Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.32 n.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n2a19

ARTICLES

Reading Psalm 112 as a "Midrash" on Psalm 1111

Gert T. M. Prinsloo

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Psalms 111 and 112 are "twin" poems displaying similar characteristics such as the superscript הללו יה, an acrostic form, and shared vocabulary. Surprisingly, the shared characteristics are noted, but the poems often interpreted in isolation. Ps 111 is classified as a hymn or a song of thanksgiving and Ps 112 as a wisdom poem. The prominent presence of so-called "wisdom terminology" in Ps 112 plays a major role in its classification, while the presence of similar terminology in Ps 111 is ignored. The present study engages in an intertextual reading of the two poems. They are read as an intentional, artistic literary composition. Following Michael Fishbane's notion of inner-biblical exegesis, I argue that Ps 112 is an intentional "midrash" on Ps 111, and that the pair should be read as a composition in the context of the late Torah-wisdom redaction of the Psalter in general and Book V of the Psalter in particular.

Keywords: Psalm 111, Psalm 112, twin psalms, intertextuality, inner-biblical exegesis, midrash, literary composition, wisdom, Torah wisdom, Psalter Book V, Persian Period.

A INTRODUCTION

There are obvious reasons for regarding Pss 111-112 as "twin" poems.2 They share the exhortation הללו יה as a superscript,3 display shared vocabulary,4 are complete acrostics, and are unique acrostics in the sense that every colon begins with a consecutive letter of the alphabet, and not just every verse line, as is the case in all other acrostic poems in the Hebrew Bible.5 No consensus exists regarding the reason(s) for the two poems' shared formal features. Some propose shared authorship,6 others regard common authorship as a possibility,7 and still others regard Ps 112 as a later composition following the pattern of Ps 111.8Superficially, there seems to be consensus that the two poems should be interpreted in conjunction with and in the light of each other.9

It is thus somewhat surprising that the הללו יה exclamation in 111:1, together with the self-admonition to give wholehearted thanks to Yhwh (111:1a) and a final affirmation that Yhwh's praise stands forever (111:10c) prompt exegetes to classify Ps 111 as a hymn or song of thanksgiving,10 while the presence of the same exclamation in Ps 112:1 is ignored in the genre classification of that poem. Conversely, the presence of so-called wisdom terminology in Ps 112 leads to the classification of the poem as a wisdom text,11while the presence of similar terminology in Ps 111 is ignored in that poem's genre classification.12 If the logic of Gattung classification and the related speculation regarding a specific Sitz-im-Leben is followed to its final consequences, one of three routes is followed.13 The similarities between the poems prompt some to speculate that both belong to the cult and constitute a liturgy in the context of a formal thanksgiving ceremony in the temple.14 The acrostic form prompts others to speculate that, although they contain traditional forms, they are at home in a didactic setting and primarily intended to be read, thus they are detached from the cult.15 Finally, some argue that Ps 111 is intended to be performed at an ancient Israelite cultic festival,16 while Ps 112 belongs to the "learned psalmography" of late post-exilic wisdom circles - often associated with scribal schools, and is per definition non-cultic.17 The current placement of Pss 111 and 112 in the Psalter might be a mere coincidence.18

I maintain that the listing of Pss 111 and 112's shared vocabulary and the notation of their shared formal characteristics are important markers for an intertextual and/or contextual reading of the poems. The exercise as such, however, does not constitute a reading of one poem in light of the other as an intentional literary composition. I propose such a reading in this essay. I will engage in an intratextual analysis of the individual poems, highlight the intertextual similarities and dissimilarities between the poems, and argue that Ps 112 constitutes deliberate and detailed reuse and reapplication of Ps 111, resulting in the pairing of the two poems as an intentional literary construction. Two important issues, namely the relationship of Pss 111-112 to so-called Torah-wisdom in the Psalter and the role of the poems in the editorial profile of Book V cannot be discussed in any detail in the context of this essay.19

My research approach is at home in the field of study classified under the umbrella term "intertextuality."20 I argue for a specific direction of influence from Ps 111 to Ps 112 when they are read as "twins" and propose that the relationship between them is an example of what Michael Fishbane called "inner-biblical exegesis."21 Ps 111 belongs to the stratum of the traditum, while Ps 112 belongs to a very specific stratum of a later exegetical tradition, namely a late post-exilic wisdom redaction of the Psalter playing a crucial role in shaping the final form of the book of Psalms in the Masoretic tradition.22 I cautiously use the term "midrash" to refer to Ps 112's consistent and deliberate reuse and reapplication of motifs in Ps 111. In this context, the term obviously does not refer to "those literary works, some of them quite ancient, which contain scriptural interpretation of the haggadic, more rarely of the halachic, character," in which case Midrash "is outright the title by which such a literary work is known."23 I use the term to signify the process in the Hebrew Bible where "earlier biblical texts are exegetically reused, or 'reactualized', in new contexts."24Fishbane prefers to call this phenomenon of inner-biblical exegesis "aggadic exegesis,"25 and maintains that "each particular instance of aggadic exegesis must be established and justified on its own terms."26

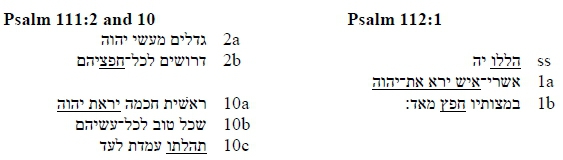

The prompt for my use of the term "midrash" to classify the relationship between Pss 111 and 112 comes from the use of the root דרש in Ps 111:2.27 The poet extols the great "works of Yhwh" (מעשי יהוה). For "all who take delight in them," these great works "are to be contemplated" (דרושים לכל־חפציהם). Such contemplation prompts the poet of Ps 112 to reflect on the blessed existence of the person who "reveres Yhwh" (ירא את־יהוה) and "exceedingly delights in his commandments" (במצותיו חפץ מאד). The root דרש occurs 165 times in the Hebrew Bible,28 usually as a verb in the qal, only eight times in the nip al. It occurs only once more as a qal passive participle, namely in Isa 62:12, where Jerusalem is promised the elevated status of a "sought after" (דרושה), "not to be forsaken city" (עיר לא נעזבה).29 The noun מדרש occurs only twice in the Hebrew Bible (2 Chr 13:22; 24:27) to refer to a written source containing the histories of Judean kings, with the meaning "exposition, interpretation." The verb is most often used in the general sense of "to seek, ask, enquire, search". In contexts where the Torah of Yhwh and analogous terms are involved (cf. Ps 111:7), the verb connotes "worth searching out, worth considering" (cf. Ps 119:45, 94, 155; Ezra 7:10).30 In such cases, the "activity of 'seeking' implies the implementation of what is sought,"31and the act of seeking "can mean properly 'investigate, study, inquire into.'"32 In this sense I consider Ps 112 to be a "midrash" on Ps 111.

B INTRATEXTUAL READINGS OF PSALMS 111 AND 112

Read individually, Pss 111 and 112 are literary constructions developing the notion of divine praise (cf. הללו יה in 111:1; 112:1). Ps 111 focuses on the מעשי יהוה "the works of Yhwh" (v. 2), while Ps 112 focuses on the actions of the איש ירא את־יהוה "the man who fears Yhwh" (v. 1). The poems' shared superscript marks the praise of Yhwh as their primary concern. Commentators ascribe the הללו יה exclamation to a redactional layer of Books IV and V of the Psalter,33 and render the exclamation as virtually meaningless for the interpretation of the poems.34 In Section C, I will argue that the shared superscript is the first cue that Pss 111 and 112 should not only superficially be paired, but that Ps 112 can be read as a midrash on Ps 111. The הללו יה exclamation in Ps 111:1 asks a question: What should Yhwh followers do? The poem answers: They should praise Yhwh for his gracious deeds. The exclamation in Ps 112:1 asks: How should they do it? The poem answers: By mirroring the deeds of Yhwh, Psalms 111 and 112 are complete acrostics represented in the Masoretic tradition in identical fashion, with eight poetic lines containing bicola (vv. 1a-8b, i.e., the א־ע cola), followed by two lines containing tricola (vv. 9a-10c, i.e., the פ־ת cola). In spite of the formal constraints imposed by the acrostic pattern, I will argue below that both poems display a distinct and identical poetic structure,36 a clear development of argument,37 and unity of thought.38 According to Dennis Pardee the colon-acrostic form in Pss 111 and 112 did not override "the parallelism characteristic of ancient West Semitic poetry," but inhibited the "semantic parallelism in regular, inner-colonic, distribution" characteristic of such poetry. It led to a proliferation of "internal semantic parallelism, regular and near grammatical parallelism, and near repetitive parallelism."39 Therefore, Pardee does not detect any macro-structure, "a story line, a plot line" such as may be found in other poems,40 but repetitive parallelism that keeps "the principal themes before the audience."41 This characteristic of Pss 111 and 112 leads to widely diverging proposals regarding their poetic structure.42 I concur with Erich Zenger that these poems with their unique characteristics call for a meticulous analysis of syntactical and stylistic features.43 Following this principle, I demarcate four stanzas in both poems.

The first (vv. 1-3) serves as an introduction, the second (vv. 4-6) and third (vv. 7-9) contain the body of each poem, and the fourth stanza (v. 10) contains a conclusion.44

1 Psalm 111

a Text and translation

b Brief exegetical notes

Superscript: The root הלל appears here for the third time in Book V (cf. Pss 107:32; 109:30), and for the first time as a superscript. Its repetition in Ps 112:1 indicates that praise sets the mood for the interpretation of both poems.45 The exclamation הללו יה appears for the first time in the Psalter in Ps 104:35. According to A. Cohen, the term was "employed by the officiating Levite in the Temple as a signal for the congregation to join in the Service."46 From a cultic perspective, support for the remark can be found in Ps 111:1ab. However, as indicated in note 35 above, the literary, but especially the structuring function of the exclamation deserves further investigation.

