Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 no.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n1a5

PART I: GENERAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Feasting and Fasting: Hybridity in the Book of Esther

Katherine Gwyther

University of Leeds

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the feasting and fasting scenes that permeate the book of Esther. It examines the interactions between fasting and feasting through a lens of hybridity rather than reversal, as is the predominant approach of Western scholarship. To do so, it links the feasting and fasting to Persian and Jewish activity, respectively. Ultimately, it argues that Purim is an example of hybridity as it combines feasting and fasting in its observance, creating a hybrid of Persian and Jewish activity. The construction of Purim as a hybrid is considered in three sections and it relies on Homi K. Bhabha's postcolonial conception of hybridity: (1) feasting and fasting as Persian and Jewish activity, (2) Esther's mimicry and the beginning of the hybrid and (3) Purim as a hybrid. Understanding Purim as a hybrid, this article concludes by exploring how this hybrid can offer a challenge to the textual presentation of Persian hegemony in the book of Esther.

Keywords: Feasting, Fasting, Hybridity, Esther

A INTRODUCTION

The book of Esther is replete with scenes of both feasting and fasting and, in many ways, these scenes form the narrative framework of the book. The audience's introduction to the Persian court occurs through two banquet scenes where feasting and abundance are the order of the day (Esth 1:5-8).1 The narrative importance of the banqueting and feasting continues in Esth 5-7 when Esther prepares two feasts, which sets the scene for her appeal to King Ahasuerus that the lives of her people be spared. When her request is granted, and Haman is rejected in the royal court and the Jews have "disposed of their enemies" (Esth 9:16), the book culminates in the celebration of Purim (Esth 9:26-32). Scenes of fasting interact with this feasting at significant points in the narrative. The first fasting scene occurs in Esth 4:3 when the Jews are seen collectively weeping and fasting in response to the news of Mordecai's edict. A fast is also taken up by Esther later on in the chapter when Esther calls for all Jews to fast like she and her maids will do (Esth 4:16). Esther's hosting of the feasts in Esth 5-7 appears to be in direct contrast with her declaration of fasting in the previous chapter. This interaction between fasting and feasting continues into Purim which details both the asceticism of fasting and the indulgence of feasting in its observance (Esth 9:18, 32).

However, these interactions between feasting and fasting throughout the book,2 and particularly with regards to Purim, are not well noted in scholarship. The prevailing view, notably in a Western context, is that the book of Esther contains a series of reversals which subvert the status quo; the Jewish orphan rises to the top of the Persian court and the Jews' fasting becomes feasting with the advent of Purim.3

Instead, I argue that the scenes of feasting and fasting, including Purim, demonstrate hybridity. Purim is the final product of this hybridity which unfolds over the feasting and fasting scenes throughout the book of Esther. I link the two seemingly opposing pairs, or at least pairs which are held in tension, to the characterisation of Persian (feasting) and Jewish (fasting) activity in the book of Esther.4 Purim, therefore, is not just a reversal of the status quo where Jews are now indulging in the feasting that they had previously denied, but a hybrid of Persian and Jewish activity as characterised in the book of Esther. To demonstrate this, I draw on Homi K. Bhabha's postcolonial understanding of hybridity and examine the book of Esther in three discrete sections: (1) the distinction between feasting and fasting and how these are constructed within the text as Persian and Jewish activities respectively, (2) Esther's feasts and repeated mimicry in chapters five to seven, and finally (3) the Persian-Jewish/feasting-fasting hybrid of Purim in Esth 9. I also explore how the hybridity of feasting and fasting may be seen as a form of disturbance in the book of Esther, in line with Bhabha's conception of hybridity.5

B HYBRIDITY

Homi K. Bhabha identifies hybridity as the space between fixed identities and cultures (often the space between coloniser and colonised), and he uses it to refer to the creation of a new transcultural being that is created by the process and presence of colonisation.6 Hybridity goes beyond singular and fixed identities within colonial contexts to a hybrid identity that is formed through the processes of negotiation between the colonised and the colonising force.7 This negotiation does not dissolve one identity in order to allow assimilation to another but is founded on the difference between them.8 The creation of this hybrid involves mimicry by repeatedly adopting and reproducing the practices of the coloniser's culture.9 Although in the postcolonial context mimicry is typically used to refer to the imitation carried out by colonised subjects of the normative and dominant culture, the opposite of this-namely where the coloniser adopts some of the cultural practices of the colonised-can occur. Rather than providing a form of resistance within colonial contexts, this form of cultural appropriation may have more negative connotations when the privileged group is able to adopt aspects of the culture of the colonised without facing the marginalised and oppressive experience of being a part of that group. By adopting the practices of the coloniser, the colonised begins to look like them and yet not, and it is on this difference that the hybrid is formed. The attempted mimicry of the colonial force is not a perfect imitation but rather reinforces the difference between the two.10As this process does not involve the dismissal of colonised identity in favour of the coloniser, the hybrid is both a presence of colonial rule and the culture of the colonised. Mimicry, then, is not just a simple repetition of the coloniser's culture but rather a partial presence that combines this culture with their own.11

In identifying as both the coloniser and the colonised, this new hybrid and its mimicry of colonial rule results in the disruption of authority.12 Colonial rule can no longer be known as certain and authoritative, as it has now been disrupted by the hybrid who embodies their practices but is not part of it. The mimicry of colonial practice not only disturbs the rule of the coloniser but also legitimates the colonised and its culture.13 Ultimately, the hybrid unsettles the colonial rule by transforming it into something that is "almost the same, but not quite."14 The mimicry of colonial rule often leads to mockery as the hybrid reflects a parody of this rule; the hybrid does not simply adopt its practices but combines them with their own, creating a distorted image of dominant practice that radically reassesses the authority which is presented as normative and natural.15 At once, the hybrid is both an image of the colonial hegemony and a threat to it.16 In the book of Esther, I argue that this distorted hybrid is Purim.

