Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 no.3 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n3a8

ARTICLES

Creation rest: Genesis 2:1-3 and the first creation account

Matthew Haynes; P. Paul Krüger

North-West University

ABSTRACT

In this article, the nature of God's rest in the first creation account is examined by describing what "rest" entailed for God. It is suggested that God's notion "rest" emerges from the creational activity of the first six days, that it continues into the present time, and that it serves as a counterpoint to the notions of rest presented by other cultures of the ANE. It is also argued that, while God rested on the seventh day, humanity was busy with its appointed tasks of subduing the earth, exercising dominion, and expanding the borders of the garden as they multiply and fill the earth.

Keywords: Rest; Creation; First Creation Account; Image of God

A INTRODUCTION

This article attempts to define more clearly the nature of God's notion of rest on the seventh day of creation. Additionally, the shape of humanity's task and relationship with God during his rest are examined. The article addresses these issues in two ways. Firstly, God's rest in the first creation account is examined, including an overview of the concepts of rest in the ANE and in Israel. Secondly, the function of humanity in the first creation account is considered. The mandates given to humanity are emphasized along with the overarching situation as it stood as YHWH entered his rest on the seventh day. The conclusion describes the overall situation in Eden during the seventh day.

B GOD'S REST IN THE FIRST CREATION ACCOUNT

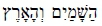

The seventh day of creation and the close of the first creation account are described in Gen 2:1-3:1

1Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. 2And on the seventh day God finished his work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work that he had done. 3 So God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it God rested from all his work that he had done in creation.

Genesis 2:1-3 serves as a conclusion to the first creation account. The first verse acts as a summary statement to the account of the creative activity that God accomplishes in Gen 1:1-31, while 2:2-3 describes the rest that is the result of that completed activity.2

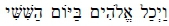

In contrast to the first six days, which are filled with creative activity, the seventh day is marked by its absence. This transition is made distinct in the Hebrew text of 2:1 by the wayyiqtol, marking it as the introduction to a concluding statement.3 Used 206 times in the HB, means, intransitively (in the qal), "be complete, be finished, be destroyed, be consumed, be weak, be deter -mined."4 Similarly, in the piel it carries the transitive nuance of "complete" or "end." The pual form, as used here, carries a similar, passive sense: 'be finished," 'be ended," or be completed."5 The LXX renders it with συνετελέσθησαν, which also means "to finish off or "to be accomplished."6This notion of "completing" or "finishing" can be understood in one of two senses: firstly, various pieces are continually added together until fullness is achieved and an activity is stopped. For example, one can pour water into a glass until it is full. When the glass is full (i.e., fullness is achieved), one ceases to pour because the intent to fill the glass with water has been completed. The second sense involves the removal of parts from a whole until nothing remains. To return to the example of the glass of water: a glass of water can be emptied by drinking from it. One ceases to drink from the glass when there is nothing left in it. Completion of intent is the trigger for cessation in both cases. This suggests that the sense of

means, intransitively (in the qal), "be complete, be finished, be destroyed, be consumed, be weak, be deter -mined."4 Similarly, in the piel it carries the transitive nuance of "complete" or "end." The pual form, as used here, carries a similar, passive sense: 'be finished," 'be ended," or be completed."5 The LXX renders it with συνετελέσθησαν, which also means "to finish off or "to be accomplished."6This notion of "completing" or "finishing" can be understood in one of two senses: firstly, various pieces are continually added together until fullness is achieved and an activity is stopped. For example, one can pour water into a glass until it is full. When the glass is full (i.e., fullness is achieved), one ceases to pour because the intent to fill the glass with water has been completed. The second sense involves the removal of parts from a whole until nothing remains. To return to the example of the glass of water: a glass of water can be emptied by drinking from it. One ceases to drink from the glass when there is nothing left in it. Completion of intent is the trigger for cessation in both cases. This suggests that the sense of  should not be restricted to the simple cessation of activity; it should also be bound to the completion of intent.7 Genesis 2:1 reflects the first sense of

should not be restricted to the simple cessation of activity; it should also be bound to the completion of intent.7 Genesis 2:1 reflects the first sense of  . The realm of embodied existence has been completed, and everything placed in that realm has filled it up - not in the sense of an exhaustion of space, but rather that everything God intended to create has been created. His creational intent has been fulfilled, and he therefore stops creating new things. Coupled with the use of the wayyiqtol form mentioned above, rfo indicates that this verse (a) draws to a conclusion the creative acts of God described so far and (b) serves as a transition to vv. 2-3, which more fully describe the resultant state of affairs at the close of the first creation account.

. The realm of embodied existence has been completed, and everything placed in that realm has filled it up - not in the sense of an exhaustion of space, but rather that everything God intended to create has been created. His creational intent has been fulfilled, and he therefore stops creating new things. Coupled with the use of the wayyiqtol form mentioned above, rfo indicates that this verse (a) draws to a conclusion the creative acts of God described so far and (b) serves as a transition to vv. 2-3, which more fully describe the resultant state of affairs at the close of the first creation account.

The second half of the verse tells us what has been completed: "The heavens and the earth and all their multitude." The waw serves to join  and

and  in a nominal hendiadys. Together they describe the overall environment in which the other creatures carry out their existence. It is the same construction found in Gen 1:1; its use here echoes the same concept and serves as an inclusio. 'The heavens and the earth" do es not simply refer to the sky (created on the second day) and the earth (created on the third day) - the point is not to describe specific aspects of the environment; it is a shorthand for the cosmic environment.8

in a nominal hendiadys. Together they describe the overall environment in which the other creatures carry out their existence. It is the same construction found in Gen 1:1; its use here echoes the same concept and serves as an inclusio. 'The heavens and the earth" do es not simply refer to the sky (created on the second day) and the earth (created on the third day) - the point is not to describe specific aspects of the environment; it is a shorthand for the cosmic environment.8

In addition to the cosmic environment, the things that fill the environment have been completed.9 Syntactically, the use of the 3mp suffix ("their") in  refers to

refers to  as its antecedent. Here,

as its antecedent. Here,  describes the "host" of creation,10 or the "multitude" that filled the created order. Put in another way, it is a descriptor for all of created things residing in "the heavens and the earth11 The noun phrase in which it is found

describes the "host" of creation,10 or the "multitude" that filled the created order. Put in another way, it is a descriptor for all of created things residing in "the heavens and the earth11 The noun phrase in which it is found  begins with a waw that coordinates the two aspects of creation: the environment of the created order and the material substance inhabiting that environment. What exactly, then, has been completed? The entire actualized order - both the environment and the things that fill it. One short verse summarizes the creative activity of Gen 1 and lays the foundation for the uniqueness of the seventh day.

begins with a waw that coordinates the two aspects of creation: the environment of the created order and the material substance inhabiting that environment. What exactly, then, has been completed? The entire actualized order - both the environment and the things that fill it. One short verse summarizes the creative activity of Gen 1 and lays the foundation for the uniqueness of the seventh day.

