Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 no.3 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n3a3

ARTICLES

An Inverted Type-Scene? Setting Parameters around a Jacob Cycle Sister-Wife Story

Joshua Joel Spoelstra

University Of Stellenbosch

ABSTRACT

The sister-wife episodes in Genesis (Gen 12:10-20; 20:1-18; 26:1-13) are well documented in biblical scholarship. Occasionally, an equivalent story in the Jacob cycle (Gen 25-35) is proffered. This essay investigates the tenability of such a proposal. The primary contribution is setting parameters around the proposed germane fourth story, through integrative exegetical methodologies, to properly assess the smattering of resonant motifs common between Gen 29-31 and the standard type-scene. By bracketing the texts anterior and posterior to the sister-wife stories, a common preface and postface emerge: a wife-at-the-well type-scene and the form-critical element of covenant-making, respectively. With this exegetical framing in place, the numerous motifs in the Jacob cycle-typically crafted via inversion- shared with the other sister-wife stories is cogent enough to conclude that there is a viable case of an inverted sister-wife type-scene in Gen 29-31. Furthermore, a hypothetical rationale for its literary inversion is elaborated.

Keywords: Jacob, Sister-wife, Type-scene, Inversion, Laban, Methodology.

A INTRODUCTION

The sister-wife episodes in Genesis are easily discernable (Gen 12:10-20; 20:118; 26:1-13) and well documented in biblical scholarship, whether by historical-critical or new literary methodologies.1 With the protagonist being Abraham, twice and Isaac once, the following components are consistent of each story within the Ancestral History of Gen 12-36:

[1] the patriarch moves into a different region, typically, due to a famine (12:10/ cf. 20:1 / 26:1); [2] there, the patriarch, for fear of his own life, deceives the king, lying that his wife is his sister (12:11-13 / cf. 20:2a / 26:7); [3] in each episode with Abraham, his wife Sarah is taken into the harem of the ruler (12:14-15 / 20:2b); [4] eventually, the ruler learns that the woman in question is the patriarch's wife and often God intervenes with threat of punishment (12:17 / 20:3-7, 17-18 / 26:8); [5] the local king confronts the patriarch, demanding an explanation (12:18-19a / 20:9-10 / 26:9-10); [6] the patriarch's wife is returned and together they are ushered out of the country (12:19b-20a/ cf. 20:14b-15 / cf. 26:11, 16); [7] the patriarch directly or indirectly prospers in the aftermath of the ordeal (12:16, 20b / 20:14a, 16 / 26:12-13).2

Though there are more nuances in these stories and the ordering of the elements is not altogether uniform, these events generally comprise the sister-wife stories.

Occasionally, in addition to the three parallel vignettes featuring Abraham and Isaac, scholars have also proposed the existence of a variation of the sister-wife story in the Jacob cycle (Gen 25-35).3 To detect this theorised sister-wife episode, it must be granted that the usually compact story is stretched throughout the larger corpus where other narratological themes are also developed.4Accordingly, the following aspects in Gen 29-31 are somewhat congruous with those of Gen 12*, 20 and 26*:5 [1] emigration to another land is catalysed by an existential crisis, though instead of famine Jacob flees from threat of death, i.e. Esau's murderous rage (27:41-28:5); [2] the new living situation serves as a safe haven for the protagonist (29:13-14); [3] in that country, there is deception related to the patriarch's wives, particularly, from Laban who may be seen as the local chieftain (29:15-30);6 [4] in time, Jacob departs with his wives (and children) from his father-in-law and Haran with great wealth (31:1-21); [5] part of the separation between patriarch and potentate includes a divine confrontation of the latter, as is the case with Abraham in both instances-especially in Gen 20 (vv.3, 6) where God confronts Abimelech by means of a dream, as well as with Laban (31:24, 29).

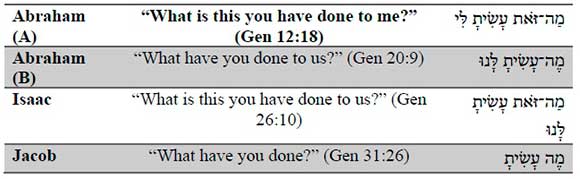

Perhaps the strongest form-critical aspect bearing on the potential Jacob cycle equivalent, though, is the interrogative formulae:7What have you done or What is this you have done?8

This question, asked by the potentate of the patriarch, is a consistent feature in every instance of the sister-wife story as well as in Laban's interrogation of Jacob (though for another reason).9