Bhabha's conception of hybridity is rooted in postcolonial theory. Tsaurayi K. Mapfeka helpfully summarises why the book of Esther is of interest to those conducting postcolonial interpretations:

Esther has readily drawn the attention of postcolonial critics and hermeneutics from the margins, including and not limited to African/Asian, Black and Feminist/Womanist, who have found in Esther a narrative readily available for their suggestive models built against an ethos of resistance.17

These interpretations diverge from the emphasis on reversal that is often predominant in Western scholarship.18 Mapfeka's comment highlights the differing focus taken from those working in postcolonial contexts, for example, where the themes of the biblical story (diasporic identity and belonging, discrimination and power) are interpreted considering the lived experiences of marginalised communities.19 R. S. Sugirtharajah reinforces this notion, commenting that the book of Esther is ripe for postcolonial inquiry given the overt "colonial entrenchment" in its narrative, although he argues that Esther is a paradigm for assimilation in colonial contexts rather than the story of disturbance of authoritative rule that is argued for here.20 Postcolonial interpretations have been particularly fruitful in recent years, with Mapfeka's focus on the diasporic setting of the book21 as well as other important contributions which focus on the subjugated characters of Vashti and the virgin girls of Esth 2.22 This article builds on this scholarship as it reads the feasting and fasting scenes using Bhabha's postcolonial understanding of hybridity in order to argue that in the book of Esther, Purim represents a hybrid of Persian and Jewish activity. As such, Purim acts as a form of disturbance to the textual construction of Persian hegemony.

C FEASTING, FASTING (ESTH 1-4)

The process of constructing the hybrid begins with making distinct the two entities which become blurred in the book of Esther-fasting (the Jewish activity) and feasting (the Persian activity). In the first four chapters of the book, feasting is characterised as a distinctly Persian activity whereas fasting is a symbol of the Jews. On this, David J. A. Clines comments that feasting "has been presented to us as the Persian pastime par excellence [emphasis original]" and that the "Jews on the other hand have only been represented as without food."23This section explores how these opposing presentations of the two groups and their activities are constructed in the first four chapters of Esther. I demonstrate that these distinct presentations start to blur in the following sections.

1 Persian Feasting

The audience's introduction to the Persians in the first chapter is through three feasting scenes. In the first scene, King Ahasuerus throws a feast from his "royal throne" in Susa. This first feast is for all of Ahasuerus' ministers, officials, armies and provincial governors (Esth 1:2-3). The feast is described as lasting for 180 days and is a display of the wealth, decadence and power of the Persians and Persian rule in the text, as the guests' experience "the vast riches of [the Persian] kingdom and the splendid glory of his majesty" (Esth 1:4). Immediately following this scene, a smaller, second feast is held for the people of Susa and this feast lasts for seven days. Though this feast is not for government officials, it is no less extravagant than the first with its "white cotton curtains" (Esth 1:6), "golden goblets" (Esth 1:7) and drinking without restraint (Esth 1:8). Following Ahasuerus' second feast, Queen Vashti also hosts her own feast for the women of the palace (Esth 1:9). In these introductory chapters, the Persians are presented to the audience as those who feast. Feasting is constructed as a distinctly Persian activity as it is only Persian subjects who are described as partaking in these feasts. The first feast is held by Ahasuerus for military, provincial and imperial officials. The second feast hosted by Ahasuerus is for the people of Susa who are presumably Persian subjects. Finally, the third feast in this introduction is given by Vashti and is for the women inside the Persian palace. In these three scenes, there is no indication that these feasts are for anyone who is not Persian. Moreover, Linda Day highlights that these feasts do not just introduce the Persians to the audience as a people who feast but also serve to demonstrate the power of the Persian court through their sheer wealth and decadence.24

Esther 2 maintains this link between the characterisation of being Persian and feasting with Esther's coronation. When Esther wins Ahasuerus' "favour and devotion" (Esth 2:17); she is made queen and replaces Vashti. In order to celebrate this occasion, Ahasuerus hosts a feast for his ministers and officials and calls it "Esther's banquet" (Esth 2:18). Esther is introduced to both the Persian court and the audience in her new role as queen through a feast. The feast acts as a rite of passage and signals that Esther has now moved from her position as one of the virgin girls to the queen. These introductory chapters show that in the book of Esther, to be Persian was to feast.

2 Jewish Fasting

Fasting, on the other hand, is characterised in the book of Esther as a distinctly Jewish activity. Esther 4 is the centre of this characterisation. When Mordecai is informed about Haman's edict to kill the Jews, the Jews and Mordecai are seen fasting, lamenting and mourning: "In every province, wherever the king's command and his decree came, there was great mourning among the Jews, with fasting and weeping and lamenting, and most of them lay in sackcloth and ashes" (Esth 4:3). This report is one of the only accounts that describe the Jews as a people in the book of Esther and they are presented as a people who fast. While fasting, as well as wearing sackcloth and rolling in ashes, is tied to mourning practices in the Hebrew Bible, fasting forms part of the textual characterisation of the Jews in the book of Esther and a characterisation that contrasts the feasting portrayal of the Persians.25 To describe the Jews as fasting directly after constructing Persians as those who feast creates a distinction between the two groups.

