Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 n.3 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n3a14

ARTICLES

The Levites' exclusion from land allotment: The Joshua story in dialogue with the Joseph story

Hulisani Ramantswana

Unisa

ABSTRACT

In this paper, an African proverb or saying, Mapfene hu la mahul-wane (literally, "The baboons who get to eat are the big ones"), the tenor of which is that the ones who tend to benefit from the system are those in position of power while the rest have to eat the crumbs or nothing at all, is utilized as a lens to engage the issue of the exclusion of the Levites from owning land. Utilizing the proverb of my interrogation as a lens, the Joshua story (especially Jos 14, 16-17) is read in dialogue with the Joseph story. This paper, therefore, argues that the Levites' loss of land was due to a coup by the Josephite tribes under the leadership of Hoshea (Joshua) son of Nun from the tribe of Ephraim. The Levites' exclusion from land, thus, reflects the privileging of those in power at the expense of the tribe of Levi, which was relegated to a lower class. The paper also engages the current South African politico-economic context, in which those in political power enrich themselves by grabbing what they can at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Keywords: Levites, Josephites, land, legitimation, Joshua story, Joseph story

A INTRODUCTION

The exclusion of the Levites from land allotment evokes historical memories in terms of the South African context of the colonial-apartheid exclusion and dispossession of black people from their land by the white minority, which resulted in whites owning 87% percent of the land and the black majority owning only 13% of the land in small pockets called homelands or reserves or Bantustans. The colonial-apartheid narrative behind the land grabs and the massacres that accompanied them are were based on the social classification of people on the basis of race, with the white or European as superior and the rest as inferior.1 The colonialists' self-justification narrative was that the homelands would promote self-governance for the different ethnic groups; this was in fact a cover-up for the condemnation of the black masses to landlessness and poverty. The landless-ness of indigenous people continues even in the so-called post-colonial, postapartheid South Africa, since many black people continue to live in appalling conditions - in squatter camps, in shacks, under bridges, under trees, in poorly serviced areas, and so on. The landless are expected to be understanding of the slow progress in the land reform process by the current political elites, who, in the fear of the global structures of coloniality, do not want to unsettle the markets and suffer the same fate as our neighboring country Zimbabwe.

This paper sets out to investigate a number of the underlying factors of the exclusion of the Levites from the land, taking into consideration the textual clues in the Hexateuch. The Hexateuch, when read along the grain, projects the Levites' exclusion from the right to land allotment as predicated on their special appointment for the service of YHWH at the sanctuary. In my view, this justification serves as part of a cover-up of the real factors that underlie the Levites' exclusion from land allotment. However, it should be noted that the chief aim of this paper is not to present a historical reconstruction of the origins of ancient Israel; rather, this paper presupposes that several narrative techniques were employed in shaping the biblical narrative.2 For the purposes of this paper, I note in particular the technique of thematic or plot parallels (type-scenes) which are discernible in some of the biblical stories in the OT.3 Thus, in the biblical narrative, earlier narratives or earlier generations tend to anticipate later narratives or later generations, for example, the Jacob-Esau narrative anticipates the Israel-Edom relationship, the Abraham-Lot narrative anticipates the Israel and Ammo-nites-Moabites relationship, and so forth. This phenomenon should be differentiated from the doublets or repetitions of the same stories (e.g., Gen 1:1-2:4a//Gen 2:4b-3:24; Gen 4//Gen 5) and repetitions of details within same stories (e.g., Gen 6-9; Exod 3:7-8, 9-10).4

In this paper, I make use of an African proverb, Mapfene hu la mahulwane (literally, "The baboons who get to eat are the big ones"), the tenor of which is that the ones who tend to benefit from the system are those in positions of power, while the rest have to eat the crumbs or nothing at all. I use the proverb as a lens to engage the issue of the Levites' exclusion from land allotment. Reading with the proverb of my interrogation in mind is a choice to read the text in the light of my own African knowledge system, which I prefer to refer to as the vhufa (heritage) approach.5 Reading through the aforementioned proverb entails an engagement in the hermeneutic of suspicion by seeking to uncover the underlying factors behind the pro-Joseph narrative thread within the Hexateuch. Furthermore, reading through our proverb implies reading in solidarity with those on the underside of the matrix of power - the excluded; that is, those who are negatively affected by the power relations in society. As Oeste observes regarding the issue of legitimacy and power holders:

A given power holder may exhibit some characteristics of legitimate rule without being fully legitimate or while losing legitimacy over the course of his tenure. Thus, negative actions also play an important role in establishing or maintaining the level of a ruler's legitimacy.6

Therefore, the argument in this paper is that the Hexateuch in its final form is to a certain extent a pro-Joseph narrative intended to legitimize the royal position of the Joseph tribe and to absolve the Joseph tribe from the possible atrocity committed against the tribe of Levi when they took over the royal position and claimed a double portion.

B THE HOUSE OF JOSEPH'S DEMAND FOR DOUBLE ALLOTMENT

The book of Joshua as a story of fulfilment of the promise of land is interlinked with the Pentateuch. The nature and extent of the relationship between the book of Joshua and the Pentateuch is a matter of debate among scholars.7 The book of Joshua, when read along the grain, is a story that brings to fulfilment the promise of land to the fathers - the patriarchs and the exodus generation. However, the land promise projected is one that excludes the Levites from land allotment, as predetermined under the leadership of Moses. In this reading, it was Moses who excluded the Levites from land ownership: "To the tribe of Levi, however, Moses gave no heritage; YHWH, God of Israel, was his heritage, as he had told him" (Josh 13:33). The allotment of pasture lands, cities of refuge, and the forty-eight cities to the Levites in Josh 21 is presented as a fulfilment of Num 35:1-8.

The ideology of the exclusion of Levites from land allotment is contained in Numbers, Deuteronomy, and Joshua and completely absent in the Moses story as contained in Exodus and Leviticus, which to a large extent deals with the appointment, anointing, and service of the priests. In the book of Joshua, the exclusion of the Levites is thus presented as a fulfilment of what was stipulated during the era of Moses. Habel tends to regard the ideology of the exclusion of the Levites from land inheritance as a privileging of the Levites, the landless elite who have power over the landed tribes as the "divinely ordained heirs of Moses" who act as God's representatives in the land.8 However, in this paper, the land-lessness of the Levites is argued to have been the result of the negative power relationship between the house of Joseph and the tribe of Levi.

