Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 no.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n1a10

PART I: GENERAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Making Meaning of Wisdom in Psalm 119 and in Contemporary African Contexts

Michael Kodzo Mensah

University of Ghana, Legon

ABSTRACT

Psalm 119 has continually posed challenges to its interpreters owing to the difficulty of relating its unique acrostic structure to its thematic focus. The question of wisdom, especially as expressed in the Ps 119, is one such thematic problem which confronts both the Western and the African reader. This article, taking cognisance of the importance of the structural integrity of the psalm, identifies three dimensions of wisdom in Ps 119 which can be traced to the wider biblical Wisdom corpus. Using the African Biblical Hermeneutical method, it shows that these different dimensions of wisdom are equally found in African proverbs and underline the value of using this method as a vehicle for dialogue between the African and the Western reader of the Bible.

Keywords: Psalm 119, Biblical Wisdom, African Proverbs, African Hermeneutics

A INTRODUCTION

Psalm 119 is an extraordinary piece of literature. Its 176 verses make it the longest psalm in the Psalter and the longest chapter in the Bible. Its form is also peculiar. It preserves an eight-line acrostic arrangement unknown in the entire corpus of ancient Near Eastern literature and it has thus been described as a psalm "sui generis," that is, a unique psalm.1 What has continually baffled scholars, however, is the seemingly repetitive content of the psalm, variously described as "artificial," "loose and rambling," "obscure" or even "monotonous,"2 a problem which has led to the question of whether Ps 119 has any coherence at all or even any binding theme. It is the foregoing which provoked Duhm's damning assessment of the Psalm with his assertion, "jedenfalls ist dieser „Psalm" das inhaltloseste Produkt, das jemals Papier Schwarz gemacht hat."3

The problem of the supposed thematic incoherence of Ps 119 described above is further compounded by the question of Wisdom in the Psalm. Is Ps 119 a Wisdom psalm or does it only contain Wisdom themes? If it does, what type of Wisdom does it seek to espouse? Indeed, the above questions are not made any easier by a Psalmist who purports to have more understanding than his elders (Ps 119:100).

I will attempt in this article to expose the theme of Wisdom in Ps 119 as an important element of the psalm's didactic intent. I will further argue that the three dimensions of the Wisdom found in this psalm correspond to the same dimensions of Wisdom in the biblical Wisdom corpus. Using the African Biblical Hermeneutical method, I will demonstrate that these same dimensions of Wisdom are found in African proverbs. Not only does the method help to explain this psalm to the African reader. It also becomes a vehicle for dialoguing with the Western reader confronted with the difficulty of interpreting the same text.

B PROBLEM OF THEMATIC COHERENCE OF PS 119

A quick survey at recent scholarship on the theme of Ps 119 unfortunately does little to absolve the psalm of Duhm's charge of incoherence. Deissler in his study of the Psalm describes it as an "anthology" and an amalgam of words, motifs and literary forms from extant Hebrew literature.4 Soll disagrees with Deissler and sees a coherence in the psalm based on its genre as a lament psalm.5 He argues that the psalm shows a six-part structure in which "the movement of the individual lament from complaint to assurance recapitulated several times."6 The problem with Soll's solution is that his genre-inspired structure could not resolve the problem of the psalm's thematic coherence, leading Welch to conclude that Soll's attempt at finding the logic to the psalm was "not exhaustive."7

Another set of attempts to resolve the problem of Ps 119 are those which adopt a structural analysis to study the psalm. Foremost among these is the work of Auffret who presents a dense network of interrelationships between the strophes and divisions of the psalm.8 The results are modest, with Nocquet observing in his review that the scholar's analysis has done little to contribute to the understanding of the psalm's theological import.9 Reynolds subsequently has returned to Deissler's concept of an anthology seeking to explain, with difficulty, that the "logical gaps" in Ps 119 were intended by the poet in order to achieve suasive purposes.10 The problem with this attempt at a solution, obviously, is that it is a circular argument to suggest that the psalm's apparent lack of coherence is because the Psalmist did not want to be coherent.11 Lastly, Meynet analyses the psalm through the rhetorical approach adopting a structure based on his French translation of the text rather than the original Hebrew text, an approach which would cast doubts on his findings.12

1 Structure of Ps 119

I have already underlined the problem of the thematic coherence of Ps 119. My solution to the problem is to propose a six-canto division of the poem.13 By so doing, it becomes possible to discern a logical line of thought running through all six cantos. The division of the poem into cantos is as follows:

• Canto I: vv. 1-16

• Canto II: vv. 17-48

• Canto III: vv. 49-88

• Canto IV: vv. 89-128

• Canto V: vv. 129-160

• Canto VI: vv. 161-176

1a Canto I: (vv. 1-16): The Perfect Way and the Psalmist's Way

Canto I (vv. 1-16), which opens the psalm, is composed of four strophes and introduces the theme of the "Two Ways" (דרך). Strophe Ia (vv. 1-4) deals with the blessedness of the man whose way (דרכיו, v. 3) is perfect. This outlook of perfection is the ideal. In Strophe Ib (vv. 5-8) however, the reality of the Psalmist's own way (דרכי, v. 5) is revealed as fraught with inadequacies for which reason he prays that he might not be put to shame (v. 7). This same imperfection of the Psalmist's way re-emerges in Strophe IIa (vv. 9-12) in which the psalmist poses the rhetorical question, "How can a young man purify his way?" Strophe IIb (vv. 13-16) ends on a positive note, returning to the ideal referred to in Strophe I. The psalmist speaks of the delight in meditating on YHWH's Torah and indicates his perpetual remembrance of them.14 The Canto is thus thematically arranged in a chiastic structure as follows:

vv. 1-4 A The Blessedness of Observing Torah as YHWH's Way (דרכיו)

vv. 5-8 B The Instability of the Psalmist's Way (דרכי)

vv. 9-12 B" The Question of the Young Man's Way (ארחו)

vv. 13-16 A" The Delight of Studying Torah as YHWH's Way

(דרך/ ארחתיך)

1b Canto II (vv. 17-48): The Choice between the Two Ways

Canto II (vv. 17-48) is composed of eight strophes. Strophes IIIa (vv. 17-20) and IIIb (vv. 21-24) introduce a new polemic into the psalm. In Strophe IIIa, the Psalmist calls himself YHWH's servant עבדך, v. 17) and describes himself as a wayfarer. In Strophe IIIb however, he is faced with adversaries (זדים, v. 21) who act contrary to YHWH's Torah. The reason for the polemic in these preceding strophes appears to be explained in the following strophes. In Strophe IVa (vv. 25-28), the psalmist is faced with "Two Ways": His own way (דרכי, v. 26) and YHWH's way (דרך־פקודיך, v. 27). The Psalmist is thus faced with a choice. In Strophe IVb (vv. 29-32), this choice (בחר, v. 30) between the Psalmist's own way and YHWH's way gains further clarity with the introduction of the opposing categories, the way of falsehood (דרך־שקר, v. 29) and the way of truth (דרך־אמונה, v. 30).

