Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.32 n.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n2a6

ARTICLES

W. Dennis Tucker Jr

Baylor University

ABSTRACT

Similar to other psalms in Book IV of the Psalter (Pss 90-106), Psalm 92 responds to the events of the exile. In a psalm that contains elements of a hymn and a thanksgiving psalm as well as elements associated with the wisdom tradition, the psalmist confesses that the world remains well-ordered under Yahweh's rule despite recent events that might suggest otherwise. The very structure of the psalm itself implies a certain sense of orderliness and this sense of orderliness is addressed more explicitly by invoking particular themes (i.e., creation) and employing certain conceptual metaphors.

Keywords: Psalm 92, exile, world order, Psalter book IV (Pss 90106), wisdom (tradition).

A INTRODUCTION

With the fall of the Judean monarchy and the decimation of Jerusalem, the central tenets of Zion theology strained under the weight of historical and social realities. The official Jerusalemite theology of king and temple which had crafted a worldview that signalled security and prosperity, now seemed vacuous in the wake of the Babylonian onslaught. The world, once thought predictable and ordered, now seemed anything but that.

Much of the literature produced during and after the exile sought to make sense of the inexplicable, and in many ways, to answer the questions that no doubt plagued the community.1 This is no less true with Israel's cultic literature. As many have argued, Book IV of the Psalter appears to function as a response to the loss of the Davidic monarchy, as rehearsed in Ps 89. This paper gives attention to one of the responses articulated in Book IV (Ps 92). The chief question that lingers beneath the surface of this particular psalm is not "Does Yahweh rule," but "Is the world in which humans live and over which God rules rightly ordered?"2 This study contends that Ps 92 is a hymnic confession on the orderliness of the world under God's divine rule. Admittedly, the discord and disorder associated with the exile suggested that the world was anything but well ordered, yet the psalmist pushed back against any such conclusions, opting instead to put trust in a divinely ordered world.

Psalm 92, in its totality, conveys the sense of an ordered world. To support this claim, the genre and structure of the psalm will be considered first, followed by a consideration of the creation themes present in the first half of the psalm. The conceptual metaphors employed in vv. 8 and 13-15 lend additional support to the psalm's claim. The implications of the formal theological claims in the psalm (i.e., claims about Yahweh) will be considered last as they serve to frame the psalm, both literally and figuratively.

B GENRE AND STRUCTURE

Form-critically, Gunkel contended that Psalm 92 was an individual thanksgiving psalm that also included elements associated with the wisdom tradition.3 More recently, Hossfeld and Zenger have expanded Gunkel's initial assessment by suggesting that the psalm incorporates elements of the hymn as well as those of a thanksgiving psalm and "the Wisdom didactic poem."4 Similar to Hossfeld and Zenger, Claudia Sticher argues for the presence of all three elements in the psalm and attempts a diachronic reconstruction of the psalm's formation.5 According to Sticher, the individual psalm of thanksgiving is raised to the form of a wisdom doctrine in general and finally, crafted into its hymnic form.6 In its present form, wisdom elements notwithstanding, there is an "overall hymnic tendency" in the psalm.7

This "hymnic tendency" of the psalm is made explicit in the opening line (v. 2a) with the verb ידה. Some English translations (NRSV; NIV) render the verb "give thanks," but the verb can also mean "confess," as in "profess," and frequently carries that connotation in those psalms that rehearse Yahweh's great acts of deliverance (e.g., 105:1; 106:1).8 The latter meaning is clearly in view in the LXX, with ידה rendered as έξομολογεω, "to confess." This rendering of the term aligns better with vv. 2b and 3a. In those two lines, the psalmist "sings praises" (v. 2b) and declares God's steadfast love (v. 3a).9 In other words, the psalmist confesses or professes something about Yahweh. Understood this way, the psalm might best be understood as a "hymnic confession with a didactic aspect," as Goldingay has opined, but even then, the elements must be understood in that order.10

Although terms and ideas traditionally labelled as "wisdom" appear in the psalm, they are used in service to the psalm's larger hymnic tendency, and this proves suggestive for determining the theological trajectory of the psalm itself. Göran Eidevall has contended that whereas sapiential instruction focuses on processes of development and personal growth, hymns and thanksgiving psalms "tend to be more concerned with security and stability."11 Although the more sapiential portions of Ps 92 could be construed as focused on "development and personal growth," to use Eidevall's terms, they actually serve to reinforce the psalmist's larger claim concerning "stability" and the orderliness of the world under divine rule.

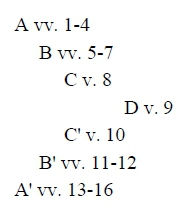

Beyond the genre of the psalm itself, even the structure of the psalm points towards a similar emphasis on order. Marvin Tate, followed by many subsequent interpreters, have pointed to the chiastic pattern in the psalm, an arrangement first posited by Richard M. Davidson:12

Verse 9 stands at the centre of the psalm with two triplets (i.e., tri-colons; vv. 8, 10) flanking the central verse.13 The rejoicing and celebration in vv. 5-7 (B) appears once more in vv. 11-12 (B'). Tate contends that "the future of the righteous in vv. 13-16 (A') complements the testimony of praise in vv. 1-4 (A)."14While Davidson and Tate are no doubt correct that v. 9 stands at the centre of the psalm (see below), the remaining features of the concentric pattern seem forced, particularly A and A', but to a lesser degree also B and B', thus calling into question the chiastic pattern identified by Davidson. Hossfeld and Zenger do not abandon the chiastic features of the psalm entirely, opting instead for two embedded concentric patterns. Vv. 2 and 4 serve to create a small chiastic arrangement with v. 3 standing at the centre, and in the hymn's main section (vv. 5-12), their proposed arrangement largely follows Davidson's arrangement above for BCDC'B'. They suggest that vv. 13-16 function as a wisdom conclusion, with possible allusions to the introduction (e.g., נגד, vv. 2, 16).15 In both instances, the proposed chiastic patterns seem forced with little explanatory power, beyond the recognition of v. 9 and its placement in the psalm.

