Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 no.2 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n2a19

Psalms 135 and 136: Exodus Motifs Contributing to Israelite Praise

Dirk Human

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

The twin psalms 135 and 136 are both hymnic inspired texts with strong cultic features. In both psalms, exodus allusions and motifs play a role in the composers' intention to build their own theological thrust. Both psalms display a plethora of resemblances regarding atmosphere, structure, themes, motifs, content and liturgical importance. Nonetheless, each of them radiates its own identity and theological intent. By reading these two psalms both separately and together, the common denominator places the focus on praise for the Israelite God, Yahweh. By identifying the exodus motifs and determining their function in each psalm, this article aims to contribute to the theological meaning of both psalms.

Keywords: Ps 135, Ps 136, Exodus motifs, Twin psalms, African Contextual Hermeneutics

A INTRODUCTION

This article is a tribute to David Tuesday Adamo, who visited South Africa for the first time with a Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) grant as a Research Fellow of the University of Pretoria. Adamo has published extensively in South African journals and contributed to a wide range of themes of the Old Testament, but especially to Psalms research in Africa from the perspective of African Contextual Hermeneutics. As a son of the African soil, Adamo's academic work has added great value to the contextualisation and contemplation of the Hebrew Bible in Africa. His approach and exegetical point of departure is unique to his person and to the intention to show African Biblical hermeneutics' uniqueness in the context of global theologies.

Adamo has contributed to the emergence of African Theologies with a strong emphasis on the concept of 'decolonisation' or liberation from the co-called western theologies. For him, African Old Testament scholars should be deeply rooted in their own African context, which is often characterised by marginalisation, poverty, suppression, political instability, conflict and a lack of sources among others. In my view, Adamo is, therefore, a strong Old Testament voice as he sketches the African landscape with a picturesque kaleidoscope of African colours. Every book and article written by him is embedded in a variety of challenges and contexts of Africa, often more specifically the (Yoruba) Nigerian contexts.

Adamo's love for the book of Psalms is evident. Recent publications on Psalms 23 and 90 in the journal Verbum et Ecclesia illustrate this academic love.1Earlier, Adamo also published on Psalms 35, 91, 109 and 'the poor' in the Psalms.2 With these publications he vividly sketches God's love and care and protection and deliverance of the African people and their needs through the lens of the Psalter. In dedicating some perspectives on Exodus motifs in Psalm 135 and 136 to David Tuesday Adamo, this article is a recognition of the important theme of deliverance or liberation of God's people in some of Adamo's works.

Once described as "partners in praise,"3 Pss 135 and 136 display a plethora of resemblances regarding atmosphere, structure, themes, motifs, content and liturgical importance. Nonetheless, each of them radiates its own identity and theological intent. By reading these two psalms, both separately and together, the common denominator places the focus on praise for the Israelite God Yahweh because of the deity's activities in creation and history. Both psalms pitch the status and position of this deity against other gods and emphasise Yahweh's intervention in Israelite history.

Exodus motifs, amongst others, contribute to descriptions of Yahweh's mighty deeds in his people Israel's Heilsgeschichte, thus, enhancing his power or reputation on the universal playground of 'potential' deities and redeemers. The outcome of Yahweh's fame, though, is in both Pss 135 and 136, no surprise!

B 'TWIN' PSALMS STRATEGICALLY PLACED

Psalms 135 and 136 are known as 'twin' psalms (Zwillingspsalmen).4Several themes are reciprocally present in both texts,5 which include the descriptions of Yahweh's 'goodness,' relation with other gods, wondrous deeds in 'creation,' intervention at the 'exodus,' wandering through the 'wilderness,' conquest of the 'land' and God's provision or care for Israel and creation. The tradition-historical bond between these two psalms seems to be indisputable.

Interconnectedness also exists between Pss 135-136 and the Egyptian Hallel (Pss [111-112]113-118) on the one side and the Songs of Ascents (Pss 120-134) on the other, with close affinity between Pss 135 and 115, and Ps 136 with Ps 118.6 This creates the assumption that the psalm groups, Pss 111-118 and 135-136, form an inclusio around the Torah Ps 119 and Songs of Ascents (Pss 120-134), by providing a hymnic framework. Psalm 137 forms a 'bridge' between these twin psalms and the fifth David-Psalter (Pss 138-145).

The connection between Ps 135, as first part of the 'twin' psalms, with Ps 136 and the relationship of Pss 135-136 with both the Egyptian Hallel (Pss 113- 118) and Songs of Ascents (Pss 120-134) emphasise certain theological inclinations in Book V of the Psalter. The strategic position of Pss 135-136 in the Sitz in der Literatur of Book V shapes their theological profile, individually and as twin-pair.

With the final doxology (Pss 146-150), the Egyptian Hallel (Pss 113- 118), the hymnic twin psalms (Pss 111-112; 135-136) and numerous Hallelujah exclamations, Book V portrays a strong hymnic character.7The liturgical collections, Pss 113-118 and 120-134, bound by Ps 119 underscore how the central part of Book V is liturgically orientated towards the annual festivals, namely Pesah (Pss 113-118), Sabüot (Ps 119) and Sükkot (Pss 120-134). By means of an inclusio Book V (Pss 107-145) is framed by hymnic praise and wisdom perspectives (Pss 107:42-3; 145:19-21): Yahweh's universal reign and providence for all creation are hailed.8A challenge to all creation and creatures follows, namely, that the wise should react with insight to Yahweh and his deeds. Pss 135 and 136 provide such responses.

C PS 135 - PRAISE YAHWEH AS CREATOR AND REDEEMER

1 Introduction

Psalm 135 is a typical hymn or Hallel psalm.9 Its structure comprises an inclusio frame as summons to praise Yahweh, while the central part of the psalm provides the reasons or motivation why the deity should be praised.

The psalm can best be described as an anthological hymn10 since the text seems to be a mosaic composition of fragments, allusions, motifs and citations from other Old Testament texts. In particular, Pss 115, 134 and 136 might have captured the imagination of its composer(s) as Vorlage for the psalm11 although these are not the only texts alluded to in Ps 135. Older material was most probably utilised to create a new composition in order to blend "older voices to form a contemporary medley."12

The hymnic language and structure (Pss 135:1-3, 19-21), temple references (Ps 135:2), relations to the Egyptian Hallel (Pss 113-118) and Songs of Ascents (Pss 120-134) as well as reference to the houses of Aaron, Levi and the divine abode Zion/Jerusalem (Ps 135:19-21) make the cultic setting and liturgical use of the psalm in the Second Temple period a real possibility.13 Its use in a temple festival is not totally clear although suggestions of an autumn festival14 or the Passover15 are strong contenders. The latter seems more possible because of the psalm's strong relationship with the Egyptian Hallel (Pss 113118) and the description of Yahweh's redemptive acts at the Israelite exodus event (Ps 135:8-9).

