Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.33 no.3 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2020/v33n3a19

PART II: PSALMODY AND SUFFERING

Suffering in the Epic of Gilgamesh

Gerda de Villiers

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

This article examines moments of suffering in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Initially Gilgamesh himself causes much suffering by abusing his power as king and tormenting his subjects day and night. Enkidu is created to curb the king's energy and to alleviate the distress of the people. Gilgamesh's greatest joy in finding a true friend also turns into his greatest sorrow when Enkidu becomes ill and dies. Gilgamesh is inconsolable and his suffering drives him away from his palace and his city, in search of life everlasting. When a snake snatches away his last hope of living forever, he realises that life eternal is to be found in life here and now. The article concludes with some suggestions of appropriating Elizabeth Kubler Ross'five stages of grief to the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Keywords: Gilgamesh, Enkidu, Uruk, Suffering, Trauma, Grief, Death

A INTRODUCTION

During the recent three decades or so, the Epic of Gilgamesh has attracted the attention of several scholars for various reasons. Works from the ancient Greek and Roman world, like those of Homer, Hesiod and Virgil, were known for many ages and they inspired especially the artists of the Renaissance period. However, not much, if any knowledge existed about ancient Mesopotamia and the great civilizations of Babylon and Assyria, except for the rather negative portrayal of these cultures in the Hebrew Bible. Interest in the Gilgamesh Epic was sparked only in 1872 when George Smith, a brilliant amateur Assyriologist deciphered Tablet XI of the Epic, whilst working in the British Museum.1 To his astonishment Smith realised that what he was reading, was in fact the so-called Babylonian Flood narrative, which has remarkable resemblances with but also shows significant differences from the biblical account of the Deluge (Gen 911). Its relationship to the Gilgamesh Epic became evident only some years after the discovery, decipherment and pasting together other fragments of the story. What emerged was not an epic of national scope and heroic victories, but a moving recount of one man's struggle with humanity's deepest existential question: the "grim struggle with death."2

B RATIONALE FOR THE ARTICLE

Although the Gilgamesh Epic is not primarily known as a narrative of suffering, like Ludlul Bël Nëmëqi or the Babylonian Job, for example, suffering is a prominent motif in the story: Tablets VII-X are all about agony and suffering. Whereas the Epic is also not a religious text as such, religious actions and conduct, and the relationship between humans and the divine, are certainly important in the plot. Lastly, although the Gilgamesh Epic is not a hymn or a psalm, it is poetry. The whole of the Epic is in fact a long narrative poem. As Michael Schmidt remarks, in reference to a conversation between Bill Griffiths and Paul Batchelor, the Gilgamesh Epic is "... basically a balanced line, like the Psalms, with a repetition of sense in the two halves of the line: sense and rhythm."3

Since numerous synopses of the Gilgamesh Epic are available on the internet -albeit not always equally informative-this article will refrain from providing one. Rather moments of suffering will be examined in some detail, and the progress of the narrative will be outlined briefly. Unless otherwise indicated, the plot of the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic will be followed.4Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are from Andrew George, as rendered in his major work of 2003: The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Tests. Volume 1.5References to Tablets will be indicated with Roman numerals, followed by a colon and common numbers specifying the lines.

C SUFFERING IN THE GILGAMESH EPIC

1 The townsfolk of Uruk

Tablet I of the Epic opens with an invitation to the reader and presents a view of the city of Uruk and its surroundings. Then King Gilgamesh is introduced as being partly human (two-thirds), and partly divine (one-third), a wise, just and brave king, as may be expected from the monarch of a city. However, this was not always the case. Soon an arrogant young Gilgamesh appears on the scene who abuses his power rather brutally by tormenting his subjects day and night, men and women alike.6 Thus, the very first instance of suffering in the Gilgamesh Epic is caused by Gilgamesh himself (I:63-92).

The suffering of the townsfolk makes the women of Uruk cry out to Aruru, a creator goddess, to create a double for King Gilgamesh, someone to keep him busy so that the people of the city may have some peace (I:95-98). Aruru heeds their prayer. She washes her hands, pinches off a piece of clay and throws it onto the steppe. Enkidu, who is to be a match for Gilgamesh, then, comes into being but he is not human yet. He is big and hairy, eats grass and drinks water, and he frolics with the animals at the waterhole (I:109-112). In the meantime, Gilgamesh is completely unaware of the existence of his companion-to-be on the steppe, yet he has strange dreams of heavy heavenly objects falling beside him. His mother, the goddess Ninsun, interprets these dreams-for Gilgamesh there will come a mighty companion, a man whom he will love as a wife, whom he will caress and embrace (the dreams and interpretations are recorded in I:246-298).

