Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.31 no.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2018/v31n1a11

ARTICLES

A comprehensive reading of Psalm 137

Daniel Simango

North-West University

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to carry out a thorough exegetical study of Ps 137 in order to grasp its content, context and theological implications. The basic hypothesis of this study is that Ps 137 can be best understood when the text is thoroughly analysed. Therefore, in this article, Ps 137 will be read in its total context (i.e. historical setting, life-setting and canonical setting) and its literary genre. The article concludes by discussing the imprecatory implications and message of Ps 137 to the followers of YHWH.

Keywords: Psalm 137; Exegetical Study; Imprecatory Psalms; Imprecation.

A INTRODUCTION

Psalm 137 is one of the best known imprecatory psalms that focus on the traumatic experience of exile in Babylon. The psalm reveals the sufferings and sentiments of the people who probably experienced at first hand the grievous days of the conquest and destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE and who shared the burden of the Babylonian captivity after their return to their homeland. At the sight of the ruined city and the temple, the psalmist vents with passionate intensity his deep love for Zion as he recalls the distress of alienation from their sanctuary. Therefore, this psalm touches the raw nerve of Israel's faith.

The poem commences with the melancholy recollection of the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem which caused the Israelite captives to mourn and stop playing their musical instruments. The Babylonian masters asked the captives to join them in the mockery of YHWH. The Israelite captives refused to participate in the mockery of YHWH and the psalmist pledges his complete devotion to Jerusalem and therefore, towards YHWH. Finally, the psalmist prays for the wrath of God to be unleashed against the enemies of Judah, the Edomites and Babylonians, who were responsible for the destruction of Jerusalem and their misery in Babylon.

For analysing OT poetry, a three-dimensional reading strategy, suggested by some South African scholars,1 namely the intra-textual, extra-textual and inter-textual reading of a poetic text2 will be applied to the study of Ps 137.

Intra-textual relations refer to the relations that exist at different levels in a given text. In the intra-textual analysis, poetic, stylistic, semantic and rhetorical features will be discussed. When discussing the semantic relations between parallel lines the categories/terms of Ernst Wendland3 will be used in this present study, supplemented by categories indicated by John Beekman and John Callow4 and further developed by Peter Cotterell and Max Turner.5 The interpretation of key phrases, words or concepts will be explained, keeping in mind the guidelines set by Moises Silva.6

Extra-textual relations refer to the biographical particulars of the author and his world. This helps the reader to understand how the content functions in its context. In the extra-textual analysis, the literary genre, historical setting, life-setting and canonical context of Ps 137 will be discussed.

Inter-textual relations refer to the relations between a specific text and other texts.7 This helps the reader to understand the way in which the content of inter-related texts affects the theological implications of Ps 137.

Therefore, the three-dimensional reading strategy is an effective method for gaining a more valid understanding of the content, context and theological implications of Ps 137.

In this article, the Hebrew text and the author's own translation of Ps 137 will be given. The basic literary structure of the psalm will be given. For practical purposes, Ps 137 will be sub-divided into cola, strophes and stanzas.

B TEXT AND TRANSLATION

C THE STRUCTURE OF PSALM 137

When looking at the structure of Ps 137, one of the most striking features is the multiple incidences of the first person plural as agent/subject in vv. 1-4.9 In vv. 5-6, there is a transition to the first person singular forms, then in v. 7a the subject changes to YHWH, who is addressed for the first time in the imperative זְכֹר יְהוָה("Remember, YHWH..."). The reference to the Edomites introduces a new element to the content of the psalm.10 In vv. 8-9, Babylon is addressed, but an unknown agent is evoked (i.e. "the one who repays..."). Although the overt subject is this unknown agent, on a covert level YHWH is still the agent, since he is the one to whom the last petition was explicitly directed (7a) and he is probably regarded as the eventual avenger of evil.

Ernst Wendland11 and Mary Des Camp12 observe that vv. 1-4 focus on the past, vv. 5-6 on the present and vv. 7-9 on the future.

On the basis of alternation of agent/subject and time orientation, Ps 137 may be subdivided into three stanzas: vv. 1-4, 5-6, and 7-9. This three-fold subdivision of the psalm is underwritten by the majority of scholars.13

The three stanzas of Ps 137 may be sub-divided into the following strophes:14

Stanza I (1-4): Setting and complaint

Strophe A (1-2) Description of trouble

Strophe B (3) Taunt of enemies

Strophe C (4) Plaintive answer

Stanza II (5-6): Total commitment and devotion to Jerusalem

Strophe D (5-6) Total commitment and devotion to Jerusalem

Stanza III (7-8): Imprecations against Edom and Babylon

Strophe E (7) Implicit curse against Edom

Strophe F (8-9) Implicit curse against Babylon

The above structure of Ps 137 is discussed in detail in the subsequent analysis.

D INTRA-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF PSALM 137

1 Stanza I (vv. 1-4): Setting and complaint

Stanza I gives the setting of the Israelite captives and their distress. This stanza consists of three strophes: A (vv. 1-2), B (v. 3) and C (v. 4). Strophe A describes the setting of the Israelite captives and their lament over the destruction of Zion. Strophe B focuses on how the Babylonian masters tried to force the Israelite captives to join them in mocking YHWH. Strophe C is the captives' answer to the Babylonian captors' request to mock YHWH.

1a Strophe A (vv. 1-2)

Strophe A consists of a bicolon (v. 1) and a single colon (v. 2).

In v. 1, the psalmist and his companions were in exile in Babylon - by the irrigation canals.15 They remembered the destruction Zion and that sad memory caused them to mourn. צִיּוֹן ("Zion") probably refers to Jerusalem and the temple.16 Zion was understood by Israel as the symbol of God's presence in their midst.

In v. 2, the psalmist and his fellow musicians set aside their instruments and did not play them again because of their sad memory of the destruction of Jerusalem. As far as coherence or semantic relations are concerned, v. 2 is a vivid and metaphorical restatement of v. 1. The poplars correspond to the rivers where they grew and the hanging up of the lyres corresponds to the passiveness (sit) and sadness of the psalmist and his companions. The figure of hanging the lyre on the trees is metaphorical and means that the owners set aside their instruments and did not play them again.17 It also shows that the musicians had given up praise publicly.18 The psalmist and his fellow musicians are probably used synecdochically for the entire Judean exile community, who were deprived of the joyous YHWH worship in the temple.

There is also an extended parallelism with the pattern (a b c a'b') in vv. 1-2.

The purpose of the extended parallelism is to emphasize the point that the psalmist and his companions' memory of the destruction of the temple (or Zion) is the crescendo of vv. 1-2. There is pivotal parallelism in vv. 1-2 because the phrase when we remembered Zion is pivotal to the understanding of the psalmist and his companions' actions in vv. 1 and 2. The musicians' memory of Zion affects their behaviour or actions; their sad memory makes them sit and mourn over the temple and to put away their instruments.

