Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.32 n.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n2a8

ARTICLES

"I Love Yahweh and I Believe in Him - Therefore I Shall Proclaim His Name": How Psalm 116 Integrated and Reinterpreted Its Constituent Parts1

Henk Potgieter

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

In studies on the biblical Psalms it is customary to ask why and for what purpose these poems came into existence. The present study departs from the observation that Psalm 116 can be regarded as an anthology which incorporated material from various other sources in the Hebrew Bible. The study aims to investigate the relationship between the various contributing constituents to the final form of Psalm 116. Therefore, it is necessary to add another question to those that are usually posed in studies on the Psalter, namely the "how?" question: How did the author/editors(s) use and incorporate different sources to come to the Psalm 116 as we know it in the Masoretic Text? The study argues that Psalm 116 is a prime example of the tendency in late post-exilic Psalmography to compile new poems by using existing material from the Hebrew Bible. Other examples of this style of writing are found inter alia in Pss 1; 19; 25; 34; 37; 86; and 119. This has been described in the past as an "anthological" style of composition. Very often in these psalms one can also detect a marked attempt to produce a symmetric pattern and also a marked influence from wisdom. All these tendencies are apparent in Ps 116.

Keywords: Psalm 116, anthology, reuse and reinterpretation, composition of individual psalms.

A INTRODUCTION

Erich Zenger,2 in his preface to the book Ritual und Poesie, commenced with the following questions: "Where and for what purpose did the biblical Psalms come into existence?"3 These two questions are the guiding principles in most of the studies on the Psalms. It is also true of the studies which have been done on Psalm 116. A prime example of this point of departure is Bernd Janowski when he states the following:4 "Ps 116, a typical thanksgiving song of an individual -with announcement of the thanksgiving, report on deliverance and (a summons to) a vow of praise - has its place in the temple cult and was recited there 'before his (i.e., Yahweh's) whole people' (vv. 14b, 18b) within the context of a tôdãh-celebration (vv. 13-19)".5 This sentiment is also echoed by Beat Weber when he says the following:6 "in my view, the psalm is to be considered from the perspective of its conclusion as an individual song of thanksgiving (Toda): The divine display of power corresponds to a public confession."7 Weber also takes other considerations into account. One of these considerations is expressed as follows: "Ps 116 is, however, no 'straightforward' tôdãh-psalm, but, on the grounds of the parallel beginnings of the first and third sections (1a, 10a) as well as the refrain-like elements (4a, 13b, 17b as well as 14, 18-19) it attests to a strong poetic modulation."8

My own approach is from a different angle. In earlier studies on the book of Jonah it became clear to me that the psalm of Jonah in Jon 2:3-10 is an anthology of various quotations from the Psalter, including quotations from Psalm 116.9 By scrutinising Ps 116 and the literature around it, it became clear that Ps 116 is also an anthology which incorporated material from various other sources. In this study, it is my intention to investigate the relationship between the various contributing constituents to the final form of Ps 116. Therefore, it is necessary to add another question to those that Zenger posed: The how question.

How did the author/editors(s) use and incorporate different sources to come to the Ps 116 as we know it in the Masoretic Text?

Broadly speaking, my analysis concerns an intertextual reading of Ps 116. Intertextual analysis has become a major field of interest in biblical studies.10 A number of other texts in the Hebrew Bible are quoted or alluded to in Ps 116, leading me to suspect that the poem is an anthology of already known poetic compositions. Stating that the poem is an anthology, does not imply, as HansJoachim Kraus maintains, that Ps 116 is "a fragmentlike collection".11 The aim of the study is to indicate that Ps 116 can indeed be regarded as an anthology of different texts that have been utilised in its composition. However, the new composition is a new, unique poem.

B PSALM 116: TEXT AND TRANSLATION

In Table 1, a stichometric analysis of Ps 116 together with a translation is given.12The shaded areas represent the text which shows resemblances with the sources in the discussion below.

