Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.28 n.3 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n3a14

Not free while nature remains colonised: A decolonial reading of Isaiah 11:6-9

Hulisani Ramantswana

UNISA

ABSTRACT

The Western colonial system not only colonised African human beings, it also colonised nature, with particular reference to Africa's wildlife. The colonial system disrupted the harmony that existed between human beings and nature by colonising both, thereby causing a divide between human beings and nature. On the basis of Isa 11:6-9, the argument in this article is that human liberty is intertwined with the liberty of nature. The African human is not free as long as Africa's wildlife remains colonised. Therefore, decolonisation remains incomplete as long the colonial matrix of power that divides African humans from nature persists.

Keywords: nature, freedom, colonisation, decolonial reading, Isaiah

A INTRODUCTION

The collapse of the colonial administrations in Africa did not necessarily amount to an end of colonial structures. Coloniality as an invisible structure of the global power structures that sustain the colonial relations of domination, and exploitation survives colonialism.1 As Maldonado-Torres argues,

Coloniality is different from colonialism. Colonialism denotes a political and economic relation in which the sovereignty of a nation or a people rests on the power of another nation, which makes such nation an empire. Coloniality, instead, refers to long-standing patterns that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labour, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administration.2

Colonialism not only created new structures of political, economic, and social relations, it also transformed nature by creating new landscapes and relations between humans and non-human nature. In this process, both humans and non-human nature were colonised.3 As Shiva notes,

the transformation of the perception of nature during the industrial and scientific revolutions illustrates how "nature" was transformed in the European mind from a self-organizing, living system to a mere raw material for human exploitation, needing management and control.4

The tendency to focus on human freedom at the neglect of nature is problematic. This article grapples with the question whether the process of decolonisation can be complete without including the wildlife agenda. The argument that this article makes is that human freedom is intertwined with the freedom of nature and therefore the two should not be separated. Decolonisation remains incomplete as long the colonial matrix of power that divides African humans from nature persists. In conformity with this view, the paper intends to examine how coloniality affects wildlife and then suggest possible corrective measures to be undertaken. This venture will be based on a decolo-nial reading of Isa 11:6-9.

In order to carry out this task, this article is structured as follows: The first section gives a background commentary on the collapse of the colonial administrations in Africa and the enduring colonial structures that continue to shape the human and nature relationship. In the second session, we engage in a decolonial reading of Isa 11:6-9 particularly focused on pro-Persian elements and voices of resistance in Isaiah. The third section continues with a decolonial reading of Isaiah by highlighting the way in which Persian domination during the post-exilic was over both human beings and nature, which led to voices of resistance within the Yehud community projecting a new world order. This section also presents proposals regarding dismantling colonial structures as a means of justice in the African context. The final section is the conclusion and it highlights the necessity of decolonisation considering the inextricable connectedness of life.

B COLONIAL BORDERS: NATURE REMAINS COLONISED

The Berlin conferences of 1884-1885 by the fourteen European nations marked the climax of the colonisation of Africa, as it laid the framework for continuing European colonisation, borders, navigation, and trade in Africa. The entire African continent was partitioned among the European imperial powers. As Ali Mazrui has argued, the "partitioning of the African continent unleashed unprecedented changes in African societies: political, economic, cultural, and psychological."5

The colonial borders or fences became symbols of the colonial definition of ownership, protection, incarceration, inclusion, and exclusion.6 The colonial borders were not limited to the creation of national borders for the separate states under colonial administration; they also became functional as instruments of internal administration. In the South African context, the land was further partitioned by the Native Land Act of 1913 so that 92% of the land belonged to whites, with only 8% belonging to blacks; the land allocated to blacks was increased to 13% through the Native Land Act of 1936. In addition, under the apartheid ideology of separate development, the land holdings of the black ethnic groups were reduced to black units within the Union of South Africa by the Promotion of the Black Self-Government Act, the preamble of which stated,

The Bantu people of the Union of South Africa do not constitute a homogenous people, but form separate national units on the basis of language and culture. . . . It is desirable for the welfare of said people to afford recognition of the various national units and provide for their gradual development within their own to self-governing units on the basis of Bantu systems of government.

Human liberation from colonialism within the African context at the macro level meant the collapse of the colonial administration; however, the colonial borders inherited from colonial partitioning were retained. Following the independence of some of the African states in the 1950's and 1960's, African heads of states at the Organization of African Unity (OAU) agreed to retain the colonial borders as state borders. The elimination of the colonial administration did not amount to decolonisation in Africa; the structures of colonialism did not evaporate and are to a large extent endorsed in the so called post-colonial world.7 At the micro level, within the South African context, human liberation was unimaginable until the colonial borders of the so-called, "separate national units" were eliminated.

The colonial borders not only alienated African humans from each other, but also served to alienate humans from nature. As Adams notes, "the acquisition of colonies was accompanied by, and to a large extent enabled by, [the] profound belief in the possibility of restructuring nature and reordering it to serve human needs and [the] desires" of the white/European/capitalist colonisers.8 The colonial restructuring and reordering of nature was an act of separatism, and as Mignolo notes,

the idea that humanity is universally defined by its separation from nature first emerged in seventeenth-century Europe and developed with the industrial revolution, as the appropriation of lands increased, accompanied by the increasing demand for natural resources.9

The separatism mentality was also a violation of African people and nature, as it changed land use and brought about displacement and conflict. The harmony or interconnectedness that existed between humans and nature was disturbed by the creation of borders between states and borders between humans and nature, and by the plunder and exploitation of both humans and other forms of nature.

During the colonial period, the plundering and exploitation of nature was so widespread that George Perkins Marsh in his Man and Nature (1864) observed,

[M]an is everywhere the disturbing agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned to discords. The proportions and accommodations which ensured the stability of existing arrangements are overthrown.10

Marsh's reference to "man" does not have to be understood as reference to humanity in general, but only to the white/European/capitalist, who through colonialism was disturbing the harmony of nature. The African landscape was transformed in the name of civilisation. When the preservation of wildlife became a concern following the environmental degeneration, the African colonial powers (Germany, France, Britain, Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Belgium) signed a convention for the preservation of animals, birds, and fish in Africa in 1900.11 The animals were placed in five different categories or schedules in accordance to the level of protection the animals were deemed to require: category 1: animals that were not supposed to be hunted or destroyed;12 category 2: animals that should not be hunted or destroyed while they were still young;13category 3, female animals that should not be hunted or destroyed while mothering;14 category 4, animals that may be hunted or destroyed in limited numbers;15 category 5, harmful animals that had to be reduced in number.16 The colonial empires assumed a position of superiority not only over African humans, but also over wildlife. It was the colonialist who now had the right to decide which animals to preserve and which to kill. The London Convention in as much as it was concerned with hunting as a threat to African wildlife, its regulatory framework impacted on where Africans had to live, what they had to eat, and how they should sustain themselves.17 As Ramutsindela observes, "the colonised societies had their own understanding of nature - and how it should be used and or protected - long before the formalisation and institutionalisation of colonialism."18 This is not to claim that the indigenous people did not exploit their fauna in pre-colonial times; however, it never reached a point of crisis of extinction as was done by the colonial empires within a few centuries of colonial exploitation, which threatened both human life and wildlife.19

The Euro-Western view of nature brought with it the idea of the national park, that is, areas in which nature can be preserved with little human interference. The colonial states conserved nature for the following reasons, among others: First, conservation served as a means of resource appropriation, both for generating private capital and for generating revenue for the state. Second, it was a response to environmental concerns. Third, the idealistic view of nature necessitated the preservation of nature as Eden.20 In Southern Africa the following areas were set apart as conservation areas: the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, the Moremi Game Reserve, and Chiefs Island in Botswana; Mvuradonha, Matopos, and Gonarezhou National Parks in Zimbabwe; Tsidilo Hills, Mamili National Park, and Slambala in Namibia; and Hluhluwe and Umfolozi National Parks in South Africa. Grove notes, "Colonial states increasingly found conservation to their taste and economic advantage, particularly in ensuring sustainable timber and water supplies and in using the structure of forest protection to control their unruly and marginal subjects."21 It should be noted that colonial actors utilised legislations both to exploit and to try to counter the Overexploitation of natural resources in Africa. However, it was only after centuries of exploitation that colonial actors attempted to counter the colonial destruction of African fauna through legislations.22