Are these few elements enough, though, to categorise Gen 29-31 as a sister-wife story? Marian Kelsey proposes viewing Gen 29-31 as an inverted sister-wife story. Under this rubric, several more narratival elements in the Jacob cycle equivalent resonate with the other sister-wife stories (Gen 12*, 20 and 26*). The following observations of inversion from Kelsey and others10substantiate this point: [1] whereas the typical impetus for departure is a famine (12:10 / 26:1), Jacob has been blessed with agricultural prosperity at Isaac's deathbed (27:27-29); [2] Jacob's sojourn from the Promised Land is northward to Haran (28:10) versus southward to Egypt or Gerar (12:10 / 20:1 / 26:1); [3] Jacob lodges with kin (29:13-14) instead of residing with foreigners, as do Abraham and Isaac (12:10 / 20:1 / 26:1); [4] Rachel is beautiful in Jacob's own eyes (29:17-18) as opposed to the rulers who obtain the other matriarchs based on their beauty (12:14-15 / 26:7);11 [5] Jacob's wives are in fact sisters (29:16), instead of misrepresenting wife as sister (12:12-13 / 20:2 / 26:7); [6] whereas the patriarchs usually deceive the ruler regarding their wife (12:11-13 / 20:1b-2a / 26:7), Jacob is deceived by Laban when receiving Leah as wife (29:23-25);12[7] Jacob works for his wealth (30:25-43), while the other patriarchs are typically recompensed (12:16, 20b / 20:14, 16 [contra 26:12-13]); [8] instead of the wife being given back upon realisation of the error (12:19b / 20:14b), in Jacob's case another wife is presented to him (29:27); [9] in contrast to publicly departing from the local ruler (12:20/ cf. 20:15/26:16), Jacob's departure is done in stealth (31:20-22).13

Even the aforementioned interrogative formula in the Jacob cycle is inverted. Before Laban asks, "What have you done?" (מֶה עָשִׂי), in reference to Jacob stealing away with his daughters (Gen 31:26), Jacob had first asked, "What is this you have done to me?" (מַה־זאֹּת עָשִׂיתָ לִׂי) when he realised he was wedded to Leah (Gen 29:25). When charting the inversions in the Jacob cycle vis-à-vis the sister-wife type-scenes of Gen 12*, 20 and 26* a greater coherence is exhibited, albeit secondarily so. Consequently, the case for a Jacob cycle inverted sister-wife story is, prima facie, feasible.14

Nevertheless, as a distinctly redacted corpus of Genesis, the Ancestral History naturally contains salient themes that develop and reverberate throughout Gen 12-36(/50)15 with various degrees of coherence. Genesis 12:13 serves as a programmatic statement governing the plot of the literary block. Indeed, God's three promises to Abraham-land, descendants and blessings-are reiterated to Isaac (Gen 26:4-5) and Jacob (Gen 28:13-14).16 Furthermore, God enters into covenant with Abraham concerning land and the covenantal sign of circumcision relates to his descendants (Gen 15, 17); this slowly yet exponentially materialises throughout the rest of Genesis. Interestingly, Hwagu Kang argues that the three sister-wife type-scenes each develop God's promises of land (Gen 12:10-20), descendants (Gen 20) and blessings (Gen 26:1-13), as per Gen 12:1-3.17 Thus, we are confronted with the challenge of how to distinguish between the echoes of or allusions to divine promises, on the one hand, and an inverted patterned story, on the other hand. An approach that uses integrated exegetical methodologies together with the widening of the scope of the analysis will forge a solution.18

The sister-wife texts of Gen 12*, 20 and 26* have been exegetically examined primarily by the diachronic means of source-, form- and redaction-criticism; the synchronic methodology of type-scene has also generated valuable analytical results. Robert Culley defines type-scenes as "'containing] a given set of repeated elements or details, not all of which are always present, not always in the same order, but enough of which are present to make the scene a recognizable one'."19 Additionally, Robert Alter states that what is most literarily "significant is the inventive freshness with which formulas are recast and redeployed in each new instance."20 Yet, how much latitude may be granted in "inventive freshness" to still qualify as a "recast[ed]" type-scene or how might we access the dialectical tension between literary conventions and creativity?21For instance, even the absence of land, descendants and/or blessings throughout Gen 12-36/50 develops those themes.

One determinative criterion might be the relative length of each narrative one to another. Robert Alter demonstrates how, with the biblical author's expectation of the audience's knowledge of a type-scene, increased brevity usually results in each subsequent iteration of the story.22 Alternatively, Klaus Koch advances that in transmission history, a common narrative form grows from a concise to an expanded style.23 These two positions need not necessarily be mutually exclusive if the literary sequence can be determined.24 Nonetheless, the final form of Genesis does not reveal a pattern according to either of these methodological descriptions-whether the scope is Gen 12*, 20 and 26* or Gen 29-31 is also included.

In what follows, I will establish methodological underpinnings to scrutinise the proposed Jacob cycle sister-wife story, chiefly via type-scene and form criticism.25 My main objective is to examine the texts anterior and posterior to the Jacob sister-wife story in order to set narratival parameters;26 with a common preface and postface surrounding the sister-wife stories,27 the textual unit of the sister-wife type-scene (inverted or otherwise) becomes buttressed. With clear and compounded textual poles fixed, the congruous sister-wife motifs in Gen 29-31 renders an inverted sister-wife type-scene in the Jacob cycle feasible,28 whereas the broader themes therein contribute to the divine promises of Gen 12:1-3.29 Lastly, I will proffer a hypothesis for why the sister-wife type-scene is intentionally crafted in an inverted manner in the Jacob cycle (Gen 2535).