A historical setting (Sitz-im-Leben) for dating Ps 135 can be allocated in a late period.16 Arguments point more specifically to a post-exilic period17 when God's people could have experienced difficult and suppressive circumstances (Ps 135:14; Deut 32:36) and when they were dominated by surrounding neighbours or world powers and their gods (Ps 135:15-18).18 During this period, they were struggling for survival and searching for their own identity as worship in the Second Temple period resumed.19 Temple personnel from this period are mentioned (Ps 135:19-20). As a late collage composition, applying the deuteronomistic Name-theology (Ps 135:1, 3, 13), influenced by Deutero-Isaiah,20 and with recognisable linguistic and grammatical features,21 the psalm is suspected to be younger than Ps 136 and the Songs of Ascents.22 A date in the fourth century BCE, suggested by Zenger, is thus possible.23

In a disturbed post-exilic time, the re-living and re-affirmation of the power of the sovereign and incomparable God, Yahweh, by his servants over and against the powerless gods of the nations and their adherents/makers would empower and encourage the Yahweh worshipping community. It would have been an emphatic encouragement of their faith, by expressing the powers of their God, Yahweh. The question then is how does Ps 135 contribute to this faith-experience?

2 Text outline

The hymnic text of Ps 135 forms a coherent structure with unproblematic demarcation. In a chiastic pattern, the structure is framed by an inclusio with a short call to praise Yah (Hallelujah, vv. 1a, 21b) and then with a more extended summons to praise Yahweh (vv. 1b-4, 19-21a). The central part of the psalm provides reasons why the deity should be praised.

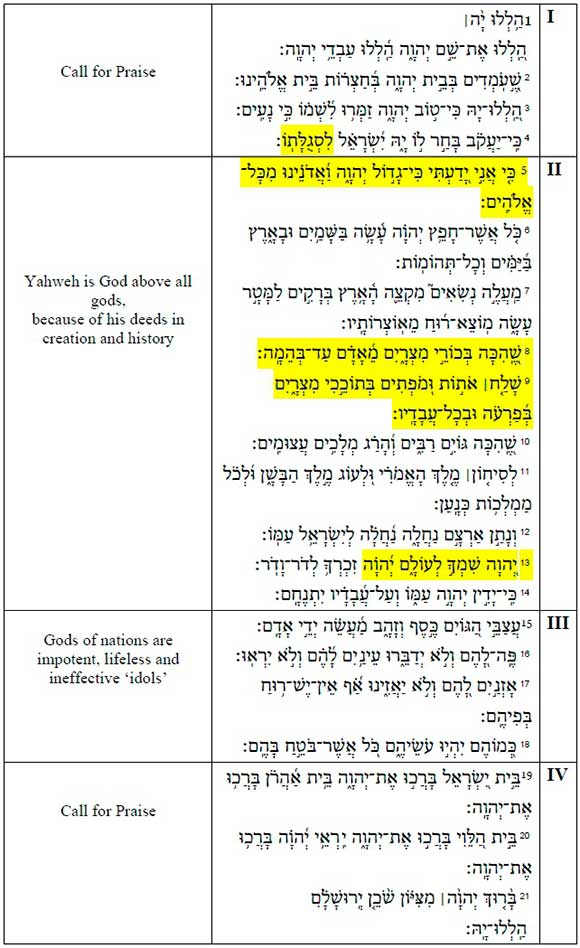

A suggested text outline looks as follows:

Translation

1 Praise the LORD. Praise the name of the LORD; praise him, you servants of the LORD,

2 you who minister in the house of the LORD, in the courts of the house of our God.

3 Praise the LORD, for the LORD is good; sing praise to his name, for that is pleasant.

4 For the LORD has chosen Jacob to be his own, Israel to be his treasured possession.

5 I know that the LORD is great, that our Lord is greater than all gods.

6 The LORD does whatever pleases him, in the heavens and on the earth, in the seas and all their depths.

7 He makes clouds rise from the ends of the earth; he sends lightning with the rain and brings out the wind from his storehouses.

8 He struck down the firstborn of Egypt, the firstborn of people and animals.

9 He sent his signs and wonders into your midst, Egypt, against Pharaoh and all his servants.

10 He struck down many nations and killed mighty kings-

11 Sihon king of the Amorites, of king of Bashan, and all the kings of Canaan-

12 and he gave their land as an inheritance, an inheritance to his people Israel.

13 Your name, LORD, endures forever, your renown, LORD, through all generations.

14 For the LORD will vindicate his people and have compassion on his servants.

15 The idols of the nations are silver and gold, made by human hands.

16 They have mouths, but cannot speak, eyes, but cannot see.

17 They have ears, but cannot hear, nor is there breath in their mouths.

18 Those who make them will be like them, and so will all who trust in them.

19 All you Israelites, praise the LORD; house of Aaron, praise the LORD;

20 house of Levi, praise the LORD; you who fear him, praise the LORD.

21 Praise be to the LORD from Zion, to him who dwells in Jerusalem. Praise the LORD. 1a Hallelujah

I 1b-4 Call to praise Yahweh

II 5-14 Yahweh's greatness and incomparability over all gods

5-7 Yahweh's greatness in creation

8-14 Yahweh's greatness in Israelite history

III 15-18 Gods of the nations are impotent, lifeless and ineffective 'idols'

IV 19-21 Call to praise Yahweh

21b Hallelujah

3 Theological inclination

This imperatival hymn is a call to hail the Israelite and universal God, Yahweh, as incomparable, great God over all other gods. The reason is that He is 'good' (v. 3) and He has chosen Israel as 'treasured possession' (v. 4). This goodness is confirmed in the power of his mighty deeds in creation and Israelite history to underscore the reputation of his sovereign greatness and incomparability. Yahweh reigns over creation and history.

• * (1a, 21b) - This Hallel psalm is framed by the Hallelujah call in an inclusio.

• I and IV (vv. 1b-4, 19-21) - The addressees in the 'calls for praise' seem to include exclusive Israelite (135:1b-4) and possibly inclusive worshippers (135:19-21). Initially, they are the 'servants' in the house and in the courts of Yahweh: Israel as Yahweh's treasured possession (vv. 1b-4); but ultimately they include both Israelites, the temple groups, Aaronites and Levitesas well as those who 'fear' (worship) Yahweh in Zion/Jerusalem.24 The latter might have included "proselytes and pilgrims of other nationalities or an inclusive description for all worshippers together."25

• Sections II and III form the central part of the psalm and contrasts the confession that Yahweh is a great God, greater than all the (other) gods (vv. 5-14)26 with the description that the gods of the nations are powerless idols (vv. 15-18).