1a: The root ידה occurs 67x in the Psalter, 27x in Book V. It is prominent in Book V's opening poem (Ps 107:1, 8, 15, 21, 31) and occurs in Pss 108:4 and 109:30. Psalm 111:1 continues the theme of thanksgiving. In the context of Book V, the suggestion is that the return from exile is a continuation of Yhwh's mighty acts of deliverance that deserves both praise and thanksgiving.47 The לבב "heart" is the seat of the mind and will, of conscious contemplation.48 The whole self is involved in the acts of praise and thanksgiving. In Deuteronomy, the phrase כל־ לבב denotes complete allegiance to Yhwh (Deut 4:29; 6:5; 10:12; 11:13).49 The colon is almost identical to Ps 9:2a.50

1b: The conscious, individual experiences of Yhwh's acts of mercy find collective expression in acts of worship. I regard ועדה ...סוד as a hendiadys.51Some interpreters apply 7Ί0 as referring to a smaller circle of devotees, and עדה to the whole congregation. The two terms occur together elsewhere only in Prov 3:32.52

2a: The מעשי יהוה "is a comprehensive term for Yhwh's saving deeds in and for creation (cf. especially Pss 8:4, 7; 19:2; 145:10) and in history (Deut 11:7; Judg 2:7, 10; Ps 107:22, 24)."53

2b: דרש in the sense of "to study and interpret" (Ezra 7:10; cf. the remarks in Section A). The passive participle functions as a durative,54 and here expresses an obligation, i.e., it has gerundive force.55 Two other passive participles used in the same sense occur in 8a (סמוכים) and 8b (עשוים). In לכל־חפציהם the suffix 3 masc. pl. refers back to the מעשי יהוה in v. 2a. A 3 masc. pl. suffix also occurs in v. 10b (עשיהם), creating an inclusio of human response to the מעשי יהוה.56 לכל suggests that the ישרים (v. 1b) take delight in the contemplation and continuous study of Yhwh's great works.57

3a: הוד־והדר "are epithets of the Lord's royal power, as reflected in the works of creation and redemption."58 For other occurrences of the word pair, cf. Pss 21:5; 45:3-4; 96:6; 104:1; 145:5.

3b: צדקה "has the connotation of doing what is right in the light of a relationship."59 Yhwh's צדקה finds expression in the covenantal relationship with his people explicated in vv. 4-6 and 7-9.

4a: זכר is usually interpreted as a reference to the "remembrance" of Yhwh's "redemptive acts in the cult and liturgical calendar of Israel",60especially the "cultic celebration of the exodus complex of events."61 Cf. in this regard Exod 12:14; Ps 78:1-4, 11-12. However, the poem provides no evidence for a cultic Sitz im Leben. In v. 5b, the root זכר is specifically applied to Yhwh's covenant with his people (cf. also v. 9b). Here זכר is pointedly a "remembrance" of נפלאתיו "his wonders." Yhwh's נפלאות can refer to the plagues aimed against Egypt as acts of liberation (Exod 3:20), or to the passage from Egypt to the Promised Land (Exod 34:10).62 The term occurs 28x in the Psalter and "characterizes Yhwh's action through which, out of love, he rescues from death and sustains life."63 Important in the present context are the occurrences of the term in Ps 119, where "wonders" are associated with contemplation and keeping of Yhwh's תורה (v. 18; cf. 111:2b), פקודים (v. 27; cf. 111:7b), and עדות (v. 129; cf. 111:1b). The very existence of the people as a covenantal community adhering to Yhwh's precepts is a "remembrance" of his wonderful acts of redemption (cf. 111:9a). Significantly, vv. 5a-6b summarise "the 'canonical' history of Israel's origins."64 The very existence of Israel is a "remembrance" of Yhwh's wonders.

4b: The existence of Israel as covenantal community reveals Yhwh's very nature. חנון ורחום "call to mind the formative confession of faith in Exod 34:6-7 of YHWH as one who graciously renews the covenant partnership with Israel."65The phrase repeatedly occurs in the Hebrew Bible, sometimes in the order רחוםוחנון (Pss 86:15; 103:8), often in the order חנוןורחום (Joel 2:13; Jonah 4:2; Pss 111:5; 112:5; 145:8; Neh 9:17, 31; 2 Chr 30:9).

5a: The colon alludes to Yhwh's provision of water and food to his people in the wilderness (Exod 16; Num 11).66 טרף usually denotes the prey of predators (Num 23:24; Isa 5:29; 31:4; Amos 3:4; Nah 2:13-14; 3:1; Pss 104:21; 124:6; Job 4:11; 29:17; 38:39). In some contexts it can simply refer to food (Mal 3:10; Prov 31:15).67 The particular choice of the word is probably dictated by the acrostic structure.68

5b: The colon alludes to Israel's experience at Horeb (cf. Exod 19; 24). The everlasting covenant "is a covenant of grace and promise unconditionally set in place by God,"69 cf. Gen 9:16; 17:7, 13, 19; Exod 31:16. Yhwh "remembers" (יזכר) his covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Exod 2:24) and delivers oppressed slaves from Egypt to give them the land promised to the ancestors, cf. Exod 6:2-8; cf. Ps 105:8-11.70

6a: For כח מעשיו, cf. Exod 34:10; 2 Kgs 17:36. Yhwh's acts of redemption on behalf of his people and the establishment of his everlasting covenant with them is an awe-inspiring (cf. 111:9) proclamation (הגיד) of his power.71

6b: The colon alludes to the conquest of the Promised Land, cf. Deut 4:38; Ps 135:12. The "celebration of Yahweh's power and glory revolves around the gift of the (holy) land, which, of course, is an eminent theme of exilic and postexilic theology."72

7a: For מעשי ידיו, cf. Pss 8:5; 92:5; 138:8. אמת ומשפט is a rare combination (cf. Jer 4:2; Ezek 18:8; Zech 7:9). Yhwh's works are "truth" because he fulfilled the promises of the covenant, and represents "justice" because he is "just" in the administration of his universal government (cf. v. 3 a).73

7b: The colon links מעשי ידיו (v. 7a) and Yhwh's פקודים "precepts." פקודים occurs only in the plural and exclusively in the Psalter. Through parallelism and context it is associated with concepts like מצוה/ות "commandment/s" (Ps 19:9; cf. 111:9b), ברית "covenant" (Ps 103:18; cf. 111:5b, 9b), נפלאות "wonders" (Ps 119:27; cf. 111:4a), עדות "testimonies" (Pss 19:8; 119:168; cf. 111:1b), משפט/ים "rule/s" (Ps 19:10; cf. 111:7a) and defined by concepts such as ישר "upright" (Pss 19:9; 119:128; cf. 111:1b, 8b), צדקה "righteousness" (Ps 119:40; cf. 111:3b), אמת "truth" (Ps 19:10; cf. 111:7b, 8b), אמן "sure" (Pss 19:8; 119:66; cf. 111:7b).74The מעשי יהוה (vv. 2a, 7a) should be interpreted within the horizon of the covenant (111:5b, 9b) and its stipulations (111:7b, 9b).

8a: סמך occurs 11x in the Psalter to denote Yhwh's support of those who follow him. I interpret it in parallelism with נאמנים in 7b. Yhwh's פקודים are continuously supported by him as a source of redemption and life.75

8b: As in v. 2b, I interpret the qal pass. part. עשוים as a gerundive. Cola 8ab represent two sides of the same coin. Yhwh established his פקודים and they are אמת ומשפט. They should be executed באמת וישר "in truth" (cf. v. 7a) and "uprightness" (cf. v. 1b). The פקודים provide the basis for covenant living, hence their performance (v. 8b) should reflect their nature (cf. v. 7ab).76

9a: פדות occurs 4x in the Hebrew Bible (Exod 8:19; Isa 50:2; Pss 111:9; 130:7) and denotes redemption from slavery (cf. פדה "to buy freedom" in Deut 7:8; 9:26; 2 Sam 7:23; Ps 78:42).77 לעמו refers back to v. 6a.

9b: צוה links the notion of commandments (cf. v. 7b) with the concept of η'Ί2 "covenant" (cf. v. 5b). Ps 111:9ab "ties the commandments into the history of salvation presented in vv. 4-6 and makes the gift of the commandments explicitly a 'saving work.'"78 Cf. also Deut 4:13; 28:69; Josh 7:11; 23:16; Judg 2:20; 1 Kgs 11:11; 2 Kgs 17:35; 18:12. The colon recalls v. 5b,79 there with emphasis on the establishment of the covenant as a gracious deed of salvation (a gift), here with emphasis on the divine expectation that the precepts of the covenant will be followed (a task).80

9c: קדוש is a reminder that Yhwh uniquely deals with his people through his acts of gracious compassion. These acts (cf. vv. 2a, 6a, 7a) are awe-inspiring (נורא; cf. v. 5a). The holiness and awesomeness of Yhwh "are intended not to create distance from the congregation but to call the people to acknowledge and explore these acts of salvation in both worship and living."81 Cf. also Ps 99:3, 5, 9; Isa 57:15; Mal 1:14.

