Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 no.3 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n3a4

ARTICLES

Jonadab Son of Shimeah: A Figure Wrapped in Controversy

Orly Keren; Hagit Taragan

Kaye Academic College of Education, Beer-Sheva, Israel

ABSTRACT

Jonadab son of Shimeah was King David's nephew. His character can be evaluated on the basis of the two brief scenes where he appeared in 2 Sam 13:3-5, 30-37. The article surveys four aspects of the controversy that swirls around Jonadab's moral nature: 1. The terms used to describe him, namely, "friend" and "a very smart man," which can be interpreted as "wise in evil counsel" (b. Sanh. 21a) or as "intelligent and perspicacious "; 2. The assessment of his conduct and relations with the other characters-Amnon, Tamar, Absalom, and David; 3. How he fits into the narrative as a whole and whether he is a main or supporting character; 4. How the editor revised the original author's text of this chapter. The first three aspects allow an examination of Jonadab' s moral character, the fourth determining whether his presence is essential to the story.

Keywords: Biblical narrative, Jonadab son of Shimeah, Episode, (Main or supporting) Character, Editor, Author

A INTRODUCTION

Amnon had a friend, whose name was Jonadab, the son of Shimeah, David's brother; and Jonadab was a very smart man (2 Sam 13:3).

Jonadab appears as a counsellor to the royal family in two brief episodes in 2 Sam 13, once to Amnon (vv. 3-5) and later to David (vv. 30-37). Then, after advising the prince and the king, he vanishes from the story and Scripture. We know nothing about him before his appearance in these episodes and nothing about his later life.

The present article examines the literary issues of Jonadab's personality and role in the story and examines the critical issue of whether he is essential to the "rape of Tamar" (2 Sam 13:1-39). It looks at Jonadab through the lens of "total interpretation"1 and a close reading of the text based on the assumption that all elements of the episodes in which he figures are relevant and interlinked, both with each other and with the story as a whole.2 This raises the questions of whether he is a positive or negative character and of his role and function in the story. We will also employ critical analysis to determine whether Jonadab is an essential player in the rape of Tamar (2 Sam 13:1-39) or perhaps an intruder from a secondary level who has been inserted into the original text. The latter issue has implications for Jonadab's presence in the story in the first place.3

B BOUNDARIES OF THE JONADAB EPISODES4

1 Jonadab offers advice to Amnon (2 Sam 13:3-5)

(3) Amnon had a friend, whose name was Jonadab, the son of Shimeah, David's brother; and Jonadab was a very smart man. (4) He said to him, "O son of the king, why are you so haggard morning after morning? Will you not tell me?" Amnon said to him, "I love Tamar, my brother Absalom's sister." (5) Jonadab said to him, "Lie down on your bed, and pretend to be ill; and when your father comes to see you, say to him, 'Let my sister Tamar come and give me bread to eat, and make the food in my sight, so I may watch and eat it from her hand.'"

After this brief appearance, Jonadab is absent from the stage during the intimate scene between Amnon and Tamar that follows (vv. 6-18).

The contents of the verses in which Jonadab offers advice to the lovelorn Amnon distinguish them from what comes before and after. The first two verses of the chapter, which describe Amnon's love for his sister, are static. There is no dialogue and Jonadab is not present. After his brief appearance, the next 13 verses (6-18) focus on how Amnon puts Jonadab's idea into practice.

The setting is explicit-"morning after morning" in Amnon's house (v. 4).5 The characters are Amnon and Jonadab and there is a causal link in the sequence of events.6 Amnon feigns illness because this is what his friend advised. Despite the brevity of the episode, the narrator packs it with all of the tension inherent in Jonadab's scheme to relieve Amnon's woes. Readers are naturally led to wonder whether the plot will work. Will Amnon recover?

2 Jonadab consoles David (vv. 30-37)

(30) While they were on the way, a rumor reached David: "Absalom has slain all the king's sons, and not one of them is left." (31) The king arose and rent garments torn. (32) But Jonadab the son of Shimeah, David's brother, said, "Let not my lord suppose that they have killed all the young men the king's sons. For Amnon alone is dead, as this has been ordained by Absalom since the day he violated his sister Tamar. (33) So let not my lord the king take it to heart and suppose that all the king's sons are dead; for Amnon alone is dead." (34) Absalom fled. And the young man who kept watch lifted up his eyes and saw many people coming from road to the west, on the side of the mountain. (35) And Jonadab said to the king, "Look, the king's sons have come; as your servant said, so it has come about." (36) And as soon as he had finished speaking, the king's sons came and lifted up their voice and wept; and the king also and all his servants wept very bitterly. (37) Absalom had fled and went to Talmai the son of Ammihud, king of Geshur, and David mourned for his son day after day.

This episode moves in a circle. It begins with a rumour that "Absalom has slain all the king's sons" (v. 30) and concludes with the consequence of that action- flight: "Absalom had fled" (v. 37).

The subject of this episode is Jonadab's reassurance to David with a strong emphasis on the young man's ability to calm the king and transform the opening situation-the rumour that all the king's sons have been slain. Jonadab is not present in the previous episode, which deals with Absalom's sheep shearing feast (vv. 23-29) or in the concluding account of Absalom's flight (vv. 38-39).

The setting is outside David's palace where the king and his courtiers are waiting for the princes to return home. The previous episode is set in Baal Hatzor, while the subsequent refers both Geshur and David's palace in Jerusalem.

C LINK BETWEEN THE TWO EPISODES

There is an internal link between the two episodes. In both of them Jonadab provides advice or information and in both he is identified with his full lineage: "Jonadab, the son of Shimeah, David's brother" (vv. 3, 32).7 The references to Jonadab's whereabouts link the episodes as well; in the first, he is with the king's son and suggests what he should tell his father (v. 5). In the second, Jonadab is with the king and provides information about Amnon the king's son and ultimately he is the person who announces his death (v. 32).

Another internal link is that Jonadab is privy to the details of what is happening. In the first episode, he knows about Amnon's love for Tamar and devises the scheme that will get her into Amnon's bedroom. In the second episode, Jonadab knew that Absalom was plotting to avenge his sister's rape and kill Amnon (v. 32) and tells David, on the basis of his knowledge, that Amnon was the only victim at Absalom's feast (v. 33).

Jonadab's sensitivity to feelings of others is prominent in both episodes. In the first, he perceives Amnon's ill health and suggests a way for him to recover (v. 4). In the second episode, he displays sympathy for David and tries to allay his anxiety (v. 33).

D WHO IS JONADAB SON OF SHIMEAH?

Amnon had a friend whose name was Jonadab the son of Shimeah and a very smart man (2 Sam 13:3).