Inasmuch as the European preservationist agenda to reserve wildlife through national parks in Africa was also motivated by the idea to preserve "Eden" in the face of the continuing human (European/Western/white) ravaging of nature, it cannot be divorced from the systematic expropriation of land and natural resources from the indigenous people.23 Thus, national parks did not simply serve as a means to control hunting and to conserve nature; they also functioned as buffer zones in one way or the other.24 In some instances national parks functioned as war zones that separated the hostile parties. The Kruger National Park in South Africa also functioned as a military buffer or "war" zone that safeguarded the apartheid regime from insurgency.25 The national parks also served as instruments of land expropriation from the indigenous people in the services of the colonial governments. Thus, the colonial conservation agenda had to be executed at the expense of the indigenous people, who had to lose their land. The national parks are colonial structures that

enact the colonisation of nature, and the "natives," by "setting aside" areas of conservation of "nature," and by the exclusion of the "natives" from those areas, and their omission from enabling managing legislation.26

The demise of colonial administrations in Africa has not necessarily resulted in the collapse of all the colonial structures. Nature remains colonised in national parks and game reserves, and it is essential for Africans to realise that their freedom is intertwined with the freedom of nature.

C A DECOLONIAL READING OF ISAIAH 11:6-9: ANOTHER WORLD IS POSSIBLE

Isaiah 11:6-9 is set within the context of the defeat and humiliation of Israel during the period of domination by the Assyrian Empire. In Isa 1-11, the focus is on the traumatic years in which the Assyrian Empire not only devastated the land of Judah but also brought to an end the Northern Kingdom of Israel. Childs, focusing on the theological context of Isa 11:1-9, argues the following: first, that the promise of a new shoot from the old stump of Jesse serves on the one hand as a reminder of the Davidic dynasty, its beginnings and its divine election, and on the other hand, it intertextually serves to draw together the theme of holy seed from a stump in 6:13 and the true Israel that will rise due to the Immanuel in Isa 7. Second, the wisdom of the shoot should be contrasted with the ruthless Assyrian destruction. The messianic figure, who is endowed with the spirit, knowledge and fear of Yahweh, and exercises righteousness, brings about universal peace that encompasses both the human and animal world. Third, the universal peace that the messianic figure brings is set within the eschatological context and serves as an expansion of the promise in Isa 9 of an eschatological deliverance of God's people. Fourth, in the final form of the Isaiah text, Isa 65:25 (cf. Hab 2:14) serve as an echo of Isa 11:6-9, this despite the fact that Isa 65:25 and Hab 2:14 are late postexilic texts. The motif of transformation of nature into a paradisiacal harmony which is characteristic of the postexilic period was retrojected back to the Isaianic core in 11:1-5 to expand the vision.27 While the theological context is important, we do not have to overlook the multiple voices within the book, which highlight the differing responses of post-exilic Yehud community offered towards their lived experience under the Persian empire.

The view adopted in this study is that the book of Isaiah, at least in its final form, is a postexilic text. This, however, is not to discount that there are texts that stem from the eighth-century prophet Isaiah, son of Amoz.28 The book of Isaiah, like other canonical books to some extent, served the needs of the Persian empire and its Jewish proponents in Yehud. However, this does not imply that the book in its entirety served the needs of the Persian Empire. The book in its final form contains multiple voices, perspectives, and ideologies that are not entirely consistent with each other. As Tull argues, the multiple voices within the book of Isaiah in its final form are not

brought under the control of the last editor[;] the book's polyphonic nature stands. Voices of inclusion of the nations, voices supporting Israel's domination, and voices supporting Israel's missional calling before the nations all fight for control. Voices asserting communal and individual responsibility, collective and individual identity, each speak their piece.29

Reading of the biblical text from a decolonial perspective entails reading the text with sensibility to issues of relationship between the coloniser and colonised. Therefore, our interest is particularly on the ideological use of the texts. This study proceeds with the assumption that voices that served the needs of the empire can be heard in the canonical texts and so also the voices of resistance.

1 Pro-Persian Elements in Isaiah

The overt references to Cyrus in Isa 44 and 45 are indicators not only of the possible late date of the materials in Isa 40-55/66, but also of the pro-Persian elements in the book.30 The pro-Persian sentiments are also reflected in other post-exilic books such as Chronicles,31 Ezra-Nehemiah,32 and Daniel,33 in which the name of Cyrus is mentioned. In Isaiah the name of Cyrus, king of Persia, is mentioned three times: he is referred to as a shepherd (44:28), as the Lord's anointed one (45:1), and as the Lord's "righteous" one through whom the city will be rebuilt and the exiles freed (45:13).

Cyrus as the announced royal figure in Isa 44-55 seems to take the role of the announced Davidic figure in Isa 11:1-9. The three motifs-shepherd, anointing, and righteousness-are intertextual linkages with 11:1-9. Cyrus as shepherd assumes the role of the child shepherd in 11:6 (cf. 7:14-15;34 9:6-735); as anointed one, Cyrus fulfils Isa 11:2, "the Spirit will rest on him," the result of an act of anointing; as the Lord's righteous one, Cyrus fulfils Isa 11:4-5, as he becomes the righteous judge who delivers Judah from exile and rebuilds the city. As Wagner notes,

with the announcement of the fall of the Davidic dynasty and the subordination of the descendants under the Babylonian king, the call of Cyrus becomes possible in the notion of the reader. What is formulated as an anticipation of the deportation of King Jehoiachin and his sons in the book of Kings in 2 Kgs 20, is used as an explanation for why Cyrus could be called by the Lord even if this contradicts the expectation of Isa 11.36

The Cyrus prophecy in Isa 44:24-45:7 reflects a voice that supported the empire and its ideology. The empire, as Berquist argues, utilised even the canonical texts to exercise dominance over colonial Yehud.37 In the context of Isaiah, within the Persian imperial ideology, the Persian Empire contrasts with both the Assyrian and the Babylonian empires. The Assyrian empire is God's instrument of destruction, not of salvation (see Isa 7; 8; 10). However, unlik Israel, Judah survived.38 The fall of Judah will come through the Babylonian empire (Isa 39), and the Babylonian empire itself will also fall at the hand of the Medes (Isa 13; 14; 21:9).39 The Persian Empire is thus presented as a benevolent empire that instead of completely assimilating people gives them freedom to rebuild their city and their worship. The use of the exodus motif in Isa 40-55 allows the Persian Empire to assume the roles of Moses and Joshua, respectively the liberator of Israel from Egypt and the one who leads the people into the land, as it becomes the liberator of the Jews from Babylon. The Persian Empire thus becomes the new Moses and the new Joshua in the person of Cyrus. Cyrus as the Lord's anointed and shepherd liberates the people from exile and resettles them back in Yehud as a shepherd (cf. Num 27:26-27). Thus, from the hegemonic side, Cyrus is presented as unlike Assyria and unlike Babylon. Cyrus is glorified by the pro-Persian voice in the book to such an extent that he is even granted the title of anointed one ( ) (Isa 45:1), a title reserved for the Davidic kings.40

) (Isa 45:1), a title reserved for the Davidic kings.40

Blenkinsopp also argues that legitimation of the Persian empire in Isa 40-55, although not unconditional, as it expected the Jewish communities to be given freedom "to worship their deity in their own place of worship and to conduct undisturbed their religious practices," did open "the possibility of a future without the apparatus of an independent state system," providing them allowance to serve within the imperial court and to assume even the high offices therein.41 Therefore, it is not surprising to find books such as Esther and Daniel displaying diaspora Jews as attaining some of the highest positions and able to support their compatriots.42

