Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.32 no.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n2a12

ARTICLES

Song(s) of Struggle: A Decolonial Reading of Psalm 137 in Light of South Africa's Struggle Songs

Hulisani Ramantswana

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article engages in a decolonial reading of Ps 137 in light of South African songs of struggle. In this reading, Ps 137 is regarded as an epic song which combines struggle songs which originated within the golah community in response to the colonial relations between the oppressor and the oppressed. The songs of struggle then gained new life during the post-exilic period as a result of the new colonial relation between the Yehud community and the Persian Empire. Therefore, Ps 137 should be viewed as not a mere song, but an anthology of songs of struggle: a protest song (vv. 1-4), a sorrow song (vv. 5-6), and a war song (vv. 79).

Keywords: Psalm 137, Songs of Struggle, protest song, sorrow song, war song, exile, Babylon, post-exilic, Persian Empire.

A INTRODUCTION

Bob Becking, in a paper entitled "Does Exile Equal Suffering? A Fresh Look at Psalm 137,"1 argues that exile and diaspora for the exiles who were in Babylon did not so much amount to things such as hunger and oppression or economic hardship; instead, it was more a feeling of alienation which resulted in the longing to return to Zion. Becking's interpretation of Ps 137 tends to minimise the colonial dynamics involved in the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed, the coloniser and the colonised, which continually pushes the oppressed into the zone of nonbeing.

Berquist, in his study entitled "Psalms, Postcolonialism, and the Construction of the Self," argues that

the psalms were part of the empire's control of the region through its ideological, social control of persons and lives. ... Psalms offer words and social spaces that shape individual experiences and emotions into socially accepted expressions, which at least indirectly serve imperial interests.2

While there are psalms which reflect imperial domination over the subjects, it does not necessarily follow that the psalter in toto served the interests of the empire.

Zenger regards the Psalter in its final form as being "anti-imperial,"3 but in my view, he goes to the extreme by so doing. Certain psalms may be regarded as anti-imperial; however, this does not render the Psalter as a whole an anti-imperial book.

In this paper, Ps 137 is read from a decolonial perspective in light of struggle songs in the South African context. Ps 137 is read as an epic psalm which combines songs of struggle which originated within the golah community in Babylon and were reborn during the post-exilic period within the Yehud community when the golah community returned. Therefore, Ps 137 is an anthology of struggle songs which engage issues of imperial power and domination by capturing the anxieties of the exilic period and the post-exilic period.

B PSALM 137: SONG(S) OF STRUGGLE

The songs in the Psalter reflect various linkages between songs and other spheres of life-the link between songs and cult, that is, psalms as reflecting ceremonial activities linked to the cultic places of worship, be they the temple or other places of worship, and whether in the pre-exilic period, exilic period, or post-exilic period; the link between songs and the wisdom movement, that is, songs associated with the wisdom circle; songs linked with an individual's experiences in life; songs linked with a community's experiences, and songs that are political or politically enthused. It is no wonder that some scholars classify the genre of Ps 137 as a communal lament or communal complaint;4 however, such a classification does not go far enough. Within this broader genre, Ps 137 should be viewed as an epic "song of struggle" in that it brings shorter songs together, which are politically charged.5 The epic nature of the songs is manifested not so much in the length of the song in its final form as in its weaving together songs of struggle into one song of struggle.

A song of struggle or liberation song is politically motivated, and it is intended to advance a political cause with reference to historical events. In the South African context, struggle songs form part of the political discourse. Among other atrocities committed during the colonial-apartheid era, the natives were dispossessed of their land, and society was racialised, with whites classified as superior and blacks as inferior. In Fanonian terms, blacks were condemned to a situation of "damnation" and relegated to the "zone of nonbeing." Thus, during the colonial-apartheid era, black people used songs, on the one hand, as a healing balm for dealing with the hellish day-to-day experience of a violent system and, on the other hand, as a weapon in the struggle for instilling the ideology of the struggle in the consciousness of people, to mobilise and express political dissent.

The struggle songs reflect on the historical events which produced the hellish experience in the lives of people. As Pring-Mill argues, such historical events are "recorded passionately rather than with dispassionate objectivity, yet the passion is not so much that of an individual singer's personal response, but rather that of a collective interpretation of events from a particular 'committed' standpoint."6 As Mariam Makeba indicated in her CD flier in 1998,

In our struggles, songs are not simply entertainment for us. They are the way we communicate. The press, radio and TV are all censored by the government. We cannot believe what they say. So we make up songs to tell us about events. Let something happen, and the next day a song will be written about it. (Sangoma CD flier, 1998).

During this period, as Schumann notes, the struggle songs promoted unity and endurance among the oppressed people as they [the oppressed] addressed directly and frankly the unjust treatment by the oppressive system.7 Through struggle songs, the oppressed denounce the oppressor or oppressive state by mentioning names of state representatives. Yet other struggle songs were addressed not to the oppressor, but to the stalwarts of the liberation movement as a deliberate strategy to encourage the leaders of the movement. Reed, reflecting on the use of music in the civil rights movement in the United States of America, writes,

Singing in the black tradition is very much a participatory event. Thus, going to a movement meeting even just to listen, could quickly lead to deeper levels of involvement. Get their voices, one might say, and their politics will follow. Music becomes more deeply ingrained in memory than mere talk, and this quality made it a powerful organizing tool. It is one thing to hear a political speech and remember an idea or two. It is quite another to sing a song and have its politically charged verses become emblazoned on your memory. In singing, you take a deeper level of commitment to an idea than if you only hear the idea spoken of. The movement was all about "commitment," and singing was often a halfway house to commitment.8

Struggle songs may be viewed as their own separate category or genre; within this genre, however, sub-genres may also be identified. The following classification may be utilised to classify some of the South African struggle songs:9protest songs,10 resistance songs or war songs,11 sorrow songs,12 and courage songs.13

In the South African context, struggle songs tend to be characterised by brevity. The struggle songs were not intended to be speeches; rather, they are politically charged stanzas which easily become engraved in one's memory. The lyrics were sung repetitively, making the songs easy to learn, and they therefore also had the power to move people emotionally. Different songs always have different effects: "lightning never strikes twice in the same place." This implied that "people easily sing along and not much worry about singing out of tune -given that one's voice is submerged in countless other voices."14

Returning to Ps 137, this psalm, unlike many other psalms which do not reflect their historicity, unequivocally points to the historical setting that it is reflecting on-the Babylonian exile period.15 However, some scholars regard the song as having been written in retrospect - as a reflection on the original event.16While such a possibility cannot be ruled out, if Ps 137 is viewed as a song of struggle, a more radical stance is required. The psalm - at least in its oral form -likely originated during the exilic period, and as such, it would have been sung in the face of the oppressor to express the plight of the oppressed: their dissatisfaction with the status quo, the dislocation from their land, and their suffering and marginalisation in the foreign land.17 Furthermore, on close examination, Ps 137 seems to be more than just one song and it should rather be viewed as an anthology of struggle songs.

An anthology, as Willgren defines it, "is a compilation of independent texts, actively selected and organized in relation to some present needs, inviting readers to a platform of continuous dialogue."18 Willgren's interest, however, is more at the canonical level or macro level, the formation of the Psalter as a "book" and not so much at the formation of individual psalms. The interest in the formation of the Psalter has been subject of interest for psalm scholars. As Wenham argues, the Psalter as a book is not a mere random collection of psalms, rather it is "a carefully arranged anthology that gives clues to the editors' intentions from the sequence of the psalms and their titles."19 Thus, an anthology is a creative work, which brings together texts that were originally independent of each other, thereby creating something new.

Anthological creativity, however, does not only apply at the canonical level or book formation level, but also at the micro-level of the individual psalms. For example, Pss 1, 25, 33, 34, 34, 103, 111, 112, 119, 145 are viewed by some scholars as anthological psalms, which make use of other corpora of Scripture, Torah and the Prophets.20 Psalm 70 presents an interesting case: First, Psalm 40 may be considered an anthological psalm proper considering that verses 13-17 of this psalm are the same as Ps 70, with minor textual variations. While it is difficult to ascertain if the composer of Ps 40 made use of Ps 70 or if Ps 70 as an independent psalm is drawn out of Ps 40; however, as Mays notes, Ps 70 appears as a literary complete psalm, which favours the possibility that it was used in Ps 40.21 This may also imply that two originally independent psalms are merged into one in Ps 40. Second, Ps 70 and Ps 71 are amalgamated into one psalm in several other Hebrew manuscripts as highlighted in the text-critical note of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). In the Masoretic Text (MT), Ps 71 does not have a superscript, which probably explains why other Hebrew manuscripts combined the two psalms.22 Third, in the Septuagint (LXX) the two psalms (70 and 71) are intentionally separated from each other as Ps 71 has its own superscript. The case of Psalm 70 highlights some of the ways in which an anthological psalm may be formed: (a) originally independent psalms may be merged together to form one psalm, (b) a whole psalm may be used in another psalm, and (c) in the process of canonical arrangement of the psalms or the Psalter, certain psalms were merged together or separated from each other as evidenced by the different textual traditions of the Psalter.

