Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 no.2 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n2a9

What Shall We Do with the Canaanites? An Ethical Perspective on Genesis 12:61

Knut Holter

VID Specialized University, Norway2

ABSTRACT

Colonial biblical interpretation-such as for example Moritz Merker's study of the Maasai (1904/1910), where he claims that they are historically related to the ancient Israelites-tend to see both "Israelites" and their counterparts, the "Canaanites," in the colonial, interpretive contexts. On this background, the present essay discusses a textual case, the reference to the Canaanites in Gen 12:6. It is suggested that the reference is part of a multi-voiced discourse on the role of the Canaanites, and it is concluded that the guild of biblical studies can use this discourse in relation to contemporary ethical and interpretive challenges.

Keywords: Canaanites, colonial, ethics, Gen 12, hermeneutics, interpretation

A INTRODUCTION

The introduction to the Patriarchal narrative, Gen 12:1-9, tells how Abram is called by YHWH to leave his country, his people, and his father's household and go to a land that YHWH will show him. Abram will then, in that land, be blessed and made into a great nation with a great name, and he will himself be a blessing to no less than all peoples on earth. The land of all these promises is eventually identified as the land of Canaan, and as the plot of the passage is unfolded, Abram is related to traditional and identity-carrying Canaanite "places" such as Shechem, Bethel and Ai. And then, as a climax of the passage, YHWH says that he will give this land of Canaan to Abram's descendants.

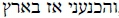

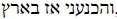

In the midst of this nice passage about blessing, descendants and land, the narrator more or less en passant mentions that the land in which the patriarchal descendants eventually are to establish a permanent settlement and become a blessing to all peoples on earth, is not entirely empty. One of all these peoples on earth is actually already established in the same land:  , "and the Canaanites were at that time in the land." This phrase from Gen 12:6 is well known to students of the OT. It belongs to the catalogue of proof texts we are exposed to when we work with a critical introduction to the historical and literary complexities of the Pentateuch. This particular proof text is often used in relation to the authorship and socio-cultural background of the Pentateuch, as the phrase "and the Canaanites were at that time in the land" reflects literary and historical perspectives that are well fit to demonstrate a central point of historical-critical interpretation of the Pentateuch, namely that the texts are not "Mosaic."

, "and the Canaanites were at that time in the land." This phrase from Gen 12:6 is well known to students of the OT. It belongs to the catalogue of proof texts we are exposed to when we work with a critical introduction to the historical and literary complexities of the Pentateuch. This particular proof text is often used in relation to the authorship and socio-cultural background of the Pentateuch, as the phrase "and the Canaanites were at that time in the land" reflects literary and historical perspectives that are well fit to demonstrate a central point of historical-critical interpretation of the Pentateuch, namely that the texts are not "Mosaic."

So far, so good. Traditional historical-critical perspectives-such as the question of the authorship and socio-cultural background of the Pentateuch-are indeed important, and clearly deserve at least some of the attention they normally receive from the guild of critical OT studies. Nevertheless, with the reference to the Canaanites and the land in Gen 12:6 as a case, I would like to reflect on the question of adding an ethical perspective to our traditional historical and literary perspectives. In November this year we celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza's epoch-making Presidential Address to the Society of Biblical Literature back in 1987.3 Her concerns for a paradigm shift in the ethos and rhetorical practices of biblical scholarship continue to receive-and deserve-attention. Scholarly communities are not only investigative communities, but also authoritative communities, she points out, as they possess the power to recognize and define what "true scholarship" entails.4 Biblical scholarship, she argues, must include an elucidation of the ethical consequences and political functions of biblical texts and their interpretations, both in their historical and contemporary sociopolitical contexts.5

As far as Gen 12:1-9 is concerned, we are facing a text that explicitly admits that the land which YHWH eventually will give to Abram's descendants already is inhabited by someone else, namely the Canaanites. And, I would argue, when we approach this text from historical and literary perspectives, but then also with some ethical sensitivity, we can hardly avoid seeing the role of YHWH vis-á-vis the Canaanites as a problem: YHWH gives the land inhabited by Canaanites to someone else. Hence, my question in relation to Gen 12, but obviously also to a number of other OT texts referring to the Canaanites: what shall we do with the Canaanites?

