Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.33 no.3 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2020/v33n3a9

PART I: GENERAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Inner-biblical Quotations in Old Testament Narratives: Some Methodological Considerations (e.g., 1 Sam 15:2 and Deut 25:17-19)

Carsten Vang

Fjellhaug International University College

ABSTRACT

In the study of inner-biblical quotations in Old Testament narrative literature, much insight can be gleaned from the scholarly endeavour in the last twenty years of defining and interpreting allusions and quotations in the prophetic literature. Author-intended quotations from a precursor text should be distinguished from stock phrases and the use of recurrent identical phrases. Among the viable criteria for discerning the direction of dependence in quotations, it is relevant to mention unfamiliar language usage in one part of the parallel, dependence on context, and signs of interpretation for rhetorical purposes. These criteria are used to test the case of the parallel locutions in Deut 25:17-19 and 1 Sam 15:2-3. The article also stresses the need for a thorough study of repeated phraseology in the narrative literature.

Keywords: Direction of Dependence, Formulaic Language, Method, Quotation, Verbal Parallels

A INTRODUCTION

Many Old Testament narratives contain several literary parallels to other narratives and legal texts in the Pentateuch. The textual parallels to the Pentateuch cover a considerable range from long quotations of several phrases (e.g., 2 Kgs 14:6) by more or less obvious allusions to using a particular distinctive phraseology recurring in certain narrative texts. This article1 addresses the issue of studying the literary and textual connections between narrative texts in the Old Testament and legal texts in the Pentateuch in order to understand the literary relationship between them and the rhetorical function of the parallels. It will not deal with the Book of Chronicles' extensive reuse of written traditions from the Pentateuch, Samuel-Kings and Psalms. Literary parallels in the narratives that are only thematic and do not also have a shared textual string, also fall outside the scope of this study.

This article will address the issue of terminology in studying textual parallels. It will consider the question of how to distinguish between author-intended textual parallels where an author reuses textual elements from an earlier source, and shared locutions that are simply random. When the reader has established that to all appearances a perceived parallel is author-intended and intends to draw him or her to the other text, the question arises, what criteria do we have to determine the direction of dependence in textual parallels in the narratives? A related question concerns how to assess the phenomenon of shared phraseology in the narratives and Pentateuch that consists of recurrent use of a specific set of phrases and themes, disclosing a stylistic and conceptual relatedness.

B 1 SAM 15:2-3

1 Sam 15:2-3 provides us with an example of an obvious literary connection between a narrative and a legal text in the Pentateuch.

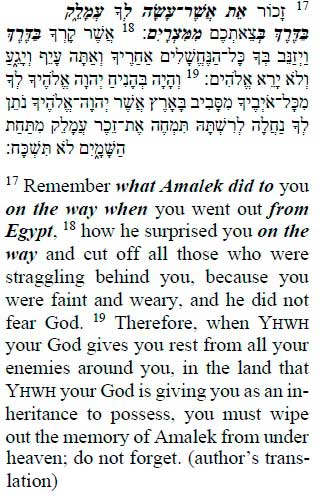

1 Sam 15:2-32

Deut 25:17-19

In 1 Sam 15 the old prophet Samuel approaches king Saul and commands him in a very solemn manner to put the Amalekites under a complete ban. The reason for this harsh procedure is stated only in very general terms in v. 2 ("what Amalek did to Israel while en route from Egypt").4 Saul/the readers are expected to recognise and understand the veiled reference to a critical episode in the Am-alekite-Israelite interrelationship that goes back to Israel's very beginning as a people having experienced a recent liberation from slavery. In Deut 25:17-19 the atrocities of Amalek are described in detail, how they attacked the Israelite rearguard in a most unethical manner.

Several shared locutions can be observed between 1 Sam 15:2-3 and Deut 25:17-19: The particular phrase את אֲשֶר־עָשָה עֲמָ לק לְ ("what Amalek did to you") is common to both,5 the episode happened בַדֶרֶךְ ("on the way"), and in both instances, the attack is set in relation to Israel's exodus from Egypt and it is phrased in a similar manner (בְ... מִּמִּצְרָיִּם). On the thematic level also, there is considerable overlap.6 The structural order of grounds followed by a command is identical for both parts of the parallel.7

There appears to be a specific literary relationship between those two texts in particular.8 The big question is: Who is alluding to whom? Is Samuel quoting phrases from the Amalekite Law in Deut 25:17-19? From the canonical order of the books, many readers and some scholars would subscribe to that interpreta-tion.9 The question, however, ought to be raised: Are there any literary indications in the texts that would support such an urge? Could it be the other way around that the Amalekite law in Deut 25 has been phrased with 1 Sam 15:2 in view, in order to explain the nebulous reasons in Samuel's command to Saul to perform herem?10Or are the linguistic and thematic similarities between our two passages due rather to a shared Deuteronomistic redaction of both passages,11since most scholars today assume two or several comprehensive Deuterono-mistic redactions of the so-called "Deuteronomistic History"?12

This example illustrates the complexity of assessing conceivable literary parallels in the narrative literature. For many years the Old Testament guild has witnessed numerous intertextual studies on the prophets. The studies have focused on the textual and thematic relationship between various prophetic corpora13 or on textual links between the prophets and Pentateuchal texts.14 The reuse of texts and traditions in the Book of Psalms has also commanded scholars' attention for years.15

When it comes to OT narratives, studies mainly focus on similarities in plot and literary structure to argue for literary dependence.16 However, only a few literary studies have been done to study repetitions in the narratives of verbal locutions and phrases from other texts.17 To my knowledge, there has been only a slight discussion of the particular challenge of how to make a distinction between proper textual allusions to earlier traditions and the occurrence of distinctive repetitive phraseology in the narrative texts.18 The challenge of defining the direction of dependence in textual parallels that appear allusive, has not been addressed either.

For several years, I have studied the shared locutions and themes in the books of Hosea and Deuteronomy.19 By focusing on locutions being peculiar and distinct for Hosea and Deuteronomy, I have looked for literary signs in both parts of the verbal parallels and their contexts that that may suggest who is quoting whom. A meticulous and methodological rigorous study of the parallels seems to show that in his judgment oracles Hosea is reusing an authoritative Deutero-nomic tradition with a particular rhetorical aim. I hope that a few of the methodological considerations from the study of Hosea's literary relationship to Deuteronomy may prove useful also for considering literary links in the narrative literature.

C THE PROBLEM OF PROPER TERMINOLOGY

In the scholarly literature exploring the various forms of literary relationship between Old Testament texts, the terminology is often confusing. In a clear and well-argued overview article about "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research," Geoffrey Miller has argued that for the sake of clarity the term "intertextuality" should be reserved for reader-oriented studies only, while literary studies scrutinising a given text's dependence on and relation to precursor texts should be labelled differently.20 Miller suggests that we use terms like "inner-biblical exegesis" and "inner-biblical allusion" for literary studies concerning a biblical author's reuse of phrases taken from precursor texts.21

Among the most common literary terms being used in the literature are terms such as "inner-biblical exegesis,"22 "inner-biblical quotation,"23 and "inner-biblical allusion."24

In ordinary language usage, however, "exegesis" stands for explaining the meaning of a text. "Inner-biblical exegesis" therefore hardly covers the reuse and adaptation of verbal elements taken from older texts and traditions.25 The terms "quotation" and "allusion" are more appropriate here, and they are often used interchangeably in the literature. What one scholar terms "allusion," another prefers to label as "quotation." The fact that the term "allusion" not only covers the hidden reuse of locutions taken from another textual source, but also may refer to persons and events where no verbal parallel can be discerned in the texts, means that I find it most satisfying to go with Richard Schultz's definitions and to speak of "inner-biblical quotations'" Schultz defines a quotation as an author-intended repetition of interconnected words from another text "in which an exe-getical purpose in reusing earlier material can be demonstrated or where an understanding of the earlier text and context is helpful, if not essential, for a proper interpretation of the new text."26 Schultz here emphasises the functional aspects of quotation and points out that the literary context of the shared locutions is crucial for the interpretation and evaluation of the quotation.

