Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 n.2 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n2a14

Figuring out Cain: Darwin, Spangenberg, and Cormon1

Gerrie F. Snyman

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

This essay responds to a question Prof. I. J. J. (Sakkie) Spangenberg asked the author at the 2015 meeting of the OTSSA with regard to the use of the OT in current South African discourse. It pertained to the use of an OT text in a context that is historically and culturally removed from the story: why is the figure of Cain used to illustrate perpetrator discourse in postapartheid society? The author argues that the figure of Cain draws, on the one hand, attention to the responsibility of South African whiteness towards apartheid and its after effects, and explores, on the other hand, the respons(e)-ability of ordinary (white) Bible readers in this regard. There are good reasons or warrants for focusing on Cain as perpetrator by accepting or adhering to the advice fostered by post-Holocaust hermeneutics in Germany as well as by criticism of archetypal myths in the cultural archive. In framing this responsibility and respons(e)-ability, a brief discussion of the German socio-political and religious discourse after the Holocaust and its relevance for thinking about Cain is provided, followed by an exploration of the value of Cain as an archetype in the cultural archive. Lastly, the essay will analyze Fernand Cormon's painting, Cain (1880) as part of the cultural archive in order to function as a heuristic key to interrogate evil and understand the figure of Cain.

Keywords: Cain; evil; Hannah Arendt; Holocaust; apartheid; Cormon; Spangenberg.

A INTRODUCTION

At the annual OTSSA meeting in September 2015, in response to my paper "A Hermeneutic of Vulnerability: Redeeming Cain?"2 Sakkie Spangenberg asked me why I use the figure of Cain to illustrate perpetrator discourse. His question relates to the impact the OT might have on values in the current South African context, especially with regard to ecology, sexism, homophobia, and racism.3

His question was a caution to remember that the OT's context and narratives differ from our (postapartheid) context and the stories we tell. The human prism is of considerable importance, not only in terms of the text that testifies to experiences but also in terms of the reader who acknowledges those experiences embedded in the ancient text. These experiences provided the ancient original community with a particular wisdom that later reading communities cannot ignore even if that wisdom appears strange to them. The importance of the human voice in these stories does not make them incompatible with and incomparable to other stories or other ancient myths in the literary canons, nor does it invalidate the divine. However, the human element in these ancient stories enables connection between later readers and ancient communities. The prism with which these stories were once conceived and then read by consecutive reading communities, is human and by no means sui generis. Thus, the values expressed in these stories need to be weighed and measured against contemporary values in society. Moreover, one can only look at the theological justification of apartheid to realise the problematic nature of the process in which values found in the biblical text have been applied in a context that differed in time and space.4 The human voice in the text enables readers to identify with the characters and to understand the context in which they acted. Many approaches provided by methodologies of literature in general, for example narrative techniques, empower readers to identify with the story and characters, be it admiration, association, irony, sympathy or catharsis.

My initial answer to Spangenberg's question was that the context in which the paper was conceived, written, and delivered was the academic community of OT Studies in South Africa. But that was an impulsive answer delivered on the spur of the moment, and his question nonetheless urged me to think about the ethics behind my interpretation of Cain and vulnerability.

Spangenberg's question subsumed three implied queries: does the use of the figure of Cain in a discussion on redemption of perpetrators of apartheid imply a particular understanding of the biblical text as divinely inspired text? If not, why then use Cain at all in such a discussion? In other words, what does Cain provide what others cannot? Lastly, why the focus on the perpetrator and not the victim? After all, Abel is completely silent in the story. By giving attention to Cain as perpetrator and linking it up to perpetrators of apartheid or racism, do I not put the focus yet again on those who are usually the center of attention, namely those in and with power? Perhaps. However, looking at one self in the mirror with regard to perpetration requires serious introspection. It is part of coming to consciousness of oneself as white, an embarrassing process.5

My focus on the figure of Cain intends drawing attention to the responsibility of South African whiteness towards apartheid and its after effects and to explore the respons(e)-ability of ordinary (white) Bible readers in this regard. Responsibility is framed within the notion of an ethics of interpretation, denoting the reader's responsibility for the effect his or her reading would have on other people as well as a responsibility towards the text in terms of a reading that would be doing justice to the text.6 Respons(e)-ability relates to the obligation on readers to be responsible and to readers specifically within the sphere of South African whiteness to accept responsibility for the apartheid past. Reading Cain would be an enabling step in fostering such responsibility.7

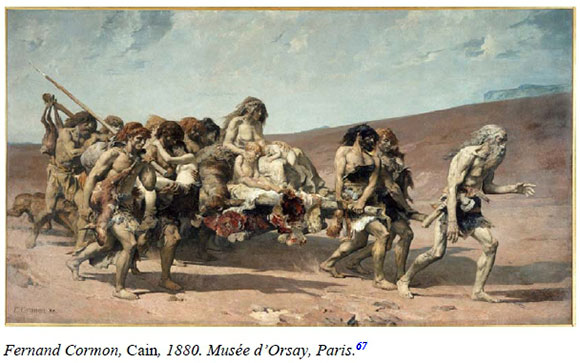

To assume such responsibility and respons(e)-ability is very difficult, given the history of reception of Cain in the Judeo-Christian tradition. In his underscoring of evolution, Spangenberg pleads for a new narrative that recognises the cycle of life on earth.8 I think Fernand Cormon's painting, Cain (1880), which portrays Cain and his tribe in terms of the stages of evolution, shocking for the day, provides such a new context for the story, one with a glimmer of hope and redemption amidst hardship in lieu of rejection and punishment.

There are good reasons or warrants for focusing on Cain as perpetrator by listening to and accepting the advice fostered firstly by postholocaust hermeneutics in Germany and secondly by criticism of archetypal myths in the cultural archive. In framing this responsibility and respons(e)-ability, firstly a leaf is taken from the German socio-political and religious discourse in the third generation after the Holocaust. Secondly, the essay inquires into the value of Cain as archetype in the cultural archive. Thirdly, it will utilise as a heuristic key Fernand Cormon's Cain as part of the cultural archive.

B POST-HOLOCAUST HERMENEUTICS

The project of focusing on Cain in a discussion on whiteness and decoloniality finds an affirmation in what is happening currently within German political culture in their dealing with the Holocaust. I discovered a particular echo with Katharina von Kellenbach's book, The Mark of Cain: Guilt and Denial in the Post-War Lives of Nazi Perpetrators (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), in which she finds a structural resonance between Cain and Germany's struggle to come to terms with the past. She argues that Germany accepted itself as a perpetrator nation, enabling subsequent recognitions of moral obligations of repair and financial restitution, creating a process that has not yet finished.9 She finds a matching parallel in the story of Cain: his process of redemption takes place over a lifetime in which he had to learn to carry his guilt and impute lessons to his family with the mark given to him as a sign of grace. Von Kellenbach states: "There are no quick solutions but a multitude of daily interactions and practices of small steps that change perspectives, modify attitudes, and repair relationships."10 The German recovery of National Socialism, in turn, was a process that happened over a long time, involving retributive justice and reintegration as well as disempowering old ideologies.

