Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.29 n.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2016/v29n1a10

ARTICLES

Psalm 73 and the book of Qoheleth

Izak (Sakkie) J. J.; SpangenbergII

ISakkie

IIUNISA

ABSTRACT

The author of Ps 73 and the author of Qoheleth both underwent experiences that did not accord with the traditional wisdom paradigm. The author of Qoheleth stated that he saw how the righteous suffered an early death while the wicked grew old (Qoh 7:15). The author of Ps 73 saw how impious folks experienced health, wealth and prosperity, while he "kept his heart pure and his hands clean" (Ps 73:13). Both authors tried to come to terms with these contradictions in life. One wrote a whole book, the other a poem, and both of them made use of quotations to argue their case. However, while the author of Qoheleth undermined the traditional wisdom paradigm, the author of Ps 73 tried to keep it intact. The author of Qoheleth concluded that nothing made sense; everything was futile, especially if the doctrine of retribution is used as a benchmark. The author of Ps 73, on the other hand, followed another route. He redefined the outcomes of shalom. In doing this, he successfully kept the traditional wisdom paradigm intact.

Keywords: aphorism, wisdom saying, wisdom paradigm, doubt, impious folks, pious Israelite, Psalm of Asaph, Qoheleth, doctrine of retribution

"Doubt frees us from illusions of having captured God in a creed. 1

A INTRODUCTION

In 2009,1 completed my third decade as an OTscholar.2 This occasioned some reflection on how my theological convictions had changed over the years. I could not but conclude, with Norbert Greinacher: "My theology of unquestioning certainty has increasingly become a theology of doubt.3 Greinacher and I are not alone in this experience. Over the years, I have encountered a number of theologians, biblical scholars, theological students and ordinary church members who were vexed by traditional Christian doctrines and who had been forced to question their theological convictions. I also came across a number of books whose authors reflected on the issue of the doubt accompanying such questions. Two of them deserve to be mentioned here: (1) The Courage to Doubt: Exploring an Old Testament Theme, and (2) I believe, I doubt: Notes on Christian Experience.4

Robert Davidson, a retired professor of OTat the University of Glasgow, argued convincingly that doubt is an important theme in the OTI read the book during the 1980s while doing research for my thesis on the book of Ecclesias-tes,5 and embraced these words:

There is no use trying to make Qoheleth fit neatly into the central stream of Israel's religious traditions. At many points he goes far beyond any other thinker in the Old Testament. He rejects much that lies close to the beating heart of Israel's faith. But he does so with an honesty and integrity which are refreshing. He takes a long hard look at the faith in which he has been nurtured, and at point after point he has the courage to say, "I can no longer believe that; it doesn't make sense to me."6

The book also contains Davidson's discussion on three wisdom psalms that express doubt, Pss 37, 49 and 73.1 shall return to some of his comments on Ps 73 later.

The second book, I believe, I doubt, was originally published in Germany under the title Ich glaube, ich zweifele: Notizen im nachhinein.7 Weber was a former director of the Catechetical Institute of Aachen and spent the greater part of his life in religious education. After his retirement, he wrote this book, in which he did not shy away from expressing serious doubts about traditional Christian doctrines. When I read it, I experienced the "gasp of relief described by John Robinson in his book The new reformation?: "There is a gasp of relief at being able to express one's questionings and doubts and find them shared."8 Weber's book helped me come to terms with both my own doubts and my discovery of what lies at their root. He wrote:

Like faith, doubts too have a right to be taken seriously. They too have a right to be faced, expressed and identified, questioned and thought through, so that faith is truthful. For these doubts have grown out of the same ground in which I once recognized Christian faith: the quest for truth.9

Theologians and biblical scholars in present-day South Africa are often frowned on when they dare to express their doubts about traditional Christian doctrines and convictions. Ordinary Bible readers and church members apparently do not realise that doubt is an important theme in the Bible and that it is "an indispensable element in the discovery of truth and the formation of knowledge."10 We cannot do without it in the scholarly world. However, it is not always easy to face one's doubts squarely, and it often leads to intellectual agonies that become particularly severe when an established paradigm is destabilised by new data that cannot be accommodated by the old paradigm. When Thomas Kuhn discusses this issue, he refers to Albert Einstein's comments when he encountered problems that the old scientific paradigm could not handle: "It was as if the ground had been pulled out from under one, with no firm foundation to be seen anywhere, upon which one could have built."11

Old Testament studies went through a paradigm shift somewhere between 1880 and 1900, and a new paradigm for research practice emerged soon afterwards. Mark Noll summarises the new paradigm as follows: "(the Bible, however sublime, is a human book to be investigated with the standard assumptions that one brings to the discussion of all products of human culture)."12 Many South African theologians, biblical scholars, ministers and church members are still struggling to come to terms with this change.13 They are convinced that the Bible should not be read and treated as a human book - it is quite simply the Word of God.

B PSALM 73 AND THE WISDOM PARADIGM

The author of Ps 73 was evidently confronted with discrepancies that he could not integrate into the wisdom paradigm in which he had been raised and educated. It shook the very foundations of his belief system. The wisdom paradigm presumed a fixed order in nature and human society, an order that had been established by God. Those who lived in harmony with this order experienced "health, wealth and prosperity," while those who lived a disruptive and disorderly life experienced the contrary, or rather should experience the contrary. The doctrine of retribution plays an important role in the wisdom literature and the psalms. However, what the psalmist observed made him doubt not only his convictions but also the One who was regarded as the guardian of the order, the One who was supposed to punish evildoers and bless those who lived an upright life. God was not good to the pure in heart. "This was the conclusion that pressed itself on the suffering author with compelling force."14

Although the previous statements are an accurate assessment of the author's agonies, a detailed examination of the structure and the content of the psalm will reveal how well-structured his thoughts are, and how he eventually revises the wisdom paradigm. James Crenshaw further correctly observes that "In the psalm the spotlight shifts back and forth from the anguished believer to the irreligious throng . . .,"15 but his analysis of the structure is not entirely accurate. He maintains that the psalm has seven sections (vv. 1-3; 4-12; 13-16; 17; 18-20; 21-26; 27-28), and that v. 17 is the pivot of the psalm.16 Other scholars hold similar views. However, none of them has paid proper attention to the structural markers in the text or seen how the "spotlight shifts back and forth" from the pious Israelite to the impious folks. I hope to do that and at the same time do justice to the arguments of an Israelite who was pure of heart.

According to my reading, the psalm can be divided into two halves (vv. 2-14; 15-28), with the introductory verse, "God is good for the pious; God is good to those who are pure in heart" (v. 1), standing independently as a wisdom aphorism or adage. It is a short, pithy saying communicating the gist of what the traditional wisdom teachers believed and taught: the upright and pious will be blessed.17 The whole psalm engages this aphorism. In a sense, the author's strategy is similar to that of the author of the book of Qoheleth. The latter quotes wisdom sayings and then engages them in order to subvert them.18 However, there is a slight difference, in that the author of Ps 73 engages the wisdom saying in order to revisit and adjust the wisdom paradigm. His doubts are eventually alleviated by this adjustment and the convictions communicated by the traditional wisdom teachers are restored. The concluding couplet (vv. 27-28) returns to the wisdom saying at the beginning of the psalms, stating that: "But as for me, God's nearness is good to me" (v. 28a). The Hebrew word  ("good") of the wisdom saying

("good") of the wisdom saying  ("Truly, God is good to the pious," v. la) is repeated in the last line of the psalm

("Truly, God is good to the pious," v. la) is repeated in the last line of the psalm  ("But as for me, God's nearness is good to me," v. 28a) and in this way an in-clusio is created.19 The end returns to the beginning, and affirms the teaching of the wisdom saying.

