Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.34 n.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2021/v34n1a4

PART I: GENERAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Edomite Defectors among the Israelites: Evidence from Psalm 124

Nissim Amzallag

The Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva

ABSTRACT

The present analysis of Ps 124 suggests that it relates the retreat to Israel of a foreign group of YHWH's worshipers. Its Edomite identity emerges from its comparison with other Songs of Ascents (especially Pss 120, 122 and 129) and the Adam appellation of their land of origin (v. 2). The setting of Ps 124 in complex antiphony provides further details concerning their fleeing from Edom, their new commitment to Israel, and their Edomite brothers' angry reaction. These events corroborate other biblical sources aiming for the integration of a group of Edomite poets and singers in the Jerusalem temple at the early Persian period. The consequences concerning the nature of the corpus of Songs of Ascents are discussed.

Keywords: Songs of Ascents, Ezrahite singers, complex antiphony, non-Israelite Yahwism, Second Temple theology

A INTRODUCTION

Psalm 124 is generally approached as a song in a good state of conservation.1The content is considered explicit enough and scholars rarely dispute its genre, identified as a communal song of thanksgiving for liturgy and festivals.2 This global consensus might explain why this song does not receive any special attention in modern research.3 Psalm 124 is only briefly mentioned in works devoted to the corpus of Ascents (Pss 120-134) and interpreted in agreement with the general considerations concerning it.4 Its contribution to clarifying the nature, origin and significance of this whole corpus is minimal also.

The Songs of Ascents are traditionally approached as Zion songs composed for the celebration of religious festivals in the reconstructed temple of Jerusalem.5 Their function as pilgrim songs was deduced from their heading, 'Songs of Ascents'6 and from the mention of people residing in far countries in the first song (Ps 120) and standing in the courtyard of the temple in the last one (Ps 134).7 It is why Ps 124 is approached by most scholars as a song in which pilgrims en route to Jerusalem relate escaping a dangerous situation.8 Alternative explanations exist, however.9 They range from a miraculous rescue of Jerusalem from the siege of Sennacherib (701 BCE) to the flight of the people from Babylonian exile and even to emancipation from the threat of Sanballat at the time of Nehemiah.10 Beyond this divergence of views, most investigators assume that the information supplied in Ps 124 is too fragmentary for identifying with precision the historical events related there.11 By extension, these circumstances are considered to be of secondary importance for the message of the poem.

In this perspective, the dangerous situation exposed in verses 3-5 became a hypothetical scenario introduced by the psalmist to emphasise the importance of divine protection for its overcoming (vv. 6-8).12 It reduces the drama to a rhetorical trigger leading to "... a meditation on what the fate of Israel would have been had it not been accompanied by YHWH."13Once transformed into a didactic sermon stimulating faith in YHWH, Ps 124 loses its linkages with the reality.14 Indeed, if Ps 124 exposes a hypothetical situation of divine abandonment of Israel (vv. 1-5) only to resolve it immediately after (vv. 6-8), we have no interest in trying to elucidate the nature of the dramatic event.15 Thus, Ps 124 remains a 'minor song' from the Ascent's corpus, which does not deserve special attention. Indeed, the concision of this song and its high level of indeterminacy generate a substantial level of speculation in interpretation. However, some characteristics of Ps 124 do not easily integrate the current interpretations. For example, whereas the poem is classically interpreted in the context of thanksgiving for divine salvation, the intervention of YHWH remains abnormally elusive. Instead of a mere poetic device, this singularity might reflect a theology of non-targeted intervention of YHWH distinct from the one promoted by most Israelite scribes, poets, and prophets. It may be a key to identifying the us-group and the content of this song.

B THE PROBLEM OF DIVINE INTERVENTION IN PS 124

YHWH's protective function in Ps 124 is generally deduced from the first two verses beginning with the expression If YHWH was not for us. Nevertheless, the original expression (לוּלֵי יְהוָה שֶׁהָיָה לָנוּ) is not a call for YHWH's intervention on the us-group's behalf.16 At best, this claim might introduce praise for divine intervention. Considered alone, however, it cannot express it.

An examination of the three last verses where YHWH is blessed confirms the lack of divine intervention in Ps 124. YHWH is praised in verse 6 not for liberating the us-group, but merely for not surrendering them to their enemies, that is, for his neutrality. Verse 7 confirms this interpretation. There, the deliverance issues from the snare's sudden break. Nevertheless, this verse does not claim that YHWH broke the snare trapping the us-group or facilitated their escape.

The us-group assumes divine help at the end of the song in verse 8. Curiously, however, it refers not to the god himself, but only to his name. Scholars assume equivalence between YHWH and the mention of his name, resolving with verse 8 the problem of divine intervention in Ps 124.17 Others interpret the focus on YHWH's name in verse 8 as an allusion to incantations used especially for perilous situations18 or even as a stereotyped liturgical formula.19 However, this ending of a song throughout which the divine intervention is silenced deserves special attention. It promotes a contemplative relationship with the deity rather than his supplication for the salvation of his devotees. This feature outruns the religious background of Ps 124 from the theology articulating the divine intervention towards Israel. It challenges the approach of Ps 124 as a sermon or a song of thanksgiving (national, communal or even individual), as generally assumed. The distance from the theology of salvation/retribution suggests two possible identities of the us-group. It may include Israelites worshipping YHWH but rejecting the idea of his direct intervention on their behalf. This belief is evidenced in the Zephaniah sermon condemning "those who say in their hearts, YHWH will not do good nor will he do ill" (Zeph 1:12b). Those believers are denounced in Isa 32:6 for their misconceptions and hopeless theology that negatively influence the Israelites, "To utter error concerning YHWH, to make empty the soul of the hungry, and to deprive the thirsty of drink" (Isa 32:6b).20 The Edomite refugees settling in Judah in the sixth century BCE, especially after the fall of Edom, are the other possible group defending such a theology of non-intervention of YHWH.21

C DOES THE US-GROUP BELONG TO ISRAEL?

Psalm 124 being integrated into the Psalter, the us-group may be spontaneously identified with Israel (or a part of it) in this song. This premise fits the general approach affiliating the worshipers of YHWH to Israel. However, the text of the song does not refer to the land of Israel. It does not anymore recall events from the Israelite history, the city of Jerusalem, its temple or festivals. Even YHWH is approached here as the demiurge (v. 8) rather than the God of Jacob. These singularities are unexpected of a song of pilgrimage or even of a sermon promoting the Israelite doctrine. Here, the most robust argument pleading for an Israelite identity of the us-group comes from verse 1b mentioning this nation. Let now examine its meaning.

1 Reference to Israel in 1b

Israel is mentioned in verse 1b, but the meaning of this acclamation remains obscure. It also poorly integrates the succession of claims in Ps 124. For this reason, many scholars identify 1b as a preparation to sing rather than an integrative part of the song. They assume that verse 1 relates the choirmaster reciting the first words of the song in 1a, and addressing the congregation of Israelite worshipers in 1b, so that the text of the poem begins only in verse 2.22Others interpret the opening claim ('Let Israel say/declaré'", v. 1b) as an invitation to recite the content of the psalm addressed to Israel, independently of its musical performance.23 Both readings promote an Israelite identity of the us-group.

