Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.30 no.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n1a3

ARTICLES

Younger-brother motif in Genesis as an object of love and hatred in the family: Tensions, conflicts and reflection for the contemporary African family1

Emmanuel Kojo Ennin Antwi

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

ABSTRACT

The younger-brother motif in the book of Genesis reflects tension and conflict in a family. The younger brother in some cases becomes an object of hatred to his siblings but is loved by the parent and this has devastating consequences for the family. This paper analyses five younger brother-motif texts, highlighting the various types of family conflicts demonstrated in the narratives. It further explores the theological significance of the use of the motif in Genesis. The family problems raised in the narratives also persist in the African family. The paper recommends, among others, going back to the traditional moral training of the African child to build the conscience as a step to resolution of the conflicts in the contemporary African family.

Keywords: Younger-brother Motif, Genesis, Tension, Conflicts, Rivalry, African Family.

A INTRODUCTION

The book of Genesis is a sacred history of the beginnings of creation and how God dealt with humankind from the very beginning. It contains some narratives with tensions and conflicts within human society. The younger-brother motif2in Genesis, found within the family setting has some of these tensions and conflicts. These narratives which have elements of love for the younger brother, at the same reveal an element of hatred. Forming as it were a pattern within the book, the motif elicits ambivalent reactions of love and hatred which cause tensions in the narratives themselves. This situation originates and reflects conflicts and rivalry among family members. One wonders why an element of love is responded with hatred in the narratives. It is of interest to delve into the related texts to find out the intention of the narrators' use of the motif and to see how the tensions and conflicts are resolved within the narratives. I will analyse some of the younger-brother motif texts in Genesis, highlighting the various forms of family conflicts in them.3 I will then deduce the resolutions of these conflicts in the narratives and discuss their hermeneutical implications for the contemporary African family.

B EXAMINATION OF YOUNGER-BROTHER MOTIF TEXTS IN THE BOOK OF GENESIS

Five texts from the book of Genesis in which we find the younger-brother motif with tensions and conflicts among family members are the stories of Cain and Abel in Gen 4:1-16, Isaac and Ishmael in Gen 16 and 21:1-21, Jacob and Esau in Gen 25:20-34; 27:1-45, Joseph and his brothers in Gen 37:1-11 (37-50) and Ephraim and Manasseh in Gen 48:7-19.4 These texts clearly illuminate the various forms of family conflicts among siblings, rivals, parents and sons, parents, brothers of different mothers, and grandfather and son. I will examine these texts and point out the tensions, conflicts and resolutions within them.

1 Cain and Abel (Gen 4:1-16)

The Yahwistic material of the Cain and Abel narrative in Gen 4:1-16, which forms part of the narrative block of Gen 4:1-26,5 is one of the most complicated stories in the OT.6

The narrative opens with the first man and woman created in a family context. The first act of procreation according to the text is signalled by the birth of Cain. The narrative continues with the birth of Abel, who is described as the brother of Cain. The text indicates that Abel was the younger brother of Cain in the statement, ... and again she gave birth to his brother" in 4:2. In many instances, Abel is referred to as the brother of Cain in the narrative.7 The repetitive use of

... and again she gave birth to his brother" in 4:2. In many instances, Abel is referred to as the brother of Cain in the narrative.7 The repetitive use of  "his brother" and

"his brother" and  "your brother" is the narrator's style of putting emphasis on the fraternal relationship between Cain and Abel. This fraternal relationship is broken with Cain's reaction to his younger brother in 4:8. The cause of the conflict between the brothers has been attributed to the acceptance of the offering of Abel and the non-acceptance of that of Cain.8 The narrator presents the supposed acceptance of the sacrifice in two antithetical statements: "And Yhwh looked upon Abel and upon his offering but Cain and his offering he did not regard" in 4:4b-5a. Tension arises in the narrative as God had regard for the offering of Abel but had no regard for that of Cain. One of the reasons given for the "acceptance" of the sacrifice of Abel and the "non-acceptance" of that of Cain is that the narrator used the story to draw polemical undertones against the sedentary culture in favour of the nomadic one.9 Others read into the text and present Abel as taking the best of his firstlings for his sacrifice whilst Cain presented the worst of the produce from his farm.10 The consequence of the acceptance of the sacrifice of Abel was the anger of Cain which might have been demonstrated in the murder of his younger brother as presented in Gen 4:8.

"your brother" is the narrator's style of putting emphasis on the fraternal relationship between Cain and Abel. This fraternal relationship is broken with Cain's reaction to his younger brother in 4:8. The cause of the conflict between the brothers has been attributed to the acceptance of the offering of Abel and the non-acceptance of that of Cain.8 The narrator presents the supposed acceptance of the sacrifice in two antithetical statements: "And Yhwh looked upon Abel and upon his offering but Cain and his offering he did not regard" in 4:4b-5a. Tension arises in the narrative as God had regard for the offering of Abel but had no regard for that of Cain. One of the reasons given for the "acceptance" of the sacrifice of Abel and the "non-acceptance" of that of Cain is that the narrator used the story to draw polemical undertones against the sedentary culture in favour of the nomadic one.9 Others read into the text and present Abel as taking the best of his firstlings for his sacrifice whilst Cain presented the worst of the produce from his farm.10 The consequence of the acceptance of the sacrifice of Abel was the anger of Cain which might have been demonstrated in the murder of his younger brother as presented in Gen 4:8.

Tensions in the text come along with questions. Was the "acceptance" of the sacrifice of Abel due to a special love of God for the younger brother Abel? Was the murder of Abel aroused out of jealousy or hatred on the part of his elder brother? The narrative is silent on the first question. However, the first rebuke in the MT in Gen 4:7 seems to indicate that Cain did not do well. The Targums present a debate that went on between Cain and Abel before the fratricide in 4:8-16.11 In this debate, the Targums present Cain as having no belief in good deeds as a prerequisite for judgement and so his offering was not accepted. Abel, on the other hand, believed in mercy and judgement and knew that his offering was accepted because his deeds were better than that of Cain.

