Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 no.3 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n3a3

ARTICLES

Trails of a different Vorlage and a free translator in LXX-Proverbs: A text-critical analysis of Proverbs 16:1-7

Bryan Beeckman

Katholieke Universiteit, Leuven

ABSTRACT

In recent Septuagint scholarly debates, a great deal of attention has been given to the Book of Proverbs. This book, unlike others, has not been extensively studied regarding translation techniques or text-critical research. Nevertheless, the textual witnesses of Proverbs demonstrate some variants, particularly many minuses and pluses, which are relevant to our understanding of the text. This article presents a text-critical analysis of Prov 16:1-7 using the methodology proposed by Bénédicte Lemmelijn presented in her book A Plague of Texts? A Text-Critical Study of the So-Called "Plague Narrative" in Exodus 7:14-11,10. The results of this analysis led to the conclusion that the LXX translator, who translated freely, had a different Vorlage, which had another verse order than MT and 4QProvb. This essay makes a contribution in terms of arriving at a better understanding of the translation technique of LXX-Proverbs.

Keywords: LXX; Proverbs; Text Criticism; Translation Technique

A INTRODUCTION

In recent scholarly debates, much attention has been paid to the Book of Proverbs. 1 This book, unlike others, has not been extensively studied regarding translation techniques or text-critical research. Nevertheless, the textual witnesses of Proverbs demonstrate several variants, more particularly many minuses and pluses relevant to our understanding of the text. In this contribution, I will make an attempt to analyse Prov 16:1-7 in a text-critical way.

The methodology used in this article is the one proposed by Bénédicte Lemmelijn in her book A Plague of Texts? A Text-Critical Study of the SoCalled "Plague Narrative" in Exodus 7,14-11,10.2Her methodology consists of three parts: the collection of variants in a synoptic survey (i.e. registration), the description of variants, and the evaluation thereof.3

Before I start our own text-critical investigation, a brief state of affairs is offered regarding text-critical issues in Prov 16:1-7. Afterwards, I present an analysis of the verses, in three stages, using Lemmelijn's methodology. In the first part, I register all the variants by comparing the Masoretic Text (MT), Septuagint (LXX) and 4QProvb,4 by means of a textual synopsis. In the second part, I describe the variants in detail. Every variant is described in an objective way without offering an interpretation at this stage. In the third and final part, I evaluate all the different variants based on the results of part 1 and part 2. At the end of this contribution, some concluding remarks are offered as well as a number of suggestions for further research.

B PROVERBS 16:1-7: THE STATE OF AFFAIRS

Before performing my own text-critical analysis and describing the textual problems concerning Prov 16:1-7, it would be helpful to explore what has already been written about it. This succinct outline sets out to present the scholarly debates concerning Prov 16:1-7.

A number of classical Biblical commentaries on Proverbs suggest that no explicit mention is made regarding textual problems relating to Prov 16:17.5 However, when one looks at the Hebrew version as well as the Greek version of the text itself, a couple of major minuses in the LXX becomes clear. Some verses are completely missing in the LXX. When one looks at the specific literature regarding text-critical problems in the Book of Proverbs, it is notable that Emanuel Tov,6 Johann Cook7 and Michael Fox8 described the textual issues regarding Prov 16:1-7 more thoroughly than the commentaries did.

Tov describes ch. 16 as demonstrating one of the major visible differences between MT and the LXX, namely "transpositions of verses and group of verses."9 He disagrees with de Lagarde, who argues that the reason for these transpositions is connected to textual transmission.10 De Lagarde argues that the Hebrew Vorlage, which the translator would have known, did not contain vv. 16:6-9, nor vv. 1-3 and 5.11 The translator read the chapters, which were presented next to each other in adjacent columns, incorrectly and miscopied the verses. De Lagarde writes:

[M]it 15,27-29 lief ein nach semitischer anschauung [sic] rectum folium aus, und auf dem linken rande [sic] desselben war 16,6-9 so nachtgetragen, dafs [sic] 166 neben 1627, 167 neben 1528, 168 neben 1529 zu steh[e]n kam, während 169 seine stelle [sic] unter 168 am untern rande [sic] fand. [D]er Übersetzer [sic] nahm nun an, dafs [sic] 166 hinter 1527 gehöre, und so fort.12

Contrary to De Lagarde, Tov argues that MT and the LXX "represent recensionally different traditions"13In this regard, Tov states that:

The sequence of most sayings in these chapters is loose, and as each one is more or less independent, two different editorial traditions could have existed concerning their sequence [...] Furthermore, the type of parallelism of the verses in the arrangement of MT does not make it a more coherent unit than that of the LXX.14

Cook, in turn, pointed out that text-critical reflections on Proverbs are very scarce in OT/Septuagintal research. Therefore, he published a modest article in 2000,15 in which he listed some textual problems concerning the Book of Proverbs. In that article, ch. 16 is also mentioned, although not as thoroughly as ch. 15. Cook argues that ch. 16 of Proverbs contains the same kind of textual problems as ch. 20.16 The Hebrew version of both chapters contains many verses that have no equivalent in the LXX.17 Except for quite some pluses, it contains many apparently inner-textual corruptions.18

Although Cook and Tov explored the issue quite profoundly, they did not consider the Qumran fragment 4QProvb, whereas, I think, this could offer more insight and lead to an even more in-depth analysis of the matter. Fox, however, did take this fragment into account in his analysis of the verses. He argues that the relocation of verses in Prov 16:1-7 is due to "a single person, be it a scribe in the Hebrew transmission, or the Greek translator, or a scribe in the early Greek transmission."19 According to Fox, "scribes in the proto-MT transmission [who] were inspired by the context to add additional relevant proverbs"20 can explain the absence of verses in the LXX. Fox also concurs with Tov that Prov 16:1-7 can be explained due to different recensions of the text.21

Having described the scholarly debate with regard to Prov 16:1-7, I now proceed with my own analysis.

