Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 no.3 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n3a16

ARTICLES

The Anti-Yahweh Label lassaw' in Jeremiah (PART 1)

Wynand C. Retief

University of the Free State, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The traditional stance is that לשׁוא in Jeremiah (2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 18:15 and 46:11) denotes futility, mostly translated as "in vain. " This study scrutinises the first three texts (Jer 2:30; 4:30 and 6:29) in an effort to substantiate and modify a recent hypothesis that this term is instead a reference to the god Baal, " The Vain/Worthless One." Support for the said hypothesis is gained by (1) a tentative observation in the discussion of Jer 2:30 that שׁוא futility, "in vain ") is apparently limited to wisdom literature, whereas the Jeremiah texts are part of a cultic-legal corpus within a covenantal setting where the lexeme consistently appears as the prepositional prefixed definite form לשׁוא and apparently refers to prohibited objects of worship; (2) a search for intertexual clues in Jer 4:30; and (3) alertness to recurring key words and chiastic patterns in the context of Jer 6:29. In the course of working through the relevant texts, the notion took shape that the preposition ל־ is -besides meaning "for, for the sake of - a technical term indicating covenantal relationship.1 It therefore seems that לַשָּׁוְא is not only a pejorative reference to Baal but also a label of the contra and anti-Yahweh overlord/s (בעלים/בעל) in (illegal) covenant relation to Israel.

Keywords: Jeremiah, Exegesis, Baal, Deities, Worthless

A INTRODUCTION

This article is a follow-up (in two parts) to the proposition that lassãw' in Jeremiah, together with the definite forms of seqer, boset and hebel (in combination with different prepositions), refers to the god Ba'al, as alternative proper names of the deity, most probably intended as pejoratives.2 At the end of that study, further investigation into related MT Jeremiah texts is suggested,3which is partly taken up in the present article. This study is an effort to support the interpretation of the term lassaw' in Jeremiah as "in (covenantal) relation to" or "for the sake of The Vain One (i.e. "The Worthless/Futile One" or "The Deception/Deceptive One,")4 as a possible reference to Ba'al, over against the traditional, popular interpretation "in vain." The texts in question are Jer 2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 18:15 and 46:11, of which 2:30; 4:30 and 6:29 are discussed in this article and 18:15 and 46:11 in its sequel.

B JEREMIAH 2:30 (WITHIN 2:29-30)

This text is demarcated by the setumah before verse 29 and the superscription introducing the oracle in verse 31. The oracle is textually situated within Jer 2:14:4, which, in diachronic orientated studies, is assumed to be an early collection of oracles by the prophet. Lundbom is of the opinion that verse 29-30, by means of keywords, forms part of a series of short oracles in which Yahweh refutes charges made against him (2:29-37),5 as part of a chapter that centres on apostasy (in 3:1-4:4 shifting to repentance).6 A recent synchronically based research by Job Y. Jindo on metaphors in the Jeremiah text convincingly demarcates this passage as a section of a unit that spans the whole of chapter two.7 According to Jindo, Israel, portrayed in the double images of family relationships (Yahweh's faithful bride) and horticulture (Yahweh's choicest fruit) is rebuked for her religious disloyalty, trusting foreign deities. This triggers Yahweh's lawsuit (rib) against his covenant breaching people who are turning from a symbol of blessing into a symbol of curse, by metaphorically returning to the Egypt they were taken from (2:6, 36).8

Within this symbolically charged passage the divine name (The) Ba'al הַבַַּעַל occurs for the first time in Jer 2:8 in the phrase הַנְבִיאִים נִַּבְאוּ בַַּבַעַל, "the prophets prophesied by Ba'al." In the lectio continua of this chapter, Ba'al is encountered once more in verse 23 in the plural "How can you say, 'I have not defiled myself, I have not followed the be'alïm'?" (אֵיךְ תַּאֹּמְרִי לַּאֹּ נִַּטְמֵאתִי אַַּחֲרֵיַּהַבְעָׁלִים לַּאֹּ הַָּׁלַכְתִי). Yahweh's (legal) complaint against his covenant partner, Israel/Judah, is explicitly directed against her/their turning away from Yahweh, towards Ba'al. The implicit references or allusions to Ba'al in the first part of the chapter (in particular vv. 4-13)9 are generally recognised by commentators, labelled as a "pun on Baal" (Bright), or a "disparagement of Baal" (Lundbom). They are הַהֶבֶל (v. 5), לא־יועלו (v. 8), לוא יַּועל(v. 11). In a sample of three commentaries,10 הַהֶבֶל (v. 5) is rendered as "Lord Delusion" (Bright), "The Delusion" (Thompson), "The Nothing" (Lundbom); לא־יועלו (v. 8) as "The Useless Ones" (Bright, Thompson), "No Profits" (Lundbom); and לוא יַּועל (v 11) as "Lord Useless" (Bright), "The Useless One" (Thompson) and "No Profit" (Lundbom). The terms לא אַּלהי (v. 11) and [אֶלֹהֶיךָ ]ַּאַשֶׁר עְַַּשִיתָׁ לַָּׁךְַּ (v. 28) logically point to the same entity, as part of the multiple references and allusions to ba'al or the many local be 'alïm within Israel/Judah, as portrayed in the chapter.

In summary, the context of לַשָׁוְא in Jer 2:30, permeated by references to Ba'al, supports the notion that this term may refer to this deity. Notwithstanding, nearly all modern day interpreters uncritically assume that לַשָׁוְא in this verse has the general meaning of "in vain."11 This reading goes hand in hand with the assumption that the verb hikkêtï, "I have beaten" refers to "a lesser chastening, since the beating was done 'in vain'."12 Although נכה hip 'il often means "beat to kill," it does not logically fit the sentence that would read "In vain I have beaten your sons, (for) they did not accept correction." The logic of this stance is that the non-acceptance of correction is the reason why the beating (not to kill) was "in vain." This interpretation is supported by language typical of wisdom literature, where the verb נכה hip 'il in different forms is used for what Ilse von Loewenclau calls "pedagogical beating"13 (Prov 17:10; 19:25; 23:13, 14, 35). In the same category, לקח מַּוּסָׁר, to accept discipline, is befitting the good student, according to Prov 1:3; 8:10; 24:32. Understanding לַשָׁוְא as "in vain" therefore presupposes a wisdom reading of both cola of verse 30a.

The fact that the entire verse 30 is difficult14 should however make us attentive to the probability that the text may have gone through a redaction process15 in which the wisdom genre of verse 30a could have been inserted into the prophetic oracle with a polemic tone. The end product is akin to so-called prophetic lawsuit utterances. In this utterance, the rib of Judah against Yahweh is turned around as Yahweh's rib against Judah (29a), an accusation of rebellion (29b), which manifests in the killing of Yahweh's prophets in their midst (30b).16The killing, "your sword eats your prophets like a devouring lion," is directly related to Yahweh's hikkêti 'et-nebi'êkem (30a').

If the reading of לַשָׁוְא as "in vain" is maintained, Yahweh's "pedagogical beating" stands in juxtaposition to Israel's act of "beating to kill." The former as wisdom text, the latter the last clause (30b) of a prophetic judgement (29b, 30b) that 'frames' a wisdom phrase (30a). This reading conveys the sharp contrast between Israel's deadly actions exemplifying rebellion against Yahweh, and Yahweh's leniency. Yahweh has merely given "your sons" a corrective "slap on the wrist." This however, seemed to be "in vain," for the hand of discipline was shrugged off and the killing of the prophets continued.

Significantly, independent of its referential value, לַשָׁוְא is in the strategic position serving as the introductory lexeme of the (original) wisdom clause, which connects the prophetic utterance to a (presumed former) wisdom saying. The exact grammatical form of saw' שָׁׁוְא is thus of essence. A probe of the lexeme17 shows that in the wisdom literature, including the so-called wisdom

Psalms, saw' consistently occurs in its indefinite form without prefixes, never as lassaw' לַַּשָׁוְאַּ (definite form with prepositional prefix /-).18 On the other hand, lassaw' לַַּשָׁוְאַּ in its absolute form (and not as part of a construct chain19) - never saw'שָׁׁוְא - is utilised in legal-cultic texts that apparently speak of prohibited objects ' of worship (Exod 20:7 = Deut 5:11; Pss 24:4; 139:20?). The only prophetic texts with לַַּשָׁוְאַּ are those in Jer (2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 18:15; 46:11) and the constructs חַבְלֵי־הַשָׁוְא in Isa 5:18 and חְַמֹּלוֹת־הַשָׁוְא in Zech 10:2. The inference from this overview is that לַשָׁוְא in Jer 2:30a is atypical of a wisdom text but typical of a cultic-legal one. If it would be part of a wisdom saying, the expectation would be that saw' would occur in its indefinite form without preposition. This very form with the meaning "in vain" is attested in Pss 127:1, 2:

אִם־יהוה לַּאֹּ־יִבְנֶה בַַּיִת שַַָּּׁׁוְא עַָּׁמְלוּ בַּוֹנָׁיו בַּוַֹּ

אִם־יהוה לַּאֹּ־יִשְׁמָׁר־עִיר שַַָּּׁׁוְא שַָּׁׁקָׁד שַּׁוֹמֵר

שָׁׁוְא לַָּׁכֶם מַַּשְׁכִימֵי קַּוּם מְַּאְַחְַרֵי־שֶׁבֶת אַֹּּכְלֵי לֶַּחֶם הַָּׁעְצַָׁבִים

If Yahweh does not build the house,20 in vain its builders labour on it. If Yahweh does not guard the city, in vain the guard is vigilant. Futile for you, early risers, late stayers, consumers of the bread of sorrows...