The African proverb Mapfene hu la mahulwane serves to highlight the negative results of power relationships. As Beetham notes with regard to power relations:

Power relations often involve negative features - of exclusion, restriction, compulsion, etc. - which stand in need of justification if the powerful are to enjoy moral authority as opposed to a merely de facto power.9

Those in power, as Beetham observes regarding social construction, tend to have resources that they can deploy to produce their own legitimacy by influencing the beliefs and institutions. In so doing, those in power intend to shape the expectations and interests of those who are governed. 10 Thus, the proverb of interrogation highlights the negative side of power and institutions of power, especially when they become handmaidens of disempowerment and inequality.

The capture of political power is often associated with access to opportunities for self-enrichment and the exclusion or oppression of the other. The exclusion of the Levites from land inheritance should also be viewed from the perspective of the power relationship among Israel's tribes when the so-called land promise was realized. There are elements within the text that serve to highlight the Levites' exclusion from land allotment as a result of the power relationship as exercised by the house of Joseph. The house of Joseph in the Joshua story can be described as mapfene mahulwane ("the big baboons") - that is, those in power.

The following elements should be noted in the Joshua story regarding the big baboons, especially in chs. 14, 16-17, which deal with the issue of land allotment:

First, Ephraim and Manasseh are in a number of instances treated as a unit - they are the "sons of Joseph" (Josh 14:4; 16:1, 4; 17:14, 16; 18:11; 26:27; cf. Gen 48:8; Num 26:28, 37; 36:1; 36:5; 1 Chr 7:29) or  ("house of Joseph"; Josh 17:17; cf. Gen 43:18, 19; 50:8; Judg 1:22, 23, 35; 2 Sam 19:21; 1 Kgs 11:28; Amos 5:6; Zech 10:6). Interestingly, the two also speak as a unit and are addressed as a unit (emphasis mine):

("house of Joseph"; Josh 17:17; cf. Gen 43:18, 19; 50:8; Judg 1:22, 23, 35; 2 Sam 19:21; 1 Kgs 11:28; Amos 5:6; Zech 10:6). Interestingly, the two also speak as a unit and are addressed as a unit (emphasis mine):

The sons of Joseph spoke as follows to Joshua, "Why have you given me only one share

only one portion, as heritage, when I am

a numerous people, since Yahweh has so blessed me?"

Joshua replied, "If your people are so many, go up to the wooded area and clear space for yourselves in the area belonging to the Perizzites and Rephaim, since the highlands of Ephraim are too small for you."

The sons of Joseph replied, "The highlands are not enough for us, and what is more, all the Canaanites living on the land of the plain have iron chariots, so do those in Beth-Shean and its dependent towns, and those in the plain of Jezreel."

Joshua said to the House of Joseph, to Ephraim and to Manasseh, "You are a numerous people and your strength is great; you will not only have one share,

but a mountain will be yours as well; even if it is a forest, you can clear it and its territories will be yours. And you will dispossess the Canaanites, although they have iron chariots and although they are strong" (Josh 17:14-18 NJB).

In Josh 17:14, when the Josephites demand more than one allotment, they speak in the first person singular. The way the demand for more than one lot is crafted is telling. It is phrased in the form of a complaint. This complaint is crafted in the first person singular, which further highlights that the Josephites were regarded as a unit. The complaint is basically that they are given as inheritance "one lot and one territory"

"one lot and one territory"

Secondly, the house of Joseph is allotted a single portion iust like any other tribe. Joshua 16:1a states, "Then the lot of the sons of Joseph came out"  This text clearly highlights that the sons of Joseph are treated as a unit and so receive a single lot for their tribe, iust like the other tribes. The one lot of the Josephites was then divided among the clans of Joseph, Ephraim and Manasseh.11

This text clearly highlights that the sons of Joseph are treated as a unit and so receive a single lot for their tribe, iust like the other tribes. The one lot of the Josephites was then divided among the clans of Joseph, Ephraim and Manasseh.11

The Josephites do not present any historical memory for the demand. Unlike Caleb, who appealed to the events in Kadesh-Barnea as the basis for a special allotment (Josh 14:6-15), they offer no such basis for their complaint.12There is no predetermined arrangement during the era of Moses to which they are able to point. This leads one to wonder, what is the basis of the Josephites' complaint?

The complaint gives us hints. The Josephites demanded more than one lot and one territory as their inheritance because they are numerous. Joshua's response to the Josephites also adds other dimensions: Firstly, he concurs with the Josephites' demand for more than one lot and one territory. Secondly, Joshua's motivation is that they are numerous and they have great power. It is not surprising that Joshua would concur with the demand of the Josephites, as he himself belonged to the same house, and he also had essentially royal power. The demand for more than one lot and one territory was based on their privileged status. The house of Joseph was an elite tribe, as it had the royal power through the person of Joshua, the supposedly legitimate successor of Moses. The demand for more than one land allotment and one territory can be seen as an act of the big baboons making a land grab. This act from the Josephites from a position of power would have negative results for at least one tribe, who would as a consequence be without land allotment. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the Levites had to beg for land when all the other tribes had received their share:

Then the heads of the families of the Levites came to the priest Eleazar and to Joshua son of Nun and to the heads of the families of the tribes of the Israelites; they said to them at Shiloh in the land of Canaan, "The LORD commanded through Moses that we be given towns to live in, along with their pasture lands for our livestock." So by command of the LORD the Israelites gave to the Levites the following towns and pasture lands out of their inheritance (Josh 21:1-3 NRSV).

The process of dividing the land among the tribal confederation as noted in Josh 19:51 ("So they finished dividing the land") was regarded as complete -a process that entirely excluded the Levites. The Levites were officially the landless other. It should be noted, however, that in Josh 13:14, 33, 18:7 a cultic justification is provided for the exclusion of the Levites from land allotment: Levites have the Lord as their inheritance and so they receive no land inheritance. This cultic justification alludes to Pentateuchal texts such as Num 18:20-24 and Deut 10:9; 18:1-2, and in so doing, the exclusion of the Levites is thus presented as matter of fulfilling a pre-ordained arrangement. Therefore, the statement in Josh 21:2, which is a clear reference to Num 35:2-3, seeks to legitimize the Levitical claim for towns to settle in "while contributing to the authors' portrayal of Joshua and his people as an obedient generation."13 As Albertz notes, the commission in Josh 21:1-3 "did not have much to do; it only had to ensure that the Penta-teuchal law was properly translated into action."14 In this way, the Joshua story is aligned with the Moses story.

