Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.27 n.2 Pretoria 2014

ARTICLES

Juxtaposing "many cattle" in biblical narrative (Jonah 4:11), imperial narrative, neo-indigenous narrative

Gerald O. West

University of Kwazulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

The final phrase of the book of Jonah offers an opportunity to re-read the book of Jonah from its odd ending. First, the article locates this interpretive project within a form of postcolonial theory, contrapuntal interpretation. Second, exegetical work is undertaken on the enigmatic final phrase. Third, the final phrase of the book of Jonah is brought into juxtaposition with the covetous eyes of the first Dutch settlers who came to South Africa in 1652. Fourth, and finally, the article reflects on the potential of this juxtaposition for the contemporary South African context, focussing specifically on the "Khoisan " descendants of the indigenous peoples of the Cape.

A INTRODUCTION

Some years ago I was approached by one of our Zimbabwean students about the third year OT Hebrew exegetical module he was intending to take in the next semester. He asked me if we could do the book of Jonah. I was intrigued, as my plan had been to do parts of the Joseph story in Gen 37-50 and parts of the book of Job. I had not thought of doing Jonah. So I pressed him, asking him what his interest in the book of Jonah was. Though he was a little embarrassed, he told me that he was hoping careful attention to the Hebrew text would help him resolve his questions about the episode in which Jonah is swallowed by the whale. His concern did not surprise me, for like many of our students he came from a context in which the historicity of this episode was emphasised. I was impressed that he wanted to interrogate the biblical text so carefully, for he was already aware that the detail of the text did not always confirm the theological appropriation of the text within which he had been schooled. Indeed, I assured him that I was sure that other detail would draw his attention while he was waiting for the whale.

It was a privilege and a joy, as it always is, working with a diligent and competent student as he came to grips with the detail of a biblical text. Our starting point, as is my usual pedagogical practice, was to begin with the text as a literary artefact. So we began with a close and careful reading of the Hebrew text, consolidating his grammatical competency as we moved through the text from left to right (or, from right to left). We allowed the literary dimensions of the text to raise their own questions about the historical, sociological, and theological location of the text, just as we allowed our own historical, sociological, and theological contexts to ask their questions of the text. But the literary dimensions of the text remained at the centre of our exegesis.

As I had suspected, the story wove its own web around us as we read and were drawn into the narrative. The historicity of Jonah being swallowed by the great fish seemed less of an issue the more this student entered the world of the narrative. And while we did delve into the probable worlds that would have generated a text like this, we focused on the artful composition that is the book of Jonah.

And yet we were puzzled, like many before us, about the final phrase of the book, ". . . and many cattle" (Jonah 4:11). I had encouraged the student to bring his African contexts into dialogue with the text throughout the exegetical process, making overt what is often covert in the gaze of the biblical scholar. In previous classes, for example, when working with the Joseph story, we had paid careful attention to the polygamous family that constitutes the core of that narrative. Joseph is the eldest son of the favourite or "loved" wife (intandokazi), and much of the narrative, we came to recognise, related to tensions among the sons of the four different mothers (Leah, Rachel, Bilhah, and Zilpah).1 Drawing on the knowledge that African students bring with them is part of my pedagogical method, so I encouraged the student reading Jonah to do likewise. He was initially a little reluctant, coming from an evangelical theological tradition, but he soon overcame this theological reticence, bewitched as he was by the resonances between his culture and elements in the text of Jonah. So we wondered, as Africans, what this final phrase, located so strategically as the final phrase in the narrative, might contribute to an understanding of the story.

I have not stopped wondering about this phrase, and this article is an attempt to continue a process of reflection on this phrase that began so many years ago. At the time I was working with this Zimbabwean student on Jonah, I was reading Jean and John Comaroff's remarkable historical-anthropological account of non-conformist missions in Southern Africa at the turn of the eighteenth century.2 In both volumes of their study they pay careful attention to the centrality of cattle to (what would become) "the Tswana," the indigenous people of the central area of southern Africa (including present day South Africa and Botswana). "Cattle, in sum," the Comaroff's say, "were the pliable symbolic vehicles through which men formed and reformed their world of social and spiritual relations."3 Some of the significance of cattle to the Tswana was understood by the traders, explorers, and missionaries who came among them, but their own European frames of reference often intruded in their attempts to civilise the Tswana.4 Though we did not have enough time to draw on the Comaroffs work in any depth, we did reflect what "an African reading" of this final phrase of the book of Jonah might offer. What would reading this story look like from within a cattle culture? The missionaries who lived among the Tswana at the turn of the eighteenth century may have had a distinct advantage over us, for only remnants of African cattle cultures remain. Yet the question has haunted me, as the ancestors of the Tswana and the Ninevites (and perhaps others as well) summon us to search this question.

In addition to reflecting on this enigmatic final phrase, this article also offers some theoretical reflection on how (some, socially engaged) African biblical scholars work with the Bible. In some of our recent work Jonathan Draper and I have been exploring a "tri-polar" approach to biblical interpreta-tion,5 elaborating on the work of the late Justin Ukpong.6 This heuristic account of African biblical interpretation recognises three poles in the interpretive process, the pole of the African context, the pole of the biblical text, and the pole of an explicit ideo-theological engagement through which context and text are brought into dialogue. The tri-polar model emphasises both the importance of distantiation (using biblical critical resources to allow the text to be "other" and using the social sciences to give the context a "thick" texture) and the importance of explicit ideo-theological interests to enable a dialogue between text and context, moving hermeneutically from critical distance into critical appropriation.

African biblical scholarship inhabits this ideo-theologically shaped back-and-forth movement between African context and biblical text. By the time African biblical scholarship emerges as an African scholarly discipline (in the 1970s),7 ordinary Africans had already taken ownership of the missionary-colonial Bible. In a sermon preached in 1933, Isaiah Shembe, the founder of Ibandla lamaNazaretha (Church of the Nazaretha), tells the story of how Africans stole the Bible from those who conquered them and "took all their cattle away."8 Kwame Bediako takes us further back in his discussion of the West African, William Wade "Prophet" Harris (1865-1929), whose appropriation of the Bible is, like that of Shembe, "uncluttered by Western missionary controls."9 Indeed, there are indications from the very first encounters of indigenous Africans with the Bible that they are making their own tentative attempts to ask their own questions of the Bible and so beginning to wrest the Bible from missionary-colonial collocations and control.10

African biblical scholars are more cluttered than ordinary Africans by colonial forms of knowledge, yet have sought to connect (in various ways) their communities with this knowledge in postcolonial contexts. So African biblical scholarship has always been "contrapuntal" in Edward Said's sense of the term. As Alissa Jones Nelson reminds us in her use of Said's work, Said's notion of "contrapuntal" must be situated within the commitments of the critical intellectual whose "proper place" is "in the realms of both theory and involve-ment."11 Like Said, African biblical scholars recognise that the texts of the centre cannot be ignored by those on the margins.12 "In the context of 'hybrid' or 'nomadic' social identities conditioned by postcolonialism," argues Jones Nelson, Said has identified, in his words, "a post-imperial intellectual attitude [that] might expand the overlapping community between metropolitan and formerly colonized societies . . . [b]y looking at the different experiences contrapuntally."13