2 Voices of Resistance: Another World Is Possible

Texts produced under imperial rule can be used for the benefit of the empire, but they can also be used to give voice to anticolonial resistance with the aim of dethroning the empire.43 The subaltern Judean voices continued to hope for reinstallation of the Davidic king. Though some of the roles of the messianic figure pictured in Isa 11 seem to be taken over by Cyrus, there are certain contrasts that point to dissension from some within the post-exilic Yehud community. The Persian Empire, as Cataldo points out, often had to quell rebellions from the provincial governments that sought self-governance.44 The local laws permitted in the territories within the empire could function as long as they were within the Persian imperial law or the "law of the king."45

The messianic figure in Isa 11:1 is identified with David: "A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse; from his roots a branch will bear fruit"

). In the book of Isaiah, there is no mention of any other Judean king after Hezekiah. Thus, in Isaiah, King Hezekiah is presented as the cut-off point with this announcement:

). In the book of Isaiah, there is no mention of any other Judean king after Hezekiah. Thus, in Isaiah, King Hezekiah is presented as the cut-off point with this announcement:

The time will surely come when everything in your palace, and all that your fathers have stored up until this day, will be carried off to Babylon. Nothing will be left, says the Lord. And some of your descendants, your own flesh and blood who will be born to you, will be taken away, and they will become eunuchs in the palace of the king of Babylon (Isa 39:6-7 NIV).

The book of Isaiah thus puts the blame for the exile squarely on Hezekiah and not on the kings who came after him. This move, as some scholars observe, was to link the later material in Isa 40-66 with the prophet Isaiah.46However, the hopes that the Davidic kingdom will rise again proceed beyond the cut-off point in Isa 39, not so much by being taken up in so-called Deutero-Isaiah and Trito-Isaiah, but more so from the prophecies within Isa 1-39. In Isa 40-66, there is only one reference to David (55:3). Isaiah 55:3 is generally regarded by scholars as a démocratisation of the Davidic covenant that transfers the promises that were made to David to the restored community, indicating that the Judean community had abandoned hope for a restoration of the Davidic dynasty.47 The meagre singular appearance of the name of David at the end of Deutero-Isaiah should rather be viewed as a counter voice to the dominant pro-Persian voices that transferred the Davidic roles to Cyrus. For the anti-Persian voices, the Davidic covenant is viewed as an "everlasting covenant" (

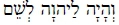

).48 While it can be accepted that Isa 40-66 to a large extent reflects a situation in which Persian rule was accepted as divinely ordained, pace Schramm, this does not imply a total lack of anti-Persian polemic.49 The reference to David in Isa 55:3 is better viewed as evoking the continuity of the Davidic covenant post the cut-off of the Davidic dynasty by the Babylonians. The hope for the continuity of the Davidic dynasty while under the rule of the Persian Empire is summarised as follows in Isa 55:13: "And it shall be to the Lord for a memorial, for an everlasting sign which shall not be cut off (

).48 While it can be accepted that Isa 40-66 to a large extent reflects a situation in which Persian rule was accepted as divinely ordained, pace Schramm, this does not imply a total lack of anti-Persian polemic.49 The reference to David in Isa 55:3 is better viewed as evoking the continuity of the Davidic covenant post the cut-off of the Davidic dynasty by the Babylonians. The hope for the continuity of the Davidic dynasty while under the rule of the Persian Empire is summarised as follows in Isa 55:13: "And it shall be to the Lord for a memorial, for an everlasting sign which shall not be cut off (

).50

).50

In Isa 11:1 the image of a tree that is cut down, from which the Davidic king will rise again, presents a contrast with the Persian Empire. The imagery of a cosmic tree as the symbol of a king serves to highlight the splendour of the king and his kingdom in the ANE.51The image of a tree cut down could not have referred to the Persian Empire in its glorious state. To refer to the Persian Empire in its glory as a tree that is cut down would not have made sense.52

For the voices of resistance against the empire, another world was possible outside of the Persian Empire. For the subaltern Judean voices, the messianic hope of Israel did not lie in the dominating empire; rather, it would stem as at the beginning of the Davidic dynasty from a humble beginning. The imagery of the "shoot" or a "youth growth" or "twig" also ties in well with the idea of messianic hope, which is also tied in with a "child."53 Thus, for some of the anti-Persian voices, Israel's glorious future would be realised as coming from the bottom up, and not from top to bottom, as it was with Cyrus.

3 An Outcry for the Liberation of Nature

The imagery used in Isa 11:6-9 and 65:25 of the peaceful coexistence of humanity and animals was probably to provide a contrast to the domination of the empire over nature. In Neh 9:36-37, Ezra states,

But see, we are slaves today, slaves in the land you gave our forefathers so they could eat its fruit and the other good things it produces. Because of our sins, its abundant harvest goes to the kings you have placed over us. They rule over our bodies and our cattle (

) as they please. We are in great distress (Niv, emphasis added).

The empire was exerting its force not only over human bodies, but also over animals. The term used in Neh 9:37,  can be used to refer to both wild animals and domesticated animals, and in this instance, probably both the wild animals and the domestic animals were in view. Much scholarly discussion has focused on the enslavement of the humans to the neglect of the enslavement of the animals. This complaint in Neh 9:36-37 is in many ways similar to the complaint in Isa 65:17-25, which is generally regarded as a postexilic text. This text envisions a future in which human liberty is intertwined with animal liberty. The two are projected as going together. The retrojection of Isa 65:25 into Isa 11 in some respects also serves to highlight the resistance to the Persian Empire's domination over human beings and nature.

can be used to refer to both wild animals and domesticated animals, and in this instance, probably both the wild animals and the domestic animals were in view. Much scholarly discussion has focused on the enslavement of the humans to the neglect of the enslavement of the animals. This complaint in Neh 9:36-37 is in many ways similar to the complaint in Isa 65:17-25, which is generally regarded as a postexilic text. This text envisions a future in which human liberty is intertwined with animal liberty. The two are projected as going together. The retrojection of Isa 65:25 into Isa 11 in some respects also serves to highlight the resistance to the Persian Empire's domination over human beings and nature.

The expansion of the empire over other territories meant that those territories had to pay tribute and offer the natural riches of their lands to the empire. During the post-exilic period, within the biblical text, two Persian kings are displayed as having owned royal gardens, Xerxes (Esth 1:5; 7:7) and Artaxerxes (Neh 2:8). We focus only on the royal garden in Yehud. Nehemiah 2:8 states,

"And may I have a letter to Asaph, keeper of the king's forest (

), so he will give me timber to make beams for the gates of the citadel by the temple and for the city wall and for the residence I will occupy?" And because the gracious hand of my God was upon me, the king granted my requests (Neh 2:8 NIV).

The idea of royal gardens or parks was common in the ANE. Some of the kings from the ANE boasted about their exotic gardens, among them Tiglath-Pileser I (1114-1076 B.C.E.), Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 B.C.E.), Sennacherib (706-681 B.C.E.), Sargon II (721-705 B.C.E.), and Merodach-Baladan II (721710 B.C.E.).54The Persian kings also established royal parks, which were a symbol of power.55 The royal parks were decorated with flora and fauna; animals both wild and domestic were also stocked. The royal parks also functioned as grounds for the hunting of wild animals by the royals, as wild animals were captured and placed in such parks for the aggrandisement and enjoyment of the kings. Royal parks thus served as colonial space in which wild animals were colonised for enjoyment by the royals. In Xenophon, Cyr. 1.4.5, 11, 1415, we read the following about Cyrus:

[Cyrus] before too long had exhausted the supply of animals in the park by hunting, shooting and killing them, so that Astyages was no longer able to collect animals for him. And when Cyrus saw that notwithstanding his desire to do so, the king was unable to provide him with many animals alive, he said to him: "Why should you take the trouble, grandfather, to gem animals for me? If you will only send me out with with my uncle to hunt, I shall consider that all the animals I see were bred for me" . . . [Cyrus said to his friends], 'What tomfoolery it was, fellows, when we used to hunt the animals in the park. To me at least, it seems just like hunting animals that were tied up. For, in the first place, they were in a small space; besides, they were lean and mangy; and one of them was lame and another maimed. But the animals out on the mountains and the plains-how fine they looked, and large and sleek!" . . .

