Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.28 n.3 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n3a16

The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah revisited: Military and political reflections

Robert Kuloba Wabyanga

Kyambogo University, Uganda

ABSTRACT

That Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis have been a subject of constant cognitive itch is a truism rather than fiction. Aware that the HB is an ideological text, the story of Jordan states notably Sodom and Gomorrah may need further reflections outside sexual frontlines but from the perspectives of political dynamics of the ANE. This paper explores Sodom and Gomorrah as a political and military story that turned theological and ideological. I opine that the fire that razed Sodom and Gomorrah could have been the result of military invasion(s). What is however intriguing is the interest of the biblical writer: at what points would the military or political afterlife of Sodom and Gomorrah meet with the ideological interests of the Bible writer? What interests does the writer have in Sodom and Gomorrah that he finds it necessary not only to conceal the historical reality but also invent ideas and imageries of Sodom and Gomorrah as condemned cities? The paper employs Clines' and Exum's strategies of reading against the grain and defragmenting the stories. In this case, the different stories of Sodom and Gomorrah in chs. 10, 13, 14, 18 and 19 are read critically and in conversation with each other.

Keywords: Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham, crimes against humanity, military invasion, ideological criticism

A INTRODUCTION

That Sodom and Gomorrah have been a subject of constant cognitive itch is a reality rather than fiction. The visitors' book at the gates of these necropolises is awash with scholarly names, comments and addresses. The mystery surrounding these cities has enlisted several scholarly comments. Many scholars from as far-away fields like archaeology,1 history2 and theology have visited and revisited Sodom and Gomorrah3-certainly not as pilgrims but as curious investigators into the enigma of these ancient states. The HB preserves Sodom and Gomorrah as a mutilated and scattered whole. Once like the garden of God, the epitaphs of Sodom and Gomorrah are inscribed on malevolent monoliths as condemned cities in the ideological mausoleum of the HB. Sodom and Gomorrah in this ideological text are epitome of evil (especially in regard to human sexuality).

The majority of the theological commentators on Sodom and Gomorrah have approached the study of these cities from the point of view of the narrators: Sodom and Gomorrah are condemned either as sexually immoral or hostile and inhospitable. These theologians approve the ideology of the Bible author, and consequently, the interpretations of Sodom and Gomorrah texts have served to energise homophobic attitudes especially in some societies that are biased to heteronormative sexual orientations.

As an ideological writing, the narrative proposes that Sodom and Gomorrah and their environment were killed off, and their afterlife recreated: Sodom and Gomorrah (the land which Lot chose) is juxtaposed with the land of Canaan (that enjoys the ideological approval of the narratives)-the promised land.

I am revisiting Sodom and Gomorrah texts again,but not on matters of sex or archaeological geography. Mine is a detective approach, investigating the fire of Sodom and Gomorrah from the point of view of hermeneutics of suspicion. My suspicion-hereby the hypothesis is that Sodom and Gomorrah are likely victims of military arson and ideological denigration, namely that the story of Sodom and Gomorrah is a military story that turned ideological.

Figuratively speaking, Sodom and Gomorrah are victims of crimes against humanity commonly associated with armed conflicts. Sodom and Gomorrah's remains need to be subjected to the coroners for a forensic pathological analysis. The body samples of Sodom and Gomorrah are scattered in the areas of chs. 10, 13, 14, 18 and 19 of the textual field of Genesis. The scene should be visited by special committees of inquiry or investigation experts that investigate crimes against humanity. The study shall also draw from extra biblical sources and histories of the ANE in making conclusive postmortem examination remarks.

B THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This study is anchored on the assumption that the HB is an ideological text. Gold and Gold in their synthesis of Bell4 and Mitchell's5 definitions of ideology came up with these positions: ideology refers to justifications which can mask specific sets of interests; and ideology as "a pervasive set of ideas, beliefs and images that a group employs to make the world more intelligible to itself. . ."6 But Mitchell further opined that an ideology is

a system of symbolic representations that reflects a historical situation of domination by a particular class, and which serves to conceal the historical character and class bias of that system under guises of naturalness and universality.7

These assertions ideally imply that an ideology emerges from a historical context of a particular group that cherishes certain fundamental Interests. This group would perceive events of life or history in relation to their cherished Interests. As a result, there is a deliberate but careful process of mutation, amputation and fragmentation of realities of history to create ideas, beliefs and disfigured images, customised to nourish these Interests. In most cases, these ideas, beliefs and images created are mystified as the Will of the ultimate reality, and as such as godly, natural and universal. The writings of the OT, especially the Pentateuch8 and what came to be called the Deuteronomic literature are historiographies.9 Some of the tales, the events and the characters in the HB are fictional, producing what has been termed as "fictionalised history" and "historized fiction."10 But as Banks opines, the fictionalised history points to the fact that there is a core of historical knowledge available from the text; and that the historised fiction points to a fundamental motive11that is cherished by the producers of such literature.

Against this framework, it is important to be critical of important points where the military or political history of Sodom and Gomorrah meets with the ideological interests of the biblical author. What interests does the writer have in Sodom and Gomorrah that he finds it necessary not only to conceal the historical reality but also invent ideas and imageries of Sodom and Gomorrah as condemned cities?

C METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this study I have used two strategies: reading from left to right (reading against the grain), and defragmenting characters. Reading from left to right is David Clines' strategy,12 which is contrary to the conventional reading from right to left that adopts the ideology inscribed in the text.13 It is an approach that directly confronts questions of value and validity. It is a reading by way of critique, which is using the standards and moral values that come into play when reading other literature like newspapers, essays or novels. In reading any of these texts, Clines observes, we get engaged as thinking, feeling and judging persons, asking questions as: is this true? Is it the case? Can I accept it?

There is no comprehensive picture of Sodom and Gomorrah in the HB. Sodom and Gomorrah appear fragmented in Genesis and beyond. Fragmented characters in the HB inevitably present ambiguous imageries, and as Exum (who writes from a feminist perspective) opines, these fragments have not been taken in traditional biblical scholarship as fragments of the larger story but as the story in its gestalt.14 Exum advises that to construct versions of maligned characters, scholars should step outside the ideology of the biblical text.15Exum champions the defragmentation approach, a reading that pieces together the Bible's fragmented stories in order to create a holistic image of the characters.16

In reading these texts as a "thinking, feeling and judging" reader, one is confronted with many questions,17 but most importantly in this writing: if I cannot accept the ideological story as recorded in Genesis, are there any leading clues in the Bible that point to an untold story about Sodom and Gomorrah?

D SODOM AND GOMORRAH: TEXTS AND CONTEXT

The Sodom and Gomorrah narrative is in the context of Abrahamic narratives in the Book of Genesis. Questions regarding the historicity and purpose of Genesis and the entire Pentateuch have been widely discussed18. The common positions taken accentuate the ideological motive in weaving of these chapters and verses purposely to nourish the postexilic Judean interests. Like any other digests, the stories are customised and characters configured or disfigured in relation to the ideological currency they would convey to the community. In essence, using Bank's words, characters were fictionalises and fiction was characterised apparently to make the reality of exile and restoration intelligible to the community of Judah. The embroidery given to the characters in the texts was to energise the ideological convictions and also legitimate the way of life of the postexilic community and environment. Inevitably, the writer presents ambiguities in some scenes, and the audience, who is guided by the ideology, is to interpret the scenes "correctly."19

Salient in the Pentateuch is the doctrine of divine choice of the patriarchs and the people of Israel, against other nations and their people. This divine choice had benefits (and costs) as the land, many children, great name and fame-and inevitably special status of the chosen nation over other nations and their people. The narrators have not concealed the tendency of labelling nations and their people as evil-the people who do detestable things against Yahweh.

It is not surprising that the mention of Sodom and Gomorrah in Gen 13, 14, 18 and 19 is juxtaposed with Abraham. The divine choice of Abraham is very salient and the reason for his divine choice is stated (Gen 18:18-19).20Sodom and Gomorrah are rejected as the other. In this context, Abraham has three promises: (1) land; (2) seed; and (3) blessing. The promises came with a covenant, which among other issues included change of names and circumcision.21 Abraham and his offspring would become a great nation (Gen 12:2, being reiterated in 18:18; Gen 17:19, 21; 26:3-4; and Gen 28:13-14; 35:11; 46:3). Sodom and Gomorrah as nations, although they may look like the garden of God or Egypt, are not chosen.

In the following section, the paper focuses on what I have called Sodom and Gomorrah texts. From these texts, I have gleaned the remains of Sodom and Gomorrah for analysis in relation to the major themes of the paper.