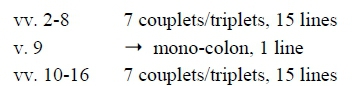

Rather than focusing on possible chiastic structures associated with the psalm, there are other quantitative structural aspects that are worth noting. There are fifteen couplets/triplets present in Ps 92, with 31 lines.16 At the centre of the psalm stands v. 9, which appears as a single line (i.e., mono-colon). Thus, the structure of the psalm could be construed as:

The affirmation in v. 9, "But you are the Exalted One, O LORD," functions as the semantic, rhetorical and structural centre of the psalm, with a triplet (tri-colon) appearing on either side to reinforce the centrality of the verse and its claims.17

This organizational structure of the psalm is further verified at the word level. In vv. 2-8, there are 52 words in total, a total that is matched in vv. 10-16. As Bazak and others have suggested, the number 52 is 2 x 26, with the latter number symbolically representing the divine name.18 What is more, the divine name appears repeatedly throughout the psalm, 7 times to be exact (vv. 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 14, 16), with the middle occurrence of the divine name in verse 9.19

Thus, from beginning to end, Ps 92 reflects a careful work that demonstrates considerable structure and order. The seven couplets and the heptad of the divine name likely allude to images of creation, making the psalm an appropriate selection for Sabbath usage (v. 1). At the centre of the psalm stands the central confession concerning Yahweh, the one who brings all things to order and holds them to the same.

C CREATION IMAGERY INVOKED

Beyond the orderliness of the psalm's structure, the opening lines of the psalm repeatedly invoke language and imagery associated with Israel larger creation tradition. The psalm begins טוֹב לְהֹדוֹת לַיהוָה "It is good to profess Yahweh." A variant form of this line appears later in the Psalter in Pss 106:1; 107:1; 118:1; 136:1: הוֹדוּ לַיהוָה כִּי־טוֹבה, "Give thanks to Yahweh because he is good." Frequently these texts are referenced in conjunction with Ps 92 due to the operative verb (ידה) in each and the presence of טוֹב.20 Yet upon closer analysis, the two lines make different claims. In Pss 106; 107; 118 and 136, the word טוֹב appears in a subordinate null copula (i.e., verbless) clause with a null subject following the imperative + adjunct, but because the clause is subordinate, the subject is easy to infer (i.e., Yahweh). In those instances, טוֹב does little to recall Gen 1. In Ps 92:2, however, טוֹב also appears in a null copula clause modified by the infinitive + adjunct לְהֹדוֹת לַיהוָה. In this instance, however, the subject of the null copula clause is an expletive subject (i.e., "it"), thus should be rendered "it is good."21 This initial clause in the line evokes the repeated language of Gen 1.22

The null copula phrase "it is good (טוֹב)" on its own, however, is not sufficient evidence that creation imagery is at work in Ps 92; it is only suggestive. The additional language in the subsequent verses, however, appears to confirm that creation imagery plays an important role in the psalm.23 In v. 5b, the psalmist refers to the מַעֲשֵי יָדֶיךָ, "works of your hands."24 Elsewhere in the Psalter, the "works of the hands" of God refer to creation more generally. In Ps 8:6, for example, humans are given dominion (משׁל) over the מַעֲשֵי יָדֶיךָ, "works of your hands," over all of creation (vv. 8-9). Later in Book IV, the psalmist confesses,

In earlier times you established the earth,

the heavens are the works of your hands. (Ps 102:26).

And in Ps 19, another psalm with didactic intentions, the מַעֲשֵי יָדֶיךָ are mentioned in reference to the firmament (v. 2; רָקִּיע The focus on creation continues in v. 6a with the declaration

How great are your works, O LORD,

[How] very deep are your designs.

In verse 6a, the psalmist employs the stative verb גָדַל Although English translations render the line as though it were a null copula (verbless) clause, the presence of a stative verb is suggestive. Generally speaking, null copula clauses describe the status or state of something whereas verbal clauses are meant to represent an event. "The former is rigid, a non-activity; the latter an activity, a movement, a happening, a deed."25 Waltke and O'Connor explain further that

English and most other European languages cannot formally distinguish the relevant notions because for both notions they must employ the verb "to be" (or the like) and allow contextual considerations to indicate whether "be" is a "dummy" verb with a predicate adjective or a true verb. Speakers of English language can appreciate the difference between the notions of state and event by juxtaposing "he is alive" with "he lives."

The distinction is worth noting in v. 6a. The psalmist is doing more than making a declaration that God's creative act was "great" and he is certainly doing more than offering an assessment or generalization, i.e. "creation is great." Rather the psalmist is confessing to the on-going greatness of God's creative work, disruptive events notwithstanding.26

Line b in v. 6 extends this reading of 6a, further extolling God's work in creation. Some English translations render v. 6b as "your thoughts are very deep" (NRSV) or "how profound are your thoughts" (NIV). To do so, however, strains the connection between line a and line b. The language in line b is better understood as referring to the created order, or better yet, the ordered creation.

The operative noun in the line, מַחְשְׁבֹתֶיךָ, is frequently rendered as "thoughts," but it can mean "plan, design." Thus, the psalmist is not lauding the thoughts of God as much as he is God's design for creation. This line of reasoning is reinforced with another stative verb, עָמַק, "to be deep." Typically, interpreters have assumed the verb refers to the profundity of God's thought. Yet elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, the verb often has a strong spatial orientation. For example, Isa 7:11 reads, "Ask a sign of Yahweh your God; let it be as deep as Sheol or high as the heavens." Other such instances capture a similar spatial sense (cf. Isa 30:33; Jer 49:8, 30; Hos 9:9). Clearer still is the adjectival form of the root, which refers to the depths of something (cf. Lev 13:3; Job 11:8). Thus, in verse 6b, the psalmist is not celebrating the deep thoughts of God but instead declaring that God's plans, God's design for creation, are deeply embedded in the created order. Similar to 6a, the psalmist is confessing to the on-going design of God's creation, disruptive events notwithstanding.

The opening verses of Ps 92 invoke images of creation, as suggested above. Through subtle allusions (i.e., טוֹב) and more explicit references to God's creative work (i.e., מַעֲשֵי יָדֶיךָ), the psalmist recalls the language and imagery of creation. And in so doing, the psalmist confesses that the world remains well ordered, operating according to the deep designs of its Creator.

D CONCEPTUAL METAPHORS

The theme of an ordered world is reinforced in vv. 8 and 13-15 with the aid of conceptual metaphors. Metaphors necessarily require two conceptual domains with the content from one domain (i.e., the source domain) being mapped onto a second (i.e., the target domain). In Ps 92, the source domains are plants; each domain represents a coherent cluster of knowledge derived from embodied experience, as will be considered below.27 These source domains are mapped onto the same target domain, "people," thus yielding the following conceptual metaphor: PEOPLE ARE PLANTS. By employing this conceptual metaphor, the psalmist contrasts the fate of the wicked from that of the righteous, thereby confirming the orderliness of the world.

