Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 n.3 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n3a11

ARTICLES

Rhetoric of Honour and Shame in Understanding the Fate of the King of Tyre in Ezek 28:1-19

Bin Kang

Biblical Seminary of the Philippines

ABSTRACT

While the oracles against Tyre are often understood in terms of Tyre's political and economic relationship with Judah and advocate a sovereign God who oversaw the destiny of foreign powers, this article explores the oracles against Tyre, particularly Ezek 28:1-19, from the perspective of honour and shame in an ancient Mediterranean context. It finds that the rhetoric of the contrasting notion of honour and shame plays an important role in understanding the rise and fall of the king of Tyre in Ezek 28:1-19. The fluctuation of honour and shame with regards to the Adamic identity of the king of Tyre in the passage serves to enhance in a forceful and sarcastic way the reality of the king's mortal human fate. I propose that the purpose of this oracle, in light of the honour/shame rhetoric, is to address the suffering Israelites in exile with comfort and assurance in that crucial moment of history.

Keywords: Honour, Shame, Rhetoric, (king Of) Tyre; Oracle; Ezekiel; Exile; Comfort

A INTRODUCTION

In comparison with what other prophets have briefly said about Tyre (Amos 1:910; Isa 23:1-18; Joel 3:4-8; Zech 9:2-4), Ezekiel surprisingly and patiently spends almost three chapters (Ezek 26-28) in focusing on this city-state. Ezekiel certainly says more about this location than any other prophet. Moreover, compared to oracles against other nations1 in the book, Ezekiel devotes more time to Tyre than any other nation besides Egypt (Ezek 29-32). In response to this abnormality, John T. Strong states: "One of the most puzzling aspects of these oracles is the motivation behind them."2 Traditionally, scholars have often dealt with this puzzle from the perspective of Tyre's political and economic relationship with Judah.3

From such a perspective, many scholars have proposed that Ezek 28:119, as part of the oracles against Tyre in chs. 26-28, served to emphasise God's sovereignty over the course of history by Tyre's rise and fall. For instance, Boadt concludes that the purpose of the oracle against Tyre is "to re-establish the authority and power of Yahweh as the only God, more than the equal of Baal or Marduk or Amon or of any other high god of the ancient world. Thus the mythological language is not merely mythopoetic, but consciously attacks the common Near Eastern divine myths as real threats to the faith of Israel."4

Likewise, Crouch points out that the oracle used cosmological mythological motifs to affirm the power of Yahweh as divine king and creator rather than that of Marduk.5 Thus, it may have driven exiled Israel to bow humbly before God and worship him for his supreme control over the destiny of all nations, not only Judah.

The contributions of their studies do deepen our comprehension of the quest for Ezekiel's motivation for his condemnation of Tyre. Nevertheless, the answer does not give a satisfying or full explanation of Ezekiel's rhetorical purpose, that is, the interaction between the author, the text and the original readers.6 After all, Ezekiel also addressed other nations7 in speaking about God's sovereignty over them through the instrumentality of his divine judgment but none of these nations drew the attention that did Tyre.

How would the oracles against Tyre be relevant to the exiled Israel in their context? In response to such a question, Allen comments:

Ezekiel's necessary task was to counter a mood of optimism among the Jewish exiles. Stunned as they were at Jerusalem's fall, they were evidently clutching at a straw offered to them by their fellow exiles from Tyre. With a shift of confidence, they imagined that Tyre's resistance to the besieging Babylonians might mean a turning of the tide for them.8

The question may also be answered the other way round. In view of Tyre's shameful insult regarding Jerusalem's fall (Ezek 26:2), it may be more likely that the suffering exiled Israel would anticipate a quick finish of Tyre rather than her deliverance. A shamed and fallen Tyre was the vindication they wanted to see.9The overall mood of judgment against Tyre and the nature of lamentation also support such an understanding.

What the prophet represented might not be a shallow spirit of national patriotism but a reflection of God's divine retribution on an enemy that humiliated God's people in the midst of their blood and tears. The oracle of judgment, immediately following Tyre's taunt over Judah, was a clear message God sent to his people and all other nations. Jerusalem belonged to Yahweh and whoever touched her touched the apple of his eye.

That being said, I would like to argue in this article that the rhetoric of the contrasting notions of honour and shame plays a significant role in understanding the rise and fall of the king of Tyre in Ezek 28:1-19, a passage that serves as a highpoint in Ezekiel's overall oracle against Tyre. To be more specific, the fluctuation of honour and shame with regards to his Adamic identity in the passage enhances in a forceful and sarcastic way the reality of the king's mortal human fate. Ezekiel's dramatic and satirical interplay of honour and shame on the Tyrian king's doomed human fate in 28:1-19 brought comfort and assurance to the suffering shamed exilic community. Foreign power, whatever an honourable position it was once entitled to, was bound to perish in shame as it inflicted ridicule on God's people.

B ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN VALUES OF HONOUR AND SHAME

Honour and shame, as a binary opposite pair, are often viewed as representing important social cultural values of the ancient Mediterranean world.10 Malina defines honour as "the value of a person in his or her own eyes (that is, one's claim to worth)plus that person's value in the eyes of his or her social group."11This seems to be a good definition, as it involves both the personal and communal acknowledgement of such a value. Honour, as a positive value, can be expressed through the acquisition of wealth, a high position and status, the adherence to good morality, diligence in works, hospitality to visitors, victory in wars, the granting of divine blessings, the bearing of children and having a good name (reputation).12 Shame, possibly paired binarily with honour, can be defined as a failure to reach such expected values.13

The value of honour and shame is embedded in biblical culture. The book of Ezekiel is full of this imagery. The glory of the Lord (כבוד יהוה), as God's very substantial attribute, is a repeated motif that runs throughout the book (1:28; 3:12, 23; 10:4, 18-19; 11:23; 43:4-5; 44:4). The word "glory" (כבוד) could also be translated as "honour." Constructing an emic view of "honour" is also inseparable with the use of כבד in the book.14 Other conspicuous vocabulary terms, common in wisdom literature denoting honour and occurring in Ezek 28:1-19, are חכמה (wisdom) and חיל (wealth).15 Honour, wealth and wisdom are relationally inseparable.

The notion of shame is more prevalent than honour in the Old Testament. In the book of Ezekiel, frequent uses of the words בוש I, כלם,16,קו alongside withחלל I (profane), תועבה(abomination) and טמא (uncleanness),17 distinctly connote shame. Moreover, מרה (rebellious) is often used in Ezekiel to refer to language of defilement; just as a son shames his parent by rebelling against their authority and teaching (Deut 21:18-21), so also the "rebellious house" of Israel shames the Lord their God.18 Language of shame is also commonly depicted in Ezekiel's "sign-acts"19 and at important junctures in the book.20 The connotation of shame also permeates the oracles of Tyre (Ezek 26-28).

C AUDIENCE OF THE BOOK OF EZEKIEL

The book of Ezekiel ties the prophet to the Babylonian exiled community by the Chebar canal (Ezek 1:1; 3:15) from where he is called by God in visions and begins his ministry. Ezekiel identifies himself as part of the exile; his consistent use of chronological order dating from the exile of king Jehoiachin21 (Ezek 1:2; 8:1; 20:1; 24:1; 29:1; 30:20; 31:1; 26:1; 33:21; 32:17; 40:1) also reflects the reality of the exile he faced continually.