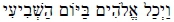

A textual variant of Gen 2:2 reads  ("and God finished on the sixth day") rather than

("and God finished on the sixth day") rather than  ("and God finished on the seventh day"). The Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac, and the LXX support the alternate reading. The most plausible reason for this emendation is a desire to present God as engaged in nothing but rest on the seventh day.12 The implication is that if God does anything on the seventh day, then it is not properly a day of rest. The emendation, however, is not necessary. Several alternative possibilities present themselves: firstly, it is possible to translate with a pluperfect: "And God had finished on the seventh day ..." Completed action is signified by the same verb, which is also used in Gen 17:22, 49:33, and Exod 40:33; a similar situation can be understood here.13 Secondly, the verbs in 2:1-3 denote mental activity: "were finished" (2:1), "finished," "rest -ed" (2:2), ""blessed," and "made holy" (3:3). This is not the same kind of creative activity that marks the first six days (e.g., "making" and "creating"). Far from being actions of work, they are activities of "enjoyment, approval, and delight."14 Thirdly, the statement may be a declarative. Chapter 1 has already seen God declare various aspects of his work "good" and "very good." Now, as he inspects the completed product of his handiwork, he decides that it is complete.15

("and God finished on the seventh day"). The Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac, and the LXX support the alternate reading. The most plausible reason for this emendation is a desire to present God as engaged in nothing but rest on the seventh day.12 The implication is that if God does anything on the seventh day, then it is not properly a day of rest. The emendation, however, is not necessary. Several alternative possibilities present themselves: firstly, it is possible to translate with a pluperfect: "And God had finished on the seventh day ..." Completed action is signified by the same verb, which is also used in Gen 17:22, 49:33, and Exod 40:33; a similar situation can be understood here.13 Secondly, the verbs in 2:1-3 denote mental activity: "were finished" (2:1), "finished," "rest -ed" (2:2), ""blessed," and "made holy" (3:3). This is not the same kind of creative activity that marks the first six days (e.g., "making" and "creating"). Far from being actions of work, they are activities of "enjoyment, approval, and delight."14 Thirdly, the statement may be a declarative. Chapter 1 has already seen God declare various aspects of his work "good" and "very good." Now, as he inspects the completed product of his handiwork, he decides that it is complete.15

Generally, English translations render mtl? as "rest."16 There are, however, other possible meanings. Hamilton describes its "basic thrust" as "to sever, put an end to" when it is transitive and "to desist, come to an end" when it is intransitive.17 He argues that "rest," as it is commonly understood, is implied only when it is used in the qal in a "Sabbath context" (13 of 27 occurrences). Hamilton is not alone in espousing this view.18 While this may be true, it still leaves us with an unanswered question: if the meaning of  in this context is 'to cease' or 'to end,' then what kind of 'rest' is intended here? In other words, how does the "rest" described in a "Sabbath context" relate to the "basic thrust" of the verb? An analysis of the biblical usage of the word is helpful. If examples of can be found that mean something other than to "cease" or "come to an end," then the nuance of "rest" described in Sabbath contexts would lack clarity. However, if all of the biblical uses outside of "Sabbath" contexts have the idea of cessation as a common denominator, then it should bring some clarity to its use in a Sabbath context. And indeed, the idea of cessation is exactly what we find throughout.

in this context is 'to cease' or 'to end,' then what kind of 'rest' is intended here? In other words, how does the "rest" described in a "Sabbath context" relate to the "basic thrust" of the verb? An analysis of the biblical usage of the word is helpful. If examples of can be found that mean something other than to "cease" or "come to an end," then the nuance of "rest" described in Sabbath contexts would lack clarity. However, if all of the biblical uses outside of "Sabbath" contexts have the idea of cessation as a common denominator, then it should bring some clarity to its use in a Sabbath context. And indeed, the idea of cessation is exactly what we find throughout.

In some incidences is used with the clear idea of cessation. Joshua 5:12 is typical of these. When the Israelites enter the Promised Land, we read, "And the manna ceased the day after they ate the produce of the Land." Simi -larly, other passages use  in the hiphil with God as the subject. Ezekiel 12:23 depicts YHWH taking action in response to a proverb that has become popular amongst the exiles: "Tell them therefore, 'Thus says the Lord GOD: I will put an end to this proverb, and they shall no more use it as a proverb in Israel.'" Other passages using do not make the notion of cessation explicit, yet the idea underlies the thought nonetheless. When Josiah reforms temple worship after finding the book of the covenant, we find that "... he deposed the priests whom the kings of Judah had ordained to make offerings in the high places at the cities of Judah ..." (2 Kgs 23:5). The underlying idea is that the priests who were leading the people astray were forced to cease their ministry.

in the hiphil with God as the subject. Ezekiel 12:23 depicts YHWH taking action in response to a proverb that has become popular amongst the exiles: "Tell them therefore, 'Thus says the Lord GOD: I will put an end to this proverb, and they shall no more use it as a proverb in Israel.'" Other passages using do not make the notion of cessation explicit, yet the idea underlies the thought nonetheless. When Josiah reforms temple worship after finding the book of the covenant, we find that "... he deposed the priests whom the kings of Judah had ordained to make offerings in the high places at the cities of Judah ..." (2 Kgs 23:5). The underlying idea is that the priests who were leading the people astray were forced to cease their ministry.

The overall usage of  makes a number of things clear. Firstly, as many commentators note, the primary idea behind

makes a number of things clear. Firstly, as many commentators note, the primary idea behind  is to "cease" or "put an end to."19 Secondly, the notion of "e an activity has been stopped. More importantly, the rest obtained is not rest in a general sense, as it might be commonly understood in twenty-first-century popular culture; it is not the absence of all activity for the purpose of leisure. It is rest frest" should not be divorced from the idea of "ceasing." Rest begins becausrom a particular activity previously engaged in. Finally, the use of

is to "cease" or "put an end to."19 Secondly, the notion of "e an activity has been stopped. More importantly, the rest obtained is not rest in a general sense, as it might be commonly understood in twenty-first-century popular culture; it is not the absence of all activity for the purpose of leisure. It is rest frest" should not be divorced from the idea of "ceasing." Rest begins becausrom a particular activity previously engaged in. Finally, the use of indicates that God did not rest because he was weary. He completed everything that he intended to create and was satisfied with the results. There was, therefore, no need to continue with the activity previously underway. The issue is one of completion, not weariness. Moreover, God did not cease all activity on the seventh day. His rule over creation and his involvement in the events of creation continue unabated.20

indicates that God did not rest because he was weary. He completed everything that he intended to create and was satisfied with the results. There was, therefore, no need to continue with the activity previously underway. The issue is one of completion, not weariness. Moreover, God did not cease all activity on the seventh day. His rule over creation and his involvement in the events of creation continue unabated.20

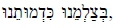

We have already examined one way in which the seventh day was differentiated from the other six days of the creation week: it is the day that God ceased his creative activity. There are, however, two other ways in which God marks this day as unique: (a) he blesses it  and (b) he sets it apart

and (b) he sets it apart  The two verbs describe the events that follow God's act of cessation. At the same time, they serve to describe the situation more fully as it stood after his creative activity was brought to an end.

