Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.32 n.3 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n3a8

ARTICLES

Contrastive Characterization in Ruth 1:6-22: Three Ways to Return from Exile

Timothy L. Decker

Blue Ridge Institute for Theological Education/Irbs Theological Seminary

ABSTRACT

By using the narrative device of contrastive characterization, the author of Ruth demonstrates three return-from-exile scenarios that act as a model for the audience. Orpah served as Ruth's foil and represents a return to the pagan culture. Naomi and Ruth project a role reversal. While Naomi returns more like a pagan than a Jewess, Ruth has demonstrated covenant fidelity and illustrated loyalty to YHWH and Israel. She is thus a model for how Jews ought to return from exile to exodus.

Keywords: Contrastive Characterization, Exile, Covenant Loyalty

A INTRODUCTION

Even a dry, drab introduction to the book of Ruth has elicited the notice of rhetorical devices and literary ploys to develop a setting and move the story forward.1 One should not only expect that trend to continue after the "dull" setting but perhaps even increase by ways such as dynamic character development. In fact, reading the book of Ruth as a coherent narrative would not only point to character development individually, effective literary writing would prompt the readers to characterize the major players against their foils.2That is, the narrator develops one character by that character's contrastive counterpart. From this method of characterization, the author can stress for the audience distinctive features that are theological and applicable elements of the narrative.

This is not always the way scholars treat the book of Ruth. A survey of commentaries and articles would demonstrate that some models of interpretation focus its attention on other matters of the book, many of which are worthy for exegesis, to be sure. For example, some labour at the historical critical matters of the oral forms and redacted developments in the overall composition.3 Others stress the event described in the narrative, seeking to get behind the text and use socio-cultural concepts to elaborate the story.4 Some have argued for a missiological reading,5 which is not too terribly far from a redemptive-historical hermeneutic.6 Considering it appears in very important places in various canonical orders, canonical criticism plays an important role in Ruth's interpretation.7 More recently, feminist readings have dominated the field of Ruth studies.8 But perhaps the most promising and more often used method for interpretation is that of literary or narrative criticism.9 Since the genre of Ruth is taken in some way to be story (whether myth, folktale, novella, or short story),10the key features of a literary piece must be given its due weight in order for one to appreciate the story's fullest expression. One of these prominent features of a literary narrative such as the book of Ruth is the characterization of its major (and minor) players.11 And as Francis Rossow asserted, "The author's skill at characterization in the Book of Ruth is sufficiently noteworthy to be singled out for attention."12

Such an example follows directly after Ruth's opening in 1:1-5. After setting the three women in almost perfect congruence both in their narrative situations of life (and death) as well as the literary elements of the opening scene of 1:1 -5, the author then switches this parallelism with sharp distinctions beginning in 1:6. First, Naomi's husband died in v. 3, and then the two daughters-in-law's husbands die in v. 5. The narrator announced both deaths in the same way with the same grammar and syntax using the narrative form (יָּ֥מָת ; וַיָמָּ֥וּתוּ). In v. 3, Naomi was left or bereft (וַיָמָּ֥וּתוּ) along with her two sons. Similarly, in v. 5, Naomi again was bereft (וַיָמָּ֥וּתוּ) but now of her two sons and her husband. The author even presented Orpah and Ruth in parallel fashion in v. 4 linked together as "Moabite wives" (נָשִׁי ם֙ ֹֽ מאֲבִׁיּ֔וֹת) with their names given in the syntactically same and succeeding order.

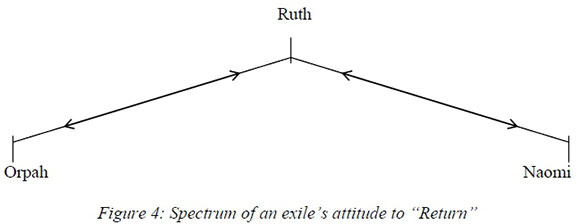

However, by way of literary analysis, a focus on the contrastive characterization of Orpah, Ruth and Naomi runs throughout Ruth 1:6-22 and will bring to the surface tensions among the three women.13 The author worked such differences as a foil for each of the three characters and linked them around Ruth: Orpah to Ruth and Ruth to Naomi. The contrast not only advances the narrative plot in the book of Ruth but also serves to highlight an Exodus motif relevant for any generation living under the curse of exile outlined in the stipulations of the Mosaic covenant of Deut 28. This also makes it a fitting appendix to the book of Judges.

No matter when an interpreter dates the book of Ruth, the abiding value of these contrastive characterizations transcends the Sitz im Leben of the original audience and has theological relevance to any audience of any generation. As a result, through literary-critical means of contrastive characterization, the narrative in Ruth 1:6-22 demonstrates the possibility of returning from exile in three different ways: backwards in apostasy (Orpah), blessed in covenant (Ruth), or bitter in emptiness (Naomi). Of course, the pragmatics of the text encourages the second of the three.

B CONTRASTIVE CHARACTERIZATION IN RUTH 1:6-22

The narrator thus far (Ruth 1:1-5) gapped the story with no explanations of death or famine, and more glaringly, no discourse. The author simply stated these tragedies almost matter-of-factly without any dialogue or speech. The pace of vv. 1 -5 occurs at break-neck speed leaving no space for the characters to mourn. That all quite remarkably changes in Ruth 1:6-22. As a demonstration of this passage's contrastive nature, Matthew Michael astutely noted, "What makes this important scene rare if not unique in the Hebrew Bible is that the persuasion takes places between three female characters... The interaction in Ruth 1 is particularly intense between Ruth and Naomi who voice two different positions."14

On the heels of the famine and tragic deaths of the patriarch Elimelech and his two sons, Naomi and her two daughters-in-law rise and return from the fields of Moab (Ruth 1:6a). Strangely, the narrator places the action to return prior to describing the logic of the action. The audience is drawn in inquisitively as they try to understand why it is that the three women rise and return from Moab. It is only subsequent to the act of returning that the author reveals to the reader that the news of relief found its way to the ears of Naomi (1:6; lit. "because she heard in the field of Moab that YHWH had visited his people"). Such an odd chronological displacement forces a repetition of "fields of Moab" in Ruth 1:6, causing the reader to twice reckon with Naomi's harsh reality that she was "in" the fields of Moab and eventually returns "from" the fields of Moab. This peculiar order of development in Ruth 1:6 also puts the good news of restoration second in sequence so as to place the thematic word "return" at the forefront of Ruth 1:6-22. As to that restoration, the author eloquently summarized the visitation of YHWH with alliteration and assonance (לָ תֵ֥ת לָהֶֶ֖ם לָָֽחֶם; lãtêt lãhem lãhem; lit. "to give to them bread") underscoring Israel's return to covenant faithfulness and blessing consistent with the stipulations of Deut 28. However, the narrator left unexplained the nature of this grace of YHWH, which is consistent with the setting of the book of Ruth.

1. "Return" as a Plot Device in Ruth 1:6-10

The author concentrated twelve of the fifteen incidences of the verb "return" (שׁוּב) in the book of Ruth to 1:6-22. This overtly repeated word forms an inclusio and theme for this narrative portion. The author placed it out of chronological order at the head of Ruth 1:6 (as well as a second time in 1:7) and twice again in Ruth 1:22 where both Naomi and Ruth are said to have "returned from the fields of Moab". Since much of the period of the Judges and thus the book of Ruth is placed in a Deuteronomistic historical development, the theme of exile and return is not too far from the minds of the original Hebrew audience.15 Among many definitions listed, BDB emphasized the nature of שׁוּב was to "return... especially from foreign lands."16 DCM concurred with its primary meaning as to "go back, return to a place... one's land of origin, ancestral land."17 Gladson added, "In Ruth, the repetitive שׁוּב underscores the necessity of the characters to find a way back from exile, famine, loss of family, and loss of future, to fullness or wholeness. At one level, then, the book is about exile and return."18

The journey from exile back into the land is reminiscent of the Exodus event. Just as Israel had to pass through Moab opposite Jericho before entering the Promised Land, so also will Naomi along with Orpah and Ruth experience an Exodus-like "return" of their own from the fields of Moab. The author elaborated this theme by the purposive use of the infinitive "to return" לָשֶׁ֖וּב as well as the object "to the land of Judah" (אֶל־אֶֶ֥רֶץ יְהוּדָָֽה). This was no subtle figure of speech but rather a blatant reference to the theme of exile to exodus. What is stranger still is how the author can include both Ruth and Orpah with Naomi in this "return" since, by all assumptions, neither have ever been to Judah being native Moabite women. The author stated this inclusion twice for emphasis in Ruth 1:7. First, with singular verbs and pronouns Naomi was said to have departed. Yet a disjunctive waw is used in order to include the Moabite daughters ("and her two daughters-in-law with her;" וּשְׁ תֶ֥י כַלֹּתֶֶ֖יהָ עִמָָּ֑הּ). The function of the disjunctive is to help set off the natural return for Naomi from her foreign daughters-in-law who are joining her. The second part of 1:7, however, matches the opening verb of the verse in form and stem yet is plural so as to include Naomi with Ruth and Orpah ("and they went out... to return;" לָשׁ֖וּב... וַ תלַַ֣כְנָה). Now the narrator joined the three of them together on their "return" to the Promised Land despite the fact that only one of them had ever been there before.