This construction of the Jews as a people who fast is compounded in Esth 4:12-17. Here, Mordecai instructs Hathach, a eunuch in the court who acts as an intermediary for the interactions between Mordecai and Esther, to tell Esther about Haman's edict and to take a copy of it to show her (Esth 4:7-8). After a back and forth where Mordecai reminds Esther that she is still a Jew in the Persian court, that she would not be excluded from Haman's edict, and that her position within the court may be for "such a time as this" (Esth 4:13-14), Esther instructs Mordecai to gather all of the Jews (Esth 4:15-16). Once the Jews have been gathered, they are told to hold a fast on Esther's behalf for three nights and days (Esth 4:16). Esther and her maids will also hold this fast while Esther seeks to petition the king (Esth 4:16) and the audience is told that "Mordecai then went away and did everything as Esther had ordered him" (Esth 4:17). When Esther finds out about Haman's plans, she reacts by connecting herself to the wider Jewish people through this communal fast. For Anne-Marieke Wetter, it is through this communal fast that Esther is reunited with her people.26 Moreover, Alice Bach asserts that not only does this fast tie Esther directly to the Jews, but it also serves to differentiate between the two groups in the text, the Jews and the Persians (or Babylonians as Bach refers to them) as the Jews have become distinct from the Persians through their fast.27 While I would contest that this is the first time that the Jews and Persians are made distinct given that feasting has been constructed as an entirely Persian activity in the book of Esther, as demonstrated earlier, Bach's point serves to highlight that fasting is a Jewish activity here. Though the feasting may serve to emphasise the fasting-drawing attention to an act that may have gone unnoticed without such a foil and one which is perhaps the only signal to the hidden religiosity in the book-this distinction also forms an important way in which these two groups are understood in the book. Therefore, in the context of the book of Esther, the Jews are presented as a group of people who fast, and this presentation stands in tension with the Persian activity of feasting.

This section has demonstrated that these ideas of feasting and fasting as connected to the Persians and the Jews respectively have so far remained separate from each other, both in the narrative sections but also by those participating in these activities. The feasts in the introductory chapters appear to be exclusively Persian whereas only the Jews are described as fasting. The following section explores how the boundaries between Jewish and Persian and between fasting and feasting start to blur with the beginning of the formation of Bhabha's hybrid.

D TWO FEASTS (ESTH 5-7)

The feasting and fasting motifs continue into Esth 5-7. However, unlike the previous chapters where feasting and fasting are kept distinct, in these chapters, they begin to blur and the hybrid starts to appear. This blurring of boundaries between feasting and fasting first occurs with the Jewish mimicry of the Persians, that is, where Esther deliberately imitates the language and behaviour of the Persians for the gain of the Jews. Esther participates in mimicry rather than mere repetition, as what results from the imitation here is a partial Persian presence.28It is a partial presence because, as we will see, Esther does not commit to a full imitation of the Persians, namely Ahasuerus and Haman. Instead, her imitation is designed to fail from the outset when she retains her connection to the Jews throughout. Chiefly, this mimicry happens in Esth 5-7 with Esther's imitation of Ahasuerus and Haman's language and her acting as host to two feasts. In this section, informed by Bhabha's conceptualisation of hybridity, I argue that it is through this mimicry of the Persians that a hybrid begins to form.

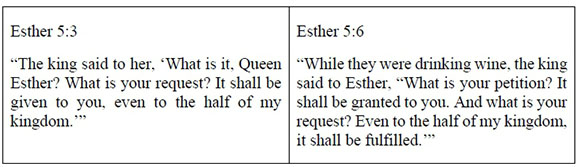

Continuing from Esther's promise to petition Ahasuerus in Esth 4:16, Esth 5 opens with Esther preparing a feast for Ahasuerus. Esther first wins Ahasuerus' favour, prompting him to promise any request that she would make of him (Esth 5:3) before inviting him and Haman to the feast (Esth 5:4). Once they have all arrived at the feast, Ahasuerus repeats his promise to Esther from verse 3 that he will grant any request that she makes of him in a near verbatim utterance in verse 6.

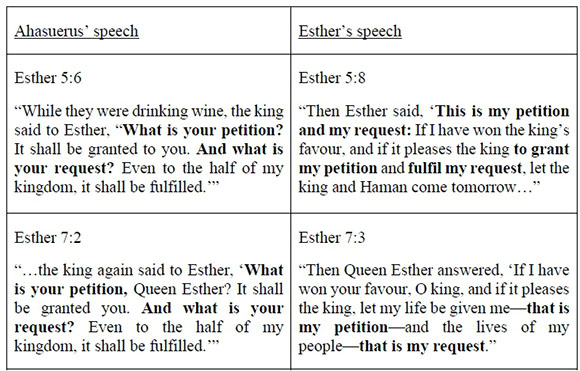

In response to Ahasuerus' question, Esther phrases her answer with this same carefully chosen language, "If I have won the king's favour, and if it pleases the king to grant my petition and fulfil my request" (Esth 5:8), inviting both Ahasuerus and Haman to come back the next day for another feast when she will answer the king's question. There is then an interruption in the continuation of Esther's hosting duties where Haman builds his gallows and Mordecai is honoured by the king in Esth 6. Once the narrative returns to Esther's feast (Esth 7:1), Ahasuerus again repeats his question (Esth 7:2) and again it is almost a word-for-word repetition of the question in both Esth 5:3 and 5:6. When Esther finally answers Ahasuerus with her petition asking him to save her life and the lives of the Jews, she states that "that is my petition... that is my request" (Esth 7:3). The similarities between Esther's answer and Ahasuerus' repeated question are clear at both feasts.