Shimeah was David's older brother, Jesse's third son; he is also referred to as Shammah (1 Sam 16:9), Shime'i (2 Sam 21:21) and Shime'a (1 Chron 2:13).8 Thus, Jonadab is a first cousin to Amnon, Tamar and Absalom. There is some uncertainty about his name, too-cf. Jonadab (2 Sam 13:3), Jehonadab (13:5), or J[eh]onatan (2 Sam 21:21; 1 Chron 20:7).9 Although all three names refer to a son of David's brother, we do not know whether Jonadab and Jonathan are the same person or siblings.10 If they are one and the same, our Jonadab may have been one of David's mighty men, like Uriah, even though his name does not appear in the list of them.11 However, this is unlikely, given that we are not told that Jonadab was a member of this band but only that he was Amnon's "friend" and close to David. By contrast, the name Jonathan appears only in the military context (2 Sam 21:20-22). Therefore, it seems likely that we are dealing with brothers, one of whom was a member of the king's inner circle (Jonadab), while the other belonged to his troop of elite warriors (Jonathan) and may have perished in the same skirmish as Uriah (2 Sam 11:15), in which "some of David's servants fell with the people. Uriah the Hittite died as well" (2 Sam 11:17). If so, Jonadab's brother was one of the victims of the plot against Uriah concocted by David and Joab.

Jonadab is referred to as Amnon's "friend." In fact, the precise sense of the Hebrew term רֵ עַ is unclear. Some understand it as "groomsman," in the sense of the king's marriage broker who may advise him in matters of the heart-as Jonadab does for Amnon here.12 Some believe that only a blood relative of the king could hold the position.13 Others take it to mean an advisor to a nobleman (Gen 38:20) or privy counsellor to a ruler (1 Kgs 4:5). Some take רֵע in its primary meaning of "friend."14 Again, others claim that it denotes an official of the royal court or perhaps a guardian ( omen) (Num 11:12; 2 Kgs 10:1, 5).15 Whatever the precise sense, it clearly connotes a close tie between monarch and advisor.16

The form '' 'ר' (in Hebrew) has a double meaning and it can also have a negative sense, as in the word רַע ('evil'). This is evident in Jer 9:3[4]): "Let everyone beware of his friend רעהו and put no trust in any brother; for every brother is a supplanter and every friend רֵ עַ goes about as a slanderer."17

The narrator describes Jonadab as "a very smart (חכם) man"18 but does this refer to native intelligence19 or does it connote a wicked disposition, as asserted by commentators from the Middle Ages to the present-or perhaps guile and deviousness?20

In order to decide whether רֵ עַ and "very smart" are complimentary or derogatory, we should examine Jonadab's interactions with Amnon and David as well as his relationship with Tamar and Absalom.

E COMMON INTERPRETATIONS OF JONADAB'S ADVICE

1 Jonadab's advice to Amnon

Jonadab said to him, "Lie down on your bed, and pretend to be ill; and when your father comes to see you, say to him, 'Let my sister Tamar come and give me bread to eat, and make the food in my sight, that I may watch and eat it from her hand.'" (13:5)

Although the idea is clear here, Jonadab's motives are not.21 Readers may wonder how Tamar's cuisine can help him recover. However excellent the food, it will not satisfy Amnon's illicit passion for his sister.

Before Jonadab makes this suggestion to Amnon we cannot really know whether the two young men are close. On the one hand, Jonadab immediately recognises that his cousin is out of sorts: "Why are you so haggard morning after morning? Will you not tell me?" (v. 4).22 On the other hand, he does not address him by name but by his title of "prince" (v.4). We have no way to determine whether Jonadab's suggestion is crafty and vicious or an innocent idea meant to help a friend in time of need.

1a Innocent advice

Jonadab, who was deeply involved in the affairs of the royal court, was certainly interested in having Amnon, David's first-born son, whom he serves as intimate friend and advisor, inherit the throne. Sensitive to the moods of the heir presumptive, who relies on him and shares his intimate secrets with him, Jonadab would do anything to make him feel better by facilitating a tête-à-tête with Tamar. Jonadab intends no harm to the young woman and has no inkling that Amnon will rape her.23 The blame lies not with Jonadab but with Amnon and subsequently with David, who does nothing to punish the wayward prince (13:21).24

1b Calculated advice

Jonadab advises Amnon to feign illness and deceive his father-a disreputable act in itself. Jonadab, who knows the people he is dealing with, is certain that David, given his generosity and soft spot for his sons, will not deny the ailing Amnon his request.25

1c Machiavellian advice

Jonadab's scheme alleviated Amnon's distress briefly but led to the rape, which Tamar described as a "vile act" that revealed Amnon to be one of the worst "scoundrels in Israel" (vv.12-13).26

Why would Jonadab want to give Amnon bad advice? Perhaps Jonadab made his suggestion without giving adequate thought to its possible consequences because he saw an opportunity to further his own interests.27 He thought that Amnon's joy at intimacy with Tamar would be remembered in his favour when Amnon inherited the throne.28

1d Jonadab as counsellor

But Jonadab the son of Shimeah, David's brother, said, "Let not my lord suppose that they have killed all the young men the king's sons. For Amnon alone is dead, as this has been ordained by Absalom since the day he violated his sister Tamar. So let not my lord the king take it to heart and suppose that all the king's sons are dead; for Amnon alone is dead" (vv. 32-33).

Given that the king is his uncle (vv. 3, 32), it is possible that Jonadab regretted his advice to Amnon, which triggered David's abandonment of his daughter to her fate.29 This is why he tried to console the grieving father "so that king would not do evil and destroy himself in his grief, and he [Jonadab] would be the cause of [harm] to David as well."30

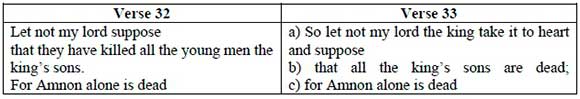

A close reading of Jonadab's words to David (vv. 32-33) reveals their bipartite structure:

a) "Let not my lord suppose

b) that they have killed all the young men the king's sons.

c) For Amnon alone is dead, as this has been ordained by Absalom since the day he violated his sister Tamar.

a) So let not my lord the king take it to heart and suppose

b) that all the king's sons are dead;

c) for Amnon alone is dead."

Jonadab's explanation of Absalom's motive for killing Amnon, which comes at the hinge of the repetitive structure, highlights the guilty party- Absalom.31The style here is marked by repetition. Three times, in his soothing words to David, Jonadab repeats that that king's sons are alive; twice he says that Amnon is dead.32

Absalom's flight is mentioned twice: Absalom fled (v. 34) and "Absalom had fled" (v. 37).33

Although the larger context (chapter 13) is also full of repetitions, this episode stands out in that the repetition is spoken by a single individual (Jonadab) and not by multiple characters, as previously when Jonadab makes his suggestion to Amnon (vv. 3-5), Amnon repeats the idea to David (v. 6) and David repeats it to Tamar (v. 7).

This episode also highlights the character's emotional reactions: "The king arose and rent his garments, and lay on the ground" (v. 31); "the king's sons came and lifted up their voice and wept; and the king also and all his servants wept very bitterly" (v. 36). This contrasts with the other episodes in the chapter, which downplay emotions. Absalom does not react when he learns that Amnon has raped his sister (v. 20); and of David, too, we are told only that "he was very angry" (v. 21).

The only way to get inside Jonadab's head is to consider his relations with the other members of the royal court.

F JONADAB AND THE OTHER CHARACTERS

1 Jonadab and Amnon

Some scholars hold that Jonadab knew very well what Amnon was planning to do to Tamar. Others believe that his suggestion was an innocent attempt to help his friend. Did Jonadab set up Amnon to behave like a "scoundrel" or was Amnon responsible for his own actions?