Two possible interpretations of the expression "יאֹּמַר-נָא יִּשְרָאֵל' coexist, however. In the first one, reflected by the translation 'Let Israel say,' the subject of the verb, Israel, identifies the us-group. This reading is attested in Ps 118:2-4 where it unambiguously invites the Israelites to praise YHWH. However, the jussive form יאֹּמַר in 1b may also introduce an impersonal/indefinite subject so that the following locution becomes what the jussive of mr invites to claim. This use is attested in Psalms (Pss 35:25, 27; 40:17; 70:5; 107:2) and other sources (Deut 9:4; Jer 1:7; Joel 2:17; 4:10). In such a perspective, Israel becomes in Ps 124:1b the complement of a call that we may translate 'Let say: Israel.' This alternative reading transforms 1b into an invitation to integrate the community of Israel, to which the us-group did not belong before. The distance from the Israelite theology of divine intervention in Psalm 124 invites us to consider this latter eventuality seriously.

2 Indications from Ps 129

The call יאֹּמַר-נָא יִּשְרָאֵל in Ps 124:1b also exists in Ps 129:1b. In both psalms, the opening claim (1a) is reiterated in verse 2a. These parallels suggest that the expression יאֹּמַר-נָא יִּשְרָאֵל has a similar meaning in these two songs of Ascents.

Consequently, an examination of the content of Ps 129 might help us to determine which reading (Let Israel say - interpretation 1, or Let say: Israel -interpretation 2) should be preferred in both.

The author of Ps 129 opens the song (vv. 1a, 2a) by telling us s/he grew up in a hostile environment (Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth). The description of the poet's suffering extends to vv. 2a-3.

1 Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth-

Let say: Israel / Let Israel say

2 Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth,

Yet they have not prevailed against me.

3 The plowers plowed upon my back;

They made long their furrows.

In the absence of allusion to the Babylonian exile or any other major event in the history of Israel, we may deduce that the author here relates an autobiographical feature. It is why the call in Ps 129:1b cannot merely invite the whole of Israel to share it without detailing its nature. It is a first argument privileging the second interpretation of the expression יאֹּמַר-נָא יִּשְרָאֵל (let say: 'Israel') and of the us-group as foreigners joining Israel. Psalm 129:4 alludes to the psalmist's escape ("YHWH is righteous; he has cut the canopy/cords [עֲבוֹת] of the wicked'). Though the identity of the them-group denounced as wicked people remains mysterious in Ps 129, this verse tells about the escape of the psalmist (and the group s/he belongs to) from their dominion.24 This is another parallel with Ps 124, in which escape is the central theme. Ps 129:5 reveals that the wicked people hate Zion (May all who hate Zion be put to shame and turned backward!). The verb יֵבֹּשוּ (be put to shame) even suggests that the opposite attitude is expected from these tormentors. If this them-group is supposed to love Zion, we may deduce that these people honour YHWH and even worship him, precisely as the us-group does. This premise is confirmed a few verses later which reveal that people from this them-group hating Zion and tormenting the poet are blessed in the name of YHWH: "Wor do those who pass by say, 'The blessing of YHWH be upon you! We bless you in the name of YHWH!"' (Ps 129:8).

Worshippers of YHWH are generally identified only with Israel in modern scholarship. However, biblical sources reveal that YHWH was also worshiped outside of Israel and independently of it. The figure of Balaam, a prophet of YHWH and enemy of Israel, exemplifies this fact (Num 22-24).25The worship of YHWH among the nations, and independently of Israel, is explicit in Deut 33:3, mentioning elite people among the nations standing near YHWH. Malachi 1:11 even extends this non-Israelite worship to whole peoples. The non-Israelite worship of YHWH is also visible in the Psalter. Psalm 87 informs us (v. 4) that YHWH was worshiped in Tyre, among the Philistines and even in Nubia (Kush).26 Psalm 67 refers to the musical worship of YHWH among the nations.27 Psalm 42 is apparently the lament of a poet appointed to this foreign worship of YHWH, who longs for his homeland.

In Ps 129, we read that the us-group lived for a long time among the them-group before joining what is called here 'Israel'. The song also informs us that the them-group acknowledges and even worships YHWH, but hates Zion. If the song is dated to the early Persian period, as generally assumed concerning the Songs of Ascents,28 four possible situations about the identity of the protagonists emerge in Ps 129:

(i) The them-group may refer to the Judean population who did not experience the exile, and who do not participate in the reconstruction of Jerusalem and its temple, both initiatives of the post-exilic community. Then, the us-group represents a fraction of these non-exiled opponents who joined the returnees to reconstruct Jerusalem.

(ii) The us-group may be Israelites inhabiting the territory of the ancient Northern kingdom of Israel. The poem relates their joining the returnees in Jerusalem, notwithstanding the virulent opposition in Samaria to the reconstruction of the city of Jerusalem (Neh 3: 33-34; 4:1-2).

(iii) The them-group may designate here a neighbouring nation. In this case, the ws-group may be descendants of Judeans who fled to Ammon, Moab, Edom or Egypt with the Judean kingdom's collapse (Jer 40:11; 42:13-15). Psalm 129 expresses their aspiration to come back to their homeland to reconstruct Jerusalem.

(iv) The ws-group may belong to one of the neighbouring nations worshipping YHWH independently of Israel.29 In this case, we should assume that this group fled from their mother nation to join the Israelites participating in the restoration of the Yehud province, Jerusalem, and the temple of YHWH.

In both Pss 124 and 129, the likelihood of these four possibilities depend on the meaning of the expression יאֹּמַר-נָא יִּשְרָאֵל The solutions (i) and (ii) are conditioned by its reading, 'Let Israel say'. However, the likelihood of the alternative reading ('Let say: Israel') in Ps 129 promotes the third or fourth possibility. The absence of markers of the Israelite identity in both Pss 124 and 129 is unexpected if the us-group represents Israelite captives returning to their ancestral land (solution iii). Furthermore, the distance from the Israelite theology observed in Ps 124, especially concerning divine intervention, promotes the fourth solution. These considerations invite us to look for the them-group's identity in Pss 124 and 129 out of Israel and Judah. They also identify the us-group in both psalms as defectors joining Israel and integrating this nation.

D EDOMITE BACKGROUND OF THE US-GROUP

Though YHWH' s musical worship among the nations seems organised around the Jerusalem temple in Pss 42 and 87, Edom was of central importance in the non-Israelite worship of YHWH. Seir, the mountain identified with this nation, is also acknowledged as the holy site of YHWH's origin (Deut 33:2; Judg 5:4). The explicit mention of YHWH giving the mountain of Seir to Edom for eternity (in Deut 2:5) is conceivable only if this nation was considered, even by the Israelites, the depositary of the ancient Yahwistic traditions. This premise finds confirmation in Amos 9:12, a verse referring to Edom as the head of the nations that call YHWH's name. On the other hand, the Edomites are frequently blamed in the Bible for hating Israel and Zion when the kingdom of Judah collapsed (Ezek 35:5; Obad 10-14; Lam 4:21).30 This conjunction invites us to examine whether the them-group refers to Edom in Ps 124.

