Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.27 n.3 Pretoria 2014

The compositional/narrative structure of Judith: a Greimassian perspective

Risimati S. Hobyane

North-West University

ABSTRACT

The compositional structure of the Judith narrative has evoked the reaction of many OT scholars who focus on Judith. Some scholars allege that part one is flatter in style and that the book is unbalanced in structure. Other scholars2 have made insightful contributions against these allegations on Judith. This article endeavours to bring a unique contribution against these allegations, by applying narrative analysis to the narratives, as informed by the Greimassian semiotic approach. The appeal here is to discover how these allegations robbed Judith of the recognition it deserves as a brilliant story. The application of a narra tive analysis based on the Greimassian approach reveals that Judith is a well-structured and balanced story containing a noticeable transformation. Subsequently, this article concludes that the two parts of the story are complementary to each other rather than imbalanced as claimed.

Key words: Judith, Greimas, narrative analysis, structure

A INTRODUCTION

Many scholars3 have made significant contributions to the interpretation of the story of Judith.4 Jordaan5 concedes that at first glance, the Judith narrative seems to be just another story with a sad beginning and a good ending. How-ever, one does not have to read long before realising that Judith is more com-plicated than it may seem at first glance. One of the most debated aspects of the story is its alleged poor compositional structure and style. This allegation trig-gered the interest of some Judith scholars. To give an example: the study of Toni Craven6 and her doctoral thesis7 deserves some recognition in this regard.

Through her literary/rhetorical study of Judith, Craven shows that the narrative of Judith is both "balanced and proportioned."8 She further concludes, after analysing the story rhetorically, that there are definite, intentional connections between the two sections of the story on the level of both thematics and vocabulary. To my mind, Toni Craven's work is the only research that intensively tackles the alleged poor compositional structure and style of Judith, Other than Craven's work, a number of articles have been published that address various issues that arise regarding the narrative. To mention but a few: Branch and Jor-daan9 investigated the significance of secondary characters in Judith, Efthimi-adis-Keith10 contributed on the possible Egyptian origin for the Book of Judith, and she further published a paper in which she investigated the links between the feminist ethics of care, justice, autonomy and the self in relation to certain practices in feminist biblical interpretation, focusing on Judith,11 Jordaan and Hobyane12 also did a literary study on ethics, gender and the rhetoric of the Judith narrative and Efthimiadis-Keith13 has shown that there is currently a lively interest in studying Judith from a feminist point of view. Lastly, Jor-daan14 interprets Judith as a therapeutic narrative, arguing that the function of the narrative is to advocate a more equal society during times of war. These contributions proved that there is much that the text of Judith can offer.

B PROBLEM STATEMENT

While appreciating the contributions made by the scholars mentioned above, Toni Craven's in particular, the contention here is that it appears that no other scholar working on Judith has ever focused on the alleged poor compositional structure and style of Judith by using a Greimassian approach. Before the study of Craven, scholars have reacted to the organisational/compositional structure of the two parts of Judith in a variety of ways. For many, the Judith narrative is imbalanced, as it consists of two unequal parts, chs. 1-7 and 8-16. This per-spective is held by scholars like, Alonso-Schökel, Dancy and Craghan as referenced in Efthimiadis-Keith.15 Moreover, Cowley as referenced by Craven,16 puts forward that the book of Judith is "out of proportion" because of an overly long introduction (1-7) to the "story proper" (8-16). Dancy also, as cited by Efthimiadis-Keith,17 regards Part 1 as "duller in thought and flatter in style," because it fails to provide a historical setting with the "economy" and "accu-racy a modern reader looks for."

The central hypothesis here is that the application of the narrative analysis of the Greimassian approach reveals not only that Judith is a well-structured and balanced story, but also that Judith is a story with a noticeable transformation in it. The study of transformation will further help to reveal the relation between the initial and the final sequence in Judith, This article aims at bringing a new contribution by analysing the two parts of the story and further establishes the complementary significance of one part to the other.

This is a unique contribution in that instead of taking a historical critical route of analysing narrative texts, it employs a Greimassian semiotic approach which accepts, appreciates and analyses a story as a whole without discrediting any of its parts. To the researcher's knowledge, Judith has not been analysed this way in many instances.