B WHY ASK THIS QUESTION?

Why, then, ask this question? As far as my own approach to the Canaanites in Gen 12 is concerned, I must admit that the question is not a result of a close reading of the text with a sudden feeling of pity with the Canaanites. My own way to an ethical perspective on the Canaanites-such as here in Gen 12:6-is the reception history of the OT in Africa. Having worked for many years with analysis of the first couple of generations of African OT scholars and their use (or not use) of African experiences and concerns in their interpretation of the OT,6 I am currently moving one step backwards, trying to understand what these first couple of generations reacted against. The burning question here is how the OT was interpreted in-and was clearly also a part of-western colonial discourses. One of the questions which then pops up is what to do with the Canaanites. It is a central question, I would tend to argue, as the Canaanites appear in quite a number of colonial discourses.

The most widespread approach in these colonial discourses is a "we-perspective," where the colonialists identify themselves with the ancient Israelites, faithfully occupying the Promised Land and therefore also fighting the "Canaanites" who were already there. We know such Canaanites from colonial discourses in North America, where Puritan preachers referred to Native Americans as Canaanites.7 We also know similar examples of contrasting between the chosen people and the Canaanites from colonial discourses in Australia8 and in various parts of Africa.9

However, there are also examples of a "they-perspective," where the colonialists interpret the relationship between certain indigenous groups amongst the colonized according to OT patterns. The tension between the Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda, where colonial preferences for the Tutsi minority were linked to the so-called Hamitic hypothesis, illustrates the disastrous consequences such colonial, interpretative grids may have. Another, and more illustrative example as far as the relationships between Israelites and Canaanites are concerned, is provided by a German colonial officer, Moritz Merker (1867-1908), operating in German East Africa around the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

His book Die Masai: Ethnographische Monographie eines ostafrikanischen Semitenvolkes (published in 1904, mostly referred to in its 1910 edition),10 which is an early ethnographic study of the nomadic Maasai of East Africa, includes a substantial comparison between the Maasai and ancient Israel. Merker's main idea is the existence of a number of religio-cultural parallels between the two; parallels including central aspects of anthropology and cosmology, but also a number of similar aetiologies and rituals. His interpretative approach to these parallels is then to claim that the Maasai and the ancient Israelites once back in history constituted one single people.11

Merker's basic concept, and I would say his basic colonial concept, is that whatever cultural and religious values the Maasai represent in East Africa, all these reflect their non-African background, as they originated somewhere outside the African continent, from the same people as ancient Israel. In consequence with an upgrading of the Maasai, based on racial reasons, namely their supposed non-Africanness, Merker has a very negative attitude towards the Maasai's neighbouring-and indeed African-ethnic groups. He idealizes the Maasai's nomadic way of life, against the agricultural life of the neighbours, and he emphasizes the military strength of the Maasai as having been a means to keep their race clean and free from the (in his words) degeneration that would follow intermarriage between this Semitic people and the neighbouring Negroes.12 A sharp contrast is accordingly created between the chosen people on the one hand, with its cultural expressions and military skills, and the other peoples on the other hand, lacking all these qualities. A similar paradigm is well known from previous generations of OT studies, where the religious qualities and ethical values of ancient Israelite religion were contrasted with the supposed perversities of Canaanite religion.

As demonstrated by Merker, and many other colonial interpreters of the OT, it seems that as soon as someone identifies themselves-or others-as a chosen people, the inevitable consequence is the simultaneous identification of some Canaanites. The Canaanites are, so to speak, the other side of the coin of the concept of Israel as a chosen people. And the basic problem is more or less the same in all cases. Whether self-proclaimed or proclaimed by others, for example by the colonial masters, the concept of being chosen by divine initiative easily leads to claims of being the real exponents of a sophisticated culture and true religion, and not least being the real owners of the land. And, therefore my question, for example in relation to Gen 12:6, which admits that "the Canaanites were at that time in the land": what shall we do with the Canaanites?

