Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.35 n.3 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2022/v35n3a5

ARTICLES

A Contextual and Canonical Reading of Psalm 35

Daniel Simango

North-West University

ABSTRACT

This article is a contextual and Canonical reading of Ps 35 in order to grasp its content, context and theological implications. The basic hypothesis of this study is that Ps 35 should not be interpreted in isolation, but that the psalm will be best understood when read in its total context viz., the historical setting, life-setting and canonical setting as well as the literary genre. It is argued that a contextual and canonical reading of Ps 35 can serve as a counterbalance to arbitrary decisions on the interpretation of the psalm. A brief overview of the structure and outline of this psalm is given before probing the literary genre, historical setting, life setting as well as the canonical context. The article concludes by discussing the imprecatory implications and message of Ps 35 to the followers of YHWH.

Keywords: Psalm 35; Contextual, Canonical Study; Imprecatory Psalms; Imprecation.

A INTRODUCTION

Psalm 35 is frequently classified as an imprecatory psalm.1 In this psalm, the psalmist, who suffers unjustly at the hands of his enemies who sought to destroy his life and reputation, asks God to pour out judgment on his enemies. The psalmist prays for his own vindication and his enemies' downfall, but he also vows to praise YHWH for his deliverance (vv. 9-10, 18 and 27-28).

In this article, I shall consider the structure and interpretive summary of Ps 35. Subsequently, an extra-textual and intertextual reading of a poetic text will be applied to Ps 35.

Extra-textual relations refer to the biographical particulars of the author and his/her world. This helps the reader to understand how the content functions in its context. In the extra-textual analysis, the literary genre and historical setting, life setting, and canonical context of Ps 35 will be discussed.

Inter-textual relations, on the other hand, refer to the relations between a specific text and other texts. This helps the reader to understand the way in which the content of inter-related texts affects the theological implications of Ps 35.

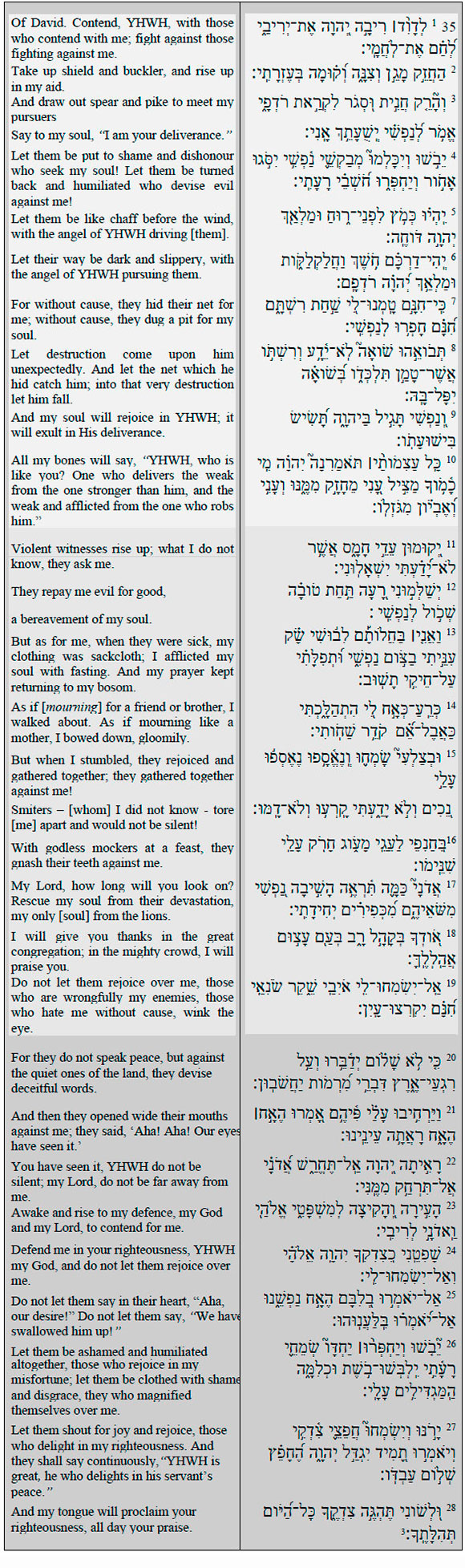

In this article, the Hebrew text and the author's own translation of Ps 35 are given as well as the basic literary structure of the psalm. For practical purposes, Ps 35 will be sub-divided into cola, strophes, and stanzas.