10a: Through the repetition of the root ירא the colon links with v. 9c. It expresses a general principle for wise conduct (Prov 1:7; 9:10). The study of Yhwh's works (v. 2b) leads to the conclusion that his precepts (v. 7b) should be done (v. 8b). Such an attitude leads to reverence for Yhwh.82 The phrase יראתיהוה is associated in Pss 19:10; 111:10 and Prov 1:7 with terminology from the Torah semantic domain, and in these cases indicate "content rather than meaning," thus it alludes to the instruction of Yhwh.83

10b: For שכל טוב, cf. 1 Sam 25:3; Prov 3:4; 2 Chr 30:22. Following the ancient versions, the 3 masc. pl. suffix in עשיהם is sometimes emended to 3 fem. sing. and applied to חכמה in v. 10a.84 However, the 3 masc. pl. suffix refers back to כל־פקודיו in v. 7b and creates a compositional frame back to לכל־חפציהם in v. 2b.85 A delight in and execution of the מעשי יהוה thus frame Ps 111.

10c: The colon creates an inclusio with the call to praise in the superscript and recalls the enduring quality of Yhwh's righteousness (v. 3b). There is a direct link between Yhwh's enduring righteousness, "as shown by the reliability of his Torah,"86 and his enduring praise.

c Characteristics, structure and content

As indicated in Table 1, seventeen words occur two times or more in Ps 111.

A close reading of the poem reveals a number of noteworthy characteristics. The repetition of the root הלל in the superscript (v. 1) and the final colon (10c) creates an inclusio and denotes the praise of Yhwh as the poem's primary focus. Apart from the occurrence in the superscript (הללו יה), the nomen dei (יהוה) occurs another four times (1a, 2a, 4b, 10a). No less than thirteen 3 masc. sg. suffixes refer to Yhwh (3a, 3b, 4a, 5a, 5b, 6a, 7a, 7b, 9a, 9b, 9c, 10c). Yhwh is the subject of six 3 masc. sg. verbs (עשה, 4a; נתן, 5a; יזכר, 5b; הגיד, 6a; שלח, 9a; צוה, 9c). Yhwh is the acting subject in the poem.

The acrostic form suggests that Yhwh's praise is an all-encompassing and complete obligation. The notion of completeness is corroborated by the fourfold repetition of כול "all" (1a; 2b; 7b; 10b) and the threefold repetition of both לעד "for ever" (3b; 8a; 10c) and לעולם "for ever" (5b; 8a; 9b).87 The reason for the call to all-encompassing divine praise is מעשי יהוה "the works of Yhwh" (2a), מעשיו "his works" (6a), and מעשי ידיו "the works of his hands" (7a). In v. 3a the parallel expression פעלו "his deed" occurs. The root עשה is repeated another three times (4a; 8b; 10b). The sevenfold repetition of עשה/פעל marks it as the most prominent thematic expression in the poem. All-encompassing and enduring praise is due to Yhwh because he performed great works on behalf of his people.

The tone for the entire poem is set by the 2 masc. pl. imperative (הללו) in the superscript. The intention of thanksgiving by a single devotee, expressed by a 1 sing. cohortative (אודה "I want to give thanks," 1a), has a collective setting (ועדה ... בסוד "in an assembled congregation," 1b). The "assembled congregation," in turn, adhere to specific characteristics. They are ישרים "upright ones" (1b), delight in Yhwh's works (לכל־חפחיהם "to all who delight in them," 2b), and are the revering beneficiaries of Yhwh's benevolent deeds (ליראיו "to those who fear him," 5a).

In light of these characteristics and the exegetical notes above, the structure and content of the poem are summarised in Table 2.

2 Psalm 112

a Text and translation

b Brief exegetical notes

Superscript: The root הלל appears here for the fourth time in Book V (cf. Pss 107:32; 109:30), for the second time as a superscript (cf. 111:1). It continues the mood of praise set in the previous poem.94 The root הלל is, in fact, a continuation of the phrase תהלתו עמדת לעד in Ps 111:10c.95

1a: The אשרי "fortunate is" exclamation, often referred to as a beatitude,96occurs 25x in the Psalter. This "commendation formula creates the perspective of the whole psalm. It is used in wisdom literature to refer to an ideal to emulate; it is an implicit exhortation since it offers congratulations to those who comply."97 It is a synonym for יברך "he will be blessed" (v. 2b) and for the טוב־איש "good is a person" saying in v. 5a. The term suggests "that living the lifestyle the psalm urges, a lifestyle of integrity, brings about wholeness."98 Good fortune "is not a reward that is earned but is the experience of being connected to God."99With the phrase איש ירא את־יהוה, Ps 112 commences where Ps 111 closed.100 The phrase is a synonym for ישר "upright" (vv. 2b; 4a) and צדיק "righteous" (vv. 4b; 6b).

1b: במצותיו alludes to פקודיו in 111:7b and חפץ מאד to חפציהם in 111:2b. The first two cola of Ps 112 thus apply Ps 111 in its entirety to the איש ירא את־יהוה.101

2a: גבור. frequently occurs as a noun, i.e., "hero, champion, warrior" (1 Sam 17:51; Isa 21:17; Ezek 39:20). Less frequently it functions as adjective, i.e., "mighty, numerous" (Gen 10:8; Dan 11:3; Neh 9:32; 1 Chr 1:10). The זרע "descendants" of the איש ירא את־יהוה will be regarded as powerful, influential, and respected.102

2b: The colon recalls 111:1b; cf. also Pss 37:22; 128:4; Prov 22:9. is parallel to זרעו in v. 2a.103

3a: הון occurs 18x in Proverbs and 3x in the Psalter (Pss 44:13; 112:3; 119:14). עשר occurs 15x in Proverbs, 6x in Qohelet, and 5x in the Psalter (Pss 49:7, 17; 52:9; 65:10; 112:3). The close association between the two nouns occurs elsewhere only in Prov 8:18. As indicated in vv. 4a and 7a, the focus is not on "any sort of superficial eudaemonism,"104 but on the blessing of the אישירא את־יהוה precisely because he has שכל טוב (111:10b) and uses the blessings bestowed upon him by Yhwh wisely. Psalm 112 belongs to the category of realistic wisdom. The psalm "admits that the righteous man knows hardship" in spite of the rich blessings and bright future promised to him in v. 2.105

3b: The colon corresponds with 111:3b and is repeated in 112:9b. In Ps 111:3b the focus falls on Yhwh's righteous deeds, here the subject of the righteous behaviour is the איש ירא את־יהוה. Human actions should reflect Yhwh's dealings with his people.106

4a: The interpretation of the colon is controversial. The subject of זרח can be יהוה (i.e., "Yhwh shines in darkness - a light for the upright"); אור (i.e., "light shines in darkness for the upright"); or איש ירא את־יהוה (i.e., "the person who reveres Yhwh shines in darkness - a light for the upright"). The fact that three masc. sg. adjectives in v. 4b allude to the subject of the 3 masc. sg. verb זרח in v. 4a, and that all other 3 masc. sg. suffixes in Ps 112 refer to the איש ירא את־יהוה prompted me to choose the third possibility (cf. Prov 4:18; 13:9).107

4b: The colon recalls 111:4b, with the exception that יהוה is replaced by וצדיק. The expression חנון ורחום (and variants) are elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible exclusively applied to Yhwh.108 Psalm 112:4ab makes a bold claim, namely that the constant application of יראת יהוה (111:10a) enables the איש ירא את־יהוה to reflect Yhwh's nature in his own dealings with others (cf. vv. 5a, 9a). This colon "describes the blessed righteous one as a living image of Yhwh for those around him: he is like a theophany of the Sinai God himself."109 The pertinent addition of וצדיק suggests that the one who complies with the requirements stated in this colon is exactly the one called צדיק in v. 6b, and who is twice assured צדקתו עמדתלעד "his righteousness will stand forever" (vv. 3b; 9b).

5a: טוב sayings occur frequently in wisdom literature (cf. Prov 19:21; 28:6). Here the saying picks up the theme of the blessed existence of the righteous (cf. אשרי in v. 1a; יברך in v. 2b). For a similar pairing of the אשרי exclamation and טוב saying, cf. Prov 14:21-22. חנון picks up the theme of v. 4b, and מולה "free-lending" suggests that social justice should prevail in borrowing practices (Pss 15:5; 37:21, 26; cf. also Deut 28:12; Prov 19:17). The righteous "observes the neediness and helplessness of others and gives them effective aid - by giving them an interest-free loan of produce or money."110

5b: I translate יכלכל (pilp. impf. of כול) with "conduct," cf. Ps 55:23; Prov 18:14. משפט alludes to 111:7a, but again applies a divine attribute to the Godfearing person. Such a person is "just" in his dealings with others.

6a: לא־ימוט suggests that the righteous person will be as unmovable and imperturbable as Mount Zion (Ps 46:6).111 It links with the twice repeated expression עמדת לעד (vv. 3b, 9b); cf. Pss 15:5; 30:7; Prov 10:30; 12:3.

