Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.31 n.3 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2018/v31n3a18

ARTICLES

What of the Night? Conceptions and Theology of Night in Isaiah and the Book of the Twelve

Funlola Olojede

Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

Even though a number of studies have probed the concept of time in the Hebrew Bible, very little has been said about night as a unit of time. This article investigates the conceptions and theology of night in Isaiah and in the Book of the Twelve (Minor Prophets). Whereas strong existential correspondence between day and night is found in Isaiah featuring both negative and positive associations with nocturnal activities, the concept of night is absent in parts of the Book of the Twelve. It is argued that the conceptions of night as depicted through the night-time activities and actors (which include God, prophets, watchers, the people of Israel, etcetera.) have implications for the theology and the worldviews expressed in these prophetic books.

Keywords: Night, Isaiah, Book of the Twelve, Day of YHWH

"...Watchman, what of the night? ...The morning cometh, and also the night: If ye will inquire, inquire ye" (Isa 21:11-12, KJV).1

A INTRODUCTION

In this article, the question posed to the watchman in Isaiah 21:11, "Watchman, what of the night?" is considered an interesting one which can be appropriated to mean, should we not reflect on the importance of night to the prophets and to prophecy? Since the watchman's answer is, "If you would like to enquire about night, go ahead," this essay probes the theology of the concept of night (Heb. לַיְלָה), specifically, in the books of Isaiah and of the Twelve. The book of Isaiah is regarded as a theological reflection on the experiences of the people of Judah and Jerusalem in the aftermath of the Assyrian invasion and the Babylonian exile and how the people tried to make sense of the question of theodicy.2 The focus of this article does not necessitate a foray into the debates about the unity of Isaiah but the discussion considers the book in its final form - as a unity and essentially in relation to the Book of the Twelve.

The Book of the Twelve, also known as the Minor Prophets,3 is regarded as a collection of individual works and a single prophetic volume which consists of Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi.4 Historically, the textual unity of the Twelve has been acknowledged based on literary and thematic affinities identified within the Book although some scholars tend to disagree on the nature of the unity.5Sweeney notes that the Book of the Twelve shares "an intertextual relationship with the book of Isaiah that points to a very different understanding of the significance of world events for understanding divine purpose". Whereas "Isaiah identifies the manifestation of YHWH's sovereignty with the rise of the Persian Empire", the Book of the Twelve "calls upon its audience to fight against the nations that oppress Israel/Judah/Jerusalem under the rule of YHWH and the Davidic monarch in order to realise the promised restoration of Jerusalem".6What is more central to the argument in this essay is Sweeney's observation that:

To a certain degree, the book of the Twelve engages in debate with the book of Isaiah, which offers a similar reflection. But whereas Isaiah envisions a scenario in which Israel will join the nations at Jerusalem in submitting to YHWH and will accept Persian rule as an expression of the divine will, the book of the Twelve collectively argues that YHWH will raise a Davidic messiah who will play a role in enabling YHWH to defeat the nations that oppress Jerusalem, thereby prompting them to recognize YHWH's sovereignty.7

Findings from my two previous studies on night show that day and night as well as light and darkness often form a word pair in the Old Testament, and that whereas night is naturally identified with darkness, day is associated with light. As a word pair, "day and night" (e.g. Eccl 8:16; Isa 60:1; 62:6) as well as its negative variant, day nor night (e.g. Lev 8:35; Josh 1:8; 2 Chr 6:20; Neh 1:6; Jer 9:1; Lam 2:18) is used figuratively in the Old Testament to express a continuous or perpetual process-that which takes place around the clock or nonstop.8 With respect to the book of Job and the Psalter, I have demonstrated that though some activities take place both in the day and the night9 and that both positive and negative images are associated with the night in Job and in the Psalter where we also find similar night-time activities; in both books; night-time activities are carried out by human and spirit beings as well as non-human beings (Pss 22:2; Job 4:15-21; 24:14; 34:14-15, 25; 35:10). But animals, birds and other elements of nature such as the dew, whirlwind, firmament, moon and stars also constitute non-human actors.10

A subsequent study of night in Proverbs-Qoheleth-Song of Songs shows that as in Job-Psalter, the images of the night in Proverbs are both positive and negative whereas in Qoheleth, the tension between night and day or between darkness and light is unresolved. Rest and restlessness are experienced in the night but Qoheleth deflects from staring night in the face by focusing on the sun. In the Song, love, romance, dreams and desire mingle with violence, disappointment and despair. Yet the Song ends on a positive hopeful note.11 The findings on night in Proverbs-Qoheleth-SoS seem to complement what has been overlooked by the Job-Psalter. Whereas the conception of night in the Job-Psalter centres primarily on God who can be viewed as the main nocturnal actor, such a theocentric focus is missing in the Proverbs-Qoheleth-SoS text. On the other hand, neither Job nor the Psalmist is concerned about love or romance in the night like the lovers in the SoS, but then the violence in the street in the SoS echoes the kind of violence from which the Psalmist cries out to God for deliverance and which is noted also by Job (e.g. Ps. 55:9-10; Job 24:14).

In what follows, I shall argue that any theological consideration of the temporal implications of the references to night (or even to darkness) in the book of Isaiah and the Book of the Twelve must necessarily take into account the social-historical context and the trauma that characterised the period described in the two texts. Elsewhere in my previous studies on night, it has been noted that night as a unit of time is used in the Old Testament either literally or "metaphorically to refer to a time of crisis, of distress, of helplessness or of God's judgement (cf. Isa 15:1; 21:11-12; Mic 3:6)".12 In the case of Isaiah and the Twelve, the preponderance of evidence seems to suggest that night is used mostly as a metaphor alongside darkness to refer to a time of crisis. It is important to point out that Isaiah expresses "The concept of the Day of YHWH [which] is rooted in the liturgy of the Jerusalem Temple where it expresses YHWH's efforts to defeat enemies and to manifest divine glory".13 This concept of the Day of YHWH in which YHWH would punish not only Israel and Judah but the other nations as well resonates throughout the book of the Twelve Prophets and it has a significant association with night in the texts.