Psalm 71 adds other interesting dimensions. Psalm 71 like Ps 40 is also an anthological psalm. While the concluding part of Ps 40:13-17 is the same as Ps 70, in the case of Ps 71, the introductory section of the psalm, vv. 1-3 is the same as Ps 31:2-4, with some variations. Furthermore, considering that some Hebrew manuscripts do merge Ps 70 and Ps 71 into one, it would imply that new composition incorporated within it a segment of Ps 40 and Ps 31:2-4. These observations highlights the following regarding anthological psalms: (a) an introductory portion of another psalm could be drawn and be utilized to introduce another psalm, and (b) taking into consideration the merging of Ps 70 and 71 in other Hebrew manuscripts, it points to the redactors willingness to create a new psalm which could be perceived as drawing together ideas from multiple psalms.

Another, interesting case is that of Ps 108. This is an anthological psalm formed using portions from two originally independent psalms (Ps 108:2-6 = Ps 57:8-12 and Ps 108:7-14 = Ps 60:7-14). In this new creation, the composer does not merely juxtapose the two texts but also inserts other elements to the new psalm. In addition, the psalms is also provided with a Davidic heading. As Botha argues, "the purpose of creating a new composition from two existing texts was to facilitate an 'anthological' recasting and re-reading of earlier texts which must have been known to the audience of Ps 108. In this way, the earlier texts were "commented" upon and their horizons expanded."23

It is also worthy to note that the LXX Ps 151, which concludes the Greek Psalter, is likely an anthology of originally two separate psalms as evidenced by the 11QPsa 151A and 151B, which appear in the Qumran Psalter. In 11QPsa the two psalms are separate with each having its own superscript; however, in the LXX it is one psalm. As Flint notes, LXX Ps 151 was either a reworking and a synthesizing of the Greek translator into a single psalm or the translator was translating with an already reworked and synthesized Hebrew text.24

Taking into consideration the various ways through which anthological psalms could be formed, it may be concluded that the role of an anthology is to serve as a "medium for the transmission, preservation, and creation of tradition."25 With an anthology the creativity basically lies in the selection, juxtapositioning, insertions, and thereby setting the originally independent texts in a new context.26

In the case of the Ps 137, some scholars have observed that this psalm contains different elements: lament, a song of Zion, and a curse / call for vengeance.27 In terms of the arrangement of the psalm, scholars generally agree that it has a three-fold division:28

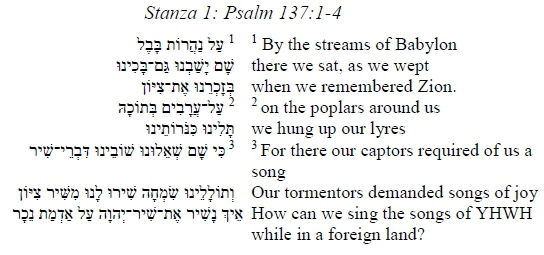

Stanza 1: Ps 137:1-4

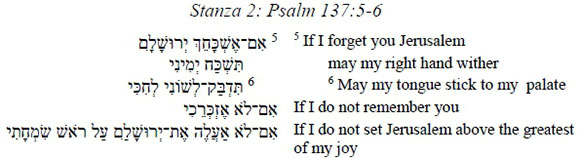

Stanza 2: Ps 137:5-6

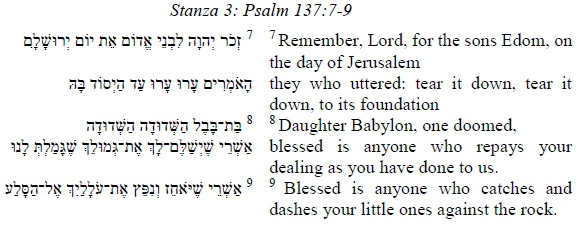

Stanza 3: Ps 137:7-9

Scholars, however, do not entertain the idea that this psalm is an anthological psalm in which the authors or singers brought together different struggle songs which originated during the time of exile. Therefore, in my view, Ps 137 may be viewed as a collection of three struggle songs in which can be heard the "voices of exile" filled with the pain of exile.

If we regard the three stanzas as originally self-standing songs, it will imply that they were short psalms like Psalm 117, which has brevity as its hallmark. However, in the case of Psalm 117, different textual traditions combine this psalm with either Psalm 116 or Psalm 118. It remains a possibility that over time short psalms could have been combined to form one song or amalgamated with other psalms as per the redactors' discretion. Some psalms, such as Ps 108, which are composed of segments from different psalms (Ps 57:8-12 and also Ps 60:7-14), and LXX Ps 151, which is a reworking and synthesizing of 11QPsa151A and 151B, indicate the possibility of forming new psalms based on existing psalms.29 The view I espouse below regarding Ps 137 is that it is composed of three struggle songs which originated within the golah community during the exilic period in Babyon.

C PSALM 137:1-4: SONG OF PROTEST

From a decolonial perspective, Ps 137:1-4 is more than a mere song about the plight which those in the struggle faced; rather, it is a politically charged song which was intended to motivate the oppressed to defy the oppressive forces. The request by the captors (שׁוֹבֵינוּ) / tormentors (שְׁׁאֵלוּנוּ) is not to be viewed as an innocent request out of curiosity by the Babylonians considering the dynamics at play between the coloniser and the colonised. Rather, the oppressed do not view the request as innocent, and the language they use is telling. Indeed, some interpreters regard the request (or the plea or the demand) of the captors/tormentors as a mockery of the exiles,30 and considering the dynamics at play between colonisers and the colonised, the request for a song from the captured (the exiled Judaean / golah community) should be viewed as an act of censorship by the oppressor amounting to control of what could be sung and not sung.

In the South African context, during the colonial-apartheid period, the state through its Directorate of Publications sought to have direct censorship of materials published and sounds recorded.31 As Delby notes,

In a society characterised by censorship and state control, coupled with significant social tensions, music can become both a safe haven and a centre of controversial discourse ... Political songs act as social commentaries, expressing stinging critiques aimed at the government.

The lyrics of protest songs can threaten the state, or endanger 'the whole fabric of society'.32

The oppressive state through its censorship was not simply willing to control what was sung; it also wanted to silence the composers of struggle songs. For example, Vuyisile Mini, a composer of struggle songs, a poet, and a singer and trade unionist in the ANC movement, was jailed and charged with treason in 1956 and, along with two co-accused, was executed in 1964. Mini composed protest songs such as "Naants'indod' emnyama, Verwoerd!" (Here is a black person, Verwoerd!), "Izakunyathel' iAfrika, Verwoerd" (Africa is going to trample on you, Verwoerd). Others who continued in the path of composing protest songs - such as Mariam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, and Abdullah Ibrahim - were exiled; "[t]heir words were deemed dangerous because they were a critique of injustice of apartheid."33 What the oppressive state required were so-called lekkerliedjies (nice songs) which would not threaten the state.34 When the censures mounted, resisters used a number of strategies including going underground to continue the resistance. Underground movements then mushroomed and continued to advance the ideological position and used other subtle musical strategies - code-switching, new styles, new themes, etc. - in an attempt to outwit the oppressor.35

Turning back to Ps 137:1-4, the request for "songs of Zion" by the captors/tormentors should be viewed as a request for lekkerliedjies which would not challenge or threaten the empire. The songs of Zion would thus have been songs which have nothing to do with the current realities which the golah community faced in Babylon. The request for songs of Zion was in all likelihood because the captors were suspicious of the songs that the golah community was singing.