C METHODOLOGICAL APPRAOCH

Greimassian semiotics is a general theory of meaning. According to Kanonge18, this theory consists of exploring semiotic objects at three different levels of analysis: the figurative, narrative and thematic. This article focuses on the second of the three analyses that form part of the Greimassian approach, that is, the narrative analysis. The narrative analysis examines the organisation of a text as discourse. It helps to reveal different functions of actants and tracks the course of the subject across the narrative from the beginning to the end of the story. According to Martin and Ringham,19 the tools for investigation here are the actantial model (also called actantial narrative schema) and the narrative syntax. Aspects of importance addressed in relation to this level of analysis are: the structure of the story (the relation between the initial and final state of the narrative, in particular), the actantial model and canonical narrative schema.

This article only focuses on the aspects which contribute to addressing the alleged compositional imbalance of the story, namely the structure of the story and the relation between the initial and final state of the narrative.

D THE COMPOSITIONAL STRUCTURE OF JUDITH

1 The Structure of Judith

This section focuses on establishing the position of this article concerning the alleged questionable compositional relation between the two parts of the book of Judith (Jdt 1-7 and 8-16), before embarking on a detailed narrative analysis of the book. This is important because the Greimassian semiotic analysis treats the story as a structural whole. In summary, the two parts of the Judith narrative can be divided as follows:20

Chapters 1-7 (Part 1)

1 Introduction to Nebuchadnezzar and his campaigns against Arphaxad (1:1-16)

2 Nebuchadnezzar commissions Holofernes to take vengeance on the diso-bedient nations (2:1-13)

3 Development

A The campaign against the disobedient nations; the people surrender(2:14-3:10)

B Israel hears and is "greatly terrified"; Joachim orders war preparations (4:1-15)

C Holofernes talks with Achior. Achior is expelled from the Assyrian camp (5:1-6:11)

C' Achior is received into Bethulia; he talks with the people of Israel (6:12-21)

B' Holofernes orders war preparations; Israel sees and is "greatly terrified" (7:1-5)

A' The campaign against Bethulia; the people want to surrender (7:6-32)

Chapters 8-16 (Part 2)

A Introduction to Judith (8:1-8)

B Judith plans to save Israel (8:9-10:8)

C Judith and her maid leave Bethulia (10:9-10)

D Judith conquers Holofernes (10:11-13:10a)

C' Judith and her maid return to Bethulia (13:10b-11)

B' Judith plans the destruction of Israel's enemy (13:12-16:20

A' Conclusion of Judith (16:21-25)

As shown above and mentioned before, Judith is a narrative in two parts. Part I begins with successful campaigns by Nebuchadnezzar and his commission to his army general, Holofernes. Holofernes is ordered to advance Nebuchadnezzar's ambition of having all the people and nations worship him (Nebuchadnezzar) as god. He is commanded to destroy the nations - including Israel, who refuses to comply with Nebuchadnezzar's command. The story continues with the description of the threat posed by Holofernes' army to the city of Bethulia, Jerusalem and the temple.

Part II deals with the introduction of the protagonist, Judith, and her plan to save Israel. Harrington21 asserts that this part reveals how God saves Israel through the hand of Judith.

In summary, the first part of the narrative describes Israel facing a crisis due to the ambitious plan of Nebuchadnezzar to control the entire existing world (1-7). Israel lacks courage and urges her leaders to surrender. The second part of the book (8:1-16:25) is the story of how God saves Israel through the hand of a woman called Judith, as Jordaan and Hobyane22 asserts.

