and

("sow your field"; Lev 25:3) and  ("sow your land"; Exod 23:10), meaning H explicitly locates the agricultural activity in the fields (productive land) instead of the "land." In addition, H inserts a command "prune your vineyard," whilst the statement is absent in Exod 23:10. The word "vineyard" is however mentioned in Exod 23:11 together with "olive grove." In Lev 25:2-7, H omits the reference to olives. Suffice to note, though, is the point that both texts allude to the six-year period of the productive use of the land and the reaping of its produce.

("sow your land"; Exod 23:10), meaning H explicitly locates the agricultural activity in the fields (productive land) instead of the "land." In addition, H inserts a command "prune your vineyard," whilst the statement is absent in Exod 23:10. The word "vineyard" is however mentioned in Exod 23:11 together with "olive grove." In Lev 25:2-7, H omits the reference to olives. Suffice to note, though, is the point that both texts allude to the six-year period of the productive use of the land and the reaping of its produce.

Additionally, Lev 25:4-5 and Exod 23:11 mention the seventh year of letting the land rest. The land shall  ("lie unplowed and unused").70The non-P author of Exod 23:11 explains why the land should be allowed to rest. It is so "that the poor among your people may get food from it, and the wild animals may eat what is left," but H omits this explanation. Verse 11 makes an explicit reference to "the poor among your people." The reference to the seventh year in both the texts relates to the provision of food. Leviticus 25:6-7 alludes to the provision of "food" and Exod 23:11 states that the poor people "may get food from it (the land)."71 The idea of letting the land rest in the seventh year is juxtaposed with the idea of providing food to the socio-economically underprivileged people, specifically from the produce of the six years of the productive use of the agricultural land. At first glance, it is unexpected of H to change the non-P phrase, "the poor among your people" (see Lev 25:6 and Exod 23:11). Nonetheless, worthy of note is H's insertion of the nouns:

("lie unplowed and unused").70The non-P author of Exod 23:11 explains why the land should be allowed to rest. It is so "that the poor among your people may get food from it, and the wild animals may eat what is left," but H omits this explanation. Verse 11 makes an explicit reference to "the poor among your people." The reference to the seventh year in both the texts relates to the provision of food. Leviticus 25:6-7 alludes to the provision of "food" and Exod 23:11 states that the poor people "may get food from it (the land)."71 The idea of letting the land rest in the seventh year is juxtaposed with the idea of providing food to the socio-economically underprivileged people, specifically from the produce of the six years of the productive use of the agricultural land. At first glance, it is unexpected of H to change the non-P phrase, "the poor among your people" (see Lev 25:6 and Exod 23:11). Nonetheless, worthy of note is H's insertion of the nouns:  ("and your male slave")

("and your male slave")  ("and your female slave")

("and your female slave")  ("and your hired worker") and

("and your hired worker") and  ("and your settler who is sojourning") indicates that H was more interested in socio-economic justice issues than in the economic status (that is, the poverty) of the people. Furthermore, Exod 23:11 refers to the "wild animals" that also ought to benefit from the distribution of the seventh year. For the non-P author of Exod 23:10-12, both the poor and the wild animals are to be cared for in the seventh year therefore H rehabilitates the non-P idea of providing food to the wild animals with an allusion to the "beasts" (Lev 25:7). For H, the cattle and beasts ought to be the beneficiaries in the Sabbath year, alongside the groups of people mentioned in Lev 25:2, 6.

("and your settler who is sojourning") indicates that H was more interested in socio-economic justice issues than in the economic status (that is, the poverty) of the people. Furthermore, Exod 23:11 refers to the "wild animals" that also ought to benefit from the distribution of the seventh year. For the non-P author of Exod 23:10-12, both the poor and the wild animals are to be cared for in the seventh year therefore H rehabilitates the non-P idea of providing food to the wild animals with an allusion to the "beasts" (Lev 25:7). For H, the cattle and beasts ought to be the beneficiaries in the Sabbath year, alongside the groups of people mentioned in Lev 25:2, 6.

In contrast to the six  (days) of work and rest for the Israelites, oxen, donkeys, slaves born in Israelite households and foreigners living among the Israelites, on the seventh

(days) of work and rest for the Israelites, oxen, donkeys, slaves born in Israelite households and foreigners living among the Israelites, on the seventh  (day) in Exod 23:12 and Lev 25:2-7 mentions the productive use of the land for

(day) in Exod 23:12 and Lev 25:2-7 mentions the productive use of the land for  (six years) and its rest on the seventh "year" (

(six years) and its rest on the seventh "year" ( ). For non-P, rest is not limited to the land; it extended to people and animals. It is either that H ignored the Exod 23:12 or the verse is a later insertion linked to verses 10-11 with the reference to "rest" as well as the numbers "six" and "seven." The idea of a sabbatical rest is nonetheless kept in verse 12 and the poor, slaves and foreign labourers are alluded to in Exod 23:1013. With the allusion to years rather than days, H is more realistic as it probably took time (maybe years) for people to lose productive land, be indebted to others and become slaves to the wealthy elites hence the departure from the non-P reference to "days."