To sum up Strophe A, the psalmist, his fellow musicians and other Judeans were in exile in Babylon, besides the irrigation canals. There they recalled the destruction of the temple in Zion and they were deeply saddened and as a result, they sat down and mourned. The joy of the presence of YHWH in the temple now existed only as a memory in their hearts because Zion was in ruins. They hung their musical instruments on the trees and they did not play them again. The tone of this strophe is passiveness and sadness.

1b Strophe B (v. 3)

Strophe B consists of a single tricolon

In the tricolic verse (v. 3), the Babylonian masters asked the Israelite captives to sing the sacred songs used to worship YHWH in the temple. Their request was a mockery of Israel's worship at the temple, which was also an indirect attack on the character of YHWH, because the songs of Zion celebrated the majesty and protection of YHWH over his people.19 In effect, the Babylonians were trying to force the exiles to join them in the mockery of YHWH. The temple symbolised the presence of YHWH. Zion was central to the identity and survival of God's people.20 The Babylonians had destroyed the city of Zion, together with the temple. When they made their request, by implication the captors were asking the Israelite captives the mocking question "where is your God?"21 They wanted to convince the Israelite captives that YHWH had forgotten and abandoned them. They also implied that YHWH was weak, powerless and could not deliver his people in their time of trouble.22

As far as coherence or semantic relations are concerned in v. 3, there is synonymous parallelism, base-restatement, which follows a climatic pattern: (a) words of a song (b) mirth (c) a song of Zion. The song is further specified in 4a as a song of YHWH.

1c Strophe C (v. 4)

Strophe C consists of a single colon (v. 4)

In v. 4, the Israelite captives refused to participate in the mockery of YHWH. Singing a song of Zion in a foreign land would be an insult to YHWH. It was impossible for the Israelite captives to sing a song intended to praise YHWH for the amusement of their masters. The captives' words in v. 4 create the mood of desperate and seemingly hopeless lament and thus set up vv. 5-6 as a song of Zion which expresses confidence and hope for Israel.23

2 Stanza II (vv. 5-6): Total Commitment and Devotion to Jerusalem

In Stanza II, the psalmist expresses his deep commitment and devotion to Jerusalem and therefore, towards YHWH. This stanza consists of a single strophe: D (vv. 5-6).

2a Strophe D (vv. 5-6)

Strophe D consists of a bicolon (v. 5) and a tricolon (v. 6)

As far as coherence or semantic relations are concerned, there is a causal correlation, reason-result in 5ab - more specifically condition-outcome. 5b is the result or outcome or consequence of what would or should happen to the psalmist (apodosis) when he forgets Jerusalem (protasis). 5a is thus a conditional clause. If the protasis expresses what would happen, it is a real or hypothetical result, to be translated as "then will my right hand forget". If the protasis expresses what should happen, it is the desired result, as in the translation: "May my right hand forget." If the psalmist forgets Jerusalem then his right hand would forget its skill of playing the harp.

Verse 6 contains two negative conditional clauses: 6b and 6c, following the main clause (6a) which expresses the result or outcome of the double condition. It indicates the consequence of what would or should happen to the psalmist should he not remember (6a) or exalt (6b) Jerusalem.

As far as coherence or semantic relations are concerned, there is a synonymous parallelism, base-amplification in 5a, 6b and 6c. 6c is synonymous with 5a and 6b. Verse 6c further expands in detail what it means to forget Jerusalem in 5a and 6b.24

As far as coherence or semantic relations are concerned, there is also a synonymous parallelism, base-restatement in vv. 5b and 6a. In both cola, the psalmist calls a curse on himself, by asking God to paralyse him so that he would not be able to play his instrument or sing if he should forget Jerusalem.25

There is also a synonymous parallelism, base-restatement in 5a, 6b and 6c. 5a, 6b and 6c also display a climactic pattern. Forgetting Jerusalem in 5a and 6b is the same as not making Jerusalem the source of one's joy and happiness in 6c.

There is an extended parallelism with a chiastic pattern (a b b'a') in vv. 5-6.26 There are two conditional clauses (5a, 6b) of which, the two elements of protasis (if...) and apodosis (then…) occur in reverse order (5b, 6a):

The purpose of the extended parallelism is to highlight or emphasize the psalmist's self-imprecation and faithfulness towards Jerusalem. If he forgets Jerusalem (which is disloyalty to YHWH), he will be calling a curse on himself - he will lose the skill of playing musical instruments with his right hand and the ability to sing songs of Zion with his mouth. This implies that remembering Zion or Jerusalem leads to a renewed devotion to the Lord.27

Verses 5-6 show that love for Zion is not separate from love for God. For the exiled community of Israelites, love for God and Jerusalem was intertwined because of the temple. Loyalty to YHWH lay in remembering rather than in forgetting Jerusalem. The Israelite captives could not forget Jerusalem and everything it stood for: the covenant, the temple, the presence and the kingship of YHWH, atonement, forgiveness and reconciliation. The pious Israelite community vowed never to forget God's promises and to persevere and wait for YHWH's redemption.28

In a nutshell, the psalmist in Strophe D (vv. 5-6) refuses to sing as instructed by his captors because it would be a mockery of YHWH. However, it is impossible for the psalmist to forget Jerusalem because it is his greatest joy.29 He, therefore, pledges complete loyalty and devotion towards Jerusalem and therefore, towards YHWH. The psalmist shows his passionate love for Jerusalem, the central place of worship. His devotion takes the form of a solemn vow invoking upon himself the penalty of total or partial paralysis. Should he forget where his loyalty lies, namely Jerusalem, he would lose control of the most important organs of a musician - his hands and tongue30 - so that he would never be able to play his musical instrument or sing again. The psalmist's loyalty to Jerusalem is a measure of his loyalty to YHWH since the city symbolizes the divine presence.

3 Stanza III (vv. 7-9): Imprecations against Edom and Babylon

Stanza III is a series of imprecations on the nations that were hostile to Israel. Stanza III consists of two strophes: E (v. 7) and F (vv. 8-9). Strophe E is an imprecation against the nation of Edom. Strophe F is an imprecation against the nation of Babylon.

3a Strophe E (v. 7)

Strophe E consists of a single bicolon

In the bicolic verse (v. 7), YHWH in Strophe E (v. 7) is exhorted to think of the evil deeds committed against him by the Edomites. During the destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE, the nation of Edom trod behind the Babylonians like hyenas following a lion.31 Jerusalem had already been destroyed by Babylon and yet the Edomites continued with the destruction and they plundered the city.32 They also killed the fugitives. Therefore, the psalmist makes a petition to YHWH to punish the Edomites for their hostility towards Israel.

3b Strophe F (vv. 8-9)

Strophe F consists of a bicolon (v. 8) and a single colon (v. 9).

In v. 8, the psalmist prays for the destruction of Babylon. He wants Babylon to experience the same treatment that they gave Judah ("retribution principle"33). A blessing lies on anyone who is used in bringing down Babylon.