1 Adam in Ps 124

The them-group is collectively called Adam in Ps 124:2b. Most scholars deduce that this term designates humankind and that it refers indistinctly to all the tormentors of Israel-past, present and future.31 Alternatively, a few exegetes interpret Adam in verse 2 as the expression of the mythical enemy, the forces of chaos threatening both the existence of Israel and stability of the created universe.32 Beyond their speculative nature, these solutions may be relevant only if the us-group here identifies with Israel. However, the alternative approach that sees the us-group as defectors invites us to identify Adam with the land of their specific origin rather than as humankind. The phonetic closeness between Adam and Edom instead points to an Edomite origin of both the us and them groups.

This conclusion finds support in further appellations of Edom as Adam in the Bible. For example, the Adam-Edom identity emerges from the parallel mention of Edom in Ezek 35:1-15 and Adam in Ezek 36:1-15.33 The same wordplay between Adam and Edom is also visible in Ps 108:11 -14, where the same enemy is designated as the foes in 14b, as Adam in 13b, and as Edom in 11b.34

11 Who will bring me to the fortified city (עִיר מִבְצָר)?

Who will lead me to Edom?

12 Have you not rejected us, O God?

You do not go out, O God, with our armies.

13 Oh grant us help against the foe (עֶזְרָת מִצָר),

For vain is the salvation of Adam!

14 With God we shall do valiantly;

It is he who will tread down our foes

.

Additionally in Ps 14, a song denouncing the Edomites appointed in the Jerusalem temple (see below), the poet introduces the expression sons of Adam (bney Adam v. 2) not for designating them as humans, but for emphasising their Edomite origin.35

The author of Ps 124 represents Adam, the tormenting them-group, as predators (v. 6), hunters (v. 7), and even gluttonous people able to swallow the us-group alive (v. 3). These character traits are similar to those introduced in Genesis for describing Esau, the ancestor of Edom. Here too, Esau is represented as a hunter (Gen 25:27; 27:3) of violent and bloody character (Gen 27: 41-45). The gluttonous nature of Esau emanates in Gen 25:30-34 from the concession of his birth right to "swallow" (הַלְעִּיטֵ Gen 25:30) a pottage.

2 Evidence from Ps 120

The corpus of Ascents is a cluster of 15 psalms (Pss 120-134) relatively homogeneous in their vocabulary, expressions, poetical craft and theology.36 The features distinguishing these songs from all the other psalms suggest that they all emanate from a small atypical circle of poets.37

However, the Songs of Ascents do not refer to Israel's theological history and/or to the Israelite festivals commemorating them, as expected of pilgrim songs.38 In this corpus, the us-group no longer self-defines as sons of Zion, of Jacob or even of Exile.39 These observations invite us to consider seriously the possibility that the whole corpus of Songs of Ascents emanates from a group of non-Israelite Yahwists reaching Jerusalem in the early Persian period.

The content of the opening song, Ps 120, supports this premise. This song is generally interpreted as a poem expressing the eagerness of expatriate Israelites for a pilgrimage to the holy city.40 However, the lack of Israelite markers here combines with the mention of ironwork and weapon production (v. 4). Some details about the poet's outcast status and his commitments suggest that the author of this song is not an Israelite, as generally assumed. He is rather a metalworker living among foreign peoples but attached to the Yahwistic traditions of Edom (the nation organised around the production of metal at the early Iron Age) and/or the Qenites.41 The negative reference to Qedar and Meshek (v. 5) confirms the allegiance of this author to Edom, because both nations were involved in the conquest and destruction of Edom by Nabonidus (553 BC). The people from Qedar inherited the territory conquered by Nabonidus and his army, revealing that they were among the principal actors of this military campaign.42 Meshek was traditionally the source of the iron weapons used by the Assyrians and Babylonians.43 According to the Babylonian chronicles, Nabonidus' first military campaign in eastern Anatolia was apparently motivated by the control of iron production and the supply of iron weapons for his subsequent military conquest of Arabia.44 Psalm 120 expresses the distress of a smith involved in producing the weapons used by people participating in the destruction of Edom. In this perspective, this psalm opening the corpus of Ascents provides the background for an us-group of Edomite origin integrating the province of Yehud and the Israelite identity.45

3 Edomite singers in Jerusalem

The interpretation of the us-group as people moving from Edom to Israel finds support in further biblical sources. For example, Johan Lust assumes that the wordplay between Adam and Edom in Ezek 35-36 is a reaction to the infiltration in Yehud of Edomite refugees fleeing the collapse of their nation.46 Juan Tebes also argues that some Edomite refugees were appointed to the Jerusalem temple and they became a part of the Jerusalem clergy at the early Persian period.47 The mention of 'sons of Obed-Edom' among the temple staff (1 Chron 26: 4, 8, 15) supports this premise.48 Moreover, the Ezrahites, the sons of Heman and Ethan/Jeduthun (most of the singers involved in the musical worship of YHWH, see 1 Chron 25) were apparently Edomite refugees appointed to the Jerusalem temple in the early Persian period.49 The book of Nehemiah unveils a policy of integration of the Ezrahites in the post-exilic community.50

Another indication of the authorship of the Songs of Ascents by people of Edomite origin or allegiance comes from Ps 122. A comparison of this song's content with the narrative of the ceremony of the inauguration of the city-wall of Jerusalem (Neh 12:27-43) suggests that it was the song performed at this ceremony.51 Furthermore, the narration of the ceremony reveals that the Ezrahite singers conducted it. Beyond the inauguration of the city wall of Jerusalem, its purpose was apparently the integration of the Ezrahite/Edomite singers among the religious elite in Jerusalem.52

The Edomite presence awoke hostility among the members of the post-exilic community, especially the religious elite.53 Psalm 14 expresses this point and even reflects their demonisation by influential figures among the post-exilic elite in Jerusalem.54 The many conflicts among the temple staff between the Edomite singers and their peers of Israelite origin are also visible in Ps 92.55

Identifying the us-group in the Songs of Ascents with Edomite refugees finds support in the double conflict involving them and attested in this corpus. The first conflict, related in Pss 124 and 129, accounts for the hostility against the us-group in their land of origin. The second source of conflict, visible in Pss 123 and 130, results from the mockery and persecution of the us-group in their new surroundings (deduced from the lack of any reference to a past situation, unlike in Pss 124 and 129). It reflects the us-group's marginalised position at the time of the composition of the corpus of Ascents.56 This double conflict fits well the bitter fate of people moving between two hostile nations.

These considerations invite us to identify the us-group in Ps 124 as a community of Edomite refugees who successfully joined Israel against the will of their Edomite brethren. The claim that "Let say (now) IsraeF opening both Pss 124 and 129 probably expresses the new allegiance to Israel of the Edomite singers, poets and musicians. This identification illuminates why 'Adam' may be so angry against the us-group in Ps 124. Beyond the demonisation of Edom in many Israel prophecies, active participation of the Judeans (at least those deported to Babylonia) in the destruction of Edom by Nabonidus and his army (553 BCE) emanates from an Ezekiel oracle: "And I will lay my vengeance upon Edom by the hand of my people Israel, and they shall do in Edom according to my anger and according to my wrath, and they shall know my vengeance, declares my Lord YHWH" (Ezek 25:14).57 If this prophecy reflects a historical situation, joining the Israelites was probably regarded by the defeated Edomites as an act of treason. These circumstances might justify why the us-group, as defectors, praise YHWH for his passiveness in this conflict. They also clarify why the us-group does not ask YHWH to punish their tormenters, and why it does not even blame the Edomites for their violent, hostile reaction.