1 Genesis 10:19

This chapter is the first incidence where Sodom and Gomorrah are mentioned in Genesis. The importance of Sodom and Gomorrah in this chapter is that it shares a borderline with Canaan-which in the development of the story is an important space in the ideological worldview of the HB.

2 Genesis 13

Chapter 13 is a key sample as it mentions Sodom and Gomorrah in a dispute between Abra[ha]m and Lot over the grazing land. The ancient states are described as part of the well-watered land of Jordan-akin to the Garden of Eden or Egypt (v. 10). In their dispute resolution, Lot chose the Jordan plains and settled in Sodom, as Abra[ha]m lived in Canaan. However, the biblical author's attitude against Sodom is not esoteric: without mentioning any particular sin, the people of Sodom are ebonised as greatly wicked and sinners against God ( [v. 13]).22

[v. 13]).22

3 Genesis 14

This chapter introduces a war scene in which Abra[ha]m participates as a combatant to liberate Lot. In this chapter, Sodom and Gomorrah are part of the five distinct kingdoms in the Jordan plains, which for 12 years had been subjected to the foreign domination of Elam. In the 13th year of foreign domination these five kingdoms (Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboyim, and Bela) rebelled against Elam. Lhe rebellion resulted into the battle of Sidiim, in which Elam and her three allies (Shinar, Ellasar, and Goyim) militarily defeated the five Jordan Plain kingdoms. Lhe battle ground is described as full of tar pits in which some of the kings (fighters?) of Sodom and Gomorrah fell, while others escaped to the hills (v. 10). Lhe war losses fell heavily on Sodom and Gomorrah and her allies in terms of properties and humans.

Verse 13 introduces an anonymous character-the informant who escapes from the valley of the battle field of Sidiim.23 Lhis character is constructed as one who knew Abra[ha]m and his relationship to Lot, and purpose driven to inform Abra[ha]m about the fate of Lot in the hands of the Elamites. In the turn of events, Elam and her allies-four of them, who had defeated the five Jordan states are defeated by the heroic character-Abraham. Verse 15 states that Elam and her allies were decisively beaten and defeated. The victorious Abraham does not only liberate Lot but also the properties and people of Sodom-men and women.

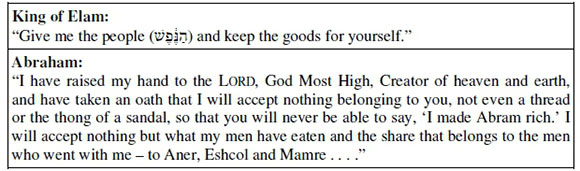

Verses 17-24 present the victorious Abraham being approached by two kings: the defeated and humbled king of Sodom in the valley of Shevah and Melchizedek24 King of Salem.25 The two characters are presented in apposition to each other in relation to their respective intent to Abraham:

The King of Sodom

- Demands for the status of recovered wealth and the prisoners of war from Abraham

- Patronises Abraham by offering recovered wealth

- He makes Abraham anxious and outraged, that results in an oath to Yahweh

Melchizedek, the King of Salem

- Blesses Abraham

- Offers bread and wine to Abraham

- His mission to offer peace and contentment to Abraham in Canaan

- Abraham offers tithes

Unlike Melchizedek, the king of Sodom does not bless Abraham. The remarks made by the king of Sodom are detestable to Abraham. The remarks are reworked in ideological terms to mean patronising the socio-economic status of Abraham. The king of Sodom is condescending over Abraham. The king of Sodom in all respects approaches Abraham with pride and arrogance. Melchizedek on the other hand, though king, offers Abraham bread and wine and blesses him. Bread in the cultural context of the ANE stood for food and indeed sustenance. The word  may mean the staple food or source of nourishment (see Gen 3:19): when God needed to chastise the Israelites, he threatened to break their "staff of bread" (Lev 26:26).26 On the other hand, wines were for celebrations.

may mean the staple food or source of nourishment (see Gen 3:19): when God needed to chastise the Israelites, he threatened to break their "staff of bread" (Lev 26:26).26 On the other hand, wines were for celebrations.  was the symbol of joy and a symbol of salvation.27 As McDonald has put it, "bread meant life but wine meant something extra added on to life."28 By offering bread and wine, Melchizedek offered hope and joy to Abraham. Abraham was to thrive and enjoy himself in Canaan.

was the symbol of joy and a symbol of salvation.27 As McDonald has put it, "bread meant life but wine meant something extra added on to life."28 By offering bread and wine, Melchizedek offered hope and joy to Abraham. Abraham was to thrive and enjoy himself in Canaan.

The narrative materialise the encounter between Abraham and the king of Sodom in terms of wealth and the prisoners of war recovered from Elam. These are the reasons why the king of Sodom met Abraham in the king's valley. In some rabbinic sources, the king of Sodom approached Abraham with hostile intent because Abraham seemed to have appropriated all the goods and prisoners for himself.29 This view may have some degree of plausibility if read in respect to Abraham's response. Accordingly, the conversation between the king of Sodom and Abraham is summarised as:

Abraham's response suggests the following: that he knew that the king of Sodom would offer his wealth to him and so he swore beforehand that he will not take anything. The reason for Abraham's refusal to take the wealth is so that the king of Sodom would say, "I made Abraham rich." This construct is of ideological benefit to the author of the narrative in two ways: on one hand, to delineate Abraham's wealth to a foreign agency and on the other to discredit the king of Sodom and his wealth. In the first incidence, the narrative portrays the blessed Abraham as rich and in that regard enriched by God; and receiving wealth from Sodom would obscure this ideal hence the fear that the king of Sodom would say, "I made Abraham rich." The narrative also serves to portray the blessed Abraham as one who gives: he gave a tenth of everything to Melchizedek.

It is however interesting to note that a foreign agency has been documented in Abraham's wealth in earlier chapters of the narrative. In Egypt Abraham was given plenty of wealth and human servants by the pharaoh, and by the time he moved from Egypt to the Negev, he was very rich in terms of silver, gold and livestock (Gen 12 and 13). In Gen 14, Abraham does not want to show anything in common with Sodom.

There are so many ambiguities in the text that result from unanswered questions by the narrative. If Abraham was to be subjected to an interrogation, he would have to answer the following questions: if you (Abraham) fought Elam to rescue Lot, what interests did you have in keeping the men of Sodom? Had the king of Sodom not approached you, would you have given back these people and the wealth recovered from the Elamites?

In respect to the rabbinic idea that Abraham could have appropriated the recovered war booty and people to himself, Abraham should be responding to the wrong question in the narrative or answering the right question wrongly. The right question from the king of Sodom should be that which demands for the return of the captured people and the account for the missing wealth. A question of this nature would befit well the response Abraham gave in 14:22-24, which I have embellished as follows:

I have raised my hand to the LORD, God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth, and have taken an oath that I took nothing belonging to you, not even a thread or the thong of a sandal, but what my men have eaten and the share that belongs to the men who went with me - to Aner, Eshcol and Mamre.

This response, in the first place is an oath. It is an oath of innocence. Read in conversation with Exod 22:10-11, Abraham makes an oath before Yahweh that he has himself not taken anything from the spoils of war, except that which his men-the fighters, have taken. In essence, Abraham is stating that he has not himself taken anything from the spoils of war, and at the same time confirming that his fighters have eaten and shared some of the booty. The narrative ends abruptly, without clarity about both the captives and the war spoils. The king of Sodom is a silent character. His voice in relation to the utterances made by Abraham is completely dimmed. The narrative is finally silent about the fate of the captives and the coveted wealth of Sodom. It has been the praxis of the HB to silence some characters in the narratives in order to conceal certain information and also kill off these characters. However, Sodom is not killed off here, as we see it in the subsequent chapters. What one can sense is that there is a bad relationship between Sodom and Abraham over the looted wealth and the recovered men, which the narrator wants to conceal. This chapter does not conceal Abraham's interests in Canaan-that of peaceful settlement in Canaan. The story also ends without giving attention to the status of both Elam in the Jordan kingdoms and Sodom and her allies in the region. It is clear that the author is interested in voicing Abraham's interests.