B TEXT AND TRANSLATION2

C THE STRUCTURE4 AND OUTLINE5 OF PS 35

When considering the structure of Ps 35, the most conspicuous feature is the vow or resolve to praise God for his deliverance or an expression of certainty that God will save the psalmist in the time of his need (vv. 9-10, 18 and 28).6

The repetition of this vow or resolve to praise God in verses 9-10, 18 and 28 functions as an important structure maker, according to which Ps 35 may be sub-divided into three stanzas-verses 1-10, 11-18, 19-28. Each stanza consists of a petition, a lament and a vow or a resolve to praise the Lord for his help (vv. 9-10, 18, 28).7 This three-fold division of the psalm is supported by many scholars.8

The imagery of lawsuit and war introduced in the first verse of the poem fits very well into the outline of the Psalm. Stanza I (vv. 1 -10) develops the image of the battlefield. Stanza II (vv. 11 -18) develops the image of a lawsuit. Finally, in Stanza III, both images are brought together (vv. 19-28).9

The three stanzas of Ps 35 therefore may be sub-divided into the following strophes10:

Stanza I (1-10) A Military Threat

Strophe A (1a-3b) Urgent call to YHWH, the divine advocate and warrior

Strophe B (4a-8c) A series of imprecations against enemies

Strophe C (9a-10c) A promise to rejoice and praise YHWH

Stanza II (11-18) The Trial

Strophe D (11a-12b) The suppliant's distress

Strophe E (13a-14b) The suppliant's confession of innocence

Strophe F (15a-16b) Reiteration of his distress

Strophe G (17a-18b) Renewed appeal and vow to give thanks

Stanza III 19-28 A Prayer for Victory

Strophe H (19a-21b) Imprecation against his enemies

Strophe I (22a-24a) Renewed petition for YHWH to intervene

Strophe J (24b-26d) Further imprecation against his enemies

Strophe K (27a-28b) Call to praise YHWH and vow to proclaim his righteousness

Stanza I (vv. 1-10): The psalm commences with an urgent call for YHWH to intervene in the psalmist's time of great need (v. 1). The psalmist wants YHWH to be his advocate and warrior. He appeals to YHWH to use both defensive and offensive weapons against his pursuers (vv. 2-3). He anticipates the victory that would come when YHWH comes to his rescue (v. 3). He is confident that when YHWH fights, his enemies would experience shame, dishonour, humiliation, dispersion, retreat and sudden destruction by their own devices (vv. 4-8). The suppliant vows to rejoice and praise YHWH continuously in response to the anticipated deliverance by YHWH (v. 10).

Stanza II (vv. 11-18): The suppliant describes his distress when violent witnesses stood up and falsely testified against him in an outrageous way with the purpose of harming and discrediting him (vv. 11). The suppliant is innocent and has no clue as to the false allegations made by his enemies (vv. 11). He has done good deeds to his enemies but they have returned evil for good and this causes the suppliant's heart to experience deep emotional pain (vv. 12-13). When his enemies were sick, the suppliant grieved over their illness as much as he would have grieved over the death of his nearest kin (vv. 13-14). He expressed his deep grief by wearing sackcloth, fasting, and praying for his enemies' healing. However, when he stumbled, the attackers did not do the same for him. They surrounded him and continually tore him apart with unwarranted, slanderous accusations (v. 15). They expressed their anger and hatred ruthlessly toward him (vv. 15c-16). In response to the enemies' persecution, the suppliant makes a personal call to God to intervene (vv. 17). He wants God to rescue him from the life-threatening attacks of his enemies (v. 17). He also vows to give thanks and praise to YHWH publicly among many people (v. 18).

Stanza III (vv. 19-28): The suppliant then asks God to prevent his enemies from rejoicing over his misfortunes because his enemies are hostile and deceitful people (vv. 19-21; 25). The suppliant makes a renewed petition to YHWH to save him from his enemies (vv. 22-23). He wants YHWH to execute justice by defending and declaring him innocent of all charges according to his divine righteousness (v. 24). The psalmist prays that his enemies who have been rejoicing at his misfortune would experience the shame and humiliation that they had planned for him (inversion of roles) (v. 26). The psalm ends with the suppliant's call to his friends, who want to see him declared innocent, to praise YHWH for his greatness because he loves to set things right by giving peace to his servants who are suffering and are in a vulnerable situation. YHWH sets them free from their oppressors (v. 27-28).

D LITERARY GENRE AND HISTORICAL AND LIFE SETTING OF PS 35

1 Main views about the genre of Ps 35

Psalm 35 has been classified traditionally as an individual lament or complaint11 since the usual characteristics of a lament are present, viz., a petition for deliverance (vv. 1-3, 17, 22-25), a petition for judgment upon enemies (vv. 4-6, 8, 19, 26), complaint (vv. 7, 11-12, 15-16, 20-21), a confession of innocence (vv. 13-14) and a vow to praise (vv. 9-10, 18, 28).

Both Craigie12 and Eaton13 classify Ps 35 as a "royal prayer for international crisis" since the psalm is a prayer of a king who is faced with international enemies. In his prayer, the king asks God for help and deliverance from his enemies. Craigie and Eaton base their argument on the presence of military language in the psalm.

Unlike Eaton and Craigie, Davidson14 views Ps 35 as an individual lament and argues that the dominant language in the psalm is that of the "law of court." He views the whole psalm as a trial in which the psalmist's plea is for a verdict of not guilty with respect to the charges brought against him.

2 Genre of Ps 35

Eaton15 and Craigie16 seem to reach their conclusion that the psalm is not a lament but "a royal prayer for international crisis" because they focus primarily on the battle imagery in the psalm. As seen from the interpretation of the psalm (i.e. Section D), both the battle and the courtroom images are developed throughout the psalm. Therefore, when reading the psalm, both metaphors are present but after verse 11 (and for the greater part of the psalm), the courtroom imagery predominates. Although both Craigie and Eaton emphasise the battle imagery over against the courtroom imagery and they conclude that the psalm is a royal prayer for an international crisis, Davidson emphasises the courtroom imagery and concludes that the whole psalm is a trial.