The plot moves forward. Enkidu is introduced to civilization by Shamhat, a prostitute, with whom he has sex for several days and nights (1:188-194). Consequently, he becomes estranged from his animal friends, but learns from Shamhat that he now must follow her to Uruk, to become the new friend of King Gilgamesh (I:197-212). On their way to the city they spend some time at some shepherds' camp, where Enkidu is at first quite bewildered when he is offered prepared food-bread and beer (II:36-62). Here, Enkidu also becomes fully human, guarding the shepherds and their flock, and chasing away the wild animals that would harm them. He and Shamhat proceed to Uruk, but on reaching the city, a fight breaks out between Gilgamesh and Enkidu in the doorway of a wedding house, presumably because Enkidu prevents Gilgamesh from entering and claiming droit de seigneur at wedding ceremonies. However, after the fight, as Ninsun foresaw in her son's dreams, they kiss and form a friendship (II:100-169).7 From this point onwards, Gilgamesh and Enkidu would become inseparable, literally, until "death do them part".

From a narrative point of view and regarding the topic of suffering, the irony in the plot is that Enkidu was created to alleviate the suffering of the people of Uruk, which he has succeeded in doing. Gilgamesh's attention now shifts to Enkidu. However, the attachment to Enkidu would also cause Gilgamesh's deepest suffering-Enkidu's untimely death.

2 Reasons: slaughtering divine beasts

The rest of Tablet II continues to tell of Enkidu's slight depression, apparently because he realises that he has no biological parents, and that he is losing some of his old strength. Subsequently, Gilgamesh suggests that they embark on a death-defying adventure-to slay Humbaba, the monstrous guardian of the divine Cedar Forest, appointed by no one else but the god Enlil. Gilgamesh turns a deaf ear to Enkidu's objections, and the escapade nearly costs them their lives, had Shamash, the sun god not intervened. It appears that Ninsun had prayed to Shamash for the safety of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, and as the two men were staring death in the eyes, the god blinded the monster with tornado-like winds in order to help them overcome him (Tablets III - V).

In Tablet VI, after returning to Uruk, the attractive Gilgamesh catches the eye of Ishtar, the goddess of love(?) and war. She eagerly proposes marriage to him and promises him everything a man can wish for-sex, wealth and power. However, he turns down her offer, reminding her of the cruel ways she treated her former lovers, and implying that the same fate would await him. Livid with rage, Ishtar demands that the Bull of Heaven be sent down to smite Gilgamesh in his palace. Anu, the sky god who is also her father, is hesitant at first, but eventually gives in to her demand. The Bull causes havoc in the city, killing several hundreds of people. Fortunately, Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrive on the scene, and vanquish yet another heavenly beast. Tablet VI ends with Gilgamesh and Enkidu celebrating their victory with the people of Uruk and making much merry in the palace. However, as they lie down to sleep, Enkidu has an ominous dream; he sees the great gods taking counsel.

Tablet VII opens with a lacuna of 26 lines, but Andrew George fills in the gaps with a fragmentary Hittite version of the Epic.8 The gods taking counsel are the highest gods in the pantheon-Anu, Enlil, Ea and Shamash. Anu accuses Gilgamesh and Enkidu of slaying both Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. He therefore says that one of them must die, but why not both of them? The implication is that the two of them were so close and killing them both would not really have a devastating effect. If one dies, however, the other will suffer the rest of his life, mourning the death of his friend. Enlil decides that it is Enkidu who would die.

D HUMAN-DIVINE RELATIONSHIPS

Louise Pryke observes that Mesopotamian narrative literature frequently explores "themes involving mortality and immortality, power and authority, creation and destruction."9 The plot of the narrative is structured by means of relationships and interactions between gods and humans which may be on the one hand mutually rewarding, but on the other hand destructive and damaging. Good relationships between humans and gods are fostered when both parties keep to their deal-divine blessing in response to human obedience. Relationships suffer when humans either neglect their responsibilities to the gods or transgress divine orders. The other side of the coin is when the gods remain silent to human suffering, apparently when the humans do everything, they were supposed to do to maintain good relationships between the "here" and "there." Undeserved calamity inflicted by gods to an obedient supplicant is called "theodicy." Benjamin Clark explores theodicy literature in ancient Mesopotamia and Israel and discusses three texts namely the biblical book of Job, the Babylonian Theodicy and Ludlul Bël Nëmeqi.10

How then do these observations apply to the Epic of Gilgamesh?