What makes quotation differ from allusion is not the extent of shared locutions in the verbal parallel, but that allusion may cover many other referential phenomena that do not show up in shared locutions. Thus, allusion is a broader literary term than quotation. Schultz rightly stresses the functional aspects of quotation: The inner-biblical quotation is more than a random repetition of phrases from another source. It is more than an unconscious echo of a certain text or repetition of characteristic phraseology from a particular theological tradition. Quotation means that an author purposefully draws upon an earlier text and reuses it in order to add to his message. Quotation has the power to activate the listener or reader when he/she recognises the quotation, and it makes the context of the precursor text ring in the background and adds to the interpretation of the quoting text.

D TYPES OF SHARED LOCUTIONS AND INTENDED QUOTATIONS

When studying inner-biblical quotations like 1 Sam 15:2-3 and Deut 25:17-19, it is crucial to have transparent criteria for differentiating between verbal parallels that are random, and parallels that are due to author-intended reuse of locutions taken from a particular source. Every language has a certain pool of stock phrases available.27 Two accounts that deal with similar topics will also share locutions to a certain degree. The consideration of cultic issues in the biblical texts naturally will result in many cases of shared expressions that are not due to an allusive literary adaptation of textual elements from an earlier priestly source.28 The use of similar metaphors will likewise result in degrees of similar language and phrases, without this necessarily being a case of literary dependence.29

There are other verbal parallels that do not display the distinctive referential character that quotations have, as in the many instances of recurrent phraseology in certain narratives. For example, the continuing phrase הָעִּיר )הַבַיִּת( אֲשֶר בָחַרְתִּי לִּי לָשוּם שְמִּי שָם("the city [house] that I have chosen to put my name there") in the Book of Kings30 has a very close verbal equivalent in the so-called centralisation formula הַמָקוֹם אֲשֶר־יִּבְחַר יְהוָה אֱלֹ היכֶם מִּכָל־שִּבְ טיכֶם לָשוּם אֶת־שְמוֹ שָם לְשִּכְנ וֹ ("the place that Yhwh your God will choose to put his name there") in Deut 12:5 and passim.31 Another example is the characteristic hymnic locution יְהוָה הוּאהָאֱלֹהִּים בַשָמַיִּם מִּמַעַל וְעַל־הָאָרֶץ מִּתָחַת ("YHWH he is the God in the heavens above and on the earth below"; Deut 4:39) that is repeated verbatim in Rahab's mouth in Josh 2:11 and in Solomon's prayer in 1 Kgs 8:23; or the typical idiom לאֹּ־נָפַל דָבָר מִּכֹּל הַדָבָר הַטּוֹב אֲשֶר־דִּבֶר יְהוָה ("no word fell down from all the good word that Yhwh had spoken") (Josh 21:45; 23:14; 1 Kgs 8:56).

These examples of shared phrases32 are not to be explained as quotations and reuses of textual elements from earlier texts, but as examples of formulaic expressions from a certain theological mindset. The verbal convergence may be extensive; however, the shared phrases do not function as a quotation from a particular phrase in a precursor text (Deuteronomy) and its context. While a quotation directs the reader (when it is recognised) back to an earlier source and activates this particular text and its context in the mental process of reading or hearing, the reuse of recurring phrases in the narratives do not have that function.

In the scholarly debate, two different explanations have been given for the phenomenon of recurrent phrases with a particular Deuteronomic affinity: 1) A certain literary "Deuteronomic" style existed in Ancient Israel for several centuries, parallel to e.g. Assyria where a particular literary style with recurrent phraseology was used for centuries33; 2) a "Deuteronomistic school" has subjected the narratives to two or several redactions in a particular literary repetitive style.34

How is it possible then to distinguish true inner-biblical quotation from recurrent theological phrases that are due to a certain literary style? Several criteria can be applied here. The most important criterion is that the words in the shared locution should be found in a similar syntactical construction, and that the parallel should be distinctive for the two texts in question. It, therefore, concerns the syntactical relatedness and distinctiveness of the verbal parallel.35 The occurrences of two or several shared words in two texts that do not appear in a similar syntactical relation are not indicative of a quotation. The observance of identical, but isolated words cannot qualify for literary dependence.36 Next, a verbal parallel that is distinctive to the two texts in question has a greater likelihood of being a conscious quotation than a verbal parallel found in several biblical books.

Forming an assessment based on these criteria, the opening example from 1 Sam 15:2-3 and the Amalekite law in Deuteronomy appears to constitute an example of inner-biblical quotation. The shared locution is phrased in a syntactically similar manner, only with context-bounded modifications, other shared words are used in a similar manner in the parallel, and the parallel is distinctive and not found outside the two texts. Add to this that the structural order with grounds followed by a command is identical for the two texts.

Schultz and Lyons add a further criterion;37 if one part of the verbal parallel contains signs of reinterpretation or shows an awareness of the context of the other part of the parallel, it is indicative of a purposeful reuse of this string of phrases. Formulaic language and verbal imitation, on the other hand, do not require knowledge of the context of the parallel locution(s) in order to be comprehended in full. Suppose one part of the parallel shows signs of having used the other part for its own rhetorical purpose, or the context of the quoted text adds to the interpretation of the quoting text. In that case, a referential quotation seems to be in place. In our example above, Samuel's command to Saul contains hints of a reinterpretation of the Deuteronomic admonition to remember the Am-alekite atrocities and to blot out any remembrance of Amalek. The verbal parallel here seems to be a quotation.

In the scholarly debate about criteria for identifying inner-biblical quotation (and allusion), it is sometimes stated that the sheer accumulation of several shared locutions in a given paragraph indicates a stronger literary connection than the incident of a single or few shared expressions, even if each parallel is not very strong in itself.38

However, many uncertain allusions do not make the probability of quotation more secure. The strength of a cluster of conceivable literary connections between two texts is only as strong as the verbal parallel with the best foundation in the language of the texts. In the words of Schultz, "it is important to point out that multiplying weak parallels may actually reduce the probability" (of the existence of an allusion).39 If the evidence for quotation is ambiguous even for the verbal parallel with the broadest verbal overlap, the accumulation of several weaker possible allusions will not strengthen the probability of reuse of an older source. One shared locution with reasonable evidence of quotational borrowing is more persuasive than many uncertain parallels.

E CRITERIA FOR ASSESSING THE DIRECTION OF DEPENDENCE

When we have found indications in a verbal parallel that the shared locution is not random, but may be a quotation evoking another text for the reader (or listener), the next question arises: Do we have any literary criteria to determine the direction of dependence in hidden quotations? Are there any guidelines that may help us in assessing whether 1 Sam 15:2-3 or Deut 25:17-19 is the dependent text? This question is important not only for antiquarian reasons. If it is possible to reach a reliable answer, it will also tell us much about the purpose of the quotation.

This question about defining the direction of borrowing is very difficult to answer. It is almost impossible to say anything with confidence about who has reused and reinterpreted whom. The fact that dating the texts is so contested in OT scholarship increases the uncertainty about evaluating the direction of dependence. Besides, some narratives show signs of redaction, e.g. in the so-called Deuteronomistic History. A conscious textual reference to precursor texts may therefore derive from several stages of the textual history.