On the basis of its structure and content, Ps 35 has been classified as an individual lament. The usual characteristics of a lament17 are present in the psalm.

3 Life-setting of Ps 35

Craigie18 argues that though the evidence is not firm, Ps 35 could have been utilised in the temple, perhaps in a liturgical setting, either as a consequence of grave military threat or else prior to the king's departure for battle to meet his adversary. He says that if the latter is the case, then, there are parallels between Ps 35 and Ps 20. Craigie argues that the congregational setting of the ritual is supported by the reference to the "great congregation" (v. 18), to the "quiet ones" (v. 20), which he interprets as a description of a pious congregation and the call to praise in verse 27, which he interprets as a congregational response to praise. Craigie's point is largely determined by his view of the genre of this Psalm (see 2.5.1).

Gerstenberger19 views the original setting of Ps 35 as a "private cultic" ritual and the psalm would have been used by a suffering individual "as a central part of the recitations that were obligatory for the sufferer who underwent such rehabilitating ritual in the circle of friends and family."

Mays20 says Ps 35 was "composed for the typical situation in which a person needed vindication because of the damaging hostility of others." He sees the psalm as a formal version of David's impromptu prayer designed for ritual at a shrine.

As seen above, there are different proposals with regards to the life-setting of the psalm. The psalm was probably used in the temple but there are different views about the cultic setting of the psalm. The language and imagery of Ps 35 are open-ended enough to apply to a variety of circumstances. Therefore, Ps 35 was probably a resource for sufferers throughout generations. The psalm served as a prayer for help and a testimony to God's character. God is seen as the one who helps, delivers and provides for the weak, the needy and the vulnerable.21

4 Authorship and historical situation of Ps 35

Keeping in mind the interpretation of the psalm (i.e. Section D), it is important to discuss the possible author and historical situation of the psalm.

The title of Ps 35 is "of David." This may be translated to mean "about David" or "for David," indicating that the psalm concerns or is dedicated to him. This title could also be an editorial comment that indicates that the psalm belongs to the collection of David and is part of the first group of psalms (341).

Some exegetes22 argue that there are many points of correspondence between the statements of Ps 35 and the experiences of David in Saul's day.

This may be suggested if one compares 1 Sam 20, 23, 24, 25 and 26. These correspondences and the superscription "Of David" do not conclusively prove Davidic authorship but may introduce the possibility that David may have had a hand in the writing of Ps 35. Psalm 35 does not have explicit references to the temple; therefore, this may support my hypothesis that David may have had his hand in the writing of the psalm.

As seen from the interpretation of Ps 35 (i.e., Section D), the suppliant could have faced a military threat that encompassed a lawsuit, and this seems to support the tradition of Davidic authorship. David faced a military threat from King Saul and his army (1 Sam 20, 23, 24, 24 and 26). David had an intimate relationship with Saul and his son, Jonathan (cf. 1 Sam 16:21-23; 18:1-5). Saul also referred to David as his son (1 Sam 24:16; 26:21). David even referred to Saul as his father (1 Sam 24:11). The psalmist's enemies wanted to kill the psalmist (Ps 35:4 & 17). Saul wanted to take David's life (1 Sam 18:10-11, 25; 19:1; 20:30-31). The psalmist's enemies pursued his path (verses 4-6). Saul and his army pursued David (1 Sam 23:8; 24:2). The psalmist was innocent and did not wrong his enemies (vv. 7, 19). David was innocent and did not wrong Saul in any way (1 Sam 19:4-5; 21:32; 24:11; 26:18). The psalmist wants YHWH to be his advocate and judge (Pss 35:1a, 23, 24a). David appeals to God to judge between Saul and him (1 Sam 24:12, 15). The psalmist uses legal, judicial, military and hunting metaphors in Ps 35. David could have been familiar with the judicial metaphor because he lived at King Saul's palace (1 Sam 18). He was also a warrior in charge of Saul's army (1 Sam 18:5ff) and this could also explain the use of military metaphors. David was a shepherd (1 Sam 16:11; 17:14, 20, 34-37) and most shepherds knew how to hunt for animals and birds. This could explain the use the hunting metaphors in Ps 35. Finally, the psalmist does not have a vindictive spirit, which is implied by his desire not to rejoice in his enemies' downfall but in YHWH's deliverance (Ps 35:9). Twice David had the opportunity to kill Saul but each time he spared his life (1 Sam 24, 26).

These similarities suggest the possibility that Ps 35 could have been written by David or by someone who was reflecting on David's life when he was attacked and pursued by Saul.