1 Plants

In the Hebrew Bible, vegetation metaphors are plentiful.28 At times, metaphors such as grass are used more generally to make an anthropological statement concerning the transience of human existence, as reflected in Isa 40:6b

All people are grass (חָצִּיר);

and their goodness is like the flower of the field.

Grass served as an apt metaphor (source domain) for humans and the human condition because grass "was above all perishable, prone to dry up and wither away."29 Similar sentiments about the human condition are found in the Psalter as well. For example, in Ps 103, the psalmist observes

As for humans, their days are like grass (חָצִּיר)

like the flower of the field, they flourish (צוּץ).

When the wind passes over it, it disappears,

and one can no longer recognize its place. (vv. 15-16)30

Similar terms appear in Ps 90:5-6: humans are חָצִּיר that flourish (צוּץ). In these instances, the association of human life with vegetation, especially grass, remains relatively value-neutral and all-encompassing in scope: "All people are grass" (Isa 40:6b). In these instances, to be grass is neither good nor bad; it is to be human, and to be human implies a certain sense of ephemerality. Thus, a subset of PEOPLE ARE PLANTS is PEOPLE ARE GRASS.

At other times, however, the source domains are mapped on to various targets with the intent of making a value judgment. This is clearly the case with the wicked. In the opening lines of Ps 37, the psalmist encourages himself not to fret over the wicked and evildoers

For they will fade away like the grass

and wither like green vegetation. (v. 2)

As noted above, Isa 40 and Ps 103 adopt the PEOPLE ARE PLANTS metaphor with the perishability of plants being mapped onto people to reflect the human condition. Ps 37 maps the same source domain (PLANTS) on to PEOPLE, but more specifically, the wicked. This creates a subset of the original conceptual metaphor, resulting in the WICKED ARE GRASS. Although PEOPLE ARE GRASS refers to human transience, the conceptual metaphor the WICKED ARE GRASS is meant to say more; they will not endure.

2 Psalm 92:8

Psalm 92, however, complicates the conceptual metaphor even further. Similar to Ps 37, Ps 92 maps plants onto the target domain, i.e., the wicked and evildoers.31 Yet as Travis Bott notes, conceptual metaphors "often involve multiple mappings on the basis of perceived similarities between the two domains."32 This is true of the PEOPLE ARE PLANTS conceptual metaphor in Ps 92. Ps 92:8 reads

Even though the wicked sprout (פרח) like grass

and the workers of iniquity flourish (צוּץ),

they will be destroyed forever.

In lines 8a and b, PLANTS are mapped onto the WICKED, similar to Ps 37, but the connotation expressed in the first two lines is suggestive. The verb in line 8b, צוּץ ("flourish") appears both in Pss 90:6 and 103:15 (in reference to humanity more generally), but unlike those two psalms, the verb פרח also appears. The latter term typically refers to something like sprouting, or budding out, with an implied meaning of "fruitfulness."33 Thus in Ps 92, the wicked and workers of iniquity are indeed compared to grass, but here with an emphasis on their vigorous growth ("sprout," "flourish").34 As noted above the WICKED ARE GRASS metaphor functions as a subset of the PEOPLE ARE PLANTS metaphor. What is striking in Ps 92:8, however, is that the negative connotation expressed in Ps 37:2 appears to be reconfigured. In Ps 92, the wicked and workers of iniquity appear to be prosperous, a claim that would subvert any sense of order in the world, as it calls into the question the validity of Tun-Ergehen-Zusammenhang construct.35

The apparent prosperity of the wicked suggested in v. 8a-b, however, is checked by the claim in line 8c: "they will be destroyed forever."36 Admittedly the rendering of the final line in this triplet (tricolon) has proved challenging, particularly due to the presence of לְהִּשָמְדָם in a null copula (i.e., verbless clause). While ל + an infinitive construct quite often signals a purpose, result or temporal (subordinate) clause, such a construction can also create a "modal sense," especially when embedded in a verbless clause (as in v. 8c) and when the subject appears as a pronominal suffix. In this construction, the verb implies necessity or obligation (IBHS § 36.2.3f; JM §124.l). Understood this way, v. 8c signals that the flourishing of the wicked necessarily ends with their destruction. Although the prosperity (i.e., the "flourishing") of the wicked appears to stand in contrast to earlier claims concerning Yahweh's governance of the world (v. 3), the fate of the wicked outlined in verse 8c affirms the orderliness of the world. The flourishing of the wicked followed by their downfall ultimately bears witness to a world ordered well under Yahweh's just governance.

3 Psalm 92:13-15

The PEOPLE AS PLANTS metaphor also appears later in the psalm in reference to the righteous. Bott's claim referenced above that conceptual metaphors can contain "multiple mappings" based on "perceived similarities between the two domains" is also evident in vv. 13-15.37 Strictly speaking, v. 13 includes two similes:

The righteous will flourish like a palm tree;

like the cedars of Lebanon, they will grow high.

Thus, even as the WICKED ARE GRASS is a subset of the conceptual

domain PEOPLE AS PLANTS, so too is the RIGHTEOUS ARE TREES

metaphor. This conceptual metaphor is by no means unique to Ps 92, with two other parallels in the Psalter (Pss 1:3; 52:10) and one outside of the Psalter (Jer 17:7-8). The simplest formulation of this conceptual metaphor appears in Ps 52:10.38

I am like a green (רַעֲנָן) olive tree

in the house of God.

Even in this abbreviated formulation, there are multiple mappings of the source domain (tree) onto the target domain (the righteous). In this verse, both descriptive ("green," i.e., full of life) and spatial elements ("house of God") are mapped onto the target. These two elements also appear in the other iterations of this conceptual metaphor.

Likewise, the use of the conceptual metaphor RIGHTEOUS ARE TREES in Ps 1:3 and Jer 17:7-8 includes multiple mappings.39

He [the righteous] is like a tree (fy)

planted by streams of water

that yields its fruit in its season,

and its leaf does not wither.

In all that he does he prospers. (Ps 1:3)

Blessed are those who trust in Yahweh

whose trust is in Yahweh.

They shall be like a tree (עֵץ) planted by the water,

sending forth its roots by the stream.