The two verbs describe the events that follow God's act of cessation. At the same time, they serve to describe the situation more fully as it stood after his creative activity was brought to an end.

There are two aspects associated with blessing in this context. The first is a "statement of relationship" that is made by the one who blesses. The second is a description of the benefits conveyed with the blessing. When God blesses, he does so with an attendant benefit that marks the special relationship between him and the thing that is being blessed.21 When used in the piel (as in this verse), " can have "various shades of meaning."22 However, in the piel, it is used primarily with the meaning "to bless." In the context of the OT, with God as the subject, to bless means "to endue with power for success, prosperi -ty, fecundity, longevity, etc."23 or to "endue someone with special power."24The implication is that someone or something is blessed for the purpose of fulfilling a particular function. After seeing that the sea creatures and birds are "good," God blesses them (1:22) for the purpose of being fruitful and multiplying. Similarly, God blesses the man and woman in 1:28. Like the blessing of the fifth day, this blessing is also for the purpose of being fruitful and multiplying. However, there is another purpose to this blessing: humanity is expected to subdue the earth and exercise dominion over the other living creatures.25 In both instances, the blessing that is given is tied to the function that the one blessed is intended to perform, and both are statements of relationship between God and his creatures.26 By blessing the seventh day, God marks the unique relationship that he has with it by allowing it to function in a way that the other days did not. The first six days are days of labor; the seventh day is differentiated as God's unique rest day.

can have "various shades of meaning."22 However, in the piel, it is used primarily with the meaning "to bless." In the context of the OT, with God as the subject, to bless means "to endue with power for success, prosperi -ty, fecundity, longevity, etc."23 or to "endue someone with special power."24The implication is that someone or something is blessed for the purpose of fulfilling a particular function. After seeing that the sea creatures and birds are "good," God blesses them (1:22) for the purpose of being fruitful and multiplying. Similarly, God blesses the man and woman in 1:28. Like the blessing of the fifth day, this blessing is also for the purpose of being fruitful and multiplying. However, there is another purpose to this blessing: humanity is expected to subdue the earth and exercise dominion over the other living creatures.25 In both instances, the blessing that is given is tied to the function that the one blessed is intended to perform, and both are statements of relationship between God and his creatures.26 By blessing the seventh day, God marks the unique relationship that he has with it by allowing it to function in a way that the other days did not. The first six days are days of labor; the seventh day is differentiated as God's unique rest day.

In the piel  can mean to "consecrate," "set apart," or "declare holy."27 The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew goes so far as to say "make invio -lable" when God is the subject.28 In other words, when someone or something is consecrated or set apart, it is not simply a declaration with no practical implication.29 The underlying idea is positional or relational: a particular relationship is formed with the object of the verb.30 The consecrated object has been moved into the sphere of the divine and, consequently, can no longer belong to the sphere of the common or ordinary.31 In Exod 13:2, for example, we find: "Consecrate

can mean to "consecrate," "set apart," or "declare holy."27 The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew goes so far as to say "make invio -lable" when God is the subject.28 In other words, when someone or something is consecrated or set apart, it is not simply a declaration with no practical implication.29 The underlying idea is positional or relational: a particular relationship is formed with the object of the verb.30 The consecrated object has been moved into the sphere of the divine and, consequently, can no longer belong to the sphere of the common or ordinary.31 In Exod 13:2, for example, we find: "Consecrate  piel imperative] to me all the firstborn. Whatever is the first to open the womb among the people of Israel, both of man and of beast, is mine." The result of "consecration" is the formation of a unique rela -tionship between the firstborn and God. The firstborn of Israel belong to him in a relationship that is unique and not shared by the rest of the people of Israel. In Gen 2:3, God marks the seventh day as something that bears a unique relationship to himself and is therefore distinct from the days that have gone before. The day belongs to him as an exclusive possession. The reason why God formed this unique relationship with this particular time period is then explained in the latter half of the verse.

piel imperative] to me all the firstborn. Whatever is the first to open the womb among the people of Israel, both of man and of beast, is mine." The result of "consecration" is the formation of a unique rela -tionship between the firstborn and God. The firstborn of Israel belong to him in a relationship that is unique and not shared by the rest of the people of Israel. In Gen 2:3, God marks the seventh day as something that bears a unique relationship to himself and is therefore distinct from the days that have gone before. The day belongs to him as an exclusive possession. The reason why God formed this unique relationship with this particular time period is then explained in the latter half of the verse.

The twin concepts of blessing and consecration describe a day that uniquely belongs to God. While it is true that all days "belong" to him, this particular day is relationally set aside for his exclusive use. As such, it is a day that has been empowered by him to function as the space in which his rest can occur.

A number of conclusions concerning God's rest can be taken from this analysis. Firstly, both the creatures and the environment in which they carry out their existence had been completed by the close of the sixth day. Secondly, God created everything that he intended to create. Once his creational intention was fulfilled, he ceased creating. We can understand this cessation of work as "rest," as long as it is not abstracted from his work that was previously under -way. Furthermore, God's rest is not rest from all work, but rest from the particular work of creation. Finally, because God rested on the seventh day, he has set it apart as something that belongs uniquely to himself and has thus empowered it to function as the day on which his rest can occur.

1 Divine rest in the Ancient Near East and Israel

One of the most striking aspects of the first creation narrative is that the concluding refrain of the first six days is absent from the description of the seventh day. God's creative activities on days one through six conclude with "And there was evening and there was morning, the [nth] day" (Gen 1:5, 8, 13, 19, 23, 31). Its absence on the seventh day suggests that, while creation was completed, God's rest continues unabated.32 This is a notion not unique to Israel; similar ideas are found throughout the literature of the ANE where the deity's rest often follows creational activity.33

Westermann34 argues that the events of Gen 1-11 cannot be understood without reference to their placement within the whole of the Pentateuch. He contends that, within the structure of the Pentateuch, the exodus event (including the crossing of the Red Sea and the subsequent events at Sinai) stands as the defining moment of the story. As one looks back at the events that led up to the exodus, both the intermediate and ancient history of Israel can be seen: the patriarchal history of Gen 12-50 describes how Israel came to be a great people who find themselves in a foreign country. These chapters describe a story that is specific to Israel alone. Beyond that, however, Gen 1-11 casts a net that is much wider. It describes a situation that belongs not just to Israel, but to all of humanity.

As such, the placement of Gen 1-11 at the beginning of the larger narrative that includes the exodus achieves two things:

• It grounds Israel's experience in the experience of humanity as a whole. "The texts no longer speak to Israel in the context of the action of the primeval period on the present - there is no cultic actualization-but through the medium of history ... God's action, which Israel has experi-enced in its history, is extended to the whole of history and to the whole world."35 It should not be surprising, therefore, that elements that characterize the first creation account should find parallels in other traditions. The first creation account explains a history that is common to humanity and includes humanity in the storyline of Israel's experience of YHWH as redeemer.