The narrator did not resolve such a geographical contradiction, which only leaves the reader to speculate. But since the Mosaic covenant and the theme of exile and exodus are prominent features already, it may not be a stretch to understand both Ruth and Orpah as having joined the covenant community as Gentile proselytes, even formally so through their marital union to Jewish men. It is in this way that they can "return" to a land that they have never set foot in, a land promised to a people in covenant with YHWH.19 Up to v. 7, the redeeming feature of the tragedy is that Naomi is seemingly fulfilling the Jewish mission to be a kingdom of priests and light to the nations. This makes the halt in the journey and the first speech in the book difficult to comprehend. Fentress-Williams said of the syntax of the beginning of Ruth 1:8,

The verse begins with the conjunction waw that is translated as 'but,' indicating the contrast between the departure for home and Naomi's words, which reflect a delay in the action, and a change in plans. The conjunction signals more than a simple shift in the narrative; this particular time it introduces the moment when a decisive movement takes place.20

What started as hopeful quickly turned to despair.

The narrator does not state what prompted Naomi to command Orpah and Ruth to return to Moab.21 What is more, Naomi's reasons for sending her daughters-in-law away are even more elusive. Some point to the traditional model of a widow returning to her father's house (cf. Ge 38:11, Lev 22:13).22This seems strained since, as many feminist interpreters like to point out, Naomi advised them to return to the house of their mother ((לְ בַ֣ית אִמָָּ֑הּ).23 Perhaps knowing she was able to provide neither sustenance nor sons to marry, Naomi sought to send them away for the sake of self-preservation.24 Another theory posits that Naomi knew Ruth and Orpah's lot would fall easier in Moab than Israel.25 If deemed an act of kindness, one may wonder why Naomi invoked YHWH's chesed (חֶֶ֫סֶד) in a blessing to send them away.26 Not so uncontroversial, some have argued that Naomi's motivation was due to the desire to avoid embarrassment and ridicule from the exposure of the moral indiscretion of her sons to intermarry with the Moabites.27

Whatever the specific case may be, the irony thickens when considering Naomi is sending her daughters-in-law back to Moab whose god was Chemosh all the while invoking blessings in the name of YHWH (Ruth 1:8b-9).28 At this juncture, one may surmise that the Moabite widows had proselytized to the covenant community by virtue of their return to the Promised Land as well as the invoking of YHWH's "covenant-faithfulness" (חֶֶ֫סֶד) and "rest" (מְנוּחָה), themes vitally central to the people of Israel in covenant with YHWH. This also serves to explain their decline to Naomi's offer in v. 10. This time, they take the word "return" (נָשֶׁ֖וּב) on their own lips. It is at this point that Naomi has to offer reasons for their separation.

2. Orpah and Ruth as Contrastive Characters (Ruth 1:11-15)

While it is clear that the questions Naomi put forward to Orpah and Ruth are rhetorical (Ruth 1:11-13), what is less obvious is the strategy involved. On the surface, it appears that she is making a rational case in that it "would make no sense whatsoever for Ruth or Orpah to stay with her."29 However, it could just as easily be a description of her dismal plight and statement hinting at Naomi's future of bitterness.30 Some go so far as to see Naomi as a negative model, hoping that her moral duress would evoke in the daughters a desire to leave.31 For all of her efforts, Naomi was only 50% successful in her words of persuasion.

While Orpah was fully convinced to kiss Naomi goodbye, Ruth clung to her (Ruth 1:14). It is this very distinction that causes the reader to understand Orpah and Ruth as contrastive characters.32 Thus Hyman asserted, "Ruth's action stands in contrast to Orpah's. Orpah, Ruth's foil, is not bad or disrespectful... Rather, Ruth, in contrast, is shown to be exceptionally good."33 While his positive assessment of Orpah will be disputed below, Hyman's noting of the contrastive character device confirms the argument here.

Despite the desire of some who want to understand Ruth's action of clinging to Naomi as a subtle sexual gap in the narrative,34 the contrast in v. 14 is between Orpah's decision leave versus Ruth's decision to remain.35 Though nothing is stated of Orpah's outcome beyond Naomi's words in v. 15, her decision alone places "her role in the narrative as a foil for Ruth."36 In fact, it is in the hiddenness of Orpah's decision that is most contrastive in comparison to Ruth. The narrator left the reader to infer that Orpah took Naomi's advice to depart in v. 14 by the intratextual action of Naomi's kiss previously in v. 9 ("and she kissed them;" וַתִשַַ֣ק לָהֶֶ֔ן)leading them to lift up their voices and cry ( וַתִשֶֶ֥אנָהקוֹלֶָ֖ן וַתִבְכֶָֽינָה).Inversely, v. 14 begins with their voices lifting and weeping again (וַתִשֶַ֣נָה קוֹלֶָ֔ן וַתִבְכֶֶ֖ינָה עָּ֑וֹד)and ends with Orpah alone kissing her mother-in-law (וַתִשַַּׁ֤ק עָרְפָ ה לַחֲמוֹתֶָ֔הּ).Contrast this with Ruth, who instead clung to Naomi and gave a lengthy speech in order to convince her to remain. Thus, Hawk rightly noted, "The report of weeping and kissing, now repeated but in reverse order, draws a vivid contrast between Orpah's and Ruth's responses to Naomi's admonition" (italics added).37

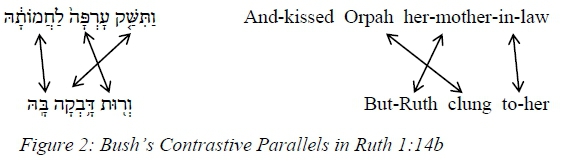

Frederic Bush noted another literary contrast in the final half of v. 14. He wrote, "In the Hebrew, [Ruth's] action is strongly contrasted with that of Orpah's by the inversion of the subject and object."38 He illustrated this as:

Not only are the two actions (Orpah kissed; Ruth clung) semantically in contrast with one another, but their places in the sentence are at odds as well.

The narrator's subtlety in Orpah has caused a division among interpreters. How should one understand her decision to leave, either positive or negative? Or to ask it another way, was Orpah right or wrong to obey Naomi and return to Moab? Given the silence of the author, this gap draws the readers in to speculate various scenarios.39 While some have cautioned interpreters from drawing conclusions upon Orpah's decision,40 others come right out and say that Orpah did not act wrongly.41 In fact, it has been argued by some feminist interpreters that Orpah acted courageously despite the tensions she was facing.42 For instance, Phyllis Trible claimed, "Orpah is a paradigm of the sane and reasonable; she acts according to the structures and customs of society. Her decision is sound, sensible, and secure."43 Perhaps as a narrative device, the reader must strain to find fault in Orpah, considering she was following the instruction of her mother-in-law, who so forcefully asserted that both daughters return to Moab. From the perspective of self-interest and personal welfare, Orpah was more likely to survive in the house of her mother.

However, what seems to so many an obvious contrast would lose its value if readers interpreted Orpah's return as either positive or even neutral. Since Naomi has already invoked YHWH's covenantal-faithfulness and rest upon Orpah, it is telling that Naomi explained to Ruth that Orpah has returned to both her people and her god (שַָׁ֣בָה יְבִמְ תךְ אֶל־עַמֶָ֖הּ וְאֶל־אֱלֹהֶָּ֑י)in verse 15. As will be argued later in v. 16, the use of "people" and "god" in relation to one another is covenantal in nature.44 For Orpah, returning to the people of Moab and to the gods of Moab is tantamount to reneging on the covenant she seemed to have enjoined herself. The vivid insinuation is that she apostatized back to her former life. Therefore, the narrator's silence on the part of Orpah in v. 14 was contrastively outspoken in v. 15.45

The readers further feel the contrast between the two sisters-in-law by not only observing their glaring differences but also in noting their clear similarities. Obviously, two Moabite women marrying a pair of Jewish brothers bring Orpah and Ruth together, as Ruth 1:4 clearly does.46 Initially, they are both returning to Judah, though neither has been there. And initially, they refuse Naomi's plea to return to Moab. Nevertheless, Orpah the Moabitess indeed returned to the people of Moab and the gods of Moab, whereas Ruth clung to Naomi and claimed "your people, my people; your God, my God" (עַ מַ֣ךְ עַמִֶ֔י ואלֹהֶַ֖יִךְ אֱלֹהָָֽי) in the following verse. Thus, Orpah returned backwards into her paganism, whereas Ruth remained faithful to the covenant and demonstrated covenant-faithfulness (חֶֶ֫סֶד), as Boaz would recognize later (Ruth 3:10).47 This contrast serves not only to highlight the distinction between Ruth and Orpah, but it also propels Ruth' s contrast with Naomi later. If the narrator depicted Orpah as the apostatizing pagan, then Ruth is the faithful Gentile proselyte.