C THE STRUCTURE OF PSALM 116

Before we can attend to the different sources which contributed to the final form of the poem, we have to get a feeling for how the psalm presents itself - what the structure of the poem looks like. In Table 2, I present an adapted version of Ps 116's stichometric form. The representation serves to demonstrate the symmetry in the structure of the psalm. According to the segmentation the psalm is divided in two, more or less, equal halves or sections, vv. 1-9 and 10-19 consisting of 20 and 21 cola respectively. Except for the fact that each section consists of two stanzas and four strophes, there are numerous links that connect the stanzas and strophes of the two halves. 13

Pieter van der Lugt in his discussion of the structure of Ps 116, gives a detailed and well documented description of the segmentation which is reflected in the table above.14 In my version of the segmentation, I only differ from him by including v. 8c (Stanza II, Strophe D) which he omitted because he regards it as a gloss.15 In doing so, he follows the recommendation of the text critical apparatus of BHS on Ps 56:14, which has no textual evidence except for a reference to Ps 116. I (like van der Lugt) also omitted the Hallelujah at the end of the v. 19 because I regard it as the superscript of the Ps 117.16

D THE "SOURCES" OF PSALM 116

When Ps 116 is scrutinised there seems to be resemblances with Pss 18:1, 4-7; 56:13-14, as well as a formula from Exod 33:19 and 34:6.17 In addition, extensive use is made of material from the book of Jonah. There is not only a resemblance between parts of Ps 116 and Jon 2:3-10, but also between Ps 116 and the other prayer of Jonah in Jon 4:2-3, as well as other formulae.

In the following sections, the blocks of material or individual words borrowed in order to compose Ps 116 are discussed. The direction of borrowing will not be argued in each case, but it can be stated that the general anthological character of Ps 116 points in the direction of it's being the later composition which made use of the other contexts. In a substantial number of instances, it can be pointed out that the donor text was adapted or abbreviated for use in Ps 116, while the borrowed phrases and words make good sense in the more complete form in the original context. The poet who created Ps 116 was, however, a masterful artist. It requires considerable skill to compose a new text by using existing material and still maintain excellent poetic standards.

1 Psalm 116:1-3 and Psalm 18:4-7

It is obvious that the source for the first three verses of Ps 116 is Ps 18:4-7. More or less half of the words and cola in Ps 18:4-7 were utilised in Ps 116, although in a different order. Noteworthy is the fact that the material from Ps 18:4-7 is incorporated as a unit in the first stanza of Ps 116.

Three elements are described in vv. 1-3. First, in two parallel cola in vv. 1 and 2, the fact that Yahweh listens to the supplicant is expressed. The resemblance is clear and little deviation from Ps 18 occurs. Second, the supplicant calls to Yahweh, where the specific use of Nli?^ as a Leitmotiv for the psalm as a whole, is very important. Finally, the description of the distress, which is rather comprehensive in Ps 18, is greatly reduced in Ps 116. The poet used three successive verses from Ps 18, namely vv. 5, 6 and 7 (9 cola) to create a tricolon in Ps 116:3, which describes the supplicant's distress. The first of these colas is a verbatim repetition of Ps 18:5a, while the second one's resemblance to Ps 18:6a is only superficial (שאול and the suffix first person singular are used). The last colon displays a resemblance to Ps 18:7a, but it also reflects the poetic intent of the poet who endeavoured to incorporate repetition of word stems and sounds in the three cola of v. 3 (cf. the occurrence of the sounds e-a-uni and "מ־).

There is, actually, a fourth point of resemblance which is not immediately apparent when the two psalms are compared. Both of them commence with a declaration of love. The word אֶרְׁ חמְׁךָ in Ps 18:2 is a synonym for the word 'א הבְׁתִי in Ps 116:1. The fact that the declaration of love does not occur in the 2 Sam 22 version of Ps 18, is an indication that Ps 18:1, 4-7 is indeed the real source for Strophes A and B in Ps 116.18