6b: The colon continues the basic thrust of the previous one. A צדיק is assured of a זכר עולם "lasting memory". In the context of the psalm, it links with the notion of a powerful offspring (v. 2a), a blessed generation (v. 2b), and a long-lasting reputation for righteous behaviour (vv. 3b; 9b). The righteous "will live on in the memory of the people - as a paradigm of upright and happy life."112

7a: For שמועה רעה "evil tidings," cf. Prov 15:30; 25:25. לא יירא continues the theme of איש ירא את־יהוה from v. 1a (cf. also v. 8a). Because of his reverence for Yhwh, the righteous person does not need to fear anything or anyone else.113

7b: Cf. Pss 52:8-9; 57:8; 108:2; 78:37. נכון לבו "steadfast is his heart" is parallel to סמוך לבו in v. 8a. לב refers to the total cognitive-emotional existence of the righteous. It is secure due to trust in Yhwh, even if external circumstances suggest uncertainty (v. 7a) and animosity (v. 8b).114

8a: סמוך alludes to the phrase סמוכים לעד לעולם "established are they for ever and ever" in Ps 111:8a. Ps 111 emphasises the enduring validity of Yhwh's פקודים, Ps 112 the quiet confidence of the one who lives according to it. לא יירא repeats his fearless attitude to life (cf. v. 7a).115

8b: עד אשר־יראה continues the motif of quiet confidence expressed in vv. 7-8. יראה is a wordplay on the twice repeated לא יירא (vv. 6a, 7a).116 The righteous needs not fear anything or anyone, therefore he can patiently wait until he witnesses the demise of his adversaries.117 צריו anticipates the references to the רשע "wicked" and his inevitable demise in v. 10 (cf. Pss 54:7; 59:10; 91:8; 118:7).

9a: The colon repeats the notion of social responsibility expressed in v. 5a. פזר נתן, literally "he scattered, he gave," can be interpreted as an instance of hendiadys and translated by "he gave lavishly."118 לאביונים anticipates the theme of Yhwh's special care for the poor in Book V (cf. Pss 113:7; 132:15; 140:13).

9b: The colon is an exact repetition of v. 3b and an allusion to 111:3b. Yhwh's righteousness finds expression in his great redemptive acts on behalf of his people. Similarly, a righteous person illustrates his righteousness by acts of social justice.

9c: קרן תרום literally refers to the powerfully raised horn of a bull. It becomes a metaphor for the honour (בכבוד) accorded to a righteous person (cf. 1 Sam 2:1, 10; Pss 75:11; 89:18, 25; 92:11; 148:14). The person "who gives generously will in turn be richly gifted - with confidence and social recognition, especially from the poor."119

10a: The רשע and his conduct stands in sharp contrast to the one who reveres Yhwh (v. 1a). The wicked also sees (יראה, cf. v. 8b), but what he sees is the blessed existence of the איש ירא את־יהוה, and it evokes in him anger and frustration. כעס occurs in the qal in Ezek 16:42; Qoh 7:9; Neh 3:33; 2 Chr 16:10 to denote extreme fury and frustration.

10b: The phrase יחרק שניו evokes the image of "a snorting predatory beast with bared teeth,"120 cf. Pss 35:16; 37:12; Job 16:9; Lam 2:16. נמס (niph perf. of מסס "to melt") evokes the image of the wicked "melting as it were from his own heat" in impotent rage.121

10c: The final colon indicates that the anger and frustration of the wicked leads to self-destruction (cf. Pss 1:6; 2:12; 37:20; 73:27). תאוה denotes the "craving, desire" of the wicked. The single word evokes images of wicked behaviour sketched in another acrostic (Ps 37) in much more detail.122

c Characteristics, structure and content

As indicated in Table 3, twelve words appear two times or more in Ps 112.

Again, a close reading of the poem reveals a number of interesting characteristics. As was the case in Ps 111, the tone for the entire poem is set by the 2 masc. pl. imperative (הללו) in the superscript. In contrast to Ps 111, however, the focal point is not יהוה and the מעשי יהוה, but איש ירא את־יהוה "the person who reveres Yhwh" (1a). The call to praise Yhwh manifests in the life of ירא יהוה "the one who reveres Yhwh." יהוה appears but twice in the poem (1a; 7b), and only one 3 masc. sg. suffix (1b) refers to the deity.

The איש ירא את־יהוה is twice associated with the ישרים "upright ones" (2b, 4a), twice his צדקה "righteousness" is declared everlasting (3b, 9b), and twice he is explicitly called a צדיק "a righteous person" (4b, 6b). The seven references to the works of Yhwh in Ps 111 are balanced by seven references to the deeds and attitudes of the Yhwh-fearer in Ps 112. Nine 3 masc. sg. suffixes refer to the ירא את־יהוהאיש (2a, 3a, 3b, 5b, 7b, 8a, 8b, 9b, 9c). This person or subjects associated with him are the subjects of thirteen 3 sg. verbal forms (חפץ, 1b; יהיה, 2a; יברך, 2b;זרח, 4a; יכלכל, 5b; לא־ימוט , 6a; יהיה, 6b; לא יירא, 7a; בטח, 7b; לא יירא, 8b; יראה, 8b; פזר, 9a; תרום, 9c). In Ps 112 the focus falls on the person who lives in a relationship with the deity.

The contrast between the opening and closing verses of the poem, particularly between the opening and closing cola, and specifically between the opening and closing words, are of particular importance for the interpretation of the poem. The opening verse declares that the איש ירא את־יהוה is אשרי "fortunate" (vs. 1a). In contrast, the closing verse warns of the impending doom of רשע "the wicked" and warns תאות רשעים תאבד "the desire of wicked people perishes" (v. 10c). Significantly in an acrostic poem, the very first word begins with א, the very last word with ת - the poem covers life from beginning to end.123 The longevity of איש ירא את־יהוה is emphasised by the twofold repetition of both לעד "for ever" (vv. 3b; 9b) and עולם "for ever/everlasting" (vv. 6a; 6b).

In the light of these characteristics and the exegetical notes above, the structure and content of the poem are summarised in Table 4.

C READING PSALM 112 INTERTEXTUALLY AS A "MIDRASH" ON PSALM 111

According to walther Zimmerli, noteworthy similarities between two consecutive poems in the Psalter signals the need for careful consideration on the nature of the relationship.126 With regard to Pss 111 and 112, Zimmerli maintains that "eine deutliche Komplementarität der Aussagen" can be recognised.127 The similarities between Pss 111 and 112 are obvious, numerous, and suggest a close relationship between the two consecutive poems. I will argue below that it is not only the similarities between the poems that are important, but also the sequence. Ps 112 deliberately follows Ps 111. The most obvious resemblance, the shared הללו יה exclamation as superscript (111:1; 112:1) and the fact that both are complete acrostics consisting of twenty-two cola, each colon commencing with a word beginning with the next letter of the Hebrew alphabet, has already been noted. It is important to recognise that the two poems are unique acrostics. They are the only colon-alphabetic acrostics in the Hebrew Bible. Other acrostics are verse line-alphabetic or strophic-alphabetic.128 The acrostic technique "is recognised primarily as a graphic rather than an acoustic phenomenon, it presumes a culture of writing and reading and therefore probably arose and was developed in the scribal and wisdom schools."129

This feature causes me to regard form-critical classifications assigning different functions in different life situations to the two poems with scepticism. The end result of this approach is that the two poems are interpreted in isolation. I concur with Markus Saur when he states that poems like Pss 111-112

"... are texts originating in the education sector, with a distinct didactical orientation but also with the aim of expressing something comprehensive, extending from the beginning to the end, from s to n. It does not come as a surprise then, that in these texts it is often the Torah that is at the heart and centre - the orientation towards the Torah is among the most distinguished educational subject matters in ancient Judah."130

I am equally sceptical about approaches that ignore the הללו יה superscript in the interpretation of the poems. The superscript should be taken seriously. Michael D. Goulder quite rightly argues that "Psalm 111 is more directly a praise of God; 112 a reflection on the blessings attending his faithful service."131However, "the glorification of the upright in Psalm 112 is merely an extension of the praise of Yahweh in 111... so 112 is a kind of indirect praise of Yahweh, and is not unsuitably prefaced with הללו יה."132 The הללו יה exclamation in Ps 112:1 is not a mere repetition of the one in Ps 111. It also comments upon the closing colon of that poem (תהלתו עמדת לעד) through repetition of the root הלל. The life of the איש ירא את־יהוה (112:1a), whose righteousness endures forever (צדקתו עמדת לעד, 112:3b, 9b), becomes an everlasting reflection of divine praise - and הללו יה in Ps 112:1 becomes a midrash on the call to divine praise in the previous poem.

Both poems have the same function in their editorial position in Book V of the Psalter.133 Their praising voices, linking divine grace (Ps 111) and human response (Ps 112), join the series of songs of praise known as the "Egyptian Hallel" (Pss 113-118) and anticipate the call to praise in Pss 135-136 and 146150. The individual voice of thanksgiving in Ps 111:1a joins similar voices in Pss 108:3 and 109:30 in response to the repeated call to thanksgiving in Ps 107:1, 8, 15, 21, and 31. Psalms 111-112 praise 135

Apart from an identical superscript and the acrostic form, Pss 111 and 112 share no less than seventeen common vocabulary terms (cf. Table 5).