This setting of the indefinite form of שָׁׁוְא in the wisdom genre with the meaning of 'futile', 'in vain', may well be an indication that לַשָׁוְא in Jer 2:30a is not taken over from a wisdom text together with the rest of the line but is rooted in the surrounding prophetic (cultic-legal) text, speaking of prohibited behaviour or actions regarding Yahweh worship. Thus, לַשָׁוְא should rather be understood in referenece to the prohibited object of worship, most probably a pejorative allusion to Baal, "The Vain/Worthless One." The function of the preposition lis to be determined by the literary setting of לַשָׁוְא which hopefully will emerge from the ongoing discussion below.

As a legal-cultic text, נכה hip'ïl denotes Yahweh's judgement. The מוּסָׁר "correction, discipline," not taken up, is tantamount to the breaching of covenant. Further, מוּסַרַּ is a variant of מוֹסְרָׁה = strap (that binds one to one's yoke), attested in the repetitive Jeremian saying שׁבר עַֹּּל נִַּתַק מַּוסרותַּ = "To break the yoke, to snap the straps" (2:20; 5:5 and 30:8), where it is used as metaphor for the dissolution of a covenant relation. The expression, מוּסָׁר לַּאֹּ לַָּׁקָׁחוּ, a refusal to accept (take up) "the tie" (of covenantal bondage/discipline), is equivalent to נִתַק מַּוסרו. As a prophetic judgment in covenantal-cultic-legal terms, verse 30a could well be paraphrased:

"[ל־]21The Vain One" I executed your sons; they refused to mend the ties of covenantal discipline which they broke, your sword has devoured your prophets like a ravenous lion.

It is by now clear that the text renders a disputation (rïb in the broad sense of the word) on covenant breaching. The point of contention is לַשָׁוְא. Its position, immediately following the declaratory formula נְאֻם־יְהוָָֽׁה and foregrounding Yahweh's curse, indicates its importance as possible basis for the breaching of covenant and imminent curse. The meaning of ל־ could be causal (the reason for Yahweh's curse) and/or a technical term for a covenantal relationship in which the vassal belongs to the overlord. Both of these functions of the preposition are presented in Gesenius' Lexicon, respectively, as "(c) dative of cause and author" and "(b) dative of possessor,"22 in other words, "because of, caused by hassãw' " and/or "belonging to hassãw'." Here, the second option should be preferred since the preposition seldom functions in a causal relationship,23 while the latter function of the preposition attached to the name of the deity expressing possession is attested in Isa 44:5, for example (as לַיהוה, "belonging to YHWH").24This is arguably a core covenantal formula, which is visible within the relational or covenant formulae identifiable in the OT/HB. In all types of these formulae, the preposition ל־ is prefixed to each covenant partner indicated by such formula.25 Of the multiple times that לַיהוה occurs in MT Jeremiah, at least three instances appear to bear a covenantal reference (2:3; 4:4 and 5:10).26

In this light, לַשָׁוְא undoubtedly plays a much more important role than merely indicating futility. In fact, the lexeme appears to summarise the legality of Yahweh's judgement. Whereas the legal covenant relationship of the vassal is indicated by לַיהוה, after covenant breach and transferal of loyalty to another lord (ba 'al), לַשָׁוְא seems to replace לַיהוה. In other words, Yahweh, the former Lord, is replaced by another lord, according to the prophetic text hassãw', "The Worthless One." The inference is that, since לַיהוה indicates covenantal/relational status, allegiance and even self-identification of the vassal (e.g. Isa 44:5; Jer 2:3; 4:4; 5:10), the same would apply to לַשָׁוְא. Israel/Judah who used to be the former is now the latter. The inference is that לַשָׁוְא in this and maybe other texts could, apart from a reference to the overlord, even function as vocative that may be paraphrased, "You, Israel/Judah, identifying yourself with The Worthless One'" The primary position of the term within the phrase supports this notion.

Jeremiah 2:29-30 could therefore be understood in terms of a legal disputation (rib), more precisely the judgement of the rightful suzerain (Yahweh) on the state of covenant loyalty of his (disloyal) vassal, Israel/Judah/Jerusalem. The elements of the judgement could be imagined as follows:

(29) - Introductory question: לָׁמָׁה תַָּׁרִיבוּ אֵַּלָׁי Why do you sue me?

- General statement: Israel/Judah's covenantal disloyalty:

כֻלְכֶם פְַּשַׁעְתֶם בִַּי All of you rebelled against me

- Status and Source of utterance: נְאֻם־יְהוָׁה declaration of Yahweh

(30) - Legal basis for judgement: לַשָּׁוְא [ = vassal's (changed) covenantal allegiance/status/(self) identification]:

([You,] Judah/Israel) belonging to, bound to "The Worthless One"

- Execution of curse following covenant breach: הִכֵיתִי אֶַּת־בְנֵיכֶם I executed your sons

- Manifestations of covenant breach in terms of 1) Non-compliance of covenant stipulations: מוּסָׁר לאֹּ לָׁקָׁחוּ they did not take up (covenantal) discipline

2) Public enmity towards (emissaries of) Yahweh: אָׁכְלָׁה חַרְבְכֶם נְבִיאֵיכֶם כְאַרְיֵה מַשְׁחִית your sword has devoured your prophets like a ravenous lion.

1 Jeremiah 2:30 - Conclusion

In the exegetical process, the following contextual indicators and its interpretational implications were suggested for Jeremiah 2:30:

1. The grammatical form of saw' שָׁׁוְא seems to be genre bound. Tentative investigation of occurrences of the lexeme in wisdom literature, including the so-called wisdom Psalms, consistently utilises saw' in its indefinite form without prefixes, rendered as "in vain" (Ps 127 being a prime example). On the other hand, lassaw' (לַשָׁוְא; determined, with prepositional prefix l-) seems to appear consistently in non-wisdom texts of a cultic-legal nature, apparently as reference to prohibited objects of worship. Besides the five texts in Jeremiah (2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 18:15; 46:11) and the constructs חַבְלֵי־הַשָׁוְא in in Isa 5:18 and חְַמֹּלוֹת־הַשָׁוְא in Zech 10:2, the same lexeme is shared by Exod 20:7 = Deut 5:11 as well as Pss 24:4 and 139:20. These texts could all be categorised under the broad label of legal-cultic texts. The implication for Jer 2:30 is that a wisdom reading of the text conveying Yahweh's attempt at 'pedagogic' correction cannot be maintained. The text clearly functions as a judgement in cultic-legal terms within a covenantal frame of mind. The logic of consistency would imply that none of the לַשָׁוְא referents in Jeremiah can be interpreted as a simple equivalent of שָׁׁוְא. A focused study on the genre specificity of שָׁׁוְא will confirm or question this stance.

2. It follows that as the initial לַשָׁוְא in the phrase לַַּשָׁוְ אַּ הִכֵֹ֣יתִי אֶת־בְנֵיכֶֶ֔ם מוּסָָׁ֖ר לֹ֣אֹּ לָׁקָָׁ֑חוּ is foreign to wisdom texts but characteristic of legal-cultic utterances, the 'wisdom' reading of "pedagogical beating" or correction cannot be maintained. The מוּסַר of the second colon, מוסר לַּא לַּקחו, is a variant of מוֹסְרָׁה = strap (that binds one to one's yoke), attested in the repetitive occurrence of the metaphor for the dissolution of a covenant relation, namely שַּׁבר עַֹּּל נִַּתַקַּמוסרותַּ = "To break the yoke, to snap the straps" (2:20; 5:5 and 30:8). The prophetic judgment oracle in which lassaw' (לַשָׁוְא) occurs (initially in 2:30), is part of a broader text spanning at least Jer 2-30, marked by the repetitive metaphor for dissolution of (the Yahweh) covenant. These are clear indications of the covenantal and legal-cultic setting of lassaw ' (לַשָׁוְא).

3. Reckoning with the possibility that hassãw' could refer to a substitute suzerain or "master" (ba 'al) in the god-people covenant, a replacement of Yahweh, the inference is that the prefix l- could (inter alia) have a similar denotation to that of לַיהוה in Isa 44:5 (and other places): "belonging to, possession of (Yahweh)" - reflecting the same preposition prefixed to both partners in 'relation' or 'covenant' formulas. In this case, it could mean that the legal ownership and relational status of the vassal, derived from the particular overlord, has changed from לַיהוה to לַשָׁוְא. This total change of identity, attachment and submissiveness is apparently the legal basis for the prophetic judgement. A tentative suggestion, with attention to the primary position of the term within the phrase, is that לַשָׁוְא could even have a vocative value in Jer 2:30 that could be paraphrased, "[You, Israel/Judah,] identifying yourself with The Worthless One."

