Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.31 n.3 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2018/v31n3a15

ARTICLES

Inner-biblical Allusion in Habakkuk's משא (Hab 1:1-2:20) and Utterances Concerning Babylon in Isaiah 13-23 (Isa 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10)1

Gert Prinsloo

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Inner-biblical allusions in Habakkuk's משא (Hab 1:1-2:20) and משאות concerning Babylon in Isaiah 13-23 (Isa 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10) suggest a shared circle of tradition and the reinterpretation of prophetic messages in developing social and political circumstances. Habakkuk 's משא condemns violent behaviour (1:5-11, 12-17; 2:5-20), but with the exception of משא ("the Chaldeans") in 1:5, shows a surprising reluctance to name the perpetrators of violence overtly. An analysis of inner-biblical allusions in Hab 1:1-2:20 and Isa 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10 -where Babylonian arrogance is overtly condemned - facilitates a contextual interpretation of both prophetic corpora, throws light on the identity of "the wicked" in Habakkuk, and makes an (original) exilic setting for Hab 1-2 a distinct possibility. Habakkuk's might be deliberately vague about the identity of the wicked because of their ominous presence in the concrete living conditions of its audience.

Keywords: Habakkuk, Isaiah, inner-biblical allusion, Babylon, prophetic tradition

A INTRODUCTION

Two observations prompted the brief investigation I conduct here. The first is that superscripts (1:1; 3:1) demarcate two distinct units in the book of Habakkuk.2 The first part (1:1-2:20) is characterised as המשא "the (divine) message," the second (3:1-19) as תפלה "a prayer,"3 both ascribed to חבקוק הנביא "Habakkuk the prophet." The משא is specific and designates a message originating in the divine sphere directed to the human sphere.4 The תפלה is indefinite, hypothetically one amongst many prayers, and as a prayer, it is directed from the human sphere to the divine sphere. In Habakkuk's משא communication is "top-down," in his תפלה it occurs "bottom-up." Each superscript suggests its own social context and mode of reception, while the combination of the two genres creates a third social context and mode of reception.5 In a משא, receivers of the message expect a specific people/group to be the "target" for divine intervention.6 In a תפלה, receivers expect a supplicant to pray fervently for divine intervention and confess his/her complete dependence upon Yhwh.7 Habakkuk's משא (1:1-2:20) is the explicit subject of this study. I hypothesize that the משא originated under specific social and historical circumstances and that inner-biblical allusions in the משא and anti-Babylonian utterances in Isaiah's משאות concerning the nations (Isa 13-23) provide hints to reconstruct these circumstances.

The second observation is the absence in Habakkuk's משא of any name of a people/group/person as the cause for divine intervention. Prophetic figures in the Hebrew Bible are usually not reticent in denouncing perpetrators of social and political evil. Some random examples illustrate the point. Amos denounces inner-Israelite injustice when he calls the privileged women of Samaria "you cows of Bashan on Mount Samaria... who oppress the poor and crush the needy" (Am 4:1). Obadiah promises the Edomites that "everyone in Esau's mountains will be cut down in the slaughter'" (Ob 8-9). Israel/Judah's archenemies, Assyria and Babylonia, are singled out for harsh judgement. Nahum tells the king of Assyria that he will be fatally wounded and that "everyone who hears the news about you claps his hands at your fall, for who has not felt your endless cruelty?" (Nah 3:18-19). In Isaiah, Yhwh warns the Assyrians: "I will crush the Assyrian in my land; on my mountains I will trample him down" (Isa 14:25). The Babylonians receive a similar warning: "Babylon, the jewel of kingdoms, the glory of the Babylonians' pride, will be overthrown by God like Sodom and Gomorrah" (Isa 13:19).

Against this background, the lack of "focus" in Habakkuk's משאI (1:12:20) is puzzling. The existence of violence and its devastating effect upon society are described. The terms חמס "violence" and שד "plundering" initiate the lament uttered in 1:1-17 (חמסI, 1:2, 3; שדI 1:3) and חמס is repeated twice in the woe-exclamations (2:8, 17). Violent acts are described at length in 1:6-11 and 1:13-17 and in the woe-exclamations (cf. 2:8, 12, 17). Violence results in the disintegration of society, characterised by trouble and suffering (1:3), strife and contention (1:3), to Torah losing its effectiveness (1:4); and to justice not materializing (1:4) or materializing in a perverted guise (1:4). Yhwh's inaction (1:2), inexplicable apathy (1:3, 13), and astounding actions on behalf of the Chaldeans (1:5-6) are identified as the root cause of the disintegration of society, to such an extent that the credo of the believing community as expressed in 1:12 - Yhwh is from eternity, personally involved, holy, and the guarantor of life -can be called in question.

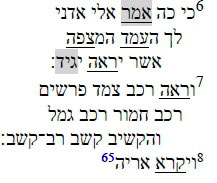

However, the perpetrators of violence are, with the single exception of 1:6's הכשדים "the Chaldeans," never overtly identified.8 The reference to "the Chaldeans" and their ensuing description as הגוי המר והנמהר "the bitter and the impetuous nation" (1:6) identify them as the subject of the violent acts described in 1:6-11. These acts are not condemned. On the contrary, Hab 1:5-6 implies that, astonishing as it may seem, Yhwh is the driving force behind the Chaldeans' military success (cf. כי־הנני מקים את־הכשדים "yes behold, I am raising the Chaldeans"). Elsewhere in the book, רשע is used as designation for the perpetrators of violence, twice in 1:1-2:20 in opposition to the noun צדיקI (1:4, 13) and once in 3:13.9 A feature of the book not properly appreciated is that it does not contain a single reference to "the" wicked. In all three cases, רשע occurs as an indefinite noun. The book does not focus on the identity of the wicked, but rather on the question why wickedness persists.10

This is confirmed by other vague references to the perpetrators of violence. In 1:13, Yhwh is accused of looking upon בגדים "treacherous ones." In 2:4, one would expect the expression וצדיק באמונתו יחיה "but a righteous person, by his/its faithfulness will live" (2:4b) to be balanced by an antithetical statement regarding "a wicked person" (cf. 1:4, 13). However, the enigmatic expression הנה עפלה לא ישרה נפשו בו "behold, puffed up, not straight is his innermost being in him" occurs.11 Habakkuk 2:5 mentions גבר יהיר "an arrogant person" who is deceived by היין "the wine," and whose insatiable appetite to "gather to himself all the nations" and to "collect to himself all the peoples" is likened to שאול. This "arrogant person" becomes the object of a משל "proverb" or מליצה חידות "satire (containing) riddles" uttered by the very same nations (2:6) by means of five הוי

exclamations (2:6-20). The arrogant person is defined as המרבה לא־לו "someone who increases what is not his" and מכביד עליו עבטיט "someone who makes himself glorious by pledges" (2:6); בנה עיר בדמים "someone who gains wicked profit for his house" (2:9); בנה עיר בדמים "someone who builds a city with blood" and כונן קריה בעולה "someone who establishes a town with violence" (2:12); משקה רעהו "someone who makes his neighbour drink" and "מספח חמתך" you who mix your intoxicating drink" (2:15); אמר לעץ הקיצה עורי לאבן דומהאמר לעץ הקיצה עורי לאבן דומה"someone who orders a piece of wood: 'awake!', 'arise!' to a silent stone" (2:18). However, the arrogant person's identity is not revealed.12

In Habakkuk's history of interpretation this peculiarity has been a crucial issue; consequently, the problem of the identity of the wicked received much attention.13 Currently a "consensus" seems to have emerged regarding this issue, namely that the צדיק in Habakkuk refer to pious Judeans, while two parties are involved in the designation רשע, namely Judean evildoers and the Babylonians. The consensus is modified by scholars maintaining that the רשע in the book can consistently be identified with the Babylonians and that Habakkuk "originally protested to Yhwh concerning the evil brought about by the emergence of Babylon as an enemy to Judah, and was subsequently surprised to learn that Yhwh was responsible for the rise of Babylon."14 Broadly speaking, the activity of the prophet (not necessarily the book) is placed between the last years of Josiah (640-609 bce) and the reign of Jehoiakim (609-598 bce) and Jehoachin (598 bce).

In synchronic readings of the book, it is assumed that 1:2-4 is a prophetic lament about an inner-Judean conflict between the צדיק and the רשע or to the devastating effect of wickedness upon society in general. In 1:5-11 the Chaldeans are announced as Yhwh's instrument to "correct" wickedness. Their excessive violence, however, enhances the disintegration of society, hence they become the object of the prophet's renewed lament about violence (1:12-17). In 2:1-20 Yhwh announces the destruction of this wicked empire. Synchronic readings often presuppose that time elapsed between the prophetic activity recorded in 1:2-11 and 1:12-2:20. Adherents of diachronic readings propose that Habakkuk consists of a pre-exilic kernel lamenting and denouncing inner-Judean social atrocities associated with the reigns of Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim and Jehoiachin. Intertextual links between Habakkuk and Jeremiah's description of these kings' reigns (cf. Jer 22:11-30) are cited as proof of this position. This kernel was expanded and re-interpreted in various redactional phases during the late pre-exilic, exilic, and post-exilic periods. A rebuttal of inner-Judean injustices has thus been transformed into an anti-Babylonian and anti-imperialistic book.15

The present study approaches the problem of the "vague" references to the perpetrators of violence in Habakkuk from another vantage point, arguing that inner-biblical allusions provide a hint to the identity of the perpetrators of violence in Habakkuk's משא. Previously, I made the following cursory remarks with regard to the book of Habakkuk:16

The book shows a curious reluctance to identify the wicked. Habakkuk 1:1 classifies the following material as a משא, but never reveals against whom it is directed... The wicked remains a mysterious character. Yet there are hints that the Babylonians are the object of the scorn, the nation on whom imminent doom is pronounced. The main indicator is the many parallels between Hab 2 and oracles of doom in Isaiah directed against the Babylonians (cf. Isa 13-14; 21:110). Might the reluctance to identify the wicked be an indication that the lived space of the prophet is severely threatened, might he even be in exile, among the very people whose violent behaviour is repeatedly condemned? Might it be an indication that covert identification of the wicked has been necessitated by their proximity to the prophet?

