Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.33 no.2 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2020/v33n2a7

ARTICLES

Job's Dark View of Creation: On the Ironic Allusions to Genesis l:l-2:4a in Job 3 and their Echo in Job 38-39

Tobias Häner

University of Vienna, Austria

ABSTRACT

Research on the intertextual relations between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a (undertaken by Michael Fishbane, Leo Perdue, Samuel Balentine and others) has demonstrated the likely presence of conspicuous parallels between the two texts. However, the rhetorical function of these connections remains an unsolved problem. This article's reassessment of the lexical, motivic and structural parallels as well as the comparison of Job 3 with Jer 20:14-18 attempts to show that not only does Job's soliloquy refer to the priestly creation hymn by means of allusive irony to facilitate a critical engagement with the Torah. Also, the same rhetorical device is used in Yhwh's first speech (Job 38-39) which in turn alludes to Job 3 and is understood as ironically reversing Job's allusive curse and lament. Based on these findings we may conclude that Job is ultimately defeated by Yhwh with his own arguments, yet not in a harsh, but rather in a soft and mitigative way.

Keywords: Book of Job; irony; parody; inner-biblical allusions; creation theology

A INTRODUCTION

The view that in the book of Job there is not only a dialogue going on between God and Satan, Job and his friends, and God and Job, but that beyond that the book itself is in discourse with various parts of Israel's literary traditions and in particular with the Torah, is not new to biblical research.1 The aim of the following investigation is to focus on the rhetorical devices used in this discourse, specifically regarding the allusions to Gen l:l-2:4a in Job 3. I will argue that this rhetoric is best described as allusive irony. In addition, my aim is show that, in a very similar way to how Job 3 ironically inverts the priestly creation hymn, Yhwh's first speech in Job 38-39 refers to Job 3 by means of allusive irony, the result of which is that Job is defeated by his own arguments.

To this end, I will firstly give a brief summary of the current state of research regarding the parallels between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a. Secondly, I will undertake a reassessment of these parallels by analysing lexical, motivic, and structural correspondences. Thirdly, I will evaluate the rhetoric of Job 3 by highlighting the exaggerated mode of Job's curse and lament and, consequently, arguing for the ironic function of the allusions to the creation account. Finally, I will show that, in a similar way, also Job 38-39 alludes to Job 3 through the use of irony. The present study, therefore, wants to contribute to a better understanding of Job's initial soliloquy and of the function of irony in the book as a whole.

B CURRENT STATE OF RESEARCH ON THE PARALLELS BETWEEN JOB 3 AND GEN 1:1-2:4A

In the following, I will firstly give a brief overview of the research on the connections between Job's opening soliloquy and the priestly creation hymn, from Michael Fishbane's seminal article of article on Job 3:3-13, published in 1971, to the more recent studies of Andrea Beyer and Samuel Balentine. Secondly, I will summarize the critique against Fishbane and those who adopted and further corroborated his claims.

1 Majority Report

In his article "Jeremiah IV 23-26 and Job III 3-13: A Recovered Use of the Creation Pattern", Fishbane argues that the pattern of seven days of creation in Gen 1:1-2:4a is reflected in Job 3.2 In particular, he argues that Job 3,4a (יהיחשך) echoes the creative act of the first day (Gen 1:3-4), whereas in Job 3:4b (ממעל), a parallel to the second day may be perceived (מעל); similarly, the fourth, fifth, and sixth day (Gen 1:14-19, 20-23, 24-31) are reflected in Job 3:6, 8 and 11, whereas the seventh day (Gen 2:2-4a; cf. Exod 20:11) finally is mirrored in 3:13. Additionally, Fishbane compares Job 3:3-13 with both Akkadian and Egyptian literature in order to claim a mantic background for the Joban passage, and consequently calls it a "counter-cosmic incantation"3. On closer inspection, however, the parallels he points out don't appear to be very significant; beside a few isolated lexical correspondences, some of his claims about motivic resemblances are based on rather poor textual evidence. Nonetheless, as we will see, Fishbane's brief analysis has proved to be highly influential for later studies on this issue.

In fact, 15 years later, Fishbane's interpretation is taken up by Leo Perdue4, who additionally points out structural analogies, as he notes that the seven days in the creation hymn are paralleled by Job's seven curses in Job 3:39; also, the fact that the 15 jussives and imperatives in Gen 1:1-2:4a are outnumbered by the 16 jussives and prohibitions in Job 3. This leads him to the conclusion that Job is "attempting to overpower the creative structure of divine language"5. Finally, Perdue highlights motivic contrasts (light: Gen 1:3 -darkness: Job 3:4-9; rest as renewal of life: Gen 2:1-3 - rest at the end of life: Job 3:13-19). On the whole, according to Perdue, Job 3 describes the reversal of four metaphors of creation, namely word, procreation, artistry, and battle. Similar to Fishbane, Perdue interprets Job 3 as a negation of the divine creative works as described in Gen 1:1-2:4a; more precisely, he discerns in Job 3 a "disorienting reversal of creation language"6 and an "attack on P's formulation of creation"7.

In 2002, Valerie Pettys8 adopts both Fishbane's and Perdue's textual analyses, without providing a detailed study of the correspondences between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a; nonetheless, she mentions an additional structural analogy, as she notes that in Job 3:3-9, the negation is used six times, followed by fro in 3:10-11, what might refer to the six days of creation that are concluded with the day of rest. Beyond that, in Pettys' reading, the allusion of Job 3 to Gen 1:1-2:4a is marked by irony: "Job's use of past testimony in order to make sense of its shattering by the present is a study in irony", and adds that "[i]n the process, he affirms the vehicle of his dissent, even as he insists on its change."9

Also, Yohan Pyeon's10 interpretation of Job 3, published only a year after Petty's study, is based primarily on the parallels to Gen l:l-2:4a as highlighted by Fishbane, and basically adopting Perdue's reading. He points out the cultic frame of reference in Gen 1:1-2:4a given its connections to Ex 25-31 and 35-40. Furthermore, he sees in Job 3 a reflection of the chapter's historical context, when creation as envisioned by P was sensed as inadequate to explain the situation of the post-exilic community.