The poems share an identical colon at the identical place in the poem: the waw line וצדקתו עמדת לעד in 111:3b and 112:3b. In 112:9b (the tsade line) the same colon (minus the waw) is repeated, while 111:10c (the taw line) contains the very similar line תהלתו עמדת לעד. The hêt line in both poems are almost identical: חנון ורחום יהוה in 111:4b and חנון ורחם וצדיק in 112:4b. Apart from these similarities, the two poems share the following lemmata: יהוה in 111:1a, 2a, 10a and in 112:1a, 7b; לבב in 111:1a and לב in 112:7b, 8a; ישר in 111:1b, 8b and 112:2b, 4a; חפץ in 111:2b and 112:1b; זכר in 111:4a, 5b and 112:6b; ירא in 111:5a, 9c, 10a and 112:1a, 7a, 8a; עד in 111:3b, 8a, 10c and 112:3b, 9b; עולם in 111:5b, 8a, 9b and 112:6a, 6b; משפט in 111:7a and 112:5b; סמך in 111:8a and 112:8a. Finally, both the beginning of Ps 111 (v. 2ab) as well as its end (v. 10abc) are hinted at in the opening verse of Ps 112 - an often-overlooked feature of the two poems' juxtaposition: 136

In this way, Ps 112 encapsulates everything that is said about the מעשייהוה in Ps 111 and becomes a continuation of its predecessor's praise of Yhwh. Psalm 112 becomes a midrash on Ps 111 - a clear and comprehensive illustration of "inner-biblical exegesis".137

As obvious as these similarities are, the clear difference in the focus of the two poems should also be acknowledged. without doubt the key term in Ps 111 is עשה, occurring no less than six times (2a, 4a, 6a, 7a, 8b, 10b). Three times the term occurs as a plural noun, referring to the great salvation acts of Yhwh in the history of his people (2a, 6a, 7a). Significantly, the noun עם "people" occurs twice, both times with a 3 masc. sg. suffix referring to Yhwh (6a, 9a). The term ברית. "covenant" also occurs twice (cf. 5b, 9b), each time with a 3 masc. sg. suffix referring to Yhwh. The focus of Ps 111 is clear: it is concerned with Yhwh and the righteous deeds (cf. 3a) he performed on behalf of his covenant people. words from this broad semantic domain are conspicuously absent from Ps 112. In this poem, the focus is on the recipient(s) of the Yhwh's acts of salvation, the איש ירא את־יהוה "person who fears Yhwh." Such a person needs not to be afraid (לא יירא in 7a and 8a) of bad rumours (7a) or to be fainthearted (8a). He belongs to the ישרים "upright ones" (2b, 4a) and he is צדיק "righteous" (4b, 6b). The focus falls upon such a person's rewards (1ab, 2ab, 3ab, 4a, 6ab, 8a, 9c) and responsibilities of generosity (5a, 9a) and trustworthiness (5b). Ps 111 is concerned with "theology" and Ps 112 with "anthropology."138

Throughout both poems it is clear that Ps 112 deliberately alludes to the corresponding verse in Ps 111, but reapplies and reinterprets what is true of the divine sphere in Ps 111 to the human sphere in Ps 112.139 Ps 112 is a midrash on Ps 111. In Ps 111:2a the works of Yhwh are called "great" (גדלים). In Ps 112:2a the offspring of the Yhwh-fearer becomes "mighty" (גבור) upon the earth. Yhwh's greatness is reflected in the blessing of descendants enabling the Yhwh-fearer to become mighty. דרושים in Ps 111:2b sounds very similar to דור ישרים in 112:2b. The suggestion is that those who have a delight in studying the works of Yhwh turn out to be a generation of upright ones. The work of Yhwh (פעלו) is called "glorious and majestic" (הוד־והדר) in Ps 111:3a, and correspondingly, of the Yhwh to the Yhwh-fearer.140

Of Yhwh it is said in Ps 111:4b that he is "gracious and compassionate" (חנון ורחום) as he illustrates by his actions, and in Ps 112:4b it is the Yhwh-fearer who is "gracious, compassionate, and righteous" (חנון ורחום וצדיק) as is illustrated by his actions. The Yhwh-fearer becomes a mirror image of his deity. In Ps 111:5a Yhwh gives (נתן) food to those who fear him, and in Ps 112:5a it is the Yhwh-fearer who graciously provides (חנון ומולה) without expecting compensation. Of Yhwh's precepts it is said in Ps 111:7b that they are "trustworthy" (נאמנים), and of the Yhwh-fearer it is said in 112:7b that his heart is "steadfast" (נכון) because he trusts in Yhwh. The Yhwh-fearer becomes as dependable as his deity. In Ps 111:8a Yhwh's precepts are "established" (סמוכים) for ever and ever, and in 112:8a it is the heart of the Yhwh-fearer that is "secure" (סמוך), therefore he does not fear. The one who follows Yhwh's precepts becomes as secure as they are. In Ps 111:9a it is Yhwh who sends (שלח) redemption (פדות) to his people (לעמו), and in 112:9a it is the Yhwh-fearer who freely provides (פזר נתן) to the needy (לאביונים). The Yhwh-fearer becomes an imitator of his deity, and divine attributes are reinterpreted and reapplied to the human sphere. In Ps 111:9c Yhwh's name (שמו) is called "holy and awe-inspiring" (קדוש ונורא), and in 112:9c the horn (קרנו) of the Yhwh-fearer is lifted up (תרום) in honour (בכבוד). Homage is due to Yhwh, and honour is bestowed upon his followers.

The contrast between the conclusions of both poems is stark. In Ps 111:10 the main actors are all who do the precepts of Yhwh (לכל־עשיהם). They are wise (חכמה) because they display reverence for Yhwh (יראת יהוה). Their behaviour has perpetual value (לעד) because it amounts to praise of Yhwh (תהלתו). In Ps 112:10, on the other hand, the wicked (רשע) can only look on in utter frustration ( יראהוכעס), gnash his teeth and waste away (שניו יחרק ונמס), because "the desire of the wicked will perish" (תאות רשעים תאבד). Read in conjunction, the two poems imply that those "who align themselves with God's purposes - in short, those who fear God - are truly wise (Ps 111:10) and genuinely happy (Ps 112:1)."141

My intratextual analyses of the two poems above, as well as my intertextual reading of the two poems as an example of inner-biblical exegesis, and specifically of Ps 112 as a midrash on Ps 111, convince me that Zenger is correct when he says:

"Since Psalm 112 is less artistically shaped than Psalm 111 and adopts a more conventional concept of the Torah (cf. Psalm 1), we may suppose that Psalm 111 is the older text and was closely followed in the shaping of its "twin," Psalm 112 .. ,"142

The investigation I conducted here leaves me with two suspicions, or -more scientifically formulated - themes for future research. First, I suspect Ps 112 was deliberately composed as Ps 111's twin and the pair was intentionally placed at their specific location in Book V by the group(s) of wisdom editors in the late Persian or early Hellenistic periods who also played a role in the composition of other acrostics and/or Torah-wisdom poems and in the shaping of the Psalter. Significant intertextual links exist between this pair and Pss 1; 19; 25; 34; 37; 119.143 Ps 111 also has significant links with the closing verses of Ps 107, the first psalm of Book V, and Ps 145, the last psalm of Book V.144 The implications of this phenomenon for the composition of Books I and V, and the relative paucity of the phenomenon in Books II-IV, still need more consideration.145 Second, I suspect the principles operative in the pairing of Pss 111 and 112 are also at work in two more twins in Books IV and V, namely Pss 105-106 and 135-136. These are both so-called "historical" twins. The placing of these twins and their function in the profiles of Books IV and V need careful consideration.

D CONCLUSION

My intra- and intertextual investigations of Pss 111 and 112 lead me to four conclusions. First, I question form-critical classifications of the two poems implying that they originated in different life-settings. Both poems have a didactic nature and belong to the Torah-wisdom group of psalms. Second, the identical superscript, acrostic form, and shared vocabulary indicate that Pss 111112 constitute a deliberate, artistic literary composition. They are indeed twins, albeit not identical twins, as the focus in Ps 111 falls on "theology" and in Ps 112 on "anthropology".146 Third, an intertextual reading reveals that Ps 112 represents a deliberate and detailed reinterpretation and reapplication of motifs in Ps 111. What is said about Yhwh in Ps 111 must find concrete expression in the lives of his followers. In that sense Ps 112 is an excellent representative of inner-biblical exegesis, hence I call Ps 112 a midrash on Ps 111. Finally, Pss 111-112 find their place as a pair in the literary profile of Book V of the Psalter. The implications of their placement therefore need further close investigation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Leslie C. Psalms 101-50, revised. Word Biblical Commentary 21. Nashville, TN: Nelson, 2002. [ Links ]

Auffret, Pierre. "Essai sur la structure littéraire de Psaumes CXI et CXII." Vetus Testamentum 30 (1980): 257-279. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853380x00191. [ Links ]

Auffret, Pierre. "Grandes sont les cevres de YHWH: Étude structurelle du Psaume 111." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 56 (1997): 183-196. https://doi.org/10.1086/468552. [ Links ]

Auffret, Pierre. "En mémoire éternelle sera le juste: Étude structurelle du Psaume CXII." Vetus Testamentum 48 (1998): 2-14. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568533982721992. [ Links ]

Baethgen, Friedrich. Die Psalmen. Handkommentar zum Alten Testament II/2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1904. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil J. "The Measurement of Meaning - An Exercise in Field Semantics." Journal for Semitics 1 (1989): 3-22. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil J. "'Wealth and Riches Are in His House' (Ps 112:3): Acrostic Wisdom Psalms and the Development of Antimaterialism. " Pages 105-128 in The Shape and Shaping of the Book of Psalms: The Current State of Scholarship. Edited by Nancy deClaissé-Walford. Ancient Israel and Its Literature 20. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2016/v29n1a5. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil J. "True Happiness in the Presence of Yhwh: The Literary and Theological Context for Understanding Psalm 16." Old Testament Essays 29 (2016): 61-84. [ Links ]

Brettler, Marc Zvi. "The Riddle of Psalm 111." Pages 62-73 in Scriptural Exegesis: The Shapes of Culture and the Religious Imagination. Essays in Honour of Michael Fishbane. Edited by Deborah A. Green and Laura S. Lieber. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199206575.003.0005. [ Links ]

Brettler, Marc Zvi. "A Jewish Approach to Psalm 111?" Pages 141-159 in Jewish and Christian Approaches to the Psalms: Conflict and Convergence. Edited by Susan Gillingham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles A. and Emily G. Briggs, The Book of Psalms, Vol. 2. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1969. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter and William H. Bellinger Jr. Psalms. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014. [ Links ]

