Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.36 no.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2023/v36n1a14

ARTICLES

Sacred Texts Produced under the Shadows of Empires: Double Consciousness and Decolonial Options in Reading the Hebrew Bible

Hulisani Ramantswana

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The Hebrew Bible is a complex of sacred texts shaped and reshaped by Israelites, Judaeans and later Jews under the shadows of empires, which threatened, oppressed, dominated and at times provided protection to them. At the same time, they more often than not had to resist, shun, and yet forcefully submit to the empire and on other occasions, they supported, colluded with and mimicked the empire. This essay explores decolonial options for reading the Hebrew Bible, considering two determinations: the Hebrew Bible is a product of the colonised and was influenced and sponsored by the empire.

Keywords: Decolonial Options, Reading, Empires, Imperial Dynamics, Africa, African Knowledge Systems

A INTRODUCTION

I dedicate this article to Professor Gert (Gerrie) Snyman, who has been a friend, colleague and mentor. Before I took over the reins from Professor Hans van Deventer as associate editor of Old Testament Essays (OTE), Professor Snyman had already taken me under his wings and mentored me in the sphere of scholarly publication. In 2018, I had big shoes to fill when I took over from him as General Editor of OTE. Prof Snyman also encouraged me to attend the decolonial summer schools, which sparked the mental shift to decoloniality. In his scholarship, Snyman has not shied away from confronting the realities and effects of colonialism, apartheid and racism. For Snyman, the concept of vulnerability provided a decolonial hermeneutical lens to consider the colonial violation of the other, which requires the perpetrators to be vulnerable.

I begin by reflecting on two individuals who, although their paths never crossed, were both drawn to Ghana for a brief time: W.E.B. du Bois and Frantz Fanon. Du Bois' concept of "double consciousness" highlights the struggle for social identity, which he describes as "a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, the sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity."2 Similarly, in The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon speaks of "two determinations" of the colonised:

'Speaking as an Algerian and a Frenchman'. . . Stumbling over the need to assume two nationalities, two determinations, the intellectual who is Arab and French . . . if he wants to be sincere with himself, chooses to the negation of one of these two determinations. Usually, unwilling or unable to choose, these intellectuals collect all the historical determinations which have conditioned them and place themselves in a thoroughly 'universal perspective.'3

In Black Skins, White Mask, Fanon mentions "two frames of reference":

Overnight the Negro has been given two frames of reference within which he has had to place himself. His metaphysics, or, less pretentiously, his customs and the sources on which they were based, were wiped out because they were in conflict with a civilization that he did not know and that imposed itself on him.4

The double consciousness not only applied to those African beings who had to embrace new identities in the new lands of their enslavement or in the diaspora; it was also a process happening here in the motherland as African souls became westernised. The so-called "postcolonial" Africa is still entangled in the colonial structures which continue to shape people's daily lives.5

The double consciousness or the two-ness also permeates our study of sacred texts in the African context. For many indigenous people of Africa, our experience with the Hebrew Bible is that of "two-ness"-a sacred text and a colonising text-it is the two unreconciled experiences which speak to our problematic relationship to the Hebrew Bible. In this article, I will consider this "two-ness" of the Hebrew Bible as a sacred text-a text that originated within ancient Israel's history. The two-ness of the sacred text requires that we disassociate it from the modern European colonial project and the structures of coloniality. This disassociation is not an attempt to redeem or cleanse the sacred text to make it more acceptable in our African context(s), but the sacred text itself provides a lens for viewing it without necessarily equating it with the EuroWestern colonial attitude towards Africa and her people. It is the choice to look at the sacred text as an object birthed by a particular people (Israelites-Judaeans-Jews) under certain circumstances, which we may or may not relate to. This disassociation of the text from the modern colonial project allows the subaltern to speak about the sacred text without necessarily speaking about the West or through the West.6 On the other hand, from our experience of the suffering inflicted upon African peoples using the Bible, we also must speak to and through this sacred text, a book of faith, to our suffering and to the Euro-Western colonial project and its continuing structures, which brought suffering using the same text.

B THE HEBREW BIBLE AS A PRODUCT OF A COMMUNITY THAT DEFINED ITS ORIGIN AS ANTI-IMPERIAL AND PRO-IMPERIAL

The two-ness of the Hebrew Bible as a sacred text, as I contend in this article, is premised on two determinations. First, the Hebrew Bible is a product of a community that defined its origins as an anti-imperial and its rebirth as a pro-imperial community and second, the Hebrew Bible as a product influenced and sponsored by the empire. Therefore, in this section, I focus on the first determination of the Hebrew Bible.

Early Israel emerged in Canaan during the period 1250-1000 BCE. The earliest mention of "Israel" is found in the Egyptian Merneptah Stele dating from 1207/8 BCE, which describes Merneptah's victories:

Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe

Ashkelon has been overcome,

Gezer has been captured,

Yano'am was made non-existent,

Israel is laid waste (and) his seed is not.7

The Stele provides a glimpse of the Egyptian Empire's dealings with the neighbouring Hurru-Land or Canaan. The entities mentioned in the Stele are Canaan, Ashkelon, Gezer, Yano'am and Israel. These entities are presented as conquered entities during the Campaign. There are various opinions on how Israel of Merneptah's Stele should be defined-lezreel or Yezreal (a group unrelated to the Israel of the Hebrew Bible proto-Israel), proto-Israel, a socioeconomic entity within Egypt, or a people and territory in Canaan.8 In this study, I concur with Hasel's view that Israel, as mentioned in the Merneptah Stele, is best viewed as a people within Canaan who existed not as a city-state but as an agriculturally-based/sedentary socio-ethnic entity.9

Egypt controlled the land of Canaan from the time of Thutmose III (14791425 BCE) to the time of Ramesses III (1186 -1154 BCE) or Ramesses IV (1154-1148 BCE).10 The control of Canaan served the following purposes. Firstly, the region of Canaan provided the Egyptian Empire with a buffer against attacks from rivals in Mesopotamia (Mitanni) and Anatolia (Hittites). Secondly, the domination of the region implied the city-states in the region would pay tributes and thirdly, Egypt had control over major trade routes linking her with Arabia, the Levant and Mesopotamia.11 However, notable for us is that Egypt, as part of its imperial policy, acquired enslaved people through military conquests,12 tributes13 and as part of business transactions.

While the earliest mention of Israel sets Israel as people outside of the empire, in Israel's tradition of origins, Israel had links with Egypt. The exodus tradition is among Israel's earliest traditions that link the emergence of early Israel with the Egyptian Empire. Williams notes, "Israel was always conscious of her ties with Egypt and the traditions of her sojourn there were indelibly impressed on her religious literature."14 Therefore, it is not a surprise that the exodus motif appears frequently in the Hebrew Bible.15 Several scholars highlight the importance of the exodus for ancient Israel-confessional statement,16 formative or birth event,17 determinative event,18 paradigmatic,19political myth20 and so on. Scholars also point to various Egyptian elements in Israel's linguistic, cultural, social and religious framework.21

1 Exodus Motif: Birth of Israel as Anti-Imperial

The exodus from Egypt, on the one hand, and exile and return to Yehud from Babylon, on the other, are defining moments within the purview of the Hebrew Bible.22 As I will highlight later, the latter is viewed and interpreted in light of the former.