In South Africa a new government introduced certain retributive measures since 1994, but the reintegration of whiteness within Africa failed. Old ideologies appear to have a continuous life if one judges the ongoing revelations of racist episodes within the white communities. I cringe at the exposure of these episodes, but I have to admit also that it creates a level of transparency.11 Why looking at Germany's postholocaust recovery? The issue here is not a comparison between the Holocaust and apartheid, but rather the recognition of a common cultural archive on the basis of coloniality as a phenomenon within modernity. The structural resonance between postapartheid South Africa and postholocaust Germany is on the level of the community of perpetrators. In both instances, the perpetrators were not removed from society, but reinstated and allowed to live their own lives. Nevertheless, in Germany in particular, perpetrators were obliged to recognise the atrocities of the past as well as the persistent presence of those ideologies that enabled them.

With perpetrators I do not necessarily single out those individuals who committed atrocities; I have in mind the general population of the time in whose midst these perpetrators could live and prosper; a population that voted for the racial policies of the National Party; a God-fearing population who justified apartheid theologically, at least within the Afrikaans Reformed traditions. The notion of perpetrator I have in mind links up more with corporateness, a collectivity of wrongdoing, than with individuals.12 The nature of collective evil sanctions the absence of personal conscience by bringing into the fold collective cohesion and corporate identity. Ideology replaces moral agency, blocking any awareness of humanity. It is a deliberate abdication of personal responsibility and the negation of individual choice.

Within corporateness the perpetrator acts on behalf of the rest, giving preference to his or her relationship to the group whilst denying any relation with the victim. Thus, in wrongdoing, there is no individual evil intent whereas the evil wrongdoing took place within a collectivity in pursuit of an ideology that ultimately dehumanised others. Von Kellenbach refers to Hannah Arendt's likening of evil to fungus: "Evil possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus."13 For example, with regard to Rudolph Eichmann, Hannah Arendt was struck "by a manifest shallowness in the doer that made it impossible to trace the uncontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives."14 She thought his deeds were horrific, but Eichmann, the perpetrator was "quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous."15

Committing evil does not require thinking, argues Vetlesen:

[W]hat I take to have puzzled Arendt so much, is the blatant dissymmetry between the deed and (one of) the doers. Banal men, men with banal motives, can perfectly well commit radical evil.16

In other words, in contrast to the idea that evil is the product of strong negative urges or desires such as envy, hatred, vanity and determination, evil as banal does not originate from dark passions as Early Christianity portrayed Cain.17 Eichmann's banality resides in his ordinariness, not being special or of a specific social rank - simply the average person who idolised Hitler.

Arendt did not regard Eichmann to be a monster; it was more difficult for her not to see him as a clown. It was hard to take him seriously,18 but Arendt sees in him a perfect example of how long it took "an average person to overcome his innate repugnance toward crime, and what exactly happens to him once he reached that point."19 He is an example of moral collapse within European society in order to achieve success, a zeal and eagerness he saw in the society around him. He heard the respectable voice of society and his conscience responded accordingly. He did not hear the opposing voices seeking to restrain him.20 Arendt ascribes to him the sensibility of Pontius Pilate:

whatever he did he did, as far as he could see, as a law-abiding citizen. He did his duty, as he told the police and the court over and over again; he not only obeyed orders, he also obeyed the law. ... Eichmann, with his rather modest mental gifts, was certainly the last man in the courtroom to be expected to challenge these notions and to strike out on his own.21

Arendt shows how Eichmann distorted Kantian principles to the point of a particular helplessness in which moral judgment is suspended: "a law was a law, and there could be no exceptions."22 His guilt was his obedience, and obedience was regarded as a virtue.23 In the end, his own will became identified with the principle behind the law, allowing him to simply do his duty without any faculty of moral judgment. He was a victim, and his superiors were the criminals. Their law of conscience (in Hitler's regime) was "Thou shalt kill," but Arendt thinks Eichmann and others knew very well that murder was against the normal desires and inclination of those around them. To Arendt evil lost its quality of temptation, so much so that people rather had the temptation not to murder, but they found a way to resist that temptation.24

Eichmann is for Arendt a "lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil."25 She says:

The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together, for it implied ... that this new type of criminal, who is in actual fact hostis generis humani, commits his crimes under circumstances that makes well-nigh impossible for him to know or to feel that he is doing wrong.26

The banality of evil failed to address Eichmann's conscience. Similarly, the banality of apartheid obscured reflection on fundamental human rights.27 Apartheid allowed ordinary people to see racial discrimination at work without appealing to their conscience.

Von Kellenbach argues, "the experience of those guilty of participation in atrocities suggests that we need new stories to think about the mechanisms of deliverance from evil."28 With her exploration in the Cain and Abel story,29Von Kellenbach remains within the Judea-Christian tradition. In contrast, forgiveness and re-integration do not present itself. Cain is removed from his family and he had to build a new life: repentance is not an internal affair between the sinner and the deity, but it is moved to the public realm of conduct and communication.30 Von Kellenbach ultimately does not create a new story, but use an existing master narrative and interprets it in a new way that may provide a paradigm for Germany's struggle to come to terms with their past.

C GOOD REASONS FOR UTILISING CAIN'S STORY

In attributing ordinariness to Eichmann, Arendt took away from her Jewish compatriots and victims of the Holocaust the possibility to make evil an inherent part of Eichmann's make-up. In some Jewish interpretations of Cain, as in Targum Neofiti and Onkelos, Cain receives redemption over-against Targum Pseudo-Jonathan's vilification of Cain.31 However, he remains an archetype of evil that Von Kellenbach successfully exploits.

Therefore, one reason to focus on the story of Cain and Abel is the function of Cain as an archetype. An archetype is a recurring idea or patterns of myth and ritual in various and diverse cultures, creating similarities that reflect a set of universal patterns whose embodiment in a literary work generates an intense reaction towards the work. In other words, a sufficient amount of similar patterns in various stories to indicate a common myth or ritual constitutes an archetype.32

1 Archetype

An archetype is a primordial character (oerkarakter) who reveals certain motives and driving forces readers through the ages could identify with when they happen to be in certain circumstances. The notion of archetype is based on Jung's psychology in which archetypes represent the collective experience of humanity through the ages. They appear in myths and universal literature as well as in defined themes that readers often encounter and recognise in their own lives.33 For this reason, Bouma sees archetypes as guides or psychical energies directing one in the various phases in life.34 An archetypal narrative is based on a universal human experience that is arranged in a unique and cultural specific setting.35 The story of Cain and Abel represents one such experience: murder.