E CANONICAL CONTEXT OF PS 35

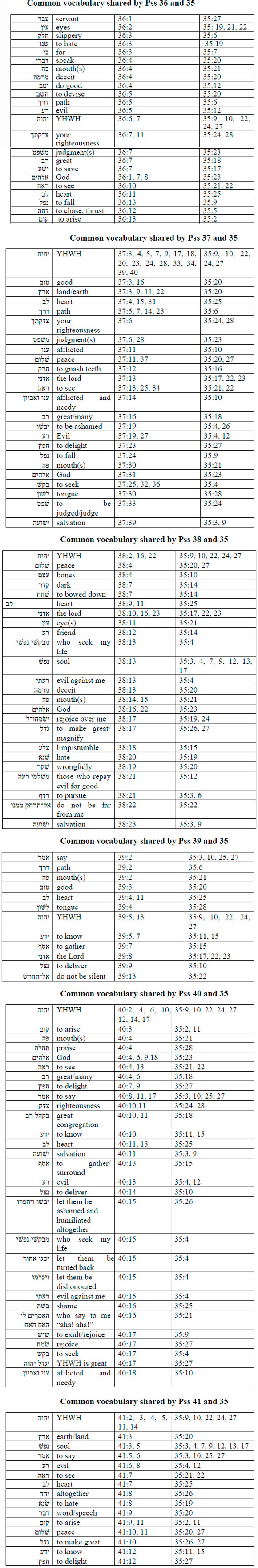

Psalm 35 has לְׁדָ וִ֨ד ("Of David") as its superscription. This superscription indicates the existence of a collection23 within which Ps 35 had been placed and belonged.24 The superscription לְׁדָ וִ֨ד. means that Ps 35 belongs to the collection associated with David, designated Book I (Pss 1-41 or 3-41) since this book of the Psalter, in which Ps 35 is placed, mentions David in the superscription of nearly every psalm. There is another Davidic collection, Book II of the Psalter, formed by Pss 41-72.25 The present discussion only investigates the significance of the placement of Ps 35 in Book I. Regarding the structure of Book I of the Psalter, Pss 1 and 2 (which do not mention David in the superscription) serve as the introduction or prologue to (at least) Book I, while the doxology in Ps 41:13 concludes Book I.26 Psalms 3-41 are all Davidic psalms except Pss 10 and 33. Book I is mainly characterised by individual psalms and pleas for deliverance27 and it can be further subdivided into the following groups: Pss 3-14; 15-24; 25-34 and 35-41.28 Within the last subgroup, Pss 35-37 focus on instructions about evil in the world and Pss 38-41 are pleas for deliverance.29

From the above discussion on the general structure and the subdivisions of Book I, Ps 35 can be read together with the psalms in the fourth sub-group of Book I of the Psalter, Pss 35-41.30 The significant patterns, topics or themes in Pss 35-41 may indicate that the canonical context does shed light on Ps 35.

Psalm 35 and Pss 36-41 in the fourth sub-group are inter-related through many common words, phrases and themes. Psalms 35 and 41 share common vocabulary:

As a follow-up of the lament over the wicked enemies in Ps 35, Ps 36 gives a thorough analysis of the character of the godless and offers a praise of the righteousness of YHWH to which appeal was made in Ps 35. In both psalms, the psalmist's enemies or the wicked are characterised by their deceitful words (35:20; 36:4) and do not do good (35:12-16; 36:4). The theme of YHWH's righteousness is seen in both psalms-in Ps 35, the psalmist asks YHWH to judge him in his righteousness (v. 24) and in Ps 36, the psalmist exhorts God to continue to show his righteousness to the upright in heart (v. 10).

The theme of doing good is also seen in Ps 37. Unlike the wicked who do not do good, the righteous are exhorted to do good (v. 3; cf. 35:12; 36:4). The theme of the wicked plotting evil and gnashing their teeth against the righteous is seen in Pss 35 and 37 (see 35:7-8; 37:12; 35:16; 37:12). In Ps 35:10, YHWH delivers the afflicted and needy from their oppressors and in contrast, the wicked plot to use their weapons against them and even to kill them (Ps 37:14). Psalm 35 laments over the wicked enemies who directed their deceitful words against the peace-loving people of the land (35:20) and in Ps 37, the seeming prosperity of wicked is transitory and they are going to be cut off (37:1-9), while the afflicted or humble shall inherit the land and enjoy abundant peace (37:11).

Psalm 35 shares several common themes with Ps 38. In both psalms, the psalmist observes mourning rituals (35:14; 38:7-8). The theme that the psalmist's enemies are seeking to kill him and have prepared snares or traps, which refers to the crafty or treacherous plans of the wicked in Ps 35:4, 7-8 is reiterated in Ps 38:12. In Pss 35 and 38, the psalmist's enemies magnify themselves over the psalmist (35:26; 38:17), without justification, they repay good with evil (35:12; 38:21) and their hatred is inspired by their own sinfulness (35:19; 38:19). In both psalms, the psalmist does not want his enemies to rejoice over him (35:19, 24-25; 38:17) and he does not want God to forsake him/to be far away from him but to intervene and to help him in his time of need (35:22-23; 38:22; cf. 39:13). In both psalms, YHWH is the psalmist's salvation (35:3; 38:22).

Psalm 35 has few thematic links with Ps 39. Both psalms speak of the distress of the suppliant (35:11-12, 15-16; 39:2-3). In both psalms, the suppliant is in need of deliverance and he makes an urgent call for YHWH to deliver him from his predicament (35:1-3, 22-24; 39:12-13).