C JEREMIAH 4:30 (WITHIN 4:29-31)

Verses 29-31, although not demarcated as such, clearly form a self-contained poem in three stanzas (29, 30, 31),27 telling a three-episode story: (I: v. 29) the enemy is approaching the country, resulting in the hasty evacuation of all cities; (II: v. 30) the exception is one woman that represents herself in a harlot-like fashion in an effort to seduce the approaching enemy, not realising that she is rejected by this enemy; (III: v. 31) finally, the yelling of 'daughter Zion' (to be identified with 28שָׁׁד in v. 30)29 is heard, when she faces her killers. The description in verse 30a of the woman who adorned herself contains the term under discussion, namely lassaw.' There are two clear equivalents of this self-adornment scene in 2 Kgs 9:30 and Ezek 23:40-41,30 which suggest inter-texual links.

Ezekiel 23 contains the theme of the adornment of the prostitute/adulteress in verses 40b-41 (self-adornment) and 42b (adornment by her 'lovers'). Jeremiah 4:30 relates only to the former. The relationship of Ezek 23:40b-41 to the entire chapter should be investigated briefly. Verses 1 -39 apparently form a unit around the allegory of the two adulterous sisters, Oholah and Oholibah, identified as Samaria (Israel) and Jerusalem (Judah). The MT setumôt indicate it as a narrative in two parts (vv. 1 -10, 11 -21), followed by three judgement oracles (vv. 22-27, 28-31, 32-35) and Yahweh's challenge to Ezekiel to judge the two sisters (vv. 36ff). Verse 39 already shows signs of disparity, with the shift of suffixes and probably verbs from 3fp to 3mp forms. From verse 40 onward, the text seems to be incoherent and chaotic in content and grammatical forms, alternating between feminine and masculine forms in the third person plural. Therefore, verses 40ff were suggested to be either later additions or glosses,31 Ezekiel's unedited draft32 or a reflection of Ezekiel's struggle to recount the message or even his ambivalence to it.33 Alternatively, it is seen as an intentional (rhetorical) reflection of "chaos" as a prominent and recurring theme.34 The study of Andrew Compton on deixis variation as a literary device in Ezekiel35 convincingly shows that the alternation of grammatical person in this text is just one example of intentional discourse markers in Ezekiel, where "(t)his rapid-fire shift of deixis [between masculine and feminine] is evidence of the splintering of the allegory; the metaphor of a sexually immoral woman is giving way to their real-life referents: Israel and Judah."36 Thus, verses 40-49 should be recognised as an intrinsic part of the entire chapter.

What concerns us is that from Ezek 23:40a to 40b-41, a shift of addressee is made from "they," 3fp (v. 40a) to "you" 2fs (vv. 40b-41). This person-specific form of address simulates verse 21 where Oholibah is directly addressed. The rhetorical connection to Oholibah in verses 40b-41 is content-wise supported by verses 16-17a (her sending for men and a description of her bedroom furniture).37 The context therefore indicates that Oholibah (=Jerusalem/Judah) is addressed in verses 40b-41 as the fornicator adorning herself in view of the "men from afar."

לַאֲשֶָׁ֥ר רָׁחַַ֛צְתְַּ כָׁחַָ֥לְתְַּ עֵינַָ֖ יִַ֖ךְ וְעָָׁ֥דִית עֶַָּֽדִי

for whom you washed yourself, painted your eyes, and decorated yourself with ornaments.

Her subsequent actions, "You sat on an elegant couch, with a table spread before it on which you had placed my incense and my olive oil" (v. 41), metaphorically portrays the idolatrous position and actions of the inhabitants of Jerusalem taking place in Yahweh's temple, as already expressed by the deictic shift to 3mp in verse 39 and probably already by the verbs in verse 38. The root motivation of the self-adornment actions of Jerusalem as the adulterous Oholibah (literally the people) is captured in the prepositional prefixed relative לַאֲשֶׁר which links Oholibah's 'lovers' (v. 40a) with her actions (v. 40b). The relative represents the antecedent, the 'men from afar' and the preposition apparently indicates a dative mode, "for (the sake/benefit of)." The self-adornment is self-giving, meant to attract and satisfy partners in an illicit sexual relationship thereby supporting and continuing the relationship. The change in clientele, from beautiful young heroes (vv. 12-16) to drunks in the wilderness (vv. 42), supports the remark that "one senses in vv. 40-44 an image of harlots with fading beauty, whose toilets are of necessity more elaborate, whose level of clientele has degenerated, whose day has nearly passed."38

In other words, Ezekiel's self-adoration theme participates in a metaphorical setting which is revealed as such by the explanation of the allegorical names and self-interpretation of the latter part (vv. 38ff) as the people's real-life idolatry (of which the preceding metaphor speaks), by means of the rhetorical device of deictic variation. The same setting and principle are at work in the Jeremiah text. The motivation for the self-adoration in Ezekiel (23:40) is essentially expressed by the term לַאֲשֶׁר ("for whom..."/"for the sake/benefit of..."). The core lexeme for this root motivation in Jer 4:30 is לַשָׁוְא (assuming that it alludes or refers to Baal as "The Worthless One"). The similarity in grammatical form between Ezekiel and Jeremiah, namely [preposition l- + referent], may well present a semantic-rhetoric similarity. In this light, Jer 4:30 could be read as, "for the sake of 'The Worthless One' you beautified yourself...."

It is noteworthy that Ezek 23 is the only OT/HB text apart from Jer 4:30 where the key word עגב appears (repeatedly - vv. 5, 7, 9, 12, 16, 20). The Jeremiah text under discussion is linked to Ezek 23 with more than one strand.

The other text relating to Jeremiah 4:30 is 2 Kings 9:30 in terms of a self-adoration scene. It introduces the episode of Jezebel's last desperate act to challenge Jehu and uphold herself when confronted by him on his warpath (vv. 30-37). This scene of the death of Jezebel concludes the greater narrative of Yahweh's struggle against (Israel's worship of) Ba'al (1 Kgs 15ff), instigated by Ahab and Jezebel (cf. 1 Kgs 16:30-33). Jezebel's actions in 2 Kgs 9:30, against the background of an approaching enemy (Jehu), is pictured in the words:

וַתָׁשֶם בַַּפוּךְ עֵַּינֶיהָׁ וַַּתֵיטֶב אֶַּת-ראֹּשָׁׁהּ וַַּתַשְׁקֵף עַַּד הַַּחַלוֹן

And she applied makeup to her eyes, and beautified her head, and looked out of the window.

This verse is essentially the same description of the acts of the lady questioned in Jer 4:3039 (read against the background of Stanza 1, verse 29, a scene of fear of the approaching enemy):

וְאַתִי שַָּׁׁד֜וּד מַַָּֽה־תַעֲשִִׂ֗י כִַָּֽי־תִלְבְשִִׁׁ֨י שַָּׁׁנִ֜י כִַּי־תַעְדִֹ֣י עֲַּדִי־זָׁהִָׁׂ֗ב כִַָּֽי־תִקְרְעִִ֤י בַַּפוּ ךְ עֵַּינֶַ֔יִךְ

You, one overrun by the enemy40, what are you doing, that you dress yourself in scarlet, that you put on golden jewellery, that you enlarge your eyes with black paint?

The phrase following the self-adornment of "the lady in waiting" is the focus: תִתְיַפִָ֑י מַָּׁאֲסוּ־בָָׁ֥ךְ עַֹּּגְבִָ֖ים נַַּפְשֵָׁ֥ךְ יְַּבַקֵָֽשׁוּלַשָָׁ֖וְא. The preceding phrase is summarised in the hitpael (reflexive) of the verb יפה, "you beautify yourself," directly after the introductory lassãw '. The phrase לשׁוא תַּתיפי is the first colon of a two cola phrase in which the rhetoric-semantic relation between the two cola can be construed in a variety of ways. This study chooses not to infer the meaning of lassãw' from these potential relationships. Rather, the starting point would be the potential meanings "in vain" or "for/belonging to The Vain One," which in each case will determine how the relationship should be understood. The logic of the semantic relationship or lack of it would ultimately support or critically challenge the specific choice.

The generally accepted "in vain" for lassaw' ("in vain you beautify yourself, those who lust after you have rejected you, they seek your life") fits a causal-epexegetical relationship. "You beautify yourself in vain, that is, your act of beautification (presumably to entice your suitors) is futile because / explained by the fact that your suitors (for whom you beautify yourself in order to entice) rejected you, wanting you dead."

A reading of lassãw ' (as expounded in Jer 2:29-30) as "for The Worthless One" or "belonging to The Worthless One" would be the root motive for "you beautify yourself." The second colon "those who lust after you41 reject you, they want your life (death)" would then come as a shocking surprise for the adulteress Judah/Jerusalem who has to face the wrath of her עגבים, the senior partners (so understood by the LXX) in the adulterous relationship thus far. Understood to be foreign nations and their gods with whom Judah/Israel associates, Jeremiah would most probably allude to Ba'al adherents. Through the prism of lassãw ' as reference to Judah's illegal covenantal relationship with Ba'al, as the root motivation of her effort to adorn herself, implicitly in order to attract her 'lovers,' עגבים (LXX: οἱ ἐρασταί σου), the text would convey the message that those whom Judah associates with within the circles of Baal worship, are desiring not only her body, but her soul, that is, her death.