Like the consequence of the fall of their parents in the preceding narrative in Gen 3, the story ends with Cain being driven away from Yhwh's presence. The parents of the two brothers leave the scene after their birth only to resurface after the death of Abel and the banishment of Cain. The narrator does not indicate any role that the parents played in the interactions between the children. Nonetheless, one theological import that we identify in this text in relation to the fall of the parents is that the sin of the parents is transmitted to the children in the primeval history. This is affirmed by Richardson in his suggestion that the Cain-Abel narrative in Gen 4:1-16 is perhaps another form of the truth of the fall of humankind presented in the preceding narrative, though the details in both stories cannot be harmonised.12 The curse incurred by Cain, after the fratricide, recalls the curse in the fall of humankind in the Garden of Eden. The consequence of the act of the parents in the fall narrative in Gen 3 continues in the subsequent story in Gen 4. The conflict of the first created human pair with God and its consequences extends to the conflict between one another as exemplified by our text. This continues to characterise the conflict motifs in Genesis.13

2 Isaac and Ishmael (Gen 16; 21:1-21)

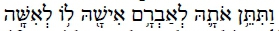

Another narrative in which one finds the younger-brother motif in Genesis is the story of Isaac and Ishmael in chs. 16 and 21:1-21. Gen 16 pertains to the birth of Ishmael and consists of mostly Priestly material with a few Yahwist insertions.14 Gen 20:1-21 on the other hand is a mixture of Priestly, Yahwist and Elohist material.15 In these texts, Isaac is never referred to as "the brother of Ishmael." The word  "brother" never occurs in the text in reference to Isaac and Ishmael. However, the word is implied in the brothers' relationship to Abraham in the text-situation. Both children are referred to as the sons of Abraham The narrative presents Isaac as the son of Abraham in Gen 21:25. In Gen 16:15-16 and Gen 21:9, the narrator presents Ishmael also as a son born to Abraham. His mother is presented in Gen 16:3c as the wife of Abraham in the statement

"brother" never occurs in the text in reference to Isaac and Ishmael. However, the word is implied in the brothers' relationship to Abraham in the text-situation. Both children are referred to as the sons of Abraham The narrative presents Isaac as the son of Abraham in Gen 21:25. In Gen 16:15-16 and Gen 21:9, the narrator presents Ishmael also as a son born to Abraham. His mother is presented in Gen 16:3c as the wife of Abraham in the statement  " ... she gave her to Abram her husband as his wife" with Sarah as the subject.16

" ... she gave her to Abram her husband as his wife" with Sarah as the subject.16

Sarah gave her Egyptian slave maid, Hagar, to Abram to bear a child on her behalf as a result of her barrenness. This practice of surrogate motherhood whereby a wife could give her maid servant to her husband to bear children on her behalf due to her sterility was acceptable in the ANE.17 Traces of such a custom can be found in the code of Hammurabi, Nuzi and Neo-Assyrian texts.18This marriage custom characterises the stories about the matriarchs such as Rachel and Leah who gave their maids Bilhah and Zilpah respectively to their husband Jacob when they could not give birth. The rationale behind such a custom was to produce an heir. One of the main purposes of marriage in the biblical times was to produce an heir to take over the family inheritance.19Consequently, barrenness was a cause of worry in the family.

Comparing the birth narratives of Ishmael and Isaac presented in Gen 16 and 21 respectively, one can identify that the image of Isaac presented in the narrative is more positive than that of Ishmael. Isaac is the son of the free wife Sarah that Abram took for himself, while Ishmael is the son of the Egyptian slave maid given to Abram as a wife by Sarah. Though both of them were named by Abraham and were presented as his sons, indicating the recognition of his paternity, it was Isaac who received circumcision. Abraham had a great feast on the day that Isaac was weaned, but this was not said of Ishmael. The celebration of weaning a child was a great family festivity.20

The conflicts in these narratives are centred on the wives. The reader can recognise tensions in the texts in the relationship between Sarah and her slave maid, Hagar, who gave birth to her husband's son Ishmael. In the first text, Hagar was driven into the wilderness because she was accused of looking on Sarah with contempt. Sarah herself had given Hagar to Abram her husband as a wife due to her barrenness. The action of Hagar after her conception evokes a reaction of conflict from Sarah. This conflict extends to the son that Hagar bore to Abram.

No element of hatred or jealousy is found in the interaction between the two sons of Abraham as presented in the second text. The tension arises in Gen 21:9 as Sarah, the wife of Abraham identifies Ishmael playing, perhaps with Isaac. This verse that contains the tension has some textual complications. It is not clear from the MT whether Ishmael was playing with Isaac or not.  which is a piel participle of the verb

which is a piel participle of the verb  , with the qal form meaning "to laugh" and the piel form meaning "to make sport" or "to play"21 lacks the complement "with her son." The Septuagint (LXX/Greek Text) has in addition "μετάΙσαακτου νιου αύτης" "with Isaac her son." Scholarly interpretation of

, with the qal form meaning "to laugh" and the piel form meaning "to make sport" or "to play"21 lacks the complement "with her son." The Septuagint (LXX/Greek Text) has in addition "μετάΙσαακτου νιου αύτης" "with Isaac her son." Scholarly interpretation of  has been torn between either "to mock" or "to play."22 Speiser opines that the original version might have had the addition of "with her son Isaac."23 Accepting this view might imply that the narrator presents the two sons as being able to play together in Gen 21:9. This view is affirmed by Von Rad.24

has been torn between either "to mock" or "to play."22 Speiser opines that the original version might have had the addition of "with her son Isaac."23 Accepting this view might imply that the narrator presents the two sons as being able to play together in Gen 21:9. This view is affirmed by Von Rad.24

Sarah's request to chase Hagar away from the house was motivated by her desire not to have the son of the slave girl share in the inheritance of her son Isaac.25 According to some laws of the ANE, a son born to a slave maid had the right of inheritance and could renounce that right of inheritance in exchange for his freedom. In relation to this practice, Sarna explains that Sarah's intention to see Hagar and the son driven out of the family was a means for the son to renounce his inheritance in order to acquire their freedom.26 The narrator brings in the intervention of God as a resolution to the conflict within the narrative in Gen 21:12-13. God affirms Abram's decision to chase his son Ishmael and his mother away.