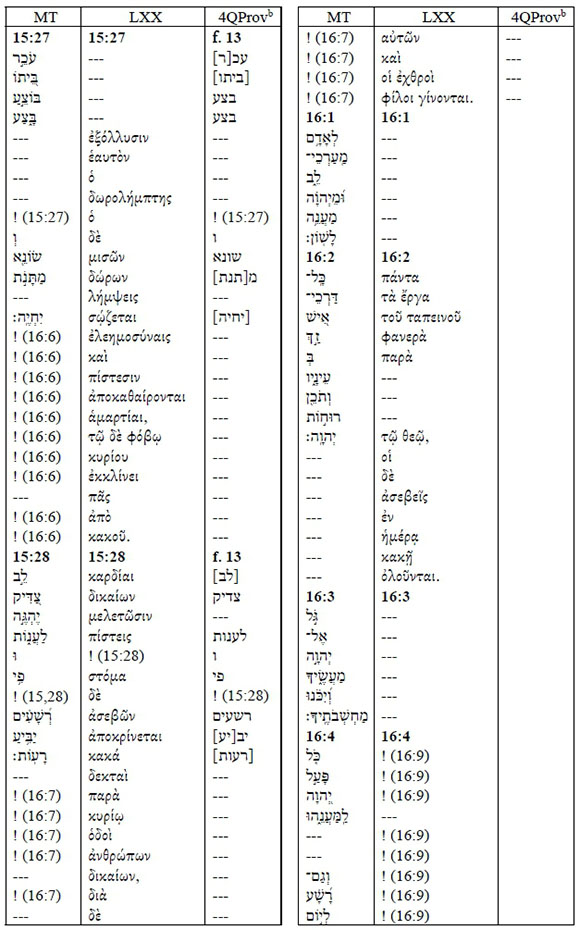

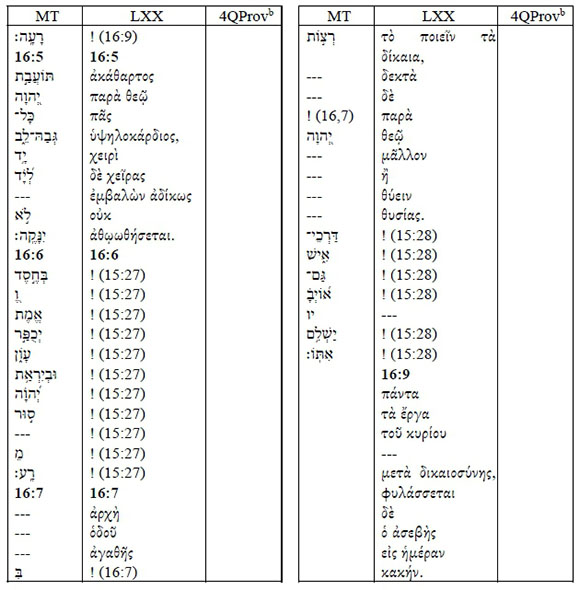

C REGISTRATION OF THE VARIANTS

There are not many variant texts of Prov 16:1-7. The only ones are MT and the LXX, since there are no manuscripts in the Judean desert in which Prov 16:1-7 is extant.22

Nevertheless, although no Qumran scrolls have been discovered for the verses discussed in this article, it is important to look at 4QProvb.23 This fragment contains parts of "13,6-9; 14,5-10; 14,12-13; 14,31-35; 15,1-8 and 15,1931; and possibly 7,9-11."24 In this respect, Prov 15:19b-31 can be significant. Indeed, vv. 27a and 28a of ch. 15 are attested in the LXX as vv. 6 and 7 of ch. 16 in MT.25

In the synopsis below, the same symbol register is used as in Lem-melijn's book: "a combination of three short hyphens (-) designates a minus. Exclamation marks (!) point to a different location of words in the respective columns."26

D DESCRIPTION OF THE VARIANTS

On the basis of the synopsis presented above, one can describe all the different textual variants of Prov 16:1-7. This description is exhaustive, and smaller textual differences are also discussed.

In terms of the textual differences, I use the same format as the one suggested by Lemmelijn.27 In the left hand column, the biblical reference is noted, followed by a definition of the relationship between the textual witnesses for the respective variant.28 In some instances, the chapter of the text is indicated in superscript (e.g., MT16,6 = MT Prov 16:6) in order to clarify a specific variation concerning transposed words. In the right column, the variant is described and discussed. Whenever a variant represents a plus, a plus sign will be placed next to the siglum in which the variant in question is found.29 The description follows the same order as the synopsis set out above. In the process, parts of Prov 15 are also inserted in the analysis.

E EVALUATION OF THE VARIANTS

Now that I have described all the variants, it is possible to evaluate them. Some variants listed above do not present any textual problems. These variants concern a different rendering of the number of nouns (e.g., Prov 15:27 LXX ≠ MT16 / πίστεσιν; Prov 15:28 LXX ≠ MT4QProvb

/ πίστεσιν; Prov 15:28 LXX ≠ MT4QProvb / δικαίων, etc.), an addition of a conjunction (Prov 15:28 MT ≠ LXX δέ; Prov 16:7 MT ≠ LXX δέ) or a variant vocalisation method (Prov 15:27 MT ≠ 4QProvb

/ δικαίων, etc.), an addition of a conjunction (Prov 15:28 MT ≠ LXX δέ; Prov 16:7 MT ≠ LXX δέ) or a variant vocalisation method (Prov 15:27 MT ≠ 4QProvb The registration and description suffice for the present purposes. However, some other variants do present textual problems. I divide them into two categories: "minor" and "major" variants. I first discuss the "minor" variants. The "major," or using Lemmelijn's label, "text-relevant" variants,33 are evaluated thereafter.

The registration and description suffice for the present purposes. However, some other variants do present textual problems. I divide them into two categories: "minor" and "major" variants. I first discuss the "minor" variants. The "major," or using Lemmelijn's label, "text-relevant" variants,33 are evaluated thereafter.

1 "Minor" Variants

If one considers the minor variants, it is clear that most of these can be explained by the translation technique34 of the LXX translator. Most scholars concur that the LXX translator of Proverbs rendered his Vorlage in a "free" way.35 Although there is general consensus concerning the "free" character of the translation, there are still on-going discussions with regard to the "faithfulness"36 of the translation.37

The following variants can be explained by looking at the LXX translator's translation technique.