More recently, the correspondences between the two texts have been re-evaluated by Andrea Beyer11. She highlights eight points of contrast, as e.g. the absorption of the daylight by darkness (Job 3:4-6) instead of their separation (Gen 1:4), the "barren" (גלמוד) night (Job 3:7) in opposition to the multiplication and blessing (Gen 1:11, 22, 28), and the revocation of the count of days (Job 3:6) in contrast to the quantification of the spaces of time (Gen 1:14-16). Based on this evidence, Beyer concludes that Job 3:3-9 formulates an "Angriff auf die Schöpfung"12 ("attack on creation") and responds with a "Rücknahme der Schöpfung"13 ("retraction of creation").

Finally, the parallels outlined by Fishbane are adopted also by Samuel E. Balentine in his commentary on the Book of Job.14 In addition, in a book chapter published in 2013, Balentine includes the Joban prologue in an extended structural comparison, arguing that the six days of creation in Gen 1 correspond to the six scenes in the prologue, whereas the seventh day (Gen 2:1-3) may either be reflected in the epilogue, where the verb ברך that is used three times in Gen 1:1-2:4a (1:22, 28; 2:3) and six times in the Joban prologue (1:5, 10, 11, 21; 2:5, 9), turns up a seventh time (42:12), or be contrasted by Job's curse (Job 3:1 ויקלל) at the place of Yhwh's final blessing of the creation (Gen 2:3 ויברך).15

In sum, the biblical scholars listed here, from Fishbane to Balentine, mostly agree regarding their interpretation of Job 3. First, they identify conspicuous parallels to Gen 1:1-2:4a; second, they identify these parallels as allusions in Job's soliloquy to the creation account (without, however, necessarily using the term "allusion"), and third, in consequence, they all read Job's soliloquy as a reversal of creation as outlined in the priestly account.

2 Minority Report

Not all interpreters of the book of Job, however, agree with this reading of Job 3. Among those who question the significance of the alleged connections between Gen 1:1-2:3 and Job 3, David Clines denies that Job 3 might be interpreted as a reversal of creation, since the textual connections to Gen 1 are weak and "Job's concern is not with the created order as a whole but with those elements of it that have brought about his own personal existence."16 Similarly, Melanie Köhlmoos notes that there are only a few structural correspondences between Gen 1 and Job 3 (and 38).17 Konrad Schmid18 argues that textual correspondences - except between Gen 1:3 (יהי אור) and Job 3:4 (הי חשך') - are weak, and that Job only wishes that the day of his birth might be deleted, but doesn't express the desire to reverse the order of creation as a whole.19Ultimately, according to Schmid, the theology of P is not rejected in the book of Job, but dialectically reassessed. Finally, JiSeong Kwon notes that "Job's text does not match a clear-cut pattern of the six-day creation"20

In conclusion, we can state that, on the one hand, research on the relation between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a has revealed what is alleged to be conspicuous similarities between the two texts in regards to lexis, motifs, and structure, which in turn are thought to place Job's curse and lament in contrast to the priestly praise of creation. However, on the other hand, some critics of this view have legitimately pointed out the lack of precision and differentiation regarding the alleged parallels. Therefore, a careful reassessment of the relation between the two texts is in order.

C REASSESSMENT OF THE CONNECTIONS BETWEEN GEN 1:1-2:4A AND JOB 3

Our reassessment of the connections between Gen 1:1-2:4a and Job 3 develops in three steps: firstly) the lexical correspondences between the first canto of Job's soliloquy and Gen 1 will be listed, after which we will look at shared motifs and themes, and finally structural analogies will be evaluated.

1 Lexical Correspondences

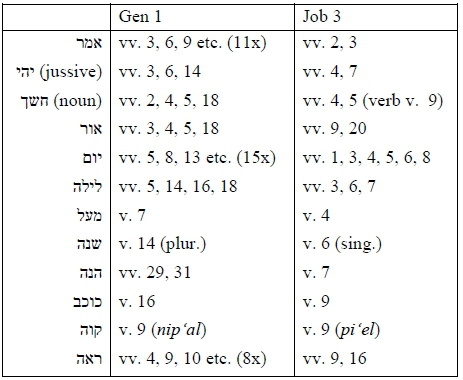

Regarding lexical agreements, we can count twelve different lexical elements that appear in both texts:

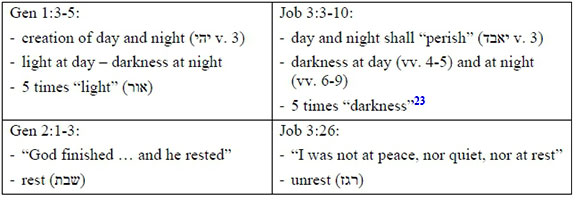

However, these lexemes are mostly very common in the HB, so that the shared use doesn't appear conspicuous. Moreover, none of these are used in corresponding syntagmas. The opposition between the first creative act - יהי אור - and Job's contrastive curse of his day of birth - יהי חש - therefore stands out as the most noticeable lexical connection between the two texts. However, a close look shows that on the one hand, the vocabulary that is taken up in Job 3 to a large extent is used in the section on the first day (Gen 1:3-5):

Gen 1:3-5 (lexical correspondences with Job 3 are underlined):

3ויאמר אלהים יהי אור ויהי אור

וירא אלהים את האור כי טוב ויבדל אלהים בין האור ובין החשך4

5ויקרא אלהים לאור יום ולחשך קרא לילה ויהי ערב ויהי בקר יום אח ד

On the other hand, the shared vocabulary of Gen 1:3-5 is repeated various times in Job's opening speech:

יהי Job 3:4, 7 חשך (noun) vv. 4, 5 (verb v. 9) אור vv. 9, 16, 20 יום vv. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 לילה vv. 3, 6, 7

This dense resp. repeated use of a shared vocabulary in the first sections of both texts renders these correspondences conspicuous. Therefore, we can state that Job's curse of the day of his birth and the night of his conception in Job 3:39 subtly alludes to the first act of creation as described in Gen 1:3-5.