4 Genesis 18

Sodom and Gomorrah are reintroduced in vv. 16 to 33 of this chapter after a lapse in chs. 15-17.30 The angel-men (messengers), after relishing in Abraham's hospitality provisions reveal to Abraham their plans to destroy Sodom. In v. 19 the verb  (to know) is introduced in relation to Abraham, which is translated in various versions as to choose.31 The reason why Abraham is chosen by God is that "he will direct his children to keep the way of the Lord-doing what is right and just; so that the LORD will bring about for Abraham what he has promised him." In this verse, we find in what should have been a direct quotation, God addressing himself in third person instead of first person.32

(to know) is introduced in relation to Abraham, which is translated in various versions as to choose.31 The reason why Abraham is chosen by God is that "he will direct his children to keep the way of the Lord-doing what is right and just; so that the LORD will bring about for Abraham what he has promised him." In this verse, we find in what should have been a direct quotation, God addressing himself in third person instead of first person.32

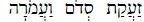

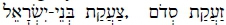

But in v. 20, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is in response to two issues, namely an outcry ( ) and the grave sin (which is unmentioned).33 Of interest is that the language of this verse is similar to that of Exod 3 and Judg 6:6-7 especially with the usage of the word

) and the grave sin (which is unmentioned).33 Of interest is that the language of this verse is similar to that of Exod 3 and Judg 6:6-7 especially with the usage of the word  (outcry). In these texts, the caring Yahweh would hear the outcry of his people-

(outcry). In these texts, the caring Yahweh would hear the outcry of his people- and then would come down to save them from violence as it was the case in Egypt and Canaan.34 But the context of Genesis provokes questions: whose

and then would come down to save them from violence as it was the case in Egypt and Canaan.34 But the context of Genesis provokes questions: whose  is it? Whose interests is Yahweh coming down to protect? That Yahweh-the author's God came down to save "other" people who do detestable and evil things is incongruent with the author's ideology.

is it? Whose interests is Yahweh coming down to protect? That Yahweh-the author's God came down to save "other" people who do detestable and evil things is incongruent with the author's ideology.

therefore presents an ambiguity in relation to the perpetrators and victims of violence. Likewise

therefore presents an ambiguity in relation to the perpetrators and victims of violence. Likewise

would suggest the "outcry of Sodom and Gomorrah" rather than "the outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah."35 Reading this phrase in respect to vv. 18 and 19 would suggest that, Abraham, whom Yahweh has chosen "to become a great and powerful nation" and to direct his children and his household according to the ways of the LORD-doing right and just, is the one whom and whose interests Yahweh who is "coming down" is protecting. In other words, the narrative demonstrates that Sodom and Gomorrah is to be removed from the face of the earth and be replaced by the great nation that will decend from Abraham. It is not surprising that when Judah (and Israel) fails to live to the expectations of these Abrahamic-great-nation ideals, Ezekiel the Prophet rebukes and describes them as worse than their young sister Sodom (See Ezek 16:44-48).

would suggest the "outcry of Sodom and Gomorrah" rather than "the outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah."35 Reading this phrase in respect to vv. 18 and 19 would suggest that, Abraham, whom Yahweh has chosen "to become a great and powerful nation" and to direct his children and his household according to the ways of the LORD-doing right and just, is the one whom and whose interests Yahweh who is "coming down" is protecting. In other words, the narrative demonstrates that Sodom and Gomorrah is to be removed from the face of the earth and be replaced by the great nation that will decend from Abraham. It is not surprising that when Judah (and Israel) fails to live to the expectations of these Abrahamic-great-nation ideals, Ezekiel the Prophet rebukes and describes them as worse than their young sister Sodom (See Ezek 16:44-48).

The chapter ends without clarity on the subjects of  .Abraham does not make any outcry to God and he is at the same time not jubilant about Sodom's imminent destruction.36 The entire population of Sodom is ideologically depicted as morally rotten, with hardly any ten righteous people-on whose basis the cities can be spared. This is apparently set to legitimise the events of ch. 19.

.Abraham does not make any outcry to God and he is at the same time not jubilant about Sodom's imminent destruction.36 The entire population of Sodom is ideologically depicted as morally rotten, with hardly any ten righteous people-on whose basis the cities can be spared. This is apparently set to legitimise the events of ch. 19.

5 Genesis 19

The angels arrive in Sodom in the evening. Lot is strategically situated at the gateway of the city of Sodom to receive the visitors.37 He bows down to the ground in humility, and implores the men to spend a night in his home (while the rest of the population is portrayed espying to know where they are going).

Verse 4 presents a scene where  of Sodom "both young and old" (

of Sodom "both young and old" ( )surround Lot's home demanding to know the guests in Lot's house. In the HB,

)surround Lot's home demanding to know the guests in Lot's house. In the HB,  may refer to the totality of the population or a distinct social group that always influences political events in ancient kingdoms. In 2 Kings, they intervened after assassination of Amon (21:23-24) and death of Josiah (23:30) to elevate a proper Davidic descendant to the throne. It is also used to mean the army (Num 31:32, Josh 10:7; 11:7, 1 Sam 11:11, 1 Kgs 20:10).38 The construction

may refer to the totality of the population or a distinct social group that always influences political events in ancient kingdoms. In 2 Kings, they intervened after assassination of Amon (21:23-24) and death of Josiah (23:30) to elevate a proper Davidic descendant to the throne. It is also used to mean the army (Num 31:32, Josh 10:7; 11:7, 1 Sam 11:11, 1 Kgs 20:10).38 The construction  denotes the entire population of Sodom, young and old, men and women

denotes the entire population of Sodom, young and old, men and women  (young), and in relation to Gen 24:14, denotes both sexes.

(young), and in relation to Gen 24:14, denotes both sexes.

Verses 5-9 present a problem in relation to the usage of  .From the root

.From the root  (to know),

(to know),  is in cohortative mood,39 which expresses a wish, or a request for permission, that one should be allowed to do something. In the 1st person plural form, as in this case, the cohortatives include summons to others to help in doing something.

is in cohortative mood,39 which expresses a wish, or a request for permission, that one should be allowed to do something. In the 1st person plural form, as in this case, the cohortatives include summons to others to help in doing something.

In most translations, this verb has been given a sexual meaning that implicates  in attempted homosexual rape of Lot's guests. Both rape and homosexuality in the ideological context of the OT are illicit sexual practices. Though it is true that sexual relationships in the HB are associated with this verb root (

in attempted homosexual rape of Lot's guests. Both rape and homosexuality in the ideological context of the OT are illicit sexual practices. Though it is true that sexual relationships in the HB are associated with this verb root ( ), it is only in the consensual heterosexual relationship that we find

), it is only in the consensual heterosexual relationship that we find  used as in the case of Gen 4:1 and 1 Kgs 1:4. Non-consensual and other sexual intercourse that include homosexuality, rape, bestiality etcetera are associated with the verbal root

used as in the case of Gen 4:1 and 1 Kgs 1:4. Non-consensual and other sexual intercourse that include homosexuality, rape, bestiality etcetera are associated with the verbal root  as in Exod 22:15; Lev 18 and 20; Deut 22:23, 25, 28-29; 2 Sam 13:14, etcetera.40There are no parallel texts in the HB that attest that homosexuality is rendered with verb

as in Exod 22:15; Lev 18 and 20; Deut 22:23, 25, 28-29; 2 Sam 13:14, etcetera.40There are no parallel texts in the HB that attest that homosexuality is rendered with verb  .41

.41

However, this chapter is sexualised when Lot offers his daughters to

in protection of his guests. The daughters are presented as having not known any man (

in protection of his guests. The daughters are presented as having not known any man ( ) before. This has been commentated upon, and like the man of Judg 19, Lot is personified evoking the hospitality motif of his context where "protection of strangers in one's house took precedence over the love of one's children."42

) before. This has been commentated upon, and like the man of Judg 19, Lot is personified evoking the hospitality motif of his context where "protection of strangers in one's house took precedence over the love of one's children."42

Blindness ( )was a deep grounded concept in ANE civilisations.43In relation to Gen 19:11, blindness falls in the same ideological landscape and niche with the ideals of divine choice and divine judgement and indictment. In the rest of the HB, Yahweh would afflict those who assail against his chosen ones with blindness (2 Kgs 6:18-20, Pss, 23 and Zech 12:4). Blindness was a curse in the ANE thought.44 For instance, in the Sumerian law codes, blindness was among the curses that would befall an individual who erased or impersonated the king's inscription: "May his city be despised by the god Enlil; May the young men of his city be blind."45 In Esarhaddon's treaties, blindness was also evoked as one the curse, namely to the one who alters or destroys the document of the treaty, "May it be dark in your eyes, walk in darkness."46Blindness was also common in ANE warfare. Prisoners of war were blinded. In Judgl6:21, Samson is blinded by the Philistines, while in 2 Kgs 25:7 King Zedekiah is blinded by the Babylonians. In the Hittite documents, the captives of Tapikka and Šapinuwa were blinded before being made to work in mills.47Excerpts from Tiglath Pilaster's documents contain blindness as a punishment that would be inflicted on Mati'el, ruler of Arpad if he breaks the treaty.48 Blindness, in other ancient cultures was used as a pejorative term for disgrace49or weakness.50