1a Proverbs 15:27 LXX ≠ MT16

It is clear that the number of words differs. The Hebrew word is singular, whereas the Greek word is in a plural form. As mentioned in the description (see supra), the meaning is also different. MT uses a more general term, namely "goodness/kindness" which differs from the LXX. The Greek version conveys a more specific meaning, namely "kind deeds."38 The LXX translator rendered this word in a rather free manner as he attempted to specify the meaning of the Hebrew word. Still, he remained faithful to his Vorlage, and the meaning of the verse remains the same.

1b Proverbs 15:28 LXX ≠ MT16

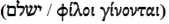

One can gauge that the LXX presents a stronger expression than MT. The translator seems to have made the expression stronger and contrasted οί  with

with  .39This contrast is less obvious in the Hebrew text. One gets the impression that the translator attempted to suggest more than mere forgiveness, which is attested to in the Hebrew text.40 He speaks of reconciliation with enemies. This pertains to the renewal of a relationship that was broken by the reality of evil.

.39This contrast is less obvious in the Hebrew text. One gets the impression that the translator attempted to suggest more than mere forgiveness, which is attested to in the Hebrew text.40 He speaks of reconciliation with enemies. This pertains to the renewal of a relationship that was broken by the reality of evil.

1c Proverbs 15:28 LXX ≠ MT/4QProvb

The LXX notes a noun f. pl., which the Hebrew text does not. MT and 4QProvbcontain a verb in the inf. form. The meaning of the two are completely different: "faithfulness" (Greek) vs. "to answer" (Hebrew). Here, it is clear that the translator attempted to correct the poetical structure of the Hebrew. The Greek word forms a better word pair with xαxά than  with

with  Word pairs are often used in poetry to create parallelism. The parallelism works better in the Greek version than it does in the Hebrew version.41 The LXX-translator was a "creative" translator,42 by improving the poetical structure of the verse.

Word pairs are often used in poetry to create parallelism. The parallelism works better in the Greek version than it does in the Hebrew version.41 The LXX-translator was a "creative" translator,42 by improving the poetical structure of the verse.

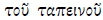

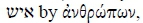

1d Proverbs 16:2 MT ≠ LXX

In this case, it can be seen that the translator dealt with his Vorlage in a free and creative way.  covers a very broad meaning, whereas του ταπεινού (the humble) conveys a more specific quality of

covers a very broad meaning, whereas του ταπεινού (the humble) conveys a more specific quality of  . In Prov 15:28, he translated

. In Prov 15:28, he translated  by ανθρώπων, which conveys a more general meaning than του ταπεινού. In Prov 16:2, the translator probably wanted to specify

by ανθρώπων, which conveys a more general meaning than του ταπεινού. In Prov 16:2, the translator probably wanted to specify  by translating it to του ταπεινού and to contrast it with ασεβείς (the impious). In so doing, he created a word pair του ταπεινοΰ/άσεβεΐς, which results in a type of parallelism in the verse.

by translating it to του ταπεινού and to contrast it with ασεβείς (the impious). In so doing, he created a word pair του ταπεινοΰ/άσεβεΐς, which results in a type of parallelism in the verse.

1e Proverbs 16:4 MT≠ LXX

The Hebrew verb used here conveys the same semantic meaning as the Greek noun (tautology). The translator changed the verb into a noun in relation to his plus μετά δικαιοσύνης φυλάσσεται. I discuss this plus greater in detail below.

1f Proverbs 16:5 MT ≠ LXX

The use of ακάθαρτος as a rendering of  can be regarded as an alternative rendering that the LXX-translator uses in the book as a whole next to βδέλυγμα, which is the more common LXX equivalent.43 In this rendering, the LXX translator "softened" the meaning of the Hebrew. The Hebrew noun means "something detestable/abominable," which has a stronger meaning than the LXX adjective "unclean/impure." It is possible that the translator found the Hebrew word too harsh, and therefore he changed it to a Greek synonym that has a less charged meaning.

can be regarded as an alternative rendering that the LXX-translator uses in the book as a whole next to βδέλυγμα, which is the more common LXX equivalent.43 In this rendering, the LXX translator "softened" the meaning of the Hebrew. The Hebrew noun means "something detestable/abominable," which has a stronger meaning than the LXX adjective "unclean/impure." It is possible that the translator found the Hebrew word too harsh, and therefore he changed it to a Greek synonym that has a less charged meaning.

1g Proverbs 16:5 MT≠ LXX

The Greek translator rendered the idiomatic expression by means of an idiomatic Greek word, instead of translating it literally to υπερήφανος έν καρδία.

by means of an idiomatic Greek word, instead of translating it literally to υπερήφανος έν καρδία.

1h Proverbs 16:5 MT ≠ LXX (έμβαλών αδίκως)

This specific variant is (a) due to a different Vorlage or (b) due to the translator who handled his Vorlage in a free manner. I suggest that the latter is the case. The Hebrew text reads "an abomination to God are all who are high-hearted, hand in hand will not be unpunished,"44 whereas the Greek text reads "everyone who is arrogant is impure with God, and he who unjustly joins hands will not be deemed innocent."45 The translator might have considered that the Hebrew Vorlage did not make sense or was too vague. Therefore, he specified the Hebrew text by clarifying the holding of hands.

1i Conclusion

In my evaluation of the minor variants, I analysed the translation technique of the LXX translator. I found that the translator rendered his Hebrew Vorlage in a free manner. He attempted to soften, strengthen or specify the meaning of the Hebrew language in specific instances. The translator also corrected the poetical structure by improving the parallelisms by means of contrasting.46 In this way, he can be seen as a creative translator. Nevertheless, he remained faithful to his Vorlage by not changing the context or content of the verses.

2 "Major" Variants

Many major pluses are found in Prov 16:1-7; some of which are transposed verses. If one looks at the various textual witnesses, it is clear that 4QProvb has the same sequence as MT in Prov 15:27-28. The plus attests to the LXX version of ch. 15 that does not occur in the Hebrew versions of the text.