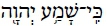

The image of God presented in the texts is worth mentioning. Both mothers receive favour from God in different ways. The barrenness of Sarah which begins the narrative concludes with the fulfilment of God's promise to Abram to give birth to a son which resolves the problem of her barrenness. In the birth narrative of Ishmael in Gen 16:11, the messenger of Yhwh instructs Hagar to call the son "Ishmael" with a reason given in the £i-clause  "

" because Yhwh has heeded to your affliction." In Gen 21, Hagar again experiences the love of God in the wilderness as God listens to her affliction.

because Yhwh has heeded to your affliction." In Gen 21, Hagar again experiences the love of God in the wilderness as God listens to her affliction.

3 Jacob and Esau (Gen 25:19-34; 27:1-45)

Gen 25:19-34 and 27:1-45 form another narrative on the younger-brother motif. Gen 25:19-34 consists of mostly Priestly and few Yahwist material and Gen 27:1-45 on the other hand is purely Yahwist material.27 Many tensions between parents and sons are embedded within the narrative of Jacob and Esau. The narrative opens with the problem of barrenness on the part of the wife, Rebekah. The tension is however resolved with the prayer of the husband. Gen 25:21-23 indicates that the mother of the two sons knew from the beginning that the elder son would serve the younger as she inquired from Yhwh why the twins were struggling within her. The narrator gives preference to the younger brother. He presents him in the narrative as  "blameless man," - a positive description familiar within the sapiential books.

"blameless man," - a positive description familiar within the sapiential books.

Esau is the elder brother and he is presented as the one that the father loves because of his game hunting. The younger brother Jacob is seen to be the love object of the mother without any reason given in the text. In this instance, it is not the younger brother who becomes the object of love of the father. Neither is it attested in the text that Jacob, the younger brother, is the object of hatred of the father. The mother rather connives with Jacob, her object of love, to outwit the father to divert the blessings destined for the elder brother in favour of the younger brother. It must be noted that before then, Jacob had outwitted his elder brother to sell his birthright to him. Customs in the Hurrian society in the ANE throw light on these practices. Birthright could be determined by the father's discretion and not necessarily by chronological priority, and the declaration on a deathbed in favour of the youngest son was to safeguard his rights from being claimed by his older brothers.28

In the narrative however, the father intended giving the blessing to the older brother and not the younger one. The mother's desire to have the blessing for her object of love changed the order. The birthright especially in the case of the firstborn son in the biblical world was very significant. The firstborn was accorded certain privileges because of the sanctity attached to him.29 The firstborn that opened the womb was to be dedicated to God and had a special honour in the family.30 Deut 21:15-17 prohibits the transference of the birthright of the firstborn and indicates that the firstborn is entitled to a double portion of the father's inheritance. Sarna is of the view that the practice in our narrative may have reflected an earlier situation.31

The consequences of the plot hatched by the mother and the younger brother through deception evoked hatred from the elder brother to the extent that he desired to kill the younger brother. The mother's love for the younger brother brought conflict between the brothers in the family and her intention to protect her object of love eventually drove the younger son away from the family. Von Rad explains that Rebekah's decision to get rid of Jacob from the land was because of the fear that she might lose both sons.32 If Esau would kill his brother, he might also have to flee from the land because of the crime and that would imply losing both of them. The deceptive plot hatched by a mother and her beloved son eventually brought strife in the family. The son was driven away from the father, the mother and the brother.

4 Joseph and his brothers (Gen 37:2b-36 [39-50])

Another narrative in which the younger-brother motif is embedded is the Joseph-Story found in Gen 37:2b-36. This will be discussed in the context of the entire narrative of the Joseph story in Gen 37-50, due to their inter-relatedness. Gen 37:2b-36 is Yahwist material with insertions from Elohist material.33 The Joseph story comprises the entire block of narrative of Gen 3750 which concludes the book of Genesis.34 Joseph is the main protagonist of the story.

Joseph is presented as the son of Jacob among his eleven other brothers. Joseph and his younger brother Benjamin are the children of Rachel, the wife that Jacob loved most35 and they become the objects of love of their father Jacob. Though Benjamin happens to be the youngest, he does not attract more attention than Joseph in the entire Joseph story. More is said about Joseph than Benjamin. Joseph is presented as the object of love of the father because he is the son of his old age.36 To depict the father's love for him, Jacob made him a decorated tunic which attracted his elder brothers' envy. This garment indicated the father's preference for him. This tunic "was probably a special robe worn by royalty," and anticipated Joseph's rise to power.37 Eventually, this became an object of hatred, favouritism and discord.38 This act of the father brought tension and conflict in the family. This tension and conflict are heightened by the dreams of Joseph which signified his future superiority over his parents and brothers.