It is generally agreed that Ezekiel's primary audience was the community of Israelites exiled in Babylon.22 The exile brought shame, disgrace, affliction and grief to the exiled Israelites. The fall of Jerusalem is the watershed in the book. Prior to the fall, Ezekiel's message mainly concerned prophecies of judgment against Judah (Ezek 4-24). The continuous practice of idolatry and abominations in the Jerusalem temple aroused YHWH's jealousy. Such a betrayal of God's covenant compelled God to remove his presence from Jerusalem. Ezekiel's purpose is to explain to the Babylon exiles that the reality of the exile is due to Judah's own sinful nature and the blaming finger should not point to an impotent God though it could be said that Ezekiel's message concerning a hopeless Jerusalem may be transferred to Israelites in Judah,23 that is, really beyond Ezekiel's original intention.

When the destiny of Jerusalem was determined and God decided to judge the nation by sending the people into exile, Ezekiel's message shifted to the judgment of other enemy nations (Ezek 25-39) as an expression of comfort to the Babylonian exiles.24 The oracles against Tyre (Ezek 26-28) are framed as part of God's judgment on foreign powers and the intended audience is none other than the Babylonian exiles.25

D HONOUR AND SHAME IN THE ORACLE AGAINST KING OF TYRE IN EZEK 28:1-19

Ezekiel 28:1-19 forms two clear units. The first unit (vv. 1-10) is a judgment speech against the leader of Tyre and the second (vv. 11-19) is a lament over the king of Tyre. Text divisions that reflect the interchange of Tyre's honour and shame in this passage can be shown as follow:

A. The King's Self-boasting Honour as a God (28:1-5)

B. The King's Death in Shame as a Mortal Man (28:6-10)

A1. The King's Past Glory as an Adamic Figure in Remembrance (28:1115)

B1. The King's Annihilation in Shame as an Expelled Adamic Ruler (28:15-19)

The above outline will guide my investigation of the fluctuation of the king's honour and shame in this article. Before the study of our texts, I will discuss briefly the relationship between Ezek 28:1-19 and chs. 26-27.

1 Tyre's Honour and Shame in Ezek 26-27

The honour or shame of Israel as a nation was bound up with its relationship with the neighbouring nations.26 Surely, Tyre's insult against Jerusalem (Ezek 26:2) only aggravated Judah's shame at the time of the destruction of the city but the Lord God, who stood behind Israel as a national God, also suffered shame for his name when Judah was humiliated. Israel suffered God's punishment and discipline because of her sins but this did not mean that God would tolerate other nations humiliating Israel without a cause and shaming his people.27 There was still a binding covenant relationship (16:59-63) between Israel and the Lord their God.28 The Lord would never cut off his relationship with Israel despite her unfaithfulness.

The oracle of judgment against Tyre was a clear message from God- Tyre was doomed. The shame Tyre hurled at Judah would be returned to her and even more. Tyre's shiny fame would go into oblivion and the only remembrance of its name would be "a bare rock, a place for the spreading of nets" (26:5, 14).29Tyre's shame will overshadow its previous honour.

In ch. 27, Ezekiel depicts Tyre as a merchant ship trading in the heart of the seas and he prolifically portrays Tyre's self-claimed beauty (יפ, v. 2, 4, 11), splendour (הדר, v. 10) and glory. Tyre's prosperity and magnificence are vividly displayed.30 Then, the glorious "ship" unexpectedly turned into the catastrophe of a shipwreck and all of Tyre's riches, splendour and glory sank together with her (27:32-33).

In Ezek 26, the rhetoric of honour and shame plays a significant role in understanding the fall of Judah and the prophecy against Tyre. In continuity, Ezek 27 strategically serves to intensify Tyre's shamed image by a dramatised turnover from a glorious merchant ship to a wrecked sinking ship. The lament in ch. 27 was orchestrated in continuity with ch. 26 to speak satirically against Tyre. The prophet was intentional in his rhetorical tactics to shame Tyre. Tyre swung from her greatest honour to her most humiliating shame.31

Among the many nations he prophesied against, why does Ezekiel place so much emphasis on Tyre? Obviously, Tyre was not the only nation that shamed Israel at her destruction.32 To answer the question, two things may be taken into consideration: (1) Internally, Tyre's exceptional hubris and arrogance were indeed evil in nature; for this reason, ch. 28 turned into a lengthy analysis of the justification of her fall. (2) Externally, with Tyre as a city-state well known as a commercial centre of power and influence, her downfall would send a clear message to the international communities; whoever shamed Israel would be judged with even more shame.33 Indeed, such a message spoke more forcefully to a suffering exiled Israelite community and would be more relevant to their situation. A doomed Tyre would grant comfort and assurance to the shamed Israel in an alien land. It may also explain why Ezekiel differs from all other prophets in his address to Tyre; he spoke more contextually to a shamed exilic community in which he served.

2 Interchange of the Tyrian King's Honour and Shame in Ezek 28:119

If ch. 26 starts the prophecy against Tyre and ch. 27 gives the account of how Tyre would fall, then ch. 28 focuses on why the king of Tyre (representing the country) was bound to fall. Particulars are given to descriptions of the king's arrogant godlike claims and his boasting about wisdom and wealth. In light of the unified features of these three chapters, my argument is that the rhetoric of honour and shame remains a prominent motif in understanding the oracle against the king of Tyre in 28:1-19, as it serves to enhance in a forceful and sarcastic way the reality of the king's mortal human fate and further extends comfort to the suffering Israelites in exile.

1a The King's Self-boasting Honour as a God (28:1-5)

The Tyrian king is first accused of arrogance and it is expressed in his self-proclamation as a god (28:2). This is an example of royal hyperbole.34 A royal figure, given his superior status and rule can, by the metaphor of hyperbole, be possibly seen as/like a god (Exod 7:1, Ps 8:5).35 If the setting of this oracle was the long siege of Tyre, a withstanding of Nebuchadnezzar's attack (29:18) and even Assyria's earlier attacks may explain better why the king of Tyre was so puffed up.36

God's immediate critique of the challenge was, "But you are a man (אדם), not a god (אל), though you make your heart like the heart of a god" (28:2). One should not overlook the significance of this simple statement. The king, considered a man and not a god, reappears in verse 9. This satirical statement, as an objection to the king's divine claim, is the thesis of the whole oracle (28:119). It governs the first unit of the judgment speech (vv. 1-10) and, by extension, significantly impacts the development of the second unit of lament (vv. 11-19).37The king of Tyre, as a man (אדם) just like the prophet, would soon realise his limits and weakness when the true God determined to establish his judgments against him.

The Tyrian king had two things to boast about-his wisdom38 and his wealth. The king's wisdom led to the great increase of his wealth (חיל).39A parade of gold and silver in his treasuries was the most concrete evidence of his riches (vv. 4-5). The king displayed his honour by his extraordinary wisdom and wealth. However, such a worldly wisdom only made the king's heart to be lifted up (גבהּ) and defiant against God, to the point of claiming that he was equal with God. The king was a self-made god. Ironically, the arrogant king would soon lay bare all his glory to the dust of the earth. The story of honour and shame continues.