)was a deep grounded concept in ANE civilisations.43In relation to Gen 19:11, blindness falls in the same ideological landscape and niche with the ideals of divine choice and divine judgement and indictment. In the rest of the HB, Yahweh would afflict those who assail against his chosen ones with blindness (2 Kgs 6:18-20, Pss, 23 and Zech 12:4). Blindness was a curse in the ANE thought.44 For instance, in the Sumerian law codes, blindness was among the curses that would befall an individual who erased or impersonated the king's inscription: "May his city be despised by the god Enlil; May the young men of his city be blind."45 In Esarhaddon's treaties, blindness was also evoked as one the curse, namely to the one who alters or destroys the document of the treaty, "May it be dark in your eyes, walk in darkness."46Blindness was also common in ANE warfare. Prisoners of war were blinded. In Judgl6:21, Samson is blinded by the Philistines, while in 2 Kgs 25:7 King Zedekiah is blinded by the Babylonians. In the Hittite documents, the captives of Tapikka and Šapinuwa were blinded before being made to work in mills.47Excerpts from Tiglath Pilaster's documents contain blindness as a punishment that would be inflicted on Mati'el, ruler of Arpad if he breaks the treaty.48 Blindness, in other ancient cultures was used as a pejorative term for disgrace49or weakness.50

The blindness of  may serve to amplify the curse and indictment over Sodom, purposely to protect the interests of Yahweh's chosen one. In his promises to Abraham, Yahweh is to bless those who bless Abraham and curse those who curse Abraham. If blindness is used in a pejorative sense, it then implies the feebleness in

may serve to amplify the curse and indictment over Sodom, purposely to protect the interests of Yahweh's chosen one. In his promises to Abraham, Yahweh is to bless those who bless Abraham and curse those who curse Abraham. If blindness is used in a pejorative sense, it then implies the feebleness in  of Sodom in as far as defending their city, or how their attempt to defend their territory was futile in the face of the enemy power. In fact, the lxx uses the verb παρελύθησαν, from the root παραλύω, which means to weaken, to disable, to paralyse.

of Sodom in as far as defending their city, or how their attempt to defend their territory was futile in the face of the enemy power. In fact, the lxx uses the verb παρελύθησαν, from the root παραλύω, which means to weaken, to disable, to paralyse.

E DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In my hypothesis I stated that Sodom and Gomorrah are victims of military arson and ideological denigration. Stated differently, Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed by military arson and ideological artillery. Though the remains of these cities were dismembered, scattered (and embroidered in ideological casket), the created story as preserved in the Bible leaves many questions unanswered. It takes careful scrutiny and intuitive reading through the lines of the Bible to notice that the incoherent story of Sodom and Gomorrah-summed up in Gen 19, is heavily garnished with the ideological interests and inconsistencies that point to the fact that there is an untold story about the demise of Sodom and Gomorrah. As a result, the iconography of Sodom and Gomorrah remains ambiguous in the Bible literary art of the Bible and a site of numerous inconclusive scholarly visits.

The case for or against homosexuality has been dealt with in many writings.51 Many writings have also pointed out the ideology of the narratives but have heavily operated from the sexual frontlines either as defenders or offenders of homosexuality. But as noted earlier, there has been an effort to view Sodom and Gomorrah from the political perspective of the time. Great scholarly works are devoted to theological, historical and archaeological analysis with varying degrees of results and opinions.

To prove the hypothesis it was necessary to glean through the textual fields of Genesis for clues. In Gen 13, Sodom and Gomorrah were distinct kingdoms, naturally gifted with water and fertile soils. Its splendour is equated to the Garden of Eden or Egypt. The location of Sodom and Gomorrah attracted the attention of foreigners like Lot who went to live there, and others like Abraham, apparently as distant admirers. They were wealthy as well, as attested in ch. 14. In fact, Ezekiel 16:49 suggest that Sodom was reminiscent of or exceeded Israel during the prophetic days of Amos (see Amos 3:15 and 6:4; 6:6).52

According to ch. 14, Sodom and Gomorrah was a political hotspot: the king of Elam53 subjected the region to vassalage, apparently collecting tributes from the five kingdoms of the Jordan plains. Following the rebellion, Elam with her allies waged a fierce war against the Jordan States in the valley of Sidiim. The character Abraham is constructed as the agency to Sodom's recovery of looted wealth and captives of war. But Abraham is in an altercation with the king of Sodom over looted property and the people who had been rescued from Elam. The chapter ends without a clear position about the relationship between Abraham and Sodom. Besides, there are no guarantees for the security of Sodom and Gomorrah from any further attacks, which creates a possibility that the Jordan valley states remained vulnerable to external attacks, and the people who are anxious and conscious about their territorial future.

As mentioned above, biblical accounts accounts on Abraham have always been evaluated as homo theologicus rather than homo politicus. In this chapter, it is clear that the military situation triangulates between Elam and her allies, Sodom and her allies and the individual character-Abraham. The character Abraham is not constructed as heading a kingdom or armies or having allies as Elam and Sodom. But as Elam with her three allies subdues the Pentapolis-Sodom and Gomorrah. Abraham also subdues Elam and her three allies in turn. In the hierarchy of military superiority, Abraham is placed on top of the chart as militarily superior to Elam and her allies and exceedingly to Sodom and her allies. In effect, Abraham is the superpower to reckon with in this geopolitical context.

Though his influential status is dimmed in the biblical narratives, Abraham seems not to have been an ordinary wandering shepherd character but a man of distinguished socio-economic stature in his geographical context.54 Ur and Harran where Abraham moved from were two of the three famous trading centres in ancient Mesopotamia. Indeed, Albright has observed that the name Harran means the Caravan city, and thus associates Abraham with lucrative extensive caravan trade between Palestine and Egypt.55 In the same way, Free and Vos opine that Abraham was a merchant prince, intimating that he wielded political and economic powers in his region. They state that Abraham's socio-economic and political affluence and influence are accentuated by his ability to purchase Sarah's grave at 400 shekels of silver and visiting Egypt, dealing with the Hittites, making treaties with the Philistines, and making alliances with the Amorites.56 In the same way, Freedman thinks "... Abraham was like the kings with whom he associated in business, war, and liturgy: he was a warrior-chieftain, and so were they; he was a merchant prince, and so were they."57 Freeman suggests that Abraham's environment was the land of kings, and Abraham in that respect had a kingly stature and kings as his contemporaries.58

As a foreigner who settled in Canaan, Abraham could have organised the Canaanites into a sort of political organisation. Histories of the ANE indicate that it was common for a territory to be occupied by foreigners who would rule over or drive the original inhabitants away. Ancient Egypt was for instance invaded by and ruled by the Hyksos.59 It remains a plausible possibility that Abraham of Genesis 14 wielded power and influence as a warrior with a kingly stature, had enemies (see v. 20) and allies (v. 13) as per the maxims of the ANE. Worth mentioning is that the political organisation of these Canaanite and Jordan states seemed either decentralised or centralised under kings to whom chiefs administering different regions, were answerable. It is in these perspectives that one can understand the Gen 14:10 story of the undisclosed number of kings of Sodom and Gomorrah-some of whom perished in the tar pits while others fled in the hills. Amidst such political circumstances, any altercation between Abraham and Sodom would create tension and anxiety on either side that could inevitably call for military action.

The plot is interrupted by chs. 15 to 17-without mentioning Sodom or any of the Jordan states. Chapter 15 opens with an encouragement to Abraham (Don't be afraid) as ch. 17's ending concretises Abraham's relationship with Yahweh-his God with a covenant. The agreement is elaborate with details that set Abraham and his descendants apart as the chosen ones over other nations.

Sodom and Gomorrah appear back into the story in ch. 18. In this chapter, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is revealed. The two messengers against whom the destruction is attributed first visited Abraham and were entertained in his house. The narrators have however laboured to exonerate Abraham from the plot to destroy Sodom by attaching intercessory attributes to his interaction with the two men. Accordingly, the narrator would probably argue, Sodom is destroyed due to her people's own evil. Key is the fact that from Abraham, the strange men went to Lot's home. Lot, Abraham's nephew is situated in the city of Sodom to welcome the angel-men. The spectacle of strangers in this politically volatile region must have attracted concern of  .