Because the discourse of western biblical scholarship has tended to be "totalizing in its form," "all-enveloping [in] its attitudes and gestures," shutting out "even as it includes, compresses, and consolidates,"14 what is needed "is a dialogue in which these [African] 'others' represent themselves, not in inferior or subdivided categories, but as partners in conversation."15 These African others, though predominantly located in formerly colonised societies, are also found on the periphery of the metropolitan centres of the West.16 In order to achieve this envisaged conversation, Said and Jones Nelson argue that

[a] comparative or, better, a contrapuntal perspective is required . . . [W]e must be able to think through and interpret together experiences that are discrepant, each with its particular agenda and pace of development, its own internal formations, its internal coherence and system of external relationships, all of them co-existing and interacting with others.17

This requires, argues Jones Nelson, "the decentring of the dominant discourse in favour of exchange."18 What this would look like is that

[a]s we look back at the [Biblical Studies] cultural archive, we begin to reread it not univocally but contrapuntally, with simultaneous awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts.19

The importance and purpose of this, argues Jones Nelson, is "the range of insight and argument it makes possible."20

Contrapuntal reading is thus not simply a matter of jettisoning the texts of the dominant discourse, as some revisionary approaches advocate. Instead, this approach provides scholars with an opportunity to "take seriously [their] intellectual and interpretative vocation to make connections, to deal with as much of the evidence as possible, fully and actually, to read what is there or not there, above all, to see complementarity and interdependence instead of isolated, venerated, or formalized experience that excludes and forbids the hybridizing intrusions of human history."21

For Jones Nelson, "Contrapuntal dialogue is dialogue for the sake of ethical becoming." "This implies," she says, "a potential end, an ideal ethical context in which the collapse of the current hierarchy ushers in a new means of interrelation." She acknowledges that "[c]ontrapuntality alone will not be able to achieve this goal," but claims "it is an important tool" in this larger project.22 As a resource towards the larger project, contrapuntal dialogue "offers one potential way to move beyond the current gap and take biblical interpretation a step further in an increasingly interconnected world" by creating "non-hierarchical space in which critical interpretive texts encounter one another in a manner that allows both similarity and difference to emerge in the course of the encounter itself." "Without such a freedom of encounter," she argues, "the entire contrapuntal project is ended before it begins."23

It becomes apparent in reading her analysis of the kind of work I do (as part of the Ujamaa Centre) and others "from" (in various ways) postcolonial contexts, that "the goal" for her is an approach that will offer the potential for "integration" of academic and vernacular readings of the biblical text.24 With respect to my work and the work of Justin Ukpong, the two African scholars she analyses, with considerable care, she finds that we remain committed to operating "primarily within the vernacular ghetto";25 we are too context specific.26 She is right. While some African biblical scholarship is properly contrapuntal in her sense, bringing together (perhaps even "integrating") a range of vernacular (including both scholarly and non-scholarly varieties, from both postcolonial contexts and the margins of empire) interpretations together with a range of "western" mainstream academic interpretations in a "non-assimilatory integration," very few of us would see our work as having as its "ultimate goal" that of "non-assimilatory integration."27 Indeed, for Ukpong and I (and other socially engaged biblical scholars) biblical scholarship is primarily a reservoir of potentially useful resources for emancipatory work with particular communities of the poor and marginalised in African contexts.

So, to some extent, we can say that contrapuntal hermeneutics with much of African biblical hermeneutics is a moment in the larger process of emancipatory praxis, but not the goal. While we should and do want to take account of the diverse work done within the discipline of biblical studies, our African contexts are power-laden and require a commitment to liberation praxis and not only postcolonial dialogue. The tri-polar approach embraces this kind of contrapuntal hermeneutic, but as a step on the way to particular ideo-theological forms of appropriation for particular contexts. By locating contrapuntal hermeneutics within an African frame, we are engaging in the kind of "methodological reorientation" that Duncan Brown urges of those of us who live in the postcolony/South: "rather than subjecting inhabitants of the postcolony to scrutiny in terms of postcolonial theory/studies, how can we allow the theory and its assumptions also to be interrogated by the subjects and ideas that it seeks to explain?"28

While for the socially engaged biblical scholar the contours of our African contexts are readily apparent (given that we really do read the Bible with particular local communities), it is not always clear what resources the Bible has to offer to our contexts. Given the importance of the Bible as an African artefact and as an "accessible ideological silo or storeroom" for the marginalised African masses,29 notwithstanding its postcolonial ambiguity and the ongoing contestation of its "meaning" by a range of forces, socially engaged biblical scholars must work with it, and so we inhabit the contrapuntal spaces that already exist in our search for likely resources to share with the communities we read with in our various forms of "contextual" or liberation hermeneutics.30

The final phrase of the book of Jonah, "and many cattle," is one such resource. More precisely, it has the potential, I think, to be a resource in a postcolonial context like South Africa. African postcolonial biblical interpretation has always taken account of textual layers, both the redactional layers and the intertextual layers of the biblical text,31 as well as the juxtaposition of the Bible and local African texts.32 But in most cases the frame of appropriation is already present or becomes readily apparent in the juxtaposition,33 while in this case I am not sure what this literary detail portends for a particular context or what the most appropriate ideo-theological frame for its appropriation might be.

In some sense then, this article is an exploration of how socially engaged biblical scholars work, not always sure of what the contrapuntal nexus might offer or how what it offers might be used. By bracketing, for a moment, the move to contextual appropriation, our work most closely resembles the contrapuntal project envisaged by Alissa Jones Nelson. But, as the article will also show, we are summoned to move beyond the bracket.

B THE ODD ENDING OF JOHAH

So I return to this odd detail at the end of Jonah. Another way of framing its odd ending, in terms more familiar to biblical scholars, is what does it mean to read the book of Jonah from its odd ending. Clearly how a narrative is concluded is significant, not only for the final sentence or literary unit of the narrative, but also for the narrative as a whole.34 The ending of Mark's gospel is a good example, provoking the reader (whether the implied reader or us) to ask how we read "the gospel" as a whole given the enigmatic final sentence: "So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid" (Mark 16:8 NRSV).35Scholars of the book of Jonah have recognised the importance of its final sentence: "And should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left, and also many animals?" (Jonah 4:11 NRSV). But they have tended to focus their exegetical attention on how to construe the final sentence as a whole, with the key question being whether or not the final sentence is a simple declarative sentence or a rhetorical question, with the latter being how most, if not all, translations translate this verse.

C A RHETORICAL ENDING?