From an archaeological perspective, there is a lack of remains to support Israel's sojourn in Egypt, the exodus and conquest. Whilst the historicity of the exodus from Egypt and the conquest of the land remain a contested matter, Hendel argues that:

[M]any of the local settlers in early Israel had memories, direct or indirect, of Egyptian slavery. These memories were linked to no single pharaoh, but to pharaoh as such, the array of pharaohs whose military campaigns, vassal tributes, mass deportations, and support of the slave trade forced many Canaanites into Egyptian slavery. Not all of these slaves need to have escaped with Moses-or to have escaped at all-to create the bitter memory of Egyptian slavery among the early population of Israel.23

Thus, the anti-imperial sentiments would have been widespread within Canaan and provided the necessary ingredients for collective identity formation. Gottwald also argues that:

Early Israel arose as an antihierarchic movement, socially in its formation by tribes and politically in its opposition to the payment of tribute, military draft, and state corvée. This means that early Israel not only renounced the right of outside states and empires to rule over it but also refused to set up a state structure of its own.24

In Yoder's terms, the exodus symbolises a "countercommunity," that is, an independent community withdrawn from the normal modus operandi of "a seizure of power in the existing society."25 However, the exodus narrative projects the empire as reacting violently as it attempts to recapture the countercommunity.26 Gottwald notes that the anti-imperial movement did not immediately lead to the formation of Israel's monarch(s). Early Israel was a segmented society comprised of various tribal groups with no centralised government.27 However, such a mode of organisation, while it may have served to give the tribal groups a sense of freedom and independence, could not keep the empires (Egyptian, Hittites and Assyrian) and the small political players (e.g., the Sea People, who entered Palestine and sought to expand their territory, Moabites, Edomites, Ammonites) at bay. The threat of imperial forces and the power struggles pressured the tribal groups into unifying for security purposes. However, this, in turn, served the conquering imperial forces as they also relied on local rulers to administrate taxes and tributes.

From a literary perspective, the exodus motif is among the key literary features which hold together Israel's Primary Narrative (Genesis-2 Kings) as a cultural memory.28 Similarly, Bruggemann opines that Israel's literati, in narrating Israel's history, "retold all of its experience through the powerful, definitional lens of the Exodus memory."29 Furthermore, the exodus motif not only points back to a formative moment but also highlights the continuing struggle for liberation in subsequent generations.

Without being exhaustive, during the monarchic period, the prophets used the exodus motif to criticise internal oppression and disobedience to YHWH in Israel-Judah. For eighth-century prophets such as Hosea, who operated in the Northern Kingdom of Israel and Amos, who operated in the Southern Kingdom, the exodus features prominently.30 Hosea announced that Israel, due to her unfaithfulness to YHWH, "will return to Egypt" (Hos 8:13; 9:13; 11:5; cf. 12:7). In Hos 9:13 and 11:5, 12, Egypt is paired with Assyria, the new imperial power in the eighth century. The threat at the time of the prophet Hosea was not so much the Egyptian Empire but the Assyrian Empire. The reversal in Hosea also occurred when the prophet used the concept of a God who "brought you out of Egypt" (Hos 12:8-14; 13:1-16). Amos reminded his audience of their deliverance from Egypt (2:10), which should have served to deter them from oppressive tendencies, yet they oppressed each other internally (2:6-9; 3:9). For Amos, the consequence for such action would be a reversal of the exodus-(2:13-16) and suffering from the plagues that Egypt experienced (4:10). However, the exodus was not unique to Israel-it was what YHWH did for other nations as well (Amos 9:7).31 Thus, the exodus motif did not function solely as a memory of anti-imperial origins; it also serves as a metaphor for the ongoing struggle for freedom from internal oppression. As Snyman notes, the same motif could also be "turned against Israel while it is in actual fact one of the major redemptive acts of YHWH in the history of Israel/Judah."32

2 Exodus Motif: Rebirth of Israel as a Pro-Empire Community

The exodus motif also features prominently in some literature that emerged during the exilic and post-exilic periods as a metaphor for Israel's rebirth. However, in this context, it finds new twists and turns as it does not point to a "countercommunity," which sought its existence outside of the powers that be or resistance to imperial tendencies. Rather, Israel finds itself as a stateless nation having to survive within the ambit of the empires with the memories of the land and state(s). In Davidson's view,

Exodus and exile are more than historical events and theological constructs. These serve as a lens for shaping and reading biblical traditions. Rather than being opposite poles, they interact continuously in a continuum and plot trajectory for reading forms of power in texts . . . Exodus offers alternative communities to imperial power while exile presents opportunities to subvert power and to (re)locate power to alternative sites.33

While I agree with Davidson, it is also important to highlight the distinctive function of the exodus motif as linked with exile-the "exodus" not as a counter to imperial power but rather as a pro-imperial. The exodus features prominently in the so-called Deutero-Isaiah (Isa 40-55), that is, the Isaiah of Exile: The highway in the wilderness (Isa 40:3-5), the transformation of the wilderness (Isa 41:17-20), YHWH leads his people (Isa 42:14-16), passing through the water and fire (Isa 43:14-21), a way in the wilderness (Isa 43:14-21), the exodus from Babylon (Isa 48:20-21), new victory over the sea (51:9-10), the new exodus (Isa 52:11-12) and Israel shall go out in joy and peace (Isa 55:12-14). In the context of the Babylonian exile, the new exodus is not a renouncement of the empire altogether but a renouncement of one empire in favour of another. In Deutero-Isaiah, Cyrus, a Persian king, becomes YHWH's shepherd (Isa 44:28) and the messiah (Isa 45:1), epithets of a Davidic king. The Persian conquest of the Babylonian Empire allowed for a return of the golah (the exiles) to their homeland, the rebuilding of the temple and continuing with life in Yehud, a colony of the Persian Empire. In Isaiah, Cyrus is the messiah based on his political agenda that made it possible for the Jews to return to their homeland, while the servant in Isa 49:3 is a royal figure, who is supposed to take up the spiritual dimension of the exodus as he leads the returnees to their homeland.34Thus, the role of Cyrus as a liberator did not mute the hopes for a Jewish messiah. The hopes for a Jewish messiah were partly realised in Zerubbabel and Hattush (a returnee with Ezra, see Ezra 8:1-2). However, the two failed to restore the Davidic dynasty.35 While the returnees probably had ambitions for the restoration of the Davidic dynasty, that did not amount to the rejection of the Persian Empire. In any case, the restoration of the Davidic dynasty would have required the authorisation of the Persian Empire.

In 2 Chron 36:22-23 and Ezra 1:1-2, the edict of Cyrus in 538 BCE effectively brought the exile to an end:

Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of the Lord by the mouth of Jeremiah might be accomplished, the Lord stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom and also put it in writing: "Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, 'The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him. Let him go up'" (RSV).

For the Chronicler, the end of the exile meant bringing an end to the land's Sabbath (2 Chron 36:21).36 As some scholars observe, the Chronicler does not emphasise the exodus, Sinai tradition and Northern traditions in constructing Israel's grand narrative.37 However, essential for us to note is the positive portrayal of Cyrus. First, Cyrus fulfils earlier prophecy; second, Cyrus viewed himself as an instrument of YHWH; third, the edict is itself pronounced in the name of YHWH; fourth, Cyrus is divinely sanctioned to rebuild the house of YHWH; and fifth, the return to the Yehud is not by force. The Chronicler positively appropriates the role of the Persian Empire. Undoubtedly, the book of Chronicles was composed later than the Cyrus edict, when the temple was likely rebuilt but with no restoration of the Davidic dynasty. As Japhet argues, in constructing the grand narrative, "the Chronicler places himself and his generation in the time of Cyrus. Restoration lies ahead and is about to begin."38Jonker affirms that the Chronicler wanted his audience to view the period under the Persian Empire positively as a new era, which fulfilled Jeremiah's prophecies and restored Israel as a New Israel.39

For Berquist, based on the exodus motif, the Hebrew Bible defined the identity of the Judaeans as those who are against Egypt and ought to avoid Egypt's alliance.40 However, this idea of an anti-Egypt Judaean community during the Persian period does not do justice to the complexities of the exodus motif, considering its context in the Pentateuch or Hexateuch. The exodus motif in the context of the Pentateuch looks forward to a conquest, which was supposed to be a complete destruction of the inhabitants of the land, who are listed by name-Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites (Exod 3:8 NIV). However, the Judaean community under the Persian Empire was not to conquer but to return to the land to reclaim and rebuild it.

If the exodus motif is considered formative, one wonders what the conquest was for the same Judaean community, which embraced such an imperial ideology. In imperial terms, the suffering of a people in Egypt under a Pharoah pales compared to the horrendous act of conquest of the Promised Land. Therefore, one wonders what role such an ideology played in identity formation for the Judaean community during the Persian period. In Liverani's view, the golah community regarded Joshua as a role model for their leaders, whom they expected to clear the land for their resettlement. Therefore, in this view, the golah community considered itself a holy seed that deserved to inherit the land. In my view, the Jewish literati under the Persian Empire set Israel's glory in the distant past. However, what that glorious past achieved was the allocation of land, which the golah community wanted to reclaim. Therefore, during the Persian period, the conquest motif legitimised the golah community's claim to the land for those who returned to the land.