It is, however, notable that in the Joshua story, the exclusion of the Levites from land is closely interlinked with the Josephites:

This was what the Israelites received as their heritage in Canaan, which was given them as their heritage by the priest, Eleazar, and by Joshua son of Nun, with the heads of families of the tribes of Israel.

They received their heritage by lot, as Yahweh had ordered through Moses, as regards the nine tribes and the half-tribe.

For Moses himself had given the two-and-a-half tribes their heritage on the further side of the Jordan, although to the Levites he had given no heritage with them.

Since the sons of Joseph formed two tribes, Manasseh and Ephraim, no share in the country was given to the Levites, apart from some towns to live in, with their pasture lands for their livestock and their possessions (Josh 14:1-4 NJB).

The redactional layer to the supposedly proto-Joshua story in Josh 14:1-4 serves as an attempt to exonerate the Josephites from their demand for more than one lot by retrojecting the decision to the era of Moses. In vv. 3 and 4, two motivations that do not necessarily complement each stand side by side. The motivation in v. 3 is in line with the cultic justification of the Deuteronomist. In my view, the remark in Josh 14:4, which is not cultically oriented, provides a more realistic picture and likely belongs to the proto-Joshua story.15 The cultic justification in this text should rather be viewed as an addition to the proto-Joshua story in line with the cultic justification projected in Numbers and Deu-teronomy.16 These two books, to a certain extent, help in furthering the ideology of the exclusion of the Levites from land inheritance by providing the cultic and military or the numeric justification of the exclusion of the Levites.

C LEGITIMIZATION OF THE DOUBLE ALLOTMENT: THE JOSEPH STORY

Pro-Joseph elements are liberally distributed throughout all the books in the Pentateuch, except Leviticus. The Joseph story in Gen 37-50 elevates the house of Joseph to the same status as that of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Joseph's bones, like those of the other three patriarchs, had to be buried in the Promised Land, and so the Exodus generation travels with the bones of Joseph (Exod 13:19; cf. Gen 50:25-26). Joshua, an Ephraimite, is set to be the successor of Moses, and the sons of Joseph form part of the twelve tribes at the exclusion of Levi (Numbers). The pro-Joseph elements in the Hexateuch are regarded as part of the non-Priestly source.17

The Joseph story (found within the toledot of Jacob), inasmuch as it functions as a pivot between the patriarchal cycles narrative and the Exodus story, also functions to predict and legitimize later events synchronically in the context of the Hexateuch (or the Ennateuch), and in particular their rise to royalty and their demand for a dual allotment.18 However, scholars tend to date the origin of the Joseph story at different periods. Historically, they regard it as originating within Israel's later political context, which it reflects. Those who detect wisdom features in the Joseph story tend to date its origin during the Solomonic period,19whereas others tend to date it to the exilic or post-exilic period.20 My interest in this paper is not in trying to establish the time of origin of this story or to establish which source is responsible for it; rather, my interest is in establishing the probable reasons for the Levites' exclusion from the land which lie behind the ideologies of the authors or redactors and their cover-up.

Those in power, past or present, as Beetham argues, "have a psychological need of self-justification, and all those socially advantaged need to see their advantage as deserved or legitimate, and not arbitrary."21 The legitimization of one faction or one rule in some instances goes hand in hand with the delegitimi-zation of another. For example, the power struggle between Saul and David in the book of Samuel serves to legitimize David within the overall scheme of things.22 The Judah and Tamar story in the Joseph story, as some have observed, may also viewed as an attempt from another faction within Israel to legitimize the Davidic line or the supremacy of the tribe of Judah in contrast to the tribe of Joseph.23 The Joseph story, in my view, served as part of the legitimization of the Josephites as a royal tribe and for their claim of dual allotment at the expense of the other tribes.

1 The royalty of Joseph prefigures the royalty of the House of Joseph

The Joseph story presents Joseph, and thus by default the house of Joseph, as the favorite house of Jacob. Joseph is presented as the favored son of Jacob: "Now Israel loved Joseph more than any other of his children, because he was the son of his old age, and he had made him a long robe with sleeves" (Gen 37:3, NRSV). Israel/Jacob's act of adorning his son with a decorated tunic functions as an act of conferring royal status upon Joseph over the family.24 The royal status is further confirmed through Joseph's two dreams:

(i) First dream: "There we were, binding sheaves in the field. Suddenly my sheaf rose and stood upright; then your sheaves gathered around it, and bowed down to my sheaf (Gen 37:7, NRSV).

(ii) Second dream: "The sun, the moon, and eleven stars were bowing down to me" (Gen 37:9).

In both instances, the brothers as well as Jacob realize what is at stake. The brothers' words are pointed in this regard:

("So you want to be king over us, you want to lord it over us," Gen 37:8). In the Joseph story as a self-contained story, what the brothers were afraid of seeing happen, and what they tried to stop from happening, does indeed happen when Joseph ascends to royal power within the Egyptian state. Just as Jacob dressed Joseph with a decorated tunic, so the Pharaoh enthrones Joseph and decorates him with a signet ring, a robe of fine linen, and a gold chain (Gen 41:42). When the brothers go to Egypt in search of food during the famine, the dream becomes (partially) fulfilled as the brothers

("So you want to be king over us, you want to lord it over us," Gen 37:8). In the Joseph story as a self-contained story, what the brothers were afraid of seeing happen, and what they tried to stop from happening, does indeed happen when Joseph ascends to royal power within the Egyptian state. Just as Jacob dressed Joseph with a decorated tunic, so the Pharaoh enthrones Joseph and decorates him with a signet ring, a robe of fine linen, and a gold chain (Gen 41:42). When the brothers go to Egypt in search of food during the famine, the dream becomes (partially) fulfilled as the brothers  ("bowed down to him with their faces to the ground," Gen 42:6, cf. 42:9).

("bowed down to him with their faces to the ground," Gen 42:6, cf. 42:9).

