Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.35 n.2 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2022/v35n2a3

ARTILCES

Humans and Non-humans as נפש ח;ה and Ntu-beings: Ecological Appraisal of Gen 2:7 and 19 in Dialogue with African-Bantu Indigenous Cosmology1

Jonathan Kivatsi Kavusa

University of Pretoria/ Alexander Von Humboldt-Alumnus

ABSTRACT

The Hebrew text of Gen 2:7, 19 describes both humans and animals as nephesh hayya' (living being). However, a large number of contemporary influential Bible translations render this expression differently for humans and animals. It is translated living being for humans (v.7), but living thing/creature for animals (v.19). This is however not justified by any clue in the text, which views humans and non-humans as both adamah-beings and nephesh hayyah. Likewise, African-Bantu cosmology depicts humans and non-humans as ntu-beings (muntu: human being; kintu: non-human being; hantu: place and time; kuntu: means or approach).The root ntu in the word kuntu implies that the way muntu (human being) interacts with other beings (kintu, hantu) must be informed by a vision of nature not as a "thing" but a living being. In addition to elements of socio-historical approaches and African-Bantu indigenous cosmology, this study makes uses of a hermeneutics of suspicion and the Earth Bible principle of mutual custodianship to retrieve ecological wisdom of Gen 2 in the African context.

Keywords: nephesh hayya, adam/adamah, Genesis 2, African-Bantu indigenous cosmology, ecological hermeneutics, living being/soul/creature, humans and animals

A INTRODUCTION

It is often alleged that human imperialism has led scholars to deny "intelligence" from faunal beings and that animals have no real intelligence but "instinct." However, Darwin showed that animals cannot be termed as only instinctive beings but beings that also possess the ability to "reason" as there "is no fundamental difference between man (sic) and the higher mammals in their mental faculties."2 Thus, the word "instinct" is hardly used by zoologists who rather speak of animal intelligence or thinking.3 According to Darwin, the difference in mind between humans and higher animals is only a difference of "degree and not of kind."4

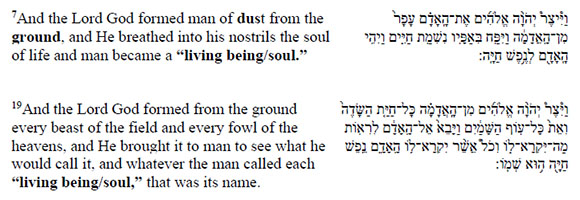

Perhaps it is from the above perspective that Gen 2:7 and 19 use the same Hebrew word for both humans and animals:  (nephesh hayyah, living being). However, it was a surprise to discover that notable English and German Bibles translated the expression nephesh hayyah differently for human beings and non-human beings. I cannot cite all of them but I will refer to the most influential Bible versions. For example, the King James Version (KJV) uses "living soul" for humans (v.7) but "living creature" for animals (v.19). The New Living Translation simply blurred the expression by the use of the pronoun "them," as it renders verse 19 as "He (God) brought them to the man to see what he would call them." The New American Standard Bible (NASB) renders

(nephesh hayyah, living being). However, it was a surprise to discover that notable English and German Bibles translated the expression nephesh hayyah differently for human beings and non-human beings. I cannot cite all of them but I will refer to the most influential Bible versions. For example, the King James Version (KJV) uses "living soul" for humans (v.7) but "living creature" for animals (v.19). The New Living Translation simply blurred the expression by the use of the pronoun "them," as it renders verse 19 as "He (God) brought them to the man to see what he would call them." The New American Standard Bible (NASB) renders  as "living person" for humans in verse 7 but as "living creature" for animals in verse 19. The English Standard Version (ESV), the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) and the New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (NRSVCE) all render it as "living being" for humans (v.7) and "living creature" for animals (v.19). The word "creature" implies a "thing" different from humans who are "real living beings."

as "living person" for humans in verse 7 but as "living creature" for animals in verse 19. The English Standard Version (ESV), the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) and the New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (NRSVCE) all render it as "living being" for humans (v.7) and "living creature" for animals (v.19). The word "creature" implies a "thing" different from humans who are "real living beings."

Most of German versions also follow a similar pattern, as they simply used the word Tier (animal) in verse 19 instead of translating the word nephesh hayyah as „lebendiges Wesen" (living soul) as for humans in verse 7 (Luther Bibel Rediviert 2017). Verse 19 of the German Bible reads: „Denn wie der Mensch jedes Tier nennen würde, so sollte es heißen" (and whatever Adam called every animal, that was its name). Instead of translating the verse as „Denn wie der Mensch jedes lebendiges Wesen nennen würde" (whatever name Adam gave to every living being), the Luther Bible replaced the expression „lebediges Wesen" (living being) of verse 19 with „jedes Tier" (every animal).

The first reference (to human) is rendered „ lebendiges Wesen" (living being) while the second is simply Tierart (animal species, i.e. different from humans). The Luther Bible version of 1912 added the word lebendig (living) in front of the word Tier (animal) to read „ denn der wie Mensch allerlei lebendige Tiere nennen würde, so sollten sie heißen" (whatever name Adam gave to every living animal, that was its name). Thus, the underlying idea would be to emphasise human distinctness from animals.

Clearly, the Luther Bible and its revisions fail to translate nephesh hayyah identically for both humans and animals. Luther justified his translation with the claim that only foolish translators can do word-for-word translations since the task of translation is not a direct translation of the original words but the expression of the idea behind the original language in the receptor language.5 Thus, Luther rendered the expression nephesh hayyah in verse 19 with its referent (animal). While his translation of verse 19 is apparently correct, it, however, erodes the fundamental existential ideal of commonality between humans and animals conveyed in the expression nephesh hayyah for both. It reinforces the status of humans as different from other species. This is what German eco-thelogians call „das arrongante Anthropozentrismus" that tries to emphasise human uniqueness and suppress their commonality with other species:

Je mehr das Besondere des Menschen in seiner Rationalität gesehen wird, desto größer ist die Distanz zu den nichtmenshlichen Tieren und desto eher werden deren Empfindungen relativiert.6

Aware of the translation problem of Gen 2:19, the Elberfelder and Zürcher German Bibles decided to retain the idea in the Hebrew text by rendering verse 19 as „und genau so, wie der Mensch sie, die lebenden Wesen, nennen würde (whatever name Adam gave to the living beings...). Hence, Germany's Tierschutzgesetz (Animal Welfare Act) (1972) attempted to correct this anthropocentric arrogance when it used the term Mitgeschöpf" (co-creature) for animals to re-affirm the intrinsic connectdness between humans and animals (§1 Absatz 1 Satz 1 TierSchG).7

No doubt, Martin Luther's 1534 Bible and the KJV remain two of the most influential Christian documents. Graham describes both Bibles as "the two most influential documents that emerged from the Reformation period,"8 both having an extensive and profound effect on the languages into which they were translated and the lifestyle of the believer. They have shaped and continue to shape the piety, worldviews and attitudes of Christians who turn to them for meditation, piety and life in general. Their translation of Gen 2:19, thus, matters a lot.