This resemblance between Ahasuerus' questions and Esther's replies has been noticed by Timothy K. Beal who argues that there is a parallel structure between the two.29 Esther's speech is rhetorically tied to Ahasuerus' as they both follow the structure of asking ("What is your petition?"/ "This is my petition") and seeking ("what is your request?"/ "that is my request").30 Beal also notes that both Ahasuerus' questions and Esther's replies follow the formula of moving from the personal to the political. Ahasuerus begins with a direct address to Esther forming the personal before then moving to the political with his reference to his kingdom.31 Esther also mirrors this structure in her reply; she is personal in her petition that her life be spared but then she transitions to the political with her broader request for the lives of her people.32 Esther's responses closely mimic Ahasuerus throughout both of the feasts that she hosts.

Esther's mimicry is not just of Ahasuerus but of Haman too. After Esther states her petition and request, she tells Ahasuerus that she is making the request because she and the Jews have been threatened "to be destroyed, to be killed, and to be annihilated" (Esth 7:4) by Haman. Esther's phrasing here of "destroyed," "killed" and "annihilated" is a direct reference to Haman's original edict in Esth 3:12 when he gives orders "to destroy, to kill, and to annihilate all Jews." Here, Esther is directly calling on the words of Haman, a court official, and using them for her own gain. At both these feasts, Esther is mimicking the Persians. Esther's mimicry does not just include language but also her actions in hosting a feast which, as demonstrated above, has been constructed as an activity that is performed by and participated in by Persians. Esther organises these feasts in order to petition the king on behalf of the Jews. However, Esther herself does not appear to be partaking in the festivities. Haman and Ahasuerus are both seen to be drinking and enjoying the wine, Esther's participation is not noted (Esth 5:5; 7:2).33 It appears then that Esther is not only mimicking Persian practice but is choosing to maintain her commitment to the Jews and to her fast.34 This mimesis-where the victim imitates the perpetrator-in the book of Esther has also been drawn out by Gerrie Snyman.35 By the end of the story, Snyman argues that the Jews have done to the Persians what has been done to them which is best shown through the comparison of Haman's decree in Esth 3 to Mordecai's decree in Esth 8.36 Although he does not comment on Esther's repetition of Ahasuerus' language, Snyman highlights how Esther, Mordecai and the Jews use the tools of the oppressor in the narrative for their own gain.37

Returning to Bhabha's postcolonial understanding of hybridity, Esther's repeated adoption and reproduction of Persian activity-through language and playing host to feasting-begins to destabilise the Persian hegemony and culture in the book of Esther which breaks down even further with the advent of Purim where the boundaries between feasting and fasting collapse into a celebration which requires both in its observance.38 Esther's actions in these chapters allow a clearer picture of how hybridity is being constructed in the book and her imitation of Persian language is always a partial presence, a mimicry (in the Bhabhian sense), as she never relinquishes her commitment to the Jews and her fast during this imitation. Rather, she is engaging in both simultaneously. In doing so, Esther appears to create a parody of Persian rule when she takes on their practices for a particular purpose (survival) without fully assimilating. What results from this purposeful adoption is a ridiculous, and perhaps satirical, image that is "almost the same, but not quite."39

E PURIM: FEASTING AND FASTING (ESTH 9)

With the announcement of Purim in Esth 9, the hybrid figure emerges. At the beginning of the book of Esther, feasting is described as an activity for Persians whereas fasting is constructed as an activity for Jews. In Esther's feasts, these two activities begin to blur when Esther performs feasting in her hosting actions but does not participate in these feasts, instead maintains her fast. Esther's mimicry of Persian feasting while also participating in the Jewish fast starts to create an unusual merging of these two activities. These chapters also demonstrate Esther's mimicry of Persian language where she directly draws upon the words of Ahasuerus and Haman to formulate her petition for the lives of the Jews. In Purim, feasting and fasting are brought together in one practice and both are required for proper observance.

For Bhabha, a hybrid is the presence of the culture of both the colonised and the coloniser that have been brought together through a series of mimicry and the repeated adoption and adaption of this colonising culture.40 By bringing together feasting-Persian cultural activity and arguably the image of the coloniser in the book of Esther-and fasting-a Jewish activity, Purim is a hybrid, as it is the presence of both Persian and Jewish activity. That Purim requires both feasting and fasting in its observance is explicitly set out at the end of Esth 9 when Esther lays down the regulations and ordinances for the practice. When Purim is announced, it is to be two consecutive days of "feasting and gladness" (Esth 9:18-22) that are to be kept throughout the provinces and across generations (Esth 9:28). However, it is not just a festival of feasting and gladness but also one of fasting. When Esther writes to inform the provinces of this celebration, she also details the practices of Purim. Purim, alongside the feasting and general revelry specified above, is to include fasting and lamentation and "Queen Esther fixed these practices of Purim, and it was recorded in writing" (Esth 9:31-32). That Purim requires both feasting and fasting as its constituent parts has been noted in scholarship, although it has been overshadowed by claims of Purim as carnivalesque and/or role reversal. For example, both Suzanne Plietzsch and David Resnick draw attention to the fact that fasting is a central feature of Purim alongside the feasting.41 In doing so, Plietzsch and Resnick demonstrate that it is not either feasting or fasting which comprise Purim but the practice of both of these activities. A useful parallel can be drawn here to the Joseph narrative in Gen 37-50. Hyun Chul Paul Kim argues that in Gen 37-50, Joseph is characterised as having a hybrid identity; Joseph is both an Egyptian and a Hebrew, a "Hebrew-Egyptian."42 Throughout the narrative in these chapters, Joseph is seen as a Hebrew through his identification with his brothers ("I am your brother," Gen 45:5) as well as his practices of faith in Yahweh and forgiveness (Gen 50:20-21).43 At the same time, Joseph is also seen as Egyptian as he frequently acts on the behalf of Egypt as a vizier and not always with positive outcomes; it is his loan system that results in the enslavement of the people (Gen 47:21-25).44 Joseph as the Hebrew-Egyptian hybrid has similarities with Purim in the book of Esther. Joseph is not solely Hebrew as he is seen acting for the benefit of Egypt, but at the same time, he is not Egyptian because of the relational ties he maintains with the Hebrews. Rather, as Kim argues, Joseph is a hybrid. Similarly, Purim is not just a festival of feasting as it requires fasting in its practice, it is instead a hybrid of feasting and fasting and as such it brings together Persian and Jewish activity.45

