Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 n.2 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n2a4

Psalm 39 and its Place in the Development of a Doctrine of Retribution in the Hebrew Bible1

Phil J. Botha

University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Psalm 39 is a peculiar, late post-exilic wisdom composition which reflects the style of a supplication of a sick person, but actually rather constitutes a meditation on the transitoriness of human life. It has been neatly integrated into the conclusion of Book I of the Psalter by a late post-exilic redaction, but displays antithetic views with regard to expectations about retribution expressed in other psalms ostensibly from the same post-exilic era. This article explores its possible purpose in view of its form, its integration into Book I of the Psalter, and particularly its seeming contrastive stance towards Pss 34 and 37. Its apparent criticism of the perspective on retribution expressed in other wisdom psalms renders it very similar to Ps 73 as well as to notions expressed in the Book of Job, and the psalm is therefore compared to these texts as well.

Keywords: Wisdom; illness; redaction criticism; retribution; post-exilic psalms.

A INTRODUCTION

Psalm 39 can be described as a perplexing psalm at the conclusion of the first Davidic collection (3-41). It is peculiar since its form, which resembles that of a supplication of someone suffering from disease, clashes with its contents, which can be better described as a wisdom reflection. It is not an easy psalm to interpret and researchers have attempted to explain its meaning from various perspectives such as its form, its contents, the wisdom influence it displays, its probable time of origin, and its intertextual connections to other parts of the Hebrew Bible (HB). All these aspects have provided valuable insights, but the last word about what the author and/or the editors intended to convey with this composition has perhaps not been spoken yet. It is the contention of this article that it probably was not composed by a sick person or to be used as a cultic formulary for someone suffering from disease,2 but rather to serve as a wisdom reflection on how to overcome theological frustration caused by delayed retribution.

According to some investigators, it is one of the most pessimistic psalms.3 Others see a shimmer of hope shining through,4 especially when it is read as part of a cluster of psalms (38-41) in Book I of the Psalter.5 This article will try to take cognisance of the results of various approaches towards its interpretation, but will focus on the way in which the author seems to create dissonance with views on retribution expressed specifically in Pss 34 and 37. The purpose of the author in this regard appears to be a toning down of some of the expectations created by those psalms and the propagation of an attitude which reaches out to Yahweh in faith, trying to overcome disappointment over the lack of equivalence between actions and consequences as promised in Pss 34 and 37. In this respect Ps 39 is quite similar to Ps 73 as well as the Book of Job, and the authors of both these texts also seem to allude to it in search of support.6

B A TRANSLATION7 AND SYNCHRONIC READING OF PSALM 39

1 To the choirmaster; to Jeduthun. A Psalm of David.

I A 2 I said, "I want to guard my ways from sinning with my tongue;

I want to guard my mouth with a muzzle,

while the wicked are in my presence."

B 3 I was mute and silent; I remained silent (far) from good,8

but my pain was stirred.

4 My heart became hot within me.

As I mused, a fire burned;

then I spoke with my tongue:

II C 5 "Yahweh, make me know my end

and the measure of my days, what it is;

let me know how fleeting I am!

6 Behold, you have made my days a few handbreadths,

and my lifetime is as nothing before you.

Surely all mankind stands as a mere breath! Selah.

D 7 Surely a man goes about as a shadow!

Surely for nothing are they restless;

he heaps up and does not know who will gather!

III E 8 "And now, Adonai, for what do I wait?

My hope, it is in you!

9 Deliver me from all my transgressions.

Do not make me the scorn of a fool!

F 10 I am mute; I do not open my mouth,

for it is you who have done it.

11 Remove your stroke from me;

I am spent by the hostility of your hand.

G 12 When, with punishments for sin, you discipline a man,

you consume like a moth what was desired9 by him;

surely all mankind is a mere breath! Selah.

IV H 13 "Hear my prayer, Yahweh, and give ear to my cry;

do not be silent at my tears!

For I am a stranger with you,

a sojourner, like all my fathers.

14 Remove your gaze from me, that I may smile again

before I depart and am no more!"

The poet has possibly provided a clue to the intended segmentation of the psalm through the prominent use of three forms of address of Yahweh, which in this psalm seem to serve as transition markers: In 39:5 and 13 he uses the divine name Yahweh and in v. 8 he addresses Yahweh as "Adonai." Each of these introduces a new stanza (II, III, and IV).10 Verse 8 also begins with the phrase "And now," which is a known transition marker in other prayers in the HB.11 The second to fourth stanzas can consequently all be described as different "prayers" or different segments of a "prayer" addressed to Yahweh, although the word "prayer" itself is only used at the beginning of stanza IV, v. 13.

The second to fourth stanzas consist of a dialogue with Yahweh with a sprinkling of imperatives directed at him throughout, but with increasing incidence towards the end.12 A form of the first person singular pronoun also occurs in each of the three segments of the "prayer," although not necessarily at the beginning of the stanzas (39:5, 11, and 13). The boundaries of stanza I is further demarcated through inclusio of the word "tongue," (39:2a, 4c) and that of the second stanza through inclusio of the verb "to know" (39:5a, 7c). There is a chiastic parallel between the end of stanza II and that of stanza III: In stanza II, the aphorism on humanity's transitoriness, "surely all mankind (

) stands as a mere breath" is followed by another on the futility of humanity's (

) stands as a mere breath" is followed by another on the futility of humanity's ( , 39:7) activity, while in stanza III a statement on Yahweh's chastisement of humanity (

, 39:7) activity, while in stanza III a statement on Yahweh's chastisement of humanity ( , 39:12) is followed by a repetition of the aphorism about mankind's (

, 39:12) is followed by a repetition of the aphorism about mankind's ( ) being a mere breath, although it is repeated in a slightly different form.

) being a mere breath, although it is repeated in a slightly different form.

The first stanza, which thus serves as an introduction to the "prayer" proper, is used by the poet to describe his self-deliberation and the resolve to keep quiet because of the presence of "wicked" people, as well as the pain this caused him so that he had to address Yahweh about his distress. The second, third, and fourth stanzas could consequently all be understood as the words which the psalmist "spoke" with his "tongue" (thus not only in thought) as a prayer to Yahweh (39:4c), in contrast to his "saying" to himself (thus thinking, 39:2a). The adverb of time, "And now ..." with which stanza III (39:8a) is introduced, could, however, be understood rather as an indication that the narrative about the past supplication (stanza II) has ended and that a "prayer" in real time (comprising stanzas III and IV) is now beginning. This ambiguity is possibly intentional.

A synchronic reading of Ps 39, based on the structure proposed above, can be summarised as follows:

I A In a self-deliberation, the psalmist explains the reason for composing the psalm.13 He earlier wanted to keep silent so that he would not sin with his tongue.

B Initially he did keep silent, but his thoughts could not be suppressed; thus he began to address Yahweh in prayer.

II C He explains how he said to Yahweh that he had to know exactly how fleeting his life is. He told Yahweh that, in comparison to Yahweh, all humanity is a mere breath.

D Because of human frailty, all activity potentially becomes meaningless. Human existence is only shadowy and there is no control over who will inherit what people have gathered during their lives.

III E The psalmist now prays and tells Yahweh that, in view of the uncertainty of life, his only hope for meaning is located in Yahweh. To give meaning to his life, he asks Yahweh to forgive his transgressions and to save him from the ridicule of fools.

F He acknowledges in his prayer that his fate is in the hands of Yahweh and promises to remain silent henceforth, but asks Yahweh to stop disciplining him.

G In a universalising conclusion of the stanza, the psalmist ascribes the transitoriness of possessions and human life to the abrasive effect of Yahweh's discipline for sin. Yahweh's discipline is portrayed as the reason why all mankind is a mere breath.

IV H The psalmist once more pleads with Yahweh to take note of his plight. Human feebleness implies that he only has the status of a guest in the presence of Yahweh. Consequently, he would like to have some respite before he dies.

The poem is extraordinarily rich with images: To force himself to keep silent, the psalmist wanted to put on a muzzle (39:2). Discomfort with keeping his thoughts to himself was like pain or fire on the inside (39:4).14 The temporal duration of his life is comparable to the shortest measure of distance, the width of a few sets of four fingers (39:6). Human life is compared to breath which disappears almost immediately when it is exhaled (39:6, 12). Human existence is shadowy at best (39:7). Gathering possessions is like throwing things on a heap (39:7).15 Suffering is like receiving a blow from the hostile hand of Yahweh (39:11).16 Yahweh's punishment eats away what is dear to mankind like (the larva of) a moth consumes (woollen) clothes (39:12).17 The psalmist is like a temporary resident in a foreign country, without real estate or residential rights (39:13).18 Yahweh's discipline is like the stern look of a father or other figure of authority (39:14).