Scholars often interpret the relationship from a preconceived understanding of the date and provenance of the texts where the parallel is found. The direction of borrowing is assumed on beforehand, often by appealing to some authority within one's own scholarly tradition. The verbal parallels are interpreted in this light, without considering whether there could be any literary clues in the two parallel texts and their contexts that would indicate the line of influence.

This may be illustrated with an example from the study of the literary relationship between the Book of Hosea and Deuteronomy. Scholars who claim that most of Deuteronomy is a covenant-document from before the inauguration of kingship in Israel appeal to a certain cluster of verbal parallels between Hosea and Deuteronomy that (in their view) demonstrate Hosea to be alluding to Deuteronomy through the device of quotation.40 Other scholars working from the assumption that the earliest possible date for Ur-Deuteronomium must be set in the last decades of the Judahite kingdom refer to the same pool of parallel phrases and ideas in order to show that Deuteronomy is dependent on Hosea's preaching and that Hosea is one of the sponsors of the Deuteronomistic movement.41 The same observation of the shared locutions and themes result in contrary conclusions.42

In order to get around the trap of assuming the direction of borrowing from a preconceived theory of the date of the texts, one should make a meticulous study of all literary aspects of the parallel, and in both parts of the parallel one should look for clues of which text is referring to which one. It will be impossible to reach any conclusion in many cases because the literary signs are inconclusive, and the available data may be interpreted from both sides. However, in some verbal parallels, literary indications may guide the scholar.

In the last 25 years, a few students of inner-biblical quotation have begun to address the problem of using proper criteria for assessing the question of direction of dependence.

According to Schultz, if one part of a verbal parallel shows signs of reinterpretation of the other part or application of phraseology from the other part, this may indicate the direction of borrowing. He says, "by making a discriminating use of word statistics and examining evidence of interpretive reworking, one can suggest, at least in terms of degrees of probability, the direction and the nature of the quotation."43

From his study of the literary relationship between Ezekiel and Leviticus 17-26, Michael Lyons has suggested four helpful criteria for evaluating who is dependent on whom44: 1) Modification of the borrowed phrases, i.e. the author of one of the texts has modified the shared material in accordance with his own basic theological understanding. Modifications of the received material are sometimes formal such that locutions appearing separately in one text are conflated in the borrowing text.45 Another option is the so-called "split-up pattern," where a stock phrase is split up in two parallel lines in the borrowing text. 2) Signs of incongruity in the parallel, that is parts of the shared material may be only partly integrated in the new context but be totally incorporated in the context of the other text. The observed incongruity indicates that this part of the parallel is dependent on the other part. 3) Dependence on the context in such a way that the reader must draw in information from the source text in order to comprehend the borrowing text.46 4) Expansions in the borrowing text that interpret the other text. This criterion does not mean that the longer text of a parallel presumably is the dependent text. Rather, if the longer text shows indications of an explanatory and interpretative expansion in relation to the other part of the parallel, this shorter part of the shared locutions is most probably the original one.

This means that in answering the question about the direction of dependence, it is important to pay much attention to the contexts of both parts of the parallel. How do the shared phrases interact with their contexts? Are there signs of reinterpretation?

In my own study of the verbal parallels in Hosea and Deuteronomy, these criteria have proved relevant, in particular Lyons' first three criteria. For example, Hos 13:5-6 appears to be a quotation of textual elements taken from Deut 8:11-14, since Hos 13:5-6 contains Deuteronomic elements, modifies the Deu-teronomic command and is dependent on information in Deut 8. Hos 2:10 apparently quotes Deut 8:13, because a split-up pattern of a Deuteronomic stock phrase can be observed in Hos 2:10b.47

The criteria are not always operational in all cases where a probable author-intended quotation may be observed. Whether they will be equally useful in the narratives remains to be seen.

F QUOTATION IN 1 SAM 15

From these considerations, can we tell anything about who may have reused and reinterpreted whom in the quotational parallel of 1 Sam 15:2-3 and Deut 25:1719? The Book of Kings does contain a longer explicit quotation from Deut 24:16 (in 2 Kgs 14:6). We may add to this several instances where many indirect quotations from Deuteronomy with source reference may be identified in Joshua, Judges and Kings (e.g. Josh 8:31; 10:40; 23:6; Judg 3:4; 1 Kgs 2:3; 8:56). As a point of departure, there are reasons for assuming that the inner-biblical quotations in the Books of Samuel are quotations from Deuteronomy and not vice-versa.48 However, this observation is not decisive. For the direction of influence may not be the same in all cases in a major literary work containing many diverse narratives and textual traditions.

The study of quotational parallels in the Books of Samuel faces a particular challenge: the question of text tradition behind the Samuel part of the parallels. Besides MT and the Septuagint recensions we have three Hebrew Samuel manuscripts from Qumran, where the longer one (4QSama) sometimes supports the LXX against the MT, sometimes goes with the MT against the Greek versions, and sometimes supports neither.49 Therefore, the question of the proper

Hebrew text must be settled before the literary analysis of the parallels can begin. In the case of 1 Sam 15:2, the Masoretic wording is supported by the LXX.50

Several indications in this specific verbal parallel suggest that here it is Samuel who by device of inner-biblical quotation refers Saul (and the readers) to God's command in Deuteronomy and not the other way around. In 1 Sam 15:2, the divine conflict with Amalek is substantiated from a particular event in the remote past. It is what Amalek did to Israel when the people were en route from Egypt. The term ישראל in 15:2 does not refer to the contemporary Israel or to the king's army51 but to their ancestors right after the exodus from Egypt. The suffixes in v. 2b are all 3rd sing. mask., suggesting that Samuel is not referring to the present Israel. In Deut 25:17-18, it is the presumed recipients of the divine call to remember that have had a personal experience with and an immediate memory of the cruel Amalekite attack on them. It is what Amalek did to you, while you were leaving Egypt. All suffixes in v. 17-18 are second singular or plural suffixes, and Israel's deep exhaustion after the exodus experience and several days of walking in a dry desert is personalised ("you were faint and weary"). A quotation in Deut 25 from the wording of 1 Sam 15:2 does not appear feasible.

Deut 25:17 begins with the verb of cognition זכר ("remember") in the inf. abs. (imperative mood) followed by the object clause את אשר־עשה ("what he did"). This is a typical Deuteronomic locution.52 The next locutions are also typical for Deuteronomy, e.g. בדרך בצאתכם ממצרים. 1 Sam 15:2a has not זכר, but פק ד which contain many possible meanings, but with the accusative marker זכר it may mean "observe" or "take to account." This use of פקד is without precedent in Deuteronomy.53 However, sometimes פקד appears in a parallel construction with זכר ("remember") in prophetic texts, always in the sequence זכר-פקד, see Hos 8:13; 9:9 and Jer 14:10. While Deut 25:17-19 urges Israel to remember and never forget what Amalek did, 1 Sam 15 presents God as calling Saul to action because of his active remembrance. Since 1 Sam 15:2 is cast in prophetic mode, it may be seen as a prophetic reinterpretation of the request in Deut 25:17 on the people to "remember."54

1 Sam 15:2 is also very vague as to what happened בדרך after the exodus, and it gives no hint of the assault that could give grounds for the terrible requirement for unrestricted herem on Amalek. The context of Deut 25:17, on the other hand, explains the horrible incident in the Amalekite-Israelite relationship and its effect on Israel then. The unique phrase אשר־שם לו in 1 Sam 15:2 is very vague and ambiguous when read isolated: How can the act of setting oneself up in a position against Israel in order to bar the road (שִּים ל)55 be considered a capital crime many generations later? However, it receives its full meaning and significance when read with the condensed narrative of Deut 25:17-19 as a backdrop. Amalek not only tried to prevent the Israelites from passing through their territory. They attacked the people in a most unethical manner without respecting God's prior redemption of this people. The prophetic call on Saul in 1 Sam 15 for total herem seems to be dependent on the context of Deut 25:17 in order to be comprehensible.