However, as noted in the introduction to this article and this section, most of the scholarship (particularly from a Western perspective) does not emphasise the fasting element of Purim and instead focuses on the features of reversal. Both Jonathan Grossman and Susan Niditch cite Purim as an example of festivals like Bacchanalia or Saturnalia where the status quo is subverted.46 Kenneth Craig also affirms that Purim is a festival which subverts the status quo in his study of Esther through the lens of the literary carnivalesque.47 Moreover, Joshua Joel Spoelstra notes that the Jews celebrate Purim in a similar way to how Ahasuerus celebrates in the first few chapters of the book of Esther, arguing that the Jewish fasting has given way to feasting.48 Nonetheless, in concentrating only on the elements which seemingly reverse the expected assumptions that have been built into the text, like the Jews fasting which has now become feasting, these scholars overlook the point that Purim observance does not only require the feasting but the fasting too. By understanding Purim as a hybrid of feasting and fasting and of Persian and Jewish activity, I account for all constituent parts of Purim.

Moreover, by understanding Purim as a hybrid, according to Bhabha's postcolonial conceptualisation, we might conceive this hybrid as a form of disturbance against the assumed Persian hegemonic power in the book of Esther. The next section explores how the blurring of the lines between the established boundaries of feasting and fasting, of Persian and Jewish activities can reassess the authoritative power in the book of Esther.

F PURIM AS DISTURBANCE IN THE BOOK OF ESTHER

The hybrid, in its dual presence, forces the reassessment of the ways in which authoritative power is presented as natural and normative.49 This is because the hybrid is at once a representation of this power and a threat to it as it is "almost but not quite the same."50 In its incorporation of both the dominant and subaltern cultures, the hybrid disturbs the presentation of that culture as normative and static. If the ruling power is predominantly characterised in one way and their power becomes known through this characterisation, any change in this presentation can disturb the basis of the ruling authority. The hybrid distorts this presentation, and subsequently authority, as it is not just the dominant culture that can be identified by a certain practice or presentation but the subaltern as well.

In the book of Esther, feasting is presented as the activity of the Persians and it is only ever the Persians who are seen fully engaging with feasting activities throughout. Esther's hosting duties cannot be categorised as full engagement as, unlike Ahasuerus and Haman, she is not shown to be an active participant in the feasting itself. The Persians are not only constructed as the group which feasts in the book of Esther. Jews, as this article has already demonstrated, are constructed in tension to this as those who fast. However, with the institution of Purim, these boundaries between Persian and Jewish activity have changed. It is not only the Persians who can be identified as feasting, the Jews can too, as feasting becomes part of Purim practices. The Persians' claim to feasting as a core part of their textual presentation has been upset. Purim, therefore, in its hybridity, has offered a distortion to the assumed dynamics with feasting for the Persians and fasting for Jews. In doing so, Purim acts as a form of disturbance to Persian activity and presentation and, as a result, to the hegemonic structures within the text.

G CONCLUSION

This article has focused on understanding Purim as a hybrid. I have demonstrated this using the work of Bhabha and his postcolonial conceptualisation of hybridity before moving to examine how the book of Esther constructs this hybrid in three parts: (1) feasting and fasting as Persian and Jewish activity, respectively, (2) Esther's mimicry and the beginning of the hybrid, and (3) Purim as a hybrid. This article concludes with the argument that Purim can not only be understood as a hybrid construction but that as a hybrid construction, it offers a form of disturbance to the assumed dynamics in the book of Esther. Subsequently, in arguing for Purim as a hybrid, I have challenged the claims of reversal regarding Purim which overlook that fasting is as much a constituent part of Purim practice as feasting is. Further research on the book of Esther may also focus on the other potential elements of hybridity, such as Esther's name, the use of clothing, and gendered performances throughout the book. While they have fallen beyond the scope of discussion here, they present interesting and fruitful areas for future research which support the evident theme of hybridity in the book of Esther.

H BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bach, Alice. Women, Seduction, and Betrayal in Biblical Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Beal, Timothy K. "Aftermath: Esther 9:1-10:3." Pages 107-118 in Ruth and Esther. Edited by Tod Linafelt and Timothy K. Beal. Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1999. [ Links ]

________ . "Coming out Party: Esther 7:1 -10." Pages 87-95 in Ruth and Esther. Edited by Tod Linafelt and Timothy K. Beal. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Berg, Sandra Beth. The Book of Esther: Motifs, Themes and Structures. Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 44. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1979. [ Links ]

Berger, Yitzhak. "Esther and Benjaminite Royalty: A Study in Inner-Biblical Allusion." Journal of Biblical Literature 129 (2010): 625-644, 637. [ Links ]