So, what can we do when we face a question like this? Well, as members of academia, the guild of critical OT studies, we go to the other guild members, our predecessors and contemporaries in OT studies, and of course, we go to the texts themselves. Let us pay the two, the other guild members and the text itself a visit, in that order.

C MY QUESTION AND THE OTHER GUILD MEMBERS

Let me start with a key genre of the guild, the commentary. I have gone through a few traditional-but still representative, I would say-Gen commentaries from the second half of the twentieth century. This survey seems to indicate that not many of our predecessors in the guild were lying awake during the night, worrying about the injustices the Canaanites were exposed to by YHWH. On the one hand, many commentators-and Claus Westermann is here a typical example- take the phrase about the Canaanites being in the land at the time of Abram as an indication of the historical distance between narrator and narrative, and hence also the historical reliability of the passage.13 On the other hand, some commentators simply ignore the phrase. An illustrative example is Adrianus van Selms, who devotes half a page or so to the oak of More in v. 6a, whereas he mentions not even with a single word the relationship between the Canaanites and the land in v. 6b.14 However, there are also commentators who acknowledge some of the ethical problems in the relationship between Abram and the Canaanites. Gerhard von Rad seems at first to identify fully and superficially with the sojourning Abram, as he-without any undertone of irony, I think- notices: "How unfree and unsuitable the land was for Abraham is emphasized in v. 6b." But then, eventually, Von Rad reveals his theological sensitivity, pointing out that Abraham is "[...] brought by God into a completely unexplained relationship with the Canaanites," and that "[...] YHWH does not hurry about solving and explaining this opaque status of ownership as one expects the director of history to do."15 The problem, in other words, is left in the hand of God, the director of history.

In addition to sporadic references in the genre of OT commentaries, the Canaanites have of course also been subject to several more specialized investigations, from literary and historical perspectives.16 The kind of ethical questions I raise are here quite generally ignored. However, there are also a few guild members who have reflected on the ethical questions, and I will briefly refer to three examples.

A first example is provided by is Christopher J. H. Wright. In his Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, he includes an appendix entitled "What about the Canaanites?" Wright admits that the biblical narratives of the conquest of Canaan are troubling-at least to what he calls "sensitive readers"-and he offers some perspectives intended to counter these troubling texts. One is that the OT concept of all nations-including the Canaanites-being blessed by YHWH, is an expression of an ultimate purpose, and it does not mean "[...] that God would therefore have to 'be nice' to everybody or every nation, no matter how they behaved."17 Another perspective of Wright is to see the Israelite conquest of Canaan as an act of divine punishment, as a result of what he calls their "wickedness," such as sexual perversion, fertility cults and child sacrifice. In a sum, my moral indignation at the (textual) treatment of the Canaanites finds little support here. Wright actually defends the way the Canaanites are being treated in the OT, seeing it within a framework of a just and sovereign God who leads Israel and the other nations towards an eschatological salvation.

A second example of guild members who have reflected on the ethical questions related to the OT portrayal of the Canaanites is presented by Mark G. Brett. He reads Genesis as a text reflecting concerns from the Persian period and argues that its use of ancient traditions aims at undermining the ethnocentrism of the imperial governors of that period. "There is no hint in Genesis of the ideology of dispossession that governs the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua," he argues,18 and as far as my moral indignation at the OT treatment of the Canaanites is concerned, I could accordingly have found better case texts elsewhere in the Hexateuch.

A third example is given by Gunther Wittenberg. In an article on Gen 9:26, he investigates the literary and historical background of the curse on Canaan in Gen 9. Following the lead of George Mendenhall and Norman Gottwald, he claims that the OT references to Canaanites are not to an ethnic entity, but to members of a social and political system. This is a system, he claims, that is diametrically opposed to the socio-political system of early Israel.19 The Canaanites represent a city-state system based on ruthless exploitation of outsiders on the periphery by the city, whereas the Israelites represent a class of revolutionary peasants. Being ruthless exploiters of a poor class of peasants, my moral indignation at the OT treatment of the Canaanites is obviously less justified.