E COMPLEX ANTIPHONY IN PS 124

Clarifying the identity of the us and them groups is required in identifying the central theme of Ps 124, but it is not sufficient for elucidating its content. For this, a verse-to-verse analysis is required. However, this latter examination is fruitful only if the edited version of the psalm represents the final text. This is not always the case, especially in psalms displaying many discontinuities in claims and further inconsistencies once read linearly.58 When these inconsistencies are original features, they may indicate that the succession of verses, as edited in the Psalter, is not the final text, but only the raw material for its emergence. If the song is designed for two dialoguing choirs, each one may sing another part of the edited text so that distant fragments combine to generate a composite text. Defined as complex antiphony, this performance mode is evidenced in the Psalter and identified in the Bible as maskil.59Typically associated with YHWH's musical worship, this mode of performance is attested in some of the Songs of Ascents (Pss 121, 122, 126, 128, 132).60 In the early Persian period, it was identified apparently with the Ezrahites, the foreign singers of Edomite origin.61 This conjecture invites us to examine whether Ps 124 was designed for complex antiphony.

1 Structural properties

The hymnic exclamation at the beginning of verse 6 (Blessed be YHWH) suggests that Ps 124 subdivides into two main sections viz., verses 1-5 and verses 6-8.62 These two entities differ in structure. The first one begins with two verses (vv. 1-2) introduced by the same conditional locution ('^l?) and followed by three consecutive clauses (vv. 3-5), all beginning with the same particle then ('IN). Such a reiteration pattern is lacking in the second section (vv. 6-8). Furthermore, each of the five verses in the first section comprises two halves of similar length, whereas the verse structure is irregular in the second section due to the abnormal length of verse 7.

The two sections also differ in their literary cohesiveness. A consistent narrative emanates from the triad of verses 6-8 around the theme of the us-group' s hopeful issue. A similar level of literary coherency is absent from the first section, however. The repetition of the conditional sentence (vv. 1 -2) and the succession of three parallel clauses (vv. 3-5) create iterations that undermine any possibility of a narrative dimension. To resolve this problem, some scholars propose that verse 1 be excluded from the body of the song,63 whereas others assume that the answer to the first conditional sentence (verse 1) is missing.64The transition between verses 1 and 2 is not the only problem to resolve, however. The redundancy in the formulation of verses 3-5 prevents any substantial development in this section. Psalm 124 comprises a first section devoid of linear development (vv. 1 -5), followed by a poetic narration (vv. 6-8).

2 Case for shifting responsa in Ps 124

Examining the strophic division in psalms, Albert Condamin identified a tripartite structure (strophe, antistrophe and epode) in some songs of the Psalter.65 He assumed that the strophe and antistrophes were performed by two dialoguing choirs, which gathered their voice in the final section, the epode. To extend this approach to Ps 124, the second section (vv. 6-8) might be the epode concluding an antiphonal dialogue performed by the two choirs singing the first section (vv. 1-5), which itself divides into two units (vv. 1-2 and vv. 3-5).

The verses of the first unit (vv. 1-2) open with a conditional proposition (לולֵי) and those of the second one (vv. 3-5) all begin with a particle (אֲזַי)

complementing the conditional claim. This situation creates a dialogical pattern between a first voice opening with a conditional proposition (vv. 1 -2) and the other one (vv. 1-3), exposing the consequences of the hypothetical situation formulated by the first voice. This dialogue concludes with a final part (vv. 6-8) of declamatory character, sung simultaneously by the two voices.

If the two verses of the opening part begin with the same conditional proposition and the three verses of the response begin with the same causal locution, any verse in the first part may theoretically combine with any verse of the second part. Together with the unequal number of verses of both parts, this singularity fits a mode of complex antiphony already identified in Ps 122 and defined as shifting responsa.66Each choir repeatedly sings its part in this pattern. The unequal number of verses between the two generates permutations in verse pairing in each performance round.

3 The composite text of Ps 124

In complex antiphony, the dialogue involves segments of verses defined as antiphonal units (AU). Their pairing throughout the performance generates a succession of composite verses (CV). If we identify the antiphonal units with cola in Ps 124, each one of verses 1-5 includes two of them.67

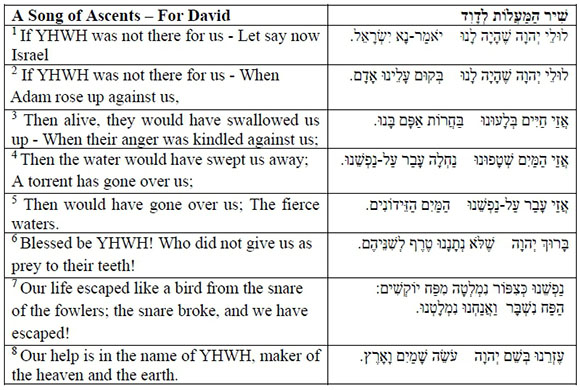

Consider that the first choir sings repeatedly verses 1 -2 (the conditional propositions) when the responding choir sings repeatedly verses 3-5 (the consequential propositions). We obtain all the possible pairings of antiphonal units through three rounds of singing the first voice text. A setting of the first section (vv. 1 -5) as shifting responsa and the second one (vv. 6-8) as an epode leads to the following composite text of Ps 124:

F ANALYSIS OF THE COMPOSITE TEXT

An overview of the composite text reveals that it comprises three opening claims. A first cluster (CV1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11) connects the only conditional proposition (If YHWH was not there for us, in v. 1a and v. 2a) with its corresponding claims of the responding voice. A second cluster (CV 2, 6, 10) combines the 1b opening claim (Let say now: Israel) with its three corresponding antiphonal units (3b, 5b, 4b). The third cluster gathers the composite verses 4, 8, 12 issued from the mingling of 2b (When Adam rose up against us) with the antiphonal units 4b, 3b and 5b, respectively. These three clusters are analysed here separately.

1 Cluster 1: If YHWH was not there for us (AU 1a/2a)

In the shifting responsa setting, the condition formulated in 1a/2a constitutes the opening claim of six among the twelve composite verses. This singularity transforms the statement that YHWH is the god of the us-group into the main refrain and central theme of the song. Such leitmotiv announces their loyalty to YHWH. This claim is especially welcome if the us-group represents defectors leaving one Yahwistic community (Edom) towards the other (Israel) and was potentially hated by both.

The composite verses CV1, CV3 and CV5 (= CV7, CV9 and CV11, respectively) do not only assert that YHWH is the god of the us-group (opening claim), they also make it blatant through the complementary claim. CV1 (= CV7) mentions that the us-group escaped with the help of their faith in YHWH and CV3 (= CV9) carries the same message. The third pairing (CV5, CV11) introduces a novelty. In the linear reading, 5a is a reformulation of 4b, a feature promoting its interpretation as water flooding the us-group. However, once isolated from 4b through its link with the 1a/2a antiphonal unit, the subject of the verb br in 5a is not the water (4b) but YHWH himself (1a/2a). A new meaning emerges from the expression in 5a (אֲזַי עָבַר עַל-נַפְשֵנוּ), that of YHWH passing over the transgressions of the us-group (as in Exod 34:6) once they join Israel. The following claim in which the us-group declares its (new) allegiance to Israel (1b: Let say now: Israel), strengthens this interpretation. In CV11, the divine forgiveness contrasts with the anger the departing us-group stimulates among the Edomites, revealed immediately after, in CV12 (2b). It renders the message of CV5/11 specially adapted to the Israelite audience. It invites their host to imitate YHWH and pass over the 'sins' of these defectors inherent in their Edomite identity and past activities.

