Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.32 no.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n2a7

ARTICLES

"The Rivers Have Lifted up their Voice": Imagining the Mighty Waters in Psalm 931

Susanne Gillmayr-Bucher

Catholic private University Linz

ABSTRACT

This paper traces and analyses the various possibilities to interpret the images of the rivers and majestic waters in Ps 93:3-4. The metaphorical description of the waters allows the readers to see a fascinating spectacle of nature but also a threatening natural force. Over centuries, interpreters have creatively explored these possibilities for their readings. To retrace the wide range of possible interpretations of Ps 93:3-4 two contexts are revealing, namely the occurrences of water images in the psalter and the history of interpretation of Ps 93:3-4. The insights these contexts offer are then used to determine the points of reference for such readings in the text, and to reconstruct the different perspectives of the readers and their interpretations.

Keywords: Psalm 93, rivers, water, metaphorical description; water images in the Psalter.

A INTRODUCTION

The waters mentioned in Ps 93:3-4 are described as mighty and majestic entities. Although the psalm leaves no doubt that Yhwh is king and surpasses these waters, the question in which way the waters act towards God has been the subject of controversial debate. The ambivalent presentation of the waters in Ps 93 artfully balances the attitude and actions associated with these waters, they might be dangerously rising up against Yhwh, or they might raise their loud voice in praise. Similarly, their powerful movements could point to a threat, or serve to highlight Yhwh's supremacy.

In this paper, I will trace the fascination and the threat the water images evoked in their readers. To gain insight into the ambivalence of these images in Ps 93, I will provide the text and translation of the psalm. I will then give an overview of the various water images in the psalter. I will next turn to the interpretation history of these images and show by way of examples how the different readings unfolded through centuries. Finally, I will focus on the text of Ps 93:3-4, analyse the images and retrace the possible interpretations.

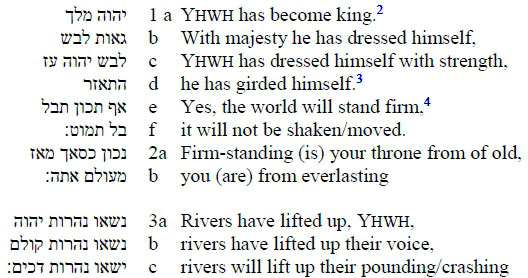

B TEXT AND TRANSLATION

C IMAGES OF THE WATERS IN THE PSALMS

Images of waters are frequently used throughout the Psalter, from fertilising rain, watering brooks and canals to destructive floods and the vastness of the sea. The transition from to life-giving to life-threatening waters, however, is gradual; rain might turn into a storm, a brook into a torrent and the sea can throw up mighty and crashing waves. It is this aspect of the waters' power that forms the background for the images in Ps 93. In the figurative language of the psalms, the waters, the rivers and the sea can be depicted as an enemy threatening the psalmist or the created world, but they are also personified and portrayed as figures with an independent voice so that they are able to respond to God. In this way, the waters can be shown as faithful worshippers of Yhwh.6

Looking at the images of the powerful and potentially destructive waters, the point of view proves to be essential for the evaluation. If the lyrical speaker presents an endangered situation, the psalm usually portrays the waters as destructive and threatening. If a divine point of view is imagined, the psalm presents this view as superior, looking down on the subdued waters. Yet another perspective is depicted in hymns addressing the waters as part of God's creation and inviting them to join God's praise.

1 Threatening and overpowering waters

The lyrical speakers of the psalms often use images of water to emphasise the experience of an overwhelming hostile force or a threatening situation, whereof only God is able to rescue. The description of these waters uses images from the people's living environment but also their artistic and mythical interpretation of the world. The psalmist vividly envisions the waters sweeping over him/her, engulfing and carrying him/her away (e.g. Pss 18:5; 42:8; 69:3, 16; 88:18; 124:45). From the serious threat these waters represent, it is only a small step to the realm of death. Thus it is not surprising that images of water and death are used side by side. When, for example, the lyrical speaker in Ps 18:5 describes his/her distress, the "cords of death" (חבלי מות) and "the rivers of worthlessness/torrents of social harm" (נחלי בליעל) are presented in a parallelism. The נחלי בליעל emphasise the surprising suddenness and intensity of the danger that is as inescapable as the cords of death.7 In this way, images of the psalmist's world, like the flash-floods in the wadis, are used to imagine Sheol and its devastating powers.8

The only hope in these laments lies in Yhwh, who is able to safe the psalmist. Accordingly, some psalms include expressions of thanks, in which an already experienced rescue is told in retrospective. They bear witness to God bringing them back from the depth of the sea, pulling them out of great waters or keeping them safe from the torrents (Ps 32:6, 66:12). A very spectacular rescue is envisioned in Ps 18:7-17. Answering the plea, God appears in a storm theophany, descending from heaven and laying bare the channels (p'SN) of the sea and the foundations of the world (v. 16), before he pulls out the distressed psalmist. These images refer to the rescue at the Sea of Reeds (Exod 14-15), and furthermore, motifs from a mythic fight of a deity against the chaos might be alluded to.9 In this way, Yhwh's power is emphasised even more, because only God is able to rescue the psalmists from enemies as powerful as the chaotic forces.

Besides such reassuring aspects, the image of God commanding the waters can also be presented as the psalmist's worst nightmare. If God is depicted as using the waters as his tools against the psalmist, a rescue is impossible (e.g., Ps 88:7). In this case, the threatening image is intensified, combining divine strength with the force of waters.

2 The submission of the waters

Focussing on a divine handling of the waters, the psalms point out Yhwh's unsurpassed superiority. This is evident when the psalms describe Yhwh's control of space, allocating the waters their location, setting boundaries and putting them into a well-defined, confined space (e.g., Ps 33:7). In this way, the spreading of the waters is limited. Even more, Yhwh has even been able to found the earth upon the waters (Ps 24:1-2; 136:6). "The waters are no longer in a position to pose a threat to Yahweh's control, because they have been utterly subjugated."10

The divine power also becomes obvious when God leads his people through the waters (e.g. Ps 78:13). Also looking back at the exodus, Ps 114:4-5 describes this event as a reaction of the waters to God's guidance of Israel. Shifting the action from Yhwh to the waters, the divine supremacy is not told about, but presented in the reaction. Mockingly, v. 5 then asks the sea and the river Jordan why they fled and turned back. Although the answer is not reported, it is obvious from the context of the psalm that God's superiority forces the submission of the waters. In a similar way, other psalms emphasise God's unchallenged superiority, by highlighting the waters startled reactions to God's appearance (Ps 77:17). God's presence is enough to arouse fear, and God's rebuke causes them to flee (Ps 104:7).