• It grounds primeval history in the realm of actual history. With the transition from primeval history to the call of Abraham, the story asserts itself as something that stands apart from myth.36

In Westermann's conception, it is important to examine the various primeval motifs of Gen 1-11 in contexts wider than their own. They must be examined as they relate to other aspects of the primeval history. The theme of rest, for example, stands in relationship to the creation theme. It was not the J or P source that brought these themes together. They drew from traditions that were common at the time and tailored them to meet their specific needs. When a later redactor pieced the Pentateuch together, he kept the thematic relationships intact to form what we have now.37 Primeval events from three different realms thus overlap in Gen 1 -11: (a) events understood as common in human history, (b) events within human history that were tailored by J and P within the context of Israel, and (c) events taken from J and P to form the storyline of Gen 1-11 itself.

Rather than asking "Which account is dependent?" it is more important to investigate why the final redactor chose to keep these themes (e.g., creation and rest) together.38 It is a question of discerning the theological trajectory that these themes carry onward into the narrative of the Pentateuch.

With this in mind, it is helpful to have some idea of the understanding of rest as it relates to creation in the ANE as a whole and, in turn, its reflection in the tradition and worship of Israel. Whether or not one agrees with Wester-mann's source-critical approach, his point remains. Whatever the means by which the Pentateuch came to be in the form that it is now found, it stands as a theological argument that advocates itself as the history and experience of humanity as a whole. We should, therefore, not be surprised to find similar traditions apart from Gen 1-11. Indeed, the traditions of other cultures may shed light on the motifs that are represented in the Pentateuch.39

2 Conceptions of rest in the Ancient Near East

In the literature of the ANE, the gods placed a high premium on rest. Disturbances that interrupt rest lead to conflict. In the Akkadian epic Enuma Elis, the god Apsu becomes irritated because his rest is interrupted by lesser gods. He agitates for the destruction of those who would dare to interrupt it:

Their ways are truly loathsome unto me.

By day I find no relief, nor repose by night.

I will destroy, I will wreck their ways,

that quiet may be restored. Let us have rest!40

His suggestion is met with great enthusiasm by his royal advisor Mummu:

Do destroy, my father, the mutinous ways.

Then shall you have relief by day and rest by night.

When Apsu heard this, his face grew radiant because of the evil he

planned against the gods, his sons.41

Not only was the absence of rest an unsavory condition to be rectified by whatever means necessary, but often the primary reason for a god's creative activity was to create space in which he could rest.42 Rest was achieved when stability marked an environment. It was more than the absence of a particular activity; it was the ongoing flow of a properly ordered routine.43

Rest was also associated with temple structures. Once strife and disorder were ended, the stability that supports and sustains normal modes of existence could continue. In the mind-set of the ANE, the most appropriate place to enjoy that stability was in a temple. Walton goes so far as to suggest that the definition of a temple is a place of divine rest.44 However, a temple was not simply a place of inactivity - it was the place from which the deity ruled. Thus, in Enuma Elis, lesser gods build a temple for Marduk's rest after he slays Tiamat (a personification of the primeval ocean):

Let us build a shrine whose name shall be called "Lo, a Chamber for

Our Nightly Rest"; let us repose in it!

Let us build a throne, a recess for his abode!

On the day that we arrive we shall repose in it.

When Marduk heard this, his features glowed brightly, like the day:

"Construct Babylon, whose building you have requested .,."45

We could add to this the Kes Temple Hymn (Sumerian) as another example of the same idea46 and several other works from Egyptian and Meso-potamian sources.47

3 Concepts of rest in Israel

Similar ideas are found in the life of Israel. To begin with, the first creation account paints a similar picture. While some scholars rightly stress the creation of humanity as the rhetorical high point of the first creation account,48 the account concludes with God taking up his rest. As Wenham remarks, man is "without doubt the focal point of Genesis 1" and the climax of the six days of creation, but not creation's conclusion.49 As noted earlier, the seventh day was set apart as uniquely belonging to God, because rest was at hand and order had been established. Childs50 describes this sanctification (and, by derivation, the rest that marks it) as the whole point of the creation story.51 The problem of the earth's condition as "without form and void," introduced in Gen 1:2 (similar to the lack of order and stability that was fought against in other ANE rest stories), has been rectified with the commencement of the seventh day and divine rest begins.

Additional parallels are found in Israel's temple. Second Sam 7:1-6 describes David's intention to build a temple for God. David chooses that moment in time because "the LORD had given him rest from all his surrounding enemies" (7:1). While David is not permitted to build the temple, Solomon remarks as he begins making preparations, "But now the LORD my God has given me rest on every side. There is neither adversary nor misfortune" (1 Kgs 5:4). Neither David nor Solomon takes credit for the rest he enjoys. They wholly attribute it to the work of God. Now that God had achieved peace, it was time to build him a proper resting place. Even this movement within the history of Israel parallels the first creation account. God inaugurates a new "order" through David after the cultic "disorder" that marked the periods of the judges and Saul. In Solomon's time, order is firmly established and a place of rest can be constructed.

The culmination of this initiative is described in 2 Chr 6:41. Solomon makes supplication during the temple's dedication and prays:

And now arise, O LORD God, and go to your resting place, you and the ark of your might.

God's "resting place" is marked by the term nil, a form of the verb mi. Exod 20:11 uses nil to describe God's rest on the seventh day rather than mtl. Furthermore, both words are used together in Exod 23:12 to describe Sabbath rest. Generally speaking, nil describes a settlement from agitated movement that is enjoyed in an environment of stability and security.52 The connections between rest, stability, and security are clearly articulated in passages that speak about Israel's "rest" in the Promised Land. Deut eronomy 12:10 is typical: "But when you go over the Jordan and live in the land that the LORD your God is giving you to inherit, and when he gives you rest (nil) from all your enemies around, so that you live in safety ."53

Thus, the temple is described as the place where God takes up his rest. Like the rest that Israel enjoyed at the completion of Canaan's conquest, it is a place where there is a sense of safety and security - a place where things are properly ordered and working as they were intended to work. Everything is as it should be.

Psalm 132:7-8, 13-14 also describes YHWH's tabernacle/temple as a resting place:

7"Let us go to his dwelling place;

let us worship at his footstool!"

8Arise, O LORD, and go to your resting place,

you and the ark of your might.

13For the Lord has chosen Zion;

he has desired it for his dwelling place:

14"This is my resting place forever;

here I will dwell, for I have desired it."