On the one hand, Tov ascribes the differences in verse order found in the whole book of Proverbs to a different Vorlage.47This Vorlage "differed recen-sionally" from the one of MT.48 According to Tov, the Vorlage used by the LXX translator of Proverbs reflects another editorial stage than the one of MT.49 On the other hand, Scoralick argues that there were no different versions of the text existing side by side, and does not suggest a different Vorlage.50She argues that the transpositions can be explained by the translator's freedom.51Cook also regards the transposition of verses as an act of the creative mind of the translator.52 According to Cook, there is not a different Hebrew Vorlage, because there is not tangible historical evidence of such a Vorlage.53

I concur with Tov who holds a contrary view to that of Scoralick and Cook. The LXX-translator had a Hebrew Vorlage. This Vorlage differs from MT and 4QProvb in verse order. The larger plusses attested in Prov 16:1-7 can thus be ascribed to this different Vorlage. It would be difficult to see them as the work of the translator. In my opinion, it seems highly improbable that the translator shifted a large number of verses from one chapter to another.54 When one takes note of the writing and copying methods in Antiquity, one has to take into account that papyrus scrolls were used in this period. 55 These scrolls lent themselves to a continuous reading intended for a "start-to-finish"-reading that made it difficult to proceed from one chapter to another.56 Therefore, it is unlikely that the translator shifted entire verses from one chapter to another. In my opinion, this would have demanded a huge amount of time and effort. It is more convincing to claim that the translator remained faithful to the structure of the chapters and verses as attested in his Vorlage. The following variants could then be explained due to this different Vorlage:

2a Prov 15:27 LXX ≠ MT/4QProvb

2b Prov 15:27 LXX ≠ MT/4QProvb (έξόλλυσιν εαυτόν ό δωρολήμπτης)

2c Prov 15:27 LXX ≠ MT/4QProvb (έλεημοσύναις καΐ πίστεσιν άποκαθαίρονται άμαρτίαι, τω δέ φόβω κυρίου έκκλίνει πας από κακου)

2d Prov 15:28 LXX φ MT/4QProvb (δεκταΐ παρά κυρίω οδοί ανθρώπων δικαίων, διά δέ αυτών)

2e Prov 16:1 MT ≠ LXX

2f Prov 16:2 MT ≠ LXX (οί δέ ασεβείς έν ήμερα κακή όλουνται);

2g Prov 16:2 MT ≠ LXX

2h Prov 16:2 MT ≠ LXX

2i Prov 16:2 MT ≠ LXX

2j Prov 16:3 MT ≠ LXX

2k Prov 16:4 MT ≠ LXX (μετά δικαιοσύνης φυλάσσεται)

2l Prov 16:6 MT ≠ LXX (16:6)

2m Prov 16:7 MT ≠ LXX (16:7)

2n Prov 16:7 MT ≠ LXX (αρχή οδου αγαθής) 2o Prov 16:7 MT ≠ LXX (μάλλον ή θύειν θυσίας)

Smaller variants, on the other hand, can often be explained due to the creative mind of the translator as argued supra.

F CONCLUSION

Having presented a detailed text-critical analysis on Prov 16:1-7, we can draw a twofold conclusion.

Firstly, the translator of the LXX-version of Proverbs tried to handle his Vorlage in a free and creative way by softening, strengthening or specifying the Hebrew language. He also corrected the Hebrew text to improve its poetical structure. Nevertheless, and although he moved from his Vorlage in a free way, he remained faithful to it. He did not change the content to the extent that it changed the context in a dramatic way.

Secondly, I noted that there are many transpositions of verses in the different versions. These can be explained by the different Hebrew Vorlage used by the LXX-translator. This Vorlage had another verse order than MT and 4QProvb. Explaining these transpositions as the work of a creative translator seems to be improbable when taking the ancient method of writing and copying into account. Shifting from one chapter to another was difficult when working with papyrus scrolls.

To conclude, Prov 16:1-7 is, of course, a very small fragment of a whole corpus. Therefore, and most probably, this preliminary study is rather limited. Nevertheless, I hope that my suggestions may stimulate other scholars to explore Proverbs in a more profound way and to engage in an exhaustive text-critical analysis of the entire book. It is worthwhile checking and testing whether text-critical research of the book of Proverbs can yield similar insights as the ones presented in the present article.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aejmelaeus, Anneli. "What We Talk About When We Talk About Translation Technique." Pages 531-552 in X Congress of the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies: Oslo, 1998. Edited by Bernard A. Taylor. SBLSCS 51. Atlanta, GA.: Society of Biblical Literature, 2001. [ Links ]

_________. "The Significance of Clause Connectors in the Syntactical and Translation-Technical Study of the Septuagint." Pages 43-57 in On the Trail of the Septuagint Translators: Collected Essays. Edited by Anneli Aejmelaeus. CBET 50. Leuven; Peeters, 2007. [ Links ]

_________. "What We Talk about when We Talk about Translation Technique." Pages 205-222 in On the Trail of the Septuagint Translators: Collected Essays. Edited by Anneli Aejmelaeus. CBET 50. Leuven: Peeters, 2007. [ Links ]

Ausloos, Hans and Bénédicte Lemmelijn. "Faithful Creativity Torn between Freedom and Literalness in the Septuagint's Translations." JNSL 40 (2014): 53-69. [ Links ]

Beeckman, Bryan. "Voorbij vergeving? Een introductie in het boek Spreuken." Ezra 32 (2016): 109-119. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard J. "Observations on the Text and Versions of Proverbs." Pages 4161 in Wisdom, You Are My Sister: Studies in Honor of Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm., on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday. Edited by Michael L. Barré. CBQMS 29. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1997. [ Links ]

_________. Proverbs: A Commentary. OTL. Louisville, KY.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Cook, Johann. "The Dating of Septuagint Proverbs." ETL 69/4 (1993): 383-399. [ Links ]

_________ "'ishah zarah (Proverbs 1-9 Septuagint): A Metaphor for Foreign Wisdom?" ZAW 106/3 (1994): 458-476. [ Links ]

_________. "Contrasting as a Translation Technique in the LXX of Proverbs." Pages 403-414 in The Quest for Context and Meaning: Studies in Biblical Intertextuality in Honor of James A. Sanders. Edited by Craig A. Evans and Shemaryahu Talmon. Leiden: Brill, 1997. [ Links ]