However, when Astyages saw that he [Cyrus] was exceedingly disappointed, wishing to bring him pleasure, he took him out to hunt; he had got the boys together, and a large number of men both on foot and on horseback, and when he had driven the wild animals out into country where riding was practicable, he instituted a great hunt. And as he was present himself, he gave the royal command that no one should throw a spear before Cyrus had his fill of hunting.

In royal hunting, the idea of not throwing a spear before the king did was promulgated as law. According to Plutarch, Moralia 173d, it was only during the reign of Artaxerxes I that this law changed:

[Artaxerxes I] was the first to issue an order that any of his companions in the hunt who could and would might throw their spears without waiting for him to throw first.

Royal hunting, however, was not limited to the paradeisoi; the best thrill for the kings, as Xenophon suggests, came from hunting in the wild.

The future envisioned in this text in a sense reflects a restoration of the relations between humanity and nature in the Garden of Eden prior to what is commonly referred to as the fall of humanity, which in its mythological sense came about from the interaction of humanity and the animal kingdom (Gen 23). As Aune observes,

the imagery of Isaiah's prophecy that "the wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid" (Isa 11:6), is a vision which conceptualizes the idyllic future in the imagery drawn from the myth of Eden.56

However, we need to tread with care, as the new world in the book of Isaiah is not another world that would replace the current world; rather, it is a projection of change in the people's lived experiences.

The hope for the new creation does not have to amount solely to the eschatological hope of better things to come in the life after death; rather, it should be the hope for a better world in the present or the current world. This is clear in Isa 65:17-25, in which the projected new creation, inasmuch as it will be a place of rejoicing with no sound of weeping and crying, will include the following among other things: childbearing (infants will still be born, which is symbolic of life), longevity, death, and labour (building houses and planting of vines, peaceful coexistence of domestic and wild animals). The voices of resistance within Isa 11:6-9 and 65:17-25 were imagining a world outside of the Persian Empire in which they would be free of the demands and dominance of the imperial power, both they and the animals. For the voices of resistance, their freedom was intertwined with the freedom of animals both domestic and wild.

In our current context, the colonial empires brought with them notions of power in which they not only considered themselves as racially superior, but also placed themselves above other species, thereby legitimising their control over nature.57 As Coates argues, "animals, plants, rivers and forests - like non-whites, non-elite, women, gays and other 'marginalized groups of people' - have a history that should be restored to them."58 The challenge in our context is that the colonial structures have become so deeply embedded that we can no longer imagine living together with the elephant, rhino, lion, tiger, buffalo, and others without being separated by the colonial fences. The structures of coloniality now survive in the absence of colonial administrators. Under the influence of the capitalist system, nature has become a resource of capital gain for the state and the privileged few who own parks and game reserves and the animals therein. Therefore, in the service of the structures of coloniality, nature remains colonised to service tourists and hunters both local and foreign while economically excluding the majority of our people, whose land was dispossessed. The dismantling of the colonial boundaries between humans and animals in our current context is an ideal toward which the African people have to strive as a means of justice, not just for African humans but also for nature.

The liberation of nature has to be viewed as an ecological restoration process. Conservation ecology, that is, the setting aside or the preservation of nature in separation is not an adequate solution. Restoration ecology has to do with the safeguarding and the repairing of nature-the ecosystem and biodiversity, and natural capital-the renewable and non-renewable resources from nature.59 As Andel and Aronson note,

For restoration ecology to be effective, we must not only consider the biophysical context, but also the socio-economic and political matrix in which a restoration project must be planned, financed and carried out.60

The liberation of nature as a restorative process in our context should include the following aspects among others:

First, the liberation of wildlife is intertwined with the reversal of the legacy of colonialism, which forcefully transitioned land-rich societies into land-poor societies, by returning land to its rightful owners. We are like the Yehud community, who had the freedom to return to their land yet were still under imperial domination, enslaved in their own land. We too are in the land, yet the majority of the indigenous people are still landless. Land dispossession through establishment of national parks contributed to the dehumanisation of the African people by taking away their land rights and their resources, and it disrupted their relationship with nature. This resulted in the criminalisation of the indigenous people in the national parks, who have been regarded as poachers when they have attempted to gain access to the land resources that they had access to for generations.61 In the South African context, the reversal requires fast-tracking of the land reform programme, which so far has failed dismally to produce the desired results: the delivery of land back to the indigenous people has been a shifting target since the dawn of democracy.62

Second, there is a need to value African indigenous knowledge regarding human relationships with nature (animals, hills and mountains, rivers, forests, plants, etc.). For the voices of resistance within the Yehud community, their freedom was incomplete as long as their relationship with animals was disrupted by colonial relations. They regarded the colonial power over themselves and the animals as a form of disruption of nature.

In the African context, the colonial creation of parks and land dispossession from the indigenous people brought about a separation of nature and culture. The African people in some instances define themselves in terms of nature by choosing an animal as a totem or symbol of their identity. In my clan, the Babirwa people, whether in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, or elsewhere, our totem is a Nare/Nari/Nyathi (buffalo). Thus, by identifying themselves through animal totems, the African ancestors saw themselves as connected with nature and as part of nature. Clans took pride in their totems as their identity markers-a totem made a clan unique among others. West, Igoe, and Brock-ington argue from an anthropological perspective that

the discursive separation of people and their surrounding into categories of nature, culture, environment, and society ... mirror Western imaginaties of nature and culture and impose them on much of the world.63

Mavhunga argues regarding the African people,

People might have been physically removed and resettled outside, but their hearts, spiritualities, and material yearning never left the land that became the national park. They remained inside it, and interpreted its landscapes according to their own meanings and practices.64

The African oral traditions, folktales, praise poems, riddles, proverbs, and songs that have been transmitted from generation to generation are useful resources for understanding our relationship with nature and for carving a way forward as we strive to undo the colonial damage. For our African knowledge systems to continue to grow and develop, the African people should have access to nature and its natural resources. The modern conservation and biodiversity concerns should not be utilised as means of exclusion by perpetuating the marginalisation of the majority of Africans from the secluded areas, as this serves to choke the development of African indigenous knowledge systems.

Third, the colonial boundaries that have been placed between human and nature for economic benefit must be overcome. The colonisation of nature is somewhat retained for economic benefits - stimulation of the economy through tourism and employment in the parks. The benefactors of the Persian Empire within the Yehud community probably did the same thing for the economic benefits they enjoyed from the empire, which in turn made them perpetuate the status quo. However, the economic benefits that the supporters enjoyed came from heavy taxation of the Yehud community, which had to hold the short end of the stick, as it hardly benefited from the drain of its resources. Nehemiah 5:1-5 highlights the problem:

Now the men and their wives raised a great outcry against their Jewish brothers. Some were saying, "We and our sons and daughters are numerous; in order for us to eat and stay alive, we must get grain." Others were saying, "We are mortgaging our fields, our vineyards and our homes to get grain during the famine." Still others were saying, "We have had to borrow money to pay the king's tax on our fields and vineyards. Although we are of the same flesh and blood as our countrymen and though our sons are as good as theirs, yet we have to subject our sons and daughters to slavery. Some of our daughters have already been enslaved, but we are powerless, because our fields and our vineyards belong to others" (Neh 5:1-5, NIV, emphasis added).