Joseph being the love object of the father now becomes the object of hatred of his elder brothers and they could not relate peacefully with him. Their hatred for the younger brother was as a result of the father's love for him and his dreams. The hatred for the younger son was thus the hatred for the object of love of the father. Their hatred for their younger brother and their envy of the father's love resulted in their plot to get rid of him. The passage reflects the conflict between a father and his children on one hand and a conflict between a younger brother and his elder brothers on the other. The question that goes along with the tension in the text is: was the father wrong in having a special love for the younger son Joseph, although the narrative never reported that the father hated the other brothers? Joseph eventually went to Egypt where he became the means by which the brothers, who got rid of him, were to be saved from famine.

5 Ephraim and Manasseh (Gen 48:8-20)

The last text that I would like to consider is Gen 48:7-19 on the blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh which is proposed to be a fusion of Yahwist and Elohist material.39 This involves a conflict between a father and a son as a result of the father's blessing of the younger grandchild. The customs of birthright and deathbed blessing in this passage are similar to those explained in the narratives concerning Jacob and Esau.

In this pericope, we find Jacob taking the initiative to bless the sons of Joseph at his knees: Ephraim and Manasseh. Waltke comments that this blessing was a form of an adoption ceremony.40 Joseph placed them in such a way that the father would bless the elder brother with the right hand and the younger brother with the left hand. However, Israel used the left hand to bless the elder brother and the right hand to bless the younger brother. In so doing, the grandfather changed the position of the recipients of the blessings, thus changing the order of seniority.41 This act according to the narrator was displeasing to Joseph and consequently he wanted to change the father's right hand to bless Manasseh, the elder brother. Joseph wanted to hinder the father for the simple reason that Ephraim was not the firstborn son. He ordered the father to put his right hand on Manasseh instead. Right hand signified "the position of strength, honour, power, and glory."42 By implication, the elder brother was the one deserving such a position and changing the position could be a cause of conflict.

Did the grandfather have any preference for the younger brother although both sons were blessed by him? Jacob's response to Joseph's reaction in the narrative indicates that both would prosper though the younger one would be greater. The narrative ends with Jacob blessing both of them, even though it puts Ephraim ahead of Manasseh.43 Two victims of the younger-brother motif as a source of conflict in the family in the book of Genesis are brought together in this narrative, having opposing attitudes towards the tradition of the younger brother supplanting the elder brother. Here one can recognise that Joseph who had been the object of love of his father and the envy of the elder brothers, accepted the tradition that the elder brother must be given the preference. Jacob on the other hand, who supplanted his elder brother Esau and preferred his younger son to the older ones, is presented in this narrative as being in favour of the tradition.

C THEOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE YOUNGER-BROTHER MOTIF TEXTS

The theological significance of the younger-brother motif narratives could be deduced from the analysed texts through the imageries presented of God and his relationship to the characters in the narratives. In the narratives, God intrudes at certain points to resolve the tension and the conflict. I will examine the interactions between God and the characters in the narratives and highlight their significance.

1 The Image of God in the Narratives

1a Cain and Abel

God appears as one of the characters in the Cain-Abel narrative. He appears after the offering of the brothers and after the death of Abel in the rebuke of Cain. God's acceptance of the offering of Abel and the non-acceptance of that of Cain becomes the bone of contention between the two brothers. The acceptance of Abel's offering seems to point to the love of God for the younger brother in the narrative. This act can depict God as being partial towards the younger brother. The non-acceptance of the offering of Cain, does not however, imply God's rejection of him. In other words, the acceptance of the younger brother's sacrifice did not imply the absolute rejection of the elder brother.

Although Cain's act called for punishment and was banished from the ground, in the rebuke after the death of his younger brother, he was not denied God's protection. It is clear from the narrative that Cain was assured of God's protection after he had received his judgement for his crime against his brother. Though Cain was to depart from God and deserved death, he received a  (seal/sign) from God that was meant to protect him.44 Thus, in Cain's rebuke and the judgement against him after the fratricide, one recognises God's care for him. Cain's response to the rebuke in Gen 4:13-14 in a form of a complaint is responded with God's mercy.45

(seal/sign) from God that was meant to protect him.44 Thus, in Cain's rebuke and the judgement against him after the fratricide, one recognises God's care for him. Cain's response to the rebuke in Gen 4:13-14 in a form of a complaint is responded with God's mercy.45

1b Isaac and Ishmael

God plays an active role in the narratives. He is involved in the interactions among the characters in the narratives directly and indirectly through his messenger/angel ). He endorses some of the actions of the characters. In Gen 16:2 Sarah attributes her inability to give birth to God. God intervenes through his angel to advise Hagar to return to her mistress, Sarah, when she ran away from her due to the harsh treatment she received from her. He promises and assures her that her offspring will be great.

The conflict among Abraham, Sarah and Hagar is resolved through the intervention of God in Gen 21:11-12. It is God who affirms Abram's decision to chase his son Ishmael and his mother away. Although it was very difficult for Abraham to carry out Sarah's desire to chase Ishmael and his mother away from the family, it was God who encouraged him to do so assuring him of Isaac's ability to continue his lineage.

Despite the fact that the role of God in the narratives seems to be in favour of the younger brother, both brothers receive the divine promise of becoming great nations. Although Hagar and her son Ishmael were driven away from the house through the intervention of God, they were not driven away from him. God continued to be with the son, Ishmael, as attested in Gen 21:20.

1c Jacob and Esau

God's interactions with the characters in these narratives centre on the barrenness and the conception of Rebekah, and the prayer and the blessing of Isaac of his son Jacob.

God granted the prayer of Isaac for his barren wife Rebekah and she conceived Esau and Jacob. The struggles among the unborn babies made Rebekah to inquire of Yhwh. God assures Rebekah that the elder brother will serve the younger brother, which might have influenced her role in the narrative. Isaac blessed Jacob in the name of God.