But as Ehud Ben Zvi carefully argues, "There are no grammatical or syntactical problems that pre-empt an understanding of the text as carrying a disjunctive, asseverative meaning, that is, "but, as for me, I will not have pity on Nineveh, the great city.'"36 I will come back to this, but it is worth noting at the outset that Ben Zvi does not include the whole sentence in his version of the final sentence as a declarative sentence. Ben Zvi continues his argument, making his stance on the matter clear by saying, "But the same holds true for readings of Jonah 4:11 as a question, which in this case and given the context," he claims, "can only be understood as a rhetorical question ."37 Because rhetorical questions "tend to relate to what precedes them in a communicative interaction and often tend to convey a challenge to the 'recipient' of the communication,"38 it is crucial, Ben Zvi argues, that the reader exercise pragmatic competence.39 While he recognises that there is no doubt that "later readers" have read Jonah 4:11 as rhetorical question, pointing to the "very long and unusually univocal history of interpretation in this regard,"40 he is concerned primarily about whether "the same holds true for the intended and primary rereaders of Jonah, likely in the Persian period."41

He is persuaded that the literati of the late Persian period would have been well versed in the use of rhetorical questions, and would have had no grammatical or syntactic difficulty with reading Jonah 4:11 as a rhetorical question, given their familiarity with a range of examples where questions are not marked by the interrogative ה or interrogative pronouns or particles.42 This leads Ben Zvi to ask the pragmatic question of whether there are "textually inscribed markers" that would have led these implied readers to read Jonah 4:11 as a rhetorical question. In general terms, he argues that "any reading of the book of Jonah informed by chapter three would have raised that possibility," explaining that any reading "informed by a theological outlook in which repentance plays an important role would have raised at the very least the possibility of a reading of the book of Jonah in which the city is not destroyed."43

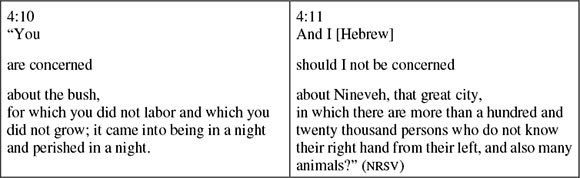

Specifically, he argues that the divine speech in Jonah 4:10-11 is structured in such a way as set up three sets of textual pairs, inviting the readership to establish connections between the pairs. The first pair consists of the contrast between the subjects, "you" (Jonah) and "I" (Yahweh). The second pair consists of the contrast between the verbal form, contrasting the positive qtl form of חום in the qal with the negative yqtl form of חום in the qal. And the third pair consists of the two relative על clauses. Ben Zvi argues that especially the "textual space allocated to the third pair and its own subdivision [the two אשר clauses] likely suggested to the intended rereaders that they are encouraged to see this contrast as salient and at least potentially a key interpretative factor." "Such an approach," he continues, "is substantially strengthened by the fact that the second אשר clause was assigned the concluding words of the section and the book as a whole."44

Ben Zvi offers a detailed analysis of these pragmatic pairs and concludes that

readings of verse 11 as an interrogative created no grammatical problems, are coherent with the expectations evoked by the lack of destruction of Nineveh envisaged in chapter 3, Jonah's response at the beginning of chapter 4, and the literati's knowledge that Nineveh was not destroyed during the time of Jeroboam II.

"Such views," he continues, "were also consistent with the literati's worldview in terms of the importance of repentance and ritual, which is also stressed in Jonah 1-3, as well as with some of the attributes they used to describe Yhwh (e.g., merciful)." "In addition," he argues,

a rhetorical question here would be consistent with some common attributes of these questions. For instance, these questions tend to establish a hierarchy of claims and, indirectly of speakers, and have been associated with teaching techniques aimed at inducing self-correction, by asking the recipient of the question to infer corrective knowledge on the basis of her or his existing knowledge.

Finally, Ben Zvi points out that

because of their poignancy, rhetorical questions may be used to conelude a literary unit (or subunit) with a high note. When they do so, the question remains answered in the mind of the readers and the addressees within the world of the book, but with no explicit answer written into the text since such a response would have deprived the rhetorical question from its emphatic, final position.45

The final position, however, is reserved for the final vav-connected nominal phrase, "and numerous cattle," but Ben Zvi does not deal overtly with this phrase. The implied question mark at the end of the sentence, after the final phrase, is his focus. But though he contends that the final sentence, though declarative in form, is intended to be read as a rhetorical question, he does recognise that other readings of this final sentence are both possible and perhaps invited. Grammatically, he acknowledges, "the text was phrased in such a way that allows readings of it as an assertion." This is "an important consideration" he goes on to argue, precisely because "these books were written to be reread time and again."46 In addition to the grammatical ambiguity, the implied audience, if indeed the literati of the late Persian period, would have been "fully aware of the destruction of Nineveh and of Jerusalem,יי and so

a declarative reading would be consonant with several theological positions that existed in the discourse of the literati (e.g., about the eventual fulfilment of YHWH's word, including its potential postponement, though not cancellation due to pious actions; the human inability to predict YHWH's actions and even construe the deity's motives).47

Such theological frames "would have likely generated," he argues, "at least some wondering about the exact significance of the text." Indeed, he continues, "a declarative reading finds support in some textually inscribed markers." For instance, such a reading would contrast Jonah, a human who felt "pity," with Yahweh, a destroyer deity who does not show "pity," but who uses humans, plants, and animals as temporary tools.48

Ben Zvi concludes his careful exegesis of Jonah 4:11 by making an argument for what he refers to as the "metaprophetic character" of Jonah. The lack of an explicit interrogative ה signals, he argues, a deliberate embrace of ambiguity. Such an ending invites a re-reading. Even authoritative texts "may be mistaken about YHWH." "Reading prophetic books cannot lead to certainty about the deity, or to actual predictions; yet even that they [readers of authoritative texts as authoritative texts] have to learn by reading prophetic books."49 What Ben Zvi does not consider is that the final phrase, neglected by him, "and many cattle," might point metaprophetically in other directions.

Philippe Guillaume offers a robust response to Ben Zvi's analysis, welcoming his demonstration of the ambiguity of Jonah 4:11, but contending that "the interrogative reading is eventually redundant."50 He prefers a "straightforward reading of the end as it stands." "As it stands," he argues, "the text has the significant advantage of stating unambiguously the sovereignty of YHWH over the entire world."51 But the sovereignty of Yahweh "does not turn YHWH into a wrathful god à la Deuteronomy," insists Guillaume; instead, "the narrator uses Jonah to demonstrate the positive implications of determinism," where divine will "overruns individual accountability," where human actions, "sinful or repentant, are of little consequence," where Yahweh "metes out judgement and destruction dispassionately"; in sum, "the assertive reading of the end of Jonah challenges the reader to consider the rise and fall of civilizations with the same detachment."52

Somewhat oddly, Guillaume then goes on to find a moral meaning in this dispassionate tale, stating that, "The book of Jonah states in no veiled fashion that all tyrants meet their end." He then goes on to offer a postcolonial interpretive reflection, saying that such a reading "could have been a welcome conclusion for the tyrannized throngs of all times, had the meaning of the text not been controlled by a literate elite who perceived the dangers of such a reading."53

While I applaud Guillaume's postcolonial impulse,54 I worry whether his dispassionate Yahweh knows the difference between the right and the left and how this Yahweh decides between the right and the left! Finding a postcolonial answer requires us, perhaps, to consider more carefully the final phrase, largely ignored by Ben Zvi and Guillaume, though their exegesis of Jonah 4:11 has mapped the textual, socio-historical, and theological terrain rather well.

D AT LAST, "MANY CATTLE"!