It is not clear enough why many English and German Bibles translated the words nephesh hayyah differently for humans and animals. Some would think that this is due to our sub-conscious as humans, trying our best to consider ourselves as "superior beings" and to distance ourselves from animals in order to justify our mastery over them.9

These renderings are different from the Hebrew text of Gen 2 and indigenous African10 cosmologies. In fact, besides being both nephesh hayya, humans and animals are all said to be "formed from the ground" (Gen 2:7, 19). The only superiority of humans over animals is cited in verse 19 as the ability of humans "to name animals."11However, the same animals are first proposed as helper for Adam, even though Adam did not find one that was right for him (v. 19). We know that the syntax of verse 20 that וּלְאָדָָ֕ם לֹֽ א־מָצָָ֥א עֵ֖זֶר כְנֶגְדֹֽוֹ (and Adam found not a convenient helper) aims to emphasise that the woman is the best helper.12

African, especially the Bantu, indigenous knowledge, views every existence as a living being and as having a living soul. In Africa, every existence is semantically constructed with the existential root NTU,13 which is a "vital force" common to all beings. Muntu means human being; kintu stands for non-human beings such as fauna, flora or mineral; hantu designates place or time while kuntu embodies the means, approach or relationship between the first three.14 Ntu is what is common to muntu, kintu, hantu and kuntu equally as forces. The root ntu in the word kuntu implies that even the way humans (plural: Bantu) interact with other beings (kintu, hantu) must be informed by a vision of nature not as an "object" but as fellows.15

In this regard, although the Bible version in my mother tongue, Kinande, is based on the KJV, the words used for humans and animals carry existential commonality in Gen 2:7 and 2:19. The translations read as follows:

v.7....Omundu16 oyo mwabya omundu oyuliho (v.2) (Adam became a "living Adam/being").

v.19 Neryo obuli kindu kyahangikawa ekiriho, erina eryo alukalyo mulyabya lina lyako (and every living creature got the name that Adam gave to it).

Although the Kinande translation follows the KJV, its worldview conveys the ideal of the Hebrew text where Adam (mundu) and animal (kindu) are thought as nephesh hayyah (living beings). Mundu and kindu are all "ndu (or ntu) existences": they are both living beings in the Bantu cosmology.17

Therefore, the key question of this article is to investigate whether the dialogue between Gen 2:7,19 and Bantu indigenous view of "relatedness of all living beings" may offer ecological wisdom against current materialistic worldview. I will use insights from biblical socio-historical approaches coupled with ecological hermeneutics of the Earth Bible project with its hermeneutics of suspicion and one of its six principles namely the principle of mutual custodianship, which states that:.

Earth is a balanced and diverse domain where responsible custodians can function as partners, rather than rulers, to sustain a balanced and diverse Earth community.18

Based on the hermeneutics of suspicion, we assume that the text is likely to be inherently anthropocentric and/or has always been read or translated from an anthropocentric viewpoint. The artificial translation of the expression nephesh hayya as "living thing" for animals (v.19) would confirm this suspicion. Additionally, this article will make use of elements of African-Bantu indigenous knowledge (taboos, proverbs or wisdom) to facilitate the ecological interpretation in the African context.

B AFRICAN-BANTU PEOPLE AND THEIR COSMOLOGY

The Bantu people originated near the border of Nigeria and Cameroon and expanded through migrations to the rainforests of central Africa, the savannah of East Africa and a large part of Sub-Saharan Africa 4000 years ago.19 The cosmology of African-Bantu people is transmitted through their language systems.20 Over 310 million Africans speak a Bantu language.21 The Bantu language group is among the world's most diverse, comprising more than 500 languages, which all share linguistic features (some 250 are mutually intelligible) rooted from a common ancestral language.22

The affinity of the languages is illustrated by the root word ntu, epitomising the existential commonality of all living beings. Ntu is rendered differently in the Bantu languages but refers to the same ideal namely "force vitale" as noted by Placid Tempels.23 Ntu is rendered nthu in Chichewa in Malawi and tho in Setswana spoken in South Africa and Botswana and Sesotho, which is spoken in Lesotho and South Africa.24 It is ntu for the Banyarwanda of Rwanda, the Tonga of Zambia as well as the Zulu and Xhosa of South Africa, while the Kikuyu of Kenya, the Nande of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Konzo of Uganda all use the term ndu, which is nto or ndo for the Meru of Kenya.

This study does not cite all the Bantu languages but selects from some of them cosmological wisdom that relates to ntu in all spheres of existence (land, animals, time, water, human, flora, ways of living and interacting with people and nature...).

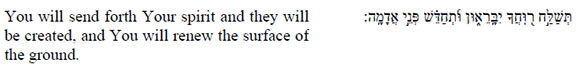

C MY TRANSLATION OF GEN 2:7, 19

D HUMANS AND ANIMALS AS "SIBLINGS"

1 Sourced from Adamah

Verse 7 and 19 say humans and animals are formed "out of the ground" (מן־הָֹֽ אדָ מה) in order to convey their custodianship. Both humans and animals are made "naked" from the dust and they are not ashamed of their condition as they meet in verse 19. In fact, they view themselves as "all part of one naked family derived from a common Adamah."25

However, the Hebrew text says that humans are made from the "dust of the ground/soil"  (v.7) while animals, trees and birds are made only "from the ground" מן־האדמה (v.19). The omission of the word עפר (dust) in verse 19 does not alter the common origin of all living beings. Commentaries say that the conjuction of the verb יצר(to form) with the noun עפר (dust) in verse 7 only „ bezeichnet das handwerkliche und künstleriche Gestalten. "26 The idea is only to describe God doing "the work of a potter" (see also Job 10:9). Description of God as a potter is widespread in ancient near East, for example, in the Egyptian art of god-Knum or the Greek myth of Prometheus where humans are made out of the clay or the earth.27 The three Mesopotamian epics of Enuma Elish, Gilgamesh and Atrahasis all depict human creation as derivation from the clay.28 That is why Eccl 3:20 reads עפר as the common origin of both humans and animals: at death both living beings return to their place of origin, עפר(dust).

(v.7) while animals, trees and birds are made only "from the ground" מן־האדמה (v.19). The omission of the word עפר (dust) in verse 19 does not alter the common origin of all living beings. Commentaries say that the conjuction of the verb יצר(to form) with the noun עפר (dust) in verse 7 only „ bezeichnet das handwerkliche und künstleriche Gestalten. "26 The idea is only to describe God doing "the work of a potter" (see also Job 10:9). Description of God as a potter is widespread in ancient near East, for example, in the Egyptian art of god-Knum or the Greek myth of Prometheus where humans are made out of the clay or the earth.27 The three Mesopotamian epics of Enuma Elish, Gilgamesh and Atrahasis all depict human creation as derivation from the clay.28 That is why Eccl 3:20 reads עפר as the common origin of both humans and animals: at death both living beings return to their place of origin, עפר(dust).

Some scholars argue that עפר (dust) recalls pre-royal status based on the occurrence of the word in royal texts (1 Kgs 16:2; 1 Sam 2:8 or Ps 113:7-8).29 In their view, humans are "formed from the dust to be in control of a garden."30This interpretation is not convincing since the word עפר also occurs in texts with negative connotations. עפר is the diet for the cursed serpent in Gen 3:14 while the defeated enemies are to lick עפר in Ps 72:9. Besides, the word עפר is both Adam's present nature and destination (כֹֽי־עָפָָ֣ר אַָ֔תָה וְאֶל־עָפֵָ֖ר תָשֹֽוּב ) (for dust you are and to dust you will return).