In Enkidu's dream, the relationships and interactions between humans and deities are particularly destructive and damaging. They are not innocent sufferers. They transgressed their human boundaries by killing off two heavenly beasts. One may add that Gilgamesh has insulted a goddess by a very impolite rejection of her proposal. Of course, they deserve some punishment.

However, the gods are also not without blame. Before Gilgamesh and Enkidu embark on the journey to the Cedar Forest, Ninsun prays to Shamash to protect them, but her plea is somewhat an accusation. Ninsun asks Shamash (III:46-48; 53-54):

46 Why did you assign (and) inflict a restless spirit on [my] son Gilgamesh?

47 For now you have touched him, and he will travel

48 the distant path to where Humbaba is.

53 until he slays ferocious Humbaba,

54 and annihilates from the land the Evil Thing that you hate, Thus, the slaying of Humbaba may be of divine inspiration.

Likewise, Gilgamesh rejection of Ishtar's marriage proposal appears to be insulting, but he has good reasons for doing so. He is very well aware of how she had treated her former lovers, one by one condemning them to some unhappy fate. In addition, Tzvi Abusch closely analyses the dialogue between Ishtar and Gilgamesh and significantly observes that Ishtar's proposal does in fact subtly hint towards funeral rites and the netherworld.11 Thus, Ishtar does not propose to Gilgamesh a "marriage made in heaven," on the contrary, she entices him into entering the "house of no return."

Regarding the slaying of the Bull of Heaven, Ishtar is directly to be blamed. She proposes to Gilgamesh, perhaps with some hidden agenda. He senses the ruse, refuses her, and insists that the Bull be sent down to earth, where it then causes the death of several hundreds of people. One may say that Gilgamesh and Enkidu do not act only in self-defence, they also prevent the heavenly monster from killing more humans.

As indicated above, theodicy is commonly understood as undeserved punishment inflicted by a deity, but did Gilgamesh and Enkidu really deserve to be punished for slaying Humbaba and the death of Bull of Heaven? Perhaps their case may be one of theodicy after all, albeit in an 'inverted' manner! Authors Michela Piccin and Martin Worthington analyse the schizophrenic traits of the god Marduk in Ludlul Bël Nëmëqi and in the opening lines of their article they refer to the incident between Gilgamesh and Ishtar, thus, "Among the many cultural puzzles left us by the Akkadian-speaking world, one of the most intriguing is that of how the gods behave, and why."12 Indeed, in the Gilgamesh Epic, the gods appear to be scheming behind each other's backs, and this is evident, especially in Tablet XI, the account of the Deluge.13

E THE DEATH OF ENKIDU

Enkidu knows that he is dying. In Tablet VII, he becomes delirious, probably with fever and fear. He recalls his past, remembering but also cursing everyone that played a role in his life. He has grim visions of the netherworld where he knows that he is heading, and then, towards the end of his life, he cries out, "My god has spurned me!" (VII:263), which may vaguely remind one of Psalm 22. The 1999 translation of George14 indicates that Enkidu wished that he had died in battle, in honour, in order to make an everlasting name. Dying in illness means dying in shame.

The whole of Tablet VIII consists of Gilgamesh's lament for Enkidu. He calls upon all of humanity and nature to mourn his friend, expressing his anguish in harrowing words (VIII:59-64):15

He covered (his) friend, (veiling) his face like a bride,

circling around him like an eagle.

Like a lioness whose cubs (are) in pits,16

he kept turning about, this way and that.

He was pulling out his curly [tresses] and letting them fall in a heap,

tearing off his finery and casting it away, [. . . like] something taboo.

After laying his friend to rest, Gilgamesh vows (VIII:90-91):17 "And I, after you have gone, [I shall have] myself [bear the matted hair of mourning,] I shall don the skin of a [lion] and [go roaming the wild.]"

Gilgamesh prepares a grand burial for Enkidu with plentiful and elaborate gifts to the deities of the netherworld, praying to them that they may welcome his friend favourably. Nevertheless, he cannot be consoled. Tablet IX:1-5 opens:18

For his friend Enkidu Gilgames

was weeping bitterly as he roamed the wild:

"I shall die, and shall I not then be like Enkidu?

Sorrow has entered my heart.