The unruly final phrase, "and numerous cattle," has perplexed many scholars, with some early historical critics excising this phrase.55 But recent work has given more careful attention to this enigmatic phrase. Yael Shemesh offers an extensive exegetical analysis of this phrase, focusing on the function and status of animals in the book of Jonah. Working with the assumption that the book of Jonah concludes with a rhetorical question, Shemesh argues that, "The very last words - 'and many beasts'- indicate that divine mercy transcends human beings and includes animals as well."56

This conclusion is built on careful analysis, beginning with a history of reception of this phrase, most of which, from rabbi Rashi, to the apostle Paul, to Thomas Aquinas, to René Descartes, to Immanuel Kant, and to modern scholars, have been shaped, she argues, by an anthropocentric worldview.57 Against this trend, she offers a reading of this "unexpected" final phrase that locates it within a wider biblical discourse in which animals are divine agents.58 She surveys animals as the, "totally subordinate,"59 agents of Yahweh in the Bible generally,60 and then locates animals as agents of Yahweh in the book of Jonah within this biblical typology. With respect to the latter, Shemesh concludes that

the portrayal of animals in general and of the great fish in particular as divine agents serves the story's ideological line and sharpens its lessons: God's absolute control of His world, including the sea that terrifies human beings; and the criticism of Jonah, God's emissary, who, unlike the animals, attempts to evade his mission.61

Shemesh then turns to the common community and the "common destiny" implied by this phrase. He notes that the Ninevites and their cattle are directly connected in the king of Nineveh's royal proclamation:

Let man and beast, herd and flock, not taste anything; let them not feed, or drink water, but let man and beast be covered with sackcloth, and let them cry mightily to God; yea, let every man turn from his evil way and from the violence which is in his hands. Who knows, God may yet repent and turn from His fierce anger, so that we perish not? (Jonah 3:7-9).62

While Shemesh accepts that "this description is extraordinary for the Bible," and that it may well reflect customs associated with the Assyrians, she argues that it "is not so astonishing, given the special status of animals in this narrative, from the big fish that acts in the service of God, through the tiny worm which also acts on His behalf, and concluding with the divine compassion that extends to 'many beasts' as well."63 She rejects the xenophobic readings of those scholars who see this as "the act of childish gentiles,"64 as he does the readings of those scholars who consider the king's decree as "satirical or humoristic."65 Instead, she argues that like the story of the flood (with which the book of Jonah shares many features)66 and the book of Joel, we have in the book of Jonah a "common destiny of human beings and animals," "perhaps even solidarity between man and beast."67

Divine mercy, as I have indicated, is considered by Shemesh to be the key theme of the book of Jonah. While "the impression conveyed by the start of the story is that God is wrathful and punitive," the last verses of the book demonstrate, she argues, that God is merciful, and not only to humanity but also to animals.68 Indeed, she continues, God's compassion to animals "is emphasized by the structure of His rebuke of the prophet, which draws special attention to the words 'and many beasts' by leaving them without a parallel clause."69 Moving our exegetical analysis into the neglected final phrase, Shemesh offers us the following structure:70

The special place given to the final phrase "sharpens one of its main messages," she argues: "God is not a national deity, the God of Israel alone: rather, His dominion extends to the entire Earth and His subjects are all human beings as well as animals." More concisely, God is not a xenophobic or an anthropocentric god. But while Shemesh asserts that this final phrase reflects that animals "do not exist solely to be exploited by human beings" and that "their lives have an independent rationale" (a view "maintained with great force in the book of Job"), she does acknowledge that "the Bible [in general] does not recognize animals as a legal entity distinct from human beings and manifestly links their fate to that of human beings."71

The linkage the book of Jonah in general and Jonah 4:11 in particular establishes between humanity and animals "imposes special responsibility on human beings," Shemesh insists, "because their behavior affects the entire world." Moreover, she continues, this linkage "also imposes special responsibility on God, who governs the world, since punishing certain human beings for their transgressions will inevitably harm the innocent as well, both human beings (such as children) and animals."72 In other words, the final phrase is not only a cautionary tale for prophets/Jonah, but also for gods/God.

Shemesh accepts that the dominant perspective in the Bible is "that animals exist principally to benefit human beings (in the form of meat, leather, etc.) or to be used in divine worship (as sacrifices)." She accepts too that this view is present to some extent in the book of Jonah, for the sailors offer sacrifices "to the Lord" (1:16). However, her argument "is that in the view of the book of Jonah animals are not just instrumental."73 They are integral to the human community; at least, this is the view I want to explore by way of African reflections.

But before I embark, like Jonah, to other territories, I will explore the instrumentalist understanding of these cattle more fully, via the work of Thomas Bolin, who argues in detail that "the Ninevite beasts' function in the story as sacrificial animals."74 Though he does not deal with Shemesh's article, he worries about work of this sort, which he thinks "imports modern theological tenets into the biblical text."75 Such readings "constitute a kind of exegetical anachronism," he argues, because they attribute to ancient authors "theological views which not only could not have plausibly been held in antiquity, but which are also contradicted by our knowledge of ancient religious beliefs."76 Instead, he offers a reading of the final phrase, "and many cattle," forged "against the background of ritual sacrifice in the ancient world and its importance in patron-client relations based on submission and exchange." From this socio-historical perspective, he argues, "God in the Book of Jonah can be seen as portrayed along the lines of ancient Near Eastern royal ideology," that is, "as the ruler of the world extending his domination beyond traditional borders."77

But like Shemesh he begins with the texture of the text, recognising that the final phrase, "and many cattle," "acts as a coda that breaks the symmetry between Yahweh's feelings about Nineveh and Jonah's feelings about his mysterious qiqayon plant." However, the phrase is not a floating fragment, for like Shemesh he recognises that "the phrase is also the third time in Jonah where the people and domestic beasts of Nineveh are referred to by the terms אדם and בהמה, linked by conjunctive-vav, the other two instances occurring in the king's decree 3,7-8." For if we remove the intervening relative clause introduced by the second אשר in Jonah 4:11, we are left with the symmetrical chiastic phrase: רבה רבו אדם ובהמה ("many men . . . and many cattle").78

Having established the textual link between the people of Nineveh and their beasts, Bolin goes on to probe the nature of this link, concentrating on the socio-historical perspectives of the implied first millennium B.C.E. readers. Though he recognises that there are contending religio-cultural understandings of ritual sacrifice,79 Bolin works with the understanding that, "Ritual sacrifice in ancient religion is based upon a social world that is characterized by hierarchical structures which are maintained by an ongoing system of gift-exchange and reciprocity."80 He uses this frame to analyse the two references to sacrifice in Jonah, the sacrifice of the sailors in Jonah 1:17 and the promise of sacrifice that Jonah makes in 2:10. In both case the generic term זבה is used, referring "simply to the ritual slaughter of an animal, without distinction about the specific motivation behind the act."81 Though he acknowledges that these "two explicit mentions of sacrifice in Jonah do not appear to clarify the state of relationship between their human offerers and the divine recipient, which is something that sacrifices are explicitly supposed to do," he goes on to say that it "seems plausible" that the role of the animals in 4:11 "is as future offerings to Yahweh."82

His assumption that "the main religious role for domesticated animals in antiquity was for sacrifice," leads him to "a plausible explanation" for the animals being clothed in sackcloth, namely an explanation based on substitution.83 They "stand for״ the human populace. The most obvious reason, he continues, for connecting the animals of the Nivevites "with their human owners while in the process of attempting to avert divine punishment is that they are to be seen as stand-ins for the Ninevites in a forthcoming sacrifice that seeks to expiate the city's wrongdoing."84 I wonder, however, whether the Ninevites are not "standing with" their cattle, rather their cattle "standing in" for them.