). For non-P, rest is not limited to the land; it extended to people and animals. It is either that H ignored the Exod 23:12 or the verse is a later insertion linked to verses 10-11 with the reference to "rest" as well as the numbers "six" and "seven." The idea of a sabbatical rest is nonetheless kept in verse 12 and the poor, slaves and foreign labourers are alluded to in Exod 23:1013. With the allusion to years rather than days, H is more realistic as it probably took time (maybe years) for people to lose productive land, be indebted to others and become slaves to the wealthy elites hence the departure from the non-P reference to "days."

On the seventh day, when ordinary work is suspended in the fields and the agricultural land left uncultivated, the poor Judahites were permitted to harvest some crops from the land and glean from the vineyards as well as from the olive groves (Exod 23:10-11). Although the latter appears to be a caring gesture, one wonders whether the practice was enough to elevate the poor from poverty. I doubt. Economic inequality in the pre-exilic period and in the exilic and post-exilic epochs and the economic systems which were far from being consistently helpful to the poor may be deduced from Exod 23:10-11. Not only does Exodus 23:6, 11 acknowledge a class of poor people, the text also points to a stratified society with a law from an urban group of scribes, which according to Knight,72 sought "to use an agricultural practice as a means of offering relief to the poor, even though villagers as a whole were often not far from the poverty level themselves." In addition, Exod 23:10-11 points to the existence of subsistence economy in Judea to which the villagers were subjected.73

In the post-exilic context that has its closest parallel to the pre-exilic one reflected in Exod 23, H drew on and equally departed from the contents of the non-P material to address the issues of the Sabbath year and socio-economic injustice and hunger experienced by an economically stratified society.

3 Reception of Deut 11:8-17 in Lev 25:2-7

The relations between Lev 25:2-7 and Deut 11:8-17 show similarities and differences. In addition, they reveal the way H borrowed ideas from D and equally abandoned some of D's ideologies.

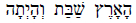

The possession of land by Israel and/or as Israelites is alluded to in Deut 11:8. Linguistically, the possession of land by Israel in verse 8 has a parallel in Lev 25:2 as H refers to the land that YHWH gives to the Israelites and maintains D's idea of Israel being given the land by YHWH. However, H refrains from explicitly mentioning  ("a land flowing with milk and honey"). This is far from suggesting that for H the land is not fertile. In fact, the phrase

("a land flowing with milk and honey"). This is far from suggesting that for H the land is not fertile. In fact, the phrase  ("and the sabbath produce of the land"; Lev 25:6) and the reference to

("and the sabbath produce of the land"; Lev 25:6) and the reference to  ("the produce") in verse 6 confirm the fertility of the productive land - the fields.

("the produce") in verse 6 confirm the fertility of the productive land - the fields.

The agricultural activity of sowing mentioned in Deut 11:11 is equally mentioned in Lev 25:3. However, in Deuteronomy, the verb,  (sow) is used in the context of reference to activities in Egypt and D picks up the memory of Israel in Egypt (Deut 11:10) and highlights that YHWH provided rain to land (hills and valleys) given to the Israelites (Deut 11:11). Contrary to Deut 11:1112, wherein YHWH cares for the land, H introduces the idea that the Israelites should take care of the land by letting it rest (Lev 25:4-5). In H, an ethical practice of caring for the land is intertwined with the religious observation of the Sabbath for the Lord.

(sow) is used in the context of reference to activities in Egypt and D picks up the memory of Israel in Egypt (Deut 11:10) and highlights that YHWH provided rain to land (hills and valleys) given to the Israelites (Deut 11:11). Contrary to Deut 11:1112, wherein YHWH cares for the land, H introduces the idea that the Israelites should take care of the land by letting it rest (Lev 25:4-5). In H, an ethical practice of caring for the land is intertwined with the religious observation of the Sabbath for the Lord.

The conditional statement of Deut 11:14, "that I will give the rain of your land in its season," suggests a seasonal absence of rain. Thus, H omits this conditional statement. During the seasons of rain, the Israelites can gather in their grain, new wine, and olive oil and H keeps D's idea of gathering in the grain for produce in the reference to sowing the "field," pruning the "vineyard" and gathering the "produce thereof during the six-year period (Lev 25:3) as well as in the allusion to the "sabbath-produce of the land" reserved for food (Lev 25:6). Furthermore, verses 14 and 17 in Deut 11 are related by means of the reference to rain. Deuteronomy 11:17 suggests that if Israel is not faithful in her relations with YHWH, the consequence will be the absence of rain and food. Here, a form of a drought is insinuated, which is caused by human behaviour that infuriates YHWH. Due to climate change, that is, drought (absence of rain), the ground ceases to yield fruit. Although Deut 11:8-17 is related to Lev 25:2-7, as shown above, the absence of rain is not mentioned by H, which is concerned primarily with the observation of the Sabbath year and the socio-economic issues (especially the provision of food to the economically underprivileged) linked to this religious observation.