2a The King's Death in Shame as a Mortal Man (28:6-10)

In this segment, the main argument is, in response to the king's earlier arrogant divine claim (אל אני, v. 2), to prove that the king was indeed a human rather than a god. The prophet supported his argument by offering progressive evidences- the king was a man, a vulnerable man, a vulnerable man bound to die, even a vulnerable man who would succumb to a shameful death. Ideas are built up in layers to intensify the motif of אדם. Ezekiel's audience would be able to draw the conclusion for themselves in the end that the king was a mere mortal man and not a god.

Hubris was an open challenge and full-scale rebellion against God. The king coveted a position only reserved for the divine and was thus judged accordingly. If the king would claim the status of a god, then, he should defend his honour as a god. Only honour that stands against challenge and remains is true honour. However, the king's honour, as it turned out, would turn to shame momentarily when God judged him with a terrible death. The Tyrian king, a man (אדם) and not a god, would soon realise how vulnerable and fragile he was before invading powers.

God would cause ruthless strangers to rise against him whose power was so strong that the king would have no strength to withstand. One could easily echo Nebuchadnezzar's destructive forces against the city in ch. 26. The ruthless strangers were about to draw their swords against the beauty of his wisdom and pierce (חלל II) his splendour.40

The king would be utterly destroyed after being struck. The king would die a terrible death of those slain (חלל). The homonymic subtlety between the adjectives חלל II ("slain") and חלל I ("profaned") can be explained as a slain person being ritually defiled before the public (Num 19:11). Despite the king's glorious past days, the ending would be catastrophic.

The king's death was not of natural cause; both הרג and חלל II imply a ruthless violent death. The king of Tyre was not a god who stood up to the challenge; he was only a mere mortal. The death of the king of Tyre was further portrayed as a disgraceful end by the hands of ערלים ("uncircumcised") foreigners.41 The Phoenicians, like most other ANE nations, probably practiced circumcision as well.42 Thus, death through the "uncircumcised" strangers was the ultimate insult.

The king's position of honour was all taken away and his shameful status intensified step by step. The king was relegated from the claimed position of a god to that of a man, a vulnerable man, a man slated to die and a man that would die shamefully. The concluding declarations אני דברתי and נאם אדני יהוה seal the king's shameful fate. As much as the king tried to grab the honour of God by claiming the position of a god (v, 2, 9), the Lord also defended his own honour by executing his righteous judgment through his own words. For Ezekiel's exilic audience, it is comforting that no matter how honourable Tyre perceived herself, in the blink of an eye, this enemy who taunted Israel and defied YHWH would be subjected to her own shame.

3 a The King' s Past Glory as an Adamic Figure in Remembrance (28:11-15)

After the oracle of judgment against the Tyrian king (vv. 1 -10), a lament immediately follows (vv. 11-19), just like the pattern of the first pair of oracles and the lament against the city of Tyre in chs. 26-27. When the king, a man (אדם), not a god, was totally cut off, a funeral song would be appropriate following his death. 43 Ezekiel's portrayal of the Tyrian king in this lament was highly imaginative and poetic. What remained unchanged was the description of the ups and downs of the king's honour and shame. The first sub-unit brings to memory the king's past glory in Eden (11-15) and the second accentuates the reality of the king's annihilation in shame (15-19). As Greenberg says, the story narrates the king's "past glory and present calamity."44

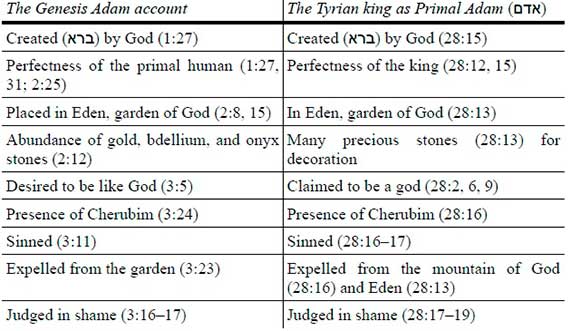

In a nutshell, the whole lament, as a progressive development of the earlier motif of the king as a man (אדם), nevertheless, reflects another perspective of the אדם-the king as a rising and fallen primal man (אדם). Some reasons may be considered for this use; first, the Hebrew word אָדָם evokes a double entendre, 45 meaning potentially both "man" and the proper name "Adam."46 Second, the king, as a man (אָדָם), also resembles the trajectory of the rise and fall of the first royal Adam (אָדָם) in his given honour and shame.47Likening the Tyrian king to Adam was conducive to penetrating into the earlier motif of the king's humanness. That explains why the Edenic image is so pervasive in this lament (see the following table for a comparison between the Tyrian Adamic king and the Genesis Adam account).

This startling comparison shows that Ezekiel was interested in using the Genesis Adam account as an antitype to foreshadow the bleak destiny of the Tyrian king, who was likened to the Edenic Adam (אדם). Shared patterns do exist between these two figures. Though some of the imageries remain obscure, it does not blur the whole big picture of the king as the primal Adam, who was once honoured but later shamed for his sins. 48 The Tyrian king, by analogy, was portrayed as the primal Adam. Readers should not forget that this whole lament heightens the earlier argument that the king was a man (אדם) and not a god.

The lament starts by describing the king as חותם תכנית (Ezek 28:12), an obscure phrase perhaps referring to the king's "royal authority."49 Though some read it as "measurement" (the root taken from תכן) or "copy, pattern" (thus תָבְנִית, a slight consonantal variation of תכנית),50there may be better evidence that the ת is a prefixed noun morpheme, hence from the verb כנה "to give an honorary name to"-cognate to the D-stem of Akkadian kanü "treat kindly, praise, do honour to, care for tenderly, look after."51 If this is the case, then, the Tyrian king was simply seen as an honourable signet.

The Tyrian king, as the primal Adam, was praised as an honourable signet. The king's superiority was enriched by the adjectival description of his full wisdom and perfect beauty (28:12). After this, the prophet continued to portray the king's honour exemplified by his comfort and pleasure in Eden, the garden of God.

The switch to Eden is perhaps unexpected.52 Nevertheless, if the king of Tyre was deemed a man (אדם) and not a god (vv. 2, 9), then, it is not surprising that a natural dwelling place for man (אדם) belonged in Eden prior to the fall53or better still, as I argued before, אדם, with its double entendre for both "man" and the personal name "Adam," could have easily stimulated the memory.