As already alluded to, biblical scholars have reacted to the two parts of Judith in a variety of ways. For many, the Judith narrative is imbalanced as it consists of two unequal parts, chs. 1-7 and 8-16 (cf. Alonso-Schökel, Dancy, and Craghan, as referenced in Efthimiadis-Keith).23 Winter as cited by Moore,24 is kinder in criticising by suggesting that "[t]he Judith narrative is slightly disproportionate in its parts." This article is of the opinion that the views of Dancy, Winter, Cowley and Craghan (mentioned above) have, for many years, robbed Judith of the recognition of its value and brilliance as a narrative with a transformational character. However, following Craven's25 rhetorical criticism of Judith, Efthimiadis-Keith26 observes that most modem scholarship acknowledges the necessity of both "parts" or sections of Judith and the structural integrity of the text as we have it today. De Silva27 also acknowledges the structural brilliance of the Judith narrative, noting that "the careful structuring of this balanced work attests to the literary artistry of the author."

Nickelsburg28 concurs with De Silva that Judith is a literary work of considerable artistic merit. He argues that chs. 1-7 actually constitute the first half of a carefully crafted literary diptych, in which the second part (chs. 8-16) resolves events and issues presented in the first part. Craven's work (see 1.3.1) has made an insightful contribution to the alleged structural imbalance of Judith, It establishes that both parts exhibit highly refined and carefully crafted architectural patterns that contribute to the meaning of the story. The study of Craven29 further shows that to excerpt a few verses or chapters from Part II, for example about the deed of the woman Judith, is to do violence to the whole of the story.

In summary, this article observes that Judith scholars such as Moore, Harrington, Nickelsburg, Efthimiadis-Keith and De Silva, as cited above, generally agree that the story of Judith comprises two main parts, traditionally named Part I and II, which are not "disproportionate" or "imbalanced," as some scholars would suggest, but are nonetheless fairly complementary to each other. The present study considers the first part of the story as a necessary preparation for the second, without which the act of Judith itself in Part II would be without context. Therefore, the acknowledgement of the necessity of these two parts as complementary halves is indispensable. This article observes further that it is unfortunate that many of the scholars mentioned above stopped their contribution after establishing the complementary nature of the two parts of Judith, They do not substantiate it by going into other aspects or further details of the story. Following the Greimassian semiotic approach, this article intends to investigate the relation between the initial and the final sequences in Judith, as they add value in the compositional brilliance of the story.

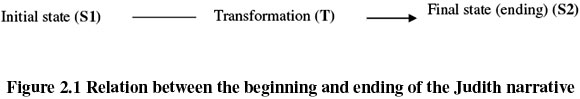

2 The Initial and Final Sequence in Judith

According to Kanonge30 the primary condition for the existence of narrative structures is transformation. Everaert-Desmedt31 states that there is no way to think of a narrative starting and ending without change. Martin and Ringham32 support this idea, arguing that "in order for there to be any story there must be a transformation." According to Greimas,33 transformation accounts for what happens when a narrative progresses from one state to the other or includes a categorical movement from one state (initial state) to another (final state).

According to Kanonge,34 narrative transformations generally occur in terms of "lack (state of disjunction) versus settling of lack (state of conjunction)" or "mission given versus mission accomplished." The researcher's extensive reading of Judith has shown that Judith is fertile ground for this type of investigation. Judith's compositional structure calls for an in-depth analysis of this matter.

This investigation, of the relation between the initial and the final sequence in Judith proceeds from the point of departure that Judith is an orderly crafted literary unit that comprises two complementary parts (Part I and Part II). This study postulates that the initial and final sequences introduce and conclude the relationship between the main opposition in the story. The main opposition in Judith is between the Israelites (represented by Judith) and the Assyrians (represented by Holofernes). In addition, the relation or opposition of desires in the story is well-covered in both parts of the narrative.

The study of initial and final sequence is another way of reading Judith and realising its compositional brilliance and this may help a reader to read this narrative with a different focus. The focus here is on the unfolding of the story, starting from the threat to the existence of Jewish people/religion posed by the Assyrian army to the preservation of the Jewish people/religion. According to Martin and Ringham,35 the general passage from one state of affairs to another can be illustrated on a semantic axis as follows:

The situation in SI introduces the problem (lack/mission to be accomplished) to be addressed, while S2 presents the settlement of the lack/mission accomplished. The SI and S2 states represent Part I and Part II of the story respectively. The situation in T is the critical point of transformation in the story. One of the main problems Judith seeks to address is to help the Jewish religion, under the leadership of the ἄρχοντες (governors) and πρεσβυτέροι (elders), to survive the threat of extinction by the Assyrians. Therefore, the situation in S1 is that of the Jewish religion in crisis, while the situation in S2 is that of the Jewish religion surviving/having survived extinction.