Deuteronomy 11:8-17 is also related to Lev 25:2-7 with the reference to the fields and cattle. Although on a linguistic level, Deut 11:15 is not identical with Lev 25:7, the provision of food accrued from crop production to livestock and the agricultural activity of livestock farming are related. The rain and grass are provided by YHWH (Deut 11:14-15). In an implied instance in this D text, where the rain is not available, food would equally cease to be available for the Israelites. In H, the depiction of a stratified community which is constituted by the slaves, hired worked, foreign nationals and owners of the agricultural land, presupposes that socio-economic inequality and injustice are the causes of unavailability of food and/as hunger. The difference between Lev 25:2-7 and Deut 11:8-17 also lies in the phrase "shall eat and be satisfied" (Deut 11:15) and H's explicit mention of "food." Inconsistent with D, H highlights the presupposed problem of hunger that was probably experienced by the groups of people mentioned in Lev 25:6.

4 Reception of Deut 15:7-18 in Lev 25:2-7

Unlike Deut 15 in which D mentions the needy and/or as poor "Israelites" (v. 7), "your people-Hebrew men or women" (v. 12) and "servant" (vv. 16-18), H deliberately and explicitly mentions "male slave," "female slave," "hired worker" and "settler who is sojourning" (Lev 25:6). Deuteronomy 15:7-18 commands that on the seventh year the socio-economically underprivileged be cared for in terms of being released74 from work and be given produce from the land. However, for H, the emphasis around the seventh year is not on the remission of slaves, but on the provision of food to the groups of people cited in Lev 25:6 and animals mentioned in verse 7, because the noun  "remission" is omitted in Lev 25:2-7. The point in verse 6 that the slave (

"remission" is omitted in Lev 25:2-7. The point in verse 6 that the slave ( ) is not released on the seventh year but given food shows that H is reluctant to adopt D's idea of remission completely. In both of these texts, the idea of the seventh year is coupled with socio-economic relief, which was to be enacted by the provision of food. Furthermore, on the issue of

) is not released on the seventh year but given food shows that H is reluctant to adopt D's idea of remission completely. In both of these texts, the idea of the seventh year is coupled with socio-economic relief, which was to be enacted by the provision of food. Furthermore, on the issue of  ("remission"), Nihan remarks:

("remission"), Nihan remarks:

While Deut 15:1-18 reinterprets the seven-year cycle of Ex 23:10-11 by transforming the

"remission"75 from an instruction on the fallow land with a social dimension (whatever grows upon it may be eaten by needy persons) into a purely socio-economic instruction (debt-release in the seventh year) with no agricultural implication, and by combining it explicitly with the instruction on slave-release every seven years found in Ex 21:2-11 (cf. Deut 15:12-18), Lev 25, on the contrary, rehabilitates against D an interpretation of the seventh year as serving exclusively for the "rest" of the land (v. 2-7). The law of 25:2-7 is clearly modelled upon Ex 23:10-11, as various scholars have noted.76

The remark confirms H's awareness of the material of D. Not only does H primarily focus on the "rest" of the land, as Nihan contends, H is also concerned about religious and socio-economic issues.

According to D, the failure to obey the Sabbatical regulations in the seventh year bears a consequence. However, the consequence in Deut 15:9 is not explicitly mentioned, but indicated with the consequential statement,  ("and you will be found guilty of sin"). One could assume that the consequence of sin is scarcity of food or drought. However, such a consequence is not explicitly mentioned in the text and H omits both the reference to being found guilty and the presupposition of a consequence for a failure of disobeying YHWH.

("and you will be found guilty of sin"). One could assume that the consequence of sin is scarcity of food or drought. However, such a consequence is not explicitly mentioned in the text and H omits both the reference to being found guilty and the presupposition of a consequence for a failure of disobeying YHWH.

The release of the slaves (a Hebrew man or a Hebrew woman sold to the Israelites) in Deut 15:12 and the hired servant in verses 17-18 is set on the seventh year. Since slaves and hired servants often worked the land, it may not be farfetched and unreasonable to imagine that during their release, the land is left unworked. Therefore, the idea of letting the land rest (cf. Lev 25:4-5) may cautiously be read into the time of the release of slaves and hired servants. However, unlike D, H explicitly cites the concept as the idea of letting the land rest. For H, this religious practice is important on the Sabbath year in the same way that the provision of food to the people (Lev 25:6) and animals (Lev 25:7) is crucial.

In both Deut 15:10, 14 and Lev 25:2-3, 5-7, YHWH blesses the Israelites with crops and livestock, from which a portion is to be given to the socio-economically disadvantaged people. Deuteronomy 15:10 includes a consequential statement, "then because of this the Lord your God will bless you in all your work and in everything you put your hand to," whilst verse 14 mentions "flock," "threshing floor" and "winepress" with which YHWH blesses the Israelites. In Lev 25:2, YHWH blesses the Israelites with residential and productive land where "they sow their field," "prune their vineyard" and "gather in the produce thereof (Lev 25:3). Additionally, H presupposes harvest and mentions "grapes of your undressed vine" (Lev 25:5), "sabbath-produce of the land" (Lev 25:6) and "cattle" as well as "beasts" (Lev 25:7). Linguistically, the texts are different but equally capture a similar idea of YHWH blessing the Israelites with agricultural produce during the six years of working the land.