The subjugation of the waters also bears references to images of a divine fight against chaos. Like Marduk or Baal, Yhwh is presented to combat the mighty waters and to overcome their threatening powers.11 Although the psalms often do not present the fight explicitly or in any in detail, several allusions point to the mythical images as a background for the psalms. So, for example, texts speaking of God stilling or ruling the roaring of the seas (Pss 65:8; 74:13; 89:10) or slaying the sea monsters (Pss 74:13-14; 89:11). The imagery of kingdom forms the context for the images of a fight against chaos. It legitimates the king, highlighting the royal task to maintain the order of the world and the creation. God not only founded the earth above the waters, he is enthroned above the chaotic waters.12

Another variation of this motif can be found in Ps 46. In vv. 3-4 the lyrical speaker assures him/herself not to be afraid, despite the roaring and foaming waters,13 and in v. 5 he/she turns towards the waters tamed by God. Here, the river forms a contrast to the chaotic waters, this water is no longer dangerous. In God's presence, at his dwelling, the chaotic waters turn into life-giving streams and canals.14

3 The waters are praising God

In psalms of thanksgiving or in hymns, where the lyrical speaker looks from a secure position at his world, joy and gratitude prevail. From such a perspective, the waters are portrayed as a part of nature and divine creation. Consequently, these palms invite the waters to join the universal praise of God. They are requested to praise (Ps 98:8), to rejoice, clap their hand (Pss 69:35; 98:8; 148:4) and even to roar (e.g., Pss 96:11; 98:7; cf. 1 Chr 16:32). In this context, their otherwise threatening roaring (רעם) is presented as part of their praise. Here the psalms invite their readers to look at the whole creation from a distant point of view. Seen from such a secure perspective, the force of nature, that becomes obvious when looking at a storming sea or wadis turning into torrents, is depicted as an aesthetic image. The readers thus are allowed to focus on the beauty of the waters' power.

This short overview has shown that, no matter how powerful the psalms imagine the waters, they always are presented as being inferior to Yhwh. Although the lyrical speakers frequently use water images to describe their emergency situation, they feel threatened of being overpowered by the waters, God's superiority keeps the waters at bay, defeating or suppressing them. By shifting the perspective from the endangered psalmists to a confrontation between God and the waters, the psalms are able to overcome the terror and find hope and confidence in God's supreme strength. Following this line of thought, the waters' power can be perceived with wonder and awe as long as God's superiority is part of the psalmist's experience.

D THE CHANGING INTERPRETATION OF THE WATERS IN PSALM 93 OVER TIME

The description of the increasing force of the mighty waters gave rise to the imagination of a warlike situation throughout the history of interpretation of Ps 93. Saint Jerome already notes on Ps 93:3-4: "There are as many meanings here as there are words; as many secrets, as versicles."15 Despite all the differences, there are mainly two lines of interpretation: one identifying the waters with enemies or threatening forces rising against God; and the other, understanding the voices of the waters as their praise of God.

Identifying the waters as enemies within the biblical stories, one interpretation in the Midrash on the Psalms, ascribed to R. Simeon ben Yohai, identifies the flood with the Philistines,16 Rashi and Qimhi compare the rivers with Gog and Magog and the other kings joining them in their war against Jerusalem. Also R. Moshe ben Chayim Alshech (16th century) interprets v. 4 as a lament of Moses, who complains that God's mercy allows these enemies to achieve prominence, but expresses the hope that the exaggeration of their oppressive rule will lead to a divine intervention.17

Emphasising the threatening dimension of the rivers, illustrations of Byzantine Psalters relate Ps 93 to the legend of a miraculous rescue from mighty waters by the Archangel Michael.18 In Chonea, so this legend tells, the Archangel Michael prevented the flooding of a sanctuary, which opponents of the sanctuary and the righteous ecclesiarch Archippos, who was serving there, initiated by first damming and then releasing the rivers' waters. The illustrations show how Michael, by funnelling the onrushing waters, kept the church and Archippos save. By connecting this legend with Ps 93, the illustration gives an example of divine superiority. Furthermore, it interprets the divine superiority presented in Ps 93 as an active intervention that might be brought about by praying Ps 93.

Besides the numerous identifications of the waters with the enemies, the lack of a lament or an explicit reference to a fight also encouraged interpreters to read the water's actions in line with the admiring view of the whole psalm.19They are not the enemy, rather the rivers are identified with Yhwh's admirers raising their voices in praise. The Targum of Psalms, for example, associates their voices with praise, they are giving praise to God,20 and, furthermore, receiving a reward for their praise.21 In the Christian tradition, quite similarly, the waters are attributed the task of proclaiming Jesus Christ (e.g., Saint Jerome,22 Saint Augustine,23 or Cassiodorus24). Although this line of interpretation does not become dominant, it is continued.

Commentaries, foregoing direct attempts to connect the psalm's images with the reality of its own time, sometimes focus on the accentuation of God's majesty through the lens of a spectacle of nature. From a safe distance, the storm-swept sea and billowing waters offer an aesthetic experience that is fascinating and frightening at the same time.25 This line of interpretation emphasises divine dominance and majesty by presenting a natural phenomenon and imagining God as surpassing this image. Closely following the biblical text, the lyrical translation of the psalm by Mary Sidney, for example, points to divine dominance by emphasising its superiority despite the uproar of the mighty waters. The waters' power is put into perspective by the concessive conjunction "though," thus pointing to a superior divine force from the beginning:

Rivers, yea, though Rivers roar,

Roaring though sea-billows rise,

Vex the deep, and break the shore:

Stronger art thou, Lord of skies.26

It is further noteworthy that the church fathers sometimes did not make a choice between a reading of the waters as enemies or worshippers, but combined both possibilities. In these readings, the rivers (נהר) in v. 3 represent the Apostles or the faithful speaking filled with God's mighty spirit, while the image of the sea ('מים) (v. 4) represents threatening forces and various hazards. Augustine argues that the rivers lifting up their voices points to Jesus' disciples, who - once they had received the Holy Spirit - lifted up their voices and started to proclaim. However, the sea in the next verse represents the adversaries. As "Christ began to be preached by many strong voices the sea began to surge fiercely, and persecution intensified."27 Martin Luther follows this interpretation of the church fathers in his "Summarien über die Psalmen und Ursachen des Dolmetschens (1533)".28 There, he identifies the rivers (v. 3) with the apostles and faithful peoples rising up and preaching in public. Their roaring is the voice of the gospel. In contrast, the raising of the waves are the arrogant principalities and forces of this world attacking the righteous believers.29 Elsewhere, however, he does not differentiate the waters but understands the raging waters in total as an allegory, pointing to the hostile rulers and peoples.30

In the numerous Christian psalm paraphrases and songs written in the time of the Reformation, the waters are frequently compared only with the opponents of the new doctrine, equating them with hellish forces trying to crush true Christianity. To name just one example, Burkard Waldis, a protestant poet and student of Martin Luther, wrote in 1553:31

Da wiedertrutzt das helisch heer

Mit toben und mit wueten

Und brausen grewlich wie das Meer

Sie sein nicht zuvergüten.