• Section II (5-14) comprises two parts. In verses 5-1, the sovereignty of Yahweh ("Everything that pleases him, Yahweh does") is illustrated in what He does in creation-in heavens, on earth, in the seas and in all the depths.27 He is in control of the clouds, lightning, rain and wind. In verses 8-14, Yahweh's fame is highlighted by his interventions in Israelite history (or Heilsgeschichte)-his mighty deeds in Egypt (vv. 8-9), his defeat of hostile kings, Sihon and Og, in the Transjordan (vv. 10-11) and his gift of the land to his people as heritage (v. 12).

A short intersection of praise (vv. 13-14), which is linked to the opening call for praise (vv. 1b-4), seems to confirm the Yahweh-Israel relationship and this deity's everlasting reputation and supportive 'vindication and compassion' for his people.

• Section III (vv. 15-18) contrasts the greatness of Yahweh with the impotent and inefficient gods of the nations by characterising them as 'idols.' Although they are made of precious material, they are handmade, dumb, blind, deaf and lifeless (v.17: "and no wind -nn, - in their mouths").28 Their makers and those who trust in them will be like them (v. 18).

Not only Yahweh and the gods of the nations are polemically contrasted but also the worshippers of these deities. Israel is Yahweh's chosen 'treasured possession' (v. 4), while those who trust in the other gods (idols) are portrayed as powerless, impotent and lifeless like them. The underlying didactics of the text suggest the assumption, which deity can be trusted for creative or redemptive help? With Yahweh's reputation depicted as creator of the universe, redeemer in Israelite history and controller of the 'wind' (life, vv. 7, 17), the answer to the question is obvious. Only the Israelite God, Yahweh, can do this.

4 Exodus allusions and motifs

How do exodus allusions and motifs contribute to the understanding of the text and of its theological intent? Only a few allusions and motifs are present, which include the following:

4a Jacob/Israel - Yahweh's 'treasured possession' (לִסְגֻלָּתֽוֹ) - Exod 19:5

In verse 4, the special relationship between Yahweh and his people Jacob/Israel is described. This deity has chosen them as 'treasured possession.'29 The psalmist recalls this term, which was used in Yahweh's mouth to Moses at Mount Sinai, after God delivered the Israelites from Egypt (Exod 19:5). The description recalls a special bond between the deity and his people at the 'birthdate' of their covenant relationship. The allusion to God's selection of Jacob/Israel during or after the exodus events could be considered "Yahweh's most important act in history,"30 which confirms his faithfulness and covenant love for them. By using this term from history, the psalmist underscores this precious relationship between Israel and Yahweh 'from the beginning,' centred around the covenant.

4b Jethro's confession - Exod 18:11

Verse 5 similarly depicts Yahweh's incomparability to and greatness above all other gods. The verse alludes to the utterance of Jethro, Midianite father-in-law of Moses, when he heard that Yahweh has rescued Israel from the power of the Egyptians and of the Pharaoh. Jethro said, "Now I know that the LORD is greater than all other gods, for he did this to those who had treated Israel arrogantly" (Exod 18:11).

Jethro declared the greatness and supremacy of Yahweh as a non-Israelite,31without witnessing God's deeds; so did the psalmist, probably as Yahweh's worshipper. This allusion to the declaration of a non-Israelite (Exod 18:11) emphasises in a complementary way the universal and inclusive recognition of Yahweh's greatness and supremacy above all other gods by a non-Israelite. This allusion directs Ps 135 into inclusive praise.

4c Yahweh's mighty deeds as redeemer in Egypt - Exod 7:15

Verses 8-9 also illustrate Yahweh's greatness, incomparability and supremacy in relation to all other gods because of his mighty deeds in Egypt, while delivering Israel from the bondage of the Egyptians and their Pharaoh. A selection of these deeds in verses 8-9 include the destruction of the firstborns (v. 8) and the sending of 'signs and wonders' among the Egyptians (v. 9) against Pharaoh and his servants.

The notion of the firstborn in Ps 135 deserves attention. Where other psalms only mention the firstborn of humans,32 our psalm speaks of the destruction of the firstborn of humans and animals. This merism indicates God's total destruction of the Egyptians and expresses the magnitude of Yahweh's power. Verse 8 is reminiscent of Exod 12:12 and 12:29.33 The fact that this deed of destruction is mentioned first among the plagues-although the exodus narrative puts it last-stresses its importance and illustrates Yahweh's power over life and death. It might even portray a summative action of all the 'signs and wonders' of Yahweh in Egypt.

The term 'servants' ("against Pharaoh and against his servants") in verse 9 draws the attention to the 'servants' of Yahweh in verse 1. This immediately queries the difference between the ' servants' of Yahweh and those of the Pharaoh. While the former serve in the temple and are called upon to praise Yahweh with pleasure, the latter are plagued and struck with death. This contrastive depiction places emphasis on the outcome of the different 'servants' of the different deities. In his office, the Pharaoh was regarded as a god. The 'servants' of Yahweh will live in worship and praise, while the 'servants' of Pharaoh will experience destruction. This portrayal provides an example of Yahweh's supremacy over other gods.

4d "This is my Name for ever...." - Exod 3:15

In verse 13, Yahweh's durative reputation (Name) and remembrance of his past mighty deeds are linked to the psalm's opening call for praise (vv. 1b-3). In order "to magnify Yahweh's fearful reputation"34 for future generations, the psalmist echoes God's speech to Moses at the Burning Bush (Exod 3:15): "This is my Name forever, the Name you shall call me from generation to generation."

By alluding to the revelation of God's name at the Burning Bush, the psalmist takes the Israelite history back to the point of the self-revelation of Yahweh. This deity's fearful reputation in Israelite history started 'from the beginning,' when Moses was summoned to deliver Israel from Egypt and the Pharaoh. Yahweh's reputation (Name) was from its theological history already known right from the beginning of his people's sojourn in Egypt when they were in bondage under Pharaoh.

All the above exodus allusions and motifs contribute to the theological thrust of the Israelite God's supremacy and incomparability to all other deities. The exodus event has emphasised Yahweh's deliverance powers to urge people towards inclusive worship and praise in the disturbing post-exilic turbulent times.

D PS 136 - THANKSGIVING FOR YAHWEH'S STEADFAST LOVE

1 Introduction35

While Ps 135 is depicted as a Hallel psalm, Ps 136 is known as a Todah or Thanksgiving hymn.36 It mirrors a hymnic structure with summons for thanksgiving surrounded by an inclusio frame (Ps 136:1-3, 26). Motivation for this thanksgiving is evident inside this frame (Ps 136:4-25). The close relationship between these two twin psalms has been identified.

The most characteristic stylistic feature of Ps 136 is the twenty-six repetition of its monotonous refrain, "for his steadfast love endures forever,"37which most probably had a responsorial function in a liturgical ritual. With its litany (call and response) structure, antiphonal or reciprocal interaction between a liturgist and group (whether congregation or choir) was most probably enacted. Where the first part of every verse portrays Yahweh's characteristics or deeds, the second part holds the refrain. Apart from its close relationship with Ps 135, the psalm shows intertextual connections with Pss 113 and 115 (v. 23), 107 (v. 24) and 104 (v. 25). In redactional building blocks, Ps 136 forms the climax of the composition together with the Songs of Ascents (Pss 120-134 + 135-136); the composition of the group psalms, Pss 107-136 (via Ps 118:1, 29), with Hôdu inclusio and ultimately of the Zion Psalter, Pss 2-136.