Jens de Vleminck argues as follows:

The myth of Cain and Abel is structurally embedded in human cultural history. It forms an essential part of both the Jewish-Christian and the Islamic traditions. In the holy books of the three Abrahamic religions - the Bible, the Torah, and the Koran - Cain and Abel are presented as the sons of Adam and Eve.36

To him, the beginning of human culture or civilisation is characterised by murder, a memory that is kept alive by the presence of or allusions to the Cain and Abel story in various cultures or traditions. In fact, fratricide is a central theme in the mythologies of various cultures.37 When one takes only the Western cultural tradition into consideration, the story of Cain and Abel plays a considerable role not only in theology, but also in philosophy and the visual arts: Josephus, Philo and Augustine in early Christianity, Thomas Hobbes in the 17th century, Arthur Schopenhauer in the 19th century and René Girard in the 20th century. In the visual arts there are numerous paintings, freezes and sculptures of Cain and his brother, for example the Van Eyck brothers, Tintoretto, Gustav Doré, Marc Chagall, Fernand Cormon and Henri Vidal.38 In literature William Shakespeare, Charles Baudelaire, Lord Byron, Samuel Beckett, and Harold Pinter come to mind. Cain and Abel's story is part of the Western narrative,39 and by far not always theologically interpreted.

Whereas the notion of archetype originated with Carl Jung and explored in literature by Northrop Frye and Joseph Campbell, Lipót Szondi explored Cain and Abel as archetype in psychoanalysis. The story is a leitmotiv in all his work, with the book Cain as the epitome of his thinking on this myth.40 The story reveals what it means to be human. Aggression and murder exemplify the most frightful and horrific (im)possibilities of human life. The story confronts every human being with his or her own existence, as if Cain and Abel live inside each human being.41 Szondi refers to the Cainite predisposition: the tendency to kill that is present in every human being.42 He regards it as hereditary and finds evidence in the subsequent episode with Lamech in Gen 4. He diagnoses Cain with epileptiform aggression, a form of paroxysmality indicative of murderous impulses originating from anger, hate, wrath, revenge, envy and jealousy.43 Cain becomes "the symbol of homo paroxysmalis ."44

Szondi contrasts Cain with Moses. He calls it the Mosaic disposition - a murderer making good, the desire to compensate, to repair, very much like Moses at the burning bush after he killed an Egyptian and fled to Midian (Exod 2-3).45 Moses, a murderer like Cain, becomes the founder of monotheism, argues Szondi.46 Similarly, Cain the murderer did not stay the murderer. He underwent a metamorphosis and eventually operated within what is called a cultural process of ethics by constructing culturally significant fields - arts, science and technology - through his grandchildren.47 His children and grandchildren redeemed and him restored for humanity.

Another student of Jung, Joseph Campbell, in A Hero with a Thousand Faces,48 summarises the mythical elements in a narrative as follows:

The mythological hero, setting forth from his common-day hut or castle, is lured, carried away, or else voluntarily proceeds, to the threshold of adventure. There he encounters a shadow presence that guards the passage. The hero may defeat or conciliate this power and go alive into the kingdom of the dark (brother -battle, dragon battle; offering; charm), or be slain by the opponent and descend in death (dismemberment, crucifixion). Beyond the threshold, then, the hero journeys through a world unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces, some of which severely threaten him (tests), some of which give magical aid (helpers). When he arrives at the nadir of the mythological round, he undergoes a supreme ordeal and gains his reward. His triumph may be represented as the hero's sexual union with the goddess-mother of the world (sacred marriage), his recognition by the father-creator (father atonement), his own divinization (apotheosis), or again-if the powers have remained unfriendly to him-his theft of the boon he came to gain (bride-theft, fire-theft); intrinsically it is an expansion of consciousness and therewith of being (illumination, transfiguration, freedom). The final work is that of the return. If the powers have blessed the hero, he now sets forth under their protection (emissary); if not, he flees and is pursued (transformation flight, obstacle flight). At the return threshold the transcendental powers must remain behind; the hero re-emerges from the kingdom of dread (return, resurrection). The boon that he brings restores the world (elixir).49

In the story of Cain and Abel, Cain is the perpetrator or anti-hero with Abel as victim. The story starts with Cain's origins and the proclamation by his mother that recognises his creator-father, YHWH, and not Adam. Cain receives the power of a man at his birth. He and Abel then proceed with their daily tasks, tilling the soil or herding the flock. With the offering of their sacrifices, Cain enters the kingdom of the dark with sibling rivalry a reality and fratricide a consequence as Cain invites Abel to the field. The reader finds the threshold posed to Cain in the words of the deity about sin lurking at the door and Cain desperately in need of mastering evil desire. He fails and cannot stay under the protection of the deity. His punishment, in contrast to the boon Campbell refers to, is exile: Cain becomes a wandering fugitive. There is no blessing but a curse. However, he is not persecuted and receives a mark as protection. The action in the narrative then stops and Cain re-emerges in the genealogy of Adam. Cain returns, if not physically, by way of memory and as part of Adam's descendants. In addition, it is in this return that one sees a blessing: his children and grandchildren are associated with civilisation: establishing of a city, arts, culture and technology. The re-emergence of Cain within memory, with a genealogy and a statement about achievements becomes a sign of redemption and Cain's rehabilitation into society.

Cain in the Cain and Abel story or myth-complex becomes an archetype for evil and sibling rivalry that plays out in different interpretations, each time reflecting a particular concern that the context has generated. In most interpretations he will be the perpetrator.50

2 Cultural Archive

Stories about murder and fratricide are part of the current cultural archive. A cultural archive, according to Gloria Wekker, is not simply documents deposited and stored in a vault, but it is a repository of memory in the heads and hearts of people (my emphasis - G.F.S.):

[T]he cultural archive is located in many things, in the way we think, do things, and look at the world, in what we find (sexually) attractive, in how our affective and rational economies are organized and intertwined. Most important, it is between our ears and in our hearts and souls.51

She employs the term with regard to colonialism, arguing that the content of the archive "is also silently cemented in policies, in organizational rules, in popular and sexual cultures, and in common sense everyday knowledge."52This cultural archive houses the construction of a European self over against others within the framework of conquest, colonisation, empire, and settlement elsewhere in that empire - the taking of a life of an other inherently present. Behind the mask of imperium, the story of Cain and Abel resonates with the experience of empire in some way or the other.53 Nevertheless, her delineation of the concept is socio-political, and when one looks at the presence of the myth of murder and fratricide in general, the cultural archive stretches much wider.