The mention of Babylon here in 8a (Stanza III) and in 1a (Stanza I) forms an inclusion. In v. 1, Babylon is portrayed as a conqueror, but in 8a the destruction of Babylon is envisaged. The inclusion rounds off the psalm34 and rhetorically it emphasizes a reversal of roles. The ruthless conqueror, Babylon, will now be destroyed.35 This is expressed by the participle passive "doomed to destruction."36 Therefore, YHWH's honour would only be upheld if Babylon was destroyed.37 The nation of Babylon fell to the Persians in 539 BCE.

In the last colon (v. 9), the vivid description of smashing infants against rocks is perhaps hyperbolic and should be understood as "a reference to the cruelty of ancient warfare generally".38 It was common for victorious armies to kill children - especially the male children - of their conquered enemies.39 Therefore v. 9 should be interpreted in light of this ANE context and mentality.40 The Babylonians were also well-known for their cruelties.41 Probably they actually killed off at least some of the children of Jerusalem. The psalmist thus prays that YHWH would unleash on Babylon the atrocities they themselves had committed in Judah and elsewhere.42 In this way, she would taste the bitterness of such utter defeat, helplessness and defencelessness that they would not be able to defend even their infants. Like in v. 8b, a blessing lies on anyone who destroys Babylon.

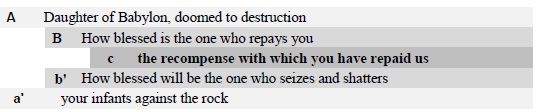

There is also an extended parallelism with a chiastic pattern (a b c b'a') in vv. 8-9.

The purpose of the extended parallelism is to highlight or emphasize the point that Babylon's atrocity against Judah is the very reason for her destruction. Babylon destroyed Jerusalem, the centre of the YHWH cult; therefore, YHWH's honour will only be upheld if Babylon is also destroyed.43 The destroyer of Babylon is blessed because he is YHWH's instrument of retribution.

As far as coherence or semantic relations are concerned in vv. 8-9, 8a is a generic imprecation, 8b states the retribution principle and 9 gives a specific example of an imprecation.

4 Summary of Intra-Textual Analysis

Psalm 137 begins with a portrayal of the psalmist and his companions, probably fellow musicians, when they were in exile in Babylon, beside the irrigation canals. When they recalled the destruction of the temple in Zion and they were filled with deep sadness, so they sat down and mourned. The joy of the presence of YHWH in the temple now existed only as a memory in their hearts because Zion was in ruins. They hung their musical instruments on the trees and they ceased to play them. The Babylonian masters asked the Israelite captives to sing the sacred songs used to worship God in the temple. Their request is a mockery of Israel's worship at the temple, an indirect attack on the character of YHWH because the songs of Zion celebrated the majesty and protection of YHWH over his people. In response to the captors' request, the Israelite captives refused to participate in the mockery of YHWH. Singing a song of Zion would be an insult to YHWH. It was impossible for the Israelite captives to sing a song intended to praise YHWH for the amusement of their masters.

However, for the psalmist, it is impossible to forget Jerusalem because that is his greatest joy. He, therefore, pledges complete loyalty and devotion towards Jerusalem and therefore, towards YHWH. The psalmist shows his passionate love for Jerusalem. The psalmist deems it impossible or unthinkable that he would forget Jerusalem and not exalt her. His devotion takes the form of a solemn vow invoking upon himself the penalty of total or partial paralysis, in which he would lose control of the most important organs of a musician - his hands and tongue - so that he would never be able to play his musical instrument or sing again, should he forget where his loyalty lies, namely Jerusalem.

The psalmist makes a petition to YHWH to punish the Edomites for their hostility towards Israel. He concludes by praying for divine retribution (lex talionis)44 on Babylon because of her ruthless atrocities against Judah (vv. 8-9). Babylon destroyed Jerusalem, the centre of the YHWH cult. YHWH's honour will only be restored if Babylon is destroyed. An inversion of roles is envisaged in the petition. In v. 1, Babylon is portrayed as a conqueror and in v. 8a, Babylon is destroyed. Babylon's destroyer will be blessed because he will be the instrument of divine retribution.

E GENRE, HISTORICAL AND LIFE SETTING OF PSALM 137

1 The literary genre of Psalm 137

There has been considerable disagreement amongst scholars with regards to the Gattung of Ps 137. Anderson and Schmidt point out that the psalm does not fit in any of the usual categories.45 With regards to the genre of the psalm, various suggestions have been given by scholars and exegetes:

-

Hermann Gunkel46 assigns the psalm to the category "Imprecatory Psalms" on the basis of its content.

-

Like Hermann Gunkel, Sigmund Mowinckel47 also classifies Ps 137 as an imprecatory psalm.

-

Schmidt48 calls Ps 137 a "ballad"; an epic poem recounting an event from the nation's history.

-

James Mays classifies Ps 137 as a song about Zion and not one of the "songs of Zion" because the songs of Zion are hymns full of joy, confidence and they portray Jerusalem as majestic and invincible.49

-

Hans-Joachim Kraus contends that Ps 137 is a communal lament.50

-

Leslie Allen sees Ps 137 as a modified version of a song of Zion.51

-

J.J. Burden argues that the main focus of Ps 137 is Zion and he views the psalm as an unusual song of Zion which also contains elements of lament and vengeance.52

-

Ulrich Kellermann argues that Ps 137 is Mischgattung consisting of a lament, a song of Zion and a curse.53

-

Like Kellerman, Prinsloo54 also proposes a Mischgattung for Ps 137. Stanza I (vv. 1-4) reveals the characteristics of communal lament, while Stanza II (vv. 5-6) display the formal elements of a song of Zion. However, the content of Stanza II do not reflect a song of Zion. He argues that the song of Zion is turned upside down and Stanza II is an individual lament with a strong element of self-imprecation. Stanza III (vv. 7-9) is a curse text where the blessing formula is again turned upside down and used to convey a curse rather than a blessing.55

-

Erhard Gerstenberger views the denomination of Ps 137 as a communal complaint. The lament is haphazard with regards to the elements which make up laments. The standard form of a lament seems to have been modified in Ps 137.

-

Albert Anderson56 sees Ps 137 as "a Communal Lament culminating in an imprecation upon the enemies."57

-

Leonard Maré58 also argues that Ps 137 should be classified as a communal lament because elements of lament, petition and vengeance all form an integral part of the structure of psalms of lament.

In light of the above views, and the structure and content of Ps 137, it is probably best to concur with those scholars59 who argue that Ps 137 is a Communal Lament or Complaint culminating in an imprecation on Israel's enemies. Psalm 137 may be seen as a communal lament because of the following reasons:

Firstly, as Anderson60 observes, the lament genre is determined by the opening verses of the Psalm. In Stanza I (vv. 1-4), there is a multiple occurrences of the first person plural forms and in Stanza II (vv. 5-6), there is a switch to the first person singular forms. This may be a literary device if the Psalm is a communal lament, where the singular is used collectively or representatively. The psalmist, in Stanza II (vv. 5-6), speaks on behalf of the exiled community in Babylon.

Secondly, as VanGemeren61 and Gerstenberger62 observe, imprecation is a common feature of Ps 137. The psalmist prays for God's judgment on the nations that mistreated Judah and were responsible for their misery.