("But as for me, God's nearness is good to me," v. 28a) and in this way an in-clusio is created.19 The end returns to the beginning, and affirms the teaching of the wisdom saying.

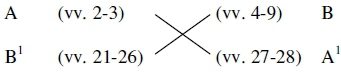

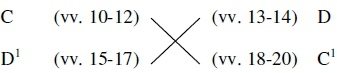

The second half of the psalm (vv. 15-28) is a "mirror image" of the first (vv. 2-14). It is comprised of four sections (vv. 15-17; 18-20; 21-26; 27-28), similar to the structure of the first half (vv. 2-3; 4-9; 10-12; 13-14) although the order is reversed. Willem Prinsloo also thought the psalm's structure was in the form of a "mirror image." However, according to his analysis, the psalm has four sections (vv. 1-3; 4-12; 13-16; 17-28). The three themes of the introductory verses (vv. 1-3) are elaborated and commented on in the three sections following the introduction (vv. 4-12; 13-16; 17-28). This creates the "mirror image" of ABC//cba.20 Prinsloo ignored a number of important structural markers. The "mirror image" in my analysis can be presented as ABCD//D1C1A1, which will be argued below.

I will first translate the Hebrew text and present my view of the structure. Following that, I shall motivate my translation and analysis, and comment on how the author approaches the wisdom aphorism of v. 1. This will be followed by an analysis of Qohelet 7:15-22 before a conclusion will be presented in which the thoughts of the author of Ps 73 are contrasted with the thoughts of the author of Qoheleth.

C TEXT, TRANSLATION AND STRUCTURE

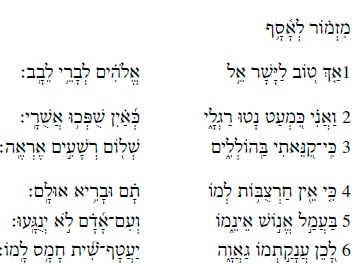

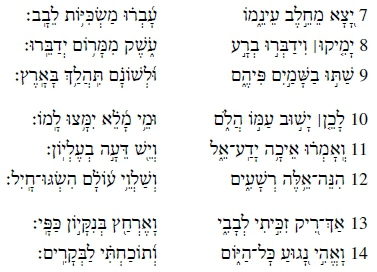

1 Text

2 Translation

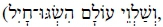

Psalm of Asaph

1. Truly, God is good to the pious;

God is good to those who are pure in heart.

2. But as for me, my feet almost stumbled; finding no foothold my steps slipped.

3. Because I was jealous of the boasters;

I saw the prosperity of the impious folks.

4. For they have no worries

their bodies are perfect and well nourished.

5. They are not acquainted with the hardships of ordinary humans; they are not affected by human struggles.

6. Therefore pride serves as their necklace; violence, the robe they wear.

7. Being well nourished their eyes protrude; they bathe in the imaginations of their hearts.

8. They speak evil from below; they talk oppression from on high.

9. They direct their mouths to heaven; their tongues walk the earth.

10. Therefore their followers return hither for they have abundant waters.

11. They say: "How could God know?"

"Is there knowledge with the Most High?"

12. Look here, this is how the impious folks are - unperturbed till the end they increase their wealth.

13. Entirely in vain I kept my heart clean, withheld my hands from evil;

14. remained vigilant the whole day, admonished myself morning after morning.

15. If I said; "I want to talk like this!"

I would have been unfaithful to the circle of your children.

16. I reflected and tried to understand but it was burdensome in my eyes -

17. until I went into God's sanctuary

[and] understood what will happen to the impious.

18. Indeed, you put them on slippery ground; you let them fall down in ruins.

19. How suddenly they are destroyed; they die, they decay - a total waste!

20. Like a dream when the Lord awakes; when you arise, you despise their image.

21. For when my heart was sore and my kidneys pained,

22. I was stupid and did not understand;

I was like an animal with you.

23. However, I was constantly near you; you grasped my right hand.

24. You lead me by your counsel

and afterwards will receive me with honour.

25. Whom do I have in heaven [but you]? and I desire nothing else on earth.

26. Even though my flesh and heart may decay;

God is the rock of my heart, my portion - till the end.

27. For those who are far from you shall perish; you silence all those who are unfaithful to you.

28. But as for me, God's nearness is good to me; I have made YHWHmy refuge -

to proclaim all your works.

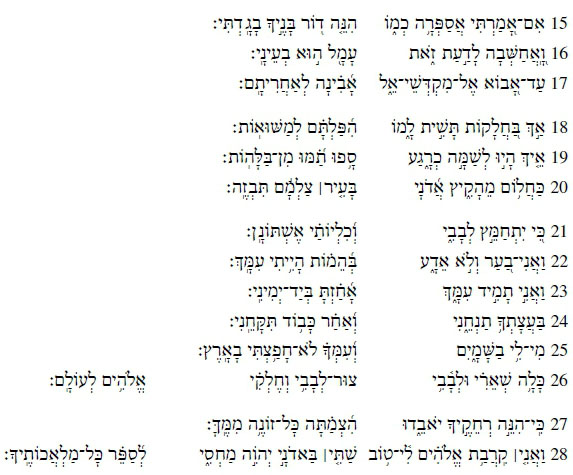

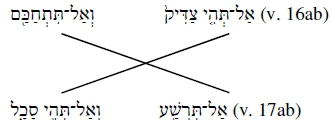

3 Structure

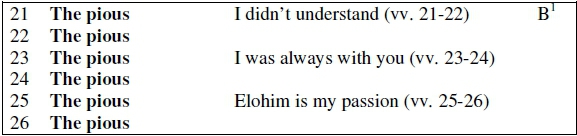

The psalm opens with a wisdom saying (v. 1). This is followed by eight strophes (vv. 2-3; 4-9; 10-12; 13-14; 15-17; 18-20; 21-26; 27-28), most of which are couplets (vv. 2-3; 13-14; 27-28) or have couplets as building blocks (vv. 49; 21-26). There are, however, three three-line strophes (vv. 10-12; 15-17; 1820), which breaks the monotony of the couplets. The eight strophes are structured in such a way that the last four are a "mirror image" of the first four, and the psalm thus has two stanzas. The analysis reveals that the author wrote a well-structured psalm and that chiasmi play an important role in the structure. It can be depicted as follows:

1 The aphorism: "El is good to the pious;

Elohim to those who are pure in heart"

2 The pious A

3 The impious

10 The impiousC

11 The impious

12 The impious

13 The pious D

14 The pious

15 The pious D1

16 The pious

17 The pious

18 The impiousC1

19 The impious

20 The impious

27 The impious

28 The pious A1

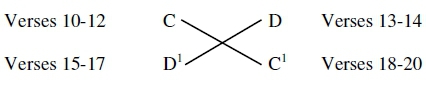

I have already pointed out that, according to my analysis, the psalm has an ABCD/ZD^bW structure. There are thus two clearly-defined chiasmi in the wider structure of the psalm, which can be set out as follows:

The first chiasmus (the outer strophes):

The second chiasmus (the inner strophes):

When one pays attention to the wording of each of the strophes more chiasmi can be identified. These will be identified and commented on when the separate sections of the psalm are discussed.