The structural resonance with the notion of story is underscored by Walter Fisher's claim that human beings are essentially storytellers.54 A human being is essentially a storytelling animal whose stories constitute enacted drama characterising human action. Life is experienced as a series of on-going narratives, or rather, symbolic actions that have meaning for those who live, create and interpret them.55 Storytelling is universal, and there are good reasons for stories being told and received, even when the telling and reception are worlds and times apart. Each good reason is produced within a historical and cultural framework. Therefore, whereas the story of Cain and Abel initially had a good reason for being told, I have a good reason for focusing on it. The story of Cain and Abel provides information on how a perpetrator is constructed, perceived and dealt with in society - a position not very different from how perpetrators are currently constructed and dealt with in terms of broader social problems such as racism, sexism, homophobia and xenophobia.

The story of Cain and Abel is not the only story featuring fratricide. The story of Romulus and Remus in the Roman mythology immediately comes to mind in terms of fratricide. Hannah Arendt, in her book On Revolution, states that something like violence to which revolution is connected, is vouched for by the beginning of history, as reported in both biblical and classical antiquity -in the secular as well as the religious (in her mind, the Judeo-Christian) world:

Cain slew Abel, and Romulus slew Remus; violence was the beginning and, by the same token, no beginning could be made without using violence, without violating. The first recorded deeds in our biblical and secular tradition, whether known to be legendary or believed in as historical fact, have travelled through the centuries with the force which human thought achieves in rare instances when it produces cogent metaphors or universally applicable tales. The tale spoke clearly: whatever brotherhood human beings may be capable of has grown out of fratricide, whatever political organization men may have achieved has its origin in crime. The conviction, In the beginning was a crime - for which phrase "state of nature" is only a theoretically purified paraphrase - has carried through the centuries no less self-evident plausibility for the state of human affairs than the first sentence of St. John, "In the beginning was the Word," has possessed for the affairs of salvation.56

Indeed, in antiquity there are quite a few stories about fratricide. In Greek mythology, Media kills her brother Apsyrtos. In Sophocles' Antigone, Eteocles and Polinysos kill each other in their succession battle to the throne. In Nordic mythology, an increase in fratricides signals the end of times. In one such myth, Hö∂r kills his brother, Baldur. In Egyptian mythology, Set murders his brother Osiris. In the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, the Pandavas kills Karna without knowing the latter is their brother. Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongolian Empire, killed his brother in a dispute.

William Hales refers to an ancient Palestinian myth that reminds one of Cain and Abel (and even Jacob and Esau) in which the two brothers, Usous and Hypsouranius, were continuously at odds with one another.57 Hypsouranius is supposed to be the originator of the art of building huts with reeds and papyrus and Usous is said to be the father of clothing with animal skins that he hunted. Their descendants resemble the offspring of Cain, Jabal, Jubal and Tubal Cain.

Three book religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam share a few stories with characters appearing in each tradition. Robert C. Gregg mentions 24 stories, including Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah, Abraham, Lot, Moses, Samuel, David and Solomon and Job. There are even stories about the prophets that are shared, for example Elijah, Elisha and Jonah. Gregg argues that although the stories are similar, their reception in each tradition differs considerably. He claims that the stories persisted, were cherished, reread and recited but were changed. "Retelling involved a great deal more than minor editorial repairs of gaps or unclear phrases." Narrators sought to discover and lay bare the multiple layers of meaning in these narratives.58

In Judaism, the rabbis concentrated on the righteousness of Abel and Cain's evil inclination.59 At issue for early Christianity were Cain's evildoing and the role of Satan, so that the interpretation of Cain rendered him fully criminal over-against Abel's total innocence and victimhood.60 In Islam, building on the Jewish and Christian traditions, at issue is whether Cain acted of free will or not, supplying readers also with a glimpse on Cain's psychological development.61

Whereas Wekker's definition of the cultural archive is limited to a specific socio-political definition, it is clear from the above that the story of Cain and Abel has generated an archive within religion, and it is comparable to Rushdie's notion of the Great Sea of stories.

3 Sea of Stories

If story is one of the fundamental forms of interpretation of experience and history, it is clear that human beings live in stories like fish in water. Salman Rushdie's notion of a sea of stories and streams within the sea of stories in his book, Haroun and the Sea of Stories,62 provides a delightful interpretation of the omnipresence of stories and different versions of a single story. The Great Sea of Stories provides the necessary story water for storytellers. Story water makes the story credible. The Great Sea of Stories consists of different currents or streams, each one representing a specific storyline. Thus, stories are in fluid form, impossible to grasp by hand, yet easy to mix with other different streams in order to create new stories. As Rushdie says, "no story comes from nowhere; new stories are born from old - it is the new combination that makes them new."63 Nonetheless, one can see traces of these story streams in a story, but it is impossible to objectify anyone of them. The presence of stories about fratricide and sibling rivalry suggests that the Mediterranean as well as the ANE somehow draw from a common source functioning as a Great Sea of Stories, perhaps at similar places and thus sharing a few common traits.

My focus on the story is warranted by the role Cain plays as an archetype of evil and by his continuous presence in cultural and religious archives. However, because his story is part of a sea of stories its utilisation always involve new elements, making it a new story in which sibling rivalry and fratricide play a role.64 Spangenberg also propagates a new narrative, but for different reasons. With a focus on new scientific discoveries and the disastrous role humanity played lately in the destruction of creation, a reading of Cain in terms of evolution theory may throw some new light on the figure of Cain. One such reading is Fernand Cormon's painting, Cain (1880), in which he represents Cain's plight as wanderer and fugitive in terms of Darwin's theory about human selection.

D FERNAND CORMON, CAIN AND EVOLUTION

Spangenberg provides three reasons for his call for a new narrative: the outdated world-view with three levels: heaven, earth and the world below; an outdated view on humans as the fallen crown of creation in need of heaven's redemption; and an outdated view on the origins of earth. Spangenberg wants to develop a new story that accounts for the latest scientific discoveries, for example evolution's idea of the cycle of life on earth of birth, growth and death.65 There is no saviour god that will redeem humankind from the misery of a destroyed and lifeless earth, but the redemption of the latter is closely linked to human actions affecting ecology. One of the outcomes of his thinking is a different role ascribed to the biblical text: a human book written by humans for humans. The formulated confessions and doctrines do not constitute universal principles for all times, but relate to specific contexts. In fact, the existence of Christianity relates to a specific context of power: it always sided with power and wealth since Theodosius' (346-395 CE) declaration of Christianity as state religion, an association that continued even during the reformation.