Das Ein theyl stracks die Leer vernicht

Bluotig das ander gegen ficht

Den Christum auff zu reiben

Und auß der welt zu treiben.32

This tradition of equating the waters with various enemies remains the most common interpretation until today. What varies is the identity of the enemies the interpreters associate with the image of the waters.33 With the rise of a historical-critical approach, the allegorical interpretation, and with it the identification of the waters with the enemies of the Church disappeared, and the attention shifted to the reconstruction of the "biblical world." Hence, interpreters related the rivers and the sea to powerful gentile nations and empires from biblical times (e.g., Egypt, Assyria or Babylon) threatening ancient Israel or God's kingdom.34 Since the discovery of Mesopotamian and Ugaritic texts, interpretations of Ps 93 used these texts to reconstruct the authors' cultural background and their imaginations. Images of Baal or Marduk as heavenly sovereign, and the mythological narrations of their rise to king the fights and the depiction of the enemies they had to overcome, especially the chaotic force of the great waters, introduced a new horizon for the interpretation for the image of Yhwh as king.35 Furthermore, when the myths of Marduk defeating Tiamat, or Baal subduing Jammu, are considered the basis for many water images, this leads to an even more pronounced focus on the waters as the opponents. They become chaotic forces threatening God's reign or creation.36

Nonetheless, in the course of this discussion, not only similarities are emphasised, but attention is also paid to the differences. Especially the lack of any description of a fight between Yhwh and chaotic forces lead to a modified understanding of the relationship between the Yhwh kingship psalms and the Mesopotamian or Ugaritic myths. With this in view, Oswald Loretz points out that the focus on the fight has long been replaced by an emphasis on Yhwh's kingship. Although Ps 93 refers to Yhwh's victory over Jammu, the sea, or Môt, the deity of the dead, there is no actual danger or fight depicted. Rather, Yhwh's victory is presented as a more general image, he has overcome all his enemies. Thus, the fight with Jammu and the accession to the throne might be alluded to, however in a reduced form.37 Continuing this line of thought, Jörg Jeremias emphasises that Ps 93 does not depict how Yhwh became king, but how his kingdom affects the earth, from primeval times to the future. The narration of the myth was transferred to the description of a permanent state/condition. Although Ps 93, and also the other psalms in this group of psalms, frequently use mythological images, they do not follow its narrative depicting the deity's struggle with hostile chaos.38 They rather praise God as an uncontested, infinite sovereign.39

These few examples already show that the various interpretations of the water images in Ps 93:3-4 throughout the centuries reflect the whole spectrum of water images in the psalter. The threatening aspects are vividly developed identifying the waters with enemies, natural or mythical forces. In addition, the idea of the mighty waters joining God's praise is also expressed. Although the frightening impressions prevail, the aesthetic fascination caused by the mighty waters remains.

E A CLOSE LOOK AT THE WATER IMAGES IN PSALM 93:3-4

Both the survey on the water images in the psalms and the brief overview of the interpretations of Ps 93:3-4 made it clear that the intense, yet ambivalent images of these verses can hardly be contained.

A brief look at the context of the whole psalm and its structure does not bring a clarification either, but rather confirms the ambivalence of the water images. While the first and third stanza focus on the stability of Yhwh's reign as (cosmic) king (vv. 1-2) and its historical and earthly representation (v. 5), the waters are mentioned in the second stanza (vv. 3-4) confronting or comparing God with the rising rivers and the waters.40 In addition to the dominating theme of stability in the first stanza, the second stanza adds movement and sound as the psalm introduces the rivers and mighty waters. Hence, the dominant theme of stability (vv. 1-2) is contrasted by the movement of the waters, which are presented with increasing impressiveness. Yet the images are not presented in detail, but it is left to the readers' imagination to fill in the gaps and blanks. Furthermore, the mention of waters and their voices allows the readers to fill in a wide variety of images, experiences or mythical traditions with their respective connotations and emotional charges. In the following, a close reading of these verses will focus on possible intersections where the dynamic of the text requires the readers' participation.

Verse 3 introduces the rivers (inn) and presents their actions in a climactic, stair-like parallelism. The threefold repetition of the same words at the beginning of each line in v. 341 puts a special emphasis on the rivers and their "lifting up." At first, this action is mentioned without further specification: "the rivers have lifted up," leaving it to the reader's imagination what the rivers are lifting up or carrying away.42 The short break, caused by the vocative "Yhwh," and the following repetition of the rivers' activity, allows, maybe even encourages, different images, before the next line specifies the activity: "the rivers have lifted up their voices".43 The third line introduces a dangerous aspect by explicitly mentioning that the waters lift up their crashing (דכי),44 and thus a potentially destructive action.45 Again, the readers have to fill in information as to which way the rivers are crushing. The images they might add range from waterfalls, crushing into the riverbed, to torrents, crushing everything in their way. Depending on which images they choose, the image is fascinating, although potentially dangerous, or harmful and even life threatening. The dynamic of this parallelism is further enhanced by different aspects of the verbs. While the first two lines describe the waters' actions in retrospect, the third line looks ahead, thus pointing out, that the rivers might rise (again) with threatening intentions.46In this way, the artfully constructed image of the waters lifting up unfolds step by step the power of the rivers. First, the rising evokes a visual image, then this action becomes audible and finally, the rivers' power might give rise to anxiety. Whether this image of the rivers points out their power in comparison or in opposition to God being king, however, cannot be determined. The personification of the rivers presents them as actors, whose intention remain hidden behind their powerful actions. Reading v. 3 as an image of powerful rivers is supported by the most common usage of נהר as a distinctive topographic entity, or life-giving waters (e.g., Ezek 31:4-5) guaranteeing the fertility of the land (e.g., Num 24:6-7). The idea that the rivers might raise their voice is easily imaginable in the context of praise. Even their crashing, especially the sound produced by crashing waters, could be subsumed under the image of enthusiastic jubilation (cf. Ps 98:8). Conversely, focusing on a threatening aspect, the activity of rivers lifting up can precede a flood, and the raising of their voice refers to a torrent, that comes with crashing force. In this way, the rivers' destructive potential is highlighted. It is further noteworthy that the psalm explicitly addresses this description to Yhwh (3a), thus engaging God in the perception of the rivers. But again, this intention remains ambivalent. The lyrical speaker can bring the rivers' praise to Yhwh's attention, or point to their threatening force in the hope of God's protection.