So far, we have observed the two-ness of Israel's self-definition in relation to the empires. The sacred text paints a picture of an Israel whose identity was formed in the bellies of empires. The exodus motif therefore functions as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, Israel is an anti-imperial community that sought a life outside of the jaws of the empire and on the other hand, Israel is a pro-empire community that sought life inside the empire-the restoration of a nation without the restoration of the Davidic dynasty. In Fanonian terms, Israel "assumed two determinations" and therefore spoke as an anti-imperial and pro-imperial community based on the experiences which conditioned her. However, Israel's experiences with the empires not only shaped the identity of the community but, as I will argue below, also shaped Israel's sacred text.

C HEBREW BIBLE AS SACRED TEXTS PRODUCED WITH IMPERIAL INFLUENCE AND SPONSORSHIP

The Hebrew Bible is a collection of ancient Israel's sacred texts whose earliest traditions go back to the twelfth century BCE and the latest texts to the second century BCE.41 However, it should be noted that the Hebrew Bible is not the sole collection of sacred texts that ancient Israel produced during the period. Other related sacred texts include the Septuagint (LXX, Greek translation), the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Dead Sea Scrolls and many other texts such as the Apocryphal books and the Pseudepigrapha.42

Ancient Israel, under whose purview the sacred texts noted above originated, did not mushroom into an empire with a wide and broader reach. This does not imply that Israel was free from imperial ideology or imperial tendencies, or imperial ambitions.43 From the twelfth century to the first century BCE and even into the first century AD and beyond, ancient Israel had to navigate and survive under the shadows of successive empires-Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek/Hellenistic and the Roman Empire. This does not imply that ancient Israel did not have imperial ambitions or that the producers of Israel's sacred texts were free from imperial ideological constructs.44 As already noted, the conquest of the land is an imperial ideological construct, which is presented as divinely sanctioned. Another example is the portrayal of Solomon's rule in imperial terms in 1 Kgs 4:20-21, which states that:

Judah and Israel were as numerous as the sand by the sea; they ate and drank and were happy. Solomon was sovereign over all the kingdoms from the Euphrates to the land of the Philistines, even to the border of Egypt; they brought tribute and served Solomon all the days of his life (1 Kgs 4:20-21, NRS; cf. 2 Chron 9:26).

The casting of Israel's past by means of imperial ideology may be viewed as a subtle anti-colonial polemic intended to undermine the conquering empire by setting the ideal empire in Israel's past.45 However, the imperial ideology, even when set within Israel's past, is not entirely successful. The conquest was not entirely successful in the purview of the book of Judges and the glorious Solomonic Empire collapsed.

Below, we address two issues-the influence of the empires on Israel's sacred texts and the sponsorship or authorisation of Israel's sacred texts by the empires. As Crowell notes, "[m]ost biblical literature was composed in the context of imperial rule; yet, the effects of that situation are rarely explored by biblical studies."46 In dealing with the effects of imperialism on the production of biblical literature, we do not have to overlook the empires that used different strategies to dominate.47

1 Imperial Influence

To appreciate the nature of influence, it is essential to understand how ancient empires operated. Ancient empires were geared towards territorial expansion to gain access to the resources that would support and service the centre. Therefore, the colonised or subdued territories would pay tributes to the empire, which were crucial for the existence and further expansion of the empire.48 The conquest of territories was not mainly geared towards total destruction but submission- territorial expansion also opened trade to acquire more wealth. Thus, for the empire, once a territory was subdued, the territory's stability and continued operation required local rulers.49 In addition, the expansion was for ideological reasons-fulfilment of a divine prerogative as the king carried the mandate on behalf of the gods.50

The weakening of one empire opened room for another empire to emerge. Therefore, the idea of small states operating independently without an empire closing in was highly unlikely, as operating under the shadow of an empire guaranteed some level of security and stability. Tribal groups operating loosely was an unsecured form of operation, which widely exposed them to raiders and other exploitative forces.51 Therefore, small states like Judah and Israel had to choose their alliances wisely to gain some sense of security and comfort, which came at the cost of paying tributes. This often burdened the peasants, who had to work even harder to service the taxes of their central administration and those of the empire. When empires clashed, it opened a door for small states to trade one empire for another, that is, choosing a better devil.

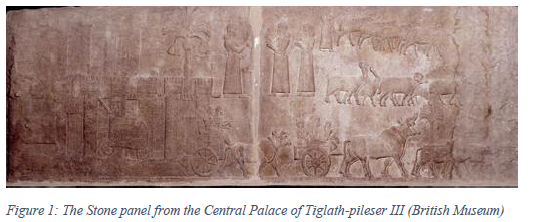

The empires made room, particularly at the centre, for people from different territories to contribute to strengthening the empire through their labour. Therefore, some were drawn to the centre, which provided food and economic security, particularly in times of hardship due to famines. However, empires also engaged in deportations of the conquered in cases where the vassal states engaged in resistance or rebellion. Frequently, the empires quelled resistance with a heavy hand. In some instances, it resulted in the deportation of people from one area to another and in other instances, deportation was a strategy of the empire to meet its own needs. For the Assyrian Empire, the motif used is that of the empire as a gardener who uproots a tree from one place and establishes it in another (cf. 2 Kgs 18:31-32; see Figure 1 below). First, deportation was a way of sourcing human resources required by the empire at the centre or elsewhere; second, meeting the strategic needs of the empire; and third, dealing with dissent. However, as Valk notes, to the Assyrian Empire, deportation "was first and foremost intended to curb resistance to Assyrian hegemony."52

The ancient empires, Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian and Persia, in their territorial expansion and to maintain their foothold on their subject, also sought to influence them ideologically. To achieve such, empires, through the kings, would impose laws on the vassal state to keep it under check and, in other instances, introduce their own language and customs.53 The enforcement of these things depended on the local elites, who were co-opted by the empire to rule and function as administrators. Fitzpatrick-Mckinley argues that:

Given the importance of elite networks to the ancient economy, it is not surprising that when imperial powers took control of national monarchies, chieftaincies and tribes, they saw the elites of these societies as resources which could be manipulated on behalf of the empire.54

The manipulation of the conquered also happened through education, which required the production of literate elites. As Philipps argues,

In its classic formulation, the moment of imperialism is also the moment of education. Imperialism-a system of economic, political, and cultural force that disavows borders in order to extract desirable resources and exploit an alien people-has never strayed from a field of pedagogical imperatives, or what might be called an ideology of instruction.55

In the ancient Near East context, elites played an important role in the production of literary texts through the services of scribes. In that context, scribes were, by and large, royal employees and not temple employees.56 In addition, the empires also equipped those in the subdued territories with communication skills, which would have included scribal activity and imperial administration.57In Schniedewind's view, it was only in the seventh century BC that literacy started to spread in ancient Israel. As Van der Toorn notes, the making of the Hebrew Bible should be attributed to the temple scribes of the Second Temple, active between 500 and 200 BCE.58 During this period, Yehud remained under the shadow of successive empires-Persia and Greek. Pace van der Toorn, I concur with Schniedewind's view that we must rely on more than just the temple scribal activity to explain the authority of sacred texts in ancient Yehud. Therefore, the role of the empire must be addressed.59

As much as the empires produced elites from the underside of the empire to serve the imperial dictates, the same elites could also work against the empire. The elites from the underside of the empire had to balance serving the interests of the empire and those of the local people with whom they shared the same plight. Therefore, the same elites could also work against the empire in the interest of those on the underside of the empire in multiple ways-through sabotage, undermining the imperial dictates, revolt and production of counter-narratives, among others. Therefore, it is not surprising that the subdued territories, from time to time, risked rebellion against the empire despite the possible backlash if the rebellion failed. For example, under the Babylonian Empire, the Kingdom of Judah started as a vassal of the empire. However, the continuing revolts, first the revolt of Jehoiakim and continued by his son Jeconiah, resulted in the empire appointing Zedekiah, an uncle to Jeconiah, as king. When Zedekiah led another revolt, the empire discontinued the kingship and appointed Gedaliah as a governor, thereby, relegating Judah from the status of a vassal kingdom to just a province of the empire.60 The Persian Empire also moved away from using Judaean governors when Artaxerxes III appointed a Persian governor named Bagohi. In Albertz's view, this move prompted Nehemiah's disassociation policy, destabilising the area.61

Therefore, the influence of empire on the production of texts could go in varying directions. Those on the underside of the empire could produce texts that relate their experiences under the empire, critique, appease, mimic, support and make allegiance with, denigrate, mock and even counter the empire. While the empires gained substantial power over the subdued and left indelible marks on them, such power was not absolute. Therefore, the Hebrew Bible cannot be viewed as a single-voiced text but a plurivoiced text.