The struggle songs during the exilic period in all likelihood would have run contrary to the ideological position held by the pro-Babylonians back in the land and among the exiles who opted for submission. The pro-Babylonian elements would have served the agenda of the oppressor, preaching assimilation (Jer 29:5-7) and warning of the dangers of not assimilating (Jer 29:8). As Brueggemann argues, "The pro-Babylonian cast of the material is not simply political ideology or pastoral sensitivity towards exiles, but it is finally a daring judgement of faith about God's will and work in the world. The blessed, in the end, are those who accept this version of reality."36 The pro-Babylonian ideology was a version of reality not accepted by all the exiles.

The question "How can we sing the songs of YHWH while in a foreign land?" is indicative of the trauma of exile. The golah community sat or dwelled by streams of water,37 indicative of the potential for it to thrive within the domain of the capturer, yet for the psalmist, the situation did not evoke emotions of joy, as it was not in Zion. As Hays notes, "[t]he first verse's "by the rivers of Babylon," may recall Ps. 23's ''rtnr nima 'öf^y,' but with echo. Here the Lord has not given his people rest, but appears to be absent."38

This is in contrast to the pro-Babylonian ideology, which pictured the exiles' condition as one of the tolerable conditions. As Bar-Efrat argues, while the conditions in exile may have improved materially, "[a]longside the abundance of water was the memory of Zion, and it weighed more heavily."39

However, I am inclined to concur with Ahn that Psalm 137:1-4 likely reflects the social condition of the first wave of exiles of 597 BCE.40 Thus, the first wave of displaced people at the streams of Babylon was to serve the captors by engaging in hard labour at irrigation canals. These immigrants continually wept when they recalled their own land, which they left not voluntarily but forcibly, and furthermore that they now had to face the prospects of losing their identity, culture, and language.41

This protest song, thus, comes as a response to the forced immigration and the hard labour at Babylon's canals, coupled with the longing to return to the land; it also comes as defiance against the censure from the captors to quell revolution that could be sparked through struggle songs. Attempts to flee from exile or fight back cannot be excluded from the picture - as some from the golah community would have attempted to resist their enslavement through attempts to fight back or escape. The book of Daniel seems to recall instances of religious protests in which the protesters were prepared to die, and it is highly likely that similar standoffs would have also occurred by the canals where the exiles would have been labouring while singing the slave songs as weapons of their struggle. As Hays observes,

The Jews 'show their defiance to the captor not by refusing to sing, but by what they sing,' they 'fill a recognizable form with an unexpected content.' They wanted to lay aside their harps; but now they are compelled to sing, so they take comfort in this song of national pride. In the temple, the Lord's song comes out as praise; but in exile, everything is inverted, and it comes out as anger.42

As Joerstad also notes regarding Steve McQueen's movie 12 Years a Slave,43the songs that slaves sang when in the daily labour in the field served a practical purpose, giving rhythm to the work and allowing the supervisor to know the whereabouts of each, and yet they were songs of defiance and hope.44

D PSALM 137:5-6: A SONG OF SORROW

While this song is somewhat linked thematically, to the song in Ps 137:14, there are textual indicators which set this song apart from the previous protest song: 1) this song is arranged around the conditional clauses introduced by (if; vv. 5, 6b, c);45 2) the name "Jerusalem," occurring in 5a and 6b, forms an inclusio (as does the name Zion in verses 1 and 3); the song is in the first person singular (I), unlike in the previous song, which is in the first person plural (we).

While this shift may be viewed in Brueggemann's terms as a reflection of a shift from disorientation (vv. 1-4, as the exiles found themselves at a loss in the new location of oppression-away from their land) to reorientation (vv. 5-6, as the exiles reflected on Jerusalem, a familiar location back in their land).46 However, in this case, the shift in the use of the first person and the use of conditional clauses may just as well reflect an amalgamation of originally independent psalms in a new creative context.

Freedman notes that vv. 5-6, which form part of the central section of the psalm as a whole, are "an artfully designed chiastic couplet which is at once the dramatic high point or apex of the poem and the axis linking the parts and exhibiting the essential structure of the whole."47 This is so if the final form of the psalm is considered; however, we do well to consider the likely development of the psalm.

Following Du Bois's classification of some of the songs of the black slaves in the USA as "sorrow songs,"48 Psalm 137:5-6 may be classified as a sorrow song. Describing the sorrow songs, du Bois states,

[T]hese songs articulate message of the slave to the world . They are music of an unhappy people, of the children of disappointment, [and] they tell of death and suffering and unvoiced longing toward a truer world, of misty wanderings and hidden ways.49

In the South African context, a song such as "Senzenina" captures the deep sorrow of the black people, whose land was violently and forcefully taken away from them through both the colonial and apartheid machineries and who were classified as inferior.

Senzenina? What have we done?

Sono sethu ubunyama Our sin is being black.

Sono sethu iyinyaniso Our sin is the truth.

Sibulawayo For that we are killed.

Mayibuye iAfrika Let Africa return.

The final words of this song, "mayibuye iAfrika," were a liberation slogan as the oppressed people looked forward to the day in which Africa, their land, would be returned to its rightful owners. Amid the sorrow, there was a sense of hope.

In the case of Ps 137:5-6, it is a song of a people who could not challenge the Babylonian empire militarily or through violence to bring about meaningful change. The first wave of exiled Yehudites would have been well aware of the failed attempts to regain power by Zedekiah and Ishmael. In his/her sorrow, the psalmist makes a vow not to "forget" Jerusalem and invokes on the self, a curse - right-hand paresis and loss of speech, which would imply a loss of ability to sing and play a musical instrument.

As Biko reminded his comrades during the heyday of colonialism and apartheid in the South African context, "[T]he most potent weapon in the hand of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed." In a way, the psalmist in Ps 137:56, although physically captured and exiled and oppressed in Babylon, was not willing to surrender his/her mind to the oppressor, and despite the many atrocities that he/she faced, he/she vowed not simply to remember the good old days in the land from which he/she had been displaced, but also to gain freedom in the future with the hope of returning to Jerusalem. As du Bois notes regarding the song of the black slaves, "Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope - a faith in the ultimate justice of things. The minor cadences of despair change often to triumph and calm confidence."50

In the context of Ps 137:5-6, the remembrance of Jerusalem evokes the motif of freedom, reverse immigration, or a new exodus. The exaltation of Jerusalem in v. 6b ("If I do not set Jerusalem above the greatest of my joy") cannot be set in the past; it is rather a future hope. Considering the Psalter in its final form, Pss 135 and 136 capture the exodus motif through praise of Yahweh as the rescuer of his people.51 The new exodus would not be to a "strange land" but a return to the psalmist's own land, which would be a fulfilment of his/her joy. In the context of the song, the exile moment is a moment of sorrow, and the time of joy is still in the future.

E PSALM 137:7-9: A SONG OF REVENGE/WAR

The theme of remembrance continues in this section of the psalm, there is, however, a significant shift. It is not the oppressed people who are called to remember in this case; rather, it is the God of the oppressed people who is called by them to remember their enemies, Edom and Babylon. The remembrance, in this case, does not carry any positive sentiments. The oppressed do not prescribe the form of judgment that should be meted out against Edom, but they do prescribe the form of judgment that should be meted against Babylon. This section of the psalm or this song is a song of revenge or war.52 The violence that is wished on the enemies, particularly Babylon, is of the worst possible evil -their babies are to be captured and smashed against stones.