Psalm 35 also shares several common themes with Ps 40. In both psalms, the psalmist makes an urgent call for YHWH to deliver him from his enemies (40:14, 18; 35:1-3, 17, 22-23) because his enemies want to take the psalmist's life (40:15; 35:4) and are rejoicing over him saying "Aha, aha!" (40:15; 35:25). Therefore, in both psalms, the psalmist wants YHWH to put to shame and dishonour his enemies (40:15; 35:26, 4). In both psalms, the psalmist also calls the righteous to praise YHWH (40:17; 35:27). Both psalms speak of the great congregation in which the speakers raise their voices to praise God (40:10-11; 35:18). In Ps 35, the psalmist implies that he is afflicted and needy (v. 10), whereas in Ps 40, the psalmist explicitly says that he is afflicted and needy (v.18). Psalm 40:15-17 generally corresponds to Ps 35:25-27; thus, forming an inclusion for the fourth sub-section in the first Book of Psalms.31

Therefore, Ps 35 and the fourth subgroup (35-41) have important philological and thematic links. The most common theme in this group of psalms is the theme of deliverance-YHWH is the psalmist's salvation or deliverance. YHWH alone is a refuge in times of trouble.32 He rescues the afflicted and needy from their oppressors, the wicked. YHWH rescues the afflicted by punishing the wicked and bringing shame and dishonour to them. Among these psalms, our imprecatory Ps 35 provides admonition to the followers of YHWH. The psalm exhorts the listeners/readers to call on YHWH rather than to rely on themselves whenever they are being persecuted by their enemies because YHWH is the divine warrior who will fight and defend his people from their oppressors. YHWH is also the all-seeing witness and judge. YHWH is a righteous judge and the champion of justice. He sees and knows all that is going on. He is going to execute his justice by delivering and vindicating the righteous and by punishing the wicked in his own time. Therefore, the listeners/readers should continuously trust in YHWH, in the midst of difficulties or persecution, for their deliverance and refuge.

F IMPRECATORY IMPLICATIONS IN PS 35

The content of Ps 35 has shown a number of metaphors: for God (warrior and judge), the psalmist (a victim on the battlefield and in the law of court) and for the enemies (army, hunters, violent witnesses).

The psalm also shows that the psalmist is thirsting for justice;33 he is innocent and is the victim of his enemies. His enemies are devising evil, plotting to kill him, and pursuing him (v. 4). He is innocent (vv. 7, 13-14, 19). His enemies have falsely accused him of things or crimes that he does not know (vv. 11b, 21). They have mocked and ridiculed the psalmist publicly in a scornful manner (vv. 19-21). Therefore, he pleads for justice on the grounds that God's justice should prevail at all times (vv. 7-8; 11-12; 19-24). Justice is the general tenor of the psalm. The psalmist asks YHWH to set things right as the divine warrior, advocate, and judge because his glory and righteousness are at stake (vv. 9-10; 22-24; 28) if the suffering of the innocent continues in the hands of the wicked or the unrighteous. God's work of setting things right in the world (vv. 22-24, 27) will necessarily mean that God fights (vv. 1 -10) and judges the wicked, hence, the military and courtroom imagery are understandable and appropriate. The psalmist is confident that if YHWH is to act as a judge, he would be declared righteous while his detractors would be found guilty and be humiliated and disgraced publicly. YHWH's greatness is seen in his pleasure to set things right for the suffering and the vulnerable thereby providing peace to his servants (v. 27). Therefore, the psalmist is not so much wishing his enemy to be cursed or to be punished severely but rather he is propelled by a desire for righteousness and justice to prevail with all the necessary consequences (see vv. 9-10; 22-24; 28).

The psalmist's prayer against the enemies is not a selfish, vengeful prayer. He does not have a vindictive spirit toward his enemies. The psalmist is not looking for his enemies' downfall for the sake of vengeance. Although he prayed at great length about his attackers' downfall, the object of the psalmist's rejoicing is not their downfall but YHWH's deliverance (v. 9). The focus of this psalm is not on personal revenge but on YHWH's deliverance. The occasion of the psalmist's thanksgiving (vv. 9-10; 18 and 28) is YHWH's deliverance. The psalmist vows to praise YHWH because he delivers his people from the oppressor (vv. 9-10, 27). YHWH's deliverance of the psalmist is the main theme of the whole psalm. The canonical context of Ps 35, Pss 3541, also confirms this as the main theme.

Throughout Ps 35, the psalmist is also portrayed as not having a vindictive spirit. His past conduct is contrasted to that of his attackers. When his attackers were sick, he was very sympathetic. He wore sackcloth, fasted, prayed for them and mourned for them as if they were his own friends or relatives (vv. 13-14). In other words, the psalmist is shown to be like the New Testament believer-he loves his enemies as he loves himself, when they are sick, he prays and fasts for them as if they were his own nearest kin (cf. Matt 5:44; Luke 6:27-35). The psalmist emphasises his pure motives in a number of ways:

• In verse 24a, the suppliant asks YHWH to judge him. Vindication comes not only when the enemies are the object of God's judgement, but also through the suppliant's own heart and motives.