The cultic setting38 of the psalm is clear from its liturgical composition.39Indications of cultic formulas include the presence of summons to thanksgiving (vv. 1-3) and the liturgical responsorium (vv. 1-26). Although a specific or single cultic Sitz-im-Leben, whether festival or worship service, evades an exact choice, there are some suggestions. This 'Great Hallel'40 was often associated with the Passover feast,41 due to the descriptions of Israel's deliverance from Egypt (vv. 10-15). Besides, the New Year festival in autumn is suggested,42when Yahweh's activities in creation and history were commemorated. Other proposals include the Feast of the Tabernacles,43 the harvest festival,44 or even the morning liturgy of the Sabbath.45 Nonetheless, it is not necessary to choose a fixed cultic Sitz, since the re-enactment of Ps 136 rehearses a re-living or reviving of Yahweh's deeds of the past-deeds of creating, redeeming, protecting, and providing. Therefore, more than one cultic celebration could have been possible.46

To fix a historical setting or date for the psalm also remains a challenge. Nonetheless, indications show that a relative dating of the final form of the psalm is possible. Traditio-historically, the content (vv. 4-22) presupposes knowledge of the complete Pentateuch.47 Furthermore, the expression 'God of heavens' (v. 26)48 is a known term from the Persian period. The relative particle sh (v. 23) probably is dated post-exilic.49 In addition, the situation of the congregation ("in our low estate,' vv. 23-25) in the contemporary application of the current exilic/post-exilic Israelite generation presupposes a late exilic or post-exilic context. Therefore, a dating at the end of the fifth, beginning of the fourth century, BCE is a possibility.50

2 Text outline

The hymnic Todah, Ps 136, exposes a simple coherent composition. With an inclusio framework it comprises the summons for thanksgiving (vv. 1 -3; 26), with motivation for the thanksgiving (v. 4-22) and a contemporary application (v. 23-25) within the framework. A responsorial refrain appears in the second part of each verse.

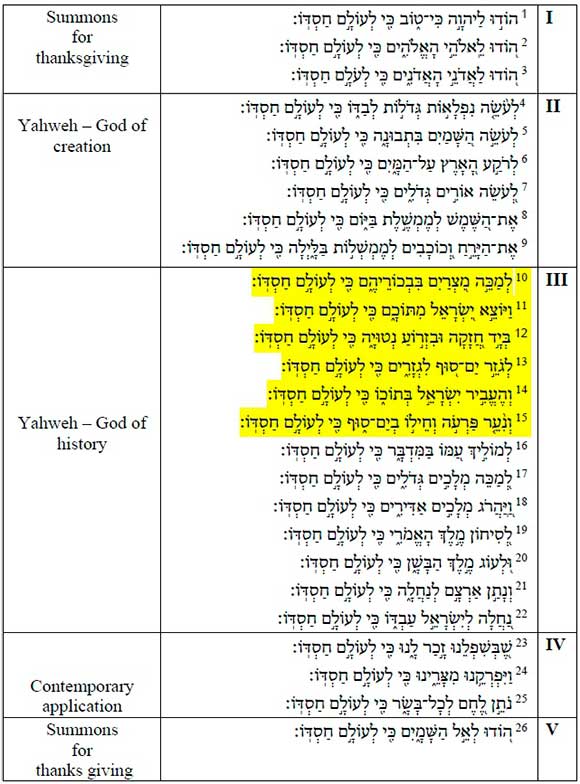

A possible outline of the text is as follows:

Translation

1 Give thanks to the LORD, for he is good: His love endures forever.

2 Give thanks to the God of gods: His love endures forever.

3 Give thanks to the Lord of lords: His love endures forever.

4 to him who alone does great wonders: His love endures forever.

5 who by his understanding made the heavens: His love endures forever.

6 who spread out the earth upon the waters: His love endures forever.

7 who made the great lights: His love endures forever.

8 the sun to govern the day: His love endures forever.

9 the moon and stars to govern the night: His love endures forever.

10 to him who struck down the firstborn of Egypt: His love endures forever.

11 and brought Israel out from among them: His love endures forever.

12 with a mighty hand and outstretched arm: His love endures forever.

13 to him who divided the Reed Sea asunder: His love endures forever.

14 and brought Israel through the midst of it: His love endures forever.

15 but swept Pharaoh and his army into the Reed Sea: His love endures forever.

16 to him who led his people through the wilderness: His love endures forever.

17 to him who struck down great kings: His love endures forever.

18 and killed mighty kings: His love endures forever.

19 Sihon king of the Amorites: His love endures forever.

20 and Og king of Bashan: His love endures forever.

21 and gave their land as an inheritance: His love endures forever.

22 an inheritance to his servant Israel: His love endures forever.

23 He remembered us in our low estate: His love endures forever.

24 and freed us from our enemies: His love endures forever.

25 He gives food to every creature: His love endures forever.

26 Give thanks to the God of heaven: His love endures forever.

I 1 -3 Summons for thanksgiving

II 4-9 Yahweh is God of creation

III 10-22 Yahweh is God of history

10-15 Yahweh delivers from Egypt at exodus

16-20 Yahweh guides in desert and protect against kings

21-22 Yahweh gives land

IV 23-25 Contemporary application: Yahweh sustains

V 26 Summons for thanksgiving

3 Theological inclination

Like Ps 135, this Todah Psalm summons addressees to bring thanksgiving to the Israelite and universal God, Yahweh, as God over all gods (vv. 2-3, 26). The reasons are because He is "good" (v. 3) and "his steadfast love endures forever" (vv. 1 -26). Every act of Yahweh in creation and Israelite history is witness to and expression of this 'goodness' and 'steadfast love' for his people.51 Yahweh is the only incomparable and supreme deity who reigns universally.

• I and V (vv. 1-3, 26) - The psalm's frame echoes several summons for Yahweh's thanksgiving because of his goodness and covenant love. As 'God of gods,' 'Lord of lords' and 'God of the heavens,' He is depicted in the psalm in subtle polytheistic polemics. The epithets immediately allude to his sole and supreme status as deity. What follows is the exposure of his power and the domains where this power is effectuated in order to express God's goodness and covenant love.

• II (vv. 4-9) - This section portrays Yahweh as God of creation. Yahweh's sole involvement in the 'great wonders' of these deeds include the creation of the heavens and earth, the great lights such as the sun and moonas well as the stars.