Verse 7 makes use of the term " . Translated as "dwelling place," it is often used to describe the tabernacle as the dwelling place of God.54 It is the place of his "footstool." These two terms are respectively paralleled in v. 8 by "resting place"

. Translated as "dwelling place," it is often used to describe the tabernacle as the dwelling place of God.54 It is the place of his "footstool." These two terms are respectively paralleled in v. 8 by "resting place"  a nominal form of the verb mi) and "ark." Thus God's tabernacle is his resting place. It is the place where his footstool, the ark, may be found

a nominal form of the verb mi) and "ark." Thus God's tabernacle is his resting place. It is the place where his footstool, the ark, may be found  usually the Ark of the Covenant). God's dwelling place is mentioned again in v. 13, this time using the term Zion to refer generally to Jerusalem and more specifically to the temple (i.e., the place of God's presence among his people). Zion is then subsequently described in v. 14 as his "resting place" (again using

usually the Ark of the Covenant). God's dwelling place is mentioned again in v. 13, this time using the term Zion to refer generally to Jerusalem and more specifically to the temple (i.e., the place of God's presence among his people). Zion is then subsequently described in v. 14 as his "resting place" (again using  In other words, the temple is his resting place. It is located in the midst of his people, and it is the place where he desires to dwell.55

In other words, the temple is his resting place. It is located in the midst of his people, and it is the place where he desires to dwell.55

The connection between the rest described by both the tabernacle/temple and creation is bolstered by the creation imagery later appropriated for the tabernacle/temple. Numerous scholars56 note the parallels between the description of creation in Genesis 1 and the building of the tabernacle:

Both accounts use similar terminology: God saw everything that he had made, and Moses saw all the work (Gen 1:31||Exod 39:43). The heavens and the earth were finished, and the work of the tabernacle of the tent of meeting was finished (Gen 2:1||Exod 39:32). God finished his work, and Moses finished the work (Gen 2:2||Exod 40:33). God blessed the seventh day, and Moses blessed them (Gen 2:3||Exod 39:43). Other parallels between tabernacle/temple and creation (e.g., the imagery of Ezek 41 and 47) could be added.57

The notion that God's creative activity was intended for rest and that divine rest is properly found in a temple clarifies the situation of the seventh day and the subsequent theological trajectory of the tabernacle/temple. Walton, in fact, begins with the idea that the creation of the cosmos is not primarily focused on a space for humanity to live, but rather as a haven for God him-self.58 While Genesis describes humanity and its supporting environment, emphasis is laid upon how they function within that haven. This situation is then reflected in the temple. Walton is not alone; other scholars over the past decade have also argued that the cosmos is, in essence, a primordial temple and that the Garden of Eden is a microcosm of it.59 This view is not, however, without controversy. More recently, Block has begun to challenge this under-standing.60 While Block concurs that Israel's tabernacle and temple were microcosms of YHWH's heavenly temple and "constructed as miniature Edens,"61 he argues that viewing creation as a cosmic temple and Eden as a microcosm of that temple is to import later theological understanding into the creation narratives. Instead, when the tabernacle and temple are constructed, they appropriate the imagery of creation to help Israel recall the situation as it stood at the close of the creation week.62 The present article is not intended to argue that the first creation account is a temple-building text. Rather, my purpose is simply to demonstrate two things: firstly, the situation of the seventh day and the rest God enjoyed on it were of such significance that they were later reflected in tabernacle and temple imagery. They explicitly recall the situation of the seventh day - a completed creation and God at rest. Secondly, the imagery and motifs that are common to other creation accounts in the ANE suggest that Israel's story seeks to answer similar questions concerning the purpose of creation.

This does not imply that Israel's conception of God was identical to that of her neighbors. Quite the contrary: Israel's conception highlights the distinc -tions between YHWH and the gods of the surrounding nations.63 However, it is helpful to understand the trajectory of thinking that permeated religious thought and how that may have impacted Israel's religious self-understanding.64 Divine rest was an important matter in the ANE as a whole, and it was no less so to Israel.

The picture presented by the first creation account is that God's rest did not just happen once creation was completed. It was integral to his purpose. Once the ordering of the first six days had been accomplished, he was free to enjoy and oversee a properly functioning world and enter a state of rest. There is no end-of-day refrain on the seventh day because, for YHWH, the seventh day never ended. He did not begin a new work-week at the beginning of the eighth day. He continued in his rest, overseeing a properly ordered cosmos that was now functioning around him. This same rest is later incorporated into the life of Israel in the tabernacle and temple - two institutions that reflect upon the intended life of humanity and its relationship to God as it existed at the close of the creation. As such it was sacred space. We now turn to humanity's role.

D HUMANITY IN THE FIRST CREATION ACCOUNT

The first creation account records both humanity's creation and the function that they were intended to fulfil in Gen 1:26-28:

26Then God said, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth." 27So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.28And God blessed them. And God said to them, "Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth."

Humanity's creation in 1:26-28 can be seen in three movements. Firstly, 1:26 depicts the deliberative process leading to humanity's creation. The volitional forms anticipate God's intentions, describing both the creative activity that God is about to undertake and the purpose for which humanity is to be created. The cohortative  ("let us make") is followed by the jussive

("let us make") is followed by the jussive  ("and let them have dominion"). The second volitional form is rendered as the purposeful result of the first. Thus, humanity is made in the image and likeness of God so that they may exercise dominion.65

("and let them have dominion"). The second volitional form is rendered as the purposeful result of the first. Thus, humanity is made in the image and likeness of God so that they may exercise dominion.65

Two things happen with the second movement depicted in 1:27:

• Firstly, humanity is successfully created in the image of God. Thus the volitional forms of 1:26 have come to fruition.

• Secondly, humans are specified as male and female. Unlike the other creatures, humans are the only aspect of creation that are made in God's image. Both male and female humans are made in the image of God, and the genders themselves reflect something of the image of God.66

The final movement of 1:28 actualizes the desire that was expressed in 1:26b. While 1:26b expresses the desire God has for a creature that exercises dominion, 1:28 describes God's instruct ions to his finished creation to carry out that function.

The imperatives of 1:28 define YHWH's tasks for humanity.67 They can be divided into three primary functions: to reproduce, to subdue, and to exercise dominion. We will look at each function in turn with a view toward understanding humanity's role at the dawn of the seventh day. However, before doing this we conduct a short overview of the imago Dei idea to see how it impacts our understanding of these three functions.

In this examination, it is important to keep the idea of "blessing" close at hand. God blesses humanity before any imperatives are given (1:28a), and this blessing serves as a backdrop that underscores the means by which humanity accomplishes its function. As seen above, blessing involves both relationship and the ability to carry out a function. Here, humans are placed in a particular relationship with YHWH (the only creatures made in his image) and granted the ability to carry out the particular functions of dominion, subduing, and reproduction.

1 Made in the Image of God

God's desire to make humanity  "in our image, according to our likeness" is one of the most striking aspects of the first creation account. In other respects humans are described similarly to their fellow creatures. Like the birds and sea creatures of the fifth day, they are given the command to "be fruitful and multiply." The exact nature of the similarity is not detailed but construed from the context;68 but none of the other creatures are described in like manner. Humanity alone is created in the imago Dei.