• The psalm starts with battle imagery - even mentioning the spear and pike (3a), which could be used to kill the enemies of the suppliant. However, there is a development. The metaphor of battle gives way to the court metaphor. Although the suppliant wanted to invoke force, he eventually settles for justice, whereby the enemies are humiliated and silenced (vv. 4, 26).

• In the end, God's glory becomes more important than vengeance. Thus, the psalm shows initial violent emotions which are tempered and made servile to God's glory.

The psalmist in Ps 35 is not vengeful in act or spirit. In response to his enemies' hostility, the psalmist does not retaliate but he entrusts vengeance to God (v. 17). The psalmist submits his prayer to God and leaves vengeance to God. It is YHWH who is to punish the enemies rather than the psalmist. It is YHWH who would disgrace and humiliate his enemies (vv. 4, 26).

The psalmist also prays for an inversion of roles - he wants his enemies to get a dose of their own medicine.

• Since the enemies were pursuing the psalmist (v. 3a), the psalmist asks God to fight for him (vv. 1 -3). He wants the angel of YHWH to pursue his enemies (vv. 5-6). He wants his enemies to experience the total humiliating defeat that they had planned for him.

• Since the enemies had hidden a net for the psalmist (v. 7), the psalmist prays for his enemies to be caught in the very trap or treachery they had intended for him (v. 8). The enemies are to experience what they had in store for the psalmist.

• Since the psalmist's affliction by the enemies was enacted publicly before others (vv. 11 -12; 15-16; 21), the psalmist prays for his enemies to be ashamed and humiliated publicly (vv. 4; 26). The psalmist is also confident that he will proclaim thanksgiving and praise publicly, in the gathering of God's people (vv. 18).

• Since the psalmist was mocked publicly by his enemies which brought about shame and disgrace (vv. 20-21), his enemies are to be ashamed and humiliated publicly. The suppliant, who has been humiliated, is now confident that YHWH will set things right; thus, acting for the sake of this servant's peace (vv. 26-28).

The psalmist's vindication and the condemnation of the enemy lead to public acclamation of the righteousness and justice of God. The public discrediting of the wicked enables the righteous to see God at work, delighting in his servant's peace and thus they proclaim, "YHWH is great" (35:27). The psalmist will offer public testimony "YHWH, who is like you?" (35:10), he will give thanks and praise YHWH in the great congregation (35:18) and he will speak of YHWH's righteousness and praise all day long (35:28).

The psalm encourages the followers YHWH who find themselves in a life-threatening situation like the psalmist's, to pray to YHWH, asking him to execute his justice as the divine warrior, advocate, and judge. Just like the psalmist, the followers of YHWH are to not to have a vindictive spirit towards their enemies, but they are to desire YHWH's righteousness and justice to prevail with all the necessary consequences such as deliverance for God's people and punishment for the wicked. This psalm informs the readers that YHWH delights in setting things right for the suffering and the vulnerable.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Arnold A. Psalms 1-72. The New Century Bible Commentary 1. London: Butler & Tanner, 1972. [ Links ]

Bellinger Jr., William. Psalms - Reading and Studying the Book of Praises. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1990. [ Links ]

Boice, James Montgomery. Psalms 1-41. An Expositional Commentary 1. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1994. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil J. "The Junction of the Two Ways: The Structure and Theology of Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 4/3 (1991): 381-396. [ Links ]

Bratcher, Robert G. and William D. Reyburn. A Translator's Handbook on the Psalms: Helps for Translators. New York: United Bible Societies, 1991. [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles A. and Emilie G. Briggs. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Vol 1. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh : T & T Clark, 1906-1907. [ Links ]

Broyles, Craig C. Psalms. New International Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament 11. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1999. [ Links ]

Brueggemann Walter and William H. Bellinger Jr. Psalms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard J. Psalms 1-72. Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries. Nashville: Abingdon, 2002. [ Links ]

Craigie, Peter C. Psalms 1-50. Word Biblical Commentary 19. Waco: Word Books, 1983. [ Links ]

Davidson, Robert. The Vitality of Worship: A Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, Franz. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms. Vol. 1 Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980. [ Links ]

Durham, J.I. "Psalms." Pages 153-464 in The Broadman Bible Commentary. Vol. 4: Esther-Psalms. Edited by J.A. Clinton. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1971. [ Links ]

Eaton, John H. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary - with an Introduction and New Translation. London: T & T Clark, 2003. [ Links ]

Gaebelein, Arno Clemens. The Book of Psalms: A Devotional and Prophetic Commentary. New York: Our Hope Press, 1939. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. Psalms: Part 1 with an Introduction to Cultic Poetry. The Forms of the Old Testament Literature 15. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. Psalms 1-14. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament: Wisdom and Psalms. Vol. 1 Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann and Joachim Begrich. Introduction to Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel. Macon: Mercer University Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Jüngling, Hans-Winfried. Psalms 1-41. International Bible Commentary. Edited by William R. Farmer. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Kidner, Derek. Psalms 1-72: An Introduction and Commentary on Books I and II of the Psalms. Leicester: InterVarsity Press, 1973. [ Links ]