Thirdly, the general literary structure of Ps 137 and the content are similar to that of a lament, even though the invocation and initial plea are missing. The psalm also has "a vow of allegiance instead of a vow of confidence or a vow to give thanks.63

Fourthly, the theme of being zealous for YHWH and his worship which is seen in one of the laments, Ps 69 (Ps 69: 9-10), is also seen in Ps 137.

2 The date and historical setting of Psalm 137

Kraus64 contends that Ps 137 is the only psalm that can be dated with certainty. He believes that the Babylonian Empire was still in existence when the psalm was written because in the psalm Babylon is doomed to destruction. The date should, therefore, be set as before 538 BCE.65 One unquestionable fact of Ps 137 is that the subject matter is the Babylonian exile.

As Vos66 and Prinsloo67 observe, the dating of Ps 137 has not been easy, and a number of suggestions have been made. The psalm could have:

-

Originated between 597 and 587 BCE, that is in Babylon between the first deportation and the final destruction of Jerusalem and exile.

-

Been written during the exile following 587 BCE. This implies that author was in exile before his return in 538 BCE.

-

Been written by someone who was neither in Babylon nor Jerusalem. The psalmist could have been someone from the Diaspora.

-

Been composed shortly after the exiles returned (538 BCE), but before the temple was completed in 515 BCE.

-

Originated after the completion of the temple, but before the rebuilding of the city walls, that is between 515 BCE and 445 BCE.

-

Originated after the destruction of Babylon in about 300 BCE. This date of origin is based on the passive participle הַשְּׁדוּדָה ("you devastated one") in Ps 137:8, which implies that Babylon was already destroyed when the psalm was written.

From the content of Ps 137, the author seems to have been in exile after the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BCE and may have been one of the temple musicians taken to Babylon as an entertainer. It was common for the conquering nations to take musicians from the conquered nations for their entertainment. For example, Sennacherib in his account of the siege of Jerusalem states that Hezekiah sent to him "male and female musicians" as part of his tribute.68 Most likely the psalmist and his companions shared a similar fate.69 The psalm seems to have been written by its author when he/she was no longer in exile, in Babylon, as indicated by the complete actions in vv. 1-370 and the repeated use of "there" (שָׁם) in vv. 1b and 3a. The adverb שָׁם shows that the land is distant and strange - not the place where the author finds himself at the time of writing.71 This implies that the psalm was written after the exile. The fact that Jerusalem is addressed directly in vv. 5-6 points to the possibility that the psalmist could have been in Jerusalem when he wrote the psalm. Therefore the psalm could have originated in the early years of the return of the Jews from exile,72 probably between 537 BCE and 515 BCE. During this period, the city of Jerusalem and the temple were in ruins73 and the memories of the Babylonian exile were still very fresh in the minds and hearts of the Jews.74 The psalmist's experience in Babylon and the devastating after-effects of the exile could have inspired him/her to compose the psalm. Probably the psalm was written by a member of the Levitical guilds, which were responsible for music and singing in the temple.75 Psalm 137 was an encouragement and comfort to God's despondent people since their city of Jerusalem and the temple were in ruins. YHWH was going to help them to rise again as a nation.

3 Cultic setting of Psalm 137

With regards to the cultic setting of Ps 137, Anderson76 believes that the psalm may have been intended for one of the Days of Lamentation,77 where prayers were offered for the full restoration of Jerusalem and its people. The Jews had been "the object of cursing among the nations,"78 but the psalmist pleads with God to reverse the situation.

Kraus79 argues that most likely Ps 137 was issued from an observance of the lamentation by the exiles. The exiled community of Jews could have gathered together at the streams of the canals to reminisce about the destruction of Jerusalem. Kraus80 suggests that exiles could have gathered at specific places such as in the houses of the elders or at the canals:

(i) to lament the ruined sanctuary in Jerusalem and to pray for a change of fortunes;

(ii) to search the Scriptures for proclamations about future events.

It can also be observed from 1 Kgs 8:46-53 that the praying assembly on such occasions assumed the "direction of prayer" facing toward Jerusalem.

Gerstenberger81 argues that the setting of Ps 137 "may have been a more elaborate worship service, in which it was intoned to express revulsion against continuing oppression and desire for change." The spirit of Ps 137 is communitarian, melancholic and emotional. The setting may have been of a congregation of people under pressure from majority groups and in trying to fight back, the congregation remembers the oppression and despair of the exilic period and use it either as a memory of misery or symbolically in place of their own suffering. Since the Jews had special worship services to commemorate the fall of Jerusalem,82 the psalm could have been attributed to this event.

As observed in the previous section 2, Ps 137 could have provided comfort and encouragement for the post-exilic Jews who were rebuilding the temple and walls of Jerusalem. The psalm assuages the shock and disillusionment caused by the exile.83 Probably the purpose of the psalm is to make the burden of the exile more tolerable and to encourage the post-exilic community to move on with their lives and put their hope in YHWH. Therefore, most probably, the psalm could have been used at the festival of lamentation over the destruction of Jerusalem,84 where prayers were offered to YHWH for the full restoration of Jerusalem and its people.85

F CANONICAL CONTEXT OF PSALM 137

Psalm 137 belongs to the fifth book of Psalms (107-150). Book 5 is the last and longest of the five books of the Psalter. Book 5 may be sub-divided into the following:86

-

Psalms 107-110: A further Exodus Psalm (Ps 107) and the third Davidic collection (Pss 108-110).

-

Psalms 111-119: Three acrostics (Pss 111, 112, 119) and the first Hallel (Pss 113-118).

-

Psalms 120-134: The Songs of Ascents.

-

Psalms 135-145: The second Exodus collection (Pss 135-137) and the fourth Davidic collection (Pss 138-145).

-

Psalms 146-150: The final Hallel

From the above sub-divisions of Book 5, it is clear that Ps 137 belongs to the fourth sub-division. In the fourth sub-division, Ps 137 belongs to the sub-group referred to as "the second Exodus collection" - Pss 135-137.87 Psalms 135-137 are positioned between the "Songs of Ascents" and David's final collection. Scholars ask why Pss 135-137 are grouped together and canonically positioned between the "Songs of Ascents" and David's final collection. Michael Wilcock88 argues that in some ways these psalms (135-137) look back to the Songs of Ascents; thus Ps 135 begins and ends like Ps 134 and may be an expansion of it. He also points out that one of the Jewish traditions actually joined Pss 134 and 135 together and if "Hallelujah" was meant as a coupling between psalms in the Egyptian Hallel, this may be the case also with Ps 134 and 135. It is obvious that Ps 136 has a close relationship with Ps 135; this probably explains why the term "Great Hallel" is sometimes applied to Pss 120-136.89 Therefore, it is reasonable to regard Pss 135-137 as a supplement or appendix to the Songs of Ascents.90

As Ernst Wendland91 observes some of the preceding psalms in the Zion salvation corpus seem to point forward to Ps 137:

-

In Ps 126, YHWH brought back the captives of Zion (v. 1) and as a result, their tongues were filled with songs of gladness (v. 2, cf. Ps 137:3, 6).