2 Shared motifs and themes

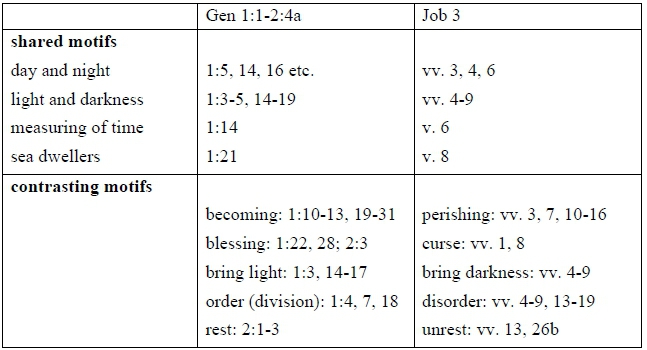

Concerning shared motifs and themes, the relation between the two texts can be described as a mixture of correspondences and contrasts:

As the list shows, motivic correspondences and contrasts between the two texts are intertwined. Yet, at the same time, each text also takes up themes and motifs that don't appear in the other one, namely animals and humans in Gen 1:21-28 resp. birth and death in Job 3:11-19. Roughly speaking, both correspondences and contrasts are more intense in the first canto of Job's soliloquy (Job 3:3-10); in the second and third canto (vv. 11-19 and 20-26) instead,21 new motifs and themes (namely birth and death) are brought in, while the agreements with Gen 1:1-2:4a tend to fade. In the last verse of Job 3, however, we grasp again a motivic connection, since the emphasis on unrest in v. 26 contrasts to the rest of Yhwh on the seventh day (Gen 2:1-3). As we will see, this observation is important regarding the structural analogies between the two texts.

3 Structural analogies

So far, our analysis has yielded a conspicuous density of both lexical correspondences and motivic agreements and contrasts between in Job 3:3-10 and Gen 1:35. On the whole, therefore, we can state that the first canto of Job's soliloquy reminds of the beginning of the creation hymn. Now, as seen before, in the final verse of Job 3 we can observe a connection with the seventh day in Gen 2:1-3. Admittedly, this connection at the end of Job's soliloquy is less evident, as there is no shared vocabulary between Job 3:26 and Gen 2:1-3;22 nonetheless, we may point out that the correspondences between the beginnings of both texts generate an expectation that favours the recognition of the motivic contrast between their final parts. Structurally, therefore, we may summarize the connections between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a in the following way:

As this summary shows, the connections both at the beginning and the end of the two texts are marked by contrast: Instead of Yhwh's first word "let there be" (יהי v. 3), Job's first word in the soliloquy is "let perish" (יאבד v. 3), and instead of the distinction of the day's light and night's darkness, Job wants both day and night to be darkness, as is evident also by the fact that the noun אור is repeated five times in Gen 1:3-5, whereas in Job 3:3-10, Job speaks five times of "darkness" (yet by using three different terms). Similarly, Job 3:26 stands in contrast to Gen 2:1-3, since at the place of (divine) rest, Job laments his unrest.

4 Summary

In sum, we can conclude that the agglomeration of correspondences to Gen 1:35 in the first canto of Job's soliloquy generates an intertextual connection that can be termed as subtle allusion and that is marked by contrast. The last verse of Job 3 takes up this allusion by contrasting God's rest at the seventh day with Job's desperation over his unrest.

D IRONIC FUNCTION OF THE CONTRASTIVE ALLUSION IN JOB 3 TO GEN 1:1-2:4A

In the following, I want to evaluate the rhetoric function of the contrastive allusion of Job 3 to Gen 1:1-2:4a. For this purpose, I will briefly go into the correspondences between Job 3 and Jer 20:14-18; as we will see, the comparison to this prophetic text shows that Job's soliloquy can be termed a parody of the lament form and therefore has an ironic function; consequently, I will bring together this ironic function with the allusions reassessed above by offering a brief reflection on the term allusive irony.

1 Correspondences between Job 3 and Jer 20:14-18

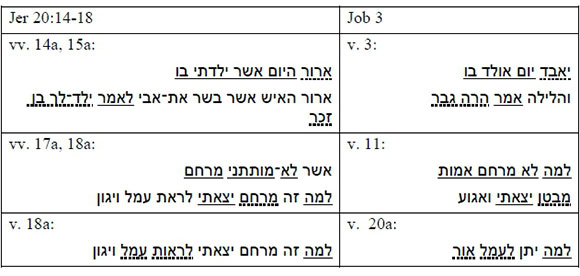

Similarly, to the correspondences between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a, the parallels to Jer 20:14-1824 are limited to a rather small number of lexemes, most of which are frequent in the HB:

But here again, the significance of the correspondences comes to the fore by the similarity of the beginnings of both texts, since Job, analogous to Jeremiah, curses the day of his birth.25 In order to understand the modality of the parallels, we have to take into consideration the structure of Job 3, as the correspondences to Jer 20:14-18 are most salient in the opening verses of each canto (Job 3:3, 11 and 20):26

Based on this observation, we can further state that the first canto of Job's soliloquy (Job 3:3-10) expands the first verse of Jeremiah's lament (Jer 20:14), i.e. the cursing of the day of birth, by adding the night of conception (Job 3:3b) and making them both subsequently object of distinct curses (day: vv. 4-5; night: vv. 6-9). The second and the third canto instead lengthen the last two verses (Jer 20:17-18), i.e. the desire to have died in the mother's womb (resp. immediately after birth in Job 3:11b, cf. Jer 20:18), by contrasting the quietness of the dead and the rest in the Sheol to the unrest in the present life. In other words, what is expressed in five verses in Jer 20:14-18, is extended to 24 verses in Job 3.