The right to lord it over his brothers in the case of Joseph may be viewed as being in line with the motif in Genesis and elsewhere in the OT of the younger being favored over the older, contrary to the custom of the eldest son assuming the role of head of the family or receiving the greater blessing - Abel over Cain, Isaac over Ishmael, Jacob over Esau.25 In the case of Jacob's household, he had two wives, Leah and Rachel, and the rightful head was supposed to have been Reuben, the first-born of Leah, the first wife; however, the favor went to Joseph, the first-born of the second wife, Rachel, the beloved wife. In the case of Leah and Rachel, the trickster himself was tricked into marrying the older sister first, rather than the younger one first. In this instance, the trickster reverses the trick by showing favor to the first-born of the second wife, the younger wife.26 In this way, Joseph is projected as the rightful candidate to assume the role of royalty over the family on the basis of father-favor.

The father-favor is again highlighted by Jacob's blessing of Joseph's sons. In Gen 48, Joseph takes his sons to receive blessings from his father Jacob; however, in that process Jacob adopts Joseph's sons as his own and puts them in the place of his two eldest sons - Reuben and Simeon:

Therefore your two sons, who were born to you in the land of Egypt before I came to you in Egypt, are now mine; Ephraim and Manasseh shall be mine, just as Reuben and Simeon are. As for the offspring born to you after them, they shall be yours. They shall be recorded under the names of their brothers with regard to their inheritance (Gen 48:5-6 NRSV).

Thus, Ephraim and Manasseh are placed in the position of Reuben and Simeon. The order is also significant - Ephraim takes the position of Reuben and Manasseh takes that of Simeon. Between the sons of Joseph, Manasseh and Ephraim, the one upon whom favor rests is the younger brother, Ephraim, and thus he is granted entrance into the scene of an Ephraimite who will potentially be the head of the house of Jacob. In the blessing of his sons, Jacob hands the royal baton to Joseph (Gen 49:26), and in particular to the Ephraimites. In so doing, the story paves the way for the grand entrance of Hoshea (Joshua) son of Nun, an Ephraimite, as the rightful royal candidate to deliver on the patriarchal promise of land.

The royal position of Joseph is one that is also endorsed by Moses, when he (like Jacob) blesses the twelve tribes towards the end of his life (33:13-17).The book of Deuteronomy basically concludes by following a pattern set by the book of Genesis - Jacob parallels Moses, and Joseph parallels Joshua. Before his death, Jacob hands the royal baton to Joseph's tribe, and in particular to Ephraim, just as Moses hands the royal baton to Joshua son of Nun, an Ephra-imite. The Joseph story was probably intended to delegitimize the other tribes' claim to royalty. Weber rightly notes that there is "generally observable need of any power, or even of any advantage of life, to justify itself."27 The need for those in power to justify themselves also goes hand in hand with the delegitimi-zation of others.

D THE DELEGITIMIZATION OF THE LEVITES

In legitimizing the house of Joseph, the Joseph story in the process delegitimizes other potential royal candidates. Reuben, the first-born, is already delegitimized as a candidate for royalty in Gen 35:22 for having sexual intercourse with his father's concubine Bilhah. With the delegitimization of Reuben as a royal candidate, the next logical candidate in line is Simeon, the second-born of Jacob. However, Simeon is delegitimized together with Levi, the third-born. Therefore, it is no wonder that in Gen 48:5-6 both Reuben and Simeon lose their positions at the head of the family line.

Surprisingly, in Gen 49:5-7 Simeon and Levi are delegitimized together:

Simeon and Levi are brothers; weapons of violence are their swords. May I never come into their council; may I not be joined to their company - for in their anger they killed men, and at their whim they hamstrung oxen. Cursed be their anger, for it is fierce, and their wrath, for it is cruel! I will divide them in Jacob, and scatter them in Israel (Gen 49:5-7 NRSV).

This raises the question of why the third-born is delegitimized as well. The curse on the two tribes particularly points to what later befalls the tribe of Levi, but not Simeon, when the promise of land is finally realized under the royalty of the house of Joseph. The Levites do not get an inheritance; rather, they are scattered among the other tribes through the allocation of cities among the other tribes. The delegitimization of Simeon and Levi seems to be linked with their violent action of revenge with the sword on Hamor and his son Shechem for the rape of Dinah.28 The name Shechem, however, is also associated with the name of a place, the place that Abraham passed through when he entered the land of promise (Gen 12:6) and the place where Jacob implored his people to give up other gods. This location also becomes a sacred place of covenant renewal under Joshua's leadership in Josh 24, and again the center of government for the Northern Kingdom under Jeroboam (1 Kgs 12:25).

The delegitimization of the other tribes, however, does not entirely explain how Joseph ended up having a dual allotment at the expense of the tribe of Levi instead of either Reuben or Simeon.

E POSSIBLE ATROCITY ON THE TRIBE OF LEVI

The delegitimization of the tribe of Levi from royalty in my view arose from the need to silence the tradition of Levi as the first royal tribe. The Moses story as contained in Exodus and Leviticus regards the tribe of Levi as the first royal tribe through the figure of Moses. However, in the surprising move that is contained in Numbers and Deuteronomy, Moses hands the royal baton to Joshua, an Ephra-imite. But did Moses wilfully hand over the royal baton to the tribe of Joseph?

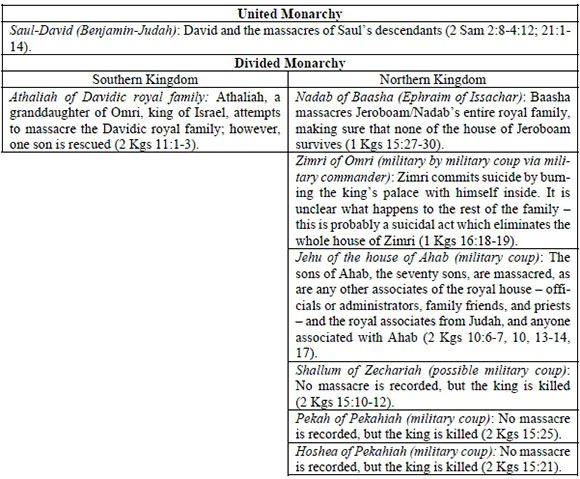

The transfer of the royal baton from the tribe of Levi or from the house of Moses, if the story is read along the grain, was a peaceful transition. However, this is questionable, especially considering the violent royal transitions which were common during the monarchic period and in the ANE context. When royal power shifted from one house or one tribe to another, it was often accompanied by the massacre of the house of whoever had formerly held the royal position.