2 Cluster 2: Let say now: Israel (AU 1b)

The claim 'Let say now: Israel' (1b) of the us-group joining Israel is the first half of the composite verses CV2, CV6 and CV10. The complementary claims (AU 3b, 5b and 4b respectively) contribute to this meaning. In CV2, the 3b antiphonal unit expresses deep anger against the us-group, which becomes the Edomites' reaction to the defection of their brothers joining Israel (AU 1b).

In the second occurrence (CV6), the expression 'Let say now: Israel' (1b) now combines with 5b (הַמַ ים הַזֵידוֹנִּים ).. The adjective zêdön is a hapax, which probably derives from the root zwd, referring to something high, rising or elevated.68 Then the adjective zêdôn becomes a substantive, expressing a situation of overflowing and furiously agitated water.69 In the context of the us-group joining Israel, the fierce water might refer to the Gihon spring from Jerusalem. By this means, the poet acknowledges Jerusalem as the (new) source of life, wealth and blessing.

The third occurrence (CV 10) combines the 1b claim (Let say now: Israel) with the mention of water flooding the us-group (4b: A torrent has gone over us), that is, moving them from their homeland to Israel. The use of the term nahälä in 4b confirms this interpretation through its double meaning-torrent and domain (land). This latter meaning adds significance in CV10; through their defection to Israel, the us-group lost their land of inheritance and former identity. By this means, the us-group expresses the irreversibility of their defection, a point of particular importance to their Israelite hosts.

3 Cluster 3: When Adam rose up against us (AU 2b)

The 2b antiphonal unit, the first half of CV4, CV8 and CV12, reflects the reaction of the Edomites (Adam) following the us-group's decision to join Israel (formulated in CV2). In reading nahälä (4b) as a land of inheritance, we learn in CV4 that the Edomites' initial reaction was to deprive these defectors of their possessions. The Edomites' reaction amplifies in CV8, the second composite verse expressing their deep anger (3b). The third occurrence (CV12), which is also the last composite verse, associates the reaction of the Edomites (2b) with the mention of fierce water (5b: הַמַיִם הַזֵידוֹנִים ). Unlike the positive association of zêdôn in the Israelite context (CV6), its formulation in CV12 probably likens the Edomites' burning anger to hot/boiling waters. This image combines with the figurative meaning of zêdön (= proud and presumptuous character),70 which here denounces the bitter retaliation of the Edomites against Israel. Again, this insinuation is especially welcome in a song these defectors address to their new host, the Israelite community.

This analysis reveals how the shifting responsa setting resolves the incoherency of the two successive conditional propositions (vv. 1 -2), followed by three consecutive consequential sentences. It also reveals three main features advanced by the us-group in this song-their attachment to YHWH, their decision to leave Edom for Israel and the reaction their decision stimulated among their brethren. The three verses of the epode resume the entire story by praising YHWH in verses 6 and 8 and likening the us-group with birds escaping from their snare (v. 7).

G CONCLUSION

The present investigation advances two features previously ignored in the interpretation of Ps 124. The first concerns the us-group, now identified as Edomite defectors reaching Jerusalem in the late Babylonian/early Persian period. The second is the series of claims emerging from the setting of Ps 124 (part 1) in shifting responsa. These two novelties are intrusive; the content of the composite verses becomes clear after identifying the us-group as Edomite defectors joining Israel and vice versa. These observations corroborate previous conclusions about the presence of Edomites in Yehud in the early Persian period. They also highlight the hostility between Edom and Israel at the end of the sixth century BCE, and its consequences for the Edomites rallying Yehud. This entangled situation may explain the us-group's artifices in Ps 124 to swear that they left their former identity to join the Israelites.

These findings corroborate previous observations that challenge the interpretation of the Songs of Ascents as a collection of pilgrim songs or of pieces of liturgy for a festival celebrated in the Jerusalem temple. Rather, the findings here support the thesis of Edomite authorship of the Songs of Ascents already suggested from the content of Ps 120. By its content, Ps 124 adds essential information. It reveals that the whole corpus belongs to a group of Edomite defectors exposing their motivations for joining the Israelites in Yehud, claiming their loyalty to their hosts and adopting the Israelite form of Yahwism.

H BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albright, William F. "Cilicia and Babylonia under the Chaldaean Kings." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 120 (1950): 22-25. [ Links ]

Allen, Leslie C. Psalms 101-150. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2002. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. "The Cosmopolitan Nature of the Korahite Musical Congregation: Evidence from Psalm 87." Vetus Testamentum 64 (2014): 361-381. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. "The Musical Mode of Writing of the Psalms and Its Significance." Old Testament Essays 27 (2014):17-40. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. "Psalm 67 and the Cosmopolite Musical Worship of YHWH." Bulletin for Biblical Research 25 (2015): 31-48. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. Esau in Jerusalem: The Rise of a Seirite Religious Elite in Zion at the Persian Period. Leuven: Peeters, 2015. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. "The Subversive Dimension of the Story of Jehoshaphat's War against the Nations (2 Chron 20:1-30)." Biblical Interpretation 24 (2016): 178-202. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. "Foreign Yahwistic Singers in the Jerusalem Temple? Evidence from Psalm 92." Scandinavian Journalfor the Old Testament 31 (2017): 213-235. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim. "Psalm 120 and the Question of Authorship of the Songs of Ascents." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 45 (2021, in press). [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim and Avriel Mikhal. "Complex Antiphony in Psalms 121, 126 and 128: The Steady Responsa Hypothesis." Old Testament Essays 23 (2010): 502-518. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim and Mikhal Avriel. "Psalm 122 as the Song Performed at the Ceremony of Dedication of the City Wall of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 12, 27-43)." Scandinavian Journal for the Old Testament 30 (2016): 44-66. [ Links ]

Amzallag, Nissim and Shamir Yona. "What Does Maskil in the Heading of a Psalm Mean?" Ancient Near Eastern Studies 53 (2016): 41-57. [ Links ]

Assis, Elie. Identity in Conflict: The Struggle between Esau and Jacob, Edom and Israel. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2016, [ Links ]

Auffret, Pierre. La oil montent les tribus: Étude structurelle de la collection des psaumes des Montees, d'Ex 15: 1-18 et des rapports entre eux. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1999. [ Links ]

Barker, David G. "Voices for the Pilgrimage: A Study in the Psalms of Ascent." Expository Times 116 (2005): 109-116. [ Links ]

Beaucamp, Évode. Le Psautier. Vol. 2. Paris: Gabalda, 1979. [ Links ]

Beaulieu, Paul-Alain. The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556-539 BC. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "A Jewish Sect of the Persian Period." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52 (1990): 5-20. [ Links ]

Booij, Thijs. "Psalms 120-136: Songs for a Great Festival." Biblica 91 (2010): 241-255.3 [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles A. and Briggs Emily G. Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Vol 2. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1907. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter and William R. Bellinger. Psalms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard J. Psalms 73-150. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Condamin, Albert. Poèmes de la Bible. Paris: Beauchesne, 1933. [ Links ]