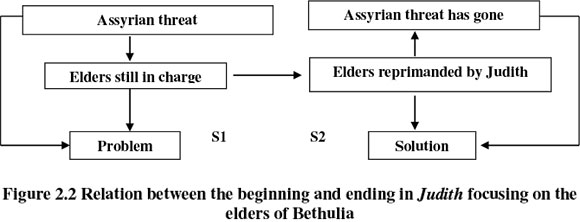

The narrative indicates in 7:31 that the elders are about to surrender the city just before the introduction of the protagonist, Judith. Therefore, this article observes that the role played by the elders and governors in S1 is significant and constitutes a major compositional part of the narrative. Therefore, this aspect deserves brief attention and illustration.

Thus, a reading focused on the elders/governors of Bethulia can be pre-sented as part of the structure in the following manner:

The schematic representation (Fig. 2.2) on the one hand shows that the Jewish religion under the leadership of the elders experiences problems. It seems that the elders in S1 do not have a firm vision for the survival of the Jewish religion. However, the representation shows on the other hand that after Judith reprimands the elders in S2, the Jewish people have hope for survival.

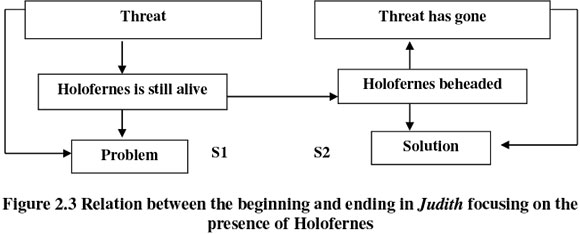

The role of the Bethulian elders in their state of fear and uncertainty can thus contribute to the destruction of the city and the extinction of the Jewish religion. However, it must be indicated that the elders and governors are not the only contributors to the situation in S1. The main contributor of the situation in S1 is in the person of Holofernes. Holofernes incites fear among the Jews by propagating that Nebuchadnezzar should be worshipped as the only god by all the people, including the Jews.

Similarly, a reading focused on the presence of Holofernes (Assyrian threat) can be presented as part of the structure in the following manner:

Fig. 2.3 illustrates how the existence of Holofernes in the Assyrian camp constantly bears a threat to the nation of Israel, perhaps of possible extinction. Holofernes is indeed a real threat to the existence of the Jews and their religion. This is clear because, after his death, Israel suddenly experiences victory, peace and stability. Jerusalem and the temple (Jewish religion) are finally safe. The Jewish religion is no longer in crisis; it has survived the threat of extinction. This development is well-covered by both parts of the story.

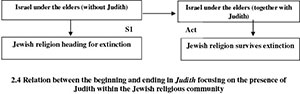

In summary, from the perspective of the Jewish religion and the role played by Judith within the Jewish religious community (Judith versus the elders/governors) the transformation can be schematically presented as follows:

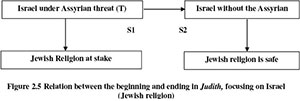

Fig. 2.4 emphasises the role played by Judith (the subject of doing) in saving the Jewish religion. The schematic representation further shows that the presence of the Elders/governors alone, in S1, could not save the religion without Judith's brave involvement in S2. From the perspective of the Jewish religion with reference to the impeding Assyrian threat (Judith versus Holofernes) the problem presents itself as follows:

The schematic representation (Fig. 2.5) shows that unless something is done to stop the Assyrian threat, the Jewish religion will always be under threat and in crisis. Therefore, the whole story of Judith can be summarised by the following transformational function:

Fig. 2.6 illustrates the transformation of the Jewish religion (designated as R) from a religion under threat of extinction (designated as R1) on account of the Assyrians and the presence of Holofernes, to a religion that survives extinction (designated as R2)under Judith. In a Greimassian semiotic approach/terms, the unfolding of the story is a transformation from a state of disjunction (designated as ˄) (mission to be accomplished by Judith) to a state of conjunction (designated as ˅) (mission accomplished). In this representation, the subject of transformation is the Jewish religion.