The violence that is wished on Babylon, as Hays argues, is not "new and unheard-of evil"; rather, it was common in ancient warfare.53 In similar instances, the atrocity of dashing children is coupled with the killing of unborn babies by killing pregnant mothers or ripping them open (Isa 13:16; Hos 10:1315; 13:16/14:1; cf. 2 Kgs 15:16; Amos 1:13).54 The motif of death or killing of children also evokes the exodus motifs. In the exodus story, the Egyptians sought to disempower the Hebrews by killing the Hebrew baby boys at birth (Exod 1:1617), and on the reverse, the act that finally led to the eventual release from Egypt was the killing of every firstborn in Egypt, human and animal (Exod 13:15). The extreme violence wished on Babylon in decolonial terms reflects the imperial non-ethical conduct of war, which included among other things rape, the ripping open of pregnant women, the killing of new-borns, torture, mutilation, genocide, destruction of property and sacred places, enslavement, capture and deportation.55 Inasmuch as the modern reader may take offence at the horrendous violence that the oppressed wished for their mockers and oppressors, it cannot be erased or explained away. This is a song against the oppressor, which Bridgeman regards as an "anti-song."56

I concur with those who argue that this portion of the psalm originated during the exilic period following the events of 587 BCE as an expression of the vengeance the writer desired on the enemies.57 The psalmist's call has to be viewed as a call for a form of retributive justice, that of lex talionis (in Hebrew TS? rinn T37, "an eye for an eye").58 Thus, it may even be that what the psalmist wished for Babylon was a counterbalancing act to be meted out against the oppressor. However, it is worthy to note that when the Persian empire overthrew the Babylonian empire, it did not occur with the kind of violence called for in this song.59 This as a key indication that this song reflects the exilic environment. As Hays notes, "It is not likely that the psalm was composed much later, for then the sentiments would have found little traction in the nation's political consciousness."60

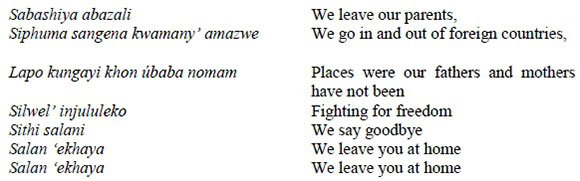

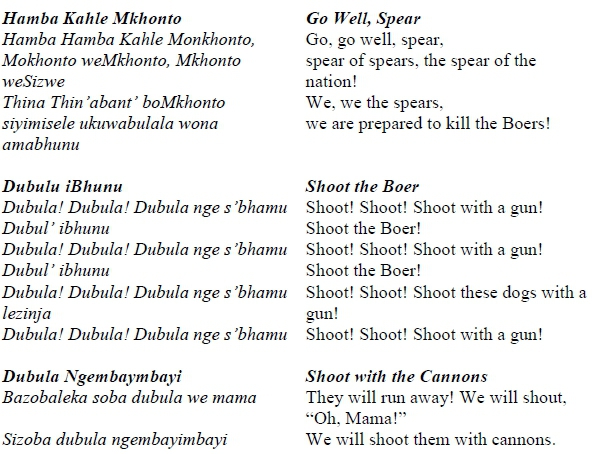

In the context of oppression, it is not uncommon that the oppressed would want to retaliate against their oppressors. In the South African context, some of the struggle songs were war songs intended to inspire the people to fight back against their oppressors. Moreover, the liberation movements had gone to the extent of organising a military wing, uMkhonto weSizwe (The Spear of the Nation)61, to resist a ruthless and oppressive state; this organization was "a turn to violence" or "a turn to armed struggle."62 Therefore, songs such as "Sabashiya abazali," "Hamba kahle uMkhonto," "Dubula ibhunu," and "Dubula ngembaymbayi, umshini wami" reflect the turn to violent resistance. The song "Sabashiya abazali" captures the mood of those who joined the MK and had to leave their homes to go to the training camps:

The theme that runs through the other songs is that of combat - reflected by the readiness to kill the oppressor as a way of fighting in defence of the people and for freedom.

Nelson Mandela captured the rationale for "a turn to violence" as follows:

[W]e felt that without violence there would be no way open to the African people to succeed in their struggle against the principle of white supremacy. All lawful modes of expressing opposition to this principle had been closed by legislation and were placed in a position in which we had either to accept permanent state of inferiority or to defy the Government.63

Thus, while freedom can be negotiated peacefully, it is not always possible. The colonial-apartheid system of domination had as its mode of operation exploitation, oppression, and violence. As Fanon observed,

Colonialism is violence in its natural state and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence. The policeman and the soldier, by their immediate presence and the frequent and direct action, maintain contact with the native and advise him by means of rifle butts and napalm not to budge. It is obvious here that the government speaks the language of pure force. The intermediary does not lighten the oppression: he shows them up and puts them into practice with a clear conscience of an upholder of peace: yet he is the bringer of violence into the home and into the mind of the native.64

In colonial-apartheid South Africa, the military and police ensured that the state maintained domination and control through their treatment of black bodies with impunity, disdain and violence. Therefore, black bodies, whether young or old, were punishable, imprison-able, torturable and even forcefully removable, shootable, and killable, etc. Considering the violent nature of the colonial-apartheid machinery, there arose the need to use counter-violence as a strategy against the oppressor. While the struggle songs tend to imagine a blood-feud between blacks and whites, the heart of the struggle was to target those things which were symbols of white supremacy, privilege, and domination.65Underlying the struggle songs was the demand for freedom and decolonial justice.

Decolonial justice has as its preferential option the damned, that is, the oppressed/colonised. Modern colonialism, as Maldonado-Torres argues, radicalised and naturalised the non-ethics of war by rendering the conquered as inferior and therefore condemning the conquered to a position of slavery and the day-to-day hell of "killability" and "rapeability."66 However, the hope of the future lies with the damned, the wretched of the earth, when they become agents of transformation. As Maldonado-Torres argues,

The damnés have the potential of transforming the modern/colonial into a transmodern world: that is a world where war does not become the norm or the rule, but the exception.67

Decolonial justice is not the trading of one oppressor with another, where the previously oppressed become the new oppressors; rather, it is the demand of a just society in which colonial structures of domination and oppression of the other are undone.

In the context of Ps 137:7-9, the damned, the oppressed Yehudites, could not engineer the overthrow of the empire from below; they had to rely on the possibility that another imperial power would overthrow Babylon and hopefully secure their freedom. However, their view of attaining freedom through another form of imperial violence perpetuates the naturalisation of war in which the conquered are killable and so their babies. Decolonial justice does not preclude the use of violence to attain freedom, yet the goal is to denormalise and denaturalise the non-ethics of war.

F STRUGGLE SONGS TRAVEL: STRUGGLE SONGS IN POST-EXILIC YEHUD AND IN POST-COLONIAL, POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA

Songs originating in one setting can resonate in another similar setting. While some scholars regard Ps 137 as a post-exilic psalm which captures the anger and sorrow of those who had returned from exile, the songs contained within this psalm should rather be viewed as originating from the exilic context, though they gained new life within the post-exilic context. Inasmuch as the fall of Babylon to the Persian Empire under Cyrus brought about policy change which gave those from the golah community the freedom to return to their land if they wished to do so, Yehud remained a colonised entity under the Persian Empire. The freedom from Babylon did not bring about the end or the collapse of colonial relations. The Yehud community in the post-exilic period was "a community with a colonial memory" of living in a foreign land now living in a colonised setting in their own land.68

In the post-exilic period, the Yehud community also had to deal with the Edomites. While the reference to Edom in Ps 137:7 reflects the attitude of Edom towards the fall of Judah in 587 BCE, it also reflects how the golah community regarded Edom as one of her archenemies even to the extent that Edom is mentioned alongside Babylon.69 In biblical tradition, Edom is presented as Israel's brother, and in their relationship, there was a sense of hostility (Gen 2526; cf. Obad 8-10). These brothers continued to live alongside each other even in the post-exilic period. During this time, as Dicou argues, the returnees from exile who wished to regain the land would have been frustrated by the other peoples who occupied the land, including the Edomites.70 The revival of a song such as Ps 137:7-9 would have helped fuel the tensions between the Yehud community and Edom in line with the majority view as propagated by those who returned from exile. However, the tradition preserved in Deut 23:7 called for the peaceful coexistence of the two despite the fallout: "You shall not abhor the Edomite, for he is your brother."

As Gunner highlights, songs "travel, they metamorphose, they die, sometimes they are reborn, and they give birth. They are midwives to new ideas and new social vision. They summon up collective memory with amazing speed."71 It is highly likely that those struggle songs, which originated within the belly of the beast in Babylon, would have been reborn within the post-exilic period from the collective memory of the returnees from exile. In the case of the songs contained within Ps 137, they were reborn not as short and cryptic songs, but rather as an epic which brought together originally independent songs.72

In the Southern Africa region, some struggle songs travelled among the liberation movements across the colonial borders.73 Furthermore, in the South African context, struggle songs continue to feature prominently in the current post-colonial, post-apartheid dispensation in political rallies and protest marches. The times have changed, however, the struggles faced are to some extent rooted in centuries of colonialism, and others reflect current socio-economic challenges. In this context, the struggle songs are reborn, recast, and adapted to address the current struggles, whether it be in service delivery protest, industrial action, or some other context. In addition, political organizations utilize struggle songs in order to tap into historical memory to garner the support of their members by reminding their supporters of their past and continuing sufferings as the result of colonisation and apartheid. The struggle songs, as Jolaosho notes, "constitute legacies from the past, they indicate present dynamics and offer directives toward the future."74

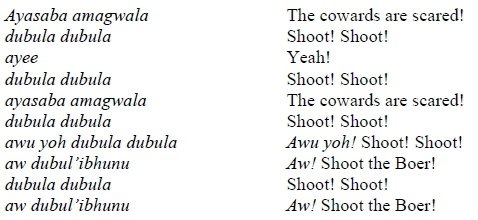

In South Africa's current post-colonial, post-apartheid context, others wonder about the relevance of struggle songs, particularly, those that seem to fuel animosity between blacks and whites, such as "Dubula ibhunu " (Shoot the Boer) or "Ayesaba Amagwala" (The Cowards Are Scared).