The psalmist's agony is caused by his awareness of the effects of sin which he understands to be the root cause of human frailty, but possibly also the realisation that retribution implies that Yahweh pays closer attention to the actions of the upright, causing dissonance between his faith in Yahweh and his experience of adversity.

C PSALM 39 INTERPRETED IN THE CONTEXT OF ITS CLUSTER

Gianni Barbiero has done extremely helpful work in interpreting Ps 39 as part of the cluster Pss 38-41,19 while pointing out also that this series constitutes a bigger unit in combination with Pss 35-37.20 The following is a short summary of Barbiero's insights, put into my own words:

- There are significant similarities between Pss 38 and 39, but also a dialectic which should be interpreted against the background of the whole series 35-41. The psalmist of Ps 35 became indignant because the enemies rewarded him with evil for good (35:12). In response to his indignation, the implied author of 37:7 advised him to remain "silent (

) before Yahweh." This advice is heeded by the psalmist of 38:14-15, who reacts to the verbal attacks of his opponents as if he is deaf and mute (cf. the allusion in 38:21 back to 35:12). The psalmist in 39:3 also wants to follow this advice about keeping silent (

) before Yahweh." This advice is heeded by the psalmist of 38:14-15, who reacts to the verbal attacks of his opponents as if he is deaf and mute (cf. the allusion in 38:21 back to 35:12). The psalmist in 39:3 also wants to follow this advice about keeping silent ( ), but fails in his attempt. He consequently "speaks" out with his "tongue."21

), but fails in his attempt. He consequently "speaks" out with his "tongue."21 - The reason why the implied author of Ps 39 responds to the advice of Ps 37 in a different way than the author of Ps 38 is because the illness of the psalmist of Ps 38 has led to a new level of thinking (

, 39:4) about the problem of theodicy. According to Ps 39, there is no real distinction between the fate of the righteous or that of the wicked (cf. 39:6, 12). There is therefore no reason to become indignant about the prosperity of the wicked. The suffering of pious people is also in the final analysis not caused by the enemies, but by Yahweh (39:10). Illness is recognised by the psalmist of Ps 39 as God's discipline for sin (39:12). But even when his sins are forgiven and his enemies have disappeared, the problem of death remains. The psalmist consequently feels that he is given over into the power of God, which conversely implies that his whole life is dependent on God only. This causes the ambivalent reaction of accusing God for his distress, but holding on to him nevertheless. The psalmist of Ps 39 thus eventually attains the same attitude of silence which is aspired to in Pss 37 and 38, but only after having recognised the face of God behind his problem, like Job also did (39:10; cf. Job 42:2-5).22

, 39:4) about the problem of theodicy. According to Ps 39, there is no real distinction between the fate of the righteous or that of the wicked (cf. 39:6, 12). There is therefore no reason to become indignant about the prosperity of the wicked. The suffering of pious people is also in the final analysis not caused by the enemies, but by Yahweh (39:10). Illness is recognised by the psalmist of Ps 39 as God's discipline for sin (39:12). But even when his sins are forgiven and his enemies have disappeared, the problem of death remains. The psalmist consequently feels that he is given over into the power of God, which conversely implies that his whole life is dependent on God only. This causes the ambivalent reaction of accusing God for his distress, but holding on to him nevertheless. The psalmist of Ps 39 thus eventually attains the same attitude of silence which is aspired to in Pss 37 and 38, but only after having recognised the face of God behind his problem, like Job also did (39:10; cf. Job 42:2-5).22 - According to Barbiero, one should not stop reading at the end of Ps 39. Psalms 38 and 39 should be read together as a lament which is followed by thanksgiving in 40:2-11. The cluster ends with wisdom instruction in 41:2-4.23 As Barbiero remarks, someone who reads Ps 39 on its own could wonder whether the author of the psalm was a believing or a despairing person. But the final form of the text (with 39 and 40 in juxtaposition) defines Ps 39 unequivocally as an expression of faith.24Without having asked to be saved from death, deliverance from death was given to the psalmist of Ps 39 and that is why he wants to sing a "new song" in 40:4. The author of Ps 39 resolves to keep his mouth closed (39:10), but Yahweh opens it again by giving him a new song (40:4).25

- From Barbiero's analysis, it becomes clear that the theme of silence is an important one in the cluster running from 35-41. This, together with the theme of suffering, in turn also establishes links to Isaiah's servant songs. The rare lexeme

(38:12 and 39:11; cf. Is 53:4, 8), as well as the lexeme

(38:12 and 39:11; cf. Is 53:4, 8), as well as the lexeme  (38:18; 39:3; cf. Is 65:14) occur also together in the description of the servant of Yahweh. The patient bearing of his lot without opening his mouth and his silence before his enemies are themes which connect these two psalms with Is 53:7 in Barbiero's view (cf.

(38:18; 39:3; cf. Is 65:14) occur also together in the description of the servant of Yahweh. The patient bearing of his lot without opening his mouth and his silence before his enemies are themes which connect these two psalms with Is 53:7 in Barbiero's view (cf.  and

and  in 38:14; 39:3; and Is 53:7).26 This connection is strengthened by the links between the theme of the "new song" in Ps 40:4 and Is 42:10 which, in both instances, follows upon a long period of silence (cf. Is 42:14 and Ps 40:10). This causes the figure of the servant of Yahweh in his profile of nonviolence and atoning suffering to shimmer through behind Pss 35-40.27

in 38:14; 39:3; and Is 53:7).26 This connection is strengthened by the links between the theme of the "new song" in Ps 40:4 and Is 42:10 which, in both instances, follows upon a long period of silence (cf. Is 42:14 and Ps 40:10). This causes the figure of the servant of Yahweh in his profile of nonviolence and atoning suffering to shimmer through behind Pss 35-40.27

What can be inferred from Barbiero's analysis is that the keyword connections between Ps 39 and other members of the cluster are important cues for understanding the meaning the redactors of the first Davidic Psalter assigned to Ps 39. The majority of concatenating connections were probably inserted by the redactors, a process through which they assigned contextual meaning to individual psalms. Psalm 39 nevertheless also displays engagement with, possibly allusions to, Pss 34 and 37 which could not all have been inserted afterwards as concatenating links. Such a theological response to or dialectic with the doctrine of retribution in Pss 34 and 37 also contributes to the meaning of Ps 39 and should be considered in its interpretation.

In studying key-word connections to other psalms in a cluster, the exegete is working in a synchronic way. When similarities between texts are described as "allusions," however, one crosses over to the domain of intertextuality which involves both synchrony and diachrony.28 Will Kynes has demonstrated how external cohesion (i.e., the way in which an allusion relates to the context from which it possibly or probably came) can serve as a synchronic approach which helps to solve a diachronic question.29 If an author alludes to a certain text, the context from which the allusion is taken should support the purpose of the author in the quoting text, for instance by providing authoritative support or by creating parody with the text from which the author quotes.30 In the next section, Ps 39 is described as a text which possibly purposefully creates dissonance with Pss 34 and 37.

D PSALM 39 AS AN INTERTEXT

When was Ps 39 composed? According to Hossfeld and Zenger,31 Ps 39 was added to an already existing collection of (late) pre-exilic, exilic and early post-exilic psalms during the fifth to fourth centuries BCE. According to them, the earliest collection of psalms probably consisted of (late) pre-exilic supplicatory, lamenting and thanksgiving psalms and possibly included Pss 3-7; 11-14; 17; 18; 20; 21; 22; 26-28; 30-31; 35; 38; and 41, although some of these probably originally had a more rudimentary form.

Towards the end of the exile or in the early post-exilic era, another set of editors added more psalms to this collection, including some which they themselves may have composed. According to Hossfeld and Zenger, among these were Pss 8; 15; 24; 29; 32; and 36. These editors also arranged the psalms in clusters consisting of 3-14 (as yet without 9-10); 15-24 (as yet without 16, 19 and 23); 26-32 and 35-41 (as yet without 37, 39, and 40). This new collection represented the pious as a group of poor and persecuted people who wanted to live as righteous people. Somewhat later, during the fifth to fourth century BCE (thus sometime between 500 and 301 BCE), another redaction expanded this existing collection by "updating" some of the existing psalms and by adding Pss 16; 19; 23; 25; 33; 34; 37; 39 and 40.32 Finally, in the Hellenistic period, Pss 9-10 were added, while Pss 42-88 (which were collected separately) were afterwards combined with 3-41.