The comparison between Job 3 and Jer 20:14-18, therefore, foregrounds the exaggerated and overreaching mode of Job's curse and lament. As G. Fuchs observes, whereas Jeremiah's curse is limited to the day of his birth, Job wishes that the whole creation would be undone;27 according to E. Greenstein, to Joban poet attenuates Jer 20 "ad absurdum"28, since Job seeks to eliminate something that has already been; similarly, D. Clines terms Job's lament and curse as "denatured"29. In fact, Job does not simply curse the day of his birth, but wants it to be eliminated - and not only that day, but also the night of his conception; in addition, he not only deplores to be born and alive, but praises death and the underworld. This excessive and exaggerated heightening of the lament reveals the pragmatic insincerity of Job's soliloquy. With Seow, therefore, we can conclude that "(...) the poem is not a strict lament form but a parody of it."30

2 Allusive irony

The parody of the lament form provides the framework in which the contrastive allusions to Gen 1:1-2:4a are embedded. Against this background, the ironic tone of these allusions comes to the fore. In order to further evaluate the function of this allusive irony, let me go into a brief reflection on the term of irony.

As Heinrich Lausberg31 points out, in classical rhetoric, two types of irony can be distinguished: the trope (tropus) and the figure of thought (figura). Irony as a trope can be described as expression of a thing by the contrary and is more or less equivalent to what in today's linguistics and literary theory is called verbal irony.32 Irony as a figure of thought instead occurs in two modes: the dissimulatio, i.e. the dissembling of the own point of view - known also as "Socratic irony"33 -, and the simulatio, i.e. the simulating of the correspondence of the own point of view with that of the opponent resp. the expression of the own point of view by using the opponent's rhetorical means.34 The classical philologist René Nünlist35 highlights an example of the latter in the Iliad:

[Pandaros to Diomedes:] "Thou art smitten clean through the belly, and not for long, methinks, shalt thou endure; but to me hast thou granted great glory."

Then with no touch of fear spake to him mighty Diomedes: "Thou hast missed and not hit; but ye twain [sc. Pandaros and Aineias], methinks, shall not cease till one or the other of you shall have fallen and glutted with his blood Ares, the warrior with tough shield of hide."36

Pandaros' "methinks" (6¾)) is a case of irony as a trope: He is sure to have fatally hit his adversary, but - contrary to his conviction - utters an ironic expression of doubt, glorying in his victory. The echoic repetition of the same locution by Diomedes, instead, is a clear example of the simulatio: By imitating Pandaros, Diomedes mocks his enemy's certainty of victory.

Turning back from this example to the theory on irony, we might refer to the mention theory of the linguists Dan Sperber and Deirdre Wilson. According to their thesis, all verbal ironies "are implicit echoic mentions of meaning conveying a derogatory attitude to the meaning mentioned"37. With the German linguist Edgar Lapp, however, we can rather define verbal irony as "Simulation der Unaufrichtigkeit"38 ("simulation of insincerity"), whereas the echoic mention represents one specific type of verbal irony.39 Marika Müller, another German linguist, helpfully terms this type "Anspielungsironie"40, what we translate here as "allusive irony". For sure, this type of irony overlaps with the parody, as the latter, in a similar way as the allusive irony, stylistically imitates a text or genre or (type of) person.41 However, whereas the parody aims at a comic effect by means of exaggeration, allusive irony is characterized by the transposition of the context, provoking the questioning of the text or concept to which the ironic locution is alluding.

Turning back to Job 3, my contention is that the relation of the Joban soliloquy to Gen 1:1-2:4a is best described as allusive irony. As we have seen, the exaggerated mode of Job's lament signals pragmatic insincerity. Now, with regard to the allusions to the creation account, this insincerity functions as a first transposition of context, providing a framework that allows a covert criticism. A second transposition occurs by the contrastive replacement of firstly darkness for light, secondly of perishing for becoming, and thirdly - more subtly at the end of the speech - of unrest for rest. By means of this twofold transposition, the context in which the allusions to Gen 1:1-2:4a appear is shaped in a way that reveals the critical function of these allusions. In this way, Job 3 subtly undermines the optimistic creation theology of Gen 1:1-2:4a.

Based on these observations, we may draw some further conclusions Firstly, we may assume that the indirectness und covertness of the criticism are owed to the authoritative status of the Torah that is impeding a direct critique. Secondly, we may argue that the ironic criticism effects a partial suspension of the authority of the text to which is alluded: The reference presupposes and to a certain extent affirms the validity of the textual authority and undermines it at the same time. Thirdly, in more general terms, we can state that the allusive irony of Job 3 invites the readers to a critical engagement with the Torah.

E YHWH'S ALLUSIVE IRONY IN JOB 38-39

In the final part of my paper, I want to briefly explore the way in which Yhwh's first speech (Job 38-39) alludes to Job's opening speech. Keel's thesis, brought forward in his seminal study on Yhwh's speeches published in 1978, that in Job 38-39 Yhwh replies to Job 3 by rebutting Job's dark view of creation,42 has gained wide recognition among scholars.43 In fact, lexical correspondences (e.g. חשך, רנן , כוכבים , סכך , דלתי) between the two texts are numerous,44 and various important motifs of Job 3, such as light and darkness (3:4-9; 38:2, 12, 19, 24), birth (3:11-12; 38:8-9, 21, 28-29; 39:1-4), death (3:13-19; 38:17; 39:30), and turmoil/unrest (3:24-26; 39:16, 22, 24), are taken up in Job 38-39. However, in my view, rather little attention has been paid up to now to the ironic function of the reference to Job's soliloquy in the divine speech.