D ARGUMENTS, MOTIVATIONS AND COMMENTS

1 The Wisdom Saying (v. 1)

1.1 Translation and Structure

The Hebrew text of Ps 73 is ambiguous at certain points and is rather difficult to translate. A number of verses test translators' knowledge of Hebrew and their ability to decide what the text originally meant to say.

Although v. 1 is not difficult to translate, it does require some attention. It has been proposed that the Hebrew text should be changed slightly to create two well-balanced cola. It is suggested that  ("God is good to Israel") in the first colon of the MTshould be changed to read

("God is good to Israel") in the first colon of the MTshould be changed to read  ("God is good to the pious") and the word

("God is good to the pious") and the word  should be moved to form part of the second colon.21 The verse would then become a proper wisdom aphorism:

should be moved to form part of the second colon.21 The verse would then become a proper wisdom aphorism:  "Truly, God is good to the pious; God is good to those who are pure in heart." Some scholars link this verse directly to vv. 2-3 because of the waw with which v. 2 commences. The waw communicates contrast and, in a way, comments on the aphorism. But then it should be remembered that it is not just vv. 2-3 that engage the aphorism, but the whole psalm.

"Truly, God is good to the pious; God is good to those who are pure in heart." Some scholars link this verse directly to vv. 2-3 because of the waw with which v. 2 commences. The waw communicates contrast and, in a way, comments on the aphorism. But then it should be remembered that it is not just vv. 2-3 that engage the aphorism, but the whole psalm.

1.2 Comments

In drawing readers' attention to how poets close their texts, Jan Fokkelman makes the following important observation: "The beginning and end of a text indeed require a delicate touch."22 Although he does not indicate the relationship between the opening and closing verses (vv. 1-3; 27-28) in his analysis of Ps 73, he seems well aware of the close relationship between them.23 However, an important point escapes his attention: v. 1 should not be directly linked to vv. 2-3, because it is an independent aphorism. Patrick Miller has similarly views:

Ps. 73:1 begins the second half of the Psalter with a brief reiteration of the torah piety of Psalm 1. That is, v. 1 provides a promise and beginning point for the psalm, which in its totality moves away from torah piety (vv. 2-16) and then returns to it (vv. 18-28).24

James Ross on the other hand is of the opinion that v. 1 stands on its own and is "an 'anticipated conclusion' of the work as a whole, and at the same time an assertion that, in spite of appearances (which are then to be detailed), God is good to those who are 'pure in heart.'"25

2 The Opening and Closing Couplets (vv. 2-3; 27-28)

2.1 Translation and Structure

The first couplet (vv. 2-3) makes it evident that the author regards himself as a pious Israelite who expects to experience God's blessings as depicted in the wisdom saying. He has become envious of impious folks when he sees their health, wealth and prosperity. Contrary to what the wisdom teachers teach, they are experiencing shalom. The relationship between the two lines of the couplet can be indicated as A+B.

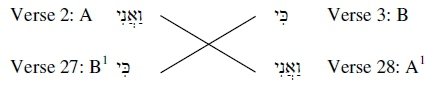

Turning immediately to the final couplet of the psalm (vv. 27-28), seeing that the opening and closing sections of a psalm often stand in close relationship to each other, the following must be considered: (1) vv. 27-28 stand in direct contradiction to vv. 2-3. The opening couplet depicts the impious folks experiencing shalom, while the pious Israelite suffers. In the closing couplet the pious Israelite experiences shalom while the impious folks experience suffering. However, shalom and suffering are now redefined. Shalom is now no longer equated with health, wealth and prosperity but with "being near to God." Suffering is also redefined. It now means not intellectual but physical pains. It has to do with destruction and death. (2) Verses 27-28 are structurally the "mirror image" of vv. 2-3. Verses 2 and 28 commence with the first person singular pronoun  while vv. 3 and 27 commence with the particle

while vv. 3 and 27 commence with the particle  The closing couplet places the first person singular pronoun and the particle in the reverse order. Thus the structure of the closing couplet is B+A, not A+B, as in the opening couplet.

The closing couplet places the first person singular pronoun and the particle in the reverse order. Thus the structure of the closing couplet is B+A, not A+B, as in the opening couplet.

The content of the two lines of both couplets supports their reverse order, the first line of the closing couplet referring to the impious folks (B) and the second line to the pious Israelite (A), in exactly the reverse order of that in the opening couplet: pious Israelite (A) and impious folks (B). We thus have a proper chiasmus, the third in the psalm.

2.2 Comments

In the opening and closing verses of the psalm, the author gives readers the first key to unlocking the meaning of the psalm. If the opening and closing verses reflect an AB//B1 A1 pattern (a chiasmus), one could naturally suspect that there might be other sections with a similar pattern. But there is a second possible key: the opening and closing sections of the psalm are structured as couplets. The suspicion thus arises that couplets are going to play a role in the rest of the psalm, which is indeed the case!

Three couplets (vv. 4-5; 6-7; 8-9) follow the opening couplet (vv. 2-3). These are followed by a three-line strophe (vv. 10-12) before another couplet is encountered (vv. 13-14). This is followed by two three-line strophes (vv. 15-17; 18-20) before there are another three couplets (vv. 21-22; 23-24; 25-26). Then follows the closing couplet (vv. 27-28).

3 The Shalom of the Impious and the Pious (vv. 4-9; 21-26)

3.1 Translation and Structure

It is no coincidence that three couplets (vv. 4-5; 6-7; 8-9) follow the opening couplet (vv. 2-3) and three couplets (vv. 21-22; 23-24; 25-26) precede the closing one (vv. 27-28), especially if third person plural suffixes and third person plural verbs dominate in the first unit, while first person singular pronouns, suffixes and verbs dominate in the second. The first combination of three couplets (vv. 4-9) concerns the impious folks, while the second combination of three couplets (vv. 21-26) concerns the pious Israelite. Moreover, the first line of each of the two strophes commences with the particle  (cf. v. 4; v. 21) and the words

(cf. v. 4; v. 21) and the words  ("heaven") and

("heaven") and  ("earth") are found in both of the last couplets (cf. vv. 8-9; 25-26).

("earth") are found in both of the last couplets (cf. vv. 8-9; 25-26).