Carr, David M. "The Many Uses of Intertextuality in Biblical Studies: Actual and Potential." Pages 505-535 in Congress Volume Helsinki 2010. Edited by Marti Nissinen. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 148. Leiden: Brill, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004221130024. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. The Psalms. Soncino Books of the Bible 1. Hindhead, Surrey: Soncino, 1945. [ Links ]

Crüsemann, Frank. Studien zur Formgeschichte von Hymnus und Danklied in Israel. wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament 32. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1969. [ Links ]

Dahood, Mitchell. Psalms III: 101-150. Anchor Bible 17a. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, Franz. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms, Volume 3. Translated by Francis Bolton. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973. [ Links ]

Duhm, Bernard. Die Psalmen. Kurzer Hand-Kommentar zum Alten Testament 14. Freiburg: Mohr, 1899. [ Links ]

Dunn, Steven. Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures. DPhil Thesis. Milwaukee, wI: Marquette University, 2009. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Forti, Tova. "Gattung and Sitz im Leben: Methodological Vagueness in Defining wisdom Psalms." Pages 205-220 in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Wisdom Studies. Edited by Mark R. Sneed. Ancient Israel and Its Literature 23. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt173zmjp.13. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations. Forms of Old Testament Literature 15. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Goulder, Michael D. The Psalms of the Return (Book V, Psalms 107-150): Studies in the Psalter, IV. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 258. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1998. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann. Die Psalmen. 6th ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar and Erich Zenger. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101150. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2011. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalms 60-150. A Commentary. Translated by Hilton C. Oswald. Continental Commentaries. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 1989. [ Links ]

Kuntz, J. Kenneth. "The Retribution Motif in Psalmodic Wisdom. " Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 89 (1977): 223-233. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1977.89.2.223. [ Links ]

Kuntz, J. Kenneth. "Wisdom Psalms and the Shaping of the Hebrew Psalter." Pages 144-160 in For a Later Generation: The Transformation of Tradition in Israel, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity. Edited by Randal A. Argall, Beverly A. Bow, and Rodney A. werline. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity, 2000. [ Links ]

Mays, James Luther. "The Place of the Torah-Psalms in the Psalter." Journal of Biblical Literature 106 (1987): 3-12. https://doi.org/10.2307/3260550. [ Links ]

McCann, J. Clinton, Jr. "The Book of Psalms." Pages 641-1279 in The New Interpreters Bible, Vol. IV. Edited by Leander E. Keck. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996. [ Links ]

Meek, Russell L. "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology." Biblica 95 (2014): 280-291. [ Links ]

Miller, Geoffrey D. "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research." Currents in Biblical Research 9 (2011): 283-309. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, Sigmund. The Psalms in Israel's Worship, Volume 2. Translated by Dafydd R. Ap-Thomas. Oxford: Blackwell, 1967. [ Links ]

Neusner, Jacob. What is Midrash? Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2014. [ Links ]

Pardee, Dennis. "Acrostics and Parallelism: The Parallelistic Structure of Psalm 111." Maarav 8 (1992): 117-138. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T.M. "Unit Delimitation in the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113-118)." Pages 232-251 in Unit Delimitation in Biblical Hebrew and Northwest Semitic Literature. Edited by Marjo C. A. Korpel and Josef M. Oesch. Pericope 4. Assen: Van Gorcum, 2003. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T.M. "Seôl - Yerüsãlayim - Sãmayim: Spatial Orientation in the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113-118)." Old Testament Essays 19 (2006): 739-760. [ Links ]

Saur, Markus. "Where Can Wisdom be found? New Perspectives on the Wisdom Psalms." Pages 181-204 in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Wisdom Studies. Edited by Mark R. Sneed. Ancient Israel and Its Literature 23. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt173zmjp.12. [ Links ]

Schaefer, Conrad. Psalms. Berit Olam: Studies in Hebrew Narrative & Poetry. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 2001. [ Links ]

Schildenberger, Johannes. "Das Psalmenpaar 111 und 112." Erbe und Auftrag 56 (1980): 203-207. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Hans. Die Psalmen. Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15. Tübingen: Mohr, 1934. [ Links ]

Scoralick, Ruth. "Psalm 111: Bauplan und Gedankengang." Biblica 78 (1997): 190-205. [ Links ]

Seybold, Klaus. Die Psalmen. Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15. Tübingen: Mohr, 1996. [ Links ]

Sneed, Mark R. (ed.). Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Wisdom Studies. Ancient Israel and Its Literature 23. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt173zmjp. [ Links ]

Strack, Hermann L. Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. New York, NY: Atheneum, 1980. [ Links ]

Terrien, Samuel. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. Eerdmans Critical Commentaries. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Tull, Patricia. "Intertextuality and the Hebrew Scriptures." Currents in Research: Biblical Studies 8 (2000): 59-90. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1. Oudtestamentische Studien 63. Leiden: Brill, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004262799. [ Links ]

Van der Ploeg, Johannes P. M. Psalmen Deel II: Psalm 76 T/M 150. Boeken van het Oude Testament. Roermond: Romen, 1974. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem A. Psalms. The Expositor's Bible Commentary 5. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991. [ Links ]

Van Leeuwen, Raymond C. "Form Criticism, Wisdom, and Psalms 111-112." Pages 65-84 in The Changing Face of Form Criticism for the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Marvin A. Sweeney and Ehud Ben Zvi. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Wagner, Siegfried. "#TJ dãrash; #i7a midrash" Pages 293-307 in vol. 3 of Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Edited by G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren. Translated by John T. Willis et al. 8 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974-2006. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. "Zu Kolometrie und strophischer Struktur von Psalm 111 - mit einem Seitenblick auf Psalm 112." Biblische Notizen 118 (2003): 62-67. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2003. [ Links ]

Weiser, Artur. The Psalms. Translated by Herbert Hartwell. Old Testament Library. London: SCM, 1979. [ Links ]

Weeks, Stuart. "Wisdom Psalms." Pages 292-307 in Temple and Worship in Biblical Israel: Proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar. Edited by John Day. London: T&T Clark, 2007. [ Links ]

Zakovitch, Yair. "The Interpretive Significance of the Sequence of Psalms 111112.113-118.119." Pages 215-227 in The Composition of the Book of Psalms. Edited by Erich Zenger. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 238. Leuven: Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich. "The Composition and Theology of the Fifth Book of Psalms, Psalms 107-145." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 80 (1998): 77-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908929802308005. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich. "Dimensionen der Tora-Weisheit in der Psalmenkomposition Ps 111112." Pages 37-58 in Die Weisheit - Ursprünge und Rezeption. Festschrift für Karl Löning zum 65. Geburtstag. Edited by Martin Fassnacht, Andreas Leinhäupl-Wilke, and Stefan Lücking. Neutestamentliche Abhandlungen 44. Münster: Aschendorff, 2003. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich. "Geld als Lebensmittel? Über die Wertung des Reichtums im Psalter (Psalmen 15.49.112)." Jahrbuch für Biblische Theologie 21 (2006): 73-96. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, Walther. "Zwillingspsalmen." Pages 105-113 in Wort, Lied und Gottesspruch: II. Beiträge zu Psalmen und Propheten. Festschrift für Joseph Ziegler. Edited by Josef Schreiner. Forschung zur Bibel 2. Würzburg: Echter, 1972. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 2019/03/04

Peer reviewed: 2019/05/17

Accepted: 2019/07/19

1 I dedicate this study to Phil Botha. We were both appointed as full-time academics in the early 1980s in the (then) Department of Semitic Languages at the University of Pretoria. We have been colleagues and friends ever since. To me, Phil exemplifies both the wisdom aphorism of Ps 111:10 and the wisdom macarism of Ps 112:1. He is a wise man who inspired many through his erudition and by his dedication. Phil's research in the Psalter focused on the influence of Torah-wisdom on the collection of poems. I trust this intertextual reading of the poetic twins, Pss 111-112, will make a small contribution in the field of Phil's important field of research specialisation.

2 Walther Zimmerli, "Zwillingspsalmen," in Wort, Lied und Gottesspruch: II. Beiträge zu Psalmen und Propheten. Festschriftfür Joseph Ziegler (ed. Josef Schreiner; FzB 2; Würzburg: Echter, 1972), 105-113; Johannes Schildenberger, "Das Psalmenpaar 111 und 112," EuA 56 (1980): 203-207.

3 The exclamation falls outside the acrostic pattern commencing with a word beginning with א (אודה in 111:1; אשרי־איש in 112:1) as noted by many commentators; cf. Bernard Duhm, Die Psalmen (KHAT 14; Tübingen: Mohr, 1899), 256.

4 Cf. Section C below.

5 Schildenberger, "Das Psalmenpaar 111 und 112," 203.

6 Hans Schmidt, Die Psalmen (HAT I/15; Tübingen: Mohr, 1934), 206; Charles A. Briggs and Emily G. Briggs, The Book of Psalms, Vol. 2 (ICC; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1969), 385; Mitchell Dahood, Psalms III: 101-150 (AB 17a; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), 122; Artur Weiser, The Psalms (trans. Herbert Hartwell; OTL;London: SCM, 1979), 703.

7 Duhm, Die Psalmen, 258; Hermann Gunkel, Die Psalmen (6 ed.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986), 490; Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 60-150. A Commentary (trans. Hilton C. Oswald; CC; Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 1989), 362; Klaus Seybold, Die Psalmen (HAT I/15; Tübingen: Mohr, 1996), 440.