What is clear from the comparison is that the resemblances are definitely not accidental; neither are they offhand but, as Weber so aptly puts it "poetisch stark moduliert."19 This is a purposeful new creation where material from another source (be it from a shared repository) is used and shaped into a new and meaningful poem. In this new poem, Ps 116, material that originated from or is shared with Ps 18 is used to create a Stanza with two strophes, A and B. In strophe A, the poet/supplicant expresses his confidence that Yahweh heard his supplication and in strophe B, he describes his dire circumstances from where his call came to Yahweh to save him. Not only are these strophes well-rounded thought-units with a central theme, but they are also connected to each other to form a Stanza. On formal grounds the two strophes form an inclusio with the repetition of Jahweh in 1a and again at the end of 4b, and the recurrence of אֶקְְׁׁ ראin v. 2b, as well as in 4a. In addition to the formal function of אֶקְְׁׁ רא, it also introduces the theme of the psalm and that is: "to proclaim the name of Yahweh".

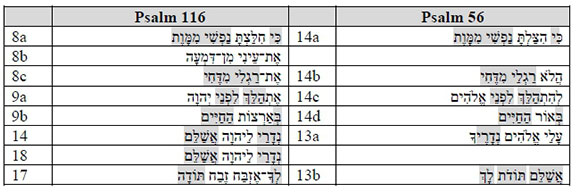

2 Psalm 116 and Psalm 56:13-14

Although the elements of Ps 56:13-14 are, with minor variations, represented in toto in Ps 116, the two texts differ regarding the function of the elements. In its new environment at the end of the first section in Ps 116 (Strophe D) the words contained in Ps 56:14 now describes the saving act by Yahweh from death with the result that the supplicant can walk before Yahweh and that he remains in the "land of the living."

Four changes are affected with the incorporation of this verse into Ps 116. To begin with, there is the replacement of the verb הִ צלְׁ ת (hif'il perfect 2nd person masculine singular of נצל) by a similar sounding verb, חִ לצְׁ ת(pi 'el perfect 2ndperson masculine singular of חלץ). The two stems have meanings which overlap semantically in certain contexts: נצלin the hif'il is to "pull out" or "rescue"; חלץin the pi'el is to "pull out," but also to "deliver" or "save." A second important change occurs when the word for God, אֱלֹהִים, which is the dominant name in Ps 56, is changed to יְׁה וה, which is dominant name used in Ps 116. In the third instance the phrase בְׁאוֹר ה חיִים "in the light of the living" in Ps 56:14d is rephrased into בְׁ ארְׁצוֹת ה ח יִים "in the lands of the living" in Ps 116:9b. This is an important change in the light of the spatial orientation of Ps 116 as part of the Egyptian Hallel. Although both expressions "in the light of the living" and "in the lands of the living" means to be alive, the first denotes a state while the latter has a more spatial connotation.20 The final change, when Ps 56:14a and b is incorporated into Ps 116, is the addition of the phrase "my eyes from tears" to form a tricolon in Ps 116:8abc describing the supplicant's total salvation from death.

A major difference in the placement and functioning of the two verses from Ps 56 in its new setting, is evident. While v. 14 is incorporated as a unit in the first section of Ps 116 (i.e., vv. 1-9) to demonstrate the saving act of Yahweh, v. 13 on the other hand is split up in two halves to be used as part of a refrain in the second section (vv. 10-19) of Ps 116.

The first colon ע לי אֱלֹהִים נְׁ דרֶיךָ ("it is my duty to perform your vows, o God") exhibits three changes when it is applied as part of the refrain in Ps 116. First of all, the address to אֱלֹהִים is changed to an address to יְׁה וה which seems to be the preferred name of God (14 times) in Ps 116. In the second place, the suffix second person masculine singular is changed into a first person singular so that "your vows" becomes "my vows." A last change is to be found in the converting of the nominal sentence in the first colon ("on me are your vows, o God") into a verbal sentence by using the verb אשלם ("I will pay") of the second colon with the first colon and providing the second colon with a new verb (אזבח "I will offer"). The influence from, or resemblance with Jon 2:10 is also evident regarding the use of the verbs אשלם and אזבח.