Four main intersecting theological themes have been identified in the Book of the Twelve viz. the Day of YHWH, fertility of the land, the fate of God's people and the theodicy problem.14 And even though it is conceived in different ways, the Day of YHWH is recognised as a recurring theme throughout the Book which offers the Book literary cohesion.15

B ISAIAH AND THE NIGHT OF JUDGEMENT

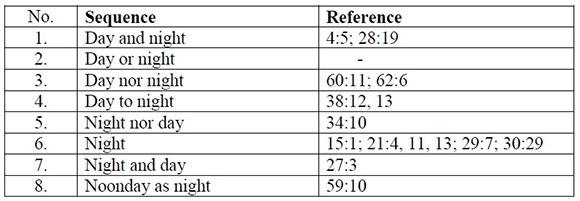

The book of Isaiah contains approximately 19 references to the Hebrew word לַיְלָה (night) and in most of the cases, night is used as a word pair with day in different combinations (Isa 4:5; 5:11; 16:3; 21:8, 12; 28:19; 27:3; 34:10; 62:6), as shown in the illustration below.

Further, night-time activities in Isaiah appear to include both the positive and the negative. Like the psalmist (cf. Ps 63:5, 6; 77:2; 119:62), the prophet also expresses a strong desire for God in the night which is unabated even in the early hours of dawn (Isa 26:9). And he declares that the people will have a song in the night at their solemn assembly when they go up to the mountain of the Lord (Isa 30:29; cf. Job 35:10). In addition, the idea of watching even though could be associated with the day is more significantly used in respect of the night (Isa 21:8, 11-12; 62:6; cf. Pss 90:4; 119:148.16

Then the guard cries out:

"On the watchtower, O sovereign master, I stand all day long; at my post

I am stationed every night (Isa 21:8).

Related to watching also is the idea of dreams and visions in the night. The prophet announced that judgment was coming from the Lord that would be unto the people like a dream or vision of the night (Isa 29:6-8).17 But then, in Isaiah 28:18-19, the prophet announces that judgment from the Lord will sweep through the midst of Jerusalem not only in the day but also at night. Isaiah 28:20 continues with the motif of judgment at night with references to the bed being too short to stretch out on, and the blanket being too narrow to wrap around oneself. The people themselves admit that their confusion is so great that they stumble at daytime as if it were night-time.18 However, the act of judgment at night is also reserved for the nations. The oracle against Moab shows that its destruction would happen at night. Ar and Kir, cities of Moab, would be devastated at night (Isa 15:1).19 The fiery destruction of Edom would be a continuous one that takes place day and night (Isa 34:8-10). The destruction at night is also confirmed by the presence of owls and other nocturnal animals (Isa 34:12-15). Like that of Ariel (Isa 29:7), the destruction that is determined against Arabia would probably also take place at night (Isa 21:13).

It could be argued that the point that judgment occurs at night is central to the conception of night in the book of Isaiah. This point is buttressed by the story in Isaiah 37:36 (//Kgs 19:35) in which an angel of the Lord went into the camp of the King of Assyria and, in one night, struck 185 000 people. The act took place in the night because we read that when people arose early in the morning, there were dead corpses everywhere. Judgment against a whole people at night in Isaiah, however, departs from judgment on individual enemies in the Psalter.

As in the Job-Psalter texts, fear is also associated with the night in Isaiah (28:19; cf. Job 7:4; 30:17; Ps 91:5). The prophet recalls that the night that he had desired or longed for has now turned into a time of terror for him (Isa 21:4), and he is also wary of what the Lord would do to him, of the punishment the Lord would inflict on him (Isa 38:13). A major night-time actor is YHWH himself who sends judgment and destruction but who is also a source of protection and defence for his people in the night (Isa 4:5; 27:3; 62:6).20 The prophet like or as the watchman (Isa 21:11-12; 62:6) is also active at night (cf. Isa 21:4). He desires God in the night and continues on the watchtower (Isa 26:9; 21:8). Moreover, those who imbibe strong drink do so during the day and continue until they are fully inebriated at night-time.

Besides the overt references to night in the book of Isaiah, some other concepts that are associated with night-time occur such as bed (Isa 28:20; 57:2, 7, 8); stars (Isa 13:10; 14:13; 47:13); (new) moon (Isa 1:13-14; 3:18; 13:10; 24;23; 30:26; 60:19, 20; 66:23); sleep/rest (Isa 5:27; 29:10; 56:10; 57:2; cf. 14:30 - lie down). The mention of these words conjures images of night or of nighttime activities. What is remarkable here is that the word night is not used at all in the unit that is referred to as Deutero-Isaiah although darkness and its cognates occur there a number of times (Isa 42:7; 45:3, 7, 19; 47:5; 49:9; 50:10). I have established previously that there is a natural correspondence between night and darkness and that the two concepts are polarised against day and light, respectively. It is therefore unsurprising that darkness or cognates such as dark or darkening occur numerous times in Isaiah (5:20, 30; 8:22; 9:2, 19; 13:10; 24:11; 29:15, 18; 42:7, 16; 45:3, 7, 19; 47:5, 9; 49:9; 50:10; 58:10; 59:9; 60:2).