In the South African context, as Ramutsindela argues, "Economic benefits were useful in persuading post-independence leaders to establish and/or expand nature reserves and national parks."65 This, as Ramutsindela further notes, led to African leaders embracing the colonial parks and game reserves without the African values that were interrupted by such establishments; it also led to "the failure to redefine landscapes, wildlife and marine resources as a heritage and resource for hitherto marginalised African societies."66

In addition, the privatisation of parks and nature reserves, which is regarded by some as a secure form of tenure, may serve to entrench the dispossession of land from the indigenous people, as land becomes a commodity of the rich private land owners. Some of the motivating factors for privatisation of parks and reserves are "increasing the amount of land for nature conservation, relieving the state from the costs involved in protected areas, and marketing products of nature."67 However, this should not blind us to the economic factor, that is, profit generation, which also underlies private interest.68 Pearce notes the following regarding the economic benefits of wildlife, which should alert us to the structures of coloniality:

Economic value is measured in terms of the willingness to pay (WTP) for uses of wildlife. In turn, WTP generally exceeds the price actually paid in the market place: Some people are always willing to pay more than the actual prices (the difference being their "consumer's surplus"), whilst those willing to pay less than the ruling price are excluded from the market. What matters for economic value the summation of the WTPs of different groups, the "total economic value" (TEV).69

It is thus necessary to tread with caution, as the colonial matrix of power, which utilised racial hierarchy to dominate nature and exclude others, is able to survive under economic hierarchy, which continues to subordinate the majority of the indigenous people while economically privileging a few.

Fourth, the colonial legacy over nature must be dealt with. The recent "Rhodes must fall" campaign, which eventually led to the removal of Rhodes' statue from the University of Cape Town, should serve as a reminder that the South African community needs to deal with the colonial legacies when it comes to nature as well. The Kruger National Park, which is the largest game reserve in the country and among the largest in Africa, is a symbol of the colonial legacy imprinted on our continent. No significant attempts have been made to rename the Kruger National Park, and attempts to remove the statues of colonial apartheid figures such as Paul Kruger, Piet Grobler, and James Steven-son-Hamilton, have ended in failure.70 To fail to redefine our landscape is to let the colonial legacy continue to define the relationship between humans and nature in our African context.

In the South African context, dealing with the legacy of colonialism should not be limited to renaming; rather, it also means taking down the colonial boundaries over nature and repairing the damaged landscapes. The removal of fences in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region as initiated by cooperative efforts between states, as well as those led by non-governmental organisations (NGO's), are meant to allow for animal movements across national borders and to allow local communities involvement from across borders.71 However, other countries, such as Uganda, Rwanda, and Malawi, are moving towards fencing as a measure for protecting wildlife from hunting and poaching, and to minimise human-wildlife conflict and human encroachment.72 Durant et alia note that fencing may reduce human-wildlife conflict, but a fence does not necessarily keep people out, as they find their way back through the fence.73 The fences in our context became instruments of criminalisation of the indigenous people. The areas in which people used to freely move, hunt, and graze were turned into areas they had no access to and no rights in.74 The fences have also contributed to the "loss of coping strategies that have enabled communities to coexist with nature."75 Therefore, the restoration process will also have to be a rehabilitation process as humans and other forms of nature have to learn to cope with each other in the interconnected ecosystems.

The "liberty" under the Persian Empire for the decolonial voices remained oppressive and brought about the undesired separation between human beings and nature. The decolonial voices in Yehud imagined that another world is possible-a world in which they and the animals would finally have the liberty they deserved. Our current context like that of the Jews who had the freedom but yet were still under the structures of oppression is one in which the colonial matrix of power continue to shape the relationship between the African people and nature.

D CONCLUSION

In the Isaianic vision, the restoration of creation is not solely anthropocentric; rather, it encompasses the whole community of created beings, which are all inextricably connected in the complex web of life. The marginalised voices in the book of Isaiah imagined that another world is possible even in the midst of their oppression under imperial domination, which threatened not only their livelihoods, but also wildlife. While the marginalised voices in the book of Isaiah imagined the possibility of another world, it remained a vision. In our current context, the structures of coloniality that shape our human relation with nature prompt us to envision the possibility of another world in which nature is also liberated from the structures of coloniality. We cannot imagine ourselves as free as long as nature still remains colonised.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adam, Rachelle. Elephant Treaties: The Colonial Legacy of the Biodiversity Crisis. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2014. [ Links ]

Adams, Jonathan S. and Thomas O. McShane. The Myth of Wild Africa: Conservation without Illusion. Berkeley: University of California, 1996. [ Links ]

Adams, William M. Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in the Third World. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge, 2001. [ Links ]

____. "Nature and the Colonial Mind." Pages 16-50 in Decolonizing Nature: Strategies for Conservation in a Post-Colonial Era. Edited by William M. Adams and Martin Mulligan. London: Earthscan, 2003. [ Links ]

Adams, William M. and Martin Mulligan. "Introduction." Pages 1-15 in Decolonizing Nature: Strategies for Conservation in a Post-colonial Era. Edited by William M. Adams and Martin Mulligan. New York: Earthscan, 2003. [ Links ]

Aune, David E. "Eschatology (Early Christian)." Pages 594-609 in vol. 2 of The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Edited by David N. Ereedman. New York: Doubleday, 1992. [ Links ]

Bankoff, Greg. "Making Parks out of Making Wars: Transnational Nature Conservation and Environmental Diplomacy in the Twenty-First Century." Pages 76-95 in Nation-States and the Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental History. Edited by Erika Marie Bsumek, David Kinkela and Mark Atwood Lawrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Berquist, Jon L. Judaism in Persia's Shadow: A Social Historical Approach. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995. [ Links ]

____. "Postcolonialism and Imperial Motives for Canonization." Semeia 75 (1996): 15-35. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. David Remembered: Kingship and National Identity in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013. [ Links ]

Carr, David. "Reaching for Unity in Isaiah." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 51 (1993): 61-80. [ Links ]

Carruthers, Jane. The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Cataldo, Jeremiah W. Theocratic Yehud? Issues of Government in a Persian Province. New York: T&T Clark, 2009. [ Links ]

Childs, Brevard S. Isaiah. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Coates, Peter. Nature. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. [ Links ]

Durant, Sarah M., Matthew S. Becker, Scott Creel, Sultana Bashir, Amy J. Dickman, Roseline C. Beudels-Jamar, Laly Lichtenfeld, Ray Hilborn, Jake Wall, George Wittemyer, Lkhagvasuren Badamjav, Stephen Blake, Luigi Boitani, Christine Breitenmoser, Femke Broekhuis, David Christianson, Gabriele Cozzi, Tim R. B. Davenport, James Deutsch, Pierre Devillers, Luke Dollar, Stephanie Dolrenry, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, Egil Dröge, Emily FitzHerbert, Charles Foley, Leela Hazzah, J. Grant C. Hopcraft, Dennis Ikanda, Andrew Jacobson, Dereck Joubert, Marcella J. Kelly, James Milanzi, Nicholas Mitchell, Jassiel M'Soka, Maurus Msuha, Thandiwe Mweetwa, Julius Nyahongo, Elias Rosenblatt, Paul Schuette, Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, Anthony R. E. Sinclair, Mark R. Stanley Price, Alexandra Zimmermann and Nathalie Pettorelli. "Developing Fencing Policies for Dryland Ecosystems." Journal of Applied Ecology 52 (2015): 544-551. [ Links ]

Giblet, Rodney J. People and Places of Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Gleason, Kathryn. "Gardens in Preclassical Times." Page 383-385 in vol. 2 of Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Edited by Eric M. Meyers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Gottwald, Norman K. "Social Class and Ideology in Isaiah 40-55: An Eagletonian Reading." Pages 43-57 in Ideological Criticism of Biblical Texts. Edited by David Jobling and Tina Pippin. Semeia 59. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Grove, Richard H. Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, Ramon. "The Epistemic De-colonial Turn." Cultural Studies 21/2-3 (2007): 211-223. [ Links ]

Henze, Matthias H. The Madness of King Nebuchadnezzar: The Ancient Near Eastern Origins and Early History of Interpretation of Daniel 4. Leiden: Brill, 1999. [ Links ]

Knudsen, Are. "Conservation and Controversy in the Karakoram: Khunjerab National Park, Pakistan." Journal of Political Ecology 56 (1999): 1-30. Cited 30 September 2015. Online: http://jpe.library.arizona.edu/volume_6/Knudsen99.pdf. [ Links ]