8 Friedrich Baethgen, Die Psalmen (HKAT II/2; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1904), 340; Leslie C. Allen, Psalms 101-50, revised (WBC 21; Nashville, TN: Nelson, 2002), 128; Samuel Terrien, The Psalms. Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary (ECC; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 761.

9 Willem A. VanGemeren, Psalms (EBC 5; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991), 700 indicates that at the very least the two poems "originated from within the same general approach to piety."

10 Gunkel, Psalmen, 488 classifies the poem as a hymn. Schmidt, Psalmen, 205 opts for a song of thanksgiving. According to Allen, Psalms 101-50, 121 the combination of the initial הללו יה exclamation and the presence of the root ידה in v. 1a indicates that "thanksgiving elements are used in the service of a solo hymn".

11 Gunkel, Psalmen, 490. Allen, Psalms 101-50, 128 regards Ps 112 as a wisdom psalm and classifies it "as a specimen of Torah-centred piety, like Ps 119, and in this and other respects it resembles Ps 1".

12 Raymond C. van Leeuwen, "Form Criticism, Wisdom, and Psalms 111-112," in The Changing Face of Form Criticism for the Twenty-First Century (ed. Marvin A. Sweeney and Ehud Ben Zvi; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 65-84 identified it as a form-critical problem. The two poems "do not share the same genre, even though they share the same alphabetic acrostic structure, vocabulary, theology, and much of their 'form' or individuality is composed of identical elements."

13 Van Leeuwen, "Form Criticism," 73 warns against the danger of "a vicious circle of deducing life settings from literary evidence and then interpreting the literary evidence in terms of the hypothetical Sitz." Following this "logic," Pss 111 and 112 "should not stem from the same persons, social (institutional) setting, or conceptual world. And yet they do" (80).

14 Schmidt, Psalmen, 206 speculates that during a תודה ceremony in the temple, Ps 111 represents a song of thanksgiving by someone who experienced salvation from a dire situation, Ps 112 the greeting of the person by a priest during the ceremony. Schildenberger, "Das Psalmenpaar 111 und 112," 207 assigns the poems to a renewal of the covenant festival every seven years during the Feast of Booths (Deut 31:10-13).

15 Frank Crüsemann, Studien zur Formgeschichte von Hymnus und Danklied in Israel (WMANT 32; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1969), 296-298.

16 Weiser, Psalms, 699 maintains that Ps 111 might have been intended for "the Feast of the Passover as the occasion when the tradition of the deliverance from Egypt ... was particularly commemorated." However, the most likely Sitz im Leben is "the autumn Covenant Festival at which the renewal of the Covenant was celebrated within the framework of the realization of salvation" (700). Dahood, Psalms III, 123 opts for the Passover as the poem's Sitz im Leben, as does Conrad Schaefer, Psalms (BO; Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 2001), 276.

17 Sigmund Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel's Worship, Volume 2 (trans. Dafydd R. Ap-Thomas; Oxford: Blackwell, 1967), 111-114.

18 Marc Zvi Brettler, "The Riddle of Psalm 111," in Scriptural Exegesis: The Shapes of Culture and the Religious Imagination. Essays in Honour of Michael Fishbane (ed. Deborah A. Green and Laura S. Lieber; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 6273; idem, "A Jewish Approach to Psalm 111?" in Jewish and Christian Approaches to the Psalms: Conflict and Convergence (ed. Susan Gillingham; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 141-159. Ps 112 is "an inferior imitation of Ps 111." Ps 111 "should be read as an independent composition; and it should not be understood, like Ps 112, as a wisdom psalm" (Brettler, "A Jewish Approach to Psalm 111?" 141).

19 Phil J. Botha, "True Happiness in the Presence of Yhwh: The Literary and Theological Context for Understanding Psalm 16," OTE 29 (2016): 61-84 defines Torah-wisdom psalms as "psalms which cast Yhwh (or the psalmist) in the role assigned to a wisdom teacher in Proverbs, so that Yhwh is portrayed as the one who ultimately gives guidance on the way of life through his Torah. A variety of traditional Gattungen were employed and sometimes mixed in composing these psalms. Many of them are acrostics and the contrast between righteous people and the wicked, as well as the portrayal of life as a journey, are often found in them. Psalms 1, 16, 19, 23, 25, 32, 33, 34, 37, 49, 73, 111-112, 119 and some others can be included under this heading" (63 n. 11). Botha ascribes these psalms to the same group of people and date their literary activity in the context of the late Persian or early Hellenistic period (82). James Luther Mays, "The Place of the Torah-Psalms in the Psalter," JBL 106 (1987): 3-12 includes Pss 18; 78; 89; 93; 94; 99; 103; 105; 147; 148 in the list (8 n. 12). These poems "all belong to the last stratum of the collection or have been developed by torah interests" (8).

20 It is not possible to review the debate regarding the appropriateness of the umbrella term as it is applied in Hebrew Bible studies. For a critical discussion of the application of various intertextual approaches, cf. Patricia Tull, "Intertextuality and the Hebrew Scriptures," CR:BS 8 (2000): 59-90; Geoffrey D. Miller, "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research," CBR 9 (2011): 283-309. David M. Carr, "The Many Uses of Intertextuality in Biblical Studies: Actual and Potential," in Congress Volume Helsinki 2010 (ed. M. Nissinen; VTSup 148; Leiden: Brill, 2012), 505-535 (522) regards "intertextuality" as an inappropriate term when specific relations between a given text and earlier texts are involved. He would then rather use the term "influence" than "intertextuality." Similarly, Russell L. Meek, "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology," Bib. 95 (2014): 280-291 (291) argues that "intertextuality" as umbrella term for investigations into literary relationships between texts should be avoided "when attempting to demonstrate - or presupposing - an intentional, historical relationship between texts."

21 Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), 10-13. Fishbane convincingly argues that the "most obvious issue from the viewpoint of traditum and traditio is that the Hebrew Bible is a composite source, so that discerning the traces of exegesis within this Scripture is not a matter of separating biblical (the traditum) from the post-biblical (the exegetical traditio) materials but of discerning its own strata" (10).

22 Spatial constraints do not allow for a discussion of the contested topic of wisdom psalms, wisdom influence in the Psalter, or a wisdom redaction of the Psalter; cf. in this regard Stuart Weeks, "Wisdom Psalms," in Temple and Worship in Biblical Israel: Proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar (ed. John Day; London: T&T Clark, 2007), 292-307; Mark R. Sneed (ed.), Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Wisdom Studies (AIL 23; Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015). From this publication, cf. especially Markus Saur, "Where can Wisdom be found? New Perspectives on the Wisdom Psalms," 181-204, and Tova Forti, "Gattung and Sitz im Leben: Methodological Vagueness in Defining Wisdom Psalms," 205-220. According to Steven Dunn, Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures (DPhil Thesis; Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University, 2009), "the experience of Exile and displacement, the failure of the Davidic monarchy and experience of foreign domination" (324) had a profound influence upon Israel's self-understanding and their relationship with their personal God, YHWH. In post-exilic times, "when the canon of the Hebrew Bible began to take shape... Torah serves as a resource to maintain communal identity while the community endures exile and displacement; wisdom teachers shape the Psalter to emphasize how YHWH continues to abide with Israel despite foreign domination" (325).

23 Hermann L. Strack, Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash (New York, NY: Atheneum, 1980), 6. Cf. also Jacob Neusner, What is Midrash? (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2014), xi.

24 Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 286.

25 Fishbane, Biblical interpretation, 287. The term denotes "that category and range of inner-biblical exegesis which is strictly speaking neither scribal nor legal, on the one hand, nor concerned with prophecies or futuristic oracles, on the other" (280).

26 Fishbane, Biblical interpretation, 289.

27 For the use of the root in the Hebrew Bible, cf. Siegfried Wagner, "דָּרַשׁ dãrash; מִדְרָּשׁ midrash" TDOT 3:293-307.

28 Wagner, "דָּרַשׁ dãrash; מִדְרָּשׁ midrash," 294.

29 Johannes P. M. van der Ploeg, Psalmen Deel II: Psalm 76 T/M 150 (BOT; Roermond: Romen, 1974), 260.

30 Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150 (trans. Linda M. Maloney; Hermeneia; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2011), 158.

31 Wagner, "דָּרַשׁ dãrash; מִדְרָּשׁ midrash" 269, with specific reference to Isa 1:17.

32 Wagner, "דָּרַשׁ dãrash; מִדְרָּשׁ midrash," 269, with specific reference to Qoh 1:13.

33 Cf. the excursus "The Function of the 'Halleluj ahs' in the Redaction of the Psalter," in Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 39-41.

34 Cf., for instance, Erich Zenger's exegetical remarks on Pss 111:1 and 112:1 respectively (Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 163, 173).

35 A discussion of the הללו יה exclamation in Books IV and V falls outside the scope of this essay. It occurs 4x in Book IV (104:35; 105:45; 106:1, 48) and 19x in Book V (111:1; 112:1; 113:1, 9; 115:18; 116:19; 117:2; 135:1, 21; 146:1, 10; 147:1, 20; 148:1, 14; 149:1, 9; 150:1, 6). Zenger's observations regarding the distribution of the exclamation in the excursus referred to above are valid. Yet, I repeat a word of caution that I also expressed in another context. The representation of the exclamation in modern printed Bibles is misleading. In Pss 113-118, careful scrutiny of medieval Masoretic manuscripts (corroborated by superscripts in the Septuagint) prompted me to propose that the exclamation serves as superscript to Pss 113; 114; 116; 118; cf. Gert T. M. Prinsloo, "Unit Delimitation in the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113-118)," in Unit Delimitation in Biblical Hebrew and Northwest Semitic Literature (ed. Marjo C. A. Korpel and Josef M. Oesch; Pericope 4; Assen: Van Gorcum, 2003), 232-251. I suspect the exclamation frames Pss 105 and 106, serves as superscript for Pss 135 and 136, and frames each poem in Pss 146-150. The exclamation's structural function in Books IV and V needs to be revisited. Nevertheless, it appears for the first time in Book V as superscripts to Pss 111 and 112. Its semantic impact on the interpretation of the poems needs careful consideration and should not simply be glossed over.