In Isaiah, darkness, like night, is used mostly to portend disaster and judgment that stems from the wrath of YHWH (cf. Isa 5:30; 8:22; 9:19; 59:9; 60:2). Metaphors of blindness and darkness are used to describe the condition of the Golah community at the time of the oracles in Isaiah21 (cf. Isa 9:1-2; 29:18; 42:7, 16; 59:9). The elements also attest to the darkness that have come upon the nation as both the moon and the stars become darkened in the day of YHWH (Isa 5:30; 13:10; cf. Joel 2:10). Whereas the darkness that covers God's nation and people would eventually give way to light (Isa 9:2; 29:18; 42:7, 16; 50:10; 58:10) with the movement from judgment to salvation, utter darkness would cover the nations and the rest of the earth (Isa 8:22; 47:5; 60:2). The end of the darkness alludes to the end of the exile and Israel's suffering in captivity. Interestingly, the Lord takes responsibility for creating both light and darkness (Isa 45:7) and shows that he can turn darkness into light (Isa 42:16; cf. Gen 1:3-5).

Again, as in the Job-Psalter setting, the distinction between light and darkness is blurred in Isaiah (13:10; 16:3; 30:26; 59:10; cf. Job 5:14; 17:12; Ps 139:11). Day also flows into night and night into day in what appears to be a continuity of time or timelessness. Jerusalem's gates will be open day and night (Isa 60:11) and the watchmen on its walls will keep silent neither day nor night. Imageries of the morning also contrast with those of night in Isaiah (Isa 5:11; 14:12; 17:11, 14; 21:12; 28:19; 32:2; 37:36; 38:13; 50:4; 58:8), suggesting that night does not necessarily have the final say in the order of events.

C NIGHT IN THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE

In discussing the concept or theology of night in the Book of the Twelve, it is important to remark here that only the first six books and Zechariah contain clear references to night. The word night does not occur at all in the books of Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai and Malachi. However, in Nahum and in Zephaniah, the term dark/ness appears once (Nah 1:8; Zeph 1:15).

1. Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai and Malachi and the Absence of Night?

Although the imagery of the Day of YHWH is expressed in these five books, (Am 5:18-20; Joel 2:1-14; Zeph 1:2-18; Hag 2:23; Mal 3:2, 17; 4:1, 3, 5), the book of Nahum differs from the majority of the other prophets because most of the prophet's oracle in its present form is directed against Israel's enemies rather than against Israel, Judah or Jerusalem.22 Several similarities are found between Nahum and Isaiah 40-55, for example Nah 1:15//Isa 52:7,23 but Nahum is also linked in particular to Jonah as both books focus on the doom of Nineveh/Assyria (cf. also Nahum 1:3 and Jonah 4:2 where YHWH is described as slow to anger).24Regarding the fate of the people of Nineveh, Nahum declares that these enemies of YHWH will be pursued by/into darkness (Nah 1:8). In that verse, darkness, like flood, is personified as an agent of YHWH that is sent to make an end to the people of Nineveh.

Zephaniah on the other hand announces the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonian army as well as the restoration of the city. The day of YHWH is designated as a day of judgement and punishment. Like Nahum, Zephaniah also uses the motif of darkness to portend the day of YHWH which he says would be "a day of wrath, a day of trouble and distress, a day of waste and desolation, a day of darkness and gloominess, a day of clouds and thick darkness" (Zeph 1:15 ASV). But unlike in Isaiah where judgement prevails at night, Zephaniah declares that YHWH actually brings his judgement to light every morning (Zeph 3:5).

Whereas the books of Habakkuk, Haggai and Malachi contain no mention of night or darkness, the central question raised in Habakkuk is why YHWH would bring an oppressor, that is, Babylonia, against Judah.25 Habakkuk then makes some allusions to night in 2:1-3. As in Isaiah 21:8 where the prophet stands day and night at the watch post, Habakkuk also says he would stand at his watch post and keep watching until he gets an answer from YHWH. The reference to vision in Habakkuk 2:3 indicates that his time of continual watch includes the night. Additionally, both the sun and moon stand still at the appearance of YHWH suggesting that the theophany transcended day and night (Hab 3:11; cf. Josh 10:12-13). The book of Haggai which takes a narrative form calls for the reconstruction of the Temple of which Zerubbabel is seen "as YHWH's designated regent".26 The prophet also seeks the restoration of the Yehud community which had been under Persian rule.27 It is unsurprising therefore that the short book contains no reference to night or darkness since the prophet only aims at stirring the people to a positive action that would herald a brighter future. Malachi's oracle which stresses YHWH's abhorrence of divorce, calls upon the people to return to YHWH and "to hold firm to the covenant as YHWH's messenger approaches".28 But in the book, there is no night.

2. Hosea and the Night of Stumbling

The prophet Hosea uses his own marriage to Gomer as a metaphor to depict Israel as YHWH's wayward wife who "engaged in harlotry by pursuing other lovers, prompting Hosea/YHWH to punish the wayward bride with divorce..."29 The nation is experiencing judgement because it had forsaken YHWH. Therefore, Hosea's prophetic oracles appeal to the people of Israel to move away from judgment, repent and return to YHWH who is angry with them because of their association with Egypt and Assyria.30

In Hosea 4, where the first of the two occurrences of night in the book is found, the prophet shows that YHWH has an axe to grind with his people who have forgotten his laws and now suffer punishment for their sins. The common people are not the only ones in error, their priests and prophets have also failed YHWH. YHWH therefore declares that the people "will stumble by day, and the prophets also will stumble" along with them by night (Hos 4:4-5). This verse calls to mind Micah 3:6-7 which states that the sun would set on the prophets and night would come upon them without visions. In other words, the idea of the prophets stumbling by night implies that they would no longer receive any word or vision from YHWH. Rather, what they would experience is confusion. Stumbling in the dark is clearly the fallout of the people's lack of knowledge (Hos 4:6). They have rejected knowledge and are destroyed because of their ignorance.