In my view, there is evidence of coherence between most of these psalms which Hossfeld and Zenger say were added during the fifth to fourth centuries. In some of them, for example, the role which the teacher of wisdom plays in Proverbs can be seen to have been replaced by Yahweh as the teacher of his Torah,33 while other wisdom themes found also in Proverbs have been appropriated similarly in most of them. It is also clear that such traces of wisdom are not later additions to these psalms, but that these psalms were composed by sages who were schooled in wisdom and also had a profound knowledge of various other parts of the HB which, by this time, must have begun to be recognised as authoritative. This is why they display a growing number of "echoes" of or allusions to other texts, prompting some researchers to speak of an "anthological" style of composition such as is perhaps most clearly seen in Pss 1 and 119, but also in the members of this group.34

Following the cue provided by Hossfeld and Zenger, the rest of this section will be dedicated to a comparison of Ps 39 with Pss 34 and 37, since the topics of reward and retribution feature very strongly in these two acrostics which were added (in the view of Hossfeld and Zenger) more or less simultaneously with Ps 39 to the Psalter. Similarities and differences in the treatment of retribution will form the focus of the comparison. Barbiero's views on important thematic connections between Pss 37 and 39 have already been noted.

Many investigators have also noted the literary connections between Ps 39 and Job and also its similarities with Ecclesiastes.35 A small number of them ventured to express a view on whether Ps 39 served as inspiration for Job or whether it was the other way round,36 but through the excellent work of Will Kynes,37 this matter has now been settled with reasonable certainty: He has argued convincingly that the author of Job alludes to Ps 39,38 as Job does with many other psalms and texts from the HB.39 Since it is the author of Job who alludes to Ps 39, such allusions can tell us something about the way in which he understood Ps 39 and about the relative dating of Ps 39. It is also enlightening to note the similarities in the way in which the authors of both Ps 39 and Job enter into discussion with other texts and use allusions to these texts as a rhetorical device to strengthen their own arguments.

1 The Relationship of Psalm 39 with Psalms 34 and 37

As one can expect, Ps 39 has a number of themes and keywords in common with the other psalms mentioned by Hossfeld and Zenger as being more or less contemporaneous with it. The two acrostic wisdom psalms 34 and 37 are especially noteworthy in this regard. All three these psalms essentially engage with the theological problem of retribution. Psalm 34 was composed in the guise of a song of thanksgiving. It stresses through repetition that Yahweh is willing and able to respond to the cry for help of the righteous with help and salvation from distress40 and forgiveness for sins,41 that he will bless the righteous with sufficient material possessions for a happy life,42 but that the wicked will perish as a result of their own iniquity.43 What is necessary for the righteous is an attitude of humility and to refrain from speaking or doing evil, of criticising Yahweh or attempting to put matters right on their own.44 Beneath the surface it is possible to detect frustration among the upright with post-exilic conditions of social injustice and deprivation and an impatience with delayed retribution.45 The same frustration is even more clearly visible in Ps 37, although the matter of possession of the land by the righteous is focused upon and stressed through repetition in that psalm.46 Similar advice is given to the upright in the two psalms (cf. Ps 34:15 with Ps 37:3 and 27), namely to avoid wrong actions and rather pursue peace or act in faithfulness. Psalm 37 also warns more explicitly against becoming upset by or envious of wrongdoers47and against transgressing with one's mouth.48 The author similarly acknowledges that the righteous do (sometimes) experience deprivation,49 but insists that Yahweh will eventually save the humble from the attacks of the wicked (37:12-13; 40), that the wicked will die without the prospect of a future,50 but that the upright will have great peace and prosperity and will (eventually) take possession of the land which was promised to them as the true Israel.51

If it is compared to these two psalms, it is clear that Ps 39 is also concerned with retribution and the correct response to frustrations with its postponement, but that the author has a different perspective on the expectations entertained in Pss 34 and 37:52

- The author wanted to comply with the injunctions in Ps 34:14 to keep (

) his tongue (

) his tongue ( ) from evil and his lips from speaking deceit; and also those in Ps 37:7 to stay quiet (

) from evil and his lips from speaking deceit; and also those in Ps 37:7 to stay quiet ( ) before Yahweh and wait patiently (

) before Yahweh and wait patiently ( ) for him to act. He says that he had resolved to guard (

) for him to act. He says that he had resolved to guard ( ) his ways so as not to sin with his tongue (

) his ways so as not to sin with his tongue ( ) (39:2) and did remain silent (

) (39:2) and did remain silent ( ) (39:3), but this was a silence far from good (

) (39:3), but this was a silence far from good ( ), while Ps 34:13 promises that those who comply, will see good (

), while Ps 34:13 promises that those who comply, will see good ( ).53

).53 - In spite of the implied advice in Ps 34:19 to accept the stance of the broken-hearted (

), his heart (

), his heart ( ) became hot (

) became hot ( ) within him (39:4). This contravenes the repeated advice of Ps 37:7-8 to not get excited (

) within him (39:4). This contravenes the repeated advice of Ps 37:7-8 to not get excited ( ), to refrain from anger (

), to refrain from anger ( ) and to forsake wrath (

) and to forsake wrath ( ). He consequently did speak out, possibly in the presence of the wicked who were the cause of his agitation (cf. 39:2).54

). He consequently did speak out, possibly in the presence of the wicked who were the cause of his agitation (cf. 39:2).54 - The contents of his complaint were about the brevity of his life. He asks Yahweh to inform him (

) about his end and the measure of his days; he wants to know how transient he is (39:5). These questions are rhetorical in nature, since he already knows that his lifetime is as nothing before Yahweh, that every human is a mere breath (39:6). These emphatic statements form antithesis to the pronouncement in Ps 34:13 that a righteous person can love life and will have many days to see good. It also contradicts Ps 37:4 which implies that for the righteous it is possible to delight themselves in Yahweh and then simply receive the desires of their heart.55 Psalm 37:18 also says that Yahweh knows the days of the blameless and that their heritage will remain forever. According to the author of Ps 39, human life is but like a shadow and there is no certainty about who will gather the wealth that one generation heaps up (39:7). This contradicts Ps 37:11 which says that the oppressed will inherit the land and take delight in abundant peace. No one will "dwell forever" as Ps 37:27 promises, it seems.

) about his end and the measure of his days; he wants to know how transient he is (39:5). These questions are rhetorical in nature, since he already knows that his lifetime is as nothing before Yahweh, that every human is a mere breath (39:6). These emphatic statements form antithesis to the pronouncement in Ps 34:13 that a righteous person can love life and will have many days to see good. It also contradicts Ps 37:4 which implies that for the righteous it is possible to delight themselves in Yahweh and then simply receive the desires of their heart.55 Psalm 37:18 also says that Yahweh knows the days of the blameless and that their heritage will remain forever. According to the author of Ps 39, human life is but like a shadow and there is no certainty about who will gather the wealth that one generation heaps up (39:7). This contradicts Ps 37:11 which says that the oppressed will inherit the land and take delight in abundant peace. No one will "dwell forever" as Ps 37:27 promises, it seems. - The author of Ps 39 asks to be delivered (

) from his transgressions (39:9). He seems oblivious of the fact that no one who takes refuge in Yahweh will be condemned (34:23), that the righteousness of the righteous will shine forth like light and their justice as noonday (37:6), or that the righteous person will not be condemned when he is brought to trial (37:33). He realises that it is as a result of his transgressions that his life is fading away (39:9, 11-12). He is afraid of being made the scorn (

) from his transgressions (39:9). He seems oblivious of the fact that no one who takes refuge in Yahweh will be condemned (34:23), that the righteousness of the righteous will shine forth like light and their justice as noonday (37:6), or that the righteous person will not be condemned when he is brought to trial (37:33). He realises that it is as a result of his transgressions that his life is fading away (39:9, 11-12). He is afraid of being made the scorn ( ) of a fool (39:9), even though the righteous are promised in Ps 34:6 that they will be radiant, never having to blush for shame (

) of a fool (39:9), even though the righteous are promised in Ps 34:6 that they will be radiant, never having to blush for shame (

).

). - Instead of the wicked fading away (

) like green shoots of grass (37:2) or perishing (

) like green shoots of grass (37:2) or perishing ( ) suddenly like the glory of the pastures or vanishing (

) suddenly like the glory of the pastures or vanishing ( ) like smoke (37:20), the suppliant of Ps 39:11 is perishing (

) like smoke (37:20), the suppliant of Ps 39:11 is perishing ( ) through the hostility of the hand of Yahweh. It is not the wicked who will disappear so that he suddenly will not be there any more (

) through the hostility of the hand of Yahweh. It is not the wicked who will disappear so that he suddenly will not be there any more ( ) (37:10, 36); it is the suppliant himself who will soon disappear and not be there any more (

) (37:10, 36); it is the suppliant himself who will soon disappear and not be there any more ( ) (39:14).56

) (39:14).56 - Instead of being a permanent resident, an inhabitant (

in 37:3, 27, 29) of the land of God, the suppliant of Ps 39 experiences life like a stranger and a sojourner (

in 37:3, 27, 29) of the land of God, the suppliant of Ps 39 experiences life like a stranger and a sojourner ( ...