This was done to ensure that the patrilineal royal inheritance was completely encapsulated within the new house. The biblical cases in the table highlight this.

Transitions from one house or tribe to another, as can be observed from the table, were accompanied by massacre. There are reasonable pointers in the text of the Hexateuch towards this direction with regard to the shift of power from Levi to Joseph (Moses to Joshua). The evidence lies in the numbers, and the book of Numbers provides us with further clues.

The Josephites' demand for more than one allotment implied that another tribe would have to be excluded from its inheritance. However, it was on the basis of their numbers that the tribe of Joseph was making its claim.

The sons of Joseph spoke as follows to Joshua, "Why have you given me only one share, only one portion, as heritage, when I am a numerous people

since Yahweh has so blessed me?". . . Joshua said to the House of Joseph, to Ephraim and to Manasseh, "You are a numerous people

and your strength is great; you will not only have one share

(Josh 17:14, 17, emphasis added).

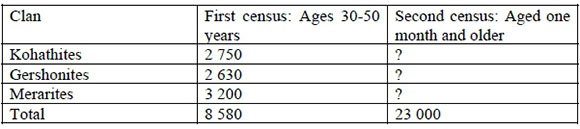

The book of Joshua does not provide the numbers, instead, they are provided in the book of Numbers, where the Levites are excluded from the military census on the basis of the cultic justification and are replaced by the Josephites. The Levites are excluded from military census, yet they are counted in both the first and the second census, and their numbers tell a story.

In the Moses story, as told in Exodus and Leviticus, there is no hint whatsoever that the tribe of Levi was a somewhat small tribe compared to the rest of the tribes. Furthermore, the militaristic ability of the tribe of Levi is heightened in Exod 32 during the incident of the golden calf, when the men of Levi went on a killing spree against fellow Israelites, killing about three thousand people. However, in the book of Numbers, a somewhat different picture of the tribe of Levi is portrayed.

In the first census, the Levites counted were only those from the age of thirty to the age of fifty - those who could serve in the tabernacle, and the total number given is 8 580. In the second census, the Levites are counted again; however, this time they are counted from one month old without a cut-off age, and their total number amounts to 23 000.

The total number of Levites in both censuses is amazingly low. If some historical reality does lie behind this low number of Levites, there is a likelihood that something could have happened when the Joseph tribes took over power, which was likely through force, possibly resulting in the massacre of the Levites. The low numbers of Levites as recorded in the two censuses probably reflect the survivors of the massacre. This may be the case, considering that not all royal massacres successfully wiped out all those within the royal family. Some instances of royal massacres were marked by the possibility of someone surviving or others surviving. For example, Jotham survived in the massacre of Gid-eon/Jerubbaal's seventy sons (Judg 9:5), Haddad survived in the massacre of the Edomite royal house (1 Kgs 11:14-17; 2 Sam 8:13-14), and Mephibosheth survived the massacre of Saul's descendants (2 Sam 4:4; 21:3-9).

Considering that it was probable for one or some within the royal family to survive a massacre, it also likely that the low number of Levites was the result of some of them surviving from within what was then Israel's royal tribe. The idea of a peaceful royal transition as projected in the Hexateuch from the tribe of Levi to the tribe of Joseph seems highly unlikely. The extent to which the text goes to legitimize the royalty of the Joseph tribes raises suspicion. As the Joseph tribe became the privileged one, the tribe of Levi became the marginalized other. Furthermore, in order prevent the Levite tribe from regrouping itself and so from threatening to regain power, they are dispersed and simply allotted cities to live in.

The royal usurpation brings to mind a Tshivenda proverb which says, Vhuhosi vhu tou bebelwa, (literally, "The royal throne, you are born for it"). This proverb is utilized especially in times of conflict when people are fighting to ascend the throne. In the Vhavenda culture, not anyone can be a king, only those born from within the royal line. While some may be appointed to act as king during times of crisis, the one who is set apart from birth to be the next king is the one with the right to the throne, because such a person is known from birth. In the royal household, not any wife of the king can give birth to the next king, but only the dzekiso wife, that is, she whose lumalo/lobola (bride price) is paid by the cattle that came into the family when the chief s sister was married.29However, conflicts often arise when others want to claim kingship which is not theirs. Ideally, the kingship is intended not to transition from one hut (tshitanga)30to another or from one family to another, or from one clan to another clan, but only within the particular family, and through a particular wife who can bear the next king. While some may forcefully claim the kingship and may want to establish their family line, such an act is regarded as a violation of the processes of kingship. While kingship in ancient Israel developed in different ways and often took many twists and turns, what is clear is that when the kingship transitioned from one family to another or from one tribe to another, it was usually accompanied by violence which was intended to completely break the previous royal family so that it would not have a chance to reclaim royalty.

The cultic justification for the Levites' exclusion from the land allotment that we find in Numbers-Deuteronomy-Joshua notwithstanding, the landlessness of the Levites should also be viewed from the perspective of royal transition. It is the transition of royalty from the tribe of Levi to the tribe of Joseph that likely underlies the landlessness of the Levites. Through the royal transition, the Joseph tribe became the privileged other through the exclusion of the Levites from land allotment, thereby rendering them landless, which in turn implied that they belonged to the marginalized of society - the aliens, the fatherless, and the widows (Deut 14:29; 16:11, 14).

In the South African context, whiteness is the symbol for privilege, while blackness is a symbol of landlessness. The black or African - unlike the Levites who were excluded from allotment in a land that did not initially belong to them - had to face dispossession of land which was theirs in the first place. The land-lessness of the black or African in our context is not accidental, but a direct result of the colonial dispossession of land and the structures of colonialism that continued to shape the patterns of living through exclusionary economic structures. The land is a commodity for the rich and powerful to enjoy, whereas those at the margins of society have to live in squatter camps, shacks, and overpopulated areas with no basic services.

To be black is to live in continual resistance to becoming violent as inequality continues to grow. To be black is also to be patient long enough to reach a point of no return in which one cannot bear the landlessness anymore, and one no longer believes the lie that the land will be returned soon. To be black, furthermore, is to reach a point at which one says, Ri la rothe kana ra shela mavu ("We all share the meal or we pour dirt"). To be black is thus to live at the verge of doing the unthinkable; that is, to burn and destroy property that is meant to serve you due to the frustration of seeing mapfene mahulwane a tshi khou la a sa fhedzi ngeno manwe mapfene a tshi khou fa nga ndala ("the big baboons continually eating while the rest of the baboons are starving to death").