B SETTING PARAMETERS

To evaluate the potentially inverted Jacob cycle sister-wife type-scene, parameters must be marked within the broad range of Gen 25-35-both its anterior and posterior episodes. In short, the preface and postface episodes often common to Gen 12*, 20 and 26* and the Jacob cycle are the wife-at-the-well type-scene and the form-critical feature of covenant making, respectively. By establishing these demarcations, the enclosed material is better framed for comparative analysis.

1 Preface

While the sister-wife type-scene commences with the patriarch departing to a foreign land with his wife, Jacob does not at first have a wife. However, on journeying to Haran, he meets Rachel at a well and a familiar wife-at-the-well or betrothal type-scene unfolds (Gen 29:1-12). Other instances of this type-scene include that of Moses in Exod 2:15-22 and of Abraham's servant who is commissioned to find a wife for Isaac in Gen 24, which in effect suggests that he is Isaac's representative in the said type-scene. In the type-scene, the fateful meeting of a young woman at a well culminates in marriage.30

For Isaac, the chain of events leading to his marriage to Rebekah (Gen 24) naturally precedes his time in Gerar where he and Rebekah mislead Abimelech about the nature of their relationship (Gen 26). For Jacob, on the other hand, though the wife-at-the-well type-scene precedes the inverted sister-wife type-scene, strictly speaking (Gen 29:1-12), its ramifications are concomitant with Laban's deceptive ploy at the wedding (Gen 29:15-28).

As mentioned in the introduction above, Gen 29-31 comports better with the sister-wife type-scene when inverted elements are in view, nevertheless, some of these very details come partially from the wife-at-the-well type-scene and some from the sister-wife story. In any case, it may be ceded there is a common preface to the sister-wife story of Isaac and Jacob;31 of course, Genesis does not record a betrothal story related to Abram.

Though it is only the Isaac and Jacob instances which feature the wife-at-the-well type-scene as a preface to the sister-wife type-scene, the postface episode is common to all four stories. It will be Isaac and Jacob, again, who experience corresponding outcomes from the sister-wife episodes. As a result, the Jacob cycle equivalent story shares the most similarity with Gen 26*, the sister-wife story most dissimilar to the classical three.

2 Postface

The sister-wife stories of Gen 12*, 20 and 26* typically conclude with the patriarch's wife being returned and they publicly depart from the local chieftain with material wealth (save the case of Isaac). Since Jacob works for his wealth (Gen 30:25-43; 31:36-42) and departs with his wives, children and flocks stealthily,32 sometimes, the connection is not made between the Jacob cycle and the sister-wife type-scenes.33 This nexus is buttressed and thereby substantiated by the repercussive postface in each case-namely, a covenant-making episode. Actually, issues of wealth, departure and covenant are often inextricably linked in these stories, therefore, each motif will be outlined.

Jacob's wealth accumulation is most similar to that of Isaac's in that both remain in their benefactor's orbit and there prosper at the hand of Yahweh (Gen 26:12-14 // Gen 30:30). Whereas Isaac is positioned three wells away from the presence of Abimelech where he grows prosperous (Gen 26:17-22), Jacob is stationed at a three-days-journey from Laban (Gen 30:36) where he prospers greatly. Furthermore, Isaac and Jacob's relations with the local chieftain and his people become strained. Just as Isaac experienced jealousy from the Philistines (Gen 26:14) and contentions from the herdsmen of Gerar (Gen 26:20, 21), so do Laban's sons grumble against Jacob and Laban treats Jacob antagonistically (Gen 31:1-2).34 Thus, it is the amassment of wealth together with the animosity of the local people that catalyses the patriarch's severance.

A few more inverted details are found in the context of Jacob's departure. First, to reiterate, the departure is a clandestine extraction precipitated by a covert conference with his wives (Gen 31:20-21) versus a public sending-away.35Second, whereas the chieftain typically transfers wife and wealth to the patriarch, Laban contends with Jacob over Leah and Rachel and the children as well as the numerous "oxen, donkeys, flocks, male and female servants" (Gen 32:5 NRSV; cf. Gen 31:17-18),36 on which both lay claims of ownership.37

Covenant making often features in the context of the sister-wife type-scenes to reinforce the subsequent separation of the patriarch and the potentate.38Subsequent to receiving Sarai back from Abimelech, Abram settled elsewhere within Philistia and dug a well. When the well was seized by one of Abimelech's servants, Abram seeks autonomy by making a covenant (ברִׂית; Gen 21:27, 32) with Abimelech; and he does so along with swearing oaths (שָבַע; Gen 21: 23, 24, 31) and having seven ewe-lambs serve as witness (עֵדָה; Gen 21:30). After Isaac had dug his third well, Abimelech sought him out to make a peace treaty, a covenant (ברִׂית; Gen 26:28); they do so, in addition to exchanging oaths (שָבַע; Gen 26:31). Similarly, the termination of Jacob and Laban's co-residence involves a covenant (ברִׂית; Gen 31:44); this agreement also includes swearing oaths (שָבַע; Gen 31:53) and erecting a witness (]עד; Gen 31:44, 48, 50, 52 [52]), though this time in the form of a stone-heap and pillar.39 As a result, the separation allows the respective patriarch and matriarch to return to the Promised Land.40