The next verse, again shaped as a climactic parallelism, pursues the water image, albeit shifting the focus. While v. 3 presented the rivers, v. 4 focusses on God in relation to the mighty and majestic waters. In this way, v. 4 is a reflection on the situation described in v. 3, presented from a more distanced point of view. Verse 4 first mentions the voices of the great waters (מים רבים); it then continues with the majesty of the waves of the sea (משברי ים) and ends with a statement of God's majesty.

In contrast to the rivers, the voices of the great waters are not attributed a dynamic role, nor are the waters presented themselves. This line mentions only their voices, it is nothing but the impression of sound. The voices of the great waters point to an imposing, maybe frightening, but not necessarily hostile event. How awe-inspiring such a sound might be, becomes more obvious in Ezekiel's descriptions of a theophany. In his visions, the prophet compares the sound of the wings of the living creatures (Ezek 1:24) and the sound of God's coming (Ezek 43:2) to the voice of the great waters.47 In the second line of v. 4, the breakers of the sea add a potentially threatening aspect (cf. 2 Sam 22:5; Jonah 2:4; Ps 88:8), that is further strengthened by their description as majestic (אדיר). Nonetheless, without mentioning an action, the image of majestic and powerful waves does not unfold its dangerous potential.48 The threat is further kept at bay by the comparison these images are part of. Hence, the strength and majesty of the waters are put into perspective from the beginning, as the principal aim of this description is the point of comparison, which, however, is not mentioned immediately. This postponement creates suspense, and furthermore, it gives the mighty waters and their waves the full attention before the third line mentions God as the ultimate and superior force (cf. Ps 89:10). The construction of this line puts a special emphasis on the final element, the name of Yhwh.49 It is Yhwh, and no one else, who is mightier and more majestic than the waters. The seemingly simple statement that "Yhwh is majestic on high" thus is transformed into a superlative, Yhwh's majesty is unsurpassed and unmatched (cf. Ps 97:9). God's position stands in opposition to other rising powers, his superiority being summarised with the spatial metaphor of "up is superior." This height points to Yhwh's sublime position (cf. Isa 24:23; Mic 4:7), enabling him to dominate the world.50 Although the waters are presented in opposition to Yhwh, "the context here is one of comparison, not one of conflict itself. The power and majesty of the sea are used to highlight divine superiority, so that "God appears here less as Victor than as Superior Other."51 Nonetheless, the waters are not diminished, they still are a mighty force. Taking the storm-swept sea as an input for this image, it offers a view on a spectacle of nature from a seemingly safe distance.52The lyrical speaker is not in the danger zone and, furthermore, he/she is convinced, that Yhwh's power surpasses the mighty sea. Given this conviction, the view can be fascinating and threatening at the same time.53

References to mythological narratives can be easily seen in this stanza. The juxtaposition of Yhwh and the majestic waters allude to Mesopotamian and Canaanite deities fighting against chaotic forces. This allusion is further strengthened by the use of a climactic staircase parallelism, which is quite common in Ugaritic literature.54 Unlike the Ugaritic or Mesopotamian myths, however, Ps 93 does not explicitly depict a contest or fight between God and the forces of chaos. YHWH is not fighting for his kingship, neither is he defending it nor is his power endangered in any way.55 Although the waters are presented in opposition to Yhwh, the aim of this verse is a comparison, not the presentation of a conflict. The power and majesty of the sea are used to highlight divine superiority. while the allusions to a mythological background are still recognizable, the narration of the myth has been transformed into a description of Yhwh's reign. 56

F FASCINATING AND FRIGHTENING WATERS

The image of God as king, as it is presented in Ps 93, emphasises God's splendour and uncontested strength as well as his unlimited reign. From this divine image, the psalm derives the stability of the earth and God's reliable presence. The waters in vv. 3-4 form an essential part of this image highlighting God's unsurpassable domination. Before the psalm turns to the water images, it ensures that the firm stability of the earth and the confidence in God's readiness to defeat all threats is confirmed (v.1-2). This is the starting point the readers are invited to join. From this secure position, they may look at the waters, offering a spectacle of nature that is fascinating and frightening at the same time. The ambiguous images of the waters are open for different understandings, and they stimulate different emotions. On the one hand, images of waters can be blended with experiences of hostility and danger, thus they evoke fear. On the other hand, the aesthetic dimension of the powerful, breaking waves and the raving body of waters is also present, inspiring joy, admiration or enthusiasm. Thus, the readers can follow the image in two directions, either emphasising the fascinating aspect, marvelling at the waters' subordination and praise; or, highlighting the threatening facet, the overwhelming power of the waters, and thus feeling relieved that Yhwh is superior. This openness to different interpretations is also made easier by the fact that Ps 93 is presented in a rather distanced way. This psalm does not invite the readers to join in praise, nor does it encourage them to identify with the suffering psalmist. Nonetheless, it offers the readers a magnificent divine image and shows confidence in the stability of the world they might find convincing. However, which role the waters play in this description, is not determined. Which point of view the readers should choose, is based on their own situations and their points of interest. Depending on whether they are able to read this psalm as a joyful depiction of a stable world, in which even the most powerful forces are part of the whole, or whether they understand this psalm as a description of a power-balance they need to ascertain or yet hope to experience, they will emphasise the fascinating or frightening aspects of the waters.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alshech, Moshe. The Book of Psalms with Romemot El. Commentary of Rabbi Moshe ben Chayim Ashech (hakadosh). Translated by Eliyahu Munk. Jerusalem: Munk, 1990. [ Links ]

Alter, Robert. The Book of Psalms. New York, NY: Norton, 2007. [ Links ]

Artemov, Nikita. "Unterweltsflüsse, Chaoswasser oder gefährliche Wadis? Notizen zu den 'Strömen Belials' in Ps 18, 5 = 2 Sam 22, 5." Pages 180-193 in Ich will dir danken unter den Völkern. Studien zur israelitischen und altorientalischen Gebetsliteratur. Festschrift für Bernd Janowski zum 70. Geburtstag. Edited by Alexandra Grund, Annette Krüger and Florian Lippke. Gütersloh: Gütersloher, 2013. [ Links ]

Baethgen, Friedrich. Die Psalmen. Handkommentar zum Alten Testament II/2. Göttingen: Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1892. [ Links ]

Bauks, Michaela. "'Chaos' als Metapher für die Gefährdung der Weltordnung." Pages 431-464 in Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte. Edited by Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 32. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001. [ Links ]