Strophe Va (vv. 33-36) deepens the discourse on the question of choice through the repetition of the term לב (heart) in vv. 34 and 36. The heart is the seat of volition and the instrument of choice. Nonetheless, for this reason the heart must be instructed ירה, hi., v. 33). In Strophe Vb (vv. 37-40), in correspondence to the "Two Ways" the Psalmist makes two contrasting requests. The first is a request for the removal of reproach (v. 39), a consequence of the way of falsehood (v. 29); the second is a request for the bestowal of life (vv. 37.40), a consequence of the way of truth (v. 30).

In the last two strophes of Canto II, the Psalmist returns to opposing themes at the beginning of the Canto. Strophe VIa (vv. 41-44) focuses on Covenant faithfulness. This is a trait of YHWH's servant (v. 17) mentioned in Strophe IIIa. Meanwhile, in Strophe VIb (vv. 45-48), the Psalmist remains steadfast to the Torah amidst the challenge of adversaries who are opposed to it, the same adversaries mentioned in Strophe IIIb. The entire Canto may thus be structurally set out as follows:

(A) Strophes III

a. YHWH's Servant as Wayfarer

b. The Challenge of the Adversaries

(B) Strophes IV

a. The Two Ways ( a)

b. The Choice between the Ways (b)

(B") Strophes V

a. The Informed Decision for Torah (b ")

b. The Two Requests ( a ")

(A") Strophes VI

a. Appeal to YHWH's Covenant Faithfulness

b. Manifestation of Torah Fidelity in the face of Adversaries

1c Canto III (vv. 49-88): Acknowledgment of Error and Chastisement

Canto III, which is composed of ten strophes, is arranged concentrically. Strophe VIIa (vv. 49-52) begins with the theme of remembrance (זכר, v. 49) of YHWH's faithfulness, the theme found at the end of the preceding Canto II. The theme of remembrance continues in Strophe VIIb (vv. 53-56) with the object of remembrance here being YHWH's name and his statutes (v. 55).

In Strophe VIIIa (vv. 57-60), the return of the keyword דרך (way) in v. 59 signals an important moment in the psalm. The Psalmist states that he has considered his ways (דרכי) and has returned (שוב) to YHWH's decrees. The MT reading is particularly significant given that the LXX in Ps 118:59a reads διελογισάμην τάς οδούς σου (Ps 118:59) indicating that the Psalmist has considered YHWH's ways and not his own ways (דרכי) as the MT reads.15 If the MT reading is upheld, it would suggest that the Psalmist has become aware of his ways (דרכי), those same ways which in Strophe IVa (v. 26) were found to be opposed to YHWH's way (v. 27). This means, contrary to previously held positions16, that the Psalmist, conscious of his personal errors, has now returned to YHWH's decrees. Strophe VIIIb (vv. 61-64) follows logically from the preceding strophe by discussing the justice and mercy of YHWH. In v. 62, the Psalmist invokes YHWH's justice (צדק) in the face of the threat of the wicked. In v. 64, he invokes his mercy (חסד) for those who fear him, a category which should include the Psalmist himself who has acknowledged his errors and seeks to make amends.

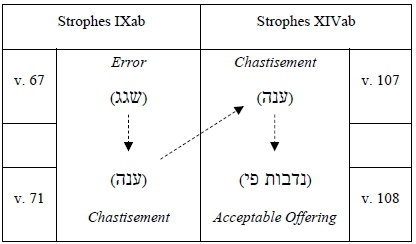

The next two Strophes IXa (vv. 65-68) and IXb (vv. 69-72) occupy the centre of the concentric structure of Canto III. In Strophe IXa, the Psalmist returns to the question of his error. In v. 67 he admits, "Before I answered, I strayed." The admission of the Psalmist that he strayed (אני שגג) corroborates the earlier statement in v. 59 that he has considered his ways and has returned to YHWH's decrees. The subsequent Strophe IXb thus goes to explain the affliction of the Psalmist. On the one hand, he is the object of false accusations of his adversaries. On the other hand, the humiliation he suffers (ענה, v. 71) is pedagogical, an instrument of correction for having strayed.

Strophe Xa (vv. 73-76) continues the discourse on the justice of YHWH that began in the preceding strophe. YHWH in v. 75 is the one who humbles the Psalmist by both teaching him his Torah and instructing him. This is what accounts for the Psalmist's ability to return (שוב, v. 79) to YHWH in Strophe Xb (vv. 77-80). However, disgrace (בוש) awaits the arrogant who would not submit to his instruction (v. 78).

In Strophe XIa (vv. 81-84), the psalmist is in crisis. He describes his condition as being "like a skin in smoke" (v. 83a), as a person experiencing the kind of judgment reserved for the wicked. In spite of the above, the Psalmist expresses his trust in YHWH's faithfulness by declaring that he will not forget (שכ) his statutes (v. 83). Finally, Strophe XIb (vv. 85-88) closes Canto III with a reaffirmation by the Psalmist never to abandon (עזב, v. 87) YHWH's Torah even in the face of the hostility of his adversaries.17 The canto may be arranged as follows:

Strophes VIIab (vv. 49-56)

Remembrance of YHWH's Covenant faithfulness (זכר - נח)

Strophes VIIIab (vv. 57-64)

Self-Introspection and Return (שוב)

YHWH's Justice (צדק/ משפט) and Mercy (חנן/ חסד)

Strophes IXab (vv. 65-72)

Goodness of YHWH (טוב)

Confession of Error (שגג)

Chastisement (ענה Pu)

Goodness of YHWH (טוב)

Strophes Xab (vv. 73-80)

YHWH's Justice (צדק / משפט) and Mercy (רחם / חסד)

Knowledge of YHWH and Return (שוב)

Strophes XIab (vv. 81-88)

YHWH's Covenant faithfulness not forgotten (שכח/ נחם)

1d Canto IV (vv. 89-128): The Vow and Recommitment to the Torah

Canto IV is another ten-strophe Canto corresponding to the preceding Canto III. This Canto, also structured concentrically, opens with Strophe XIIa (vv. 89-92), which focuses on the stability of YHWH's Torah. Torah is established both temporally (לעולם, v. 89) and spatially (ארץ- שמים). In Strophe XIIb (vv. 93-96) however, this temporal and spatial infiniteness of Torah is contrasted with the finiteness (כלה) of human experience (v. 96).

Strophe XIIIa (vv. 97-100) and XIIIb (101-104) deal with two contrasting themes namely love for Torah and hatred for the False Way respectively. In the first line of Strophe XIIIa, the Psalmist declares his love for Torah (אהב, v. 97); in the last line of Strophe XIIIb, to the contrary, he declares hatred (שנא) for the Way of Falsehood (v. 104).

Strophes XIVa (vv. 105-108) and XIVb (vv. 109-112) occupy the centre of Canto IV. In Strophe XIVa, the Psalmist swears an oath (שבע) to observe Torah (v. 106). In v. 107 he recalls his chastisement (ענה Ni) as correction for having strayed from Torah. In v. 108, the Psalmist further vows to offer a verbal sacrifice (נדבות פי). In Strophe XIVb, he then declares joy (נחל) as being the reward for faithfulness to Torah (v. 111).