So why bother with Cain if the biblical text has no divine status and the traditional Christian story of fall-redemption-judgment no longer holds sway? Spangenberg claims that the ancient Israelites regarded death as a normal event in life and not the result of sin. It is unnatural when death occurs before a full life was lived.66 Here enters the story of Cain and Abel. Cain ended Abel's life. Fernand Cormon's painting Cain depicts one of the consequences of this murder: wandering in a wilderness as the earth has closed her womb to the murderer.

Hannah Arendt was castigated for her views on Eichmann because she saw him as someone quite ordinary and definitely not a deliberate evil participant in the Holocaust. Part of the Jewish tradition and the early Christian reception of Cain saw him as an unmitigated villain and evil being, rotten to the core. But there is a particular ambivalence in Cain's story. He is a murderer, yet he receives protection from the deity; he is a farmer (tiller of the soil), yet the soil will no longer yield anything to him; he is condemned to be a wanderer and a fugitive, yet he settles in the land of Nod, builds a city and procreates. He left children and grandchildren behind who would be portrayed as heroes in being linked to the foundations of arts, science and technology. Cain remained marginal, yet his descendants became central to farming, music, and the forging of weapons.

The mark Cain receives prohibits him from becoming banal. His character would serve literature, poetry, sculpture and painting with endless possibilities of presenting evil. One such artwork is the painting by Fernand Cormon, titled Cain (1880).

Besides its massive scale, the painting is remarkable for presenting a biblical myth within the framework of the discourse on evolution, with the result of connecting evil to the origins of being human - primeval becoming prime evil. Bible and evolution are usually not seen as compatible, but Cormon's portrayal of Cain in terms of evolutionary development based on Neanderthal discoveries in France may have had one unintended consequence: evil, being part of primitive beings, is also part of the earlier developments of the human race. If true, the painting would underscore colonial ideologies that relegated the indigenous peoples to lesser human beings on the scale of evolutionary development. The group of people portrayed in the painting vary slightly in terms of complexion, from darkish to the brilliant classical whiteness of the girl being carried next to the pallet.68

The painting portrays Cain and his tribe on the move. Cain is leading them, with a hand showing the way. It is as if he is resolutely walking away from where he came towards a new life. His tribe is following, emphasising the impression of movement: his wife with two children sitting on a pallet and his sons carrying the wooden structure. There is no eye contact between them, all looking blankly forward. Dogs follow the troupe and on the pallet is a carcass and pieces of meat dangling. One son carries a young girl with classical features and the man next to him carries an Iron Age spear whereas Cain carries a Stone Age axe in his belt. They are all covered with animal skins, their hair unruly and unkempt like maned lions,69 their complexions different shades - all features underscoring their savageness. It is as if they all lack humanity. At least, Cain's slouching posture reveals his lack of humanity, emphasised by his retreating forehead and protruding brow. His image creates an allusion to the anthropological drawings of apes at the time, both revealing "the same curvature of the spine, bending knees, the straight limb that hangs between the legs."70

Cormon painted at a time when the prehistoric body was a contested site. The body was thought to bear signs of human beings' changeable nature:

As the central piece of evidence in the debate on man's [sic] origins, the prehistoric body had the potential in representation to carry specific meanings, to become an index of scientific and moral view.71

The body is in flux, always in a state of formation with non-secure boundaries. Cormon's representation of the body is ideologically loaded. He deconstructs the idea of the wholeness and permanence of the classical body, exposing "the perpetual state of lack that is the nature of the evolving body."72Cormon portrays Cain in terms of primitive barbarism: with the barren landscape, ragged pelts and primitive tools or weapons, Cain and his family represents a disturbing group of people, which according to Isabelle Havet, provides an illustration of cooperation as well as humankind's violent and painful origins.73 A portrayal of the banality of violence then - perhaps, in as much they all share basic traits of the prehistoric body.

Furthermore, Cormon plays on the link his peers drew between prehistory and French (national and regional) identity. Provincial museums started to exhibit archaeological findings of ancient human settlements whereas the national exhibitions in Paris displayed France's ancient history and why the French are deemed superior to other nations.74 Add to this the publication of Darwin's The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1876 and the aftermath of the war with the Prussians that left Paris physically devastated, especially between two groups, the Communards to which Cormon belonged and Versailles' state power. Cormon's Cain would have struck a chord:

In the wake of these events, and with memories of bloody war and revolution still fresh, concerns about the material body were particularly acute. Death, suffering, and destruction were treated as tangible realities.75

The painting depicts a motley group of a few differing human beings, unified in carrying a pallet while following Cain, the obvious leader of the group. In carrying the heavy wooden structure, the group seems to display human cooperation - something particularly emphasised by Darwin: "Cooperation amongst members, ingenuity, and sympathy were key human traits ensuring sustained survival of the tribe."76 This cooperation unites everyone in the painting, from the oldest to the youngest, from the ancient to the most modern in appearance, at every stage of human evolution-from Stone Age (Cain) to Iron Age (man with spear) to contemporary age (girl with classical features). The power of the painting in terms of evolution is then also the fact that Cormon's group resembles the different stages of evolution, starting with Cain and ending with the classical features of the girl being carried. Cain's features resembled those of a tortured man, looking as if roving like a savage predator rather than fleeing the wrath of the deity, in Havet's words, vacillating between human and brute. The young girl, with her fair complexion and elegant pose, creates a stark contrast with the rest of the figures and clearly belongs to the classical period.77 Cormon's painting links up with the fascination with the prehistoric in France in the late 18th century, emerging "from the growing desire to reevaluate human history in the wake of the evolutionary paradigm, at a time when violence and depravity appeared increasingly characteristic of modern life."78

Looking at the painting in the first quarter of the 21st century, imbibed with a discourse critical of white identity because of the history of colonialism and concomitant racism, sexism and homophobia, the painting is surprisingly devoid of evil. What one sees is its after effects: complete vulnerability - evil has stripped humanity, leaving in its wake destituteness, dishevelment, displacement, insecurity, on the move towards somewhere while the earth remains inhospitable. There is no rest for a perpetrator.

E CONCLUSION

The figure of Cain remains quite powerful, and still has an impact on values in the South African context. With the help of Cormon, it is precisely in the portrayal of the different physiognomies - where Cormon departs from the story - that the impact of the story is felt: life is a struggle for survival, and evil makes it much harder. The reader of the story looking at the painting is asked to identify with the archetype - most likely in an ironic or a cathartic way, embarrassed to be associated with evil presented as an early trait from which humanity is said to have developed. The painting addresses the aftermath of the practice of evil, and with its reference to evolution, it provides another context for the story that does not have to be religious. Cormon seemed to have found in the religious archive a story stream that still had cultural impact. The story survives because of its theme of murder, rivalry and evil. The moment of wandering and becoming a fugitive the painting memorialises, addresses the sense of loss experienced within whiteness after apartheid.