-

In Ps 129, YHWH is petitioned to punish "all who hate Zion" in the same way as they ferociously terrorized God's people (vv. 1-4).

-

Ps 132 speaks well of Zion as the "dwelling place" of YHWH and his anointed king (vv. 11-18); the "gladness" of God's saints (v. 16) will contrast with the "shame" of all their enemies (v. 18).

The three psalms exhort Israelites to remember Zion. That is why some commentators92 view Pss 135, 136 and 137 as a supplement or appendix to the "song of ascent corpus" which variously highlights the total loyalty-to-YHWH theme which is prominent in Pss 120-134. In Ps 137, the psalmist's zeal love for Zion is not separate from love for God. The imprecations in vv. 7-9 are not motivated by personal revenge but zeal/love for YHWH. YHWH's honour is at stake here and will be restored if Babylon is destroyed because Babylon had destroyed Jerusalem.

Clinton McCann93 argues that Pss 135-137 function as the prelude to David's last collection. The first and last psalms of this collection return to the theme of God's loving-kindness in Books IV-V.94 David's final collection, Pss 138-145, mainly consists of laments and culminates in Ps 144, which is a royal lament.

Structurally, Pss 105-119 are parallel to Pss 135-149. The earlier sequence begins with Pss 105-107, which reviews the exodus from Egypt and return from Babylon. The latter sequence which begins with Pss 135-137 also reviews the exodus from Egypt and return from Babylon. In each sequence (Pss 105-107; 135-137), a group of Davidic psalms follows (Pss 108-110; 138-145), then a set of Hallel psalms, and the Hallels lead up to Ps 119 in the one case and Ps 149 in the other.95

Psalm 137 shares common themes with Pss 135-136.

Thematically, both Ps 135 and Ps 136 focus on YHWH's great acts of redemption in the past. The deliverance of Israel from slavery is of particular importance in both psalms (135:8-12 // 136:10-22). The theme of Israel's deliverance from hostile nations is seen in both psalms (135:10-11 // 136:18-20). The theme of God's work in and sovereignty over his creation is seen in both psalms (135:6-7 // 136:14-9). The theme that God gave land to Israel as an inheritance is seen in both psalms (135:12 // 136:21-22).

Thematically, Ps 135:1-3 calls those who minister at the sanctuary to praise YHWH, to sing praises to him because of his goodness. In Ps 137:3-4, the Babylonian captors ask the Israelite captives, the temple musicians to sing the songs of Zion or YHWH. The request of the Babylonian masters is a mockery to YHWH because Babylon had destroyed Jerusalem and the temple. In Psalm 135, God's people are exhorted to sing songs of praise because of YHWH's goodness, whereas, in Ps 137, the temple musicians are asked to sing songs of YHWH not because of YHWH's goodness but as a mockery of YHWH. The psalmist calls down severe imprecations against Babylon.

Psalms 135 and 136 mention specific ways in which God's goodness has been demonstrated in the history of Israel (135:4-11; 136:10-24). He is sovereign and he is the creator of the whole universe; he does as he pleases in his universe and he controls all the forces of nature (135:6-7; 136:4-9). He redeemed Israel from Egypt through his miraculous power (135:8; 136:10-16). He gave victory to Israel over their enemies, the Canaanites (135:10-11; 136:17-20). The theme of YHWH's sovereignty in the universe is also seen in the events that transpire in Ps 137. God's sovereignty is also seen in history since he does what he pleases. Israel's exile in Babylon was part of God's plan, but unfortunately, the Babylonian captors did not see it that way - they saw the exile of the Jewish people as YHWH's failure to protect his people against them. The basis of the imprecations in vv. 8-9 is YHWH's sovereignty and not the psalmist's individual hatred or the people of Judah's hatred toward Babylon. As a sovereign God, YHWH was able to punish Edom for their hostility against Judah, and Babylon for their atrocities against Judah and for destroying the temple in 587 BCE. As sovereign Lord, YHWH is able to bless the destroyer of Babylon which shows that he is in control of history.

Psalms 135 and 136 state that YHWH gave land to his people as an inheritance (135:12; 136:21-22 cf. Deut 4:21, 38; 12:9), whereas there is a contrast in Ps 137. The Israelites are not in the land that God gave them as an inheritance but are in exile in Babylon. The exiled community of Israelites experienced a deep sense of loss and grief when they remembered the temple and Zion.96

The theme that God vindicates and shows compassion on his people in Ps 135:14 is also seen in Ps 137. In Ps 137:7, the psalmist makes a petition to YHWH to punish the Edomites for their hostility towards Israel. Therefore, YHWH is called upon to vindicate his people by punishing the Edomites because they had conspired with the Babylonians when they captured and destroyed Jerusalem in 587 BCE. In Ps 137:8-9, the psalmist prays for the destruction of Babylon. He wants Babylon to experience the same treatment that they gave Israel. Therefore, the basis for imprecations in vv. 8-9 is divine retribution and not the psalmist's or the captives' hatred toward the Babylonians.

The theme of "remembering" is also common in Pss 135, 136 and 137. In Ps 135, YHWH's name is everlasting and is brought to remembrance (זכר) by all generations (135:13). Psalm 137 is a fulfilment of Ps 135:13. In Ps 137, the Israelite captives remembered (זכר) the destruction of the temple and their sad memory caused them to mourn (137:1). The psalmist invokes a curse on himself: if he does not remember (זכר) Jerusalem (which also amounts to not remembering YHWH), he should lose his ability to sing songs of Zion with his mouth (137:6). In Ps 136, YHWH's remembering of Israel is related to deliverance (136:22-23). In Ps 137, YHWH's remembering of Edom is associated with judgment.

Therefore, Psalms 135-137 have thematic links. The two main themes in Pss 135-137 are YHWH's sovereignty and complete loyalty to YHWH (which is also a prominent theme in Pss 120-134). YHWH's sovereignty: God is sovereign; he is the creator of the universe. He controls the forces of nature and course of history. Psalms 135-137 may be seen as an appendix to the "Songs of Ascents" (Pss 120-134) because the Songs of Ascents portray the threats and difficulties of various kinds that could have been encountered by the post-exilic community as they travelled from Babylon to Zion. Psalms 135-137 may have provided comfort and support to the post-exilic community as they meditated on these psalms and learnt that God is sovereign; he controls the course of history. He was with them in exile, in Babylon. God's presence and protection were going to be with them during their journey back to Jerusalem. Psalms 135-137 may also be seen as a prelude to Pss 138-144 because these psalms focus on God's sovereignty and faithfulness. Since the main theme of Pss 135-137 is God's sovereignty, Pss 135-137 function as an introduction to Pss 138-144 because these psalms explain in detail the theme of YHWH's sovereignty. In Ps 137, the psalmist appeals to the sovereign YHWH to mete out his divine justice by punishing Edom and Babylon for their atrocities against Judah.