_________. The Septuagint of Proverbs: Jewish and/or Hellenistic Proverbs? Concerning the Hellenistic Colouring of LXX Proverbs. VTSup 69. Leiden: Brill, 1997. [ Links ]

_________. "Textual Problems in the Septuagint Version of Proverbs." JNSL 26/1 (2000): 163-173. [ Links ]

_________. "The Greek of Proverbs: Evidence of a Recensionally Deviating Hebrew Text?" Pages 605-618 in Emanuel: Studies in Hebrew Bible, Septuagint, and Dead Sea Scrolls in Honor of Emanuel Tov. Edited by Shalom M. Paul, Robert A. Kraft, Eva Ben-David, Lawrence H. Schiffman, and Weston W. Fields. Leiden: Brill, 2003. [ Links ]

_________. "Proverbs." Pages 621-647 in A New English Translation of the Septuagint. And the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included Under That Title. Edited by Albert Pietersma and Benjamin G. Wright. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

_________. "The Translator of the Septuagint of Proverbs: Is his Style the Result of Platonic and/or Stoic Influence?" Pages 559-571 in Die Septuaginta: Texte, Kontexte, Lebenswelten. Edited by Jan C. Gertz. WUNT 219. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008. [ Links ]

_________. "Translation Technique and the Reconstruction of Texts." OTE 21/1 (2008): 61-68. [ Links ]

_________. "Were the LXX Versions of Proverbs and Job Translated by the Same Person?" HS 51 (2010): 129-156. [ Links ]

Cook, Johann and Arie van der Kooij. Law, Prophets, and Wisdom: On the Provenance of Translators and their Books in the Septuagint Version. CBET 68. Leuven: Peeters, 2012. [ Links ]

De Lagarde, Paul. Anmerkungen zur Griechischen Übersetzung der Proverbien. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1863. [ Links ]

Derrenbacker, Robert A., Ancient Compositional Practices and the Synoptic Problem. BETL 186. Leuven: Peeters, 2005. [ Links ]

Elliger, Karl, Wilhelm Rudolph, et al., eds. Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 5th ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 1977. [ Links ]

Eve, Eric C. S. "The Synoptic Problem without Q?" Pages 551-570 in New Studies in the Synoptic Problem: Oxford conference, April 2008: Essays in Honour of Christopher M. Tuckett. Edited by Paul Foster, Christopher M. Tuckett, Andrew F. Gregory, John S. Kloppenborg, and Jozef Verheyden. BETL 239. Leuven: Peeters, 2011. [ Links ]

Fox, Michael V. "LXX-Proverbs as a Text-Critical Resource." Text 22 (2005): 95-128. [ Links ]

_________. Proverbs: An Eclectic Edition with Introduction and Textual Commentary. HBCE 1. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Hatch, Edwin and Henry A. Redpath. A Concordance to the Septuagint and Other Greek Versions of the Old Testament (including the Apocryphal Books). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1998. [ Links ]

Lemmelijn, Bénédicte. A Plague of Texts? A Text-Critical Study of the so-called "PlagueNarrative" in Exodus 7, 14-11,10. OtSt 56. Leiden: Brill, 2009. [ Links ]

_________. "The Greek Rendering of Hebrew Hapax Legomena in LXX Proverbs and Job. A Clue to the Question of a Single Translator?" Pages 133-150 in In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes: Studies in the Biblical Text in Honour of Anneli Aejmelaeus. Edited by T. Michael Law, Kristin De Troyer, and Marketta Liljeström, CBET 72, Leuven - Paris - Walpole, Mass.: Peeters, 2014. [ Links ]

_________. "Textual Criticism." Forthcoming in Oxford Handbook of the Septuagint. Edited by Alison Salvesen and T. Michael Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rahlfs, Alfred, ed. Septuaginta. Id est Vetus Testamentum Graece iuxta LXX Interpretes. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2006. [ Links ]

Scoralick, Ruth. "Salomos griechische Gewänder: Beobachtungen zur Septuagintafassung des Sprichwörterbuches." Pages 43-75 in Rettendes Wissen: Studien zum Fortgang weisheitlichen Denkens im Frühjudentum und im frühen Christentum. Edited by Karl Löning and Martin Faßnacht. AOAT 300. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2002. [ Links ]

Scott, Robert B. Y. Proverbs. AB 18. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965. [ Links ]

Soisalon-Soininen, Ilmari. "Die Auslassung des Possessivpronomens im griechischen Pentateuch." Pages 86-103 in Studien zur Septuaginta-Syntax. Edited by Ilmari Soisalon-Soininen, Anneli Aemelaeus, and Raija Sollamo. AASF B/237. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1987. [ Links ]

Tov, Emanuel. "Recensional Differences between the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint of Proverbs." Pages 43-56 in Of Scribes and Scrolls: Studies on the Hebrew Bible, Intertestamental Judaism, and Christian Origins Presented to John Strugnell on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Edited by Harold W. Attridge, John J. Collins, and Thomas H. Tobin. CTSRR 5. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1990. [ Links ]

_________. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. 2nd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press / Assen: Royal Van Gorcum, 1992. [ Links ]

_________. "Recensional Differences between the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint of Proverbs." Pages 419-431 in The Greek & Hebrew Bible: Collected Essays on the Septuagint. Edited by Emanuel Tov. VTSup 72. Leiden: Brill, 1999. [ Links ]

_________. "A Textual-Exegetical Commentary on Three Chapters in the Septuagint." Pages 275-290 in Scripture in Transition: Essays on Septuagint, Hebrew Bible, and Dead Sea Scrolls in Honour of Raija Sollamo. Edited by Anssi Voitila and Jutta Jokiranta. JSJSup 126. Leiden: Brill, 2008. [ Links ]

Tov, Emanuel, Eugene Ulrich, Frank M. Cross, Joseph A. Fitsmyer, Peter W. Flint, Sarianna Metso, Catherine M. Murphy, Curt Niccum, and Patrick W. Skehan, eds. Psalms to Chronicles. Vol. 11 of Qumran Cave 4. DJD 16. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Toy, Crawford H. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Proverbs. ICC. Edinburgh, T&T Clark, 1959 [repr. 1899]. [ Links ]