Berlejung, Angelika. "Unterwelt / Jenseits / Hölle / Scheol." Pages 437-439 in Handbuch theologischer Grundbegriffe zum Alten und Neuen Testament. Edited by Angelika Berlejung and Christian Frevel. 5th ed. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2006. [ Links ]

Berlejung, Angelika. "Tod und Leben nach den Vorstellungen der Israeliten. Ein ausgewählter Aspekt zu einer Metapher im Spannungsfeld von Leben und Tod." Pages 465-502 in Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte. Edited by Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 32. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001. [ Links ]

Braude, William. The Midrash of Psalms, Volume 2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1959. [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles A. and Emilie G. Briggs. The Book of Psalms, Volume 2. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: T& T Clark, 1907. [ Links ]

Cassiodorus. Explanation of the Psalms, Volume 2. Translated by P. G. Walsh. Ancient Christian Writers 52. New York, NY: Paulist, 1991. [ Links ]

Curtis, Adrian H. W. "The 'Subjugation of the Waters' Motif in the Psalms: Imagery or Polemic?" Journal of Semitic Studies 23 (1978): 245-256. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/23.2.245. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, Franz. Biblischer Kommentar über die Psalmen. Leipzig: Dörfling & Frank, 1894. [ Links ]

Edwards, Timothy M. The Targum of Psalms. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 2004. [ Links ]

Ego, Beate. "Die Wasser der Gottesstadt. Zu einem Motiv der Zionstradition und seinen kosmologischen Implikationen." Pages 361-389 in Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte. Edited by Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 32. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001. [ Links ]

Ehrlich, Arnold B. Die Psalmen. Berlin: Poppelauer, 1905. [ Links ]

Geller, Stephen A. "Myth and Syntax in Psalm 93." Pages 321-331 inMishneh Todah: Studies in Deuteronomy and Its Cultural Environment in Honor of Jeffrey H. Tigay. Edited by Nili Sacher Fox, David Glatt-Gilad, and Michael J. Williams. winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann. Die Psalmen. Göttinger Handkommentar zum Alten Testament II/2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1926. [ Links ]

Hamlin, Hannibal, Michael Brennan, Margaret Hanny, and Noel Kinnamon, eds. The Sidney Psalter: The Psalms of Sir Philip and Mary Sidney. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Hartenstein, Friedhelm. Die Unzugänglichkeit Gottes im Heiligtum. Jesaja 6 und der Wohnort JHWHs in der Jerusalemer Kulttradition. Wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament 75. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1997. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar and Erich Zenger. Psalmen 51-100. Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, 2000. [ Links ]

Human, Dirk J. "Psalm 93: Yahweh Robed in Majesty and Mightier than the Great Waters." Pages 147-169 in Psalms and Mythology. Edited by Dirk Human. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 462. New York: T& T Clark, 2007. [ Links ]

Janowski, Bernd. "Das Königtum Gottes in den Psalmen. Bemerkungen zu einem Gesamtentwurf." Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 86 (1989): 389-454. [ Links ]

Jefferson, Helen G. "Psalm 93." Journal of Biblical Literature 71 (1952): 155-160. [ Links ]

Jeremias, Jörg. Das Königtum Gottes in den Psalmen: Israels Begegnung mit dem kanaanäischen Mythos in den Jahwe-König Psalmen. Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments 141; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1987. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick, Alexander F. The Book of Psalms. Books IV and V. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalmen 60-150. 2nd ed. Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament 15/2. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1961. [ Links ]

Lamparter, Helmut. Das Buch der Psalmen II. Psalm 73-150. Die Botschaft des Alten Testaments 15. Stuttgart: Calwer, 1990. [ Links ]

Lass, Magdalena. ... zum Kampf mit Kraft gegürtet: Untersuchungen zu 2 Sam 22 unter gewalthermeneutischen Perspektiven. Bonner Biblische Beiträge 185. Göttingen: V&R unipress and Bonn University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737008167. [ Links ]

Loretz, Oswald. Ugarit-Texte und Thronbesteigungspsalmen: Die Metamorphose des Regenspenders Baal-Jahwe (Ps 24,7-10; 29; 47; 93; 95 - 100 sowie Ps 77,1720; 114). Ugaritisch-biblische Literatur 7. Münster: Ugarit Verlag, 1988. [ Links ]

Magni Aurelii Cassiodori. Expositio Psalmorum LXXI-CL. Corpus Christianorum: Series Latina 98. Turnholti: Brepols, 1958. [ Links ]

McGovern, John. "The waters of death." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 21 (1959): 350358. [ Links ]

Mosis, Rudolph. "'Ströme erheben, Jahwe, ihr Tosen...': Beobachtungen zu Ps 93." Pages 223-255 in Ein Gott, eine Offenbarung: Beiträge zur biblischen Exegese, Theologie und Spiritualität. Festschrift für Notker Füglister zum 60. Geburtstag. Edited by Friedrich V. Reiterer. Würzburg: Echter, 1991. [ Links ]

Mülhaupt, Erwin, ed. D. Martin Luthers Psalmen-Auslegung. Psalmen 91-150, vol. 3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1965. [ Links ]

Pardee, Dennis. "The Poetic Structure of Psalm 93." Studi epigrafici e linguistici sul Vicino Oriente antico 5 (1988): 163-170. [ Links ]

Reif, Stefan C. "Psalm 93: An Historical and Comparative Survey of its Jewish Interpretations." Pages 193-214 in Genesis, Isaiah and Psalms. A Festschrift to Honour Professor John Emerton for his Eightieth Birthday. Edited by Katharine J. Dell et al. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 135. Leiden: Brill, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004182318.i-261.41. [ Links ]

S. Hieronymi Presbyteri. Tractatus Sive Homiliae in Psalmos, in Marci Evangelium aliaque varia Argumenta. Corpus Christianorum: Series Latina 78. Turnholti: Brepols, 1958. [ Links ]

Saint Augustine. Expositions of the Psalms 73-98. Translated by Maria Boulding. The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century. New York, NY: New City Press, 2002. [ Links ]

Sancti Aurelii Augustini. Ennarrationes in Psalmos LI-C. Corpus Christianorum: Series Latina 39. Turnholti: Brepols 1956. [ Links ]

Schegg, Peter. Die Psalmen, vol. 2. München: Verlag der J.J. Lentner'schen Buchhandlung, 1846. [ Links ]

Segal, Benjamin. "'Above the Thunder of the Mighty Waters': Ps 93." Conservative Judaism 58 (2005): 59-65. [ Links ]

Stärk, Willy. Lyrik (Psalmen, Hoheslied und Verwandtes). Die Schriften des Alten Testaments in Auswahl neu übersetzt und für die Gegenwart erklärt Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1911. [ Links ]