I now substantiate these cursory remarks in two ways. First, I give a brief overview of intertextual links between the books of Isaiah and Habakkuk in defence of the thesis that the book of Habakkuk can be associated with tradition circles responsible for the redaction and compilation of the book of Isaiah.17Second, I discuss unrecognised or under-emphasised thematic allusions in Habakkuk's משא (Hab 1:1-2:20) and Isaiah's משאות concerning Babylon (Isa 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10) to defend the following thesis: Habakkuk 1:1-2:20 is linked to the Isaiah tradition and displays concerns of the exilic community. It condemns the arrogant behaviour of the Babylonian tyrant and expects the soon to be realised eschatological intervention of Yhwh in world history and his final victory against the wicked tyrant. Habakkuk's משא is closer in time and space to the tyrant than the anti-Babylonian passages in Isaiah, hence it is circumspect regarding the identity of the perpetrator, but vehement in its condemnation of Judah's archenemy.18

The present study falls in the broad field of so-called "intertextual" analysis, which can be defined as "the way that scripture uses scripture."19Spatial constraints do not allow for a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of different approaches to intertextual analysis in biblical studies.20

Methodologically speaking, identification of intertextual links can be classified as either "reader-orientated" or "author-intended."21 The first is a purely synchronic exercise, the latter a diachronic attempt to identify deliberate links between different biblical texts and to determine the direction of influence and hence the relative dating of perceived intertexts.22 My careful avoidance of the term "intertextuality" and deliberate use of the term "inner-biblical allusion" in this study's title suggest that I engage in an analysis of "author-intended" allusions in Habakkuk's משא (Hab 1:1-2:20) and Isaiah's משאות concerning Babylon (Isa 13:1-14:27; 21:1-10).23 I use allusion as an umbrella term to designate an author's intentional evoking of another text with which his/her audience is acquainted. The "connotations of the evoked text interact with the alluding text."24

B ISAIAH AND HABAKKUK: A SHARED TRADITION CIRCLE?25

Over the past number of years, several publications drew attention to textual links between the books of Habakkuk and Isaiah. I briefly summarise the views of three studies and then make some general remarks regarding the viability of a so-called Isaiah tradition circle.26

Gerald Janzen focuses on two intertextual contexts for Hab 2:2-4,27 a wisdom context in parallels between Hab 2:2-4 and Proverbs (6:19; 14:5, 25; 19:5, 9; 12:17),28 and a prophetic context in parallels between Hab 2:2-4 and passages in Isaiah.29 Parallels between Hab 2:2-3 and Isa 40:1-30 (cf. רוץI "run" and חכה "wait" in Hab 2:2-3; Isa 40:31) suggest the proper response to Yhwh's eschatological message, namely "to exercise patience in its two fundamental modes of action and passion."30 The command to write Yhwh's message upon tablets (Hab 2:2) is reminiscent of Isa 8:1-4 and 30:8-18. In Isa 8:1-4, Yhwh's message is explicitly identified as a תורה "teaching" that should be bound up and sealed among Isaiah's disciples (למדים) as a witness to the reliability of Isaiah's message against the false messages of other prophets. In Isa 30:8-18, the prophet is instructed to write Yhwh's message on a tablet and to inscribe it in a book as a witness (עד; Isa 8:8) to the days to come because the people despise Yhwh's instruction (תורה; Isa 8:9) and reject his word (דבר; Isa 8:12). In Isa 30:15 Yhwh's basic intention and commitment towards Judah is clear: He waits (יחכה) to be gracious to them and show mercy to them, because he is a God of justice (משפט), and all who wait (חכה) for him are blessed. Janzen argues that Habakkuk stands "squarely in that living tradition which stretches from Isaiah to Second Isaiah, and that Habakkuk indeed is to be viewed as a vital and revitalizing middle term in that tradition."31

Michael E. W. Thompson argues along similar lines.32 The unusual combination of the apparently unrelated Gattungen "prayer, oracle and theophany" does not, as Robert P. Carroll would have it, characterize Habakkuk as "a ragbag of traditional elements held together by vision and prayer" that "illustrates the way prophetic books have been put together in an apparently slapdash fashion."33 On the contrary, "there is a definite progression of mood from despair to joy, from the statement of a theological problem to a satisfying resolution."34 The presence of traditional literary forms is complemented by the eclectic use of "the wisdom and Isaiah of Jerusalem traditions."35 The terms תוכחת (Hab 2:1), מדון (Hab 1:3), עמל (Hab 1:3, 13) and the antithesis between רשע and צדיק (Hab 1:4, 13) are closely associated with Israel's wisdom corpus. Habakkuk also shares the theodicy theme with the Psalms, Job and Qohelet. The book's dialogic character is reminiscent of these literary contexts and the book shares with Job a structural outline commencing with lament but concluding with theophany.36

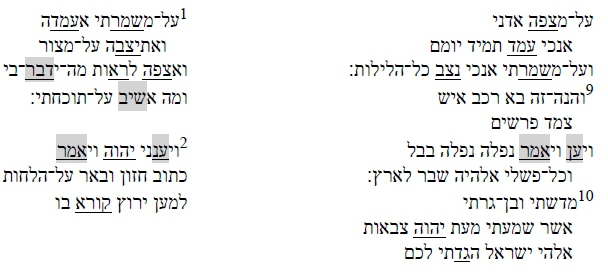

Habakkuk and Isaiah both take a stand upon a watchtower (Hab 2:1; Isa 21:8) and record divine revelations and anticipate its swift realization, but also advocate patient "waiting" (Hab 2:2-3; Isa 8:4; 30:8). They are both concerned with the manifestation of Yhwh's פעל "work" (Hab 1:5; Isa 5:12); share the awareness that Yhwh uses the great nations as agents of judgement (Hab 1:12; Isa 7:20; 10:5-6); and are critical of the role empires play in the divine "plan" (Hab 1:12; Isa 10:7-8). Both indicate that Yhwh will break the power of the empires that he also utilizes (Hab 2:6-19; Isa 10:12, 14:24-27). The 'inexclamation in Hab 2:6 is reminiscent of the 'in-exclamation directed against the Babylonian king in Isa 14:4. Hab 2:14 is virtually identical to Isa 11:9b. Habakkuk also shares a commonality of style and approach with Isaiah 40-55. Both corpora display "psalmic" forms (Hab 3:3-15; Isa 42:10-13; 44:23; 49:13); focus upon Yhwh's glory and its effect upon creation (Hab 3:3-7, 10-11; Isa 40:5; 41:20; 43:21); proclaim that Yhwh employs foreign powers to serve his purpose (Hab 1:12-17; Isa 44:24-45:7); and condemn idol worship (Hab 2:1819; Isa 40:19-20; 41:6-7).37 Habakkuk "stood somewhere in the Isaiah tradition" where he "drew upon the message of Isaiah, interpreting it afresh for his own day." At the same time "in Habakkuk there is... that element of anticipation of what was yet to come in the prophecies of Second Isaiah."38

Walter Dietrich comprehensively defends the thesis that Habakkuk was a "disciple" of the Isaiah of Jerusalem tradition circle, as superscripts in the books (Hab 1:1; Isa 1:1; 2:1) suggest.39 In Hab 1:2-10 the prophet laments internal and external violence.40 His accusation that Yhwh does "not hear" (לא תשמעI, 1:2) and "save" (לא תושיעI, 1:2) when he calls "violence" (אזעק אליך חמסI, 1:2) echoes Isa 1:15's statement that Yhwh will "not listen" (אינני שמע) when people committing social atrocities pray to him. Isaiah 30:19 seems to answer these accusations when Yhwh promises to listen to Zion's call for help and to answer. Yhwh allows the prophet to see "trouble" (און) and he stares upon "suffering" (עמל, Hab 1:3) as in Isa 10:1 and 59:4. Habakkuk is a "bridge" between earlier and later Isaianic traditions. In Hab 1:5-10 the imminent rise of the Chaldeans is Yhwh's answer upon social injustice, the role attributed to the Assyrians in Isa 10:1-3. They will bring disaster from afar (ההולך למרחבי־ארץ, Hab 1:6; מרחוק יבואו, 1:8), which echoes Isa 5:26 (ונשא־נס לגוים מרחוק) and 10:3 (ממרחק תבוא). Habakkuk 1:5's "be astonished, be bewildered" (והתמהו תמהו) echoes Isa 29:9 (תמהמהו ותמהו); "for something is about to happen in your days" (כי־פעל פעל בימיכם) echoes Isa 5:12 (ואת פעל יהוה לא יביטו), and "you will not believe even if it were told" (לא תאמינו) echoes Isa 7:9 (אם לא תאמינו). Habakkuk 1:6 characterizes the Chaldeans as הגוי המר והנמהר "the bitter and the hasty nation." In Isa 5:19 the people of Judah sarcastically called upon Yhwh to "hurry" (ימהר) his work so they may "see" it (נראה; cf. ראו in Hab 1:5). In Isa 5:20 they call "bitter" (מר) for sweet and sweet for "bitter" (מר). Habakkuk 1:11 is a redactional addition and refers to Neo-Babylonian imperialism. The redactor assures readers that the power of the Babylonians will be short-lived; it will "pass by" (עבר) as Isaiah warned Judean rulers that when the Assyrian storm passes them by (עבר, Isa 28:15, 18) they will be left trampled. The redactor accuses Babylon that their own power is their god (זו כחו לאלהוI; 1:11), as Isaiah accused the Assyrians of undue confidence in their own power (בכח ידי עשיתי; Isa 10:13).