A few examples may illustrate the allusive irony that is operative in Yhwh's discourse. The first allusion to Job 3 occurs in the rhetorical question that opens up God's speech to Job:

Job 38:2: במלין בלי־דעת מי זה מחשיך עצה

"Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?"

The verb חשך (hip'il) reminds of Job's first canto (Job 3:3-10), since there, as we have seen above, "darkness" functions as the most prominent motif (cf. vv. 4-6, 9).45 Although the correspondence consists of only one word, for two reasons we can claim an allusion here: On the one hand, the reference to Job 3 is corroborated in the following sections of Job 38-39, since the dichotomy of light and darkness that pervades Job 3:3-10 is taken up in 38:12, 19, 24. On the other hand, the blame of "darkening counsel" corresponds to Job 3 in consideration of the allusions to Gen 1:1-2:4a that we identified there. Furthermore, the use of חשך in the hip'il stem with Job as implied subject is conspicuous, for unlike in most other cases, the verb is not used metaphorically here, and Yhwh does not figure as the subject, as is usually the case.46

By means of this subtle allusion, the criticism of Job that is explicit in the locution of Job 38:2b ("by words without knowledge"), comes to the fore already in the first colon. In other words, Yhwh is defeating Job with his own arguments, as he is using the same rhetorical device, namely allusive irony. The harsh critique of Job who is accused of having spoken "without knowledge", is somewhat mitigated in this way. Consequently, Yhwh's answer, that might appear fierce and humiliating at a first glance, reveals itself as benevolent and even humorous.

Some further examples of ironic allusions to Job 3 in the first divine speech confirm our interpretation:

1 In 38:7, we may assume a subtle allusion to 3:7-9:

Job 38:7 ויריעו כל־בני אלהים ברן־יחד כובבי בק ר

"... when the morning stars rejoiced together, and all sons of God shouted for joy?"

The "morning stars" (כובבי בקר) remind of the "twilight stars" (כוכבי נשפו) in 3:9, whereas their "rejoicing" (רנן) contrasts Job's denial of a "joyful cry" (רננה) in 3:7 and the "cursing" (קבב) by the "cursers of the day" (אררי־יו)47in 3:8.

2 Similarly, by reminding of Job's birth, 38:21 subtly alludes to the motif of birth in 3:3 and 10-12:

Job 38:21: ומספר ימיך רבי םידעת כי־אז תולד

"You know, for you were born then, and the number of your days is great!"

Beside the antiphrastic verbal irony (i.e. irony as a trope) in the opening "you know" - for Job obviously does not know "the way to the dwelling of light" nor "the place of darkness" (38:19) he was asked about before - and in 38:21b, there is also a subtly allusive irony in YHWH's reference to Job's birth, since it reverses the latter's wish to have the day of his birth eliminated (Job 3:3). This allusion to Job 3 is underlined by the recurrence of the motif of birth in 38:8-9, 28-29 and 39:1-4.48

3 In 39:2, Job is invited to "number the months" of the gestation time of the deer:

Job 39:2: וידעת עת לדתנה תספר ירחים תמלאנה

"Do you number the months that they fulfil, and do you know the time when they give birth?"

Here again, beside the verbal irony that lies in the fact that Job is asked to do what he is not able to accomplish, 39:2a ironically inverts Job's wish that the night of his conception may not be included in the "number of months" (3:6):49

Job 3:6: אל־יחד בימי שנה במספר ירחים אל־ הלילה ההוא יקחהו אפל

"That night, let thick darkness seize it,

let it not rejoice among the days of the year,

let it not come into the number of months." (cf. 39:2a)

4 Finally, the strophes on the wild donkey (39:5-8, 9-12) point out the freedom from labour of these two species, whereas Job in 3:18-19 imagined this freedom for those in the Sheol. In particular, 39:7b echoes 3:18b:50

Job 39:7: ישחק להמון קריה תשאות נוגש לא ישמע

"It [= the wild ass] scorns the tumult of the city,

it does not hear the shouts of the driver.

Job 3:18: לא שמעו קול נגש יחד אסירים שאננו

There [= in the Sheol] the prisoners are at ease together, they do not hear the voice of the driver.

Further motifs that are taken up from Job 3 might be mentioned, as e.g. 38:17 (and 39:30) echoes Job's longing for death (3:11-23), and in 39:16, 22, 24, the motif of fear (פחד) and unrest (רגז) turns up again (cf. 3:25-26).

The brief examples demonstrate the similarity between the allusions in Yhwh's first speech to Job's soliloquy and those of Job 3 to Gen 1:1-2:4a. The same way as Job reversed crucial motifs of the creation hymn, now Yhwh on his part subverts Job's initial curse and lament by taking up central motifs of Job's speech in a reversed mode. In both Job's and Yhwh's speeches we can term these contrastive allusions as ironic, since they are aimed at an indirect, partly covert critique. The main effect of Yhwh's allusive irony is mitigation: Instead of attacking and rebutting Job directly, the divine speech partly conceals the critique and by this softens its harshness and rigour.

F CONCLUSION

In the last decades, considerable research has been undertaken concerning the intertextual relations between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a, though not always with sufficient precision and methodical accuracy. In particular, scant attention has been given to the rhetoric function of these connections. As our analysis has shown, the lexical and motivic correspondences between the two texts are conspicuous, especially at the beginning of both passages, and can therefore be termed as allusions. Furthermore, they are structurally congruent, as they are particularly apparent between the openings and endings of both texts; finally, they are marked by contrast, as e.g. the creation of light is replaced by Job's longing for darkness.

The function of these contrastive allusions is narrowly linked to the insincere mode of the curse and lament, which in turn has come to the fore by a comparison between Job 3 and Jer 20:14-18, revealing Job's soliloquy as a parody of the lament form. On the base of this pragmatic insincerity, the parallels between Job 3 and Gen 1:1-2:4a come into view as a specific kind of (verbal) irony, namely allusive irony ("Anspielungsironie"), which at the same time partly questions and affirms the authority of the reference text.