3 Psalm 116 and Jonah 2:3-10

Unlike the two previous cases where material from Pss 18 and 56 were typically incorporated as a unit or block into Ps 116, it is not the case with the material from the psalm of Jonah in Jon 2:2-10, except for Jon 2:10 which was incorporated into Ps 116:17-18. Incidentally, this is the only resemblance which was recognised in the past by scholars and commentaries. The resemblance is, however, far greater than the suggested verses, but it is rather to be found in a general sense and not so much in specific phrases. Many words are similar, and some of them are restricted to the contexts of Pss 18; 56; 116 and the Jonah psalm, but there are significant differences in their combinations and usage. Perhaps the reason for this is the very specific situation of distress described in the psalm in Jonah, while the distress in Ps 116 is sketched more in general terms. However, this being taken into consideration, the resemblance is so overwhelming that one has to consider a common source, be it the same author(s)/editor(s) or the use of the same repository.

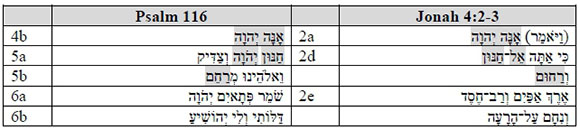

4 Psalm 116 and Jonah 4:2-3

Both Ps 116:4 and Jon 4:2, with the opening words א נה יְׁה וה share certain characteristics with six other א נה prayers in the Old Testament.21 But it is in the confession part of the prayer where some significant editorial changes took place.

This confession, or Gnadenformel as it is also known, occurs several times in the Old Testament.22 It consists mostly of five elements of which the first two, אֵל־ חנוּן וְׁ רחוּם ("a merciful and compassionate God"), form a word pair. Sometimes the order of these two adjectives is changed, but they remain a pair. The wisdom editors, however, broke the pair when they incorporated them into Ps 116 by inserting the wisdom term צדִיק 23 Because of this insertion, the adjective וְׁ רחוּם] is also changed into מְׁ רחֵם, a pi 'el participle with a new subject, וֵאלֹהֵינוּ. V. 6 is also an addition from the same editorial circle. Instead of the expected וְׁ רב־חֶסֶד as a description of Yahweh, he is now defined in terms of his relationship with the implied supplicant. This is done by describing him as the "one who preserves the simple/inexperienced ones (פתאים)." The supplicant is described also with the parallel wisdom term דל ("humble, unimportant"). Once again, the wisdom author or editor displays poetic proficiency in incorporating material from an existing source. Some might argue that the intertextual relationship could also be explained as flowing from Ps 116 to the prayer in Jonah. The strong wisdom connections argue against this. What is more, the other occurrences of the Gnadenformel have a more or less fixed form (especially in the oldest version such as in Exod 34:6), while the version in Ps 116 is the deviant one in terms of its addition of "righteous."

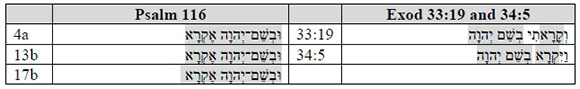

5 Psalm 116 and Exodus 33:19 and 34:5, see also Deuteronomy 32:3

The phrase "in the name of Yahweh I call" is structurally and theologically a very important part of Ps 116. It is possible that the poet abstracted or borrowed this from Exodus, where it occurs in chapter 33:19 and 34:5. Beat Weber made a very important remark regarding the double meaning of קרא as "Anrufung" and "Ausrufung" in the sense of "call" and "proclaim" as well as the use of this word to introduce the theme of Ps 116.24

In Ps 116, at first only the verb אֶקְׁ רא appears in v. 2 as a Leitmotiv. It is subsequently repeated three times as part of the expression "I shall call on/proclaim the name of Yahweh." This expression is part of the refrain which unites the different parts of the psalm. While it is repeated, it is also expanded continually into a form we might call the growing phrase.25Not only is the phrase expanded in such a way that the cola is growing numerically, but it is also growing in importance to reach a climax in vv. 17-19.