1d Joseph and his brothers

God plays both active and passive roles in the Joseph narrative. In Gen 39:2-5, Joseph's success is attributed to God. This blessing of Yhwh was to extend to the whole of Egypt. Joseph became an instrument to save Egypt and his family and this is attributed to God's providence. God intervened to encourage Jacob to move down to Egypt with his family in Gen 46:1-4.

According to Anderson, one theological message that the Joseph story seeks to bring to its audience is the providence of God,46 irrespective of the unexpected family conflicts. In the entire Joseph narrative one can identify God working at the background. Anderson considers Gen 45:5-7 to encapsulate the essential theme of the Joseph story: here Joseph himself attributes all the events to the providence of God, that is, his being sold into Egypt by his elder brothers to preserve lives.47 The narrator uses the younger-brother motif to develop a plot around the providence of God within the context of family conflicts.

1e Ephraim and Manasseh

God plays a passive role in this narrative. He does not interact with the characters as in the other narratives previously discussed. Reference is made to him only in the blessing of Manasseh and Ephraim and his manifestation to Jacob in the land of Luz.

2 Synthesis of the Theological Significance of the Narratives

From the examination of the younger brother-motif texts in Genesis, one recognises that the setting of the motif is in the context of the family. In the narratives, one can identify that the harmony that ought to exist among brothers and family members is distorted by tension, conflict and upsetting traditions. The role of God in such narratives amidst the family tensions and conflicts is worth noting.

Looking at the examined texts critically, one can recognise the love of God being exhibited more in favour of the younger brother than the elder brother, although in the ANE the firstborn, being elder, commanded more privileges.48 At face value, these narratives may imply that God is partial and unfair to the elder brother. This is however not the case. The narrator had reasons for using the motif in order to draw the attention of his audience to certain truth.

One explanation that can be given for God's favour towards the younger brother as depicted in the narratives, may be that the younger brother appears to be more vulnerable and fragile than the elder brother. In other words, the younger brother is weaker in terms of vulnerability in relation to the elder brother. In the Cain-Abel narrative, the reader identifies the elder brother who commits a crime against the younger brother. The narrator of the Esau-Jacob story presents the elder brother Esau as the one who stands a chance of harming the younger brother. Jacob, the father, is unwilling to allow his sons to take Benjamin along to Egypt because of the fear that harm might befall him even though he would be in the midst of his older brothers.49 In these narratives, one can identify the image of the weaker brother in the nation Israel. God's involvement in the personal lives of the patriarchs in the younger brother motif reflects his encounter with Israel.50 Thus, Israel, weak among the powerful nations, is likened to the younger brother who is raised and becomes the firstborn of God.51 The love of God for the younger brother reflects God's love for Israel.

Another important theological element that we can deduce from the use of the younger-brother motif is that the narrators raise the image of the weaker siblings to depict God's mercy for the weaker ones in human society. Among the ancient Israelites, there were the rich and the poor, the kings and subjects, the mighty and the weak. In some cases, the rights of the weaker ones were trampled upon by the mighty ones. The rich, kings and the mighty were seen in some contexts as oppressors while the poor, subjects and the weak were depicted as the oppressed. Injustice was committed against the marginalised. Examples are seen in the incidents between David and Uriah, Ahab and Naboth, and the rich and the poor in the book of Amos. God, seen as delivering the weak, is echoed by the psalmist: " Yhwh, who is like you, delivering the afflicted from the mighty, the poor from his exploiter,"52 which also reflects his love for the vulnerable. Thus, through the younger-brother motif the narrators raise the image of the weak ones in the society. The family being the basic component of the society becomes the focus of the narrators to open the eyes of the society to ways in which the weaker ones could also be protected.

Though the narrators present the role of God in favour of the younger brother, it does not imply absolute rejection of the elder brother, as it can be seen in all the texts examined. Both the younger brothers and senior brothers receive blessings and protection from God.53

The conflict and tension in the narratives have their theological reference to the fall of man in the primeval history. As indicated earlier on, the disobedient act of the first parents, Adam and Eve that brought conflict in their relationship with the creator and creation extends to their offspring.54 The corruption of fundamental human relationships, which militates against the harmony intended in creation, stems from the consequences of the fall of humankind.55 Waltke for instance indicates that the Cain-Abel narrative "displays humanity's worsening situation outside the Garden."56 In this regard, the narrators employed the younger-brother motif in texts to demonstrate how the consequence of the disobedience of the first parents continued to bring strife, murder, envy, rivalry, deception, hatred et cetera among human relationships.57

D THE YOUNGER-BROTHER MOTIF: REFLECTION FOR THE CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN58 FAMILY

The relationship of love or hatred among parents, sons, brothers and family members could evoke tension and conflict, which when not resolved, could bring further conflict in the family. The above-examined texts, revolving around the younger-brother motif, depict conflict within the family to the real audience of the texts. This conflict, which is theologically traceable to the fall of humankind, is also found in all human societies in various forms. One can deduce different types of conflict in the relationships among family members from the younger brother-motif texts analysed. These are:

(i) A conflict between a brother and a brother as portrayed by the Cain-Abel narrative.

(ii) A conflict between wives of the same husband centring on the children as demonstrated in the Isaac-Ishmael narratives.

(iii) A conflict between a brother and a brother with the parents being the source of the fraternal strife as seen in the Jacob-Esau narrative.

(iv) A conflict between a brother and his elder brothers because of the special love of the father for a younger brother as found in the Joseph story.

(v) A conflict between a father and a son as a result of the father's preference for the younger grandson as seen in the case of the blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh.

Apart from these main types of conflict exhibited in the narratives, one can identify other family-related problems. Some of these family-related problems are; conflict among siblings leading to fratricide, desire to murder, barrenness, jealousy, deception, rivalry among wives, inheritance and the partial love of parents. These problems do confront humanity in general and the African families of today in particular. Conflict within family relationships are some of the most difficult and challenging problems confronting the world today.59 Though the problems are global, their intensity and forms may differ from one culture to the other. Marriage is the basic foundation of a family.60Customs and traditions concerning marriage are different from one society to another, though the essence and purpose of marriage may be similar.