It should be noted, however, that transformation in the narrative does not take place by chance or automatically. Martin and Ringham36 state that transformation can correspond to the performance of the subject, who thereby becomes a subject of doing. Transformation in the Judith narrative does not happen until the introduction of Judith (protagonist) and the role played by all helpers around her. Therefore, the figure of Judith is the subject of doing in the narrative. The point here is that Judith's heroic actions bring about transfor-mation within the Jewish religion. Therefore the schematic representation Fig. 2.6 can be read as follows: Judith causes the Jewish religion to be transformed from a religion under threat of extinction to a religion that survives extinction.

In this case, the story of Judith, focusing on the heroic action of Judith, can be summarised as follows:37

The illustration Fig. 2.7, in simple terms, asserts that Judith's involvement saves her people and their religion from the impending threat by the Assyrians. Following this transformation in the narrative, in terms of the Greimassian semiotic approach, the figure of Judith is characterised by a transformotion doing, Martin & Ringham.38 Efthimiadis-Keith39 further observes that Judith goes through transformation herself, which she effects in order to bring about the situational transformation. Judith's beautification process constitutes this transformation.

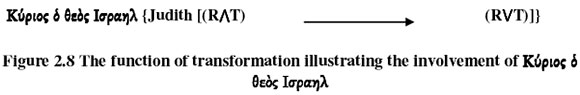

It should be noted, however, that Judith does not bring about transformation in the story by herself. She achieves victory through the help of God. Nickelsburg40 for instance observes that Judith's prayer wins the help of God. The Lord God of Israel is intimately involved in her victory (12:7).

The focus at this present moment is on the involvement of Lord God of Israel, who plays a significant role in both parts of the Judith narrative. In S1 he is the receiver of the prayers of the Jewish people. In S2, Judith's pious character points to her relationship and her dependence on God's help. For example when she beheads Holofernes, she prays, "Κραταίωσόν με, κύριε ὁ θεὸς Ισραηλ, ἐν τᾐ ἡμέρᾳ ταύτῃ" (Strengthen me, Ο Lord God of Israel, in this day) (13:7). The Lord God of Israel gives her the strength to destroy the enemy and to con-sequently bring a change of circumstance in her community. The whole nation is filled with joy and sings songs of praise; it is no longer full of fear and con-fusion. Given Judith's heroic action and the Lord's intervention, the story may be summarised as follows:

In summary, the schematic representation in Fig. 2.8 focuses on the beginning and the ending of the narrative and shows that Judith is indeed a unified whole, thus confirming Craven's findings (ch. 1, 1.3.1). The situation in the initial (S1) and final state (S2), according to Fig. 2.1, does not refer to either Part I or Part II separately, but to the whole story from chs. 1 to 16. Judith's heroic act is thus seen as one of the scenes which contributes to the process of transformation, as the Jewish religion transforms from being under threat of extinction to surviving extinction.

The subsequent survival of the Jewish religion, the praising of the Lord (13:17) and the honouring of Judith's brave act (13:18) confirm two important facts with regard to the compositional brilliance and transformation in the story. First, it confirms that the narrative ends honourably in favour of Judith and that her brave action benefits the community and saves the Jewish people and their religion. While this article observes that this honourable ending takes place in Part II of the story, it should not automatically suggest that Part II of Judith is more important than Part I. Second, it confirms that Judith challenges and reverses the initial state (S1) in Part II, namely the Assyrian threat and the claim that Nebuchadnezzar is god. In other words, the story develops from the religious claims of the Assyrians and their threats to the affirmation or acknowledgment that Κύριος ὁ θεὸς Ισραηλ is the real God.

Therefore, the main structure of the story, focusing on the heroic achievement of Judith, may be represented as follows:

Figure 2.9 illustrates how the God of Israel was undermined by the claim of the Assyrians (Part I) and how the Jewish religion survived the threat of extinction (Part II). Judith's introduction (preceded by the role of Achior) in the story serves as a turning point towards the religious freedom of Israel and the acknowledgment of Κύριος ὁ θεὸς Ισραηλ as the one and only God.