It shall not fear when heat comes

and its leaves shall stay green (רַעֲנָן);

in the year of drought, it is not anxious,

and it does not cease to bear fruit. (Jer 17:7-8)

Similar to Ps 52:10, a tree (but here עֵץ) functions as the source domain, but the descriptive elements are considerably expanded. Beyond simply being "green" (רַעֲנָן), the tree's fructifying capacity is reinforced, with the declaration even "in the year of drought" it bears fruit. In Ps 1:3, the psalmist declares that the tree "yields its fruit in season." Janowski and Hartenstein note that in wisdom and wisdom influenced texts, "there are elements of a doctrine of the right time."40 Interestingly, this doctrine of "right time" does not, however, appear in the other texts under consideration (Pss 52:10; 92:13-15; Jer 17:7-8), perhaps providing some diachronic clues for understanding Ps 1.41

Interestingly, the "house of God" in Ps 52:10, or some similar reference, is not mentioned specifically in either text. This could signal that perhaps the spatial mapping has shifted or even that the spatial elements are actually not part of the conceptual metaphor after all. That said, the reference to "streams" in both texts is suggestive, especially the use of פֶלֶג in Ps 1:3. The noun פֶלֶג also appears in Pss 46:5 and 65:10 in reference to the waters that issue forth from the temple, reflecting the larger ANE idea that the earth's waters originated from the divine mountain.42 For similar a construal of פֶלֶג with the waters of paradise, see Isa 30:25 and 32:2. In other words, the reference to streams in Ps 1, and likely in Jer 17, invokes a much larger range of ideas. The language of "streams" appears to function as a metonym (PART FOR WHOLE) that invokes the temple complex. The capacity for the righteous to bear fruit is contingent upon their "nearness to the life-giving God of Zion," and that nearness is most fully experienced on the divine mountain.43

Beyond these parallels within the Hebrew Bible, interpreters often note the similarities with the Instruction of Amenemope:

As for the heated man of the temple,

He is like a tree growing in the open.

In the completion of a moment (comes) its loss of foliage,

And its end is reached in the shipyards;

(Or) it is floated far from its place,

And the flame is its burial shroud.

(But) the truly silent man holds himself apart.

He is like a tree growing in a garden.

It flourishes and doubles its yield;

It stands before its lord.

Its fruit is sweet; its shade pleasant;

And its end is reached in the garden. (4.6.1-12)44

Similar to the texts mentioned above, the righteous one ("silent man") is compared to a tree.45 Like the other uses of the RIGHTEOUS ARE TREES metaphor, the tree's capacity to bear fruit is mapped on to the target domain. The reference to the temple in the opening line, as well as the subsequent references to the garden, supply the text with strong cultic overtones.46 Moreover, the melding of temple imagery with garden imagery is meant to invoke paradisiacal imagery associated with the place of the gods, a motif that appears most clearly in Ps 92.

In all four texts above, the metaphor RIGHTEOUS ARE TREES can be reduced to two qualities: one descriptive, the other spatial.47 Descriptively, the righteous are flourishing trees that bear fruit, and spatially, the trees are located within the temple of the gods. In Ps 92, however, the features of this conceptual metaphor are extended, or to be more precise, doubled. There are two trees mentioned and two references to their verdant qualities and fructifying capacity.48 These descriptive qualities frame the spatial qualities (two references to divine abode), creating something of a small chiasm.

The righteous will bud out like a palm tree

as the cedars of Lebanon, they will grow high.

They have been transplanted in the house of the LORD,

in the courts of our God, they will flourish.

In old age, they will still bear fruit;

they will be full of sap and green.

The spatial references in this section of the psalm coupled with the descriptive qualities are clearly meant to invoke images of the paradisiacal mountain of God, the dwelling place of the divine king in the ancient Near East.49This ideology reflects one of the fundamental themes associated with Jerusalem's temple theology.50 The temple functions as the divine throne, and as Janowski explains "it marks the place where, according to the vertical world view, the axis mundi runs and connects height (dwelling place of God) and depth (environment of humans). This gives the whole world strength (Festigkeit) and stability."51 Thus this overt reference to the temple/paradisiacal mountain accords well with the underlying theme of order that permeates the entire psalm.52

To return to Ps 92, the righteous one is compared to a tree that enjoys a long life of being fruitful. What differentiates the final result from the grass, however, is not merely an ontological difference, so to speak (i.e., grass versus a tree); it is because the Divine King, in whose courts the righteous one abides, ensures this good end.53 The righteous will bear fruit well into old age (v. 15) and the wicked will be destroyed forever (v. 8c) because of the one who "gives the whole world strength (Festigkeit) and stability." The location, and more specifically, the one who inhabits that location, is the guarantor of a stable world order.

E THE GUARANTOR OF ORDER

Throughout Psalm 92, the psalmist has confessed to an ordered world by drawing upon creation themes and pregnant conceptual metaphors, but also by structuring the psalm in such a way as to give evidence of that order. This is no less true with the use of divine names and appellations in this psalm. As noted above, the divine name, "Yahweh," appears 7 times, with the confession in v. 9 serving as something of a fulcrum: וְאַתָה מָרוֹם לְעֹלָם יְהוָה. In this null copula clause, מָרוֹם functions as a complement (accusative of place), "you are on high."54 Although the basic meaning of מָרוֹם is "height," the term functions as a synonym for the heavens where God is enthroned and from whence God rules over his creation (Pss 93:2-4; 102:20; 144:7; Isa 32:15; 33:5-6; 57:15-21).55 Yet as Tate suggests, "the conceptual field of מָרוֹם is undoubtedly inclusive of the idea of the cosmic mountain which is the dwelling place of deity."56 Thus the confession that Yahweh is "on high" invokes the very notion of an axis mundi, a place where the heavenly abode and the cosmic mountain intersect. But this spatial reference also carries with it theological import, as suggested above. To declare that Yahweh is מָרוֹם is to make an affirmation about who, in fact, governs the world. One cannot be מָרוֹם and not govern the world, and one cannot govern the world without being מָרוֹם. To declare that Yahweh reigns on high is to confess Yahweh's orderly and just governance of the world.