Thus, it is thought that the depiction of God fashioning humans from עפרtranslates both human „Herrlichkeit und Bedeutungslosigkeit"31 or "glory and insignificance."32 Adam is the only creature, which is said to be explicitly made as a work of pottery before being animated by God.33 Adam has a unique relationship with the potter, God. Nonetheless, Adam is dust and adamah is „ seine Wiege, seine Heimat, sein Grab" 34 just as it is also for other living beings.35

Adamah in both verses 7 and 19 of Gen 2 emphasises the ontological commonality between humans and animals. Like Adam, the living beings who will be later selected as potential partners for Adam are made from adamah in order to highlight the common origin and hence are potential partners.36 Thus, this earthiness of humans signifies a kinship with the earth/ground (adamah) itself and with other earthly beings, plants and animals. It is remarkable that the diverse trees of the garden also emerge from adamah underlining the ideal that "humans and forests have a common origin and a continuing relationship."37

Adamah is God's partner in the creation of all life on Earth. Adamah is both the source of Adam and the reason for Adam's existence-to till and serve adamah of Eden (Gen 2:15). Davis demonstrated the ambiguity of the Hebrew word שמר which literally means "to keep" but in the sense of "observing," "to learn from" and "to respect" the limits of the Garden.38 State differently, Adam is made from the land to care for the land, to learn from the land and to respect the land, "the fertile ground and source of all earth beings."39

In the same vein, African indigenous cultures highlight the bond between human beings and adamah (the land) through Proverbs and taboos. The Akan saying "Tumi nyinaa ne asase" (All power arises from land) reflects both cultural values and communal environmental lifestyle of Akan in relation to nature. The Akan consider asase (land) as the physical and feminine aspect of God that made human creation possible. Hence, the Akan refer to asase as Yaa (among the Twi-speaking Akan) or Afua (among the Fante-speaking Akan), highlighting the goddess (divine) aspect of the land.40

The Nande and Konzo41 have strict regulations about the land. They strongly affirm that "ekitaka sikyeghulivawd" (the land cannot be sold). The reason is that "ekitaka yo ngeve eyekighandd" (the land is the soul of the community). As in case of Israel, selling the land means selling his soul or his existence. Thus, in the Holiness Code (Lev 17-26), the land is not merely "a stage on which the drama of the covenant unfolds" but is itself an active agent partaking "in a web of mutually obligated covenant relationships with YHWH and with the people."42 In Hos 4:3, the land mourns or dries up (אבל) as a result of human misbehaviours upon it.43

It is clear that the after-Garden situation is a painful relationship between all adamah beings: humans, non-humans and adamah itself (Gen 3). Adam will get his food from adamah in pain. Instead of being pleasant (Gen 2:9), adamah is a cursed and frustrated ground producing thistles and thorns (Gen 3:17-18). Furthermore, hostility is now real between adamah-beings (Gen 3:8-24)-human offspring will crush the head of the snake (animal kingdom) and the snake will bite his heel (Gen 3:15).

2 Humans and animals as nephesh hayya

The Hebrew expression nephesh hayya is translated differently for animals and Adam in most of our Bibles. Many influential Bible versions translate the expression nephesh hayya for humans (v.7) as "living being/soul" but "living thing/creature" for animals (v.19) (KJV, The Complete Jewish Bible, the NASB, NRSV). Martin Luther Bible just replaced the nephesh hayyah of verse 19 by "animal," as he claimed that what matters in the translation is not a word-for-word translation but expressesthe sense of biblical text in the speech of the reader.44

The problem is that omitting nephesh hayyah from the text or translating it differently for humans and animals suppresses the fundamental commonality between both living beings. This translation creates a significant difference between people and animals by calling the former a "living being" and the latter a "living creature."45 In the process, the reader of the Bible unconsciously accentuates more his/her difference with other species than her/his kinship with them. Animals are merely "living things/objects" while humans are true "living beings."

However, the use of nephesh hayyah for both humans and animals in the Hebrew text implies that we share the same ontological existence; we are relatives and custodians. The Hebrew text makes people and animals "siblings" in contrast to to Gen 1:25-28 where only humans are made in God's image while the rest are generated from the earth or waters. Genesis 2:7 shows that God breathed neshamah (breath of life) only into human nostrils. This detail is missing in verse 19 in the creation of animals. The action of ,,Mund-zu-Nase-Beatmung" (mouth to nostrils animation) means that humans have a special relationship with God.46

Although the term neshamah is missing in verse 19, it is said that animals are nephesh hayyah and that means, „dass das Bezeichnete eine lebende Kehle, ein Lebewesen, eine lebendige Seel ist."47 In other words, the omission of the word neshamah in verse 19 does not mean that animals do not have the neshamah. This is confirmed by the statement in Gen 7:22 that all which had neshamah in its nostrils died in the flood:

Everything on the dry land in whose nostrils was the breath of life died.

God breathed neshamah into human nostrils and Adam became a nephesh hayyah (v.7) while animals are only said to be nephesh hayyah-beings without showing how God acted to make them nephesh hayyah-beings (v.19). It seems then that the difference between humans and animals is only in how they were created and not in what they are made of. Qoheleth shows that human breath and that of animal are identical: "Who knows whether the breath (ruach) of humans ascends above and the breath (ruach) of animals descends down?" (Eccl 3:21).

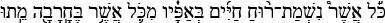

Hiebert convincingly demonstrates that neshamah and ruach are interchangeably used (Isa 42:5; Job 27:3) often to mean breath that animates all life.48 Neshamah is the breath of life of all living beings in Gen 7:22, which perished in the flood. Psalm 104:30 states that Adam is brought to life by the ruach of God. The divine ruach is here equated with neshamah giving life to all creatures and "the face of the ground":

This ruach it is directly connected to God and makes life possible in the cosmos. Some translation render neshamah of Gen 2 as soul but it should be understood not in the sense of the dualistic view of body and soul.49 Adam, like other living beings, is nephesh hayyah: „er teilt mit ihnen als grundlegende Gemeinsamkeit Leben und Lebendigkeit,"50 in addition to his special relationship with the creator as noted above. The nephesh refers to a living being as an entity, an integrated living being, which „ stellt ein gemeisames Charakteristikum von Tieren und Menchen innerhalb des Alten Testaments dar. "51

3 Naming animals as an act of acceptance (v.19)

Verse 19 shows that God brought animals to Adam so that he could name them. It is said that "to name" or "to know the name" of a person or an animal in the ancient Near East implied having power and control over them.52 The nominal form of the statement, "that was its name," implies the acquired authority of humans in the sense that „Gott keine Korrektur vornimmt."53 God would not dare correct the name Adam allocated to a given animal. By naming animals, humans act as the ruler of the animal kingdoms. If so, what would have been the meaning of this rule?

First, we should understand the ideal of kingship in Israel. The book of Deuteronomy subverts all ordinary notions of kingship in the ancient Near East (17:14-20). Israel's king must not be a foreigner but a kin who is set over his fellows but remains a kin. In this way, the king cannot exalt himself over his subjects. His rule becomes tyranny when he forgets that the horizontal relationship of brother/sisterhood is primary and that kingship secondary.54 Similarly, human rule over other beings will be despotic if we forget our ontological commonality with other creatures.