It is clear from what Jonadab tells David in the later episode (vv. 30-37) that he knew that Absalom had been plotting Amnon's death (v. 32). From his words we may infer something about Jonadab's relationship with Amnon. If they were close why did Jonadab not warn his friend not to attend Absalom's feast or perhaps go with Amnon to protect him?34 There can be no doubt that Jonadab's failure to warn Amnon reflects bad blood between the cousins.

2 Jonadab and Tamar

Although there is no direct contact between Jonadab and Tamar, his advice to Amnon proved devastating for her. All three-Amnon, Absalom and Tamar- were Jonadab's first cousins. Therefore, it is somewhat astonishing that he would advise Amnon to abuse her; his suggestion that a virgin princess whose freedom of movement in the royal palace is limited should come to a man's bedroom- even if he is her half-brother-is most problematic. It is hard to see it as innocent.35 An idea that will benefit one person at another's expense casts a cloud on its originator's ethics. Thus, Jonadab is not exempt from blame and we do not see anything positive in his relationship with Tamar.

3 Jonadab and David

Readers certainly wonder why Jonadab, David's nephew, did not share his feelings with David from the outset. Why did his conscience not prick him when he failed to warn him of Absalom's plot and in effect allowed Amnon and his brothers to attend the sheep-shearing at Baal Hatzor, even though he knew of Absalom's plot (v. 32)? Furthermore, his attempt to relieve David's distress by reassuring him that only Amnon was dead and not the other princes is in bad taste. Amnon was David's first-born; the king would certainly grieve deeply at his loss. Jonadab was displaying extreme insensitivity to David's feelings. Perhaps Jonadab meant to reprove the king who did not lift a finger to punish Amnon so that his passivity forced Absalom to act. Amnon sinned and died justly for his sin. Given the king's inaction, Absalom had no choice but to redeem his sister's shame, kill his brother and seek refuge at his grandfather's court.36

4 Jonadab and Absalom

Absalom's thirst for revenge, along with the knowledge that Amnon's death will leave him first in the line of succession, is evident (2 Sam 13:21-23, 32; 15:16). We may conjecture that Jonadab knew that Absalom coveted the throne and made no attempt to frustrate his design to eliminate Amnon. It is even plausible that Absalom and Jonadab collaborated to get rid of him, taking advantage of his weak character.37 Jonadab certainly could see that Absalom was a more suitable candidate for the throne after David;38 hence he collaborated with Absalom39 and even tried to justify the murder of Amnon to David.40 Absalom and Jonadab's calculated scheme is reflected in the rhetorical question the former addresses to Tamar after the rape: "Has Amnon your brother 'been with you'?" (v. 20). Then, without waiting for an answer, he continues, "Say nothing, now, my sister."41There is no hint of brotherly feeling for a sister who has just been brutalised and whose future prospects have been destroyed. As the story progresses, too, we may assume that Jonadab was aware of Absalom's intention to kill Amnon.42 He nonetheless allowed two years to pass without warning him.43 This is the only way to explain Jonadab's knowledge of Amnon's death before the news reached Jerusalem and David (v. 32) and that the other princes would be returning home safely (v. 35) before David and his courtiers saw them: "And as soon as he had finished speaking, the king's sons came" (v. 36).

Our examination of Jonadab's character and of his relations with Amnon, Tamar, Absalom and David has not led us to a decisive conclusion as to whether he is a decent fellow or a rogue. Thus, we need to consider his role in the story.

G JONADAB'S ROLE IN THE STORY

Why is Jonadab part of the cast of our story? What essential role does he play in the narrative? If he is a supporting character, he must advance the plot in some way or give the story more significance and depth;44 or is his role merely to shed light on the main characters-a bit player in a political drama?

Jonadab is a flat, static character in the "rape of Tamar." He does not stand on his own and is only a "friend" (according to the narrator, v. 3) or the king's "servant" (as he calls himself, v. 35). In both cases he is in the company of men who are in pain, advising Amnon and consoling David.45 This suggests that Jonadab's part in the story is to facilitate a moral assessment of the protagonists.

If Jonadab is an admirable character, it is understandable that he functions to blacken the main actors, Amnon and David.46 Jonadab is the antithesis of Amnon and overshadows him in the first episode. Amnon is helpless; his emotional state has affected his physical health. The resourceful Jonadab offers him a way to recover. Amnon is not as clever as his cousin. The contrast between the two highlights Amnon's impotence and demonstrates that, primogeniture notwithstanding, he is not a worthy successor to David.

In the second episode, Jonadab is contrasted with David. He calmly comforts his anguished uncle. Jonadab who knows (that only Amnon is dead and that Absalom had plotted his murder) is contrasted with David who is ignorant. He dares blame the king, albeit indirectly, for what has happened-because he refrained from punishing Amnon, who raped Tamar, Absalom had to avenge the crime himself.47

In our analysis thus far, we have been unable to reach a firm conclusion about Jonadab's character and whether his presence is essential to the narrative. We are left to seek the solution in the multiple layers of the text, asking whether Jonadab belongs to the primary layer or a later addition-whether he is a member of the original cast or a walk-on player. This will give us a different perspective of his character and whether he is essential to the plot.48

G TEXTUAL LAYERS IN THE RAPE OF TAMAR (2 SAM 13:1-39)

It is possible to identify two textual layers in the Rape of Tamar-the original story, composed by the author49 who first set down the story but without Jonadab; and the later accretions by the editor, who brings Jonadab into the narrative.50

1 The first episode, without Jonadab (2 Sam 13:1-2, 6-7)

(1) Now Absalom, David's son, had a beautiful sister, whose name was Tamar; and after a time Amnon, David's son, fell in love with her. (2) And Amnon was so tormented that he made himself ill because of his sister Tamar; for she was a virgin, and it seemed impossible to Amnon to do anything to her. (6) Amnon lay down, and pretended to be ill; and when the king came to see him, Amnon said to the king, "Pray let my sister Tamar come and make a couple of cakes in my sight, that I may eat from her hand." (7) Then David sent home to Tamar, saying, "Go to your brother Amnon's house, and make food for him."

Jonadab's advice is readily given and readily accepted but, as we see here, it can be left out of the story without detracting from the plot. Amnon falls ill, the king comes to visit his firstborn, the prince suggests a remedy to David and the latter consents.

2 The last episode, without Jonadab (vv. 23-29, 38-39)

(23) Two years later, when Absalom was having his flocks sheared at Baal-hazor near Ephraim, Absalom invited all the king's sons. (24) And Absalom came to the king, and said, "Your servant is having his flocks sheared. Pray let the king and his servants go with your servant." (25) But the king said to Absalom, "No, my son, let us not all go, lest we be a burden to you." He pressed him, but he would not go but gave him his blessing. (26) Then Absalom said, "If not, pray let my brother Amnon go with us." And the king said to him, "Why should he go with you?" (27) But Absalom pressed him until he let Amnon and all the king's sons go with him. (28) Then Absalom commanded his servants, "Mark when Amnon's heart is merry with wine, and when I say to you, 'Strike Amnon,' then kill him. Fear not; for I am commanding you. Be courageous and act valiantly." (29) So Absalom's servants did to Amnon as Absalom had commanded. Then all the king's sons arose, and each mounted his mule and fled." (38) Absalom had fled and went to Geshur, and was there three years. (39) And King David was pining away for Absalom, for [the king] had gotten over Amnon's death.