The discussion of the scribal scholarship in the formation of Lev 25:2-7, which focuses on the dating of the composition and redaction of CC, D and H as well as the closest parallels of the text in Exod 23:10-11, Deut 11:8-17 and Deut 15:7-18, may be summarised at this point. The review of the dating of the scribal works of CC, D and H reveals that H is younger and that H interpretively revised, reused, expanded and applied the non-P text (Exod 23:10-11) as well as D material (Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18) in the late exilic and post-exilic period. The significance of the Sabbath year is highlighted by H who also theologically legitimised some socio-economic activities by linking them to the year. Further, H juxtaposed the Sabbath year regulations and the socio-economic issues to address the problem of hunger in Lev 25:2-7. For H, various groups of people were to receive food in the Sabbath year-ranging from the Israelites who were promised the agricultural land, to the owners of land, the male and female slaves, the hired workers and the settlers who sojourned among the Israelites as well as the animals and beasts.

D RECEPTION OF LEV 25:2-7 IN NEHEMIAH

Based on the grammatical features, style and content of Lev 25:2-7 as well as the scribal formation of the text, the religious and socio-economic importance of the H material is undeniable, as confirmed by instances where other post-exilic authors consulted and used Lev 25:2-7 in their writings. The content of Lev 25:2-7 as well as the religious and socio-economic situation presupposed in the text has its closest parallel in Neh 5 which mentions measures for preventing the exploitation of the poor peasants by the Persian imperialist and the Judean elites.77 Nehemiah 9:32-37 alludes to the socio-economic injustice experienced by the Judeans in the post-exilic Persian period and Neh 13 focuses on the "restoration of the Levites' privileges and service, the stressing of keeping the sabbath and actions against those with foreign wives."78 The widely accepted view that the authors of Ezra-Nehemiah were familiar with the material of D, CC and H and considered them normative79 and the relations between the material of H and Nehemiah suggest that the author of Nehemiah used H as a source. Moreover, because of the possibility of a late exilic composition of H (which is earlier than the composition of Nehemiah) and its post-exilic finalisation, it is likely that the author of Nehemiah was aware and used the material of H. The differences between Lev 25:2-7 and the book of Nehemiah also suggest that the authors of Nehemiah drew and equally departed from H's ideology by omitting and adding some content.

As mentioned above, in Lev 25:2-7, H addressed the Israelites who were about to receive land (v. 2b), those who possessed and had power over the agricultural land (vv. 3-4) and various groups of economically underprivileged people who needed food (v. 6). Unlike H, the author of Nehemiah adds various groups of people including, but not limited to, the Judeans with a "great outcry" and Judeans in a position of power (Neh 5:1); "We" - the Judean returnees, their sons and daughters who were in need of grain or food (Neh 5:2); money borrowers (Neh 5:4); kings who received tax (Neh 5:4; 9:37); sons and daughters of Judeans who became slaves (Neh 5:4-5; cf. 9:37)80 and ancestors (Neh 9:36).

Nehemiah raises the problem of the need for grain (by implication food) in the socio-economic situation in the post-exilic context. Nehemiah 5:2 states:

"We and our sons and daughters are numerous; in order for us to eat and stay alive, we must get grain." The text mentions the lack of access to grain (by implication food) and the threat of hunger and prospects of death. Regarding Neh 5:3, "Others were saying, 'we are mortgaging our fields, our vineyards, and our homes to get grain during the famine' ," Altmann opines that the phrase "food shortage" is more fitting than "famine," "given that famine entails mass starvation, which was not likely to have been widespread" and because the text provides "no indication of human death as a result of this situation."81 However, the food shortage was severe and distressing because Neh 5:2 indicates the need for grain to eat in order to stay alive. Verse 3 mentions the need for food (grain), a point that is raised by H in Lev 25:6-7.

Further supplements to the H material are the causes of the need for grain, that is, hunger. Neh 5:4-5 reads:

We have had to borrow money to pay the king's tax on our fields and vineyards. Although we are of the same flesh and blood as our fellow Jews and though our children are as good as theirs, yet we have to subject our sons and daughters to slavery. Some of our daughters have already been enslaved, but we are powerless, because our fields and our vineyards belong to others.