Strophes XIVa and XIVb are particularly important to the thematic development of the Psalm. Structurally, they correspond to Strophes IXa (vv. 6568) and IXb (69-73), which also are collocated at the centre of Canto III (vv. 49-88). Thematically, there appears to be a logical sequence of thought between these strophes as follows:

In Strophe IXa, the Psalmist acknowledged his error (שגג), having strayed from Torah (v. 67). The result of this error was a corrective chastisement (ענה). In Strophe XIVa, the same chastisement (ענה) is referred to again (v. 107). The Psalmist consequently pledges to offer a verbal sacrifice (נדבות פי) possibly in atonement for the infraction. The result of this action in v. 111 is the reward of joy (נחל).18

Strophes XVa (vv. 113-116) and XVb (vv. 117-120) return to the themes of love and hatred found in Strophes XIIIa and XIIIb but in the reverse order. In Strophe XVa, the Psalmist declares his hatred (שנא) for double-dealing and his love for Torah (v. 113). In Strophe XVb however, the Psalmist loves Torah (אהב) and fears it (vv. 119.120). Strophes XVIa (vv. 121-124) and XVIb (125-128) close Canto III. In Strophe XVIa, the Psalmist raises the concern of the frailty of the Psalmist. The term כלה which appeared in Strophe XIIb (v. 96), describing the finiteness of all things, is now applied here to the human person. Strophe XVIb structurally signals the end of the Strophe by the anaphora על־כן in vv. 127 and 128. In this final strophe of Canto IV, the Psalmist calls on YHWH to act (v. 126), in the face of the adversaries who disobey his commands.19 The structural arrangement of Canto IV may be observed as follows:

Strophes XlIab

Stability of Torah revealed in Space and Time (לעולם-היום)

The finiteness of all things (כלה)

Strophes XlIIab

Love for Torah (אהב)

Hatred for False way (שנ א)

Strophes XlVab

Oath to Observe Torah (שבע)

Chastisement for Error (ענה Ni)

Acceptable Offering (נדבות פי)

Inheritance as Reward (נח ל)

Strophes XVab

Hatred for Double-dealing (שנא)

Love for Torah (אהב)

Strophes XVIab

The Frailty of the Psalmist (כלה)

Time to Act to Restore Stability of Torah (עת)

1e Canto V (vv. 129-160): YHWH's Covenant Faithfulness

Canto V is made up of eight strophes with the theme of faithfulness to YHWH's covenant as the overarching theme. In Strophe XVIIa, the Psalmist recalls YHWH's covenant love in history especially his wonders (פלא) in the exodus event (v. 129). This love, mentioned in the preceding strophe, is both an invitation to commitment (שמר) to Torah in Strophe XVIIb and the reason for lament for those who do not (v. 136). In Strophe XVIIIa, the Psalmist emphasises the justice (צדק) of YHWH (vv. 137.138). In Strophe XVIIIb, he once again describes himself as a youth (צעיר), recalling same in v. 9, while reiterating YHWH's Covenant faithfulness.

In Strophe XIXa (vv. 145-148), the Psalmist returns to the theme of commitment to Torah while calling on YHWH to save him. His confidence is based on YHWH's Covenant Love which in Strophe XIXb (vv. 149-153) is emphasised as an event not just in the past, but forever (v. 152). In Strophe XXa (vv. 153-156), the Psalmist focuses on the corresponding dimension of YHWH's nature, his mercy (רחם). In Strophe XXb (vv. 157-160), the final strophe of the canto, there is an accumulation of covenant terms - אהב (v. 159a) - חסד (v. 159b) - אמת (v. 160a); YHWH's covenant faithfulness is assured and it is forever.20The canto is arranged as follows:

A Strophe XVIIa: YHWH's Covenant Love (אהב /ח) in History (פלאות)

B Strophe XVIIb: Torah Commitment (שמר) and Illumination (אור)

C Strophe XVIIIa: YHWH as Just One (צדיק)

D Strophe XVIIIb: Covenant Faithfulness (אמת) and Justice (צדק)

B " Strophe XIXa: Torah Commitment (שמר) Despite the Darkness(נשף)

A " Strophe XIXb: YHWH's Covenant Love (חסד / אמת) Forever (לעולם)

C " Strophe XXa: YHWH's Abundant Mercy (רחם)

D" Strophe XXb: YHWH's Covenant Love (חסד - אמת) and Justice (צדק)

Canto VI (vv. 161-172): The Straying of YHWH's Servant

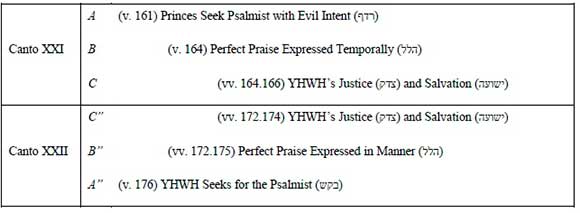

The final Canto VI (vv. 161-172) is made up of four Strophes. In Strophe XXIa (vv. 161-164), the Psalmist's adversaries seek for him (רדף) with evil intent (v. 161). This however does not prevent him from giving YHWH perfect praise (הלל). In Strophe XXIb, the Psalmist sings of YHWH's justice and salvation (vv. 164.166). The same themes of justice and salvation (vv. 170.172) are the subject of the Psalmist's song in Strophe XXIIa (vv. 169-172). Canto VI ends with Strophe XXIIb (vv. 173-176) with an admission by the Psalmist that he had strayed like a lost sheep. However, his cry to YHWH to seek him (v. 176) signifies confidence in God's mercy and faithfulness. The Canto is arranged as follows:21

2 Thematic focus of Ps 119

The above discussion of the structure of Ps 119 reveals a steady thought progression running through the psalm from the beginning to the end. This may be summarised as follows:

A Stanza 1 (vv. 1-16): Introduction: The Perfect Way and the Psalmist's Way

B Stanza 2 (vv. 17-48): Choice between the Way of Falsehood and the Way of Truth

C Stanza 3 (vv. 49-88): Acknowledgement of Error and Chastisement

C" Stanza 4 (vv. 89-128): Vow and Recommitment to Torah

B" Stanza 5 (vv. 129-160) Covenant Faithfulness and Love as the Quintessence of Torah

A " Stanza 6 (vv. 161-176): Conclusion: Perfect Praise and the Straying of YHWH's Servant