Finally, should the readers understand Orpah's actions negatively and in contrast to Ruth's abiding covenantal loyalty, this raises an ethical issue for Naomi as well. If Orpah was to blame for apostatizing, then Naomi should also and rightly shoulder some of that blame for commanding her to return to Moab and even invoking the name of YHWH to do it! It was, after all, following upon her insistent admonitions that Orpah returned to Moab, though Orpah originally desired to stay with Naomi. While one would expect a pious Jew to be a beacon of light guiding the nations to the presence of God toward the tabernacle/temple, the narrator presented Naomi as one like a pagan directing people away to the nations. This role reversal for Naomi will play later into the contrastive element in her characterization with Ruth. Indeed, the contrast between Orpah and Ruth serves to set up the greater contrast between Ruth and Naomi.

3. Ruth and Naomi as Contrastive Characters (2:16-22)

Perhaps the sharpest contrast, and certainly the longest of chapter 1, is between Ruth and Naomi. It is not coincidental that the narrator cast both Ruth and Naomi's reply in poetic form to add contrastive value to their words (Ruth 1:1617, 20-21).48 It is, however, challenging to use the word "foil" for either Ruth or Naomi, since that usually connotes a minor role for the foil character. Nevertheless, the way the author depicted Naomi negatively by sending Orpah back to paganism while Ruth has maintained covenantal-loyalty by clinging to Naomi, even before Ruth's great poetic plea to Naomi, the narrator has already projected these two prominent women at odds with one another.

Beginning with Ruth's petition in 1:16-17, one must see the elements of her requests in its poetic and covenantal light. Beyond the semantic and syntactic parallelism of the "go" and "lodge" statements,49 the poetic device of heightening or sharpening,50 in this case, brings out its covenantal features. As scholars have noted, formulaic to Israel's covenant with YHWH is to follow the idea "I will be your God, and you will be my people."51 Rendtorff noted nearly forty occasions in the OT where this covenant formula appeared in one of three similar forms.52

Smith expanded on the initial observations of others and sought even more indications of covenantal language in Ruth's commitment to Naomi.53

It is telling, then, that Ruth would commit to Naomi using language such as "your people, my people; and your God, my God" (עַ מךְ עַמִי ואלֹהַיִךְ אֱלֹהָי).54This moves past the simple language of conversion, though that certainly is present. Campbell noted, "The striking thing about the theology of the Ruth book, however, is that it brings the lofty concept of covenant into vital contact with day-to-day life, not at the royal court or in the temple, but right here in the narrow compass of village life."55 What is more, according to Smith, Ruth is even going beyond ethnic conversion of joining the covenant community of Israel. "Ruth's words represent the covenant relationship across family lines that have been sundered by the death of the male who had linked the lives of Ruth and Naomi."56 Ruth's poetic language vocalizes her conversion to YHWHism, the people of Israel, and the family of Elimelech when it was only intimated before. Though the narrator called her "Ruth the Moabitess" six times (1:4, 22, 2:2, 21, 4:5, 10), this poetic and covenantal declaration in Ruth 1:16-17 envisions her as Ruth the Jewess. It is significant that the name "Ruth" appears a total of 12x's in the book of Ruth. While the author linked her Moabite heritage half of those times, by virtue of her name, she was depicted as fully engrafted into the twelve tribes of Israel, particularly Judah.

The scholars dispute when or even if Ruth's ethnic conversion took place. Recently, Neil Glover argued that taking Ruth 1:16-17 as the point of ethnic conversion was "alarming naivety".57 In his utilization of comparative methods of anthropology, he argued that it was not until chapter 4 that Ruth was fully converted into the community and considered an Israelite. His main arguments were threefold: Ruth's final mention as simply "Ruth" without her "Moabitess" designation as the narrator neither called Naomi nor Boaz "the Israelite", Ruth's manipulation of Moabitess stereotypes in chapters 2 and 3, and her acceptance into the household by the witnesses of Bethlehem in chapter 4.58 From an anthropological view, this very well seems to be the case for the entire community. But the function of covenantal language on the mouth of a Gentile would have been extremely significant for a typical Israelite audience. This best explains Naomi's mute reaction and acquiescence (1:18). She is not simply giving in to Ruth's determination. She is recognizing the total transformation of Ruth. Therefore, from the vantage of Naomi and thus the reader's introduction to the idea, Ruth's inculcation into the community began at 1:16-17.

The cumulative effect of the entire speech from Ruth to Naomi is typically seen to be one of solidarity.59 Fewell claimed that "Affirming her willingness and ability to traverse whatever spatial, social, and existential boundaries necessary, Ruth takes her place alongside Naomi, even acknowledging YHWH's death-dealing temperament."60 This, in part, explains the use of transition between narrative prose and poetic dialogue as a means to increase the emotional temperature of the passage. It was this rise in emotion that Linafelt observed a contrastive tension between the poetry of Ruth and the poetry of Naomi. He said,

The two poetic speeches of Ch. 1, then, set up our two protagonists as the bearers of the fundamental tensions of the plot. One of those tensions is personal: Ruth has expressed a nakedly emotional commitment to Naomi, while Naomi has ignored that commitment and deemed herself 'empty' as she returns from Moab.61

Naomi's silent response further demonstrates the contrast. After the heightened literary form taken by Ruth, the reader might expect a reply in similar fashion either pleading for her to reconsider her loyalty or praise her for her loving-faithfulness. And rather than simply assuming Naomi's silence and moving on in the narrative, the author was sure to make the point directly adding "and she ceased to speak to her" (וַתֶחְדֶַ֖ל לְדַ בֶ֥ר אלֶָֽי ה). How much one is to read into the narrator's statement is part of the contrast between Ruth and Naomi.62As Hubbard well noted, "The storyteller wants the audience to feel either slight alienation between the two women, or Naomi's preoccupation with her painful, uncertain future."63 Feeling this tension, LaCocque claimed, "[O]ne also can understand it in a more radical sense: that she stopped speaking to her. does not betray her bad mood, but a deliberate discretion."64 Jan de Waard feared reading too much into this statement and cautioned, "This does not mean that she refused to talk to her any more, but simply that she ceased to urge her to return to Moab."65 If this were the case, it appears forced and redundant that the narrator would feel compelled to mention this after such a speech from Ruth.66 The effect of acquiescence on the part of Naomi would just as easily transmit to the audience without the explanation of stated silence, an irony unto itself.67

From the perspective of the audience, Naomi's silence is as much of a withdrawal as Ruth's poetic speech is a commitment.68 If withdrawal, then as Fewell and Gunn have argued, "Naomi's silence at Ruth's unshakable commitment to accompany her emerges as resentment, irritation, frustration, unease. Ruth the Moabite is to her an inconvenience, a menace even."69 This may be reading more into the simple grammar of the wording at the end of v. 18.70Nevertheless, whatever the extent of Naomi's frustration, her contrastive silence is deafening.71

Though Naomi was initially silent, upon entering Bethlehem she addressed the ladies inquiring about her. The people's rhetorical question "Is this Naomi?" is not to be taken to mean identification as if they did not initially recognize her. Rather it is a statement of shock at her miserable condition. Could a woman from such a pious and prosperous family72 return in such a poor and (as it will turn out) pagan fashion? This prompted Naomi to end her silence enacting her own sense of nomen est omen. Some have sought to draw a contrast between the meaning of her initial name as connoting "sweetness" (נָעֳמִי lit. means "my delight") with her new name "bitterness."73 More likely, her name is to be taken in respect to YHWH just as her husband's name Elimelech had (אֱלִימֶלֶךְ; lit. "my God is king").74 She had previously hinted at her bitter state in Ruth 1:13 ESV, "[I]t is exceedingly bitter to me" (מַר־לִַּׁ֤י מְאֹ). Now Naomi is ready to throw off her former name regarding YHWH as her pleasure and own her new appellation: "Do not call me Naomi. Call me Bitterness!" (אַל-תִקְרֶאנָה לִי נָעֳמִי קְרֶאן לִי מָרָא). Since this new nickname never appears again, it is likely that no one, including the narrator, agrees with Naomi's assessment.75

Not only does the meaning of her name signify her understanding of her relationship to YHWH, but the spelling is critical as well. While the Hebrew noun for "bitter" or "bitterness" is מָרָה (mãrâh), Ruth 1:20 recorded מָרֶָ֔א (mãrã).76 Some scholars point out the aleph ending as an Aramaic spelling, perhaps indicating a late date for Ruth.77 However, Campbell asserted "it is not technically an Aramaism (i.e., an influence from the Aramaic language)."78Scholars have considered other languages for its origin. Some have proposed either a Ugaritic source (or at least a very proximate Semitic/Canaanite influence)79 or even outright claimed it was from Moab itself.80 Others have simply considered it a scribal error or orthographic change.81 While both renderings are homophonic, the aleph ending would have caught the eye of the original Jewish reader.

Considered narratively along with the contrastive characterization between Ruth and Naomi, the aleph ending becomes extremely significant. While scholars are not all agreed as to the linguistic source of the ending change, the telling feature is that Naomi herself opted for a change away from the expected Hebrew rendering. In other words, she is communicating to the Bethlehemite women inquiring "Is this Naomi?" with a retort indicating both her segregated state regarding YHWH ("bitter") as well as from the Jewish people with a non-Jewish spelling.82 In direct contrast, these were the same two features of Ruth's covenantal poem ("my people" and "my God") that Naomi is stripping off.