In this way, other scholars perceive the "naming of animals" not as an act of dominion but an act of acceptance and celebration in the community of brethren. In some texts, "to name is to know and to connect personally and communally."55 This is evident in Ruth 4:13-17 in which Ruth handed her baby over to Naomi and the women of the village came to name the child as a sign that the child is accepted as a "new" member of the community. Humans and non-humans would relate to one another not as ruler and vassal but as custodians and partners in the earth community.

This view is the same in African cosmology where names are not simply labels but the expression of communal values, hope or struggles. To name a person is to insert him into the worldview of the community, with its multifarious visible and invisible realities.56 That is why, among the Igbo-Bantu of Nigeria, the naming of a child is not a private but a communal task. It is always done in the presence of relatives, friends and residents of the village. The significance of this public naming ritual is to highlight the importance of unity and of abstention from individualistic actions that might lead to social chaos.57

4 Animals as first  to Adam

to Adam

God brought the animals to Adam to name them in the sense of observing whether Adam would accept the animals as partners. Animals are presented as potential partners or helpers (Iוּלְאָדָָ֕ם לֹֽ א־מָצָָ֥א עֵ֖זֶר כְנֶגְדֹֽוֹ ) for Adam even though Adam did not find them the best partner (Gen 2:19). This verse does not imply that animals are lesser beings or lack intrinsic value but serves as a literary link to show the importance of the creation of the woman, who is described as the best partner  ) (v.20).

) (v.20).

The word  (helper) is often used to refer to God helping needy peoples/humans (Deut 33:7; Ps 20:5). The word then does not suggest weakness or even subordination of any kind but partnership. According to Habel, the role of animals apparently consists of helping to preserve the ecosystem of Eden.58

(helper) is often used to refer to God helping needy peoples/humans (Deut 33:7; Ps 20:5). The word then does not suggest weakness or even subordination of any kind but partnership. According to Habel, the role of animals apparently consists of helping to preserve the ecosystem of Eden.58

E HUMANS AND ANIMALS IN OTHER TEXTS

The Bible describes animals with two main terminologies- . The latter refers to uncontrollable and untamed animals (see Job 39 and Ps 105). They live on the land which is out of the dominion of human beings. The word

. The latter refers to uncontrollable and untamed animals (see Job 39 and Ps 105). They live on the land which is out of the dominion of human beings. The word  refers to all kinds of animals (Gen 8:17; 9:16)-from terrestial animals to birds ofthe skies and aquatic animals (Gen 1:28; 2:19). The word

refers to all kinds of animals (Gen 8:17; 9:16)-from terrestial animals to birds ofthe skies and aquatic animals (Gen 1:28; 2:19). The word  „meint soviel wie Lebendes, Lebendiges, Lebewesen "59 and relates mostly to animals, which can be domesticated by humans beings (Lev 5:2; 1 Sam 17:46; Ps 148:10).

„meint soviel wie Lebendes, Lebendiges, Lebewesen "59 and relates mostly to animals, which can be domesticated by humans beings (Lev 5:2; 1 Sam 17:46; Ps 148:10).

In Gen 1, the terrestial animals and humans are created on the same day, the day sixth and they are commanded to feed on floral product. The text refers to them four times as nephesh hayyah (Gen 1:20, 21, 24, 30) to highlight their similarity with human beings. This is emphasised in Gen 12:15 where  ] (all beings) are simply not assimilated to the

] (all beings) are simply not assimilated to the  = (and all the things/possessions) of Abraham. This reinforces the status of animals as living beings close to human beings.

= (and all the things/possessions) of Abraham. This reinforces the status of animals as living beings close to human beings.

Besides, „bevor die Tierwelt also in eine Beziehung zur Menschheit gesetzt wird, tritt sie in Relation zu ihrem Schöpfergott auf."60 Although humans are the only beings created in God's image to rule over the earth and animals, animals were not created as food for humans but they were to share the earth with them. The root רדה and כבש for human dominion (Gen 1:28) should be read not only in relationship with ancient Near Eastern kingship ideology,61 but more with verses 29-30 where the "unqualified power of humans over animals and earth is then circumscribed within the vegetarian limit that prevents it from violence."62 Additionally, when humans are allowed to kill animals (Gen 9:4), they are forbidden to eat their blood since blood is life. In other words, humans should never threaten the life of faunal species.

In the praise song of Ps 104, the text shows almost no difference between human and animal beings. The world of Ps 104 is comparable to the living space of Gen 1 where:

Menschen und andere Tiere erweisen sich als abhängige Geschöpfe Gottes, der für sie alle sorgt und ihnen je eigene Lebensbereiche - etwa Grasland für Schafe und Ziegen, Bäume für die Vögel zum Nisten, Berge den Steinböcken und Klippschliefern als Zuflucht - zugeteilt... In diesem harmonischen Ökosystem respektieren alle unterschiedlichen Lebewesen die ihnen zugewiesenen Lebensräume und [Lebens]zeiten.63

In Ps 148:1-14, animals and humans are depicted equally as members of the cosmic choir. Humans have only a kind of ministerial function within the community of "all his hosts" (v.2). This expression "all his hosts" echoes Gen 1:31 where it is used to name the created beings of Gen 1. Animals, humans, angels, waters and the earth are all equally called to praise God. In Num22:22, the donkey of Balaam can see the danger before him and talk. The donkey helps Balaam (human) to avoid death as it recognises the messenger of YHWH. The donkey talks to Balaam recalling their partnership before this incident (Num 22:29-30).

The relationship betwen the Israelites and the faunal world was so intimate that many names of the people of Bible are constructed after animal names. Caleb means cow while the name Deborah means bee and Jonas a pigeon. As in the Bible, Africans adopt animals to highlight the close relationship between the community and the animals. Totemic nicknaming epitomises people's identification with particular ability and characteritics of that animal.64

F AFRICAN INDIGENOUS SOCIETIES

In the Garden of Eden there is no apparent alienation or dualistic division between humans and animals- they are nephesh hayyah beings; they are kin and companions in the forest.65 This kinship ideal with other "living beings" is common in African indigenous societies in which specific animals share a common spirit with humans and with particular places. An African indigenous community is therefore not limited to human sphere but includes other living beings, the unborn and ancestors.