The words of freedom song Thina Sizwe ("We, the Nation"), which is a struggle song, still continues to hold truth even in the current realities of the postapartheid, post-colonial era:

Thina sizwe, esimnyama (We the nation, the black nation)

Sikhalela izwe lethu (We cry for our land)

Elthathwa ngamabhulu (Which was taken by the whites)

Mabawuyeke umhlaba wethu (They must leave our land alone)

Abantwana b'eAfrika (Children of Africa)

Bakhalela izwe lethu (They cry for their land)

Elathathwa ngamabhulu (Which was taken by the whites)

Mabawuyeke umhlaba wethu (They must leave our land alone)

For the previously colonized, to use Fanon's words, "the most essential value, because it is the most concrete, is first and foremost the land; the land that will bring them bread and, above all dignity." Similarly, the Levites, although excluded from the land allotment, in requesting land, were seeking that which would bring them bread and, above all, dignity.

F CONCLUSION

From the perspective of those who find themselves on the underside of social matrix of power, and whose lives are characterized by damnation and landless-ness, the power dynamics projected by the text of the exclusion of the Levites from the land allotment cannot be ignored. The exclusion of the Levites from the land was a result of political conflict. It is not uncommon in biblical literature for horrendous acts to be provided with cultic justification. The fact that there is so much biblical material within the Hexateuch that attempts to provide cultic justification for the Levites' exclusion from the land allotment possibly speaks to the magnitude of the horrendous act, which the Joseph story, and also the books of Numbers, Deuteronomy, and Joshua attempt to cover up.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative. New York: Basic Books, 1981. [ Links ]

Albertz, Rainer. "The Canonical Alignment of the Book of Joshua." Pages 287-303 in Judah and Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Edited by Oded Lipschits, Gary N. Knoppers, and Rainer Albertz. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007. [ Links ]

Amit, Yairah. "Narrative Analysis: Meaning, Context, and Origins of Genesis 38." Pages 271-292 in Method Matters: Essays on the Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of David L. Petersen. Edited by Joel M. LeMon and Kent H. Richards. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009. [ Links ]

Baden, Joel S. "Violent Origins of the Levites: Text and Tradition." Pages 103-116 in Levites and Priests in Biblical History and Tradition. Edited by Mark Leuchter and Jeremy M. Hutton. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011. [ Links ]

Beetham, David. Legitimation of Power. London: Macmillan, 1991. [ Links ]

______. "Max Weber and the Legitimacy of the Modern State." A&K 13 (1991): 34-45. [ Links ]

Boorer, Suzanne. The Promise of the Land as Oath: A Key to the Formation of the Pentateuch. BZAW 205. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1992. [ Links ]

Carr, David M. Reading the Fractures of Genesis: Historical Literary Approaches. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Coats, George. From Canaan to Egypt: Structural and Theological Context for the Joseph Story. CBQMS 4. Washington: Catholic Biblical Association, 1976. [ Links ]

Cook, Stephen L. "Those Stubborn Levites: Overcoming Levitical Disenfranchisement." Pages 155-170 in Levites and Priests in Biblical History and Tradition. Edited by Mark Leuchter and Jeremy M. Hutton. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011. [ Links ]

Crüsemann, Frank. Der Widerstand gegen das Köningtum; die antiköniglichen Texte des Alten Testaments und der Kampt um de frühen israelitischen Staat. WMANT 49. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978. [ Links ]

Dozeman, Thomas B. Joshua 1-12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. AYB. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Farber, Zev. Images of Joshua in the Bible and their Reception. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2016. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, Ramón. "Epistemic Decolonial Turn." CSt 21/2-3 (2007): 211-223. Doi: 10.1080/0950238061162514. [ Links ]

Habel, Norman C. Six Biblical Land Ideologies. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Hepner, Gershon. Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel. New York: Peter Lang, 2010. [ Links ]

Hirsch, Samson R. Genesis. Vol. 1 of The Pentateuch Translated and Explained. Translated by Esaac Levey. 2nd ed. New York: Bloch Publishing Co., 1963. [ Links ]

Humphreys, W. Lee. "A Life-Style for Diaspora: A Study of the Tales of Esther and Daniel." JBL 92 (1973): 211-223. [ Links ]

Japhet, Sara. "Conquest and Settlement in Chronicles." JBL 98/2 (1979): 205-218. [ Links ]

Knight, Douglas A. "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomist." Pages 31-46 in Old Testament Interpretation: Past, Present and Future-Essays in Honor of Gene M. Tucker. Nashville: Abingdon, 1995. [ Links ]

Mathews, Kenneth A. Genesis 11:27-50:26: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2005. [ Links ]

Matshidze, Pfarelo E. "The Role of Makhadzi in Traditional Leadership among the Venda." PhD diss., University of Zululand, 2013. [ Links ]

Meinhold, Arndt. "Die Diaspora-novell - eine alttestamentlich Gattung." PhD diss., Universität Greifswald, 1971. [ Links ]

______. "Die Gattung der Josephgeschichte und des Estherbuches: Diasporanovelle." ZAW 87 (1975): 306-342. [ Links ]

Morgan, Donn. Wisdom in the Old Testament Traditions. Atlanta: John Knox, 1981. [ Links ]

Nahkola, Aulikki. Double Narratives in the Old Testament: The Foundations of Method in Biblical Criticism. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2001. [ Links ]

Noth, Martin. The Deuterononomistic History. JSOTSup 15. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1981. [ Links ]

Oeste, Gordon K. Legitimacy, Illegitimacy, and the Right to Rule: Windows on Abimelech 's Rise and Demise in Judges 9. New York: T&T Clark, 2011. [ Links ]

O'Connell, Robert H. The Rhetoric of the Book of Judges. VTSup 63. Leiden: Brill, 1996. [ Links ]

Pressler, Carolyn. Joshua, Judges, and Ruth. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002. [ Links ]

Quijano, Aníbal. "Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality." CSt 21/2-3 (2007): 168-178. Doi, 10.1080/09502380601164353. [ Links ]