We might liken Naomi's behaviour to a man named Owen who was from the US but lived abroad in Ireland for many years soaking up his Gaelic roots. Upon return to the US, he decided to spell his name Eóghan. Though pronounced the same, the spelling indicates his time away has affected him. For Naomi, her time among the pagan Moabites has negatively affected her. Contrastively then, while Ruth, the actual Gentile, is returning to Bethlehem for the first time in covenantal fidelity (or chesed)83as converted religiously to YHWH and filially to Elimelech's family, if not ethnically, as a Jewess; Naomi, the actual Jewess, is returning to Bethlehem in an exodus yet blaming YHWH for her empty lot and changing her name in line with Gentile influences. The roles have been reversed!

This spelling also opens the possibilities for double-entendre with her new name. After considering other Semitic languages, Sasson concluded that מרר (mrr; the verb form of "to be bitter" in Hebrew) is the best root with multiple meanings. He then said, "[W]e opt for a meaning that underscores the biblical writer's ability to play on words."84 He goes on to argue that such a root may indicate a secondary meaning of "'fierceness, strength,' and the like."85 This is less a literary angle and more of a synchronic-semantic one. From the perspective of the narrative, there may be a different play on words. Though מרא (mr) is not the proper Hebrew spelling for "bitterness," it is the Hebrew consonantal spelling for the verbs "be rebellious" or "beat, strike."86 Such a word play drips with irony as it indicates she is in open rebellion before YHWH for the way he has treated her. While one must not doubt that "bitterness" is the primary force of Naomi's new self-designation due to her explanation "that Almighty has dealt bitterly [from מרר]with me," the unusual spelling opens the door for puns and intentionally creates more contrast between the two widows.

Naomi's conveyed her disdain further when she resorted to an older title for Israel's God as "Almighty" or Shaddai (שַׁדַַּ֛י). Such use was popular before the Mosaic covenant87 as well as after the exile.88 Though she returns to the divine name YHWH twice in v. 21, she again reverted back to Shaddai. This chiastic use of God's title and name "contrast the bitter and sweet with affliction and emptiness."89 Could this play on the name of God indicate that she sees herself either still in exile or worse, as no longer in the covenant community between God and Israel? If so, this would again put her at odds with Ruth's statement of "my people" and "my God."

Terrance Wardlaw emphasized other elements that have significance here. First, he noted that the word-play Shaddai (שדי) has on the Hebrew word for "destruction" (שדד), as if Naomi were ratcheting up her misery even higher.90Second, it is fitting that Shaddai be invoked for its patriarchal use (El Shaddai) to provide a seed as God promised both for Israel as well as the means to bless the nations (like Moab).91 Though this points forward to the outcome of Ruth, in chapter 1 of the narrative, Naomi places herself in a period before the Mosaic covenant.

Additionally, in only two verses, she lobs the blame toward God 3x's: "Shaddai has dealt bitterly with me," "YHWH brought me back empty," and "Shaddai has caused calamity upon me." In each of these three negative phrases, the author used three hifil verbs to highlight the causative force of God behind these elements. And while she is theologically correct in her assessment, akin to Isa 45:7,92 her tone is far from worshipful. The author indicated this by the contrasting three positive verbs in the qal stem: "I went full," "why call me Naomi?" and "YHWH testified93 against me." Within her accusation against God, Block noted further contrasting elements in v. 21:

Naomi added a double volley against YHWH, constructed with modified chiastic contrastive parallelism.

By inserting the subject pronoun (I) - which is syntactically unnecessary - and placing the subjects at the extremities of the two clauses Naomi pitted herself against YHWH. But she has also highlighted the fullness-emptiness contrast by placing adverbial expressions before the verbs in each case.94

Thus, Naomi ended her poem with a self-contrast which distanced her not only from the Israelite community leaving full yet returning empty but even from the covenant God YHWH by distancing herself ("I") as far away as possible from YHWH.

Finally, in terms of the narrative structure one may read the last verse of the chapter in one of three ways. First, it concludes the chapter as written.95Second, some or all of it is understood as an introduction to the next phase of the tale.96 Third, it serves somewhat a dual role of completing the final section as well as linking it to the next phase of the narrative.97 The third option is the most attractive since Ruth 1:22 seems both to hint at the narrative setting in chapter 2 as 1:1 did for chapter 1 but also serves as an inclusio with 1:1's geographical and chronological statement about a man from Bethlehem moving to the fields of Moab (מִׁשְ דֵ֣י מוֹאָָ֑ב) because of famine. Only in 1:22 the author reversed the order mentioning first the fields of Moab (מִׁשְ דֵ֣י מוֹאָָ֑ב) and then entering Bethlehem at the time of harvest. The contrast between the famine in v. 1 and the beginning of the harvest in v. 22 is also telling. And as Hubbard was keen to point out, the opposite elements of leaving Bethlehem in a famine at the opening of the scene versus returning to Bethlehem at harvest in the closing of the scene heightens the contrastive elements throughout all of chapter 1.98

Though it seems inconsequential to some,99 v. 22 caps the contrast between Ruth in Naomi in dynamic fashion. The thematic word "return" is used twice not only to bracket off vv. 6 and 7's two occasions of "return," it also has for their subject Naomi and Ruth respectively. While both verbs are Qal perfect singulars,100 their grammatical similarities help to bear out the contrast further. The first "return" is in the narrative form, and the clause is short and sweet: "And Naomi returned" (וַתֵָ֣שָב נָעֳ).The author, however, introduced Ruth with a conjunction and gave her every appellative possible: "and Ruth the Moabitess her daughter-in-law with her, who returned" (וְר֨וּת הַמוֹאֲבִָיַּׁ֤ה כַלָתָ הּ עִמֶָ֔הּ הַשֶָ֖בָה).101Not only was the second statement of v. 22 contrastively much longer, but the words and syntax related Ruth backwards to Naomi but also forwards on her own return. Bush maintained that the structure and syntax in v. 22 stresses Ruth over Naomi giving her return "remarkable prominence."102 Behind the text, there may or may not have been tension between these two widows. But in the text, the narrator stretched the distance between them to its literary limits.

C CONTRASTIVE CHARACTERIZATION IN THE REST OF THE BOOK OF RUTH

With the dense and profuse use of "return," the theme of exile seems specific to this section of Ruth. It is notable that by Ruth 2, the contrasting characterization between Ruth and Naomi is all but abandoned. The two widows are "in it together" so to speak. Naomi even reverts back to appearing more like a typical Jewish woman in the Promised Land. In this way, the contrasting characterization can act as a means to isolate Ruth 1:6-22 as a thematic sub-unit unto itself, albeit still tied with the themes throughout the rest of the book of Ruth. The characters, after all, do continue to move the story forward. And undoubtedly, the author demonstrated God's own chesed for both Ruth and Naomi with not only providentially providing a kinsman-redeemer to salvage their pitiable estate from chapter 1 but also with the proliferation of a seed leading to David.

Nevertheless, the author appears to restrict the exile motif and how those who have sworn covenant fidelity to YHWH in exile should return to this section in 1:6-22. And for some, this may even be sufficient evidence to offer a later dating for the book of Ruth.103 That such a thematic emphasis restricted to a brief section at the beginning of the story seems to say more to the community for which the author wrote rather than to help the flow of the narrative proceed. All things being equal, however, the book of Ruth as a whole is dependent on the elements of chapter 1, and the timelessness of this message, especially considering Israel perpetually in a revolving door to and from the Promised Land, fits most any community setting throughout Israel's history. Therefore, the theme of "return" as well as the contrastive characterization serves a unique purpose as a kerygma for any Jew away in exile or in a transition back to restoration. Putting aside the Davidic thrust of Ruth and its messianic connotations (as that would have a tremendous bearing on the state of mind for any Jew returning from exile at any time period), the sermonic element in this text is how an exile in foreign, pagan isolation should return to the Promised Land in restoration back just as YHWH had promised according to his chesed.

Some, like Orpah, may refuse to return at all and thus depart not only from the narrative but apostatize back to the pagan idolatry they had grown accustomed. Orpah's absence from the rest of the book of Ruth is concomitant with her status among the covenant people. Thus, she will serve not only as a foil to Ruth but also as a warning to any Israelite in exile. With Ruth being the central and (literally) pivotal role of contrast between Orpah and between Naomi, she is the epitome of what a faithful return from exile should look like. Her blessing reaches its climax in chapter 4 when the witnesses compared her to the matriarchs of the people of God, an astounding testimony considering her Moabite heritage.

Naomi, being the primary character of the book of Ruth, finds herself in an interesting presentation. The fairly negative portrayal of her in chapter 1 seems abandoned in the remaining three chapters. Even the theme of her bitterness has disappeared. The only possible negative presentation, which some of course debate,104 is her plan to send Ruth to the threshing floor of Boaz. Perhaps the gaps in that narrative with words that could ring either literally or euphemistically hint that the reader is to continue to struggle with Naomi's character. But by the end, Naomi has received a blessing of seed through Ruth, and she (not Ruth!) is named in the line of succession of David in Ruth 4:17. If there is a reversal and redemption to be observed, which is an understatement for the book of Ruth, Naomi fits the bill.