In the case of the present rebirth of this song, the matter was taken up to the court in 2010 following complaints lodged with the South African Human Rights Commission and the Equality Court against the then African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) president, Julius Malema. The South Gauteng High Court ruled that the words dubula ibhunu (shoot the Boer) in the song "Ayesaba Amagwala" (The Cowards Are Scared) is unconstitutional and unlawful. The matter between Malema and the complainants was settled outside of the court in 2011.75 However, in 2018, there was a separate case which went up to the Constitutional Court of South Africa that had to do with the dismissal of employees for singing the struggle song " Umama uyajabula mangshayi ibhunu" during industrial action:

Ngizokhwela phezukwendlu kalinda I will climb up the roof.

uMama uyajabula mangishayi ibhunu My mother rejoices when I hit the Boer.

uMama uyajabula mangishayi ibhunu My mother rejoices when I hit the Boer.

The company that dismissed the employees argued among other things that the song has no place in the modern workplace, as it as racist and amounted to hate speech. However, the Constitutional Court judged in favour of the dismissed employees and ordered their reinstatement. Thus, the use of struggle songs in the current South Africa context is not without its challenges, especially considering the fears of the white minority, who were the oppressors during the colonial-apartheid era.

Returning to Ps 137, the songs contained with this psalm were likely reborn during the post-exilic period to inspire the Yehud community to deal with the continuing struggle under a new colonial power, Persia. The Yehud community in their land still viewed their situation as one of domination and oppression, as highlighted in Neh 9:36-37:

36 Behold, we are slaves this day; in the land that thou gavest to our fathers to enjoy its fruit and its good gifts, behold, we are slaves. 37And its rich yield goes to the kings whom thou hast set over us because of our sins; they have power also over our bodies and over our cattle at their pleasure, and we are in great distress. (RSV)

Therefore, the epic Ps 137 would have resonated with the anxieties and the dissatisfaction which the Yehud community had with the Persian Empire. However, the section of the epic song which deals with Edom would likely have caused discomfort, especially with those who had not gone to exile, who lived in peaceful relationship with the people surrounding them, including the Edomites, with whom they intermarried.

G CONCLUSION

From the belly of the beast, Babylon, the golah community in exile produced struggle songs which kept the memory of the land and the desire to return alive as they struggled from the position of being powerless to regain their freedom. When freedom finally came, they travelled with their songs of struggle to their land, where the struggle songs were reborn because of the continuing patterns of colonial relations under a new empire. However, it is highly likely that Psalm 137:7, the section of the epic which sought vengeance on the Edomites, would not have resonated with everyone, especially not with those who had remained in the land and had peaceful relations with the Edomites.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahn, John. "Psalm 137: Complex Communal Laments." Journal of Biblical Literature 127 (2008): 267-289. https://doi.org/10.2307/25610120. [ Links ]

Ahn, John J. Exile as Forced Migrations: A Sociological, Literary, and Theological Approach on the Displacement and Resettlement of the Southern Kingdom of Judah. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 417. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110240962. [ Links ]

Allen, Leslie C. Psalms 101-150, revised. Word Biblical Commentary 21. Waco, TX: Word, 1983. [ Links ]

Anderson, Arnold A. The Book of Psalms: 73-150. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1972. [ Links ]

Bar-Efrat, Shimon. "Love of Zion: A Literary Interpretation of Psalm 137." Pages 3-11 in Tehillah Le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic Studies in Honor of Moshe Greenberg. Edited by Mordechai Cogan, Barry L. Eichler, and Jeffery H. Tigay. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997. [ Links ]

Bassett, Carolyn, and Marlea Clarke. Post-colonial Struggles for a Democratic Southern Africa: Legacies of Liberation. London: Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315691466. [ Links ]

Becking, Bob. "Does Exile Equal Suffering? A Fresh Look at Psalm 137." Pages 181202 in Exile and Suffering: A Selection of Papers Read at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the Old Testament Society of South Africa OTWSA/OTSSA Pretoria, August 2007. Edited by Bob Becking and Dirk Human. Oudtestamentische Studiën 50. Leiden: Brill, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004171046.i-286.68. [ Links ]

Berquist, Jon L. "Psalms, Postcolonialism, and the Construction of the Self." Pages 195-202 in Approaching Yehud: New Approaches to the Study of the Persian Period. Edited by Jon L. Berquist. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2007. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil J. "Psalm 108 and the Quest for Closure to the Exile." Old Testament Essays 23 (2010): 574-596. [ Links ]

Bridgeman, Valerie. "'A Long Ways from Home': Displacement, Lament, and Singing Protest in Psalm 137." Perspectives in Religious Studies 44 (2017): 213-223. [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles Augustus, and Emilie Grace Briggs. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Volume 2. International Critical Commentary; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1906-1907. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. A Commentary on Jeremiah: Exile and Homecoming. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5396.2028. [ Links ]

______ . The Psalms and the Life of Faith. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1995. [ Links ]

Burden, Jasper J. Psalms 120-150. Skrifuitleg vir Bybelstudent en Gemeente. Kaapstad: NG Kerk-Uitgewers, 1991. [ Links ]

Byerly, Ingrid B. "Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa." Ethnomusicology 42 (1998): 1-44. https://doi.org/10.2307/852825. [ Links ]

Clark, Nancy L., and William H. Worger. South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2007. [ Links ]

Cogan, Mordechai, Barry L. Eichler, and Jeffery H. Tigay, eds. Tehillah Le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic Studies. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997. [ Links ]

Dahood, Mitchell. Psalms III: 101-150. The Anchor Bible 17A. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1970. [ Links ]

Davidson, Robert A. The Vitality of Worship: Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Delby, Teresa. "Culture and Resistance in Swaziland." Pages 4-21 in Postcolonial Struggles for a Democratic Southern Africa: Legacies of Liberation. Edited by Carolyn Bassett and Marlea Clarke. London: Routledge, 2016. [ Links ]

Dicou, Bert. Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist: The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story. Journal of the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 169. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1994. [ Links ]

Drewett, Michael. "Remembering Subversion: Resisting Censorship in Apartheid South Africa." Pages 88-93 in Shoot the Singer! Music Censorship Today. Edited by Marie Korpe. London: Zed Books, 2004. [ Links ]

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. Edited by Brent Hayes Edwards. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

Eaton, John H. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation. London: T&T Clark, 2003. [ Links ]

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. New York, NY: Grove Press, 1963. [ Links ]

Flint, Peter W. "Non-canonical Writings in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Apocrypha, Other Previously Known Writings, Pseudepigraph." Pages 80-126 in The Bible at Qumran: Text, Shape, and Interpretation. Edited by Peter W. Flint. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Fohrer, Georg. Psalmen. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1993. [ Links ]

Fokkelman, Jan. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis, Volume II: 85 Psalms and Job 4-14. Studia Semitica Neerlandica 41. Assen: Van Gorcum, 2000. [ Links ]

Freedman, David N. "The Structure of Psalm 137." Pages 187-205 in Near Eastern Studies in Honor of William Foxwell Albright. Edited by Hans Goedicke; Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1971. [ Links ]

Friedman, Jonathan C. The Routledge History of Social Protest in Popular Music. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203124888. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard. Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations. Forms of Old Testament Literature 15. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Gilbert, Shirli. "Singing against Apartheid: ANC Cultural Groups and the International Anti-Apartheid Struggle." Journal of Southern African Studies 33 (2007): 421441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070701292848. [ Links ]

Gillingham, Susan. "The Exodus Tradition and Israelite Psalmody." Scottish Journal of Theology 52 (1999): 19-46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0036930600053473. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. Psalms Volume 3: Psalms 90-150. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008. [ Links ]