Add to this the use of the Deuteronomic locution נכה וחרם ("strike and put to ban"; Deut 7:2) in 15:3. 1 Sam 15:2-3 combines the quotation from Deut 25:17 with another Deuteronomic locution. When the reader recognises the verbal link to Moses' call to remember, the harsh approach against Amalek becomes understandable. The call on Saul for herem is not due to some recent assaults on Israel (1 Sam 14:48), but to a profound conflict between God and Amalek. The quotation reinforces the command from Deut 25:19 to blot out any remembrance of Amalek. Israel shall not only remember the misdeeds of the Amalekites and act accordingly, but God himself has noticed and will take the desert tribe to account. 1 Sam 15:2-3 reinterprets the demand in Deut 25:17-19 on Israel to remember persistently what Amalek did into a statement of God's active resentment against this Bedouin tribe.

According to Lyons' criterion three, 1 Sam 15:2-3 is dependent on the context of its parallel. 1 Sam 15 has reused the Deuteronomic command of not forgetting what Amalek once did to Israel in order to express God's strong aversion against this people. The quotation from Deuteronomy reinforces the prophetic command to exterminate the tribe. In addition, it suggests that Samuel is speaking in the authority of Moses.56 The comprehension of the inner-biblical quotation in 1 Sam 15:2-3 thus adds several important aspects to the interpretation of 1 Sam 15.57

G VERBAL PARALLELS AS THEOLOGICAL FORMULAIC LANGUAGE

As noted above, the narratives also display many examples of repetitive formulaic language, both in parts of the so-called Deuteronomistic History and in the Book of Chronicles. These verbal parallels are sometimes quite extensive, the syntactical structure of the shared locutions is identical, and the context of the parallels is often analogous. Yet these parallels are not cases of inner-biblical quotation evoking earlier texts. The parallels do not have the characteristics of quotation and allusion.58 The phrases have not been adapted to a new context. The shared phrase is not used in a new or transformed way because of a quotation, and the reader is not referred to an earlier phrase and its context, the recognition of which may enhance the interpretation of the borrowing text as such. The above-mentioned criteria for detecting quotations in the narratives and for assessing the direction of influence and the rhetorical significance of the quotation are therefore not applicable here.

How are we to assess this group of verbal parallels with a particular stylistic and theological affinity taking after the language in, e.g., Deuteronomy? The study of this kind of literary parallels must be different from the study of quotations. Often scholars have settled for referring to lists of typical Deutero-nomic phraseology and taken this as evidence of redactional strands in the nar-ratives.59 My suggestion would be to perform a detailed study of a large body of significant shared locutions in the narratives and to scrutinise the verbal and syntactical similarities on one hand and the subtle differences in vocabulary, syntax, and meaning on the other. As in the study of quotations, it is important to pay close attention to the context of each phrase in common in order to discern possible shifts in meaning and reference. A critical enquiry into the context of each of the parallel phrases may occasionally give a hint of which one of the parallel expressions may be the originator of the phrase.60 Are the shared locutions used indiscriminately over several narrative writings, from Deuteronomy to the Book of Kings, Jeremiah, and later Biblical writings? Or is it possible to identify linguistic developments in the use of the shared locutions? Another critical aspect of the investigation is to pay attention to recurrent phraseology that appears only in certain narratives but not in all literature being related to Deuteronomy.61

As a matter of example, the recurrent phrase in Deuteronomy that Yhwh would choose the proper place of worship to put his name there ( יְהוָה אֱלֹ היכֶםמִּכָל־שִּבְ טיכֶם לָשוּם אֶת־שְמוֹ שָם לְשִּכְנוֹ, Deut 12:5 and par.) is reused several times in Kings and in Jer 7. However, some modification of the shared expression takes place in the Book of Kings, compared with Deuteronomy/Joshua. The grammatical tense shifts from future tense (yiqtol יִּבְחַר, constant in Deuteronomy and Joshua) to past tense (qatal בָחַר, Kings and Chronicles62), and the subject shifts from 3rd person (persistently in Deuteronomy and Joshua) to mostly 1st person: The centralisation and name formula now appear as direct divine speech.63 In Kings and the Book of Nehemiah, the divine choice of the holy place is history. And the term for the chosen place is no longer the indefinite מקום "place," but either עיר "city" or בית "house, temple."64 The same locutions appear to have undergone a clear linguistic development corresponding to the changed historical context.

If something similar can be observed in other shared fixed formulas, the prevailing model of several "Deuteronomistic" redactional strands in the narratives needs to be modified. The thesis that a Deuteronomic style of writing was active for several centuries in Monarchic Israel may better explain the literary evidence.65 Instead of assuming several redactional layers with a Deuterono-mistic theology, we probably should think in different writings being influenced in various ways by Deuteronomy and by its Deuteronomic phraseology.

H CONCLUSION

This article has argued for the necessity of distinguishing between inner-biblical quotations and the incidence of stock expressions that imitate and express a certain theological outlook. The quotation can refer the reader to an earlier text or tradition and activate this precursor text in the reader's mind. The scholarly discussion about feasible criteria to assess the direction of dependence in allusive quotations is also useful for studying quotations in the narrative material. Taking the shared locutions in Deut 25:17-19 and 1 Sam 15:2-3 as an example, the literary evidence suggests that 1 Sam 15 is quoting the Deuteronomic precept in Deut 25:17-19 in order to stress the divine urgency of the call on king Saul. On the other hand, the command on Israel not to forget the Amalekite atrocities in Deut 25:17-19 has not been phrased with 1 Sam 15 in view.

When it comes to the many Deuteronomic formulaic locutions in the narratives, it appears to me that scholarly research till now has neglected a thorough study of the conceivable literary development in the use of the shared phrases.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berges, Ulrich. Die Verwerfung Sauls: Eine thematische Untersuchung. Forschung zur Bibel 61. Würzburg: Echter, 1989. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel I. The NIV Application Commentary: Deuteronomy. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012. [ Links ]

Boda, Mark J. & Michael H. Floyd, eds. Bringing out the Treasure: Inner Biblical Allusion in Zechariah 9-14. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series 370. London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Carr, David. "Method in Determination of Direction of Dependence: An Empirical Test of Criteria Applied to Exodus 34,11-26 and Its Parallels." Pages 107-40 in Gottes Volk am Sinai: Untersuchungen zu Ex 32-34 und Dtn 9-10. Edited by Matthias Köckert & Erhard Blum. Veröffentlichungen der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft für Theologie 18. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2001. [ Links ]

Carr, David M. "The Many Uses of Intertextuality in Biblical Studies: Actual and Potential." Pages 505-35 in Congress Volume Helsinki 2010. Edited by Martti Nissinen. Vetus Testamentum Supplements 148. Leiden: Brill, 2012. [ Links ]

Coniglio, Alessandro. "'Gracious and Merciful is Yhwh...' (Psalm 145:8): The Quotation of Exodus 34:6 in Psalm 145 and Its Role in the Holistic Design of the Psalter." Liber annus Studii Biblici franciscani 67 (2017): 29-50. [ Links ]