Summing up, I have noticed that the traditional commentary genre-at least in its second half of twentieth century version-lacks interest for the ethical questions related to the OT portrayal of the Canaanites. However, there are some guild members who have shown attention to such questions, and the models presented by Wright, Brett, and Wittenberg, demonstrate varied interpretive potentials. On the one hand, Wright works at the surface level of the text and takes its overall plot for granted. The result is a kind of theological ethics that is obliged to defend this plot and ultimately, even to defend God. Brett and Wittenberg, on the other hand, develop two examples of a kind of resistance ethics, though from different perspectives and located in different historical contexts. Brett goes deeper into the texts than Wright and is able to construct a Genesis that uses the "Canaanites" positively to fight an ethnocentrism of the Persian period, whereas Wittenberg conceptualizes the "Canaanites" in terms of class rather than ethnicity.

D MY QUESTION AND THE TEXT

It is now time to return to the phrase in question, in Gen 12:6, and its immediate literary context, Gen 12:1-9. This is not the place to make a close analysis of the passage as a whole, and I will restrict myself to notice just one exegetical point- the rhetorical function of the keyword  , "land"-with a suggestion about its role in the overall plot.

, "land"-with a suggestion about its role in the overall plot.

There is a striking accumulation of the term  in Gen 12:1-9, with no less than seven occurrences:

in Gen 12:1-9, with no less than seven occurrences:

- Twice in v. 1, where the depicting of Abram's geographical movement refers to two opposite lands, the

of Abram's family and father's house, on the one hand, and the

of Abram's family and father's house, on the one hand, and the  that YHWH will show him, on the other.

that YHWH will show him, on the other. - Twice again in v. 5, depicting how Abram and his people-in obedience to YHWH-set out

, "to the land of Canaan," and then, repeating, that they came

, "to the land of Canaan," and then, repeating, that they came  .

. - Twice also in v. 6, first depicting how Abram, with all his people one must assume, travels through the

until a Canaanite "place," probably a cultic place, with the great oak of Moreh in Shechem, and then telling that the Canaanites at that time were in the

until a Canaanite "place," probably a cultic place, with the great oak of Moreh in Shechem, and then telling that the Canaanites at that time were in the  .

. - And finally, once in v. 7, which tells that YHWH promises to give this particular

to Abram's descendants.

to Abram's descendants.

The climax of this passage is found in v. 7, where YHWH promises

"this (particular) land" to Abram's descendants, a promise that is accepted by Abram, as he, for the first time, erects an altar for YHWH. The reference to

"this (particular) land" to Abram's descendants, a promise that is accepted by Abram, as he, for the first time, erects an altar for YHWH. The reference to  in v. 7 seems to draw the previous six references of the same term together. First, in the sense that the two opposite concepts of

in v. 7 seems to draw the previous six references of the same term together. First, in the sense that the two opposite concepts of  in v. 1 merge in v. 7: the land promised to Abram's descendants is the same land that YHWH promised to show to Abram, and it will become what Abram left in Haran, a land for him and his family. And second, in the sense that this new land of Abram's descendants is identified by the demonstrative pronoun

in v. 1 merge in v. 7: the land promised to Abram's descendants is the same land that YHWH promised to show to Abram, and it will become what Abram left in Haran, a land for him and his family. And second, in the sense that this new land of Abram's descendants is identified by the demonstrative pronoun  as the land of the Canaanites referred to four times in vv. 5-6.

as the land of the Canaanites referred to four times in vv. 5-6.

This focus on the land that will be given to Abram's descendants is then the immediate literary context of the informative phrase in v. 6:  , "and the Canaanites were at that time in the land." The question is what the rhetorical function of this phrase might be, here in vv. 1-9, and in the wider Patriarchal narrative. As noticed above, historical-critical interpretation traditionally understands the phrase as a piece of historical information about something of the past, something that is not the situation any longer. As an example, I pointed out Westermann, who takes the phrase as an indication of the historical distance between narrator and narrative.20 In other words, the rhetorical function of the reference to the Canaanites as being in the land "at that time" is to point out that so was the case at the time of Abram, but so is not the case any longer. It is as if the narrator assumes that the readers need to be informed about a peculiar demographic situation some time in a distant past, namely the presence of Canaanites in what now, at the time of the readers is not any longer the land of the Canaanites, but the land of the Israelites.