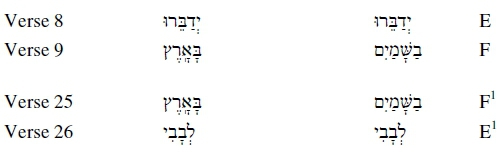

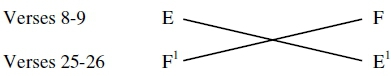

This is not the only similarity and difference to be observed between the last couplets of the two strophes under discussion. The closing couplets (vv. 8-9; 25-26) of the two strophes contain a further example: two similar words recur in each. The word  is repeated in v. 8, while the word

is repeated in v. 8, while the word  is repeated in v. 26. Some scholars propose that the second

is repeated in v. 26. Some scholars propose that the second  in v. 26 should be deleted. James Crenshaw is one of these.26 He maintains that the change would improve the MT,allowing for the following translation: "My flesh and my heart may waste away; God is my rock and portion for ever." But he immediately rejects his own proposal in a footnote which states: "This choice of the easier text violates the principle of textual criticism that the most difficult text is preferable."27

in v. 26 should be deleted. James Crenshaw is one of these.26 He maintains that the change would improve the MT,allowing for the following translation: "My flesh and my heart may waste away; God is my rock and portion for ever." But he immediately rejects his own proposal in a footnote which states: "This choice of the easier text violates the principle of textual criticism that the most difficult text is preferable."27

The lines in which the recurring words appear also catch the eye. In the first case the word  is repeated in the first line of the last couplet (v. 8 of vv. 8-9), while in the second case the word

is repeated in the first line of the last couplet (v. 8 of vv. 8-9), while in the second case the word  is repeated in the second line of the last couplet (v. 26 of vv. 25-26). There are thus a chiasmus in the two contrasting couplets:

is repeated in the second line of the last couplet (v. 26 of vv. 25-26). There are thus a chiasmus in the two contrasting couplets:

The chiasmus can be set out as follows:

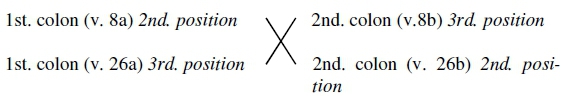

But there is a second chiasmus in these couplets which becomes apparent when the position of the recurring words in the two respective lines is considered. In v. 8, the recurring word  takes second position in the first colon (v. 8a) and third position in the second colon (v. 8b). In v. 26 the recurring word

takes second position in the first colon (v. 8a) and third position in the second colon (v. 8b). In v. 26 the recurring word  takes third position in the first colon (v. 26a) and second position in the second colon (v. 26b). This can be set out as follows:

takes third position in the first colon (v. 26a) and second position in the second colon (v. 26b). This can be set out as follows:

It is no coincidence that there are two chiasmi in these couplets. The psalmist is trying to communicate something important to his readers.

3.2 Comments

It is evident that the first three couplets (vv. 4-5; 6-7; 8-9) form a strophe which focuses on the impious folks (B), while the second combination of three couplets (vv. 21-22; 23-24; 25-26) focuses on the pious Israelite (A). These two strophes stand in contrast with each other. The first strophe is concerned with the shalom of the impious folks, while the second one paints the shalom of the pious Israelite.

The bodies of the impious folks are in perfect condition. They are well nourished, and have no cares, unlike other people (vv. 4-5). They are wealthy, but do not use their wealth to alleviate others' misfortunes, instead oppressing them and imposing their will on them (vv. 6-7). Doing evil and oppressing others is second nature to them and they boast about it everywhere, "from heaven down to earth" (vv. 8-9).

The pious Israelite, on the other hand, endures agonies. His heart and kidneys are in turmoil and he acts like an unreasoning fool who has no knowledge (vv. 21-22). However, instead of abandoning him, God stays with him. Taking him by the right hand, he leads him by his counsel. Eventually he will receive him with honour (vv. 23-24). Verse 24 has occasioned considerable discussion as to what the author is trying to say. Some, for instance, John Day, maintain that he was referring to life after death.28 He argues as follows: ". . . since he already has communion with Yahweh (v. 23), it seems more natural to suppose that 'afterward' refers to the time after death. 29 I do not find Day's arguments convincing. The two lines of the couplet (vv. 23-24) communicate more or less the same idea, as we are dealing with synonymous parallel lines. The repetition of the word  ("with you") in each of the three couplets of the strophe communicates a sense of the here and now. The psalmist is simply saying that, after all the suffering and spiritual agony, God will restore him to honour in this life.30 There is thus nothing in heaven or on earth that he cherishes as much as God's presence, which is found nowhere else but in the sanctuary (v. 17). Roland Murphy correctly draws readers' attention to "the intense 'I-thou' relationship" described in these verses.31 This is shalom for the pious Israelite, and this type of shalom is preferable to that experienced by the impious folks. Companionship with God is far better than health, wealth and prosperity. This is a new understanding of the meaning of shalom and is consequently an adjustment of the traditional wisdom paradigm.

("with you") in each of the three couplets of the strophe communicates a sense of the here and now. The psalmist is simply saying that, after all the suffering and spiritual agony, God will restore him to honour in this life.30 There is thus nothing in heaven or on earth that he cherishes as much as God's presence, which is found nowhere else but in the sanctuary (v. 17). Roland Murphy correctly draws readers' attention to "the intense 'I-thou' relationship" described in these verses.31 This is shalom for the pious Israelite, and this type of shalom is preferable to that experienced by the impious folks. Companionship with God is far better than health, wealth and prosperity. This is a new understanding of the meaning of shalom and is consequently an adjustment of the traditional wisdom paradigm.

The old paradigm claimed that blessings in the form of prosperity, health and wealth would be bestowed on those with clean hands and a pure heart rather than on those with dirty hands and an impure heart. The adjusted paradigm allows the author to claim that the pious Israelite who does not always experience health, wealth and prosperity, is blessed: "Proof of God's goodness rests in divine presence, not in material prosperity."32

The closing couplets of the two strophes are extremely important. The reader should remain aware that two chiasmi were identified in the previous section. The recurring words are particularly interesting. The impious folks chatter and boast about their evil deeds. "They speak evil from below and they talk oppression from on high" (v. 8). The pious Israelite, on the other hand, confesses his trust in the God of Israel. This is suggested by the recurrence of the word  God is his "heart's rock"

God is his "heart's rock"  and his portion.

and his portion.

4 The Four Strophes of the Middle Section (vv. 10-20)

4.1 Translation and Structure

How the author eventually comes to his adjustment of the wisdom paradigm is revealed in vv. 10-20 (the middle section of the psalm). This section consists of (1) a three-line strophe (vv. 10-12) which focuses on the impious folks; (2) a couplet (vv. 13-14) focusing on the pious Israelite; (3) a three-line strophe (vv. 15-17) focusing on the pious Israelite, and (4) a second three-line strophe (vv. 18-20) focusing on the impious folks. When one assigns the symbols A and Β to the strophes focusing on the pious Israelite and the impious folks respectively, a chiasmus presents itself. However, this chiasmus has already been identified (cf. section C.3 of the article) and is merely repeated here without comment.

But there is also a parallel between the first two and last two strophes of the middle section. This becomes evident when one considers the word and particles that recur in the strophes.