Therefore, the purpose of Ruth 1:6-22 as its own sub-unit and its contrastive element along with its return-from-exile theme works within the larger story of the book of Ruth. It brings the reader from a pit of despair in chapter 1 to a climactic conclusion in chapter 4 with the tense rising action in chapters 2 and 3. It is through the negative characterization of Naomi via the contrastive details in Ruth 1:6-22 that one can fully appreciate the full redemptive reversal. Conversely, Ruth's plight only improves with added blessing. She is faithful to her new family, people, and God. And she is repeatedly and remarkably blessed up to the end. She too was on an upward incline from chapters 1 to 4. The greater themes of Ruth only have their grander value due to the desperate situation as told in chapter 1.

D CONCLUSION

In his helpful book, From Exegesis to Exposition, Robert Chisholm offered an interpretive application from Ruth 1 saying the principle that arises is "Genuine love is risky and sacrificial." Furthermore the "Application idea: In contrast to the paradigm all around us, we should demonstrate genuine love by taking risks and placing the needs of others above our own."105 Such an application is well and good, commendable even. However, he builds on this by interpreting each character in isolation from the others. Ruth is simply a moral example for the audience to emulate. But this misses the rhetorical thrust of this passage, especially in light of their contrastive characterization.

The purpose behind the narrative features of contrastive characterization serves a homiletical point for the readers that is likely a sub-theme restricted to Ruth 1:6-22. One might even expect such a contextual limitation. Because so many of the narrative features of Ruth showcase the providence of God, his redemptive purpose, and the Davidic dynasty (and political overtones) from chapters 1 through 4, one would not expect the sub-theme of how one returns from exile to feature throughout the book of Ruth. However, it does serve its purpose for readers who are either in exile, at the end of exile, or fearing the prospect of exile. Deuteronomy ensures the people that YHWH's promise to bless his people if they repent and cry out is a guarantee that a return to the place of promise will occur. Ruth 1:6-22, on the other hand, puts the emphasis of how the people of God would respond to a return. Through the vehicle of contrastive characterization, the scene of Ruth 1:6-22 presents three distinct options that serve as a spectrum of extremes. The author presented two negative extremes, first in Orpah and later with Naomi. The former returned backwards into apostasy while the latter returned bitter in emptiness. Only Ruth returns blessed in covenant-faithfulness.

Orpah is a presentation of a person who was in the covenant community, albeit it marginally so, and decided to leave those commitments for what she perceived to be an easier life. Naomi is the opposite extreme. She returned loathing her lot in life as well as the deity who put her there. Though she has returned to the house of bread (Bethlehem) and the place of praise (Judah), nevertheless she was empty and bitter. Her appearance and even her name were more foreign to the covenant community than Ruth, the actual Moabitess who returned with her. And yet, despite this negative portrayal of Naomi in chapter 1, the audience receives comfort as they read beyond to see that YHWH can even redeem an empty and bitter situation such as Naomi's. All hope is not lost.

Ruth is the most illustrative of the three, with Orpah as Ruth's foil as well as her contrast with Naomi. As God commissioned Israel to be a kingdom of priests and a light to the nations, there is a sense of rejoicing that should take place as a Gentile is not only converting to YHWHism but even to ethnic identity with the Jews. And in spite of this, she returns with chesed (Ruth 1:8, 3:10) and under the blessing of YHWH's chesed (1:8; 2:11, 20). This pagan Moabitess served as the best example for a Jew in exile, for certainly if a foreigner who has joined the covenant community can return in such a way, then how much more for a true-born Jew to return in like manner. When the audience feels the contrastive characterization, they are not likely to miss the rhetorical force. Nor is it lost on the audience that Naomi represents the more likely of the negative scenarios. She becomes a warning for bitterness because restoration from exile is a blessing despite the circumstances that brought one there (such as Ruth 1:15).

Whether in the period of the Judges when Israel was in and out of the Promised Land or much later after the destruction of Solomon's temple, exile was part and parcel to the stipulations of the covenant between Israel and YHWH. Therefore, when Israel sinned and received punishment into exile, as assuredly as Moses knew they would (cf. Deut 31:16-21), their God would also assuredly restore them according to the stipulations of the covenant. And while the covenant stipulations of Deuteronomy demonstrate the certainty of their return upon their repentance, as partially observed in the return motif in Ruth 1:6-22; even more weighted through the literary feature of contrastive characterization, this passage was a means to encourage and warn the people how they should return: not backwards like Orpah, not bitter like Naomi, but blessed like Ruth.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative. Revised and Updated. New York: Basic Books, 2011. [ Links ]

-. The Art of Biblical Poetry. Revised and Updated. New York: Basic Books, 2011. [ Links ]

Auger, Peter. The Anthem Dictionary of Literary Terms and Theory. London: Anthem Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Baylis, Charles P. "Naomi in the Book of Ruth in Light of the Mosaic Covenant." BSac 161.644 (2004): 413-31. [ Links ]

Berquist, Jon L. "Role Dedifferentiation in the Book of Ruth." JSOT 18.57 (1993): 2337. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel I. Judges, Ruth: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. NAC. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 1999. [ Links ]

-. Ruth: A Discourse Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. ZECOT. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015. [ Links ]

Bovell, Carlos. "Symmetry, Ruth and Canon." JSOT 28.2 (2003): 175-91. [ Links ]

Brenner, Athalya, ed. Feminist Companion to Ruth. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Reprint. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2005. [ Links ]

Bush, Frederic. Ruth, Esther. WBC. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996. [ Links ]

Callaham, Scott N. "But Ruth Clung to Her: Textual Constraints on Ambiguity in Ruth 1:14." TynBul 63.2 (2012): 179-97. [ Links ]

Campbell, Jr., Edward F. Ruth: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes and Commentary. AB. New York: Doubleday, 1975. [ Links ]

Chisholm Jr., Robert B. From Exegesis to Exposition: A Practical Guide to Using Biblical Hebrew. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1999. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. A., ed. The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew. 8 vols. DCH. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Coxon, Peter W. "Was Naomi a Scold: A Response to Fewell and Gunn." JSOT 14.45 (1989): 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908928901404503. [ Links ]

Cross, Frank Moore. "Yahweh and the God of the Patriarchs." HTR 55.4 (1962): 22559. [ Links ]

Cundall, Arthur E., and Leon L. Morris. Judges and Ruth. TOTC. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008. [ Links ]

Curtis, John Briggs. "Second Thoughts on the Purpose of the Book of Ruth." Proceedings 16 (1996): 141 -49. [ Links ]

Davis, Andrew R. "The Literary Effect of Gender Discord in the Book of Ruth." JBL 132 (2013): 495-513. [ Links ]

Dearman, J. Andrew, and Sabelyn A. Pussman. "Putting Ruth in Her Place: Some Observations on Canonical Ordering and the History of the Book's Interpretation." HBT 27.1 (2005): 59-86. https://doi.org/10.1163/187122005x00040. [ Links ]

Decker, Timothy L. "Ruth 1:1-5: An Exegetical and Expositional Proposal."Conspectus 9.03 (2010): 33. [ Links ]

Fentress-Williams, Judy. Ruth. Abingdon OTC. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2012. [ Links ]

Fewell, Danna Nolan. "Space for Moral Agency in the Book of Ruth." JSOT 40.1 (2015): 79-96. [ Links ]

Fewell, Danna Nolan, and David M. Gunn. "'A Son Is Born to Naomi': Literary Allusions and Interpretation in the Book of Ruth." JSOT 13.40 (1988): 99-108. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908928801304006. [ Links ]

-. Compromising Redemption: Relating Characters in the Book of Ruth. Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2009. [ Links ]

-. "Is Coxon a Scold? On Responding to the Book of Ruth." JSOT 14.45 (1989): 39-43. [ Links ]

Fischer, Irmtraud. "The Book of Ruth as Exegetical Literature." EJ 40.2 (2007): 14049. [ Links ]

Freedman, Amelia Devin. "Naomi's Experience of God and Its Treatment in the Book of Ruth." Proceedings 23 (2003): 29-38. [ Links ]

Gesenius, Wilhelm. Gesenius'Hebrew Grammar. Edited by E. Kautzsch Translated by A. E. Cowley. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463213435-010. [ Links ]

Gladson, Jerry A. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Ruth. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012. [ Links ]

Glanzman, George S. "The Origin and Date of the Book of Ruth." CBQ 21.2 (1959): 201 -7. [ Links ]

Glover, Neil. "Your People, My People: An Exploration of Ethnicity in Ruth." JSOT 33.3 (2009): 293-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089209102498 [ Links ]

Goswell, Greg. "The Order of the Books in the Greek Old Testament." JETS 52 (2009): 449-66. [ Links ]

Grant, Reg. "Literary Structure in the Book of Ruth." BSac 148.592 (1991): 424-41. [ Links ]