Eden was a perfect utopian place with bounty and beauty. Likewise, the Adamic king was provided with full prosperity, richness, splendour and joy. All precious stones were prepared for his decorations54 and golden vessels for his use. The current prevailing discussions argue that these stones refer to the stones of the high priests’ breastplate,55 thus, suggesting that the king was somehow identified with the Israelite high priest.56 By adding to twelve stones as the exact name and order of that of the Israelite high priest, the LXX certainly reflects such a tradition.57

However, the overall Edenic context and the missing three jewel stones and the current irregular order suggest that it was less likely that Ezekiel was alluding to a priestly background.58 One has to also note that the oracles against the nations were intended to be taken, not as critique but, as comfort for Judah.59Lastly, the prophet aligned the gemstones with the golden tambourine (נקב) and pipe(תף) 60 These two terms were possibly musical instruments; thus, the celebration of singing and dancing often accompanied their presence.61 It is no surprise that all these valuable items were prepared for the Tyrian Adamic king since his creation.62 The king, an Adamic figure, whose honour was paralleled with that of the primal Adam in Paradise, was entitled to premium wealth and pleasure.

The king's Edenic honour was carried on in the enigmatic discussion of the cherub. The "anointed cherub" in verse 14 is perhaps one of the most difficult texts in the entire OT. The vocalisation of את creates two totally different interpretations, that is, either "you were" (אַ) the cherub or "with" (אֶת) the cherub. Grammatically speaking, both readings are possible but neither without problems.63 Whatever rendition one chooses-"you" (אַ ת) or "with" (אֶת)-the discussion is further complicated when one takes verse 16 into consideration.64From a grammatical perspective, there is no prevailing leverage to choose over another.65

For the following reasons, my argument is that the king of Tyre was אֶת("with") the cherub. First, the context of this whole lament is certainly Edenic. Arguments based on the intertextuality of Gen 3:24 are more relevant. There was little doubt that the prophet drew on the Genesis narrative to foreshadow the king's fate. The lament was about the fall of the king, not the fall of the cherub. In continuity with the reading of verses 12-13, the king of Tyre was clearly in the Garden of Eden as the perfect Adam (אדם). A natural continuous reading in verse 14 would also place the primal Adamic king with the cherub within the context of Eden. The cherub's unobtrusive presence in God's own garden, though unsaid, was part of God's own arrangement to guard Adam. The identity of the primal Adam and the cherub should not be mixed.66

Second, cherubim are always depicted as a positive image within the Scriptures as angelic beings who approached God's presence in the ark of God (Exod 25:18-20, 22; Num 7:89; 2 Sam 6:2) and were taken as carriers of the throne of God.67 Even in the book of Ezekiel, cherubim are always portrayed as being present with the glory of God (1:5-25; 9:3; 10:1-22; 11:22)68 and particularly important, such a portrayal of cherubim remained honourable in the new visionary temple after Ezek 28 (see 41:18-25).69 There is no evidence in the book of Ezekiel alluding to their fall.

Thus, given the support of the immediate and the canonical context, I conclude that an apostate cherub70 is highly unlikely in Ezek 28. The king of Tyre, by analogy, is portrayed as the primal royal Adam for his unparalleled honour by the expression of his royal authority, wisdom and perfectness. The king enjoyed his premium comfort and pleasure in Paradise; even the cherub, God's angelic being, was called to his service. Nevertheless, all such is a given honour for now and it will not last much longer.

4a The King' s Annihilation in Shame as an Expelled Adamic Ruler (28:1519)

Soon the Eden narrative discourse changes. The king's honour would be dramatically shifted to the degradation of shame. As in the lament in ch. 27, Tyre was purposely honoured in order to be shamed.

Injustice soon was discovered in the Tyrian king, echoing the sins of the primal Adam in Eden. This is the turning point of whole Edenic narrative. The king was accused of being full of violence in his trade. Though no specific charges were levelled against him, a scandal of human trafficking (27:13) might provide a glimpse of his violence. Tyre had easily exploited other trading partners with her an advantageous position in commerce.71 As the king sinned (ותחטא), the Lord God cast him out as profane (חלל I) from the mountain of God, that is, the transformed Garden of Eden in the Levant. The king, as the primal Adam, had violated the sanctity of the garden by his sins which made him unfit for a continuous stay.72 Thus, the Lord God, through the cherub, expelled him from the garden.73 The king was removed from his glorious position. Terms such as חמס ("violence"), חטא ("sinned"), חלל I ("profaned") and אבד I ("destroyed"), all connote significant shameful language. The king of Tyre, now as the fallen primal Adam, lost all his Edenic glory when he sinned.

The corruption of the king rots from within; the haughtiness of heart and the misappropriation of wisdom reflect such a fact. The king's beauty and splendour are not evil per se-it is his inability to maintain such honour. Thus, the king was hurled to the ground and was treated (נתתיך)74as a spectacle75before the kings. If the fall of the Tyrian king by itself was already painful to bear, then, having such a calamity exposed before fellow kings would only mean a shameful and disgraceful end. What a tragedy that Tyre, which used to be a shiny emblem adored by all nations, is now treated with contempt. The tragic ending (28:19) echoes the same catastrophic fate in the previous two chapters (26:21; 27:36). The three chapters form a cohesive purpose of bringing shame to the king of Tyre.

Summing up, the Tyrian king was likened to the primal Adam in his fall. The king's shameful status was triggered by his sin. Having sinned, the king was declared to be desecrated and thus unfit to stay anymore in Paradise. The king's shamed image worsened as he was made a spectacle before the kings. The power that stood against God and God's people, despite its unequalled glory, had arrived at a shamed despicable end. The demise of the Tyre brought great consolation to the suffering Israelites in exile, for the Lord God would also judge her for her sins and for the ridicule she hurled against Jerusalem despite the peak of her honour.

E CONCLUSION76

There is no question that Tyre has already reached her honourable position by the expressions of her status, eminence, betterment, perfection, reputation, wealth and wisdom. Yet Tyre has squandered the bestowed honour by transgressing against the Lord God when she taunted over the fall of Jerusalem. Since then, shame and disgrace befell Tyre. She was judged to be worthless, destructive, defiled and insignificant.

Ezekiel 28:1-19, as a part of the oracles in chs. 26-28, stands at a critical position to explain Tyre's fall-arrogant powers that had defied God and practised injustice were doomed to perish. The Tyrian king's boastful claim to the status of divinity proved to be ignorant. The king was about to die as any other mortal man. The Tyrian king was likened to the primal Adam for both his Edenic glory and his humiliation in shame. The rhetoric of honour and shame plays an important role in understanding Ezekiel's account of the rise and fall of the king of Tyre.