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. A. "Reading Esther from Left to Right: Contemporary Strategies for Reading a Biblical Text." Pages 31-52 in The Bible in Three Dimensions: Essays in Celebration of Forty Years of Biblical Studies in the University of Sheffield. Edited by David J. A. Clines, Stephen E. Fowl and Stanley E. Porter. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 87. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990. [ Links ]

________. The Esther Scroll: The Story of the Story. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 30. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1984. [ Links ]

Craig, Kenneth. Reading Esther: A Case for the Literary Carnivalesque. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1995. [ Links ]

Day, Linda. "Power, Otherness and Gender in the Biblical Short Stories." Horizons in Biblical Theology 20 (1998): 109-127. [ Links ]

Dunbar, Ericka S. "For Such a Time as This? #UsToo: Representations of Sexual Trafficking, Collective Trauma, and Horror in the Book of Esther." The Bible and Critical Theory 15 (2019): 29-48. [ Links ]

Firth, David G. "The Book of Esther: A Neglected Paradigm for Dealing with the State." Old Testament Essays 10 (1997): 18-26. [ Links ]

Fox, Michael V. Character and Ideology in the Book of Esther. Colombia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Grossman, Jonathan. Esther: The Outer Narrative and the Hidden Meaning. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2011. [ Links ]

Hatzaw, Ciin Sian Siam. "Reading Esther as a Postcolonial Feminist Icon for Asian Women in Diaspora." Open Theology 7 (2021): 1-34. [ Links ]

Hertig, Young Lee. "Subversive Banquets of Vashti and Esther." Pages 15-29 in Mirrored Reflections: Reframing Biblical Characters. Edited by Young Lee Hertig and Chloe Sun. Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2010. [ Links ]

Jackson, Melissa A. Comedy and Feminist Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible: A Subversive Collection. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [ Links ]

Kim, Hyun Chul Paul. "Reading the Joseph Story (Genesis 37-50) as a Diaspora Narrative." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 75 (2013): 219-238. [ Links ]

Kuan, Jeffrey Kah-Jin. "Diasporic Readings of a Diasporic Text: Identity Politics and Race Relations and the Book of Esther." Pages 161-173 in Interpreting Beyond Borders. Edited by Fernando S. Segovia. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. [ Links ]

LaCocque, André. Esther Regina: A Bakhtinian Reading. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2008. [ Links ]

________. The Feminine Unconventional: Four Subversive Figures in Israel's Tradition. Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2006. [ Links ]

Levenson, Jon D. Esther. Old Testament Library. London: SCM Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Mapfeka, Tsaurayi K. "Esther 9 through the Lens of Diaspora: The Exegetical and Ethical Dilemmas of the Massacres in Susa and Beyond. Pages 397-414 in Violence in the Hebrew Bible: Between Text and Reception. Edited by Jacques van Ruiten and Koert van Bekkum. Old Testament Studies 79. Leiden: Brill, 2020. [ Links ]

________. Esther in Diaspora: Toward an Alternative Interpretive Framework. Biblical Interpretation Series 178. Leiden: Brill, 2019. [ Links ]

________. "Empire and Identity Secrecy: A Postcolonial Reflection on Esther 2:10." Pages 79-96 in The Bible, Centres and Margins: Dialogues Between Postcolonial African and British Biblical Scholars. Edited by Johanna Stiebert and Musa W. Dube. London: T & T Clark, 2018. [ Links ]

Masenya (ngwana' Mphahlele), Madipoane. "Their Hermeneutics Was Strange! Ours Is a Necessity! Rereading Vashti as African South-African Women." Pages 179-194 in Her Master's Tools? Feminist and Postcolonial Engagements of Historical-Critical Discourse. Edited by Caroline Vander Stichele and Todd Penner. GPBS 9. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005. [ Links ]

Mosala, Itumeleng J. "The Implications of the Text of Esther for African Women's Struggle for Liberation in South Africa." Pages 134-141 in The Postcolonial Bible Reader. Edited by Raisah S. Sugirtharajah. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2006. [ Links ]

Niditch, Susan. "Interpreting Esther: Categories, Contexts and Creative Ambiguities." Pages 255-274 in The Writings and Later Wisdom Books. Edited by Nuria Benages-Calduch and Christl M. Maier. BW. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2014. [ Links ]

Plietzsch, Suzanne, "Eating and Living: The Banquets in the Esther Narratives." Pages 27-41 in Decisive Meals: Table Politics in Biblical Literature. Edited by Kathy Ehrensperger, Nathan MacDonald and Luzia Sutter Rehmann. Library of New Testament Studies 449. New York: T & T Clark, 2012. [ Links ]

Resnick, David. "Esther's Bulimia: Diet, Didactics, and Purim Paideia." Poetics Today 15 (1994): 75-88. [ Links ]

Seidler, Ayelet. ""Fasting," "Sackcloth," and "Ashes": From Nineveh to Sushan."" Vetus Testamentum 69 (2019): 117-134. [ Links ]

Snyman, Gerrie. "Esther and African Biblical Hermeneutics: A Decolonial Inquiry." Old Testament Essays 27 (2014): 1035-1061. [ Links ]

________. "The African and Western Hermeneutics Debate: Mimesis, The Book of Esther, and Textuality." Old Testament Essays 25 (2021): 657-684. [ Links ]

Spoelstra, Joshua Joel. "Surviving the Agagites: A Postcolonial Reading of Esther 89." Old Testament Essays 28 (2015): 168-181. [ Links ]

________. "The Function of the משתה ייו in the Book of Esther." Old Testament Essays 27 (2014): 285-301. [ Links ]

Sugirtharajah, R. S. The Bible and the Third World: Pre-colonial, Colonial, and Postcolonial Encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Wetter, Anne-Marieke. "In Unexpected Places: Ritual and Religious Belonging in the Book of Esther." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36 (2012): 321-332. [ Links ]

Submitted: 17/12/2020

Peer-reviewed: 06/05/2021

Accepted: 12/05/2021

Katherine Gwyther, School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science, University of Leeds. Email: prkag@leeds.ac.uk. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9908-6638.