• III (vv. 10-22) - In section III, Yahweh is portrayed as God of history. In actions of Israel's deliverance from Egypt and from the Pharaoh (vv. 10-15) Yahweh redeemed his people at the exodus events. God guided and protected them in the desert against mighty kings (vv. 16-20). Ultimately, Yahweh gave his servant, Israel, the land as inheritance (vv. 21-22).

• IV (vv. 23-25) - In a contemporary application embedded in the text the psalmist draws the past into the present. Contextually, the psalm's content is appropriated in Ps 136 itself. For the 'current generation' in their 'low state,' the psalmist shows how Yahweh provides for and sustains them-God remembered them in their 'low state,' freed them from their adversaries and gave bread to all flesh.

With the rhythm of a heartbeat, every act of creation and salvation by Yahweh (and their later appropriation) in the collected experiences of Israel are endorsed by the refrain. Every divine action is a sign of God's goodness and steadfast love for his people and it is repeated twenty-six times. Thus, Yahweh's incomparability to and supreme divine ability over all other gods are affirmed.

4 Exodus allusions and motifs

4a Introduction

Although small in number, exodus allusions and motifs form primarily part of section III (vv. 10-15) where Yahweh is portrayed as God of Israelite history. These motifs contribute to the perspective that the Israelite God is redeemer from their Egyptian bondage. Egypt and the Pharaoh are Chiffres for suppression and life-endangerment. Amongst others, the exodus events and Egyptian deliverance form part of a series of 'great wonders' that Yahweh performed alone (v. 4). Verses 10-15 expose these motifs:

10 לְ מ כֵׁ֣ה מִַֽ֭צְ ריִם בִבְכוֹ ריהֶָ֑ם כִִּ֖י לְעוֹ לֵׁ֣ם חסְדָֽוֹ׃

11 ויוֹ צֵׁ֣א יִַֽ֭שְ ר אל מִתוֹ כָ֑ם כִִּ֖י לְעוֹ לֵׁ֣ם חסְדָֽוֹ׃

12 בְ יֵׁ֣ד חֲַֽ֭ ז קה וּבִזְרֵׁ֣וֹ ע נְטוּ יָ֑ה כִִּ֖י לְעוֹ לֵׁ֣ם חסְדָֽוֹ׃

13 לְ ג זֵׁ֣ר ים־סַֽ֭וּף לִגְ זרִָ֑ים כִִּ֖י לְעוֹ לֵׁ֣ם חסְדָֽוֹ׃

14 וְהֶעֱבִֵׁ֣יר יִשְ ר אֵׁ֣ל בְתוֹכָ֑וֹ כִִּ֖י לְעוֹ לֵׁ֣ם חסְדָֽוֹ׃

15 וְנִָּ֨ עִּ֤ר פ רעֵׁ֣ ה וְ חילֵׁ֣וֹ בְ ים־סָ֑וּף כִִּ֖י לְעוֹ לֵׁ֣ם חסְדָֽוֹ׃

10 to him who struck down the firstborn of Egypt: His love endures forever.

11 and brought Israel out from among them: His love endures forever.

12 with a mighty hand and outstretched arm: His love endures forever.

13 to him who divided the Reed Sea asunder: His love endures forever.

14 and brought Israel through the midst of it: His love endures forever.

15 but swept Pharaoh and his army into the Reed Sea: His love endures forever.

A traditio-historical survey shows that the psalm's composer was aware of Pentateuchal traditions and motifs from the book of Genesis, Exodus52 and Deuteronomy. Not only was the psalmist selective in the choice of exodus motifs but eclectic descriptions were applied to strengthen the composer(s) own theological thrust. In the psalm's context, these motifs add value to the notion that Yahweh is God of Israel's history. The following motifs are described.

4b Yahweh struck Egyptian firstborns and brought Israel out from among them with power (136:10-12)

In three consecutive verses, after Yahweh's activities in creation (vv. 4-9), He struck the Egyptians' firstborns (v. 10) and brought Israel out from among them (v. 11) with power - "with mighty hand and outstretched arm" (v. 12). The psalm shows awareness of the Exodus narrative in Exod 11 -12 and uses that text interpretatively without literary or structural dependency. Verse 10 focuses on the Egyptians, while the camera in verse 11 is on Israel. Both actions are constituted as Yahweh's work alone (v. 12).

A relationship between verses 9 and 10 becomes apparent in the word 'night.' God's power over the bodies that govern the 'night' (v. 9) is the same power which smote the firstborns in the "middle of the night" (Exod 12:29). Verse 10 echoes Exod 12:12 ("On that same night I will pass through Egypt and strike down every firstborn of both people and animals"), a text which is re-interpreted in various Old Testament texts.53 That the murder of firstborns is described as a deed of compassion or 'steadfast love' sounds absurd but in this psalm, it is meant to portray a powerful deed of God's covenant love for Israel.

That Israel is brought out 'from the midst' (v. 11) of the Egyptians without a hand on them emphasises the latter's helplessness and powerlessness.54 The phrase 'from their midst' also alludes to Deut 4:3455 where Yahweh's power is demonstrated as a god who is able to take a nation out of another nation "with a mighty hand outstretched arm." With this anthropomorphism, which echoes Exod 15:1256 and 7:5, Yahweh's sole action of power is depicted, without the help of the outstretched arms of Moses or Aaron (Exod 7:19; 9:22; 10:12).

4c Yahweh divided the Reed Sea, brought Israel through its midst and swept Pharaoh and his army into the Reed Sea (Ps 136:13-15)

In verses 13-15, the splitting of the Reed Sea and Yahweh's victory over Pharaoh and his army are depicted. The composer of the psalm created cohesion between these verses through an inclusio of the key term Yam Suf (Reed Sea) in both verses 13 and 15. Poetically encircled by the threats, with the people of Israel in the middle of the danger, Israel's safe journey is poetically pictured from "the midst of it" (v. 14). From there, God guided them safely through. With this picturesque depiction, Yahweh's power over the life-threatening danger posed by Pharaoh and his army, is stated.

All three verses allude to aspects in the narrative of Exod 14, which describes Israel's journey through the Reed Sea.57 The verb gzr ('cut into pieces') in verse 13 creates mythological allusions to the Ugaritic Drachenkampf and the Babylonian Enuma Elish epic,58 which certainly leaves room for reflection on the 'contest' between Yahweh and Pharaoh (seen as a deity).59 In Ps 136, there

is a speechless victory for the Israelite deity over life-threatening Egyptians without any struggle. Yahweh's power over the life-threatening power of Pharaoh therefore remains indisputable.

As in Ps 135, the allusions and motifs of the exodus events in Ps 136 contribute to the theological intent of the text. Yahweh is sketched as a delivering God who overpowers all-encompassing life-threatening powers, Pharaoh and his army. As part of their cultic (vv. 1 -26) and everyday life (vv. 23-25), the Yahweh faith community is summoned to thanksgiving and dependence in a lifestyle of praise. The rhetoric of the text is to convince this Yahweh community of a cohesive bond of reciprocal 'steadfast love.'