The verb " ("say") recurs in the first and the third strophes of the middle section, while the particle ("indeed") recurs in the second and fourth strophes of the same section (vv. 10-20). It can be set out as follows:

("say") recurs in the first and the third strophes of the middle section, while the particle ("indeed") recurs in the second and fourth strophes of the same section (vv. 10-20). It can be set out as follows:

The two sections run parallel. Nevertheless, we should not lose sight of the fact that the particle " also occurs in v. 1. Some scholars use this repetition as a means of structuring the psalm into three sections: (1) vv. 1-12, (2) vv. 13-17, (3) vv. 18-28.33 However, the repetition of

also occurs in v. 1. Some scholars use this repetition as a means of structuring the psalm into three sections: (1) vv. 1-12, (2) vv. 13-17, (3) vv. 18-28.33 However, the repetition of  in vv. 13 and 18 merely links the pious Israelite's thoughts (vv. 13-14) and the impious folks' fate (vv. 18-20) to the wisdom saying (v. 1). The writer admits that piety does not deliver the outcomes claimed for it by the wisdom teachers (vv. 13-14). Such are his thoughts before he visits the sanctuary (v. 17). As soon as he visits the temple, it transpires that the impious folk will eventually experience disasters and calamities (vv. 18-20).

in vv. 13 and 18 merely links the pious Israelite's thoughts (vv. 13-14) and the impious folks' fate (vv. 18-20) to the wisdom saying (v. 1). The writer admits that piety does not deliver the outcomes claimed for it by the wisdom teachers (vv. 13-14). Such are his thoughts before he visits the sanctuary (v. 17). As soon as he visits the temple, it transpires that the impious folk will eventually experience disasters and calamities (vv. 18-20).

4.2 Comments

The first strophe (vv. 10-12) again focuses on the shalom of the impious folks. They have followers  who benefit from the relationship because "they have abundant waters"

who benefit from the relationship because "they have abundant waters"  v. 10b). They share in the ill-gotten gains, and all of them claim that God does not notice what they are doing. He is oblivious to whatever it is they are busying themselves with (v. 11). They amass wealth and nobody opposes them and they are "unperturbed till the end"

v. 10b). They share in the ill-gotten gains, and all of them claim that God does not notice what they are doing. He is oblivious to whatever it is they are busying themselves with (v. 11). They amass wealth and nobody opposes them and they are "unperturbed till the end"  v. 12b). Although v. 10 is difficult to translate and interpret, the overall impression gained from the strophe is that it fits extremely well with what is said about the impious folks.

v. 12b). Although v. 10 is difficult to translate and interpret, the overall impression gained from the strophe is that it fits extremely well with what is said about the impious folks.

In contrast with the impious folks stands the pious Israelite (vv. 13-14). He confesses that he has kept his heart clean and his hands free from evil, but to no avail (v. 13), and he is totally disheartened. He stands empty-handed. He cannot show blessings or benefits. Verse 14 is extremely difficult to translate, especially the second colon  However, when one takes the particle

However, when one takes the particle  of

of  as expressing duration of time,34 a parallel line can be created which shows that he has lived an unwaveringly upright daily life: "I remained vigilant the whole day, admonished myself morning after morning." However, most scholars interpret this line as reflecting the author's afflictions. Whichever way one translates the couplet, it tells the reader that the pious Israelite can speak only of pain and suffering (vv. 13-14). His life has been a failure. His way of living has produced no positive outcome.

as expressing duration of time,34 a parallel line can be created which shows that he has lived an unwaveringly upright daily life: "I remained vigilant the whole day, admonished myself morning after morning." However, most scholars interpret this line as reflecting the author's afflictions. Whichever way one translates the couplet, it tells the reader that the pious Israelite can speak only of pain and suffering (vv. 13-14). His life has been a failure. His way of living has produced no positive outcome.

The couplet (vv. 13-14) on the vanity of living an upright life is followed immediately by a three-line strophe (vv. 15-17) reflecting a sudden change. The author confesses that he has been unable to comprehend why the impious folks prosper, given the assurance of the wisdom paradigm that impious and wicked people will not be blessed. He has even entertained the possibility of telling people that righteousness does not pay (v. 15a). He has virtually spoken in the manner of the impious. But he has been held back by the circle of God's children  , the community to which he belongs (v. 15b). He confesses that he has really tried to understand but that things have not made sense to him as they should have (v. 16). Everything has remained an enigma to him, that is, until he visits the sanctuary (v. 17a). "The burden is lifted, and the palmist proceeds to tell others what is now certain."35 This strophe narrates the author's sudden understanding of what will become of the impious folks. They may experience health, wealth and prosperity now, but somewhere in the future this will come to an end (v. 17b).

, the community to which he belongs (v. 15b). He confesses that he has really tried to understand but that things have not made sense to him as they should have (v. 16). Everything has remained an enigma to him, that is, until he visits the sanctuary (v. 17a). "The burden is lifted, and the palmist proceeds to tell others what is now certain."35 This strophe narrates the author's sudden understanding of what will become of the impious folks. They may experience health, wealth and prosperity now, but somewhere in the future this will come to an end (v. 17b).

Verse 17 should not be singled out as the pivot of the psalm. According to my analysis of the structure, the second and second-last strophes play a far more important role in the structure. The final couplets (vv. 8-9; 25-26) of these strophes hold the key to what the author has been trying to communicate. The threefold chiasmus (discussed above) tells it all. Everything is suddenly turned upside down. The impious folks may, for the time being, boast about their prosperity and contemplate evil, but their end will be disastrous. On the other hand, the pious Israelite, who suffers agonies and doubts, is rewarded by experiencing God's presence in his sanctuary and that is the author's shalom. He has eventually realised that health, wealth and prosperity cannot be everything when seen in the light of retribution. The greater blessing is to experience God's presence, not to acquire material things. The second three-line strophe (vv. 15-17) thus communicates the successful adjustment of the wisdom paradigm.

When, in the last strophe (vv. 18-19), the author reverts to the fate of the impious folks, their future looks bleak. Everything speaks of failure.

Indeed, you put them on slippery ground;

you let them fall down in ruins.

How suddenly they are destroyed;

they die, they decay - a total waste!

Like a dream when the Lord awakes;

when you arise, you despise their image.

E THE BOOK OF QOHELETH AND THE WISDOM PARADIGM

1 Introduction

The aim of the article is not only to analyse Ps 73 but also to show how two different Israelite wisdom teachers engaged the traditional wisdom paradigm. For this purpose I decided to compare the author of Ps 73's engagement with that of the author of the book of Qoheleth's. However, since it is not possible to analyse the whole book, Qoh 7:15-22 will suffice as an example of the author's reflections and engagement. 36 This section contains (as is the case with Ps 73) a wisdom saying (Qoh 7:19) echoing the traditional wisdom ideology. However, it will become evident that the author did not embrace the traditional wisdom paradigm although the quoted saying leaves that impression. Not all scholars agree that this is a coherent section, or rather that the section ends with v. 22. Some are of the opinion that vv. 23-24 (or even 23-29) should be added.37 Others, on the other hand, identify two separate units: Qoh 7:15-18 and Qoh 7:19-24.38

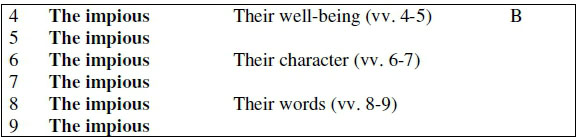

2 Qoheleth 7:15-22

3 Translation

15. In my vain life I have seen everything:

there is a righteous man who perishes in his righteousness, and there is a wicked man who prolongs his life in his evil-doing.39

16. Do not be over-righteous and do not be over-wise. Why should you destroy yourself?

17. Do not be over-wicked and do not be a fool. Why die before your time?

18. It is good to hold on to the one and not lose hold of the other; for he who fears God will take heed of both.

19. "Wisdom makes a wise man stronger than ten rulers in the city."40

20. But (take note) there is no one on earth so righteous that he will always do right and never wrong.

21. Therefore, do not pay attention to everything others are saying or you may hear your servant speak ill of you;

22. for you know very well how many times you yourself have spoken ill of others.