The above reading is reflected in Ezek 23 and supported by the main plot of 2 Kings. According to the first two judgment oracles against Oholibah (Ezek 23:22-34), the 'lovers' of the adulteress will come, sent by Yahweh, to destroy her. The plot of the broader Jehu narrative in 2 Kgs is that of Yahweh's struggle against Ba'al and his eventual destruction of Ba'al worship from Israel at the hand of Jehu, starting with Jezebel, the embodiment of Ba'al allegiance. This can be demonstrated by 2 Kgs 9 itself. According to 9:22, Jezebel's activity in Israel is described as harlotry (זנתים) and sorcery (כשף) which cannot be taken literally but rather as a literary strategy comparable to other ANE texts to present Jezebel pejoratively as a prostitute.42 What motivated her to adorn herself is unclear from 2 Kings. The various motifs theoretically posited from that text43 are unsure and have no direct bearing on the Jeremiah text. Therefore, the actions and words of Jezebel in 2 Kgs 9:30-31 are unhelpful in discerning the meaning of lassãw in Jer 4:30. The writer of the latter text apparently has no interest in the theoretical motivation of Jezebel's self-beautification in 2 Kgs 9:30. The same portrait is repainted in Jeremiah, with its own internal logic. What seems to be of essence, though, is the broader context and plot of the Kings narrative that most probably directs the meaning of lassãw ' in Jer 4:30 to Ba'al allegiance.

Against the backdrop of 2 Kings and the parable in Ezekiel 23, both harsh in their anti-Baal polemics, the reader of Jer 4:30 should be alert to the probability of such a polemic motif. This would shift the generally assumed meaning away from לַשָׁוְא as her vain effort to adorn herself, implying that she tried unsuccessfully to please her עגבים. Instead, לַשָׁוְא would be coded language expressing the hidden motivation for her acts and strategies (to beautify herself), namely for the sake of 'The Worthless One,' that is, to please Ba 'al 44 and/or belonging to 'The Worthless One,' that is, as covenant partner of Ba'al. The fact that her עגבים rejected her and wanted her dead is in this reading a bitter irony, a prophetic warning to Israel/Judah in terms of the memory and metaphorical value of Jezebel, an incisive criticism of Baal worship and a warning of its dire consequences. The message would then be that Jerusalem's45 idea that she is favoured by foreign nations and/or their gods46 through her allegiance to Baal, has made her blind to the fact that she is actually socially and mortally endangered by Baal adherents abroad and within her own circles, for the very reason of her instinctive, deep-seated flirtation with Baal.

1 Jeremiah 4:30 - Conclusion

Read together with 2 Kgs 9:30 and Ezek 23:40-41, hassãw ' in Jer 4:30 as "The Vain One," alluding to Baal, accounts for the wider polemical setting and metaphoric connotations of the text. While the plot of 2 Kings 9 fits that of the three-stanza poem in Jer 4:29-30, the syntax of Ezek 23:40 with special reference to the grammatical form and function of ל־אשׁר suggests the same meaning for לשׁוא in Jer 4:30, namely "for the sake of Jerusalem's idolatrous flirtation with hassãw, "Lord Vanity."47 A relational-covenantal meaning for לשׁוא (in allegiance with hassãw) should, however, not be excluded, since it appears to be motivated by the covenantal foil of the Kings narrative where Jezebel represents the Baalist antithesis of Israel's covenant with Yahweh.

D JEREMIAH 6:29 (WITHIN 6:27-30)

27 בַָּׁחַֹּ֛ון נְַּתַתִָ֥יךָ בְַּעַמִָ֖י מִַּבְצָָׁ֑ר וְַּתֵדַַ֕ע וַּּבָׁחַנְתָָׁ֖ אֶַּת־דַרְכָָֽׁם׃ 28 כַֻּלָׁ ם סַָּׁרֵֹ֣י סַָֹּּֽורְרִֶ֔ים הַֹּּלְכֵָ֥י רַָּׁכִָ֖יל נְַּחֹֹּ֣שֶׁת וַּּבַרְזֶָ֑ל כַֻּלָָׁ֥ם מַַּשְׁחִיתִָ֖ים הֵַָּֽמָׁה׃ 29 נַָּׁחַֹ֣ר מַַּפֶֻ֔חַ *ַּמֵאִשְׁתַם )ַּמֵאֵָ֖שׁ תַַֹּ֣ם( עַֹּּפָָׁ֑רֶת לַַּשָׁוְ א צַָּׁרַַֹּ֣ף צַָּׁרֶֹּ֔וף וְַּרָׁעִָ֖ים לַָּ֥אֹּ נִַּתָָֽׁקוּ׃ 30 כֶַֹּ֣סֶף נִַּמְאֶָׁ֔ס קַָּׁרְאָ֖וּ לַָּׁהֶָ֑ם כִַָּֽי־מָׁאַָ֥ס יְַּהוָָׁ֖ה בַָּׁהֶָֽם׃ פַּ

"The problems of text and interpretation in this verse are daunting."48Fortunately, they do not radically influence the interpretation of the storyline of this poem (vv. 27-30). Jeremiah is addressed by Yahweh. He is commissioned as a metaphorical בָׁחוֹן, assayer, who has to test, evaluate and approve metal, in this case silver. As such, he becomes involved in the smelting process (v. 29). The inference is that the refining process must be thought of as a 'laboratory test site' for samples taken by the assayer (as refiner), away from the production site.49 The general interpretation of the outcome of the process, is that the process itself50 or the ongoing attempt of the refiner51 proves to be futile (lassãw' = in vain), since impurities were not purged.

The 'moral of the story' is literally to be read 'between the lines.' Verses 28 and 30 speak in the third person plural about "reprobate rebels, walking slanderers... destroyers ... (28), who eventually are labelled כֶסֶף נִַּמְאָׁס ("Reject Silver," rejected by Yahweh; 30). The extended metaphor of a parable-like poem conveys the message that Yahweh's people are undergoing his judgement, and finally condemned by him. Jeremiah as 'assayer' is at least probing the moral quality of Judah. But on the basis of a solution-by-vocalisation attempt of the puzzling מאשתם in verse 29a (see below) the prophet as 'refiner' is obviously also an agent of a failed moral reform. The poem moves from Yahweh's commissioning of Jeremiah as assayer-refiner (of Judah) to Yahweh's inevitable judgement of Judah. The possibility of moral reform ends with the verdict in metaphorical terms, numbered in our editions as verses 29-30. The text of verse 29, checked against Codex Leningradensis, reads נָׁחַֹ֣ר מַַּפֶֻ֔חַ מֵַּאֵשׁתַם עַֹּּפָָׁ֑רֶת לַַּשָׁוְ א צַָּׁרַֹ֣ףַּ52צָׁרֶֹּ֔וף וְַּרָׁעִָ֖ים לַָּ֥אֹּ נִַּתָָֽׁקוּ׃ַּ. It is readily accepted that מאשתם is a puzzle whose solution determines the understanding of the first line of the verse. This study adds another interpretational challenge, namely that of לַשָׁוְא.

The apparent original solution to make מאשתם sensible was to associate it with מַפֻחַַּ (bellows), by reading אֵשׁ (fire) in מאשתם. This is achieved by splitting the word in two and vocalising מאש as מֵאֵשׁ; the last two letters as second word is vocalised as תַם (Qerê reading of MT). Of course, the consonantal text had to be copied unaltered, keeping it as one word. This reading strategy is attested in many MSS, LXX and Vulgate53 and used as basis for modern day interpretations, translations and exegesis of the passage. However, the configuration תַם עַֹּּפֶרֶת and the precise MT understanding of תַם in the Qerê reading remains problematic54despite explanations to the contrary. The strategy to remove עֹּפֶרֶת from the words preceding it55 is unsatisfactory.

There is a need for an alternative approach to the problem. Catchwords in the surrounding text appear to be the interpretational key. The passage itself culminates in the catch or key word מאס (reject) twice in verse 30: "They call them rejected silver (כֶַּסֶף נִַּמְאָׁס ) because Yahweh rejected them (כִי־מָׁאַס יְַּהוָׁה בַָּׁהֶָֽם)." In the wider context, this verb occurs twelve times, strategically placed in Jer 233. It occurs in 2:37 (as in 6:30, כִי־מָׁאַס יַּהוה); 4:30; 6:19; 6:30 (2x); 7:29; 8:9; 14:19 (2x); 31:37 and 33:24, 26. It is not hard to see מאס in מאשתם when one realises that the dot on ש is a (later) punctuation mark and that ס and ש are occasionally interchangeable.56 The mysterious word is therefore most probably the verb (qal perf 2 mp), if vocalised and with ש "accurately" punctuated, מְַּאַשְתֶם (= מְַּאַסְתֶם). The line would then read: "The bellows snorted (blew), you rejected (the) lead." The meaning is obvious: as far as the refining process is concerned, all the moving mechanisms are working but the process fails because the cleansing agent is not added. Instead, it is refused, that is, dismissed, declined, repudiated and spurned. The metaphor is that of the refining of silver in which lead was placed with the silver in the crucible and superheated to oxidise the impurities from the silver and eventually separated from the pure silver as flux or slag.57 The saboteurs of the process are the addressees in this verse ("you"), who cause the םַּ ,, both "impurities" and "wicked people" (as the pivotal term making the shift back from metal to people),58 not to be separated.