E SYNTHESIS

The twin psalms, Pss 135 and 136, are both hymnic and inspired texts with strong cultic features. In both psalms, exodus allusions and motifs play a role in the composers' aim of building their own theological thrust. The following perspectives prevail:

• The composers of both psalms employ exodus motifs in a selective and independent manner. In an eclectic way, each psalm portrays a number of collected experiences which serve each psalm's own poetic strategies and theological emphases.

• In both psalms, the exodus motifs contribute, amongst others, to the portrayal of Yahweh as the God of Israelite history, who controls and govern this sphere of Israelite life. As universal God of creation, Yahweh's supremacy over all other gods, his power over life and death (firstborns) and his guidance and protection in life-endangering situations in history are portrayed.

• Although both psalms sketch Yahweh as the incomparable, supreme God over all other gods, the psalmists (authors or composers) utilised the exodus motifs to underscore different aspects of their own theological thrusts. In Ps 135, they indeed serve as witness to illustrate Yahweh's incomparability as supreme, powerful God who gives and controls life as a living God over and against lifeless 'idols' and the powerless Pharaoh. In Ps 136 the exodus motifs form building stones in which every deed of deliverance, protection, guidance and protection functions as witness of Yahweh's 'goodness' and 'steadfast love' for his people. Here the monotonous refrain ("for his steadfast love endures forever") determines the direction (Leserichtung) of its theological emphasis.

• The polemic with other, foreign gods, idols or powers is evident in both psalms. This underscores the exilic, post-exilic dating of both psalms

and the theological inclination of the sole rulership of the Israelite God Yahweh, who should be revered as the only God of the Second Temple period and onwards.

• In both psalms, the exodus allusions and motifs form part of the reasons or motivation why Yahweh should be hailed as God of creation and Israelite history. They therefore contribute to Israelite (and universal) praise of this deity-Ps 135 as Song of Praise (Hallel) and Ps 136 as Thanksgiving psalm (Todah). Both psalms confirm trust in this monotheistic God and aim to convince the faith community to engage in a lifestyle that characterises and echoes Yahweh's deliverance, goodness and steadfast love.

• For African Contextual Hermeneutics, the context of the reader and the need of Africans constitute a core priority. In the words of the African Bible Commentary, the two psalms indeed confirm for Africans (and all people) that, "we can praise God not only for what he did at the time of the exodus, but also for all that he has done since then. Above all, we can praise him for having delivered us from sin and brought us into God's family, where we are heirs with Christ (Rom 8:17)." God remembers people in their 'low estate,' whatever the situation of suffering that may be.60

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamo, David T. "Reading Psalm 109 in African Christianity." Old Testament Essay 21/3 (2008): 575-592. [ Links ]

___________. "Decolonizing Psalm 91 in an African Perspective with Special Reference to the Culture of the Yoruba People of Nigeria." Old Testament Essays 25/1 (2012): 9-26 [ Links ]

___________. "Ancient Israelite and African Proverbs as Advice, Reproach, Warning, Encouragement and Explanation." HTS Theological Studies 71/3 (2015): 1 -11. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.2972. [ Links ]

___________. "The Burning Bush (Ex 3:1-6): A Study of Natural Phenomena as Manifestation of Divine Presence in the Old Testament and in African Context." HTS Theological Studies 73/3 (2017): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4576. [ Links ]

___________. "Reading Psalm 23 in African Context." Verbum et Ecclesia 39/1 (2018): 18. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v39i1.1783. [ Links ]

___________. "Reading Psalm 35 in African (Yoruba) Perspective." Old Testament Essays 32/3: (2019): 938-957. [ Links ]

___________. "Reading Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) Perspective." Verbum et Ecclesia 41/1 (2020): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2029. [ Links ]

Adeyemo, Tokunboh, ed. Africa Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006. [ Links ]

Allen, Leslie C. Psalms 101-150. Word Biblical Commentary Waco: Word Books, 1983. [ Links ]

Anderson, Arnold A. The Book of Psalms. Volume II. New Century Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1912. [ Links ]

Burden, Jasper J. Psalms 120-150. SBG. NG Kerkuitgewers: Kaapstad, 1991. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard J. Psalms 73-150. Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2003. [ Links ]

DeClaissé-Walford, Nancy, Rolf A. Jacobson and Beth L. Tanner The Book of Psalms. NICOT. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans, 2014. _. Psalms: Books 4-5. Wisdom Commentary. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2020. [ Links ]

Deissler, Alfons. Die Psalmen. Düsseldorf: Patmos Verlag, 1964. [ Links ]

Duhm, Bernhard.Die Psalmen. Kurzer Handkommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg: Mohr (Siebeck), 1922. [ Links ]

Dunn, James D.G. and Rogerson John W., eds. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Eaton, John H. Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation. New York: T & T Clark, 2003. [ Links ]

Emanuel, David. "The Psalmist's Use of the Exodus Motif. A Close Reading and Intertextual Analysis of Selected Exodus Psalms." PhD thesis, Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 2001. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. Psalms Part 2 and Lamentations. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Gillingham, Susan. "Studies of the Psalms: Retrospect and Prospect." The Expository Times 119/5 (2008): 209-216. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. Psalms 90-150. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2008. [ Links ]

Goulder, Michael. D. The Psalms of the Return (Book V, Psalms 107-150). Journal for the Study of Old Testament Supplement Series 258. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Human, Dirk J. "Psalm 136: A Liturgy with Reference to Creation and History." Pages 13-88 in Psalms and Liturgy. Edited by Dirk J. Human and Cas Vos. Journal for the Study of Old Testament Supplement Series 410. London: T&T Clark International, 2004. [ Links ]

___________. "Ps 132 and Its Compositional Context(s)." Pages 129-150 in Psalmen und Chronik. Herausgegeben von Friedhelm Hartenstein und Thomas Willi. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 101. Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 2019. [ Links ]

Kidner, Derek. Psalms 73-150. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries. London: Intervarsity Press, 1915. [ Links ]

Koch, Klaus. "Der Psalter und seine Redaktionsgeschichte." Pages 243-211 in Der Psalter in Judentum und Christentum. Edited by Erich Zenger. Freiburg: Herder Verlag, 1998. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalmen 60-150. Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament XV/2. Neukirchen: Neukirchener Verlag, 1918. [ Links ]

Mays, James L. Psalms. Interpretation. Louisville: John Knox, 1994. [ Links ]

Millard, Matthias. Die Komposition des Psalters. FAT 9. Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1994. [ Links ]

Oesterley, William O.E. The Psalms. New York: Macmillan, 1939. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. "Psalms." Pages 364-436 in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Edited by James D.G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Ravasi, Gianfranco. "Psalms 90-150." Pages 841-859 in The International Bible Commentary. Edited by William R. Farmer ea. Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Hans. Die Psalmen. Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15. Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1934. [ Links ]