One type of conflict exhibited in the narratives examined, is rivalry among wives of the same man. Most polygamous societies accept or prefer polygyny to polyandry. There is no clear evidence of polyandry in the OT. Evidence of polygyny however abounds in the OT and the marriage of Abraham with Sarah and Hagar is a clear example. Just as the polygynous marriage of Abraham was characterised by family conflict, polygynous marriage in general comes along with its attendant problems and conflicts. A man could have more than one wife depending on the customs and traditions concerning marriage in that society. The father of a polygynous family has the tendency of treating some of the wives or children partially as seen in the Isaac-Ishmael, Jacob-Esau and Joseph narratives. Sarpong justifies the polygamous marriages in Africa on sexual and economic grounds.61 Nukunya, touching on the effects of social change on marriage in Ghana, echoes that "the conflicts and quarrels generated by polygyny among co-wives and among their children have also become more menacing in the modern conditions of more awareness of individual's rights."62Nukunya highlights on some of the family conflicts as a result of polygynous marriage but admits that polygyny has not been abandoned outright even with the acceptance of monogamy.63

The impact of Judaeo-Christian practices on some African societies is making monogamous marriage more acceptable in some countries.64 This is not to be presumed that monogamous marriage is immune from family conflicts and problems.65 Among other African traditional societies, though there has been a Christian influence, polygamous marriage is still practised.66

Barrenness and fraternal conflict are evident in the younger-brother motif texts. One major purpose of marriage among Africans is the bearing of children.67 The African father must claim paternity of all children born to him.68The importance placed on children makes barrenness, sterility and impotence a cause of worry in the family. Sarpong is of the view that barrenness "is the greatest calamity that can befall a Ghanaian woman."69 The desire to have more children to help parents work on the farm among the Akan of Ghana necessitate polygynous marriage in some cases. Children serve as security for the parents in their old age since the children and close relatives care for the aged in the family. Children carry on the name of the family and in a marriage where the wife cannot bear children, the husband and wife can make arrangements for another wife.70

Form of kinship and the system of inheritance differ from one traditional society to another. Among the traditional societies of Africa, some inherit patrilineally and others matrilineally. With patrilineal inheritance, the family property is passed on to the children of the father, whereas in matrilineal inheritance, the inheritance passes on from the father to his maternal family relations. Both of these systems have their shortcomings. Though there are few instances of daughters inheriting the property of the father,71 the OT gives a clear indication of a patrilineal system of inheritance in which the son is given preference with regards to inheritance.72 Family property is passed on from father to son as envisaged in the texts examined. Conflicts and struggles over family properties to the extent of getting into litigations abound in the contemporary African societies. The concerns of the family are the concerns of the nation as well since "the decline and the fall of the nation begins in its homes."73 With modernisation, legal documents have been produced on family inheritance to forestall its associated problems. For instance, the Ghanaian Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) Intestate Succession law III in 1985 was meant to resolve some of these problems.74 Christian and ordinance marriages are supposed to provide security for the wife and children in terms of inheritance.75 Their effectiveness is however relative.

To resolve conflict among siblings, as seen in the younger-brother motif texts, character formation of the African family members is of prime importance. One important purpose of the family is character formation of the children. It is the duty of the family and the society at large to help raise the children in a good and acceptable societal behaviour. The marriage and for that matter the family is to inculcate into the family members good behaviour and manners. For instance, the home of the Akan becomes the training ground for the children and as such the character that they build in their childhood determines their future behaviour.76

Mbiti points out some of the aspects of a good family as "love, good character, hard work, beauty, companionship, caring for one another, parental responsibility towards children and the children's responsibility towards the parents."77 Some of the conflicts in the younger brother-motif texts go contrary to these moral values in the African family as outlined by Mbiti. Through good moral training of the child, one can acquire the aforementioned traits that could serve as antidote to the problems in family relationships. Gyekye shares the view that a strong family system that serves as an important moral support helps to minimise the rate of moral offenses and criminal acts among the youth.78 The tribes of Africa have various means of transmitting their culture and morals to their younger generations through proverbs, folktales, stories, celebration of festivals and motivation of good acts and so forth.79 These means through which the traditional African families have in transmitting good moral behaviour to the youth are not unfamiliar with the biblical world. Literary genres, motifs and lessons found in the sapiential books have a similar purpose in inculcating good morals to the youth and the family members.

Though the human problems raised in the younger-brother motif texts vis ä vis those of the African culture may not be eradicated entirely, the willingness to enhance the moral values enshrined in the traditional African family set-up to form the good conscience of the individual could help a great deal in resolving these problems of the family. Though conflict is unavoidable, its toll on the contemporary African family and the society at large can be minimised if each family member has a well-formed conscience and sound morals to maintain the harmony of the family.