Gunner, Liz. "Jacob Zuma, the Social Body and the Unruly Power of Song." African Affairs 108 (2008): 27-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adn064. [ Links ]

Gunner, Liz. "Song, Identity and the State: Julius Malema's Dubul' ibhunu Song as Catalyst." Journal of African Cultural Studies 27/3 (2015): 326-341, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2015.1035701. [ Links ]

Hartberger, Birgit. An den Wassern von Babylon. Psalm 137 auf dem Hintergrund von Jeremia 51, der biblischen Edom-Traditionen und babylonischer Originalquellen. Bonner Biblische Beiträge 63. Frankfurt am Main: Hanstein, 1986. [ Links ]

Hays, Christopher B. "How Shall We Sing? Psalm 137 in Historical and Canonical Context." Horizons in Biblical Theology 27 (2005): 35-55. https://doi.org/10.1163/187122005X00095. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101150. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Irudayaraj, Dominic S. Violence, Otherness and Identity in Isaiah 63:1-6: The Trampling One Coming from Edom. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies 633. London: T&T Clark, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgy014. [ Links ]

Joerstad, Mari. "Sing Us the Songs of Zion: Land, Culture, and Resistance in Psalm 137, 12 Years a Slave, and Cedar Man." Horizons in Biblical Theology 40 (2018): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1163/18712207-12341363. [ Links ]

Jolaosho, Tayo. "Anti-Apartheid Freedom Songs Then and Now." Folksway Magazine (2014). Online: https://folkways.si.edu/magazine-spring-2014-anti-apartheid-freedom-songs-then-and-now/south-africa/music/article/smithsonian . [ Links ]

Koole, Jan L. Isaiah III: 56-66. Historical Commentary of the Old Testament. Leuven: Peeters, 2001. [ Links ]

Korpe, Marie. Shoot the Singer! Music Censorship Today. London: Zed Books, 2004. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalms 60-150. A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1989. [ Links ]

Kruger, Paul A. "Women and War Brutalities in the Minor Prophets: The Case of Rape." Old Testament Essays 27 (2014): 147-176. [ Links ]

Landau, Paul S. "The ANC, MK, and 'The Turn to Violence' (1960-1962)." South African Historical Journal 64 (2012): 538-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02582473.2012.660785. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. "On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept." Cultural Studies 21 (2007): 240-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548. [ Links ]

Malisa, Mark, and Nandipha Malange. "Songs for Freedom: Music and the Struggle against Apartheid." Pages 304-318 in The Routledge History of Social Protest in Popular Music. Edited by Jonathan C. Friedman. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013. [ Links ]

Maré, Leonard P. "Psalm 137: Exile - Not the Time for Singing the Lord's Song." Old Testament Essays 23 (2010): 116-128. [ Links ]

Mays, James Luther. Psalms. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1994. [ Links ]

McCann, Clinton J. "The Book of Psalms." Pages 639-1280 in The New Interpreter's Bible, Volume 4. Edited by Leander E. Keck. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996. [ Links ]

Mendisi, Martha D. "Political Songs." MA Dissertation. Johannesburg: Rand Afrikaans University, 1998. [ Links ]

Motyer, J. Alec. Psalms. New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition. 4th ed. Leicester: InterVarsity, 1994. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, J. The Decolonial Mandela: Peace, Justice and the Politics of Life. New York, NY: Berghahn, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvgs0c16. [ Links ]

Nkoala, Sisanda Mcimeli. "Songs That Shaped the Struggle : A Rhetorical Analysis of South African Struggle Songs." African Yearbook of Rhetoric 4 (2013): 51-61. [ Links ]

Pongweni, Alec J. C. Songs That Won the Liberation War. Harare: College Press, 1982. [ Links ]

Pring-Mill, Robert. "The Roles of Revolutionary Song - a Nicaraguan Assessment." Popular Music 6 (1987): 179-189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143000005973. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. "Psalm 137: Ecclesia Pressa, Ecclesia Triumphans." Pages 281293 in Die Lof van My God solank ek lewe: Verklaring van 'n Aantal Psalms deur Willem S Prinsloo. Edited by Wim Beuken et al. Irene: Medpharm, 2000. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. Van Kateder Tot Kansel. 'n Eksegetiese Verkenning van Enkele Psalms. Pretoria: NG Kerk-Uitgewers, 1998. [ Links ]

Reed, Thomas V. The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Present. 2nd ed. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvb1hrcf. [ Links ]

Reynolds, Kent A. Torah as Teacher: The Exemplary Torah Student in Psalm 119. Supplement to Vetus Testament 137. Leiden: Brill, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004182684.i-249. [ Links ]

Robert, A. "Littéraires (Genres)." Pages 405-21 in Dictionnaire de la Bible, Supplement, vol. 5. Edited by L. Pirot et al. Paris: Librairie Letouzey et Ané [ Links ].

Schumann, Anne. "The Beat that Beat Apartheid: The Role of Music in the Resistance against Apartheid in South Africa." Stichproben: Wiener Zeitschrift für Kritische Afrikastudien / Vienna Journal of African Studies 14 (2008): 17-39. [ Links ]

Shultziner, Doron. Struggling for Recognition: The Psychological Impetus for Democratic Progress. New York, NY: Continuum, 2010. [ Links ]

Simango, Daniel. "A Comprehensive Reading of Psalm 137." Old Testament Essays 31 (2018): 217-242. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2018/v31n1a11. [ Links ]

Stern, David. "An Anthology in Jewish Literature: An Introduction." Pages 3-11 in The Anthology in Jewish Literature. Edited by David Stern. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. [ Links ]

Stowe, David W. Song of Exile: The Enduring Mystery of Psalm 137. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190466831.001.0001. [ Links ]

Tournay, Raymond Jacques. "Psaumes 57, 60 et 108: Analyse et Interpretation." Revue Biblique 96 (1989): 5-26. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem A. Psalms. The Expositor's Bible Commentary 5. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991. [ Links ]

Vershbow, Michela E. "The Sounds of Resistance: The Role of Music in South Africa's Anti-Apartheid Movement." Inquiries 2 (2010), online: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/265/the-sounds-of-resistance-the-role-of-music-in-south-africas-anti-apartheid-movement. Accessed 25 March 2019. [ Links ]

Weiser, Arthur. The Psalms. A Commentary. Translated by Herbert Hartwell. Old Testament Library. Philadelphia; PA: Westminster Press, 1962. [ Links ]

Willgren, David. The Formation of the 'Book' of Psalms: Reconsidering the Transmission and Canonization of Psalmody in Light of Material Culture and the Poetics of Anthologies. FAT 2/88. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1628/978-3-16-154937-3. [ Links ]

Whybray, Roger Norman. Isaiah 40-66. New Century Bible. London: Oliphants, 1975; reprint, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1981. [ Links ]

Whybray, Roger Norman. Isaiah 40-66. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1975. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich. "Der Jüdaische Psalter - ein anti-imperiales Buch?" Pages 95-105 in Religion und Gesellschaft: Studien zu ihrer Wechselbeziehung in den Kulturen des Antiken Vorderen Orients. Edited by Rainer Albertz. Veröffentlichungen des Arbeitskreises zur Erforschung der Religions- und Kulturgeschichte des Antiken Vorderen Orients 1 / Alter Orient und Altes Testament 248. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 1997. [ Links ]

Article Submitted: submitted: 2019/03/04

Peer reviewed: 2019/05/18

Accepted: 2019/07/16

1 Bob Becking, "Does Exile Equal Suffering? A Fresh Look at Psalm 137," in Exile and Suffering: A Selection of Papers Read at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the Old Testament Society of South Africa OTWSA/OTSSA Pretoria, August 2007 (ed. Bob Becking and Dirk Human; OTS 50; Leiden: Brill, 2009), 181-202.

2 Jon L. Berquist, "Psalms, Postcolonialism, and the Construction of the Self," in Approaching Yehud: New Approaches to the Study of the Persian Period (Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2007), 195-202, 196.

3 Erich Zenger, "Der jüdische Psalter - ein anti-imperiales Buch?" in Religion und Gesellschaft: Studien zu ihrer Wechselbeziehung in den Kulturen des Antiken Vorderen Orients (ed. Rainer Albertz; AZERKAVO 1/AOAT 248; Münster: Ugarit, 1997), 95105.