This reading of the first line is semantically-rhetorically supported by the second line. If the position of לַשָׁוְא, as fixed by the Masoretic taãmê hammiqrã' is maintained, thus, linking לַשָׁוְא to line 2 and separating it from line 1, לַשָׁוְא could either be understood as "in vain..." or "for (the sake of) The Vain One..." The first interpretation underscores the abortive nature of the process, with its negative result: "In vain the refiners fervently keep on refining, evil elements are not shed." The second possibility alludes to the fact that idolatry is at stake in this metaphor: "For the sake of/ bound to The Vain One the refiners fervently keep on refining,59 evil elements are not separated."60

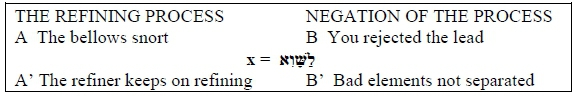

However, poetic features should be considered which might have gone unnoticed by the Masoretes or for which the MT accentuation system was not designed. After all, the Masoretic taãmê hammiqrã' was a choice to link לַשָׁוְא to the second line, with a motivation unknown to us. This means that we should be open to the possibility that לַשָׁוְא could be linked to either the first or second lines. Moreover, it could serve a central overlapping function, linking the two lines with each other. In fact, once לַשָׁוְא is bracketed off from the preceding and succeeding lines, syllable balance and accompanying assonance in the verse become apparent.61 With the assumption that (the isolated) לַשָׁוְא is of special interest, figuratively, the central issue at stake, it should be assigned a central position in the structure of the verse (indicated as x in the diagram). The four cola of the two line verse are then neatly structured as A-B-x-A'-B', where A- A' denotes in positive terms the refining process and B-B' the negation of the refining process. In diagram form:

Within this configuration לַשָׁוְא qualifies both lines. Whereas "The bellows snorted, you rejected the lead in vain" makes no sense within the assumed meaning of the line and the verse, "The bellows snorted, you rejected the lead for the sake of The Vain One..." (causal relationship) is meaningful and serves a resumptive function in line 2, "...for the sake of The Vain One the refiner keeps/kept on refining, the bad elements were not separated."

This, however, does not exclude a covenantal connotation for l-"belonging to, bound to." In fact, support for this reading is given by the key words נתק and מאס. As mentioned, the occurrence of ONa frames Jer 2-33. The phrase כִי־מָׁאַס יְַּהוָׁה occurs in 2:37; 6:30 and 7:29, stating that Yahweh rejected the allies of Judah (Egypt, Assyria) (2:37) and Judah herself (6:30; 7:29). This leads to the question whether Yahweh has totally and finely rejected Judah (הֲמָׁאֹּס מַָּׁאַסְתָׁ אֶַּת-יְהוּדָׁה, 14:19). After the initial כִי־מָׁאַס יְַּהוָׁה (in 2:37), Judah personified as prostitute, is told that "your lovers (allies?) rejected you" מָׁאֲסוּ־בָׁךְַּעֹּגְבִים and want you dead (4:30). The two utterances stating the reason for Yahweh's rejection of his people (6:19 and 8:9) frame the two central statements of Yahweh's rejection in 6:30 and 7:29, namely that Judah (6:19) and her sages (8:9) rejected Yahweh's Torah//Word. The question posed in 14:19 about the reality of Yahweh's rejection62 is taken up in the 'Book of Consolation' in 31:37 and 33:24-26. The question is repeated in another way, starting with the interrogative hã-question to Jeremiah: "Have you not seen what this people say, 'The two families (i.e. Israel and Judah) whom Yahweh had chosen, he rejected...'" (33:24). Yahweh then repeats the assurance given in 31:37, as already implied in 14:19, that he will in the long run never reject "the seed of Israel" (31:36), "the seed of Jacob, and of David, my servant" (33:26).

The explicit mentioning of Yahweh's covenant, covenant breaking (פרר) and covenant loyalty in the last oracles to Jeremiah (33:19-22, 23-25, following the promise of a 'new covenant,' 31:30-33) underlines the fact מָׁאַס is a key covenantal term, the act of terminating the covenant. Yahweh's covenantal relation with his people is the subject matter of at least the entire Jer 2-33.63 In Jer 2:37; 6:27-30 and 7:29, this term occurs in the phrase כִי־מָׁאַס יְַּהוָׁה, marking the termination of the covenant by Yahweh as Overlord. Jeremiah 6:27-30 is pivotal. The location of the term לַשָׁוְא at the centre of the central verse (29) of this pivot strongly suggests that it is an important aspect of the mostly metaphorical descriptions of covenant breaking.

Therefore, to assume that לַשָׁוְא merely indicates the futility of the refinery process (metaphorically the unwillingness of Yahweh's people to keep the covenant) misses the larger picture in Jeremiah of Judah's idolatry, with its emphasis on the attraction to the idols. The view that לַשַָּׁוְא refers to the core problem, the real obstacle, the causal motivation for Yahweh's rejection of his people and his people's initial rejection of his covenantal agreement (Torah, Word) takes this context seriously.

The undoing of the covenant is described by another key term נתק in Jer 6:29. In this text in the nip al form = passive, usually translated (as part of the metaphor) as "bad elements/wicked people were not separated. " This specific form also occurs in Jer 10:20, describing the cords of a tent that are cut (in order for the tent to collapse). In other surrounding texts, pn? appears in the pi 'el (active intensive) form in 2:20; 5:5 and 30:8 in the expression, שׁבר עַֹּּל נִַּתַק מַּוסרותַּ = "To break the yoke, to snap/cut through/totally separate the straps." This is a brief description of yoked animals or slaves that get rid of their yokes, by breaking them and cutting the straps that bind them to their yokes and it serves as a vivid description of the dissolution of a covenant relation. This act is either executed by the overlord (=rejection by Yahweh - Jer 2:20), the vassal (=rebellion by Judah - Jer 5:5) or a foreign overlord (=salvation for Judah/Israel ['Jacob'] by Yahweh, who 'breaks the yoke' binding her/him to anti-Yahweh overlord/s - Jer 30:7-8).

The 'report sequence' of this saying in Jeremiah 2-30 runs parallel to that of מָׁאַס in Jeremiah 2-33 and serves the same function. It indicates first and foremost Yahweh's severance of Judah's/Israel's ties (his rejection of Judah/Israel-Jer 2:20), followed by Judah's/Israel's severance of its covenantal ties to Yahweh, that is, the people's rebellion and rejection of Yahweh (5:5). Finally, Yahweh's action to break the ties of Judah/Israel chained to foreign powers (30:8) is the necessary positive action implicated in Yahweh's promise never to reject his people.

The nip'al forms of נתק in 6:29 and 10:20 are intimately related to the active form of the verb as mentioned and obviously alluding to covenant violation. When it is said that bad elements or people are not "cut off/separated" רָׁעִים לַּאֹּ נִַּתָׁקוּ, the setting is that of covenant violation. However, instead of openly breaking the covenantal bonds, the bonds are held intact while "wicked elements" corrupt the covenant from inside out by refusing the metaphorical "lead" (as refinery catalyst), the purifying discipline (מוֹסֵרוֹת = bonds) of the covenantal teachings (tórá'- 6:19).

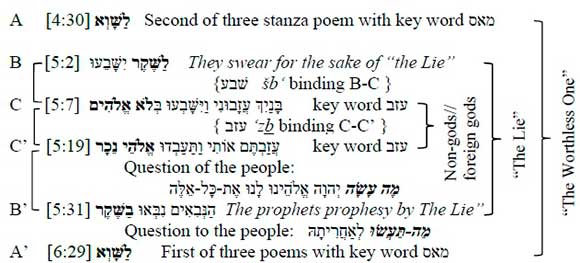

Within the structural layout of Jer 4:5-6:30,64 additional support is evident for the notion that לַשָׁוְא means "for/siding with/bound to The Worthless One," probably referring to Ba'al. Supposed and apparent references to the idols/Ba'al namely לַשָׁוְא(4:30; 6:29), לַשֶקֶר (5:2, 31), לאֹּ אֱַּלֹהִים (5:7) and - אֱלֹהֵי נֵַּכָׁ (5:19) form a fairly clear structured ring composition, marked in the layout as A-B-C-C'-B'-A'. The centre (C-C') is occupied by plural references to 'foreign gods', לאֹּ אֱַּלֹהִים (5:7) and - אֱלֹהֵי נֵַּכָׁר(5:19), immediately framed (B-B') by לַשֶקֶר (5:2, 31), with לַשָׁוְא (4:30; 6:29) as outer frame (A-A'). This 'inclusio of the gods' is fortified by the key words מאס that binds A with A', עזב binding C with C' and y3tö that binds B with C. The interrogative introductions מה עַּשה bind C' with B', respectively as a question of the people [regarding the actions of Yahweh] (5:19) and a question to the people [regarding their actions when the end has arrived for Jerusalem] (5:31).

This 'inclusio of the gods,' framing and integrating Jer 4:5-6:30, becomes visible in the following layout.

The above inclusio strongly suggests

- that לַשָׁוְא in 4:30 and 6:29 refers to the same entity;

- that לַשֶקֶרin 5:2 and 5:31 refers to the same entity;

- that לאֹּ אֱַּלֹהִים in 5:7 and אֱלֹהֵי נֵַּכָׁר in 5:19 refers to the same entity;

- that all singular references (B-B' and A-A', לַשָׁוְא and לַשֶקֶר) are pointing to the same subject;

- that all references refer to the same entity, C-C' in the plural and the surrounding B-B' and A-A' in the singular.