E CONCLUSION

The younger-brother motif texts in Genesis are characterised by tension and conflict within the family setting. These are demonstrated in the relationships which exist among family members. The main types of conflict that one can identify in the narratives are found within brother-brother, parent-child, wife-rival and grandfather-grandson relationships. The motif has a symbolic-theological significance in the sense that it refers to the love of God for Israel and the weak ones in society. If the examined narratives are taken at the face value, the problems raised are also prevalent in the African family set-up. These typical conflicts militate against the harmony of the family, though, laws and regulations are made by contemporary African societies to eradicate conflict in the family. Going back to the traditional moral values for the training of the African child to build the conscience could help face up to the challenge.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackah, Christian A. Akan Ethics: A Study of the Moral Ideas and the Moral Behaviour of the Akan Tribes of Ghana. Accra: Ghana Universities Press, 1988. [ Links ]

Anderson, Bernhard W. The Living World of the Old Testament. Harlow: Longman, 1988. [ Links ]

Bassler, Jouette M. "Cain and Abel in the Palestinian Targums: A Brief Note on an Old Controversy." Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Periods 17/1 (1986): 56-64. [ Links ]

Bean, Adam L. "Inheritance." Dictionary of Daily Life in Biblical and Post-Biblical Antiquity: Vol. III, 33-41. [ Links ]

Bediako, Daniel K. "Bible and Culture: Revisiting the Question of Polygamy." JABS 3 (2011): 18-35. [ Links ]

Castellino, Giorgio R. "Genesis IV 7." Vetus Testamentum 10 (1960): 442-445. [ Links ]

Coogan, Michael D. The Old Testament: A Historical and Literary Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Ellis, Peter F. The Men and the Message of the Old Testament. Collegeville Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1975. [ Links ]

Gordon, Cyrus H. and Gary A. Rendsburg. The Bible and the Ancient Near East. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997. [ Links ]

Gyekye, Kwame. African Cultural Values: An Introduction. Accra: Sankofa Publishing Company, 1996. [ Links ]

Heller, Roy L. Narrative Structure and Discourse Constellations: An Analysis of Clause Function in Biblical Hebrew Prose. HSS 55. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2004. [ Links ]

Koehler, Ludwig, and Walter Baumgartner. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994. [ Links ]

Magesa, Lauranti. African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 1997. [ Links ]

Matthews, Victor H. Manners and Customs in the Bible. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1988. [ Links ]

Mbiti, John S. Introduction to African Religion. 2nd ed. Johannesburg: Heinemann Publishers (Pty) Limited, 1991. [ Links ]

Moon, W. Jay. African Proverbs Reveal Christianity in Culture: A Narrative Portrayal of Builsa Proverbs Contextualizing Christianity in Ghana. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2009. [ Links ]

Nukunya, Godwin K. Tradition and Change in Ghana: An Introduction to Sociology. Accra: Ghana Universities Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) Decree Law III, Intestate Succession Law 1985. [ Links ]

Rendsburg, Gary A. The Redaction of Genesis. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1986. [ Links ]

Richardson, Alan. Genesis I-XI: Introduction and Commentary. TBC. London: SCM Press Ltd., 1953. [ Links ]

Ryken, Leland, James C. Wilhoit, and Tremper Longman III. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity, 1998. [ Links ]

Sarna, Nahum M. Understanding Genesis: The World of the Bible in the Light of History. New York: Shocken Books, 1966. [ Links ]

Sarpong, Peter. Ghana in Retrospect: Some Aspects of Ghanaian Culture. Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation, 1974. [ Links ]

Speiser, Ephraim A. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes. AB 1. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964. [ Links ]

Von Rad, Gerhard. Genesis: A Commentary. OTL. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972. [ Links ]

Waltke, Bruce K. Genesis: A Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001. [ Links ]

______. An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical, and Thematic Approach. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Genesis 1-11: A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994. [ Links ]

Wright, Christopher J. H. Old Testament Ethics for the People of God. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2004. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 7/10/2016

Peer-reviewed: 15/11/2016

Accepted: 26/01/2017

Rev. Dr. Emmanuel Kojo Ennin Antwi, Lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. Email: kojoantwi999@yahoo.de

1 This paper is a revised version of a paper presented at the meeting of the Ghana Association of Biblical Exegetes, Accra, Ghana, 11-15 January, 2016.

2 This motif is similar to the younger-son motif which is found in the Ugaritic texts. Cf. Cyrus H. Gordon and Gary A. Rendsburg, The Bible and the Ancient Near East (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997), 129-130.

3 The tensions and the family conflicts in the narratives are also manifested in the contemporary African family.

4 Cf. Gordon and Rendsburg, The Bible and the Ancient Near East, 130.

5 Cf. Peter F. Ellis, The Men and the Message of the Old Testament (Collegeville Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1975), 58.

6 Cf. Giorgio R. Castellino, "Genesis IV 7," VT 10 (1960): 442, "The Cain-Abel episode is commonly acknowledged as one of the difficult passages of the OT. Although clear in its general purport, the narrative shows not a few elements that have so baffled the commentators."

7 אֶת־אָחִ֖יואֶת־הִָ֑בֶל , הֶֹּ֣בֶלאָחִ֑יךָI(4:2, 8-11).

8 Cf. Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11: A Continental Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994), 294-297.

9 Bernhard W. Anderson, The Living World of the Old Testament (Harlow: Longman, 1988), 163. Cf. Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001), 97. Cf. Ephraim A. Speiser, Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, AB 1 (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964), 31.

10 There are disagreements on this interpretation by scholars. Cf. Westermann, Genesis 1-11, 296-297. "The distinction between a better and worse attitude on the part of the one offering is a modern intrusion." Examining the MT critically, some of these points raised in answer to the tensions and conflicts in the narrative have no basis. How do we reconcile God's putting Adam in the garden to till the ground in Gen 2:15 with the comments raised against Cain as a worker of the ground.

11 Jouette M. Bassler, "Cain and Abel in the Palestinian Targums: A Brief Note on an Old Controversy," JSJ 17 (1986): 56.

12 Alan Richardson, Genesis I-XI: Introduction and Commentary, TBC (London: SCM Press Ltd., 1953), 80.

13 Cf. Waltke, Genesis, 102.

14 Speiser, Genesis, 116-117. According to the division of Speiser, Gen 16:1a, 3, 15 is a priestly material and Gen 16:1b-2, 4-14 is Yahwist. Cf. Ellis, Men and the Message, 60.

15 Speiser, Genesis, p. 152. According to the division of Speiser, Gen 21:1-2a is Yahwist, Gen 21:2b-5 is priestly and Gen 21:6-21 is Elohist.