Hosea 7 further describes Ephraim's unfaithfulness to YHWH and notes that in their error the people have become a bitter and angry nation. This anger smoulders in the night and reaches its climax in the morning: ".. .Their hearts are like an oven; their anger smoulders all night long, but in the morning it bursts into a flaming fire" (Hos 7:6). Night seems to offer no positive thing to Hosea's audience, neither does the morning; for at the break of day, the king of Israel would be cut off completely (Hos 10:15) and his people would be like the morning cloud and like the dew which soon disappear (Hos 13:3). Nonetheless, the prophet enjoins the people to seek the Lord who would come to their rescue as certainly as the appearance of the dawn31 and come to them as the winter rain and the spring rain that water the earth (Hos 6:3-4).

3. Joel and the Night of Mourning

A central motif which runs through the book of Joel is the day of YHWH (1:15; 2:1, 11, 31; 3:14). The book begins with a description of the devastation that has come upon Israel - the drought and its attendant misery- and the proclamation of a national fast. The prophet then declares the imminent appearance of the day of the Lord and the judgement on the land and on the nations that oppressed Israel. But the judgement and sorrow will give way to a new era of prosperity and restoration (Joel 3:18). Although the word night occurs only once in Joel, the prophet employs extensive and vivid imageries of darkness and gloom to depict Israel's situation at a time of apostasy and judgement. In Joel 1:13, the prophet calls to the people:

Gird yourselves with sackcloth, and lament, O priests; wail, O ministers of the altar! Come, spend the night in sackcloth, O ministers of my God, for the grain offering and the drink offering are withheld from the house of your God (NASB, cf. 2:17).

The priests and the ministers are called upon to spend the night in mourning and lamentation. But they are also to invite the elders and all the people of the land to join in a fast and cry unto the Lord together (Joel 1:14-15; 2:16). The night of doom and gloom has no room for the groom or for his virgin bride because of the looming judgement of the day of YHWH (Joel 1:8-9, 15; 2:16). Although day is characterised by light, it is preceded by night and darkness. And so is the day of YHWH; it is not only foreshadowed by the deepest darkness, it is "A day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness" even though it is morning time (Joel 2:2; cf. Amos 5:18; Zeph 1:15). On that day, daytime loses its power because "The sun and the moon grow dark and the stars lose their brightness" (Joel 2:10, 31; 3:15). It is a day of tears, of wailing and of desperate sorrow.

But in the end, judgement will not prevail, for YHWH will pour out his spirit and whoever calls upon his name will be saved (Joel 2:28, 32). YHWH will restore the fortunes of his people and the mountains will once again drip with new wine (Joel 3:1, 18; Am 9:13).

4. Amos and the God of the Night

Amos is recognised as the first prophet to condemn not only the people of Judah and Israel in his oracles but also the neighbouring nations.32 The oracles address mostly the northern kingdom of Israel, pronouncing judgement on it and on the neighbouring nations that have exploited Israel. However, the prophet also calls on the people to return to YHWH.33 Sweeney notes that, "Overall, Amos envisions the Day of YHWH, perhaps, a day that signals YHWH's defence of the nation (see Joel) as a day of YHWH's judgment against Israel (Amos 5:18-20)".34 It is in the context of that day of YHWH that the only reference to night in Amos occurs (5:8). The people are enjoined to seek YHWH in order to live (5:5-6) because the Day approaches.

However, several imageries of darkness occur in the book. Amos 4:13 presents YHWH to the people as the one who makes dawn into darkness or darkens day into night (4:13; 5:8). Interestingly, YHWH is also the One who changes deep darkness into morning (5:8), corroborating findings from JobPsalter that the distinction between night and day is sometimes fuzzy, as day dissolves into night and night into day at the behest of YHWH (Pss 74:6; 139:1112; Job 5:14; 17:12; 18:6; cf.10:22; Isa 45:7).35 Amos therefore confirms that YHWH is solidly in control of both the day and the night (Am 5:8). In Amos 5:18, the prophet goes on to link the day of YHWH with darkness-that day would be darkness and not light (see also Am 5:20). YHWH would accomplish that by causing the sun to go down at noon and cause the earth to darken in daylight (Am 5:9). The gloom and mourning that characterise that day in Joel 2:2 are also witnessed here (Am 5:10; cf. Zeph 1:15). And even though YHWH's judgement is inevitable, restoration is also assured. As in the reports of Prophet Joel, the mountains will once again drip with new wine (Joel 3:18).

5. Obadiah and the Thieves by Night

As short as the book of Obadiah is,36 it contains one mention of night (Obad v.5). The oracle recorded in the book is primarily against Edom37 and its close parallel with the prophecy of Jeremiah cannot be overlooked (Obad 1-7, 16//Jer 49:7-22).38 Obadiah vv.11, 15, 16 and 18 are also comparable to Joel 3:3; 1:15; 3:17 and 2:5 respectively. 39 Renkema argues that "Obadiah borrows the image of thieves from Jeremiah".40 In v.5 of the book, Obadiah uses the metaphor of thieves robbing at night to underscore the destruction that would come upon Edom. He claims that night thieves (or robbers) would only take as much as they wanted but the destruction of Edom would be total. In the previous verse, an allusion to night is also found. Edom may attempt to soar high like an eagle and make its nest among the stars, but it would be brought down. The motif of the day of YHWH which is visible all through the Book of the Twelve also surfaces in Obadiah (v. 15). But that day is a day of judgement for the nations. The nations especially Edom will experience misfortune but the people of God will experience deliverance and their king will be enthroned in Zion (vv.17, 21).