To answer my colleague and friend, Prof. Sakkie Spangenberg's, question at the annual general meeting of the OTSSA in 2015, with regard to the value of using an OT text in the current South African discourse, I think there are good reasons that warrant me to follow the advice fostered in the story of Cain via the painting of Fernand Cormon. Cain helps within the German context to account for complicity with the Holocaust, three generations after the fact. Cain helps me with the embarrassment I encounter in coming to terms with the legacy of apartheid into which I was born and in which I grew up. His value to me is the process he went through, from fragility to vulnerability (the point the mentioned paper made in 2015), the latter excellently portrayed in Cormon's painting.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

About, Edmund. "Salon de 1880, May 1880: 18-19." Le XIX Siècle, May 1880, 18-19. [ Links ]

Abrams, Meyer H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1971. [ Links ]

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: The Viking Press, 1963. [ Links ]

______. On Revolution. London: Faber & Faber, 1963. [ Links ]

______. Thinking. Vol. 1 of The Life of the Mind. London: Secker & Warburg, 1978. [ Links ]

Bouma, Mieke. De 12 Oerkarakters van Storytelling: Archetypes En Hun Basisplots. Antwerpen: Atlas Contact, 2016. [ Links ]

Byron, John. Cain and Abel in Text and Tradition: Jewish and Christian Interpretations of the First Sibling Rivalry. TBN 14. Leiden: Brill, 2011. [ Links ]

Campbell, Joseph. A Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972. [ Links ]

De Vleminck, Jens. "Oedipus and Cain: Brothers in Arms." IFPs 19 (2010): 172-84. [ Links ]

______. "'In the Beginning Was the Deed.' On Oedipus and Cain." Pages 265-82 in Classical Myth and Psychoanalysis: Ancient and Modern Stories of the Self. Edited by Vanda Zajko and Ellen O'Gorman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Fisher, Walter. Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Frye, Northrop. The Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1971. [ Links ]

Gregg, Robert C. "Cain and Abel/Qabil and Habil." Pages 1-113 in Shared Stories, Rival Tellings: Early Encounters of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

______. Shared Stories, Rival Tellings: Early Encounters of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Hales, William. A New Analysis of Chronology and Geography, History and Prophecy: Their Elements Are Attempted to Be Explained, Harmonized, and Vindicated, upon Scriptural and Scientific Principles; Tending to Remove the Imperfection and Discordance of Preceding Systems, and to Obviate the Cavils of Sceptics, Jews, and Infidels. 2nd ed. 4 vols. London: C.J.G. and F. Rivington, 1830. [ Links ]

Havet, Isabelle. "Fernand Cormon's Cain: Man between Primitive and Prophet." Pages 19-40 in Picturing Evolution and Extinction: Art and Science in Republican France. Edited by Fae Brauer and Serena Keshavjee. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishers, 2016. [ Links ]

Jung, Carl G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by Richard F. C. Hull. London: Routledge, 1968. [ Links ]

Keegan, Michael. "The Banality of Evil: Lessons From South African Apartheid." The Huffington Post, December 12, 2013. Online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-b-keegan/-the-banality-of-evil-les_b_4432898.html. [ Links ]

Lucy, Martha. "Cormon's 'Cain' and the Problem of the Prehistoric Body." OAJ 25/2 (2002): 109-26. [ Links ]

Mcentire, Mark. "Cain and Abel in Africa: An Ethiopian Case Study in Competing Hermeneutics." Pages 248-59 in The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories and Trends. Edited by Gerald O. West and Musa W. Dube. Leiden: Brill, 2000. [ Links ]

Miller, Stephen. "A Note on the Banality of Evil.' Wilson 22/4 (1998): 60-64. [ Links ]

Mosala, Itumeleng. Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology in South Africa. Grand Rapids: Eerdmams, 1989. [ Links ]

Oluo, Ojeoma. "White People: I Don't Want You to Understand Me Better, I Want You to Understand Yourselves." The Establishment, February 7, 2017. Online: https://theestablishment.co/white-people-i-dont-want-you-to-understand-me-better-i-want-you-to-understand-yourselves-a6fbedd42ddf#.sot38mql8. [ Links ]

Perkinson, James W. White Theology: Outing Supremacy in Modernity. New York: Palgrave, 2004. [ Links ]

Rushdie, Salman. Haroun and the Sea of Stories. Granta Books: London, 1991. [ Links ]

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elizabeth. "The Ethics of Biblical Interpretation: Decentering Biblical Scholarship." JBL 107/1 (1988): 3-17. [ Links ]

Snyman, Gerrie F. Om die Bybel anders te lees: 'n etiek van Bybellees. Pretoria: Griffel-Media, 2007. [ Links ]

______. "The Old Testament: An Absurd Fossil or a Pool in the Great Sea of Stories?" Pages 70-88 in Old Testament Science and Reality: A Mosaic for Deist. Edited by Willie Wessels and Eben Scheffler. Pretoria: Verba Vitae, 1992. [ Links ]

______. "'Tis a Vice to Know Him': Readers' Response Ability and Responsibility in 2 Chronicles 14-16." Pages 91-114 in Bible and Ethics of Reading. Edited by Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A. Phillips. Semeia 77. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1997. [ Links ]

______. "Totius: Die Ironie van Vergewe En Vergeet." LitNetA(GW) 12/2 (2015). Online: http://www.litnet.co.za/totius-die-ironie-van-vergewe-en-vergeet/. [ Links ]

______. "A Hermeneutic of Vulnerability: Redeeming Cain?" StThJ 1/2 (2015): 633-665. Doi: 10.17570/stj.2015.v1n2.a30. [ Links ]

______. "Cain and Vulnerability: The Reception of Cain in Genesis Rabbah 22 and Targum Onkelos, Targum Neofiti and Targum Pseudo-Jonathan." OTE 29/3 (2016): 601-32. [ Links ]

Spangenberg, Izak J. J. (Sakkie). "Ses dekades Ou Testamentteologie (1952-2012): Van één spreker tot verskeie menslike sprekers." HTS 68/1 (2012). Art. #1273. 9 pages. Doi: 10.4102/hts.v68i1.1273. [ Links ]

______. "Die Tradisionele Christelike Godsdiens en Teologie in die Greep van 'n Verouderde Paradigma: Diagnose En Prognose." LitNetA(GW) 10/2 (2013). Online: http://www.litnet.co.za/die-tradisionele-christelike-godsdiens-en-teologie-in-die-greep-van-n-verouderde-paradigma/. [ Links ]