.

Strangers in ancient history were subject to local security verification and protocol. The two men who invaded Sodom did not present their credentials to the local authority for the appropriate security measures to be accorded to them. It was normative for the foreigners to present themselves before the local authority for the appropriate protection to be granted. In Gen 26, Isaac presents himself before Abimelek king of the Philistines (cf. Gen 12 in which Abraham goes to Egypt and is before the Egyptian authorities). They were a spectacle of suspicion and insecurity and more so, being in the house of another foreigner-Lot.

Against this background, Gen 19, especially in relation to the over sexualised verb  should be read differently. The root

should be read differently. The root  denotes one basic aspect-to know or have knowledge of something or somebody you didn't know before. Brown-Driver-Briggs as also Strong's Hebrew Lexicons attach other meanings to this basic aspect as "perceive," "find out and discern," "distinguish," "experience," "recognise," "have knowledge," "be wise," among others. In Gen 29:5 and Exod 1:8, this root is used in the context of having knowledge or forming acquaintances with somebody. Reading

denotes one basic aspect-to know or have knowledge of something or somebody you didn't know before. Brown-Driver-Briggs as also Strong's Hebrew Lexicons attach other meanings to this basic aspect as "perceive," "find out and discern," "distinguish," "experience," "recognise," "have knowledge," "be wise," among others. In Gen 29:5 and Exod 1:8, this root is used in the context of having knowledge or forming acquaintances with somebody. Reading  in this respect is logical, given that the people of Sodom had good reasons to know the identities and mission of the foreigners in their territory.

in this respect is logical, given that the people of Sodom had good reasons to know the identities and mission of the foreigners in their territory.

Migrations and movements of foreigners were a regular practice in many ANE societies. These foreigners included refugees, captives, merchants, travellers and diplomats among others. Ancient Mesopotamian and Hittite documents60 reveal that there were laws and regulations that governed various categories of people sojourning through or staying in foreign territories. Many ANE societies had functional intelligence systems of detecting foreigners and their motives or mission in a foreign territory. Invaders who were suspected of political and military espionage or conquest were treated with disapproval and contempt,61 while other groups like messengers, merchants, transit travellers, refugees and captives of war were treated differently depending on the existing customs.62

If we read the messengers of Gen 19 alongside Josh 2 (see also Num 13-14); we are confronted with the motif of spies in the ancient military and political intelligence. Spy intelligence was reliably used in ANE political imperialism. In Mesopotamia, spies were called scouts, or eyes, and were to check out what was going on in rival kingdoms. This is evident in the correspondences discovered by archaeologists at Mari.63 Dubovsky, in his book on Neo-Assyrian intelligence services presents evidence of intelligence collection in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and the spies were very useful.64 Spies usually infiltrated the enemy force's territory, and in reconnoitering a city, the spies "would be interested in assessing the enemies' defenses, food and water supply, number of fighting men and general preparedness for attack or siege."65In the documents from Mari, an allied force of 2000 Mariote and 3000 Babylonia troops went on campaign against Eshnuna, but were defeated because a spy had revealed their plans to the enemy.66

Against this background, the people of Sodom could not leave anything to chances. They should have demanded to know the identities and mission of the strangers in their territory. But the strangers who are concealing their identities, and hiding in the home of another foreigner living in the heart of Sodom, triggered off desperate actions from the local inhabitants; actions that were inflicted on spies and other military enemies. However, it has to be noted that sexual violence, including sexual rape against men was part of the weaponry in armed conflicts of the ancient world. Militaries of ancient states like Persia, Egypt, and Amalekites67 sexually raped their military enemies as a way of humiliating them. In the context of Gen 19, the writer could be playing over the double meaning in the root  If the so-called angel men were spies and a political and military threat, homosexual rape was a possibility as a way of humiliating them. Thus, if Sodom would rape the invading enemies, the act of homosexuality was a reaction rather than an action of orientation.

If the so-called angel men were spies and a political and military threat, homosexual rape was a possibility as a way of humiliating them. Thus, if Sodom would rape the invading enemies, the act of homosexuality was a reaction rather than an action of orientation.

In our days, a committee of inquiry would be formed to investigate the fire that razed Sodom and Gomorrah. The detectives would rummage the textual fields of the OT for any relevant information about Sodom and Gomorrah in order to assess the circumstances that caused the mystical fire. Much of the information would be concealed for some reasons, but what would be retold about the demise of these nations albeit in a feigned story, is the mention of some personalities. Each of these characters would appear to be investigated in the case of Sodom and Gomorrah's fire. Each of these characters' criminal records would be brought to table; their relationships and interactions with Sodom and Gomorrah would also be assessed. Evidence collected from the textual field would be presented against each character in assessing the merits of the case. The mode of destruction would also be examined in relation to other crimes against humanity in the contemporary political context of Sodom and Gomorrah. And then the conclusions would be made. Unfortunately, this investigation was being carried out posthumously; no arrests would be made by the CIDs.

In this study, the personalities named in Sodom and Gomorrah's demise are: the Elamite king and the allies, Abraham, the two messengers and Lot. Each of these characters has to be assessed in the merits of this case as follows:

Elam: though there is no clue in the HB that Elam revisited Sodom and Gomorrah, reading Elam's war histories68 from elsewhere, suggest that the Elamite kings were resilient fighters in the ANE and the biblical defeat by Abraham could not be tantamount to Elam's disinterest in Sodom. Besides, we read from other histories that Elam had been a notorious enemy of Ur- Abraham's birthplace, especially after 2004 B.C.E. when Elam in alliance with Susa invaded Ur and took its king-Ibbi Sin into captivity.69 Historians have estimated Abraham's entry into Canaan to the year 2000 B.C.E.,70 four years after his homeland was harassed by Elam. This could be the pointer to Abraham's decision to fight against Elam in Gen 14, and why, in the Melchizedek blessings, Elam could be identified as Abraham's enemies (Gen 14:20). There is a possibility that, if Elam overran Abraham and reinvaded Sodom and Gomorrah and destroyed the cities, the writer would craft a story that condemns Sodom and Gomorrah as responsible for their own destruction.71This would then serve as an appropriate point where the military actions of Elam meet the ideological artisanry of the writer. The angel-men would therefore be fictitious characters in the narrative, and the writer, aware of Lot's relationship with Abraham would create an appropriate situation in the narrative through which Lot is to escape.

Abraham: As discussed above, Abraham exhibits great interests in Sodom and Gomorrah. The texts, especially ch. 14 are vague about the postwar relationship between Abraham and Sodom. There can be many reasons as to why Abraham would choose to war against Sodom. One can argue that as a trade merchant, probably carrying out caravan trade in Palestine, Abraham could have encountered hostility from the people of Sodom and Gomorrah; the reason why these two states are associated with violence.72 Destroying these states would therefore be a measure to guarantee free passage of his trade. As noted above, Abraham and the king of Sodom are in conflict over the recovered loot and people, which are in the possession of Abraham and his men. Both the wealth and the people were of important social and economic value to Abraham. As a trader, the recovered loot, probably of livestock and other valuables would be sold to trade merchants. The people of Sodom would be sold as slaves, and others retained as domestic slaves and servants. After all, Abraham seemed interested in numbers, and by having many people under his control, he would be famous. We read in Gen 14:1 that he had already "318 trained men born in his household," and there is no excuse of not having more.

Abraham is also a strong warrior. He had fought Elam and her allies and could equally crash Sodom. If the relationship between Sodom and Abraham was bad, and the latter was anxious about his survival and future, then Yahweh's encouragement in the following ch. 15:2 is in good context, in which case, we could be singing the fall of Sodom in reminiscent of the fall of Babylon (See Isa 47, cf. Jer 50).

Furthermore, the constant attempts to exonerate Abraham from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah even where it is not necessary raise suspicions. The narrator invests much effort in making his readers of the second half of ch. 18 perceive Sodom's destruction as the matter of divine decision and Sodom's own self impiety and abhorrence.

The two men who invaded Sodom came from Abraham's home, and ended in Lot's house. They could have been Abraham's spies that were using Lot's geographical location to their advantage. This being the case, it is possible that the people of Sodom captured and humiliated the spies and Lot most likely escaped to Zoar (where he was further ejected). The destruction of Sodom by the flames could have been a later development by Abraham and his fighter in revenge.