In summary, the study of the initial and the final sequences in the Judith narrative underlines the transformation of the Jewish religion from threat of extinction to survival as the narrative's main concern. This study takes a view that the existence of both the Jews and Jewish religion are inseparable. One cannot speak of the Jews without speaking of the Jewish religion. Judith's transformational doing consists of preserving the lives of her people and the existence of the Jewish religion. This eventually brings honour to the Lord God of Israel and further proves that he is the one and only real God.

Judith 's ending shows that a religious reversal eventually occurs in the Jewish community. This ending thus helps to clarify the possible intention/purpose of the story's structure with a beginning (Assyrian success/claims) and ending that focuses on Judith's success and the Assyrians' failure. This aspect is discussed in detail in the following subsection.

3 The Logic of the Ending of Judith

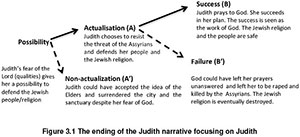

According to Kanonge,41 the ending of a narrative is subject to an intentional communicational strategy of the author/editor. Kanonge42 further states that the ending of a narrative is generally the place where the audience learns something to practice or avoid. Success or failure at this stage is always revealed. The Judith narrative, in this instance, is no exception to this kind of literary art by the author. For example, following the Greimassian semiotic approach, the logical structure of Judith 's ending with its focus on Judith can be presented graphically as follows:

Figures 3.1 shows that the author of Judith had at least one other possibility for ending his/her story. A and B (with continuous lines) in each diagram, illustrate the intentional choice of the author to compose or tell the story of Judith as we know it today.

The illustrations A' and B' in Fig. 3.1 show another open possibility of narrating the story of Judith. First, the author could have told his/her story and make Holofernes refuse to carry on with Nebuchadnezzar's commission (non-actualisation). Second, an open possibility was available for the author to have told the story in such a way that Holofernes succeeds in sleeping with Judith and carries on with Nebuchadnezzar's commission of destroying the Jewish people as he did with other nations.

The alternative possibilities of endings to the narrative from which the author could have chosen suggest that the current ending of Judith was an intentional choice of the author. From this discussion, it becomes clear that the structure of Judith was purposefully designed by the author. It seems that the conviction of the author is to urge the Jews to defend the honour of the Lord God of Israel against the claim of the Assyrians.

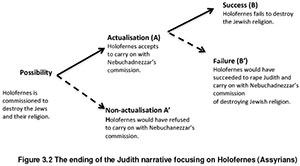

Therefore, the reading of Judith from the perspective of Holofernes (Assyrians), the schema can be represented as follows:

The choice of the author to tell the story as he/she prefers, reveals his/her motivation for the story.43 The choice of the author may also reveal his/her conviction about certain matters in his/her community. Figures 3.1 and 3.2 show that the author of Judith had at least one other possibility for ending his/her story. A and B (with continuous lines) in each diagram, illustrate the intentional choice of the author to tell the story of Judith (both Part I and II) as we know it today.

The ending of Judith as illustrated in Fig. 3.1, suggests that the author had a few other possibilities in composing the story. The author could have illustrated Judith as easily falling for both the undecided stance of the elders and the schemes of Holofernes, despite her God fearing quality as shown in 8:8 (ἐIΦοβεῖτο τὸν θεὸν σΦόδρα - she feared God greatly) and 11:17 (θεοσεβής - a religious woman).

The illustration A' and B' in Fig. 3.2 show another open possibility for narrating the story of Judith. First, the author could have told his/her story and make Holofernes refuse to carry on with Nebuchadnezzar's commission (non-actualisation). Second, an open possibility was available for the author to have told the story in such a way that Holofernes succeeds in sleeping with Judith and carries on with Nebuchadnezzar's commission of destroying the Jewish people as he did with other nations.