Dietrich, Walter. Samuel. Teilband 2: 1 Sam 13-26. Biblischer Kommentar: Altes Testament VIII/2. Neukirchen: Neukirchner Theologie, 2015. [ Links ]

Edelman, Diana V. "Saul's Battle against Amaleq (1 Sam. 15)." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 35 (1985): 71-84. [ Links ]

Edenburg, Cynthia. "How (Not) to Murder a King: Variations on a Theme in 1 Sam 24; 26." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 12/1 (1998): 64-85. [ Links ]

Edenburg, Cynthia. Dismembering the Whole: Composition and Purpose of Judges 1921. AIL 24. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2016. [ Links ]

Eslinger, Lyle. "Inner-Biblical Exegesis and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Question of Category." Vetus Testamentum 42 (1992): 47-58. [ Links ]

Firth, David G. 1 & 2 Samuel. Apollos Old Testament Commentary 8. Nottingham: Apollos, 2009. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Clarendon, 1985. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. "Types of Biblical Intertextuality." Pages 39-44 in Congress Volume: Oslo 1998. Edited by André Lemaire & Magne Saeb0. Vetus Testamentum Supplements 80. Leiden: Brill, 2000. [ Links ]

Fokkelman, J. P. Narrative Art and Poetry in the Books of Samuel. Volume II: The Crossing Fates. Studia Semitica Neerlandica 23. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1986. [ Links ]

Garsiel, Moshe. The First Book of Samuel: A Literary Study of Comparative Structures, Analogies and Parallels. Ramat Gan: Revivim Publishing House, 1985. [ Links ]

Germany, Stephen. "Die Bearbeitung des deuteronomischen Gesetzes im Lichte biblischer Erzählungen," Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 131 (2019), 43-57. [ Links ]

Gertz, Jan C., Berlejung, Angelika, Schmid, Konrad, and Witte, Markus. T&T Clark Handbook of the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Literature, Religion and History of the Old Testament. London: T&T Clark, 2012. [ Links ]

Giercke-Ungermann, Annett. Die Niederlage im Sieg: Eine synchrone und diachrone Untersuchung der Erzählung von 1 Sam 15. Erfurter Theologische Studien 97. Würzburg: Echter, 2010. [ Links ]

Kitchen, Kenneth A. "Ancient Orient, 'Deuteronism,' and the Old Testament." Pages 1 -24 in New Perspectives on the Old Testament. Edited by J. Barton Payne. Waco: Word, 1970. [ Links ]

Klein, Anja. Schriftauslegung im Ezekielbuch: Redaktionsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zu Ez 34-39. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 391. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2008. [ Links ]

Lehnart, Bernhard. Prophet und König im Nordreich Israel: Studien zur sogenannten vorklassischen Prophetie im Nordreich Israel anhand der Samuel-, Elijah- und Elischa-Überlieferungen. Vetus Testamentum Supplements 96. Leiden: Brill, 2003. [ Links ]

Leonard, Jeffery M. "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions: Psalm 78 as a Test Case." Journal of Biblical Literature 127/2 (2008): 241-65. [ Links ]

Levenson, Jon D. Esther. The Old Testament Library. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1997. [ Links ]

Lipton, Diana. "Remembering Amalek: A Positive Biblical Model for Dealing with Negative Scriptural Types." Pages 139-53 in Reading Texts, Seeking Wisdom: Scripture and Theology. Edited by David Ford and Graham Stanton. London: SCM, 2003. [ Links ]

Lohfink, Norbert. "חָרַם häram חרֶם hërem" Pages 180-99 in vol. 5 of Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Edited by G. Johannes Botterweck & Helmer Ring-gren. 16 vols. Translated by David E. Green. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1986. [ Links ]

Lundbom, Jack R. Deuteronomy: A Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013. [ Links ]

Lyons, Michael A. From Law to Prophecy: Ezekiel's Use of the Holiness Code. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 507. New York: T&T Clark, 2009. [ Links ]

Lyons, Michael A. "How Have We Changed? Older and Newer Arguments about the Relationship between Ezekiel and the Holiness Code." Pages 1055-74 in The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Edited by Jan C. Gertz et al. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2/111. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

Mastnjak, Nathan. Deuteronomy and the Emergence of Textual Authority in Jeremiah. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2/87. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

McCarter, P. Kyle. I Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes & Commentary. Anchor Bible 8. Garden City: Doubleday, 1980. [ Links ]

Meek, Russell L. "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology." Biblica 95/2 (2014): 280-91. [ Links ]

Millard, Alan. "King Solomon in His Ancient Context." Pages 30-53 in The Age of Solomon: Scholarship at the Turn of the Millennium. Edited by Lowell K. Handy. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East 11. Leiden: Brill, 1997. [ Links ]

Millard, Alan. "Deuteronomy and Ancient Hebrew History Writing in Light of Ancient Chronicles and Treaties." Pages 3-15 in For Our Good Always: Studies on the Message and Influence of Deuteronomy in Honor of Daniel I. Block. Edited by Jason S. DeRouchie, Jason Gile and Kenneth J. Turner. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2013. [ Links ]

Miller, Geoffrey D. "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research." Currents in Research: Biblical Studies 9/3 (2011): 283-309. [ Links ]

Noble, Paul R. "Esau, Tamar, and Joseph: Criteria for Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions." Vetus Testamentum 52/2 (2002): 219-52. [ Links ]

Nurmela, Risto. Prophets in Dialogue: Inner-Biblical Allusions in Zechariah 1-8 and 9-14. Ábo: Ábo Akademi University Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Nurmela, Risto. The Mouth of the Lord Has Spoken: Inner-Biblical Allusions in the Second and Third Isaiah. Landham: University Press of America, 2006. [ Links ]

Peterson, Brian N. The Authors of the Deuteronomistic History: Locating a Tradition in Ancient Israel. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2014. [ Links ]

Pisano, Stephen. Additions or Omissions in the Books of Samuel: The Significant Pluses and Minuses in the Massoretic, LXX and Qumran Texts. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 57. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1984. [ Links ]

Römer, Thomas C. The So-Called Deuteronomistic History: A Sociological, Historical and Literary Introduction. London: T&T Clark, 2005. [ Links ]

Rom-Shiloni, Dalit. "The Forest and the Trees: The Place of Pentateuchal Materials in Prophecy of the Late Seventh / Early Sixth Centuries BCE." Pages 56-92 in Congress Volume Stellenbosch 2016. Edited by Louis C. Jonker, Gideon R. Kotzé and Christl M. Maier. Vetus Testamentum Supplements 177. Leiden: Brill, 2017. [ Links ]

Rooker, Mark F. "The Use of the Old Testament in the Book of Hosea." Criswell Theological Review 7 (1993): 51-66. [ Links ]

Ross, Jillian L. "A People Heeds not Scripture: A Poetics of Pentateuchal Allusions in the Book of Judges." PhD-diss., Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 2015. [ Links ]

Sarna, Nahum M. "Psalm 89: A Study in Inner Biblical Exegesis." Pages 29-46 in Biblical and Other Studies. Edited by Alexander Altmann. Studies and Texts: Philip W. Lown Institute of Advanced Judaic Studies 1. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963. [ Links ]

Schulmeister, Irene. Israels Befreiung aus Ägypten: Eine Formeluntersuchung zur Theologie des Deuteronomiums. Österreichische Biblische Studien 36. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2010. [ Links ]