The author of Nehemiah cites the payment of tax on the fields and vineyards to the king, indebtedness and powerlessness as the causes of their impoverishment. As Nihan observes, the "Judean landowners are forced to sell their ancestral estate and, ultimately, become indentured slaves working on the estate of other, wealthy Judeans."82 Furthermore, Neh 5:7 refers to the nobles and officials who are accused of the oppression and exploitation of the less privileged and the poor. Instead of documenting the law as H does, the author of Nehemiah presents an accusation against the oppressors and exploiters. Contrary to Lev 25:2-7, Neh 5:11 additionally provides an instruction to the economic exploiters to "give back to them (exploited less privileged Judeans)83 their fields, vineyards, olive groves and houses and also the interests they84 are them - one percent of the money, grain, new wine and olive oil." Not only does the text address the exploitation of the poor and subsequent hunger, but it also restores the access of the peasants to the means of production and the market. Nehemiah's reaction and response to the cry of the people of Judah because of hunger, heavy taxation, indebtedness, loss of agricultural productive land and enslavement is different from that of H in Lev 25:2-7. Unlike H, Nehemiah includes a command to stop charging interest on the fields that the elites hire out to the suffering peasants (Neh 5:10)85and an instruction to return the fields, vineyards, olive groves, houses, silver and grain, new wine, and oil that the wealthy elites lent on interest to the economically less privileged people of Judah (Neh 5:11). However, H addressed the problem of hunger by highlighting the importance of keeping the Sabbath year (Lev 25:2, 4, 6), productively working the land (Lev 25:3) and giving food to the "male slave," "female slave," "hired worker," "settler who is sojourning" and "cattle and beasts" (Lev 25:6).

Both H and the authors of Nehemiah refer to the  (sabbath). Contrary to Lev 7:2-7, Neh 13:15-22 alludes to the Sabbath day instead of the Sabbath year. Here, the text of Neh 13:16-17 has closest parallel with Exod 23:12 where the Sabbath day is mentioned. Nehemiah describes as "desecrating the Sabbath day" (Neh 13:17) economic activities and transactions such as treading winepresses, bringing in grain, loading it on donkeys and selling food (Neh 13:15) as well as selling fish and all kinds of merchandise in Jerusalem on the Sabbath to the people of Judah (Neh 13:16). Nehemiah spoke against the people of Judah, possibly the natives (Neh 13:15), the people from Tyre who were selling fish (Neh 13:16) and the nobles of Judah who were associated with the Judean ancestors (Neh 13:18). I concur with both Edelman and Altmann that the people addressed by Nehemiah represented multiple religious-ethnic groups.86The juxtaposition of the denunciation of the economic activities and transactions with the keeping of Sabbath probably aimed at upholding the ethnic-religious Judean identity in the Persian context of multiple religious-ethnic groups. The reference to the Sabbath therefore strengthens the criticism, especially of the Judeans. Regarding Lev 25:2-7, H's response to hunger in verse 6 is equally strengthened by its place within the Sabbath year legislation. Both Lev 7:2-7 and Neh 13:15-22 uphold the religious importance of the Sabbath. Like H, the author of Nehemiah juxtaposes the socio-economic issues with the religious practice of observing the Sabbath by objecting to economic activities on the Sabbath day and in the Sabbath year, respectively.

(sabbath). Contrary to Lev 7:2-7, Neh 13:15-22 alludes to the Sabbath day instead of the Sabbath year. Here, the text of Neh 13:16-17 has closest parallel with Exod 23:12 where the Sabbath day is mentioned. Nehemiah describes as "desecrating the Sabbath day" (Neh 13:17) economic activities and transactions such as treading winepresses, bringing in grain, loading it on donkeys and selling food (Neh 13:15) as well as selling fish and all kinds of merchandise in Jerusalem on the Sabbath to the people of Judah (Neh 13:16). Nehemiah spoke against the people of Judah, possibly the natives (Neh 13:15), the people from Tyre who were selling fish (Neh 13:16) and the nobles of Judah who were associated with the Judean ancestors (Neh 13:18). I concur with both Edelman and Altmann that the people addressed by Nehemiah represented multiple religious-ethnic groups.86The juxtaposition of the denunciation of the economic activities and transactions with the keeping of Sabbath probably aimed at upholding the ethnic-religious Judean identity in the Persian context of multiple religious-ethnic groups. The reference to the Sabbath therefore strengthens the criticism, especially of the Judeans. Regarding Lev 25:2-7, H's response to hunger in verse 6 is equally strengthened by its place within the Sabbath year legislation. Both Lev 7:2-7 and Neh 13:15-22 uphold the religious importance of the Sabbath. Like H, the author of Nehemiah juxtaposes the socio-economic issues with the religious practice of observing the Sabbath by objecting to economic activities on the Sabbath day and in the Sabbath year, respectively.

E CONCLUDING REMARKS

The hypothesis of the present article is that based on inner-biblical exegesis, not only did Lev 25:2-7 serve to legitimise the Sabbath tradition and address socioeconomic issues in the Persian period, but it also had an influence on some texts in the book of Nehemiah that exhibited related religious-ethnic and socioeconomic issues in the post-exilic context.

The study of the grammatical features, style and content of Lev 25:2-7 confirms that H was concerned with the religious aspect of the Sabbath tradition due to the reference to the Sabbath year and YHWH. In addition, H intertwined the economic allusion in the reference to "the produce" and food to highlight the need for the provision of food to various groups of economically less privileged people, namely the male and female slaves, hired workers and settlers who sojourned among the Israelites as well as to animals. The explicit mention of the groups of people depicts the stratified society in the Persian period that concerned H.