...  ...

...  ) with Yahweh (39:13). The promises of reward in Ps 37 have failed to materialise.

) with Yahweh (39:13). The promises of reward in Ps 37 have failed to materialise. - Instead of the enjoyment of the good life (34:13) and taking delight in Yahweh (37:4) and in great peace (37:11) with the prospect of a future (37:37), because the eyes of Yahweh are on the righteous and his ears toward their cry for help (

) (34:16), the cry for help (

) (34:16), the cry for help ( , 39:13) of the suppliant of Ps 39:14 is that Yahweh should remove his eye for a short while from the suppliant so that he can enjoy a little cheer (

, 39:13) of the suppliant of Ps 39:14 is that Yahweh should remove his eye for a short while from the suppliant so that he can enjoy a little cheer ( hi) before he dies. The eyes of Yahweh have become a threat instead of a comfort.

hi) before he dies. The eyes of Yahweh have become a threat instead of a comfort. - The only similarity between the suppliant of Ps 39 and the advice offered in Ps 37 is that he still waits (

pi) for Yahweh, that his hope (

pi) for Yahweh, that his hope ( ) remains in Yahweh (39:8). This hope of the suppliant of Ps 39:8 has a possible antecedent in Ps 37:7.57 The author of Ps 37:34 instructs his audience to wait (

) remains in Yahweh (39:8). This hope of the suppliant of Ps 39:8 has a possible antecedent in Ps 37:7.57 The author of Ps 37:34 instructs his audience to wait ( pi) for Yahweh, and to trust in him (37:5), since he will act (

pi) for Yahweh, and to trust in him (37:5), since he will act ( ). The suppliant of Ps 39's eventual resolve to remain silent is because Yahweh has acted (

). The suppliant of Ps 39's eventual resolve to remain silent is because Yahweh has acted ( ), although we can be sure that he did not act in the same way as was expected by the author of Ps 37:5.

), although we can be sure that he did not act in the same way as was expected by the author of Ps 37:5.

More examples can be added.58 The author of Ps 39 thus uses words which occur in the other two more or less contemporaneous (in the view of Hossfeld and Zenger) psalms to formulate statements which question or contradict the established beliefs of wisdom piety and the promises made there. This style can be considered to be a critical reaction to the aphorisms about retribution found in Pss 34 and 37. It is possible that it's critical view of material retribution for the wicked and reward for the righteous co-existed with the positive expectations of Pss 34 and 37, but the similarity between the criticism expressed in Ps 39 and the book of Job as well as the way in which the authors of both texts formulated a dissenting perspective from such views, do seem to suggest that Ps 39 probably originated at least some time later than Pss 34 and 37 and that it was possibly intended to serve as a muted response to the more optimistic expectations of those two.

2 The Connections between Psalm 39 and Psalm 73

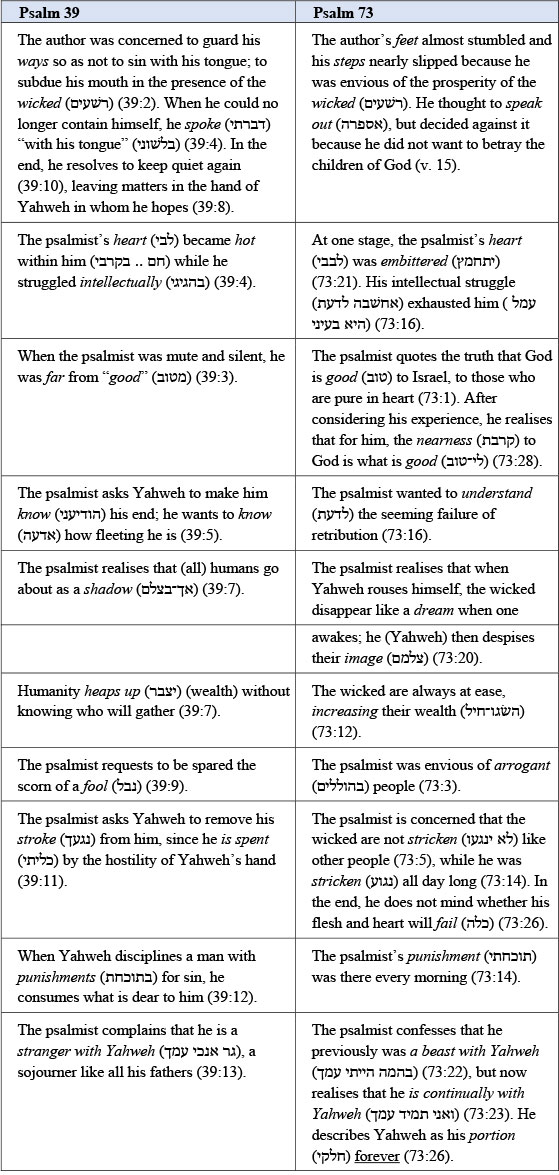

It has been noted by many researchers that there is a close connection between Pss 39 and 73.59 Most investigators would accept that there are lexical and thematic similarities, but few would concede that there exists a literary relationship between the two. It does seem possible, however, that the author of Ps 73 was responding on his part to Ps 39. The similarities can be tabulated as follows:

Despite the differences in tone and conclusion, the two psalms seem to be close in theological milieu and thinking. They share many themes, such as indignation with the arrogance of the wicked. The author of Ps 73 complains that the wicked seem to prosper and to escape the discipline of Yahweh, while the suppliant himself suffers blows from the hand of Yahweh. In Ps 39, the chastisement of the suppliant is not singled out as more stringent than that of the rest of humanity, but the psalmist seems to emphasise that he is certainly not treated better than any other human being.

In both psalms, the suppliant is concerned that it is arrogant and disloyal to criticize Yahweh's justice, since sinning with the mouth constitutes a stumbling on the way of life. Only the wicked, arrogant, apostate Israelites do this openly. However, because this theological problem is such a burning matter, robbing the suppliant of happiness, and since both psalmists would like to understand how it works, they do voice their concern.

Both psalmists find insight afterwards: In the case of Ps 39, the suppliant realises that all humanity is but like a phantom which quickly disappears and that there is no control over who will inherit a rich man's fortune. He resolves to stop his criticism, but appeals to Yahweh to forgive his sins and to abandon his discipline of him so that he can be happy for a short while before he passes on. In the case of Ps 73, the suppliant comes to the realisation that happiness does not consist of being free from trouble and discipline, but simply in being close to Yahweh.60 It is the wicked who have an ephemeral existence and who will suddenly disappear when God judges them, while the suppliant may enjoy the true happiness of having Yahweh as his eternal portion and of being received in honour at the end. The author of Ps 39 hopes for a better dispensation during his life as stranger with Yahweh (although he yearns to be near Yahweh);61 the author of Ps 73 finds consolation in his new perspective of true happiness as simply being in the presence of Yahweh, realising that this is a privilege which will not end in death.62 It is possibly this insight which makes it bearable to simply live as a sojourner in the presence of Yahweh, since Yahweh himself takes the place of the inheritance.63

It would be difficult to argue that the author of any one of the two psalms discernibly alludes to the other psalm, but it is quite possible that the author of Ps 73 wanted to respond to the formulation of Ps 39. The complaint in Ps 39:13 that "for I am (but) a stranger with you ( )" possibly sparked the reaction in Ps 73:23 which states that "(nevertheless), I am continually with you (

)" possibly sparked the reaction in Ps 73:23 which states that "(nevertheless), I am continually with you ( )," especially in view of the image of inheritance in Ps 73:26. The shared vocabulary (

)," especially in view of the image of inheritance in Ps 73:26. The shared vocabulary (

, to name but a few) and stylistic similarities64 suggest that the two psalms possibly originated in close temporal proximity and were incorporated into the Psalter to present the reader with two possible theological perspectives on retribution that existed simultaneously. The authors of both psalms, however, seem to have been disillusioned by the "simplistic" perspective which is presented as the proper reaction to the postponement of retribution in Pss 34 and 37.

, to name but a few) and stylistic similarities64 suggest that the two psalms possibly originated in close temporal proximity and were incorporated into the Psalter to present the reader with two possible theological perspectives on retribution that existed simultaneously. The authors of both psalms, however, seem to have been disillusioned by the "simplistic" perspective which is presented as the proper reaction to the postponement of retribution in Pss 34 and 37.