Van der Louw, Theo A. W. "Transformations in the Septuagint: Towards an Interaction of Septuagint Studies and Translation Studies." Ph.D. diss., Leiden, 2006. [ Links ]

_________. Transformations in the Septuagint: Towards an Interaction of Septuagint Studies and Translation Studies. CBET 47. Leuven: Peeters, 2007. [ Links ]

Waltke, Bruce K. The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 15-31. NICOT. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005. [ Links ]

Submitted: 14/03/2017

Peer-reviewed: 11/04/2017

Accepted: 17/08/2017

Bryan Beeckman, scientific collaborator and PhD student (promoter Prof Dr Bénédicte Lemmelijn, co-promoter Prof Dr Hans Ausloos) in the Research Unit Biblical Studies (Centre for Septuagint Studies and Textual Criticism), Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Sint-Michielsstraat 4 bus 3100, 3000 Leuven, Belgium, bryan.beeckman@kuleuven.be.

1 Especially the scholars Michael V. Fox and Johann Cook have given a lot of attention to the Book of Proverbs.

2 Bénédicte Lemmelijn, A Plague of Texts? A Text-Critical Study of the So-Called "PlagueNarrative" in Exodus 7, 14-11,10, OtSt 56 (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

3 Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts? 13, 22-27.

4 For these specific verses, no Dead Sea manuscripts have been found bearing witness to Prov 16:1-7. There are, however, some discoveries that have preserved other fragments of the Book of Proverbs namely "4QProv (= 4Q102), preserving parts of 1:27-2:1, and 4QProv (= 4Q103), with parts of 13:6b-9; 14:6-10; 14:31-15:8 and 15:19b-31." See Michael V. Fox, "LXX-Proverbs as a Text-Critical Resource," Text 22 (2005): 95. 4QProv can be of some interest to our analysis with regard to Prov 15:27-28 (see infra).

5 The following commentaries have been consulted: Crawford H. Toy, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Proverbs, ICC (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1959 [repr. 1899]), 319-323; Robert B. Y. Scott, Proverbs, AB 18 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965), 104-107; Bruce K. Waltke, The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 1531, NICOT (Grand Rapids, MI: Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2005), 3-15. Although the latter does not mention the text-critical problem thoroughly, it does mention the different versions of the LXX and their minuses. The other two, however, do not mention the LXX version and take MT as a starting point for their analysis.

6 See his article concerning Proverbs: Emanuel Tov, "Recensional Differences Between the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint of Proverbs," in The Greek & Hebrew Bible: Collected Essays on the Septuagint, ed. Emanuel Tov, VTSup 72 (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 419-431 (= Emanuel Tov, "Recensional Differences Between the Maso-retic Text and the Septuagint of Proverbs," in Of Scribes and Scrolls: Studies on the Hebrew Bible, Intertestamental Judaism, and Christian Origins Presented to John Strugnell on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday, ed. Harold W. Attridge, John J. Collins, and Thomas H. Tobin, CTSRR 5 [Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1990], 43-56).

7 See especially Johann Cook, "Textual Problems in the Septuagint Version of Proverbs," JNSL 26/1 (2000): 163-173.

8 Michael V. Fox, Proverbs: An Eclectic Edition with Introduction and Textual Commentary, HBCE 1 (Atlanta, GA.: SBL Press, 2015).

9 Tov, "Recensional Differences," 426.

10 Tov, "Recensional Differences," 427. See also note 13.

11 Paul de Lagarde, Anmerkungen zur Griechischen Übersetzung der Proverbien (Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1863) 51.

12 De Lagarde, Anmerkungen, loc. cit.

13 Tov, "Recensional Differences," 427. This idea is also defended by Richard Clifford who states that the "LXX is a relatively free translation of a recension different from the proto-rabbinic." See Richard J. Clifford, "Observations on the Text and Versions of Proverbs," in Wisdom, You Are My Sister: Studies in Honor of Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm., on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed. Michael L. Barré; CBQMS 29 (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1997), 55. Also see Richard J. Clifford, Proverbs: A Commentary, OTL (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999), 28: "Evidently, a different Hebrew recension of Proverbs was the basis for the Greek translation of the second century B.C.E."

14 Tov, "Recensional Differences," 427.

15 Cook, "Textual Problems," 163-173.

16 Cook, "Textual Problems," 176.

17 Cook, "Textual Problems," loc. cit.

18 Cook, "Textual Problems," 176-178.

19 Fox, Proverbs, 240.

20 Fox, Proverbs, 240-241.

21 Fox, Proverbs, 241.

22 For MT, BHS (Karl Elliger, Wilhelm Rudolph, et al., eds., Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, 5th ed., [Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 1977]) is used, and for the LXX, Rahlfs's edition (Alfred Rahlf, Septuaginta: Id est Vetus Testamentum Graece iuxta LXX Interpretes [Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2006]). With regard to the latter I want to make the remark that there is still no edition available for Proverbs in the Göttingen Septuagint Series. Peter J. Gentry is currently editing the volumes of Ecclesiastes and Proverbs for the Göttingen Septuagint Series.

23 The text from 4QProvb is taken from Emanuel Tov, et al., eds., Psalms to Chronicles, vol. 11 of Qumran Cave 4, DJD 16 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), 186.

24 Tov, Psalms to Chronicles, 183. For a full overview of the text see pp. 184-186.

25 We will not examine the MT version of 16:9, which would lead us too far astray.

26 Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts? 219.

27 See Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts?, 33-34.

28 Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts?, 33.

29 Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts?, 34.

30 'Αποκαθαίροντω occurs four times in the LXX: Tob 12:9; Prov 15:27; Job 7:9; Job 9:30.

31 This translation ("to become friends") is based upon the NETS-translation of Proverbs made by Johann Cook. See Johann Cook, "Proverbs," in A New English Translation of the Septuagint and the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included under that Title, ed. Albert Pietersma and Benjamin G. Wright (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 635.