Leupold, Herbert C. Exposition of the Psalms. Grand Rapid: Baker, 1959. [ Links ]

Longman, Tremper III. How to Read the Psalms. Chicago: InterVarsity Press, 1988. [ Links ]

Mays, James L. Psalms. IBC. Louisville: John Knox Press, 1994. [ Links ]

McCann, Clinton J. "The Book of Psalms." Pages 641-1280 in 1 & 2 Maccabees; Introduction to Hebrew Poetry; Job; Psalms. Vol. 4 of The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck. Nashville: Abingdon, 1996. [ Links ]

McGrath, Alister. The NIV Bible Commentary: A One-volume Introduction to God's Word. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1984. [ Links ]

Motyer, J. Alec. "Psalms." Pages 446-547 in New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition. Edited by Donald A. Carson, Gordon J. Wenham, J. Alec Motyer and R. T. France. 3d ed. Leicester: InterVarsity Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Okorocha, Cyril. "Psalms." Pages 605-746 in Africa Bible Commentary. Edited by Tokunboh Adeyemo. Nairobi: Word Alive Publishers, 2006. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. "A Comprehensive Semiostructural Exegetical Approach." OTE 7/4 (1994): 78-83. [ Links ]

Simango, Daniel. "An Exegetical Study of Imprecatory Psalms in the Old Testament." PhD. diss. Potchefstroom: North-West University, 2012. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem A. "Psalms." Pages 1-880 in Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs. Vol. 5 of Expositor's Bible Commentary. Edited by Frank E. Gœbelein. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991. [ Links ]

Watson, Wilfred G.E. Classical Hebrew Poetry: A Guide to Its Techniques. Journal of the Study of the Old Testament. Supplement Series 26. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1986. [ Links ]

Wendland, Ernst R. Analyzing the Psalms. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1998. [ Links ]

Wilcock, Michael. The Message of Psalms 1-72. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Williams, Donald. Psalms 1-72. Mastering the Old Testament: A Book by Book Commentary by Today's Great Bible Teachers. Dallas: Word Publishing, 1986. [ Links ]

Wilson, Gerald H. Psalms Vol. 1: The NIV Application Commentary: From Biblical Text to Contemporary Life. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002. [ Links ]

Submitted: 11/10/2022

Peer-reviewed: 22/11/2022

Accepted: 20/12/2022

Dr Daniel Simango, Extra-ordinary Researcher, Unit for Reformed Theology and the development of the South African Society, North-West University. He is also the Principal and Senior OT Lecturer of the Bible Institute of South Africa, 180 Main Road, Kalk Bay, 7975. Cape Town. RSA. Email: danielsimango@outlook.com. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7651-7813

For more information on the classification of Imprecatory Psalms, see Daniel Simango, "An Exegetical Study of Imprecatory Psalms in the Old Testament" (PhD. diss., North-West University, Potchefstroom, 2012), 18.

2 The translation is mine. All quotations from Ps 35 are taken from this translation unless stated otherwise.

3 Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (electronic ed.; Stuttgart: German Bible Society, 2003), Ps 35.

4 In order to avoid any possibility of ambiguity or misunderstanding, the terms used in analysing Hebrew poetry in the present study are defined. The term stanza refers to a sub-unit within a poem or psalm whereas strophe refers to a sub-unit within a stanza. A strophe is made up of at least one colon but a tricolon comprises of a set of three cola which are parallel to each other and form a single unit. A bicolon consists of a pair of lines or cola which are parallel to each other - see Wilfred G.E. Watson, Classical Hebrew poetry (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1986), 11-15, 160-167; Willem S. Prinsloo, "A Comprehensive Semiostructural Exegetical Approach," OTE 7/4 (1994):81-82). A colon comprises of "an independent linguistic unit containing at least one verb phrase (which may also be a nominal statement) and one noun phrase" See Phil J. Botha, "The Junction of the Two Ways: The Structure and Theology of Psalm 1," OTE 4/3 (1991):385.

5 The outline of Ps 35 is based on my intra-textual analysis of the psalm. For more details, see Daniel Simango, "An Exegetical Study of Imprecatory Psalms in the Old Testament" (PhD. diss., North-West University, Potchefstroom, 2012), 31-63.

6 See J. I. Durham, "Psalms" in The Broadman Bible Commentary (Vol. 4, Esther-Psalms; ed. J.A Clinton; Nashville: Broadman Press, 1971), 240. Arnold A. Anderson, Psalms 1-72 (vol. 1 of The Book of Psalms; NCB; London: Butler & Tanner, 1972), 275; Peter C. Craigie, Psalms 1-50 (WBC; Dallas: Word Books, 1983), 285-286. Robert G. Bratcher and William D. Reyburn, A Translator's Handbook on the Psalms: Helps for Translators (New York: United Bible Societies, 1991), 328. Richard J. Clifford, Psalms 1-72 (AOTC; Nashville: Abingdon, 2002), 178; Gerald H. Wilson, Psalms Vol. 1: The NIV Application Commentary: From Biblical Text to Contemporary Life (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002), 578; John H. Eaton, The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary - with an Introduction and New Translation (London: T & T Clark, 2003), 158.