Stolz, F. "נשא ns' aufheben, tragen". Pages 109-117 in vol. 2 of Theologisches Handwörterbuch zum Alten Testament. Edited by Ernst Jenni and Claus Westermann. 2 vols. München: Kaiser, 1971 -1976. [ Links ]

Sylva, Dennis. "The Rising mini of Psalm 93: Chaotic Order," Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36 (2012): 471-482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089212438006. [ Links ]

The Barberini Psalter (11th century). Vatican Library Manuscript Barb. grec. 372, f. 160v. https://digi.vatlib.it/mss/detail/Barb.gr.372. [ Links ]

The Homilies of Saint Jerome, Volume 1. Translated by Marie Liguori Ewald. The Fathers of the Church 48. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1966. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt284twm. [ Links ]

Theodore of Caesarea. The Theodore Psalter. Manuscript 19352 British Library. Constantinople 1066. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_19352f001r. [ Links ]

Theodõrêtu Episkopu Kyru Hapanta, Theodoreti. Opera Omnia. Edited by Johann Ludwig Schulze, Jacques Paul Migne. Patrologiae cursus completus Series Graeca 80. Paris: S. et G. Cramoisy, 1864. [ Links ]

Theodoret of Cyrus. Commentary on the Psalms: Psalms 73-150. Translated by Robert C. Hill. Fathers of the Church 102; Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Trudinger, Peter. "Friend of Foe? Earth, Sea and Chaoskampf in the Psalms." Pages 2941 in The Earth Story in the Psalms and the Prophets. Edited by Habel Norman. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Tucker, W. Dennis, Jr. and Jamie A. Grant. Psalms, Volume 2. NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2018. [ Links ]

Waldis, Burkard. Der Palter Jn Newe Gesangs weise vnd künstliche Reimen gebracht. Frankfurt: Egenolff, 1553. [ Links ]

Weiser, Artur. Die Psalmen II: Psalm 61-150. 10th ed. Das Alte Testament Deutsch 15. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1987. [ Links ]

Wither, George. The Psalmes of David translated into lyrick-verse, according to the scope, of the original. Amsterdam: van Breughel, 1632. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 2019/03/04

Peer reviewed: 2019/05/14

Accepted: 2019/07/18

1 I dedicate this contribution to Phil Botha upon his 65 birthday.

2 The verb מלך qal perf. refers to an event in the past. The phrase " Yhwh has become king" occurs several times in the psalms (Pss 93:1; 96:10; 97:1, 99:1). With a human subject instead of God, the phrase is frequently used referring to the years a king reigned (1 Sam 13:1; 2 Sam 5:4-5; 1 Kgs 2:11) or proclaiming that somebody (just) became king (e.g., 2 Sam 15:10; 2 Kgs 9:13). This second usage already suggests that the perfective verb form also refers to a still ongoing state: somebody just became king and now he reigns as king.

3 It is not clear whether עז is an object to the verb לבש (1c) or אזר (1d). Syntactically both variants are possible. (1) Reading עז with אזר is supported by the Masoretic punctuation (signalled by an atnach after a munach): "he has girded himself with might." With regard to the use of parallelism, reading עז with לבש leads to a synthetic parallelism with a chiastic word order. (2) However, in Qumran texts and ancient translations, T57 is frequently combined with לבש in 1c. These texts sometimes also replace the perfect form with waw consecutive (e.g., 11Q5/11QPs, col. XXII, 16; LXX (και περιεζώσατο), Vetus Latina, Peshitta and Targum), thus adding 1d as a closely connected action to 1c: "he has dressed himself with might and he has girded himself." With regard to other occurrences in the MT, it can be noted that לבש as a finite verb it is never used without naming a garment (except in the case of an ellipse, Gen 28:20; Job 27:17). Together with עז the verb לבש occurs, e.g., in Isa 51:9; 52:1. Furthermore, the phrase "to gird or be girded with strength" is otherwise constructed with חיל (1 Sam 2:4; 2 Sam 22:40; Ps 18:33, 40), or גבורה (Ps 65:7), but never with עז. For this reason, I prefer to read עז together with לבש (1c) (cf. Rudolph Mosis, "'Ströme erheben, Jahwe, ihr Tosen...': Beobachtungen zu Ps 93," in Ein Gott, eine Offenbarung: Beiträge zur biblischen Exegese, Theologie und Spiritualität. Festschrift für Notker Füglister zum 60. Geburtstag (ed. Friedrich V. Reiterer. Würzburg: Echter, 1991), 223-255 (229-236), although the combination with אזר is possible and preferred by most interpreters.

4 Both LXX and 11QPs, col. XXII, 17 change the subject, continuing God's actions (11QPs "you made firm the world"; LXX and Targum "he made firm the world," hence introducing the image of creation, cf. Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalmen 51-100 (HThKAT; Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, 2000), 644. If this adjustment is a deliberate change or if they read tikkën (cf. Ps 75:4) cannot be ascertained.

5 The syntactic construction of 4a-b is not straightforward, rather there are several possibilities to read it. (1) Because אדירים is a parallel expression to רבים it can be a second attribute to מים: "More than the voices of great, majestic waters, the waves of the sea" (cf. Exod 15:10), or as Delitzsch translates, "the majestic (ones), the waves of the sea", it could be part of the apposition (Franz Delitzsch, Biblischer Kommentar über die Psalmen [Leipzig: Dörfling & Frank, 1894], 643). (2) If אדירים starts a noun clause (4b), it reads "majestic (are) the waves of the sea." (3) However, most commentaries emend אדירים to the singular and regard the final mem as mem of comparison. The remaining yod at the end of the first word has either to be deleted or it can be explained as yod paragogicum (Dirk J. Human, "Psalm 93: Yahweh Robed in Majesty and Mightier than the Great Waters," in Psalms and Mythology [ed. Dirk J. Human; LHBOTS 462; New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2007], 147-169 [151]; Stephen A. Geller, "Myth and Syntax in Psalm 93," in Mishneh Todah: Studies in Deuteronomy and Its Cultural Environment in Honor of Jeffrey H. Tigay [ed. Nili Sacher Fox et al.; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009], 321-331 [322]). With this emendation, the text (4b) forms a second comparative: "more majestic than the waves of the sea."

6 Peter Trudinger, "Friend of Foe? Earth, Sea and Chaoskampf in the Psalms," in The Earth Story in the Psalms and the Prophets (ed. Habel Norman; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 2001), 29-41 (40).

7 Cf. Nikita Artemov, "Unterweltsflüsse, Chaoswasser oder gefährliche Wadis? Notizen zu den "Strömen Belials" in Ps 18,5 = 2 Sam 22,5," in Ich will dir danken unter den Völkern. Studien zur israelitischen und altorientalischen Gebetsliteratur. Festschrift für Bernd Janowski zum 70. Geburtstag (ed. Alexandra Grund et al.; Gütersloh: Gütersloher, 2013), 185.