______. "On the Origin of Death: Paul and Augustine Meet Charles Darwin." HTS 69/1 (2013). Art. #1992. 8 pages. Doi: 10.4102/hts.v69i1.1992. [ Links ]

______."Die 'vergroening' van die Christelike godsdiens: Charles Darwin, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin en Lloyd Geering." HTS 70/1 (2014). Art. #2712. 9 pages. Doi: 10.4102/ hts.v70i1.2712. [ Links ]

______."Kollig op Genesis 1-3: Verslag van verskuiwende denke en geloof." OTE 27/2 (2014): 612-636. [ Links ]

Szondi, Lipót (Leopoldt). Kain: Gestalten Des Bösen. Bern: Hans Huber, 1969. [ Links ]

Szondi, Lipót (Leopoldt) and Claude Van Reeth. "Thanatos et Caïn: Au Commencement de La Culture." RPL 68/99 (1970): 373-84. Doi: 10.3406/phlou.1970.5562. [ Links ]

Vetlesen, Arne J. "Hannah Arendt on Conscience and Evil." PSC 27/7 (2001): 1-33. [ Links ]

Von Kellenbach, Katharina. The Mark of Cain: Guilt and Denial in the Post-War Lives of Nazi Perpetrators. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Wekker, Gloria. White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 7/03/2017

Peer-reviewed: 1/05/2017

Accepted: 17/05/2017

Prof. Gerrie F. Snyman is a Professor in OT at the Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies at the University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: snymagf@unisa.ac.za.

1 This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant specific unique reference number [UID] 85867).

2 Gerrie F. Snyman, "A Hermeneutic of Vulnerability: Redeeming Cain?" StThJ 1/2 (2015): 633-665, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2015.v1n2.a30.

3 Izak J. J. (Sakkie) Spangenberg, "Die tradisionele Christelike godsdiens en teologie in die greep van 'n verouderde paradigma: Diagnose en prognose," LitNetA(GW) 10 (2013), online: http://www.litnet.co.za/die-tradisionele-christelike-godsdiens-en-teologie-in-die-greep-van-n-verouderde-paradigma/; Izak J. J. (Sakkie) Spangenberg, "Die 'vergroening' van die Christelike godsdiens: Charles Darwin, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin en Lloyd Geering," HTS 70 (2014), Art. #2712, 9 pages, doi: 10.4102/hts.v70i1.2712; Izak J. J. (Sakkie) Spangenberg, "Kollig op Genesis 1-3: Verslag van verskuiwende denke en geloof," OTE 27 (2014): 612-636; and Izak J. J. (Sakkie) Spangenberg, "Ses dekades Ou Testamentteologie (1952-2012): Van één spreker tot verskeie menslike sprekers," HTS 68 (2012), Art. #1273, 9 pages, doi: 10.4102/hts.v68i1.1273.

4 Gerrie F. Snyman,"Totius: Die ironie van vergewe en vergeet," LitNetA(GW) 12/2 (2015), online: http://www.litnet.co.za/totius-die-ironie-van-vergewe-en-vergeet/.

5 See James W. Perkinson, White Theology: Outing Supremacy in Modernity (New York: Palgrave, 2004), 3. See also Ojeoma Oluo, "White People: I Don't Want You To Understand Me Better, I Want You To Understand Yourselves," The Establishment, February 7, 2017, online: https://theestablishment.co/white-people-i-dont-want-you-to-understand-me-better-i-want-you-to-understand-yourselves-a6fbedd42ddf#.sot38mql8.

6 See Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, "The Ethics of Biblical Interpretation: Decentering Biblical Scholarship," JBL 107 (1988): 3-17; and Gerrie F. Snyman, Om die Bybel anders te lees: 'n etiek van Bybellees (Pretoria: Griffel-Media, 2007).

7 Gerrie F. Snyman, "'Tis a Vice to Know Him': Readers' Response Ability and Responsibility in 2 Chronicles 14-16," in Bible and Ethics of Reading, ed. Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A. Phillips, Semeia 77 (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1997), 91-114.

8 Spangenberg, "Die 'vergroening,'" 3.

9 Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 22.

10 Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 22.

11 Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 23. She argues that the hiddenness of guilt adds to the burden society carries, even to the point of paralysis. The moment wrongdoing is acknowledged, its recollection loses power to disturb and to shock.

12 See Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 16-17. She stresses that one should not think of collective wrongdoing in terms of individual person-to-person acts based on greed, hatred, or lust. The latter terms refer to criminality whereas with collective evil the agent sees himself or herself as an agent of the group.

13 Hannah Arendt in Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 17.

14 Hannah Arendt, Thinking, vol. 1 of The Life of the Mind, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1978), 9. See also Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 126-7.

15 Arendt, Thinking, 9.

16 Arne J. Vetlesen, "Hannah Arendt on Conscience and Evil," PSC 27/5 (2001): 7-8 argues that she draws a link between thinking and moral good, turning Eichmann's evil into not thinking, whilst his evil could also be due to lack of empathy.

17 Stephen Miller, "A Note on the Banality of Evil," Wilson 22/4 (1998): 64. Miller critiques her idea of banality, arguing the word relates to ideas and not to acts or facts.

18 Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (New York: The Viking Press, 1963), 54: "For all this, it was essential that one take him seriously, and this was very hard to do, unless one sought the easiest way out of the dilemma between the unspeakable horror of the deeds and the undeniable ludicrousness of the man who perpetrated them, and declared him a clever, calculating liar-which he obviously was not."

19 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 93.

20 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 122.

21 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 135.

22 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 137.

23 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 247.

24 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 150.

25 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 252.

26 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 276.

27 See Michael Keegan, "The Banality of Evil: Lessons from South African Apartheid," The Huffington Post, 12 December 2013, online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-b-keegan/-the-banality-of-evil-les_b_4432898.html.

28 Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 20.

29 She considered the parable of the prodigal son in the NT. The point of the parable is the prodigal son receiving redemption from the father when asked for forgiveness. He admitted his wrongdoing, but to Von Kellenbach Nazi perpetrators seldom admitted wrongdoing, making the parable ineffective for a post-Holocaust paradigm to reintegrate perpetrators.

30 Von Kellenbach, Mark of Cain, 22.

31 Gerrie F. Snyman, "Cain and Vulnerability: The Reception of Cain in Genesis Rabbah 22 and Targum Onkelos, Targum Neofiti and Targum Pseudo-Jonathan," OTE 29 (2016): 601-632.

32 Meyer H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1971), 11; Northrop Frye, The Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1971) developed a form of archetypal criticism that boils down to an analysis of mythical patterns.