7 Craig C. Broyles, Psalms (NIBCOT 11; Peabody: Hendrickson, 1999), 170; Anderson, Psalms 1-72, 275.

8 See Charles A. Briggs and Emilie G. Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms (2 vols; ICC; Edinburgh: T & T Clark; 19061907), 1: 302-309; Arno Clemens Gaebelein, The Book of Psalms: A Devotional and Prophetic Commentary (New York: Our Hope Press,1939), 157; Anderson, Psalms 172, 275; Derek Kidner, Psalms 1-72: An Introduction and Commentary on Books I and II of the Psalms (Leicester: InterVarsity Press, 1973), 142; Franz Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Psalms (vol. 1; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 1:417; Craigie, Psalms 1-50, 285; Bratcher and Reyburn, A Translator's Handbook on the Psalms, 328; Willem A. VanGemeren, "Psalms," in Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs (vol. 5 of Expositor's Bible Commentary (ed. Frank E. Gœbelein, 12 vols.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991), 286; Alec J. Motyer, "Psalms," in New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition (ed. Donald A. Carson et al.; 4th ed.; Leicester: InterVarsity Press, 1994), 507; Robert A. Davidson, The Vitality of Worship: Commentary on the Book of Psalms (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 119; Broyles, Psalms, 170-172; Michael Wilcock, The Message of Psalms 1-72 (Leicester: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 118; Clifford, Psalms 1-72, 178; Eaton, The Psalms, 158; Cyril Okorocha, "Psalms," in Africa Bible Commentary (ed. Tokunboh Adeyemo; Nairobi: Word Alive Publishers, 2006), 606 and John Goldingay, Psalms 1-41 (vol. 1 of Psalms; BCOTWP; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007), 489.

9 See James Montgomery Boice, Psalms: An Expositional Commentary (Vol 1 of Psalms 1-41; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1994), 302; Wilson, Psalms, 578-579; Broyles, Psalms, 170.

10 See Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 1 with an Introduction to Cultic Poetry (FOTL 15; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 149-150.

11 Gunkel Hermann and Begrich Joachim, Introduction to Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel (Macon: Mercer University Press. 1998), 121; Clinton J. McCann, "The Book of Psalms," in 7 & 2 Maccabees; Introduction to Hebrew Poetry; Job; Psalms (vol. 4 of The New Interpreter's Bible; ed. Leander E. Keck; Nashville: Abingdon, 1996), 818; Donald Williams, Psalms 7-72. Mastering the Old Testament: A Book by Book Commentary by Today's Great Bible Teachers (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1986), 263 and Anderson, Psalms 7-72, 275).

12 Craigie, Psalms 7-50, 286.

13 Eaton, The Psalms, 158.

14 Davidson, The Vitality of Worship, 118-119.

15 Eaton, The Psalms, 158.

16 Craigie, Psalms 1-50, 282-286.

17 Walter Brueggemann and William H. Bellinger Jr., Psalms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 174. William Bellinger Jr., Psalms: Reading and Studying the Book of Praises (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1990), 45. Anderson, Psalms 1-72, 275, says, "The lament is the psalmist's cry when in great distress. He has nowhere to turn but to God." See Tremper Longman, III, How to Read the Psalms (Chicago: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 26. The seven elements which are associated with a lament, though not strictly in order, are: 1. Invocation; 2. Plea to God for help; 3. Complaints; 4. Confession of sin or an assertion of innocence; 5. Curse of enemies (imprecation); 6. Confidence in God's response; 7. Hymn or blessing. See Longman, III. How to Read the Psalms, 27. Wendland also observes that in these psalms, the psalmists describe their distress or the danger that they are facing but they also make a personal vow that they will always thank God for having saved them or they will bring sacrifices of thanksgiving to the temple; cf. Ernst R. Wendland, Analyzing the Psalms (Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1998), 33-34.

18 Craigie, Psalms 1-50, 286.

19 Gerstenberger, Psalms, 193.

20 James L. Mays, Psalms (IBC; Louisville: John Knox Press, 1994), 154.

21 McCann, "The Book of Psalms," 819.

22 Herbert. C. Leupold, Exposition of the Psalms (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1959), 284; Bratcher and Reyburn, Translator's Handbook on the Psalms, 1114; Goldingay, Psalms 1-41, 490; Gaebelein, The Book of Psalms, 156.

23 McCann, "The Book of Psalms," 657.

24 Durham, "Psalms," 158; Broyles, Psalms, 27-28.

25 McCann, "The Book of Psalms," 657.

26 Bratcher and Reyburn, Translator's Handbook on the Psalms, 14; Wilson, Psalms, 89.

27 Ibid.

28 Hans-Winfried Jüngling, "Psalms 1-41," in International Bible Commentary (ed. William R. Farmer; Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1998), 783-784.

29 Wilson, Psalms, 90.

30 Jüngling, "Psalms 1-41," 783.

31 Jüngling, "Psalms 1-41," 814; 820)

32 Alister McGrath, The NIV Bible Commentary: A One-volume Introduction to God's Word (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1984), 154.

33 Clifford, Psalms 1-72, 180-181.