The alternative possibilities of endings to the narrative from which the author could have chosen suggest that the current ending of Judith was an intentional choice of the author. From this discussion, it becomes clear that the compositional structure of Judith was purposefully designed by the author to address the matters affecting the community of his time. It seems that the con-viction of the author is to urge the Jews to defend the honour of the Lord God of Israel against the claim of the Assyrians.44

The following section examines the actantial organisation of Judith in order to contribute further to the semiotic exploration of the narrative.

E CONCLUSION

This article comprises the summary of the findings of a narrative analysis of Judith as informed by the Greimassian semiotic approach. The point of contest centred on the alleged compositional imbalance of the structure of Judith, The aim of the article was to demonstrate that there is more to the story than just judging its value by a mere compositional structure. The application of the narrative analysis reveals that the first part of Judith is a necessary preparation for the second part, without which the act of Judith itself in Part II would be with-out context. Therefore, the acknowledgement of the necessity of these two parts as complementary halves is indispensable.

The finding in the analysis of the relation between the beginning and ending of the Judith narrative compels the reader to realise (instead of dwelling on the fruitless arguments of the compositional structure) that the Jewish religion is under severe threat of extinction in the beginning of the narrative (Part I). However, the ending of the story radically opposes the claim and threats by the Assyrians and the Jewish religion emerge victorious through the transfor-!national doing by the main character, Judith (Part II). The discussion of the ending of the story has revealed (Fig. 2.9) that the subject of doing (Judith) is no longer in disjunction (˄) with the object of quest, but in conjunction (˅) with the object. This means, therefore, that the compositional structure of Judith progresses from "mission to be accomplished" to "mission accomplished," instead of the so called "imbalanced and disproportionate."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bal, Mieke. "Head Hunting: Judith on the Cutting Edge of Knowledge." Pages 253-287 in A Feminist Companion to Ester, Judith and Susanna. Edited by Athalya Brenner. London: T. & T Clark International, 2004. [ Links ]

Branch, Robin G. and Pierre J. Jordaan. "The Significance of the Secondary Characters in Susanna, Judith, and the Additions to Esther in the Septuagint." Acta Patristica et Byzantina 20/55 (2009): 389-416. [ Links ]

Craven, Toni. "Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith." Semeici 8 (1977): 75-101. [ Links ]

____. Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith, Chicago, Calif.: Scholars Press, 1983. [ Links ]

De Silva, David A. Introducing the Apocrypha. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2002. [ Links ]

Efthimiadis-Keith, Helen. The Enemy is Within. Boston: Brill Academic. 2004. [ Links ]

____. "Judith, Feminist Ethics and Feminist Biblical/Old Testament Interpretation." Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 138 (2010): 91-111. [ Links ]

____. "On the Egyptian Origin of Judith or Judith as Anath-Yahu." Journal of Semi tics 20/1 (2011): 300-322. [ Links ]

Everaert-Desmedt, Nicole. Semiotique du Recit. Bruxelles: De Boeck, 2007. [ Links ]

Greimas, Algirdas J. On Meaning. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Harrington, Daniel J. Invitation to the Apocrypha. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999. [ Links ]

Hobyane, Risimati S. "A Greimassian Semiotic Analysis of Judith." D.Lit. et Phil. Diss., Northwest University, 2012. [ Links ]

Jordaan, Pierre J. "Reading Susanna as Therapeutic Narrative." Journal for Semitics 17/1 (2009): 114-128. [ Links ]

____. "Reading Judith as Therapeutic Narrative." Pages 331-442 in Septuagint and Reception . Edited by Johann Cook. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 127. Leiden: Brill Academic Supplements, 2009. [ Links ]

Jordaan, Pierre J. and Risimati S Hobyane. "Writing and Reading War: Rhetoric, Gender, and Ethics in Judith." Ekklesiastikos Pharos 91 (2009): 238-247. [ Links ]

Kanonge, Dihck M. "The Emergence of Women in the lxx Apocrypha." D.Lit. et Phil. Diss., Northwest University, 2012. [ Links ]

Martin, Bronwen and Felizitas Ringham. Dictionary of Semiotics. London: Cassel, 2000. [ Links ]

Moore, Carey A. Judith: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1985. [ Links ]

Nickelsburg, George W. E. Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Risimati Synod Hobyane

Faculty of Theology

North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus)

Email: Risimati.hobyane@nwu.ac.za

Article submitted: 2014/02/20

Accepted: 2014/06/02.