As we see, it is not really important that Jonadab knew of Absalom's plan to avenge his sister's rape but kept silent for two years or that he consoled David that only Amnon was dead. The story is perfectly coherent without Jonadab. Absalom's retainers kill Amnon, the other princes flee for their lives and reach their father's palace and all mourn the dead man.

We see that the author's account is complete even if we delete the verses that relate to Jonadab (vv.3-5, 30-37). His story, which did not include the two episodes in which Jonadab appears, depicts the House of David in all its nakedness-one son rapes his half-sister but David does nothing. Another son avenges his sister's honour, kills the rapist and runs away to escape punishment.51 This is the retribution that Nathan announced to David after Uriah's death (2 Sam 12:10). There is no need to involve Jonadab in the events.

What is more, the unfavourable portrayal of the main players-David, Amnon and Absalom-can be seen as legitimising Solomon's eventual accession to the throne.52 For this, too, Jonadab is superfluous.

The editor who wove Jonadab's two episodes (vv. 3-5 and 30-37) into the narrative continued the author's narrative line and style:

1) The note about the watchman (v. 34)53 highlights the editor's ability to forge a logical continuity between the original story and the Jonadab episode-the king's sons flee (original text, v. 29), the rumour of their death spreads (added by the editor, v. 30), Jonadab refutes the rumour (vv. 32-33). The watchman, newly recruited into the story, is the hinge on which Jonadab's account turns,54linking the hearsay report (vv. 30, 32-33) to its visual corroboration (vv. 35-36).55

2) The two writers also share vocabulary. The author employs vayhi twice (vv. 1, 23) to mark the start of a new episode. The editor also uses it twice (vv. 30, 36) for the same purpose. Where the latter sought to begin a new episode in the middle of a continuous story, he used this word to suture the new material to the original text.56

3) Chiastic repetition:

"It seemed impossible in Amnon's eyes to do (לעשות) anything to her" (author, v. 2)

"... and make (עשתה) the food in front of my eyes" (editor, v. 5)

4) The author twice employs the root '"חל in the hitpael, with the sense of feigning illness, in vv. 2 and 6. The editor also uses it, in v. 5.

5) Repetition of the collocation בן/בני הַמלך "the king's son(s)."57 In the first episode, the editor has Jonadab call Amnon "son of the king" (v. 4); in the second episode, the same collocation appears five times (vv. 30, 32, 33, 35, 36), spoken three times by Jonadab and twice employed by the narrative voice. There is good reason for this repetition, namely, the editor's desire to use the same terminology without leaving tracks.

6) Condensation of events: The author recounts the rape in great detail (vv. 817). The editor summarises it in a single clause (v. 32b) spoken by Jonadab but employing the same harsh words that emphasised the seriousness of the deed. The editor's word choice is a chiastic echo of the author's:

The editor: "as this has been ordained by Absalom since the day he violated his sister Tamar" (v. 32b).

The author: Absalom (v. 1) his sister Tamar (v. 2) he violated her (v. 14).

Despite the editor's attempts to create a seamless whole with the original text, he left some identifiable gaps in the web:

1) "And as soon as he had finished speaking" (36aa) is a secondary editorial link.58 The function of this clause is to tie the events together and insert Jonadab into the story. The rumours have left David anxious about all his sons (v. 30). Jonadab tells David that he need not worry because only Amnon is dead (vv. 32-33). No sooner does he say this than the princes appear on the scene. Despite the initial impression that the clause creates a smooth link between Jonadab's consoling news and the young men's arrival, the connection is clearly artificial. The editor's effort to make Jonadab's remark a natural part of the narrative sequence does not really work. The linking clause (v. 36a) produces an illogical sequence of events. Jonadab announces "Look, the king's sons have come; as your servant said, so it has come about" (v. 35). In other words, Jonadab is actually announcing what has already happened-the princes have arrived just as he promised they would but they show up only after this: "And as soon as he had finished speaking the king's sons came" (v. 36). We would have expected to be told of their arrival and only then to hear Jonadab boast that he had been right. The illogical sequence betrays the editor's handiwork.

2) When David hears the rumour that all his sons are dead, his response is to rend his garments and lie on the ground (v. 31).59 This behaviour is quite out of keeping with his reaction to similar tragedies elsewhere in 2 Samuel.60 For example, when Bathsheba's infant lies critically ill, "David fasted, and went in and lay all night on the ground" (2 Sam 12:16). However, when the child succumbs, "David arose from the ground, and washed, and anointed himself, and changed his clothes; ... and when he asked, they set food before him, and he ate" (v. 20). To his courtiers, who are puzzled by his composure, he explains his actions:

"While the child was still alive, I fasted and wept; for I said, 'Who knows whether the Lord will be gracious to me and the child may live?' But now he is dead; why should I fast? Can I bring him back again? I shall go to him, but he will not return to me." (12:22-23).

If this is how David perceives the world, why does he go into deep mourning when he hears that his sons are dead (13:31)? He knows that his tears are fruitless. The contrast between David's different reactions in these two cases may lead us to suspect that the verse is an editorial insertion and not part of the author's original text.

3) Another problem is created by the close repetition of the information that Absalom fled and went to Geshur-"Absalom had fled and went to Talmai the son of Ammihud, king of Geshur" (v. 37)-seems superfluous given that the same information appears in the very next verse: "Absalom had fled and went to Geshur" (v. 38).

H WHY THE EDITOR ADDED THE JONADAB EPISODES (13:3-5 AND 30-37) TO THE STORY

Firstly, the editor was merely carrying the author's line a step further.61 The author wanted to show that David's heirs were not fit to inherit his crown- neither the first-born nor the next in line; the editor added Jonadab's two episodes to blacken them further and strengthen the author's point even more persuasively.62 The author wanted to highlight the divine plan for Solomon to sit on the throne; the editor inserted Jonadab as a pawn in the divine plan to destroy Amnon and Absalom and legitimise Solomon's succession.

It is also possible that the editor was a staunch defender of David and trying to cover up his family's shortcomings.63 He did this by making Jonadab the main actor in his two episodes. Jonadab satisfies the criteria-quantitative, structural and thematic prominence-for a main character in specific contexts.64This does not mean that Jonadab is not a secondary character in the broader context, outside his two brief moments in the limelight. This argument is supported by Perry and Sternberg who note that: "Many characters who are secondary in the context of an entire book, or a particular story cycle, may escape their secondary status and become central figures in more limited contexts. Their status as primary or secondary is thus dynamic."65 In the first episode here, the editor makes Jonadab the main character, not to overshadow Amnon's despicable action but to cast the blame on someone else-Jonadab-and thus lessen the wickedness of David's firstborn son.