32 Cook, "Proverbs," 635.

33 See Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts?, 96.

34 By "translation technique," we refer to the way(s) in which the translator translated his Hebrew Vorlage. However, this does not imply that the translator consciously used one specific technique. By using this definition of translation technique, we follow the "Finnish school" where Anneli Aejmelaeus plays an important role. In her article "What We Talk about when We Talk about Translation Technique" she states what she understands under the term "translation technique": "I suggest that 'translation technique' be understood as simply designating the relationship between the text of the translation and its Vorlage. What is needed is a neutral term to denote the activity of the translator or the process of translation that led from the Vorlage to the translation, and I think that the term 'translation technique' actually suits this purpose very well. But 'translation technique' should not be thought of as a system acquired or developed or resorted to by the translators," See Anneli Aejmelaeus, "What We Talk About When We Talk About Translation Technique," in On the Trail of the Septua-gint Translators: Collected Essays, ed. Anneli Aejmelaeus, CBET 50 (Leuven, MA: Peeters, 2007), 205-206 (= Anneli Aejmelaeus, "What We Talk About When We Talk About Translation Technique," in X Congress of the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies. Oslo, 1998, ed. Bernard A. Taylor, SBLSCS 51 [Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2001], 531-552). In German, the neutral word "Übersetzungsweise" is used to refer to "translation technique." Aejmelaeus has borrowed this term from her teacher, Soisalon-Soininen. See Aejmelaeus, "What We Talk About," 205.

35 See Johann Cook, "Translation Technique and the Reconstruction of Texts," OTE 21/1 (2008): 63: "[... ] [I]ts translation technique can be defined as extremely free in some instances"; Cook, "Proverbs," 621: "Elsewhere, I have characterized its modus operandi as often extremely free, while in other cases the parent text was rendered in a rather literal way"; Johann Cook, The Septuagint of Proverbs: Jewish and/or Hellenistic Proverbs? Concerning the Hellenistic Colouring of LXX Proverbs, VTSup 69 (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 319: "He has a clearly defined approach towards his parent text which, in terms of my analysis of his translation technique, has to be described as a free rendering of his parent text"; Emanuel Tov, "A Textual-Exegetical Commentary on Three Chapters in the Septuagint," in Scripture in Transition: Essays on Septua-gint, Hebrew Bible, and Dead Sea Scrolls in Honour of Raija Sollamo, ed. Anssi Voitila and Jutta Jokiranta, JSJSup 126 (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 276: "The LXX translation provides a free and often paraphrastic translation of its Hebrew parent text [...]"; Fox, "LXX-Proverbs," 95-128, and more specifically Johann Cook, "The Dating of Septuagint Proverbs," ETL 69/4 (1993): 388: "There is a general consensus that Sep-tuagint Proverbs represents a rather free translation unit." Although the general consensus is that it is a free translation, Theo A. W. van der Louw has argued that a "literal translation constitutes the backbone" of the LXX Proverbs. Theo A. W. van der Louw, "Transformations in the Septuagint: Towards an Interaction of Septuagint Studies and Translation Studies" (Ph.D. diss., Leiden, 2006), 276 (= Theo A. W. van der Louw, Transformations in the Septuagint: Towards an Interaction of Septuagint Studies and Translation Studies, CBET 47 (Leuven, MA; Peeters, 2007).

36 Lemmelijn, Plague of Texts? 114, n. 83. On the faithfulness of a translation see Anneli Aejmelaeus, "The Significance of Clause Connectors in the Syntactical and Translation-Technical Study of the Septuagint," in On the Trail of the Septuagint Translators: Collected Essays, ed. Anneli Aejmelaeus, CBET 50 (Leuven; Peeters, 2007), 278: "Changing the structure of a clause or a phrase, and by so doing replacing an un-Greek expression by a genuine Greek one closely corresponding to the meaning of the original, is quite a different thing from being recklessly free and paying less attention to the correspondence with the original. A distinction should be made between literalness and faithfulness. A good free rendering is a faithful rendering"; Ilmari Soisalon-Soininen, "Die Auslassung des Possessivpronomens im griechischen Pentateuch," in Studien zur Septuaginta-Syntax, ed. Ilmari Soisalon-Soininen, Anneli Aemelaeus, and Raija Sollamo, AASF B/237 (Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1987), 88: "Sie haben den Text möglichst getreu wiedergeben wollen, nicht aber wortwörtlich [...]." In this context, Bénédicte Lemmelijn and Hans Ausloos have introduced a new category that goes beyond faithfulness i.e. creativity. See also Hans Ausloos and Bénédicte Lemmelijn, "Faithful Creativity Torn between Freedom and Literalness in the Septuagint's Translations," JNSL 40 (2014): 59-62. This creativity becomes evident in a "content- and context-related" approach (based upon content-and context-related criteria such as Hebrew wordplay in the context of parallelism, Hebrew absolute hapax legomena, and Hebrew wordplay in the context of aetiologies), which can be seen as "an artificially created laboratory situation in which a specific test is set up in order to elicit a reaction." Cf. Ausloos and Lemmelijn, "Faithful Creativity," 62-63. The way in which the LXX translator dealt with these difficult situations can, sometimes, be seen as being very creative. An example of a creative translator can be found in Proverbs, see Ausloos and Lemmelijn, "Faithful Creativity," 64-66.

37 Cook argues that LXX Proverbs, as well as LXX Job, is less faithful to his Hebrew Vorlage, Johann Cook, "Were the LXX Versions of Proverbs and Job Translated by the Same Person?," HS 51 (2010): 134: "It should be clear that both LXX Proverbs and Job are less faithfully translated units." There are some scholars who have underlined the faithful character of the translation. See, e.g., Fox, "LXX-Proverbs," 95-96: "Still, the freedoms the translator takes are not anarchic, and when he has the MT or something like it, he almost always tries to address its essential meaning as he understands it," and Bénédicte Lemmelijn, "The Greek Rendering of Hebrew Hapax Legomena in LXX Proverbs and Job: A Clue to the Question of a Single Translator?," in In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes: Studies in the Biblical Text in Honour of Anneli Aejmelaeus, ed. T. Michael Law, Kristin De Troyer, and Market-ta Liljeström, CBET 72 (Leuven: Peeters, 2014), 149: "However, we have repeatedly observed that his translation in Prov 4:24, even though not 'literal,' remains very 'faithful.'"