The third possibility is that of Abraham's solidarity with foreign country. The two angels-men could have come from a foreign state, allied to Abraham. The men are described with human attributes that enjoy relishing in human hospitality. In Abraham's house, the narrator intentionally mutes details of the conversations between Abraham and his visitors, and gives priority to aspects of hospitality. These men could have been spies from a neighbouring state that wanted a foothold in this Garden of God-The Jordan valley. From the muted conversation, we suspect the men asking Abraham about the direction of Sodom, about the military strength, strategic points and source of supplies; Abraham responds by informing them that he has a nephew living right in the heart of the city of Sodom who would be a valuable resource for military intelligence.

Recent archaeological activities have identified ash and burnt materials in the sites that are thought to be "Sodom and Gomorrah." This agrees with the Gen 19 narrative that Sodom and Gomorrah were burnt by fire. These burnt materials can be associated with war, as indeed ancient militaries practiced scorched-earth policy in which towns, settlements and fields were set on fire. In Sargon's description of his conquest of the lands of Manneans and Nairi, he brags of scaling the walls of their cities and then setting "fire on their beautiful dwellings, and made the smoke thereof rise and cover the face of heaven like a storm . . ."73 Equally, in neo-Assyrian materials, Tukulti-Ninrta II (890-844) in his attack against the land of Mushki boasts of burning down cities with fire and crops of the field.74 If any of the enemies of Sodom torch down Sodom and Gomorrah, with the combustible materials in the vicinities of the Dead Sea, the flames in the burning of Sodom inevitably reached the sky and remained a classic and in the ideological worldview of the HB, the fire must have been from the finger of the God.

The arguments of this paper wishes to convince that the "Sodom and Gomorrah" texts suggest that the Jordan valley cities were victims of military and political incursions of foreign imperialism of the time. Their resistance to foreign enemies resulted into the legendary destruction. The appearance of the angel-men was a spectacle of suspicion in Sodom. They were strangers whose mission in Sodom was not defined to the authorities. This inevitably called for  to investigate. The controversy that clouds the verb

to investigate. The controversy that clouds the verb  should not persist if the verb is understood in these terms. Read in its basic sense as to know (with the quest to acquaintance), the

should not persist if the verb is understood in these terms. Read in its basic sense as to know (with the quest to acquaintance), the  had the duty to know the strangers who have infiltrated their territory. The reactions of the strangers and their host suggest that they were a military threat, apparently spying for the enemy. Spies were to be treated as per the custom of the ANE that included homosexual rape as a means of feminising and humiliating the enemy. Nevertheless, there are no parallel texts that suggest that homosexuality is associated with the root

had the duty to know the strangers who have infiltrated their territory. The reactions of the strangers and their host suggest that they were a military threat, apparently spying for the enemy. Spies were to be treated as per the custom of the ANE that included homosexual rape as a means of feminising and humiliating the enemy. Nevertheless, there are no parallel texts that suggest that homosexuality is associated with the root  . In this case, to argue the case for lack of hospitality in Sodom is not only being ungrateful for the reception given to strangers like Lot and his family, but also anticipating naïve hospitality in the face of military threats. The caricature given to the story of Sodom and Gomorrah in the HB is purposefully nourishing the ideology of divine choice vis-à-vis divine indictment and destruction.

. In this case, to argue the case for lack of hospitality in Sodom is not only being ungrateful for the reception given to strangers like Lot and his family, but also anticipating naïve hospitality in the face of military threats. The caricature given to the story of Sodom and Gomorrah in the HB is purposefully nourishing the ideology of divine choice vis-à-vis divine indictment and destruction.

This paper does not assume to be an exhaustive investigation or study of Sodom and Gomorrah, but a contribution to the ongoing scholarly visits and comments in the visitors' book at the necropolises. It is thus hoped that it will inspire further creative studies on both "Sodom and Gomorrah" or other similar topics in biblical studies.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abel, Frank. "Sodom Revisited." The Bible Magazine 10/1. No Pages. Cited 18 July 2015. Online: http://www.biblemagazine.com/magazine/vol-10/issue-1/sodom.html. [ Links ]

Albright, William F. "The Historical Background of Genesis XIV." Journal of the Society of Oriental Research 10 (1926): 231-69. [ Links ]

____. Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan. Garden City: Doubleday, 1968. [ Links ]

Bailey, Derrick Sherwin. Homosexuality and the Western Christian Tradition. London: Longmans, 1955. [ Links ]

Banks, Diane. Writing the History of Israel. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies 438. London: T&T, 2006. [ Links ]

Beekman, Gary. "Foreigners in the Ancient near East." Journal of the American Oriental Society 133/2 (2013): 203-15. [ Links ]

Bell, Daniel. "Ideology." Page 414 in The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought. Edited by Alan Bullock, Stephen Trombley and Oliver Stallybrass. London: HarperCollins, 2000. [ Links ]

Bennett, Georgette. "Sodom and Gomorrah Revisited." No Pages. Cited 19 July 2015. Online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/georgette-bennett-phd/sodom-and-gomorrah-revisited_b_2624684.html. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. The Pentateuch. London: SCM Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Brawley, Robert L. Biblical Ethics and Homosexuality: Listening to Scripture. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Bruegemann, Walter. Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012. [ Links ]

Carter, Elizabeth and Matthew W. Stolper. Elam: Surveys of Political History and Archaeology. London: University of California Press, 1984. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. A. Interested Parties: The Ideology of Writers and Readers of the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Collins, Steven. "If You Thought You Knew the Location of Sodom and Gomorrah... Think Again." Biblical Research Bulletin 7/4 (2007): 6 pages. Cited 19 July 2015. Online: http://www.biblicalresearchbulletin.com/uploads/BRB-2007-4-Collins-Location_Sodom.pdf. [ Links ]

____. "The Geography of Sodom and Zoar: Reality Demolishes W. Schlegel's Attacks against a Northern Sodom." Biblical Research Bulletin 13/2 (2013): 14 pages. Cited 20 July 2015. Online: http://www.biblicalresearchbulletin.com/uploads/BRB-2013-2-Collins_Answers_Schlegel.pdf. [ Links ]

Curzer, Howard J. "Spies and Lies: Faithful, Courageous Israelites and Truthful Spies." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 35/2 (2010): 187-95. [ Links ]

Dubovsky, Peter. Hezekiah and the Assyrian Spies: Reconstruction of the Neo-Assyrian Intelligence Sendees and Its Significance for 2 Kings 18-19. Rome:Biblical Institute Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Exum, Cheryl J. Fragmented Women: Feminist (Sub)Versions of Biblical Narratives. Sheffield: JSOT, 1993. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. S. J. The Genesis Apocryphon of Qumran Cave I: A Commentary. Biblica Et Orientalia. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1966. [ Links ]

____. "The Inscriptions of Bar-Ga yah and Mati el from Sefire." Page 213-217 in Context of Scripture. Edited by William H. Hallo. Leiden: Brill, 1997. [ Links ]

Fleishman, Joseph. "On the Significance of a Name Change and Circumcision in Genesis 17'." Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 28 (2001): 19-32. [ Links ]

Free, Joseph P. and Howard F. Vos. Archaeology and Bible History. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992. [ Links ]

Freedman, David N. "The Real Story of the Ebla Tablets: Ebla and the Cities of the Plain." Biblical Archaeologist 41/4(1978): 143-64. [ Links ]

Gesenius, Wilhelm, Emil Kautzsch and Arthur Ε. Cowley. Gesenius ' Hebrew Grammar. 2nd English ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910. [ Links ]

Glissmann, Volker. "Genesis 14: A Diaspora Novella." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 34/1 (2009): 33-45. [ Links ]

Gold, John R. and Margaret M. Gold. "The History of Events: Ideology and Historiography." Pages 119-28 in Routledge Handbook of Event Studies. Edited by Stephen Page and Joanne Connell. London: Routledge, 2011. [ Links ]

Gordon, Cyrus. "Abraham and the Merchants of Ura." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 17 (1985): 28-31. [ Links ]

Hamblin, William J. Warfare in the Ancient near East to 1600 B.C.: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge, 2006. [ Links ]

Hasel, Michael G. "Assyrian Military Practices and Deuteronomy's Laws of Warfare." Pages 67-82 in Writing and Reading War: Rhetoric, Gender, and Ethics in Biblical and Modern Contexts. Edited by Brad E. Kelle and Frank R. Ames. Atlanta: The Society of Biblical Literature, 2008. [ Links ]