1 All references to the book of Esther are from the NRSV translation of the Masoretic Text.

2 David J. A. Clines, "Reading Esther from Left to Right," in The Bible in Three Dimensions: Essays in Celebration of Forty Years of Biblical Studies in the University of Sheffield (ed. David J. A. Clines, Stephen E. Fowl and Stanley E. Porter; JSOTSup 87; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 31-52, 37-40. Clines notes three codes that persist throughout the book of Esther-alimentary, clothing and topographical. In contrast to most scholarship, his discussion of the alimentary code-that is the references to nourishment throughout the book-highlights the interaction between the two contrasting ideas of feasting and fasting throughout the book. For Clines, these codes "signal the narrative's concern with power, where it is located, and whether and how it can be withstood or manipulated by others" (40). Clines, therefore, also recognises the significance of the interaction between feasting and fasting in the narrative of Esther.

3 Those scholars who recognise the theme of reversal in the book of Esther include André LaCocque, Esther Regina: A Bakhtinian Reading (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2008), 85; Susan Niditch, "Interpreting Esther: Categories, Contexts and Creative Ambiguities," in The Writings and Later Wisdom Books (ed. Nuria Benages-Calduch and Christl M. Maier; BW; Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature, 2014), 255; Jon D. Levenson, Esther (London: SCM Press, 1997), 6; Jonathan Grossman, Esther: The Outer Narrative and the Hidden Meaning (Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2011), 13; Michael V. Fox, Character and Ideology in the Book of Esther (Colombia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991), 292; Yitzhak Berger, "Esther and Benjaminite Royalty: A Study in Inner-Biblical Allusion," JBL 129 (2010): 637; Kenneth Craig, Reading Esther: A Case for the Literary Carnivalesque (Kentucky: Westminster John Knox, 1995), 32; Timothy K. Beal, "Aftermath: Esther 9:1-10:3," in Ruth and Esther (ed. Tod Linafelt and Timothy K. Beal; Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1999), 109-112; André LaCocque, The Feminine Unconventional: Four Subversive Figures in Israel's Tradition (Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 55; Sandra Beth Berg, The Book of Esther: Motifs, Themes and Structures (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1979), 34; Melissa A. Jackson, Comedy and Feminist Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible: A Subversive Collaboration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 206. Fasting that gives way to feasting at Purim is just one element of reversal that is highlighted by these scholars who generally note that what has been set up as the course of events at the beginning of the book is reversed at the end. Some note that there is an obvious reversal of political power, as a Jewish queen has now risen to the top of the Persian court and the Jews' position as a powerless group at the beginning of the narrative has now given way to them as an intimidating one. See Berg, The Book of Esther; Beal, "Aftermath: Esther 9:1-10:3"; and Niditch, "Interpreting Esther". Others, as will be mentioned in later discussion, focus on Purim as a paradigm for the themes of reversal send throughout the book of Esther (for example, Grossman, Esther).

4 I am not making a claim here that Jews and being Jewish are solely linked to fasting practices in the Hebrew Bible. To do so would be to ignore the plethora of texts which link feasting to integral narratives in the Hebrew Bible. Instead, I am making a claim about the characterisation of Persians and Jews in the book of Esther which appears, in part, to be tied to either their participating in feasting (Persians) or fasting (Jews).

5 A final note, this article only examines hybridity in reference to feasting and fasting in the book of Esther. It does not explore the other ways in which hybrid constructions occur in the text, particularly, through the use and mimicry of clothing, performances of gender and Esther's name. While these are rich areas for discussion, they fall outside the scope of this article and are not considered here. Clines, "Reading Esther from Left to Right," 38-39, has already begun to consider how clothing is used in this way and how clothing is used in the narrative to signal changes in identity and power.

6 Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 4.

7 Ibid., 112.

8 Ibid., 71.

9 Ibid., 122.

10 Ibid., 111.

11 Ibid., 123.

12 Ibid., 112.

13 Ibid., 126.

14 Ibid., 122.

15 Bhabha, Location of Culture, 123, 130.

16 Ibid., 123.

17 Tsaurayi K. Mapfeka, Esther in Diaspora: Toward an Alternative Interpretive Framework (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 31.

18 Gerrie Snyman, "The African and Western Hermeneutics Debate: Mimesis, The Book of Esther, and Textuality," OTE 25 (2012): 657-684. Snyman offers an expanded discussion of the "Western ethnocentrism" (672) that produces such focal points as these in scholarship on the book of Esther, as well as an evaluative commentary on the relationship between African and Western biblical interpretation.

19 See, for example, Jeffrey Kah-Jin Kuan, "Diasporic Readings of a Diasporic Text: Identity Politics and Race Relations and the Book of Esther," in Interpreting Beyond Borders (ed. Fernando F. Segovia; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), 161173; Ciin Sian Siam Hatzaw, "Reading Esther as a Postcolonial Feminist Icon for Asian Women in Diaspora," Open Theology 7 (2021): 1-34; and Young Lee Hertig, "Subversive Banquets of Vashti and Esther," in Mirrored Reflections: Reframing Biblical Characters (ed. Young Lee Hertig and Chloe Sun; Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2010), 15-29.

20 R. S. Sugirtharajah, The Bible and the Third World: Pre-colonial, Colonial, and Postcolonial Encounters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 251.