Significant parallels exist between Hab 1:12-13; 2:1-4 and Isaiah.41 In Hab 1:12-13 the prophet laments Yhwh setting "him" up for "judgement" למשפט שמתו and establishing "him" for "rebuke" (להוכיח יסדתו). The subject of the third person masc sing suffix is not immediately clear. In Isa 11:3-4 (cf. also Isa 2:4//Mic 4:3) משפט and יכח refer to the Messiah. Dietrich argues that Habakkuk's use of the terms expresses his disappointment in the last kings of the Davidic dynasty who rejected Yhwh as their "rock" Hab 1:12). In Isa 28:14-19 Isaiah assured those who rejected Yhwh that he will establish in Zion a tested "stone" (הנני יסד בציון אבן אבן בחן, Isa 28:16) and make "justice" the measuring line (ושמתי משפט Isa 28:17). In Hab 1:14, the Babylonians are accused that they treat humankind as insects "without a ruler" (לא־משל בו). Dietrich regards Hab 1:14-17 as an exilic addition condemning Babylonian expansionism when there no longer was a king in Judah. The imagery of the imperialistic nation as a fisherman is unique in the Hebrew Bible, but the gist of the section reflects the Isaiah tradition where not only violence in Judah, but also violence done to Judah is condemned. The critique in Hab 1:16 (cf. 1:11) that the imperialistic power elevates its own power to the divine sphere foreshadows Deutero-Isaiah's insistence that the God of Israel is the only divine being. In Hab 2:1, the prophet prepares himself for an encounter with Yhwh. Yhwh's answer (Hab 2:2-3) has close parallels in Isaiah. Habakkuk must "inscribe" the "vision" (כתוב חזון, Hab 2:2) as Isaiah did (כתב, Isa 8:1). Habakkuk 2:2-3 states that the vision is intended for a specific time; if it "tarries" (מהה, Hab 2:3) the prophet must "wait" upon it (חכה, Hab 2:3). It echoes the name of the son that Isaiah had to inscribe (מהר שלל חש בז "soon spoil, quickly plunder," Isa 8:3). In Isa 8:16-17, the prophet decided to "bind up the testimony and seal up the law among my disciples" and to "wait for the LORD (וחכיתי ליהוה). Habakkuk 2:2-3 also echoes Isa 30:8-11. Habakkuk must write his vision "on tablets" (על־הלחות כתוב חזון, Hab 2:2) as Isaiah did in Isa 30:8-11 (עתה בוא כתבה על־לוח, Isa 30:8) as a lasting witness for the days to come (ליום אחרון, Isa 30:8; cf. לא יאחר Hab 2:3). In Isa 30:10, the rebellious people are accused that they told the seers "do not see!" (אשר אמרו לראים לא תראו; cf. ראה in Hab 2:1) and the visionaries "do not give us visions of what is right!" (ולחזים לא תחזו־לנו נכחות; cf. חזה, Hab 2:2-3; יכח, Hab 2:1).

The 'in-exclamations in Hab 2:5-20 echo the series of 'in-exclamations in Isa 5:8-24.42 Dietrich detects two redactional layers in the exclamations. The first layer is directed against inner-Judean social atrocities. Habakkuk 2:5's גבר יהיר "an arrogant man" echoes the condemnation of Shebna in Isa 22:15-25 (cf. גבר in Isa 22:16; גבר in Isa 22:17) as well as the 'הוי-exclamation in Isa 5:11-19. Both exclamations refer to drinking (היין in Hab 2:5;43 שכר/יין in Isa 5:11-12) and the warning in Isa 5:14-15 that the Judean leaders will be swallowed by שאול serves as warning to the arrogant in Hab 2:5 who "makes as wide as שאול his gullet." The denouncement of one "who makes himself glorious" (מכביד) by pledges (Hab 2:6b-7) echoes instances in Isaiah where the root כבד characterizes influential Judeans (Isa 5:13; 10:3; 22:18). In Hab 2:9-11 the denouncing of one who "gains wicked profit for his house" (ביתו) and sets "on high (במרום) his nest" (2:9) echoes Isa 22:16 (מרום) and 3:13 (בבתיכם). In Hab 2:12 the prophet denounces one "who builds a city (עיר) with blood" and "establishes a town (קריה) with violence." It echoes Isaiah lamenting the fact that the "faithful city" (קריה נאמנה) has become a harlot (Isa 1:21) and his hope that Jerusalem will once again become a "city of righteousness" (עיר הצדק) and a "faithful city" (קריה נאמנה, Isa 1:26). Isaiah denounced excessive drinking in Isa 5:11.22 (cf. שתה,שכר), while in Hab 2:15a.16 similar imagery becomes a metaphor for excessive violence.

The redactional additions focus upon Babylonian imperialism. In Isa 10:14 the prophet denounces the Assyrians' attempt to "gather" (אסף) all nations, as Habakkuk did with the Babylonians (cf. ויאסף אליו כל־הגוים "and he gathered to himself all the nations" in 2:5). In Hab 2:7 the perpetrators of violence are accused that they "plundered" (שלות) many nations, while in Isaiah the Assyrians are sent "to seize prey" (לשלל שלל Isa 10:6; cf. 8:4). The nations (גוים) labouring (יגע) for the sake of fire and the peoples (לאמים) becoming wary )יעף( for the sake of vanity while the earth is filled (תמלא) with the glory of Yhwh (כבוד יהוה, Hab 2:13-14) echo the phrase מלא כל־הארץ כבודו "the whole earth is full of his glory" in Isa 6:3. Habakkuk 2:13-14 is the "fulfilment" of the almost identical words in Isa 11:9 (כי־מלאה הארץ דעה את־יהוה כמים לים מכסים). These words are then echoed in several passages in Deutero-Isaiah (cf. יגע in Isa 40:28, 30, 31; 43:22, 23, 24; 47:12, 15; 49:4; 57:10; יעף in Isa 40:28, 29, 30, 31; 44:12). יהוה צבאות (Hab 2:13) is also a favourite Isaianic designation for the deity.44 Finally, the polemic against idols in Hab 2:18-19 is very close to similar passages in Deutero-Isaiah.

For Dietrich the connections between Habakkuk and Isaiah suggest that Habakkuk could be regarded as "ein Mitglied der Jesaja-Schule."45 It does not imply that he is an "unselbständiger Plagiator."46 He is "ein eigenständiger Schüler,"47 but "lebt im jesajanischen Geist."48 Jacques van Ruiten denies the significance of the intertextual connections between Habakkuk and Isaiah. He asserts that other intertexts (notably the Psalter and Job) also display significant links with Habakkuk.49 Van Ruiten concludes that "it is very difficult to confirm the view that Habakkuk is dependent on Isaiah" and argues that "Habakkuk does not speak in 'his master's voice'!"50 He also states that Dietrich's method is "too general and too informal" and does not prove "dependency of one text on the other."51 I now turn to Habakkuk's משא (Hab 1:1-2:20) and Isaiah's משאות directed at Babylon (Isa 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10) to argue that the recognition of Habakkuk and Isaiah as intertexts is not limited to highlighting similar words "all over the place." It can be substantiated with reference to quite specific contexts. Surprisingly these inner-biblical allusions have received little attention in scholarly discussions.52

C HABAKKUK'S משא (HAB 1:1-2:20) AND ISAIAH'S UTTERANCES CONCERNING BABYLON (ISA 13:1-14:23; 21:110) AS INTERTEXTS

Shared themes between Isa 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10 and Hab 1:1-2:20 in general and Hab 2:1-20 in particular suggest a close connection between these two specific contexts. In the following discussion, I focus on six themes where Habakkuk and Isaiah share a tradition, but the Isaiah contexts state explicitly what is implicit in the Habakkuk context.

1 The genre designation משא

The superscripts in Hab 1:1, Isa 13:1 and Isa 21:1 are an obvious starting place for our intertextual investigation.

Hab 1:1 חבקוק הנביא המשא אשר חזה

Isa 13:1 אשר חזה ישעיהו בן־אמוץ משא בבל

Isa 21:1 53משא מדבר־ים

The three superscripts share the designation משא. As a superscript, משאoccurs exclusively in the prophetic corpus and it is indicative of a specific prophetic literary genre "that designates a type of prophetic discourse in which the prophet attempts to delineate divine actions in human affairs."54 It is especially prominent in the utterances concerning nations in Isa 13-23, where it occurs ten times.55 It occurs one more time in Isaiah, once in Nahum, Habakkuk, and Malachi, and twice in Zechariah.56 The "topic of a massä' is... always some person, group, situation, or event" and it is "based on a particular revelation (given to the prophet) of the divine intention or of a forthcoming divine action."57 It carries undertones of judgment and implies that Yhwh is about to intervene in the history of the nations and/or his people.58 These utterances "are directed primarily to Israel and designed to explain events in the world of affairs as an act of Yahweh."59 Significantly, in Hab 1:1 the object of the משא is not stated. It is, in fact, the only משא without any explicit object.60 This has implications for any consideration of intertextual links between Habakkuk and the other prophetic משאות Michael Thompson quite rightly argues that "this word finds its most consistent employment in the oracles against the nations in Isa 13-23," which implies that "(p)erhaps we are intended to understand that a concern in Habakkuk is with a word of judgement against a foreign nation."61

2 Yhwh and the rise and fall of empires

A second shared theme is that of Yhwh as ultimate director of international affairs and his crucial role in the rise and fall of the Babylonian Empire.