36 Contra Franz Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Psalms, Volume 3 (trans. Francis Bolton; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973), 197 who regards Pss 111 and 112 as "only chains of acrostic lines without any strophic grouping."

37 Contra weiser, Psalms, 698 who maintains that the acrostic pattern is an "artificial conceit" that "imposes an outward form which is certainly not conducive to a consistent thought-sequence."

38 Contra Gunkel, Psalmen, 488 who describes Ps 111 as "die fromme Übung einer bescheidenen Kunst", and regards the similarities between Pss 111 and 112 as witnesses of "ziemlich große Armut in den Formen".

39 Dennis Pardee, "Acrostics and Parallelism: The Parallelistic Structure of Psalm 111," Maarav 8 (1992): 117-138 (138).

40 Pardee, "Acrostics and Parallelism," 137. Cf. also Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations (FOTL 15; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 271.

41 Pardee, "Acrostics and Parallelism," 138.

42 Cf. Pieter van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1 (OTS 63; Leiden: Brill, 2014), 238 and 246 for an overview of proposals. Cf., in addition, Pierre Auffret. "Essai sur la structure littéraire de Psaumes CXI et CXII," VT 30 (1980): 257-279; idem, "Grandes sont les oevres de YHWH: Étude structurelle du Psaume 111," JNES 56 (1997): 183-196; idem, "En memoire eternelle sera le juste: Étude structurelle du Psaume CXII," VT 48 (1998): 2-14; Ruth Scoralick, "Psalm 111: Bauplan und Gedankengang," Bib. 78 (1997): 190-205; Phil J. Botha, "'Wealth and Riches Are in His House' (Ps 112:3): Acrostic Wisdom Psalms and the Development of Antimaterialism," in The Shape and Shaping of the Book of Psalms: The Current State of Scholarship (ed. Nancy deClaissé-Walford; AIL 20; Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2014), 105-128. Even scholars who emphasise the close relationship between Pss 111 and 112 have diverging proposals regarding their structure(s); cf., Schildenberger, "Das Psalmenpaar 111 und 112," 203-207; Beat Weber, "Zu Kolometrie und strophischer Struktur von Psalm 111 - mit einem Seitenblick auf Psalm 112," BN 118 (2003): 62-67; idem, Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150 (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2003), 226-233.

43 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 161.

44 Yair Zakovitch, "The Interpretive Significance of the Sequence of Psalms 111112.113-118.119," in The Composition of the Book of Psalms (ed. Erich Zenger; BETL 238; Leuven: Peeters, 2010), 215-227 (216).

45 VanGemeren, Psalms, 700.

46 A. Cohen, The Psalms (Soncino Books of the Bible 1; Hindhead, Surrey: Soncino, 1945), 343.

47 Walter Brueggemann and William H. Bellinger Jr., Psalms (NCBC; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 482.

48 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 482.

49 VanGemeren, Psalms, 702.

50 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen II, 260.

51 Allen, Psalms 101-50, 120.

52 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 163.

53 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 163.

54 GKC §116a; Joüon §121c.

55 GKC §116e; Joüon §121i; cf. Allen, Psalms 101-50, 121.

56 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 165.

57 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 158; Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 482.

58 VanGemeren, Psalms, 702.

59 Allen, Psalms 101-50, 125.

60 VanGemeren, Psalms, 702.

61 Allen, Psalms 101-50, 125.

62 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

63 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

64 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

65 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 483.

66 VanGemeren, Psalms, 705.

67 VanGemeren, Psalms, 705.

68 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

69 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

70 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

71 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen II, 261.

72 Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 2, 272.

73 Briggs and Briggs, Psalms 2, 383.

74 Phil J. Botha, "The Measurement of Meaning - An Exercise in Field Semantics," JSem 1 (1989): 3-22 argued that פקודים thus belongs to the תורה semantic domain. The Torah is tangible evidence of Yhwh's power as it manifested in Israel's redemptive history (Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164).

75 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 164.

76 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 483.

77 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 165.

78 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 165.

79 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen II, 262.

80 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 483.

81 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 483.

82 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 165.

83 Mays, "The Place of Torah-Psalms," 5-6.

84 Dahood, Psalms III, 125.

85 Allen, Psalms 101-50, 121.

86 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 165.

87 The two forms occur in chiastic order: לעד (3b = x); לעולם (5b = y); לעולם (8a = x+y); לעד לעולם (9b = y); לעולם (10c = x).

88 The root הלל frames the entire poem (superscript; 10c).

89 The root עשה frames the stanza recounting YHWH's redemptive intervention in the history of Israel (4a; 6a).

90 The root נתן frames the strophe recounting YHWH's gracious provision of food and land to his people (5a; 6b).

91 The root עשה frames the stanza recounting Yhwh's redemptive gifts of his precepts to his people (7a; 8b). Similarly, the sequence עשה - אמת - משפט (7a) is echoed in the sequence עשה - אמת - ישר (8b), confirming that "doing" frames the stanza, but from two perspectives - first from the divine (7a) and then from the human (8b). Moreover, the passive participles נאמנים (7b) and סמוכים (8a) function as synonyms defining the reliability of Yhwh's פקודים, creating an overall chiastic pattern in the stanza's structural plan: עשה - אמת - משפט (7a) / נאמנים (7b) // סמוכים (8a) / עשה - אמת - ישר (8b).

92 A broad chiastic relationship exists between Stanzas 2 and 3 through the repetition of the nouns עם and ברית:בריתו (5b) / לעמו (6a) // לעמו (9a) / בריתו (9b).

93 The poem concludes by alluding to various earlier themes. יראת יהוה continues the notion of reverence from the previous colon (נורא in 9c). עשיהם concludes the central theme of the poem centring around the root עשה. The notion introduces Strophe 1.2 (2a), frames Stanza 2 (4a; 6a), frames Strophe 3.1 (7a; 8b) and concludes Stanza 4 (10a). The adverbs of time לעד and לעולם occur in chiastic order: לעד (3b) / לעולם (5b) / לעולם (8a) / לעולם (9b) / לעד (10c). The repetition of the phrase עמדת לעד (3b; 10c) concludes the first and last stanzas. Finally, the root הלל frames the entire poem (superscript; 10c).

94 VanGemeren, Psalms, 700.

95 Zakovitch, "Interpretive Significance," 216.

96 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 173.

97 Allen, Psalms 101-50, 130.

98 Brueggemann and Bellinger, Psalms, 486.

99 J. Clinton McCann Jr., "The Book of Psalms," in The New Interpreters Bible, Vol. IV (ed. Leander E. Keck; Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996), 641-1279 (1136).

100 Zakovitch, "Interpretive Significance," 216.

101 Erich Zenger, "Dimensionen der Tora-weisheit in der Psalmenkomposition Ps 111-112," in Die Weisheit - Ursprünge und Rezeption. Festschrift für Karl Löning zum 65. Geburtstag (ed. Martin Fassnacht et al.; NTAbh 44; Münster: Aschendorff, 2003), 37-58 (53).

102 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 168.

103 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen II, 265.

104 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 174.

105 J. Kenneth Kuntz, "The Retribution Motif in Psalmodic Wisdom," ZAW 89 (1977): 223-233 (230).

106 Erich Zenger, "Geld als Lebensmittel?" Reichtum im Psalter (Psalmen 15.49.112)," JBTh 21 (2006): 73-96 (82) argues that the repetition of the same colon in Ps 111:3b and Ps 112:3b, 9b indicates that enduring righteousness is the theme of both poems.

107 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 168.

108 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen II, 265. Consequently, n-T in the previous colon is applied to Yhwh and the three adjectives in v. 4b are interpreted accordingly (Van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes III, 243). This interpretation is corroborated by Codex Alexandrinus' addition of κύριος ό θεός (cf. Zenger, "Geld als Lebensmittel?" 84 n. 17). This interpretation negates the boldness of the claim in Ps 112:4 that the righteous should reflect the characteristics of Yhwh in his dealings with others.

109 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 174.

110 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 174.

111 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 174.

112 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 174.

113 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 174.

114 McCann, "Book of Psalms," 1136.

115 VanGemeren, Psalms, 710 states: "He may experience all kinds of surprises in life, but he will persevere in doing good."

116 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen II, 266.

117 VanGemeren, Psalms, 710.

118 Dahood, Psalms III, 129.

119 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 175.

120 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 175.

121 Briggs and Briggs, Psalms 2, 387.

122 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 3, 175.

123 Psalm 1 begins and ends with exactly the same lexemes. This phenomenon suggests an important intertextual relationship between Ps 112 and Ps 1. Spatial constraints do not allow for a discussion of this relationship, but it emphasizes the overall theme of both poems, i.e., the righteous enjoys a blessed existence, while the wicked is heading for disaster; cf. van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes III, 247-248.

124 The repetition of לא יירא creates a parallelism between 7a and 8a. At the same time, the wordplay between לא יירא (7a) and אשר־יראה (8b) and the parallel expressions נכוןלבו (5b) and סמוך לבו (6a) constitute a chiastic relationship between the four cola of Strophe 3.1.