John Mbiti's famous adage, "Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu" (I am because we are), extends the community beyond anthropocentric domain by including non-human beings (animals, plants, places, rivers), the unborn and the supernatural into the moral universe66. African-Bantu people view all life as ntu-beings.67

Subsequently, many African languages do not traditionally use the verb to "have" but "to be" when speaking about human relationship with the land. The Banyarwanda people of Rwanda say "Ndi n'ubuthaka" (I am with the land) instead of "mfite ubuthaka." The Chichewa people of Malawi say "Ndili ndi Nthaka" (I am with the land). The Tswana (Botswana and South Africa) say "Ke na le lefatshe" (I am with the land) just as one would respond to another human being in terms of "ke na le wena" (I am with you). This ontological view implies that both the possessor and the dominated stand "side by side in a relationship of interdependence from and equality with one another."68

Many African people viewed themselves as fundamentally connected to the land to the point that some families adopted the name of their land as their "family name" (Anselme Siku, lecturer at Ulpgl-Butembo, interviewed April 2021). The dignity of the land is that of the people living on it and whoever defiles it, threatens the survival of the community. The land encompasses ecological, cultural, cosmological and spiritual dimensions and traditional African land tenure was not based on ownership or commodity but on communal existence and identity.69

Therefore, all present undertakings related to resource use or community life must ensure that the next generations will not have trouble to meet their needs. The Gikuyu people of Kenya say, "Rigita thi wega; ndwaheiruio ni aciari; ni ngombo uhetwo ni ciana ciaku" (You must treat the earth/land well. It was not given to you by your parents; it is loaned to you by your children). The idea is that present generations are mere tenants of the land. Thus, members of the society are expected to live and act in a way that promotes the welfare of present and future members of the community. That is why taboos were instituted in African societies to set limits to human actions and attitudes for the wellbeing of the whole. As far as Africans are concerned, the wellbeing of all (community) takes precedence over individual interest. In this way, it is the community that defined the person as person (muntu), since the word muntu also denotes the idea of excellence, of plenitude of force and the savoir-vivre of abiding by the taboos and rules of the community.70

Therefore, contrary to the Western definition of a person in terms of rationality, personhood is not viewed as acquired de facto but is attained through participation in the social life of the community. As a clear antithesis to Descartes' statement "Cogito ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am), in Africa, it is rather "Participo ergo sum" (I participate, therefore I am).71 Through participation in community life, one evolves from the status of early childhood to that of muntu marked by ethical maturity.

The separation of subject and object is not possible in Africa because of the idea of inner connection and participation between human beings and the world.72 From this arises a human-nature relationship, which is clearly different from the Western drive for dominion based on Gen 1:26-28 and which has characterised our time of nature manipulation. African worldview does not allow manipulation but custodianship for the balance of all ntu-beings, the equivalent for all the nephesh hayyah of Gen 2.

G CHURCH INTERPRETATIONS OF COSMIC COMMUNITY

1 The Roman Catholic "Laudato Si"

The Encyclical of Pope Francis "Laudato Si" can be regarded as the Magna Charta of an inclusive eco-theology openly criticising suicidal anthropocentric exploitation of nature. According to the Pope, "the most extraordinary scientific advances, the most amazing technical abilities, the most astonishing economic growth, unless they are accompanied by authentic social and moral progress, will definitively turn againstvman."73

The letter starts by recalling the words of Saint Francis of Assis, "the patron saint of all who study and work in the area of ecology."74 Francis communed with all creation, even preaching to the flowers, inviting them to praise the Lord, as if they were endowed with reason. In this way, Francis depicted nature not as an object but a sister with whom we share our life and a beautiful mother who opens her arms to embrace us.75

Therefore, with the reference to Saint Francis, Pope Francis VI calls for a radical shift away from worldviews that have brought humans to see themselves as lord and master of nature. Creation abuse starts when we, humans, no longer speak the language of fraternity in our relationship with the world, as depicted in Gen 2:19. Our attitudes become that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs.76

For Pope Francis VI, our irresponsible use and abuse of sister/mother earth illustrates the arrogance in our hearts, wounded by sin (Gen 3). This is reflected in the symptoms of rudeness (pollution) evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life. Consequently, adamah "groans in travail" (Rom 8:22), as she is burdened and laid waste. We forget that we are ourselves adamah (Gen 2:7) and that the earth (adamah) is our common home.77

The Encyclical notes that authentic human development should have a moral character. It must accord full respect not only to the human person but also to the world around us and take into account the nature of each being and of its mutual connection in an ordered system. In this way, the Pope depicts climate change as a global issue with grave implications for every sphere of life-environmental, social, economic and political-and for the distribution of goods.

Therefore, the Pope draws all Christians into a dialogue with every person (people of other religions and all human beings) to seek a sustainable and integral development of our common home. Laudato Si is a historical call for a radical ecological Reformation of Christianity and beyond. The Pope calls for contextual approaches to the care of creation and the cooperation of all human family, each according to his/her own culture, experience and talents in order to reaffirm our brother/sisterhood with the earth and its inhabitants.78 Our destiny is interconnected.

2 World Council of Churches and cosmic community

The World Council of Churches (WCC) reaffirmed our dependence to adamah through its multiple voices on sustainability and eco-justice. In its general assembly that was held in Nairobi 1957, the WCC noted that a sustainable society should be regarded as a place where each individual can feel secure that his quality of life will be maintained or improved. In the seven years that followed, the Council organised worldwide meetings to discuss the meaning of sustainability. The WCC presented sustainability in terms of four prerequisites:

First, social stability cannot be obtained without an equitable distribution of what is in scarce supply and common opportunity to participate in social decisions. Second, a robust global society will not be sustainable unless the need for food is at any time well below the global capacity to supply it, and unless the emissions of pollutants are well below the capacity of the ecosystem to absorb them. Third, the new social organization will be sustainable only as long as the rate of use of non-renewable resources does not outrun the increase in resources made available through technological innovation. Finally, a sustainable society requires a level of human activity which is not adversely influenced by the never ending, large and frequent natural variations in global climate.79

The final prerequisite for sustainability relates to development that is in harmony with normal function of nature. The WCC Assembly in Vancouver (1983) added the topic of peace to this definition. The innovation affirmed the inseparable relatedness of the dynamic concepts of justice, peace and integrity of creation. This ideal was advanced in 1990 during the Seoul Convocation on Justice, Peace and Integration of Creation. The Seoul Convocation invited churches to resist the claim that views anything in creation as merely a resource for human exploitation. Therefore, the affirmation No VII states:

We will resist species extinction for human benefit; consumerism and harmful mass production; pollution of land, air and waters; all human activities which are now leading to probable rapid climate change; and policies and plans which contribute to the disintegration of creation.80

In 2005, the WCC launched the document, "Alternative Globalisation Addressing Peoples and Earth" (AGAPE- document), which was the background for the "AGAPE call" issued by the 9th WCC Assembly in Porto Alegre in February 2006. It depicts the economic practices of neo-liberalism and globalisation as economy of death, as it commoditises everything. The document states:

Centred on capital, neoliberalism transforms everything and everyone into a commodity for sale at a price. Having made competition the dominant ethos, it throws individual against individual, enterprise against enterprise, race against race, and country against country. Its concern with material wealth above human dignity dehumanises the human being and sacrifices life for greed. It is an economy of death.81

Thus, in 2009, a significant official declaration on eco-justice and ecological debt was released, reiterating that "the era of unlimited consumption has reached its limits." This statement calls for new understandings of nature not merely as an object of exploitation but a subject without which human existence is impossible. The statement affirms "a deep moral obligation to promote ecological justice by addressing our debts to peoples most affected by ecological destruction and to the earth itself."82

In this regard, the WCC invites the signatories to uphold behaviours that are compatible with the harmony of the natural order in reference to the traditional societies. The WCC recommends that its member churches:

Learn from the leadership of Indigenous Peoples, women, peasant and forest communities who point to alternative ways of thinking and living within creation, especially as these societies often emphasize the value of relationships, of caring and sharing, as well as practice traditional, ecologically respectful forms of production and consumption.83

The WCC further expressed the need to strengthen the on-going efforts of traditional ecological worldviews aiming to re-design alternative growth plans in order to avoid more ecological damages. This includes, for instance, supporting community-based sustainable economic initiatives such as producer cooperatives, community land trusts and bio-regional food distribution.