Schultz, Richard L. The Search for Quotation: Verbal Parallels in the Prophets. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. Supplement Series 180. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999. [ Links ]

Schultz, Richard L. "Isaianic Intertextuality and Intratextuality as Composition-Historical Indicators: Methodological Challenges in Determining Literary Influence." Pages 33-63 in Bind Up the Testimony: Explorations in the Genesis of the Book of Isaiah. Edited by Daniel I. Block & Richard L. Schultz. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2015. [ Links ]

Seibert, Eric A. "Recent Research on Divine Violence in the Old Testament (with Special Attention to Christian Theological Perspectives." Currents in Biblical Research 15/1 (2016): 8-40. [ Links ]

Snyman, Gerrie. "Intertextuality, story and the Pretense of Permanence of Canon." Old Testament Essays 8/2 (1995): 205-22. [ Links ]

Snyman, Gerrie. "Who is speaking? Intertextuality and Textual Influence." Neotesta-mentica 30/2 (1996): 427-49. [ Links ]

Sommer, Benjamin D. A Prophet Reads Scripture: Allusion in Isaiah 40-66. Contra-versions. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Stern, Philip D. "I Samuel 15: Towards an Ancient View of the War-Herem." Ugaritic Textbook 21 (1989): 413-20. [ Links ]

Stoebe, Hans J. Das erste Buch Samuelis. Kommentar zum Alten Testament VIII 1. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1973. [ Links ]

Tanner, Hans A. Amalek. Der Feind Israels und der Feind Jahwes: Eine Studie zu den Amalektexten im Alten Testament. TVZ Dissertationen. Zurich: TVZ, 2005. [ Links ]

Tsumura, David T. The First Book of Samuel. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007. [ Links ]

Vang, Carsten. "Israel in the Iron-Smelting Furnace? Towards a New Understanding of the כוּר הַבַרְזֶל in Deut 4:20." HIPHIL Novum 1/1 (2014): 25-34. Cited 7 July 2020. Online: https://hiphil.org/index.php/hiphil/article/view/59/34. [ Links ]

Vang, Carsten. "When a Prophet Quotes Moses: On the Relationship between the Book of Hosea and Deuteronomy. " Pages 277-303 in Sepher Torath Mosheh: Studies in the Composition and Interpretation of Deuteronomy. Edited by Daniel I. Block and Richard L. Schultz. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2017. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, Moshe. Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972. [ Links ]

Weyde, Karl W. Prophecy and Teaching: Prophetic Authority, Form Problems, and the Use of Traditions in the Book of Malachi. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alt-testamentliche Wissenschaft 288. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2000. [ Links ]

Weyde, Karl W. "Inner-Biblical Interpretation: Methodological Reflections on the Relationship between Texts in the Hebrew Bible." Svensk Exegetisk Ärsbok 70 (2005): 287-300. [ Links ]

Wolff, Hans Walter. Dodekapropheton 1. Hosea. 4th edition. Biblischer Kommentar: Altes Testament XIV/1. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1990. [ Links ]

Zobel, Konstantin. Prophetie und Deuteronomium: Die Rezeption prophetischer Theologie durch das Deuteronomium. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift fur alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 199. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1992. [ Links ]

Submitted: 22/07/2020

Peer-reviewed: 27/10/2020

Accepted: 12/11/2020

Prof. Carsten Vang, Fjellhaug International University College Aarhus, Katrinebjergvej 75, 8200 Aarhus N, Denmark / Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, University of South Africa, Pretoria. Email: cv@teologi.dk. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7580-137X.

1 An earlier version of this article was read at the Old Testament Narrative Literature Session, Evangelical Theological Society Annual Meeting, San Antonio 11/16/2016.

2 Shared locutions are marked in bold italic.

3 HALOT "פקד."

4 For the theological aspects of the prophetic order, see Eric A. Seibert, "Recent Research on Divine Violence in the Old Testament (with Special Attention to Christian Theological Perspectives)," CBR 15/1 (2016): 8-40; and from a Jewish perspective, see Diana Lipton, "Remembering Amalek: A Positive Biblical Model for Dealing with Negative Scriptural Types," in Reading Texts, Seeking Wisdom: Scripture and Theology (eds. David Ford and Graham Stanton; London: SCM, 2003), 139-153.

5 This shared string of words is found nowhere else in OT.

6 Cf. Hans A. Tanner, Amalek. Der Feind Israels und der Feind Jahwes: Eine Studie zu den Amalektexten im Alten Testament (Zurich: TVZ, 2005), 88: "Dtn 25,17 und 1Sam 15,2 haben nicht nur dasselbe Ereignis im Blick, sondern entsprechen sich auch weitgehend in Wortwahl und Formulierung."

7 Ulrich Berges, Die Verwerfung Sauls: Eine thematische Untersuchung (Würzburg: Echter, 1989), 176.

8 It should be noted in passing that Deut 25:17-19 also has several literary links to Exod 17:8-14. This manifests in the shared locution מחה אֶת־ זכֶר עֲמָ לק מִּתַחַת הַשָמָיִּם "blot out the memory of Amalek from under the heavens" (Ex 17:14 and Deut 25:19) and in the repeated use of the word זכר "remember." However, there appears to be no connections on the textual level between 1 Sam 15 and Exod 17:8-14. Apart from the gentilic nouns "Amalek" and "Israel," there are no shared phrases between Exod 17:8-14 and 1 Sam 15:2-3. When Diana Edelman claims that 1 Sam 15:2-3 "alludes directly to Exod. 17.8-16 and Deut. 25.17-19" (Diana V. Edelman, "Saul's Battle against Amaleq (1 Sam. 15)," JSOT35 [1985]: 75; cf. also Tanner, Amalek. Der Feind Israels, 88). This, however, does not apply to Ex 17:8-16 as there is no textual basis for her statement that 1 Sam 15:2 is alluding in the same manner to Exod 17:8-16.

9 For example, Berges, Die Verwerfung Sauls, 177-79; Daniel I. Block, The NIV Application Commentary: Deuteronomy (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012), 594; Kyle P. McCarter, I Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes and Commentary (Garden City: Doubleday, 1980), 265; Brian N. Peterson, The Authors of the Deuteron-omistic History: Locating a Tradition in Ancient Israel (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2014), 274. According to Dietrich, this understanding is "gewöhnlich" (Walter Dietrich, Samuel. Teilband 2: 1 Sam 13-26 [Neukirchen: Neukirchner Theologie, 2015], 154).

10 J. P. Fokkelman, Narrative Art and Poetry in the Books of Samuel. Volume II: The Crossing Fates (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1986), 87; Philip D. Stern, "I Samuel 15: Towards an Ancient View of the War-Herem," UF 21 (1989): 414-416.

11 Bernhard Lehnart, Prophet und König im Nordreich Israel: Studien zur sogenannten vorklassischen Prophetie im Nordreich Israel anhand der Samuel-, Elijah- und Elischa-Überlieferungen (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 80; Thomas C. Römer, The So-Called Deuteronomistic History: A Sociological, Historical and Literary Introduction (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 132, 145; Tanner, Amalek. Der Feind Israels, 73-75, 103. - Norbert Lohfink asserts that Deut 25:17-19 is "undoubtedly a proleptic legitimation of the narrative in 1 S. 15," phrased by the Deuteronomists in their first Deuteronomistic redaction of the Dtr. History (Norbert Lohfink, "חָרַם häram חרֶם hërem," Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament 5: 197). Based primarily on the literary connection to Deut 25:17-19, Giercke-Ungermann assumes that not only 15:2-3 but most of 1 Sam 15 comes from the Deuteronomistic milieu (Annett Giercke-Ungermann, Die Niederlage im Sieg: Eine synchrone und diachrone Untersuchung der Erzählung von 1 Sam 15 [Würzburg: Echter, 2010], 254-57).