Finally, the same rhetorical device is operative also in Yhwh's first speech (Job 38-39), that now in turn alludes to Job 3. By ironically subverting Job's allusive curse and lament, the latter is defeated with his own arguments. The most important effect of this covert and indirect mode of critique to our view is the softening and mitigation of the otherwise harsh - or even rude - rebuke of Job.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albright, William F. "Rezension Gustav Hölscher: Das Buch Hiob (1937)." Journal of Biblical Literature 57 (1938): 227-228. [ Links ]

Balentine, Samuel E. "Job and the Priests: 'He Leads Priests Away Stripped' (Job 12:19)." Pages 42-53 in Reading Job Intertextually. Edited by Katharine J. Dell and Will Kynes. LHB 574. New York: T & T Clark, 2012. [ Links ]

Balentine, Samuel E. Job. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary 10. Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2006. [ Links ]

Barbiero, Gianni. "The Structure of Job 3." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 127 (2015): 43-62. [ Links ]

Beyer, Andrea. "Hiobs Widerworte. Die Querbezüge zwischen Ijob 3,3-9 und Gen 1,1-2,4a." BZ 55 (2011): 95-102. https://doi.org/10.1163/25890468-055-01-90000007. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. Job 1-20. WBC 17. Waco: Word Books, 1989. [ Links ]

Dell, Katharine J., and Will Kynes, eds. Reading Job Intertextually. LHB 574. New York: T & T Clark, 2012. [ Links ]

Engljähringer, Klaudia. Theologie im Streitgespräch: Studien zur Dynamik der Dialoge des Buches Ijob. SBS 198. Stuttgart, 2003. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. "Jeremiah IV 23-26 and Job III 3-13: A Recovered Use of the Creation Pattern." Vetus Testamentum 21 (1971): 151-167. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853371x00029. [ Links ]

Fuchs, Gisela. "Die Klage des Propheten: Beobachtungen zu den Konfessionen Jeremias im Vergleich mit den Klagen Hiobs. Erster Teil." Biblische Zeitschrift 41 (1997): 212-228. [ Links ]

Greenstein, Edward L. "Jeremiah as an Inspiration to the Poet of Job." Pages 98-110 in Inspired Speech: Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. Essays in Honour of Herbert B. Huffmon. Edited by John Kaltner and Louis Stulman. JSOT.S 378. London: T & T Clark, 2004. [ Links ]

Habel, Norman C. The Book of Job: A Commentary. OTL. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Hermisson, Hans-Jürgen. "Notizen zu Hiob." Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 86 (1989): 125-139. [ Links ]

Homer. Iliad: Translated by Augustus T. Murray and William F. Wyatt. Loeb Classical Library 170. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924. https://doi.org/10.4159/dlcl.homer-iliad.1924. [ Links ]

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Janzen, John G. "The Place of the Book of Job in the History of Israel's Religion." Pages 523-537 in Ancient Israelite Religion: Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross. Edited by Patrick D. Miller and Frank M. Cross. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Janzen, John G. Job. Interpretation. A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Keel, Othmar. Jahwes Entgegnung an Ijob: Eine Deutung von Ijob 38-41 vor dem Hintergrund der zeitgenössischen Bildkunst. FRLANT 121. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978. https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666532825. [ Links ]

Knox, Dilwyn. Ironia: Medieval and Renaissance Ideas on Irony. Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition 16. New York: Brill, 1989. [ Links ]

Köhlmoos, Melanie. Das Auge Gottes: Textstrategie im Hiobbuch. FAT 25. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1999. [ Links ]

Kwon, JiSeong J. "Divergence of the Book of Job from Deuteronomic/Priestly Torah: Intertextual Reading between Job and Torah." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 32 (2018): 49-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/09018328.2017.1376522. [ Links ]

Kwon, JiSeong J. Scribal Culture and Intertextuality: Literary and Historical Relationships between Job and Deutero-Isaiah. FAT II 85. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. [ Links ]

Muecke, Douglas, C. Irony and the Ironic. The Critical Idiom 13. London: Methuen, 1982. [ Links ]

Lapp, Edgar. Linguistik der Ironie. 2nd Edition. TBL 369. Tübingen: Narr, 1997. [ Links ]

Lausberg, Heinrich. Handbuch der literarischen Rhetorik: Eine Grundlegung der Literaturwissenschaft. 4th Edition. Philologie. Stuttgart: Steiner, 2008. [ Links ]

Müller, Marika. Die Ironie: Kulturgeschichte und Textgestalt. Epistemata. Reihe Literaturwissenschaft 142. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1995. [ Links ]

Müller, Wolfgang G. "Ironie, Lüge, Simulation, Dissimulation und verwandte rhetorische Termini." Pages 189-208 in Zur Terminologie der Literaturwissenschaft: Akten des IX. Germanistischen Symposions der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft, Würzburg 1986. Edited by Christian Wagenknecht. Germanistische Symposien, Berichtsbände 9. Stuttgart: Metzler, 1989. [ Links ]

Nünlist, René. "Rhetorische Ironie - Dramatische Ironie. Definitions- und Interpretationsprobleme." Pages 67-87 in Zwischen Tradition und Innovation: Poetische Verfahren im Spannungsfeld Klassischer und Neuerer Literatur und Literaturwissenschaft. Edited by Jürgen P. Schwindt. München: Saur, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110958294-005. [ Links ]

Perdue, Leo G. "Job's Assault on Creation." Hebrew Annual Review 10 (1986): 295315. [ Links ]

Perdue, Leo G. "Metaphorical Theology in the Book of Job: Theological Anthropology in the First Cycle of Job's Speeches (Job 3; 6-7; 9-10)." Pages 129-156 in The Book of Job. Edited by Willem A. M. Beuken. BETL 114. Leuven: University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Perdue, Leo G. Wisdom in Revolt: Metaphorical Theology in the Book of Job. BiLiSe 29. Sheffield: Almond Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Pettys, Valerie F. "Let there be Darkness: Continuity and Discontinuity in the 'Curse' of Job 3." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 26 (2002): 89-104. [ Links ]