The close relationship between Lev 25:2-7 and the Pentateuchal texts (Exod 23:10-11; Deut 11:8-17; 15:7-18) as well as the post-exilic texts (Neh 5; 9:32-37; 13) served to highlight their similarities and differences. The relationships merely demonstrated that some receptor texts referred to older source texts. The dating of the Pentateuchal scribal activity, together with the grammatical features, style and content of texts indicated the direction of dependence between Lev 25:2-7 and Exod 23:10-11; Deut 11:8-17 and 15:718. Furthermore, employing inner-biblical exegesis as a methodological tool helped to determine how and why H interpretively revised, reused, expanded and applied older Pentateuchal sources to legitimise the Sabbath tradition and address socio-economic issues in the Persian period.

Inner-biblical exegesis allowed the inference that the author of Neh 5; 9:32-37 and 13 had a knowledge of and drew on Lev 25:2-7. The present essay finds that the author of the book of Nehemiah expanded the material of H, omitted some content, provided explanatory comments to abstracted issues and transformed certain contents. In addressing the socio-economic issues in the Persian period, the author of Nehemiah added the possible causes of the need for food or grain, namely the payment of tax on the fields and vineyards to the king, indebtedness, the loss of agricultural land and the powerlessness of some Judeans. Unlike H, Nehemiah addresses the causes and the supposed problem of hunger by including command statements and instructions. The Nehemiah author commanded the oppressors and exploiters to stop charging the suffering peasants interest on the hired fields (Neh 5:10) and to return the fields, vineyards, olive groves, houses, silver and grain, new wine and oil to the economically less privileged people of Judah (Neh 5:11). In the post-exilic Persian context of multiple religious-ethnic groups, the author of Nehemiah juxtaposed the critique of economic activities with the keeping of Sabbath to uphold the ethnic-religious Judean identity and address socio-economic issues. The author also drew on Lev 25:2-7 by keeping the allusions to the Sabbath and maintaining the association of the Sabbath with YHWH to support the Sabbath tradition.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertz, Rainer. "A Possible Terminus ad Quem for the Deuteronomic Legislation? A Fresh Look at Deut. 17:16." Pages 271-296 in Homeland and Exile: Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of Bustenay Oded. Edited by Gershon Galil, Markham Geller and A. Millard. Vetus Testamentum Supplement Series 130. Leiden: Brill, 2009. [ Links ]

Altmann, Peter. Economics in Persian-Period Biblical Texts: Their Interactions with Economic Developments in the Persian Period and Earlier Biblical Traditions. Vol. 109. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

Baden, Joel S. J, E, and the Redaction of the Pentateuch. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 68. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Identifying the Original Stratum of P: Theoretical and Practical Considerations." Pages 13-30 in The Strata of the Priestly Writings: Contemporary Debate and Future Directions. Edited by Sarah Shectman and Joel S. Baden. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, 2009. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Continuity of the Non-Priestly Narrative from Genesis to Exodus." Biblica 93/ 2 (2012): 161-186. [ Links ]

Bar-Asher, Moshe. "The Bible Interpreting Itself." Pages 1-18 in Rewriting and Interpreting the Hebrew Bible: The Biblical Patriarchs in the Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Edited by Devorah Diamant and Reinhard G. Kratz. BZAW 439. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2013. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "Was the Pentateuch the Civic and Religious Constitution of the Jewish Ethnos in the Persian Period?" Pages 41-62 in Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch. Edited by James W. Watts. Symposium Series 17. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2001. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Abraham as Paradigm in the Priestly History in Genesis." Journal of Biblical Literature 128/2 (2009): 225-241. [ Links ]

Blum, Erhard. Studien zur Komposition des Pentateuch. BZAW 189. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1990. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. Cadences of Home: Preaching among Exiles. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Chirichigno, Gregory C. Debt-Slavery in Israel and the Ancient Near East. JSOTSS 141. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Edelman, Diana Vikander. "Tyrian Trade in Yehud under Artaxerxes I: Real or Fictional? Independent of Crown Endorsed?" Pages 207-246 in Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period. Edited by Oded. Lipschits and Manfred Oeming; Winona Lake, Eisenbrauns, 2006. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Inner-Biblical Exegesis: Types and Strategies of Interpretation in Ancient Israel." Pages19-37 in Midrash and Literature. Edited by Geoffrey H. Hartman and Sanford Budick. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986. [ Links ]

Gertz, Jan C. "Deuteronomy and the Covenant Code and Their Cultural and Historical Contexts: Hermeneutics of Law and Innerbiblical Exegesis." Zeitschrift für Altorientalische und Biblische Rechtsgeschichte/Journal for Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical Law 25/1 (2019): 187-194. [ Links ]

Grünwaldt, Klaus. Das Heiligkeitsgesetz Leviticus 17-26: Ursprüngliche Gestalt, Tradition und Theologie. Vol. 271. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1999. [ Links ]

Guillaume, Philippe. "Nehemiah 5: No Economic Crisis." The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 10 (2010): 1 -21. [ Links ]

Knight, Douglas A. "'Village Law and the Book of the Covenant." Pages 163-179 in "A Wise and Discerning Mind": Essays in Honor of Burke O. Long. Edited by Saul M. Olyan and Robert C. Culley. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2000. [ Links ]