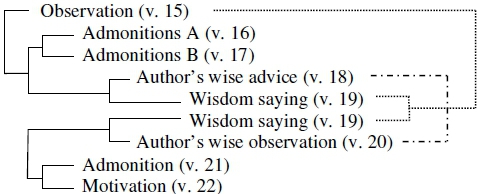

4 Structure and Comments

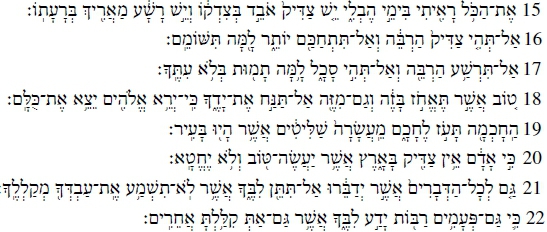

The author starts with an observation (v. 15) which is clearly at variance with the traditional wisdom paradigm: a righteous person perishes while living a good life while a wicked person is blessed with a long life. This is not what one expects to see in life since the traditional wisdom teaches that no harm will come to the upright but that the wicked will experience evil and early death (cf. Prov 12:21). On account of this the author then formulates two admonitions (vv. 16-17) which have the same structure that can be presented as follows:

Verse 16a a negative admonition  Verse 17a

Verse 17a

Verse 16b a negative admonition  Verse 17b

Verse 17b

Verse 16c a rhetorical question  Verse 17c

Verse 17c

The content of the two verses makes them antithetic parallel lines. Verse 16 focuses on the righteous person while v. 17 focuses on the wicked one. However, the structure of the two verses is exactly the same: two negative admonitions are followed by a rhetorical question.41 "Do not be over-righteous and do not be overwise. Why should you destroy yourself?" (v. 16); "Do not be over-wicked and do not be a fool. Why die before your time?" (v. 17). But the four admonitions form a chiasmus which should not go unnoticed:

The author of Qoheleth is extremely fond of using chiasmi to emphasise his stance.42 Currently a large number of scholars agree that the author is not promoting moderation or a mid-way between being over-righteous and over-wicked.43 He wants to emphasise that righteousness as well as wickedness can lead to an early death. The focus of the parallel lines falls on the rhetorical question at the end of the lines. The author claims that wisdom cannot control the roll of the dice! A righteous person can experience an early death and a wicked one can experience a long life (or an early death) even if they excel in righteousness or wickedness.

What follows next is the author's own advice to his readers: "It is good to hold on to the one and not lose hold of the other" (v. 18). The first part of v. 18 looks like a typical better-saying and the author surely meant it as such. If the traditional wisdom cannot guarantee success and a long life, it is better to follow the author of Qohelet's wise advice not to be over-righteous or over-wicked. Scholars agree that the content of v. 18 refers back to the admonitions. The reader should take both admonitions  to heart. Neither of them guarantees a long life. The author of Qoheleth goes even further and adds a motivation to his better-saying: "for he who fears God will take heed of both" (v. 18c). Once again he makes use of the words of the traditional wisdom teachers but overlays it with his own meaning. The fear of God which he promotes is not reverence but anxiety and fear of a powerful being whose acts no one can predict - not even the traditional wisdom teachers with their ideology of retribution.

to heart. Neither of them guarantees a long life. The author of Qoheleth goes even further and adds a motivation to his better-saying: "for he who fears God will take heed of both" (v. 18c). Once again he makes use of the words of the traditional wisdom teachers but overlays it with his own meaning. The fear of God which he promotes is not reverence but anxiety and fear of a powerful being whose acts no one can predict - not even the traditional wisdom teachers with their ideology of retribution.

To support the wisdom which he formulated in vv. 16-18, the author quotes a wisdom saying: "Wisdom makes a wise man stronger than ten rulers in the city" (v. 19), but as we know by now, he does not ascribe to the paradigm which promotes this kind of thinking and therefore the saying should be understood ironically. With this saying (which he uses with tongue in his cheek) he claims that wisdom is indeed powerful. However he immediately undermines the wisdom saying in the verses which follow (vv. 20-22).

Verse 19 (the wisdom saying) should not be transposed to another section in the book as Michael Fox argues.44 It is also not a mere parenthesis as James Loader opines.45 It functions on two levels. It underpins the author's wisdom, but - being a traditional wisdom saying - it cannot be left as it is. It needs to be relativised. The traditional wisdom paradigm cannot go unchallenged. Irony certainly plays a role here and only a few scholars recognise this.46

The author continues with his irony by stating a fact which no one can contradict: "There is no one on earth so righteous that he will always do right and never any wrong" (v. 20). Given the context one may even say that this statement can be linked to what has been said earlier: the over-righteous person's acts have the possibility of causing him harm. This is illustrated with an example of people talking behind other people's backs (vv. 21-22). There is no one on earth who does not from time to time discuss other people and their acts when those are not in the vicinity. It is therefore good not to pay attention to what others are discussing when you are in a hearing distance since you may discover that you are the topic of discussion (v. 21). However, the author emphasises that all and sundry take part in such actions. No one should thus claim that his/her hands are clean "for you know very well how many times you yourself have spoken ill of others" (v. 22).

The author's reasoning in this passage can be illustrated with the following layout:

The passage consists of two sub-units (vv. 15-19; 19-22). Verse 19 forms a hinge between them and is therefore duplicated. The verse serves as a warrant for the wisdom which the author developed in the first unit (vv. 15-19). It bolsters his wisdom. However, since it is a wisdom saying reflecting the views of the traditional wisdom teachers it needs to be undermined so that the author's arguments in the first unit remains intact. There is a definite link between the observation which the author commences with (v. 15) and the wisdom saying which he later on quotes (v. 19). Both concern the wisdom paradigm with which the traditional wisdom teachers operate. According to the paradigm success, health, wealth and longevity follow in the wake of righteousness and wisdom, and failure, misery, poverty and early death in the wake of wickedness and folly. However, there is also a link between the author's wise advice (v. 18) and his wise observation (v. 20). It is good to pay attention to both admonitions (v. 18) because  there is no one on earth who is righteous and never does any wrong (v. 20).47

there is no one on earth who is righteous and never does any wrong (v. 20).47

To highlight the fact that the wisdom saying (v. 19) functions on two levels it is duplicated in the structure above. It functions as warrant for the author's wisdom but it also serves as a wisdom saying to be undermined and ridiculed. The author says "yes" and "no" simultaneously. This passage may also serve as an illustration of how the author of Qoheleth uses irony in his arguments.48 He often fakes his agreement with what the traditional wisdom teachers communicate but he never totally ascribe to the paradigm in which they are at home.

F CONCLUSION

The author of Ps 73 and the author of Qoheleth both underwent experiences that did not concur with the traditional wisdom paradigm. The author of Qoheleth wrote: "In my vain life I have seen everything: there is a righteous man who perishes in his righteousness, and there is a wicked man who prolongs his life in his evil-doing" (Qoh. 7:15). This concurs with what the author of Ps 73 experienced. He, too, saw how impious folks experienced health, wealth and prosperity, while he "kept his heart pure and his hands clean" (Ps 73:13). Both tried to come to terms with these contradictions. One wrote a whole book, the other a poem, and both of them made use of quotations. However, while the author of Qoheleth undermined the traditional wisdom paradigm, the author of Ps 73 tried to keep it intact.