8 Cf. John McGovern, "The waters of death," CBQ 21 (1959): 350-358 (358). Furthermore, the sea, like the dessert, is a place where the realm of the dead is present, and where sometimes the entrance to the underworld was located. See Angelika Berlejung, "Unterwelt / Jenseits / Hölle / Scheol," in Handbuch theologischer Grundbegriffe zum Alten und Neuen Testament (ed. Angelika Berlejung and Christian Frevel; 5 ed.; Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2006), 437-439 (437); cf. also Angelika Berlejung, "Tod und Leben nach den Vorstellungen der Israeliten. Ein ausgewählter Aspekt zu einer Metapher im Spannungsfeld von Leben und Tod," in Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (ed. Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego; FAT 32; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001), 465-502 (486); Magdalena Lass, ... zum Kampf mit Kraft gegürtet: Untersuchungen zu 2 Sam 22 unter gewalthermeneutischen Perspektiven (BBB 185; Göttingen: V&R unipress and Bonn University Press, 2018), 252.

9 Artemov, "Unterweltsflüsse," 187.

10 Adrian H.W. Curtis, "The 'Subjugation of the Waters' Motif in the Psalms; Imagery or Polemic?" JSS 23 (1978): 245-256 (248).

11 For an outline of the most important variants of this conflict's (epic and ritual) presentation cf. Michaela Bauks, "'Chaos' als Metapher für die Gefährdung der Weltordnung," in Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (ed. Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego; FAT 32; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001), 431-464.

12 Cf. Bauks, "Chaos," 453-460.

13 Ego interprets v. 4 as an image of ultimate chaos, waters as shapeless without structure. The terminus ΠΊίο adds royal imagery to the water and thus alludes to the image of a divine battle. However, the outcome is already decided, no actual fight is presented. See Beate Ego, "Die Wasser der Gottesstadt. Zu einem Motiv der Zionstradition und seinen kosmologischen Implikationen," in Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (ed. Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego; FAT 32; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001), 361-389 (365).

14 Ego, "Die Wasser der Gottesstadt," 366-368.

15 The Homilies of Saint Jerome, Volume 1 (trans. Marie Liguori Ewald; FC 48; Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1966), 97. Orig. "Quot uerba, tot sensus: quot uersiculi, tot sacramaneta." S. Hieronymi Presbyteri. Tractatus Sive Homiliae in Psalmos, in Marci Evangelium aliaque varia Argumenta (CCL 78; Turnholti: Brepols, 1958), 431.

16 William Braude, The Midrash of Psalms, Volume 2 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1959), 126.

17 Moshe Alshech, The Book of Psalms with Romemot El. Commentary of Rabbi Moshe ben Chayim Ashech (hakadosh) (trans. Eliyahu Munk; Jerusalem: Munk, 1990), 711.

18 Theodore of Caesarea, The Theodore Psalter. Manuscript 19352 British Library. Constantinople 1066, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_19352_f001r or The Barberini Psalter (11th century). Vatican Library Manuscript Barb. grec. 372, f. 160v. https://digi.vatlib.it/mss/detail/Barb.gr.372.

19 For the Jewish tradition, Reif points out that the aggadic interpretation "wavers between the waters associated with the act of creation and waters as a metaphor for the enemies of Israel." Cf. Stefan C. Reif, "Psalm 93: An Historical and Comparative Survey of its Jewish Interpretations," in Genesis, Isaiah and Psalms. A Festschrift to Honour Professor John Emerton for his Eightieth Birthday (ed. Katharine J. Dell et al.; VTSup 135; Leiden: Brill, 2010), 193-214 (202).

20 "Such an association is commonplace in rabbinic literature, which associates this praise with creation." Timothy M. Edwards, The Targum of Psalms (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 2004), 125.

21 This interpretation of D'Dl is unique, cf. Edwards, The Targum of Psalms, 125.

22 Hieronymus, Tractatus, 432.

23 Sancti Aurelii Augustini, Ennarationes in Psalmos LI-C (CCL39; Turnholti: Brepols, 1956), 1297-1299.

24 Magni Aurelii Casiodori, Expositio Psalmorum LXXI-CL (CCL 98; Turnholti: Brepols, 1958), 854.

25 Charles A. Briggs and Emilie G. Briggs, The Book of Psalms, Vol. 2 (ICC; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1907); Peter Schegg, Die Psalmen (München Verlag der J.J. Lentner'schen Buchhandlung, 1846).

26 Hannibal Hamlin et al. (eds.), The Sidney Psalter: The Psalms of Sir Philip and Mary Sidney (Oxford World's Classics; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

27 Augustine, Expositions of the Psalms, 370. Orig. Augustinus, Ennarrationes, 1298; see also Hieronymus, Tractatus, 432; or Theodoret of Cyrus' commentary on Ps 92. Theodõretu Episkopu Kyru Hapanta, Theodoreti, Opera Omnia (ed. Johann Ludwig Schulze, Jacques Paul Migne; Patrologiae cursus completus Series Graeca 80; Paris, 1864), 1625-1628.

28 Erwin Mülhaupt, ed., D. Martin Luthers Psalmen-Auslegung. Psalmen 91-150, vol 3 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1965), 24.

29 Mülhaupt, "Luthers Psalmen-Auslegung", 24.

30 Mülhaupt, "Luthers Psalmen-Auslegung, 26.

31 Burkard Waldis, Der Palter Jn Newe Gesangs weise vnd künstliche Reimen gebracht (Frankfurt: Egenolff, 1553), 166-167.

32 "The hellish sea puts up resistance, raving and raging; roaring terribly like the sea they cannot be calmed. One destroys the doctrine, the other murderously fights back. To wear down Christ and to drive him away from this world". Quite similar, Wither George, an English poet in the 17 century, mentions in his short introduction to Ps 93 that singing this psalm will offer comfort against the rage of the devil and his members. George Wither, The Psalmes of David translated into lyrick-verse, according to the scope, of the original (Amsterdam: van Breughel, 1632), 175.

33 Tucker and Grant also emphasise the threatening aspect of the waters. However, they reckon with ambivalent readings even for the original readers. Thus the rivers and the sea could literally point to the destructive power of water, metaphorically they could refer to enemies or mythical forces. Cf. W. Dennis Tucker Jr. and Jamie A. Grant, Psalms, Volume 2 (NIVAC; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2018), 378.