In the second episode, Jonadab again has a star role. This time the goal is to minimise David's indirect responsibility for the rape of Tamar and for Absalom's murder of Amnon as well as to cast the blame for the bloodshed on Absalom. If this was the editor's intention, we believe that he came up short. In his version, Jonadab was indeed the originator of the scheme that got Tamar into Amnon's room but it was Amnon who raped and then humiliated his half-sister. It does not matter that someone else thought up a way to get Tamar to sit on Amnon's bed. The core of the matter is the rape itself, for which Amnon bears sole responsibility.

In the second episode also, the editor was unsuccessful. There is no way to paper over David's responsibility for Tamar's misadventure and his failure to punish or at least admonish Amnon. What is more, the fact that in the first episode the editor has Jonadab address Amnon as "son of the king" (v. 4) supports our view. The formal title seems unnecessary, when Jonadab could just as well have addressed his friend by his name, Amnon.

In conclusion, all our attempts to assess the moral fibre of Jonadab, who could be said to "strut and fret his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more," have been unsuccessful. We see him as a complex and ambiguous figure whose true nature is hard to extract.66 The only certain conclusion we can reach is that the two Jonadab episodes are not essential to the story and that the author's original version was adequate for achieving his goal.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackerman, James S. "Knowing Good and Evil: A Literary Analysis of the Court History in 2 Samuel 9-20 and 1 Kings 1-2." Journal of Biblical Literature 109/1 (1990): 41 -60. [ Links ]

Ackroyd, Peter R. The Second Book of Samuel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977. [ Links ]

Amit, Yairah. 2 Samuel. Olam Hatanakh. Tel Aviv: Davidson-Ittai, 1996 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

__________________. The Book of Judges: The Art of Editing. Translated by Jonathan Chipman. Leiden: Brill, 1999. [ Links ]

__________________. Hidden Polemics in Biblical Narrative. Leiden: Brill, 2000. [ Links ]

__________________. Reading Biblical Narratives. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2001. [ Links ]

__________________. In Praise of Editing in the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Phoenix, 2012. [ Links ]

Ararat, Nisan. "The Story of Amnon and Tamar." Beit Miqra 95/4 (1983): 331-357 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

__________________. Truth and Grace in the Bible. Jerusalem: Eliner, 1993 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Auld, A. Graeme. I & II Samuel: A Commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2011. [ Links ]

Bakon, Shimon. "Jonadab, 'Friend' of Amnon." Jewish Biblical Quaterly 43/2 (2015): 101 -105. [ Links ]

Baldwin, Joyce G. 1 and 2 Samuel. Bristol: InterVarsity Press, 1988. [ Links ]

Bar-Efrat, Shimon. Narrative Art in the Bible. Sheffield: Almond, 1989. [ Links ]

__________________. "King David Was Pining away for Absalom, for He Had Got over Amnon's Death." Pages 613-621 in The Bible in the Light of Its Interpreters. Edited by Sara Japhet. Jerusalem: Magnes, 1994 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

__________________. 2 Samuel. Mikra L'Yisrael. Jerusalem: Magnes, 1996 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Bartal, Arye. "The Advice of Jonadab ben Shameah." Pages 184-190 in Dr. Baruch Ben Yehuda Volume. Edited by Ben-Zion Luria. Tel Aviv: Israel Society for Biblical Research, 1981 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Ben-Reuven, Sarah. "The Rape of Dinah and Its Reflections." Beit Miqra 43/3-4 (1998): 319-322 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Brin, Gershon. "The Title בן )ַה(מלך and Its Parallels: The Significance and Evaluation of an Official Title." AION 29 (1969): 433-465. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. First and Second Samuel. Louisville: John Knox, 1990. [ Links ]

Buber, Martin. "The Story of Saul's King." Tarbiz 22 (1953): 65-84 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Campbell, Antony F. 2 Samuel. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005. [ Links ]

Conroy, Charles. Absalom, Absalom! Narrative and Language in 2 Sam 13-20. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1978. [ Links ]

Driver, Samuel Rolles. The Books of Samuel. London: Oxford University Press, 1913. [ Links ]

Ehrlich, Arnold. Mikra ke-feshuto. Berlin: M. Papfeloyer, 1900. [ Links ]

Fokkelman, Jan P. Narrative Art and Poetry in the Books of Samuel. 2 vols. Maastricht: Assen, 1981. [ Links ]

Galpaz-Feller, Pnina. Vayoled: Relations between Parents and Children in Biblical Stories and Laws. Jerusalem: Carmel, 2006. [ Links ]

Garsiel, Moshe. The Book of Samuel: The Story and History of David and His Kingdom. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass, 2018. [ Links ]

Hertzberg, Hans Wilhelm. I & II Samuel. OTL. London: SCM, 1964. [ Links ]

Kaddari, Menahem Zvi. Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew. Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University, 2006 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Keil, Carl Friedrich and Franz Delitzsch. The Books of Samuel. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1950. [ Links ]

Keys, Gillian. The Wages of Sin. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Kiel, Yehuda. 2 Samuel. Da'at Miqra. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1981. [ Links ]

Klaus, Nathan. "Simultaneous Events in the Bible." Beit Miqra 36/4 (1991): 382-388 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Laniado, Samuel. Kliyaqar. Jerusalem: Haktav, 1992 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Loewenstamm, Samuel A. "The Death of the Fathers of the Nation." Pages 104-123 in Bible and Jewish History: Studies in Bible and Jewish History Dedicated to the Memory of Jacob Liver. Edited by Benjamin Uffenheimer. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 1972 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Mauchline, John. 1 and 2 Samuel. London: Oliphants, 1971. [ Links ]

McCarter, P. Kyle. 2 Samuel. AB. Garden City: Doubleday, 1984. [ Links ]

Mettinger, Tryggve N.D. Solomonic State Officials: A Study of the Civil Government Officials of the Israelite Monarchy. Lund: Gleerup, 1971. [ Links ]

Miller, Robert. D. "Jonadab." The Anchor Bible Dictionary 3:936, Doubleday, New York, 1992. [ Links ]

Morrison, Craig E. Berit Olam: 2 Samuel. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Payne, David F. I & II Samuel. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1982. [ Links ]

Perry, Menahem and Meir Sternberg. "Caution, Literature! On Problems in the Interpretation and Poetics of the Biblical Tale." Hasifrut 3 (1970): 637-638 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Polak, Frank. Biblical Narrative: Aspects of Art and Design. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1994. [ Links ]

Rofé, Alexander. Introduction to the Literature of the Hebrew Bible. Jerusalem: Simor, 2009. [ Links ]

Safran, Jonathan. "Ahuzzath and the Pact of Beersheba." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 101/2 (1989): 184-198. [ Links ]

Segal, Moshe Zvi. The Books of Samuel. Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1971 (Hebrew). [ Links ]

Selms, Adrianus van. "The Origin of the Title 'The King's Friend,'" Journal of Near Eastern Studies 16/2 (1957): 118-123. [ Links ]

Simon, Uriel. Reading Biblical Narratives. Translated by Lenn J. Schramm. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Sternberg, Meir. The Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Weiss, Meir. The Bible from Within: The Method of Total Interpretation. Jerusalem: Magnes, 1984. [ Links ]

Wesselius, Jan-Wim. "Joab's Death and the Central Theme of the Succession Narrative (2 Samuel IX-1 Kings II)." Vetus Testamentum 40/3 (1990): 336-351. [ Links ]

Submitted: 02/04/2021

Peer-reviewed: 16/11/2021

Accepted: 22/11/2021

Dr. Orly Keren is Vice-President and a lecturer of Biblical Studies in Kaye Academic College of Education in Beer-Sheva, Israel. E-mail: orlyke@kaye.ac.il ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2864-6746.