Complete loyalty to YHWH: In Ps 137, the psalmist has complete loyalty and devotion towards YHWH. The psalmist's love for Jerusalem and Zion is not separate from the love of God. The psalmist's devotion to YHWH is seen when he deems it impossible or unthinkable that he would forget Jerusalem. His devotion takes the form of a solemn vow invoking upon himself the penalty of total or partial paralysis, in which case he would lose control of the most important organs of a musician - his hands and tongue.

Psalm 137 may have provided comfort and encouragement for the post-exilic Jews who were rebuilding the temple and walls of Jerusalem. The psalm may have encouraged them to continue in their complete loyalty to YHWH, move on with their lives and put their hope and trust in YHWH.

G IMPRECATORY IMPLICATIONS IN PSALM 137

Most psalms in the Scriptures are cherished by Christians except for Ps 137. The closing verses of Ps 137 are often seen as "unimaginable cruelty".97 Therefore, in Christian songs and worship services, the last verses of Ps 137 are normally omitted.98 What are the imprecatory implications and message of Ps 137?

While many Christians view vv. 7-9 as "unimaginable cruelty," the historical setting of Ps 137 is the Babylonian exile and the psalm should be understood in light of its historical context. It is important to understand what was at stake for the exiled people of Judah. Deportation by the Babylonians was cruel: Judah lost not only their homeland but also the temple, where their God had revealed himself.99 Therefore, the very existence of the people of Judah and their faith in YHWH were jeopardised.100

The expression of dashing infants on rocks has been misunderstood as the psalmist's thirst for revenge or cruelty but this is not the case. In ancient warfare, it was common for victorious armies to kill the children of their conquered enemies. The expression of dashing infants on rocks implies proportionate divine retribution for the terrible wrong that the Babylonians had done and for which they should be punished.

The imprecations in the closing verses of Ps 137 are not motivated by a spirit of personal revenge or cruelty on the part of the psalmist, but rather by divine retribution. The Edomites and Babylonians are to be punished because of the way they mistreated Judah. YHWH is called upon to vindicate his people by punishing the Edomites for their conspiracy with the Babylonians when they captured and destroyed Jerusalem in 587 BCE. The Babylonians were well known for their cruelties and in this manner, they had captured Judah and destroyed the temple and the city of Jerusalem. Therefore, the psalmist prays to YHWH so that he would bring on the Babylonians the atrocities they had committed in Judah (lex talionis) so that in like manner they would experience utter defeat, helplessness and defencelessness.

The Babylonians are also to be destroyed because they had destroyed Jerusalem, the centre of the YHWH cult. YHWH's honour will only be restored if Babylon is destroyed. Hence, a blessing is pronounced on Babylon's destroyer because he will be an instrument of divine judgment.

As seen from the canonical context, the psalmist probably prays severe imprecations against Babylon not only because of their atrocities against Judah when Jerusalem fell but also because of their mockery of YHWH and the faith of the Judeans in captivity.

There is also an inversion of roles in Ps 137: In v. 1 - Babylon is portrayed as a conqueror; in v. 8a - Babylon is destroyed. Babylon's destroyer will be blessed because he will be an instrument of divine retribution. The focus of Ps 137 is not so much on imprecation but on YHWH's sovereignty. The canonical context of Ps 137 also confirms this as the main theme. YHWH as the Sovereign Lord who controls history is able to destroy Babylon, a powerful nation that had conquered many nations.

As already observed, there are multiple incidences of the first person plural forms in vv. 1-4 and in vv. 5-6, there is a switch to the first person singular forms. The use of this literary device suggests that the psalm is a communal lament, where the singular is used collectively or representatively. Therefore the psalmist in vv. 5-6 expresses on behalf of the community the sentiments of all the people concerning Jerusalem. So when the psalmist prays imprecations on Edom and Babylon he is not vengeful in act or spirit but he makes a prayer on behalf of God's people. He prays for divine vengeance. He submits his prayer to God and he leaves vengeance to God. It is YHWH who is to punish Edom and Babylon rather than the psalmist.

The message of Ps 137 to the followers of YHWH is that when the present world system may pressurize them to mock God and ultimately abandon their faith, they should continue to honour YHWH and persevere in trusting him. Even though it may seem that they live in exile far removed from God, literally or figuratively,101 in those situations, the followers of YHWH should refuse to participate with the ungodly in the mockery of God. Instead, they should stand firm in their faith and remain loyal and devoted to YHWH. No matter how difficult the present circumstances may be, YHWH's followers can trust YHWH because he is sovereign and in control of the course of history102 and ultimately he will vindicate his honour and the faith of his people. Thus, the sovereignty of God over everything gives hope and comfort for the present to the followers of YHWH.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Leslie C. Psalms 101-150. WBC 21. Dallas, TX: Word Books. 1983. [ Links ]

Anderson, Arnold A. Psalms 73-150. Vol. 2 of The Book of Psalms. NCB. London: Butler & Tanner, 1972. [ Links ]

Bar-efrat, Shimon. "Love of Zion: A Literary Interpretation of Psalm 137." Pages 3-11 in Tehillah le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic studies in honor of Moshe Greenberg. Edited by Mordechai Cogan, Barry L. Eichler, and Jeffrey H. Tigay. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997. [ Links ]

Beekman, John and John Callow. "Translating the Word of God with Scripture and Topical Indexes." Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1974. [ Links ]

Bratcher Robert G. and William D. Reyburn. A Translator's Handbook on the Psalms: Helps for Translators. New York, NY: United Bible Societies, 1991. [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles A. and Emilie G. Briggs. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. 2 vols. ICC. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1906-1907. [ Links ]

Broyles, Craig C. Psalms. NIBCOT 11. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1999. [ Links ]

Burden, Jasper J. Psalms 120-150. SBG. Kaapstad: NG Kerk-Uitgewers, 1991. [ Links ]

Cotterell, Peter and Max Turner. Linguistics and Biblical Interpretation. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Davidson, Robert. The Vitality of Worship: A Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, Franz. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms. vol. 3 Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980. [ Links ]

Des Camp, Mary Therese. "Blessed are the Baby Killers: Cognitive Linguistics and the Text of Psalm 137." Society of Biblical Literature 2006 Seminar paper, 14 pages. Online: https://www.sbl-site.org/assets/pdfs/DesCamp_Blessed.pdf. [ Links ]

Eaton, John H. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary - with an Introduction and New Translation. London: T & T Clark, 2003. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations. FOTL 15. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. Psalms 90-150. Vol. 3 of Psalms. BCOTWP. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008. [ Links ]

Gräbe, Ina. "Theory of Literature and Old Testament Studies: Narrative Conventions as Exegetic Reading Strategies." OTE 3/1 (1990): 43-59. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968. [ Links ]

Jenni, Ernst, with assistance from Claus Westermann, eds. Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament. Translated by Mark E. Biddle. 3 vols. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1997. [ Links ]

Keel, Othmar. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997. [ Links ]

Kellermann, Ulrich. "Psalm 137." ZAW 90/1 (1978): 43-58. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1978.90.1.43 [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalms 60-150: A Commentary. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1989. [ Links ]