As a complement to this central confession, the psalm opens and closes with additional titles that contribute to the larger theme. In v. 2, the psalmist employs the appellation עֶלְיוֹן in reference to Yahweh.57 This title frequently refers to Yahweh's cosmic rule: עֶלְיוֹן is the מֶלֶךְ גָדוֹל עַל־כָל־הָאָרֶץ 58 And though עֶלְיוֹן rules in the heavens, he is also associated with Mount Zion, the cosmic mountain:

There is a river who streams make glad the city of God, the holy place of עֶלְיוֹן. (Ps 46:5)

This confession continues in the final verse of the psalm with another conceptual metaphor: YAHWEH IS A ROCK. To refer to Yahweh as a "rock" צוּר however, means far more than simply mapping generic elements of the source domain ("rock") on to the target domain (i.e., Yahweh), although certainly there are residual elements that likely carry over (e. g., shelter, protection). The particular mapping of this metaphor in the Hebrew Bible derives from "the adoption of the broadly attested idea of YHWH as resident on Zion, the mythical 'primeval rock'."59 Thus, the shelter and protection provided by Yahweh is associated with the cosmic mountain. This connection between the metaphor and Zion is clearly evident in Ps 61:

Lead me to the rock

that is higher than I am;

For you are my refuge,

a strong tower against the enemy.

Let me abide in your tent forever,

let me find refuge under the shelter of your wings. (vv. 3b-5)

The use of "rock" in conjunction with "your tent" and "shelter of your wings" confirms the association of rock with Zion. According to the psalmist, protection from the chaos of the world is secured by the unshakeable ruler who stands over all, yet remains fully present with his people on Zion (Pss 18:2-3; 62:7-8).60

In summary, at the beginning, middle and end of the psalm, titles and appellations for Yahweh appear. Their use, however, is not gratuitous or simply stylistic. Rather the psalmist employs all three in an effort to acknowledge the one who is the guarantor of an ordered world, a world that operates according to the deity's design and is governed by the same.

F CONCLUSION

Psalm 92 functions as a theological response to the exile by declaring that a seemingly disordered world remains ordered and governed by God "on high." The carefully structured format of the psalm complements the repeated references to creation. The appearance of 7 couplets/triplets on either side of the monocolon (v. 9) along with the heptad of the divine name is suggestive of creation/Sabbath themes. As noted above, the psalmist employs more overt creation language in an effort to make explicit what the psalm's structure can only communicate implicitly: the world remains ordered at the hands of its Creator.

The psalmist also considers the fate of the wicked and the righteous as evidence that a certain order remains in place: for the wicked, destruction, and for the righteous, full life. This fundamental order is grounded in the claims associated with temple theology, and in particular, the cosmic mountain. And the three titles employed for Yahweh in the psalm confirm that the one who inhabits the cosmic mountain is indeed the one who rules on high; the one who rules on high, Yahweh, is the guarantor of an ordered world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertz, Rainer. Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature: Studies in Biblical Literature 3. Translated by David Green. Atlanta; GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003. [ Links ]

Bazak, Joseph. "Numerical Devices in Biblical Poetry." Vetus Testamentum 38 (1988): 333-337. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853388x00067. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil. "Intertextuality and the Interpretation of Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 18 (2005): 503-520. [ Links ]

Bott, Travis J. "Figurative Enemies in the Psalms: a Cognitive-Linguistic Approach." Pages 74-106 in Gegner im Gebet: Studien zu Feindschaft und Entfeindung im Buch der Psalmen. Edited by Kathrin Liess and Johannes Schocks. Herders Biblische Studien 91. Freiburg: Herder, 2018. [ Links ]

Brown, William P. Seeing the Psalms: A Theology of Metaphor. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2002. [ Links ]

Calvin, John. Commentary on the Book of Psalms, vol. 2. Translated by James Anderson. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009. [ Links ]

Creach, Jerome F. D. "Like a Tree Planted by the Temple Stream: The Portrait of the Righteous in Psalm 1:3." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999): 34-46. [ Links ]

Crystal, David. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed.; Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. [ Links ]

Davidson, Richard M. "The Sabbatic Chiastic Structure of Psalm 92." Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Chicago, IL, 18 November 1988 [unpublished]. [ Links ]

Dell, Katherine J. "'I Will Solve My Riddle to the Music of the Lyre' (Psalm xlix 4[5]): A Cultic Setting for Wisdom Psalms?" Vetus Testamentum 54 (2003): 445-458. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568533042650822. [ Links ]

de Vos, Christiane. "Es gibt mehr Felsen in Israel." Pages 1-11 in Metaphors in the Psalms. Edited by Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 231. Leuven: Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

Dobbs-Allsopp, Frederick W. On Biblical Poetry. Oxford: University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Eidevall, Göran. "Metaphorical Landscapes in the Psalter." Pages 13-22 in Metaphors in the Psalms. Edited by Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 231. Leuven: Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard. Psalms, Part 2 and Lamentations. Forms of Old Testament Literature 15. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. Psalms 90-150. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann. Introduction to the Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel. Translated by James D. Nogalski. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1998. [ Links ]

_. Die Psalmen. 5th ed.Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968. [ Links ]

Hallo, William W. and Younger, K. Lawson Jr., ed. The Context of Scripture. Vol. 1: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World. Leiden: Brill, 1997. [ Links ]

Holmstedt, Robert D. Ruth. Baylor Handbook on the Hebrew Bible. Waco, TX: Baylor, 2010. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank Lothar and Zenger, Erich. Psalms 2. Hermeneia. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2005. [ Links ]

Janowski, Bernd. "Der Ort des Lebens: Zur Kultsymbolik des Jerusalemer Tempels." Pages 207-243 in Der Nahe und der Ferne Gott. Edited by Bernd Janowski. Beiträge zur Theologie des Alten Testaments 5. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2014. [ Links ]

Janowski, Bernd and Friedhelm Hartenstein. Psalmen. Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament 15/1, Lieferung 1. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2012. [ Links ]

Keel, Othmar. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Translated by Timothy J. Hallett. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997. [ Links ]

Kövecses, Zoltán. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction. 2nd ed. Oxford: University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans Joachim. Psalms 60-150: A Commentary. Continental Commentaries. Translated by Hilton C. Oswald. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1993. [ Links ]

_. Theology of the Psalms. Continental Commentaries. Translated by Keith Crim. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1992. [ Links ]

Leuenberger, Martin. Konzeptionen des Königtums Gottes im Psalter: Untersuchungen zu Komposition und Redaktion der theokratischen Bücher IV-V im Psalter. Abhandlungen zur Theologie des Alten und Neuen Testaments 83. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag, 2004. [ Links ]