Both contexts emphasise Yhwh's imminent intervention (הנני + participle) in and control over the nations. Significantly, in Hab 1:6 there is no indication of the recipients of Yhwh's imminent intervention. It is simply stated that he plays an active role in raising the Chaldeans as a destructive force on the plane of world history. Taking the statement purely at face value, nothing overtly negative is said against the Chaldeans. A completely different picture emerges in Isa 13:17. Now Yhwh is overtly stirring an enemy against the Babylonian Empire. Both contexts suggest Yhwh's ultimate control over the destiny of all peoples, not only Israel. However, in Habakkuk his control over the Babylonians contains no condemnation of their violent behaviour, while Isaiah predicts the destruction of Babylon's pride (13:19). Significantly, in Isa 41:25 the verb -17 is used to indicate that Yhwh is stirring Cyrus as the ultimate agent of Babylon's downfall and the salvation of his people.62 The same motif is prominently present in Jer 50-51. The Chaldean ascendency pronounced in Hab 1:6 is predicted to come to a disastrous end in Isa 13:17, and the theme is fully developed in Isa 4048 and Jer 50-51.63

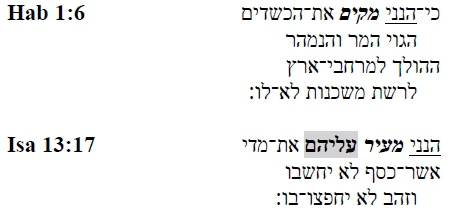

3 The prophet as watchman

A third shared theme is the notion of the prophet as watchman, present in Hab 2:1 and Isa 21:6-10. The motif often occurs in the prophetic corpus (cf. Isa 52:8; 56:10; Jer 6:17; Ezek 3:17; 33:2, 6, 7; Mic 7:4, 7). Habakkuk 2:1 and Isa 21:610, however, share a unique feature - what might be called a Motivkonstellation - not present in any of the other "watchman" texts.64 It is apparent when Hab 2:1 and Isa 21:6-10 are compared in terms of shared vocabulary:

Habakkuk 2:1-2 Isaiah 21:6-10

The two contexts share the roots שמר,עמד,צפה,ראה and the cognate forms יצב/נצב and יאמר/דבר. In both contexts the expectation is that the watchman will react verbally upon what is seen (cf. דבר/שוב in Hab 2:1; אמר/נגד in Isa 21:6; קרא in Isa 21:8). The "watchman-scene" is followed in both cases by a reaction containing the roots ענה "answer" and אמר "say" (ויענני יהוה ויאמר in Hab 2:2a; ויען ויאמר in Isa 21:9c). The Isaiah-scene undoubtedly suggests a military context (21:7, 9). The parallels between the Isaiah-scene and the Habakkuk-scene open the possibility that Habakkuk's stationing upon a bulwark and watchtower does not necessarily imply a cultic, but a military context. In this context, the report of the watchman in Isa 21:9 becomes quite significant. Upon seeing the approaching riders and horsemen in pairs, he cries out: נפלה נפלה בבל וכל־פסילי אלהיה שבר לארץ "fallen, fallen is Babel, and all the images of her gods he has shattered to the earth!"66 The last הוי-exclamation in Habakkuk (2:18-19) with its strong anti-idol polemic shares the word פסל "carved idol" with Isa 21:9 (Hab 2:18). In Hab 2:18 the carved idols are derogatorilycalled אלילים אלמים "dumb godlets," reminiscent of וכל־פסילי אלהיה in Isa 21:18. Isaiah 21:9 explicitly says what is implied in Hab 2:1, 18-19. Perpetrators of violence, in Isa 21:9 specifically identified as the Babylonians, face an even more violent (military) end, and the prophet of Yhwh testifies that the Babylonian gods will not be able to protect them against their inevitable end.

4 Pride will have a fall

In spite of a multitude of text-critical problems, the gist of Hab 2:4 is clear. An arrogant person (עפל) has no future, while a righteous person (צדיק) will live. This message is guaranteed by the trustworthiness (באמונתו) of Yhwh's word that Habakkuk had to inscribe upon tablets (Hab 2:2-3). This message is confirmed in Hab 2:5 and elaborated upon in the הוי-exclamations in Hab 2:6-20. An

arrogant person (גבר יהיר) is being misled (בוגד) by the intoxicating lust for power (היין) and "he will not succeed" (ולא ינוה). In Hab 2:4-5 and in the 'in-exclamations in 2:6-20 the identity of the arrogant person is not revealed. The theme of arrogance is also present in the משא בבל in Isa 13:1-14:23, but there the identity of the haughty is no secret. The theme of arrogance plays a central role in the announcement of the יום יהוה' in Isa 13:6-22. In Isa 13:11 Yhwh pronounces:

ופקדתי על־תבל רעה I will visit evil upon the world,

ועל־רשעים עונם and upon the wicked their sins.

והשבתי גאון זדים I will put an end to the arrogance of the haughty,

וגאות עריצים אשפיל׃ and the pride of the ruthless I will bring down.

Yhwh will "put to an end" ('והשבתיI, 13:11; cf. also 21:2) the "arrogance of the haughty" (13:11) by "stirring up" the Medes (הנני מעיר עליהם את־מדיI 13:17; cf. כי־הנני מקים את־הכשדיםI, Hab 1:6). The result is spelled out in Isa 13:19:

והיתה בבל צבי ממלכות Babylon will be - the glory of kingdoms,

תפארת גאון כשדים the splendour of the pride of the Chaldeans -

כמהפכת אלהים את־סדם ואת־עמרה׃ like a destruction by God, Sodom and Gomorrah!

In Isa 14:4, the object of Yhwh's wrath is defined even more precisely. It is "the king of Babel" (מלך בבל) whose power is broken (14:4-8) and who descends into שאולI (14:9) to the astonishment of the "kings of the nations" already residing in that grim place. They identify the reason for his descent into שאול in Isa 14:11: "Your arrogance (גאונך), the noise of your harps, has been brought down to שאול." The "defeater of nations" regarded himself as the "morning star, son of dawn" (14:12) and proclaimed: "To heaven I will ascend, above the divine stars I will raise my throne, I will sit on the mountain of assembly, the uppermost regions of Sâpôn, I will ascend above the heights of the clouds, I will compare to the Most High" (14:13-14).67 But pride will have a fall, as the "kings of the nations" proclaim: "However, to שאול you were brought down, to the innermost of the pit" (14:15). Babylon's fall is finally confirmed by Yhwh in 14:22:

וקמתי עליהם נאם יהוה צבאות I will stand up against them - declaration of YHWH Sebâ'ôt,

והכרתי לבבל שם ושאר and I will destroy for Babylon name and remnant,

ונין ונכר נאם־יהוה offspring and posterity - declaration of YHWH.

Habakkuk's mysterious גבר יהירI (2:5) is overtly identified in Isaiah as the mighty Babylonians and their arrogant king.68

5 Taunting him to שאול

In Hab 2:5, the mysterious גבר יהירis likened to שאול. He has an insatiable appetite (cf. Isa 5:14) to "gather to himself all nations" and to "collect to himself all peoples." But Hab 2:6 warns that pride will have a fall. The very same nations will "lift up a proverb/taunt" (משל ישאו) and a "derisive riddle" (מליצה חידות) against him.69 This "proverb" or "derisive riddle" finds specific expression in the five 'in-exclamations, a genre especially associated with death and mourning rites. The subjected nations are taunting the tyrant to שאול, so to speak. Significantly, the same imagery occurs in Isa 14:4 where people "in suffering and turmoil" due to Babylonian tyranny are assured that the day will soon dawn when Yhwh will "give you rest... from the severe bondage that bounded you." Then "you will lift up this proverb/taunt against the king of Babylon and say" (ונשאת המשל הזה על־מלך בבל ואמרתI, 14:4). The taunt (Isa 14:4-21), introduced by איךI (14:4, 12) - a term also associated with death and mourning rites - implies the humiliation, indeed the total annihilation of the Babylonian king. The "oppressor has come to an end" and "his fury has ended" (14:4), "Yhwh has broken the rod of the wicked, the sceptre of rulers" (14:5) to bring "rest" to all the earth, even to the "cedars of Lebanon" because "now that you lie down, no woodcutter ascends against us" (14:8; cf. Hab 2:17). In Isa 14:9 שאול itself is astir to accept the arrogant tyrant in its midst. When Hab 2:5-6 and Isa 14:4-21 are read as inter-texts, שאול meets שאול, the Babylonian king suffers the ultimate humiliation of not being granted the honour of a proper burial (Isa 14:19-20).

6 Yhwh at-centre and the destruction of the wicked

In the 'in-exclamations in Hab 2:5-20 the crucial importance of 2:14 and 20 should be acknowledged. Both are key verses focusing upon the presence of Yhwh amidst the horror caused by violence and wickedness. The lamenting prophet of Hab 1:1-17 is encouraged by the eschatological vision (2:2-4) that must be inscribed upon tablets (2:2-3). It is a reliable witness to the trustworthiness of Yhwh's promise that wickedness will not prevail (2:4). Significantly, in the third 'in-exclamation (2:12-14), in the centre of the violent tyrant being "taunted" to שאול, the focus falls upon the irrelevant "labour" of the nations, of the peoples becoming "wary" in vain (2:13) in the presence of Yhwh:

כי תמלא הארץ For the earth will be filled

לדעת את־כבוד יהוה with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord

כמים יכסו על־ים׃ as the waters cover the sea.

It has already been pointed out that this verse is virtually identical to Isa 11:9, occurring in an eschatological passage with a distinct "Israel-centring."70The climax of Habakkuk's 'in-exclamations occurs in Hab 2:20:

ויהוה בהיכל קדשו But YHWH is in his holy temple,

הס מפניו כל־הארץ׃ hush before him, all the earth!

This text, appearing in almost identical guise in Zeph 1:7 and Zech 2:17, focuses exclusively on Yhwh's omnipotence in the seat of his power, his "holy temple." It implies the total annihilation of wickedness, and a new destination for the lamenting prophet: "Amid the turmoil of his lived experience as victim of violence (1:2-17) and spectator of incredible hardship (2:5-17), his imagined space becomes one of hushed reverence and peace... He has arrived at-centre!"71

A similar focus on Yhwh's central role in the destruction of the wicked Babylonians and their king is apparent in Isaiah's משאות concerning Babylon. Isaiah 13:1-14:2 plays an important role in this "centring" of Yhwh. The announcement of the terrible day of Yhwh (13:6-22) which will lead to the complete destruction of Babylon (cf. 13:19-22) at the hand of an army of "holy ones" mustered by יהוה צבאות' as "the instruments of his indignation to destroy all the earth" (13:3-5) is framed by passages focusing on Yhwh at-centre. In 13:2 this army, collected from "a distant land, from the end of heavens," is invited to "enter the gates of the nobles."72 The יום יהוה' announcement is concluded in 14:1-3 by a passage focusing on the reversal of the fate of Jacob/Israel. Yhwh will once again "have compassion" upon them, "choose" Israel and "settle them in their land" together with the "sojourner" who will "attach themselves to the house of Jacob." A complete reversal of roles will take place. Israel will take possession of the nations in "the land of Yhwh as manservants and maidservants," they will "make captives of their captors" and they "will rule over their oppressors." The possession of the Babylonians, on the other hand, will be completely destroyed (14:22-23). Significantly, in Isa 13:11 and 14:5, the destruction of the רשעים is explicitly announced.73 To the משא בבל is appended the assurance that what Yhwh has planned will materialize; nobody can thwart it (14:24-27). In Isaiah, as in Habakkuk, the manifestation of Yhwh's power at-centre implies life for the צדיקים and the total annihilation of the רשעים.