Langholz, Jeffrey A. and James P. Lassoie. "Perils and Promise of Privately Owned Protected Areas." Bioscience 51 (2001): 1079-1085. [ Links ]

Lewellyn-Jones, Lloyd. King and Court in Ancient Persia 550-331 B.c.E. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. "On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept." Cultural Studies 21/2-3 (2007): 240-270. [ Links ]

Marsh, George Perkins. Man and Wilderness. New York: Charles Scribner, 1864. [ Links ]

Masenya (Ngwan'a Mphahlele), Madipoane and Hulisani Ramantswana. "Lupfumo lu Mavuni (Wealth is in the Land): In Search of the Promised Land (cf. Exod 3-4) in the Post-Colonial, Post-Apartheid South Africa." Journal of Theology of Southern Africa 151 (2015): 97-116. [ Links ]

Mathews, Claire R. Defending Zion: Edom's Desolation and Jacob's Restoration (Isaiah 34-35). Berlin: de Gruyter, 1995. [ Links ]

Mavhunga, Clapperton Chakanetsa. "Seeing the National Park from Outside It: On an African Epistemology of Nature." Pages 53-60 in The Edges of Environmental History: Honouring Jane Carruthers. Rachel Carson Center Perspectives 2014/1. Edited by Christof Mauch and Libby Robin. Cited 23 September 2015. Online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/85847. [ Links ]

Mazrui, Ali A. "Preface: Black Berlin and the Curse of Fragmentation: From Bismarck to Barack." Pages v-xii in The Curse of Berlin: Africa after the Cold War. Edited by Adekeye Adebajo. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Meskell, Lynn. "The Nature of Culture in Kruger National Park." Pages 89-112 in Cosmopolitan Archaeologies. Edited by Lynn Meskell. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Mignolo, Walter D. "Prophets Facing Sidewise: The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference." Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy 19/1 (2006): 111-127. [ Links ]

Pearce, David. "An Economic Overview of Wildlife and Alternative Land Uses." Centre for Social and Economic Research Working Paper GEC 97-05, 1997. 31 Pages. Cited 23 September 2015. Online: http://www.cserge.ac.uk/sites/default/files/gec_l997_05.pdf. [ Links ].

Plutarch, Moralia. With an English Translated by F. C. Babbitt. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931 [repr. [ Links ] 1968].

Power, Kerith and Margaret Somerville. "The Fence as Technology of (Post-)Colonial Childhood in Contemporary Australia." Pages 63-78 in Unsettling the Colonial Places and Spaces of Early Childhood Education. Edited by Veronica Pacini- Ketchabaw. New York: Routledge, 2015. [ Links ]

Ramutsindela, Maano. Parks and People in Postcolonial Societies: Experiences in Southern Africa. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004. [ Links ]

SADC. "The Phakalane Declaration." 2012. No Pages. Cited 23 September 2015. Online: http://www.wcs-ahead.org/phakalane_declaration.html. [ Links ]

Schipper, Jeremy. "Hezekiah, Manasseh, and Dynastic or Transgenerational Punishment." Pages 81-108 in Sounding in Kings: Perspectives and Methods in Contemporary Scholarship. Edited by Mark Leuchter and Klaus-Peter Adam. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Schramm, Brooks. The Opponents of Third Isaiah: Reconstructing the Cultic History of the Restoration. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Seitz, Christopher R. Word without End: The Old Testament as Abiding Theological Witness. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Shiva, Vandana. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. Boston: South End Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Smith, Morton. "II Isaiah and the Persians." Journal of American Oriental Society 83 (1963): 415-421. [ Links ]

Somers, Michael J. and Matthew W. Hayward. Fencing for Conservation: Restriction of Evolutionary Potential or a Riposte to Threatening Processes! New York: Springer, 2012. [ Links ]

Sweeney, Marvin A. Isaiah 1-39: With an Introduction to the Prophetic Literature. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996. [ Links ]

Trotter, James M. Reading Hosea in Achaemenid Yehud. London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. [ Links ]

Tull, Patricia K. "One Book, Many Voices: Conceiving of Isaiah's Polyphonic Message." Pages 279-314 in "As Those Who Are Taught": The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL. Edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull. Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 27. Leiden: Brill, 2006. [ Links ]

Van Aarde, Rudi J. and Tim P. Jackson. "Megaparks for Metapopulations: Addressing the Causes of Locally High Elephant Numbers in Southern Africa." Biological Conservation 134 (2007): 289-297. [ Links ]

Van Andel, Jelte and James Aronson. "Getting Started." Pages 3-8 in Restoration Ecology: The New Frontier. 2nd edition. Edited by Jelte van Andel and James Aronson. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. [ Links ]

Von Rad, Gerhard. The Theology of Israel's Prophetic Tradition. Volume 2 of Old Testament Theology. Translated by David M. G Stalker. New York: Harper & Row, 1965. [ Links ]

Wagner, Thomas. "From Salvation to Doom: Isaiah's Message in the Hezekiah Story." Pages 92-103 in Prophecy and Prophets in Stories: Papers Read at the Fifth Meeting of the Edinburgh Prophecy Network, Utrecht, October 2013. Edited by Bob Becking and Hans M. Barstad. Leiden: Brill, 2015. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, Moshe. "Protest against Imperialism in Ancient Israelite Prophecy." Pages 169-182 in The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations. Edited by Shmuel N. Eisenstadt. State University of New York Series in New Eastern Studies. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986. [ Links ]

West, Paige, James Igoe and Dan Brockington. "Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas." Annual Review of Anthropology 35 (2006): 251-277. [ Links ]

Westermann, Claus. Isaiah 40-66: A Commentary. Translated by David M. G. Stalker. London: SCM Press, 1969. [ Links ]

Wild Conservation Society (WCS). "As the Fences Come Down: Emerging Concerns in Transfrontier Conservation Areas." 2008. 12 Pages. Cited 23 September 2015. Online; http://www.wcs-ahead.org/documents/asthefencescomedown.pdf. [ Links ]

Williamson, Hugh G. M. Variation on a Theme: King, Messiah and Servant in the Book of Isaiah. Carlisle: Paternoster, 1998. [ Links ]

Williamson, Paul R. Sealed with an Oath: Covenant in God's Unfolding Purpose. New Studies in Biblical Theology 23. Nottingham: Apollos, 2007. [ Links ]

Yee, Gale A. "Postcolonial Biblical Criticism." Pages 193-234 in Methods for Exodus. Edited by Thomas B. Dozeman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Xenophon. Cyropaedia. With an English Translation by Walter Miller. 2 Volumes. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1914 [repr. [ Links ] 1960].

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Hulisani Ramantswana

University of South Africa

Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies

P. O. Box 392, UNISA, 0003

Email: ramanh@unisa.ac.za or hramantswana@hotmail.com

Article submitted: 8 October 2015

Accepted: 2 November 2015

1 Nelson Maldonado-Torres, "On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept," CSt 21/2-3 (2007): 240-270.

2 Maldonado-Torres, "On the Coloniality," 243.

3 See William M. Adams and Martin Mulligan, "Introduction," in Decolonizing Nature: Strategies for Conservation in a Post-colonial Era (ed. William M. Adams and Martin Mulligan; New York: Earthscan, 2003).

4 Vandana Shiva, Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge (Boston: South End Press, 1997).

5 Ali A. Mazrui, "Preface: Black Berlin and the Curse of Fragmentation: From Bismarck to Barack," in The Curse of Berlin: Africa after the Cold War (ed. Adekeye Adebajo; Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2010), v-xii, xii.

6 Kerith Power and Margaret Somerville, "The Fence as Technology of (Post-)Colonial Childhood in Contemporary Australia," in Unsettling the Colonial Places and Spaces of Early Childhood Education (ed. Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw; New York: Routledge, 2015), 63-78, 63.