Dr. Hagit Taragan is a lecturer of Biblical Studies in Kaye Academic College of Education in Beer-Sheva, Israel. E-mail: targan@bgu.ac.il ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0891-810X.

* This article is based on a lecture given at The Seventeen World Congress of Jewish Studies (2017).

1 "Total interpretation" is used here as defined by Meir Weiss, The Bible from Within: The Method of Total Interpretation (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1984).

2 As Polak defines it, "close reading" is an examination of the function of every narrative element during the analysis of the text as we have it in front of us; Frank Polak, Biblical Narrative: Aspects of Art and Design (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1994), 424 (Hebrew). See also Charles Conroy, Absalom, Absalom! Narrative and Language in 2 Sam 13-20 (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1978), 17.

3 Conroy, Absalom, 18, emphasises the importance, after the initial stage of analysing the text through a close reading, of proceeding to the state of textual analysis: "a deep-level statement of the same material' in order to identify the layers in the text."

4 "Every scholar and every study make their own decisions about where to set the boundary stones, and are certainly entitled to do so-on condition that they take into account, explicitly or implicitly, all of the contexts, narrow and broad, of which the unit is a part"; Menahem Perry and Meir Sternberg, "Caution, Literature! On Problems in the Interpretation and Poetics of the Biblical Tale," Hasifrut 3 (1970): 632 (Hebrew). They go on to enumerate the criteria for delimiting an episode. See also Yairah Amit, Reading Biblical Narratives (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2001), 18.

5 According to Joseph Kara, “morning after morning” does not mean that he was haggard or dejected only in morning and not the rest of the day. Rather, every morning Jonadab inquired why Amnon looked so wan.

6 For the sequence, see Perry and Sternberg, “Caution, Literature!,” 633–634.

7 See Antony F. Campbell, 2 Samuel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 127.

8 The qere here is שמעה, however.

9 The long form Jehonadab occurs only once (2 Sam 13:5). Some MSS of the LXX (Cod. Vaticanus) read Jehonadab. In the Lucianic recension of the LXX, 4QSam and Josephus' Antiquities, his name is given as Jonathan.

10 On the basis of 2 Sam 21:21-"Jonathan the son of Shime'i, David's brother, slew him"- Segal argues that Shimeah may have had two sons; Moshe Zvi Segal, The Books of Samuel (Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1971), 310 (Hebrew). Bar-Efrat and McCarter also maintain that Jonadab and Jonathan were brothers; Shimon Bar-Efrat, 2 Samuel, Mikra L'Yisrael (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1996), 131 (Hebrew); P. Kyle McCarter, 2 Samuel (AB; Garden City: Doubleday, 1984), 451. Amit notes further that Jonadab did not have the reputation of a warrior but his brother Jonathan was a hero who killed one of the sons of Harafah in Gat (2 Sam 21:20-22; 1 Chron 20:7); Yairah Amit, 2 Samuel (Olam Hatanakh; Tel Aviv: Davidson-Ittai, 1996), 123 (Hebrew).

11 If we identify him with Jonathan, then, we should note that he is mentioned once without specification of his father (2 Sam 23:32) and once with him (1 Chron 11:34). In the Lucianic recension of the LXX, Jonathan's father is called Semaaya.

12 Targum Jonathan shows that שושבינא, generally, is understood as "groomsman," according to Lucian in the LXX translation. See Adrianus van Selms, "The Origin of the Title 'The King's Friend,'" JNES 16/2 (1957): 118-123. Mettinger supports van Selms and claims that the position has to do with a political marriage, common in those times. The role of the רֵ was to advise the king on these matters and accompany him; see Tryggve N. D. Mettinger, Solomonic State Officials: A Study of the Civil Government Officials of the Israelite Monarchy (Lund: Gleerup, 1971), 63-69. According to McCarter, 2 Samuel, 321, who notes that Judg 14:20 and the Akkadian Sumero-Akkadian terminology kuli=ibru (friend), which fits with Gen 38:20, where רעהו appears in the context of a relationship between a man and woman-the reference is to a close friend who advises Amnon on matters of the heart. McCarter adds that the prince's advisor would acquire the official title of "king's friend" when Amnon ascends the throne. See also Peter R. Ackroyd, The Second Book of Samuel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 121.

13 As we have seen, his parentage means that he fulfils this condition; see van Selms, "The Origin," 122.

14 As in Job 2:11, Josephus, Ant. 7.164, takes the word to mean a relative and friend. Cf. Hans Wilhelm Hertzberg, I & II Samuel (OTL; London: SCM, 1964), 320; David F. Payne, I & II Samuel (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1982), 213; Joyce G. Baldwin, 1 and 2 Samuel (Bristol: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 246-247; Yehuda Kiel, 2 Samuel, Da'at Miqra (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1981), 431; Walter Brueggemann, First and Second Samuel (Louisville: John Knox, 1990), 286; Robert D. Miller, "Jonadab," ABD 3:936; Menahem Zvi Kaddari, Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew (Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University, 2006), 1016, 1020 (Hebrew).

15 Moshe Garsiel, The Book of Samuel: The Story and History of David and His Kingdom (Jerusalem: Rubin Mass, 2018), 471. Kiel, 2 Samuel, 431 (on 2 Sam 15:37), argues that the word denotes a court position. Ackroyd, The Second Book of Samuel, 121, believes that Jonadab was Amnon's tutor and could expect to rise to a high rank in the royal administration and serve as the king's confidant. Amit, "The Rape of Tamar," 123, writes that רֵ עַ can be taken not only literally as the prince's friend and companion but also as a court official. In 1 Chron 27:33, Hushai the Archite is named in the list of various functionaries and designated רֵ ע הַמלך It is possible that in David's time, the title was not formal; this seems to be corroborated by its absence from the lists of his officials (2 Sam 8:16-18, 20:23-26). We may conclude that in Jonadab's case, the word means that he was Amnon's counsellor. Under Solomon, Zabud son of Nathan was priest and the king's רֵעֶה (1 Kgs 4:5). This may have been the case with Jonadab and others who held official posts first instituted under David.

16 See Jonathan Safran, "Ahuzzath and the Pact of Beersheba," ZAW 101/2 (1989): 190.

17 Laniado further asserts that originally Jonadab was Amnon's רֵ עַ in order to teach him Torah and that is why he is called Jehonadab, accentuating the theophoric element of his name; but after the bad advice he gave Amnon, he is referred to as Jonadab. Laniado adds that Jehonadab began as a wise and upright man but was "demoted" to Jonadab because of his association with a scoundrel; Samuel Laniado, Kli yaqar (Jerusalem: Haktav, 1992), 243, 244 (Hebrew).