6. Jonah and the Nights in the Deep

Like Haggai, the book of Jonah also takes a narrative form but highlights the question of theodicy and of YHWH's righteousness. In Jonah, the prophet tries to run away from a divine assignment to Nineveh and from YHWH. Therefore, he joins a ship that is sailing to Tarshish. But the hand of YHWH is against him and he is thrown into the deep where he ends up in the belly of a huge fish. It is in the belly of the fish that night falls for Jonah and it would be three days and three nights later before he is freed from the clutches of death (Jonah 1:17). Even though it is daytime on land, in the belly of the fish, the three days and three nights are one unbroken night; for the prophet does not see the light of day.

Jonah's prayer in chapter 2 which shares resemblances with some Psalms41 and shows that the several nights in the deep prove to be a time of distress and desperation. He is totally cut off from the YHWH that he is escaping from and his soul experiences deep anguish. In the netherworld of darkness and overwhelming flood, his heart-cry to God could only be for mercy. After he is disgorged by the fish, Jonah heads to Nineveh and preaches so hard that even the animals join the people of Nineveh to fast and mourn in repentance (Jonah 3:8). But the day breaks again for Jonah and his eyes see the sun and the beauty of a little plant that sprang up in the night (4:7-8). Then he becomes angry, angry at YHWH for sparing Nineveh and for destroying the plant that shaded him from the heat of the sun, angry enough to want to die. In spite of his anger, YHWH's hesed prevails over judgement.

7. Micah and Night without Visions

The book of Micah which could be mistaken for a mini-Isaiah because of their common themes and oracles (Mic. 4:1-4//Isa. 2:2-442) actually differs from Isaiah in some other respects. Micah is assumed to be a contemporary of Isaiah43 and the book begins with a divine call for the destruction of Samaria and Judah in Micah 1-3,44 using "YHWH's punishment of Samaria as a paradigm for that of Jerusalem".45 Micah 4-5 on the other hand contains oracles of salvation whilst Micah 6-7 presents additional oracles of judgment and hope.46

Mason notes that the book of Micah "shares with the book of Isaiah the promise of God's universal rule in a restored and elevated Jerusalem so that the nations will come there and submit themselves to his adjudication and rule" (cf. Mic 4:3).47 He adds that, "Both apparently delivered similar messages, especially in denouncing the greed and ruthlessness of the powerful and wealthy, in predicting judgment from God, and in calling for ethical righteousness in society".48 And like Isaiah, the message of Micah also shows a movement from destruction to restoration, from judgment to hope. However, Sweeney points out that "Unlike his better-known colleague Isaiah, Micah calls for the destruction of Jerusalem (Mic 3:12)".49 In addition, "Whereas Isaiah calls for submission to the rule of the nations, most notably Persia, as the will of YHWH, Micah calls for the overthrow of the oppressive nations and restoration of a righteous Davidic monarch".50

Although Micah 2:1 contains an allusion to night51, the only night-time activity that is mentioned in the book relates to dreams and visions (Mic 3:6-7). Micah 3 in which the reference to night is found contains an oracle of judgment against the prophets of Israel (Mic 3:5-8). According to Smith-Christopher, "Micah describes the fate of corrupt prophets as silent darkness" and that, "The result of this dark silence from God will be the shame of the prophets".52 As in Isaiah, the metaphors of night and darkness are used by Micah to show that the prophets have been cut off from YHWH and that their activities are condemnable. Although Isaiah implies that dreams and visions occur at night (Isa 29:6-8) and that prophets and priests could err in vision through strong drink (Isa 28:7), Micah specifically shows that such dreams and visions are associated with prophets. Indeed, Old Testament prophets, particularly the seers, operated in the realm of dreams and visions (e.g. Num 12:6; 24:4, 16; 2 Sam 7:17; Ezek 1:1; Hos 12:10; Zech 13:4). However, "It is striking how often 'visions' are spoken of in negative contexts and are paired with divination. Thus, Jeremiah features two bitter denunciations of prophetic corruption that strongly echo Micah: Jer 14:14... and 23:16.. ,"53 It is ironic also that dreams and visions which are revelatory and associated with a burst of light from the divine actually occur at night, at a time of darkness. Therefore, to the prophets of Israel who are at the centre of night-time activities in the book, the Prophet Micah says, night would be, literally and figuratively, a time of darkness.

As in Isaiah where darkness would eventually give way to light, Micah also expresses strong confidence that his darkness, the darkness of Jerusalem and of the people of God will turn to light; therefore, the enemy should not gloat (Mic 7:8). As a matter of fact, the Lord will be the light of his people (Exod 13:21; Ps 27:1; Isa 2:5). The movement again is from disaster to hope and this verse recalls also Isaiah 9:2 in which the people who sat in darkness see a great light.

8. Zechariah and Visions of the Night

The book of Zechariah is also written in a narrative form and according to Sweeney, it "cites extensively from Isaiah and other prophetic books (e.g., Zech 8:20-23; cf. Isa 2:2-4)" which "would cast Zechariah as an authentic witness to the Isaian tradition".54 Zechariah is often linked with Haggai based on Ezra 5:1 and 6:14 which mention both prophets.55 But Zechariah is more of a seer who like Ezekiel shares several visionary experiences which have some apocalyptic content.56 Eight visions are reported in Zechariah which mention the word night twice (Zech 1:8; 14:7) and darkness once (Zech 14:16). The first reports the prophet's vision of a man riding on a red horse among other coloured horses (Zech 1:8). This is followed by the prophet's conversation with an angel of YHWH who explains that the horses have been assigned to patrol the earth and by YHWH's response to the angel (Zech 1:9-17).