Loewenstamm, Samuel E. "The Expanded Colon, Reconsidered." Ugarit Forschungen 7 (1975): 261-264. [ Links ]

Mays, James L. Psalms. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1994. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, Sigmund. The Psalms in Israel's Worship. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1962. [ Links ]

Petrany, Catherine. Pedagogy, Prayer and Praise: The Wisdom of the Psalms and Psalter. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2/83. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015. [ Links ]

Pongratz-Leisten, Beate. Ina sulmi Irub: Die kulttopographische und ideologische Programmatik der akltu-Prozession in Babylonien und Assyrien im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Baghdader Forschungen 16. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1994. [ Links ]

Riede, Peter. "'Doch du erhöhtest wie einem Wildstier mein Horn': Zur Metaphorik in Psalm 92,11." Pages 209-216 in Metaphors in the Psalms. Edited by Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 231. Leuven: Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

Sarna, Nahum. "The Psalms for the Sabbath Day (Ps 92)." Journal of Biblical Literature 81 (1962): 155-168. https://doi.org/10.2307/3264751. [ Links ]

Saur, Markus. "Where Can Wisdom Be Found?: New Perspectives on the Wisdom Psalms." Pages 181-204 in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Worship. Edited by Mark R. Sneed. Ancient Israel and its Literature 23. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt173zmjp.12. [ Links ]

Schnocks, Johannes. "Human Transience, Justice, and Mercy: Psalm 103." Pages 7786 in The Psalter as Witness: Theology, Poetry and Genre. Edited by W. Dennis Tucker, Jr. and William H. Bellinger, Jr. Waco, TX: Baylor, 2017. [ Links ]

Schmid, Konrad. "Himmelsgott, Weltgott und Schöpfer: 'Gott' und der 'Himmel' in der Literatur der Zeit des Zweiten Tempels." Pages 111-146 in Der Himmel. Jahrbuch für Biblische Theologie 20. Edited by Martin Ebner and Irmtraud Fischer. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2005. [ Links ]

Shupak, Nili. "The Contribution of Egyptian Wisdom to the Study of Biblical Wisdom Literature." Pages 265-304 in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Worship. Edited by Mark R. Sneed. Ancient Israel and its Literature 23. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt173zmjp.16. [ Links ]

Sticher, Claudia. "'Die gottlosen gedeihen wie Gras': zu einigen Pflanzenmetaphern in den Psalmen. Eine kanonische Lektüre." Pages 251-268 in Metaphors in the Psalms. Edited by Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 231. Leuven: Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

Tate, Marvin E. Psalms 51-100. Word Biblical Commentary 20. Dallas, TX: Word, 1990. [ Links ]

Tucker, W. Dennis. Jr. Jonah: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text. Rev. and expand. Ed. Baylor Handbook on the Hebrew Bible. Waco, TX: Baylor, 2018. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1. Oudtestamentische Studien 63. Leiden: Brill, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004262799. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, William A., ed. New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1997. [ Links ]

Vernus, Pascal. Sagesses de l'Egypte pharaonique. 2nd ed. Arles: Actes Sudes, 2010. [ Links ]

Waltke, Bruce and O'Connor, Michael. Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. "'Dann wird er sein wie ein Baum ...' (Psalm 1, 3): Zu den Sprachbildern von Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 23 (2010): 406-426. [ Links ]

_. Werkbuch Psalmen II. Die Psalmen 73 bis 150. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2003. [ Links ]

Whybray, Roger N. The Intellectual Tradition in the Old Testament. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 135. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1974. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 2019/03/04

Peer reviewed: 2019/05/18

Accepted: 2019/07/18

1 On the literature associated with the exile, see Rainer Albertz, Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. (SBLStBL 3; trans. David Green; Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003).

2 John Calvin echoes this understanding of the psalm, explaining "that the great object of the psalmist is to allay that disquietude of mind which we are apt to feel under the disorder which reigns apparently in the affairs of this world" (Commentary on the Book of Psalms, vol. 2 [trans. James Anderson; Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009], 505).

3 Hermann Gunkel, Introduction to the Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel (trans. James D. Nogalski; Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1998), 297298.

4 Frank Lothar Hossfeld and Eric Zenger, Psalms 2 (trans. Linda M. Maloney; Hermeneia; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2005), 436. Similarly, see Peter Riede, "'Doch du erhöhtest wie einem Wildstier mein Horn'. Zur Metaphorik in Psalm 92, 11," in Metaphors in the Psalms (ed. Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn; BETL 231; Leuven: Peeters, 2010), 209-216. Although most interpreters label Ps 92 as a thanksgiving psalm, there are notable exceptions who classify the psalm as a wisdom psalm. See Roger N. Whybray, The Intellectual Tradition in the Old Testament (BZAW 135; Berlin: de Gruyter, 1974); James L. Mays, Psalms (IBC; Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1994); Katherine J. Dell, "'I Will Solve My Riddle to the Music of the Lyre' (Psalm xlix 4[5]): A Cultic Setting for Wisdom Psalms?", VT (2003): 445-458. Martin Leuenberger, in his analysis of Psalm 90-92 as a compositional unit, contends that all three psalms contain wisdom elements. He labels Ps 92 a "weisheitliches Danklied mit hymnischen Elementen." See his Konzeptionen des Königtums Gottes im Psalter: Untersuchungen zu Komposition und Redaktion der theokratischen Bücher IV-Vim Psalter (AThANT 83; Zürich: Theologischer Verlag, 2004), 132-138.

5 "'Die Gottlosen gedeihen wie Gras': zu einigen Pflanzenmetaphoren in den Psalmen. Eine kanonische Lektüre," in Metaphors in the Psalms (ed. Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn; BETL 231; Leuven: Peeters, 2010), 251-268.

6 Ibid., 256. Hossfeld and Zenger resist a similar diachronic assessment, preferring instead to "maintain the three perspectives in their tension filled layering upon one another" (Psalms 2, 436).

7 Hossfeld, and Zenger, Psalms 2, 436.

8 Hossfeld and Zenger contend that the phrase הֹדוּ לַיהוָה likely served in "post-exilic theology as a kind of short formula for liturgy as a response to God's saving acts" (Psalms 2, 435). Cf. 1 Chr 16:8.