The introduction (Canto I: vv. 1-16) presents the problem of the "Two Ways." YHWH's way is opposed to the reality of the Psalmist's own way. In Canto 2 (vv. 17-48), the poem addresses the question of the choice between the two ways. The way of falsehood (v. 29) is diametrically opposed to the way of truth (v. 30), requiring a decision from the Psalmist. In Canto III (vv. 49-88), the Psalmist reflects on his way (v. 59) and in v. 67 he says, "Before I answered I strayed, but now I observe your word." This is without doubt an admission of personal error. The psalmist is however ready to accept God's chastisement as a pedagogical tool (vv. 71.75). In Canto IV (vv. 89-128), the Psalmist not only reiterates his acceptance of chastisement, but also makes a solemn oath to observe God's Torah (v. 106). The process of returning to the Torah being complete, the Psalmist now prays that his verbal sacrifice may be acceptable to God (v. 108), thus affirming God's pardon for the Psalmist who strayed. Canto V (vv. 129160) constitutes the final part of the main body of the Psalm. The Psalmist arrives at his deepest convictions. The Torah summarises all of God's wonderful works in history but above all the quintessence of Torah is God's covenant love and faithfulness (v. 160). The conclusion of the psalm is Canto 6 (vv. 161-176). If the psalm began with the ideal of the blessedness of the perfect (v. 1), it now closes with the perfect praise of the psalmist, who although he strayed, finds joy in his return to YHWH's Torah (v. 176).22

The above reveals the thematic focus as one of return or recommitment to the Torah. The psalm demonstrates how a young man navigates his way through the choice between two opposing ways. Having made a wrong choice, he reflects on his error (v. 59) and returns to the way of truth, accepting chastisement and vowing to recommit himself to YHWH's way (v. 106), in response to YHWH's faithfulness. The psalm's intent is thus didactic. It seeks to lay out a paradigm of how the young person can remain pure (Ps 119:9). This is a concern of biblical Wisdom; the instruction of the young, leading to an upright way of life.

C WISDOM IN PS 119

The question of Wisdom in Ps 119 has generated debate among scholars. The main lines of this debate are whether the psalm should be considered a "Wisdom psalm" or rather, one that shows traits of the Wisdom Tradition. Most scholars however tend toward the latter position. Perdue, for instance, retains the presence of Wisdom traits in Ps 119, citing a number of indices. These include "wisdom forms (sayings, vv. 1-2; the catechetical question and answer, v. 9; and two better sayings, vv. 72.127); wisdom themes" as well as several sapiential vocabulary.23

The difficulty which emerges from the above approach, however, is that the basis for understanding the nature of Wisdom in Ps 119 appears to be based on an amalgam of isolated indices gleaned from the psalm. It is unsurprising that Murphy concludes that Ps 119 is one of those psalms "that show definite wisdom influences, but which defy conventional classification."24

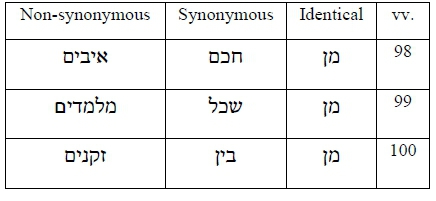

The foregoing, I suggest, requires another look at the question of Wisdom in Ps 119. Auffret and Zenger both agree that Ps 119:97-100 (Strophe XIIIa) contains the densest concentration of Wisdom terminology in the psalm and could thus be a point of departure for the study of Wisdom in the psalm. In this Strophe, three terms for wisdom are employed, "wisdom" (חכם), "discretion" (שכל), and "understanding" (בין). The three terms, though often used as synonyms, preserve their individual nuances. The term שכל is mostly associated with practical skill; בין denotes intellectual capacity, while חכם, the broadest of the three terms, probably encompasses the other two terms. Moreover, the Psalmist compares his wisdom with three groups of persons, his enemies (v. 98), his teachers (v. 99) and elders (v. 100). In all of this, the Psalmist makes a rather astonishing statement to the effect that he possesses more Wisdom than all the three groups. Without seeking immediately to solve all the problems that might arise from the above, it would appear that the image of Wisdom, which is sketched in Strophe XIIIa is a rather pluralistic one. As Murphy has pointed out, "one sign of this multi-faceted wisdom is the several synonyms (e.g., Prov 1:2-5) for wisdom... understanding, knowledge, discipline, cleverness, insight..."25If that is the case, then, the image of Wisdom in Ps 119:98-100 is actually consistent with the nature of Wisdom as a multi-faceted phenomenon, as expressed in the "three classic Wisdom Books"26 of the Hebrew Bible -Proverbs, Job and Ecclesiastes.

1 Three "faces of Wisdom" in the Hebrew Bible

Murphy has observed that the three main Wisdom Books of the Hebrew Bible- Proverbs, Job and Ecclesiastes-each reflects a different dimension of Wisdom.27 The book of Proverbs preserves the most traditional view of Wisdom. As Crenshaw puts it, "all conduct falls into one of two categories: wisdom and folly."28 Moreover, "wisdom (justice) prospers, while folly (wickedness) self-destructs,"29 or in other words, the way of the just leads to life, while the way of the wicked perishes (Prov 1:32-33).

The second book in the Wisdom canon is the book of Job. The author of the book critiques the "traditional ideas of divine justice and retribution upheld in the Book of Proverbs."30 The apparent routine correspondence between goodness and good fortune proposed in Proverbs is questioned. While the author does not insist on a solution to the problem, he attempts to clarify, as far as he could, the question of the human suffering (Job 31:35-37) and especially the suffering of the innocent. Kidner thus observes that Job maintains that "suffering does not necessarily imply any guilt in the victim, nor any failure in his precautions or in his faith."31

The third book, Ecclesiastes, is similar in its outlook to Job, to the extent that both books are in conflict with the optimism of Proverbs. 32 In Ecclesiastes however, the sage resigns himself to the "reality of pain and suffering in human life, and the world in general but considers it 'vanity' to seek for an answer from the Divine (Qoh 8:16-17)."33 Rather than rest on the Jewish sacred traditions, the author derives his arguments from experience-what can be observed under the sun-to justify his views. For Qoheleth, "it is God who has made things beautiful or crooked, setting people up to strive ceaselessly but ultimately keeping back the knowledge/wisdom needed to properly understand the world."34

In sum, while it appears that the author of Proverbs is a supporter of the status quo, Job and Qoheleth challenge this traditional position. The idea of act and consequence cannot be relied on so simply. For Job, the human sufferer has the right to question his suffering,35 but for Qoheleth, all is vanity and all human effort is as counterproductive as chasing the wind, since God has concealed vital knowledge from man.

2 Traditional Wisdom in Ps 119

The above portrait of Wisdom in the Hebrew Bible should now make it possible to return to Ps 119 and interrogate the type of wisdom influences that are observable in it. The first, clearly, is the dimension of traditional wisdom. The theme of the "Two Ways," which we earlier noted in Cantos I and II are representative of the kind of Wisdom found in Proverbs. In Ps 119 also, the Psalmist holds these "Two Ways" in sharp contrast (cf. Ps 1:6). YHWH's Way is associated with blessedness (אשרי, Ps 119:1); it is the way of Truth (v. 30), which is taught to the Psalmist and it is the source of life (v. 37). The Psalmist's way on the contrary is the way that risks leading him to shame (v. 6). It is the way that the Psalmist needs to purify (v. 9); It is the way of falsehood (v. 29), the way on which the Psalmist reflects and turns away from (v. 59). The Psalmist describes it as an evil way (v. 101) and for this reason he hates it (v. 104).