H CONCLUSION

Genesis 2 and African indigenous traditions reaffirm our common ontological existence with non-humans. Unless we understand this ideal, we will continue to act as mercenaries and aliens to other species. Humans and non-human members of the planet (floral and faunal beings) are kin and custodians according to Gen 2:7 and 2:19 and African-Bantu cosmology.

Ntu-being cosmology can serve as a vehicle to facilitate the appropriation of the text of Gen 2:7-19 to address the materialistic view of nature in modern Africa. Both Bantu cosmology of ntu-beings and the Hebrew idea of nephesh hayya for humans and animals show extent to which this text can be helpful in contemporary Africa at this time of ecological impasse. It would help people to re-imagine their relationship with fellow ntu-beings since any disruption will affect all the ntu or nephesh hayya beings as in Gen 3.

REFERENCES

- Bauckham, Richard J. Living with Other Creatures: Green Exegesis and Theology. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2011. [ Links ]

- Bergams, Banande L. Les Wanande: Les Baswagha-Aperçu Historique. Tome 1. Butembo: Editions A.B.B (Assomption-Butembo-Beni), 1970. [ Links ]

- Brueggemann, Walter. "From Dust to Kingship." Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaf 84/1 (1972): 1-18. [ Links ]

- Bundesministerieum für Ernährung Landwirschfat und Verbraucherschutz. Tierschutzgesetz in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 18. Mai 2006 (BGBl. I S. 1206, 1313), dasvzuletzt durch Artikel 105 des Gesetzes vom 10. August 2021 (BGBl. I S. 3436) geändert worden ist, 1972. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschg/TierSchG.pdf. [ Links ]

- Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. With an introduction by John T. Bonner and Robert M. May. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. [ Links ]

- Davis, Ellen F. Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture: An Agrarian Reading of the Bible. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

- Dube, Musa W. "'I Am Because We Are': Giving Primacy to African Indigenous Values in HIV & AIDS Prevention." Pages 188-217 in African Ethics: An Anthology of Comparative and Applied Ethics. Edited by Munyaradzi F. Murove. Pietermaritzburg: University of Kwazulu Natal Press, 2009. [ Links ]

- Ekwunife, A. "A Philosophy and African Traditional Religious Values." Cahier des Religions Africaines 7 (1989): 34-39. [ Links ]

- Ephirim-Donkor, Anthony. African Religion Defined: A Systematic Study of Ancestor Worship among the Akan. Lanham: University Press of America, 2012. [ Links ]

- Fischer, Georg. Genesis 1-11. Freiburg: Herder, 2018. [ Links ]

- Gnuse, Robert K. "The 'Living Soul' in People and Animals: Environmental Themes from Genesis 2." Biblical Theology Bulletin 51/3 (2021): 168-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461079211019210. [ Links ]

- Habel, Norman C. "Introducing Ecological Hermeneutics." Pages 1 -8 in Exploring Ecological Hermeneutics. Edited by Norman C. Habel and Peter Trudinger. Atlanta: SBL, 2008. [ Links ]

- _________. The Birth, the Curse and the Greening ofEarth: An Ecological Reading of Gensis 1-11. The Earth Bible Commentary. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2011. [ Links ]

- Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis 1-17. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990. [ Links ]

- Hiebert, Theodore. "Air, the First Sacred Thing: The Concept of רוח in the Hebrew Scriptures." Pages 9-20 in Exploring Ecological Hermeneutics. Edited by Norman C. Habel and Peter Trudinger. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008. [ Links ]

- _________. The Yahwist Landscape: Nature and Religion in Early Israel. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. [ Links ]

- Jacob, Benno. Das Buch Genesis. Stuttgart: Calwer Verlag, 2000. [ Links ]

- Jahn, Janheinz. Muntu: An Outline of the New African Culture. New York: Grove, 1961. [ Links ]

- Kagame, Alexis. Sprache und Sein: Die Ontologie des Bantu des Zentralafrikas. Heidelberg: P.Kivouvou Verlag/Editions Bantoues, 1985. [ Links ]

- Kavusa, Kivatsi Jonathan. Humans and Ecosystems in the Priestly Creation Account: An Ecological Interpretation of Genesis 1:1-2:4a. Saarbrücken: Lambert, 2013. [ Links ]

- _________. "Social Disorder and the Trauma of the Earth Community: Reading Hosea 4:1-3 in Light of Today's Crises." Old Testament Essays 29/3 (2016): 481-501. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2016/v29n3a8. [ Links ]

- _________. "Creation as a Cosmic Temple: Reading Genesis 1: 1-2: 4a in Light of Willie van Heerden's Ecological Insights." Journal for Semitics 30/1 (2021): 1-23. [ Links ]

- _________. "Towards a Hermeneutics of Sustainability in Africa: Engaging Indigenous Knowledge in Dialogue with Christianity." Verbum et Ecclesia 42/1 (2021): 1-10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v42i1.2263. [ Links ]

- Keaveny, Paul. "Why Land Evokes Such Deep Emotions in Africa." The Conversation, 2015. https://theconversation.com/why-land-evokes-such-deep-emotions-in-africa-42125. [ Links ]

- Kia Busenki Fu-Kiau, K. African Cosmology of the Bântu-Kongo: Principles of Life and Living. 2nd Edition. Athelia Henrietta Press, 2001. [ Links ]

- Longman III, Tremper. The Book ofEcclesiastes.. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

- Luther, Martin. "An Open Letter on Translating" Translated from 'Ein Sendbrief D. M. Luthers. Von Dolmetzschen Und Fürbit Der Heiligenn' Pages 632-646 in Dr. Martin Luthers Werke Weimar: Hermann Boehlaus Nachfolger, 1909." Band 30, Teil II, 1530. http://www.bible-researcher.com/luther01.html. [ Links ]

- Maluleke, Tinyiko. "Black and African Theologies in Search of Contemporary Environmental Justice." Journal ofTheology for Southern Africa 167 (2020): 5-19. [ Links ]

- Mambwe, Kelvin and Dinis F. da Costa. "Nicknaming in Football: A Case of Selected Nicknames of National Football Teams in Southern Africa." International Journal of Innovative Interdisciplinary Research 2/4 (2015): 52-61. [ Links ]

- Morgan, Jonathan. "Transgressing, Puking, Covenanting: The Character of Land in Leviticus." Theology 112/867 (2009): 172-180. [ Links ]

- Patin, Etienne, Marie Lopez, Rebecca Grollemund, Paul Verdu, Christine Harmant, Hélène Quach, Guillaume Laval, et al. "Dispersals and Genetic Adaptation of Bantu-Speaking Populations in Africa and North America." Science 356/6337 (2017): 543-546. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1988. [ Links ]

- Pioso, Soren Marsh. "Africa Southeastern Bantu Ethnicity." Cited 12 May 2021. https://www.ancestry.com/cs/us/seo-header-test-africa-southeastern-bantu. [ Links ]

- Pope Francis. Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home (Encyclical Letter). Vatican: Vatican Press, 2015. http://www.vatican.va/content/dam/francesco/pdf/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si_en.pdf. [ Links ]

- Salami, Ali and Bamshad Hekmatshoar Tabari. "Igbo Naming Cosmology and Name- symbolization in Chinua Achebe's Tetralogy." Journal of Language and Literary Studies 33 (2021): 39-61. https://doi.org/10.31902/FLL.33.2020.2. [ Links ]