Maré, Leonard P. "Psalm 137: Exile - Not the time for singing the Lord's Song." OTE 23/1 (2010): 116-128. [ Links ]

Mays, James L. Psalms. IBC. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1994. [ Links ]

McCann, Clinton J. "The Book of Psalms." Pages 641-1280 in 1 & 2 Maccabees; Introduction to Hebrew Poetry; Job; Psalms. Vol. 4 of The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996. [ Links ]

Motyer, J. Alec. "Psalms." Pages 446-547 in New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition. Edited by Donald A. Carson, Gordon J. Wenham, J. Alec Motyer, and R. T. France, 3rd ed. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, Sigmund. The Psalms in Israel's Worship. Translated by D. R. Ap-Thomas. 2 vols. New York: Abingdon, 1962. [ Links ]

Ogden, Graham S. "Prophetic Oracles against Foreign Nations and Psalms of Communal Lament: The Relationship of Psalm 137 to Jeremiah 49:7-22 and Obadiah." JSOT 24 (1982): 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908928200702406 [ Links ]

Oppenheim, Adolf L. "Assyrian and Babylonian Historical Texts." Pages 265-317 in The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Edited by James B. Pritchard. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T. M. "Analysing Old Testament Poetry: An Experiment in Methodology with Reference to Psalm 126." OTE 5/2 (1992): 221-251. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. Van kateder tot kansel. Pretoria: NG Kerkboekhandel Transvaal, 1984. [ Links ]

_______. "A Comprehensive Semiostructural Exegetical Approach." OTE 7/4 (1994): 78-83. [ Links ]

_______. "Psalm 137: Ecclesia Pressa, Ecclesia Triumphans." Pages 281-293 in Die lof van my God solank ek lewe. Edited by Willem S. Prinsloo. Irene: Medpharm, 2000. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Hans. Die Psalmen. HAT. Tübingen: Mohr, 1934. [ Links ]

Seybold, Klaus. Die Psalmen. HAT 1/15. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1996. [ Links ]

Silva, Moisés. "Let's be Logical: Using and Abusing Language. Pages 49-65 in An Introduction to Biblical Hermeneutics: The Search for Meaning. Edited by Walter C. Kaiser and Moisés Silva. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007. [ Links ]

Strawn, Brent A. "Psalm 137." Pages 345-353 in Psalms for Preaching and Worship. Edited by Roger E. Van Harn and Brent A. Strawn. LCom. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009. [ Links ]

Tucker Jr., W. Dennis. Constructing and DeconstructingPowerinPsalms 107-150. AIL 19. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014. [ Links ]

Van Dyk, Peet. "Violence and the Old Testament." OTE 16/1 (2003): 96-112. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem A. "Psalms." Pages 1-880 in Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs. Vol. 5 of Expositor's Bible Commentary. Edited by Frank E. Gæbelein. 12 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991. [ Links ]

Vos, Cas, J. A. Theopoetry of the Psalms. Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2005. [ Links ]

Walton, John H. "Retribution." Pages 647-655 in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry and Writings. Edited by Tremper Longman III and Peter Enns. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Wendland, Ernst R. Analyzing the Psalms. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1998. [ Links ]

_______. "Bible Translation as "Ideological Text Production" with Special Reference to the Cultural Factor and Psalm 137 in Chichewa." OTE 17/2 (2004): 315-343. [ Links ]

Wilcock, Michael. The Message of Psalms 73-150. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Wiseman, Donald J. "Historical Records of Assyria and Babylonia." Pages 46-83 in Documents from the Old Testament Times. Edited by D. Winton Thomas. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1958. [ Links ]

Submitted: 15/09/2017

Peer-reviewed: 15/12/2017

Accepted: 01/03/2018

Dr Daniel Simango, Extra-ordinary Researcher, Unit for Reformed Theology and the development of the South African Society, North-West University. He is also the Principal and Senior OT Lecturer of the Bible Institute of South Africa, 180 Main Road, Kalk Bay, 7975 near Cape Town. RSA. Email: danielsimango@outlook.com. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7651-7813

1 Gert T. M. Prinsloo, "Analysing Old Testament Poetry: An Experiment in Methodology with Reference to Psalm 126," OTE 5/2 (1992): 221-251; Willem S. Prinsloo, "A Comprehensive Semio-structural Exegetical Approach," OTE 7/4 (1994): 78-83; Ina Gräbe, "Theory of Literature and Old Testament Studies: Narrative Conventions as Exegetic Reading Strategies," OTE 3/1 (1990): 43-59.

2 Prinsloo, "Analysing Old Testament Poetry," 230; Prinsloo, "Comprehensive Semio-structural," 81-82.

3 Ernst R. Wendland, Analyzing the Psalms (Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1998).

4 John Beekman and John Callow, Translating the Word of God with Scripture and Topical Indexes (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1974), 69-73.

5 Peter Cotterell and Max Turner, Linguistics and Biblical Interpretation (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1989).

6 Moisés Silva, "Let's be Logical: Using and Abusing Language," in An Introduction to Biblical Hermeneutics: The Search for Meaning, ed. Walter C. Kaiser and Moisés Silva (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 49-65.

7 Prinsloo, "Analysing Old Testament Poetry," 230.

8 This subdivision of Psalm is discussed in Section C.

9 Willem S. Prinsloo, Van kateder tot kansel (Pretoria: NG Kerkboekhandel Transvaal, 1984), 116.

10 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 117.

11 Ernst R. Wendland, "Bible Translation as 'Ideological Text Production' - with Special Reference to the Cultural Factor and Psalm 137 in Chichewa," OTE 17/2 (2004): 319.

12 Mary Therese Des Camp, "Blessed are the Baby Killers: Cognitive Linguistics and the Text of Psalm 137," Society of Biblical Literature 2006 Seminar paper, p. 3, online: https://www.sbl-site.org/assets/pdfs/DesCamp_Blessed.pdf.

13 Charles A. Briggs and Emilie G. Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms, 2 vols., ICC (Edinburgh: T & T Clark. 1906-1907), 2:484; Arnold A. Anderson, Psalms 73-150, vol. 2 of The Book of Psalms, NCB (London: Butler & Tanner, 1972), 896; Leslie C. Allen, Psalms 101-150, WBC 21 (Dallas, TX: Word Books, 1983), 240; Prinsloo, Van kateder, 117; Willem A. VanGemeren, "Psalms," in Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, vol. 5 of Expositor's Bible Commentary, ed. Frank E. Gæbelein, 12 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991), 826; James L. Mays, Psalms, IBC (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1994), 422; J. Alec Motyer, "Psalms," in New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition, ed. Donald A. Carson, et al., 4th ed. (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1994), 577; Clinton J. McCann, "The Book of Psalms," in 1 & 2 Maccabees; Introduction to Hebrew Poetry; Job; Psalms, vol. 4 of The New Interpreter's Bible, ed. Leander E. Keck (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996), 1227; Shimon Bar-Efrat, "Love of Zion: A Literary Interpretation of Psalm 137," in Tehillah le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic studies in honor of Moshe Greenberg, ed. Mordechai Cogan, Barry L. Eichler, Jeffrey H. Tigay (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 3-11; Robert. A Davidson, The Vitality of Worship: Commentary on the Book of Psalms (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 439-441; Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms, Part 2, and Lamentations, FOTL 15 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 390; John H. Eaton, The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary - with an Introduction and New Translation (London: T & T Clark, 2003), 454; Leonard P. Maré, "Psalm 137: Exile - Not the time for Singing the Lord's Song," OTE 23/1 (2010): 117.