Crow, Loren D. The Songs of Ascents (Psalms 120-134). Their Place in Israelite History and Religion. Atlanta: Scholar Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Dicou, Bert. Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist: The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Elat, Moshe. "The Iron Export from Uzal (Ezekiel XXVII 19)." Vetus Testamentum 33 (1983): 323-330. [ Links ]

Gadd, Cyril J. "The Harran Inscriptions of Nabonidus." Anatolian Studies 8 (1958): 35-92. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. Psalms - Part II and Lamentations. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Girard, Marc. Les Psaumes redécouverts : De la structure au sens. Vol. 3. Montreal: Bellarmin, 1984. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. Psalms 3 (90-150). Grand Rapids: Baker Academics, 2008. [ Links ]

Goulder, Michael D. The Psalms of the Return (Book V, Psalms 107-150). Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 258. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Groenewald, Alphonso. "Who Are the Servants (Psalm 69:36c-37b)? A Contribution to the History of the Literature of the Old Testament." HTS: Theological Studies 59 (2003): 735-761. [ Links ]

Hakham, Amos. Psalms II. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1979. [ Links ]

Koehler, Ludwig and Walter Baumgartner. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT). Leiden: Brill, 1996. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank L. and Erich Zenger. Psalms 3. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2011. [ Links ]

Keet, Cuthbert C. A Study of the Psalms of Ascents: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary upon Psalms CXX to CXXXIV. London: The Mitre Press, 1969. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalms. A Commentary. Vol. 2 (Psalms 60-150). Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1989. [ Links ]

Leow, Wen-Pin. "Changing One's Tune: Re-reading the Structure of Psalm 132 as Complex Antiphony." Old Testament Essays 32 (2019): 32-57. [ Links ]

Leuchter, Mark A. "The Politics of Ritual Rhetoric: A Proposed Sociopolitical Context for the Redaction of Leviticus 1-16." Vetus Testamentum 60 (2010): 345-365. [ Links ]

Limburg, James. Psalms. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Lindsay, John. "The Babylonian Kings and Edom, 605-550 BC." Palestine Exploration Quarterly 108 (1976): 23-39. [ Links ]

Lust, Johan. "Edom: Adam in Ezekiel in the MT and LXX." Pages 387-401 in Studies in the Hebrew Bible, Qumran and the Septuagint: Essays Presented to Eugene Ulrich on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Edited by James C. VanderKam, Peter W. Flint and Emmanuel Tov. Leiden: Brill, 2006. [ Links ]

Maillot, Alphonse and André Lelièvre. Les Psaumes. Vol. 3 (101 -150). Genève: Labor et Fidès, 1966. [ Links ]

McKenzie, Tracy. "Edom's Desolation and Adam's Multiplication. Parallelisms in Ezek 35:1-36:15." Pages 90-119 in Text and Canon: Essays in Honor of John H. Sailhamer. Edited by Robert L. Cole and Paul J. Kissling. Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2017. [ Links ]

Mathews, Claire R. Defending Zion. Edom 's Desolation and Jacob 's Restoration (Isaiah 34-35) in Context. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995. [ Links ]

Niccacci, Alviero. "Analyzing Biblical Hebrew Poetry." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 74 (1997): 77-93. [ Links ]

Pope, Marvin. "Isaiah 34 in Relation to Isaiah 35, 40-66." Journal of Biblical Literature 71 (1952): 235-243. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T.M. "Historical Reality and Mythological Metaphor in Psalm 124." Old Testament Essays 18 (2003): 790-810. [ Links ]

Schökel, Alonso Luis. "Poésie hébraïque." Pages 47-90 in Supplément au dictionnaire de la Bible. Vol. 8. Edited by Louis Pirot and André Robert. Paris: Letouzey, 1972. [ Links ]

Seybold, Klaus. Die Wallfahrtpsalmen. Studien zur Entstehungsgeschichte von Psalm 120-134. Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1978. [ Links ]

Talstra, Epp. "Reading Biblical Hebrew Poetry. Linguistic Structure or Rhetorical Device?" Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 25 (1999): 101-126. [ Links ]

Tan, Nancy. "The Chronicler's Obed-Edom: A Foreigner and/or a Levite?" Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 32 (2007): 217-230. [ Links ]

Tebes, Juan M. "The Edomite Involvement in the Destruction of the First Temple: A Case of Stab-in-the-Back Tradition?" Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36 (2011): 219-255. [ Links ]

Tournay, Raymond J. Voir et entendre Dieu avec les Psaumes ou la liturgie prophétique du Second Temple ά Jérusalem. Paris : Gabalda, 1988. [ Links ]

Viviers, Hendrik. "The Coherence of the Ma'alöt Psalms (Pss 120-134)." Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentlische Wissenschaft 106 (1994): 275-289. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. "Biblio Pss1990+. Bibliography of Psalms and the Psalter in Conjunction with the History of Interpretation and Application of Psalms (Since 1990)." Online: http://bienenberg.academia.edu/BeatWeber (update 24), 2017. [ Links ]

Weiser, Artur. The Psalms: A Commentary. London: SCM Press, 1962. [ Links ]

Wildberger, Hans. Isaiah 28-39: A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002. [ Links ]

Submitted: 08/12/2020

Peer-reviewed: 05/05/2021

Accepted: 10/05/2021.

Dr. Nissim Amzallag is of the Department of Bible, Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies, The Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel. Email address: nissamz@post.bgu.ac.il. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9999-7052

1 Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms. A Commentary (vol. 2; Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1989), 440; Gert Prinsloo, "Historical Reality and Mythological Metaphor in Psalm 124," OTE 18 (2003): 789-790. The post-exilic composition of Ps 124 is deduced from its content. See Kraus, Psalms 2, 441; Richard Clifford, Psalms 73-150 (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2003), 230; Frank L. Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 3 (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2011), 354 and general considerations about the date of composition of the corpus of Ascents. See Hendrik Viviers, "The Coherence of the Ma'alöt Psalms (Pss 120-134)," ZAW 106 (1994): 288; Michael D. Goulder, The Psalms of the Return (Book V, Psalms 107-150) (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998); Loren D. Crow, The Songs of Ascents (Psalms 120-134): Their Place in Israelite History and Religion (Atlanta: Scholar Press, 1996), 171; David G. Barker, "Voices for the Pilgrimage: A Study in the Psalms of Ascent," Expository Time 116 (2005): 110; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 294.

An examination of Ps 124 reveals that it is not as straightforward as it appears at first glance. The identity of the two protagonists, the us-group and their tormentors, the them-group, remains silenced. The conflict between the two groups and the motivations for fleeing are no more explicit. The lack of geographical markers prevents also the identifying of the locations. Consequently, the supposed clarity of the content of this psalm results mainly from the premises conditioning its reading and it is deduced from the interpretation of the other Songs of Ascents.

2 Marc Girard, Les Psaumes redécouverts: De la structure au sens (vol. 3; Montréal: Bellarmin, 1984), 320. Concerning the interpretation of Ps 124 as collective thanksgiving, see Kraus Psalms 2, 440 and Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 353.