Hoerth, Albert J. Archaeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 1998. [ Links ]

Hoffner, Harry A. "The Disabled and Infirm in Hittite Society." Pages 84-90 in Ereyz- Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. Edited by Hayim Tadmor and Miriam Tadmor. Jerusalem: IES, 2003. [ Links ]

Howard, David M. "Sodom and Gomorrah Revisited." Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 27/4(1984): 385-400. [ Links ]

Kelle, Brad E. and Frank Ritchel Ames, eds. Writing and Reading War: Rhetoric, Gender, and Ethics in Biblical and Modern Contexts. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008. [ Links ]

Lowery, Richard H. The Reforming Kings: Cults and Society in First Temple Judah. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series 120. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Maraqten, Mohammed. "Dangerous Trade Routes: On the Plundering of Caravans in the Pre-Islamic near East." Aram Periodicals 8/1 (1996): 213-36. [ Links ]

McAllister, Ray. "Theology of Blindness in the Hebrew Scriptures." Ph.D. diss., Andrews University, 2010. 402 pages. Cited 14 October 2015. Online: http://digitaleommons.andrews.edu/cgi/vieweontent.cgi?article=1088&context=dissertations. [ Links ]

McDonald, Thomas L. "Bread in the Old Testament." No Pages. Cited 1 September 2015. Online : http://www.patheos.com/blogs/godandthemachine/2012/12/bread-in-the-old-testament/. [ Links ]

____. "Wine in the Old Testament." No Pages. Cited 1 September 2015. Online: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/godandthemachine/2012/12/wine-in-the-old-testament/. [ Links ]

Miller, J. Maxwell and John H. Hayes. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. 2nd ed. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. London: University of Chicago Press, 1986. [ Links ]

Neill, James. The Origin and Role of Same-Sex Relations in Human Societies. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2009. [ Links ]

Noort, Edward and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar. Sodom's Sin: Genesis 18-19 and Its Interpretation. Leiden: Brill, 2004. [ Links ]

Olson, Craig. "Which Site Is Sodom? A Comparison of Bab Edh-Dhra and Tall El- Hammam." Biblical Research Bulletin 14/1 (2014): 17 pages. Cited 19 July 2015. Online: http://www.biblicalresearchbulletin.com/uploads/BRB-2014-l-01son_on_Sodom.pdf. [ Links ]

Person, Raymond F. The Deuteronomistic History and the Book of Chronicles: Scribal Works in an Oral World. Society of Biblical Literature Ancient Israel and Its Literature 6. Atlanta, Ga.: Society of Biblical Literature, 2010. [ Links ]

Podany, Amanda. Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient near East. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Potts, Daniel T. A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient near East. 2vols. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. [ Links ]

Rast, Walter Ε. and R. Thomas Schaub. "Survey of the Southearstern Plain of the Dead Sea." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 19 (1974): 175-85. [ Links ]

Rickett, Dan. "Rethinking the Place and Purpose of Genesis 13." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36/1 (2011): 31-53. [ Links ]

Ritner, Robert K. "The Turin Judicial Papyrus (3.8)." Context of Scripture online (2000). No Pages. Edited by William W. Hallo. Leiden: Brill. Cited 20 August 2015. Online: http://www.brillonline.nl/entries/context-of-scripture/the-turin-judicial-papyrus-38-aCOSB_3_8. [ Links ]

Roth, Martha. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars, 1995. [ Links ]

Shea, William H. "Chronology of the Old Testament." Pages 244-48 in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Edited by David N. Freedman and Allen C. Myers. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2000. [ Links ]

Sheldon, Rose Mary. "Spying in Mesopotamia." CIA Historical Review Program 33 (1989): 7-12. [ Links ]

Sivakumaran, Sandesh. "Sexual Violence against Men in Armed Conflicts." The European Journal of International Law 18/2 (2007): 253-76. [ Links ]

Soggin, J. Alberto. An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Brescia: SCM Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Swanson, Dennis M. "Caravan." Page 223 in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Edited by David N. Freedman and Allen C. Myers. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. [ Links ]

Thompson, Thomas L. "The Joseph and Moses Narratives." Pages 149-213 in Israelite and Judean History. Edited by John H. Hayes and J. Maxwell Miller. Philedelphia: Westminster Press, 1977. [ Links ]

____. The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives. Harrisburg: Trinity, 2002. [ Links ]

Tormey, Judith F. and Alan Tormey. "Arts and Ambiguity." Leornardo 16/3 (1983): 183-87. [ Links ]

Van Seters, John. Abraham in History and Tradition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975. [ Links ]

Wabyanga, Robert K. "Athaliah of Judah (2 Kings 11): A Political Anomaly or an Ideological Victim?" Pages 139-52 in Looking through A Glass Bible: Postdisciplinary Biblical Interpretations from the Glasgow School. Edited by A.K.M Adam and Samuel Tongue. Leiden: Brill, 2014. [ Links ]

Wallace, Daniel B. Greek Grammar Beyond the Basic: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 1996. [ Links ]

Walton, John H., Victor H. Matthews and Mark W. Chavalas. The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament. Westmont: InterVarsity Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, Moshe. Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972. [ Links ]

____. The Promise of the Land: The Inheritance of the Land of Canaan by the Israelites. The Taubman Lectures in Jewish Studies 3. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Wiseman, Donald J. The Vassal-Treaties of Esarddon. London: British School of Archeology in Irag, 1958. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Robert Kuloba Wabyanga

Biblical Studies in the Department of Religious Studies

Kyambogo University

Kampala, Uganda.

Email:robert_kuloba@yahoo.com

Article submitted: 4 September 2015

Accepted: 19 October 2015

1 See mainly the works of Albert J. Hoerth, Archaeology and the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 1998), 98.; Craig Olson, "Which Site Is Sodom? A Comparison of Bab Edh-Dhra and Tall El-Hammam," BRB 14/1 (2014): 17 pages [cited 19 July 2015]. Online: http://www.biblicalresearchbulletin.com/uploads/BRB-2014-l-Olson_on_Sodom.pdf; Steven Collins, "If You Thought You Knew the Location of Sodom and Gomorrah...Think Again," BRB 7/4 (2007): 6 pages [cited 19 July 2015]. Online: http://www.biblicalresearchbulletin.com/uploads/BRB-2007-4-Collins-Location_Sodom.pdf; Steven Collins, "Lhe Geography of Sodom and Zoar: Reality Demolishes W. Schlegel's Attacks against a Northern Sodom," BRB 13/2 (2013): 14 pages [cited 20 July 2015]. Online: http://www.biblicalresearchbulletin.com/uploads/BRB-2013-2-Collins_Answers_Schlegel.pdf.

2 See J. Alberto Soggin, An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah (Brescia: SCM Press, 1993), 100; J. Maxwell Miller and John H. Hayes, A History of Ancient Israel and Judah (2nd ed.; Ix>uisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), 60; William F. Albright, "Lhe Historical Background of Genesis XIV," JSOR 10 (1926): 231-69; Walter E. Rast and R. Lhomas Schaub, "Survey of the Southearstern Plain of the Dead Sea," ADAJ 19 (1974): 175-85.

3 David M. Howard, "Sodom and Gomorrah Revisited," JETS 27/4 (1984): 385-400; Georgette Bennett, "Sodom and Gomorrah Revisited," n.p. [cited 19 July 2015]. Online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/georgette-bennett-phd/sodom-and-gomorrah-revisited_b_2624684.html; Frank Abel, "Sodom Revisited," BMag 10/1: n.p. [cited 18 July 2015]. Online: http://www.biblemagazine.com/magazine/vol-10/issue-1/sodom.html.

4 Daniel Bell, "Ideology," in The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (ed. Alan Bullock, Stephen Trombley and Oliver Stallybrass; London: HarperCollins, 2000), 414.

5 Thomas W. J Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (London: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

6 John R. Gold and Margaret M. Gold, "The History of Events: Ideology and Historiography," in Routledge Handbook of Event Studies (ed. Stephen Page and Joanne Connell; London: Routledge, 2012), 120.

7 Mitchell, Iconology,4.

8 In the works of Blenkinsopp, it is noted that either during or after Babylonian exile, the learned Israelites "were engaged in constructing, in response to the experience of derivation and exile, a conceptual world of meaning in which historical reconstruction, the recovery of a usable past, played an important role. We have good reason to find Genesis 12-50, and elsewhere in the Pentateuch, the fruits of these labours." See loseph Blenkinsopp, The Pentateuch (London: SCM Press, 1992), 120-21.