33 Carl G. Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, trans. Richard F. C.Hull (Routledge: London, 1968).

34 Mieke Bouma, De 12 Oerkarakters van Storytelling: Archetypes en hun Basisplots (Antwerpen: Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, 2016). Bouma distinguishes 12 primordial characters: the unprejudiced child, the orphan, the warrior, the nurse, the fortune seeker, the provoker, the loved one, the artist, the king, the wise being, the magician and the joker.

35 Bouma, Oerkarakters, 47.

36 Jens de Vleminck, "Oedipus and Cain: Brothers in Arms," IFPs 19 (2010): 174.

37 De Vleminck, "Oedipus and Cain," 175. He refers to the Shun and Yao in Chinese, Ahriman and Ahura Mazda in the Persian traditions, Seth and Osiris in Egyptian culture, Roman and Romulus in Roman culture and Eteocles and Polinysos in Greek culture. The Dinka in Southern Sudan attributes the split of the human and the divine to tribal fratricidal conflicts.

38 Art Resources (http://www.artres.com), a website storing high quality images of works of painting, sculpture, architecture and the minor arts from most of the world's major museums, monuments, and commercial archives, has about 150 images of various art works on the subject of Cain and Abel.

39 A gap in our understanding of Cain in Abel in various African contexts reveals itself in searches for literature on African readings of the story. They exist (for example Boesak, Mosala and Oduyoye, see Mark Mcentire, "Cain and Abel in Africa: An Ethiopian Case Study in Competing Hermeneutics," in The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories and Trends, ed. Gerald O. West and Musa W. Dube, [Leiden: Brill, 2000], 248-59), but I suspect a lot of readings have not yet become metadata for online searches.

40 Lipót (Leopoldt) Szondi, Kain: Gestalten des Bösen (Bern: Hans Huber, 1969). For a palatable rendering of his argument for non-psychoanalytics, see Lipót (Leopoldt) Szondi and Claude van Reeth, "Thanatos et Caïn: Au commencement de la culture," RPL 68/99 (1970): 373-384, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/phlou.1970.5562.

41 Jens de Vleminck, "'In the Beginning was the Deed': On Oedipus and Cain," in Classical Myth and Psychoanalysis: Ancient and Modern Stories of the Self, ed. Vanda Zajko and Ellen O'Gorman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 277.

42 Szondi and Van Reeth, "Thanatos et Caïn," 375.

43 Szondi and Van Reeth, "Thanatos et Caïn," 381. See De Vleminck, "'In the Beginning was the Deed,'" 276.

44 De Vleminck, "'In the Beginning was the Deed,'" 277.

45 Szondi and Van Reeth, "Thanatos et Caïn," 382.

46 Szondi and Van Reeth, "Thanatos et Caïn," 383.

47 Szondi and Van Reeth, "Thanatos et Caïn," 383 calls them the factors of aggression, anger, devalorization and detachment.

48 Joseph Campbell, A Hero with a Thousand Faces (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1972), 227-228.

49 Campbell, A Hero, 227-228.

50 I have encounter Cain as a victim only in one reading, namely that of Itumeleng Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology in South Africa (Grand Rapids: Eerdmams, 1989), 33-37.

51 Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 19.

52 Wekker, White Innocence, 19.

53 See Snyman, "Hermeneutic of Vulnerability."

54 Walter Fisher, Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1987), 24.

55 Fisher, Human Communication, 58.

56 Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (Faber and Faber: London, 1963), 11.

57 William Hales, A New Analysis of Chronology and Geography, History and Prophecy: Their Elements are Attempted to Be Explained, Harmonized, and Vindicated, upon Scriptural and Scientific Principles; Tending to Remove the Imperfection and Discordance of Preceding Systems, and to Obviate the Cavils of Sceptics, Jews, and Infidels, 4 vols., 2nd ed. (CJG and F. Rivington: London, 1830), 4-5. It is preserved in Philo's Greek translation of Sanchuniathon's Phoenician History.

58 Robert C. Gregg, Shared Stories, Rival Tellings: Early Encounters of Jews, Christians, and Muslims (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), xv.

59 See Snyman, "Cain and Vulnerability," 601-632.

60 Cf. John Byron, Cain and Abel in Text and Tradition: Jewish and Christian Interpretations of the First Sibling Rivalry, TBN 14 (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

61 See Gregg, Shared Stories, 75-113. He refers to the story in Surah Al-Ma'idah, Al-Tabari's History of Prophets and Kings, Al-Tha 'Labi's Lives of the Prophets; and paintings in Abu Rayhan al-Biruni's Chronology of the Ancient nations and in al-Tha-'Labi's Qisas al-Anbiya.'

62 Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories (Granta Books: London, 1991).

63 Rushdie, Haroun, 86. See also Gerrie Snyman, "The Old Testament: An Absurd Fossil or a Pool in the Great Sea of Stories?" in Old Testament Science and Reality: A Mosaic for Deist, ed. Willie Wessels and Eben Scheffler (Verba Vitae: Pretoria, 1992), 82-83.

64 Snyman, "Old Testament," 73.

65 Spangenberg, "Die 'vergroening,'" 8.

66 See Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "On the Origin of Death: Paul and Augustine Meet Charles Darwin," HTS 69 (2013), Art. #1992, 8 pages; doi: 10.4102/hts.v69i1.1992.

67 Caïn, d'après Victor Hugo, Légende des Siècles, 21 "la Conscience," 1859. RF280. Fernand Cormon, also known as Fernand-Anne Piestre (1845-1924), in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski. Printed with permission.

68 Edmund About, "Salon de 1880," Le XIX Siècle, May 1880, 18-19, finds the young girl being carried next to the pallet a shade lighter than the weathered and battered companions, "contraste avec les horreurs et les vulgarités exagérées du cortège."

69 Isabelle Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain: Man between Primitive and Prophet," in Picturing Evolution and Extinction: Art and Science in Republican France, ed. Fae Brauer and Serena Keshavjee (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishers, 2016), 32 describes their appearance as follows: "Cormon's figures are notably hirsute, from Cain's billowing skin, to their wild hair, so raised and matted that they distort the size and shape of their heads." The group's features have been replaced by wild gestures and features.

70 Martha Lucy, "Cormon's 'Cain' and the Problem of the Prehistoric Body," OAJ 25/2 (2002): 114-115.

71 Lucy, "Cormon's 'Cain,'" 112.

72 Lucy, "Cormon's 'Cain,'" 124.

73 Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain," 19.

74 Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain," 21.

75 Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain," 30.

76 Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain," 26.

77 Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain," 32.

78 Havet, "Fernand Cormon's Cain," 35.