D HABAKKUK'S משא AND ISA 13:1-14:23; 21:1-10: DIRECTION OF INFLUENCE?

Thematic parallels between Habakkuk's משאI (1:1-2:20) and Isaiah's Babylon-משאותI (13:1-14:23; 21:1-10) suggest more than a "reader-orientated" perception of intertextual links. The constellation of motifs and themes is indicative of "author-intended" linking. Determining the direction of influence becomes a difficult task when we work with "layered" texts like those that we undoubtedly encounter in the Hebrew Bible, even more so when a book like Isaiah with a long and complicated history of redaction and composition is involved.74 Constraints of time and space dictate that I can only make cursory suggestions regarding the direction of influence between Hab 1-2 and Isa 13:1-14:23, 21:1-10.75

Isaiah 13-27 should not be interpreted as two independent units (the oracles against the nations, 13-23, and the so-called Isaiah-apocalypse, 24-27), but rather as a compositional unit with a distinctly eschatological perspective. Isaiah 24 closes a series of ten משאות rather than introduces an apocalypse.76 The ten משאות constitute a deliberately structured literary unit with Isa 20:1-6, the short narrative of prophet Isaiah appearing naked in public for three years, at the centre of the composition. Berges dates the episode to the Philistine revolt against Assyria in 713-711 bce and regards the symbolic action as "a warning against blind trust in Egyptian help against Assyria".77 The passage is preceded and followed by two series of five משאות. The sequence is Babylon (13:1), Philistia (14:28), Moab (15:1), Damascus (17:1) and Egypt (19:1) before and Babylon (21:1), Dumah (21:11), Arabia (21:13), Jerusalem (22:1) and Tyre (23:1) after the symbolic action.78 The last משא in each sequence is followed by a series of six ביום ההוא "on that day" utterances.79 All of this is indicative of deliberate composition.80

This composition is the result of a long process of redaction and composition dating from the eighth to the fifth century.81 Parts of the utterances against Philistia (14:28), Damascus (17), Cush (18), Egypt (19) and Jerusalem (20, 22) might go back to the eighth century and are directed against nations who incited "Judah and Jerusalem to anti-Assyrian policies."82 The collection of utterances underwent a process of "Babylonization" in the Isaiah tradition circle(s), hence Isa 13-23 is primarily concerned with "the fall of the Neo-Babylonian superpower and the resulting perspectives for post-exilic Jerusalem together with Zion."83 The strong anti-Babylonian sentiment is suggested by the fact that both series of משאות are introduced by an utterance concerning Babylon (13:1-14:23; 21:1-10).84 Isaiah 21:9's exclamation "fallen, fallen is Babylon" suggests the "collapse of the Babylonian superpower."85

Against this background, Habakkuk's approach to the tyrant becomes significant. On the one hand, parallels between Hab 1:1-2:20 and Isaiah's utterances against Babylon (13:1-14:23; 21:1-10) suggest a shared tradition. That tradition might well have been kept alive in scribal circles during the Persian period.86 They edited, compiled, preserved and applied the Isaiah of Jerusalem tradition to new lived experiences under Persian hegemony. On the other hand, Habakkuk's reticence to overtly identify the violent tyrant of his time suggests that Habakkuk preserves an earlier phase of the tradition. Habakkuk shares with Isa 13-27 the eschatological perspective, strong anti-imperialist and anti-oppressor sentiments, the focus on the motif of the centrality of Zion and Yhwh's omnipresence and omnipotence and the notion of the inevitable annihilation of wickedness,87 but Habakkuk does not express these sentiments openly and aggressively. I hypothesize that it reflects different lived experiences of the Isaiah tradents. Habakkuk represents an earlier phase when the Babylonians were still in power and Isaiah 13-27 a later stage when the Babylonians had already lost power and were no longer a physical threat. However, they became the symbol of the existence of violence and tyranny, oppression and suffering. Their demise was as urgently longed for in Habakkuk as in Isaiah.

E CONCLUSION

The point of departure in this study was the reticence in the book of Habakkuk to overtly identify the perpetrators of violence so prominent in the little booklet. I hypothesized that an intertextual reading might elucidate possible context(s) that might help to explain this characteristic of the book. A summary of "reader-orientated" approaches to intertextual links between Habakkuk and the Isaiah of Jerusalem tradition and an analysis of "author-intended" thematic links between Habakkuk's משא and the two משאות against Babylon in Isa 13:1-14:23 and 21:110 provided ample evidence to support the thesis that the book of Habakkuk can be located in the scribal traditions associated with the redaction and composition of the book of Isaiah. The fact that these two specific anti-Babylonian utterances contain Motivkonstellationen that are shared with Hab 1:1-2:20 suggest that the Babylonians are the perpetrators of violence in the book of Habakkuk. The two literary contexts have a shared tradition-historical and scribal tradition. The development of this tradition from the eighth to the fifth century explains the "vague" references to the Babylonians in Hab 1:1 -2:20. Habakkuk represents an earlier stage in the development of the eschatological expectation that Yhwh is about to conclusively and comprehensively intervene in the cosmos. The Babylonians were still in power and their very presence complicated overt identification of the perpetrators of violence. It suggests that Habakkuk's משאI (1:1-2:20) by and large reflects the concerns of the exilic community.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andersen, Francis I. Habakkuk. Anchor Bible. New York: Doubleday, 2001. [ Links ]

Begg, Christopher T. "Babylon in the Book of Isaiah." Pages 121-5 in The Book of Isaiah/Le Livre D'Isaïe: Les Oracles et Leurs Relectures Unité et Complexité de L'Ouvrage. Edited by J. Vermeylen. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 81; Leuven: Peeters, 1989. [ Links ]

Berges, Ulrich F. "Die Knechte im Psalter. Ein Beitrag zu seiner Kompositionsgeschichte." Biblica 81 (2000): 153-78. [ Links ]

_Isaiah: The Prophet and his Book. Translated by P. Sumpter. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2012. [ Links ]

_The Book of Isaiah: Its Composition and Final Form. Translated by M. C. Lind. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2012. [ Links ]

Beuken, Willem A.M. Jesaja 13-27. Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg: Herder, 2007. [ Links ]

_"Common and Different Phrases for Babylon's Fall and Its Aftermath in Isaiah 13-14 and Jeremiah 50-51." Pages 53-73 in Concerning the Nations: Essays on the Oracles against the Nations in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Edited by Else K. Holt, Hyun Chul Paul Kim and Andrew Mein. Library of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 612. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. Isaiah 1-39. Anchor Yale Bible. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Brueggeman, D.A. "Psalms 4: Titles." Pages 613-21 in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. Edited by Tremper Longman III and Peter Enns. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008. [ Links ]

Carr, David. "Method in Determination of Direction of Dependence: An Empirical Test of Criteria Applied to Exodus 34,11-26 and its Parallels." Pages 107-40 in Gottes Volk am Sinai: Untersuchungen zu Ex 32-34 und Dtn 9-10. Edited by M. Köckert and E. Blum; Veröffentlichungen der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft für Theologie 18. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2001. [ Links ]

_"The Many Uses of Intertextuality in Biblical Studies: Actual and Potential." Pages 505-35 in Congress Volume Helsinki 2010. Edited by M. Nissinen. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 148. Leiden: Brill, 2012. [ Links ]

Carroll, Robert P. "Habakkuk." Pages 268-9 in A Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation. Edited by R. J. Coggins and J. L. Houlden. London: SCM, 1990. [ Links ]

Childs, Brevard S. Isaiah. Old Testament Library. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001. [ Links ]

Cleaver-Bartholomew, David. "An Alternative Approach to Hab 1,2-2,20." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 17 (2003): 206-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09018320410001029 [ Links ]

Dangl, Oskar. "Habakkuk in Recent Research," Currents in Research: Biblical Studies 9 (2001): 131-68. [ Links ]

Davies, Graham I. "The Destiny of the Nations in the Book of Isaiah." Pages 93-120 in The Book of Isaiah/Le Livre D'Isaïe: Les Oracles et Leurs Relectures Unité et Complexité de L'Ouvrage. Edited by J. Vermeylen. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 81; Leuven: Peeters, 1989. [ Links ]

Davies, Philip R. "'Pen of Iron, Point of Diamond' (Jer 17:1): Prophecy as Writing." Pages 65-81 in Writings and Speech in Israelite and Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy. Edited by E. Ben Zvi and M. H. Floyd; Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 10; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000), 65-81. [ Links ]

De Jong, Matthijs J. "Biblical Prophecy-A Scribal Enterprise. The Old Testament Prophecy of Unconditional Judgement considered as a Literary Phenomenon." Vetus Testamentum 61 (2011): 39-70. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853311X551493 [ Links ]

Dietrich, Walter. "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler." Pages 197-215 in Nachdenken über Israel, Bibel und Theologie: Festschrift für Klaus-Dietrich Schunck zu seinem 65. Geburtstag. Edited by H. M. Niemann, M. Augustin and W. H. Schmidt. Beiträge zur Erforschung des Alten Testaments und des Antiken Judentums 37. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1994. [ Links ]

_Nahum Habakkuk Zepheniah. International Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament. Translated by P. Altmann. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2016. [ Links ]