The author of Qoheleth concluded that nothing made sense; everything was futile, especially if the doctrine of retribution served as a benchmark. The author of Ps 73, on the other hand, followed another route. He adjusted the wisdom paradigm and redefined the implications of shalom. In doing this, he successfully kept the traditional wisdom paradigm intact.

An English saying goes: "There are many ways to skin a cat." In similar vein, these two pieces of literature reflect how various Jewish thinkers came to terms with contradictions and doubts. One abandoned the old wisdom paradigm in its entirety, while the other adjusted the paradigm and consequently redefined the outcome.

It might serve theology well if people realised that we do not all have to emulate the author of Ps 73. If there is a place in the Bible for a book like Qoheleth, then there should be a place for those who cannot think like the author of Ps 73 and follow his example. There should be room for those who, like the author of Qoheleth, would like to say: "I can no longer believe that; it doesn't make sense to me."49

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barbour, Ian G. Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues. London: SCM, 1998. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James L. Ecclesiastes. Old Testament Library. London: SCM, 1988. [ Links ]

____. "Standing Near the Flame: Psalm 73." Pages 109-127 in The Psalms: An Introduction. Edited by James L. Crenshaw. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001. [ Links ]

Davidson, Robert. Courage to Doubt: Exploring an Old Testament Theme. London: SCM, 1983. [ Links ]

Day, John. Psalms. Old Testament Guides. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1990. [ Links ]

Fokkelman, Jan P. Reading Biblical Poetry: An Introductory Guide. Louisville: Westminister John Knox, 2001. [ Links ]

____. The Psalms in Form: The Hebrew Psalter in its Poetic Shape. Tools for Biblical Studies 4. Leiden: Deo Publishing, 2002. [ Links ]

Fox, Michael V. A Time to Tear Down and A Time to Build Up: A Rereading of Ecclesiastes. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999. [ Links ]

Cordis, Robert. "Quotations in Wisdom Literature." Jewish Quarterly Review 30 (1939/40): 123-147. [ Links ]

Greinacher, Norbert. "Norbert Greinacher." Pages 45-51 in How I Have Changed: Reflections on Thirty Years of Theology. Edited by Jürgen Moltmann. Translated by John Bowden. London: SCM, 1997. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar and Erich Zenger. Psalmen 51-100. Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg: Herder, 2000. [ Links ]

Krauss, Hans-Joachim. Psalmen 64-150. Volume 2 of Psalmen. Biblischer Kommentar 15/2. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1972. [ Links ]

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1970. [ Links ]

Lauha, Aarre. Kohelet. Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978. [ Links ]

Loader, James A. Polar Structures in the Book of Qohelet. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 152. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1979. [ Links ]

____. Prediker. Tekst en toelichting. Kampen: Kok, 1984. [ Links ]

Longman, Tremper III. The Book of Ecclesiastes. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Miller, Patrick D. "Psalm 73 as a Canonical Marker." Pages 298-309 in Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays. Edited by Patrick D. Miller. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series 267. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Murphy, Roland E. Wisdom Literature and Psalms. Interpreting Biblical Texts. Nashville: Abingdon, 1983. [ Links ]

Noll, Mark A. Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible. Leicester: Apollos, 1991. [ Links ]

Ogden, Graham. Qoheleth. Readings: A New Biblical Commentary. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. "The Psalms." Pages 364-436 in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Edited by James D. G Dunn and John W. Rogerson. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Robinson, John A. T. The New Reformation? London: SCM, 1965. [ Links ]

Ross, James F. "Psalm 73." Pages 161-175 in Israelite Wisdom: Theological and Literary Essays in Honor of Samuel Terrien. Edited by John G. Gammie, Walter A. Brueggeman, W. Lee Humphreys and James M. Ward. New York: Scholars Press, 1978. [ Links ]

Schellenberg, Annette. Kohelet. Züricher Bibelkommentare. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag, 2013. Not cited in text. [ Links ]

Schoors, Antoon. Vocabulary. Volume 2 of The Preacher Sought to Find Pleasing Words: A Study of the Language of Qoheleth. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 143. Louvain: Peeters, 2004. [ Links ]

____. Ecclesiastes. Historical Commentary on the Old Testament. Louvain: Peeters, 2013. [ Links ]

Seow, Choon-Leong. Ecclesiastes. The Anchor Bible 18C. New York: Doubleday, 1997. [ Links ]

Spangenberg, Izak J. J."Gedigte oor die dood in die boek Prediker." D.Th. thesis, University of South Africa, 1986. [ Links ]

____. "Quotations in Ecclesiastes: An appraisal." Old Testament Essays 4 (1991): 19-35. [ Links ]

____. Die Boek Prediker. Bybeluitleg vir Bybelstudent en Gemeente. Kaapstad: NG Kerk-uitgewers, 1993. [ Links ]

____. "Irony in the Book of Qohelet." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 72(1996): 57-69. [ Links ]

____. "Will Synchronic Study of the Pentateuch Keep the Scientific Study of the Old Testament Alive in the RS A?" Pages 138-151 in South African Perspectives on the Pentateuch between Synchrony and Diachrony. Edited by Jurie le Roux and Eckart Otto. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 463. London: T&T Clark, 2007. [ Links ]

Terrien, Samuel. The Psalms and Their Meaning for Today. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952. [ Links ]

Van der Ploeg, Johannes. Psalmen. Boeken van het Oude Testament. Roermond: J.J. Romen & Zonen, 1971. [ Links ]

Weber, Günther. Ich glaube, ich zweifele: Notizen im nachhinein. Zürich: Benzinger Verlag, 1996. [ Links ]

____. I Believe, I Doubt: Notes on Christian Experience. London: SCM, 1998. [ Links ]

Whybray, Roger N. "Qoheleth the Immoralist? (Qoh 7:16-17)." Pages 191-204 in Israelite Wisdom: Theological and Literary Essays in Honor of Samuel Terrien. Edited by John G. Gammie, Walter A. Brueggeman, W. Lee Humphreys and James M. Ward. New York: Scholars Press, 1978. [ Links ]

Williams, Ronald J. Hebrew Syntax: An Outline. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976. [ Links ]

Article submitted: 24/02/2016

Article accepted: 4/04/2016

Izak (Sakkie) J. J. Spangenberg, Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, UNISA, Email: spangijj@unisa.ac.za

1 Ian G. Barbour, Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues (London: SCM Press, 1998), 135.

2 My academic career started in 1979 at the Rand Afrikaans University, renamed the University of Johannesburg a few years after the change in government in 1994.

3 Norbert Greinacher, "Norbert Greinacher," in How I Have Changed: Reflections on Thirty Years of Theology (ed. Jürgen Moltmann; trans. John Bowden; London: SCM Press, 1997), 51.

4 Robert Davidson, Courage to Doubt: Exploring an Old Testament Theme (London: SCM Press, 1983); Günther Weber, I Believe, I Doubt: Notes on Christian Experience (London: SCM Press, 1998).

5 Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "Gedigte oor die dood in die boek Prediker" (D.Th. thesis, University of South Africa, 1986).