This dualistic conception of reality evident in Ps 119 is not entirely new in the Psalter. In Ps 1, the way of the just is contrasted sharply with the way of the wicked, with the former succeeding and the latter perishing. The same reality emerges in Prov 1:32-33; 2:20-22. Those who walk in YHWH's way prosper. Those who walk in the way of the wicked are doomed.36

3 Questioning traditional Wisdom in Ps 119

The second face of Wisdom in Ps 119 is that which challenges the suffering of the just and the seeming well-being of the wicked. The portrait of the Psalmist in Ps 119 is that of the just man and it is achieved through several protestations of innocence. This innocence of the Psalmist is amply demonstrated especially by his acknowledgement of guilt (v. 67), his acceptance of just correction (v. 71), his offering of reparation in the form of a verbal sacrifice (v. 108), and his decision to return to YHWH's decrees (v. 59). It is in consistence with these that he declares that he follows YHWH's precepts uprightly and hates every false way (v. 128). He is able to identify himself with those who love YHWH's name (v. 132).

The protestations of innocence, however, do not spare the Psalmist of suffering and persecution. In Ps 119:69 for instance, the Psalmist laments that his enemies smear him with lies and subvert him with falsehood (vv. 78.86). His anguish reaches a crescendo in v. 81 when he declares that his life ebbs to a close. In v. 83, he compares himself with "a skin in smoke." The simile is meant to convey sentiments of the Psalmist who, instead of the salvation (ישועה, v. 81) he expects from YHWH, is rather stricken by His judgment (משפט, v. 84). When he declares in frustration, he cries out and asks when (מתי) YHWH would console him (v. 82) and when (מתי) he would deliver justice against his pursuers (v. 84).

The above is in stark contrast to the portrait of the adversaries in Ps 119. The Psalmist portrays them as people of power and influence. They are described as princes (שרים, vv. 23.161) and kings (מלכים, v. 46). They exhibit power over the Psalmist's life by a number of treacherous deeds including laying snares (v. 61) and digging pits for him (v. 85).

Even more revealing is the Psalmist's description of the wicked in Ps 119:70. He says their hearts are as "gross as fat" (חלב, v. 70). This detail is particularly interesting. In Ps 73:7, the same term (חלב) is used by the Psalmist to describe the wicked who seem to prosper while the just suffer. As Luyten has shown, in Ps 73, it is possible to "recognise wisdom themes in smaller motifs and especially some rather striking parallels to the Book of Job. An example is the jealousy of the wicked and the wrath and bitterness at their prosperity."37 The above underlines the presence of the second dimension of Wisdom in Ps 119, the same perspective found in the book of Job.

4 The voice of the sceptic in Ps 119

Psalms 119:99-100 are perhaps the most controversial verses of the Giant Psalm.38 The claim in v. 98 that he has more wisdom than his enemies seems reasonable.39 However, to state that he has more skill than his teachers (מלמדים, v. 99) and more understanding than the elders (זקנים, v. 100) is quite astonishing.

Two scholarly positions illustrate the attempts to resolve this problem. Levenson suggests that the preposition מן in vv. 98-100 be understood as a reference to the source rather than comparison of the wisdom of the Psalmist and those of the other groups.40 The difficulty with this position is that such an understanding of the preposition would also suggest that the Psalmist's wisdom is also from his enemies (v. 98). A second attempt at a resolution is the position of Kirkpatrick who proposes that the elders referred to are simply people of an advanced age rather than the custodians of the Torah to which the term זקנים would normally refer.41 This latter position is however unlikely given the general literary context of Ps 119 with its insistence on the importance of the Torah repeated throughout the psalm. How then should we resolve the claim of the psalmist to have more understanding than the elders?

A close examination of the structure of Strophe XIIIa reveals synonymous-sequential parallelism42 in Ps 119:98-100 as shown below.43

The preposition מן which opens the three verses is the identical element binding vv. 98-100. The term חכם is the broadest of the three wisdom concepts relating to the possession of knowledge and skill applicable in any endeavour. The terms שכל and בין relate to "common sense" and "intellectual discernment," respectively.44 The three terms should thus be understood as synonyms. Read in parallel, they reflect a holistic image of the Psalmist's wisdom. The third set of elements in the parallelism includes the terms איבים (enemies), מלמדים (teachers) and זקנים (elders). While the three terms are grammatically parallel (masculine plural), they are semantically non-synonymous. The teachers (מלמדים) and the elders (זקנים) are considered traditionally the custodians of the Torah. The enemies (איבים) are those considered to be opposed to it. The accumulation of these three terms in parallel in vv. 98-100 should however be understood as communicating a precise message. The Psalmist appears to be issuing a veiled critique against the traditional custodians of the Torah by drawing them in parallel with those who oppose it. A thin line is drawn between the teachers and the elders on the one hand and the enemies on the other hand. This however is not totally surprising within the context of Ps 119, granted that a similar critique is issued in v. 45 against kings whose traditional role includes the defence of the Torah (Ps 101:6-7). What we read in Ps 119:98-100 thus constitutes a voice that is critical of the traditional custodians of the Torah and possibly of their views.

It is against this backdrop that I propose that Ps 119:98-100 be understood in the light of the third dimension of Wisdom namely that view of Wisdom which preserves a somewhat sceptical view of traditional Wisdom, preserved in the book of Ecclesiastes. While this strand of Wisdom does not totally reject the traditional Wisdom of Proverbs, it often contains traits of condescension. Of Ecc 12:9, for instance, Mazzinghi asserts, "beyond being a sage, Qohelet also taught knowledge to the people."45 Mazzinghi has argued that the statement should be understood as a claim that Qoheleth was "not a sage like all the others"; rather, Qoheleth was "something more than a normal sage."46 If this is correct, it would suggest that the claims of superiority of the Psalmist in Ps 119:99-100 are best understood within the third dimension of Wisdom in the Psalm, corresponding to the sceptical voice in the book of Ecclesiastes.

D THE WISDOM OF PS 119 IN CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN CONTEXTS

The relationship between biblical Wisdom literature and Contemporary African Wisdom has been underlined in a number of studies47 Like biblical Wisdom, Mbiti has described African proverbs as "the remains of the oldest forms of

African religious and philosophical wisdom."48 Akoto has subsequently defended the value of reading the biblical Wisdom literature especially in the light of African proverbs and wise-sayings, arguing that their pervasiveness "makes proverbs the most fertile ground upon which the message of the Bible can be planted, nurtured and brought to fruition."49 If this is true, the question of how African Wisdom could possibly assist the contemporary African in making meaning of Ps 119, a psalm which has proven equally enigmatic or even outright nonsensical to the Western reader, could be reframed and posed.50

I would suggest that African Biblical Interpretation provides the vehicle not just for explaining a difficult biblical text to the African reader but also for initiating a dialogue with the Western reader of the text. Indeed, if Adamo is right in his assertion, that, "no one has yet been able to invent such language to encapsulate God's completeness,"51 then, it is only right that the contemporary African participates in the conversation which seeks to unravel what has proven to be a difficult text.52 Our discussion has already shown that Ps 119 is a text which brings together three varying dimensions of Israelite Wisdom. This being so, the psalm itself suggests that its hermeneutical key lies in a multi-faceted approach. In other words, Ps 119 invites the contemporary African to exploit his or her own intellectual traditions as a tool to understanding the psalm. After all, as the Akan and Ewe proverb puts it, "Wisdom is like a baobab tree; a single person's hand cannot embrace it."