Knohl, Israel. The Sanctuary of Silence: The Priestly Torah and the Holiness School. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Lauinger, Jacob. "Esarhaddon's Succession Treaty at Tell Tayinat: Text and Commentary." Journal of Cuneiform Studies 64/1 (2012): 87-123. [ Links ]

Lemche, Niels P. "The Manumission of Slaves: The Fallow Year, the Sabbatical Year, the Yobel Year." Vetus Testamentum 26/1 (1976): 38-59. [ Links ]

Levinson, Bernard M. Deuteronomy and the Hermeneutics of Legal Innovations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Reconceptualization of Kingship in Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomistic History's Transformation of the Torah." Vetus Testamentum 51/4 (2001): 511-534. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Is the Covenant Code an Exilic Composition? A Response to John Van Seters." Pages 272-352 in In Search of Pre-exilic Israel. Edited by John Day. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2004. [ Links ]

López, F. Garcia. "Le Roi d'Israël: Dt 17,14-20." Pages 277-297 in Das Deuteronomium: Entstehung, Gestalt und Botschaft. Edited by Norbert Lohfink. BEThL 68. Leuven: Peeters, 1985. [ Links ]

Meek, Russell L. "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology." Biblica 95/1 (2014): 280-291. [ Links ]

Meyer, Esias E. The Jubilee in Leviticus 25: A Theological Ethical Interpretation from a South African Perspective. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2005. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Dating the Priestly Text in the Pre-Exilic Period: Some Remarks about Anachronistic Slips and Other Obstacles." Verbum et Ecclesia 31/1 (2010): 16. [ Links ]

Milgrom, Jacob. "The Antiquity of the Priestly Source: A Reply to Joseph Blenkinsopp." Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 111/1 (1999): 10 -22. [ Links ]

_______________________. Leviticus 23-27: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (AB 3A). New York: Doubleday, 2001. [ Links ]

Mtshiselwa, Ndikho. To Whom Belongs the Land? Leviticus 25 in an African Liberationist Reading. New York: Peter Lang, 2018. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Formation of the Wilderness Narratives in the Book of Numbers." Pages 237-272 in The Social Groups Behind the Pentateuch. Edited by Jaeyoung Jeon. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2021. [ Links ]

Nicholson, Ernest W. "'Do not Dare to Set a Foreigner over You': The King in Deuteronomy and 'The Great King'." Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 118/1 (2006): 46-61. [ Links ]

Nihan, Christophe. From Priestly Torah to Pentateuch: A Study in the Composition of the Book of Leviticus. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Resident Aliens and Natives in the Holiness Legislation." Pages 111-134 in The Foreign and the Law: Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. Edited by. Reinhard Achenbach, Rainer Albertz and Jakob Wöhrle. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2011. [ Links ]

Noth, Martin. The Deuteronomistic History. JSOTSS 15. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Otto, Eckart. "The Pre-Exilic Deuteronomy as a Revision of the Covenant Code." Pages 112-122 in Kontinuum und Proprium: Studien zur sozial- und rechtsgeschichte des Alten Orients und des Alten Testaments. Edited by Eckart Otto. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. [ Links ]

_______________________. Das Deuteronomium: Politische Theologie und Rechtsreform in Juda und Assyrien. BZAW 284. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1999a. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Innerbiblische Exegese im Heiligkeitsgesetz Levitikus 17-26." Pages 125196 in Levitikus als Buch. Edited by Heinz-Josef Fabry and Hans-Winfried Jüngling. Berlin: Bonner Biblische Beiträge, 1999b. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Review of John Van Seters, A Law Book for the Diaspora. Revision in the Study of the Covenant Code" Biblica 85/2 (2004): 273-277. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Ersetzen oder Ergänzen von Gesetzen in der Rechtshermeneutik des Pentateuch." Pages 248-256 in Die Tora: Studien zum Pentateuch: Gesammelte Schriften (Aufsätze). Edited by Eckart Otto. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für altorientalische und biblische Rechtsgeschichte 9. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2009. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Holiness Code in Diachrony and Synchrony in the Legal Hermeneutics of the Pentateuch." Pages 135-156 in The Strata of the Priestly Writings: Contemporary Debate and Future Directions. Edited by Sarah Shectman and Joel S. Baden. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, 2009b. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Torah and Prophecy: A Debate of Changing Identities." Verbum et Ecclesia 34/2 (2013): 1-5. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Book of the Covenant." Pages 68-77 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Law. Edited by Brent A. Strawn. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Petersen, David L. "Zechariah 9-14: Methodological Reflections." Pages 210-224 in Bringing out the Treasure: Inner Biblical Allusion in Zechariah 9-14. Edited by Mark J. Boda and Michael H. Floyd. JSOTSS 370. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2003. [ Links ]

Ro, Johannes Unsok. Poverty, Law and Divine Justice in Persian and Hellenistic Judah. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2018. [ Links ]

Römer, Thomas. The So-called Deuteronomistic History: A Sociological, Historical and Literary Introduction. London: T & T Clark International, 2005. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Elusive Yahwist: A Short History of Research." Pages 9-28 in A Farewell to the Yahwist? The Composition of the Pentateuch in Recent European Interpretation. Edited by Thomas B. Dozeman and Konrad Schmid. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2006. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Redaction Criticism: Hebrew Bible." Pages 223-232 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Steven L. McKenzie. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