38 According to Fox, this "refinement" of words is a typical characteristic of the LXX-translator of Proverbs. See Fox, Proverbs, 45-46.

39 According to Cook, contrasting is a typical characteristic of the translation technique of the translator of LXX-Proverbs. See Johann Cook, "Contrasting as a Translation Technique in the LXX of Proverbs," in The Quest for Context and Meaning: Studies in Biblical Intertextuality in Honor of James A. Sanders, ed. Craig A. Evans and Shemaryahu Talmon (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 403-14.

40 See Bryan Beeckman, "Voorbij vergeving? Een introductie in het boek Spreuken," Ezra 32 (2016): 115-118.

41 The enhancement of parallelism by the LXX-translator is something that is typical of the LXX version of Proverbs. See Fox, Proverbs, 52-54.

42 Cf. n. 36.

43 The word ακάθαρτος occurs 5 times in Proverbs (Prov 3:32; 16:5; 17:15; 20:10 and 21:15). In 4 of them it is used as an equivalent of the Hebrew word תּוֹעֵבָה, i.e. in Prov 3:32; 16:5; 17:15; and 20:10. See Edwin Hatch and Henry A. Redpath, A Concordance to the Septuagint and other Greek Versions of the Old Testament (including the Apocryphal Books) (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1998).

44 My own translation.

45 Cook, Septuagint of Proverbs, 635.

46 Ruth Scoralick agrees on the fact that the LXX translator was a kind of poet who tried to enhance the poetical structure of the text. See Ruth Scoralick, "Salomos griechische Gewänder: Beobachtungen zur Septuagintafassung des Sprichwörterbuches," in Rettendes Wissen: Studien zum Fortgang weisheitlichen Denkens im Frühjudentum und im frühen Christentum, ed. Karl Löning and Martin Faßnacht, AOAT 300 (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2002), 72: "Der Verfasser der griechischen Übersetzung tritt uns in all den genannten Beispielen als ein poetisch begabter Gelehrter gegenüber, der erstaunlich frei mit dem Text umgeht, gleichzeitig jedoch in den meisten Fällen die Aussagen und Orientierungen des hebräischen Textes zum Leitfaden nimmt."

47 See Tov, "Recensional Differences," 431. It seems to me that Tov, when using the word "recension," sees the LXX version as a revision/reworking (which carries a rather negative connotation) of the, according to him, original Hebrew text, which would be attested in MT. In my view, this thesis can no longer be maintained. I would like to argue for different versions of the text that existed next to the each other and were of equal value. I want to consider all the textual witnesses as valuable witnesses since the different manuscripts can no longer be seen as deviations or errors from their "original." See e.g., Bénédicte Lemmelijn, "Textual Criticism," in Oxford Handbook of the Septuagint, ed. Alison G. Salvesen and T. Michael Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

48 See Lemmelijn, "Textual Criticism," 431; Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis, MN.: Fortress Press / Assen: Royal Van Gorcum, 1992), 337.

49 See Tov, "Recensional Differences," 431.

50 See Scoralick, "Salomos griechische Gewänder," 58: "Eine abweichende hebräische Vorlage, die für heute in keiner Weise (außer durch die Septuaginta) mehr greifbar wäre, ist demgegenüber die unwahrscheinlichere Annahme."

51 See Scoralick, "Salomos griechische Gewänder," 59: "Nach meiner Analyse sind sowohl der hebräische als auch der griechische Text planvoll angeordnet [.]. Der Septuagintatext weist dabei Gestaltungsprinzipien auf, die nur in der griechischen Fassung des Sprichwörterbuches möglich sind, insofern [sie] auf eine kreative Eigenleistung des Übersetzers hindeuten und die Annahme einer nicht überlieferten hebräischen Vorlage unwahrscheinlich machen."

52 See e.g. Johann Cook, "The Greek of Proverbs: Evidence of a Recensionally Deviating Hebrew Text?," in Emanuel: Studies in Hebrew Bible, Septuagint, and Dead Sea Scrolls in Honor of Emanuel Tov, ed. Shalom M. Paul, et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 618; Johann Cook and Arie van der Kooij, Law, Prophets, and Wisdom: On the Provenance of Translators and their Books in the Septuagint Version, CBET 68 (Leuven: Peeters, 2012), 91, 94 and 105; Johann Cook, "'ishah zarah (Proverbs 1-9 Septuagint): A Metaphor for Foreign Wisdom?" ZAW 106/3 (1994): 460; Johann Cook, "The Translator of the Septuagint of Proverbs: Is his Style the Result of Platonic and/or Stoic Influence?" in Die Septuaginta: Texte, Kontexte, Lebenswelten, ed. Jan C. Gertz, WUNT 219 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008), 547.

53 See Cook, "Contrasting," 412.

54 These transpositions are not only observed in chs. 15 and 16, but also elsewhere, e.g. the difference in chs. 25-31 (LXX: 31:1-9; 25:1-29:27; 31:10-31).

55 So far no research has been done concerning the way on how the LXX-translators translated their Vorlage and on how this Vorlage physically looked like. Nevertheless, some historical research has been performed on the material and the position the scribes and copyists used in Antiquity. Scholars of the field of the Synoptic Problem have integrated these results in their research. See, e.g., Robert A. Derrenbacker, Ancient Compositional Practices and the Synoptic Problem (Leuven: Peeters, 2005), 30-39; Eric C. S. Eve, "The Synoptic Problem Without Q?" in New Studies in the Synoptic Problem: Oxford conference, April 2008: Essays in Honour of Christopher M. Tuckett, ed. Paul Foster, et al., BETL 239 (Leuven: Peeters, 2011), 565-569.

56 See Derrenbacker, Ancient Compositional, 31: "[...] [A] 'book roll' or scroll allowed the reader continuous or sequential access (as opposed to random access) to a particular document, with its design being most conducive to start-to-finish reading." Codices, in the contrary, lent themselves perfectly to a random reading of a text. These codices were, however, only introduced in the first centuries A.D. after the LXX was written. See Derrenbacker, Ancient Compositional, 32.