9 Cf. Isa 12:4; 38:19.

10 John Goldingay, Psalms 90-150 (BCOTWP; Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 53.

11 "Metaphorical Landscapes in the Psalter," in Metaphors in the Psalms (ed. Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn; BETL 231; Leuven: Peeters, 2010), 19. In his analysis of "learned psalmography," Sigmund Mowinckel noted the presence of wisdom elements in thanksgiving psalms/hymns, and like Eidevall, suggested that such psalms may be designed to address issues of suffering (The Psalms in Israel's Worship [Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1962], 2:105-106). Although Ps 92 does not appear to be addressing suffering in a manner similar to Ps 73, it does appear to be addressing existential concerns.

12 Richard M. Davidson, "The Sabbatic Chiastic Structure of Psalm 92," (paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Chicago, IL, 18 November 1988). See Marvin E. Tate, Psalms 51-100 (WBC 20; Dallas. TX: Word, 1990), 464.

13 The terminology used to identify the various elements within Hebrew poetry remains fluid, without universal adoption of one system of labels. Following Frederick W. Dobbs-Allsopp, the levels of Hebrew poetry referenced here include: Stanza > Strophe > Couplet (Triplet) > Line > Word (On Biblical Poetry [Oxford: University Press, 2015], 73-94). See also, W. Dennis Tucker, Jr., Jonah: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text (rev. and expand. ed.; BHHB; Waco, TX: Baylor, 2018).

14 Psalms 51-100, 464.

15 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 436. Interestingly, both Kraus, and earlier, Gunkel, simply divided psalm into two sections: the hymnic introduction (vv. 2-4) and the body of the poem (vv. 5-16). Unlike more recent interpreters, neither observed any chiastic structures in the psalm. See Hermann Gunkel, Die Psalmen (5 ed.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968), 408-410, and Hans Joachim Kraus, Psalms 60-150: A Commentary (CC; trans. Hilton C. Oswald; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1993), 227229.

16 In this count, vv. 8 and 10 are understood as triplets as expressed in the MT. Others have also argued the same for v. 12 (Pieter van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Poetry III [OTS 63; Leiden: Brill, 2014], 41), but that suggestion is rejected here in favour of a couplet.

17 Tate and Davidson as well as Hossfeld and Zenger likewise argue for the centrality of v. 9.

18 Joseph Bazak, "Numerical Devices in Biblical Poetry," VT 38 (1988): 333-337. See also, van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes, 41. Labuschagne argues that within v. 9 the term Diia functions as the "keyword of the meaningful centre of the poem as a whole." He suggests that the numerical value for Diiç is 52, precisely the number of words on either side of the key verse. Labuschagne, "Psalm 92," 4. https://www.labuschagne.nl/ps092.pdf (accessed February 2, 2019).

19 Nahum Sarna, "The Psalms for the Sabbath Day (Ps 92)," JBL 81 (1962): 167-168.

20 Erhard Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 2 and Lamentations (FOTL XV; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 169. Gerstenberger observes the phrase טוֹב לְהֹדוֹת לַיהוָה in Ps 92 "mirrors the well-known liturgical shout" in the subsequent psalms. For similar views, see also, Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 435; Goldingay, Psalms 90-150, 54.

21 For a similar construction, cf. Ruth 3:13. See Robert D. Holmstedt, Ruth (Baylor Handbook on the Hebrew Bible; Waco, TX: Baylor, 2010), 168. David Crystal, A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (6 ed.; Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008), 179.

22 Beat Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II. Die Psalmen 73 bis 150 (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2003), 129.

23 The language of morning and night in v. 3 is suggestive. The reference to בֹקֶר in v. 3 a and לֵילוֹת in v. 3b has generated considerable discussion, particularly given the disagreement in number, i.e., בֹקֶר is singular whereas לֵילוֹת is plural (the LXX resolves the matter by inserting the singular noun νύκτα in place of the plural). The simplest reading is to understand the phrase as a merism, regardless of the differentiation in number. Similar to the righteous person in Ps 1 who meditates upon torah day and night, the psalmist in this text intends to praise God morning and night, i.e., continually. Yet with the mention of morning and night(s), allusions to Gen 1 appear readily evident. Although the repeated refrain in Genesis 1, "it was evening and it was morning day X" employs the word, עֶרֶב and not לַיְלָה, references to לַיְלָה do appear later in Gen 1:5, 14, 16, 18 signalling it as part of the fixed order of creation.

24 Weber, Werkbuch Psalmen II, 129.

25 Bruce Waltke and Michael O'Connor, Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990), 434.

26 Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax, 434.

27 See Zoltán Kövecses, Metaphor: A Practical Introduction (2 ed.; Oxford: University Press, 2010), 4.

28 See Sticher, "'Die Gottlosen gedeihen wie Gras'," 251-268. William P. Brown, Seeing the Psalms: A Theology of Metaphor (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2002), 55-79.

29 Göran Eidevall, "Metaphorical Landscapes in the Psalms," 18.

30 Johannes Schnocks, "Human Transience, Justice, and Mercy: Psalm 103," in The Psalter as Witness: Theology, Poetry and Genre (ed. W. Dennis Tucker, Jr. and William H. Bellinger, Jr.; Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2017), 77-86.

31 Although the vocabulary used for the wicked (מְרֵעִּים) and evildoers (עַוְלָה עֹשֵי) in Ps 37 differs from the term in Ps 92 (רְשָׁעִּים and פֹעֲלֵי אָוֶן), they share a common semantic domain.

32 Travis J. Bott, "Figurative Enemies in the Psalms: A Cognitive-Linguistic Approach," in Gegner im Gebet: Studien zu Feindschaft undEntfeindung im Buch der Psalmen (eds. Kathrin Liess and Johannes Schocks; HBS 91; Freiburg: Herder, 2018),76.

33 Cf. Isa 27:6; Edwin C. Hostetter, "ΠΊΏ," in New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis (ed. Willem A. VanGemeren; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1997), 3:683-685.

34 Cf. Ps 73:4-9.

35 Markus Saur, "Where Can Wisdom Be Found?: New Perspectives on the Wisdom Psalms," in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Worship (ed. Mark R. Sneed; AIL 23; Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015), 181-204.

36 Verse 8c may be an expanded colon or line, as described by Samuel E. Loewenstamm, "The Expanded Colon, Reconsidered," UF 7 (1975): 261-264. Lines 8a and b stand in parallel relation while 8c seems to interrupt the larger flow of thought that culminates in verse 9a. Without 8c, the two verses juxtapose the apparent success of the wicked with the cosmic rule of the Yahweh. See also, Tate, Psalms 51-100, 461462.

37 Travis J. Bott, "Figurative Enemies in the Psalms," 76.

38 The order of the texts presented in this section is from least complex to most complex; diachronic concerns are not assessed here.