Seybold, Klaus. Die Psalmen. Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15. Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1996. [ Links ]

Terrien, Samuel. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Van der Ploeg, Johannes P.M. Psalmen deelII: Psalm 76-150. Roermond: J. J. Romen & Zonen-Uitgevers, 1974. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2003. [ Links ]

Weiser, Arthur. The Psalms: A Commentary. London: SCM Press, 1962. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich. "Psalm 135" Pages 659-672 in Psalmen 100-150. Herders Theologicher Kommentar zum AT. Herausgegeben von Frank Lothar Hossfeld und Erich Zenger. HThKAT: Freiburg, 2008. [ Links ]

___________. "Psalm 135. Lobpreis der Einzigartigkeit des Gottes Israel." Pages 811-819 in Die Psalmen: Psalmen 101-150. Hrsg von Frank-Lothar Hossfeld und Erich Zenger. Neue Echter Bibel. Würzburg: Echter Verlag, 2012. [ Links ]

Submitted: 28/04/2020

Peer-reviewed: 06/07/2021

Accepted: 04/08/2021

Dirk Human is professor in Old Testament Studies in the Department of Old Testament and Hebrew Scriptures, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0346-4209. Email address: dirk.human@up.ac.za

1 David T. Adamo, "The Burning Bush (Ex 3:1-6): A Study of Natural Phenomena as Manifestation of Divine Presence in the Old Testament and in African Context," HTS Theological Studies 73/3 (2017): 1-8, https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4576; "Reading Psalm 23 in African Context," Verbum et Ecclesia 39/1 (2018): 1-8, https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v39i1.1783. David T. Adamo, "Reading Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) Perspective," Verbum et Ecclesia 41/1 (2020): 1-10, https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2029. See also David T. Adamo, "Ancient Israelite and African Proverbs as Advice, Reproach, Warning, Encouragement and Explanation," HTS Theological Studies 71/3 (2015): 1-11, http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.2972.

2 Adamo, D.T. "Reading Psalm 109 in African Christianity." Old Testament Essay 21/3 (2008): 575-592; "Decolonizing Psalm 91 in an African Perspective with Special Reference to the Culture of the Yoruba People of Nigeria." Old Testament Essays 25/1 (2012): 9-26; "Reading Psalm 35 in African (Yoruba) Perspective." Old Testament Essays 32/3: (2019): 938-957.

3 Cf. James Mays, Psalms (Interpretation; Louisville: John Knox, 1994), 415.

4 Cf. Erich Zenger "Psalm 135," in Psalmen 100-150. Herders Theologicher Kommentar zum AT. Hrsg von Frank Lothar Hossfeld und Erich Zenger (HThKAT: Freiburg/Basel/Wien, 2008), 661; "Psalm 135: Lobpreis der Einzigartigkeit des Gottes Israel," in Die Psalmen. Psalmen 101-105 (Hrsg von Frank-Lothar Hossfeld und Erich Zenger; Neue Echter Bibel, Würzburg: Echter Verlag, 2012), 811.

5 See Nancy DeClaissé-Walford (ed. Nancy DeClaissé-Walford, Rolf A. Jacobson and Beth L. Tanner, The Book of Psalms (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 949, for details.

6 There are several connections between Pss 135-136 and these two groups. Matthias Millard, Die Komposition des Psalters (FAT 9; Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1994), 4, shows the "formgeschichtliche Parallele" between Pss 134 and 136. Cf. also Michael Goulder, The Psalms of the Return (Book V, Psalms 107-150) (JSOT Supplement Series 258; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 216; Richard Clifford, Psalms 73-150 (Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries; Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2003), 264, 269 and Beat Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150 (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2003), 327-328, 331 -332, for textual connections and relationships. DeClaissé-Walford, The Book of Psalms, 943, 948-949; also Zenger, Psalmen 101150, 811-814.

7 See Klaus Koch, "Der Psalter und seine Redaktionsgeschichte," Der Psalter in Judentum und Christentum (ed. Erich Zenger Freiburg: Herder Verlag, 1998), 243-211.

8 Dirk Human, "Ps 132 and Its Compositional Context(s)," in Psalmen und Chronik (Hrsg von Friedhelm Hartenstein und Thomas Willi; FAT 101; Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 2019), 129-150 (130), describes the broad context of Book V of the Psalter.

9 See Alfons Deissler, Die Psalmen (Düsseldorf: Patmos Verlag, 1964), 525; Arnold Anderson, The Book of Psalms. Volume II (New Century Bible Commentary; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1912), 889; Leslie Allen, Psalms 101-150 (Word Biblical Commentary; Waco: Word Books, 1983), 224; Mays, Psalms, 415; Willem S. Prinsloo, "Psalms," Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (ed. James D.G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 364-436 (429); John H. Eaton, Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation (London/New York: T & T Clark, 2003), 449; and Zenger, Psalmen 101-150, 814.

10 Cf. Gianfranco Ravasi, "Psalms 90-150," in The International Bible Commentary (ed. William R. Farmer, ea; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1998), 854.

11 Zenger, Psalmen 101-150, 812-813, has assessed the interrelationships with other biblical texts.

12 See Allen, Psalms 101-150, 228 and Mays, Psalms, 416.

13 Cf. Klaus Seybold, Die Psalmen (Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15; Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1996), 503.

14 This is suggested by Arthur Weiser, The Psalms: A Commentary (London: SCM Press, 1962), 790, due to the weather descriptions in verse 7. Weiser also identifies the presence of the covenant in the cult (vv. 13-14) as the people express their faithfulness to Yahweh and repudiate the foreign gods.

15 Cf. Anderson, The Book of Psalms, 888; Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalmen 60-150 (Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament XV/2; Neukirchen: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978), 1074 and Ravasi, "Psalms 90-150," 854.

16 Kraus, Psalmen 60-150, 1074 notes a time "in später Zeit'"

17 See Deissler, Die Psalmen, 526; Anderson, The Book of Psalms, 889.

18 Clifford, Psalms 71-150, 264, confirms that the "polemic against divine images (135:15-18) was common in exilic and postexilic writings (Jer 10:1-16a; Isa 40:1820; 41:6-7; 44:9-20)."

19 Erhard Gerstenberger, Psalms Part 2 and Lamentations (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 383, describes this context as a "multireligious society with competing and political systems" in which Jewish congregational assemblies" form the background of this psalm. In this setting, Israel was struggling with her identity.

20 Cf. Kraus, Psalmen 60-150, 1076.

21 This includes the Hebrew relative particle sh (vv. 2, 8, 10) and verb formulations "and killed" (v. 10) and "and gave" (v. 12).