Fabry, H.-J. "פלל pll." Pages 567-78 in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament 11. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Floyd, Michael H. "Prophetic Complaints About the Fulfilment of Oracles in Habakkuk 1:2-17 and Jeremiah 15:10-18." Journal of Biblical Literature 110 (1991): 397418. https://doi.org/10.2307/3267779 [ Links ]

_ "Prophecy and Writing in Habakkuk 2,1-5." Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 105 (1993): 462-81. [ Links ]

_"'Write the revelation!' (Hab 2:2): Re-imagining the Cultural History of Prophecy," in Writings and Speech in Israelite and Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy (ed. E. Ben Zvi and M. H. Floyd; SBLSS 10; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000), 103-43. [ Links ]

_ "The מַשָּׂא (MASSÄ') as Type of Prophetic Book." Journal of Biblical Literature 121 (2002): 401-22. [ Links ]

Geyer, John B. Mythology and Lament: Studies in the Oracles about the Nations. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. [ Links ]

Gowan, Donald E. "Habakkuk and Wisdom." Perspective 9 (1968): 157-66. [ Links ]

Hamp, V. חִידָּׂה chidäh." Pages 320-3 in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament 4. [ Links ]

Isbell, Charles D. "The Limmûddîm in the Book of Isaiah." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 34 (2009): 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089209348153 [ Links ]

Janzen, J. Gerald. "Eschatological Symbol and Existence in Habakkuk." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 44 (1982): 394-414. [ Links ]

_"Habakkuk 2:2-4 in the Light of Recent Philological Advances." Harvard Theological Review 73 (1980): 53-78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017816000002030 [ Links ]

Jenkins, Allan K. "The Development of the Isaiah Tradition in Is 13-23." Pages 237-51 in The Book of Isaiah/Le Livre D'Isaïe: Les Oracles et Leurs Relectures Unité et Complexité de L'Ouvrage. Edited by J. Vermeylen. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 81; Leuven: Peeters, 1989. [ Links ]

Jöcken, Peter. Das Buch Habakkuk: Darstellung der Geschichte seiner kritischen Erforschung mit einer eigenen Beurteilung. Bonner Biblische Beiträge 48. Köln/Bonn: Peter Hanstein, 1977. [ Links ]

Kim, Hyun Chul Paul. "Isaiah 22: A Crux or a Clue in Isaiah 13-23." Pages 3-18 in Concerning the Nations: Essays on the Oracles against the Nations in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Edited by E. K. Holt, H.C. P. Kim and A. Mein. Library of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 612. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. [ Links ]

Lester, G Brooke. "Inner-Biblical Allusion." Theological Librarianship 2 (2009): 8993. https://doi.org/10.31046/tl.v2i2.110 [ Links ]

Mathews, Jeanette Performing Habakkuk: Faithful Re-enactment in the Midst of Crisis. Eugene: Pickwick, 2012. [ Links ]

Meek, Russell L. "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology." Biblica 95 (2014): 280-91. [ Links ]

Miller, Geoffrey D. "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research." Currents in Biblical Research 9 (2011): 283-309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476993X09359455 [ Links ]

Müller, H.-P. "N&a massä ." Pages 20-4 in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament 9. [ Links ]

Nissinen, Martti. "How Prophecy Became Literature." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 19 (2005): 153-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/09018320500472595 [ Links ]

_"Since When Do Prophets Write?" Pages 585-606 in In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes: Studies in the Biblical Text in Honour of Anneli Aejmelaeus. Edited by K. de Troyer, T.M. Law and M. Liljeström. Contributions to Biblical Exegesis & Theology 72; Leuven: Peeters, 2014. [ Links ]

Pinker, Aron. "Habakkuk 2.4: An Ethical Paradigm or a Political Observation?" Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 32 (2007): 91-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089207083767 [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T.M. "Habakkuk 1 - a Dialogue? Ancient Unit Delimiters in Dialogue with Modern Critical Interpretation," Old Testament Essays 17 (2004): 621-45. [ Links ]

_"From Watchtower to Holy Temple: Reading the Book of Habakkuk as a Spatial Journey." Pages 132-54 in Constructions of Space IV: Further Developments in Examining Ancient Israel's Social Space. Edited by M.K. George. Library of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 569. London/New York: Bloomsbury, 2013. [ Links ]

_ "Reading Habakkuk 3 in the Light of Ancient Unit Delimiters," HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 69(1) (2013), Art. #1975, 11 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v69i1.1975. [ Links ]

Roberts, J.J.M. First Isaiah. Hermeneia. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2015. [ Links ]

Schaper, Joachim. "Exilic and Post-exilic Prophecy and the Orality/Literacy Problem." Vetus Testamentum 55 (2005): 324-42. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568533054359850 [ Links ]

Seitz, Christopher R. Isaiah 1-39. Interpretation Bible Commentary. Louisville, Westminster John Knox, 1993. [ Links ]

Stähli, H.-P. "פלל pll http. Beten." Pages 427-32 in Theologischer Handkommentar zum Alten Testament 2. [ Links ]

Stolz, F. "נשׂא ns aufheben, tragen." Pages 110-7 in Theologischer Handkommentar zum Alten Testament 2. [ Links ]

Sweeney, Marvin A. "Foreword: The Oracles Concerning the Nations in the Prophetic Literature." Pages xvii-xx in Concerning the Nations: Essays on the Oracles against the Nations in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Edited by E. K. Holt, H.C. P. Kim and A. Mein. Library of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 612. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. [ Links ]

_"Habakkuk, Book of." Pages 1-6 in Anchor Bible Dictionary 3. [ Links ]

_"Structure, Genre, and Intent in the Book of Habakkuk." Vetus Testamentum 41 (1991): 63-83. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853391X00171 [ Links ]

_Isaiah 1-39. Forms of Old Testament Literature 16. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996. [ Links ]

_Isaiah 1-4 and the Post-Exilic Understanding of the Isaianic Tradition. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 171. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1988. [ Links ]

_The Twelve Prophets, Volume 2. Berit Olam. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Thompson, Michael E.W. "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany in the Book of Habakkuk" Tyndale Bulletin 44 (1993): 33-53. [ Links ]

Tooman, William. Gog of Magog: Reuse of Scripture and Compositional Technique in Ezekiel 38-39. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 52. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1628/978-3-16-151752-5 [ Links ]

Tull, Patricia K. Isaiah 1-39. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary. Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2010. [ Links ]

_"Intertextuality and the Hebrew Scriptures." Currents in Research: Biblical Studies 8 (2000): 59-90. [ Links ]

Van Ruiten, Jacques T.A.G.M. "'His Master's Voice'? The Supposed Influence of the Book of Isaiah in the Book of Habakkuk," Pages 397-411 in Studies in the Book of Isaiah. Edited by J. van Ruiten and M. Vervenne. Leuven: Peeters, 1997. [ Links ]

Wakefield, Andrew H. "When Scripture Meets Scripture." Review and Expositor 106 (2009): 549-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463730910600404 [ Links ]

Watts, John D.W. Isaiah 1-33. Word Biblical Commentary. Revised Edition. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2005. [ Links ]

Weis, Richard D. "Oracle." Pages 28-9 in Anchor Bible Dictionary 5. [ Links ]

Wendland, Ernst. "'The Righteous Live by their Faith' in a Holy God: Complementary Compositional Forces and Habakkuk's Dialogue with the Lord." Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 42 (1999): 591-628. [ Links ]

Wildberger, Hans. Jesaja 2. Teilband: Jesaja 13-27. (Biblischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament 10/2. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978. [ Links ]

Submitted: 01/10/2018

Peer-reviewed: 04/10/2018

Accepted: 02/12/2018

Prof. Gert TM Prinsloo, Department of Ancient Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria, Email: gert.prinsloo@up.ac.za.

1 I met Willie Wessels close to forty years ago when we were both young academics working on our doctoral theses in the prophetic corpus. It proved to be an interest that would occupy us for our entire academic careers. It is an honour to dedicate this study to Willie on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday.

2 Marvin A. Sweeney, "Structure, Genre, and Intent in the Book of Habakkuk," VT 41 (1991): 63-83 (64).

3 For משא cf. the discussion in Section C1. For תפלה, cf. Pss 17:1; 86:1; 90:1; 102:1; 142:1.

4 Michael H. Floyd, "The מַשָּׂא (MASSÄ') as Type of Prophetic Book," JBL 121 (2002): 401-22.

5 The present study is concerned with the first literary unit. In a previous study I observed that Hab 3:1-19 alludes to hymnic passages (Ex 15:1-18; Dt 33:1-3; Jdg 5:45; Pss 18:8-16; 68:8-9; 77:17-20; 144:5-6) and I suggested that 3:3-6 and 3:8-13, 15 might contain archaic hymnic passages incorporated by the poet in 3:2, 7, 14, 16-19 in a new composition. The reference to עני the poor' (3:14) indicated to me that the poet of Habakkuk 3 belongs to a specific social group in the late Persian and/or early Hellenistic period who regarded themselves as the true Israel and as the actual recipients of Yhwh's salvific intervention in and promises to his people. The poet appropriates Yhwh's promise to the prophet Habakkuk at the time of the Chaldean onslaught on and devastation of Jerusalem to his own predicament as a marginalised 'poor' in a wicked and hostile environment; cf. Gert T.M. Prinsloo, "Reading Habakkuk 3 in the Light of Ancient Unit Delimiters," HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 69(1) (2013), Art. #1975, 11 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v69i1.1975.

6 Richard D. Weis, "Oracle," ABD 5, 28-9 (28) defines a משא as a "prophetic exposition of divine revelation" responding to "a question about a lack of clarity in the relation between divine intention and human reality." Floyd, "מַשָּׂא (MASSÄ)" 409-10 translates the term as "prophetic reinterpretation of a previous revelation." Cf. H.-P. Müller, "מַשָּׂא massä," TDOT 9, 20-4; F. Stolz, "מַשָּׂא nśʾ" aufheben, tragen," THAT II, 110-7.