14 Gerstenberger, Psalms, 2:390.

15 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 898.

16 Fritz Stolz, "צִיּוֹןi," TLOT 2:1071-1076 (1072); Robert G. Bratcher and William D. Reyburn, A Translator's Handbook on the Psalms: Helps for Translators (New York, NY: United Bible Societies, 1991), 1113.

17 Bratcher and Reyburn, Translator's Handbook on the Psalms, 1114

18 John Goldingay, Psalms 90-150, vol. 3 of Psalms, BCOTWP (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 604.

19 See Pss 46; 48; 76; 84; 87 and 122.

20 W. Dennis Tucker, Jr., Constructing and DeconstructingPowerinPsalms107-150, AIL 19 (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014), 156.

21 Cf. Pss 42:3, 10; 79:10; 115:2.

22 Cas J. A. Vos, Theopoetry of the Psalms (Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2005), 267.

23 VanGemeren, "Psalms," 827.

24 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 117.

25 Bratcher and Reyburn, Translator's Handbook on the Psalms, 1116.

26 VanGemeren, "Psalms," 828. McCann, "Psalms," 1227.

27 VanGemeren, "Psalms," 828.

28 VanGemeren, "Psalms," 828.

29 Vos, Theopoetry, 268.

30 Klaus Seybold, Die Psalmen, HAT 1/15 (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr [Paul Siebeck], 1996), 510.

31 Vos, Theopoetry, 269.

32 See Obad 10-14; Ezek 25:12-14; 35:5-6.

33 See John H. Walton, "Retribution," in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry and Writings, ed. Tremper Longman III and Peter Enns (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 651.

34 Vos, Theopoetry, 266.

35 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 128.

36 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 128.

37 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 128; Mays, Psalms, 423.

38 Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 60-150: A Commentary (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1989), 504.

39 Cf. 2 Kgs 8:12; Isa 13:16; Hos 13:16; Amos 1:3, 13; Nah 3:10.

40 Othmar Keel, The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 9; Peet Van Dyk, "Violence and the Old Testament," OTE 16/1 (2003): 96.

41 Graham S. Ogden, "Prophetic Oracles against Foreign Nations and Psalms of Communal Lament: The Relationship of Psalm 137 to Jeremiah 49:7-22 and Obadiah," JSOT 24 (1982): 89-97.

42 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 900; Brent A. Strawn, "Psalm 137," in Psalms for Preaching and Worship, ed. Roger E. Van Harn and Brent A. Strawn, LCom (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 349-350.

43 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 128-129; Mays, Psalms, 423; Wendland, "Bible Translation," 326.

44 See Tucker, Constructing and Deconstructing, 123.

45 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 896; Hans Schmidt, Die Psalmen, HAT (Tübingen: Mohr, 1934), 242.

46 Hermann Gunkel, Die Psalmen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968), 265.

47 Sigmund Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel's Worship, trans. D. R. Ap-Thomas, 2 vols.(New York: Abingdon, 1962), 2:51-52.

48 Schmidt, Psalmen, 242.

49 Mays, Psalms, 421.

50 Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 501.

51 Allen, Psalms 101-150, 241.

52 Jasper J. Burden, Psalms 120-150, SBG (Kaapstad: NG Kerk-Uitgewers, 1991), 122.

53 Ulrich Kellermann, "Psalm 137," ZAW 90/1 (1978): 53.

54 Willem S. Prinsloo, "Psalm 137: Ecclesia Pressa, Ecclesia Triumphans," in Die lof van my God solank ek lewe, ed. Willem S. Prinsloo (Irene: Medpharm, 2000), 285-286.

55 Prinsloo, "Psalm 137," 285.

56 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897.

57 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897."

58 Maré, "Psalm 137," 118.

59 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 896-897; Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 501; Gerstenberger, Psalms, 2:394 and Maré, "Psalm 137," 118.

60 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897.

61 VanGemeren, "Psalms," 826.

62 Gerstenberger, Psalms, 2:394.

63 Gerstenberger, Psalms, 2:394.

64 Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 501.

65 Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 501.

66 Vos, Theopoetry, 272.

67 Prinsloo, Van kateder, 121-123.

68 Donald J. Wiseman, "Historical Records of Assyria and Babylonia," in Documents from the Old Testament Times, ed. D. Winton Thomas (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1958), 67.

69 Adolf L. Oppenheim, "Assyrian and Babylonian Historical Texts," in The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958), 205.

70 Ogden, "Prophetic Oracles," 89.

71 Franz Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Psalms, vol. 3 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 3:335; Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897; Allen, Psalms 101-150, 239; Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 501-502; Vos, Theopoetry, 273.

72 Maré, "Psalm 137," 119; Wendland, "Bible Translation," 322.

73 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897; Davidson, Vitality of Worship, 439.

74 McCann, "Psalms," 1227.

75 See 2 Chr 25:1-8; Ezra 2:40-42; McCann, "Psalms," 1227.

76 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897.

77 Cf. Zech 7:1-5.

78 Zech 8:13.

79 Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 502.

80 Kraus, Psalms 60-150, 502.

81 Gerstenberger, Psalms, 2:395.

82 Cf. Zech 7:3-6; Lamentations.

83 Vos, Theopoetry, 274.

84 Cf. Zech 7:1-5; 8:19.

85 Anderson, Psalms 73-150, 897; Allen, Psalms 101-150, 239; Davidson, Vitality of Worship, 439; Eaton, Psalms, 454; Vos, Theopoetry, 273.

86 Michael Wilcock, The Message of Psalms 73-150 (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2001), 145, 168-169, 219-220, 246, 274.

87 Wilcock, Psalms 73-150, 246.

88 Wilcock, Psalms 73-150, 246.

89 VanGemeren, "Psalms," 713.

90 McCann, "Psalms," 664; Wilcock, Psalms 73-150, 246.

91 Wendland, "Bible Translation," 325.

92 For example McCann, "Psalms," 664; Wilcock, Psalms 73-150, 246; Allen, Psalms 101-150, 239.

93 McCann, "Psalms," 664.

94 See Pss 138:2, 8; 145:8; see also Pss 89; 90; 106; 107; 118.

95 Wilcock, Psalms 73-150, 246.

96 McCann, "Psalms," 1227.

97 Craig C. Broyles, Psalms, NIBCOT 11 (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1999), 479.

98 McCann, "Psalms," 1228.

99 See Pss 135:12; 136:21-22; cf. Deut 4:21, 38; 12:9.

100 Broyles, Psalms, 479.

101 Vos, Theopoetry, 275.

102 Vos, Theopoetry, 275.