Ramantswana, Hulisani. "Beware of the (Westernised) African eyes: Rereading Psalm 82 through the vhufa approach," Scriptura 116/1 (2017). Online: http://scriptura.iournals.ac.za/pub/article/view/1205. [ Links ]

Redford, Donald. "The 'Land of the Hebrews' in Gen 40:15." VT 15 (1965): 529-532. [ Links ]

______. A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph, Genesis 37-50. VTSup 20. Leiden: Brill, 1970. [ Links ]

Sarna, Nahum M. Understanding Genesis. New York: McGraw Hill, 1966. [ Links ]

Sternberg, Meier. Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Van Seters, John. "The So-Called Deuteronomistic Redaction in the Pentateuch." Pages 58-76 in Congress Volume: Leuven. VTSup 43. Edited by John A. Emerton. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1989. [ Links ]

Vervenne, Marc. "The Question of Deuteronomic Elements in Genesis to Numbers." Pages 243-268 in Studies in Deuteronomy in Honour of C. J. Labuschagne on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994. [ Links ]

Von Rad, Gerhard. "The Joseph Narrative and Ancient Wisdom." Pages 292-300 in Problems of the Hexateuch and Other Essays. Translated by Trueman Dicken. New York: McGraw Hill, 1966. [ Links ]

______. "The Form-Critical Problem of the Hexateuch." Pages 1-78 in Problems of the Hexateuch and Other Essays. Translated by Trueman Dicken. New York: McGraw Hill, 1966. [ Links ]

Warning, Wilfried. "Terminological Patterns and Genesis 38." AUSS 38 (2000): 293-305. [ Links ]

Weber, Max. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. 2 vols. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Translated by Ephraim Fischoff, et al. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Genesis 37-50: A Commentary. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1986. [ Links ]

Whybray, Norman. The Making of the Pentateuch: A Methodological Study. JSOTSup 53. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Wildavsky, Aaron. Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel. New Brunswick: Transaction, 1993. [ Links ]

Woudstra, Marten H. The Book of Joshua. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981. [ Links ]

Wünch, Hans-Georg. "Genesis 38 - Judah's Turning Point: Structural Analysis and Narrative Techniques and their Meaning for Genesis 38 and Its Placement in the Story of Joseph." OTE 25/3 (2012): 777-806. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 17/02/2017

Peer-reviewed 17/03/2017

Accepted: 3/04/2017

Dr. Hulisani Ramantswana, University of South Africa, Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, P. O. Box 392, UNISA, 0003. E-mail: ramanh@unisa.ac.za or hramantswana@hotmail.com.

1 Aníbal Quijano, "Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality," CSt 21/2-3 (2007): 168178, 171, doi: 10.1080/09502380601164353; Ramón Grosfoguel, "Epistemic Decolo-nial Turn," CSt 21/2-3 (2007): 211-223, doi: 10.1080/0950238061162514.

2 Meier Sternberg, Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985); Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 1981).

3 Sternberg, Poetics, 265-368; Alter, Art, 47-87.

4 See Norman Whybray, The Making of the Pentateuch: A Methodological Study, JSOTSup 53 (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1987), 80-85; Aulikki Nahkola, Double Narratives in the Old Testament: The Foundations of Method in Biblical Criticism (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2001).

5 For more information on vhufa approach see Hulisani Ramantswana, "Beware of the (Westernised) African eyes: Rereading Psalm 82 through the vhufa approach," Scriptura 116/1 (2017). Online: http://scriptura.iournals.ac.za/pub/article/view/1205. Access Date 15 Nov. 17

6 Gordon K. Oeste, Legitimacy, Illegitimacy, and the Right to Rule: Windows on Abimelech's Rise and Demise in Judges 9 (New York: T&T Clark, 2011), 199.

7 Martin Noth regards Deuteronomy through Kings as a self-contained unit with a distinctive style and structure. For Noth the Jahwist-Elohist-Priestly sources (JEP) were contained in the Tetrateuch. See Martin Noth, The Deuterononomistic History, JSOTSup 15 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1981). Von Rad, on the other hand, maintained the notion of the Hexateuch. See Gerhard von Rad, "The Form-Critical Problem of the Hexateuch," in The Problem of the Hexateuch and Other Essays (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1966), 1-78. Thus, some scholars see the Pentateuchal source JEP continuing into the book of Joshua, whereas others tend to see Deuteronomic elements in the Tetrateuch. For discussion on these issues see Thomas B. Dozeman, Joshua 1-12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AYB (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 6-7; John Van Seters, "The So-Called Deuteron-omistic Redaction in the Pentateuch," in Congress Volume: Leuven, VTSup 43, ed. John A. Emerton (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1989), 58-76; Marc Vervenne, "The Question of Deu-teronomic Elements in Genesis to Numbers" in Studies in Deuteronomy in Honour of C. J. Labuschagne on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994), 243-268; Douglas A. Knight, "Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomist," in Old Testament Interpretation: Past, Present and Future -Essays in Honor of Gene M. Tucker (Nashville: Abingdon, 1995), 31-46; Suzanne Boorer, The Promise of the Land as Oath: A Key to the Formation of the Pentateuch, BZAW 205 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1992).

8 Norman C. Habel, Six Biblical Land Ideologies (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995), 47-50.

9 David Beetham, Legitimation of Power (London: Macmillan, 1991), 57.

10 Beetham, Legitimation, 106-107.

11 Marten H. Woudstra, The Book of Joshua (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981), 256.

12 Scholars generally consider Joshua to have been a local leader of Josephite tribes, whose traditions were merged with the traditions of the other tribes. With regard to Josh 14:14-18, Farber, following Rofé, argues that "the biblical text presents an Israelite people who are outside the Promised Land, coming in to conquer it by way of the Jordan River, and conquering areas east of the Jordan on the way. This story, in contrast, presents a Josephite people settling the Cisjordan, but unable to conquer all of it and, therefore, spreading out into the Transiordanian Bashan area due to overpopulation. Although it explains the same phenomenon - related tribes on both sides of the river - it works with very different premises." See Zev Farber, Images of Joshua in the Bible and Their Reception (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2016), 122-123. Farber further argues that Josh 14:14-18 does not really indicate the origin of the Josephites, but describes their settlement in the forested land with the future hope for them to conquer the plains as well (Farber, Images of Joshua, 104-105). The view that the Josephite people did not originate from outside is also confirmed by 1 Chr 7:20-28. Japhet argues that 1 Chr 7:20-28 "is based on certain historical assumptions and offers some historical data. The primary assumption is that Ephraim is living 'in the land.' . . . The same independent concept of history, with apparent polemical overtones, is found in the pedigree of Joshua. . . . The direct line from Ephraim, who is living and functioning in the land, to Joshua ties Joshua to the land as well, and the consequences of that bond cannot be exaggerated." See Sara Japhet, "Conquest and Settlement in Chronicles," JBL 98/2 (1979): 205-218, 213-215.