I became afraid of death, so go roaming the wild,

to Uta-napisti, son of Ubär-Tutu ..."

Kathleen Smith19 states that:

Grieving people often feel that they have lost their sense of safety and control in life, and they find themselves panicking or worrying excessively about what or whom else they could lose in the future. They also may have trouble sleeping or taking care of themselves, which can put them at higher risk for anxiety.

Grief after some form of personal loss is normal but grieving that continues for a prolonged and indefinite time, for example, for more than six months after a loss, results in what Smith20 calls complicated grief. This is a serious anxiety disorder that also interferes with everyday life activities. Excessive worry and specific phobias and panic attacks are some of the symptoms listed by Smith.

Gilgamesh seems to be a classic example of "complicated grief." He ceases to take care of himself; he rips out his hair, tears off his fine clothes and dons the skin of a lion. His mind is focused on death; his panic, his phobia of death prevents him from carrying on his duties as king of the city Uruk. He leaves his city and his palace and goes roaming in the wild. He is afraid that he may die and become like Enkidu, but quite ironically, he now becomes exactly like Enkidu whilst he is still wild and untamed.21 However, unlike Enkidu who, presumably like all animals, was unaware and therefore unafraid of Death, Gilgamesh is panic stricken at the very thought of death. He is intensely aware of his mortality, that his days are numbered and that he too, like all humans, will die.

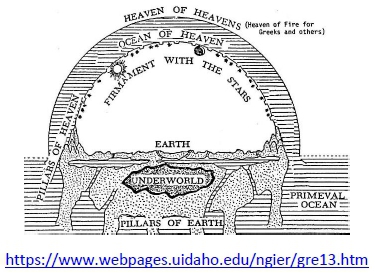

However, there is one man who escaped this final destination and managed to live forever-Uta-napishti, son of Ubar-Tutu. Gilgamesh's obsessive fear of Death drives him to seek and find this man, hoping to learn from him the secret of life everlasting, so that he, Gilgamesh may also live forever. However, Uta-napishti lives beyond the borders of the earth, beyond the Waters of Death that surround it. In order to reach Uta-napishti, Gilgamesh has to travel first to the Twin Mountains at the end of the earth; there, the sun rises and sets every day in crossing its heavenly path by day and travelling through a deep dark tunnel by night. Thereafter he has to cross the Waters of Death to find Uta-napishti, the Distant (see image below).

The Path of the Sun is guarded by fearsome Scorpion People, who seem both surprised and curious on Gilgamesh's arrival. After questioning him, they allow him to travel the Path of the Sun, the part that consists of the dark tunnel below the earth,22 but warn him that no human being had done this before. He must race against time; he must complete the journey and come out at the other end before the sun does. After twelve double-hours of gruelling through thick darkness, Gilgamesh comes out on the other side, and finds himself on the seashore of the Waters of Death, midst a paradise with trees that bear leaves and fruit of semi-precious stones.

Here lives Siduri, the sabitum, commonly translated as "female brewer/alehouse keeper,"23 but she is shrouded in some mystery, as her pot stands appear to be vats of gold, and she is covered in veils.24 When she sees his haggard appearance, she initially mistakes him for someone who may have bad intentions and bars her gates, but Gilgamesh insists on entering and explains his plight (X:46-71):25

Gilgamesh spoke to her, to the ale-wife

Why should my cheeks not be hollow, my face not sunken,

my mood not wretched, my features not wasted?

Should there not be sorrow in my heart,

and my face not be like one who has travelled a distant road?

Should my face not be burnt by frost and sunshine

and should I not roam the wild got up like a lion?

My friend, a mule on the run

donkey of the uplands, panther of the wild,

My friend Enkidu, a mule on the run,

donkey of the uplands, panther of the wild,

my friend whom I love so deeply,

who with me went through every danger:

the doom of mankind overtook him,

for six days and seven nights I wept over him.

I did not give him up for burial,26

until a maggot fell from his nostril.

Then I was afraid ...

I grew fearful of death, and so roam the wild.

The case of my friend was too much for me to bear

so on a distant road I roam the wild.

The case of my friend Enkidu was too much for me to bear,

so on a distant path I roam the wild.

For how could I stay silent? How could I stay quiet?

My friend whom I live, has turned to clay,

my friend Enkidu whom I love, has turned to clay.

Shall not I be like him and also lie down,

never to rise again, through all eternity?