Pyeon, Yohan. You Have Not Spoken What Is Right About Me: Intertextuality and the Book of Job. StBibLit 45. New York: Peter Lang, 2003. [ Links ]

Schmid, Konrad. "Innerbiblische Schriftdiskussion im Hiobbuch." Pages 241-261 in Das Buch Hiob und seine Interpretationen: Beiträge zum Hiob-Symposium auf dem Monte Veritá vom 14.-19. August 2005. Edited by Thomas Krüger et al. AThANT 88. Zürich: TVZ, 2007. [ Links ]

Schoentjes, Pierre. Poétique de l'ironie. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2001. [ Links ]

Schwienhorst-Schönberger, Ludger. Ein Weg durch das Leid: Das Buch Ijob. Freiburg i.Br.: Herder, 2007. [ Links ]

Seow, Choon L. Job 1-21: Interpretation and Commentary. Illuminations. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013. [ Links ]

Sperber, Dan. "Verbal Irony: Pretence or Echoic Mention?" Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 113 (1984): 130-136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.113.1.130. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, Pieter. Rhetorical Criticism and the Poetry of the Book of Job. Oudtestamentische Studiën 32. Leiden: Brill, 1995. [ Links ]

* Submitted: 17/10/2019; peer-reviewed: 02/04/2020; accepted: 15/04/2020. Tobias Häner, "Job's Dark View of Creation: On the Ironic Allusions to Genesis l:l-2:4a in Job 3 and their Echo in Job 38-39," Old Testament Essays 33 no. 1 (2020): 266 - 284. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2020/v33n2a7. This study is part of a research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project number M2395-G24.

Dr Tobias Häner is a senior researcher at the Department of Biblical Studies of the University of Vienna, Austria. Email: tobias.haener@univie.ac.at. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5573-4189.

1 From the abundance of research on the intertextual connections between the book of Job and the books of the Hebrew Bible, let me mention Konrad Schmid, "Innerbiblische Schriftdiskussion im Hiobbuch," in Das Buch Hiob und seine Interpretationen: Beiträge zum Hiob-Symposium auf dem Monte Veritá vom 14.-19. August 2005 (ed. Thomas Krüger et al.; Zürich: TVZ, 2007), 241-261; Katharine J. Dell and Will Kynes, eds., Reading Job Intertextually (New York: T & T Clark, 2012); JiSeong J. Kwon, Scribal Culture and Intertextuality: Literary and Historical Relationships between Job and Deutero-Isaiah (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016).

2 Michael Fishbane, "Jeremiah IV 23-26 and Job III 3-13: A Recovered Use of the Creation Pattern," VT 21 (1971): 153-155.

3 Fishbane, "Jeremiah IV 23-26 and Job III 3-13," 153.

4 Leo G. Perdue, "Job's Assault on Assault on Creation," HAR 10 (1986), 307-308; Leo G. Perdue, Wisdom in Revolt: Metaphorical Theology in the Book of Job (Sheffield: Almond Press, 1991), 91-103; Leo G. Perdue, "Metaphorical Theology in the Book of Job: Theological Anthropology in the First Cycle of Job's Speeches (Job 3; 6-7; 910)," in The Book of Job (ed. Willem A. M. Beuken; Leuven: University Press, 1994), 142-149.

5 Perdue, Wisdom in Revolt, 98.

6 Perdue, Wisdom in Revolt, 95.

7 Perdue, Wisdom in Revolt, 98.

8 Valerie F. Pettys, "Let there be Darkness: Continuity and Discontinuity in the 'Curse' of Job 3," JSOT 26 (2002): 94-100.

9 Pettys, "Let there be Darkness," 103.

10 Yohan Pyeon, You Have Not Spoken What Is Right About Me: Intertextuality and the Book of Job (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), 88-95.

11 Andrea Beyer, "Hiobs Widerworte: Die Querbezüge zwischen Ijob 3,3-9 und Gen 1,1-2,4a," BZ 55 (2011): 95-102.

12 Beyer, "Hiobs Widerworte," 95.

13 Beyer, "Hiobs Widerworte," 98.

14 Samuel E. Balentine, Job (Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2006), 84.

15 Balentine, "Job and the Priests: 'He Leads Priests away Stripped' (Job 12:19)," in Dell and Kynes, Reading Job Intertextually, 44-48.

16 David J. Clines, Job 1-20 (Waco: Word Books, 1989), 81.

17 Melanie Köhlmoos, Das Auge Gottes: Textstrategie im Hiobbuch (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1999), 362 (note 4).

18 Schmid, "Innerbiblische Schriftdiskussion," 244-248.

19 "Damit die Stabilität der Welt erhalten bleibt, soll der Tag seiner Geburt gestrichen werden. (...) Die Welt und ihre kalendarische Ordnung, ist Hiobs Geburtstag einmal daraus eliminiert, bleiben intakt." (Schmid, "Innerbiblische Schriftdiskussion," 245247).

20 JiSeong J. Kwon, "Divergence of the Book of Job from Deuteronomic/Priestly Torah: Intertextual Reading between Job and Torah," SJOT 32 (2018): 64 (note 59).

21 Structurally, Job 3 is divided into three cantos (vv. 3-10, 11-19 and 20-26), cf. Pieter van der Lugt, Rhetorical Criticism and the Poetry of the Book of Job (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 50-60; Gianni Barbiero, "The Structure of Job 3," ZAW 127 (2015).

22 Fishbane, "Jeremiah IV 23-26 and Job III 3-13," 154 notes that the verb נוח that is used in Job 3:13, 17, 26 refers to God's rest at the seventh day in Ex 20:11 (וינח ביוםהשביעי); between Gen 2:1-3 and Job 3, however, there are no lexical correspondences.