4 Arnold B. Anderson, The Book of Psalms. Vol. 2 (NCB; London: Butler & Tanner, 1972), 892-897; Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 60-150: A Commentary (CC; Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1989); Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations (FOTL 15; Grand Rapids; MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 501; Leonard P. Maré, "Psalm 137: Not the Time for Singing the Lord's Song," OTE 23 (2010): 116-128 (118); Daniel Simango, "A Comprehensive Reading of Psalm 137," OTE 31 (2018): 217-242 (223). Others regard the Psalm as having a mixed genre (Mischgattung) which brings together elements such as lament, prayer, song, curse/vengeance (Jasper J. Burden, Psalms 120-150 [SBG; Kaapstad: NG Kerk-Uitgewers, 1991]; Ulrich Kellerman, "Psalm 137," ZAW 90 [1978]), 53.

5 This in concurrence with Brueggemann's observation that psalms of lamentation present a religious problem, which cannot be simply addressed religiously "[r]ather, the religious speech always carries with it a surplus of political, economic and social freight" (Walter Brueggemann, The Psalms and the Life of Faith [Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1995], 106).

6 Robert Pring-Mill, "The Roles of Revolutionary Song - a Nicaraguan Assessment in Popular Music," Popular Music 6 (1987): 179-189 (179). See also Sisanda M. Nkoala, "Songs that Shaped the Struggle: A Rhetorical Analysis of South African Struggle Songs," African Yearbook of Rhetoric 4 (2013): 51-61.

7 Anne Schumann, "The Beat that Beat Apartheid: The Role of Music in the Resistance against Apartheid in South Africa," Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien/Vienna Journal of African Studies 14 (2008): 17-39.

8 Thomas V. Reed, The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Present (2 ed.; Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2019), 28.

9 Songs of struggle may be classified in various ways. See, for example, Shirli Gilbert, "Singing against Apartheid: ANC Cultural Groups and the International AntiApartheid Struggle," Journal of Southern African Studies 33 (2007): 421-441. For a comprehensive, although not exhaustive, list of struggle songs, see Martha Dolly Mendisi, "Political Songs" (MA Dissertation: Rand Afrikaans University, 1998), 71100.

10 Examples include "Ndod' emnyam," "Wathint'abafazi," "Meadowlands," and "Siyaya ePitoli."

11 Examples include "Hamba Kahle Mkhonto," "Sabashiya Abazali," "Umshini wami," "Dubula iBhunu" or "Ayasaba Amaqwala," "Kulonyaka sizimisele," and " Masibabulaleni."

12 Examples include "Nkosi Sikelele Afurika," "Senzenina," "Thina Sizwe," "Se a lela setjhaba," and "Saphela isizwe."

13 Examples include "Oliver Tambo Thetha noBotha," "Sikhokhele Tambo," and "Ha ho ya tswanang le yena."

14 Doron Shultziner, Struggling for Recognition: The Psychological Impetus for Democratic Progress (New York, NY: Continuum, 2010), 114.

15 As Stowe notes, "Unique among the Hebrew Psalms, Psalm 137 transpires in a specific geographic location at a particular time. The setting is Mesopotamia on the banks of the Euphrates River, or more likely one of the irrigation canals connected with the Euphrates" (David W. Stowe, Song of Exile: The Enduring Mystery of Psalm 137 [New York, NY: Oxford University Press], 2016).

16 See Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 51-150 (trans. Linda M. Maloney; Hermeneia; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, [2011]), 513-514; John Goldingay, Psalms Volume 3: Psalms 90-150 (BCOTWP; Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 600-601; Mitchell Dahood, Psalms III: 101-150 (AB 17A; Garden City: Doubleday, 1970 [Yale University Press, 2007]), 269; Leslie C. Allen, Psalm 101-150 (WBC 21; Waco, TX: Word, 1983), 239; For further discussion, see Birgit Hartberger, An den Wassern von Babylon. Psalm 137 auf dem Hintergrund von Jeremia 51, der biblischen Edom-Traditionen und babylonischer Originalquellen (BBB 63; Frankfurt am Main: Hanstein, 1986), 4-7.

17 A number of scholars do regard Ps 137 as having its origin in the Babylonian period; cf. Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 501; Georg Fohrer, Psalmen (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1993), 133; Arthur Weiser, The Psalms: A Commentary (trans. Herbert Hartwell; OTL; Philadelphia, PA: Westminster, 1962), 794.

18 David Willgren, The Formation of the 'Book' of Psalms: Reconsidering the Transmission and Canonization of Psalmody in Light of Material Culture and the Poetics of Anthologies (FAT 2/88; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016), 25. Willgren's definition is informed by the way that Ferry and also Griffith define anthology. Ferry describes an anthology as follows: "What is recognizable as an anthology is an assemblage of pieces (usually short): written by more than one or two authors; gathered and chosen to be together in a book by someone who did not write what it contains, or not all; arranged and presented by the complier according to any number of principles except sing authorship, which the nature of the contents rules out. These predications for admission to this special category of book distinguish an anthology from a body of poems together by their author, and, in a lesser way, from a collection of a single poet's work presented by an editor. . . Or to state the distinction simply another way, in a collection made by the author of the poems in it there is no other person who controlling presence is acknowledged and whose decisions mediate between them poems and the reader." (Anne Ferry, Tradition and the Individual Poem: An Inquiry into Anthologies [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001], 31). Griffiths speaks of an anthology as "a work all (or almost all) of whose words are taken from another work or works; it contains a number (typically quite a large number) of extracts or excepts, each of which has been taken verbatim (or almost so) from some other work; and it uses some device to mark the boundaries of these excerpts. Any work that meets these conditions is an anthology" (Paul J. Griffiths, Religious Reading: The Place of Reading in the Practice of Religion [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999], 97).

19 Gordon J. Wenham, Psalms as Torah: Reading Biblical Song Ethically (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012), 41.

20 A Robert, "Littéraires (Genres)" in Dictionnaire de la Bible, Supplément (ed. L. Pirot et al.; Paris: Librairie Letouzey et Ané), 5:405-21.

21 James L. Mays, Psalms (IBC; Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1994), 233.

22 See J. Clinton McCann Jr., "The Book of Psalms," in The New Interpreters Bible, Vol. IV(ed. Leander E. Keck; Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996), 639-1280, 955.

23 Phil J. Botha, "Psalm 108 and the Quest for Closure to the Exile," OTE 23/3 (2010): 574-575. See also Raymond J. Tournay, "Psaumes 57, 60 et 108. Analyse et Interpretation," RB 96 (1989): 5-26; Kent A. Reynolds, Torah as Teacher: The Exemplary Torah Student in Psalm 119 (VTSup 137; Leiden: Brill, 2010), 28-29.

24 Peter W. Flint, "Non-canonical Writings in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Apocrypha, Other Previously Known Writings, Pseudepigraph" in The Bible at Qumran: Text, Shape, and Interpretation (ed. Peter W. Flint; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 94.

25 David Stern, "An Anthology in Jewish Literature: An Introduction" in The Anthology in Jewish Literature (ed. David Stern; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 3-11, 7.

26 Stern, "An Anthology," 7.

27 Kellerman, "Psalm 137," 43-58; Burden, Psalms 120-150, 122; Willem S. Prinsloo, "Psalm 137: Ecclesia Pressa, Ecclesia Triumphans" in Die Lof van My God Solank Ek Lewe: Verklaring van 'n Aantal Psalms deur Willem S Prinsloo (ed. Wim Beuken et al.; Irene: Medpharm, 2000), 281-293 (285-286).

28 Charles A. Briggs and Emilie G. Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms (ICC; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1906-1907), 2:484; Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 240; Willem S. Prinsloo, Van Kateder tot Kansel. 'n Eksegetiese Verkenning van Enkele Psalms (Pretoria: N.G. Kerk-Uitgewers, 1988), 117; Willem A. VanGemeren, Psalms (EBC 5; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991), 826; James L. Mays, Psalms (IBC; Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1994), 422; J. Alec Motyer, Psalms (New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition; 4 ed.; Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1994), 577; J. Clinton McCann Jr., "The Book of Psalms," in The New Interpreters Bible, Vol. IV (ed. Leander E. Keck; Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996), 639-1280, 1227; Shimon Bar-Efrat, "Love of Zion: A Literary Interpretation of Psalm 137," in Tehillah le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic Studies in Honor of Moshe Greenberg (ed. Mordechai Cogan, Barry L. Eichler, and Jeffrey H. Tigay; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 3-11; Robert. A Davidson, The Vitality of Worship: Commentary on the Book of Psalms (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 439-441; Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations (FOTL 15; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 390; John H. Eaton, The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary - with an Introduction and New Translation (London: T&T Clark, 2003), 454; Maré, "Psalm 137: Exile," 117.