The rhetoric of honour and shame, thus, offers a possible way to unravel the prophet's purpose in our reading of the texts. As much as God judged Israel for her sins, he would also hold Tyre, a hostile nation that humiliated God's people at Jerusalem's destruction and haughtily rebelled against YHWH, accountable for her own iniquities. The exilic community had to learn to trust in YHWH for granting them justice, acting impartially against all disgrace and injustice being done to them. The oracles against Tyre, as they were intended to be, prepare the way to bring hope and comfort to God's suffering people in exile.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Leslie C. Ezekiel 20-48. Word Biblical Commentary Vol. 29. Dallas: Thomas Nelson, 1990. [ Links ]

Bechtel, Lyn M. "Shame as a Sanction of Social Control in Biblical Israel: Judicial, Political, and Social Shaming." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 16 (1991): 47-76. [ Links ]

__________________. "The Perception of Shame within the Divine-human Relationship in Biblical Israel." Pages 79-92 in Uncovering Ancient Stones: Essays in Memory of H. Neil Richardson. Edited by Lewis M. Hopfe. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel I. The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997. [ Links ]

__________________. The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

__________________. "Beyond the Grave: Ezekiel's Vision of Death and Afterlife." Bulletin for Biblical Research 2 (1992): 113-141. [ Links ]

Boadt, Lawrence. "Rhetorical Strategies in Ezekiel's Oracles of Judgment." Pages 182-200 in Ezekiel and His Book: Textual and Literary Criticism and Their Interrelation. Edited by J. Lust. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 74. Leuven: Peeters, 1986. [ Links ]

Callender, Dexter E. Adam in Myth and History: Ancient Israelite Perspectives on the Primal Human. Harvard Semitic Studies 48. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2000. [ Links ]

__________________. "The Primal Human in Ezekiel and the Image of God." Pages 175-193 in The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives. Edited by Margaret S. Odell and John T. Strong. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Cooke, G. A. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Ezekiel. The International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1936. [ Links ]

Corral, Martin Alonso. Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre: Historical Reality and Motivations. Biblica et Orientalia 46. Roma: Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2002. [ Links ]

Crouch, C. L. "Ezekiel's Oracles against the Nations in Light of a Royal Ideology of Warfare." Journal of Biblical Literature 130 (2011): 473-492. [ Links ]

Day, John. "The Daniel of Ugarit and Ezekiel and the Hero of the Book of Daniel." Vetus Testamentum 30 (1980): 174-184. [ Links ]

Domeris, W. R. "Shame and Honor in Proverbs: Wise Women and Foolish Men." Old Testament Essays 8 (1995): 87-128. [ Links ]

Duguid, Iain M. The NIV Application Commentary: Ezekiel. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1999. [ Links ]

Eichrodt, Walther. Ezekiel. Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox, 2003. [ Links ]

Fairbairn, Patrick. An Exposition of Ezekiel. Minneapolis: Klock & Klock, 1979. [ Links ]

Garfinkel, Stephen. Studies in Akkadian Influences in the Book of Ezekiel. New York: Columbia University, 1983. [ Links ]

Greenberg, Moshe. Ezekiel 21-37. New York: Yale University Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Häner, Tobias. "Reading Ezekiel 36.16-38 in Light of the Book: Observations on the Remembrance and Shame after Restoration (36.31-32) in a Synchronic Perspective." Pages 323-344 in Ezekiel: Current Debates and Future Directions. Edited by William A. Tooman and Penelope Barter. FAT 112. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017. [ Links ]

Lapsley, Jacqueline E. "Shame and Self-knowledge: The Positive Role of Shame in Ezekiel's View of the Moral Self." Pages 143-173 in The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives. Edited by Margaret S. Odell and John T. Strong. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000. [ Links ]

Launderville, Dale. "Ezekiel's Cherub: A Promising Symbol or a Dangerous Idol?" The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 65 (2003): 165-183. [ Links ]

Lee, Lydia. Mapping Judah's Fate in Ezekiel's Oracles against the Nations. Ancient Near Eastern Monographs 15. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2016. [ Links ]

Malina, Bruce J. The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology. 3rd ed. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001. [ Links ]

Markoe, Glenn E. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. [ Links ]

May, Herbert G. "The King in the Garden of Eden." Pages 167-176 in Israel's Prophetic Heritage: Essays in Honor of James Muilenburg. Edited by Bernhard W. Anderson and Walter Harrelson. New York: Harper, 1962. [ Links ]

McKeating, Henry. Ezekiel. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1993. [ Links ]

Newsom, Carol A. "A Maker of Metaphors: Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre." Interpretation 38 (1984): 151-164. [ Links ]

Pedersen, Johannes. Israel, Its Life and Culture. London: Oxford University Press, 1926. [ Links ]

Renz, Thomas. The Rhetorical Function of the Book of Ezekiel. Leiden: Brill, 1999. [ Links ]

__________________. "Proclaiming the Future: History and Theology in Prophecies against Tyre." Tyndale Bulletin 51 (2000): 17-58. [ Links ]

Sasson, Jack M. "Circumcision in the Ancient Near East." Journal of Biblical Literature 85 (1996): 473-76. [ Links ]

Saur, Markus. "Tyros im Spiegel des Ezechielbuches." Pages 165-190 in Israeliten und Phönizier: Ihre Beziehungen im Spiegel der Archäologie und der Literatur des Alten Testaments und seiner Umwelt. Edited by Markus Witte and Johannes F. Diehl. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 235. Fribourg: Academic Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Seters, John Van. "The Creation of Man and the Creation of the King." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 101 (1989): 333-342. [ Links ]

Simkins, Ronald A. "Return to Yahweh: Honor and Shame in Joel." Pages 41-54 in Honor and Shame in the World of the Bible. Semeia 68. Edited by Victor H. Matthews, Don C. Benjamin and Claudia Camp. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1996. [ Links ]

Stiebert, Johanna. "Shame and Prophecy: Approaches Past and Present." Biblical Interpretation 8 (2000): 255-275. [ Links ]

Strong, John T. "God's Kavod: The Presence of Yahweh in the Book of Ezekiel." Pages 69-95 in The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives. Edited by Margaret S. Odell and John T. Strong. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000. [ Links ]

__________________. "In Defense of the Great King: Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre." Pages 179194 in Concerning the Nations: Essays on the Oracles against the Nations in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Edited by Andrew Mein, Else K. Holt and Hyun Chul Paul Kim. London: Bloomsbury, 2015. [ Links ]

Wu, Daniel. Honor, Shame, and Guilt: Social-scientific Approaches to the Book of Ezekiel. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2016. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, Walther. Ezekiel 1: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1979. [ Links ]

__________________. Ezekiel II: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Chapters 2546. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983. [ Links ]

Submitted: 13/04/2021

Peer-reviewed: 29/09/2021

Accepted: 16/11/2021

Bin Kang (Ph.D) is from China and is currently teaching in Biblical Seminary of the Philippines, 77-B Karuhatan Rd, Valenzuela, 1441 Metro Manila, Philippines. Email: omove316@hotmail.com, ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1089-7654.

1 Oracles are issued against Ammon (25:1-7), Moab (25:8-11), Edom (25:12-14; 35:1-15), Philistia (25:15-17) and Gog (38:1-39:29).

2 John T. Strong, "God's Kavod: The Presence of Yahweh in the Book of Ezekiel," in The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives (eds. Margaret S. Odell and John T. Strong; Atlanta: SBL, 2000), 90.