The domestic identity of these animals leads Bolin to explore another dimension of sacrifice. Yahweh's power, though considerable in this story, "is limited to the natural - as opposed to human - world." "However," he continues, "as domestic beasts, the animals of Nineveh are not under Yahweh's control and indeed, they are the only non-human living thing in the Book of Jonah that is not the object of the verb מנה with God as its subject."85 The Ninevites "numerous cattle" are under their own control, as their king's decree in 3:7-8 makes clear. Yahweh's strategy in sending Jonah to Nineveh may then have been a coercive threat, placing the Ninevites in a position where they would have to submit themselves and their livestock (and their land) to a deity with imperial pretensions. "This confluence of God's power over nature and his efforts to exert his will over humans seems," says Bolin "an unambiguous example of ancient Near Eastern royal ideology."86 Drawing on elements of royal ideology in the ancient Near East, with particular reference to Persian royal ideology, Bolin argues that, "Instead of viewing God as extending his graciousness and mercy to those outside of Israel, readers of Jonah ought to [view] God to be doing what every Near Eastern potentate did - bringing his rule, his sovereignty, to bear on those who exist outside his dominion."87 Perhaps, he continues, "their evil" (1:2) which brings them to Yahweh's attention in the first place is "nothing more than that they are not yet the obedient clients of God."88

E POSTCOLONIAL CATTLE

Again, I am drawn to the postcolonial impulses in Bolin's reading. But I wonder whether the Ninevites are intending to sacrifice their "many cattle" to this foreign deity. Their relationship with their cattle is perhaps more complex. It seems to me that the "brute" presence of this final phrase as the final phrase remains unexplained.89 Yael Shemesh comes closest, I think, to giving this phrase its due weight.

Bolin makes a compelling argument for the importance of animal sacrifice within ancient Near Eastern imperial ideology, but does not explain why this particular phrase is given pride of place, in narrative or sociological terms. And while arguments about how the book ends in terms of its discursive form, whether with a simple declarative sentence or a declarative sentence as a rhetorical question, are crucial for our understanding of the book as a whole, they do not offer much by way of the significance of the final phrase, "and many cattle."

Of those who have offered postcolonial reflections on Jonah, only Bolin grapples with the final phrase. Bolin worries about Yahweh as an imperial God. Chesung Justin Ryu shares this worry, wondering why Yahweh sides with "the great city" rather than the margins. Jonah's silence, he concludes, is appropriate.

The only thing he could do was to remain silent. This silence has long been interpreted by established Christian scholars as obedience or agreement to God's universal love for all. However, a colonized audience [like "Israel"] would have understood what the silence of Jonah meant because they were with Jonah there, in silence. Some weak, oppressed, and colonized people will continue to explore their own locations of silence or resistance in the silence of Jonah.90

Does Jonah then have the final "word," not Yahweh? Do we find Jonah sitting in silence with the victims of city-based empires, much as Rizpah sat in silence with the bodies of those who David had slaughtered before Yahweh (2 Sam 21:1-14)? If so, how do the "many cattle" feature in this postcolonial reading, for we must not forget this final phrase. Do we follow Bolin and Ryu and read the story as a critique of Assyrian imperial power, or do we look for a reading that identifies with a cattle culture people, like the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa?

In terms of my process of making this connection, of offering this juxtaposition, it emerged from my own (contrapuntal) reading of a range of literature to do with African biblical interpretation. As I have indicated, the enigmatic final phrase of Jonah was a potential prophetic fragment, but one that I was not sure what to do with. It was only when I was reading the journals of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape, attempting to understand the arrival (and settling) of the Bible in Southern Africa, that I found a possible line of connection.

F SETTLERS IN SEARCH OF "MANY CATTLE"

I have persisted with the translation "cattle" for 91בהמה because I want to explore a little more fully my opening comments about African "cattle culture," though my analysis might be relevant to any culture in which other livestock occupy a similar place. What that place is, is the focus of this section of my article. As I indicated at the outset, this final phrase, "and many cattle," has haunted my reading of this text for many years. I now return to re-read this concluding phrase, "and many cattle," via a rather strange route. Having been vomited up on to the southern part of the African continent,92 my gaze shifts to the first imperial settlers in southern Africa and what they make of the indigenous Africans and their "many cattle."

When Jan van Riebeeck arrived with the Dutch East India Company's ships at the Cape in early April 1652, among the first items brought aboard the Drommedaris was "a small box with letters."93 Among the letters they open and read and copy, but then close and forward, is a letter written by "the Hon. Van Teijlingen to the Hon. Carol. [Carel] Reijnierssen, Governor-General, and the Hon. Councillors of India." Van Teijlingen is the captain of the Diamant, one of the fleet of ships owned by the Dutch East India Company94 making their way around the Cape on their return trip to "the beloved Fatherland." Among the information he offers is the following:

Only one head of cattle and one sheep were brought to us by the savages, nor do we see any likelihood - in view of the unwillingness of these unreasonable persons - of obtaining any more cattle or other refreshment, although cattle in abundance have been seen by seamen not far from the shore.95

This information is important enough for him to repeat it in another letter, this one addressed to "the captains of the ships Prins Willem, Vogelstruijs, Vrede, Orangie, Salmander, Conninck Davit, Lastdrager and Breda." While the first letter is on its way to India, the second is to his fellow fleet captains, on their way to the Netherlands. He writes in this second letter:

We have obtained here for refreshment only one head of cattle and one sheep, although inland the seamen have seen cattle in abundance; the unreasonable savages, however, would not bring us any more than those mentioned. God grant that you may fare better.96

Though Jan van Riebeeck would prove himself more pragmatic, his experience would soon match that of van Teijlingen. There were "many cattle," but few available for trade. And trade was what the Company was about. Van Riebeeck was born into a respectable middle-class family in a period when Europe was ruled as much by powerful private traders as it was by traditional political formations. There was considerable colonial and commercial competition between the imperial powers, including England, Holland (specifically the United Dutch Provinces), Spain, and France, as they competed for control and profit in a geographically and geologically expanding world. Van Riebeeck was also born (1618/19) into a period in which Calvinism was taking its form after the Synod of Dordrecht (1618-1619) and in which the Dutch East India Company was in its prime.97 Trade and religion, in that order, would shape Van Riebeeck's life.