Without hesitating, he asks for directions to Uta-napishtim, and although Siduri warns him about the dangers, she directs him to Ur-shanabi, Uta-napishtim's boatsman. He and his strange companions, the Stone Ones (who seem to play a role in ferrying the boat across the Waters of Death) are stripping a cedar amidst the forest. Gilgamesh takes the boatsman by surprise and smashes the Stone Ones. However, just like Siduri, Ur-shanabi notices Gilgamesh's worn appearance, and asks questions. To the boatsman, Gilgamesh also repeats his lament (X:119-148) in exactly the same words he addressed to Siduri (see above), demanding that Ur-shanabi ferries him across the Waters of Death. The boatsman agrees, but Gilgamesh has to compensate him for smashing the Stone Ones by cutting three hundred punting poles to help them cross the primeval ocean.

At last, Gilgamesh reaches what is seemingly his goal. Like Siduri, and like Ur-shanabi, this mortal who has managed to live forever, asks questions about Gilgamesh's run-down looks, and Gilgamesh once again provides the same answer (X:219-248). It is important to note that this heart-rending lament occurs three times in Tablet X, but before discussing suffering and trauma within the lament itself, a brief synopsis of the rest of the plot may be informative.

Uta-napishtim agrees to disclose to Gilgamesh how he managed to be the sole survivor of a great Deluge, and how the gods have blessed him with everlasting life (see fn. 13 above for the plot). However, for Gilgamesh, there will not be another Deluge; the only way for him to obtain life everlasting would be if he succeeds in staying awake for six days and seven nights. Needless to say, Gilgamesh fails this test miserably. Uta-napishtim instructs Urshanabi to take Gilgamesh back to where he came from, to Uruk. However, his wife persuades him to give their weary guest a parting gift-a shrub that grows on the bottom of the ocean that also has rejuvenating capacities: whoever eats from it, will never grow older. Gilgamesh retrieves the plant but decides to try it out first on the senior citizens of Uruk. As he and Urshanabi break camp for the night, he goes for a dip in a pool of cool water, leaving rather carelessly the precious plant unguarded. A snake is lured by its sweet odours, and as Gilgamesh comes out of the water, he is just in time to see the creature snatch away the plant, sloughing its old skin and sailing away young and new. Gilgamesh breaks down and cries. All his efforts are in vain.

Gilgamesh returns with Urshanabi to Uruk and is speaking from its walls to the boatsman in exactly the same words of the opening lines of the Epic. However, he is now addressing Urshanabi, boasting about the splendour of the city and its surroundings (XI:322-328).27 He does not appear to be depressed or downcast. On the contrary, he seems to be composed and rather proud. He may have realised at last that no human being, regardless of how strong or powerful he is, can live forever, but, as Andrew George concludes, "there will always be men on this earth, for life itself is eternal.28 And in Gilgamesh the interest is in the living."29

F TRAUMA AND SUFFERING

As noted above (fn. 25), Tzvi Abusch compares the Old Babylonian Version of the Epic to the Standard Babylonian one. For the purpose of this article, his literary analysis of the differences between the two texts is not important, but his observations on Gilgamesh's anguish are. Here the insertion in the Old Babylonian Version of Gilgamesh's cry that his friend may wake up and speak to him, is significant. Abusch notices that the rhythm of the poem itself appears to be "broken and tense,"30 thereby reflecting Gilgamesh's distressed mood. Furthermore, the cry that Enkidu may wake up is of course unrealistic, even delusional. The stark reality, which is also documented in the Standard Epic, is that after several days, a maggot dropped from Enkidu's nose. In other words, the body has reached some stage of decay, before Gilgamesh accepts that his friend is dead.

Furthermore, Enkidu should have been buried much earlier. Burial practices in the ancient Near East demanded that a body be buried as soon as possible after death, only then a period of mourning, perhaps seven days would follow. In fact, says Abusch,31 Gilgamesh reverses the burial and mourning rites, and even worse, instead of honouring his friend, he dishonours him in a rather gross manner, by leaving the body to decompose and to become infested by maggots.

Gilgamesh appears delusional, ridden by chaotic thoughts and behaviour that persist for several days. Emotionally, he has disintegrated completely; his "state of mind is one of confusion and disorder, and his grasp on reality is weakened."32

Now, because he fails to accept Enkidu's death and bury him in time, he starts to fear his own death. He cannot face the reality that he is fragile, finite, and will die like all other human beings.