3 Framed Textual Unit

With the Jacob cycle sister-wife textual unit firmly marked, the resonant sister-wife motifs therein (as enumerated above) do, in fact, contribute to an inverted type-scene. It is only those themes within the Jacob cycle sister-wife textual unit that accord with the divine promises to the Hebrew ancestors which do not contribute, strictly speaking, to the sister-wife type-scene-namely, descendants and blessings.41 Indeed, taking possession of the land of Canaan is not realised until the end of the Hexateuch. Concerning descendants, whereas in Gen 12*, 20 and 26* the Hebrew ancestors are childless during the sister-wife episodes,42 the expanded and inverted Jacob cycle sister-wife story is unique in the procreation of several progeny. The issue of blessings may overlay the themes of the divine promise and a motif in the sister-wife stories; specifically, material wealth is one sign of blessing, though there are other expressions of blessing (such as favour in the sight of peoples and nations). Moreover, whether it is Jacob, Isaac, or Abraham, it is ironic that each patriarch-in the context of a sister-wife story- creates his own covenants with another human in order to secure land, descendants and blessings when Yahweh had already promised these (Gen 12:13) and effectively crystallised that tripartite promise in covenantal form (Gen 15 and 17).43

C WHY INVERSION?

If a sister-wife story in the Jacob cycle is feasible, the question arises: Why was it crafted as "a deliberate inversion of the wife-sister pattern"?44 I suggest the answer lies in the person of Jacob. Jacob is a deceptive, overturning character and this is foregrounded at key points throughout his life. Jacob (יַעֲקֹּב) supplanted his brother in the womb (עקב: Hos 12:4 [MT]; cf. Gen 25:26) and the oracle preceding their birth indicates that-contra to custom- "the elder shall serve the younger" (Gen 25:23 NRSV). This upturning plays out in Jacob sequestering the birthright (Gen 25:29-34) and supplanting Esau at their father's deathbed (עקב: Gen 27:36) by securing the family blessing.45 Yet, Jacob meets his match in deception and supplantation in his uncle and father-in-law Laban;46as a result, the series of events throughout the Jacob cycle are marked by duplicity and upheaval. Furthermore, even God interacts as a trickster in the events of the Jacob cycle, as John Anderson has argued.47 Therefore, it seems appropriate for the author(s)/redactor(s) of Gen 12-36 to supplant a sister-wife type-scene whereby the "'given set of repeated elements or details'" are inverted.48

D CONCLUSION

In this essay, I have sought to validate and substantiate the hypothesis of an inverted sister-wife type-scene in the Jacob cycle by methodologically setting parameters around the equivalent textual unit and registering additional observations of inverted narratival elements. With the wife-at-the-well type-scene serving as a preface to the Jacob cycle sister-wife story and the covenant-making ceremony serving as a postface to it, analogous motifs within the Jacob cycle do find commonality with those sister-wife stories of Gen 12*, 20 and 26*. Furthermore, the version of the sister-wife story within Gen 29-31 resembles an inverted type-scene in many ways. The purpose for inverting the standard sister-wife type-scene in the Jacob cycle lies in the deceptive, supplanting and overturning nature of the figure of Jacob (and Laban). Such literary creativity departs from convention, whereas the sister-wife type-scene in Gen 29-31 remains detectable.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, T. Desmond. "Are the Wife/Sister Incidents of Genesis Literary Compositional Variants?" Vetus Testamentum 42 (1992): 145-153. [ Links ]

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books, 2011. [ Links ]

Anderson, John E. "Jacob, Laban, and a Divine Trickster? The Covenantal Framework of God's Deception in the Theology of the Jacob Cycle." Perspectives in Religious Studies 36 (2009): 3-23. [ Links ]

__________________. Jacob and the Divine Trickster: A Theology of Deception and YHWH's Fidelity to the Ancestral Promise in the Jacob Cycle. Siphrut 5. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2011. [ Links ]

Blum, Erhard. "The Jacob Tradition. " Pages 181 -211 in The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation. Edited by Craig A. Evans, Joel N. Lohr and David L. Petersen. Vetus Testamentum Supplements 152. Leiden: Brill, 2012. [ Links ]

Brin, Ruth F. "Abraham as Diplomat: Reconsidering the Wife-Sister Motif." The Reconstructionist 50 (1984): 33-34. [ Links ]