Having completed an apprenticeship in medicine, van Riebeeck entered the service of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC), in April 1639, as a junior surgeon. But shortly after arriving in Batavia, the headquarters of the Company in the East, from which it "ruled over its valuable and extensive possessions,"98 he "abandoned the medical profession for the sake of commerce and administration."99 He gradually worked his way up the hierarchy of the Company, serving in a variety of positions in a variety of locations in the East. Like many others in the employ of the Company, van Riebeeck traded both on behalf of the Company and his own behalf. This practice was common in a Company that squeezed its employees to the maximum, extracting as much work as they could from them at a minimum wage. Profit was the one true god. If one was to assemble a personal fortune one had to do so "privately." The Company tended to look the other way, provided this private trade was not blatant. But when it became apparent, the combination of Calvinism and Company policy resulted in sanction. Van Riebeeck was indicted for private trade and sent home to stand trial in 1648.100

In March of that year van Riebeeck encountered the Cape on his way home, but did not stay. The Lords Seventeen, the policy directors of the Company, meeting in Amsterdam had no mercy on van Riebeeck and he was discharged. But some years later, having continued in forms of commercial work, van Riebeeck was offered a chance to comment on a proposal to establish a refreshment station for the Company at the Cape. His memorandum on the matter had an impact, for van Riebeeck was appointed as commander of the envisioned refreshment station at the Cape.101

Providing "refreshment" for the ships that plied the route between the Netherlands and Batavia (in Java; now Jakarta, Indonesia) was a substantial undertaking, and van Riebeeck set about it with vigour. The ordinary rhythms and details of this project are recorded in the daily entries in the Company's journal, a requirement of each of the Company's possessions.102 As early as the entry for the 7 th April 1652, two days after the ships sighted the Cape and a day after the first landing party went ashore to return with the letters, van Riebeeck begins the work of establishing the refreshment station. The final paragraph of the entry is instructive, for it offers an early glimpse of the key elements of the project:

This evening we went ashore together provisionally to consider more or less where the fort should be built. Also had 2 savages on board this evening, one of whom could speak a little English. We generously filled their bellies with food and drink. As far as we could gather no cattle could be obtained from them for - as they gave us to understand by means of broken English and signs - they were only fishermen and the cattle were always supplied by those from Sal-dania. This we had also learned from a few survivors of the ship Haerlem.103

Among the many constituent elements of the nascent project was the quest for a reliable and steady supply of cattle.104 Journal entry after journal entry records the increasingly desperate attempts to gain access to and possess the indigenous people's many cattle. Just as "the Strandlopers,"105 those who lived in the coastal strip of the Cape, had promised cattle when "the Saldania's" arrived, so too when "the Saldanias" did arrive, on the 10th April, they too promised "enough cattle."106 This too would become a pattern.

The Company at the Cape encouraged contact and offered generous hospitality to the indigenous peoples, "to make them all the more accustomed to us and in due time to extract as much profit as practicable for the Hon. Company."107 But it becomes apparent early on that acquiring many cattle will be difficult. The absence of cattle, and the milk and fresh meat that they signify for the Company, has a debilitating effect on the minds and bodies of the Company. As sickness spreads it seems to them "as if Almighty God is severely visiting us with this plague,"108 and part of the problem is that

since our arrival [and it is now the 10th of June] we have been unable to obtain from these natives more than one cow and a calf - and that at the very beginning. So at present life here is becoming sad and miserable; daily one after another falls ill with this complaint and many are dying from it. If it does not please the Almighty to deliver us from this plague, we see little chance of completing our work, as many of our men are dying and the rest are mostly sick in bed.109

For just as the Company is cultivating its relationships with the indigenous people for the purpose of trade, principally many cattle, so too the indigenous people are nurturing their relationship with the Company for the purpose of trade, by promising many cattle.

But many cattle are not forthcoming, only a few, and the Company begins to worry whether they can meet the demands of not only those stationed at the Cape but their primary constituency, the passing ships. While they do make headway with establishing a garden of agricultural produce, both local and continental, they can only hope for the promised cattle. In the journal entry of the 28th, 29th, and 30th July 1652 they are confident that they "shall be able to supply all the ships with vegetables," but that there are no cattle as yet for either the sick on the land or the soon to be expected ships at sea.110 A month later, on the 12th August, they are still waiting.

We have ... obtained nothing from the natives to date except - as already stated - one lean cow and a calf when we first arrived at the beginning of April. Up to now, with all the hard work, we have had to content ourselves with stale food and occasionally some Cape greens and a little Dutch radish and salad, until such time as God our Lord will be pleased to let us obtain some other and more food.111

The rhythms of the Company "treating" the natives with "wine and tabacco" and the natives promising "an abundance of cattle" continue,112 month after month, year after year. Surrounded by so many cattle, but unable to acquire them, the Company even begins to fantasize about abandoning their policy of trade, wondering aloud in the journal about how they might lure the indigenous peoples "to come to us, on the pretence of wanting to barter copper for their cattle," but "then, having them in our power, we should kill them with their women and children and take their cattle."113 Cattle do begin to trickle in as part of the emerging trade, but only very few and of a quality that mitigates against using them as breeding stock. And when the Company do establish a small herd of cattle of its own, there are regular raids by the local peoples, reclaiming their cattle.114

Slowly the Company recognises that the indigenous people appear "to be loath to part with their cattle."115 Even when trade does pick up, in early December of 1652, in the summer, acquiring cattle remains a problem, "for the natives part with them reluctantly." The entry then goes on immediately to interpret this reluctance, saying "as we pretend to do with the copper plate."116 The Company assumes that, as with them, trade is the highest goal, and that, like them, the indigenous peoples are attempting to drive up the price of cattle by showing a reluctance to barter them, for they have "cattle in countless num-bers."117 They assume that just as they value copper plate above copper wire, so too the local peoples value cattle above sheep, for they "were more reluctant to part with their cattle than with their sheep."118 They also assume, following the same logic, that when the natives are "not eager to trade," though they have "thousands of cattle grazing in the vicinity of the fort," that "they have already been glutted with copper."119 "It is really too sad," the journal entry of the 18th December 1652 reflects, "to see so great a number of cattle , to remain so much in need of them for the refreshment of the Company's ships, and yet to be unable to obtain anything worth while in return for merchandise and kind treatment."120

On the 10th February 1655 the indigenous people make it clear that there is another dimension to their reluctance to trade their cattle. They explain, the entry records, "that we were living upon their land and they perceived that we were rapidly building more and more as if we intended never to leave, and for that reason they would not trade with us for any more cattle, as we took the best pasture for our cattle, etc.."121 Not only are cattle integral to their identity in ways that the Company cannot imagine, but cattle are also their link to the land. In the following exchange, on the 30th May 1655, one of the local clans elaborates:

In the afternoon the Commander himself went to their camp and spoke to them. We proposed to them that they might give their cattle to us and in return always live under our protection and with their wives and children enjoy food without care or trouble. They would be assured that none of their enemies could in any way harm or molest them, and in this way they could continue to be the good and fast friends of the Hollanders, etc.

To this they replied that they wished to remain good friends with us and, as stated before, would for a bellyful of food, tabacco and arrack, etc., fetch firewood for the cooks; but as to parting with their cattle, that could not be.

We thereupon pointed out that we did not wish to have their cattle for nothing, but wanted to pay for them with copper and tobacco to their satisfaction, and that we, on the other hand, would be content with the service they would thereby be rendering to us, and so forth.

They rejoined that they could not part with their cattle, either by sale or gift, as they had to subsist on the milk, but that there were other tribes in the interior, and when these came hither we could get sufficient [cattle].122

Here this local clan, only one of the many clans that populate the southern part of Africa, try to explain the inseparability of their cattle from who they are. Though one of the more vulnerable clans in the region, and though they are tempted to find refuge within the confines of Company controlled land, they nevertheless cannot imagine being separated from their cattle. "That could not be."

A day later the cattle themselves teach van Riebeeck and the Company another aspect of the integrity of African cattle culture. During the night of the 1st of June 1655 a leopard entered the Company's fowl-house. Two of the Company's men, a groom and the sick-comforter, try to kill or catch the leopard, but are themselves attacked, and the leopard flees. Because the cattle kraal is nearby, their attention is drawn to the cattle.