3 The Connections of the Book of Job with Psalms 39 and 73

Many investigators have noted the lexical as well as thematic similarities between Job and Ps 39 and a number of them have concluded from these that there must be a literary dependence in one direction or the other.65 Will Kynes mentions the following similarities between Ps 39 and Job: The character Job and the implied author of Ps 39 have both suffered at the hand of God; they initially respond in submissive silence to avoid sinning with the tongue; their pain then overwhelms the resolve to keep silent and they speak out against God; they both complain about the brevity of human life and God's implacable wrath; they are torn between dependence on God and rejection of his antagonism; they both long for God to hear them and to leave them alone, warning God that they will soon be out of his reach. The one important difference between Ps 39 and Job is that the psalmist is aware of his sins, while Job continually insists that he is innocent.66 Kynes provides a detailed discussion of the similarities between Ps 39 and Job 10:20-21; Job 6:8-11; Job 7; as well as Job 13:28-14:6, arguing convincingly on the basis of coherence that there is a literary connection and that it is the author of Job who refers to Ps 39.67 The investigation of Kynes breaks new ground by illustrating how Job alludes in a concurring way to Ps 39. Job's allusions to a number of other psalms can be described as "parodies,"68 but Kynes does not think that this happened in the case of Job's allusions to Ps 39. According to him, "Job has the same purpose as the author of Psalm 39, to motivate God to intervene"69 and he therefore does not parody Ps 39, but rather intensifies its lament.70 According to Kynes, the treatment accorded to Ps 39 also differs from allusions to other psalms in Job, since only the character Job refers to Ps 39; his friends do not allude to Ps 39 at all.71

One of the other psalms that display close proximity to Job is Ps 73. Also in the case of the connections between Ps 73 and Job, Kynes has provided new insight by explaining how Job offers commentary on Ps 73.72 Eliphaz accuses Job in Job 22:13-14 of being one of the "wicked" to whom Ps 73:11 refers, those who say that God is ignorant.73 Further similarities between Job and Ps 7374 corroborate the notion that the author of Job intentionally referred to Ps 73.75 What is different in the case of Ps 73 (in comparison to Ps 39), however, is that both Job and his friends imply that they themselves have a kindred spirit in the author of Ps 73. Job can identify with the suppliant of the psalm's affliction, frustration, and even his hope, while he sees himself as even more righteous than the author of the psalm. The friends, in turn, make use of the derisive description of wicked people in Ps 73 as well as the description of their ephemerality, and they also think that the psalmist's description of the wicked is a fitting description of Job.76

Kynes concludes that it is because of the dialectic in Ps 73 that both Job and his friends can claim support by alluding to Ps 73. He refers to Carol Newsom who suggests that the dialogue in Job presents different points of view and that the author of Job does not openly choose sides, so that the contrasting positions are able to "address the reader with formally equivalent force."77 Job and his friends represent the opposing sides of the tensions present in the psalm and interpret Ps 73 differently to support their arguments.78 Psalm 73 thus enables the author of Job to put its conflicting ideas, those of legitimating structure while simultaneously embracing pain, into conversation with one another. The attempt to legitimate structure appears in the psalmist's continuing loyalty to his community and its institutions (73:15, 28) and of the traditional definition of purity of heart (73:1, 13). Embracing pain, in contrast, is visible in the psalmist's rejection of the traditional idea of the consequences of being pure of heart (73:1, 28 as opposed to 73:4-12). The "pure of heart" are redefined as those who continue to worship God even when they suffer.79 The book of Job thus essentially provides the same solution as Ps 73 to the existential crisis of suffering: Life is not the supreme good; the presence of God is. Job also does not reject the doctrine of retribution outright; he only rejects the strict application of it represented by the friends. To be vindicated, something which he wants above all, "Job needs some form of retribution to be operative in the world, and he clings to this hope despite his experience to the contrary."80 The same hope forms the foundation for the supplication in Ps 39 that Yahweh will stop his punishment of the speaker, and this hope is also stated more or less explicitly in Ps 39:8.

E CONCLUSION: THE YIELD FOR THE INTERPRETATION OF PSALM 39

Psalms 34, 37, 39 and 73 are all concerned with the problem of injustice, or postponed retribution, as is the book of Job. They all represent valid points of view from the second temple period, although they do not all come to the same conclusion. Psalm 34 focuses on the promise that Yahweh is aware of injustice and the suffering of the righteous and that he will put matters in order. Psalm 37 is especially concerned with the imbalance in the possession of land and the consequent deprivation of righteous people. Using the authority of Proverbs, the authors argue that the righteous will be saved, will eventually take possession of the land and will prosper rather than wicked, apostate and rich Israelites. Both psalms maintain that the righteous should not become agitated, but should put their trust in Yahweh and wait for him to act.

The author of Ps 39 seems to comment on these two, stating that it causes unendurable pain not to complain. His hope is still in Yahweh, but life is uncertain and his own life is passing away too quickly. Instead of enjoying the benefit of retribution, he experiences life as a sojourner with Yahweh and would appreciate some respite from Yahweh's discipline and some happiness before his life ends.81

The author of Ps 73 possibly responds to Ps 39 in turn. He experiences the same indignation with the prosperity of the wicked, but has come to realise that there is an inheritance which cannot be taken away; that Yahweh is his portion forever. Even if it happens only in the world to come, justice will prevail. He can, therefore, embrace pain and still be happy.

The author of Job's use of both Pss 39 and 73 corroborates this interpretation. The character Job's view closely resembles that of the implied author of Ps 39, that is why "Job" alludes to Ps 39 by claiming its authority. Job's friends do not find support in Ps 39 and consequently do not allude to it. Both "Job" and his "friends," however, find support in Ps 73. The character Job can associate with the psalmist of Ps 73, although he thinks that his innocence surpasses that of the author. The "friends" agree with the description of the wicked and their demise as it is presented in Ps 73. In their view, this description is applicable to "Job" as well.

There is not necessarily a huge gap in time between the various texts referred to in this article. In post-exilic Jerusalem, various points of view about retribution probably existed simultaneously. There was a group of people who kept on insisting that strict equivalence applied between deed and consequence, but they must have been a minority, since (as Kynes reminds us), such strict equivalence is also not entertained by Proverbs.82 In the Book of Job, strict equivalence (represented by the "friends" of Job) is made into a parody and thus rejected by the author. The character Job himself also subscribes to a view that there is retribution, but insists that it is not applied justly by Yahweh. This view, for which Ps 39 is used as justification, is also rejected in the end, since it is the view of someone who has not yet gained enough insight. In the end, the character Job gains the same insight as that of the psalmist of Ps 73, namely that keeping one's heart pure and one's hands clean are not futile actions, since happiness is found in the presence of God, whether one prospers or suffers.

In view of the author of Ps 39's possible literary inclination to allude antithetically to other texts, illness seems to have been only a guise for wisdom reflection in Ps 39.83 The purpose of the self-deliberation and prayer is to serve as a mould for wisdom reflection, similar to what also happens in Ps 73. The real problem of the author is not (only) failing health, but the crisis caused by the perceived failure of retribution. The psalm therefore seems to be an attempt to address concerns about the postponement of retribution among the faithful.

Psalm 39 could have been composed at more or less the same time as Pss 34 and 37, but in view of the literary and thematic similarities with Ps 73 and with Job and its critical view of aphorisms expressed in Pss 34 and 37, it possibly comes from a slightly later period than those two. Psalm 73 in turn seems to be a response to views which are expressed in Ps 39, while the author of Job made use of both. The intention of the author of Ps 39 was to provide guidance to fellow believers by putting his personal theological struggle into words and using the form of a supplication of a sick person for that.84 As Barbiero demonstrated, however, the redactors of the Psalter integrated the psalm into a cluster forming the conclusion of the first book of Davidic prayers, softening its acerbic and parodic impact by implying that "David's" call for help in Ps 39 was answered by Yahweh before the end of his life. In a way, the concept of retribution was vindicated, but also adapted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Samuel L. Wisdom in Transition: Act and Consequence in Second Temple Instructions. JSJSup 125. Leiden: Brill, 2008. [ Links ]

Barbiero, Gianni. Das erste Psalmenbuch als Einheit: Eine synchrone Analyse von Psalm 1-41. ÖBS 16. Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1999. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. "Psalm 37: Conflict of Interpretation." Pages 229-256 in Of Prophets' Visions and the Wisdom of Sages: Essays in Honour of R. Norman Whybray on His Seventieth Birthday. Edited by R. Norman Whybray, Heather A. McKay, and David J. A. Clines. Sheffield: JSOT, 1993. [ Links ]

Burkes, Shannon. God, Self, and Death: The Shape of Religious Transformation in the Second Temple Period. JSJSup 79. Leiden: Brill, 2003. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard J. "What does the Psalmist ask for in Psalms 39:5 and 90:12?" JBL 119 (2000): 59-66. [ Links ]