7 Grosfoguel rightly argues: "One of the most powerful myths of the twentieth century was the notion that the elimination of the colonial administration amounted to the decolonization of the world. This led to the myth of a 'postcolonial' world. The heterogeneous and multiple global structures put in place over a period of 450 years did not evaporate with the juridical-political decolonization of the periphery over the past 50 years. We continue to live under the same 'colonial power matrix.' With the juridical administrative decolonization we moved from a period of 'global colonialism' to the current period of 'global coloniality.' Although 'colonialism administrations' have been entirely eradicated and the majority of the periphery is politically organized into independent states, non-European people are still under crude exploitation and domination. The old colonial hierarchies of European versus non Europeans remain in place and are entangled with the 'international division of labour' and accumulation of capital at a world-scale." See Ramón Grosfoguel, "The Epistemic De-colonial Turn," Cultural Studies 21/2-3 (2007): 211-223, 219.

8 William M. Adams, "Nature and the Colonial Mind," in Decolonising Nature: Strategies for Conservation in a Post-colonial Era (ed. William M. Adams and Martin Mulligan; London: Earthscan, 2003), 16-50, 22.

9 Walter D. Mignolo, "Prophets Facing Sidewise: The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference," SocEp 19/1 (2006): 111-127, 114.

10 George Perkins Marsh, Man and Wilderness (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 36.

11 Adams, "Nature," 33.

12 Vultures, secretary-birds, owls, rhinoceros-birds or beef-eaters, giraffes, gorillas, chimpanzees, mountain zebras, wild asses, white-tailed gnus, elands, little Liberian hippopotamuses.

13 Elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, zebras, buffaloes, ibexes, chevrotains, antelopes and gazelles.

14 Same as in category 2.

15 Animals listed in category 1 and 2, plus pigs, colobi, and fur-monkeys, aardvarks, dugongs, manatees, small cats, servals, chital, jackals, aardwolves, small monkeys, ostriches, marabous, egrets, bustards, francolins, guinea-fowl, "game" birds, large tortoises.

16 Lions, leopards, hyenas, African hunting dogs, otters, baboons and harmful monkeys, crocodiles, poisonous snakes, pythons, large birds, but not those in category 1.

17 See Rachelle Adam, Elephant Treaties: The Colonial Legacy of the Biodiversity Crisis (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2014).

18 Maano Ramutsindela, Parks and People in Postcolonial Societies: Experiences in Southern Africa (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004), 2.

19 Adam, Elephant Treaties, 5.

20 William M. Adams, Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in the Third World (2nd ed.; New York: Routledge, 2001), 26.

21 Richard H. Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 15. In the South African context, with concern for the depletion of the forest, the Cape Colony introduced the following conservation legislation in the 19th century regarding preservation of open land in the vicinity of Cape Town (1846), preservation of the forest (1859), and preservation of game (1886; Adams, Green Development, 26.).

22 Adam, Elephant Treaty, 5.

23 See Jonathan S. Adams and Thomas O. McShane, The Myth of Wild Africa: Conservation without Illusion (Berkeley; University of California), 1996.

24 Greg Bankoff, "Making Parks out of Making Wars: Transnational Nature Conservation and Environmental Diplomacy in the Twenty-First Century," in Nation-States and the Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental History (ed. Erika Marie Bsumek, David Kinkela and Mark Atwood Lawrence; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 82-83.

25 See Lynn Meskell, "The Nature of Culture in Kruger National Park," in Cosmopolitan Archaeologies (ed. Lynn Meskell; Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 92.

26 Rodney J. Giblet, People and Places of Nature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 164.

27 Brevard S. Childs, Isaiah (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 102104.

28 See Marvin A. Sweeney, Isaiah 1-39: With an Introduction to the Prophetic Literature (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 51.

29 Patricia K. Tull, "One Book, Many Voices: Conceiving of Isaiah's Polyphonic Message," in "As Those Who Are Taught": The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL (ed. Claire M. McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull; SBLSymS 27; Leiden: Brill, 2006), 279-314, 313. Several other scholars also argue for a multiplicity of voices. Carr states, "It is clear that not just one but several redactors have introduced their macrostructural conceptions into the book of Isaiah." See David Carr, "Reaching for Unity in Isaiah," JSOT 51 (1993): 61-80, 77. Similarly, Mathews argues that the book of Isaiah "is a product of a multiplicity of voices adding, generation by generation, to an original body of 'authentic' Isaianic prophecy, as the prophecy was reactualized, supplemented, and reinterpreted . . . a kind of prophetic chorus-and sometimes cacophony." See Claire R. Mathews, Defending Zion: Edom's Desolation and Jacob's Restoration (Isaiah 34-35) (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1995), 156.

30 Morton Smith, "II Isaiah and the Persians," JAOS 83 (1963): 415-421. For Gottwald Isa 40-55 served the agenda of the elites who aligned themselves with the Persians and in so doing reassigned the Davidic functions to the Persians and to themselves. See Norman K. Gottwald, "Social Class and Ideology in Isaiah 40-55: An Eagletonian Reading," in Ideological Criticism of Biblical Texts (ed. David Jobling and Tina Pippin; Semeia 59; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992), 43-57.

31 2 Chr 36:22-23.

32 Ezra 1; 3; 4; 5; 6.

33 Dan 1:21; 6:28; 10:1.

34 "Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will be with child ( ) and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel. He will eat curds and honey when he knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right" (niv).

) and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel. He will eat curds and honey when he knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right" (niv).

35 "For to us a child ( ) is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and peace there will be no end. He will reign on David's throne and over his kingdom, establishing and upholding it with justice and righteousness from that time on and forever. The zeal of the Lord Almighty will accomplish this" (niv).

) is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and peace there will be no end. He will reign on David's throne and over his kingdom, establishing and upholding it with justice and righteousness from that time on and forever. The zeal of the Lord Almighty will accomplish this" (niv).

36 Thomas Wagner, "From Salvation to Doom: Isaiah's Message in the Hezekiah Story," in Prophecy and Prophets in Stories: Papers Read at the Fifth Meeting of the Edinburgh Prophecy Network, Utrecht, October 2013 (ed. Bob Becking and Hans M. Barstad; Leiden: Brill, 2015), 92-103, 100.

37 Jon L. Berquist, "Postcolonialism and Imperial Motives for Canonization," Semeial5 (1996): 15-35.

38 In Isa 38:6, Hezekiah and the city of Jerusalem are promised deliverance from the Assyrian. It should be noted; however, that there are a number of promises that the exiles will return from Assyria (Isa 11:11, 16; 27:13).

39 "See, I will stir up against them the Medes, who do not care for silver and have no delight in gold. Their bows will strike down the young men; they will have no mercy on infants nor will they look with compassion on children. Babylon, the jewel of kingdoms, the glory of the Babylonians' pride, will be overthrown by God like Sodom and Gomorrah. She will never be inhabited or lived in through all generations; no Arab will pitch his tent there, no shepherd will rest his flocks there. But desert creatures will lie there, jackals will fill her houses; there the owls will dwell, and there the wild goats will leap about. Hyenas will howl in her strongholds, jackals in her luxurious palaces. Her time is at hand, and her days will not be prolonged" (Isa 13:1722, Niv). Compare with Jer 51, which also prophesies the destruction of Babylon.

40 Moshe Weinfeld, "Protest Against Imperialism in Ancient Israelite Prophecy," in The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations (ed. Shmuel N. Eisenstadt; SUNY SNES; Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986), 169-182, 181. For Weinfeld the anti-imperial prophetic tradition began with the rise of the Assyrian empire and is evident in prophetic books such as Nahum, Habakkuk, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Micah.

41 Joseph Blenkinsopp, David Remembered: Kingship and National Identity in Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 70. Trotter states, "The future hope of Deutero-Isaiah . . . did not lie in the restoration of the Davidic monarchy. In fact, such an idea is never mentioned in Isaiah 40-55. Rather, Deutero-Isaiah saw the Persian Empire, and Cyrus II, in particular, as the tool of Yahweh for the future of the people (Isa. 44.28; 45.1-14). 'Deutero-Isaiah was not pro-nationalist or pro-Davidic; he was pro-Persian, with the argument that the fortunes of the Babylonian Jews, if not all Jews, would be best served under Persian rule.'" See James M. Trotter, Reading Hosea in Achaemenid Yehud (London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 100. See also Jon L. Berquist, Judaism in Persia's Shadow: A Social Historical Approach (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995), 31.