2 Imperial Sponsorship

In the past two decades, one of the theories that emerged in the study of the Hebrew Bible is that of "imperial sponsorship" or "imperial authorisation" under the Persian Empire. This theory, in a sense, talks to another level of the two-ness of the sacred texts-the texts which gained their authority from, on the one hand, the temple, which endowed them with religious authority and on the other, from the emperor, to endow them with royal authority. Carr notes that "[j]ust as Persians are reported to have engaged local leaders as their proxies in their empire, the Bible testifies in multiple ways to its status a product of Persian-sponsored returnees from exile."62 What emerged in such a process:

[w]as not a canon to replace a history or to displace an established religion by establishing a new one. The canon gave expression to the understanding already present while at the same time modifying those understanding already present while at the same time modifying those understandings. The new literary context could accomplish much of this modification. The Persian-appointed governors and scribes produced the document and pronounced it from the midst of the imperially-funded temple. That act in itself blurred many of the distinctions between old and new, between religion and politics.63

An essential text in the Persian imperial authorisation debate is Ezra 7:1216, particularly the final statement in the letter of the royal appointment of Ezra: "All who will not obey the law of your God and the law of the king, let judgment be strictly executed on them, whether for death or for banishment or for confiscation of their goods or for imprisonment" (Ezra 7:26 NRS, emphasis added). If the authority of sacred texts is not based solely on temple activity but also on royal activity, it is conceivable that those in Yehud viewed Darius as their legitimate king and, therefore, were willing to accept as authoritative the promulgated laws of the king. As already noted, the restoration of Israel did not amount to the restoration of the kingdom of Judah-a Davidic dynasty.

Much of the Hebrew Bible, as Carr notes, is pro-Persian and hardly critiques the Persian Empire. The positive portrayal of the Persian Empire suggests the following two things: "(1) that the Bible was significantly shaped by the scribes with pro-Persian sympathies; and following that, (2) that the Persian period itself was crucial in the formation of the Hebrew Bible."64 The exception is texts such as Daniel's visions or Neh 9, which emerged during the Hellenistic period. While I agree with the view that much of the Hebrew Bible is pro-Persian, that does not imply that we cannot and should not expect dissenting voices or attempts to subvert the empire in the Hebrew Bible.65

The choice to operate within the confines of the empire did not necessarily imply blanket endorsement of the empire. Operating under imperial dictates was a choice between life and death. However, seeking and working with the empire's approval did not necessarily imply that the empire was accepted and loved.

D DECOLONIAL OPTIONS IN READING THE HEBREW BIBLE

Considering the two-ness of the Hebrew Bible, the decolonial framework requires that the Hebrew Bible be viewed as a sacred text of the colonised that is infused with imperial ideology. Therefore, I propose the following decolonial options:

Reading the Hebrew Bible requires that it be read as a compilation of sacred texts of the colonised. While all empires have an ending, the cessation of one empire did not necessarily imply the end of imperialism, as the ending of one empire was due to the rise of another dominant empire. In dealing with sacred texts, there is no postcolonial situation-it is imperialism-colonialism through and through. Israel was under the shadow of empires through and through; therefore, her texts are texts of the colonised. The so-called "post-exilic" rebuilding of Yehud under Ezra-Nehemiah, which the likes of Mugambi,66 Villa-Vicencio67 and others hailed as a model of Reconstruction in Africa, unfortunately, projects a rebuilding under imperial sponsorship and grip. The return of the golah community to Yehud did not imply political and economic freedom-Yehud remained a province of the empire.

Reading with a preferential option: Decolonial reading of the Hebrew Bible is not neutral-it proceeds in the same vein with Black Theology of Liberation-by having a preferential option, that is, for the poor, the oppressed, the suffering, the exploited, abused, enslaved, the landless, the marginalised, the colonised. Decolonial reading does not side with the oppressor, whether oppressors in the past or in the present.

Reading the Hebrew Bible as plurivoiced text-voices of support and resistance to the empire. Voices of support for the empire and voices of resistance can be discerned within the text. In as much as the sacred text of the Hebrew Bible may be dubbed a product of the elites, recognising the Hebrew Bible as a sacred text of the colonised requires that the Marxist gist within Black Theology of Liberation be revisited.

In the context of ancient imperial dynamics, an elite in the subdued lands may be deemed an oppressor or exploiter at the local or regional level and yet, on the imperial level, be a voice of resistance. Therefore, in reading the biblical text, one must oscillate between struggles with the empire and struggles within the colonised.68

Empires exploited the relationships between the subdued and colonised, producing a binary of slaves-the house slaves and field slaves. I am following Malcolm X's parable of "a house negro and a field negro" from his speech "Message to the Grassroots," which was delivered on November 10, 1963 in Detroit.69 As the parable goes:

There were two kinds of slaves, the house negro and the field Negro. The house Negroes-they lived in the house with the master, they dressed and ate good because they ate his food-what he left. They lived in the attic or the basement, but still they lived near the master; and they loved the master more than the master loved himself. They would give their life to save the master's house-quicker than the master would. If the master said, 'We got a good house here,' the house negro would say, 'Yeah, we got a good house here.' Whenever the master said 'we,' he said 'we.' That's how you can tell a house Negro.

If the master's house caught on fire, the Negro would fight harder to put the blaze out than the master would. If the master got sick, the house Negro would say, 'What's the matter, boss, we sick?' We sick! He identified himself with his master, more than his master identified with himself. And if you came to the house Negro and said, 'Let's run away, let's escape, let's separate,' the house Negro would look at you and say, 'Man, you crazy. What do you mean, separate? Where is there a better house than this? Where can I wear better clothes than this? Where can I eat better food than this?' That is the house Negro. . . .

On the same plantation, there was the field Negro. The field Negroes-those were the masses. There were always more Negroes in the field than there were in the house. The Negro in the field caught the hell. He ate leftovers. In the house, they ate high up on the hog. The Negro in the field didn't get anything but what was left of the insides of the hog. They call it "chitt'ling" nowadays. In those days, they called them what they were - guts. That's what you were - gut eaters. And some of you are still gut-eaters.

The field Negro was beaten from morning to night; he lived in a shack, in a hut; he wore old, castoff clothes. He hated his master. I say he hated his master. He was intelligent. That house Negro loved his master, but that field Negro-remember, they were in the majority, and they hated the master. When the house caught fire, he didn' t cry try to put it out; that field Negro prayed for wind, for a breeze. When the master got sick, the field Negro prayed that he'd die. If someone came from the field and said, "Let's us separate, let's run," he didn't say, 'Where we going?" He'd say "Any place is better than here. "

The parable highlights the levels of oppression and the response to oppression. Reading the Hebrew Bible through the lens of decoloniality requires us to identify with the struggles of both the house slave and the field slave-both are slaves. However, we also need to note further that these categories were not necessarily permanent-as one could shift from being a field slave (field negro) into a house slave (house negro). The Moses story may be read as an example of the shifts from the margins to the centre and back again to the margins. It may be that this story also captures the plight of the elites in ancient Israel, who had to oscillate between the margins and the centre. However, in the Moses story, the ideal elite is one who lets himself be enveloped by the struggles of those in the margins and takes up their struggles.70

If the notion of a Persian-supported Hebrew Bible is anything to go by, the implications are the following among others. First, the empire co-opted some from the subjugated to serve the agenda of the empire-these were the educated elites, who also served in the production of Israel's sacred texts. Therefore, in the Hebrew Bible, the reader may discern the voice of the empire and imperial ideology embedded therein through imperial scribes who would have censored the production of sacred texts, the writing, editing and final redactions before archiving. The reader needs to exercise caution and suspicion as the imperial agenda is also embedded in the sacred texts. As Griffiths warns regarding reading subaltern voices:

Even when the subaltern appears to 'speak' there is a real concern as to whether what we are listening to is really a subaltern voice, or whether the subaltern is beings spoken by the subject position they occupy within the larger discursive economy. . . In inscribing such acts of resistance, the deep fear for the liberal critic is contained in the worry that in the representation of such moments, what is inscribed is not the subaltern's voice but the voice of one's own other.71

Second, the elites co-opted by the subaltern could also subtly subvert the empire through the same texts. Serving the empire did not necessarily equate to loving the empire and hating one's own people. Just like Moses, an elite or a scribe serving at the behest of the empire may still identify with the struggles of those in the margins. As Bush notes, where there is imperialism and colonisation, there is always protest and resistance against the oppressor and the modes of oppression.72 The Persian imperial sponsorship of the Hebrew Bible, while it would have come with attempts to silence and control certain texts and certain voices within the texts, it does not necessarily imply success. Furthermore, texts could be revived through editorial and redaction activity. McLeod affirms:

Many literary texts can be reread to discover the hitherto hidden history of resistance to colonialism that they also articulate, often inadvertently... In rereading a classic text, readers can put that text to work, rather than placing it on a pedestal or tossing it to one side as a consequence of whether or not it is deemed free from ideological taint.73

Resistance to empires took different forms, whether individual or collective, violent or peaceful, covert or overt; the goal was to destabilise and frustrate the empire. As noted earlier, empires often responded aggressively to resistance; therefore, the oppressed would also find subtle means to subvert the empire for survival's sake. Thus:

Differently organized groups develop distinct anti-colonial responses . . . resistance and survival are thus the weapons of the colonized and the settler colonized; it is resistance and survival that make certain that colonialism and settler colonialism are never ultimately triumphant."74

Third, the marginalised elites could produce counter texts in response to or against the empire. When empires took over other lands, they also disrupted societies, which implies that some of the elites who were at the centre would have been marginalised. A house negro could become a field negro, so to speak. In addition, the empires would have pushed to the margins those elites who did not toe the line-the Moses type. This would have opened the door for counter-texts to be produced from the margins.

Fourth, the sacred texts embed the voices of resistance emerging from the masses who bore the brunt of the imperial forces. The elites at the centre could also incorporate or engage voices from the margins. Therefore, in reading the sacred texts, the voices from the margins can also be heard in the same texts.

Fifth, the sacred texts embed the voices from elsewhere. Sacred texts were not solely produced in Yehud. The voices from elsewhere can also be heard in the sacred texts. Therefore, in reading the sacred texts, it is also worthwhile to probe how the texts from elsewhere engaged imperial issues, e.g., the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Septuagint and other texts which originated during the Second Temple period, which did not necessarily emerge from Yehud.

Reading from a position of colonial difference, a reading with African eyes. Reading the Hebrew Bible from a position of colonial difference requires us to engage in what Mignolo and Walsh regard as the insurgency of knowledge and (re)existence. This, they describe as "offensive action and proactive protagonism of construction, creation, intervention, and affirmation that purport to intervene in and transgress, not just the social, cultural, and political terrains but also, and most importantly, the intellectual arena."75 Such insurgency in our African context requires us to interpret the text from a position of colonial difference. This implies a deliberative move to read the Bible through African eyes and our African knowledge systems as resources for interpreting the Hebrew Bible.

Reading the Hebrew Bible from a position of colonial difference is the refusal to play the game in terms of Euro-Western practices and limitations. It requires the reader to make a shift in the geography of reason and tap into his/her knowledge system. It allows us as Africans to tap into our African heritage as resources for critical reflection, analysis and engagement with the world. In so doing, our African knowledge systems, culture, experiences, religious traditions and experiences shape our reading of biblical texts. Thus, decolonial reading is the refusal to see our knowledge system as wastelands.

Thus, if the ancient sacred text, the Hebrew Bible, a product of the colonised community, which cherished its heritage and preserved it for future generations, continues to speak into our contemporary contexts, we are damned if we regard our rich African heritage as outdated and irrelevant and not worthy of retrieval from the abyss of colonial destruction.

Reading for decolonial justice: Decolonial justice is the demand for a world free of imperialisation and colonisation, conquest and violence, oppression and suffering, marginalisation and exclusion, superiorisation and inferiorisation. As I have argued elsewhere, "Decolonial justice is not the trading of one oppressor with another, where the previously oppressed become the new oppressors; rather, it is the demand of a just society in which colonial structures of domination and oppression of the other are undone."76 What decolonial justice demands is justice born from the underside of the empire, that is, justice born out of the struggle for life.

It cannot be that the perpetrators of imperialism and colonialism would turn and masquerade as champions of justice. Justice that is born out of the belly of the imperialists and colonialists is intertwined with self-justification and the unwillingness to recompense unless forced. Instead, it is justice that is born from the underside of power that has transformative potential. As Maldonado-Torres argues, "[t]he damnés have the potential of transforming the modern/colonial into a transmodern world: that is, a world where war does not become the norm or the rule, but the exception."77

Decolonial justice is the refusal to normalise violence and naturalise war but the demand for a free and just world. Therefore, the ideologies that normalise and naturalise violence must be critically engaged when dealing with the sacred text. In the words of the prophet Amos, we cannot, "But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream!" (Amos 5:24 NIV).

Vulnerability of the colonisers' offspring: At the beginning of this essay, I referred to Snyman's hermeneutics of vulnerability, which I highlight here as a decolonial option.78 Snyman's hermeneutic of vulnerability bears in its purview the fact that those historically associated with colonialism must come to terms with the effects of colonialism on the other to whom injustice was done and the self as a beneficiary of the unjust system.79 The hermeneutic of vulnerability, as Snyman argues, is not about a set of rules of interpretation. Instead, it "takes the vulnerability of the (colonized) other seriously in terms of the marks left by the interpretation (and actions) of the (colonising) interpreter in realising the vulnerability of the (colonizing) self."80 The hermeneutic of vulnerability requires those who were the colonisers and continue to live as beneficiaries of the unjust system to realise the injustices and effects of such an unjust system. For Synman, it is impossible to think beyond colonialism, apartheid, racism and the ills ensuing thereof as though these things were undone.81 In Snyman's view, for those implicated in colonialism and apartheid to be liberated, there must be a willingness to face the discomfort and move into the space of a perpetrator.

Assuming the space of the perpetrator requires the willingness to take responsibility and ownership not just at the individual level but also at the communal level. This requires one to "think through the ambiguity and ambivalence of the position of perpetratorhood and trace its paradoxical nature in one's own praxis."82 For the perpetrator to achieve liberation, it requires the victim, as the perpetrator cannot free himself or herself-the perpetrator requires the victim to be free. This "cannot be solved through a substitutionary reconciliation of the traditional Christian doctrine of redemption and reconciliation in Christ" but through "the confrontation with the consequences of the cruelty within the life of a victim that a perpetrator is able to recognise the destructive force of his or her acts."83 For those who have been victims, calling out the perpetrators is just one side of the coin. The perpetrators must be willing to give up their privilege and join in the struggle of the subalterns in order to reverse the injustice inflicted through colonialism and its continuing effects.84Therefore, this view calls the previously colonised and the coloniser to come to a meeting point of ubuntu/botho/vhuthu-the realisation that we are intricately linked to one another, not just an individual to the community but also a people to other peoples, a nation to other nations of the world.

The decolonial project remains incomplete as long as the perpetrators remain unrepentant and unwilling to change. While the efforts of people such as Professor Snyman should be welcomed and appreciated, in the global scheme of things, the structures of coloniality continue to penetrate and shape the fabric of societies and remain resistant to decolonisation. Therefore, the struggle continues.