18 Miller, "Jonadab," 936, holds that wisdom should be evaluated on the basis of whether it is good or evil. Bar-Efrat, 2 Samuel, 132, notes that the Bible deems wisdom a positive trait, with moral or religious value (Ps 111:10, Job 28:8). Here, though, Jonadab gives advice that has immoral consequences. Bar-Efrat claims that no moral judgment should be attached to the term here. Translations that render the word here as "crafty" (RSV) or "clever" (NJPS) have already decided that wisdom in the Solomonic sense is not intended.

19 According to Josephus, Ant. 7.164, Jonadab was extremely intelligent and sharp-witted. Malbim (ad loc.) notes that "thanks to his sagacity he perceived that [Amnon] was lovesick." McCarter, 2 Samuel, 321, views the word as indicating a "purely intellectual and morally neutral quality." Bar-Efrat wonders at the epithet he renders as "a very crafty man" attached to Jonadab, given that the counsel he gave Amnon was anything but wise and it is difficult to see him as the prince's friend and he does not appear to have been overly troubled by the consequences of his suggestion. See Shimon Bar-Efrat, Narrative Art in the Bible (Sheffield: Almond, 1989), 246-250. See also Nisan Ararat, Truth and Grace in the Bible (Jerusalem: Eliner, 1993), 264 n. 21 (Hebrew); Yairah Amit, In Praise of Editing in the Hebrew Bible (Sheffield: Phoenix, 2012), 211.

20 For the first view, see Prov 8:12 and 14:8. According to the Talmud (b. Sanh. 21a), Jonadab was "wise in evil counsel" (חכם לַהרע). A long line of commentators-Rashi, David Kimhi, Gersonides and Abravanel-concur in various ways; so does Laniado, Kliyaqar, 243. McCarter, 2 Samuel, 321, rejects this negative interpretation, however. Driver holds that Jonadab was indeed wise; had the narrator intended a negative trait he would have called him ערום, like the serpent in Eden; Samuel Rolles Driver, The Books of Samuel (London: Oxford University Press, 1913), 388. See also Alexander Rofé, Introduction to the Literature of the Hebrew Bible (Jerusalem: Simor, 2009), 517. For the second view, cf. Prov 8:12 and 14:8. Thus, Carl Friedrich Keil and Franz Delitzsch, The Books of Samuel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1950), 397; Hertzberg, I & II Samuel, 320; John Mauchline, 1 and 2 Samuel (London: Oliphants, 1971), 259-264; Payne, I & II Samuel, 213; Baldwin, 1 and 2 Samuel, 246-247; Ackroyd, The Second Book of Samuel, 118, 121; Brueggemann, First and Second Samuel, 286. Driver, The Books of Samuel, 380, disagrees that חכם should be understood in a negative sense. See also Bar-Efrat, Narrative Art, 205.

21 The legitimacy of inferring a character's motives for his actions is based on Bar-Efrat, Narrative Art in the Bible, 77.

22 According to Bar-Efrat (ibid, 251) the use here of the dative li reflects the closeness of the two men: "Even if you can't tell anyone else, you can trust me!"

23 Polak, Biblical Narrative, 271 -272, believes that it is difficult to decipher Jonadab from his deeds but that he is presented as a shady character whose objective was to improve his credit with Amnon. Garsiel, The Book of Samuel, 473, notes that Jonadab's advice was not meant to disguise a plan to rape Tamar but only to facilitate a meeting between the two young people so that David would become aware that Amnon was in love with her and take steps to marry her.

24 See Arye Bartal, "The Advice of Jonadab ben Shameah," in Dr. Baruch Ben Yehuda Volume (ed. Ben-Zion Luria; Tel Aviv: Israel Society for Biblical Research, 1981), 184-185 (Hebrew).

25 See Ararat, Truth and Grace in the Bible, 249; Shimon Bakon, "Jonadab, 'Friend' of Amnon," JBQ 43/2 (2015): 101. Galpaz-Feller maintains that from a comparison of Jonadab's idea as reported by himself, by Amnon and by David, we learn that his is the lengthiest, which attests to complex and detailed planning; Pnina Galpaz-Feller, Vayoled: Relations between Parents and Children in Biblical Stories and Laws (Jerusalem: Carmel, 2006), 123-124 (Hebrew).

26 James S. Ackerman, "Knowing Good and Evil: A Literary Analysis of the Court History in 2 Samuel 9-20 and 1 Kings 1-2," JBL 109/1 (1990): 56.

27 According to Campbell, 2 Samuel, 127, a good advisor can see ahead and have an idea of the outcome of his counsel. This is also the view of Conroy, Absalom, 25. Garsiel, The Book of Samuel, 473, asserts that the point of Jonadab's idea was to permit a relatively long meeting-enough time to prepare the food and eat it-between Amnon and Tamar. The protracted stay in his company might have made her fall in love with him.

28 See Miller, "Jonadab," 936. In addition, Jonadab was trapped by the conflict between his true friendship for Amnon and his duty to avenge his brother's death (assuming that Jonadab and Jonathan were siblings) as a result of David and Joab's plot against Uriah (2 Sam 11:15). The fact that he could not act against the king directly led him to do so indirectly through the questionable and harmful advice he gave to David's first-born son and heir. See Jan-Wim Wesselius, "Joab's Death and the Central Theme of the Succession Narrative (2 Samuel IX-1 Kings II)," VT 40/3 (1990): 350-351.

29 Auld disagrees, holding that Jonadab knew precisely what he was doing and what the repercussions would be; A. Graeme Auld, I & II Samuel: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2011), 219.

30 Thus, Arnold Ehrlich, Mikra ke-feshuto (Berlin: M. Papfeloyer, 1900), 221 ebrew (H). Kiel, 2 Samuel, 437-438, counters that Jonadab boasts to David that he knew all along that only Amnon was dead (2 Sam 13:33), which has now become clear to everyone (v. 35) and that this boastfulness reflects negatively on his character.

31 Bar-Efrat, 2 Samuel, 142. See also Keil and Delitzsch, The Books of Samuel, 403. Ben-Reuven asserts that Jonadab's later statement (v. 32) paints Absalom in a different light. The motive for Amnon's murder was purely revenge and not to eliminate him from the line of succession; Sarah Ben-Reuven, "The Rape of Dinah and Its Reflections," Beit Miqra 43/3-4 (1998): 322 (Hebrew).

32 According to Fokkelman, the variation in the phrasing of Jonadab's two statements that the princes are alive attests to the importance he attaches to this. See Jan P. Fokkelman, Narrative Art and Poetry in the Books of Samuel (2 vols.; Maastricht: Assen, 1981), 1:120.

33 See Shimon Bar-Efrat, "King David Was Pining away for Absalom, for He Had Got over Amnon's Death," in The Bible in the Light of Its Interpreters (ed. Sara Japhet; Jerusalem: Magnes, 1994), 613-614 (Hebrew).

34 One could argue that Jonadab was not invited to Absalom's feast because of his relationship with Amnon, the heir.

35 Ararat, Truth and Grace, 246-47, believes that Jonadab and Absalom plotted together to sacrifice Tamar in order to facilitate her brother's accession to the throne at Amnon's expense.