42 The stories of Daniel and Esther also have parallels with the Joseph story in Gen 37-50. Although the stories all reflect the experience of Israelites/Jews in diaspora and Jews attaining high positions, they have different ideologies underlying them.

43 See Gale A. Yee, "Postcolonial Biblical Criticism," in Methods for Exodus (ed. Thomas B. Dozeman; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 193-234, 214215.

44 Jeremiah W. Cataldo, A Theocratic Yehud? Issues of Government in a Persian Province (New York: T&T Clark, 2009), 37. Cataldo further notes, "The imperial government's response provides a counterargument to proposals of provincial self-governance. That temples were affected by punishments meted out shows they were not outside imperial jurisdiction or control; they were permitted in societies as long as the society demonstrated its loyalty to the empire." Cataldo, Theocratic Yehud, 37.

45 Cataldo, Theocratic Yehud, 39-40.

46 Jeremy Schipper, "Hezekiah, Manasseh, and Dynastic or Transgenerational Punishment," in Sounding in Kings: Perspectives and Methods in Contemporary Scholarship (ed. Mark Leuchter and Klaus-Peter Adam; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010), 81-108, 89.

47 See Gerhard von Rad, The Theology of Israel's Prophetic Tradition (vol. 2 of Old Testament Theology; trans. David M. G Stalker; 2 vols.; New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 46, 240, 271, 325; Claus Westermann, Isaiah 40-66: A Commentary (trans. D. M. G. Stalker; OTL; London: SCM Press, 1969), 284-285; Hugh G. M. Williamson, Variation on a Theme: King, Messiah and Servant in the Book of Isaiah (Carlisle: Paternoster, 1998), 117-119.

48 For arguments against the démocratisation of the Davidic promises, see Christopher R. Seitz, Word Without End: The Old Testament as Abiding Theological Witness (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 150-167; Paul R. Williamson, Sealed with an Oath: Covenant in God's Unfolding Purpose (NSBT 23; Nottingham: Apollos, 2007), 161162.

49 Brooks Schramm, The Opponents of Third Isaiah: Reconstructing the Cultic History of the Restoration (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 66.

50 As translated by the rsv.

51 See Dan 4. In the Sumerian "royal hymns, Ishmedagan solemnly proclaims to be a giant tree with strong roots and outstretched branches, providing a 'sweet shade' for all of Sumer." Matthias H. Henze, The Madness of King Nebuchadnezzar: The Ancient Near Eastern Origins and Early History of Interpretation of Daniel 4 (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 81.

52 The rise of Cyrus did not quench the hope for the restoration of the Davidic monarchy; that hope continued even under the Persian Empire. The salvation envisioned by the voices of protest against the Persian Empire is one that comes not from the hegemonic side of power, but from the side of the powerless, symbolised by a child or by a tender shoot rising from the stump of David.

53 In Isa 6, the stump is the "holy seed," but this holy seed is not specifically identified.

54 As Gleason points out, "kings boast of large parts of cities devoted to these parks, of great irrigation works that feed them, and of the distant lands from which the plants and animals are gathered. Tiglath-Pileser I (1114-1076 B.C.E.) created a combined zoological part and arboretum of exotic animals and trees. Ashurnsirpal II (883-859 B.C.E.)created a garden or park at Nimrud (Kalhu) by diverting water from the Upper Zab River through a rock-cut channel for his impressive collection of foreign plants and animals. Sennacherib (704-681 B.C.E)makes a similar claim for Nineveh. Parks are beautifully represented on the reliefs from Sargon IPs (721-705 B.C.E)palace at Khorsabad, in which a variety of trees and a small pavilion with proto-Doric columns are depicted. Other reliefs depict lion hunts and falconry in the parks. A clay tablet from Babylon names and locates vegetables and herbs in the garden of Merodach-Baladan II (721-710 B.C.E). In the palace reliefs of Ashurbanipal, the garden symbolizes the abundance and pleasures of peace after bravery in battle." Kathryn Gleason, "Gardens in Preclassical Times," OEANE 2:383.

55 "The earliest reference to a Persian-style park and garden comes in the form of a Babylonian text dating to regnal year 5 Cyrus II which speaks of pardesu . . ., but it is during the reign of Darius I that more regular references to paradeisoi are found in the Persepolis texts." See Lloyd Lewellyn-Jones, King and Court in Ancient Persia 550-331 B.c.E. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 92.

56 David E. Aune, "Eschatology (Early Christian)," ABD 2:594-595.

57 See Ramutsindela, Parks and People, 24.

58 Peter Coates, Nature (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 18.

59 Jelte van Andel and James Aronson, "Getting Started" in Restoration Ecology: The New Frontier (ed. Jelte van Andel and James Aronson; 2nd ed.; Oxford: Wiley -Blackwell, 2012), 4-5.

60 Van Andel and Aronson, "Getting Started," 4.

61 Ramutsindela, Parks and People, 51-52. As Carruthers also notes, "On the other side of the fence from the relatively intact protected ecosystem with its lush grassland and abundant wild life, live impoverished communities, desperate for land and for access to natural resources." Jane Carruthers, The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1995), 89.

62 See Madipoane Masenya (Ngwan'a Mphahlele) and Hulisani Ramantswana, "Lupfumo lu Mavuni (Wealth is in the Land): In Search of the Promised Land (cf. Exod 3-4) in the Post-Colonial, Post-Apartheid South Africa," JTSA 151 (2015): 97116.

63 Paige West, James Igoe and Dan Brockington, "Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas," ARA 35 (2006): 251-277, 256.

64 Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, "Seeing the National Park from Outside It: On an African Epistemology of Nature" in The Edges of Environmental History: Honouring Jane Carruthers (RCCP 2014/1; ed. Christof Mauch and Libby Robin), 53-60, 53. Cited 23 September 2015. Online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/85847.

65 Ramutsindela, Parks and People, 66.

66 Ramutsindela, Parks and People, 55-67.

67 Ramutsindela, Parks and People, 83.

68 Jeffrey A. Langholz and James P. Lassoie, "Perils and Promise of Privately Owned Protected Areas," Bioscience 51 (2001): 1079-1085.

69 David Pearce, "An Economic Overview of Wildlife and Alternative Land Uses," (CSERGE Working Paper GEC 97-05, 1997), 31 pages. Cited 23 September 2015. Online: http://www.cserge.ac.uk/sites/default/files/gec_1997_05.pdf.

70 Ramutsindela, Parks and People, 67.

71 See SADC, "The Phakalane Declaration," (2012), n.p. [cited 23 September 2015]. Online: http://www.wcs-ahead.org/phakalane_declaration.html; Rudi J. van Aarde and Tim P. Jackson, "Megaparks for Metapopulations: Addressing the Causes of Locally High Elephant Numbers in Southern Africa," BioCon 134 (2007): 289-297; Wild Conservation Society, "As the Fences Come Down: Emerging Concerns in Lransfrontier Conservation Areas," (2008), 12 pages. Cited 23 September 2015. Online: http://www.wcs-ahead.org/documents/asthefencescomedown.pdf.

72 Michael J. Somers and Matthew W. Hay ward, Fencing for Conservation: Restriction of Evolutionary Potential or a Riposte to Threatening Processes ? (New York: Springer, 2012); Sarah M. Durant et al., "Developing Fencing Policies for Dryland Ecosystems," JAEc 52 (2015): 544-551, 545.

73 Durant et al., "Developing Fencing Policies," 547.

74 Are Knudsen, "Conservation and Controversy in the Karakoram: Khunjerab National Park, Pakistan," JPEc 56 (1999): 1-30. Cited 30 September 2015. Online: http://jpe.library.arizona.edu/volume_6/Knudsen99.pdf.

75 Durant et al., "Developing Fencing Policies," 547.