12 In his recent article "Die Bearbeitung des deuteronomischen Gesetzes im Lichte biblischer Erzählungen" ZAW 131 (2019), 43-57, the author Stephen Germany discusses Deut 25:17-19 and Ex 17:8-14, but not the relationship to 1 Sam 15:2-3.

13 E.g. the influence of Proto-Isaiah and Jeremiah on Deutero-Isaiah, cf. Benjamin D. Sommer, A Prophet Reads Scripture: Allusion in Isaiah 40-66 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998); Richard L. Schultz, The Search for Quotation: Verbal Parallels in the Prophets (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999), 240-329; idem, "Isaianic Intertex-tuality and Intratextuality as Composition-Historical Indicators: Methodological Challenges in Determining Literary Influence," in Bind Up the Testimony: Explorations in the Genesis of the Book of Isaiah (eds. Daniel I. Block & Richard L. Schultz; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2015), 33-63. Cf. also Risto Nurmela, The Mouth of the Lord Has Spoken: Inner-Biblical Allusions in the Second and Third Isaiah (Landham: University Press of America, 2006).

14 The books of Zechariah and Malachi in particular have been the object of many studies on their literary precursors, e.g. Mark J. Boda & Michael H. Floyd (eds.), Bringing out the Treasure: Inner Biblical Allusion in Zechariah 9-14 (London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003); Risto Nurmela, Prophets in Dialogue: Inner-Biblical Allusions in Zechariah 1-8 and 9-14 (Ábo: Ábo Akademi University Press, 1996); Karl W. Weyde, Prophecy and Teaching: Prophetic Authority, Form Problems, and the Use of Traditions in the Book of Malachi (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2000). A thorough study on the relationship between the Book of Ezekiel and the Holiness Code was published some years ago by Michael A. Lyons, From Law to Prophecy: Ezekiel's Use of the Holiness Code (New York: T&T Clark, 2009). Cf. also Anja Klein, Schriftauslegung im Ezekielbuch: Redaktionsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zu Ez 34-39 (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2008). Recently, Nathan Mastnjak published a comprehensive study on the literary allusions in the Book of Jeremiah to Deuteronomy: Nathan Mastnjak, Deuteronomy and the Emergence of Textual Authority in Jeremiah (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016). Dalit Rom-Shiloni has also done several studies on this topic, e.g. "The Forest and the Trees: The Place of Pentateuchal Materials in Prophecy of the Late Seventh / Early Sixth Centuries BCE," in Congress Volume Stellenbosch 2016 (eds. Louis C. Jonker, Gideon R. Kotzé & Christl M. Maier; VTSup 177; Leiden: Brill, 2017), 56-92.

15 Cf. Alessandro Coniglio, "'Gracious and Merciful Is Yhwh...' (Psalm 145:8): The Quotation of Exodus 34:6 in Psalm 145 and Its Role in the Holistic Design of the Psalter," LASBF 67 (2017): 29-50; Jeffery M. Leonard, "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions: Psalm 78 as a Test Case," JBL 127/2 (2008): 241-65; Nahum M. Sarna, "Psalm 89: A Study in Inner Biblical Exegesis," in Biblical and Other Studies (ed. Alexander Altmann; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 29-46.

16 Cf. Cynthia Edenburg, Dismembering the Whole: Composition and Purpose of Judges 19-21 (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2016); Paul R. Noble, "Esau, Tamar, and Joseph: Criteria for Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions," VT 52/2 (2002): 219-52.

17 A recent PhD-dissertation has studied allusions in the Book of Judges to the Pentateuch: Jillian L. Ross, "A People Heeds Not Scripture: A Poetics of Pentateuchal Allusions in the Book of Judges." (PhD thesis, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, Deerfield), 2015.

18 Mastnj ak, Deuteronomy and the Emergence of Textual Authority, 28-29, is a notable exception.

19 See my study, "When a Prophet Quotes Moses: On the Relationship between the Book of Hosea and Deuteronomy," in Sepher Torath Mosheh: Studies in the Composition and Interpretation of Deuteronomy (eds. Daniel I. Block & Richard L. Schultz; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2017), 277-303.

20 Geoffrey D. Miller, "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research," CurBR 9/3 (2011): 286-94. He differentiates between three uses of this term in the scholarly literature: 1) "Intertextuality" in the Kristevan sense of the word as a synchronic reader-oriented study of all sorts of literary connections that a modern reader may conceive when reading texts. 2) "Intertextuality" as a term for the author-oriented, diachronic study of a given text's citations from and allusions to precursor texts. 3) Literary studies that seek to combine both the synchronic and the diachronic perspectives. Cf. also David M. Carr, "The Many Uses of Intertextuality in Biblical Studies: Actual and Potential," Congress Volume Helsinki 2010 (ed. Martti Nissinen; Leiden: Brill, 2012), 531. Already 25 years ago, Snyman underlined the contrast between intertextuality and studies in textual dependence as to purpose, methodology, and presuppositions (Gerrie Snyman, "Who is speaking? Intertextuality and textual influence," Neot 30/2 [1996]: 427-49). He clearly falls within Miller's category 1, but voices strong reservations against Miller's third group.

21 Miller is followed by Russel L. Meek in "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology," Bib 95/2 (2014): 280-91.

22 Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985); idem, "Types of Biblical Intertextuality," Congress Volume: Oslo 1998 (eds. André Lemaire and Magne Saebo; Leiden: Brill, 2000), 39-44; Sarna, "Ps 89: A Study in Inner Biblical Exegesis"; Karl W. Weyde, "Inner-Biblical Interpretation: Methodological Reflections on the Relationship between Texts in the Hebrew Bible," SEA 70 (2005): 287-300. Fishbane is followed by Meek, "Intertextuality," 284-89.

23 Schultz, Search for Quotation.

24 Leonard, "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions"; Mastnjak, Deuteronomy and the Emergence of Textual Authority, 13-18; Nurmela, Prophets in Dialogue, 34-36; Ross, "A People Heeds Not Scripture"; Sommer, A Prophet Reads Scripture.

25 Cf. Lyle Eslinger, "Inner-Biblical Exegesis and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Question of Category," VT 42 (1992): 48.

26 Schultz, Search for Quotation, 221; see also p. 227. Cf. also Lyons, From Law to Prophecy, 56-59.

27 Salman Rusdie has a notion about "story streams" constantly evolving into new stories, cf. Gerrie Snyman, "Intertextuality, story and the pretense of permanence of canon," OTE 8/2 (1995): 205-22. However, stock phrases in a language should be distinguished from "story streams."

28 Lyons, From Law to Prophecy, 70; Mastnjak, Deuteronomy and the Emergence of Textual Authority, 17.

29 Schultz, "Isaianic Intertextuality and Intratextuality," 56.

30 1 Kgs 8:16, 29; 11:32, 36; 14:21; 2 Kgs 21:7; 23:27; cf. 1 Kgs 8:44, 48.

31 Deut 12:5, 11, 14, 18, 26-27; 14:23-25; 15:20; 16:2, 6, 7, 11, 15-16; 17:8, 10; 18:6; 26:2; 31:11. The phrase varies as to what God will do with his name: to "put" it (לשום) on the location or to let it "dwell" (לשכן) there.

32 The three examples mentioned here are listed by Weinfeld as "Deuteronomic phraseology" (Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972], 324-25, 331, 350).