Something remarkable was observed among our cattle in the kraal, which is near the hen-house, the stable and the hospital. As soon as they became aware of the leopard in the fowl-house they all collected in a body with their horns towards the door and formed a crescent, so that the leopard had all he could do to keep clear of their horns and escape - even though, by their bellowing, these animals gave ample evidence of their terror of the wild beast. Indeed, we have often noticed that leopards, lions and tigers are unable to harm cattle when they form themselves into a protective circle, so that not a single one of the calves inside is carried off by the wild beasts - a wonderful sight to see.123

In cattle cultures, the cattle are "a body," a single entity, integrally related to each other and to those they link to the land, each other, the ancestors, and God. For these peoples of the Cape, the connections with the ancestors and God are least visible. Indeed, I am speculating, assuming that these peoples share these aspects of cattle culture with other clans to the north, like the BaTlhaping.124 The indigenous peoples of the Cape did their ritual slaughtering of cattle beyond the gaze of these Europeans, so the journals offers us little reflection on such practices and their significance. But we catch a glimpse in the journal entry of the 8 th September 1655, when an expedition leaves the fort to explore and scout the surrounding environment. They experience the ritual slaughter of a cow, described in detail:125 "They slaughtered a beast in a way none of us had ever seen before. Having pulled it down to the ground with ropes, they cut it open from the side of the belly upwards, and while it was still alive they took the intestines out and scooped out the blood with pots." This unusual mode of slaughtering may be the normal practice of the local people, or it may be a particular way of slaughtering related to religious matters. Just as the indigenous peoples are reluctant to part with their cattle, except in the case of old or diseased beasts, so too they are reluctant to explain the significance of cattle.

On the 3rd May 1655, more than three years after they have arrived at the Cape, an opportunity presents itself for the Company to probe the local significance of cattle. What prompts the query is the sight of the area around the fort "swarming with cattle and sheep, at a guess well over 20 thousand head." "Yet," the entry goes on to note, "from that vast multitude we could obtain no more than 3 young and old cows and 7 ditto sheep, in spite of the high prices offered and the good entertainment given the natives." Finding a local who had "learnt to speak a little Dutch," they enquire of him "why these natives offered so few cattle for sale, in view of their desire for copper and, especially their liking for tobacco." "Claes Das," the interpreter, "gave us to understand that these folk were not anxious to part with their cattle, but that within a few days Harry [another local interpreter] would be coming along with other people and still more cattle of which we could get as many as we desired."126

An answer is deflected and deferred. And similarly with their cattle. It was always others that would supply the cattle the Company craved. For each particular people their cattle were not a commodity to be traded. Precisely what place they inhabited among these indigenous peoples is not now clear,127 for these peoples have been decimated, conquered, colonised and denigrated (like the Ninevites, "who do not know their right hand from their left"?) precisely because they had many cattle. Only fragments remain, like the final fragment of the book of Jonah, "and many cattle."

G A POSTCOLONIAL APORIA

My project too is incomplete, for I have three juxtaposed narratives but no clear interpretive frame. My own ideo-theological orientation wants to connect these narratives via a post-contrapuntal postcolonial liberationist theoretical framework,128 but the connections are not that clear and I hesitate to force lines of connection and conversation. The problem is that while the Dutch imperial narrative is fairly clear, the other two narratives are not. The final phrase of the book of Jonah, "and many cattle," together with other literary and socio-historical detail, destabilises any claim to a coherent interpretation. Even more problematic is the fragmentary narrative of the indigenous peoples of the Cape, notwithstanding the emergence of Khoisan organising and mobilising.129 Perhaps it is only as the story of the Khoisan of the Cape takes shape,130 as told by themselves, that their ancestors' many cattle and the many cattle of book of Jonah will forge connections.131 But any conversation should proceed with caution, allowing a contrapuntal moment before moving towards appropriation.

I started out trying to make sense of this "scripturally unique formula-tion,"132 wondering if it might be a resource for African "others" whose narratives are not yet told. But perhaps the final phrase, tenuously linked to the rest of the book by a grammatically indeterminate vav, is a reminder of the dangers of trying to make sense of the other. God and Jonah, each in their own way, are trying to make the Ninevites conform to their perspectives; similarly, van Riebeeck and the Company strive, day after day, to make the indigenous peoples of the Cape fit their frame. Perhaps the final phrase in the book of Jonah is a reminder of the otherness of the other.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abrahams, Yvette. "'Take Me to Your Leaders': A Critique of Kraal and Castle." Kronos: Southern African Histories 22 (1995): 21-35. [ Links ]

Bediako, Kwame. Christianity in Africa: The Renewal of a Non-Western Religion. Edinburgh and Maryknoll, N.Y.: Edinburgh University and Orbis, 1995. [ Links ]

Ben Zvi, Ehud. "Jonah 4.11 and the Metaprophetic Character of the Book of Jonah." The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9/5 (2009): 2-13. [ Links ]

______. Signs of Jonah: Reading and Rereading in Ancient Yehud. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 367. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Bolin, Thomas M. "Jonah 4,11 and the Problem of Exegetical Anachronism." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 24/1 (2010): 99-109. [ Links ]

Brown, Duncan. "Religion, Spirituality and the Postcolonial: A Perspective from the South." Pages 1-24 in Religion and Spirituality in South Africa: New Perspectives. Edited by Duncan Brown. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Carpenter, Cari M. and K. Hyoejin Yoon. "Rethinking Alternative Contact in Native American and Chinese Encounters: Juxtaposition in Nineteenth-Century Us Newspapers." College Literature 41/1 (2014): 8-42. [ Links ]

Reform, "Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Bill," 8 pages. Cited 4 March 2014. Online: http://www.jutalaw.co.za/media/filestore/2013/10/B35_2013.pdf. [ Links ]

Comaroff, Jean and John L. Comaroff. Christianity, Colonialism and Consciousness in South Africa. Volume 1 of Of Revelation and Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier. Volume 2 of Of Revelation and Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Draper, Jonathan A. "'For the Kingdom Is inside of You and It Is Outside of You': Contextual Exegesis in South Africa (Lk. 13:6-9)." Pages 235-57 in Text and Interpretation: New Approaches in the Criticism of the New Testament. Edited by Patrick J. Hartin and Jacobus H. Petzer. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1991. [ Links ]

______. "Old Scores and New Notes: Where and What Is Contextual Exegesis in the New South Africa?" Pages 148-68 in Towards an Agenda for Contextual Theology: Essays in Honour of Albert Nolan. Edited by McGlory T. Speckman and Larry T. Kaufmann. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2001. [ Links ]

Dube, Musa W. Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible. St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2000. [ Links ]

______. "Toward a Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible." Semeia 78 (1997): 11-26. [ Links ]

Elphick, Richard. Kraal and Castle: Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977. [ Links ]

Guillaume, Philippe. "The End of Jonah Is the Beginning of Wisdom." Biblica 87 (2006): 243-50. [ Links ]

______. "Rhetorical Reading Redundant: A Response to Ehud Ben Zvi." The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9/6 (2009): 2-9. [ Links ]