In Ps 116:2b it commences as a single colon announcing the theme of the poem, which is then expanded into a bicolon in 4a and 4b. The element which is added in 4b is the א נה יְׁה וה prayer with the request to save his life.26

The next occurrence of the phrase is at the end of the third stanza where it is expanded even further in two bicola in vv. 13 and 14. Three elements are now added to the phrase. Firstly, it is preceded by the words "the cup of salvation I shall lift up," an assurance that the supplicant is saved. This is a metaphorical expression with the same meaning and function as the expression יְׁשו ע תה ליה והin Jon 2:10d. It is then followed by his obligation "to pay his vows" and the space where it should happen is - "in the presence of all his people."

The final and longest version is placed at the end of Stanza IV, right at the end of the poem, in vv. 17-19. It consists of three bicola which is all about the supplicant's obligations, but also the specific place where he should execute them. This final version of the refrain commences with a vow to offer a sacrifice of thanksgiving to Yahweh. The promise of the previous refrain is repeated but also expanded with a precise and specific description that it should happen in the temple in Jerusalem.

In Table 3 the visual growth of this phrase is demonstrated.

It is important to take note of the position where these repeating phrases occur in the poem. The first one occurs at the end Strophe A, where the supplicant expresses his confidence that Yahweh has heard his supplications and therefore, he (the supplicant) will proclaim him during his whole life.

The second repetition of the phrase can be found at the end of Strophe B as a reaction to the distress in which the supplicant finds himself. In this instance the phrase is coupled with the א נה יְׁה וה prayer as a call to save the supplicants life. With the strategic placement of the phrase at the end of the first stanza, it is utilised by the poet as a link to connect the material, which originated from Ps 18, to the rest of the poem.

The third repetition is situated at the end of the Stanza III and corresponds in the symmetric pattern with Stanza I but after affirming the salvation of the supplicant, introduces his obligations.

The last repetition forms the climax of the poem and is placed right at the end of the poem at the end of Stanza IV. In this repetition the obligations of the previous repletion are expanded, but the place where it should be performed is the important item which is added to the formula.

E CONCLUSION

Psalm 116 thus is a prime example of the tendency in late post-exilic Psalmography to compile new poems by using existing material from the Hebrew Bible. Other examples of this style of writing are found in Pss 1; 19; 25; 34; 37; 86; and 119. This has been described in the past as an "anthological" style of composition. Very often in these psalms one can also detect a marked attempt to produce a symmetric pattern (the stichometric table on page 2 above) and also a marked influence from wisdom (the discussion on the Gnadenformal on page 6). All these tendencies are apparent in Ps 116.

As such, the important aspects emphasised in Ps 116, are the "name" theology, where Yahweh has become the preferred name for God; the addition of Yahweh's "righteousness" as one of the appellatives in the Gnadenformel; and the description of the supplicants as "simple" and "oppressed" people. With a further reference to the name theology, a phrase בְׁשֵם יְׁהוה אֶק רא "in the name of Yahweh, I call/proclaim" is borrowed from Exodus, expanded and used as part of a refrain to link the different parts of the poem, but also to announce and explicate the theme of exclaiming the name of Yahweh.

Ps 116 shows connections with other psalms and books in the Old Testament. Some quotations derive from Ps 18 (= 2 Sam 22), which - in its present form - was written by exponents of wisdom theology to help with the interpretation of the history of David, but also from Ps 56. Other quotations come from Exodus while the book of Jonah and especially the poetic sections of Jonah, had a huge influence on the author(s)/editor(s) of Ps 116. Despite these connections and resemblances Ps 116 is a de novo poetic creation written with a very specific goal in mind.

This particular goal is to praise the Lord as part of the collection of the Egyptian Hallel, Pss 113-118. According to Prinsloo, Ps 116 occupies a pivotal position in the collection. Not only is it the middle poem in the collection of five poems, but "it is written completely from a first-person singular perspective, the spatial orientation is mainly vertical, and it is the first mentioning of the temple and Jerusalem in the collection."27

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Leslie C. Psalms 101-50, Revised. Word Biblical Commentary 21. Nashville, TN: Nelson, 2002. [ Links ]

Barré, Michael L. "Psalm 116: Its Structure and its Enigmas." Journal of Biblical Literature 109 (1990): 61-79. https://doi.org/10.2307/3267329. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Clarendon, 1985. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann. Die Psalmen, übersetzt und erklärt. 6th ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar and Zenger, Erich. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101150. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2011. [ Links ]