3 For scholars who see a political agenda in the text, see Walther Eichrodt, Ezekiel (Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox, 2003), 367-369. Eichrodt claims that Tyre regards Judah, though a previous ally, as a political threat in the task of leading resistance against Babylon. The fall of Judah would avail Tyre of the best chance to overtake Judah in its prominence. Tyre's competition with Jerusalem for a regional trade centre is also taken into consideration. Cf. Leslie C. Allen, Ezekiel 20-48 (WBC 29; Dallas: Thomas Nelson, 1990), 75-76, who sees it as more of a political problem than an economic concern. Tyre expects a shift of power as a new leader in the area at the fall of Jerusalem. For scholars who read the text from an economic perspective, see Daniel I. Block, The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48 (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 32. Block suggests that Tyre exults over the fall of Jerusalem as an opportunity to expand its commercial interests. Lastly, Corral surveys the subject from a historical and culture background by investigating the Babylonian relationship with Jerusalem and Tyre. The author concludes that economic and political reasons are the main causes for the divine condemnation. This work is the most extensive and updated research on this topic. See Martin Alonso Corral, Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre: Historical Reality and Motivations (BibOr 46; Roma: Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2002).

4 See Lawrence Boadt, "Rhetorical Strategies in Ezekiel's Oracles of Judgment," in Ezekiel and His Book: Textual and Literary Criticism and Their Interrelation (BETL 74; ed. J. Lust; Leuven: Peeters, 1986), 199.

5 See C.L. Crouch, "Ezekiel's Oracles against the Nations in Light of a Royal Ideology of Warfare," JBL 130 (2011): 473-492.

6 Ezekiel has been considered a book which uses the rhetorical unit as a means of communication. See Thomas Renz, The Rhetorical Function of the Book of Ezekiel (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 249.

7 He addressed nations such as Ammon (25:1-7), Moab (25:8-11), Edom (25:12-14), Philistia (25:15-17) and Sidon (28:20-23).

8 Allen, Ezekiel 20-48, 95-96.

9 Strong, "God's Kavod," 91.

10 See, e.g., Bruce J. Malina, The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1981), 25-51.

11 Ibid, 30. The latter, a person's value in the eyes of his/her community, appears to be stronger in community-oriented cultures in many parts of Asia.

12 Johannes Pedersen, Israel, Its Life and Culture (London: Oxford University Press, 1926), 213-244.

13 Johanna Stiebert, "Shame and Prophecy: Approaches Past and Present," BibInt 8 (2000): 257. Similarly, Lyn M. Bechtel, "Shame as a Sanction of Social Control in Biblical Israel: Judicial, Political, and Social Shaming," JSOT 16 (1991): 49.

14 According to Wu, the most common and significant use of an emic view of כבד in the book is the theophany, a concern for the glory of God as the centring message, together with the broader concept of related wealth, splendour, and exaltation. Tyre was also noted for its change of honour by the reference to the fate of the ships of Tarshish. See Daniel Wu, Honor, Shame, and Guilt: Social-scientific Approaches to the Book of Ezekiel (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2016), 92.

15 W. R. Domeris, "Shame and Honor in Proverbs: Wise Women and Foolish Men," OTE 8 (1995): 87-128. Wisdom and wealth were general expression of one's honour in wisdom literature (Prov 3:9, 16, 22, 35; 4:5-9; 8:18; 14:24; 31:13-22).

16 See Wu, Honor, Shame, and Guilt, 100-131.

17 Henry McKeating, Ezekiel (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1993), 86-87.

18 Ibid., 87.

19 Walther Zimmerli, Ezekiel 1: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24 (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1979), 28-29.

20 See Tobias Häner, "Reading Ezekiel 36.16-38 in Light of the Book: Observations on the Remembrance and Shame after Restoration (36.31-32) in a Synchronic Perspective," in Ezekiel: Current Debates and Future Directions (FAT 112; eds. William A. Tooman and Penelope Barter; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017), 323-344. Häner argues that the experience of positive shame is stressed in Ezek 36:31-32 to tell about Israel's genuine restoration to YHWH.

21 Before the destruction of Jerusalem, the king of Judah was still Zedekiah. Ezekiel intentionally avoids Zedekiah in his calculation; such a fact shows that he identifies himself with the exiled community. See Daniel I. Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24 (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 6.

22 See Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 1-24, 5; Iain M. Duguid, The NIV Application Commentary: Ezekiel (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1999), 35; John T. Strong, "In Defense of the Great King: Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre," in Concerning the Nations: Essays on the Oracles against the Nations in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel (eds. Andrew Mein, Else K. Holt and Hyun Chul Paul Kim; London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 179-194. The fate of Jerusalem was fixed and the city was destroyed due to God's justice for the sins of his people; but those of the Babylonian exile who coped with the fall of the Jerusalem also longed for YHWH's justice towards other nations who had mistreated Judah so badly. Hence, we see many oracles highlighting the callous and blatant disregard of Judah by various nations as a reason for God's judgment; see Ezek 25:3, 8, 12, 15; 26:2; 35:5 (note also that the dating of most oracles was around the time of Jerusalem's fall). This explains why the judgment oracles against the nations were seen as God's divine responses to comfort to the first-generation exiles. Nevertheless, the chronological framework for the last vision of a new temple was set as the "twenty-fifth year of our exile (Ezek 40:1)," which made it very likely a mixed audience of first and second-generation exiles.

23 Letters of correspondence were still a convenient means of communication between Judah and Babylon before the fall of Jerusalem (Jer 29:4, 31).

24 Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48, 3-4.

25 The oracle against Tyre was set out chronologically as "the eleventh year" of the exile (Ezek 26:1), roughly a year before the fall of Jerusalem (Ezek 33:21). This dating reference would cut off any possibility that Ezekiel's message was communicated to Hebrews in Judah at this point of time, since Jerusalem was already under heavy siege by King Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kgs 25:1-2; Jer 52:4-6). Nothing came in or went out of Jerusalem during the latter phase of the siege and, in fact, the famine brought on by the prolonged siege was so severe that even horrendous maternal cannibalism occurred within the city (Lam 2:20; 4:10).

26 A fallen Judah suffered shame since it demonstrated its weakness before other nations. See Ronald A. Simkins, "Return to Yahweh: Honor and Shame in Joel," in Honor and Shame in the World of the Bible (Semeia 68; eds. Victor H. Matthews, Don C. Benjamin and Claudia Camp; Atlanta: SBL, 1996), 49-52.

27 For instance, in a modern honour/shame context, parents cannot see their children beaten by others even though fault is found with the children. A good solution, in such circumstance, is to hand over the erring children to the parents and let them discipline their young ones. By doing so, the face of the parents is saved and the mistake of the children rectified by the authority of ones' own family.

28 Lyn Bechtel, "The Perception of Shame within the Divine-human Relationship in Biblical Israel," in Uncovering Ancient Stones: Essays in Memory of H. Neil Richardson (ed. Lewis M. Hopfe; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994), 84. It was commonly believed in the ancient Near East that it was the responsibility of the gods to protect the people from reproach and shame. Such concern was even reflected in some Akkadian personal names. Likewise, it was YHWH's commitment to protect Israel from being shamed; such a relationship was assumed in the Deuteronomic covenant.

29 This is in contrast with Tyre's past glory, described as a city renowned and mighty on the sea (26:17-18).

30 The description of Tyre's excellence relates to its affluence. The details range from the valuable materials used for the building up of the ship (vv. 5-7), to wise people employed for their business (vv. 8-9), great strength of mercenary armies (vv. 10-11) and varieties of cargoes traded with all possible nations (vv. 12-24).