"in our image, according to our likeness" is one of the most striking aspects of the first creation account. In other respects humans are described similarly to their fellow creatures. Like the birds and sea creatures of the fifth day, they are given the command to "be fruitful and multiply." The exact nature of the similarity is not detailed but construed from the context;68 but none of the other creatures are described in like manner. Humanity alone is created in the imago Dei.

Erickson69 surveys the various perspectives of the imago Dei and distils them into three primary viewpoints:

• The Substantive View holds that particular characteristics of God's image are an ontological part of humanity. These characteristics may be physical, psychological, or spiritual.

• The Relational View argues that the imago Dei is inherently tied to humanity's relational ability. Humanity's relationships are reflective of the relationships that are found within the Godhead.

• The Functional View holds that the imago Dei is related to a task that humanity performs rather than something inherent in the makeup of mankind.

Other scholars question the way in which each of these views excludes the other in favor of an understanding that incorporates aspects of each. Grudem defines the image of God in this way: "The fact that man is in the image of God means that man is like God and represents God."70 He suggests that previous attempts to specify sole characteristics as the mark of image-bearing are unnecessarily restrictive.71 Instead, various facets of God-likeness include the moral, spiritual, mental, relational, and physical.72 Williams' conclusion pushes in the same direction: "The image constitutes both our constitution and our function, our being and our doing."73 Humanity is God's representative on earth. Proper representation involves both what humans are and what they do.74 Walton concludes his discussion of the image of God by saying,

The image is a physical manifestation of divine (or royal) essence that bears the function of that which it represents; this gives the image-bearer the capacity to reflect the attributes of the one represented and act on his behalf.75

The result is the same, whether one holds that the command to exercise dominion was a consequence of humanity's being made in the image of God or intrinsic to it: on the seventh day humanity existed in the image of God in exact alignment with God's intentions for them. The man and woman stood as representatives of God in the midst of creation.

2 Multiplying and filling the earth

After God pronounces his blessing upon humanity, the first three imperatives that he gives are to be "fruitful and multiply and fill the earth." Inherent to the creation of humanity is the drive and ability to procreate and fulfil the mandate, and it is by the blessing of God that they will do so. Furthermore, while these are separate imperatives, their applications are related to one another; to be fruitful is to "produce offspring." As people heed the command to produce offspring, they will "become many" or "increase." As they become more numerous, there will be a need to spread out, and thus the idea of filling the earth is a consequence of God's order to be fruitful.76

The same notion finds numerous reverberations throughout the Pentateuch. When Noah leaves the ark, God tells him,

Bring out with you every living thing that is with you of all flesh -birds and animals and every creeping thing that creeps on the earth -that they may swarm on the earth, and be fruitful and multiply on the earth (Gen 8:17).

Not only are the animals to multiply on the earth again, but the command is repeated to humanity through Noah and his sons (Gen 9:1, 7). The concept of multiplication is also repeated with the patriarchs.77 Not only do we find these specific references, but the repeated genealogies express the idea of fulfilment of these imperatives.78

3 Subduing the earth

As humanity fills the earth they will need to "subdue" (tinn) it. The general sense of inn is to "make subservient" to or "subjugate"; in one usage it is even suggestive of rape (Esth 7:8).79 In some instances, the context is sociological/political: the objects to be subdued are people (Jer 34:11) or nations (2 Sam 8:11). When Reuben and Gad wish to settle on the east side of the Jordan, Moses allows them to do so on condition that they continue fighting for the Promised Land with the rest of Israel. They can return to their homes when the fighting is finished "and the land is subdued before the LORD" (Num 32:22). Similarly, in Josh 18:1, Israel can allocate land to the tribes because "the land lay subdued before them." We can say that the use of inn in the OT suggests the meaning of "to make to serve, by force if necessary,"80 and furthermore that the object being subdued may not be naturally inclined to cooperate, and that some force of will on the part of the subject will be necessary.

Genesis 1:28 is the only place where the earth is the object of Con-textually, it means to "bring something under control ."81 The implication is that creation will need to be subdued by humanity's force of will.82 Two conclusions emanate from this understanding of Firstly, aspects of creation needed to be subdued in some way or had the potential for lapsing into an unordered state at the close of the first creation account. Genesis 2-3 explores this concept more fully when humanity is placed in the garden "to work and keep it" (Gen 2:15). The mandate to subdue the earth was intended for its good, just as God's own ordering of the earth was "good." As humanity fulfilled its instruction to multiply and fill the earth, this blessing would move forward to spill out beyond the borders of the garden of Eden to the rest of the earth as well.83 The second implication is that humanity's "ráD" should reflect God's work. God exerted his will and effort to move creation from a state that was "without form and void" (1:2) to a state that was "very good" (1:31). Humanity will mirror this as it exerts will and effort to maintain and expand order. As humanity takes seriously its function of multiplying and filling the earth, they will move out into the area beyond the garden. In so doing, they will need to subdue the land that is outside of the garden so that it becomes like the land that is within the boundaries of the garden. This suggests that there is a difference between that which lies within the garden and that which lies outside it.84

4 Exercising dominion over the earth

The commands to (1) multiply and (2) subdue the earth will require humanity to exercise dominion over the animals which inhabit it. The verb mi can variously mean to "tread," "rule,"85 or "have dominion over."86 The object is often marked by 3, signifying that over which rule or dominion is held. Thus, subduing the earth includes exercising dominion over the fish, birds, livestock, the earth, and every creeping thing (1:26).87 Similarly, Gen 1:28 repeats the idea of dominion over the fish and birds, but omits the term (livestock) and topi (creeping thing) in favor of rt£>Enn fiNm1?!? (lit.: the things creeping upon the earth). In 1:28, the participle r^pin is used as a substantive and, although it shares the same root as the nominal form (topi) found in 1:26, its use in 1:28 is broader than its use in 1:26.88 Hence, many English versions translate this with "every living thing that moves upon the earth."89

Moreover, the notion of royalty was associated with  in the ANE. Like the first creation account, the royal courts of Babylon and Egypt associated

in the ANE. Like the first creation account, the royal courts of Babylon and Egypt associated  with creation and human dominion over the animal world. However, in contrast to their creation accounts (which portray humanity as the gods' answer to relieve themselves of unwanted work), the "goal" of humanity in the Hebrew account is linked to the good of the world and introduces a social structure that is characteristic for the creatures who inhabit God's world.90 Furthermore, as demonstrated with the ideas of "image" and "likeness," it is suggested that humanity exercises this rule as the embodied representative of God. This association with royal rule reflects God's own rule over creation.

with creation and human dominion over the animal world. However, in contrast to their creation accounts (which portray humanity as the gods' answer to relieve themselves of unwanted work), the "goal" of humanity in the Hebrew account is linked to the good of the world and introduces a social structure that is characteristic for the creatures who inhabit God's world.90 Furthermore, as demonstrated with the ideas of "image" and "likeness," it is suggested that humanity exercises this rule as the embodied representative of God. This association with royal rule reflects God's own rule over creation.