2 Carey A. Moore, Judith: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York: Doubleday, 1985), 76-77.

3 Moore, Judith, 76-77.

4 The book Judith will be referred to in italics (Judith), and the character Judith in normal font (Judith). Mieke Bal, "Head Hunting: Judith on the Cutting Edge of Knowledge," in A Feminist Companion to Ester, Judith and Susanna (ed. Athalya Brenner; London: T & T Clark International, 2004), 253-287.

5 Pierre J. Jordaan, "Reading Susanna as Therapeutic Narrative," JSem 17/1 (2009): 331.

6 Toni Craven, "Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith," Semeia 8 (1977): 75-101.

7 Toni Craven, Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith (Chicago, Calif.: Scholars Press, 1983).

8 Helen Efthimiadis-Keith, The Enemy is Within (Boston: Brill Academic, 2004), 25.

9 Robin G. Branch and Pierre J. Jordaan, "The Significance of the Secondary Characters in Susanna, Judith, and the Additions to Esther in the Septuagint," APB 20/55 (2009): 389-416.

10 Helen Efthimiadis-Keith, "Judith, Feminist Ethics and Feminist Biblical/Old Testament Interpretation," JTSA 138 (2010): 91-111.

11 Helen Efthimiadis-Keith, "On the Egyptian Origin of Judith or Judith as Anath-Yahu," JSem 20/1 (2011): 300-322.

12 Pierre J. Jordaan and Risimati S. Hobyane, "Writing and Reading War: Rhetoric, Gender, and Ethics in Judith," EkkPh 91 (2009): 238-247.

13 Efthimiadis-Keith, Enemy, 93.

14 Pierre J. Jordaan, "Reading Judith as Therapeutic Narrative," in Septuagint and Reception (ed. Johann Cook; VTSup 127; Leiden: Brill Academic Supplements, 2009), 331-442.

15 Efthimiadis-Keith, Enemy, 23-27.

16 Craven, Artistry and Faith, 8.

17 Efthimiadis-Keith, Enemy, 24.

18 Dihck M. Kanonge, "The Emergence of Women in the LXX Apocrypha" (DLitt et Phil diss., Northwest University, 2012).

19 Bronwen Martin and Felizitas Ringham, Dictionary of Semiotics (London: Cassel, 2000), 9.

20 Craven, "Artistry and Faith," 75-101.

21 Daniel J. Harrington, Invitation to the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Pub-lishing Company, 1999), 27.

22 Jordaan and Hobyane, "Writing and Reading," 238.

23 Efthimiadis-Keith, Enemy, 24.

24 Moore, Judith, 56.

25 Craven, Artistry and Faith, 1983.

26 Efthimiadis-Keith, Enemy, 24.

27 David A. De Silva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Aca-demic, 2002), 88.

28 George W. E. Nickelsburg, Jewish Literature beween the Bible and the Mishnah (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 99.

29 Craven, Artistry and' Faith, 1983.

30 Kanonge, "Emergence of Women," 126.

31 Nicole Everaert-Desmedt, Semiotique du Recit (Bruxelles: De Boeck, 2007), 16-17.

32 Martin and Ringham, Dictionary, 136.

33 Algirdas J. Greimas, On Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 123, 167.

34 Kanonge, "Emergence of Women," 126.

35 Martin and Ringham, Dictionary, 136.

36 Martin and Ringham, Dictionary, 136.

37 Cf. Greimas, On Meaning, 123

38 Martin and Ringham, Dictionary, 136.

39 Efthimiadis-Keith, Enemy, 250.

40 Nickelsburg, Jewish Literature, 98.

41 Kanonge, "Emergence of Women," 135.

42 Kanonge, "Emergence of Women," 135.

43 Kanonge, "Emergence of Women," 136.

44 Risimati S. Hobyane, "A Greimassian Semiotic Analysis of Judith" (D.Lit. et Phil, diss., Northwest University, 2012).