13 Carolyn Pressler, Joshua, Judges, and Ruth (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 104.

14 Rainer Albertz, "The Canonical Alignment of the Book of Joshua," in Judah and Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E., ed. Oded Lipschits, Gary N. Knoppers, and

Rainer Albertz (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007), 287-303, 298.

15 See also Woudstra, Joshua, 226.

16 Recently, Farber has argued that Joshua was "the founder of a proto-monarch or a founding leader of Israel and Judah." He further argues, "As Israelite-Judahite mnemo-history developed, the story of the conquest of the Cisjordan under Joshua met with the story of the Exodus from Egypt and the wandering in the wilderness under Moses. Since virtually all of ritual YHWH-focused practice was being attributed to Moses the lawgiver, the Joshua tradition would have had little choice but to fit itself into the rubric of the Moses story" (Farber, Images of Joshua, 122-123).

17 I follow in this regard David M. Carr, Reading the Fractures of Genesis: Historical Literary Approaches (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), 277-280; Frank Crüsemann, Der Widerstand gegen das Köningtum; die antiköniglichen Texte des Alten Testaments und der Kampt um de frühen israelitischen Staat, WMANT 49 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978) 143-155.

18 I am indebted here to Carr, Reading the Fractures, 226.

19 Gerhard von Rad, "The Joseph Narrative and Ancient Wisdom," in Problems of the Hexateuch and Other Essays, trans. Trueman Dicken (New York: McGraw Hill, 1966), 292-300; George Coats, From Canaan to Egypt: Structural and Theological Context for the Joseph Story, CBQMS 4 (Washington: Catholic Biblical Association, 1976), 7879; Donn Morgan, Wisdom in the Old Testament Traditions (Atlanta: John Knox, 1981), 49-50; Claus Westermann, Genesis 37-50: A Commentary (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1986), 24-25;

20 Donald Redford, "The 'Land of the Hebrews' in Gen 40:15," VT 15 (1965): 529532; Donald Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph, Genesis 37-50, VTSup 20 (Leiden: Brill, 1970), 27-65, 187-25. Dating the story to the Egyptian Saite era (650425) are Arndt Meinhold, "Die Diaspora-novell - eine alttestamentlich Gattung" (PhD diss., Universität Greifswald, 1971), 22-51; Arndt Meinhold, "Die Gattung der Josephgeschichte und des Estherbuches: Diasporanovelle," ZAW 87 (1975): 306-342; W. Lee Humphreys, "A Life-Style for Diaspora: A Study of the Tales of Esther and Daniel," JBL 92 (1973): 211-223. Some of those who date the story in the post-exilic period, which was responding to the exclusionary tendencies of Ezra-Nehemiah, see Gershon Hepner, Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), 617-635.

21 David Beetham, "Max Weber and the Legitimacy of the Modern State," A&K 13 (1991): 34-45, 35.

22 Mathews writes, " ... presumably, the final narrative (Jacob-Joseph in Egypt, chaps. 37-40) reflects the setting for the latest compositional stage. According to critical assessments, the struggle for legitimacy as to who will rule over Israel, that is, the Joseph tribes or the Judah tribe." See Kenneth A. Mathews, Genesis 11:27-50:26: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (Nashville: Broadman & Hol-man Publishers, 2005), 88. Robert H. O'Connell, The Rhetoric of the Book of Judges, VTSup 63 (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 292, 299.

23 Redford, Biblical Story of Joseph, 16-17; Hans-Georg Wünch, "Genesis 38 -Judah's Turning Point: Structural Analysis and Narrative Techniques and their Meaning for Genesis 38 and Its Placement in the Story of Joseph," OTE 25/3 (2012): 777806; Wilfried Warning, "Terminological Patterns and Genesis 38," AUSS 38 (2000): 293-305; Amit also notes that "The book of Ruth also refers by name to the story of Judah and Tamar (4:12). One may therefore assume that the story of Judah and Tamar was the ideological and poetical basis for the book of Ruth." See Yairah Amit, "Narrative Analysis: Meaning, Context, and Origins of Genesis 38," in Method Matters: Essays on the Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of David L. Petersen, ed. Joel M. LeMon and Kent H. Richards (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009), 271292, 285.

24 Nahum M. Sarna, Understanding Genesis (New York: McGraw Hill, 1966), 212; Aaron Wildavsky, Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1993), 75.

25 Other examples in the OT are David over his brothers, Solomon over Adonijah. See

Wildavsky, Assimilation, 72-73.

26 Wildavsky, Assimilation, 73; Samson R. Hirsch, Genesis, vol. 1 of The Pentateuch Translated and Explained, trans. Esaac Levey, 2nd ed. (New York: Bloch Publishing Co., 1963), 550.

27 Max Weber, Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, ed. Guen-ther Roth and Claus Wittich, trans. Ephraim Fischoff, et al., vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California, 1978), 953.

28 Stephen L. Cook, "Those Stubborn Levites: Overcoming Levitical Disenfranchise-ment," in Levites and Priests in Biblical History and Tradition, ed. Mark Leuchter and Jeremy M. Hutton (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 155-170; Joel S. Baden, "Violent Origins of the Levites: Text and Tradition," in Levites and Priests in Biblical History and Tradition, ed. Mark Leuchter and Jeremy M. Hutton (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 103-116.

29 Pfarelo E. Matshidze, "The Role of Makhadzi in Traditional Leadership among the Venda" (PhD diss., University of Zululand, 2013), 152.

30 Because kings usually marry many wives, each wife who is married establishes her own tshitanga (hut), which in turn implies her own family line. Therefore, it will be known from marriage and from birth as to which tshitanga the next in line would come from, because only the wife who is married through the cattle of makhadzi (the king's sister) can give birth to the next king.