, "and the Canaanites were at that time in the land." The question is what the rhetorical function of this phrase might be, here in vv. 1-9, and in the wider Patriarchal narrative. As noticed above, historical-critical interpretation traditionally understands the phrase as a piece of historical information about something of the past, something that is not the situation any longer. As an example, I pointed out Westermann, who takes the phrase as an indication of the historical distance between narrator and narrative.20 In other words, the rhetorical function of the reference to the Canaanites as being in the land "at that time" is to point out that so was the case at the time of Abram, but so is not the case any longer. It is as if the narrator assumes that the readers need to be informed about a peculiar demographic situation some time in a distant past, namely the presence of Canaanites in what now, at the time of the readers is not any longer the land of the Canaanites, but the land of the Israelites.

I would, however, like to suggest that there is an additional dimension in the rhetorical function of this phrase, both in relation to this particular passage and in relation to the wider Patriarchal and even Pentateuchal narrative. As just pointed out, the land promised to Abram's descendants in v. 7 has previously in the passage repeatedly been identified as the land of the Canaanites; first explicitly, twice in v. 5, and then implicitly, in the reference to Shechem in v. 6a. Verse 6b's information about the Canaanites being in the land "at that time" therefore seems somewhat redundant. I would tend to think that the reader of Gen 12 already takes for granted that the Canaanites were-"at that time"-in what is referred to as the Land of Canaan, and that they were living in Canaanite "places" such as Shechem. But if so is the case, what is then the rhetorical function of the now redundant reference in v. 6b?

I will suggest that the reference to the Canaanite presence in the land as something of the past has a programmatic function here in the introduction to the Patriarchal narrative, and that it as such is part of an OT theological discourse on the Israelites and Canaanites in relation to the land. The emphasis of the Canaanite presence in the land as something of the past is, as any student of the OT will know, just one amongst several perspectives on the Canaanites within the textual universe of the Pentateuch. In spite of all commands to drive the Canaanites out of the land, a number of texts presuppose a continuing Canaanite presence. In other words, the overall message of the Pentateuch is that not only were the Canaanites "at that time" in the land, they are actually "still" in the land. This continuing Canaanite presence, however, is approached differently throughout the Pentateuch.

- Some texts state that the Canaanites shall be driven out of the land, cf. Deut 7:1-4. The motivation is here that the Canaanites-for example through intermarriage-will lead the Israelites to serve other gods.

- Some texts state that the Canaanites should be driven out of the land little by little, cf. Exod 23:28-33. The motivation of a gradual expulsion is not theological but ecological: that the land does not become desolate, with too many wild animals. Still, the motivation of the expulsion as such is again the fear that the Canaanites will lead the Israelites to serve other gods.

- Some texts accept a presence of foreigners (

) in the land, urging the Israelites to treat them respectfully, referring to Israel's own experiences of being foreigners, cf. Exod 22:20 (English translations 22:21) and Lev 19:33-34.

) in the land, urging the Israelites to treat them respectfully, referring to Israel's own experiences of being foreigners, cf. Exod 22:20 (English translations 22:21) and Lev 19:33-34.

These voices create some of the literary context of Gen 12:6 and its reference to the Canaanite presence in the land as something of the past. If we take this reference as a programmatic statement in the introduction to the Patriarchal narrative, its rhetorical function would be to express a certain political perspective on the Israelites and Canaanites in relation to the land. I concur with Brett's general reading of Genesis as a kind of resistance literature in the Persian period, but I think he misses the point when he takes Gen 12:6 as an example that "[t]he narrator refrains from commenting on any potential conflict of interest between Abram's progeny and the prior inhabitants."21 Rather, its explicit mentioning of the Canaanites in the land "at that time" strengthens the inclusive profile of Genesis. The reader of the Pentateuch, however, would soon realize that this inclusive perspective represents only one voice in the multi-voiced Pentateuch discourse on the Canaanites. There is an ambiguity in the Pentateuch, an ambiguity that parallels what David Clines many years ago referred to as the partial fulfilment and partial non-fulfilment theme of the Pentateuch.22