These "recurring intrusive memories regarding Enkidu's death" and the asking of "numerous questions regarding his own death," are according to scholars Tomasz Kucmin, Adriana Kucmin, Adam Nogalski, Sebastian Sojczuk and Mariusz Jojczuk typical symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).33 Their article provides an overview of this very human condition and the ways it has been expressed through various literary works since antiquity. They mainly focus on victims of war. Unfortunately, they assume incorrectly that Gilgamesh was a "legendary king of Uruk whose companion Enkidu was killed in battle and died a violent death".34 In fact, quite the opposite happens, Enkidu dies of some painful ailment. However, one may agree with them that Gilgamesh does seem to suffer from PTSD, given the ways that his thoughts and behaviour are described in the Epic. Their observations also concur with an online article that refers to "unresolved grief," that is "a grief experience which takes longer than what is common for a person's social or cultural background."35Anxiety, irritability, depression and other emotional disturbances are all symptoms of prolonged grief over the loss of a beloved.

Most articles on grief, bereavement, suffering after loss of someone or something, may indicate the same symptoms, and all would be appropriate to describe Gilgamesh's situation. He loves his friend deeply. He could not accept and come to terms with his death. His grief exceeds the normal period of mourning. Consequently, he develops an obsessive fear of dying himself, but also to having delusions that there must be a possibility for him to live forever. Irrational thoughts and behaviour are all part of prolonged suffering and grief, long before these symptoms were diagnosed clinically and treatment was made available. At the end of the Epic, however, Gilgamesh seems to have found quiescence.

In this regard, Elizabeth Kübler-Ross' five stages of grief may be illuminative.

G ELIZABETH ROSS' FIVE STAGES OF GRIEF AND THE EPIC OF GILGAMESH

Two articles aim to appropriate Elizabeth Kübler-Ross' five stages of grief to the Gilgamesh Epic but either the scenarios do not quite apply to the stages of grief36or the references to particular anecdotes are incorrect.37 In this article, I propose that the five stages be applied as follow:

• Denial: Gilgamesh first experiences the denial of Enkidu's death. Thereafter he starts to deny his own mortality and goes in search of life everlasting.

• Depression: He is clad in the skin of a lion, neglects his personal appearance, and roams the plains in search of life everlasting.

• Anger: His fear of death and obsession to find the secret to everlasting life cause him to threaten to strike Siduri's door and break the bolt if she does not let him in (X:22). Anger and his fervency to cross the Waters of Death may also have driven him towards overcoming Urshanabi and smashing the Stone Ones (X:92-206).

• Bargaining: The whole encounter with Uta-napishtim seems to be marked by bargaining. He learns that there will not be a second Deluge for him, then accepts the impossible challenge of staying awake for six days and seven nights. The retrieving of the rejuvenating plant at the bottom of the ocean is his last chance.

• Acceptance: After the snake snatches the plant, he realises that he cannot escape his own mortality. He returns to Uruk, standing on "the walls that will be his enduring monument."38 Gilgamesh comes to the "cruel realization of his own mortal inadequacy. And aware at last of his own capabilities he becomes reconciled to his lot, and wise."39

Scholars like Jeffrey Tigay and Anthony Westenberg40 agree that Gilgamesh ultimately learns to accept his mortality instead of wasting the rest of his life in his vain struggle against death. As Tigay observes, Gilgamesh has not completely given up on immortality, but it is immortality that is imbedded in life itself. He accepts that he must die, like all human beings, but consequently strives to establish for himself the immortal name of a good king. The opening lines of the Epic attest to Gilgamesh's interests in Uruk; Tablet XI ends with his own testimony of the pride he takes in his city to Urshanabi. Eventually, his investment in Uruk and his performance as a good king will bring him the immortality and fame that he had hoped for.

H CONCLUSION

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest extant text that can be described as a "literary composition", that is, a text with an interest in humanity. The main characters are not deities, and the topic is not creation or overcoming chaos. The main character is Gilgamesh whose whole life is transformed first by the coming of his friend, Enkidu, and then by Enkidu's tragic death. A suffering Gilgamesh exhibits symptoms and behaviour which are only millennia later described and diagnosed in clinical terminology that are used today. Furthermore, it seems that Gilgamesh also progressed through the "five stages of grief" determined by Elizabeth Kubler Ross. It may be observed that suffering, trauma and grief are as old as humanity itself, and fate that causes devastating loss cannot be avoided. As Westenberg concludes, The Gilgamesh Epic is:

... a story of how a man comes to accept his mortality. The epic shows this through the repetition of the opening lines, and through its concurrent theme that to struggle against mortality and fate is a poor decision, one that causes harm to those around Gilgamesh and causes him to suffer. Mortality within the modern mindset is thus something against which humanity can fight, and one's fate is something that one can, and perhaps should, seek to change.41

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abusch, Tzvi. "Ishtar's Proposal and Gilgamesh's Refusal: An Interpretation of 'The Gilgamesh Epic', Tablet 6, Lines 1-79." History of Religions 26/2 (1986): 143187. [ Links ]

Abusch, Tzvi. "Gilgamesh's Request and Siduri's Denial. Part II. An Analysis and Interpretation of an Old Babylonian Fragment about Mourning and Celebration." Journal of the Ancient near Eastern Society. (1993): 3-19. Online: janes.scholasticahq.com. [ Links ]

Abusch, Tzvi. "The Development and Meaning of the Epic of Gilgamesh. An Interpretative Essay." Journal of the American Oriental Society 121/4 (2001): 614-622. Online: https://www.jstor.org . [ Links ]

Black, Jeremy, Andrew George, Nicolas Postgate, eds. A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian. 2nd (corrected) printing. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2000. [ Links ]

Clarke, Benjamin. "Misery Loves Company: A Comparative Analysis of Theodicy Literature in Ancient Mesopotamia and Israel. " Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 2/1 (2010): 77-92. Online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol2/iss1/5 . [ Links ]

Dickson, Keith. "Looking at the Other in Gilgamesh." Journal of the American Oriental Society 127/2 (2007): 171-182. [ Links ]

George, Andrew R. The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation. Suffolk: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1999. [ Links ]

George, Andrew R. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic. Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Tests. Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Kucmin, Tomasz, Adriana Kucmin, Adam Nogalski, Sebastian Sojczuk, Mariusz Jojczuk. "History of Trauma and Posttraumatic Disorders in Literature. " Psychiatry Pol. 2016 50(1): 269-281. Online www.psychiatriapolska.pl; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12740/PP/43039. [ Links ]

Piccin, Michela and Martin Worthington. "Schizophrenia and the Problem of Suffering in the Ludlul Hymn to Marduk." Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 109/1 (2015): 113-124. [ Links ]

Pryke, Louise. "Religion and Humanity in Mesopotamian Myth and Epic. " No Pages. Cited 2020. Cited on 05/05/2020. Online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.247 . [ Links ]

Smith, Kathleen. "Grief and Anxiety." No Pages. Cited on 05/05/2020.Online: https://www.psycom.net/anxiety-complicated-grief/ 2019. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Michael. The Life of a Poem: Gilgamesh. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019. [ Links ]

Tigay, Jeffrey H. The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982. [ Links ]

Westenberg, Anthony. "Fate and Mortality in the Epic of Gilgamesh. " No Pages. Cited 22 April 2020. Online: https://www.academia.edu/9233304/Fate_and_Mortality_in_the_Epic_of_Gilgamesh?email_work_card=view-paper. Internet sources - no author [ Links ]

"The Physical Symptoms of Grief." n.p. https://obittree.com/funeral-advice/grief-articles/physical-grief-symptoms.php. Last edited 2016. "Gilgamesh and the Five Stages of Grief." n.p. https://quizlet.com/95009728/gilgamesh-and-the-five-stages-of-grief-flash-cards/. [ Links ]

"Kübler-Ross' Stages of Grief in Job and Gilgamesh." n.p. https://writer.tools/subjects/p/psychology/kubler-ross-stages-of-grief. [ Links ] .

Submitted: 09/11/2020

Peer-reviewed: 02/12/2020

Accepted: 04/12/2020

Dr Gerda de Villiers. Department of Old Testament and Hebrew of Scriptures, Faculty of Theology and Religion. University of Pretoria. E-mail: gerdadev@mweb.co.za. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4391-8722.

1 Andrew R. George, The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation (Suffolk: Barnes & Noble, 1999), xxiii.

2 Andrew R. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic. Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Tests (vol. I Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 33. See also Tzvi Abusch, "The Development and Meaning of the Epic of Gilgamesh: An Interpretative Essay," Journal of the American Oriental Society 121/4 (2001): 614-622 (614) Online: https://www.jstor.org.

3 Michael Schmidt, The Life of a Poem: Gilgamesh (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 38.

4 The Old Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic has also been reconstructed. The plot is like the Standard Version, but with some omissions and some editions which are significant. Abusch, "The Development and Meaning," 614-622 discusses three versions of the Epic namely, the Old Babylonain Version, The Standard Babylonian Version ending with Tablet XI, and the Standard Babylonian Version with the addition of Tablet XII. He notes the added passages in each version and indicates significant interpretative shifts.