Guyette, Frederick. "The Book of Ruth: Solidarity, Kindness, and Peace." Solidarity 3.1 (2013). [ Links ]

Hawk, L. Daniel. Ruth. Apollos OTC. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2015. [ Links ]

Holmstedt, Robert D. Ruth: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text. BHHB. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Hubbard, Robert L. The Book of Ruth. NICOT. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988. [ Links ]

Hunter, Alastair G. "How Many Gods Had Ruth." SJT 34.5 (1981): 427-36. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0036930600055290. [ Links ]

Hyman, Ronald T. "Questions and Changing Identity in the Book of Ruth." USQR 39.3 (1984): 189-201. [ Links ]

Koosed, Jennifer L. Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and Her Afterlives. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv6sj9vr. [ Links ]

Kugel, James. The Idea of Biblical Poetry: Parallelism and Its History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981. [ Links ]

LaCocque, Andre. Ruth: A Continental Commentary. Translated by K. C. Hanson. CC. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004. [ Links ]

Lau, Peter H. W. Identity and Ethics in the Book of Ruth: A Social Identity Approach. BZAW. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011. [ Links ]

-. Unceasing Kindness: A Biblical Theology of Ruth. NSBT. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2016. [ Links ]

Linafelt, Tod. "Narrative and Poetic Art in the Book of Ruth." Int 64 (2010): 117-29. [ Links ]

Linafelt, Tod, and Timothy K. Beal. Ruth and Esther. BO. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Mangrum, Benjamin. "Bringing 'fullness' to Naomi: Centripetal Nationalism in the Book of Ruth." HBT 33.1 (2011): 62-81. https://doi.org/10.1163/187122011x546804. [ Links ]

Meyers, Carol. "Returning Home: Ruth 1.8 and the Gendering of the Book of Ruth." Pages 85-114 in Feminist Companion to Ruth. Edited by Athalya Brenner. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Michael, Matthew. "The Art of Persuasion and the Book of Ruth: Literary Devices in the Persuasive Speeches of Ruth 1:6-18." HS 56 (2015): 145-62. https://doi.org/10.1353/hbr.2015.0023. [ Links ]

Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. "Returning to the 'Mother's House': A Feminist Look at Orpah." CC 108.13 (1991): 428-30. [ Links ]

Moore, Michael S. "To King or Not to King: A Canonical-Historical Approach to Ruth." BBR 11.1 (2001): 27-41. [ Links ]

Myer, Jacob M. The Linguistic and Literary Form of the Book of Ruth. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1955. [ Links ]

Nielsen, Kirsten. Ruth: A Commentary. OTL. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Noth, Martin. Die israelitischen Personennamen im Rahmen der gemeinsemitischen Namengebung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1928. [ Links ]

Pardee, Dennis. "The Semitic Root Mrr and the Etymology of Ugaritic Mr(r)//Brk." UF 10 (1978): 249-88. [ Links ]

Queen-Sutherland, Kandy. Ruth & Esther. SHBC. Macon: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 2016. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, Rolf. The Covenant Formula: An Exegetical and Theological Investigation. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998. [ Links ]

Rossow, Francis C. "Literary Artistry in the Book of Ruth and Its Theological Significance." ConJ 17.1 (1991): 12-19. [ Links ]

Sasson, Jack M. Ruth: A New Translation with a Philological Commentary and a Formalist-Folklorist Interpretation. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Saxegaard, Kristin Moen. Character Complexity in the Book of Ruth. FAT. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010. [ Links ]

Schipper, Jeremy. Ruth: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. AYB. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016. [ Links ]

-. "The Syntax and Rhetoric of Ruth 1:9a." VT 62.4 (2012): 642-45. [ Links ]

Sharp, Carolyn J. "Feminist Queries for Ruth and Joshua: Complex Characterization, Gapping, and the Possibility of Dissent." SJOT 28 (2014): 229-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09018328.2014.932570. [ Links ]

Smend, Rudolf. Die Bundesformel. ThSt. Zürich: EVZ-Verlag, 1963. [ Links ]

Smith, Mark S. "'Your People Shall Be My People': Family and Covenant in Ruth 1:16-17." CBQ 69.2 (2007): 242-58. [ Links ]

Sternberg, Meir. The Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Thomas, Nancy J. "Weaving the Words: The Book of Ruth as Missiologically Effective Communication." Missiology 30.2 (2002): 155-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/009182960203000202. [ Links ]

Trible, Phyllis. God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1978. [ Links ]

Vuilleumier, René. "Stellung Und Bedeutung Des Buches Ruth Im Alttestamentlichen Kanon." TZ 44.3 (1988): 193-210. [ Links ]

Waard, Jan de, and Eugene A. Nida. A Handbook on the Book of Ruth. Second. UBSHS. New York: United Bible Societies, 1992. [ Links ]

Wardlaw Jr., Terrance R. "Shaddai, Providence, and the Narrative Structure of Ruth." JETS 58.1 (2015): 31-41. [ Links ]

West, Mona. "Ruth." Pages 190-94 in The Queer Bible Commentary. Edited by Deryn Guest, Robert E. Gross, Mona West, and Thomas Bohache. London: SCM Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Submitted: 30/04/2019

Peer-reviewed: 08/10/2019

Accepted: 04/11/2019

Timothy L. Decker, Blue Ridge Institute for Theological Education/IRBS Theological Seminary, E-mail: timldecker@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8372-1705.

1 For this author's literary take on Ruth 1:1-5, see Timothy L. Decker, "Ruth 1:1-5: An Exegetical and Expositional Proposal," Conspectus 9, no. 03 (2010): 33-50.

2 "Foils" as a literary device is here defined as "A character whose qualities emphasise [sic] another's (usually the protagonist's) by providing a sharp contrast." Peter Auger, The Anthem Dictionary of Literary Terms and Theory (London: Anthem Press, 2010), 114.

3 George S. Glanzman, "The Origin and Date of the Book of Ruth," CBQ 21, no. 2 (April 1959): 201-207; Jerry A. Gladson, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Ruth (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012), 71-93.

4 Amelia Devin Freedman, "Naomi's Experience of God and Its Treatment in the Book of Ruth," Proceedings 23 (2003): 29-38.

5 Nancy J. Thomas, "Weaving the Words: The Book of Ruth as Missiologically Effective Communication," Missiology 30, no. 2 (April 2002): 155-169.

6 Peter H. W. Lau, Unceasing Kindness: A Biblical Theology of Ruth, NSBT (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2016). Perhaps not too far from a description of redemptive-historical is Charles P. Baylis, "Naomi in the Book of Ruth in Light of the Mosaic Covenant," BSac 161, no. 644 (October 2004): 413-431.

7 René Vuilleumier, "Stellung und Bedeutung des Buches Ruth im Alttestamentlichen Kanon," TZ 44, no. 3 (1988): 193-210; Michael S. Moore, "To King or Not to King: A Canonical-Historical Approach to Ruth," BBR 11, no. 1 (2001): 2741; Carlos Bovell, "Symmetry, Ruth and Canon," JSOT 28, no. 2 (December 2003): 175-191; J. Andrew Dearman and Sabelyn A. Pussman, "Putting Ruth in Her Place: Some Observations on Canonical Ordering and the History of the Book's Interpretation," HBT 27, no. 1 (June 2005): 59-86; Greg Goswell, "The Order of the Books in the Greek Old Testament," JETS 52 (2009): 460-462.

8 Athalya Brenner, ed., Feminist Companion to Ruth (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993); Carolyn J. Sharp, "Feminist Queries for Ruth and Joshua: Complex Characterization, Gapping, and the Possibility of Dissent," SJOT 28 (2014): 229-252.

9 Irmtraud Fischer, "The Book of Ruth as Exegetical Literature," European Judaism 40, no. 2 (October 2007): 140-149.

10 See Daniel I. Block, Judges, Ruth: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture, NAC (Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 1999), 599-603.

11 Alter described characterization or character development as follows: "Character can be revealed through the report of actions; through appearances, gestures, posture, costume; through one character's comment on another; through direct speech by the character; through inward speech, either summarized or quoted as interior monologue; or through statements by the narrator about the attitudes and intentions of the personages, which may come either as flat assertions or motivated explanations." Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative, Revised and Updated. (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 146.

12 Francis C. Rossow, "Literary Artistry in the Book of Ruth and Its Theological Significance," ConJ 17, no. 1 (January 1991): 15. For the benefits of sociology to help in the literary characterization in the book of Ruth, see Jon L. Berquist, "Role Dedifferentiation in the Book of Ruth," JSOT 18, no. 57 (March 1993): 23-37.

13 For a feminist approach to the same task, see Jennifer L. Koosed, Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and Her Afterlives (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2011).

14 Matthew Michael, "The Art of Persuasion and the Book of Ruth: Literary Devices in the Persuasive Speeches of Ruth 1:6-18," HS 56 (2015): 151-152. See also Carol Meyers, "Returning Home: Ruth 1.8 and the Gendering of the Book of Ruth," in Feminist Companion to Ruth, ed. Athalya Brenner (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), 92-93.