22 Cf. Zenger, Psalmen 101-150, 813; Johannes van der Ploeg, Psalmen deelII: Psalm 76-150 (Roermond: Romen en Zonen, 1974), 135, only speaks about "uit late tijd"

23 Cf. Zenger, Psalmen 101-150, 813. See also Susan Gillingham, "Studies of the Psalms: Retrospect and Prospect," The Expository Times 119/5(2008): 209-216 (210), who follows Gerald Wilson and indicates that Books 4 and 5 address the "shattered hopes" of Israel and focus on the "right living in the present." Nancy deClaissé-Walford, Psalms: Books 4-5 (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2020), li, describes the historical Sitz-im-Leben of Books 4 and 5 as follows: "book 4 is set in exile in Babylon, relates the struggle of the exiles to find identity and meaning in a world of changed circumstances; book 5 celebrates the return to Jerusalem and the reestablishment of temple worship, but without an earthly king." Samuel Terrien, The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 858, motivates a "postexilic" date.

24 Those who fear Yahweh might include proselytes and representatives of the nations.

25 Cf. Eaton, Psalms, 450 and Ravasi, Psalms 90-150, 854.

26 Bernard Duhm, Die Psalmen (Kurzer Handkommentar zum Alten Testament; Freiburg: Mohr (Siebeck), 1922), 450, even refers to the gods Zeus, Poseidon and other gods of the polytheistic faiths. This also supports his later dating of the psalm.

27 In these verses are parallels to Exod 18:11, Ps 115:3 and Jer 10:13. See Derek Kinder, Psalms 73-150 (Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries; London: Intervarsity Press, 1915), 455.

29 The term appears in Deut 7:6; 14:2; 26:18; 1 Chron 19:3 and Mal 3:17.

30 Cf. David Emmanuel, "The Psalmist's Use of the Exodus Motif: A Close Reading and Intertextual Analysis of Selected Exodus Psalms" (PhD thesis, Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 2007), 255.

31 See also the context of 2 Chron 2:4 when Hiram made the same declaration after Solomon's request for wood to build the temple. Compare Pss 95:3 and 96:4.

32 See Pss 78:51; 105:36 and 136:10.

33 Exodus 12:12 - "On that same night I will pass through Egypt and strike down every firstborn of both people and animals, and I will bring judgment on all the gods of Egypt. I am the LORD." Exodus 12:29 - "At midnight the LORD struck down all the firstborn in Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh, who sat on the throne, to the firstborn of the prisoner, who was in the dungeon, and the firstborn of all the livestock as well."

34 Cf. Emanuel, "The Psalmist's Use of the Exodus Motif," 265.

35 I will draw strongly on an earlier exposition of the psalm, Dirk Human, "Psalm 136: A Liturgy with Reference to Creation and History," in Psalms and Liturgy (ed. Dirk J. Human and Cas J.A. Vos; JSOT Supplement Series 410; London: T&T Clark International, 2004), 13-88.

36 Cf. Zenger, Psalmen 101-150, 814. De Claissé-Walford, The Book of Psalms, 948, calls it a "community hymn."

37 This refrain appears in a number of liturgical texts, namely, 1 Chron 16:34; 2 Chron 5:13; 7:3; 20:21; Ezra 3:11; Pss 106:1; 107:1; 118:1-4 and 100:5.

38 See a more complete description of the cultic setting in Human, "Psalm 136," 84-85.

39 Seybold, Die Psalmen, 507.

40 Cf. John Goldingay, Psalms 90-150 (Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms; Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2008), 589.

41 Cf. Anderson, The Book of Psalms, 893 and Kraus, Psalmen 60-150, 1079; Gerstenberger, Psalms Part 2, 389, is convinced that the Passover cannot be identified as "exclusive setting."

42 Cf. William O.E. Oesterley, The Psalms (New York: Macmillan, 1939), 543; Eaton, The Psalms, 452.

43 Cf. The relationship with 2 Chron 7:3, 6 where the formula 'for He is good, his love endures forever' appears in verse 1. Yahweh's guidance, protection and sustenance are re-lived with the recital of Ps 136.

44 Cf. Hans Schmidt, Die Psalmen (Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15; Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 1934), 240 and Weiser, The Psalms, 793. The focus on verse 25 ('he who gives food to every creature') convinces some scholars of this possibility.

45 Deissler, Die Psalmen, 529, suggests this possibility together with the Passover.

46 The psalm was probably sung by the returning Israelites to Jerusalem (Jer 33:11) after exile or at the inauguration of the Second Temple (Ezra 3:11). See Jasper Burden, Psalms 120-150 (SBG; NG Kerkuitgewers: Kaapstad, 1991), 117.

47 Zenger, Psalms 101-150, 813, 820, summarises the arguments for the dating to approximately 400 BCE.

48 See Ezra 1:2; Neh 1:4 and 2:4. Cf. Duhm, Die Psalmen, 452.

49 Van der Ploeg, Psalms 76-150, 418, indicates that the deuteronomistic late language forms and vocabulary in verses 23, 24 and 26 rather point to a post-exilic period, "zelfs late tijd: 3de eeuw?"; also Goulder, Psalms of the Return, 221.

50 Terrien, The Psalms, 863, indicates a postexilic date. See also Gillingham, "Studies of the Psalms," 210, for the context of Books 4 and 5 as well as Nancy deClaissé-Walford, Psalms: Books 4-5, li, for the historical setting of Books 4 and 5.

51 Cf. Zenger, Psalmen 101-150, 814.

52 Compare verse 10 with Exod 11-12; verse 11 with Exod 7:5; 18:1; 20:1; verse 12 with Exod 6:1, 6; verse 13 with Exod 14:16-31 (especially vv. 16-17 and 21); verse 14 with Exod 14:22; and verse 15 with Exod 14-27. The psalm also employs allusions and motifs from Deuteronomy and the deuteronomists as well as from priestly texts (compare vv. 7-9 with Gen 1:14-16; see Human, "Psalm 136," 76. There are also various mythological allusions in the psalm (see vv. 2-3, 5-6, 13, 15).

53 See Num 8:17; 33:4; Pss 78:51; 105:36 and 135:8.

54 Cf. Emanuel, "The Psalmist's Use of the Exodus Motif," 292-293.

55 Deuteronomy 4:34: "Has any god ever tried to take for himself one nation out of another nation, by testings, by signs and wonders, by war, by a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, or by great and awesome deeds, like all the things the LORD your God did for you in Egypt before your very eyes?" (NIV).

56 Exod 5:12: "You stretch out your right hand, and the earth swallows your enemies" (NIV) and Exod 7:5: "And the Egyptians will know that I am the LORD when I stretch out my hand against Egypt and bring the Israelites out of it" (NIV).

57 Compare verse 13 with Exod 14:16-31, especially 16ff and 21; verse 14 with Exod 14:22; and verse 15 with Exod 14:22.

58 Cf. Human, "Psalm 136," 81.

59 In Ps 74:13, a similar idea prevails, but here Yahweh crushes the heads of the monsters as parallelism for splitting the Reed Sea: "It was you who split open the sea by your power; you broke the heads of the monster in the waters" (NIV).

60 Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 1650-1651.