- Santucci, Luigi. The Canticle of the Creatures for Saint Francis of Assisi. Paraclete Press, 2017. [ Links ]

- Sarna, Nahum M. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989. [ Links ]

- Schmitz-Kahmen, Florian. Geschöpfe Gottes unter der Obhut des Menschen: Die Wertung der Tiere im Alten Testament. Neukirchenen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1997. [ Links ]

- Stiftung Oekumene. "Ten Affirmations on Justice, Peace and the Integrity of Creation." Cited 25 June 2020. Online: http://oikoumene.net/eng.global/eng.seoul90/eng.seoul.2.2/index.html. [ Links ]

- Sundermeier, Theo. The Individual and Community in African Traditional Religions. Hamburg: LIT, 1998. [ Links ]

- Taylor, John V. The Primal Vision: Christian Presence amid African Religion. London: SCM, 1963. [ Links ]

- Tempels, Placide. Bantu Philosophy. Traeslated by C. King. Paris: Présence Africaine, 1959. [ Links ]

- Thöne, Yvonne S. "Was ist das, ein Tier, und wohin gehört es: Eine biblisch-theologische Perspektive." Pages 35-48 in Räume der mensch-tier-Beziehung(en): Öffentliche Theologie im interdisciplinären Gespräch. Edited by Clemens Wustmans and Niklas Peuckmann. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt GmbH, 2020. [ Links ]

- Timmer, John. "How the Bantu People Surged across Two-Thirds of Africa." 2017. https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/05/how-the-bantu-people-surged-across-two-thirds-of-africa/. [ Links ]

- Tomlin, Graham. "The King James Version and Luther's Bible Translation." Anvil 27/3 (2010): 13-25. [ Links ]

- Tosam, Mbih J. "African Environmental Ethics and Sustainable Development," Open Journal of Philosophy 9 (2019): 172-92, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2019.92012. [ Links ]

- Vischer, Lukas. "The Theme of Humanity and Creation in the Ecumenical Movement." Cited 25 June 2020. Online: http://www.jaysquare.com/resources/growthdocs/grow10b.htm. [ Links ]

- Von-Rad, Gerhard. Genesis: A Commentary. London: SCM, 1972. [ Links ]

- White, Lynn. "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis." Science 155/3767 (1967): 1203-1207. [ Links ]

- World Council of Churches. Alternative Globalization: Addressing Peoples and Earth. Geneva: WCC Publications, 2005. [ Links ]

- _________. "Statement on Eco-justice and Ecological Debt." 2009. https://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/central-committee/2009/report-on-public-issues/statement-on-eco-justice-and-ecological-debt. [ Links ]

- Wustmans, Clemens. "Einerlei Geschick erfahren sie: Christliche Tierethik im Horizont der Nachhaltigkeitsdebatte." Page 179-99 in Räume der mensch-tier-Beziehung(en): Öffentliche Theologie im interdisciplinären Gespräch. Edited by Clemens Wustmans and Niklas Peuckmann. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt GmbH, 2020. [ Links ]

- Zorina, Zoya A. "Animal Intelligence: Laboratory Experiments and Observations in Nature." Entomological Review 85/1 (2005): 42-54. [ Links ]

Submitted: 09/09/2021

peer-reviewed: 01/11/2022

Accepted 02/11/2022.

Prof Dr Jonathan Kivatsi Kavusa, University of Pretoria and Alexander von Humboldt-Alumnus, e-mail: jokakiv@yahoo.fr. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8887-8843.

1 This article is produced with the support of Alexander von Humbold Stiftung.

2 Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (with an Introduction by John T. Bonner and Robert M. May; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 35.

3 Zoya A. Zorina, "Animal Intelligence: Laboratory Experiments and Observations in Nature," Entomological Review 85/1 (2005): 43.

4 Darwin, The Descent ofMan, 105.

5 Martin Luther, "An Open Letter on Translating: Translated from 'Ein Sendbrief D. M. Luthers. Von Dolmetzschen Und Fürbit Der Heiligenn' Pages 632-646 in Dr. Martin Luthers Werke, (Weimar: Hermann Boehlaus Nachfolger, 1909), 1530, http://www.bible-researcher.com/luther01. html.

6 Clemens Wustmans, "Einerlei Geschick erfahren sie: Christliche Tierethik im Horizont der Nachhaltigkeitsdebatte," in Räume der mensch-tier Beziehung(en): Öffentliche Theologie im interdisciplinären Gespräch (ed. Clemens Wustmans and Niklas Peuckmann; Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt GmbH, 2020), 180.

7 Bundesministerieum für Ernährung Landwirschfat und Verbraucherschutz, "Tierschutzgesetz in Der Fassung Der Bekanntmachung Vom 18. Mai 2006 (BGBl. I S. 1206, 1313), Das Zuletzt Durch Artikel 105 Des Gesetzes Vom 10. August 2021 (BGBl. I S. 3436) Geändert Worden Ist" (1972), 1. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschg/TierSchG.pdf.

8 Graham Tomlin, "The King James Version and Luther's Bible Translation," Anvil 27.3 (2010): 13.

9 Robert K Gnuse, "The 'Living Soul' in People and Animals: Environmental Themes from Genesis 2," Biblical Theology Bulletin 51/3 (2021): 169. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461079211019210.

10 By the term African, I mean the Bantu people, representing more than 310 million people in Africa. I will elaborate on the Bantu below.

11 Gerhard von-Rad, Genesis: A Commentary (London: SCM, 1972), 83.

12 Kivatsi Jonathan Kavusa, Humans and Ecosystems in the Priestly Creation Account: An Ecological Interpretation of Genesis 1:1-2:4a (Saarbrücken: Lambert, 2013), 158.

13 Ntu can be written differenty in various African languages (ndu, nto), but meaning remains the same, as will be shown in the next point.

14 Alexis Kagame, Sprache und Sein: Die Ontologie des Bantu des Zentralafrikas (Heidelberg: P.Kivouvou Verlag/Editions Bantoues, 1985), 106.

15 Kivatsi Jonathan Kavusa, "Towards a Hermeneutics of Sustainability in Africa: Engaging Indigenous Knowledge in Dialogue with Christianity," Verbum et Ecclesia 42/1 (2021): 7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4102/ve. v42i1.2263.

16 The word is mundu (humans) in the Kinande (language of the Nande people of the Congo) and is preceded by the definite article "o."

17 Janheinz Jahn, Muntu: An Outline of the New African Culture (New York: Grove, 1961), 100.

18 Norman C. Habel, "Introducing Ecological Hermeneutics," in Exploring Ecological Hermeneutics (ed. Norman C. Habel and Peter Trudinger; Atlanta: SBL, 2008), 2.

19 John Timmer, "How the Bantu People Surged across Two-Thirds of Africa," 2017. https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/05/how-the-bantu-people-surged-across-two-thirds-of-africa/.

20 Kimbwandènde Kia Busenki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology of the Bântu-Kongo: Principles of Life and Living (2nd ed.; Athelia Henrietta Press, 2001), 9.

21 Etienne Patin et al., "Dispersals and Genetic Adaptation of Bantu-Speaking Populations in Africa and North America," Science 356/6337 (2017): 543. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1988.