Brodie, Thomas L. Genesis as Dialogue: A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, Samuel R. Driver and Charles A. Briggs [BDB]. Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, with an Appendix Containing the Biblical Aramaic. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2006. [ Links ]

Brown Jones, Christine. "Complicated Sisterhood: A Generous Reading of Leah and Rachel's Story." Review and Expositor 115 (2018): 565-571. [ Links ]

Clines, David J.A. The Theme of the Pentateuch. 2nd ed. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 10. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Culley, Robert C. Studies in the Structure of Hebrew Narrative. Missoula: Scholars Press, 1976. [ Links ]

De Hoop, Raymond. "The Use of the Past to Address the Present: The Wife-Sister Incidents (Gen 12:10-20; 20:1-18; 26:1-16)." Pages 359-369 in Studies in the Book of Genesis: Literature, Redaction and History. Edited by André Wénin. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 155. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Gordon, Cyrus H. "The Story of Jacob and Laban in the Light of the Nuzi Tablets." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 66 (1937): 25-27. [ Links ]

Greengus, Samuel. "Sisterhood Adoption at Nuzi and the 'Wife-Sister' in Genesis." Hebrew Union College Annual 46 (1975): 5-31. [ Links ]

Hedner-Zetterholm, Karin. "The Attempted Murder by Laban the Aramean: An Example of Intertextual Reading in Midrash." Nordisk Judaistik 24 (2003): 95108. [ Links ]

Hepner, Gershon. "Jacob's Servitude with Laban Reflects Conflicts between Biblical Codes." Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 115 (2003): 185-209. [ Links ]

Hoffmeier, James K. "The Wives' Tales of Genesis 12, 20 & 26 and the Covenants at Beer-Sheba." Tyndale Bulletin 43 (1992): 81-99. [ Links ]

Jensen, Aaron Michael. "The Appearance of Leah." Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018): 514-518. [ Links ]

Jonker, Louis C. Exclusivity and Variety: Perspectives on Multidimensional Exegesis. CBET 19. Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1996. [ Links ]

Kang, Hwagu. Reading the Wife/Sister Narratives in Genesis: A Textlingustic and Type-Scene Analysis. Eugene: Pickwick, 2018. [ Links ]

Kelsey, Marian. "Jacob and the Wife-Sister Stories." Jewish Bible Quarterly 46 (2018): 226-230. [ Links ]

Kennedy, Elisabeth Robertson. Seeking a Homeland: Sojourn and Ethnic Identity in the Ancestral Narratives of Genesis. BIS 106. Leiden: Brill, 2011. [ Links ]

Koch, Klaus. The Growth of the Biblical Tradition: The Form-critical Method. Translated by S.M. Cupitt. New York: Scribner's Sons, 1969. [ Links ]

Mabee, Charles. "Jacob and Laban: The Structure of Judicial Proceedings (Genesis 31:25-42)." Vetus Testamentum 30 (1980): 192-20. [ Links ]

Matthews, Victor Harold and Frances Mims, "Jacob the Trickster and Heir of the Covenant: A Literary Interpretation." Perspectives in Religious Studies 12 (1985): 185-195. [ Links ]

Moberly, R.W.L. The Theology of the Book of Genesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Noegel, S.B. "Sex, Sticks and the Trickster in Gen 30:31-43." Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 25 (1997): 7-17. [ Links ]

Oden, Robert A. "Jacob as Father, Husband, and Nephew: Kinship Studies and the Patriarchal Narratives." Journal of Biblical Literature 102 (1983): 189-205. [ Links ]

Pappas, Harry S. "Deception as Patriarchal Self-Defense in a Foreign Land: A Form Critical Study of the Wife-Sister Stories in Genesis." Greek Orthodox Theological Review 29 (1984): 35-50. [ Links ]

Patterson, Richard D. "The Old Testament Use of an Archetype: The Trickster." Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 42 (1999): 385-394. [ Links ]

Petersen, David L. "A Thrice-told Tale: Genre, Theme, and Motif. " Biblical Research 18 (1973): 30-43. [ Links ]

Pickering, Jordan. "Genesis 29:15-30 as Jacob's Wife-Sister Story." Paper presented at IOSOT, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 6 September 2016. [ Links ]

__________________. Sarah and Circumcision: The Place of Women in the Covenant according to the Genesis Narratives. PhD diss., Stellenbosch University, 2020. https://scholar.sun.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10019.1/108049/pickering_sarah_2020.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [ Links ]

Pollak, Aharon. "Laban and Jacob." Jewish Bible Quarterly 29 (2001): 60-62. [ Links ]

Polzin, Robert. "'The Ancestress of Israel in Danger' in Danger." Semeia 3 (1975): 8198. [ Links ]

Robinson, Robert B. "Wife and Sister through the Ages: Textual Determinacy and the History of Interpretation." Semeia 62 (1993): 103-128. [ Links ]

Ronning, John. "The Naming of Isaac: The Role of the Wife/Sister Episodes in the Redaction of Genesis." Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991): 1-27. [ Links ]