23 "Darkness" is expressed in Job 3:3-10 by the following nouns: חשך vv. 4, 5, 9; צלמות v. 5, אפל v. 6.

24 On the parallels between Jer 20:14-18 and Job 3 cf. Gisela Fuchs, "Die Klage des Propheten: Beobachtungen zu den Konfessionen Jeremias im Vergleich mit den Klagen Hiobs. Erster Teil," BZ 41 (1997): 212-228; Edward L. Greenstein, "Jeremiah as an Inspiration to the Poet of Job," in Inspired Speech: Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. Essays in Honour of Herbert B. Huffmon (ed. John Kaltner and Louis Stulman; London: T & T Clark, 2004), 98-110.

25 "Cursing" is expressed literally in Job 3:2 (קלל), in v. 3 instead אבד ("to perish") is used, whereas Jer 20:14 has ארר ("to curse").

26 Identical vocabulary is marked with an unbroken line, semantic similarities are signaled by a dashed .line.

27 Fuchs, "Die Klage des Propheten," 223.

28 Greenstein, "Jeremiah," 103.

29 Clines, Job 1-20, 77.

30 Choon L. Seow, Job 1-21: Interpretation and Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 336.

31 Heinrich Lausberg, Handbuch der literarischen Rhetorik: Eine Grundlegung der Literaturwissenschaft (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2008), 302-303, 446-450.

32 On verbal irony cf. Douglas C. Muecke, Irony and the Ironic (London: Methuen, 1982), 56-65; Pierre Schoentjes, Poétique de l'ironie (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2001), 75-99.

33 On the Socratic irony cf. Dilwyn Knox, Ironia: Medieval and Renaissance Ideas on Irony (1989), 97-138; Schoentjes, Poétique de l'ironie, 31-47.

34 On the dissimulatio and simulatio see also Wolfgang G. Müller, "Ironie, Lüge, Simulation, Dissimulation und verwandte rhetorische Termini," in Zur Terminologie der Literaturwissenschaft: Akten des IX. Germanistischen Symposions der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft, Würzburg 1986, (ed. Christian Wagenknecht; Stuttgart: Metzler, 1989), 193-204, who points out that both kinds of irony - but in particular the simulatio - may occur by means of a vast range of figures of speech, such as the imitatio or the permissio.

35 René Nünlist, "Rhetorische Ironie - Dramatische Ironie. Definitions- und Interpretationsprobleme," in Zwischen Tradition und Innovation: Poetische Verfahren im Spannungsfeld Klassischer und Neuerer Literatur und Literaturwissenschaft (ed. Jürgen P. Schwindt; München: Saur, 2000), 80.

36 "βέβληαι κενεώνα διαμπερές, ούδε σ' όΐω | δηρόν έτ' άνσχήσεσθαι/ έμοί δε μέγ'εύχος έδωκας. | τον δ' ού ταρβήσας προσέφη κρατερός Διομήδης- | ήμβροτες ούδ'έτυχες· άτάρ ού μεν σφώΐ γ' όΐω | πριν άποπαύσεσθαι, πριν ή' ετερόν γε πεσόντα ..." (Iliad 5:284-288). The translation above is based on Homer, Iliad (trans. Augustus T. Murray and William F. Wyatt; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924).

37 Dan Sperber, "Verbal Irony: Pretense or Echoic Mention?," Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 113 (1984): 130.

38 Edgar Lapp, Linguistik der Ironie (Tübingen: Narr, 1997), 146.

39 Cf. Lapp, Linguistik der Ironie, 81.

40 Marika Müller, Die Ironie: Kulturgeschichte und Textgestalt (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1995), 177-212.

41 On the term of parody cf. Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000).

42 Othmar Keel, Jahwes Entgegnung an Ijob: Eine Deutung von Ijob 38-41 vor dem Hintergrund der zeitgenössischen Bildkunst (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978), 51-125, 159.

43 Cf. e.g. Hans-Jürgen Hermisson, "Notizen zu Hiob," ZTK 86 (1989): 126; Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger, Ein Weg durch das Leid: Das Buch Ijob (Freiburg i.Br.: Herder, 2007), 224; Beyer, "Hiobs Widerworte," 102.

44 A list of lexical correspondences between Job 3 and 38-39 (and also 40:6-41:26) is provided by Klaudia Engljähringer, Theologie im Streitgespräch: Studien zur Dynamik der Dialoge des Buches Ijob (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2003), 30-31.

45 In Job 3:3-10, three different terms of "darkness" are used that occur altogether five times (see above C.3).

46 In all 16 occurrences in the HB except Job 38:2, the verb חשך is used non-metaphorically. Additionally, besides Job 38:2, חשך in the hip'il stem usually has God as subject (Jer 13:16; Amos 5:8, 8:9; Ps 105:28; only in Ps 139:12, where the verb is negated, the noun חשך functions as subject).

47 With Clines, Job 1-20, 86, I don't follow the proposal of - among others - William F. Albright, "Rezension Gustav Hölscher: Das Buch Hiob (1937)," JBL 57 (1938): 227, to emend יום (day) in Job 3:8 to ים (sea), and to claim here a reference to the sea-god Yam of Canaanite mythology.

48 The motivic link is corroborated by lexical correspondences, as e.g. Job 38:8 shares with 3:10-11 the use of דלת (plur.), רחם, and יצא, whereas 38:29 takes up the verb יל ד and the locution יצא מבטן from 3:3 and 11.

49 This allusion is corroborated by the recurrence of the noun מספר (Job 3:6) in 38:21 and of the verb ספר in 38:37; furthermore, the motif of measuring time is present also in 38:31-33.

50 Further lexical correspondences in this context are כח (Job 3:17; 39:11), יגיע (3:17; 39:11, 16), חפשי (3:19; 39:5), עבד (3:19; 39:9).