1 Traditional biblical Wisdom in African proverbs

The traditional idea of biblical Wisdom namely that the way of the just man prospers while "the way of the wicked perishes" (Ps 1:6) is a concept that runs through several proverbs in the Akan and Ewe languages of Ghana. Five of such proverbs should suffice to illustrate this point of view:

i. Wo bo bra-pa a, wote mu de (If you live a good life, you find it sweet).53

ii. Wo bre wo ho a, na wonya wo ho (If you are industrious, you profit).54

iii. Bone te se ahwanwhanie: eka wo ho a, edi w "akyi (Evil is like a strong perfume: If you apply it, it follows you around).

iv. Wo dua konkonsa aburowa, efifiri wo nan ho (If you plant false corn, it germinates by your feet).55

v. Wobadaa, Kubadae wua ame (Those who do bad things, also die in bad ways).56

The first of the above proverbs states positively the effects of living an upright life. Appiah, Appiah and Agyeman-Duah explain that the Akan proverb means that, "Virtue brings its own reward."57 The second, like it, suggests that hard work pays off. The same idea is stated negatively in the third proverb which uses a simile to compare evil with strong perfume. It suggests that, "You can never rid yourself of the effects of your evil deeds."58 The fourth, like it, uses the imagery of planting and harvest; if one sows evil, one reaps evil. The fifth, which is a proverb in Ewe, corroborates the above position. An evil way of life leads to death. In all these wise-sayings, the idea is to teach the hearer to choose the good life and to avoid evil.

2 Questioning traditional wisdom in African proverbs

While it is quite clear that the majority of proverbs in Akan and Ewe reflect the traditional cause and effect nature of things, there are a few wise-sayings, similar to the view of Wisdom in the book of Job, which question the traditional view of things. Two examples would illustrate this position:

i. Kobonso Adwoa se: "Me na medii kan maa omanfoo tee se osua reba, nanso nsuo baee a, m" aduadee anye yie (The Blue Butterfly Adwoa says "I first informed the people of the state about the approach of the rain, the rain came but my garden did not benefit from it."59

ii. "Adamfoo, adamfoo, ene me nne. " ("Friend, friend," has brought me to my present condition).60

Appiah Appiah and Agyeman-Duah explain that the first of these wise-sayings suggests that, "Good deeds do not necessarily bring the reward you hoped for."61

The second like it, suggests that being kind or generous, which is generally considered a virtue, does not always bring about the expected rewards. A person who has shown great consideration to others might experience betrayal and disappointment in his or her time of need. What is clear is that wisdom in traditional Akan culture understands that things do not always follow a logical system of cause and effect. Good does not always produce good, nor evil, evil.

3 The sceptical voice in African proverbs

A third group of wise-sayings in the Akan culture echoes the view of Wisdom in Ecclesiastes. While these are very limited in number, they nonetheless indicate the presence of the sceptical voice in traditional African wisdom. One of such proverbs says:

i. Dee wasi ne dan mu onna, na anene best so a na orehwan nkoromo (The person who built the house finds it difficult to sleep in, but when the crow comes to perch it starts snoring).62

Appiah Appiah and Agyeman-Duah explain the meaning of the proverb as, "a man (sic) who labors much for something does not always gain what he hopes to on its achievement. A stranger may, however, benefit from it without having made any effort."63 The similarity of this wise saying to the wisdom of Qoheleth is quite striking. The latter says:

18 I hated all my toil in which I had toiled under the sun, seeing that I must leave it to the man who will come after me; 19and who knows whether he will be a wise man or a fool? Yet he will be master of all for which I toiled and used my wisdom under the sun. This also is vanity (Ecc 2:18-19).

The seeming injustice in such a situation however receives strong reactions in other Akan proverbs, one of which says, "The odum tree does not stand at the outskirts of the town to become a great fetish and collect palm nuts, to let the striped mouse eat them and become fat without our eating it."64 Hence, "We do not toil for some useless stranger to eat!"

The above observations regarding diverse strands of wisdom in African proverbs should not be surprising, considering the varying contexts from which these sayings emerge.65 The same is true of the biblical Wisdom tradition which was always aware of similar traditions in Egypt and Mesopotamia.66 Whether in Africa or in the Bible, Wisdom always speaks with varying voices, which also suggests a readiness to listen to the other and an openness towards dialogue.

E CONCLUSION

Our study of Ps 119 began with the problem of understanding whether the psalm has any theme at all. The analysis here has set aside the charge by Duhm that Ps 119 is a "nonsensical psalm" having demonstrated that the psalm does have a logical thematic coherence, that is, in the return of the Psalmist to YHWH's decrees. The above led us to conclude that the psalm does have a Wisdom dimension or a didactic intent namely the instruction of the youth to return from his own way and subsequently to choose the Way of YHWH which leads to life.

The above traditional view of Wisdom consistent especially with the book of Proverbs is however not the only view of Wisdom found in the psalm. The question of the suffering of the just also arises in the psalm, a dimension of Wisdom found in the book of Job. Finally, the scepticism of the Wisdom of Qoheleth is also found woven into the fabric of Ps 119, with the Psalmist even questioning the wisdom of the elders (Ps 119:108). The presence of several mutually critical voices in the psalm suggests a hermeneutical approach that is tolerant of divergent views and seems to invite other viewpoints to the discussion.

In this regard, I have proposed that African Biblical Interpretation becomes an important vehicle for entering into dialogue with both the biblical text and Western approaches to Ps 119. African proverbs and, in this case, Akan and Ewe proverbs are themselves multi-faceted in their approach to Wisdom allowing for a cross-fertilisation of ideas regarding human life and existence. As in Ps 119, traditional views of wisdom exist side by side with other strands of wisdom that contrast with the former. While traditional wisdom is most widely diffused, the dissenting voice is not silenced. Indeed, each one is allowed to have its say. Freedom of expression is perhaps much more inherent to these cultures than otherwise thought. This suggests that even the elders did not mind reasonable challenge to an orthodox position. The Psalmist in Ps 119 claims to have more understanding than the elders. An Akan proverb puts it quite differently: Adwene te se kwaeenoma, nye obaakofoo na onya, literally, "Wisdom is like a forest bird, one person alone cannot catch it"; hence, "you learn from others" or "wisdom is not the possession of one person."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamo, David T. "What Is African Biblical Hermeneutics?" Black Theology 13/1 (2015): 59-72. [ Links ]

Akoto, Dorothy B.E.A. "The Book of Proverbs and Its Relationship to African-Ewe Proverbial Communications." Journal of the Interdenominational Theological Center 37/1-2 (2011): 35-56. [ Links ]