E CONCLUDING REMARKS

Reading the Hebrew Bible decolonially (or deimperially) requires double consciousness. First is the consciousness of the struggles of the oppressed who produced and preserved the sacred texts to be read, heard, sung and used in prayer. Through the texts of the oppressed, the divine being is heard and worshipped. Second, the consciousness that the sacred texts are not free from imperial influence and ideology prompts us to read the texts with suspicion. Thus, the decolonial option opens several avenues to engage with the sacred texts in life-affirming ways amidst the many death producing situations both in the text and in our current so-called postcolonial world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackroyd, Peter R. Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought of the Sixth Century B.C. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1968. [ Links ]

Albertz, Rainer. "The Controversy about Judean versus Israelite Identity and the Persian Government: A New Interpretation of the Bagoses Story (Jewish Antiquities XI.297-301)." Pages 483-504 in Judah and the Judeans in the Achaemenid Period: Negotiating Identity in an International Context. Edited by Oded Lipschits, Gary N. Knoppers, and Manfred Oeming. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2011. [ Links ]

Assmann, Jan. "Memory, Narration, Identity: Exodus as a Political Myth." Pages 3-18 in Memory, Narration, Identity: Exodus as a Political Myth. Penn State University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994. [ Links ]

Berquist, Jon L. Judaism in Persia's Shadow: A Social and Historical Approach. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995. [ Links ]

________________. "Postcolonialism and Imperial Motives for Canonization." Pages 78-95 in The Postcolonial Biblical Reader. Edited by R. S. Sugirtharajah. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006. [ Links ]

Birch, Bruce C., Walter Brueggemann, Terence E. Fretheim, and David L. Petersen. A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. Reverberations of Faith: A Theological Handbook of Old Testament Themes. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002. [ Links ]

________________. Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Bush, Barbara. Imperialism and Postcolonialism. London: Routledge, 2014. [ Links ]

Carr, David M. The Formation of the Hebrew Bible: A New Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Carr, David M., and Colleen M. Conway. An Introduction to the Bible: Sacred Texts and Imperial Contexts. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. [ Links ]

Crowell, Bradley L. "Postcolonial Studies and the Hebrew Bible." Currents in Biblical Research 7/2 (2009):217-244, https://doi.org/10.1177/1476993X08099543. [ Links ]

Dandamaev, Muhammad A., and Vladimir G. Lukonin. The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. [ Links ]

Davidson, Steed Vernyl. Empire and Exile: Postcolonial Readings of the Book of Jeremiah. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 542. Edited by Andrew Mein and Claudia V. Camp. New York: T&T Clark, 2013. [ Links ]

Davies, Philip R. Memories of Ancient Israel: An Introduction to Biblical History- Ancient and Modern. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. Edited by Brent Hayes Edwards. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skins, White Masks. London: Pluto Press, 1986. [ Links ]

________________. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by C. Farrington. New York: Grove Press, 1968. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

________________. Text and Texture: Close Readings of Selected Biblical Texts. New York: Schocken Books, 1979. [ Links ]

Fitzpatrick-McKinley, Anne. Empire, Power and Indigenous Elites: A Case Study of the Nehemiah Memoir. Leiden: Brill, 2015. [ Links ]

Fulford, Michael. "Territorial Expansion and the Roman Empire." World Archaeol. 23/3 (1992):294-305. [ Links ]

Geyser-Fouché, Ananda B., and Ebele C. Chukwuka. "Tradition Critical Study of 1 Chronicles 21." HTS Theological Studies 77/4 (2021):1-7. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.6420. [ Links ]

Gottwald, Norman K. "Early Israel as an Anti-Imperial Community." Pages 9-24 in In the Shadow of the Empire: Reclaiming the Bible as a History of Faithful Resistance. Edited by Richard A. Horsley. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Griffiths, Gareth. The Myth of Authenticity: Representation, Discourse and Social Practice. Edited by Chris Tiffin and Alan Lawson. Describing Empire. London: Routledge, 1994. [ Links ]

Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1994. [ Links ]

Guillaume, Philippe. Land, Credit and Crisis: Agrarian Finance in the Hebrew Bible. Routledge, 2016. [ Links ]

Hasel, Michael G. "Israel in the Merneptah Stela." Bulletin of American Schools of Oriental Research 296 (1994):45-61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1357179. [ Links ]

Hendel, Ronald. Remembering Abraham: Culture, Memory, and History in the Hebrew Bible. 1st edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [ Links ]

________________. "The Exodus in Biblical Memory." Journal of Biblical Literature 120/4 (2001):601-622. https://doi.org/10.2307/3268262. [ Links ]

Hoffman, Yair. "A North Israelite Typological Myth and a Judaean Historical Tradition: The Exodus in Hosea and Amos." Vetus Testamentum 39/2 (1989):169-182. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519574. [ Links ]

Hoffmeier, James K., Allan R. Millard, and Gary A. Rendsburg, eds. "Did I not Bring Israel out of Egypt?" Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives. Bulletin for Biblical Research Supplement 13. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2016. [ Links ]

Japhet, Sara. "Exile and Restoration in the Book of Chronicles." Pages 331-341 in From the Rivers of Babylon to the Highlands of Judah: Collected Studies on the Restoration Period. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006. [ Links ]

________________. The Ideology of the Book of Chronicles and Its Place in Biblical Thought. Reprint edition. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2009. [ Links ]

Jonker, Louis C. "Playing with Peace : Solomon as the Man of Peace and Rest, and the Temple as the House of Rest." Religions 13/2 (2021):1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010002. [ Links ]

________________. Defining All-Israel in Chronicles: Multi-Levelled Identity Negotiation in Late Persian-Period Yehud. Forschungen Zum Alten Testament 106. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

________________. "The Exile as Sabbath Rest: The Chronicler's Interpretation of the Exile." Old Testament Essays 20/3 (2007):703-719. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC85897. [ Links ]

Keen, Antony G. Dynastic Lycia: A Political History of the Lycians and Their Relations with Foreign Powers, c. 545-362 B.C. Leiden: Brill, 2018. [ Links ]

Knibb, Michael A. "The Exile in the Literature of the Intertestamental Period." The Heythrop Journal 17/3 (1976):253-272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2265.1976.tb00590.x. [ Links ]

Laato, Antti. Message and Composition of the Book of Isaiah: An Interpretation in the Light of Jewish Reception History. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2022. [ Links ]

________________. The Servant of YHWH and Cyrus: A Reinterpretation of the Exilic Messianic Programme in Isaiah 40-55. ConBOT 35. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1992. [ Links ]

Liverani, Mario. Historiography, Ideology and Politics in the Ancient Near East and Israel. Edited by Niels Peter Lemche and Emanuel Pfoh. London: Routledge, 2021. [ Links ]

Loprieno, A. "Slaves." Pages 200-212 in The Egyptians. Edited by S. Donadoni. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1997. [ Links ]

Malcolm X. Malcolm XSpeaks: Selected Speeches and Statements. Edited by George Breitman. 1st Grove Weidenfeld Evergreen ed. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. "On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept." Cultural Studies 21/2-3 (2007):240-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548. [ Links ]

Matthews, Victor Harold, and James C. Moyer. Old Testament: Text and Context. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1997. [ Links ]

Mattingly, David J. Imperialism, Power, and Identity: Experiencing the Roman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

McLeod, John. Beginning Postcolonialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

McNutt, Paula M. Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Mignolo, Walter, and Catherine E. Walsh. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. On Decoloniality. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018. [ Links ]

Morris, Rosalind C., ed. Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Mroczek, Eva. "Moses, David and Scribal Revelation: Preservation and Renewal in Second Temple Jewish Textual Traditions." Pages 91-115 in The Significance of Sinai: Traditions about Sinai and Divine Revelation in Judaism and Christianity. Edited by George J. Brooke, Hindy Najman, and Loren T. Stuckenbruck. Leiden: Brill, 2008. [ Links ]

Mugambi, J.N. Kanyua. From Liberation to Reconstruction: African Christian Theology after the Cold War. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1995. [ Links ]

Na'aman, Nadav. "Royal Vassals or Governors? On the Status of Sheshbazzar and Zerubbabel in the Persian Empire." Pages 403-414 in Ancient Israel and Its Neighbors: Interaction and Counteraction. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2021. [ Links ]

Otto, Eckart. "The Book of Deuteronomy and Its Answer to the Persian State Ideology." Pages 112-122 in Loi et justice dans la litterature du Proche-Orient Ancien. Edited by Olivier Artus. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2013. [ Links ]

Parpola, Simo. National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times, 2004. http://archive.org/details/parpolaidentityarticlefinal. [ Links ]