Ross-Burstall, Joan. "Leah and Rachel: A Tale of Two Sisters." Word and World 14 (1994): 162-170. [ Links ]

Sarna, Nahum M. Understanding Genesis. MRCS 1. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1966. [ Links ]

Seelenfreund, Morton H. and Stanley Schneider. "Leah's Eyes." Jewish Bible Quarterly 25 (1997): 18-22. [ Links ]

Ska, Jean-Louis. "Our Fathers Have Told Us": Introduction to the Analysis of Hebrew Narratives. Sources Bibliques 13. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1990. [ Links ]

Tucker, Gene M. Form Criticism of the Old Testament. Edited by J. Coert Rylaarsdam. GBS. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971. [ Links ]

Van Seters, John. "Jacob's Marriages and Ancient Near East Customs: A Reexamination." Harvard Theological Review 62 (1969): 377-395. [ Links ]

__________________. Abraham in History and Tradition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975. [ Links ]

Vrolijk, Paul. Jacob's Wealth: An Examination into the Nature and Role of Material Possessions in the Jacob-Cycle (Gen 25:19-35:29). Vetus Testamentum Supplements 146. Leiden: Brill, 2011. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Genesis 1-11. Translated by John J. Scullion. CC 1. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994. [ Links ]

Williams, James G. "The Beautiful and the Barren: Conventions in Biblical Type-Scenes." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 5 (1980): 107-119. [ Links ]

Submitted: 23/05/2021

Peer-reviewed: 28/10/2021

Accepted: 16/11/2021

Rev Dr Joshua Joel Spoelstra, Research Fellow at the Department of Old and New Testament, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa. Email: josh.spoelstra@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5702-1046.

1 Robert C. Culley, Studies in the Structure of Hebrew Narrative (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1976), 33-41; John Van Seters, Abraham in History and Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975), 75-76; Robert Polzin, "'The Ancestress of Israel in Danger' in Danger," Semeia 3 (1975): 81-98; T. Desmond Alexander, "Are the Wife/Sister Incidents of Genesis Literary Compositional Variants?," VT 42 (1992): 145-153; Klaus Koch, The Growth of the Biblical Tradition: The Form-Critical Method (trans. S.M. Cupitt; New York: Scribner's Sons, 1969), 111-132; James K. Hoffmeier, "The Wives' Tales of Genesis 12, 20 & 26 and the Covenants at Beer-Sheba," TynBul 43 (1992): 81-99; Harry S. Pappas, "Deception as Patriarchal Self-Defense in a Foreign Land: A Form Critical Study of the Wife-Sister Stories in Genesis," GOTR 29 (1984): 35-50; James G. Williams, "The Beautiful and the Barren: Conventions in Biblical Type-Scenes," JSOT 5 (1980): 107-119; David L. Petersen, "A Thrice-told Tale: Genre, Theme, and Motif," BR 18 (1973): 30-43; Raymond de Hoop, "The Use of the Past to Address the Present: The Wife-Sister Incidents (Gen 12:10-20; 20:1-18; 26:1-16)," in Studies in the Book of Genesis: Literature, Redaction and History (ed. André Wénin; Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2001), 359-369; Hwagu Kang, Reading the Wife/Sister Narratives in Genesis: A Textlingustic and Type-Scene Analysis (Eugene: Pickwick, 2018). Cf. John Ronning, "The Naming of Isaac: The Role of the Wife/Sister Episodes in the Redaction of Genesis," WTJ 53 (1991): 127; Ruth F. Brin, "Abraham as Diplomat: Reconsidering the Wife-Sister Motif," The Reconstructionist 50 (1984): 33-34; Samuel Greengus, "Sisterhood Adoption at Nuzi and the 'Wife-Sister' in Genesis," HUCA 46 (1975): 5-31; Robert B. Robinson, "Wife and Sister through the Ages: Textual Determinacy and the History of Interpretation," Semeia 62 (1993): 103-128.

2 Culley, Studies, 33-34. I cite Culley here as representative of scholarship on this subject.

3 Jordan Pickering, "Genesis 29:15-30 as Jacob's Wife-Sister Story," Presented at IOSOT, 4-9 September (Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2016); idem, Sarah and Circumcision: The Place of Women in the Covenant according to the Genesis Narratives (PhD diss.: Stellenbosch University, 2020), 156-157; Marian Kelsey, "Jacob and the Wife-Sister Stories," JBQ 46 (2018): 226-230. Cf. John E. Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster: A Theology of Deception and YHWH's Fidelity to the Ancestral Promise in the Jacob Cycle (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2011), 41, 188; Elisabeth Robertson Kennedy, Seeking a Homeland: Sojourn and Ethnic Identity in the Ancestral Narratives of Genesis (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 235-236.

4 Erhard Blum, "The Jacob Tradition," in The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation (ed. Craig A. Evans, Joel N. Lohr and David L. Petersen; Leiden: Brill, 2012), 181 -211.