Alonso Schökel, Luis and Cecilia Carniti. Salmos: Traducción, Introducciones y Comentario. Vol. II. Nueva Biblia Espanola. Estella: Verbo Divino, 1993. [ Links ]

Appiah, Peggy, Anthony Appiah and Ivor Agyeman-Duah. Bu Me Be: Proverbs of the Akans. Oxfordshire: Ayebia Clarke, 2007. [ Links ]

Auffret, Pierre. Mais tu élargiras mon c&ur: Nouvelle étude structurelle du Psaume 119. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 359. New York: De Gruyter, 2006. [ Links ]

Briggs, A. Charles and Emile G. Briggs. A Critical andExegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. International Critical Commentary Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1976. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James L. "In Search of Divine Presence: Some Remarks Preliminary to a Theology of Wisdom." Review and Expositor 74/3 (1977): 353-369. [ Links ]

Deissler, Alfons. Psalm 119 (118) und seine Theologie. Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der anthologischen Stilgattung im Alten Testament. MThSH 11. München: K. Zink, 1955. [ Links ]

Dell, Katharine J. "Proverbs 1-9: Issues of Social and Theological Context." Interpretation 63/3 (2009): 229-240. [ Links ]

Duhm, Bernhard. Die Psalmen. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1922. [ Links ]

Fontaine, Carole R. "Wisdom Traditions in the Hebrew Bible." Dialogue 33/1 (2000): 101 -117. [ Links ]

Fox, Michael V. Proverbs 1-9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Freedman, David Noel and Andrew Welch. "A Review of W.M. Soll, Psalm 119. Matrix, Form, and Setting. CBQMS 23. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1991)." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 55 (1993): 774-776. [ Links ]

Gatti, Nicoletta and George Ossom-Batsa. Journeying with the Old Testament. Alte Testament im Dialog 5. Bern: Peter Lang, 2011. [ Links ]

Goulder, Michael D. The Psalms of the Return: Book V, Psalms 107-150. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 258. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Kidner, Derek. The Wisdom of Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Kimilike, Lechion P. "Friedemann W. Golka and African Proverbs on the Poor. " Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 114/2 (2002): 255-261. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick, Alexander F., ed. The Book of Psalms, with Introduction and Notes (I-XLI). CBSC. Cambridge: University Press, 1906. [ Links ]

Levenson, Jon D. "The Sources of Torah: Psalm 119 and the Modes of Revelation in Second Temple Judaism. " Pages 559-574 in Ancient Israelite Religion. FS F. M. Cross. Edited by Patrick D. Miller et al. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987. [ Links ]

Luyten, Jos. "Psalm 73 and Wisdom." Pages 59-81 in La Sagesse de l"Ancien Testament. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 51. Edited by Maurice Gilbert. Gembloux: Duculot, 1976. [ Links ]

Mazzinghi, Luca. " Ho Cercato e Ho Esplorato" : Studi Sul Qohelet. 2nd ed. CBi 3. Bologna: EDB, 2009. [ Links ]

Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1970. [ Links ]

Mensah, Michael K. I Turned Back My Feet to Your Decrees (Psalm 119, 59): Torah in the Fifth Book of the Psalter. Österreichische Biblische Studien 45. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2016. [ Links ]

Meynet, Roland. Rhetorical Analysis: An Introduction to Biblical Rhetoric. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 256. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Miller, Cynthia L. "Translating Biblical Proverbs in African Cultures: Between Form and Meaning." Bible Translator 56/3 (2005): 129-144. [ Links ]

Miller, Patrick D. "Synonymous-Sequential Parallelism in the Psalms." Biblica 60 (1980): 256. [ Links ]

Murphy, Roland E. "Interpretation of Old Testament Wisdom Literature." Interpretation 23/3 (1969): 289-301. [ Links ]

________________. "A Consideration of the Classification, Wisdom Psalms." Pages 456-467 in Studies in Ancient Israelite Wisdom. New York: Ktav, 1976. [ Links ]

________________. The Tree of Life: An Exploration of Biblical Wisdom Literature. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002. [ Links ]

Nocquet, Dany. "Mais Tu Élargiras Mon Coeur: Nouvelle Étude Structurelle Du Psaume 119. " Etudes Théologiques et Religieuses 83/4 (2008): 618-619. [ Links ]

Nwaoru, Emmanuel O. "Image of the Woman of Substance in Proverbs 31:10-31 and African Context." Biblische Notizen 127 (2005): 41-66. [ Links ]

Perdue, Leo. G. Wisdom and Cult: A Critical Analysis of the Views of Cult in the Wisdom Literatures of Israel and the Ancient Near East. Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 30. Missoula: Society of Biblical Literature, 1977. [ Links ]

Raabe, Paul R. Psalm Structures: A Study of Psalms with Refrains. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 104. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990. [ Links ]

Reynolds, Kent A. Torah as Teacher: The Exemplary Torah Student in Psalm 119. Vetus Testamentum Supplements 137. Boston: Brill, 2010. [ Links ]

Robert, André. "Le Psaume CXIX et les Sapientiaux." Revue Biblique 48/1 (1939): 520. [ Links ]

Soll, William M. Psalm 119. Matrix, Form, and Setting. Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 23. Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1991. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry. Old Testament Studies 53. Boston: Brill, 2006. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem A. Psalms. EBC 5. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991. [ Links ]

Watson, Wilfred G.E. Classical Hebrew Poetry. JSOTSS 26. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995. Websites: https://afriprov.org/images/afriprov/books/ewe100proverbs.pdf. [ Links ]

Submitted: 30/03/2021

Peer-reviewed: 30/04/2021

Accepted: 10/05/2021

Michael Kodzo Mensah, Lecturer, Department for the Study of Religions, University of Ghana, Legon. E-mail: mensahmk@yahoo.com. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2959-7969

1 Michael D. Goulder, The Psalms of the Return: Book V, Psalms 107 - 150 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 116.

2 David Noel Freedman and Andrew Welch, "A Review of W.M. Soll, Psalm 119. Matrix, Form, and Setting (CBQMS 23; Washington, DC, Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1991)," CBQ 55 (1993): 776.

3 Bernhard Duhm, Die Psalmen (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1922), 427.

4 Alfons Deissler, Psalm 119 (118) und seine Theologie. Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der anthologischen Stilgattung im Alten Testament (München: K. Zink, 1955), 269.

5 Soll has criticised the approach by Deissler as being "atomistic" in as much as he is unable to show the connection between the individual verses of the psalm. William M. Soll, Psalm 119. Matrix, Form, and Setting (Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1991), 66.

6 Soll, Psalm 119, 110.

7 Freedman and Welch, "Review of W.M. Soll, 776.

8 Pierre Auffret, Mais tu élargiras mon cceur: Nouvelle étude structurelle du Psaume 119 (New York: DeGruyter, 2006), 1-25.

9 Dany Nocquet, " Mais tu élargiras mon coeur: Nouvelle étude structurelle du Psaume 119,", ETR 83/4 (2008): 619.

10 Kent Aaron Reynolds, Torah as Teacher. The Exemplary Torah Student in Psalm 119 (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 102-103.