Phillips, Jerry. "Educating the Savages: Melville, Bloom, and the Rhetoric of Imperialist Instruction." Pages 25-44 in Recasting the World: Writing after Colonialism. Edited by Jonathan White. Parallas: Revisions of Culture and Society. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Punt, Jeremy. "Empire and New Testament Texts: Theorising the Imperial, in Subversion and Attraction." HTS Theological Studies 68/1 (2012): 1-11. [ Links ]

Radner, Karen, Giovanni Baptista Lanfranchi, Michael D. Roaf, and Robert Rollinger. "An Assyrian View on the Medes." Pages 37-64 in Continuity of Empire: Assyria, Media, Persia. Edited by Giovanni Baptista Lanfranchi, Michael D. Roaf, and Robert Rollinger. Padova: Sargon, 2003. [ Links ]

Ramantswana, Hulisani. "Song(s) of Struggle: A Decolonial Reading of Psalm 137 in Light of South Africa's Struggle Songs." Old Testament Essays 32/2 (2019): 464-90. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n2a12. [ Links ]

________________. "Decolonising Biblical Hermeneutics in the (South) African Context." Acta Theologica 36 Supplement 24 (2016):178-203. [ Links ]

Redford, Ronald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, Rolf. The Canonical Hebrew Bible: A Theology of the Old Testament. Leiden: Deo Publishing, 2005. [ Links ]

Schniedewind, William. "Scripturalization in Ancient Judah." Pages 305-321 in Contextualizing Israel's Sacred Writings: Ancient Literacy, Orality, and Literary Production. Edited by Brian B. Schmidt. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Seland, Torrey. "'Colony' and 'Metropolis' in Philo Examples of Mimicry and Hybridity in Philo's Writing back from the Empire?" Études Platoniciennes 7 (2010): 11-33. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesplatoniciennes.621. [ Links ]

Silverman, Jason M. Persian Royal-Judaean Elite Engagements in the Early Teispid and Achaemenid Empire: The King's Acolytes. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament 690. Edited by Andrew Mein and Claudia V. Camp. London: T&T Clark, 2019. [ Links ]

Snyman, Gerrie. "Collective Memory and Coloniality of Being as a Hermeneutical Framework : A Partialised Reading of Ezra-Nehemiah." Old Testament Essays 20/1 (2007):53-83. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC85859. [ Links ]

________________. "Responding to the Decolonial Turn: Epistemic Vulnerability." Missionalia 43/3 (2015):266-291. https://doi.org/10.7832/43-3-77. [ Links ]

Snyman, S.D. (Fanie). "Exploring Exodus Themes in the Book of Amos." Stellenbosch Theological Journal 7/1 (2021):1-22. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2021.v7n1.a08. [ Links ]

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. "Can the Subaltern Speak?" Pages 64-111 in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. Edited by Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Toorn, Karel Van der. Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible. Harvard University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

________________. The Exodus as Charter Myth. Leiden: Brill, 2001. [ Links ]

Valk, Jonathan. "Crime and Punishment: Deportation in the Levant in the Age of Assyrian Hegemony." Bulletin of American Schools of Oriental Research 384 (2020):77-103. https://doi.org/10.1086/710485. [ Links ]

Veracini, Lorenzo. Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. [ Links ]

Villa-Vicencio, Charles. A Theology of Reconstruction: Nation-Building and Human Rights: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Von Rad, Gerhard. Old Testament Theology. Vol. I. London: SCM, 1975. [ Links ]

Vriezen, Th Theodoor Christiaan, and Adam Simon van der Woude. Ancient Israelite and Early Jewish Literature. Leiden: Brill, 2005. [ Links ]

Williams, R. J. "'A People Come out of Egypt': An Egyptologist Looks at the Old Testament." Pages 231-252 in Congress Volume Edinburgh 1974. Edited by John Emerton. Vol. 28 of Vetus Testament Supplement. Leiden: Brill, 1975. [ Links ]

Wilson, Ian. History and the Hebrew Bible: Culture, Narrative, and Memory. Leiden: Brill, 2018. [ Links ]

Wilson, John A. "Hymn of Victory of Mer-Ne-Ptah (The 'Israel Stela')." Pages 37678 in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Edited by J. B. Pritchard. 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. [ Links ]

Yoder John M. and John H. Yoder. "Exodus and Exile: The Two Faces of Liberation." CrossCurrents 23/3 (1973):297-309. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, Walther. Old Testament Theology in Outline. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1978. [ Links ]

Submitted: 11/05/2023

Peer-reviewed: 03/06/2023

Accepted: 03/06/2023

Hulisani Ramantswana, University of South Africa, Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, P.O. Box 392, UNISA, 0003; Email: ramanh@unisa.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6629-9194.

1 The initial draft of this essay was presented at the International Conference on Interpreting Sacred Texts in Changing Contexts in Africa held at the University of Ghana, Accra in 2022.

2 W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, ed. Brent Hayes Edwards, Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 9.

3 Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. C. Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1968), 155.

4 Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks (London: Pluto Press, 1986), 83.

5 Nelson Maldonado-Torres, "On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept," Cultural Studies 21/2-3 (2007):240-270; Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa: Myths of Decolonization (Dakar: CODESRIA, 2013); Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, "Global Coloniality and the Challenges of Creating African Futures," The Strategic Review for Southern Africa 36/2 (2014):181-202; W. M. Kassaye Nigusie and N. V. Ivkina, "Post-Colonial Period in the History of Africa: Development Challenges," in Africa and the Formation of the New System of International Relations: Rethinking Decolonization and Foreign Policy Concepts, ed. Alexey M. Vasiliev, Denis A. Degterev, and Timothy M. Shaw, Advances in African Economic, Social and Political Development (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021), 39-54.

6 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "Can the Subaltern Speak?," in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader (ed. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman; New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 64-111; Rosalind C. Morris, ed., Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

7 As translated in John A. Wilson, "Hymn of Victory of Mer-Ne-Ptah (The 'Israel Stela')," in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ed. J. B. Pritchard, 3rd ed.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 376-378.

8 Michael G. Hasel, "Israel in the Merneptah Stela," BASOR 296 (1994):45, https://doi.org/10.2307/1357179.

9 Hasel, "Israel in the Merneptah Stela," 54.

10 Ronald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 125-237; Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1994), 392-393.

11 Norman K. Gottwald, "Early Israel as an Anti-Imperial Community," in In the Shadow of the Empire: Reclaiming the Bible as a History of Faithful Resistance (ed. Richard A. Horsley; Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 15.

12 The following note regarding Canaanite prisoners during the reign of Ramesses III states: I have brought back in great those that my sword has spared, with their hands tied behind their backs before my horses, and their wives and children in tens of thousands, and their livestock in hundreds of thousands. I have imprisoned their leaders in fortress bearing my name, and I have added to them chief archers and tribal chiefs, branded and enslaved, tattoed with my name, and their wives and children have been treated in the same way. The above quote is from Harris Papyrus I, translated by A. Loprieno, "Slaves," in The Egyptians (ed. S. Donadoni; Chicago: University of Chicago, 1997), 204-205. In earlier periods, Thutmose took over 7300 Canaanite prisoners, and his successor, Amenhotep II took even more, about 89 600 Canaanite captives (Ronald Hendel, "The Exodus in Biblical Memory," JBL 120/4 [2001]:606, https://doi.org/10.2307/3268262).

13 In the Amarna Letters (ca. 1360-1355), there are correspondences between Egyptian pharaoh and Canaanites rulers, which records the human tributes to Egypt: 10 women sent by 'Abdi-Astarti of Amurru (EA 64); 46 females and 5 males sent by Milkilu of Gezer (EA 268), [x] prisoners and 8 porters sent by Ábdi-Heba of Jerusalem (E 287); 10 slaves, 21 girls, and [80] prisoners sent by 'Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem (EA 288); 20 girls sent by Subandu (place unknown; EA 301) [x +] 1 young servant, 10 servants, and 10 maidservants sent by an unknown ruler (EA 309); [2]0 first-class slaves requisitioned by Pharaoh (along with the ruler's daughter in marriage; EA 99); 40 female cupbearers requisitioned by Pharaoh of Milkilu of Gezer (EA 369). The above quote is from Hendel, "The Exodus in Biblical Memory," 605-606.