E CONCLUSION

So, what shall we do with the Canaanites? As I have noticed above, my own way into this field has been the reception history of the OT in Africa. References to the Canaanites have appeared in quite a number of colonial discourses related to Africa, most frequently as the other side of the coin of the concept of a-from colonial perspectives-chosen people. These colonial discourses, however, have tended to have a rather static understanding of the relationship between the Canaanites, the Israelites, and the land. Not acknowledging the multi-voiced discourse of the biblical texts, they were not able to realize the ethical potential of seeing the Canaanites as "still" being in the land. Contrary to this interpretive experience, I will argue that the multi-voiced Pentateuchal discourse on the Canaanites invites us to see inclusive texts like Gen 12:6 from a wider perspective. Likewise, the history of reception of these texts invites us to reflect on the texts in relation to today's ethical challenges and with today's interpretative strategies and concerns.23

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bechmann, Ulrike. "Genesis 12 and the Abraham-Paradigm Concerning the Promised Land." EcRev 68 (2016): 62-80. [ Links ]

Boer, Roland. Last Stop Before Antarctica: The Bible and Postcolonialism in Australia. BPost 6. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Botterweck, G. Johannes and Helmer Ringgren. Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Alten Testament. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1970-. [ Links ]

Brett, Mark G. Genesis: Procreation and the Politics of Identity. OTR. London: Routledge, 2000. [ Links ]

______. "Reading the Bible in the Context of Methodological Pluralism: The Undermining of Ethnic Pluralism in Genesis." Pages 48-74 in Rethinking Contexts, Rereading Texts: Contributions from the Social Sciences to Biblical Interpretation. Edited by M. Daniel Carroll R. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. A. The Theme of the Pentateuch. JSOTSup 10. Sheffield: Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 1978. [ Links ]

Holter, Knut. Old Testament Research for Africa: A Critical Analysis and Annotated Bibliography of African Old Testament Dissertations, 1967-2000. BTA 3. New York: Peter Lang, 2002. [ Links ]

______. Contextualized Old Testament Scholarship in Africa. Nairobi: Acton Publisher, 2008. [ Links ]

Lemche, Niels Peter. The Canaanites and their Land: The Tradition of the Canaanites. JSOTSup 110. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Merker, Moritz. Die Masai: Etnographische Monographie eines ostafrikanischen Semitenvolkes. 2nd enl. ed. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1910 [1st ed. 1904]. [ Links ]

Prior, Michael. The Bible and Colonialism: A Moral Critique. BibSem 48. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. "The Ethics of Biblical Interpretation: Decentering Biblical Scholarship." JBL 107 (1988): 3-17. Reprinted pages 17-30 in Rhetoric and Ethic: The Politics of Biblical Studies. Edited by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999. [ Links ]

Van Selms, Adrianus. Genesis. Vol. 1. POut. Nijkerk: G.F. Callenbach, 1973. [ Links ]

Von Rad, Gerhard. Genesis. OTL. London: SCM Press, 1978. [ Links ]

Warrior, Robert Allen. "A Native American Perspective: Canaanites, Cowboys, and Indians." Pages 235-241 in Voices from the Margin: Interpreting the Bible in the Third World. Edited by Rasiah S. Sugirtharajah. Rev. and enl. 3rd ed. Maryknoll: Orbis, 2006. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Genesis 12-36. BKAT I,2. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1981. [ Links ]

Wittenberg, Gunther. ''' ... Let Canaan be his Slave' (Gen 9:26): Is Ham also Cursed?" JTSA 74 (1991): 45-56. Reprinted pages 25-42 in Resistance Theology in the Old Testament: Collected Essays. Edited by Gunther Wittenberg. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2007. [ Links ]

Wright, Christopher J. H. Old Testament Ethics for the People of God. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2004. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 01/02/2017

Peer-reviewed: 27/02/2017

Accepted: 16/05/2017

Professor Knut Holter, Centre for Mission and Global Studies & Faculty of Theology, Diaconia and Leadership Studies, VID Specialized University, Misjonsmarka 12, N-4024 Stavanger, Norway. Email: Knut.Holter@vid.no.