Craigie, Peter C. and Marvin E. Tate. Psalms 1-50. WBC 19. Nashville: Nelson Reference & Electronic, 2004. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James L. "The Journey from Voluntary to Obligatory Silence (Reflections on Psalm 39 and Qoheleth)." Pages 177-191 in Focusing Biblical Studies: The Crucial Nature of the Persian and Hellenistic Periods: Festschrift in Honor of Douglas A. Knight. Edited by Jon L. Berquist and Alice Hunt. LHBOTS 544. London: T & T Clark, 2012. [ Links ]

Deissler, Alfons. Psalm 119 (118) und seine Theologie: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der anthologischen Stilgattung im Alten Testament. MTSt 1/11. München: K. Zink, 1955. [ Links ]

Dietrich, Walter, and Samuel Arnet, eds. Konzise und aktualisierte Ausgabe des Hebräischen und Aramäischen Lexikons zum Alten Testament (KAHAL). Leiden: Brill, 2013. [ Links ]

Gosse, Bernard. L'influence du livre des "Proverbes" sur les redactions bibliques :à l'époque Perse. Paris: Gabalda, 2008. [ Links ]

Hengstenberg, Ernst W. Commentary on the Psalms. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1863. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar and Erich Zenger, Die Psalmen: Psalm 1-50. NEchtB 29. Würzburg: Echter Verlag, 1993. [ Links ]

______. Psalms 2: A Commentary on Psalms 51-100. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Edited by Klaus Baltzer. Hermen. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005. [ Links ]

Irsigler, Hubert. "Quest for Justice as Reconciliation of the Poor and the Righteous in Psalms 37, 49 and 73." SK 19 (1998): 584-604. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Psalmen 1-59. BKAT. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978. [ Links ]

Kynes, Will. "Beat Your Parodies into Swords, and Your Parodied Books into Spears: A New Paradigm for Parody in the Hebrew Bible." BibInt 19 (2011): 276-310. [ Links ]

______. "Job and Isaiah 40-55: Intertextualities in Dialogue." Pages 94-105 in Reading Job Intertextually. Edited by Katherine Dell and Will Kynes. LHBOTS 574. London: Bloomsbury, 2012. [ Links ]

______. My Psalm has Turned into Weeping: Job's Dialogue with the Psalms. BZAW 437. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012. [ Links ]

McCann, Clinton, Jr. "Psalm 73: A Microcosm of Old Testament Theology." Pages 247-257 in The Listening Heart. Edited by Kenneth G. Hoglund, Elizabeth F. Huwiler, Jonathan T. Glass and Roger W. Lee. JSOTSup 58. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Newsom, Carol. The Book of Job: A Contest of Moral Imaginations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Spangenberg, Izak J. J. "Psalm 73 and the Book of Qoheleth." OTE 29 (2016): 151-175. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Leiden: Brill, 2006. [ Links ]

Walton, John H. "Retribution." Pages 647-655 in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. Edited by Tremper Longman III and Peter Enns. Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. Die Psalmen 1 Bis 72. Vol. 1 of Werkbuch Psalmen. Edited by Beat Weber. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001. [ Links ]

Wilson, Gerald H. Psalms. Vol. 1. NIVAC. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 3/01/2017

Peer-reviewed: 10/02/2017

Accepted: 5/05/2017

Phil J. Botha, Department of Ancient Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria, 0002, Pretoria. Email: phil.botha@up.ac.za.

1 With this article, I would like to pay tribute to the work and legacy of Izak J. J. Spangenberg, a prominent South African OT scholar and theologian. His investigation of Ps 73 is especially pertinent to this article and although I differ from some points of view expressed by him, I have a high regard for his work on wisdom texts and on a number of psalms in particular.

2 I beg to differ from those investigators who still contend that the psalm is a "supplication for relief from an unspecified affliction" as, for example, Crenshaw does. Cf. James L. Crenshaw, "The Journey from Voluntary to Obligatory Silence (Reflections on Psalm 39 and Qoheleth)," in Focusing Biblical Studies: The Crucial Nature of the Persian and Hellenistic Periods: Festschrift in honor of Douglas A. Knight, ed. Jon L. Berquist and Alice Hunt, LHBOTS 544 (London: T&T Clark, 2012), 186-190, 182.

3 Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalmen 1-59, BKAT (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978), 456 says that it ends in despair and has dived into a darkness without equal ("verzweifelt bricht das Lied ab; es ist hineingetaucht in ein Dunkel ohnegleichen").

4 E.g., Peter C. Craigie and Marvin E. Tate, Psalms 1-50, WBC 19 (Nashville: Nelson Reference & Electronic, 2004), 310-311 who say that "[t]he central concern of the psalm is that of an appropriate perspective within which to live out the single, but short human life which each person has received." This perspective entails that "life is extremely short and what matters above all else is the relationship with God."

5 E.g., Gianni Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch als Einheit: Eine synchrone Analyse von Psalm 1-41, ÖBS 16 (Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1999), who sees Ps 39 as an open psalm ("offener Psalm"), one which should not be read without Ps 40, since it could then appear blasphemous. Barbiero's views on the meaning of the psalm will be discussed below.

6 For an excellent exposition of the concept of "retribution" in the ANE as well as in the Wisdom Literature of the HB (Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and Job), cf. John H. Walton, "Retribution," DOTWPW, 647-655. In Walton's definition, "the retribution principle was an attempt to understand, articulate, justify and systematize the logic of God's interaction in the world" (p. 647).

7 The ESV (English Standard Version) was used as the basis for all translations in this article, but it was freely adapted as the author saw fit in order to follow the Hebrew more closely. The verse numbers are those of MT and not the ESV.

8 The form  is understood as the preposition plus the adjective

is understood as the preposition plus the adjective  , used substantively, thus "I remained silent (far) from the good, without good." The dictionaries suggest that it is an inf. cstr. of

, used substantively, thus "I remained silent (far) from the good, without good." The dictionaries suggest that it is an inf. cstr. of  , "to speak," thus "without speaking." Cf. "

, "to speak," thus "without speaking." Cf. " ," KAHAL: 193, 195. In view of the many repetitions of

," KAHAL: 193, 195. In view of the many repetitions of  in the cluster, the redactors of the Psalter, however, probably understood it as the adjective. Cf. also Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 652, who consequently translates it with "Schweigen 'weg vom Glück.'" Crenshaw, "Journey," 179 translates "I refrained from good" and remarks that the hiphil of

in the cluster, the redactors of the Psalter, however, probably understood it as the adjective. Cf. also Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 652, who consequently translates it with "Schweigen 'weg vom Glück.'" Crenshaw, "Journey," 179 translates "I refrained from good" and remarks that the hiphil of  can mean to show inactivity.

can mean to show inactivity.

9 The root  is often used in the HB to refer to an object or quality causing envious desire because it is out of bounds to the observer. The occurrence of the same grammatical form

is often used in the HB to refer to an object or quality causing envious desire because it is out of bounds to the observer. The occurrence of the same grammatical form  in Job 20:20, possibly an allusion to Ps 39:12, refers to the treasures which a wicked person accrues through unquenchable greediness; treasures which nevertheless cannot save him from judgement. It thus refers to the riches some heap up during their life (cf. the parallel in v. 7).

in Job 20:20, possibly an allusion to Ps 39:12, refers to the treasures which a wicked person accrues through unquenchable greediness; treasures which nevertheless cannot save him from judgement. It thus refers to the riches some heap up during their life (cf. the parallel in v. 7).

10 Pieter van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 390 demarcates 2-4.5-7 and 8-11.12-14. This is very similar to the segmentation proposed here. However, I do not agree with the separation between 11 and 12, since  "sin" in 12a links back to

"sin" in 12a links back to  in 9a, while "Yahweh" introduces a new segment in 13. Beat Weber, Die Psalmen 1 Bis 72, vol. 1 of Werkbuch Psalmen, ed. Beat Weber (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001), 186 demarcates 2-3.4-6, 7-9.10-12 and 13-14. He interprets 6c and 12c as a refrain. Cf. the arguments against this in Van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes, 395.

in 9a, while "Yahweh" introduces a new segment in 13. Beat Weber, Die Psalmen 1 Bis 72, vol. 1 of Werkbuch Psalmen, ed. Beat Weber (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001), 186 demarcates 2-3.4-6, 7-9.10-12 and 13-14. He interprets 6c and 12c as a refrain. Cf. the arguments against this in Van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes, 395.