For the present article, the relevance of the imago Dei lies in the fact that humanity performed the function of rule as the embodied representative of God on the seventh day, whereas God rests. The seventh day depicts God as resting; at the same time, humanity stands as his representative, exercising dominion over the earth and every living thing that moves on it in a fashion reminiscent of God's own actions in creation. This situation reinforces the notion that rest is accessible to God because things are indeed ordered and working as he intended.

E CONCLUSIONS

The lead actor in the first creation account is God. He makes everything, and when he is finished with his work he stops his creative activity. His "rest" is rest from the particular activity of creation. It is not merely leisure, nor is it rest from all forms of work. It is rest in an ordered environment where things are functioning in a particular manner. In this way, the conception of rest reflected in the first creation account is not dissimilar to the ideas of rest that are found in other traditions of the ANE. In the ANE, the purpose of creative activity was often tied to the desire for rest on the deity's part. Furthermore, the place of rest for an ANE deity was found in a temple. This second aspect is also found in the OT in texts that speak about Israel's temple. Together, these ideas serve to tie the history of Israel into the history of humanity as a whole. Finally, God's rest at the end of the first creation account is pictured as something that does not end. The account closes with him at rest and a created order that functions according to plan.

At the same time, humans have a role to play. Their focus is to live as God's image-bearers within creation. As such they have several functions:

reproducing and filling the earth, subduing the earth as they expand the borders of the garden, and reigning over the other creatures. The text gives no indication that humans rest in the same way that God rests. Quite the contrary - as God rests, humans are busily going about all of the functions that they were created to fulfil.

The resultant picture is of a God Who is resting from his creative activity because the created order fulfils his intentions. He is in a position to enjoy all that he has made, and specifically the image-bearer, who functions on his behalf in its midst. Humanity, for their part, is poised to carry out its creation mandate as the seventh day dawns. However, as indicated by the lack of an evening and morning refrain, the seventh day is no ordinary day. It does not end, and the implication is that God's rest will continue unabatedly while humanity labors before him in their appointed tasks.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnold, Bill and Brian Beyer. Readings from the Ancient Near East: Primary Sources for Old Testament Study. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002. [ Links ]

Beale, Gregory. The Temple and the Church's Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God. NSBT 17. Downers, Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2004. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. The Pentateuch: An Introduction to the First Five Books of the Bible. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel. "Eden: A Temple? A Reassessment of the Biblical Evidence." Pages 3-30 in From Creation to New Creation: Essays in Honor of G. K. Beale. Edited by Daniel M. Gurtner and Benjamin L. Gladd. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2013. [ Links ]

Botterweck, G. Johannes and Helmer Ringgren, eds. Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. 10 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. 1975. TDOT [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, Samuel Driver, and Charles Briggs. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2008. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. Genesis. IBC. Atlanta, GA: John Knox, 1982. [ Links ]

Childs, Brevard S. Exodus: A Commentary. London: SCM, 1974. [ Links ]

Clines, David, ed. The Concise Dictionary of Classical Hebrew. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2009. [ Links ]

_______. The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew. 8 vols. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 2011. [ Links ]

Collins, C. John. Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary. Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian & Reformed, 2006. [ Links ]

Erickson, Millard. Christian Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1985. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. Text and Texture. New York, NY: Schoken, 1979. [ Links ]

Girdlestone, Robert. Girdlestone's Synonyms of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1897. [ Links ]

Grudem, Wayne. Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Literature. Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1994. [ Links ]

Hamilton, Victor. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990. [ Links ]

Harris, R. Laird, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, eds. Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. 2 vols. Chicago, IL: Moody, 1980. [ Links ]

Jenni, Ernst and Claus Westermann, eds. Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament. 3 vols. Translated by Mark E. Biddle. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1997. [ Links ]

Joosten, Jan. The Verbal System of Biblical Hebrew. 2nd ed. JBS 10. Jerusalem: Simor, 2012. [ Links ]

Joüon, Paul and Takamitsu Muraoka. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. 2nd ed. Rome: Gregorian & Biblical Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Keil, Carl. The Pentateuch. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1866. [ Links ]

Koehler, Ludwig and Walter Baumgartner, eds. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. 5 vols. Leiden: Brill, 2000. [ Links ]

Lust, Johan, Erik Eynikel, and Katrin Hauspie. A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint. Rev. ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2003. [ Links ]

Richards, Kent. "Bless/Blessing." ABD 1: 753-755. [ Links ]

Robinson, Gnana. "The Idea of Rest in the Old Testament and the Search for the Basic Character of the Sabbath." ZAW 92/1 (1980): 32-42. [ Links ]

Speiser, Ephraim. Genesis. 3rd ed. AB 1. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1981. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, Christo, Jackie Naudé, and Jan Kroeze. A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999. [ Links ]

VanDrunen, David. Divine Covenants and Moral Order: A Biblical Theology of Natural Law. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2014. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem, ed. New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis. 5 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. 1997. [ Links ]

Von Rad, Gerhard. Genesis: A Commentary. Rev. ed. Translated by John H. Marks. OTL. London: SCM, 1972. [ Links ]

Waltke, Bruce. Genesis: A Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001. [ Links ]

_______. An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical, and Thematic Approach. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007. [ Links ]

Walton, John. Genesis. NIVAC 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001. [ Links ]

_______. The Lost World of Genesis One. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2009. [ Links ]

Wenham, Gordon. Genesis 1-15. WBC 1. Waco, TX: Word, 1987. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Genesis 1-11: A Commentary. Translated by John J. Scullion. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1984. [ Links ]

Williams, Michael. "First Calling: The Imago Dei and the Order of Creation." Presb 39/1 (2013): 30-44. [ Links ]

Wright, Chris. Old Testament Ethics for the People of God. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2004. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 23/06/2017

Peer-reviewed: 31/07/2017

11/09/2017

Rev. Matthew Haynes, PhD (candidate), North-West University. He is also an adjunct OT lecturer at the Bible Institute of South Africa, 180 Main Road, Kalk Bay, 7975, near Cape Town, RSA. Email: mbhaynes@bisa.org.za.

Prof. Paul Krüger, School of Biblical Studies and Bible Languages, North-West University. Private Bag X6001, 2520 Potchefstroom, RSA. Email: paul.kruger@nwu.ac.za.

1 Unless otherwise noted, all translations are taken from the ESV.

2 So Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11: A Commentary., trans. John J. Scullion (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1984), 168-169 and Bruce Waltke, An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical, and Thematic Approach (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007), 186.

3 See Christo Van der Merwe, Jackie Naudé, and Jan Kroeze, A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999), §21.2.3(i); Paul Joüon and Takamitsu Muraoka, A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew, 2nd ed. (Rome: Gregorian & Biblical Press, 2011), §118i, and Gordon Wenham, Genesis 1-15, WBC 1 (Waco, TX: Word, 1987), 5, who all cite this verse as a summative or conclusive example of the wayyiqtol.