14 R. J. Williams, "'A People Come out of Egypt': An Egyptologist Looks at the Old Testament," in Congress Volume Edinburgh 1974 (ed. John Emerton, vol. 28 of Vetus Testament Supplement; Leiden: Brill, 1975), 231-232.

15 Yair Hoffman, "A North Israelite Typological Myth and a Judaean Historical Tradition: The Exodus in Hosea and Amos," Vetus Testamentum 39/2 (1989):170.

16 Walther Zimmerli, Old Testament Theology in Outline (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1978), 25; Gerhard von Rad, Old Testament Theology (London: SCM, 1975), I:176.

17 Bruce C. Birch et al., A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1999), 99, 121 -123.

18 Rolf Rendtorff, The Canonical Hebrew Bible: A Theology of the Old Testament (Leiden: Deo Publishing, 2005), 47.

19 Walter Brueggemann, Reverberations of Faith: A Theological Handbook of Old Testament Themes (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 72; Michael Fishbane, Text and Texture: Close Readings of Selected Biblical Texts (New York: Schocken Books, 1979), 63-64, 121-25; Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 358-368.

20 Jan Assmann, "Memory, Narration, Identity: Exodus as a Political Myth," in Memory, Narration, Identity: Exodus as a Political Myth (Penn State University Press, 2010), 3-18.

21 James K. Hoffmeier, Allan R. Millard, and Gary A. Rendsburg, eds., "Did I not Bring Israel out of Egypt?" Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives (Bulletin for Biblical Research Supplement 13; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2016).

22 The exile and return from Babylon mark a significant point, which may well be viewed as the rebirth of Israel. As Ackroyd notes, the Babylonian exile "inevitably exerted a great influence upon the development of theological thinking." Furthermore, in dealing with the Babylonian exile, the interpreters should also attempt "to understand the attitude, or more properly a variety of attitudes, taken up towards that historic fact" (Peter R. Ackroyd, Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought of the Sixth Century B.C. (Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press, 1968), 237-238.)

23 Hendel, "The Exodus in Biblical Memory," 608.

24 Gottwald, "Early Israel as an Anti-Imperial Community," 17.

25 John M. Yoder and John H. Yoder, "Exodus and Exile: The Two Faces of Liberation," CrossCurrents 23/3 (1973):300.

26 Yoder and Yoder, "Exodus and Exile," 300.

27 Paula M. McNutt, Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999), 78-81.

28 For more on cultural memory and production of Israel's narratives, see Philip R. Davies, Memories of Ancient Israel: An Introduction to Biblical History-Ancient and Modern (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 105-22; Ronald Hendel, Remembering Abraham: Culture, Memory, and History in the Hebrew Bible, 1st edition. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Ian Wilson, "History and the Hebrew Bible: Culture, Narrative, and Memory," in History and the Hebrew Bible: Culture, Narrative, and Memory (Brill, 2018).

29 Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997), 177.

30 See the following studies, Hoffman, "A North Israelite Typological Myth and a Judaean Historical Tradition"; S.D. (Fanie) Snyman, "Exploring Exodus Themes in the Book of Amos," STJ 7/1 (2021):1 -22; Karel van der Toorn, The Exodus as Charter Myth (Leiden: Brill, 2001).

31 Hoffman, "A North Israelite Typological Myth," 181.

32 Snyman, "Exploring Exodus Themes in the Book of Amos," 17.

33 Steed Vernyl Davidson, Empire and Exile: Postcolonial Readings of the Book of Jeremiah (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 542; ed. Andrew Mein and Claudia V. Camp (New York: T&T Clark, 2013), 181-182.

34 Antti Laato, The Servant of YHWH and Cyrus: A Reinterpretation of the Exilic Messianic Programme in Isaiah 40-55 (ConBOT 35; Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1992), 155.

35 In Laato's view, Isa 55:3-5 reinterprets the hope for a restoration of the Davidic dynasty by deferring it to the future. For Laato, the Yehud community could experience the blessing of the Davidic dynasty without necessarily the restoration of the Davidic dynasty (Laato, The Servant of YHWH and Cyrus; Antti Laato, Message and Composition of the Book of Isaiah: An Interpretation in the Light of Jewish Reception History [Berlin: de Gruyter, 2022], 258-259).

36 However, the idea of exile having come to an end does not find support in other biblical literature. For example, in Dan 9, the end of exile is viewed as a first phase, but not the complete end of exile. See Michael A. Knibb, "The Exile in the Literature of the Intertestamental Period," Heythrop J. 17/3 (1976):253-272. For more on the Chronicler's view of the end of exile as Sabbath rest, see Louis Jonker, "The Exile as Sabbath Rest: The Chronicler's Interpretation of the Exile," OTE 20/3 (2007):703-719.

37 Sara Japhet, The Ideology of the Book of Chronicles and Its Place in Biblical Thought (Reprint edition; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2009); Ananda B. Geyser-Fouché and Ebele C. Chukwuka, "Tradition Critical Study of 1 Chronicles 21," HTS 77/4 (2021):7.

38 Sara Japhet, "Exile and Restoration in the Book of Chronicles," in From the Rivers of Babylon to the Highlands of Judah: Collected Studies on the Restoration Period (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006), 340.

39 Jonker, "The Exile as Sabbath Rest," 715.

40 Jon L. Berquist, "Postcolonialism and Imperial Motives for Canonization," in The Postcolonial Biblical Reader (ed. R.S. Sugirtharajah; Oxford: Blackwell, 2006), 86.

41 For an overview of ancient Israel's sacred texts, see David M. Carr and Colleen M. Conway, An Introduction to the Bible: Sacred Texts and Imperial Contexts (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010); Victor Harold Matthews and James C. Moyer, Old Testament: Text and Context (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1997).

42 Th Theodoor Christiaan Vriezen and Adam Simon van der Woude, Ancient Israelite and Early Jewish Literature (Leiden: Brill, 2005).

43 Not all forms of government should be equated with empire. As Punt argues, regarding the theorisation of empire: First, Empire was quite evidently as 'structural reality', comprised of and operating in terms of a principal binary of centre and margins, where the centre is often symbolised by a city and margins are that which are subordinated to the centre - at a political, economic or cultural level. Secondly, structurally Empire was not a uniform phenomenon in a temporal or spatial sense but 'differentiated in constitution and deployment regardless of many remaining similarities. It is with a third, and more contested claim about Empire that further theorisation becomes vital. The claim is that the reach and power of Empire was of such an extent that it influenced and impacted in direct and indirect, in overt and subtle ways, 'the entire artistic production of center and margins, of dominant and subaltern, including their respective literary productions'. See Jeremy Punt, "Empire and New Testament Texts: Theorising the Imperial, in Subversion and Attraction," HTS Theological Studies 68/1 (2012):5-6.

44 In decolonial and postcolonial perspectives, the colonised use(d) various strategies to assert their self-worth and resist imperial dictates. Mimicry is among the various strategies at the disposal of the colonised. However, in mimicking the empire or the coloniser, the colonised do not simply intend to duplicate strategies, patterns, values, and norms of the empire; rather, in the mimicry also flows a negation. Cf. Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 122. However, as Seland notes, "To some extent the colonizer might also encourage the colonized subjects to mimic the colonizer, but it might also evolve as a strategy on the side of the colonized in order to survive or even to conquer the culture of the colonizer by enlarging on common aspects"; Torrey Seland, "'Colony' and 'Metropolis' in Philo. Examples of Mimicry and Hybridity in Philo's Writing Back from the Empire?," Études Platoniciennes 7 (2010):18.

45 See Louis C. Jonker, Defining All-Israel in Chronicles: Multi-Levelled Identity Negotiation in Late Persian-Period Yehud (Forschungen Zum Alten Testament 106; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016); Louis C. Jonker, "Playing with Peace : Solomon as the Man of Peace and Rest, and the Temple as the House of Rest," Religions 13/2 (2021):1-12.

46 Bradley L. Crowell, "Postcolonial Studies and the Hebrew Bible," Currents in Biblical Research 7/2 (2009):233.

47 Crowell, "Postcolonial Studies and the Hebrew Bible," 233.