11 Cf. 2 Sam 7:25, 28; 1 Kgs 3:7; 8:25, 26; 1 Chr 29:13; 2 Chr 1:9; 6:16, 17, 40; Neh 9:32; Isa 64:7; Jonah 4:3.

12 39:5 "make me know my end"; 39:9 "Deliver me ..."; "Do not make me the scorn 39:11 "Remove your stroke from me 39:13 "Hear my prayer ... give ear to my cry; do not be silent"; 39:14 "Remove your gaze from me ..."

13 This explanation already suggests that the psalm is a wisdom reflection rather than a formulaic prayer. As a self-deliberation, it is strongly reminiscent of the style of Qoheleth. Cf. Eccl 2:1, 2, 15; 3:17, 18; 6:3; 7:23; 8:14; 9:16.

14 Cf. Jer 20:9 where the same thought occurs.

15 Cf. Zech 9:3 and Job 27:16.

16 Cf. Ps 73:14; Job 19:21.

17 Cf. Job 13:28; Isa 50:9; 51:8; Hos 5:12.

18 Cf. Lev 25:23; 1 Chr 29:15.

19 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 590-628. Gerald H. Wilson, Psalms, vol. 1, NIVAC (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002), 625 has also pointed out the connections between 38 and 39 and also between 39 and 40 and 41 respectively. He says that these connections "suggest that these four psalms have been stitched together to form the conclusion of book 1 of the Psalter."

20 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 642-653.

21 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 596.

22 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 597-599.

23 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 590.

24 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 600.

25 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 603.

26 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 595-596.

27 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 603-605.

28 Will Kynes, "Job and Isaiah 40-55: Intertextualities in Dialogue," in Reading Job Intertextually, ed. Katherine Dell and Will Kynes, LHBOTS 574 (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 94-105 notes that (p. 94), in intertextuality, one has to distinguish between the approach which is interested in the intentions of authors and thus involves the relative dates of texts, and the other approach which considers texts part of an infinite web of meaning which is unconcerned with such matters.

29 Kynes, "Job and Isaiah 40-55," 94-105.

30 Parody in the HB does not necessarily involve subversion or ridicule of the context to which it refers; it often constitutes a reaffirmation of that context in order to ridicule the situation to which it refers instead. Cf. the discussion and the examples provided by Will Kynes, "Beat Your Parodies into Swords, and Your Parodied Books into Spears: A New Paradigm for Parody in the Hebrew Bible," BibInt 19 (2011): 276-310.

31 Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Die Psalmen: Psalm 1-50, NEchtB (Würzburg: Echter Verlag, 1993), 14-15.

32 Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalm 1-50, 14.

33 Cf. Ps 16:7, 11; 19:8-12; 23:3; 25:4-5, 10, 12, 14; 33:4; 34:12-15 (where the psalmist acts as teacher of wisdom); 37:31, 34 (where the way of wisdom is described as the way of Yahweh); 40:9. Cf. also the very helpful discussion in Bernard Gosse, L'Influence du Livre des "Proverbes" sur les rédactions Bibliques á l'époque Perse (Paris: Gabalda, 2008), 63-73.

34 For a description of this style in the Psalter, cf. Alfons Deissler, Psalm 119 (118) Und seine Theologie: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der anthologischen Stilgattung im Alten Testament, MTSt (München: K. Zink, 1955), 19-31. Deissler singles out wisdom psalms, but also the so-called enthronisation psalms ("Thronbesteigungspsalmen").

35 For an overview, cf. Will Kynes, My Psalm has Turned into Weeping: Job's Dialogue with the Psalms, BZAW 437 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), 122-123. James L. Crenshaw points out the thematic and syntactical similarities between Ps 39 and Ecclesiastes without proposing dependence of the one on the other. Cf. Crenshaw, "Journey," 186-190.

36 Kynes, My Psalm, 123 notes that several commentators around the turn of the twentieth century considered the similarities in lexical use and themes as evidence that the psalmist was dependent on Job. Hengstenberg argued for the opposite, namely that the author of Job was clearly acquainted with Ps 39. Cf. Kynes, My Psalm, 123, and Ernst W. Hengstenberg, Commentary on the Psalms, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1863), 63. Hossfeld and Zenger note the parallels with Job and Ecclesiastes, but seem to think that the similarities can be explained as the shared language and imagery of late wisdom thinking. Cf. Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalm 1-50, 249-251.

37 His 2012 revised publication of a doctoral thesis, Kynes, My Psalm, 122-141.

38 Although he does not put it so decisively, stating "I believe the evidence tips slightly in the direction of Job's dependence on the psalms ..." Kynes, My Psalm, 129. His argument rests on the level of agreement between the texts, the cumulative case of the book of Job referring to many other psalms, and the fact that it makes better sense for Job to intensify the complaints of the psalmist rather than the psalmist's mollifying of Job's complaints to advocate a more cautious piety.

39 Cf. Will Kynes, "Job and Isaiah 40-55," 94-105.

40 Ps 34:5, 7, 8, 16, 18-21, 23.

41 Ps 34:23.

42 Ps 34:10, 11, 13.

43 Ps 34:17, 22.

44 Ps 34:14-15, 19. The upright are admonished to avoid wrong speech (34:14) and from taking revenge on their own (34:15).

45 According to Hubert Irsigler, "Quest for Justice as Reconciliation of the Poor and the Righteous in Psalms 37, 49 and 73," SK 19 (1998): 584-604, 585-586, the socio-economic problems of the 5th to 4th centuries BCE and the crisis it caused for the faithful are also visible in texts such as Mal 2:17; 3:13-21; Job 21:9-21, 24; Jer 12:1-4; Prov 3:31; 23:17; 24:1 and 19. Psalm 37:1-2 has most certainly taken Prov 3:31 and 24:1 and 19 as cues for its call to calm.

46 Irsigler, "Quest for Justice," 588. Walter Brueggemann, "Psalm 37: Conflict of Interpretation," in Of Prophets' Visions and the Wisdom of Sages: Essays in Honour of R. Norman Whybray on His Seventieth Birthday, ed. R. Norman Whybray, Heather A. McKay, and David J. A. Clines (Sheffield: JSOT, 1993), 239 contends that Ps 37, in a "first reading," constitutes "a powerful practice of social ideology in the service of landed interests" (his emphasis). I fail to see how Ps 37 can be read as "the voice of a self-assured property-owning class" (p. 234). It was rather intended from the beginning to address concerns about the failure of retribution.

47 Ps 37:1, 7-8, 27.

48 Ps 37:7.

49 Ps 37:7, 11, 16, 19, 24-26, 29, 39.

50 Ps 37:2, 9, 10, 13, 15, 17, 20, 22, 28, 34, 36, 38.

51 Ps 37:4, 5, 69, 11, 18, 22, 26, 27, 29, 34, 37.

52 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 651, has also noted this tension: "Zwischen Ps 37 und Ps 39 steht die bittere Erfahrung von Ps 38. Der Psalmist kann jetzt nich mehr die alte Lehre des 'Tun-Ergehen-Zusammenhangs' ohne weiteres akzeptieren. Wie Kohelet und Ijob sieht er, dass die Wirklichkeit anders ist." Within the cluster 35-41, 37 and 39 were also positioned to correspond palindromic to one another around 38 as centre. Cf. Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 543-544.

53 This is possibly a direct response to the promise of Ps 34:13.

54 The wicked do not pose a threat to him (as some investigators think), but he does not want to criticise Yahweh (and thus sin) in their presence.

55 The "desires" ( ) of Ps 37:4 form a parallel to the "desire" (

) of Ps 37:4 form a parallel to the "desire" ( ) of humankind in Ps 39:12, but the promise of Ps 37:4 is contradicted by Ps 39:12.

) of humankind in Ps 39:12, but the promise of Ps 37:4 is contradicted by Ps 39:12.

56 This also seems to be a direct response to Ps 37:36.

57 Ps 37:7, "Be still before Yahweh and wait patiently for him." The verse uses  hithpoel, but it should probably be

hithpoel, but it should probably be  hiphil. Cf. the suggestion to read the form as

hiphil. Cf. the suggestion to read the form as  in KAHAL: 162.

in KAHAL: 162.

58 Barbiero, Das erste Psalmenbuch, 652-653 refers further also to the contrasting use of  in 37:16 (cf. 37:3, 27) and 39:3 (understood as a noun); "smoke"

in 37:16 (cf. 37:3, 27) and 39:3 (understood as a noun); "smoke"  ) in 37:20 and "breath of air" (

) in 37:20 and "breath of air" ( ) in 39:6, 12; the wicked as sinners (

) in 39:6, 12; the wicked as sinners ( ) in 37:38 and the sins (

) in 37:38 and the sins ( ) of the suppliant in 39:9.

) of the suppliant in 39:9.