3 Prinsloo, "Historical Reality," 790. In its recent bibliography of Psalm research, Beat Weber, "Biblio Pss1990+: Bibliography of Psalms and the Psalter in Conjunction with the History of Interpretation and Application of Psalms (since 1990)." Online: //bienenberg.academia.edu/BeatWeber (update 24); 100, quotes only four papers devoted to Psalm 124.

4 This trend finds support in the high level of homogeneity of the Songs of Ascents, in themes, language, poetical composition and theology. See Évode Beaucamp, Le Psautier (vol. 2; Paris: Gabalda, 1979), 242-247; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 295. Some scholars even assume that a single hand wrote the entire corpus of the Songs of Ascents. See Viviers, "Coherence," 288; Goulder, The Psalms of the Return.

5 Beaucamp, Psautier 2, 248; Goulder, The Psalms of the Return, 44; Thijs Booij, "Psalms 120-136: Songs for a Great Festival," Biblica 91 (2010): 253; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 294.

6 Klaus Seybold, Die Wallfahrtpsalmen: Studien zur Entstehungsgeschichte von Psalm 120-134 (Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1978), 73; Booij, "Psalms 120-136," 245; Crow, Songs of Ascents, 182.

7 As shown by Crow, Songs of Ascents, 24-25, this opinion is widespread among scholars. See for example Seybold, Wallfahrtpsalmen, 73; Barker, "Voices for the Pilgrimage," 109-111.

8 For example, it was suggested that the psalm accounts for a miraculous escape of pilgrims en route to Jerusalem. See Alphonse Maillot and André Lelièvre, Les Psaumes (vol. 3, 101-150; Genève: Labor et Fidès, 1966), 151; Leslie C. Allen, Psalms 101-50 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2002), 164.

9 Crow, Songs of Ascents, 157-158; Viviers, "Coherence," 288; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 294.

10 See Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 354, and the references therein.

11 Crow, Songs of Ascents, 53; Clifford, Psalms 73-150, 229.

12 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 353.

13 Walter Brueggemann and William R. Bellinger, Psalms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 534.

14 Cuthbert C. Keet, A Study of the Psalms of Ascents: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary upon Psalms CXX to CXXXIV (London: The Mitre Press, 1969), 41; Kraus, Psalms 2, 442.

15 For example, Girard, Psaumes redécouverts 3, 320; Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms:Part II and Lamentations (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 333; Crow, Songs of Ascents,, 52. Prinsloo, "Historical Reality," 808, even identifies the enemies in Ps 124 with the forces of chaos fighting against the forces of creation ruled by YHWH.

16 This expression may be compared with the claim in Hos 1:9, "וְאָנֹּכִּי לאֹּ-אֶׁהְיֶׁה לָכֶׁם ," which is interpreted (HALOT 2: 510) in the context of the mutual relationship between the god and Israel: "I have nothing to do with you."

17 Keet, Psalms of Ascents, 45.

18 Allen, Psalms 101-150, 163; Kraus, Psalms 2, 442; Maillot and Lelièvre, Psaumes 3, 1 52.

19 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 535.

20 Hans Wildberger, Isaiah 28-39: A Continental Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002), 287, concludes that these opponents "... are in no way atheists; one might assume that they might actually be quite pious. But they have no concern for the ברי ת (covenant), for the simple rules for a community that is grounded in faithfulness and faith . . ." A similar reference to this alternative form of Yahwism is observed in Isa 5:19; 66:5.

21 See Nissim Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem: The Rise of a Seirite Religious Elite in Zion at the Persian Period (Leuven: Peeters, 2015).

22 Crow, Songs of Ascents, 52; Allen, Psalms 101-150, 164; Clifford, Psalms 73-150, 230.

23 Amos Hakham, Psalms II (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1979), 456. This trend is even more pronounced in Crow's translation of Ps 124, Songs of Ascents, 51-52, where the first and second hemiverses become inverted: "Let Israel say the 'If it were not YHWH who was for us'"

24 Clifford, Psalms 73-150, 245; James Limburg, Psalms (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000), 445; Gerstenberger, Psalms 2, 234.

25 In this story also, the mention of Balaq, the king of Moab, sacrificing holocausts to YHWH for cursing Israel (Num 23:1-3), challenges the assumption of the exclusiveness of the YHWH-Israel relationship.

26 Nissim Amzallag, "The Cosmopolitan Nature of the Korahite Musical Congregation: Evidence from Psalm 87," VT 64 (2014): 361-381.

27 Nissim Amzallag, "Psalm 67 and the Cosmopolite Musical Worship of YHWH," BBR 25 (2015): 31-48.

28 Viviers, "Coherence," 288; Crow, Songs of Ascents, 167; Barker, "Voices for the Pilgrimage," 110; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 294. The mention of the temple in Ps 122 reveals that they were not composed before the beginning of the Persian period (515 BCE), the time of its reconstruction. The reference to Ps 132 in the Solomon Prayer (2 Chron 6:40-42) indicates that they already existed before the redaction of the Chronicles. Goulder, The Psalms of the Return, 28 and Crow, Songs of Ascent, 171, suggest that this corpus belongs to the period of Nehemiah. The identification of Ps 122 as the song performed at the dedication ceremony of the city wall (Neh. 12. 27-43) supports this view. See Nissim Amzallag and Mikhal Avriel, "Psalm 122 as the Song Performed at the Ceremony of Dedication of the City Wall of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 12, 27-43)," SJOT 30 (2016): 44-66.

29 Deuteronomy 2 reveals YHWH's commitment to Ammon, Moab, or Edom them. The prophecies addressed to these nations confirm this point, together with the Jehoshaphat war against them, related in 2 Chron 20: 1 -30. See Nissim Amzallag, "The Subversive Dimension of the Story of Jehoshaphat's War against the Nations (2 Chron 20:1-30)," Biblical Interpretation 24 (2016): 178-202.

30 Elie Assis, Identity in Conflict: The Struggle between Esau and Jacob, Edom and Israel (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2016), 11 -14. For a general view of Israel and Edom's mutual hostility, see Bert Dicou, Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist: The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994), 20-115, 182-197; Claire R. Mathews, Defending Zion: Edom's Desolation and Jacob's Restoration (Isaiah 34-35) in Context (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995), 69-119; Assis, Identity in Conflict, 74-91.

31 Kraus, Psalms 2, 441; Hakham, Psalms 2, 456; Clifford, Psalms 73-150, 229; Prinsloo, "Historical Reality," 793; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 352; Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 535. Charles A. Briggs and Emily G. Briggs, Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms (vol. 2; Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1907), 452, already noticed that the use of Adam=humankind is too general for designating an enemy and concluded that this claim does not belong to the original song.

32 Gerstenberger, Psalms 2, 334-336; Prinsloo, "Historical Reality," 793; Goulder, The Psalms of the Return, 54; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 353.

33 Johan Lust, "Edom: Adam in Ezekiel in the MT and LXX," in Studies in the Hebrew Bible, Qumran and the Septuagint: Essays Presented to Eugene Ulrich on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday (ed. James C. VanderKam, Peter W. Flint and Emmanuel Tov; Leiden: Brill, 2006), 394-395 and Tracy McKenzie, "Edom's Desolation and Adam's Multiplication. Parallelisms in Ezek 35:1-36:15," in Text and Canon: Essays in Honor of John H. Sailhamer (ed. Robert L. Cole and Paul J. Kissling; Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2017), 91 -92, 102-103.