21 Mapfeka, Esther in Diaspora; Tsaurayi K. Mapfeka, "Esther 9 through the Lens of Diaspora: The Exegetical and Ethical Dilemmas of the Massacres in Susa and Beyond," in Violence in the Hebrew Bible: Between Text and Reception (ed. Jacques van Ruiten and Koert van Bekkum; Leiden: Brill, 2020), 397-414. Additional interpretations which focus on diaspora and Esther, particularly, from an Asian context, include Hatzaw, "Reading Esther" and Kuan, "Diasporic Readings."

22 For examples of postcolonial readings that focus on the characters of the virgin girls and Vashti, see Madipoane Masenya (ngwana' Mphahlele), "Their Hermeneutics Was Strange! Ours Is a Necessity! Rereading Vashti as African South-African Women," in Her Master's Tools? Feminist and Postcolonial Engagements of Historical-Critical Discourse (ed. Caroline Vander Stichele and Todd Penner; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005), 179-194; Ericka S. Dunbar, "For Such a Time as This? #UsToo: Representations of Sexual Trafficking, Collective Trauma, and Horror in the Book of Esther," The Bible and Critical Theory 15 (2019): 29-48; Itumeleng J. Mosala "The Implications of the Text of Esther for African Women's Struggle for Liberation in South Africa," in The Postcolonial Biblical Reader (ed. Rasiah S. Sugirtharajah; Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 134-141; and Tsaurayi K. Mapfeka, "Empire and Identity Secrecy: A Postcolonial Reflection on Esther 2:10," in The Bible, Centres and Margins: Dialogues between Postcolonial African and British Biblical Scholars (ed. Johanna Stiebert and Musa W. Dube; London: T & T Clark, 2018), 7996. Other postcolonial readings of the book of Esther include Spoelstra's offering of postcolonial reading of Esth 8-9 where he argues that the authors of Esther drew on the Deuteronomistic History when describing the war against the Agagites; Joshua Joel Spoelstra, "Surviving the Agagites: A Postcolonial Reading of Esther 8-9," OTE 28 (2015): 168-181. Snyman also offers a related decolonial critique of the book of Esther which aims to deconstruct the role of Haman as a perpetrator as well as relate the text to similarities in the context of post-apartheid context of race trouble; Gerrie Snyman, "Esther and African Biblical Hermeneutics: A Decolonial Inquiry," OTE 27 (2014): 1035-1061. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of postcolonial interpretations of the book of Esther but it highlights some recent examples in the field.

23 David J. A. Clines, The Esther Scroll: The Story of the Story (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1984), 36.

24 Linda Day, "Power, Otherness and Gender in the Biblical Short Stories," HBT 20 (1998): 112.

25 André LaCocque, Esther Regina, 83; Ayelet Seidler, ""Fasting," "Sackcloth," and "Ashes": From Nineveh to Sushan," VT 69 (2019): 118-119. Biblical examples of fasting as part of mourning can be found in 1 Sam 31:13 in mourning the death of Saul, and in Jdt 8:3-6 where Judith fasts in mourning for her husband.

26 Anne-Marieke Wetter, "In Unexpected Places: Ritual and Religious Belonging in the Book of Esther," JSOT36 (2012): 330.

27 Alice Bach, Women, Seduction, and Betrayal in Biblical Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 197.

28 Bhabha, Location of Culture, 123.

29 Timothy K. Beal, "Coming out Party: Esther 7:1-10," in Ruth and Esther (ed. Tod Linafelt and Timothy K. Beal; Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1999), 87-95, 89.

30 Ibid., 89.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 It is worth noting that in the Greek additions to the book of Esther, it is explicitly stated that Esther did not participate in the feasts and kept her fast. According to the Greek text, Esther "has not eaten at Haman's table, and [she has] not honoured the king's feast or drunk the wine of libations" (Add. Esth C 14:17).

34 David G. Firth, "The Book of Esther: A Neglected Paradigm for Dealing with the State ," OTE 10 (1997): 23.

35 Snyman, "Mimesis, The Book of Esther, and Textuality," 681.

36 Ibid., 662-663.

37 Ibid., 668.

38 Bhabha, Location of Culture, 122.

39 Ibid.

40 Bhabha, Location of Culture, 122.

41 Suzanne Plietzsch, "Eating and Living: The Banquets in the Esther Narratives," in Decisive Meals: Table Politics in Biblical Literature (ed. K. Ehrensperger, N. MacDonald and L. Sutter Redman; New York: T & T Clark, 2012), 31; David Resnick, "Esther's Bulimia: Diet, Didactics, and Purim Paideia," Poetics Today 15 (1994): 76-77.

42 Hyun Chul Paul Kim, "Reading the Joseph Story (Genesis 37-50) as a Diaspora Narrative," CBQ 75 (2013): 220, 238.

43 Ibid., 225, 229.

44 Kim, "Reading the Joseph Story," 226.

45 Adding weight to the understanding of Purim as a hybrid, André LaCocque even describes the name "Purim" as a linguistic hybrid as it is constructed of a Hebrew transliteration of an Assyrian word (purum) that has also been given a Hebrew ending. LaCocque describes the name as a "Hebraization of a foreign vocable." (The Feminine Unconventional: Four Subversive Figures in Israel's Tradition (Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 64).

46 Grossman, Esther, 13-14; Niditch, "Interpreting Esther," 271.

47 Craig, Reading Esther, 166.

48 Joshua Joel Spoelstra, "The Function of the משתה ייו in the Book of Esther," OTE 27 (2014): 299.

49 Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 123, 130.

50 Ibid., 122-126.