In this textual configuration, the respective brackets of the ring composition mutually confirm the subject matter, which is undoubtedly the non-Yahweh and anti-Yahweh deities, with special reference to the be 'alïm/ba 'al. The derogatory way in which these deities are addressed is apparent in the central term no-gods, לאֹּ אֱַּלֹהִים.

1 Jeremiah 6:29 - Conclusion

The catchwords m's מאס and ntq נתקas terms denoting covenant breach, occurring within the wider text of Jer 2:30/33 is apparently concentrated in 6:2730. This observation opens up the probability that מְַּאַַּשְתֶם in Jer 6:29 should be considered as a misreading of מְַּאַַּשְתֶם = מְַּאַַּסְתֶם ("you rejected"). The said catchwords are key indicators that לַשָׁוְא could allude to Yahweh's opponent, Ba'al. Furthermore, the implications drawn from a structural-poetic layout of 6:29 and that of the wider 4:5-6:30, supported by constant anti-Ba'al polemic, strongly suggest that לַשָׁוְא should be understood as indicating a covenantal relationship with hassãw' and read as "for (the sake of)/siding with/relating to/bound to/belonging to The Worthless One," probably alluding to Ba'al.

E CONCLUSION

1. The interpretation of לשׁוא in Jer 2:30 rests inter alia on the assumption that the grammatical form of sãw' (שָׁׁוְא) seems to be genre bound. Tentative investigation of occurrences of the lexeme in wisdom literature shows that it consistently utilises sãw' in its indefinite form without prefixes, rendered as "in vain." On the other hand, lassaw' (לַשָׁוְא) appears consistently in non-wisdom, cultic-legal texts. The implication for Jer 2:30 is that a wisdom reading of the text conveying Yahweh's attempt at 'pedagogic' correction cannot be maintained. The text clearly functions as a cultic-legal judgement within a covenantal frame of mind. The logic of consistency would imply that none of the לַשָׁוְא referents in Jeremiah can be interpreted as a simple equivalent of שָׁׁוְא. A focused study on the genre specificity of שָׁׁוְא would either confirm or question this stance.

2. If, as assumed, hassãw' refers to a substitute suzerain or "master" (ba 'al) in the god-people covenant, a replacement of Yahweh, it is suggested that the function of the prefixed preposition ל ־ַּ is similar to that in לַיהוה (Isa 44:5; Jer 2:3; 4:4; 5:10 etcetera) with the basic meaning "belonging to, possession of (Yahweh)." The prefix is also grammatically attached to both covenant partners within 'relation' or 'covenant' formulas in the OT/HB and therefore probably a shorthand term for being the vassal of a certain overlord (or suzerain) within a covenantal relationship. However, in this case the allegiance, even the identity of the vassal, has changed from לַיהוה to לַשָׁוְא. This total change of allegiance is apparently the legal basis for the prophetic judgement. With this perspective, לַשָׁוְא would not be a mere pejorative reference to Baal (or any other deity). It would indicate covenantal relationship and status, in this case, the relationship between Judah/Israel and its 'foreign' overlord in opposition to its relationship with Yahweh. The preposition ל־ could therefore be rendered in a variety of ways, ranging from "in the interest of, for the sake of" to "(the status of) belonging to, bound to, attached to" to "being subservient, submissive, obedient to."

3. An intertextual reading of Jer 4:30 with 2 Kgs 9:30 and Ezek 23:40-41 emphasises the polemic setting and metaphoric connotations of the text, thus supporting the notion that לַשָׁוְאcould be "The Vain/W orthless One," probably Ba'al. While the plot of 2 Kings 9 fits that of the three-stanza poem in Jer 4:29-30, the syntax of Ezek 23:40, with special reference to the grammatical function of ל־אשׁר, suggests the same meaning for לשׁוא in Jer 4:30, namely "for the sake of" Jerusalem's idolatrous flirtation with hassãw, "Lord Vanity."65 A relational-covenantal meaning for לשׁוא (in allegiance with hassãw) should, however, not be excluded, since it appears to be motivated by the covenantal foil of the Kings narrative in which Jezebel represents the Baalist antithesis of Israel's covenant with Yahweh.

4. In Jer 6:29 (6:27-30) m 's מאס, paired with ntq נתק- both terms functioning in the semantic field of covenant breach - serves as an interpretational key. Thus m's מאס is a rhetorical marker in Jer 2:30/33 and plays a decisive role in the interpretation of verse 29. The proposal that the puzzling מאשתם actually should be read as מְַּאַסְתֶם opens the option that לַשָׁוְא could allude to Ba'al. Furthermore, the implications drawn from a structural-poetic layout of 6:29 and that of 4:5-6:30 (the pivot of an even wider text span), supported by constant anti-Ba'al polemic, strongly suggest that לַשָׁוְא is an indicator of a covenantal relationship with hassãw' , and read as "for (the sake of)/siding with/relating to/bound to/belonging to The Vain One," probably alluding to Ba'al.

5. To summarise, the traditional stance that לשׁוא denotes futility, could be refuted by a search for intertexual clues (Ezek 23; 2 Kgs 9 -> Jer 4:30), alertness to recurring key words and chiastic patterns on a micro and macro level (Jer 6:29; 4:5-6:30 as pivot of the surrounding text) and the tentative observation (to be confirmed by further study) that שׁוא (futility, "in vain") only occurs in wisdom literature, whereas cultic-legal texts with a covenantal background, under which the Jeremiah texts fall, make use of the prepositional prefixed definite form לשׁוא. The notion that the preposition ל־ is - apart from the meaning "for, for the sake of" - a signifier of covenantal relationship, was deducted from a variety of angles within the MT Jeremiah text. Therefore it can be assumed that לַשָׁוְא is more than a pejorative reference to Baal (or any other deity), but indeed a label of Israel's ties to an overlord/overlords in all respects contra and anti-Yahweh.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Academic-bible.com: The Scholarly Bible Portal of the German Bible Society. Cited 1 November 2020. Online: https://www.academic-bible.com/en/online-bibles/septuagint-lxx/read-the-bible-text. [ Links ]

Barré, Lloyd M. The Rhetoric of Political Persuasion: The Narrative Artistry and Political Intentions of 2 Kings 9-11. Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 20. Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1988. [ Links ]

Beuken, W.A.M. Jesaja deel IIA, De Prediking van het Oude Testament. Nijkerk: Callenbach, 1979. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel I. Ezekiel Chapters 1-24. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997. [ Links ]

Bright, John. Jeremiah: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible 21. Second Edition, 13th print. Garden City: Doubleday, 1978. [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver and C. A. Briggs. A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. 7th edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. To Pluck up, to Tear down: A Commentary on the Book of Jeremiah 1-25. International Theological Commentary Series. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988. [ Links ]

Compton, R. Andrew. "Deixis Variation as a Literary Device in Ezekiel: Utilizing an Oft Neglected Linguistic Feature in Exegesis." Mid-America Journal of Theology 28 (2017): 77-107. [ Links ]

Craigie, Peter C., Page H. Kelly and Joel F. Drinkard (Jr.). Jeremiah 1-25. Word Biblical Commentary 26. Dallas: Word Books, 1991. [ Links ]

Darr, Katheryn Pfisterer. "Ezekiel's Justifications of God: Teaching Troubling Texts." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 17/55 (1992): 97-117. [ Links ]

De Blois, Reinier and Enio R. Mueller, eds. Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew. United Bible Societies 2000-2021. Cited 13 January 2021. Online: https://semanticdictionary.org/semdic.php?databaseType=SDBH. [ Links ]

Feuer, Rabbi Avrohom Chaim. Tehillim: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources. ArtScroll Tanach Series 2. New York: Mesorah Publications, 1995. [ Links ]

Gesenius, H. W. F. Gesenius' Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, 1846. Cited 23 September 2020. Online: http://www.tyndalearchive.com/TABS/Gesenius/index.htm. [ Links ]

Greenberg, Moshe. Ezekiel 21-37. Anchor Bible 22A. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

Jindo, Job Y. Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered: A Cognitive Approach to Poetic Prophecy in Jeremiah 1-24. Harvard Semitic Museum Publications / Harvard Semitic Monographs 64. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2010. [ Links ]

King, Andrew. "Did Jehu Destroy Baal from Israel? A Contextual Reading of Jehu's Revolt." Bulletin for Biblical Research 27/3 (2017): 309-332. [ Links ]

Leningrad Codex Tanach Manuscript. Black and White Scan. Cited 30 October 2020. Online: https://www.tanachonline.org/manuscripts. [ Links ]

Lisowsky, Gerhard. Konkordanz zum Hebräischen Alten Testament. 2nd edition. Stuttgart: Würtembergische Bibelanstalt, 1958. [ Links ]

Loewenclau, Ilse von. "Zu Jeremia 2:30." Vetus Testamentum 16/1 (1966): 117-123. [ Links ]

Lundbom, Jack R. Jeremiah 1-20: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible 21A. New York: Doubleday, 1999. [ Links ]

__________________. Jeremiah 37-52: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible 21C. New York: Doubleday, 2004. [ Links ]

McKinlay, Judith E. "Negotiating the Frame for Viewing the Death of Jezebel." Biblical Interpretation 10/3 (2002): 305-323. [ Links ]