5 An asterisk (*) by a biblical chapter citation indicates part of a chapter, that is, not all the verses which comprise it.

6 Laban possibly functions as the equivalent of a local chieftain in the biblical text by virtue of him being Laban the Aramean (Gen 25:20; 28:5; 31:20, 24; cf. Deut 26:5), which establishes him in a place and people group (cf. Gen 24:10) as well as imbued with some degree of influence (cf. Gen 29:4-6).

7 Pickering, Sarah and Circumcision, 157, calls this interrogative "the Edenic formula" because the first instance of it is God's confrontation in Gen 3:13.

8 Kelsey "Jacob and the Wife-Sister Stories," 226, states: "The appearance of the same question in this story leads one to wonder whether there are other similarities between Jacob's tale and the wife-sister stories of his forebears Isaac and Abraham. There are indeed parallels between the stories, and they are extensive enough to suggest that Jacob's experience with his two wives is a deliberate inversion of the wife-sister pattern."

9 Furthermore, I should add, there is symmetry between Jacob's and Abraham's sister-wife incidents in that a string of three perplexed questions is posed. Pharaoh and Abimelech demand an explanation from Abraham through a threefold series of questions (Gen 12:18-19a || Gen 20:9-10). Likewise, Jacob asks: "'What is my offense? What is my sin, that you have hotly pursued me? Although you have felt about through all my goods, what have you found of all your household goods?'" (Gen 31:36b-37a NRSV). Inversion in the Jacob cycle is again displayed, in as much as the patriarch turns the threefold questioning onto the local ruler.

10 Observations are from Kelsey, "Jacob and the Wife-Sister Stories," 226-227; Pickering, Sarah and Circumcision, 156; and my own. Cf. De Hoop, "The Wife-Sister Incidents," 368.

11 Additionally, the enigmatic expression ועֵינֵי לֵאָה רַכּוֹת (Gen 29:17a) seems to indicate that she is not beautiful to Jacob. Thus, Aaron Michael Jensen, "The Appearance of Leah," VT 68 (2018): 514-518; cf. also Morton H. Seelenfreund and Stanley Schneider, "Leah's Eyes," JBQ 25 (1997): 18-22.

12 Nahum M. Sarna, Understanding Genesis (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1966), 184, parallels Laban using the darkness of night to substitute Leah for Rachel with Jacob substituting himself for Esau in Isaac's darkened vision.

13 Concerning the divine confrontation in a dream, which is a standard element, there is also a case of inversion in Gen 31. Prior to Laban's dream-encounter with Yahweh, the narrative implies that Laban was going to harm Jacob (רָדָ: Gen 31:23; cf. BDB, 922-923); yet, after God intervenes in his dream, Laban proceeds cautiously (Gen 31:29a). Once in negotiations with Jacob, Laban claims to have been enlightened via divination that he himself is prosperous largely because of Yahweh's favour (Gen 30:27). This element is an inversion of Gen 20; for, in Abimelech's case, he is ignorant until the dream-state in which he is divinely confronted and after which he dispenses of wealth as recompense.

14 "Ultimately, the inversion of the sister-wife stories continues the ties between Jacob's life and the lives of Abraham and Isaac." Kelsey, "Jacob and the Wife-Sister Stories," 229.

15 At times, both Gen 12-36 and Gen 12-50 are referred to as Patriarchal History (I prefer the gender-neutral term Ancestral History), though at other times only Gen 1236 is so considered and Gen 37-50 is termed the Joseph Novella.

16 Cf. also David J.A. Clines, The Theme of the Pentateuch (2nd ed.; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 95-96; R.W.L. Moberly, The Theology of the Book of Genesis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 141-161; Ronning, "The Naming of Isaac," 1-27; Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster, 172.

17 Kang, Wife/Sister Narratives, 169, 174. Cf. Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster, 127-129.

18 Cf. Louis C. Jonker, Exclusivity and Variety: Perspectives on Multidimensional Exegesis (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1996).

19 Culley, Studies, 23.

20 Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 62.

21 This is the verbiage of Williams, "The Beautiful and the Barren," 111.

22 Alter, Biblical Narrative, 63-69.

23 Koch, Growth of the Biblical Tradition, 126.

24 See Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11 (trans. John J. Scullion; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994), 161, for a synopsis of scholars who advance the oldest sister-wife story of the three.

25 It is generally understood that these are complimentary methods, synchronic and diachronic respectively.

26 "The first task in any form-critical investigation is to define the exact extent of the literary unit"; Koch, Growth of the Biblical Tradition, 115. Cf. Gene M. Tucker, Form Criticism of the Old Testament (ed. J. Coert Rylaarsdam; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971), 13.

27 Culley, Studies, 33-68, quantifies type-scenes as comprising three or even two instances of similar narrative attestations.

28 To be precise, Kelsey proffers the nomenclature inversion yet does not speak of type-scenes (only stories), whereas Pickering utilises the term type-scene though not the verbiage inversion/inverted. I have melded these together.