16 Cf. Gerhard von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary, OTL (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), 191-192.

17 Cf. Waltke, Genesis, 252.

18 Waltke, Genesis, 252. Cf. Nahum M. Sarna, Understanding Genesis: The World of the Bible in the Light of History (New York: Shocken Books, 1966), 128.

19 Cf. Victor H. Matthews, Manners and Customs in the Bible (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1988), 38-39.

20 Cf. Von Rad, Genesis, 232.

21 Cf. Koehler, Ludwig, and Walter Baumgartner. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994, 800-801.

22 Cf. Waltke, Genesis, 294.

23 Speiser, Genesis, 155.

24 Von Rad, Genesis, 232.

25 Gen 21:10.

26 Sarna, Understanding, 156-157.

27 Speiser, Genesis, 193-194, 205-207. According to the division of Speiser, Gen 25:19-34 consists of 19-20 and 26a as Priestly and 21-26b, and 27-34 as Yahwist.

28 Cf. Speiser, Genesis, 212-213.

29 Sarna, Understanding, 184-185.

30 Waltke, Genesis, 363. Cf. Exod 13:2; Deut 15:19.

31 Sarna, Understanding, 184-185.

32 Von Rad, Genesis, 279.

33 Speiser, Genesis, 287-289. According to the division of Speiser, Gen 37:2b-18, 25-27, 28b, are Yahwist and Gen 37:21-24, 28a, 28c-36 are Elohist.

34 Some scholars exclude Gen 38 with the reason that the story of Judah and Tamar was a redactional insertion. Cf. Gary A. Rendsburg, The Redaction of Genesis (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns 1986), 80. Gordon and Rendsburg, Bible, 132; Von Rad, Genesis, 347-348; Roy L. Heller, Narrative Structure and Discourse Constellations: An Analysis of Clause Function in Biblical Hebrew Prose, HSS 55 (Winona Lake:

Eisenbrauns, 2004), 39-40.

35 Gen 29.

36 Gen 37:3.

37 Michael D. Coogan, The Old Testament: A Historical and Literary Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 75.

38 Sarna, Understanding, 212.

39 Speiser, Genesis, 259.

40 Waltke, Genesis, 597-598. Cf. Von Rad, Genesis, 415.

41 Speiser, Genesis, 360.

42 Waltke, Genesis, 598.

43 This narrative has an aetiological significance and it reflects, anticipates and explains the tribe of Ephraim's dominance over the tribe of Manasseh in the Northern Kingdom cf. Von Rad, Genesis, 416.

44 Bruce K. Waltke, An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical, and Thematic Approach (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 271; Christopher J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2004), 216; Von Rad, Genesis, 107-108.

45 Cf. Waltke, Old Testament Theology, 271.

46 Anderson, Living World, 177. Cf. Gordon and Rendsburg, Bible, 131.

47 Anderson, Living World, 177.

48 Cf. Von Rad, Genesis, 416.

49 Gen 42:36-38.

50 Gordon and Rendsburg, Bible, 130.

51 Cf. Gordon and Rendsburg, Bible, 130.

52 Ps 35:10.

53 Cf. Gordon and Rendsburg, Bible, 129-130. The narrator of the patriarchal narratives used the younger-brother motif which already existed in Ugaritic literature to communicate some theological truth to their audience

54 Cf. Leland Ryken, James C. Wilhoit, and Tremper Longman III, Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity, 1998), 125.

55 Wright, Old Testament Ethics, 215-216.

56 Waltke, Old Testament Theology, 268-269.

57 Ryken, Wilhoit, and Longman III, Dictionary, 125.

58 I acknowledge the diversity of the African culture from one ethnic group to another. I will in this case use my Ghanaian cultural background as an example though it may not precisely represent all the African cultures.

59 Cf. Ryken, Wilhoit, and Longman III, Dictionary, 125.

60 Cf. Kwame Gyekye, African Cultural Values: An Introduction (Accra: Sankofa Publishing Company, 1996), 76-77.

61 Peter Sarpong, Ghana in Retrospect: Some Aspects of Ghanaian Culture (Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation, 1974), 78; Cf. Laurenti Magesa, African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life (Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 1997), 128.

62 Godwin K. Nukunya, Tradition and Change in Ghana: An Introduction to Sociology (Accra: Ghana Universities Press, 2003), 159.

63 Nukunya, Tradition, 159.

64 Cf. Nukunya, Tradition, 156.

65 Cf. Daniel K. Bediako, "Bible and Culture: Revisiting the Question of Polygamy," JABS 3 (2011): 22.

66 Cf. Nukunya, Tradition, 156.

67 John S. Mbiti, Introduction to African Religion, 2nd ed. (Johannesburg: Heinemann Publishers, 1991), 110, 112; Gyekye, African Cultural Values, 83-84.

68 Cf. Magesa, African Religion, 112.

69 Sarpong, Ghana, 69.

70 Mbiti, Introduction, 114.

71 Cf. Num 27:1-11.

72 Cf. Adam L. Bean, "Inheritance," DDL III, 33-35.

73 Gyekye, African Cultural Values, 67.

74 Provisional National Defence Council Law III, Intestate Succession Law, 1985.

75 Nukunya, Tradition, 156.

76 Christian A. Ackah, Akan Ethics: A Study of the Moral Ideas and the Moral Behaviour of the Akan Tribes of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Universities Press, 1988), 79.

77 Mbiti, Introduction, 112.

78 Gyekye, African Cultural Values, 91.

79 Gyekye, African Cultural Values, 66; Cf. W. Jay Moon, African Proverbs Reveal Christianity in Culture: A Narrative Portrayal of Builsa Proverbs Contextualizing Christianity in Ghana (Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2009), 31-32.