11 Michael Kodzo Mensah, I Turned Back My Feet to Your Decrees (Psalm 119, 59): Torah in the Fifth Book of the Psalter (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2016), 20 n. 34.

12 Roland Meynet, Rhetorical Analysis: An Introduction to Biblical Rhetoric (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998).

13 In this article, I name the most basic thought unit of this Psalm a "strophe." Cf. Paul R. Raabe, Psalm Structures: A Study of Psalms with Refrains (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1990), 11-13. A combination of strophes which develop a common idea would be referred to as a "stanza." Cf. Wilfred G. E. Watson, Classical Hebrew Poetry (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 160-168. A group of two or more stanzas would be referred to as a "canto." Cf. Pieter Van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry (Boston: Brill, 2006), 75-92.

14 Mensah, I Turned Back, 118.

15 The Tg in v. 59a reads חשׁיבית לאוטבא אורחי, "I thought to make good my way," suggesting that the Psalmist plans to make good or make pleasing (לאוטבא) his way. The reading demonstrates an attempt to clarify the MT reading.

16 The position that the Psalmist is an epitome of perfection has been retained by most modern commentators of the psalm, with Briggs arguing that the Psalmist is unconscious of any violation of the Torah. Alonso Schökel also suggests that whatever conversion the Psalmist is referring to is without a previous straying or estrangement from the Torah. Luis Alonso Schökel and Cecilia Carniti, Salmos: Traducción, Introducciones y Comentario (Estella: Verbo Divino, 1993), 1454; Charles A. Briggs and Emile G. Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1976), 426.

17 Mensah, I Turned Back, 145.

18 Ibid., 230.

19 Ibid., 232.

20 Ibid., 256-257.

21 Ibid., 257.

22 Mensah, I Turned Back, 275.

23 These include the terms מד , צדק , ישר , זקנים , בין , עצה , ירא , ידע , דרך , לב , ריב and תם. Cf. Leo G. Perdue, Wisdom and Cult: A Critical Analysis of the Views of Cult in the Wisdom Literatures of Israel and the Ancient Near East (SBLDS 30; Missoula: SBL, 1977), 303. For a similar list which Deissler compiles, cf. Deissler, Psalm 119, 72-74. For Robert's discussion of wisdom elements in the Psalm, cf. André Robert, "Le Psaume CXIX et les sapientiaux," RB 48/1 (1939): 5-20.

24 Roland E. Murphy, "A Consideration of the Classification, "Wisdom Psalms," in Studies in Ancient Israelite Wisdom (New York: Ktav, 1976), 464.

25 Roland E. Murphy, The Tree of Life: An Exploration of Biblical Wisdom Literature (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 232.

26 Jos Luyten, "Psalm 73 and Wisdom," in La Sagesse de VAncien Testament (ed. Maurice Gilbert; Grembloux: Duculot, 1979), 64.

27 Murphy, Tree of Life, 232.

28 James L. Crenshaw, "In Search of Divine Presence: Some Remarks Preliminary to a Theology of Wisdom," Review and Expositor 74/3 (1977): 353.

29 Murphy, Tree of Life, 15.

30 Ibid., 34.

31 Derek Kidner, The Wisdom of Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1985), 57.

32 Roland E. Murphy, "Interpretation of Old Testament Wisdom Literature," Interpretation 23/3 (1969): 299.

33 Nicoletta Gatti and George Ossom-Batsa, Journeying with the Old Testament (Bern: Peter Lang, 2011), 147.

34 Carole R. Fontaine, "Wisdom Traditions in the Hebrew Bible," Dialogue 33/1 (2000): 114.

35 Fontaine, "Wisdom Traditions," 112.

36 Murphy, Tree of Life, 17.

37 Luyten, "La Sagesse," 71.

38 Cf. Willem A. VanGemeren, Psalms (Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 1991), 753.

39 Duhm, Die Psalmen, 422, to the contrary, has suggested a textual emendation to readאהבי (friends) instead of איבי (enemies), a position I will subsequently argue against.

40 Jon D. Levenson, "The Sources of Torah: Psalm 119 and the Modes of Revelation in Second Temple Judaism," in Ancient Israelite Religion: FS F. M. Cross (ed. Patrick D. Miller et al.; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), 566.

41 Cf. Alexander F. Kirkpatrick, ed., The Book of Psalms, with Introduction and Notes (XC-CL) (CBSC; Cambridge: University Press, 1901), 721.

42 Patrick D. Miller, "Synonymous-Sequential Parallelism in the Psalms," Biblica 60 (1980): 256.

43 Cf. Mensah, I Turned Back, 199.

44 Michael V. Fox, Proverbs 1-9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 32.

45 Mazzinghi admits that the reading וְיֹתֵר שֶׁׁהָיָה קֹהֶׁלֶׁת (Ecc 12:9) could also be translated as, "since Qohelet was a sage." Luca Mazzinghi, "Ho Cercato e Ho Esplorato": Studi Sul Qohelet (Bologna: EDB, 2009), 318-319.

46 "Il Qohelet non fu un saggio come tutti gli altri... Qohelet fu qualcosa di piu di un normale saggio." Mazzinghi, Ho Cercato, 325-326.

47 Lechion P. Kimilike, "Friedemann W. Golka and African Proverbs on the Poor," ZAW 114/2 (2002): 255-261; Emmanuel O. Nwaoru, "Image of the Woman of Substance in Proverbs 31:10-31 and African Context," Biblische Notizen 127 (2005): 41 -66.

48 John S. Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1970), 39.

49 Dorothy B.E.A. Akoto, "The Book of Proverbs and Its Relationship to African-Ewe Proverbial Communications," Journal of the Interdenominational Theological Center 37/1-2 (2011): 35.

50 Duhm, Die Psalmen, 427.

51 David T. Adamo, "What Is African Biblical Hermeneutics?" Black Theology 13/1 (April 2015): 65.

52 Mensah, I Turned Back, 302.

53 Peggy Appiah, Anthony Appiah and Ivor Agyeman-Duah, Bu Me Be: Proverbs of the Akans (Oxfordshire: Ayebia Clarke, 2007), 50.

54 Ibid., 64.

55 Ibid., 99.

56 See https://afriprov.org/images/afriprov/books/ewe100proverbs.pdf.

57 Appiah, Appiah and Agyeman-Duah, Bu Me Be, 50.

58 Ibid., 59.

59 Ibid., 147.

60 Ibid., 70.

61 Ibid., 147.

62 Ibid., 83.

63 Ibid., 83.

64 Dua-dumfrane nsi kuro-nkwantia, nnane obosompon, nnyegye abetem, mma abotokura nni nnore sradee wo bere ayenwe ne nam. Ibid., 99.

65 Cynthia L. Miller, "Translating Biblical Proverbs in African Cultures: Between Form and Meaning," Bible Translator 56/3 (2005): 129.

66 Katharine J. Dell, "Proverbs 1-9: Issues of Social and Theological Context," Interpretation 63/3 (2009): 230-231.