Janowski, Bernd. "Dankbarkeit: ein anthropologischer Grundbegriff im Spiegel der Toda-Psalmen." Pages 91-136 in Ritual und Poesie. Formen und Orte religiöser Dichtung im Alten Orient, im Judentum und im Christentum. Edited by Erich Zenger. Herders Biblische Studien 36. Freiburg: Herder, 2003. [ Links ]

Janowski, Bernd. Konfliktgespräche mit Gott. Eine Antropologie der Psalmen. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2003. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalms 60-150: A Commentary. Translated by Hilton C. Oswald. Continental Commentaries. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 1989. [ Links ]

Magonet, Jonathan D. Form and Meaning: Studies in the Book of Jonah. Beiträge zur Biblischen Exegese und Theologie 2. Bern: Lang, 1976. [ Links ]

Miller, Geoffrey D. "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research." Currents in Biblical Research 9 (2011): 283-309. [ Links ]

Potgieter, J. Henk 'n Narratologiese Ondersoek van die Boek Jona. (Hervormde Teologiese Studies Supplementum 3. Pretoria: Hervormde Teologiese Studies, 1991. [ Links ]

Potgieter, J. Henk "The Nature and Function of the Poetic Sections in the Book of Jonah." Old Testament Essays 17 (2004): 610-620. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T. M. "Se'ôl - Yerúsãlayim - Sãmayim: Spatial Orientation in the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113-118)." Old Testament Essays 19 (2006): 739-760. [ Links ]

Tull, Patricia. "Intertextuality and the Hebrew Scriptures." Currents in Research: Biblical Studies 8 (2000): 59-90. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90150 and Psalm 1. Oudtestamentische Studien 63. Leiden: Brill, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004262799. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. Werkbuch Psalmen II. Die Psalmen 73 bis 150. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2003. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich (ed.). Ritual und Poesie. Formen und Orte religiöser Dichtung im alten Orient, im Judentum und im Christentum. Herders Biblische Studien 36. Freiburg: Herder, 2003. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 2019/03/04

Peer reviewed: 2019/05/17

Accepted: 2019/07/16

1 With this paper, which I dedicate to my friend and colleague Phil Botha, I want to commemorate with gratitude the journey that we travelled together with the Psalms as our constant companion and beacon. It was a delightful journey thanks to his inspiration and support.

2 Erich Zenger, Ritual und Poesie. Formen und Orte religiöser Dichtung im alten Orient, im Judentum und im Christentum (HBS 36; Freiburg: Herder, 2003), VII.

3 German original: "Wo und wozu sind die biblischen Psalmen entstanden?"

4 Bernd Janowski, "Dankbarkeit: ein anthropologischer Grundbegriff im Spiegel der Toda-Psalmen," in Ritual und Poesie. Formen und Orte religiöser Dichtung im alten Orient, im Judentum und im Christentum (ed. Erich Zenger; HBS 36; Freiburg: Herder, 2003), 91-136.

5 German original (99): "Ps 116, ein typisches Danklied des einzelnen - mit Ankündigung des Danks, Bericht von der Rettung und (Aufforderung zum) Lobgelübde -, hat seinen Ort im Tempelkult und ist dort vom Geretteten 'vor seinem (sc. JHWHs) ganzen Volk' (V. 14b.18b) im Rahmen einer tôdãh-Feier vorgetragen worden (V. 1319)".

6 Beat Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150 (Stuttgart:

Kohlhammer, 2003).

7 German original (246): "M.E. ist der Psalm von seinem Schluss her als individuelles Dankopfer-Lied (Toda) zu bestimmen: Dem göttlichen Machterweis entspricht ein öffentliches Bekenntnis".

8 German original (247): "Ps 116 ist aber kein 'schlichter' Toda-Psalm, sondern aufgrund der Parallelität von erstem und drittem Abschnittsanfang (1a.10a) sowie von Kehrvers-artigen Elementen (4a.13b.17b sowie14.18f.) poetisch stark moduliert".