The second reference to night is in the context of the day of YHWH in which there will be no light because the sources of light in heaven will congeal (14:6) and curiously, this would happen not in the day or in the night but in the evening and there will be light (Zech 14:7). No doubt, the day of YHWH is one of the central motifs in Zechariah which mentions, numerous times, the phrase, "in that day" or the day of YHWH (Zech 2:11; 3:10; 9:16; 12:3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 13:1, 2, 4; 14:1, 4, 6, 8, 9, 13, 20, 21). It is assumed here that the subsequent visions in the book also took place at night. Zechariah claims that he was awakened out of sleep by the angel who talked with him (Zech 4:1). The experience of Zechariah who sees visions at night therefore contrasts with Hosea 4:4-5 and Micah 3:6-7 which report that visions of the night are withheld from Israel's prophets.

D CONCLUSION

I have shown that night is used metaphorically in Isaiah and the Book of the Twelve to underscore the theological underpinnings in these texts especially in respect of the day of YHWH which is a motif that Isaiah shares with the Book of the Twelve. It is ironic that the day of YHWH is actually characterised by night and darkness, confirming again the blurry line between night and day. It can be argued that the use of night as a metaphor in the texts to depict Israel's experiences of desolation and judgement was informed by the traumas of the exilic and post-exilic periods. Although three of the books in the Twelve (Habakkuk, Haggai and Malachi) contain no overt reference to night or darkness and two books (Nahum and Zephaniah) only mention darkness and no night, the references to night in the other books at one level or another find resonance with night in Isaiah or in other books in the Twelve.

At the same time, the occurrence of night in each of the books seems to emphasise some unique characteristics. In Isaiah, judgement and night go hand in glove whereas the people of Israel stumble at night in Hosea and mourn at night in Joel. To Amos, God's control of the night is without question and Obadiah employs the metaphor of thieves that operate at night to capture the destruction that would come on Israel's enemies but in Jonah and Zechariah, there is a personal undertone to night-time activities. As active characters in the night, Jonah experiences nights of horror and darkness in the deep whilst Zechariah experiences visions from YHWH at night. On the contrary, Micah shows that night can come without visions even to the seer. The seeing eyes grow dim, yet light comes to those who sit in darkness and they behold YHWH's righteousness.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coggins, Richard J. "In Wrath Remember Mercy: A Commentary on the Book of Nahum". Pages 5-63 in Israel among the Nations: A Commentary on the Books of Nahum and Obadiah and Esther. Edited by Richard J. Coggins and Paul S. Re'emi. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1985. [ Links ]

Coggins, Richard J. "Judgment between Brothers: A Commentary on the Book of Obadiah". Pages 67-100 in Israel among the Nations: A Commentary on the Books of Nahum and Obadiah and Esther. Edited by Richard J. Coggins and Paul S. Re'emi. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1985. [ Links ]

Coggins, R.J. Haggai, Malachi, Zechariah. Old Testament Guides. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Hasel, Gerhard F. Understanding the Book of Amos: Basic Issues in Current Interpretations. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1991. [ Links ]

Jones, Barry Alan. The Formation of the Book of the Twelve: A Study in Text and Canon. SBL Dissertation Series 149. Atlanta, GA: SBL, 1995. [ Links ]

Kessler, John. The Book of Haggai: Prophecy and Society in Early Persian Yehud. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 91. Atlanta: SBL, 2002. [ Links ]

Mason, R. Micah, Nahum, Obadiah. Old Testament Guides. Sheffield: JSOTSS Press/Sheffield Academic Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Mays, James Luther. Amos: A Commentary. OTL. Fourth Edition London: SCM, [1969]1978. [ Links ]

Mays, James Luther. Micah: A Commentary. OTL. London: SCM, 1976. [ Links ]

McEntire, Mark. A Chorus of Prophetic Voices: Introducing the Prophetic Literature of Ancient Israel. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Nogalski, James D. "The Day(s) of YHWH in the Book of the Twelve". Pages 192-213 [ Links ]

in Thematic Threads in the Book of the Twelve. Edited by Paul L. Redditt and Aaron Schart. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003. [ Links ]

Nogalski, James D. "Recurring Themes in the Book of the Twelve: Creating Points of Contact for a Theological Reading". Interpretation 61/2 (2007), 125-136. https://doi.org/10.1177/002096430706100202 [ Links ]

Nogalski, James D. The Book of the Twelve: Hosea-Jonah. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 2011. [ Links ]

Olojede, Funlola O. "What of the Night? Theology of Night in the Book of Job and the Psalter." Old Testament Essays 28/3 (2015): 724-737. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n3a10 [ Links ]

Olojede, Funlola O. "What of the Night? Conceptions of Night in Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs." Scriptura 116 no. 2 (2017): 148-159. Special Edition. Storyteller and Sage: Celebrating the Legacy of Hendrik Bosman. [ Links ]

Redditt, Paul L. "The Formation of the Book of the Twelve: A Review of Research". Pages 1-26 in Thematic Threads in the Book of the Twelve. Edited by Paul L. Redditt and Aaron Schart. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003. [ Links ]

Redditt, Paul L. "Themes in Haggai-Zechariah-Malachi." Interpretation 61 no. 2 (2007): 185-197. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, Rolf. "How to Read the Book of the Twelve as a Theological Unity". Pages 75-87 in Reading and Hearing the Book of the Twelve. Edited by James D. Nogalski and Marvin A. Sweeney. Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2000. [ Links ]

Renkema, Johan. Obadiah. Historical Commentary on the Old Testament. Leuven: Peeters, 2003. [ Links ]