4 David Clines, "כלה ,"I," DCH 4:416.

5 BDB, 477; HALOT 2:477.

6 See "συντέλεω," LEH electronic ed.

7 John Oswalt, ""כלה ,"," TWOT 1:439.

8 Waltke, Old Testament Theology, 186.

9 C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian & Reformed, 2006), 49n41.

10 See "צָּבָּא ," BDB, 838.

11 Carl Keil, The Pentateuch (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1866), 42.

12 Wenham, Genesis 1-15, 5.

13 Wenham, Genesis 1-15, 5; Victor Hamilton, The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), 142.

14 Collins, Genesis 1-4, 71.

15 Ephraim Speiser, Genesis, 3rd ed., AB 1 (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1981), 7-8.

16 Cf. ESV, NIV (1984), NIV (2011), RSV, KJV, ASV (1901), HCSB, and NASB (1977), to name just a few.

17 Victor Hamilton, "שׁבת ," TWOT2:902.

18 See " "שׁבת ,"," BDB, 991; Fritz Stob; ""שׁבת ,"," TLOT 3:1298; David Clines, "שׁבת ," CDCH, 448.

19 Keil, Pentateuch, 42; Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 173; John Walton, Genesis, NIVAC 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 148; Collins, Genesis 1-4, 89.

20 Collins, Genesis 1-4, 92. Cf John 5:17.

21 Kent Richards, 'Bless/Blessing," ABD 1:754.

22 Carl A. Keller, "ברך ,"in," TLOT 1:270.

23 John Oswalt,"ברך ," in," TWOT 1:132.

24 See"ברך ," "in," HALOT 1:160.

25 Waltke, Old Testament Theology, 62.

26 Joseph Scharbert, "ברך ,"TDOT 2:303; Michael Brown, "ברך ," NIDOTTE 1:758-759; Gerhard Wehmeier, "ברך ," TLOT 1:278.

27 BDB, 872; HALOT 3:1073.

28 DCH 7:192. See also Jackie Naudé, "קדשׁ ," NIDOTTE 3:877, who makes a similar statement suggesting that it is because the day belongs to God.

29 Keil, Pentateuch, 42.

30 Robert Girdlestone, Girdlestone's Synonyms of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1897), 175.

31 Naudé, NIDOTTE 3:885.

32 Bruce Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 68; Walton, Genesis, 152-153; Collins, Genesis 1-4, 125, 129.

33 John Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2009), 71-76.

34 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 2-6.

35 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 65.

36 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 65.

37 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 5-6.

38 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 6.

39 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 19-20.

40 Bill Arnold and Brian Beyer, Readings from the Ancient Near East: Primary Sources for Old Testament Study (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 32. Also cited by Gerhard von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary, rev. ed., trans. John H. Marks, OTL (London: SCM, 1972), 60; Walton, Genesis, 150; and Gregory Beale, The Temple and the Church's Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God, NSBT 17 (Downers' Grove, IL: Intervarsity, 2004), 64.

41 Arnold and Beyer, Readings, 33.

42 Walton, Genesis, 150.

43 Walton, Lost World, 72.

44 Walton, Lost World, 71.

45 Arnold and Beyer, Readings, 43.

46 Walton, Lost World, 74-75.

47 Beale, Temple, 51-52.

48 Walter Brueggemann, Genesis, IBC (Atlanta, GA: John Knox, 1982), 31; Collins, Genesis 1-4, 72.

49 Wenham, Genesis 1-15, 37.

50 Brevard S. Childs, Exodus: A Commentary (London: SCM, 1974), 416. See also Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 90; Walton, Genesis, 148.

51 Von Rad, Genesis, 60.

52 John Oswalt, "נוח ," NIDOTTE 3:57.

53 See also Josh 21:44; 23:1. Gnana Robinson, "The Idea of Rest in the Old Testament and the Search for the Basic Character of the Sabbath," ZAW 92/1 (1980): 34-35 argues along similar lines.

54 Cf Exod 25:9, 38:21; Num 10:17; Pss 26:8; 43:3; 74:7.

55 Walton, Lost World, 72-73.

56 Michael Fishbane, Text and Texture (New York, NY: Schoken, 1979), 12; Joseph Blenkinsopp, The Pentateuch: An Introduction to the First Five Books of the Bible (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992), 217-218; Walton, Genesis, 49; Beale, Temple, 60-63; et al.

57 Beale, Temple, 60-63; Daniel Block, 'Eden: A Temple? A Reassessment of the Biblical Evidence," in From Creation to New Creation: Essays in Honor of G. K. Beale, ed. Daniel M. Gurtner and Benjamin L. Gladd (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2013), 18.

58 Walton, Genesis, 147.

59 See Block, "Eden: A Temple?" 4, for an extensive listing of scholars who argue for this view.

60 Block, "Eden: A Temple?" 3-30.

61 Block, "Eden: A Temple?" 3-4.

62 Block, "Eden: A Temple?" 20-21.

63 See Deut 4:32-40; Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 26; Wenham, Genesis 1-15, 37; Walton, Genesis, 157.

64 See Von Rad, Genesis, 60.

65 Chris Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2004), 119. See also Jan Joosten, The Verbal System of Biblical Hebrew, 2nd ed., JBS 10 (Jerusalem: Simor, 2012), 140-143.

66 Hamilton, Chapters 1-17, 138.

67 Cf. Joüon and Muraoka, Grammar, §114a, who describe all five of these as "direct" imperatives.

68 Cf Ezek 1:5, 10, 13, 16, 22, 26, 28; 10:1, 10, 21, 22; Dan 10:16. See also Victor Hamilton, "דְמוּת ," TWOT 1:437.

69 Millard Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1985), 498-510.

70 Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Literature (Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1994), 442.

71 Grudem, Systematic Theology, 443.

72 Grudem, Systematic Theology, 445-448.

73 Michael Williams, "First Calling: The Imago Dei and the Order of Creation," Presb 39/1 (2013): 43.

74 E.g. Von Rad, Genesis, 60; Williams, "First Calling," 43; David VanDrunen, Divine Covenants and Moral Order: A Biblical Theology of Natural Law (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2014), 68.

75 Walton, Genesis, 131.

76 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 141.

77 See Gen 17:6; 28:3; 35:11, its fulfilment in Gen 47:27; 48:4, and Exod 1:7.

78 Gen 4:1-2; 17-26; 5:1-32; 6:9-10; 9:18-28; 10:1-32; 11:10-26, 28-32. Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 9-18.

79 DCH 4:361.

80 John Oswalt, "inn," TWOT 1:951.

81 Walton, Genesis, 132.

82 Oswalt, TWOT 1:951.

83 Collins, Genesis 1-4, 69.

84 Walton, Genesis, 86.

85 HALOT 3:1190.

86 CDCH, 414.

87 Although the terminology differs, see also Ps 8 (particularly vv. 6-8), which alludes to Gen 1:26-28, celebrating the privileged position of humanity by, in part, addressing the theme of humanity's dominion.

88 HALOT 3:1246.

89 Cf. ASV, ESV, KJV, NET, NASB, NIV.

90 Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 158-159.