9 J. Henk Potgieter, "The Nature and Function of the Poetic Sections in the Book of Jonah," OTE 17 (2004): 610-620.

10 For an overview of this research area as applied to the Hebrew Bible, cf. Patricia Tull, "Intertextuality and the Hebrew Scriptures," CR:BS 8 (2000): 59-90; Geoffrey D. Miller, "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research," CBR 9 (2011): 283-309. Cf. the important study by Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985) on the subject of the reuse and reinterpretation of earlier texts in later contexts. Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 7 calls for a proper appreciation of "the development of inner-biblical exegesis and its post-biblical continuities in early Judaism and Christianity."

11 Hans-Joachim, Psalms 60-150: A Commentary (transl. by Hilton C. Oswald; CC; Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 1989), 385.

12 Nearly every author who has written an article or a commentary on Ps 116 made a comment on the widely divergent opinions on the structure, or the lack of regularity in the structure of this psalm (cf. Leslie C. Allen, Psalms 101-150 [WBC 21; Waco, TX: Word, 1983], 114). In an overview of influential authors, an interesting fact emerged. Most of these authors maintain that the psalm can be divided in two major sections. For Frank-Lothar Hossfeld (cf. Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150 [trans. Linda M. Maloney; Hermeneia; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2011], 213-221) and Bernd Janowski ("Dankbarkeit," 99-101), who did their division mainly on form critical criteria. Bernd Janowski, Konfliktgespräche mit Gott. Eine Antropologie der Psalmen (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2003), 298305 calls the first section a "Danksagung" (vv. 1-11), while the second section describes a "Dankopfer" (vv. 12-19). Strangely enough, Gunkel's division (Hermann Gunkel, Die Psalmen, übersetzt und erklärt [6 ed.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986], 499-501), although he was the person who introduced the form critical method, does not coincide with the division of Hossfeld and Janowski. In dividing the psalm after v. 9, he follows the tradition of the LXX which divided the psalm along these lines into two psalms. Although using very different methods, this specific "Zweiteiligkeit" is also maintained by Barré (Michael L. Barré, "Psalm 116: Its Structure and its Enigmas," JBL 109 [1990]: 61-79) and Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II, 245-246. Allen, Psalms 101150, 114 on the other hand, prefers a tripartite division (vv. 1-7, 8-14, 15-19). Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 385-386 maintains that the psalm belongs to the category of thanksgiving songs of an individual, but that the poem is a fragment-like collection and therefore does not display any coherent structure.

13 Barré, "Psalm 116," 61-79.

14 Pieter van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1 (OTS 63; Leiden: Brill, 2014), 271-282.

15 Van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes, 271.

16 Gert T. M. Prinsloo, "Seôl - Yerúsãlayim - Sãmayim: Spatial Orientation in the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113-118)," OTE 19 (2006): 739-760 (744 n. 32) makes a very good argument to this effect.

17 For a discussion of intertextual links between Psalm 116 and other literary corpora in the Hebrew Bible, cf. Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II, 248-249.

18 Barré, "Psalm 116," 69 n. 29.

19 Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II, 247.

20 According to Janowski, "Dankbarkeit," 107 the "lands of the living" are the spatial counterpart of Sheol in the "religiösen Topographie."

21 J. Henk Potgieter, 'n Narratologiese ondersoek van die boek Jona (HTS.Supp 3; Pretoria: HTS, 1991), 41-45.

22 Exod 34:6; Num 14:18; Jon 4:2; Neh 1:5; 9:17; Pss 86:15; 103:8; 145:8; Joel 2:13.

23 In Ps 112:4b there is an addition of וְצַדִּיק to the word pair without interrupting the pair.

24 Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II, 247.

25 Jonathan D. Magonet, Form and Meaning: Studies in the Book of Jonah (BBET 2; Bern: Lang, 1976), 31.

26 Similar prayers, with the same address, occurs two times in Jonah, in Jon 1:14 and 4:2.

27 Prinsloo, "Sôl - Yerúsalayim - Samayim," 749.

Prof Henk Potgieter, Professor Emeritus, Department of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria, South Africa, Email henkpotgieter65@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2278-2600.