7 D.A. Brueggeman, "Psalms 4: Titles," in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings (ed. Tremper Longman III and Peter Enns, Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008), 613-21 (619) indicates that psalms containing תפלה in their superscripts "are all petition psalms." Cf. H.-J. Fabry, "פלל" TDOT 11, 567-78; H.-P. Stähli, "פללpll hitp. beten," THAT II, 427-32.

8 כשדים occurs 87 times in the Hebrew Bible. In Genesis (11:28, 31; 15:7) it qualifies the city Ur, ("Ur of the Chaldeans"). In Job (1:1) it refers to bands of marauders and in Daniel (2:2, 4, 5, 10; 4:4; 5:7, 11) to Babylonian sages. Elsewhere the term refers to the Neo-Babylonian Empire founded by Nabopolasser in 625 bce. In 612 bce the Babylonians conquered Nineveh and destroyed the power of the Assyrian Empire. In 605 bce they defeated an Egyptian army at Charchemish and since then directly influenced events in Judah. Upon Nabopolasser's death in 605 bce his son, Nebuchadrezzar became king and during his reign (605-556 bce) the empire reached the zenith of its power. Nebuchadrezzar invaded Judah in 598/7, 587/6 and 582 bce and deported large numbers of Judeans to Babylonia. The invasion of 587/6 also led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, causing an existential crisis in Judean society and shattering the traditional belief in the inviolability of the temple and the enduring nature of the Davidic royal dynasty (cf. Jer 7:1-29). Cf. Marvin A. Sweeney, The Twelve Prophets, Volume 2 (Berit Olam; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2000), 454-6; John D.W. Watts, Isaiah 1-33 (WBC; Revised Edition; Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2005), 241-2 for brief historical surveys of these eventful times.

9 Cf. הצדיקאת כי רשע מכתיר "indeed, wickedness surrounds the righteous" (1:4); תחריש בבלע רשע צדיק ממנו "(why) are you silent when a wicked person devours someone more righteous than himself?" (1:13); מחצת ראש מבית יהוה "you smashed the head/leader from the wicked's house" (3:13).

10 Jeanette Mathews, Performing Habakkuk: Faithful Re-enactment in the Midst of Crisis (Eugene: Pickwick, 2012), 207 translates 1:4c with "For wickedness surrounds the righteous one." She contends that the "inclusion of both object marker and definite article in conjunction with הצדיק in v. 4 suggests that the righteous one is a specific group or a specific individual... (I)n its original context... הצדיק may well have been a reference to the prophet himself as a representative of the innocent righteous. Taking cognizance of the contrast between the use of the definite article for צדיק and the lack of article for רשע, this translation removes the need for precise identification of רשע by translating צדיק as the righteous one and רשע with the generic term wickedness in both Hab 1:4 and 1:13" (Mathews, Performing Habakkuk, 208-9).

11 Countless emendations of this phrase have been proposed; cf. Francis I. Andersen, Habakkuk (AB; New York: Doubleday, 2001), 208-16; Aron Pinker, "Habakkuk 2.4: An Ethical Paradigm or a Political Observation?" JSOT 32 (2007): 91-112. In the present context, I cannot discuss the difficult verse in detail. Below I will argue that the general gist of the verse is clear. It promises the destruction of Babylonian arrogance, but life for the righteous clinging to the trustworthiness of Yhwh's revelation (2:2-3).

12 According to Marvin A. Sweeney, "Habakkuk, Book of," ABD 3, 1-6 "the identity of the oppressor presupposed by the woe-oracles of 2:5-20" is a "major problem" in the book.

13 Cf. Peter Jöcken, Das Buch Habakkuk: Darstellung der Geschichte seiner kritischen Erforschung mit einer eigenen Beurteilung (BBB 48; Köln/Bonn: Peter Hanstein, 1977) for the book's research history up to the late 1970's. Jöcken's work illustrates the close relationship between questions regarding the book's date and the identification of the wicked (1:4, 13; 3:13) and the righteous (1:4, 13; 2:4). According to Oskar Dangl, "Habakkuk in Recent Research," CR:BS 9 (2001): 131-68 research now focuses on more than this single issue, yet a substantial part of his overview of Habakkuk research is dedicated to questions regarding the identity of the actors and the historical foundation of the book (pp. 139-44).

14 Sweeney, Twelve Prophets, 455. Such a reading enhances the prominent theodicy theme in the book, a "debate that would have taken place in Judean society beginning in 605 B.C.E. when Judah became a vassal of Babylon."

15 Space does not allow for a discussion of individual points of view; cf. Walter Dietrich, Nahum Habakkuk Zepheniah (IECOT; trans. P. Altmann; Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2016), 91-103 for a review of scholarly opinions. Whether from a synchronic or diachronic perspective, the book is usually regarded as a dialogue between prophet and Yhwh. A careful reading of the book does not, however, substantiate this claim; cf. Michael H. Floyd, "Prophetic Complaints About the Fulfillment of Oracles in Habakkuk 1:2-17 and Jeremiah 15:10-18," JBL 110 (1991): 397-418; David Cleaver-Bartholomew, "An Alternative Approach to Hab 1,2-2,20," SJOT17 (2003): 206-25; Gert T. M. Prinsloo, "Habakkuk 1 - a Dialogue? Ancient Unit Delimiters in Dialogue with Modern Critical Interpretation," OTE 17 (2004): 621-45.

16 Gert T.M. Prinsloo, "From Watchtower to Holy Temple: Reading the Book of Habakkuk as a Spatial Journey," in Constructions of Space IV: Further Developments in Examining Ancient Israel's Social Space (ed. M.K. George; LHBOTS 569; London/New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 132-54 (152-3).

17 Contra Charles D. Isbell, "The Limmûddîm in the Book of Isaiah," JSOT 34 (2009): 99-109 I do not propose the existence of a hypothetical "school" of Isaiah-disciples faithfully transmitting their master's initial oral messages and eventually committing them to writing. I concur with Michael H. Floyd, "Prophecy and Writing in Habakkuk 2,1-5," ZAW 105 (1993): 462-81 that "the phenomenon of prophecy cut across various sectors of Israelite society to intersect with the institution of scribal academies well before the time of the exile" (p. 480); cf. ibid., "'Write the revelation!' (Hab 2:2): Re-imagining the Cultural History of Prophecy," in Writings and Speech in Israelite and Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy (ed. E. Ben Zvi and M. H. Floyd; SBLSS 10; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000), 103-43; Joachim Schaper, "Exilic and Post-exilic Prophecy and the Orality/Literacy Problem," VT 55 (2005): 324-42. I depart form the presupposition that prophecy is both an oral and literary phenomenon; cf. Philip R. Davies, "'Pen of Iron, Point of Diamond' (Jer 17:1): Prophecy as Writing," in Ben Zvi and Floyd, Writings and Speech, 65-81. The composition of prophetic scrolls points to the "production of the idea of 'prophecy ' as an institution of divine guidance of national history" (Davies, "Pen of Iron," 77, italics original). That prophecy could express itself in written form "simply indicate[s] the adaptation of this divinatory phenomenon to a succession of different socio-cultural situations" (Floyd, "Prophecy and Writing," 481). Matthijs J. de Jong, "Biblical Prophecy-A Scribal Enterprise. The Old Testament Prophecy of Unconditional Judgement Considered as a Literary Phenomenon," VT 61 (2011): 39-70 argues that "the literary core of the biblical prophetic books does not present the message of a historical prophet but a scribal reinterpretation of a prophetic legacy." It was "the scribal reception, revision, and elaboration of this legacy that gave rise to 'biblical prophecy' and prompted the development of the prophetic books" (p. 65). Cf. also Martti Nissinen, "How Prophecy Became Literature," SJOT 19 (2005): 153-72; ibid., "Since When Do Prophets Write?" in In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes: Studies in the Biblical Text in Honour of Anneli Aejmelaeus (ed. K. de Troyer, T.M. Law and M. Liljeström; CBET 72; Leuven: Peeters, 2014), 585-606.

18 Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), 464 argues that "tenuous or dangerous political situations encouraged the obscuring of revolutionary oracular contents." He identifies two examples of "inner-biblical cryptographic techniques" in Jeremiah. Using the atbash technique well known from later Jewish sources, he identifies "the meaningless ששך in Jer. 25:26 and 51:41" as a cryptogram for בבל. Similarly, the equally mysterious לב קמי "the heart of those rising against me" in Jer 51:1 yields כשדים "Chaldeans," as the Targum correctly understood it. I propose similar circumstances for the book of Habakkuk. It is significant that the five taunt songs in Hab 2:6-20 are designated משל "a taunt song" and מליצה הידות "an allusive expression (containing) riddles." According to V. Hamp "חִידָּׂה chîdâh," in TDOT 4, 320-3 "in Hab 2:6, the context suggests that mäshäl has the meaning "taunt song," and melîtsê chîdhôth are "riddling taunts" (p. 322). The nouns משל,מליצה and חידה occur together in Prov 1:9 (Mathews, Habakkuk, 132). The 'הוי-exclamations are intentionally opaque regarding the identity of the perpetrator, but unequivocal regarding his ultimate destiny.

19 Andrew H. Wakefield, "When Scripture Meets Scripture," Review and Expositor 106 (2009): 549-74 (550).

20 Cf. Patricia Tull, "Intertextuality and the Hebrew Scriptures," CR:BS 8 (2000): 5990; Geoffrey D. Miller, "Intertextuality in Old Testament Research," CBR 9 (2011): 283-309 for critical discussions of the application of intertextuality in Old Testament research.

21 David Carr, "The Many Uses of Intertextuality in Biblical Studies: Actual and Potential," in Congress Volume Helsinki 2010 (ed. M. Nissinen; VTSup 148; Leiden: Brill, 2012), 505-35, argues that "insofar as biblical scholars aim and claim to be reconstructing specific relationships between a given biblical text and earlier texts, the proper term for this type of inquiry is reconstruction of 'influence,' not 'intertextuality'" (p. 522). Russell L. Meek, "Intertextuality, Inner-Biblical Exegesis, and Inner-Biblical Allusion: The Ethics of a Methodology," Bib 95 (2014): 280-91 indicates that "intertextuality" is used as "label for all investigations into literary relationships between various texts" (p. 280). He pleads for a more nuanced use of terminology and argues that the term "intertextuality" should be avoided "when attempting to demonstrate - or presupposing - an intentional, historical relationship between texts" (p. 291).