59 Cf. Irsigler's comparison of Pss 39 and 73 as two attempts to guide the pious to a renewed trust in Yahweh. Irsigler, "Quest for Justice," 584-604.

60 The inclusio created by repeating  from the opening aphorism in the last verse shows how the author revisits and adjusts the wisdom paradigm. Cf. Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "Psalm 73 and the Book of Qoheleth," OTE 29 (2016): 151-175, 154-155. This is corroborated by the chiasmus between

from the opening aphorism in the last verse shows how the author revisits and adjusts the wisdom paradigm. Cf. Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "Psalm 73 and the Book of Qoheleth," OTE 29 (2016): 151-175, 154-155. This is corroborated by the chiasmus between  and

and  in 73:2-3 and 27-28. Cf. Spangenberg, "Psalm 73," 161-162.

in 73:2-3 and 27-28. Cf. Spangenberg, "Psalm 73," 161-162.

61 On the one hand he feels himself to be handed over into the power of God (as a stranger), and yet he is close to God (he is with God). Cf. also Weber, Werkbuch 1, 187.

62 Spangenberg, "Psalm 73," 164 is mistaken (in my view) in thinking that the psalmist merely states that "after all the suffering and spiritual agony, God will restore him to honour in this life." The psalmist holds on to the presence of God even when his "physical and psychic existence" (his "flesh" and his "heart," 73:26b) may disappear. Samuel L. Adams, Wisdom in Transition: Act and Consequence in Second Temple Instructions, JSJSup 125 (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 150 points out that Qoheleth's distinction between animals and humans in death (Qoh 3:21, in which he denies the possibility of an afterlife) probably reflects a reference to Ps 49:11-21 and Ps 73:22-24 where it is implied that certain humans will die like animals, while righteous individuals could possibly be granted eternal life. Cf. also Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 2: A Commentary on Psalms 51-100, trans. Linda M. Maloney, ed. Klaus Baltzer, Hermen (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 236. The parallel use of  in the sense of a transposition to a place beyond the power of death in Ps 49:16 and Ps 73:24 also fits in with this. The

in the sense of a transposition to a place beyond the power of death in Ps 49:16 and Ps 73:24 also fits in with this. The  of the wicked in 73:17 possibly refers to their "future" destination and serves as a response to the antithesis between the righteous and the wicked in Ps 37:37-38.

of the wicked in 73:17 possibly refers to their "future" destination and serves as a response to the antithesis between the righteous and the wicked in Ps 37:37-38.

63 Ps 73:26  - "my share of possession." Cf. also Num 18:20; Ps 16:5; 119:57; 142:6. Deut 32:9 uses the reverse of this image.

- "my share of possession." Cf. also Num 18:20; Ps 16:5; 119:57; 142:6. Deut 32:9 uses the reverse of this image.

64 E.g., the generic reference to humanity as  (39:6, 12; 73:5); the use of the noun

(39:6, 12; 73:5); the use of the noun  (39:6, 14; 73:2, 4, 5); the repeated use of the particle

(39:6, 14; 73:2, 4, 5); the repeated use of the particle  (39:6, 7, 12; 73:1, 13, 18); the use of

(39:6, 7, 12; 73:1, 13, 18); the use of  in the sense of self-deliberation (39:2; 73:15); the emphatic use of the first person singular pronoun

in the sense of self-deliberation (39:2; 73:15); the emphatic use of the first person singular pronoun  (39:5, 11; 73:2, 22, 23, 28); the use of the third person singular feminine pronoun as copula (39:8; 73:16); the use of the exclamation

(39:5, 11; 73:2, 22, 23, 28); the use of the third person singular feminine pronoun as copula (39:8; 73:16); the use of the exclamation  (39:6; 73:12, 15, 27); the importance of the concept of "knowing" (39:5, 7; 73:11, 16, 22); the use of the verb

(39:6; 73:12, 15, 27); the importance of the concept of "knowing" (39:5, 7; 73:11, 16, 22); the use of the verb  in the sense of "perish" (39:11; 73:26); the use of "tongue" to represent "speech" (39:2, 4; 73:9); the reference to suffering with the stem

in the sense of "perish" (39:11; 73:26); the use of "tongue" to represent "speech" (39:2, 4; 73:9); the reference to suffering with the stem  (39:11; 73:5, 14); the use of

(39:11; 73:5, 14); the use of  in the sense of "shadowy existence" (39:7; 73:20); the use of the rare word

in the sense of "shadowy existence" (39:7; 73:20); the use of the rare word  , "punishment" (39:12; 73:14).

, "punishment" (39:12; 73:14).

65 Kynes, My Psalm, 122 refers to a number of exegetes who have noted the similarities, beginning with Calvin.

66 Cf. Kynes, My Psalm, 122.

67 Kynes, My Psalm, 122-141.

68 Kynes, "Beat Your Parodies," 276-310 pleads for a new definition of "parody" which does not necessarily entail ridicule or humour. Parody in Job often appeals to certain psalms as a source of authority to ridicule not the earlier text, but the situation described in the text which alludes to the earlier source.

69 Kynes, My Psalm, 130. In this regard, he is referring to the character Job in the book of Job.

70 Kynes, My Psalm, 136-137.

71 Kynes (My Psalm, 138-139) thinks that the friends "may have been uncomfortable appealing to such a stark lament psalm as an authority, since it would undercut their argument."

72 In the past, some scholars have argued that Ps 73 comments on Job and others thought that the influence was from Ps 73 on Job. The possibility of direct dependence between them has, up to the investigation of Kynes, not been pursued fully. Cf. Kynes, My Psalm, 161 for an overview of the opposing views.

73 Kynes, My Psalm, 162-166.

74 He compares Job 7:18 and Ps 73:14; Job 9:29-31 and Ps 73:13; Job 15:27 and Ps 73:7; Job 18:3 and Ps 73:22; Job 18:11 and 14 and Ps 73:19; Job 20:8 and Ps 73:20; Job 19:25-27 and Ps 73:23-26; Job 21:13-14 and Ps 73:11; and Job 23:11 and Ps 73:2.

75 Kynes, My Psalm, 162-175.

76 Kynes, My Psalms, 174-175.

77 Kynes, My Psalms, 175. He refers to Carol Newsom, The Book of Job: A Contest of Moral Imaginations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 86-87.

78 Kynes, My Psalm, 175.

79 Kynes, My Psalm, 176, with reference to the description of Clinton McCann, Jr., "Psalm 73: A Microcosm of Old Testament Theology," in The Listening Heart, ed. Kenneth G. Hoglund, et al, JSOTSup 58 (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1987), 251-252.

80 Kynes, My Psalm, 179.

81 Adams suggests that Ps 39:4-6 is one of the pericopes in the Psalter that contain speculation on the possibility of an afterlife (the others mentioned are 49:10-15; 89:47-48; 90:3-6, 9-10; 103:13-16; 144:3-4; 146:3-4). He refers to the list provided by Shannon Burkes, which does not include Ps 73:24-26 as it should, while I would be very hesitant to include Ps 39:4-6. Cf. Adams, Wisdom in Transition, 95 and Shannon Burkes, God, Self, and Death: The Shape of Religious Transformation in the Second Temple Period, JSJSup 79 (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 30-31.

82 Proverbs contains texts that attach positive value or acceptance to being poor (e.g. Prov 14:31; 19:17; 22:2) and thus contradicts a direct equivalence between wealth and righteousness. Kynes, My Psalm, 177.

83 Kynes remarks that the mix of aspects of individual lament motivated by sickness and the elements of reflective wisdom renders a cultic setting for Ps 39 "uncertain" (Kynes, My Psalm, 140). In my view, it is highly improbable that the psalm was composed for or used in a cultic setting. Kraus (Psalmen 1-59) displays a strange ambivalence in this regard. On the one hand, he asserts that it really is someone suffering from terminal illness who is praying in the psalm (p. 455); on the other hand, he observes that the specific reference only served as impetus for fundamental reflection and a pronouncement on teaching (p. 453). Beat Weber, Werkbuch 1, 187 similarly considers the threat of imminent death, as a consequence of illness, great age, or both, to form the background of the psalm. The same error (in my view) is made by Richard J. Clifford who interprets 39:5 as "a request to know the term of the psalmist's affliction rather than the term of the psalmist's life." Cf. Richard J. Clifford, "What Does the Psalmist Ask for in Psalms 39:5 and 90:12?" JBL 119 (2000): 59-66, 61.

84 Kraus, Psalmen 1-59, 453 says, "Die Reflexion und Meditation der Lehrdichtung gibt zu erkennen, dass der konkrete Bezug nur Anlass und auslösendes Motiv zur ins Grundsätzliche strebenden Besinnung und Lehräusserung gewesen ist."