_______________________. "How to Date Pentateuchal Texts: Some Case Studies." Pages 357-370 in The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Edited by Jan C. Gertz, Bernard M. Levinson, D. Dalit Rom-Shiloni and Konrad Schmid. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

Rugwiji, Temba. "Appropriating Judean Post-Exilic Literature in a Postcolonial Discourse: A Case for Zimbabwe." Ph.D. thesis. University of South Africa, 2013. [ Links ]

Scheffler, Eben. Politics in Ancient Israel. Pretoria: Biblia Publishers, 2001. [ Links ]

Schmid, Konrad. "The So-called Yahwist and the Literary Gap between Genesis and Exodus." Pages 29-50 in A Farewell to the Yahwist? The Composition of the Pentateuch in Recent European Interpretation. Edited by Thomas B. Dozeman and Konrad Schmid. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2006. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Late Persian Formation of the Torah: Observations on Deuteronomy 34." Pages 236-245 in Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Edited by Obed Lipschits, Gary N. Knoppers, and Rainer Albertz. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007. [ Links ]

Schwartz, Baruch J. "'Profane' Slaughter and the Integrity of the Priestly Code." Hebrew Union College Annual 67/1 (1996): 15-42. [ Links ]

_______________________. The Holiness Legislation: Studies in the Priestly Code. Jerusalem: Magnes, 1999. [ Links ]

Smith, Daniel L. The Religion of the Landless: The Social Context of the Babylonian Exile. Bloomington: Meyer Stone Books, 1989. [ Links ]

Spangenberg, Izak. "The Literature of the Persian Period (539-333 BCE)." Pages 168198 in Ancient Israelite Literature in Context. Edited by Willem Boshoff, Eben Scheffler and Izak Spangenberg. Pretoria: Pretoria Book House, 2011. [ Links ]

Stackert, Jeffrey. Rewriting the Torah: Literary Revision in Deuteronomy and the Holiness Legislation. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Holiness Legislation and Its Pentateuchal Sources: Revision, Supplementation, and Replacement." Pages 187-205 in The Strata of the Priestly Writings: Contemporary Debate and Future Directions. Edited by Sarah Shectman and Joel S. Baden. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, 2009. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Distinguishing Innerbiblical Exegesis from Pentateuchal Redaction: Leviticus 26 as a Test Case." Pages 369-386 in The Pentateuch: International Perspectives on Current Research. Edited by Thomas B. Dozeman, Konrad Schmid and Baruch J. Schwartz. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011. [ Links ]

Steymans, Hans Ulrich. Deuteronomium 28 und die adê zur Thronfolgeregelung Asarhaddons: Segen und Fluch im Alten Orient und in Israel. Vol. 145. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1995. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Die neuassyrische Vertragsrhetorik der 'Vassal Treaties of Esarhaddon' und das Deuteronomium." Pages 89-152 in Das Deuteronomium. Vol. 23. Edited by Georg Braulik. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2003. [ Links ]

Usue, Emmanuel O. "Restoration or Desperation in Ezra and Nehemiah? Implications for Africa." Old Testament Essays 20/3 (2007): 830-846. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, Christo H., Jacobus A. Naudé, and Jan H. Kroeze,. A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 1999. [ Links ]

van Deventer, Hans JM. "'n 'Groen' Israel: Ekologiese Rigtingwysers uit Levitikus 25:1-7." In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi 30/2 (1996): 185-202. [ Links ]

Van Heerden, S. Willie. "Taking Stock of Old Testament Scholarship on Environmental Issues in South Africa: The Main Contributions and Challenges." Old Testament Essays 22/3 (2009): 695-718. [ Links ]

Van Seter, John. A Law Book for the Diaspora: Revision in the Study of the Covenant Code. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Wells, Bruce. "Review of Eckart Otto, Die Tora: Studien zum Pentateuch -Gesammelte Aufsätze." Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 10 (2010). Cited 1 May 2023. Online: http://www.arts.ualberta.ca/JHS/reviews/reviews_new/review452.htm. [ Links ]

Wright, David P. Inventing God's Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Covenant Code Appendix (Exodus 23:20-33), Neo-Assyrian Sources, and Implications for Pentateuchal Study." Pages 47-86 in The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Edited by Jan C. Gertz, Bernard M. Levinson, D. Dalit Rom-Shiloni and Konrad Schmid. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

_______________________. "The Common Scribal School Culture of Deuteronomy and the Covenant Code." Zeitschrift für Altorientalische und Biblische Rechtsgeschichte/Journal for Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical Law 25/1 (2019): 181 -186. [ Links ]

Zahn, Molly M. "Scribal Revision and the Composition of the Pentateuch: Methodological Issues." Pages 491-500 in The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Edited by Jan C. Gertz, Bernard M. Levinson, D. Dalit Rom-Shiloni and Konrad Schmid. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

Submitted: 06/07/2022

Peer-reviewed: 01/11/2022

Accepted: 20/12/2022