34 E.g., Delitzsch and Kirkpatrick equate the rivers with world-powers pointing to the comparisons of Assyria with the Euphrates (Isa 8:7-8) and the Nile with Egypt (Jer 46:7-8). Delitzsch, Psalmen, 645; Alexander F. Kirkpatrick, The Book of Psalms. Books IV and V (The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901), 564-565. Cf. also Arnold B. Ehrlich, Die Psalmen (Berlin: Poppelauer, 1905), 225; Friedrich Baethgen, Die Psalmen (HKAT II/2; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1892), 292.

35 The connection to creation, however, has also been seen in the Midrash on the Psalms. It is ascribed to R. Berechiah speaking in the name of Ben Azzai and Ben Zoma, that the floods lifting up points to the waters coming before the throne of glory, before the earth was created (Gen 1:2). Braude, Midrash, 126.

36 Cf. e.g., Hermann Gunkel, Die Psalmen (GHKAT II/2; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1926), 411.

37 Oswald Loretz, Ugarit-Texte und Thronbesteigungspsalmen: Die Metamorphose des Regenspenders Baal-Jahwe (Ps 24,7-10; 29; 47; 93; 95 - 100 sowie Ps 77,17-20; 114) (UBL 7; Münster: Ugarit Verlag, 1988), 290-99. Some commentators try to put a distance between the polytheistic images from the ANE and the OT texts, emphasising that Ps 93 only makes use of the metaphorical language, so e.g., Willy Stärk, Lyrik (Psalmen, Hoheslied und Verwandtes) (SAT III/1; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1911), Helmut Lamparter, Das Buch der Psalmen II. Psalm 73-150 (BAT 15; Stuttgart: Calwer, 1990), 134; Artur Weiser, Die Psalmen II: Psalm 61-150 (10ed.; ATD 15; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1987), 424; Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalmen 60-150 (2 ed.; BKAT 15/2; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1961), 649. In a similar way, Alter notes, that "the mythology is no more than a distant memory". Robert Alter, The Book of Psalms (New York, NY: Norton, 2007), 329.

38 Jörg Jeremias, Das Königtum Gottes in den Psalmen: Israels Begegnung mit dem kanaanäischen Mythos in den Jahwe-König Psalmen (FRLANT 141; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1987), 15-29.

39 Dennis Sylva, "The Rising נהרות of Psalm 93: Chaotic Order," JSOT 36 (2012): 471-482 (474); cf. also Bernd Janowski, "Das Königtum Gottes in den Psalmen. Bemerkungen zu einem Gesamtentwurf," ZThK 86 (1989): 389-454 (409); and Bauks, "Chaos," 431-464.

40 For a discussion on the structure of Ps 93, see e.g., Human, "Psalm 93," 157; Dennis Pardee, "The Poetic Structure of Psalm 93," SEL 5 (1988): 163-170 (169); Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalmen 51-100, 645-646; Mosis, "Ströme erheben," 223-255.

41 V. 3 unfolds as poetic parallelism following the scheme ABC-ABD-ABE. Benjamin Segal, "'Above the Thunder of the Mighty Waters': Ps 93," CJud 58 (2005): 59-65 (62).

42 Only in Ps 93 the rivers are attributed the action of נשא Usually, נשא qal, "to lift up, to bear, to carry away," does not have a reflexive meaning like the niphal. This image does hardly refer to the rising of the waters, but points to something they lift up or carry (away). Fritz Stolz, "נש ns' aufheben, tragen," THAT2:109-117.

43 The frequently used expression "to lift one's voice" occurs in different situations, indicating that somebody is going to make a sound. Most often it is the sound of weeping (cf. Gen 21:16; 27:38; 29:11; Judg 21:2; 1 Sam 24:17; 2 Sam 13:36; Job 2:12; Ruth 1:9, 14); it can also introduce the sound of jubilation (Isa 24:14; 52:8), or provocation (2 Kgs 19:22; Isa 37:23).

44 דכי occurs only here, but all words from the root דכה / דכא refer to crushing, oppressing.

45 There are only a few texts presenting the rivers as a threat. On the one hand, the flooding of the rivers pose a threat: God uses the rivers' waters as a weapon (e.g., Isa 8:7; Nah 2:7); Jonah mentions in his prayer that God has thrown him into the sea, where the rivers surrounded him (Jonah 2:4). On the other hand, rivers running dry are equally threatening (e.g., Isa 19:5-6; 42:15, 27; 50:2; Nah 1:4), and may also be considered as a sign of God's power (e.g., Pss 66:6; 74:15; 107:33).

46 The threefold repetition of the verb NWl uses perfect tense twice, but switches to imperfect in the last line.

47 In contrast to the voice of the great waters, their noise (שאון) rather points to a destructive event (e.g., Jer 51:55; Isa 17:12).

48 The "mighty waters" are seldom personified, they usually do not act on their own, but rather God acts on them. When, for example, the mighty waters are mentioned in Exod 15:10 or Hab 3:15, God makes use of these waters (cf. also Ezek 26:19).

49 See Geller, "Myth and Syntax," 326-327.

50 Friedhelm Hartenstein, Die Unzugänglichkeit Gottes im Heiligtum. Jesaja 6 und der Wohnort JHWHs in der Jerusalemer Kulttradition (wMANT 75; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1997), 47.

51 Segal, "Above the Thunder," 63.

52 This aspect is, for example, pointed out by Briggs and Briggs. They interpret vv. 3-4 as graphic descriptions of the majesty of the sea in a great storm that "is to be interpreted as real and not as symbolical of armies of mighty foes" (Briggs & Briggs, Psalms), 302.

53 Schegg, e.g., introduces an aesthetic point of view, emphasising the impressive beauty of a storming sea. Schegg, Die Psalmen, 305.

54 Helen G. Jefferson, "Psalm 93," JBL 71 (1952): 155-160 (156).

55 Human, "Psalm 93," 161.

56 Janowski calls this form of presentation "Stilform der behobenen Krise," where YHWH, like the sun god Re, is depicted as conqueror, who already has defeated all threatening forces (Janowski, "Das Königtum Gottes," 409). Bauks takes this idea even further and deprives the chaotic forces of their power: "Anstatt dem Chaos eine Eigenmächtigkeit zuzubilligen, wird es lediglich zur Herausstellung göttlicher Größe und Macht als Negativfolie benutzt. Es geht nicht um die Qualität, sondern um die Verhältnisbestimmung, nicht um Chaos als Gegenkraft, sondern um eine rhetorische Figur" (Bauks, "Chaos," 435). Although this reading puts a premature identification of the water images with the chaotic forces in perspective, it also diminishes the fascinating aspect of the waters' power and majesty.

Prof Susanne Gillmayr-Bucher, Department of Biblical Studies, Catholic Private University Linz, Austria, Email s.gillmayr-bucher@ku-linz.at. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5200-5020.