6 Davidson, Courage to Doubt, 201.

7 Günther Weber, Ich glaube, ich zweifele: Notizen im nachhinein (Zürich: Benzinger Verlag, 1996).

8 John A. T. Robinson, The New Reformation? (London: SCM Press, 1965), 18.

9 Weber, I believe, I doubt, 3.

10 Weber, I believe, I doubt, 3.

11 Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (2nd ed. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1970), 83.

12 Mark A. Noll, Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible (Leicester: Apollos, 1991), 45.

13 Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "Will Synchronic Study of the Pentateuch Keep the Scientific Study of the Old Testament Alive in the RSA?" in South African Perspectives on the Pentateuch between Synchrony and Diachrony (ed. Jurie le Roux and Eckart Otto; LHBOTS 463; London: T&T Clark, 2007), 138-151.

14 James L. Crenshaw, "Standing Near the Flame: Psalm 73," The Psalms: An Introduction (ed. James L. Crenshaw; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 122.

15 Crenshaw, "Standing Near," 111.

16 Crenshaw, "Standing Near," 111-112; 122-123.

17 Cf. Prov 15:29; Ps 37:18-20.

18 Robert Gordis, "Quotations in Wisdom Literature," JQR 30 (1939/40): 123-147; Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "Quotations in Ecclesiastes: An appraisal," ΟΊΕ4 (1991): 19-35; Izak J. J. Spangenberg, Die Boek Prediker (BBG; Kaapstad: NG Kerk-uitgewers, 1993), 11-12.

19 Johannes van der Ploeg, Psalmen (BOT; Roermond: J.J. Romen & Zonen, 1971), 444; Willem S. Prinsloo, "Psalms," in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (ed. James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 399.

20 Prinsloo, "Psalms," 399.

21 Hans-Joachim Krauss proposes that  should be changed back to

should be changed back to  since the Elohistic redactor originally changed the words. Cf. Hans-Joachim Krauss, Psalmen 64-150 (vol. 2 of Psalmen; BK 15/2; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1972), 502.

since the Elohistic redactor originally changed the words. Cf. Hans-Joachim Krauss, Psalmen 64-150 (vol. 2 of Psalmen; BK 15/2; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1972), 502.

22 Jan P. Fokkelman, Reading Biblical Poetry: An Introductory Guide (Louisville: Westminister John Knox, 2001), 141-142.

23 Jan P. Fokkelman, The Psalms in Form: The Hebrew Psalter in its Poetic Shape (TBS 4; Leiden: Deo Publishing, 2002), 81.

24 Patrick D. Miller, "Psalm 73 as a Canonical Marker," in Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays (JSOTSup 267; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), 298-299.

25 James F. Ross, "Psalm 73," in Israelite Wisdom: Theological and Literary Essays in Honor of Samuel Terrien (ed. John G. Gammie, et al.; New York: Scholars Press, 1978), 164.

28 Terrien cherishes similar viewpoints. See Samuel Terrien, The Psalms and Their Meaning for Today (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952), 254.

29 John Day, Psalms (OTG; Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1990), 132.

30 Davidson, Courage to Doubt, 35.

31 Roland E. Murphy, Wisdom Literature and Psalms (IBT; Nashville: Abingdon, 1983), 148.

33 Van der Ploeg, Psalmen, 439; Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalmen 51-100 (HTKOT; Freiburg: Herder, 2000), 338, 342, 347.

34 Ronald J. Williams, Hebrew Syntax: An Outline (2nd ed.; Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976), 48.

35 Crenshaw, "Standing Near," 123.

36 I found support for this decision in both Aarre Lauha's and Tremper Longman Ill's commentaries. Concerning this section Lauha writes: "Der vorliegende Abschnitt ist in dieser Hinsicht [im Leben bewahrheitet sich die Gerechtighet nicht] eine der aufschlussreichsten Stellen im Predigerbuch. Kohelet gerät hier in einen verhăngnisvollen Konflikt mit herkömmlichen weisheitlichen Grundanschauungen." Cf. Aarre Lauha, Kohelet (BKAT; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1978), 135. In his discussion of this section Longman even compares Qoheleth with Psalm 73 and writes: "Thus, Qohelet struggled with the same conflict faced by the psalmist in Psalm 73, but without reaching the same resolution. Instead, Qohelet's observation leads him to offer some socking advice." Cf. Tremper Longman III, The Book of Ecclesiastes (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 195.

37 Antoon Schoors regards Qoh 7:15-24 as a coherent unit focusing on "the problem of justice and wickedness." Cf. Antoon Schoors, Ecclesiastes (HCOT; Louvain: Peeters, 2013), 538. Choon-Leong Seow takes Qoh 7:15-29 as a unit in which the elusiveness of righteousness and wisdom are discussed. Cf. Choon-Leong Seow, Ecclesiastes (AB 18C; New York: Doubleday, 1997), 251.

38 Graham Ogden, Qoheleth (Readings; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987), 112-119. I was once convinced that Qoh 7:15-18 and 7:19-22 are two separate units. Cf. Spangenberg, Boek Prediker, 112. However, I recently changed my mind on account of the role which the wisdom saying (Qoh 7:19) plays in this section and on account of the reference to the "righteous" in v. 20 and the repetition of the word "good" in vv. 18 and 20.

39 This is Whybray's rendering of the verse in Roger N. Whybray, "Qoheleth the Immoralist? (Qoh 7:16-17)," in Israelite Wisdom: Theological and Literary Essays in Honor of Samuel Terrien (ed. John G. Gammie, et al.; New York: Scholars Press, 1978), 202.

40 I agree with Lauha who is of the opinion that v. 19 is a traditional wisdom saying but disagree with him that it stands in a loose relationship to the rest of the passage. Cf. Lauha, Kohelet, 134.

41 Whybray, "Qoheleth," 191-192; Ogden, Qoheleth, 113-114; Schoors, Ecclesiastes, 546.

42 According to James A. Loader "|t |here are 38 chiastic structures in the book." Cf. James A. Loader, Polar Structures in the Book of Qohelet (BZAW; Berlin: De Gruyter, 1979), 13. This coincides with the number of times that the word  is used in the book! Cf. Antoon Schoors, Vocabulary (vol. 2 of The Preacher Sought to Find Pleasing Words: A Study of the Language of Qoheleth (OLA 143; Louvain: Peeters, 2004), 119.

is used in the book! Cf. Antoon Schoors, Vocabulary (vol. 2 of The Preacher Sought to Find Pleasing Words: A Study of the Language of Qoheleth (OLA 143; Louvain: Peeters, 2004), 119.

43 To my knowledge Tremper Longman III is the only recent scholar who promotes the idea that Qoheleth is advising "a kind of middle-of-the-road approach to life" in v. 18. Cf. Longman III, Ecclesiastes, 196.

44 Michael V. Fox, A Time to Tear Down and A Time to Build Up: A Rereading of Ecclesiastes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 256-257, 262.

45 James A. Loader, Prediker (TT; Kampen: Kok, 1984), 101-102.

46 Lauha, Kohelet, 133-135.

47 Cf. James L. Crenshaw, Ecclesiastes (OTL; London: SCM, 1988), 143: "The kt can refer to 7:18 ('hold on to both'); if so, this gives the basis for that advice."

48 More about irony in the book can be found in Izak J. J. Spangenberg, "Irony in the Book of Qohelet," JSOT72 (1996): 57-69.