31 Honour and shame play an important rhetorical role in understanding Ezekiel's messages. See Jacqueline E. Lapsley, "Shame and Self-knowledge: The Positive Role of Shame in Ezekiel's View of the Moral Self," in The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives (eds. Margaret S. Odell and John T. Strong; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000), 143-173.

32 Ammon also mocked with האח (aha, 25:3) as did Tyre in 26:2.

33 This was especially the case when Tyre remained an effective power that stood against the advances of Babylon. Historically, Tyre was known in the Mediterranean world to have resisted the earlier Assyrian expansion and dominance, partly due to the advantageous geographical position as an island-city. See Thomas Renz, "Proclaiming the Future: History and Theology in Prophecies against Tyre," TynBul 51 (2000): 2426.

34 The king probably did not intend to replace the gods of his people with himself. The cults of Melqart (male god) and Astarte (female god) seemed to be the state religion since the time of King Hiram I (10th century BC). According to Josephus, sanctuaries to Melqart and Astarte were rebuilt. It showed a sign of public celebration and endorsement of the "awakening" of these gods. See Glenn E. Markoe, Peoples of the Past, Phoenicians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 115-119.

35 In Exod 7:1, though Moses is made to be "god" (אלהים) to Pharaoh, the context clearly suggests that Moses is a godlike figure rather than God himself; thus, many translations render it "as God" (ESV, NASB, NRSV, NET). In Ps 8:5, it is true that the psalm refers to humans in general but the overall context of this psalm strongly echoes the narrative of Adam, who is seen as a royal figure to rule on God's behalf in Genesis (1:28). Meanwhile, verbs like "crown" (עטר, Ps 8:6) and "rule" (משׁל, Ps 8:7) suggest a royal position. Saur also suggests that it is very likely that the divinity of the king was a common belief within the Tyrian religion. See Markus Saur, "Tyros im Spiegel des Ezechielbuches," in Israeliten und Phönizier: Ihre Beziehungen im Spiegel der Archäologie und der Literatur des Alten Testaments und seiner Umwelt (OBO 235; eds. Markus Witte and Johannes F. Diehl; Fribourg: Academic Press, 2008), 181.

36 Renz, "Proclaiming the Future," 23-25. The Assyrians were unable to subjugate Tyre entirely because they could not conquer the island-city.

37 The Hebrew word אדםis ambiguous in meaning, referring to either man or the personal name, Adam. If the first unit of the oracle argues for the king's humanness rather than divinity, then, the second unit of the lament is a reflection on how the king, as a man (אדם), resembles the trajectory of the rise and fall of the first man (אדם) whose personal name is also אדם ("Adam"). The primal human also attempted to be like God (Gen 3:5) and it triggered the rebellion against God. That explains why the Edenic image is so pervasive in the lament. The prophet was playing with a double entendre of the word אדם.

38 The MT says that the Tyrian king was even wiser than Daniel. The LXX reads it quite differently, phrasing it as a negation. Scholars have usually debated if this was the biblical Daniel in the OT book of Daniel or Danel as an extra biblical figure. Cf. e.g., John Day, "The Daniel of Ugarit and Ezekiel and the Hero of the Book of Daniel," VT 30 (1980): 174-184. There is no decisive evidence for either side of this controversial issue. Nevertheless, a rhetorical reading suggests that although the message talks about the king of Tyre, it was actually addressed to Israel in exile. It is possible that the king (prince) of Tyre was only the hypothetical "addressee"-Ezekiel meant to speak directly to the exiled Israelites through God's dealing with this city-state; see Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48, 90. One cannot rule out the possibility of a legendary Daniel in the Babylonian court. The enlisting of Noah, Daniel and Job in Ezek 14:14, 20, in its context, only emphasises their piety before God but not their foreign origins. Meanwhile, it is doubtful if all exiled Israel was familiar with a remote foreign ruler and legendary sage Danel whose presence was not found in texts after the fourteenth century. See Herbert G. May, "The King in the Garden of Eden," in Israel's Prophetic Heritage: Essays in Honor of James Muilenburg (eds. Bernhard W. Anderson and Walter Harrelson; New York: Harper, 1962), 167.

39 The emphasis could be seen from three occurrences of in verses 4-5.

40 The most natural function of the verb חלל in this context (28:7) is piercing and cutting. The perfect consecutive clause והריקו חרבותם על־יפי חכמתך, followed by the perfect consecutive וחללו יפעתך, arguably pertains to what swords do-they are emptied (unleashed), followed by piercing activity (their function of piercing the king's splendour).

41 Circumcision was a sign of the Abrahamic Covenant (Gen 17) and thus a key symbol for Israel as the covenant people of God. The term may have evolved during Ezekiel's time to connote "cultural superiority." See Daniel I. Block, "Beyond the Grave: Ezekiel's Vision of Death and Afterlife," BBR 2 (1992): 124.

42 Jack. M. Sasson, "Circumcision in the Ancient Near East," JBL 85 (1996): 473-476.

43 Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48, 102.

44 Moshe Greenberg, Ezekiel 21-37 (New York: Yale University Press, 1995), 587-588.

45 The description of the Tyrian king as an אָדָם in ch. 28 is potentially designed to be understood as both homonym number 1, a "man" (28:2, 9) and homonym number 3, the personal name "Adam" (although the Hebrew word אדם does not appear itself in the lament unit to describe the king, the reference of the king to בעדן גן־אלהים היית "you were in Eden, garden of God" [28:13] and other royal descriptions clearly evoke the identity of the First Man, "Adam"). The homonymic play on אדם in ch. 28 is very likely. Indeed, a number of scholars have connected Ezek 28:11-19 in some way to an "Adamic" myth related to the story of Adam in Gen 2-3. See G. A. Cooke, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Ezekiel (The International Critical Commentary; Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1936), 316-318; Walther Zimmerli, Ezekiel II: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Chapters 25-46 (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983), 90-91, 95; John Van Seters, "The Creation of Man and the Creation of the King," ZAW 101 (1989): 333-342; Dexter E. Callender, "The Primal Human in Ezekiel and the Image of God," in The Book of Ezekiel: Theological and Anthropological Perspectives (eds. Margaret S. Odell and John T. Strong; Atlanta: SBL Press, 2000), 177-180.

46 For clarification, "Adam" hereafter refers not to general "man" but to the name of the First Man, "Adam."

47 Adam, the first royal man, was invested with glory to rule over all other creatures (Gen 1:27-28). Adam, as a royal ruling figure, makes this application to the Tyrian king more appropriate. See Herbert G. May, "The King in the Garden of Eden," 169-171. Adam also attempted to be like God (Gen 3:5, 7) and was judged by God in great shame.

Eden was a perfect utopian place with bounty and beauty. Likewise, the Adamic king was provided with full prosperity, richness, splendour and joy. All precious stones were prepared for his decorations and golden vessels for his use. The current prevailing discussions argue that these stones refer to the stones of the high priests' breastplate, thus, suggesting that the king was somehow identified with the Israelite high priest. By adding to twelve stones as the exact name and order of that of the Israelite high priest, the LXX certainly reflects such a tradition.