15 Baylis, "Naomi in the Book of Ruth in Light of the Mosaic Covenant," 425-427.

16 Francis Brown, S.R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon, Reprint. (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2005), 997.

17 David J. A. Clines, ed., The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, DCH (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2001), 8: 276.

18 Gladson, Book of Ruth, 161.

19 This is similar to Baylis's explanation for Ruth's "return" in Ruth 1:22 saying, "[T]he use of the term in light of second level knowledge (cf. Deuteronomy 30:1-3) is apparent. Ruth was going to the land that belonged to her God, Yahweh of Israel." "Naomi in the Book of Ruth in Light of the Mosaic Covenant," 427.

20 Judy Fentress-Williams, Ruth, Abingdon OTC (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2012), 46.

21 According to Nielsen, this is "characteristic of the narrative form. By giving such priority to dialogue in the story, the author allows readers to form their own image and opinion of the protagonists." Kirsten Nielsen, Ruth: A Commentary, OTL (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), 47.

22 Jack M. Sasson, Ruth: A New Translation with a Philological Commentary and a Formalist-Folklorist Interpretation (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1989), 23.

23 For example, see Kandy Queen-Sutherland, Ruth & Esther, SHBC (Macon: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 2016), 55. See especially Meyers, "Returning Home: Ruth 1.8 and the Gendering of the Book of Ruth."

24 Arthur E. Cundall and Leon L. Morris, Judges and Ruth, TOTC (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008), 245-247.

25 Peter H. W. Lau, Identity and Ethics in the Book of Ruth: A Social Identity Approach, BZAW (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011), 130; L. Daniel Hawk, Ruth, Apollos OTC (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2015), 57.

26 Block, Judges, Ruth, 633.

27 Danna Nolan Fewell and David M. Gunn, "'A Son Is Born to Naomi': Literary Allusions and Interpretation in the Book of Ruth," JSOT 13, no. 40 (February 1988): 99-108. For a rebuttal to this view, see Peter W. Coxon, "Was Naomi a Scold: A Response to Fewell and Gunn," JSOT 14, no. 45 (October 1989): 25-37. For their response to Coxon, see Danna Nolan Fewell and David M. Gunn, "Is Coxon a Scold? On Responding to the Book of Ruth," JSOT 14, no. 45 (October 1989): 39-43.

28 Considering the way the scene ends in Ruth 1:9b with weeping of sadness rather than relief, this author does not find convincing the argument of Holmstedt or Schipper. They stated that the strange syntax of Ruth 1:9a with the jussive "give" (יִ תֵּ֤ן) having no object is an anacoluthon which led Schipper to see as a rhetorical device to insert the concept of aborting the blessing. Schipper offered the translation, "'May Yhwh give you... [Oh, forget it!] Each of you, go find security with another husband!' This translation adds 'Oh, forget it!' in brackets to emphasize the possible rhetorical impact of the aborted formulaic blessing that began in v. 8b." But if this were a rhetorical strategy, as Schipper argued, then there seems to be less reason for weeping and more cause for relief on the part of Ruth and Orpah. This is something not observed at the end of v. 9. See Robert D. Holmstedt, Ruth: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text, BHHB (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2010), 75; Jeremy Schipper, "The Syntax and Rhetoric of Ruth 1:9a," VT 62, no. 4 (2012): 642-645. Block noted the awkward syntax with Holmstedt but opted to see it perhaps indicating Naomi's emotional state. Daniel I. Block, Ruth: A Discourse Analysis of the Hebrew Bible, ZECOT (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015), 87n28.

29 Michael, "The Art of Persuasion and the Book of Ruth," 153.

30 Thomas, "Weaving the Words," 161.

31 Danna Nolan Fewell, "Space for Moral Agency in the Book of Ruth," JSOT 40, no. 1 (September 2015): 83-84.

32 Nielson agreed saying, "And, just as the redeemer serves as background to Boaz's declaration that he will marry Ruth and produce an heir for Mahlon, so does Orpah function as a contrast to Ruth's declaration that she will stay beside Naomi." Ruth, 48.

33 Ronald T. Hyman, "Questions and Changing Identity in the Book of Ruth," USQR 39, no. 3 (1984): 192.

34 For example, Mona West said of Ruth 1:14, "These words and actions present the closest physical relationship between two women expressed anywhere in the Bible. The Hebrew word that describes Ruth's clinging (davka) to Naomi is the same word used in Genesis 2.24 to describe the relationship of the man to the woman in marriage... Ruth is our Queer ancestress." Mona West, "Ruth," in The Queer Bible Commentary, ed. Deryn Guest et al. (London: SCM Press, 2006), 190.

35 Scott N. Callaham, "But Ruth Clung to Her: Textual Constraints on Ambiguity in Ruth 1:14," TynBul 63, no. 2 (2012): 196. He went on to astutely state, "The syntax of Ruth 1:14 depicts momentary, significant, contrasting actions; Ruth 'clings' as Orpah concurrently leaves. Thus the plain sense of 'clinging' in Ruth 1:14 does not characterize the enduring Ruth-Naomi relationship, but instead constitutes a single action in the developing narrative." This author would only add that the "single action" in v. 14 is the contrastive element Callaham spoke of earlier.

36 Block, Judges, Ruth, 638.

37 Hawk, Ruth, 59.

38 Frederic Bush, Ruth, Esther, WBC (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 73.

39 Sternberg's three reading positions known as reader-elevated, character-elevated, and even-handed are helpful here. Meir Sternberg, The Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 163-172. If one interprets Orpah positively, then the reader is in the even-handed position where "treatment establishes a parity in both the raw information and the modes of processing... Where the intermediate differs from the polar strategies [reader-elevated and character-elevated], then, is in the equal opportunities provided for observation and inference rather than in the use made of them by the observers concerned" (p. 169). However, if seen negatively, the narrator put the reader in the position of character-elevating saying, "Through a piecemeal release of material, it propels the reader from initial ignorance (or at best mystification) to ultimate surprise, usually two-pronged because it springs on us both new facts and, no less inglorious, some character's long-standing awareness of them. It is from this vulnerable position that we first misinterpret and then, on the emergence of the backward-looking inside view, reinterpret" (italics added; p. 165). Given what the author says of Orpah in the next verse, the negative view of Orpah and the character-elevated position seems to fit best.

40 Fentress-Williams, Ruth, 48.

41 Nielsen, Ruth, 48.

42 Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, "Returning to the 'Mother's House': A Feminist Look at Orpah," The Christian Century 108, no. 13 (April 17, 1991): 428-430.

43 Phyllis Trible, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1978), 172.

44 Likely, Orpah did not simply return to general polytheism but to Chemosh the primary god of Moab. Though the plural "gods" is used in v. 15, it is also used of YHWH in v. 16. See Alastair G. Hunter, "How Many Gods Had Ruth," SJT 34, no. 5 (1981): 428.

45 Nielsen claimed, "It is characteristic that the author passes no judgment on Orpah, leaving this to the reader. Sooner or later a reader is bound to react negatively." Ruth, 48.

46 While highly doubtful, Ruth Rabbah 2:9 claimed Ruth and Orpah were the daughters of King Eglon of Moab, thus making them not only sisters but royalty.

47 What makes this expression and use of חֶֶ֫סֶד even more interesting is that Boaz says of her "חֶֶ֫סֶ that it is "better than the first" (NASB). Many commentators take this back to Ruth 2:11 which is an elaboration on the commitments first made in Ruth 1:16ff. See Block, Judges, Ruth, 693; Gladson, Book of Ruth, 264-265. Guyette said of this portion of Ruth, "Ruth's loyalty to Naomi shows how the practices of covenant (berit) and loving-kindness (hesed) are not just for diplomats at the royal court... Hesed is a practice of generosity and good will that goes beyond what is expected or what is customary. Hesed is motivated by love of God and love of neighbour, and seeks the welfare of another person." Frederick Guyette, "The Book of Ruth: Solidarity, Kindness, and Peace," Solidarity 3, no. 1 (November 20, 2013): 34.

48 Tod Linafelt, "Narrative and Poetic Art in the Book of Ruth," Int 64 (2010): 123126. To bear out the purpose behind this odd convention of narrative switching to poetry, Linafelt helpfully said, "[T]he author of the book of Ruth shifts into the poetic mode here precisely in order to give the reader access to the inner lives of Ruth and of Naomi, and to signal to the reader that he or she is doing so. We are encouraged to read the two speeches in conversation with each other, since they are separated by only two verses and are the only two poems in the book" (127).

49 Ibid., 124-125.

50 See James Kugel, The Idea of Biblical Poetry: Parallelism and Its History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981), chap. 1; Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry, Revised and Updated. (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 19ff.

51 Rudolf Smend, Die Bundesformel, ThSt (Zürich: EVZ-Verlag, 1963). A more nuanced and careful study is Rolf Rendtorff, The Covenant Formula: An Exegetical and Theological Investigation (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998).

52 Rendtorff, The Covenant Formula, 13-32; 93-94.

53 Mark S. Smith, "'Your People Shall Be My People': Family and Covenant in Ruth 1:16-17," CBQ 69, no. 2 (April 2007): 242-258.