9 See Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972); Moshe Weinfeld, The Promise of the Land: The Inheritance of the Land of Canaan by the Israelites (TLJS 3; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993); Raymond F. Person, The Deuteronomistic History and the Book of Chronicles: Scribal Works in an Oral World (SBLAIL 6; Atlanta, Ga.: Society of Biblical Literature, 2010); and Richard H. Lowery, The Reforming Kings: Cults and Society in First Temple Judah (ISOTSup 120; Sheffield: ISOT Press, 1991).

10 See Diane Banks, Writing the History of Israel (LHBOTS 438; London: T&T Clark, 2006), 207.

11 Banks, Writing the History, 207. Banks intimate that there is a traceable historical background recorded in the text, which both textual scholars and archaeologists can used to reconstruct the history of the biblical world.

12 See David I. A. Clines, Interested Parties: The Ideology of Writers and Readers of the Hebrew Bible (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 26. Clines calls this approach a quantum leap from the traditional approaches as historical criticism, form criticism and redaction criticism. In his reading of the Ten Commandments, he invents a metaphor of reading them from left to right.

13 It means acceptance of the convention, and adopting the world of the text, the world and worldview of the author and the original intentions of the text. It would be interesting to imagine how the story of Sodom and Gomorrah would sound if retold from their point of view, as also how the story of Esther would be told from the Persian theological and ideological standpoint; and Jezebel from the stand viewpoint of a Sidonian narrator.

14 Cheryl J. Exum, Fragmented Women: Feminist (Sub)Versions of Biblical Narratives (Sheffield: JSOT, 1993), 9.

15 Exum, Fragmented Women, 9.

16 Exum, Fragmented Women, 42-43; 44. Exum in defragmenting Michal presents the whole story from her family context mentioning details of her family members before she was declared childless.

17 For instance: what are the interests of the writer in the story, and why does he openly show antipathy to Sodom and Gomorrah throughout the text? If the people of Sodom and Gomorrah were hostile and homosexual rapists, why did they allow Lot to settle in their territory without an incident of harassment? 2). Why is Sodom and Gomorrah story presented in the narrative context of Abraham? Is Sodom and Lot killed off from the Abraham narrative to provide continuity of Abraham's blessings? Some, if not all these question have been answered by many different scholarly writings like: Dan Rickett, "Rethinking the Place and Purpose of Genesis 13," JSOT 36/1 (2011): 31-53; Volker Glissmann, "Genesis 14: A Diaspora Novella," JSOT 34/1 (2009): 33-45; etc.

18 Ever since the Prolegomena to the History of Israel was published by Julius Wellhausen in 1878, there is no groundbreaking study that disputes the fact that the Pentateuch was an exilic and postexilic literature, and that the events refereed in it are purposefully dressed to suite interests of the postexilic audience. See also Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012). Eventual scholars like Thompson have described the Genesis stories as unhistorical and ungrounded on "historical memory, but based on a very late theological schema that presupposes a very unhistorical worldview." See Thomas L. Thompson, The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives (Harrisburg: Trinity, 2002), 315. Elsewhere, Thompson has argued that the patriarchal narratives exhibit many characteristics of folktales and could profitably be studied as a literature whose function was more sociological rather than historical. See Thomas L. Thompson, "The Joseph and Moses Narratives," in Israelite and Judean History (ed. John H. Hayes and J. Maxwell Miller; Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1977), 178.; Also see John Van Seters, Abraham in History and Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975). Needless to say, there are several allusions in the Pentateuch accounts that suggest that events were recorded later: Gen 16:14 " . . . it is still there to day," 19:37 "... Moab; he is the father of the Moabites of today," 19:38 "... Ben-Ammi; he is the father of the Ammonites of today."

19 On ambiguities in art, see; Judith F. Tormey and Alan Tormey, "Arts and Ambiguity," Leornardo 16/3 (1983): 183-87.

20 Of the scholarly works on some of these chapters worth mentioning include writings of Dan Rickett, "Rethinking," and numerous articles in Noort and Tigchelaar book, which deal, among other issues the ideological motifs behind the scenes in the production of the texts. Edward Noort and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, Sodom's Sin: Genesis 18-19 and Its Interpretation (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

21 On the discussion on the significance of name change and circumcision see Joseph Fleishman, "On the Significance of a Name Change and Circumcision in Genesis 17," JANES 28 (2001):26, 30-31.

22 This caricature, needless to say befits the writer's ideological interests of othering nations as evil depicting the nations as the evil other, and Abraham as righteous. Besides the bias that this creates, this embellishment proposal stirs the audiences' curiosity and interests to know the wickedness and sin of Sodom and Gomorrah.

23 This, always anonymous escapee is very common in the HB, especially in situations of war or crisis. He is the informant, whose role is linking the major protagonist in the text to the events far beyond. We see this case in 2 Sam 1, Ezek 24:26-27, 33:21-22 among others.

24 The Hebrew  means "my king is righteous." If we take this as a play on words, Melchizedek could be personified as a character that is addressing Abraham as "my king," and worshipping Abraham's God. It is interesting that Melchizedek's theological context in Canaan is not clear. He is worshiping the God of Abraham- God Most High, creator of Heaven and Earth in a theological context that do detestable things against the God of Abraham.

means "my king is righteous." If we take this as a play on words, Melchizedek could be personified as a character that is addressing Abraham as "my king," and worshipping Abraham's God. It is interesting that Melchizedek's theological context in Canaan is not clear. He is worshiping the God of Abraham- God Most High, creator of Heaven and Earth in a theological context that do detestable things against the God of Abraham.

25 Salem, in Hebrew  is commonly associated with Jerusalem. In Ps 76:2, it is associated with Zion, the place of the tabernacle and his dwelling place.

is commonly associated with Jerusalem. In Ps 76:2, it is associated with Zion, the place of the tabernacle and his dwelling place.

26 Thomas L. McDonald, "Bread in the Old Testament," n.p. [cited 1 September 2015 ]. Online : http://www.patheos com/blogs/godandthemachine/2012/12/bread-in-the-old-testament/.

27 Thomas L. McDonald, "Wine in the Old Testament," n.p. [cited 1 September 2015]. Online: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/godandthemachine/2012/12/wine-in-the-old-testament/.

28 McDonald, "Wine," http://www.patheos.com/blogs/godandthemachine/2012/12/wine-in-the-old-testament/.

29 See Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Genesis Apocryphon of Qumran Cave I: A Commentary (BibOr; Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1966), 245.

30 Chapters 15, 16 and 17 all end without the mention of Sodom and Gomorrah. TTiese sections of Genesis are purposefully devoted to Abra[ha]m: his covenant with the divine, birth of Ishmael and the circumcision covenant. However, ch. 18 accentuates two issues: hospitality and the idea of the son. The arrival and sight of the three angel-men enchanted Abraham as they heralded good tidings of the son. Verse 1-15 of this chapter depict Abraham as actively catering as the guests are relishing. Abraham is presented practicing the ancient traits of hospitality-giving the men water to wash their feet and serving them with a great meal. The muted conversation ends with the promise of a son to Abraham, though the idea was laughable to Sarah- serving as the appropriate introduction to Isaac's name later in Gen 21. Interestingly, the boy's name  has a masc. 3rd person sg. prefix to denote "he laughed or he will laugh." Who laughed-Abraham or Sarah?

has a masc. 3rd person sg. prefix to denote "he laughed or he will laugh." Who laughed-Abraham or Sarah?

31 Elsewhere, the verb used for divine choice is  (Deut 7:7, 14:2; Neh 9:7, Isa 44:1, and Ezek 20:5 among others).

(Deut 7:7, 14:2; Neh 9:7, Isa 44:1, and Ezek 20:5 among others).

32 Cf 1 Kgs3:14;Pss81, 13.

33 This further attunes the reader to curiously seek to understand "the grave sin" of Sodom and Gomorrah.

34 In some cases, the outcries are directed any other figure of authority as kings (see 2 Sam 19:29 and Jer 11:12).

35 The rendition in the lxx of this phrase suggests a plenary genitive noun which produces both subjective and objective notions. Sodom and Gomorrah are both subjects and objects of the outcry, which is overheard by God. This could suggest that there were both victims and culprits in Sodom and Gomorrah. See Wallace's definition of plenary genitive in, Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basic: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 1996), 119-20.

36 The author wanted to demonstrate that the fate and demonstration of Sodom and Gomorrah is in the ideological notion of divine choice and divine rejection.