22 Cf. Tull, "Intertextuality," 59-66; Miller, "Intertextuality," 294-98. For discussions and applications of such criteria, cf. David Carr, "Method in Determination of Direction of Dependence: An Empirical Test of Criteria Applied to Exodus 34,11-26 and its Parallels," in Gottes Volk am Sinai: Untersuchungen zu Ex 32-34 und Dtn 9-10 (ed. M. Köckert and E. Blum; VWGTh 18; Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2001), 10740; William Tooman, Gog of Magog: Reuse of Scripture and Compositional Technique inEzekiel 38-39 (FAT 52; Tübingen: MohrSiebeck, 2011), 4-35.

23 Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation, 458-99 refers to the re-interpretation of prophetic oracles under new social and historical circumstances as mantological exegesis. Older prophetic oracles "were preserved by faithful disciples and students of the great prophets (cf. Isa. 8:1-2, 16-18)" or "amanuenses like Baruch ben Neriah copied versions of older oracles for posterity (cf. Jer. 36:32)" (p. 458).

24 G. Brooke Lester, "Inner-Biblical Allusion," Theological Librarianship 2 (2009): 89-93 (89).

25 For an overview of the debate regarding this question, cf. Dangl, "Habakkuk in Recent Research," 154-7.

26 Ernst Wendland, "'The Righteous Live by their Faith' in a Holy God: Complementary Compositional Forces and Habakkuk's Dialogue with the Lord" JETS 42 (1999): 591-628 lists intertextual links between the book of Habakkuk and other books of the Hebrew Bible (cf. Figures 11 and 12 on pp. 623-5). There are 29 intertextual links between Isaiah and the 36 verses of Habakkuk 1:1-2:20 (i.e. for 81% of the verses in Habakkuk's משא), but only four intertextual links between Isaiah and the 19 verses in Hab 3:1-19 (i.e. for only 21% of the verses in Habakkuk's תפלה). It suggests that Habakkuk 1-2 is closely associated with the Isaiah tradition circle, while Habakkuk 3 is more interested in traditions presented in so-called "theophany" texts (cf. Ex 15; Deut 33; Judg 5; Pss 18; 68).

27 J. Gerald Janzen, "Habakkuk 2:2-4 in the Light of Recent Philological Advances," HTR 73 (1980): 53-78.

28 Janzen, "Habakkuk 2:2-4," 54-62 argues that the shared vocabulary (עד/עוד ,אמן,כזבעוד/) in Hab 2:2-4 and Prov 6:19; 14:5, 25; 19:5, 9; 12:17 suggests that Hab 2:2-4 is concerned with the reliability of Yhwh's revelation (Hab 1:1) that Habakkuk must write down (Hab 2:2-4).

29 Janzen, "Habakkuk 2:2-4," 68-78.

30 Janzen, "Habakkuk 2:2-4," 68.

31 Janzen, "Habakkuk 2:2-4," 75. Janzen argues that Habakkuk's use of Isaiah traditions is analogous to Jeremiah's use of Hosea traditions. In order to speak a new word of Yhwh in a changed situation, prophets "drew upon the resources of the prophetic tradition and reused that tradition" (Janzen, "Habakkuk 2:2-4," 76). Cf. J. Gerald Janzen, "Eschatological Symbol and Existence in Habakkuk," CBQ 44 (1982): 394-414 for an interpretation of the entire book in the light of these observations.

32 Michael E. W. Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany in the Book of Habakkuk," TynBul 44 (1993): 33-53.

33 Robert P. Carroll, "Habakkuk," in A Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation (ed. R. J. Coggins and J. L. Houlden; London: SCM, 1990), 268-9 (269).

34 Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany," 44.

35 Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany," 45.

36 Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany," 45-6. תוכחת occurs 19 times in wisdom contexts and four times in other literature; מדון occurs 15 times in Proverbs and only twice elsewhere (Ps 80:6; Jer 15:10); עמל occurs 33 times in wisdom writings and 18 times elsewhere; the רשע-צדיק antithesis occurs 78 times in wisdom literature and only 25 times elsewhere. Cf. also Donald E. Gowan, "Habakkuk and Wisdom," Perspective 9 (1968): 157-66.

37 Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany," 49-50.

38 Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany," 50.

39 Walter Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler," in Nachdenken über Israel, Bibel und Theologie: Festschrift für Klaus-Dietrich Schunck zu seinem 65. Geburtstag (ed. H. M. Niemann, M. Augustin and W. H. Schmidt; BEATAJ 37; Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1994), 197-215.

40 Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler," 198-200.

41 Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler," 201-205.

42 Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler," 205-208.

43 According to Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler," 213 n58 היין in Hab 2:5 is a scribal error for הוי. The close relationship between Hab 2:5 and Isa 5:11-19 prompts Dietrich to emend the text of Habakkuk.

44 The expression occurs sixty times in Isaiah.

45 Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler" 198.

46 Dietrich, '"Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler" 200.

47 Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler" 200.

48 Dietrich, "Habakuk - ein Jesajaschüler," 203.

49 Jacques T.A.G.M. van Ruiten, "'His Master's Voice'? The Supposed Influence of the Book of Isaiah in the Book of Habakkuk," in Studies in the Book of Isaiah (ed. J. van Ruiten and M. Vervenne; Leuven: Peeters, 1997), 397-411.

50 Van Ruiten, "'His Master's Voice'?" 411.

51 Van Ruiten, "'His Master's Voice'?" 411. Van Ruiten fails to recognise the complexity of the relationship between Isaiah and Habakkuk. Creative Fortschreibungen of prophetic oracles in post-exilic redactional circles are multi-layered and multi-directional. I will argue below that Isaiah is not the "master" and Habakkuk is speaking "in his voice." To the contrary, Habakkuk's sets the tone for the Isaian משאות against Babylon.

52 Cf. Christopher R. Seitz, Isaiah 1-39 (IBC; Louisville, Westminster John Knox, 1993) for an exception to this statement. Seitz discusses the importance of the similar superscripts in Hab 1:1 and Isa 13:1 (p. 132), the eschatological character of both messages (Hab 2:3; Isa 13:22, cf. pp. 133-4), the fact that both contain a taunt song against Babylon (Hab 2:6; Isa 14:4; cf. p. 134), and in both the prophet plays the role of a watchman (Hab 2:1; Isa 21:8; cf. pp. 165-7).

53 The expression מדבר־ים "desert of the sea" in Isa 21:1a has been the object of countless emendations; cf. Hans Wildberger, Jesaja 2. Teilband: Jesaja 13-27 (BKAT X/2; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978), 763-4. מדבר occurs again in the actual prophetic utterance (21:1b). According to Marvin A. Sweeney, Isaiah 1-39 (FOTL 16; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 280, in Akkadian sources the expression mat tamti "Land of the Sea" designates the swampy area in the south of Babylonia ruled by the Babylonian Merodach-baladan when he fled Babylon after Sargon II conquered the city in 710 bce. Merodach-baladan is identified as a member of the bal kur tam "dynasty of the Sealand." The Akkadian kur designates a border area and corresponds to Hebrew -מדבר. Brevard S. Childs, Isaiah (OTL; Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 152 regards מדבר־ים as "an appropriate Hebrew designation for the border areas ruled by Merodach-baladan." Childs, Isaiah, 150-51, identifies two redactional layers in Isa 21:1-10. The first dates from the eighth century when Assyria attacked Judah's ally, Merodach-baladan. Isaiah foresees Babylon's defeat. In the sixth century Isaiah's message is reapplied to the imminent destruction of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (Isa 21:9). According to Ulrich F. Berges, The Book of Isaiah: Its Composition and Final Form (trans. M. C. Lind; Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2012), 138 n78, the Akkadian mat tamti is not rendered by D' f-N "because the key word -מדבר from the oracle (v. 1b) should not be lacking in the title; cf. חזיון in 22.1, 5."

54 Sweeney, Twelve Prophets, 460.

55 Isaiah 13:1 (משא בבלI); 14:28 (בשנת־מות המלך אחז היה המשא הזהI); 15:1 (משא מואבI); 17:1 (משא דמשקI); 19:1(משא מצריםI); 21:1 (משא מדבר־יםI), 11 (משא דומהI), 13 (משא בערבI); 22:1 (משא גיא חזוןI); 23:1 (משא צרI).

56 Cf. Isa 30:6 (משא בהמות נגבI); Nah 1:1 ((משא נינוהI); Hab 1:1 (המשא אשר חזה חבקוקהנביא); Mal 1:1 (משא דבר־יהוה אל־ישראל); Zech 9:1 (משא דבר יהוה בארץ חרדך ודמשק מנחתו); 12:1 (משא דבר־יהוה על־ישראI).

57 Weis, "Oracle," 28.

58 Floyd, מַשָּׂא (MASSä')" 413-15.

59 Childs, Isaiah, 114.

60 Sweeney, "Structure, Genre, and Intent," 65-6.

61 Thompson, "Prayer, Oracle and Theophany," 34.

62 Graham I. Davies, "The Destiny of the Nations in the Book of Isaiah," in The Book of Isaiah/Le Livre D'Isaïe: Les Oracles et Leurs Relectures Unité et Complexité de L'Ouvrage (ed. J. Vermeylen; BETL 81; Leuven: Peeters, 1989), 93-120 (115).

63 Willem A.M. Beuken, "Common and Different Phrases for Babylon's Fall and Its Aftermath in Isaiah 13-14 and Jeremiah 50-51," in Concerning the Nations: Essays on the Oracles against the Nations in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel (ed. Else K. Holt, Hyun Chul Paul Kim and Andrew Mein; LHBOTS 612; London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015), 53-73.