Smith-Christopher, Daniel L. Micah: A Commentary. OTL. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2015. [ Links ]

Sweeney, Marvin A. The Prophetic Literature. IBT. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2005. [ Links ]

Wessels, Wilheim "YHWH, the God of New Beginnings: Micah's Testimony." HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 69 no. 1 (2013), Art. #1960, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Isaiah 40-66. Translated by David M.G. Stalker from the German. OTL. London: SCM Press, 1969. [ Links ]

Zvi, Ben and Nogalski, James. Two Sides of a Coin: Juxtaposing Views on Interpreting the Book of the Twelve, the Twelve Prophetic Books. Introduction by Thomas Römer. Piscataway, N.J: Gorgias Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Submitted: 04/10/2018

Peer-reviewed: 10/19/2018

Accepted: 19/11//2018

Dr Funlola O. Olojede, researcher at the Gender Unit, Beyers Naudé Centre for Public Theology, Stellenbosch University. Email: funlola@sun.ac.za.

1 Except otherwise stated, the New English Translation (NET) of the Bible is used throughout this essay.

2 Marvin A. Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature (IBT; Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2005), 52.

3 See Gerhard F. Hasel, Understanding the Book of Amos: Basic Issues in Current Interpretations. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1991), 17fn1.

4 A different sequence of the books from the Masoretic textual tradition is found in the LXX and 4QXIIa. See Richard J. Coggins, "In Wrath Remember Mercy: A Commentary on the Book of Nahum", in Israel among the Nations: A Commentary on the Books of Nahum and Obadiah and Esther (ed. Richard J. Coggins and Paul S. Re'emi; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1985), 5-63 (12). Barry Alan Jones, The Formation of the Book of the Twelve: A Study in Text and Canon (SBL Dissertation Series 149; Atlanta, GA: SBL, 1995), 3. Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 165. Nogalski sees the Book of the Twelve as "a compendium of prophetic speeches and speeches ... circulated as independent collections before being incorporated into a developing multivolume corpus". James D. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve: Hosea- Jonah (Smyth and Helwys Bible Commentary; Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 2011), 11.

5 Jones, The Formation of the Book of the Twelve, 6-7, 22. Jones notes that, "Scholars who judge the Book of the Twelve to be a literary unity are generally more sceptical about either the existence of comprehensive redactional layers within the text, or the possibility of reliably identifying such layers. Instead, these scholars view the Book of the Twelve as a compilation of pre-existing materials that were recognized as already possessing literary, thematic, or structural affinities". Jones, The Formation of the Book of the Twelve, 23.

6 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 172.

7 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 208.

8 Funlola O. Olojede, "What of the Night? Theology of Night in the Book of Job and the Psalter," OTE 28/3 (2015): 724-737 (727).

9 Olojede, "What of the Night", 734.

10 Olojede, "What of the Night", 735.

11 Olojede, Funlola O. "What of the Night? Conceptions of Night in Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs," Scriptura 116/2 (2017): 148-159 (154-155).

12 Olojede, "What of the Night", 728.

13 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 55-56.

14 Although Zvi questions the validity of the hypothesis of the Book of the Twelve, he notes that some of the main themes in the Book are the Day of YHWH, the fate of Israel, the role of Jerusalem and the nations. Significantly, however, he argues that "none of these issues are unique to the supposed Book of the Twelve" because they also appear outside the prophetic books. Ben Zvi, "Is the Twelve Hypothesis Likely from an Ancient Readers' Perspective?" in Two Sides of a Coin: Juxtaposing Views on Interpreting the Book of the Twelve, the Twelve Prophetic Books (Introduction by Thomas Römer; Piscataway, N.J: Gorgias Press, 2009), 47-96 (95). Rendtorff on the other hand reads the Twelve as a theological unity based on the chronology and the themes, with the dominant or unifying theme being the Day of the Lord. Rolf Rendtorff, "How to Read the Book of the Twelve as a Theological Unity" in Reading and Hearing the Book of the Twelve (ed. James D. Nogalski and Marvin A. Sweeney; Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2000), 75-87. See comments by Paul L. Redditt, "The Formation of the Book of the Twelve: A Review of Research" in Thematic Threads in the Book of the Twelve (ed. Paul L. Redditt and Aaron Schart; Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003)1-26 (3). Redditt also argues that the Twelve could be read "canonically as a coherent unit, in addition to reading them individually". Redditt, "The Formation", 25.

15 James D. Nogalski, "Recurring Themes in the Book of the Twelve: Creating Points of Contact for a Theological Reading", Int 61/2 (2007), 125-136 (125). Cf. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve, 11. Nogalski who evaluates the theme of the Day of YHWH based on three criteria-the target, the time frame and the means-notes that, "The Day of YHWH describes a dramatic point of YHWH's intervention in the affairs of this world. The target of this intervention may be YHWH's people or foreign nations. The timeframe of the day can refer to some point in the immediate future that is soon to be actualized; or, it can refer to a point in the more distant future... The means of judgment on this day is an attacking army led by YHWH himself..." Nogalski, "Recurring Themes", 126. Cf. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve, 11. James D. Nogalski, "The Day(s) of YHWH in the Book of the Twelve" in Thematic Threads in the Book of the Twelve (ed. Paul L. Redditt and Aaron Schart; Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003), 192213 (195-196).

16 Note that a different kind of watching is also done in the tombs - "They sit among the tombs and keep watch all night long" (Isa 65:4).

17 "Judgment will come from the LORD... It will be like a dream, a night vision. There will be a horde from all the nations that fight against Ariel... It will be like a hungry man dreaming that he is eating, Only to awaken and find that his stomach is empty. It will be like a thirsty man dreaming that he is drinking, Only to awaken and find that he is still weak and his thirst unquenched" (Isa 29:6-8).