29 Other examples of anthological psalms are Pss 31; 33; 37 and 119. See Phil J. Botha, "Psalm 108 and the Quest for Closure to the Exile," OTE 23 (2010): 574-596; Raymond J. Tournay, "Psaumes 57, 60 et 108. Analyse et Interpretation," RB 96 (1989): 5-26. Reynolds, Torah as Teacher, 28-29.

30 See Simango, "A Comprehensive Reading of Psalm 137," 223.

31 Schumann, "The Beat that Beat Apartheid," 19-20. See also Michael Drewett, "Remembering Subversion: Resisting Censorship in Apartheid South Africa," in Shoot the Singer! Music Censorship Today (ed. Marie Korpe; London: Zed Books, 2004), 8893.

32 Teresa Delby, "Culture and Resistance in Swaziland," in Postcolonial Struggles for a Democratic Southern Africa: Legacies of Liberation (ed. Carolyn Bassett and Marlea Clarke; London: Routledge, 2016), 4-21, 14.

33 Mark Malisa and Nandipha Malange, "Songs for Freedom: Music and the Struggle against Apartheid" in The Routledge History of Social Protest in Popular Music (ed. Jonathan C. Friedman; New York, NY: Routledge, 2013), 304-318 (304).

34 See Ingrid B. Byerly, "Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa," Ethnomusicology 42 (1998): 1-44 (14). The lekkerliedjies (nice songs) were songs which were "musically and lyrically... light and unchallenging; a sort of easy-listening. Lyrics centered around flora, fauna, and geographical locations to avoid controversial issues" (see Byerly, "Mirror," 38).

35 Byerly, "Mirror," 26-28.

36 Walter Brueggemann, A Commentary on Jeremiah: Exile and Homecoming (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 344.

37 Compare with Deut 8:7; 10:7; Ps 1:3 and Jer 31:9.

38 Christopher B. Hays, "How Shall We Sing? Psalm 137 in Historical and Canonical Context," HBT 27 (2005): 35-55 (42).

39 Bar-Efrat, "Love of Zion," 5.

40 John J. Ahn, Exile as Forced Migrations: A Sociological, Literary, and Theological Approach on the Displacement and Resettlement of the Southern Kingdom of Judah (BZAW 417; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010), 79.

41 Ahn, Exile as Forced Migrations, 87.

42 Hays, "How Shall We Sing?" 46.

43 The movie reflects on slavery in the USA through the life of Solomon Northup, who while a free man was kidnapped and sold into slavery.

44 Mari Joerstad, "Sing Us the Songs of Zion: Land, Culture, and Resistance in Psalm 137, 12 Years a Slave, and Cedar Man," HBT 40 (2018):1-16 (9).

45 As Fokkelman notes: "[T]he strophe employs compound sentences and three times the conditional conjunction. The syntax is a chiasm: one colon for the first conditional clause, plus one colon for the short main clause = v. 5ab; this is followed by a slightly longer main clause in v. 6a plus three cola with a short and a long conditional clause. Four cola rhyme on -I, the other two have the name Jerusalem as epiphor" (Jan P. Fokkelman, Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis, Volume II: 85 Psalms and Job 4-14 [SSN 41; Assen: Van Gorcum, 2000], 301).

46 Walter Brueggemann, "Psalms and the Life of Faith: A Suggested Typology of Function," JSOT 17 (1980): 3-32; reprinted in Walter Brueggemann, The Psalms and the Life of Faith (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995), 3-32.

47 David N. Freedman, "The Structure of Psalm 137," in Near Eastern Studies in Honor of William Foxwell Albright (ed. Hans Goedicke; Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1971), 187-205.

48 W. E. B. du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (ed. Brent Hayes Edwards; Oxford World's Classics; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). This book was originally published in 1903.

49 Ibid., 169.

50 Ibid., 194.

51 Susan Gillingham, "The Exodus Tradition and Israelite Psalmody," SJT 52 (1999): 19-46 (43). In Psalm 135:8-12, the exodus motif is brought to the fore through reference to the death of the Egyptians' firstborn, both human and animal, to signs and wonders done in Egypt, to the defeat of kings such as Sihon king of Amorites and Og king of Bashan, as well as of other kings in the land of Canaan not mentioned by name, and to the giving of the land to the people of Israel. In Ps 136:10-24, the same exodus motifs are referred to with slight variation. For Gillingham, the exodus motif as found in parallel psalms such as Pss 105-106 and 135-136 indicates an inversion by the post-exilic Temple community, who sought to assure themselves as the true elect people among the different groups and parties in Judah and in the north (Gillingham, "The Exodus Tradition," 44).

52 John Ahn, "Psalm 137: Complex Communal Laments," JBL 127 (2008): 267-289 (285).

53 Hays, "How Shall We Sing?" 49.

54 See also Paul A. Kruger, "Women and War Brutalities in the Minor Prophets: The Case of Rape," OTE 27 (2014): 147-176.

55 These non-ethical aspects of war are not only reflected on in the Hebrew Bible but they were part of other ancient Near Eastern cultures as well.

56 Valerie Bridgeman, "'A Long Ways from Home': Displacement, Lament, and Singing Protest in Psalm 137," PRS 44 (2017): 213-223 (216).

57 Ahn, "Psalm 137: Complex Communal Laments," 288.

58 See also Bridgeman, "A Long Ways from Home," 221-222.

59 Hays, "How Shall We Sing?" 50.

60 Hays, "How Shall We Sing?" 50. See also Ahn, "Psalm 137: Complex Communal Laments," 288.

61 MK is short for uMkhonto weSizwe.

62 Paul S. Landau, "The ANC, MK, and 'The Turn to Violence' (1960-1962)," South African Historical Journal 64 (2012): 538-563; see also Michela E. Vershbow, "The Sounds of Resistance: The Role of Music in South Africa's Anti-Apartheid Movement," Inquiries 2 (2010), online: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/265/the-sounds-of-resistance-the-role-of-music-in-south-africas-anti-apartheid-movement. Accessed 25 March 2019.

63 As quoted from Nancy L. Clark and William H. Worger, South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid (Harlow: Pearson Education, 2007), 150.

64 Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York, NY: Grove Press, 1963), 31.

65 See Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, The Decolonial Mandela: Peace, Justice and the Politics of Life (New York, NY: Berghahn, 2016), 86.

66 Nelson Maldonado-Torres, "On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of the Concept," Cultural Studies 21 (2007): 240-270 (255).

67 Ibid., 263.

68 See Dominic S. Irudayaraj, Violence, Otherness and Identity in Isaiah 63:1-6: The Trampling One Coming from Edom (LHBOTS 633; London: T&T Clark, 2017), 61.

69 See Roger Norman Whybray, Isaiah 40-66 (NCB; London: Oliphants, 1975; reprint, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1981), 253; Jan L. Koole, Isaiah III: 56-66 (HCOT; Leuven: Peeters, 2001), 331.

70 See Bert Dicou, Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist: The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story (JSOTSup 169; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1994), 186.

71 Liz Gunner, "Jacob Zuma, the Social Body and the Unruly Power of Song," African Affairs 108 (2009): 27-48 (36).

72 I am indebted here to Gunner's ideas on songs and their publics. See Gunner, "Jacob Zuma," 36.

73 See Alec J. C. Pongweni, Songs that Won the Liberation War (Harare: The College Press, 1982).

74 Tayo Jolaosho, "Anti-Apartheid Freedom Songs Then and Now," Folksway Magazine, Spring (2014). Online: https://folkways-media.si.edu/docs/folkways/magazine/2014_spring/Anti_Apartheid_Freedom_Songs_Jolaosho.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2019.

75 For more details surrounding the case of "Dubula ibhunu," see, Liz Gunner, "Song, Identity and the State: Julius Malema's Dubul' ibhunu Song as Catalyst," Journal of African Cultural Studies 27/3 (2015): 326-341, DOI: 10.1080/13696815.2015.1035701.

Prof Hulisani Ramantswana, University of South Africa, Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, P.O. Box 392, UNISA, 0003; Email: ramanh@unisa.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6629-9194.