Odell, Margaret S. Ezekiel. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary. Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2005. [ Links ]

Paul, Shalom M. Isaiah 40-66, Translation and Commentary. Eerdmans Critical Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012. [ Links ]

Reiterer, Friedrich V. "שָׁׁוְא sãw' worthless." Column 447-460 in volume 14 of Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Edited by G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren and Heinz-Josef Fabry. Translated by Douglas W. Stott. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, Rolf. The Covenant Formula: An Exegetical and Theological Investigation. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998. [ Links ]

Retief, C. Wynand. "The Deity in the Definite Article: lassãw' and related terms for Ba'al in Jeremiah." Old Testament Essays 33/2 (2020): 323-347. [ Links ]

Sawyer, John F.A. "שָׁׁוְא sãw' Trug." Column 882-884 in Theologisches Handwörterbuch zum Alten Testament, Band II. Edited by Ernst Jenni and Claus [ Links ]

Westermann. München: Chr. Kaiser Verlag, 1976. Shepherd, J. "שָׁׁוְא sãw' (#8736)." Pages 53-55 in Volume 4 of New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis. Edited by Willem VanGemeren. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1997. [ Links ]

Shields, Mary E. Circumscribing the Prostitute: The Rhetorics of Intertextuality, Metaphor and Gender in Jeremiah 3.1-4.4. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 387. London: T&T Clark International, 2004. [ Links ]

Thompson, John A. The Book of Jeremiah. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980. [ Links ]

Van den Eynde, Sabine. "Covenant Formula and r'~Q: The Links between a Hebrew Lexeme and a Biblical Concept." Old Testament Essays 12/1 (1999): 122-148. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, Christo H. J., Jackie A. Naudé and Jan H. Kroeze. A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar. Second Edition. 2nd print. London: T&T Clark/ Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018. [ Links ]

Van Selms, A. Jeremia deel I. De Prediking van het Oude Testament. Callenbach: Nijkerk, 1980. [ Links ]

Weisman, Ze'ev. Political Satire in the Bible. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, Walther. Ezekiel 1. A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1979. [ Links ]

Submitted: 29/08/2021

Peer-reviewed: 05/11/2021

Accepted: 22/11/2021

C. Wynand Retief, University of the Free State, E-mail: cwretief@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6872-314X.

1 This notion, and the assumption that ìùÑåà is a reference to prohibited objects of worship within cultic-legal texts, have to be corroborated.

2 C. Wynand Retief, “The Deity in the Definite Article: la...w. and related terms for Ba‘al in Jeremiah,” OTE 33/2 (2020): 323–347.

3 "The remaining texts where lassaw' and lasseqer/basseqer appear as well as excerpts from Jeremiah 23:9-40 should either strengthen the hypothesis, or show up its problematic side." See Retief, "The Deity in the Definite Article," 343-344.

4 Jerry Shepherd, "שָׁׁוְא saw' (#8736)" in volume 4 of NIDOTTE (ed. Willem VanGemeren; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1997), 53-54, notes that "seems to have two interrelated senses, namely ineffectiveness and falseness, the latter probably being derived from the idea that hopes and expectations prove false when placed in persons and things that are ineffective and therefore untrustworthy... In a few places the term seems to denote ineffectiveness without necessarily implying deceit or falsehood... In most places, however, the idea of falsehood or deceit is present, and perhaps primary." The two senses of the term are expressed in the titles of the articles of respectively Friedrich V. Reiterer, שָׁׁוְא saw' worthless;" Column 447-460 in volume 14 of TDOT (ed. G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren and Heinz-Josef Fabry; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004) and John F.A. Sawyer, "שָׁׁוְא saw' Trug;' Column 882-884 in THAT (ed. Ernst Jenni and Claus Westermann; Band II; München: Chr. Kaiser Verlag, 1976).

5 Jack R. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Anchor Bible 21A; New York: Doubleday, 1999), 289.

6 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 249.

7 Job Y. Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered: A Cognitive Approach to Poetic Prophecy in Jeremiah 1-24 (HSMP/HSM 64; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2010), 179.

8 As illustrated by the cyclical structure of the chapter, see Job Y. Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered, 181-182.

9 Craigie et al. remark that the second person masculine plural is used in verses 2930/32, as was the case in verses 4-13, which contends for a connection between these passages. See Peter C. Craigie, Page H. Kelly and Joel F. Drinkard (Jr.), Jeremiah 125 (Word Biblical Commentary 26; Dallas: Word Books, 1991), 40.

10 John Bright, Jeremiah: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Anchor Bible 21; Second edition; 13th print; Garden City: Doubleday), 1978. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20. John A. Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah (New International Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), 1980.

11 The stance of Lundbom is interesting, although somewhat puzzling. While having a sharp eye for allusions to Baal elsewhere, he consistently translates lassãw' as "in vain" (in Jer 2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 18:15; 46:11). See Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20 and Jack R. Lundbom, Jeremiah 37-52: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Anchor Bible 21C; New York: Doubleday), 2004.

12 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 289.

13 Pädagogische Schlagen; see Ilse von Loewenclau, "Zu Jeremia 2:30," VT 16/1 (1966): 119.

14 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 289.

15 See, for example, Ilse von Loewenclau, "Zu Jeremia 2:30," VT 16/1 (1966), 119123, for critical remarks on אֶת־בְנֵיכֶם and כְאַרְיֵה מַַּשְׁחִית. Her proposed emendations to posit a changed text need not be agreed upon.

16 A. van Selms, Jeremia deel I (De Prediking van het Oude Testament; Callenbach: Nijkerk, 1980), 57, notes that nebi'êkem represent the true prophets, sent to Israel by Yahweh, unlike the false prophets of 2:8, 26. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 290, summarises the tradition that Israel killed its prophets, starting with Elijah.

17 Gerhard Lisowsky, Konkordanz zum Hebräischen Alten Testament (2nd edition; Stuttgart: Würtembergische Bibelanstalt, 1958), 1406-1407.

18 Cf. Prov 30:8; Job 7:3; Pss 119:37; 127:1, 2 as well as Ps 60:13 (=108:13) and 89:48 which could be labelled as creation/life cycle texts (where saw' refers to death).

19 saw' occurs frequently as the absolute noun in a genitive construct, with an attributive adjectival function, even in cultic-legal texts, for example, Isa 1:13, מִנְחַת־ שָׁׁוְא= worthless grainofferings; Deut 5:20 עֵד־שָׁׁוְא = false witness (perjury).

20 Generally translated as "the house," the definite form without the article is assumed in poetic texts. The connection to 2 Sam 7 where Yahweh promises to build "a house" (בית), that is, a royal dynasty for David, starting with Solomon, should not go unnoticed in this "Song of Ascents of Solomon." The Rabbis (Ibn Ezra, Radak, etc.) noticed the connection to Solomon and the first temple but concentrated on Solomon's marriages and his temple building and apparently not on Yahweh's promise in 2 Sam 7. See Rabbi Avrohom Chaim Feuer, Tehillim: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources (ArtScroll Tanach Series 2; New York: Mesorah Publications, 1995), 1542-1543.

21 To be determined below.

22 F.W.H. Gesenius, Gesenius' Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament,, 1846 [cited 23 September 2020]. Online: http://www.tyndalearchive.com/TABS/Gesenius/index.htm, 442.

23 Christo H.J. Van der Merwe, Jackie A. Naudé and Jan H. Kroeze, A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar (Second edition; 2nd print; London: T&T Clark, 2018), 357.

24 Shalom M. Paul, Isaiah 40-66, Translation and Commentary (Eerdmans Critical Commentary; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 228, referring to the lamekel inscriptions on many shards of pottery and seals discovered in Israel. Based on the double occurrence of lyhwh in Isa 44:5, Beuken remarks "Zo horen vs. 5a en vs. 5b bij elkaar als het mondelinge en het schriftelijke gedeelte van een tweeledige akte, waardoor personen in het bezit van YHWH overgaan" (own emphasis). See W.A.M. Beuken, Jesaja deelIIA (POT; Nijkerk: Callenbach, 1979), 199.

25 See Rolf Rendtorff, The Covenant Formula: An Exegetical and Theological Investigation (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998), 93-94. Sabine Van den Eynde, "Covenant Formula and ברית: The Links between a Hebrew Lexeme and a Biblical Concept," OTE 12/1 (1999): 124.

26 A focused study on the possible covenantal reference of ליהוה in Jeremiah could substantiate the proposal.

27 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 364.

28 The gender of the addressee is feminine, as indicated by the pronoun and the description of the character, while שָׁׁדוּד is masculine (lacking in LXX). Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah, 231.

29 Ibid., 232. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 369.

30 Van Selms, Jeremia Deel I, 94.

31 Cf. Walther Zimmerli, Ezekiel 1, A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1979), 492.

32 Moshe Greenberg, Ezekiel 21-37 (AB 22A; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 490-491.

33 Block, Ezekiel Chapters 1-24, 756, 760.

34 Margaret S. Odell, Ezekiel (SHBC; Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2005), 305-306.

35 R. Andrew Compton, "Deixis Variation as a Literary Device in Ezekiel: Utilizing an Oft Neglected Linguistic Feature in Exegesis," Mid-America Journal of Theology 28 (2017): 77-107.