18 "For this reason deliverance is far from us and salvation does not reach us. We wait for light, but see only darkness; We wait for a bright light, but live in deep darkness. We grope along the wall like the blind, We grope like those who cannot see; We stumble at noontime as if it were evening. Though others are strong, we are like dead men" (Isa 59:9-10).

19 ".Indeed, in a night it is devastated, Ar of Moab is destroyed! Indeed, in a night it is devastated, Kir of Moab is destroyed!" (Isa 15:1).

20 "Then the LORD will create over all of Mount Zion and over its convocations a cloud and smoke by day and a bright flame of fire by night; Indeed a canopy will accompany the LORD's glorious presence. By day it will be a shelter to provide shade from the heat, As well as safety and protection from the heavy downpour (Isa 4:5-6). I, the LORD, protect it; I water it regularly. I guard it night and day, so no one can harm it" (Isa 27:3).

21 Claus Westermann, Isaiah 40-66 (Transl. David M.G. Stalker from the German, OTL; London: SCM Press, 1969)107.

22 Coggins, "In Wrath Remember Mercy", 11; R. Mason, Micah, Nahum, Obadiah (Old Testament Guides; Sheffield: JSOTSS Press/Sheffield Academic Press, 1991), 57.

23 Mason, Micah, 81.

24 Coggins, "In Wrath Remember Mercy", 7, 12; Mason, Micah, 83; Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 196.

25 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 198.

26 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 201; R.J. Coggins, Haggai, Malachi, Zechariah (Old Testament Guides; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987), 34.

27 Coggins, Haggai, Malachi, Zechariah, 34. For more on the book of Haggai, see Kessler (2002).

28 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 167, 207. Note Jones, The Formation of the Book of the Twelve, 156-161 who draws an extensive relationship between Malachi and the book of Jonah especially with regards to the question of theodicy and of divine justice.

29 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 174.

30 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 174, 177.

31 Cf. Hosea 6:3-4; 7:6; 10:15 and 13:3 for references to the morning.

32 Hasel, Understanding the Book of Amos, 17.

33 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 182, 185.

34 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 186. See also Hasel, Understanding the Book of Amos, 107.

35 Olojede, "What of the Night", 733.

36 With twenty-one verses, Obadiah is the shortest Old Testament book. Richard J. Coggins, "Judgment between Brothers: A Commentary on the Book of Obadiah", in Israel among the Nations: A Commentary on the Books of Nahum and Obadiah and Esther (ed. Richard J. Coggins and Paul S. Re'emi; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1985), 67-100 (67). Mason, Micah, 87).

37 Although the oracles are aimed specifically at Edom, Coggins asserts that, "Edom is becoming a symbol of all that stands in enmity to God". Coggins, "Judgment between Brothers", 76.

38 Coggins, "Judgment between Brothers", 68, 73; Johan Renkema, Obadiah (Historical Commentary on the Old Testament; Leuven: Peeters, 2003), 39.

39 Coggins, "Judgment between Brothers", 73.

40 Renkema, Obadiah, 134. In Renkema's view, "The fact that the night is mentioned as the time of the robbery leads one to the conclusion that we are dealing here with the secret operations of thieves. For this reason we opt for the translation 'burglars in the night', which respects both the element of violence and that of secrecy". Renkema, Obadiah, 133-134.

41 See for example, Jonah 2:1//Ps 130:1-2; Jonah 2:2//Pss 18:4-6; 22:24; 86:13; 88:17; 120:1. Various other allusions to different parts of the Psalms are visible in Jonah's prayer.

42 Wilheim Wessels, "YHWH, the God of New Beginnings: Micah's Testimony", HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 69/1 (2013), Art. #1960, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/.

43 Mason, Micah, 19; Smith-Christopher, Micah, 28.

44 Mark McEntire, A Chorus of Prophetic Voices: Introducing the Prophetic Literature of Ancient Israel (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2015), 70.

45 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 193.

46 Mason, Micah, 14. See also Wessels, "YHWH, the God of New Beginnings".

47 Mason, Micah, 11.

48 Mason, Micah, 19.

49 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 192. McEntire asserts that, "Micah 3 ends with the vision of Jerusalem as a "plowed... field" and "a heap of ruins." The land and houses that these people coveted and confiscated will be taken away or destroyed by a foreign enemy". McEntire, A Chorus of Prophetic Voices, 71.

50 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 193.

51 Micah 2:1 declares woe upon those who devise wicked schemes on their beds and carry them out when the morning breaks.

52 Daniel L. Smith-Christopher, Micah: A Commentary (OTL; Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2015), 117.

53 Smith-Christopher, Micah, 116. Smith-Christopher further explains that, "The term for "revelation" (or "divination") is also used to speak of a "diviner," a qôsëm (Isa 3:2; Zech 10:2); thus the root term is used to speak of divination, and usually the forbidden variety (e.g., Deut 18:10, 14; 1 Sam 6:2; Isa 44:25). In short, what we have is a general condemnation from Micah, cast in vocabulary that speaks of the typical work of prophets: divining, seeing visions, reporting God's intentions. For Micah, these are no longer reliable sources!" Smith-Christopher, Micah, 116.

54 Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 203.

55 Coggins, Haggai, Malachi, Zechariah, 40.

56 Coggins, Haggai, Malachi, Zechariah, 41, 48. Coggins also points out that, "The opening words of Malachi are... identical with those of Zech. 9.1; 12.1; the closing words (4.5f.) also show some similarity with Zechariah in that they are concerned with the re-interpretation of earlier prophetic material". Coggins, Haggai, Malachi, Zechariah, 72.