5 George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic.

6 The nature of the tyranny is not clear and may include forced labour, athletic contests, wrestling games, sexual harassment. See George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, 449.

7 George, Epic of Gilgamesh, 12-17 fills in the lacunae of the Standard Babylonian Version in with fragments of other tablets.

8 George, Epic of Gilgamesh, 54-55.

9 Louise Pryke, "Religion and Humanity in Mesopotamian Myth and Epic," Online publication, August 2016, n.p. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.247.

10 Benjamin Clarke, "Misery Loves Company: A Comparative Analysis of Theodicy Literature in Ancient Mesopotamia and Israel," Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 2/1 (2010): 77-92 (79), https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol2/iss1/5.

11 Tzvi Abusch, "Ishtar's Proposal and Gilgamesh's Refusal: An Interpretation of 'The Gilgamesh Epic', Tablet 6, Lines 1-79," History of Religions 26/2 (1986): 148161.

12 Michela Piccin and Martin Worthington, "Schizophrenia and the Problem of Suffering in the Ludlul Hymn to Marduk," Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 109/1 (2015): 113.

13 The gods decide to wipe out all of humanity with a Flood. The god Ea discloses this divine secret to a mortal, Utanapishtim and instructs him to build a boat. Utanapishtim survives the Deluge, but Enlil is overcome with rage; no human being should have escaped. Ea keeps silent about his doings, and instead claims that Atrahasis (Utanapishtim) has a dream. Whereupon Enlil is so impressed that he blesses Utanapishtim and his wife with everlasting life.

14 George, Epic of Gilgamesh, 62.

15 George, Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, 655, 657.

16 Ibid., 657, fn. 11.

17 Ibid., 657.

18 Ibid., 667.

19 Kathleen Smith, "Grief and Anxiety," (2019): n.p. Online: https://www.psycom.net/anxiety-complicated-grief/.

20 Smith, "Grief and Anxiety."

21 Keith Dickson, "Looking at the Other in Gilgamesh," JAOS 127/2 (2007): 177 -179.

22 That part unfortunately cannot be seen in the image above.

23 Jeremy Black, Andrew George and Nicolas Postgate, eds., A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian (2nd corrected printing; Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2000), 390.

24 George, Epic of Gilgamesh, 76.

25 George, Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, 681, 683.

26 Here Tzvi Abush draws attention to an additional line in the Old Babylonian Version which is omitted in the Standard Babylonian version, (saying) "my friend perhaps will rise up to me and cry ..." Tzvi Abusch, "Gilgamesh's Request and Siduri's Denial. Part II. An Analysis and Interpretation of an Old Babylonian Fragment about Mourning and Celebration," Journal of the Ancient near Eastern Society (1993): 3-19, 7. The significance of this line will be discussed later in the article.

27 George, Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, 725.

28 Ibid., 528.

29 Ibid., 526.

30 Abusch, "Gilgamesh's Request," 6.

31 Ibid.," 8.

32 Ibid.," 10.

33 Tomasz Kucmin, Adriana Kucmin, Adam Nogalski, Sebastian Sojczuk and Mariusz Jojczuk, "History of Trauma and Posttraumatic Disorders in Literature," Psychiatry. Pol. 50/1 (2016): 269-281, DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12740/PP/43039.

34 Kucmin, et al., "History of Trauma," 271.

35 No author, "The Physical Symptoms of Grief," n.p., https://obittree.com/funeral-advice/grief-articles/physical-grief-symptoms.php, last edited 2016.

36 No author, "Gilgamesh and the Five Stages of Grief," n.p., https://quizlet.com/95009728/gilgamesh-and-the-five-stages-of-grief-flash-cards/.

37 No author, "Kübler-Ross' Stages of Grief in Job and Gilgamesh," n.p., https://writer.tools/subjects/p/psychology/kubler-ross-stages-of-grief.

38 George, Gilgamesh Epic, 88.

39 Ibid. , xlvi.

40 Jeffrey H. Tigay, The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982), 249-250; Anthony Westenberg, "Fate and Mortality in the Epic of Gilgamesh." https://www.academia.edu/9233304/Fate_and_Mortality_in_the_Epic_of_Gilgamesh?email_work_card=view-paper.

41 Westenberg, 2020, n.p.