36 Compton, "Deixis Variation," 105.

37 Ibid., 104.

38 Katheryn Pfisterer Darr, "Ezekiel's Justifications of God: Teaching Troubling Texts," JSOT17/55 (1992): 108.

39 Ze'ev Weisman, Political Satire in the Bible (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998), 22, already noted the similarity between 2 Kgs 9:30 and Jer 4:29-31. See Judith E. McKinlay, "Negotiating the Frame for Viewing the Death of Jezebel," Biblical Interpretation 10/3 (2002): 306 fn 4.

40 The rendition of is motivated by the narrative line which starts in verse 29, the unusual masculine form within the feminine forms and one of the Arabic meanings of sdd "to rush on an enemy." See Gesenius, Gesenius' Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon, 806.

41 Usually translated in Jer 4:30 as "your lovers." LXX erastai, in classical Greek the senior partner in a pederastic relationship, therefore, craving for and acting out his sexual desire towards a boy (ped). All other occurrences of עגב are in Ezek 23 (vv. 5, 7, 9, 12, 16, 16, 20) where Oholah (Samaria) and Oholibah (Jerusalem) give themselves over in desire to the Assyrians, etcetera (עגב used in the metaphoric sense of associating with foreign nations, including their idols). See Reinier de Blois and Enio R. Mueller, ed., Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew, United Bible Societies 2000-2021. n.p. [cited 12 January 2021] Online: https://semanticdictionary.org/semdic.php?databaseType=SDBH.

42 The so-called 'woman in the window' motif is too varied and undefined to support the notion that it would paint Jezebel as prostitute. See Andrew King, "Did Jehu Destroy Baal from Israel? A Contextual Reading of Jehu's Revolt," Bulletin for Biblical Research 27/3 (2017): 326 fn. 88.

43 According to King, "Did Jehu Destroy Baal from Israel?" 326, Jezebel's words "are an attempt to associate Jehu, who was divinely elected, with a usurper whose end came by suicide (cf. 1 Kgs 16:8-20)." Cf. Judith E. McKinlay, "Negotiating the Frame for Viewing the Death of Jezebel," Biblical Interpretation 10/3 (2002): 306. King contends the stance of L. Barré that the preparation and appearance of Jezebel in the window is her attempt to seduce Jehu. See Lloyd M. Barré, "The Rhetoric of Political Persuasion: The Narrative Artistry and Political Intentions of 2 Kings 9-11," (CBQ MS 20; Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1988), 76-81.

44 The causal relationship function of l- seldom occurs, but is here determined by the context. See Van der Merwe, Naudé and Kroeze, Biblical Hebrew, 357.

45 The 'plot' of the narrative construed by stanzas 1-3 makes for identification of the subject with Jerusalem. She is called "daughter Zion" in verse 31 (Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah, 232) and the description of evacuation of all cities, except the subject (vv. 29-30), corresponds with Sennacherib's Blitzkrieg in 701, when all Judean cities were evacuated but Jerusalem (Lundbom, 367). Ezekiel 23 explicitly identifies the prostitute who prepares herself for her clients as Jerusalem.

46 The expression עֹּגְבִים could be an allusion to the nations that would invade Jerusalem according to 2 Kgs 24:2. See Van Selms, Jeremia Deel I, 94. In the light of Jerusalem's affair with "other gods" אלהים אַּחרים, "The Baals" (הבעלים) and allusions to Baal in the plural, these deities are not to be excluded as עגבים. Cf. עַּגב H5689 - to lust after (someone) > to associate with (a foreign nation and their idols) (Ezek 23:5; 23:7, 12, 16, 20) in Reinier De Blois and Enio R. Mueller, eds., Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew, United Bible Societies 2000-2021. n.p. [cited 15 January 2021]. Online: https://semanticdictionary.org/semdic.php?databaseType=SDBH.

47 Inspired by Bright's "Lord Delusion" (for הַהֶבֶל, 2:5) and "Lord Useless" (for לאַּיועל, 2:11). See Bright, Jeremiah, 15.

48 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 450.

49 See Craigie et al, 110-111.

50 Rendering צָׁרַף צַָּׁרֹּוף as qal perf + qal infinitive absolute, "the refining went on/continues" (Lundbom, Craigie et al., also Bright). The semantic-pragmatic functions are either to confirm the factuality of the event or specify its extreme mode. See Van der Merwe, Naudé and Kroeze, Biblical Hebrew, 179-180.

51 Reading צָׁרֹּוף as nomen agentis (refiner) like בָׁחוֹן (assayer, v. 27). See Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah, 265.

52 The vocalisation of מַּאשתם as checked against a scanned copy of Codex Leningradensis. "Leningrad Codex Tanach Manuscript. Black and White Scan." n.p. [cited 7 October 2020]. Online: https://www.tanachonline.org/manuscripts.

53 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 451.

54 The term עֹּפֶרֶת, a femine subject, is predicated by a masculine verb תַם, which is foreign to its usual cultic context and has to be 'bent' to mean either "consumed" or "remained intact." See Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 451.

55 So Thompson, with reference to G.R. Driver, "Two Misunderstood Passages of the OT," JTS 6 (1955): 82-87. See Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah, 265.

56 There are numerous examples of ש in Middle Hebrew, written as ס in "New" or Late Hebrew. See the rubrics starting with these letters in HELOT, 697-706, 959-973. Examples of occurrences of ש in words otherwise written with O, but not to be explained as chronological developments, are [מַשְמֵר] in Eccl 12:11, compared to [מַסְמֵר] in Isa 41:7, Jer 10:4, 1 Chron 22:3 and 2 Chron 3:9 (HELOT, 702, 971); שֻכוֹ in Lam 2:6, otherwise סֹּךְ ,ַּסֻכָׁה (HELOT, 968); שִכְלוּת in Eccl 1:17 = סִכְלוּת in Eccl 2:3, 12, 13 (HELOT, 698, 968). Thus, ש instead of the usual ס in מִשְפַח in Isa 5:7 is chosen for assonance with מִשְׁפַט (HELOT, 705).

57 See Bright, Jeremiah, 49. Cited by Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah, 266-267.

58 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 451.

59 This rendition is an effort to capture both possibilities expressed by צָׁרַף צַָּׁרֹּוף as qal perf + qal infinitive absolute, as well as reading צָׁרֹּו as nomen agentis (refiner) like בָׁחוֹןַּ (assayer, v. 27). See footnotes 30 and 31.

60 The verb קַּ (here and in 10:20 in the nip 'al form = passive) is used in Jeremiah 10:20 (cords of tent broken), and 2:20, 5:5, 30:8 in the saying ר עַֹּּל נִַּתַק מַּוסרותַּ = "To break the yoke, to snap/cut through/totally separate (pi'elform) the straps." This is a brief description of yoked animals or slaves that get rid of their yokes, by a breaking of the yokes and cutting of the straps that bind them to their yokes, to express in picturesque language the dissolution of a covenant relation. The severance of the ties (and breaking of the yoke) is either committed by the overlord (=rejection - Jer 2:20 by Yahweh), the vassal (=rebellion - Jer 5:5 by Judah) or an outside overlord (=salvation - Jer 30:8 by Yahweh for Judah).

61 Initial <â-a> of נָׁחַר מַַּפֻחַַּ with צָׁרַף צַָּׁרוֹף and initial <o> of עֹּפָׁרֶת with אֹּ נִַּתָׁקוּ .

62 In this specific context, the infinite absolute + finite verb מָׁאֹּס מַָּׁאַסְתַָּׁ confirm the actuality of an event, of which the potential realisation is sometimes strongly denied in rhetorical questions. See Van der Merwe, Naudé and Kroeze, Reference Grammar, 179-180. As 14:19 is a threefold rhetorical question in the hã... im...maddúa (If... if... so why?) form (unique to Jeremiah) the first two questions require 'no' answers, according to Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 271 (commentary on Jer 2:14). Lundbom refers in his commentary on 14:19 to the last (open-ended) question of Lam 5:22, "Have you utterly rejected us?", stating "Whatever the short-term answers to questions of rejection may have been, the long-term answer was an unambiguous "No" (31:37; 33:24-26; cf. Rom 11:1)." See Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 713.

63 Mary E. Shields, Circumscribing the Prostitute: The Rhetorics of Intertextuality, Metaphor and Gender in Jeremiah 3.1-4.4 (JSOT Supplement Series 387; London: T&T Clark International, 2004), 27f, 165, sees the intertextuality between Jer 3:1 (a pivotal text in Jer 2-33) and Deut 24:1-4 as "the legal/covenantal ideal," one of four ideals interwoven in Jer 3:1-4:4 "to present a mutually reinforcing persuasive picture of return."

64 By many commentators taken as a “foe cycle” of oracles, its end marked by the petu.â’ at the end of 6:30. So Bright, Jeremiah, 28–51, Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah, 217; Walter Brueggemann, Jeremiah 1–25, 49ff. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1–20, 446ff takes 6:27–30 as introduction to 6:27–8:12 because of the catchword m’s in the poems in 6:27–30; 7:29 and 8:4–9. As indicated above, m’s also appears in preceding and succeeding texts in Jer 2–33, which relativises Lundbom’s stance.

65 Inspired by Bright's "Lord Delusion" (for הַהֶבֶל, 2:5) and "Lord Useless" (for לאַּיועל, 2:11). See Bright, Jeremiah, 15.