36 Nisan Ararat, "The Story of Amnon and Tamar," Beit Miqra 95/4 (1983): 354 (Hebrew).

37 See Bakon, "Jonadab, 'Friend' of Amnon," 105.

38 Jonadab had political ambitions and sought to guarantee his future prominence as King Absalom's רע. We can only conjecture where he ended up because after this incident, he vanishes from the biblical record. He may have died during Absalom's three-year exile in Geshur or perhaps Absalom dropped him after he returned to Jerusalem.

39 According to Ararat, "The Story of Amnon and Tamar," 245-47, Jonadab allied himself with Absalom because he felt slighted at the court of David, his uncle and only pretended to be Amnon's friend.

40 See Ackerman, "Knowing Good and Evil," 46.

41 See Galpaz-Feller, Vayoled, 127.

42 Bakon, "Jonadab, 'Friend' of Amnon," 103. Mauchline, 1 and 2 Samuel, 262, believes that Jonadab could have anticipated what was going to happen at Absalom's feast. While he evidently knew that Absalom was looking for a way to avenge his sister's rape, he had no claims against the other princes. He could thus infer that the reports of their death were untrue.

43 Kiel, 2 Samuel, 437-438. Bakon, "Jonadab, 'Friend' of Amnon," 104, maintains that it was the rape that made Jonadab decide to abandon Amnon and join Absalom's camp.

44 Uriel Simon, Reading Biblical Narratives (trans. Lenn J. Schramm; Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), 266. Even if Jonadab does not do this, as we would expect of a supporting figure, the narrator's treatment of him as such is unmistakable.

45 Uriel Simon, Seek Peace and Pursue It (Tel Aviv: Yedioth Ahronoth/Sifrei Hemed, 2002), 115 (Hebrew). See also Bar-Efrat, Narrative Art, 245-246; Campbell, 2 Samuel, 125-127.

46 Is this plausible even if we take Jonadab as a negative character? Can a negative minor character blacken the image of another character as well?

47 Morrison emphasises that the mere fact that Jonadab knew that only Amnon had been killed is proof of his acuity. This contrasts with David, who never realised that Absalom would want to avenge his sister's dishonour. Morrison stresses that nowhere are we told that David was "wise," whereas Jonadab is "very smart" (13:3). See Craig E. Morrison, Berit Olam: 2 Samuel (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2013), 118.

48 We need to understand the goals of both the author and the editor in writing a story without Jonadab and inserting him into the plot, respectively. Polak, Biblical Narrative, 262, notes that it is difficult to detect any change in Jonadab. A pre-condition for doing so is whether the episodes that present the character are all of a piece and a coherent unit or form a story assembled from multiple sources or traditions.

49 In biblical scholarship, the originator of the text is referred to as the "writer" or the "author." See, e.g., Bar-Efrat, Narrative Art, 43; Meir Sternberg, The Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 32-35; Polak, Biblical Narrative, 342-43; Amit, Reading Biblical Narratives, 94.

50 The editor is a real person who worked with written texts and revised an existing work. The major difference between the editor and the author is that the former produced a new freestanding continuous tale whereas the editor drew on existing material. The editor creates a new narrator who as it were retells the story set down by the author and adds new layers to it. See Martin Buber, "The Story of Saul's Kingdom," Tarbiz 22 (1953): 79 (Hebrew); Yairah Amit, The Book of Judges: The Art of Editing (transl. Jonathan Chipman; Leiden: Brill, 1999), 15.

51 Gillian Keys, The Wages of Sin (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996), 45.

52 Hertzberg, I & II Samuel, 322, asserts that 2 Sam 7 paints a divine plan that is realised, which is that Solomon will inherit the throne and not Amnon or Absalom.

53 Driver, The Books of Samuel, 303, argues that the reference to Absalom's flight in v. 34 interferes with the continuity and is recapitulated in v. 37a. For Klaus, v. 34 serves to convey a simultaneous action, linking the two reports of Absalom's flight: "in the meantime King David had found out that 'only' Amnon was dead and not all his sons"; Nathan Klaus, "Simultaneous Events in the Bible," Beit Miqra 36.4 (1991): 382-88 (Hebrew).

54 Fokkelman, Narrative Art, 121.

55 The LXX (Cod. Vaticanus) has the watchman report verbally to David and not only see the approaching rout: "and the watchman came and told the king, and said, I have seen men by the way of Oronen, by the side of the mountain: (ἐν τῇ καταβάσει καὶ παρεγένετο ὁ σκοπὸς καὶ ἀπήγγειλεν τῷ βασιλεῖ καὶ εἶπεν ἄνδρας ἑώρακα ἐκ τῆς ὁδοῦ τῆς Ωρωνην ἐκ μέρους τοῦ ὄρους).

56 Samuel A. Lowenstamm, "The Death of the Fathers of the Nation," in Bible and Jewish History: Studies in Bible and Jewish History Dedicated to the Memory of Jacob Liver (ed. Benjamin Uffenheimer; Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 1972), 114 n. 9 (Hebrew).

57 Brin breaks down "son of the king" into several senses. He concludes that the locution "sons of the king" refers to an administrative position rather than a family relationship to the royal house. See Gershon Brin, "The Title "בן )ַה(מלך and Its Parallels: The Significance and Evaluation of an Official Title," AION 29 (1969): 433-465. We do not believe this corresponds to the plain sense in Scripture for two reasons: first, the rumour is that Amnon is one of those who have been killed (2 Sam 13:30); second, David's severe reaction to the report that the "king's sons" are dead is implausible if the deceased are merely court functionaries. Bakon, "Jonadab, 'Friend' of Amnon," 102, maintains that the reference is to the princes, Amnon's and Absalom's brothers.

58 Examples of additional editorial connectives employed by editors and their function to paper over the seams between disparate elements are found in Deut 31:24 and 1 Kgs 8:54. Fokkelman, Narrative Art, 195, observes that the formula "as soon as he had finished speaking" (1 Sam 18:1), sometimes follows a long speech, as in Exod 31:18, 1 Sam 24:17, 1 Kgs 8:54 and Jer 26:8.

59 Ararat, Truth and Grace, 259, 267 nn. 63-64, links David's reaction to his guilt for permitting Tamar to visit Amnon and allowing Amnon to attend Absalom's feast.

60 See Gersonides and Abravanel, ad loc.

61 See Amit, The Book of Judges, 17-18.

62 Thus Amit, Reading Biblical Narratives, 132, 139.

63 See, e.g., Yairah Amit, Hidden Polemics in Biblical Narrative (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 170, 176-78; Rofé, Introduction to the Literature of the Hebrew Bible, 34-36.

64 Drawing on Perry and Sternberg ("Caution, Literature!," 499-508), Amit, Reading Biblical Narratives, 88, sets forth a number of criteria for defining a main character as thematic, quantitative, structural and focus of interest. In this light, we can see Jonadab as a main character in the episodes where he appears.

65 Perry and Sternberg, "Caution, Literature," 646.

66 Thus, Polak, Biblical Narrative, 133.