48 Dexter E. Callender, Adam in Myth and History: Ancient Israelite Perspectives on the Primal Human (Harvard Semitic Studies 48; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2000), 87; also Carol A. Newsom, "A Maker of Metaphors: Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre," Int 38 (1984): 160-161.

49 Callender, Adam in Myth, 97.

50 The כ and ב are very similar in script and may be easily confused.

51 The Akkadian taknltu, derived from kanü, means "loving treatment of an object, adoring respect for a goddess," see CAD-K 540b; hence, it is possibly translated as "a seal/signet tenderly cared for." See Stephen Garfinkel, Studies in Akkadian Influences in the Book of Ezekiel (New York: Columbia University, 1983), 135.

52 The king's distinguished abode was said to be in the "heart of the sea" (27:4).

53 Patrick Fairbairn, An Exposition of Ezekiel (Minneapolis: Klock & Klock, 1979), 310. '

54 The word מסכתך was used probably to tell about a royal garment with gemstones covering the chest-plate. The precious stones ostensibly exhibited one's honour by the first sight. It was a sign of "prosperity, opulence, and wealth." Corral, Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre, 161.

55 Compared with the priestly jewel stones listed in Exod 28:17-20 and 39:10-13, Ezek 28:13 lacks the third set of the twelve gemstones and the ordering of stones in Ezekiel is also different. It was also likely the gemstones in Ezekiel might have been adapted from the high priest's breast piece. See Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48, 106.

56 Lydia Lee, Mapping Judah's Fate in Ezekiel's Oracles against the Nations (ANEM 15; Atlanta: SBL Press, 2016), 95-101. Lee argues that the list of jewels in Ezek 28:13 strongly evokes Israel's high priest; thus, the oracle against king of Tyre was actually an implicit satire against Israelite priests.

57 The LXX is also not without problems. Although the listed name and order of gemstones were exact as that of the Exodus priestly account (28: 17-20), the insertion of ἀργύριον (silver) καὶ χρυσίον (gold) in the middle of the jewel list makes the problem even more intriguing. It is highly likely that the LXX was a secondary adjustment in conformity with the Exodus account. See Greenberg, Ezekiel 21-37, 582.

58 Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48, 102. Block concludes that Ezekiel's list of gemstones may have some shadow of his priestly heritage but by no means does he identify the king of Tyre with the high priest of Israel.

59 Ibid., 112. Block says that this chapter should be read as a "positive message" for Judah.

60 Of course, anything that was made of gold was highly valuable and thus exhibited the king's superior status.

61 See Exod 15:20; Judg 11:34; 1 Sam 18:6; Pss 81:3, 149:3, 150:4; Job 21:12; Isa 5:12 and Jer 31:4.

62 Tyrian craftsmen specialised in the manufacture of luxury articles and they were famous for the production of articles of gold, jewellery, precious stones and many other materials. Corral, Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre, 129.

63 First, there is gender discord in reading a second person masculine pronoun (אַתָה) into a feminine (אַ ת). Ezekiel uses a masculine pronoun (אַתָה) to speak about the king in 28:2-3, 9, 12. Second, the presence of the waw (ו) before נתתיך is puzzling. If vocalised "... אֶת־כְרוּב," the waw is an intrusion, breaking the continuity and needs to be removed for proper syntactic flow. Whereas in the MT, read as an independent pronoun, אַתְ and what follows in the first part stands as a nominal clause; however, the syntax of the MT with its medieval accenting would require the waw + perfect, וּנְתַתִיךָ, to front the clause which follows, בהר קדשׁ אלהים ("And I placed you in the holy mountain of God," leaving הָיִיתָ without a complement). The postpositive disjunctive pasta at the end of אֱלֹהִי ם points to such a clause division. Obviously, however, Masoretic accenting is only interpretative and need not be regarded as authoritative. Not observing the accenting, וּנְתַתִיךָ בְּהַר קֹדֶשׁ, could function as a syntactical clausal unit with אֱלֹהִים הָ ייתָ which follows as the succeeding clause. Such a rendition would problematically identify the king of Tyre as both the cherub and God (אלהים היי), an equation foreign to the progress (28:2 and 28:9) of this pericope as well as the Gen 3:24 intertext arguably informing the reading of our text.

64 In the MT, the king of Tyre is presented as the cherub (v. 14) and God destroyed him because of his sins and violence (v. 16). On the other side, according to the LXX, the king of Tyre was given the honour to be with the cherub (v. 14) but later, following the LXX, it was God's judgment to expel him through the cherub (v. 16)-καὶ ἤγαγέν σε τὸ χερουβ ἐκ…

65 The defective second person feminine pronoun אַ ת in the MT by itself shows signs of textual corruption. The LXX witness possibly has an edge in rendering the first word as μετὰ "with" (אֶת).

66 Callender, Adam in Myth, 109.

67 See 2 Sam 22:11; 2 Kgs 19:15; Pss 80:1; 99:1 and Isa 37:16.

68 It is noted that two times Ezekiel describes the vision of the living creatures in detail (chs. 1 and 10) and he identifies them later as cherubim (10:15), carriers of the throne of God (1:26; 10:1).

69 Even the NT book of Hebrews describes them as Χερουβὶν δόξης ("cherubim of glory," Heb 9:5).

70 Dale Launderville, "Ezekiel's Cherub: A Promising Symbol or a Dangerous Idol?" CBQ 65 (2003): 165-183. Launderville sees the apostate Cherub as a symbol of the king of Tyre.

71 Tyre's participation in the earlier Assyrian oppression was noted. Tyre was essential in providing metals, horses and other luxury goods through its network of colonised territories such as Cyprus, Cadiz and others. Phoenician greed is commonplace in classical sources. For instance, the Tyrians could easily purchase metals from their colonised areas with little cost and trade it with other nations for a high value for agricultural items. Such a lopsided exchange put Tyre in a manipulative position to monopolise the trade. See Corral, Ezekiel's Oracles against Tyre, 66-76.

72 Block, Ezekiel, Chapters 25-48, 116. The verb חלל I is closely associated with cult language in contrast with קדשׁ in the distinction of sacred and profane. See Callender, Adam in Myth, 124.

73 Our story here echoes the Adam narrative in Genesis. Adam sinned, thus, was driven away from Eden and the cherubim prevented him from re-entering the garden by guarding it with a flaming sword (Gen 3:23-24). The difference is that the Tyrian king sinned, not by disobeying the direct words of God but by defying the general principle of justice and inequality in his trade dealings.

74 The king, who was placed (ונתתיך, v.14) by God to be in Eden, is now made (נתתיך) a subject of spectacle. Later, in verse 18, God would turn him (ואתנך) to dust of the earth. The satire of these words should not be ignored.

75 The LXX's use of παραδειγματισθῆναι is extremely vivid and connotes intensifying public shameful exposure. The preposition napa with the base δειγματίζω signifies the notion of being disgracefully displayed around. See Schlier, "δειγματίζω, παραδειγματίζω," TDNT 2, 32. It was a gaze (לראוה בך) with ill intention.

76 This article is an abridged version of my thesis which was submitted to Asia Graduate School of Theology, the Philippines. I am indebted to my mentor Dr. Tim Undheim for his supervision.