29 For definitions on theme and motif, see Petersen, "Thrice-told Tale," 35-36; cf. Alter, Biblical Narrative, 77-78.

30 For the wife-at-the-well type-scene, see Culley, Studies, 41-43; Alter, Biblical Narrative, 62-68; Williams, "The Beautiful and the Barren," 113-115; Ronning, "The Naming of Isaac," 23; Jean-Louis Ska, "Our Fathers Have Told Us": Introduction to the Analysis of Hebrew Narratives (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1990), 36-37.

31 Granted, Gen 25 intervenes Isaac's wife-at-the-well type-scene in Gen 24 and his sister-wife type-scene in Gen 26, Gen 25 relates the familial lineage of Abraham, Ishmael and Esau.

32 See Aharon Pollak, "Laban and Jacob," JBQ 29 (2001): 60-62.

33 Cf. Pappas, "Patriarchal Self-Defense," 48. Contra, Paul Vrolijk, Jacob's Wealth: An Examination into the Nature and Role of Material Possessions in the Jacob-Cycle (Gen 25:19-35:29) (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

34 Pickering, Sarah and Circumcision, 156.

35 Cf. Christine Brown Jones, "Complicated Sisterhood: A Generous Reading of Leah and Rachel's Story," RevExp 115 (2018): 565-571; Joan RossBurstall, "Leah and Rachel: A Tale of Two Sisters," Word and World 14 (1994): 162170.

36 See Thomas L. Brodie, Genesis as Dialogue: A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 316, for his wealth diptych of "Jacob's Children and Flocks (29:31-30:24 // 30:25-43)."

37 Jacob feared Laban would take Rachel and Leah by force (גָזַל; Gen 31:31); this verb is used elsewhere in Genesis only "[w]hen Abraham complained to Abimelech about a well of water that Abimelech's servants had seized [גָזַל]" (Gen 21:25 NRSV). See Cyrus H. Gordon, "The Story of Jacob and Laban in the Light of the Nuzi Tablets," BASOR 66 (1937): 25-27; cf. also John Van Seters, "Jacob's Marriages and Ancient Near East Customs: A Reexamination," HTR 62 (1969): 389-390.

38 Hoffmeier, "The Wives' Tales," 95-96.

39 It is also said that the covenant itself (Gen 31:44) and God (Gen 31:50) serve as witness.

40 The covenant between Jacob and Laban marks the end of the kin marriage arrangements, as the Israelites are now a people distinct from the Arameans, that is, the kin of Abraham; cf. Robert A. Oden, "Jacob as Father, Husband, and Nephew: Kinship Studies and the Patriarchal Narratives," JBL 102 (1983): 189-205.

41 Cf. Polzin, "'The Ancestress of Israel in Danger' in Danger," 91-97.

42 The barrenness of the matriarch (or sterility of the patriarch?) is a motif applicable to Sarai, Rebekah and Rachel (Gen 11:30; 25:21; 29:31b)-yet it is inverted with the loved-less wife Leah (Gen 29:31a). See again Williams, "The Beautiful and the Barren," 107-119.

43 The proposals about covenants in the sister-wife type-scenes range from tracing the rightful heir of the Abrahamic promises to judicial proceedings related to familial sovereignty as well as formalities in diplomatic marriages amongst people groups. See respectively Victor Harold Matthews and Frances Mims, "Jacob the Trickster and Heir of the Covenant: A Literary Interpretation," PRSt 12 (1985): 185-195; Charles Mabee, "Jacob and Laban: The Structure of Judicial Proceedings (Genesis 31:25-42)," VT 30 (1980): 192-207; Hoffmeier, "The Wives' Tales," 81-99.

44 Kelsey, "Jacob and the Wife-Sister Stories," 226. Kelsey gives her own answers to the question.

45 See Richard D. Patterson, "The Old Testament Use of an Archetype: The Trickster," JETS 42 (1999): 389-392; cf. also S.B. Noegel, "Sex, Sticks and the Trickster in Gen 30:31-43," JANES 25 (1997): 7-17.

46 Karin Hedner-Zetterholm, "The Attempted Murder by Laban the Aramean: An Example of Intertextual Reading in Midrash," Nordisk Judaistik 24 (2003): 102; cf. Gershon Hepner, "Jacob's Servitude with Laban Reflects Conflicts between Biblical Codes," ZAW 115 (2003): 185-209 (197, 201).

47 Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster; idem, "Jacob, Laban, and a Divine Trickster? The Covenantal Framework of God's Deception in the Theology of the Jacob Cycle," PRS 36 (2009): 3-23.

48 Culley, Studies, 23. From an alternate synchronic perspective, the toledot of Terah (Gen 11:27-25:11) has two sister-wife type-scenes (chs. 12* and 20) and-with the inclusion of the Jacob cycle inverted equivalent-the toledot of Isaac (Gen 25:1935:29) also has two (chs. 26* and 29-31); cf. Kang, Wife/Sister Narratives, 39-61.