22 Soren Marsh Pioso, "Africa Southeastern Bantu Ethnicity," 2021. https://www.ancestry.com/cs/us/seo-header-test-africa-southeastern-bantu.

23 Placide Tempels, Bantu Philosophy (Transl. C. King; Paris: Présence Africaine, 1959), 30.

24 Musa W. Dube, "'I Am Because We Are': Giving Primacy to African Indigenous Values in HIV & AIDS Prevention," in African Ethics: An Anthology of Comparative and Applied Ethics (ed. Munyaradzi F. Murove; Pietermaritzburg: University of Kwazulu Natal Press, 2009), 200.

25 Norman C. Habel, The Birth, the Curse and the Greening of Earth: An Ecological Reading of Gensis 1-11 (The Earth Bible Commentary; Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2011), 55.

26 Georg Fischer, Genesis 1-11 (Freiburg: Herder, 2018), 184.

27 Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis (The JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 17.

28 Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis 1-17 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), 157.

29 Walter Brueggemann, "From Dust to Kingship," ZAW 84/1 (1972): 4.

30 Hamilton, The Book of Genesis 1-17, 158.

31 Fischer, Genesis 1-11, 185.

32 Sarna, Genesis, 17.

33 Benno Jacob, Das Buch Genesis (Stuttgart: Calwer Verlag, 2000), 95.

34 Jacob, Das Buch Genesis, 83.

35 Tremper Longman III, The Book ofEcclesiastes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 129.

36 Habel, The Birth, 55.

37 Ibid., 51.

38 Ellen F. Davis, Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture: An Agrarian Reading of the Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 28.

39 Habel, The Birth, 55.

40 Anthony Ephirim-Donkor, African Religion Defined: A Systematic Study of Ancestor Worship among the Akan (Lanham: University Press of America, 2012), 5.

41 The Nande (Banande) and Konzo (Bakonzo) are the same ethnic group. During the 1885 Berlin partition of Africa, one group stayed in Uganda while the other one crossed the Semuliki river to live in the eastern part of DR Congo close to Mountain Rwenzori. Those who stayed in Uganda are called Bakonzo while those residing in DR Congo are named Banande. L. Bergams, Les Wanande: Les Baswagha-Aperçu Historique (Tome 1Butembo: Editions A.B.B; Assomption-Butembo-Beni, 1970), 9.

42 Jonathan Morgan, "Transgressing, Puking, Covenanting: The Character of Land in Leviticus," Theology 112/867 (2009): 178.

43 Kivatsi Jonathan Kavusa, "Social Disorder and the Trauma of the Earth Community: Reading Hosea 4:1-3 in Light of Today's Crises," Old Testament Essays 29/3 (2016): 495, https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2016/v29n3a8.

44 Luther, An Open Letter on Translating.

45 Theodore Hiebert, The Yahwist Landscape: Nature and Religion in Early Israel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 62.

46 Fischer, Genesis 1-11, 186.

47 Yvonne S. Thöne, „Was ist das, ein Tier, und wohin gehört es: Eine biblisch-theologische Perspektive," in Räume der mensch-tier Beziehung(en): Öffentliche Theologie im interdisciplinären Gespräch (ed. Clemens Wustmans and Niklas Peuckmann; Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt GmbH, 2020), 36.

48 Hamilton, The Book of Genesis 1-17, 158; Theodore Hiebert, "Air, the First Sacred Thing: The Concept of רוחin the Hebrew Scriptures," in Exploring Ecological Hermeneutics (ed. Norman C. Habel and Peter Trudinger; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008), 12.

49 Habel, The Birth, 50; Fischer, Genesis 1-11, 186.

50 Fischer, Genesis 1-11, 187.

51 Thöne, "Was ist das," 38.

52 Von Rad, Genesis, 83.

53 Fischer, Genesis 1-11, 208.

54 Richard J. Bauckham, Living with Other Creatures: Green Exegesis and Theology (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2011), 5.

55 Habel, The Birth, 55.

56 A. Ekwunife, "A Philosophy and African Traditional Religious Values," Cahier des Religions Africaines 7 (1989): 36.

57 li Salami and Bamshad Hekmatshoar Tabari, "Igbo Naming Cosmology and Name-symbolization in Chinua Achebe's Tetralogy," Journal of Language and Literary Studies 33 (2021): 45. https://doi.org/10.31902/FLL.33.2020.2..

58 abel, The Birth, 55.

59 Thöne, "Was ist das," 36.

60 Thöne, "Was ist das, " 38.

61 Florian Schmitz-Kahmen, Geschöpfe Gottes unter der Obhut des Menschen: Die Wertung der Tiere im Alten Testament (Neukirchenen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1997), 22.

62 Kivatsi Jonathan Kavusa, "Creation as a Cosmic Temple: Reading Genesis 1: 1-2: 4a in Light of Willie van Heerden's Ecological Insights," Journal for Semitics 30/1 (2021): 16.

63 Thöne, "Was ist das," 40.

64 Kelvin Mambwe and Dinis F. Da Costa, "Nicknaming in Football: A Case of Selected Nicknames of National Football Teams in Southern Africa," International Journal of Innovative Interdisciplinary Research 2/4 (2015): 55.

65 Habel, The Birth, 55.

66 Mbih J. Tosam, "African Environmental Ethics and Sustainable Development," Open Journal ofPhilosophy 9 (2019): 172-92, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2019.92012.

67 Kagame, Sprache und Sein, 106.

68 Tinyiko Maluleke, "Black and African Theologies in Search of Contemporary Environmental Justice," Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 167 (2020): 20.

69 Paul Keaveny, "Why Land Evokes Such Deep Emotions in Africa," The Conversation, 2015, https://theconversation.com/why-land-evokes-such-deep-emotions-in-africa-42125.

70 Jahn, Muntu: An Outline of the New African Culture, 50.

71 John V. Taylor, The Primal Vision: Christian Presence amid African Religion (London: SCM, 1963), 50.

72 Theo Sundermeier, The Individual and Community in African Traditional Religions (Hamburg: LIT, 1998), 18.

73 Pope Francis, Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home (Encyclical Letter) (Vatican: Vatican Press, 2015), 5, http://www.vatican.va/content/dam/francesco/pdf/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si_en.pdf.

74 Lynn White, "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis," Science 155/3767 (1967): 1206.

75 Luigi Santucci, The Canticle of the Creatures for Saint Francis of Assisi (Paraclete Press, 2017).

76 Pope Francis, Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home, 11.

77 Ibid., 4.

78 Pope Francis, Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home, 13.

79 Lukas Vischer, "The Theme of Humanity and Creation in the Ecumenical Movement," [cited 25 June 2020]. Online: http://www.jaysquare.com/resources/growthdocs/grow10b.htm.

80 Stiftung Oekumene, "Ten Affirmations on Justice, Peace and the Integrity of Creation," accessed 25 June 2020, http://oikoumene.net/eng.global/eng.seoul90/eng.seoul.2.2/index.html.

81 World Council of Churches, Alternative Globalization: Addressing Peoples and Earth (Geneva: WCC Publications, 2005), 3.

82 World Council of Churches, "Statement on Eco-justice and Ecological Debt," 2009, https://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/central-committee/2009/report-on-public-issues/statement-on-eco-justice-and-ecological-debt.

83 World Council of Churches.