34 The second meaning of 13a refers to the siege of the city, a probable reference to the Israelite conquest of Bozrah mentioned in 11a. If 13a refers to the military conquest of Bozrah (and the other fortified cities of the Edomites), Adam in the second hemiverse relates necessarily to the besieged Edomites. It means that two parallel wordplays exist here. The first concerns the root swr, encountered in verses 11, 13 and 14. It designates foes in verse 14, and a fortified city (מִּבְצָ) in verse 11a. In verse 13a, the expression עזרת מצר 57 is generally understood as help against the foes, but the military context of this cluster of verses invites us to identify also the area (עזרה ) in which the Israelites besiege (מצר ) the cities of their enemies.

35 See Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem, 131-133. A similar use of Adam for designating Edom is suggested in Ps 76:11. See Raymond J. Tournay, Voir et entendre Dieu avec les Psaumes ou La liturgieprophétique du Second Temple ά Jerusalem (Paris: Gabalda, 1988), 117.

36 Beaucamp, Psautier 2, 240; Goulder, The Psalms of the Return, 45; Crow, Songs of Ascent, 160-161.

37 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 295. Beaucamp (Psautier 2, 240-243, 247) assumes that the whole collection articulates around a single theme and that the songs all express the same theological views. Due to their homogeneity and singularity, Viviers, "Coherence," 288 and Goulder, The Psalms of the Return, 43, even suggested that one single hand composed all of them.

38 Viviers "Coherence," 279, 284; Beaucamp, Psautier 2, 249.

39 Beaucamp, Psautier 2, 249.

40 Girard, Psaumes redécouverts 3, 292; Allen, Psalms 101-150, 200.

41 Nissim Amzallag, "Psalm 120 and the Question of Authorship of the Songs of Ascents," JSOT 45 (2021).

42 Cyril J. Gadd, "The Harran Inscriptions of Nabonidus," Anatolian Studies 8 (1958): 77-78; John Lindsay, "The Babylonian Kings and Edom, 605-550 BC," PEQ 108 (1976): 31-32; Crow, Songs of Ascents, 37.

43 William F. Albright, "Cilicia and Babylonia under the Chaldaean Kings," BASOR 120 (1950): 24.

44 Albright, "Cilicia," 25; Moshe Elat, "The Iron Export from Uzal (Ezekiel XXVII 19)," VT 33 (1983): 325.

45 Amzallag, "Psalm 120."

46 Lust, "Edom-Adam," 400.

47 Juan Tebes, "The Edomite Involvement in the Destruction of the First Temple: A Case of Stab-in-the-Back Tradition?" JSOT 36 (2011): 253. In parallel, scholars have noted deep divergences in theological positions of the psalms, especially those constituting the fifth book (Ps 107-150). Again, they justify this situation by integrating foreign elements with the clergy of the Jerusalem temple. See Joseph Blenkinsopp, "A Jewish Sect of the Persian Period," CBQ 52 (1990): 5-20; Alphonso Groenewald, "Who Are the Servants (Psalm 69:36c-37b)? A Contribution to the History of the Literature of the Old Testament," HTS: Theological Studies 59 (2003): 735-761; Mark A. Leuchter, "The Politics of Ritual Rhetoric: A Proposed Sociopolitical Context for the Redaction of Leviticus 1-16," VT 60 (2010): 345-365.

48 Nancy Tan, "The Chronicler's Obed-Edom: A Foreigner and/or a Levite?" JSOT 32 (2007): 217-230; Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem, 231-232.

49 Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem.

50 Ibid., 75-142.

51 Ibid., 111-120; Amzallag and Avriel, "Psalm 122." It is noteworthy that this appointment of the Ezrahite singers was accompanied by their full integration into the community including a new affiliation to Israel. This feature is revealed by the content of Neh 10, identified as a ceremonial of their integration in the community. See Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem, 77-96.

52 Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem, 111 -120.

53 Ibid., 121-142.

54 Ibid., 127-142.

55 Nissim Amzallag, "Foreign Yahwistic Singers in the Jerusalem Temple? Evidence from Psalm 92," SJOT 31 (2017): 213-235.

56 This latter conflict led Prinsloo, "Historical Reality," 800, to conclude that the authors of the songs of Ascents belong to a group of marginalised poets and singers living in Jerusalem at the early Persian period: "The presence of these terms in the songs of Ascents indicates that these are the songs of a politically and religiously marginalized community that are constantly under pressure, not from enemies from outside, but from the aristocracy in Jerusalem."

57 Marvin Pope, "Isaiah 34 in Relation to Isaiah 35, 40-66," JBL 71 (1952): 243; Gadd, "Harran Inscriptions," 86-88; Lindsay, "Babylonian Kings," 39; Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Reign of Nabonidus: King of Babylon 556-539 BC (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 174.

58 Luis Alonso Schökel, "Poésie hébraïque," in Supplément au dictionnaire de la Bible (vol. 8; ed. Louis Pirot and André Robert; Paris: Letouzey, 1972), 73; Alviero Niccacci, "Analyzing Biblical Hebrew Poetry," JSOT 74 (1997): 77-78; Epp Talstra, "Reading Biblical Hebrew Poetry: Linguistic Structure or Rhetorical Device?" JNSL 25 (1999): 103.

59 Nissim Amzallag, "The Musical Mode of Writing of the Psalms and Its Significance," OTE 27 (2014): 17-40; Nissim Amzallag and Shamir Yona, "What Does Maskil in the Heading of a Psalm Mean?" Ancient Near Eastern Studies 53 (2016): 41-57.

60 Nissim Amzallag and Mikhal Avriel, "Complex Antiphony in Psalms 121, 126 and 128: The Steady Responsa Hypothesis," OTE 23 (2010): 502-518; Amzallag and Avriel, "Psalm 122," Wen-Pin Leow, "Changing One's Tune: Re-reading the Structure of Psalm 132 as Complex Antiphony," OTE 32 (2019): 32-57.

61 Amzallag, Esau in Jerusalem, 127-142; Amzallag, "Foreign Yahwistic Singers."

62 Allen, Psalms 101-150, 164; Artur Weiser, The Psalms: A Commentary (London: SCM Press, 1962), 755; Prinsloo, "Historical Reality," 801-802; John Goldingay, Psalms 3 (90-150) (Grand Rapids: Baker Academics, 2008), 478; Girard, Psaumes redécouverts 3, 317; Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 352.

63 Allen, Psalms 101-150, 164; Crow, Songs of Ascents, 52; Clifford, Psalms 73-150, 230; Hakham, Psalms 2, 456.

64 Pierre Auffret, La oil montent les tribus: Étude structurelle de la collection des psaumes des Montees, d'Ex 15: 1-18 et des rapports entre eux (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1999), 455.

65 Albert Condamin, Poèmes de la Bible (Paris: Beauchesne, 1933), 27-28.

66 Amzallag and Avriel, "Psalm 122."

67 This division of verses in two antiphonal units is already observed in other songs of Ascents, such as Pss 121, 122, 126, 128 and 132. See Amzallag and Avriel, "Complex Antiphony"; idem., "Psalm 122" and Leow, "Changing One's Tune."

68 Keet, Psalms of Ascents, 43.

69 HALOT 1: 268.

70 Keet, Psalms of Ascents, 43.