54 Block put these four Hebrew words at the centre of an ABCB'A' chiastic structure and therefore "climactic." Block, Ruth, 93-94.

55 Edward F. Campbell, Jr., Ruth: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes and Commentary, AB (New York: Doubleday, 1975), 80.

56 Smith, "Family and Covenant in Ruth 1:16-17," 255.

57 Neil Glover, "Your People, My People: An Exploration of Ethnicity in Ruth," JSOT 33, no. 3 (March 2009): 296.

58 Ibid., 300-305.

59 Fewell and Gunn described the effects of Ruth's speech to Naomi as a means for Ruth to say to Naomi, "If you are worried that to continue association with a foreign woman with foreign gods is to invite further disaster, then don't worry, for I can fix that; I'll change people-Your people will be my people!-and I'll change gods as well-Your god will be my god!" Danna Nolan Fewell and David M. Gunn, Compromising Redemption: Relating Characters in the Book of Ruth (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2009), 96.

60 Fewell, "Space for Moral Agency in the Book of Ruth," 84. This author does not find Andrew Davis's argument of a division between Ruth and Naomi based upon the gender discord and grammar convincing. Nevertheless, he well noted the contrastive tension between Ruth and Naomi, and therefore gives credence to his conclusions. Andrew R. Davis, "The Literary Effect of Gender Discord in the Book of Ruth," JBL 132 (2013): 507-508.

61 Linafelt, "Narrative and Poetic Art in the Book of Ruth," 128.

62 There is a negative perception espoused by Fewell and Gunn, Compromising Redemption, 73. Saxegaard sees a more neutral or even a contented Naomi behind this statement. Kristin Moen Saxegaard, Character Complexity in the Book of Ruth, FAT (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 102-103.

63 Robert L. Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, NICOT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 121.

64 André LaCocque, Ruth: A Continental Commentary, trans. K. C. Hanson, CC (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), 54.

65 Jan de Waard and Eugene A. Nida, A Handbook on the Book of Ruth, Second., UBSHS (New York: United Bible Societies, 1992), 19.

66 That the narrator stated Naomi's silence seems an intentional gap. And almost as if he were in a conversation with Meir Sternberg about OT narrative gap-filling, Linafelt asked, "The reader thus contributes greatly to the meaning of the story depending on how he or she fills in these gaps in characterization." Tod Linafelt and Timothy K. Beal, Ruth and Esther, BO (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1999), 17; Sternberg, The Poetics of Biblical Narrative, 186-229.

67 Perhaps this is why major commentaries do not even address the issue if even v. 18 at all! Cf. Campbell, Jr., Ruth, 75; Sasson, Ruth, 31; Jeremy Schipper, Ruth: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AYB (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 101.

68 Trible, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality, 173.

69 Fewell and Gunn, "'A Son Is Born to Naomi,'" 104.

70 Bush, Ruth, Esther, 85.

71 Combining both Naomi's silence felt in Ruth 1:18 as well as the changing of her name in 1:20, Kristin Saxegaard perceptively pointed out that at the conclusion of the book of Ruth, "Naomi's condition remains open. Her voice is muted at the end of the narrative and the reader will never know whether Naomi understands herself as a Naomi again or if she is still a Mara." Saxegaard, Character Complexity in the Book of Ruth, 103. This is in such stark contrast with Ruth who is very clear as to the terms of her commitment as stated in her own words as well as how the town of Bethlehem perceived her in Ch. 4.

72 Timothy L. Decker, "Ruth 1:1-5: An Exegetical and Expositional Proposal," 4041.

73 Take Nielson's comment for example, "She no longer wishes to be called Naomi, i.e., 'my joy' or 'sweetness,' now that her fate is better covered by the name Mara, i.e., 'bitterness.'" Nielsen, Ruth, 51. See also Freedman, "Naomi's Experience of God and Its Treatment in the Book of Ruth," 30; Hawk, Ruth, 52, 62.

74 Many commentators such as Campbell, Jr., Ruth, 52-53 and Gladson, Book of Ruth, 152 explain this concept based on the work of Martin Noth, Die israelitischen Personennamen im Rahmen der gemeinsemitischen Namengebung (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1928), 166.

75 Freedman, "Naomi's Experience of God and Its Treatment in the Book of Ruth," 34.

76 There is a textual variant that includes the הending. BHS only listed "multiple Mss" whereas BHQ surprisingly said nothing. According to Myer, the Kennicott collection "lists 17 MSS as reading מרה." Jacob M. Myer, The Linguistic and Literary Form of the Book of Ruth (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1955), 10. However, this is to be expected in these later medieval Mss wherein the final הis a mater lectionis. See Schipper, Ruth, 106.

77 LaCocque, Ruth, 55. See GKC §80h wherein "א, the Aramaic orthography for ה, chiefly in the later writers." Wilhelm Gesenius, Gesenius'Hebrew Grammar, ed. E. Kautzsch, trans. A. E. Cowley (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006).

78 Campbell, Jr., Ruth, 76.

79 Dennis. Pardee, "The Semitic Root Mrr and the Etymology of Ugaritic Mr(r)//Brk," UF 10 (1978): 249-288.

80 Cundall and Morris, Judges and Ruth, 253.

81 Myer, The Linguistic and Literary Form of the Book of Ruth, 10; Campbell, Jr., Ruth, 76; Bush, Ruth, Esther, 92.

82 This is similar to Hawk's explanation, "Naomi's response to the women brings the issue of identity directly to the surface (vv. 16-17). She separates herself from the women of Bethlehem by refusing the identity they give her ('Sweet') and claiming her own identity (Mara, 'Bitter'). She also separates herself from Yahweh." Hawk, Ruth, 62.

83 Fentress-Williams, Ruth, 53.

84 Sasson, Ruth, 33.

85 Ibid.

86 Clines, The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, 5:474.

87 Frank Moore Cross, "Yahweh and the God of the Patriarchs," HTR 55, no. 4 (October 1962): 244-250.

88 LaCocque, Ruth, 55.

89 Gladson, Book of Ruth, 185. Hawk also noted that chiastic pattern, "Shaddai, Yahweh, Yahweh, Shaddai." However, he failed to note the literary and emotive significance that such a rhetorical device should elicit. Hawk, Ruth, 62.

90 Additionally, Gladson proposed a play on the word "field" (שָדֶה)used in Ruth 1:2 as "fields of Moab" (שְ די־מוֹאֶָ֖ב)which is eerily similar to Shaddai.

91 Terrance R. Wardlaw Jr., "Shaddai, Providence, and the Narrative Structure of Ruth," JETS 58, no. 1 (March 2015): 39-40.

92 LaCocque, Ruth, 56.

93 Although Π157 could have a negative meaning of "afflicted."

94 Block, Ruth, 103.

95 Waard and Nida, A Handbook on the Book of Ruth, 21.

96 Grant and Schipper leave the final phrase of 1:22 for the beginning of ch. 2. Reg Grant, "Literary Structure in the Book of Ruth," BSac 148, no. 592 (October 1991): 433; Schipper, Ruth, 109-111.

97 Block, Ruth, 105.

98 Hubbard said, "The narrator is a consummate literary artist. The beginning and end of the chapter bracket a beautifully ordered whole. It began with famine and departure; it ends with harvest and return." The Book of Ruth, 131.

99 Jan de Waard said of 1:22 that "This final verse of chapter 1 constitutes a summary paragraph. It adds no new information except to introduce 'the barley harvest,' and this serves as a kind of translation to what Ruth is described as doing in chapter 2." A Handbook on the Book of Ruth, 21.

100 Though the second "return" (הַשָׁ֖בָה)is often confused with a participle, the accent in the MT makes this a perfect with the article acting as a relative pronoun according to Campbell, Jr., Ruth, 77-78; Sasson, Ruth, 36.

101 Schipper also noted, "This clause further distinguishes Ruth from Orpah." Schipper, Ruth, 109.

102 Bush, Ruth, Esther, 94.

103 The themes presented here parallel the arguments for a later date argued by Benjamin Mangrum, "Bringing 'fullness' to Naomi: Centripetal Nationalism in the Book of Ruth," HBT 33, no. 1 (2011): 62-81. However, this author is not fully convinced a later date is necessary for the same literary effect such as contrastive characterization. Others hold to a post-Exilic dating with a far more conflicting view of the book of Ruth interpreting it as an "attack" on Deuteronomy. See John Briggs Curtis, "Second Thoughts on the Purpose of the Book of Ruth," Proceedings 16 (1996): 141149.

104 The debate is whether Naomi encouraged Ruth to go out like a virtuous woman seeking out a potential husband and redeemer in Boaz or as a prostitute in order to gain sexual favours from Boaz (see Koosed, Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and Her Afterlives, 89). Similar is the theory of sexual "entrapment" by Fewell and Gunn, Compromising Redemption, 78. However, for a more likely and favourable interpretation maintaining the virtue of all three characters in chapter three, see Block, Judges, Ruth, 679-701.

105 Robert B. Chisholm Jr., From Exegesis to Exposition: A Practical Guide to Using Biblical Hebrew (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1999), 226.