33 E.g. Kenneth A. Kitchen, "Ancient Orient, 'Deuteronism,' and the Old Testament," in New Perspectives on the Old Testament (Ed. J. Barton Payne; Waco: Word, 1970), 1-24; Alan Millard, "King Solomon in His Ancient Context," in The Age of Solomon: Scholarship at the Turn of the Millennium (Ed. Lowell K. Handy; Leiden: Brill, 1997), 50-51; idem, "Deuteronomy and Ancient Hebrew History Writing in Light of Ancient Chronicles and Treaties," in For Our Good Always: Studies on the Message and Influence of Deuteronomy in Honor of Daniel I. Block (eds. Jason S. DeRouchie, Jason Gile & Kenneth J. Turner; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2013), 13; David T. Tsumura, The First Book of Samuel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 29.

34 E.g. Dietrich, Samuel; Jan C. Gertz et al., T&T Clark Handbook of the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Literature, Religion and History of the Old Testament (London: T&T Clark, 2012), 310-11.

35 See Leonard, "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions," 246-53; Lyons, From Law to Prophecy, 68-69; Miller, "Intertextuality," 295; Schultz, Search for Quotation, 22324. Cf. also Cynthia Edenburg, "How (Not) to Murder a King: Variations on a Theme in 1 Sam 24; 26," SJOT 12/1 (1998): 72.

36 On this basis, many of Sommer's examples of suggested inner-biblical allusions in Deutero-Isaiah fall flat.

37 Lyons, From Law to Prophecy, 69-70; Schultz, Search for Quotation, 224-27.

38 Giercke-Ungermann, Niederlage im Sieg, 257; Leonard, "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions," 253-55; Sommer, A Prophet Reads Scripture, 5.

39 Schultz, "Isaianic Intertextuality and Intratextuality," 55.

40 Cf. Mark F. Rooker, "The Use of the Old Testament in the Book of Hosea," CTR 7 (1993): 51-66.

41 Cf. Jack R. Lundbom, Deuteronomy: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 33-35; Hans W. Wolff, Dodekapropheton 1: Hosea (4th ed.; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1990), xxvi; Konstantin Zobel, Prophetie und Deuteronomium: Die Rezeption prophetischer Theologie durch das Deuteronomium (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1992).

42 In his recent article, "How Have We Changed? Older and Newer Arguments about the Relationship between Ezekiel and the Holiness Code," in The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America (eds. Jan C. Gertz et al.; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016), 1055-74, Michael A. Lyons provides many further examples of this phenomenon in his study of the literary links between the Book of Ezekiel and the Holiness Code.

43 Schultz, Search for Quotation, 231.

44 Lyons, From Law to Prophecy, 59-67. See also his reflections in "How Have We Changed?" 1068-72. Leonard ("Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions," 257-64) too lists several criteria. In his deliberations, however, he puts too much weight on dating the texts beforehand in order to establish the line of quotation.

45 See the examples in David Carr, "Method in Determination of Direction of Dependence: An Empirical Test of Criteria Applied to Exodus 34,11-26 and Its Parallels," in Gottes Volk am Sinai: Untersuchungen zu Ex 32-34 und Dtn 9-10 (eds. Matthias Köckert & Erhard Blum; Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2001), 133-35, and Lyons, From Law to Prophecy, 95-97.

46 Leonard also refers to this criterion when he mentions the observation that one text in a verbal parallel sometimes presupposes information from the larger context of the other text (Leonard, "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions," 261-62). Likewise, Edenburg, "How (Not) to Murder a King," 73-74.

47 See the discussion in Vang, "When a Prophet Quotes Moses," 288-97.

48 Cf. Leonard, "Identifying Inner-Biblical Allusions," 258.

49 For a short overview, cf. David G. Firth, 1 & 2 Samuel (Nottingham: Apollos, 2009), 39-40. According to Pisano, a close study of 4QSam and LXX shows that both versions often have inserted expansions in the text. This does not preclude that from time to time one of the LXX recensions or 4QSam may have preserved a better text than the one reflected in MT (Stephen Pisano, Additions or Omissions in the Books of Samuel: The Significant Pluses and Minuses in the Massoretic, LXX and Qumran Texts [Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1984], 283-85).

50 The LXX has άπήντησεν αύτώ έν τη όδώ "met him (in a hostile manner) on the road" for the Hebrew שָם לוֹ בַדֶרֶךְ "opposed him on the way." This phrasing is probably a free rendering of the Hebrew idiom rather than a reflection of the Hebrew phrase in Deut 25:18 קָרְךָ בַדֶרֶךְ "surprised you on the way," since the Greek verb απαντάω only once renders the Hebrew קרה (1 Sam 28:10). However, 4QSam is not preserved for 15:2-3.

51 As opposed to 1 Sam 15:17, 26, 30, 35; 16:1; or chapters 13-14.

52 Cf. Deut 7:18; 8:2; 24:9; and Irene Schulmeister, Israels Befreiung aus Ägypten: Eine Formeluntersuchung zur Theologie des Deuteronomiums (Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2010), 151-54.

53 Schulmeister here identifies פקד as "Wahrnehmungsverb" ("perception verb") in line with ראה and שמע in Deut. and its parallels (Schulmeister, Israels Befreiung, 152). However, it appears more natural to see פקד together with her category of "Weitergabeverb" ("transmission verb") like ידע and זכר in Deut.

54 Cf. Tsumura, First Samuel, 389.

55 Some scholars have suggested that שים ל should be understood as a technical military term in the manner of 1 Kgs 20:12 (e.g., Hans J. Stoebe, Das erste Buch Samuelis [Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1973], 284).

56 Thus, rightly Moshe Garsiel, The First Book of Samuel: A Literary Study of Comparative Structures, Analogies and Parallels (Ramat Gan: Revivim Publishing House, 1985), 51.

57 It may be the case that the gentilic name אֲגָגִּי in Est 3:1 intends to refer the reader to the Amalekite king Agag in 1 Sam 15, so, e.g., Jon D. Levenson, Esther (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1997), 66. However, the gentilicum may also refer to an unknown Persian or Median clan. The often-supposed allusion in the Book of Esther to the Saulide-Amalekite conflict is therefore rather questionable.

58 Cf. also Mastnjak, Deuteronomy and the Emergence of Textual Authority, 28-29.

59 Many scholars refer to Weinfeld's overview in Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School, 320-65.

60 In my article, "Israel in the Iron-Smelting Furnace? Towards a New Understanding of the כוּר הַבַרְזֶל in Deut 4:20," HIPHIL Novum 1/1 (2014): 27-28 [cited 7 July 2020; online https://hiphil.org/index.php/hiphil/article/view/59/34], I have argued from literary and contextual considerations that the metaphorical locution כוּר הַבַרְזֶ ל in Deut 4:20 appears to have the literary priority compared with the parallel phrase in 1 Kgs 8:51 and Jer 11:4.

61 For example, the frequent locution "burn offerings on the high places" ( קִּ טּר / מַקְטִּירבַבָמוֹת) is found only in Kings, but neither in Deuteronomy, in other writings in the "Deuteronomistic History," nor in the Book of Jeremiah.

62 In Jer 7:12, also, past tense is used (שכנתי). Cf. Neh 1:9; Ps 78:68.

63 1 Kgs 8:16, 29; 11:32, 36; 2 Kgs 21:7; 23:27.

64 1 Kgs 8:16; 11:32, 36; 14:21; 2 Kgs 21:7; 23:27. In 1 Kgs 8:29 both expressions are combined.

65 Cf. note 33 above.