1 It is a privilege to dedicate this essay to Professor Sakkie Spangenberg, a friend and colleague, whose focus on the ethical dimensions of doing biblical and theological studies I have always appreciated.

2 The research for this essay is part of the project "Potentials and problems of popular inculturation hermeneutics in Maasai biblical interpretation," funded by the Norwegian Research Council, whose contribution is hereby acknowledged.

3 Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, "The Ethics of Biblical Interpretation: Decentering Biblical Scholarship," JBL 107 (1988): 3-17; reprinted in Rhetoric and Ethic: The Politics of Biblical Studies, ed. Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999), 17-30.

4 Schüssler Fiorenza, "Ethics," 8.

5 Schüssler Fiorenza, "Ethics," 15.

6 Cf. Knut Holter, Old Testament Research for Africa: A Critical Analysis and Annotated Bibliography of African Old Testament Dissertations, 1967-2000, BTA 3 (New York: Peter Lang, 2002); Knut Holter, Contextualized Old Testament Scholarship in Africa (Nairobi: Acton Publisher, 2008).

7 Robert Allen Warrior, "A Native American Perspective: Canaanites, Cowboys, and Indians," in Voices from the Margin: Interpreting the Bible in the Third World, ed. Rasiah S. Sugirtharajah, rev. and enl. 3rd ed. (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2006), 235-241.

8 Roland Boer, Last Stop Before Antarctica: The Bible and Postcolonialism in Australia, BPost 6 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 88-119.

9 Michael Prior, The Bible and Colonialism: A Moral Critique, BibSem 48 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997), 71-105.

10 Moritz Merker, Die Masai: Etnographische Monographie eines ostafrikanischen Semitenvolkes, 2nd enl. ed. (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1910).

11 Merker, Die Masai, 338-344.

12 Merker, Die Masai, 347-351.

13 Claus Westermann, Genesis 12-36, BKAT I,2 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1981), 65, 179.

14 Adrianus van Selms, Genesis, vol. 1, POut (Nijkerk: G.F. Callenbach, 1973), 180.

15 Gerhard von Rad, Genesis, OTL (London: SCM Press, 1978), 162, 166.

16 Typical examples are Hans-Jürgen Zobel, " ," ThWAT 4 (1984): 224-243, and Niels Peter Lemche, The Canaanites and their Land: The Tradition of the Canaanites, JSOTSup 110 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991).

," ThWAT 4 (1984): 224-243, and Niels Peter Lemche, The Canaanites and their Land: The Tradition of the Canaanites, JSOTSup 110 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991).

17 Christopher J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 473.

18 Mark G. Brett, Genesis: Procreation and the Politics of Identity, OTR (London: Routledge, 2000), 51; cf. also Mark G. Brett, "Reading the Bible in the Context of Methodological Pluralism: The Undermining of Ethnic Pluralism in Genesis," in Rethinking Contexts, Rereading Texts: Contributions from the Social Sciences to Biblical Interpretation, ed. M. Daniel Carroll R. (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), 48-74.

19 Gunther Wittenberg, Let Canaan be his Slave' (Gen 9:26): Is Ham also Cursed?" JTSA 74 (1991): 45-56; reprinted in Resistance Theology in the Old Testament: Collected Essays, ed. Gunther Wittenberg (Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2007), 25-42.

20 Westermann, Genesis 12-36, 65, 179.

21 Brett, Genesis, 51.

22 David J. A. Clines, The Theme of the Pentateuch, JSOTSup 10 (Sheffield: Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 1978).

23 A recent, illustrative contribution is Ulrike Bechmann, "Genesis 12 and the Abraham-Paradigm Concerning the Promised Land," EcRev 68 (2016): 62-80. Bechmann uses Gen 12 in relation to the Israel/Palestine discourse, but the text and interpretive perspective obviously has a much wider potential.