39 On the relationship between the two texts, see Jerome F. D. Creach, "Like a Tree Planted by the Temple Stream: The Portrait of the Righteous in Psalm 1:3," CBQ 61 (1999): 34-46.

40 Cf. Ezek 47:12; Prov 11:28 (Bernd Janowski and Friedhelm Hartenstein, Psalmen [BKAT 15/1, Lieferung 1; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2012], 39).

41 On torah in Ps 1, see Phil Botha, "Intertextuality and the Interpretation of Psalm 1," OTE 18 (2005): 503-520.

42 This, along with its torah focus, is likely instructive in this regard (Creach, "Like a Tree Planted," 42). Botha contends that "it would seem that the Torah is presented in Psalm 1 as streams of water springing from the presence of Yahweh, perhaps forming a parallel to the temple, but not necessarily becoming a substitute for it" (Botha, "Intertextuality and the Interpretation of Psalm 1," 514). Creach suggests that a similar view of Psalm 1 was adopted in post-biblical literature (43-45).

43 Bernd Janowski, "Der Ort des Lebens: Zur Kultsymbolik des Jerusalemer Tempels," in Der Nahe und der Ferne Gott (ed. Bernd Janowski; BTAT 5; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2014), 207-243 (213).

44 "Instruction of Amenemope," in The Context of Scripture. Vol. 1: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World (ed. William W. Hallo and K Lawson Younger, Jr. ; Leiden: Brill, 1997), 115-122.

45 In Egyptian wisdom literature, the notion of order differentiates the heated one from the silent one. The sage, the truly silent one, "is the one who accepts the established order and the place this order assigns to him in this world" (Pascal Vernus, Sagesses de l'Egyptepharaonique [2 ed.; Arles: Actes Sudes, 2010], 305).

46 Nili Shupak argues that references to the "silent man" in literature associated with the New Kingdom frequently have a religious or cultic connotation (Where Can Wisdom Be Found? The Sage's Language in the Bible and in Ancient Egyptian Literature [OBO 130; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993], 166-167).

47 Whether the Egyptian source influenced the Hebrew texts or whether all of them were drawing upon a common ANE tradition is difficult to determine (Nili Shupak, "The Contribution of Egyptian Wisdom to the Study of Biblical Wisdom Literature," in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Worship [ed. Mark R. Sneed; AIL 23; Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015], 294).

48 In Ps 92, two trees are mapped on to the righteous. Beat Weber suggests that "the growth and prosperity of the righteous person implanted in the temple is compared to the date palm and the cedar of Lebanon." The focus of this comparison is on the tall growth of the palm, which is reinforced by the reference to the cedar, "considered to be the 'tree of God'" ("'Dann wird er sein wie ein Baum (Psalm 1,3): Zu den Sprachbildern von Psalm 1," OTE 23 [2010]: 418-419).

49 Cedars are mentioned in reference to the garden of God in Ezek 31:8.

50 The language of a wisdom trope (wicked vs. righteous) morphs into to the cultic and cosmic sphere. As Catherine Petrany notes, "Despite the sapiential timbre of verses 7-8 and 13-15, each section also includes characteristics that distinguish it from biblical wisdom and a purely reflective aim, particularly then taken within the context as a whole" (Pedagogy, Prayer and Praise: The Wisdom of the Psalms and Psalter [FAT 2/83; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015], 108).

51 Janowski, "Der Ort des Lebens," 217.

52 Similar imagery of the fructifying effect of the paradisiacal temple is present in Ezek 47:1-12; Joel 3:18 and Zech13:1.

53 Göran Eidevall, drawing from the work of Beate Pongratz-Leisten (Ina sulmi ïrub: Die kulttopographische und ideologische Programmatik der akltu-Prozession in Babylonien und Assyrien im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. [BaghF 16; Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1994]), notes that within the worldview of the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations, the wilderness is something wholly negative, while the city, "established by the gods is regarded as the centre of the world. Within its walls, peace prevails. Order, me, emanates from the city" ("Metaphorical Landscapes in the Psalms," 20). This same assessment of the wild versus the city appears to be at work in Jer 17. Those who trust in humans are "like a shrub in the desert" who lives in the "parched places of the wilderness," whereas those who trust in Yahweh are planted by streams and water (Jer 17:8). Later in the chapter, the association of the water with Yahweh and the temple is made explicit (Jer 17:12-13), with Yahweh being described as "the fountain of living water" (v. 13b). To a lesser degree, but no less true, Ps 92 also reflects this contrast between the wilderness and the city. That which is planted in the wilderness (i.e., grass, v. 8) is negative while that which is planted within the temple flourishes due to the nearness of God.

54 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 435. The LXX reads it as an epithet, ύψιστος ("highest one"). Tate reads Diiç as an epithet as well, "One-who-is-on-High" (Psalms 51-100, 460-461).

55 On the various construals of Yahweh's place of rule in the Hebrew Bible, see Konrad Schmid, "Himmelsgott, Weltgott und Schöpfer: 'Gott' und der 'Himmel' in der Literatur der Zeit des Zweiten Tempels," in Der Himmel [JBT 20; eds. Martin Ebner and Irmtraud Fischer; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2005), 111-148.

56 Tate, Psalms 51-100, 467.

57 Hans Joachim Kraus, Theology of the Psalms (trans. Keith Crim; CC; Minneapolis. MN: Fortress, 1992), 24-26.

58 Note the use of the full appellation in Gen 14:19: עֶלְיוֹן קֹנֵה שָׁמַיִּם וָאָרֶץ. Cf. Pss 83:18; 97:9.

59 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 441 n. 24.

60 On the connection between the metaphor of a "rock" and the presence of Yahweh, see Christiane de Vos, "Es gibt mehr Felsen in Israel," in Metaphors in the Psalms (ed. Pierre van Hecke and Antje Labahn; BETL 231; Leuven: Peeters, 2010), 1-11. Brown suggests that the "rock" metaphor has as its target domain "the protective God," highlighting "the unassailable security God offers the speaker" (Seeing the Psalms, 19). See also Othmar Keel, The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms (trans. Timothy J. Hallett; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 179-183.

Prof W. Dennis Tucker, Jr., Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor of Christian Scriptures, George W. Truett Theological Seminary, Baylor University, Waco, Texas. Email: Dennis_Tucker@baylor.edu. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1752-3620.