Handy, Lowell. Jonah's World: Social Science and the Reading of Prophetic Story. London: Equinox, 2007. [ Links ]

Hexham, Irving and Gerhardus C. Oosthuizen, eds. History and Traditions Centered on Ekuphakameni and Mount Nhlangakazi. Volume 1 of The Story of Isaiah Shembe. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1996. [ Links ]

Lincoln, Andrew. "The Promise and the Failure: Mark 16:7, 8." Journal of Biblical Literature 108/2 (1989): 283-300. [ Links ]

Majavu, Anna. "South Africa's First Nations Give Land Claims Consultation Thumbs Down." The South African Civil Society Information Service (2013). No Pages. Cited 14 March 2014. Online: http://www.sacsis.org.za/site/article/1585. [ Links ]

McClymond, Kathryn. Beyond Sacred Violence: A Comparative Study of Sacrifice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2008. [ Links ]

Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform. "Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Bill." 8 Pages. Cited 4 March 2014. Online: http://www.jutalaw.co.za/media/filestore/2013/10/B35_2013.pdf. [ Links ]

Mofokeng, Takatso. "Black Christians, the Bible and Liberation." Journal of Black Theology 2 (1988): 34-42. [ Links ]

Mosala, Itumeleng J. Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology in South Africa. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989. [ Links ]

Nelson, Alissa J. Power and Responsibility in Biblical Interpretation: Reading the Book of Job with Edward Said. Sheffield: Equinox 2012. [ Links ]

Nzimande, Makhosazana K. "Reconfiguring Jezebel: A Postcolonial Imbokodo Reading of the Story of Naboth's Vineyard (1 Kings 21:1-16)." Pages 223-58 in African and European Readers of the Bible in Dialogue: In Quest of a Shared Meaning. Edited by Hans de Wit and Gerald O. West. Leiden: Brill, 2008. [ Links ]

Peires, Jeffery B. "The Central Beliefs of the Xhosa Cattle-Killing." Journal of African History 28 (1987): 43-63. [ Links ]

______. The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-7. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Person, Raymond F. "The Role of Nonhuman Characters in Jonah." Pages 85-90 in Exploring Ecological Hermeneutics. Edited by Norman C. Habel and Peter Trudinger. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008. [ Links ]

Robins, Steven. "Land Struggles and the Politics and Ethics of Representing 'Bushman' History and Identity." Kronos: Southern African Histories 26 (2000): 56-75. [ Links ]

Ryu, Chesung Justin. "Silence as Resistance: A Postcolonial Reading of the Silence of Jonah in Jonah 4.1-11." Journal for the study of the Old Testament 34/2 (2009): 195-218. [ Links ]

Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto and Windus, 1993. [ Links ]

Sasson, Jack M. Jonah: A New Translation with Introduction, Commentary, and Interpretation. The Anchor Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1990. [ Links ]

Schapera, Isaac and John L. Comaroff. The Tswana. Revised ed. London and New York: Kegan Paul International, 1991. [ Links ]

Shemesh, Yael. "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11): The Function and Status of Animals in the Book of Jonah." The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 10/6 (2010): 2-26. [ Links ]

Sherwood, Yvonne. A Biblical Text and Its Afterlives: The Survival of Jonah in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

Thom, Hendrik B., ed. 1651-1655. Volume 1 of Journal of Jan Van Riebeeck. Cape Town and Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema, for The van Riebeeck Society, 1952. [ Links ]

Timmer, Daniel. "The Intertextual Israelite Jonah Face À L'empire: The Post-Colonial Significance of the Book's Contexts and Purported Neo-Assyrian Context." The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9/9 (2009): 2-22. [ Links ]

Trible, Phyllis. Rhetorical Criticism: Context, Method, and the Book of Jonah. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994. [ Links ]

Ukpong, Justin S. "Developments in Biblical Interpretation in Africa: Historical and Hermeneutical Directions." Pages 11-28 in The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories and Trends. Edited by Gerald O. West and Musa Dube. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2000. [ Links ]

West, Gerald O. "African Culture as Praeparatio Evangelica: The Old Testament as Preparation of the African Post-Colonial." Pages 193-220 in Postcolonialism and the Hebrew Bible: The Next Step. Edited by Roland Boer. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013. [ Links ]

______. "Biblical Hermeneutics in Africa." Pages 21-31 in African Theology on the Way: Current Conversations. Edited by Diane B. Stinton. London: SPCK, 2010. [ Links ]

______. "Difference and Dialogue: Reading the Joseph Story with Poor and Marginalized Communities in South Africa." Biblical Interpretation 2 (1994): 152-70. [ Links ]

______. "Early Encounters with the Bible among the Batlhaping: Historical and Hermeneutical Signs." Biblical Interpretation 12 (2004): 251-81. [ Links ]

______. "Interpreting 'the Exile' in African Biblical Scholarship: An IdeoTheological Dilemma, in Postcolonial South Africa." Pages 247-67 in Exile and Suffering: A Selection of Papers Read at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the Old Testament Society of South Africa OTWSA/OTSSA, Pretoria August 2007. Edited by Bob Becking and Dirk J. Human. Leiden: Brill, 2009. [ Links ]

______. "Liberation Hermeneutics." Pages 507-15 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Steven L. McKenzie. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Gerald O. West

School of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics, & Ujamaa Centre, University of KwaZulu-Natal

1 Gerald O. West, "Difference and Dialogue: Reading the Joseph Story with Poor and Marginalized Communities in South Africa," BibInt 2 (1994): 152-70.

2 Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff, Christianity, Colonialism and Consciousness in South Africa (vol. 1 of Of Revelation and Revolution; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); John L. Comaroff and Jean Comaroff, The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier (vol. 2 of Of Revelation and Revolution; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

3 Comaroff and Comaroff, Christianity, 145.

4 Comaroff and Comaroff, Dialectics, 121-26.

5 Jonathan A. Draper, "For the Kingdom Is inside of You and It Is Outside of You": Contextual Exegesis in South Africa (Lk. 13:6-9)," in Text and Interpretation: New Approaches in the Criticism of the New Testament (ed. Patrick J. Hartin and Jacobus H. Petzer; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1991), 235-57; Jonathan A. Draper, "Old Scores and New Notes: Where and What Is Contextual Exegesis in the New South Africa?" in Towards an Agenda for Contextual Theology: Essays in Honour of Albert Nolan (ed. McGlory T. Speckman and Larry T. Kaufmann; Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2001), 148-68; Gerald O. West, "Interpreting 'the Exile' in African Biblical Scholarship: An Ideo-Theological Dilemma in Postcolonial South Africa," in Exile and Suffering: A Selection of Papers Read at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the Old Testament Society of South Africa OTWSA/OTSSA, Pretoria August 2007 (ed. Bob Becking and Dirk J. Human; Leiden: Brill, 2009), 247-67; Gerald O. West, "Biblical Hermeneutics in Africa," in African Theology on the Way: Current Conversations (ed. Diane B. Stinton; London: SPCK, 2010), 21-31.

6 Justin S. Ukpong, "Developments in Biblical Interpretation in Africa: Historical and Hermeneutical Directions," in The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories and Trends (ed. Gerald O. West and Musa Dube; Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2000), 24.

7 Ukpong, "Developments."

8 Irving Hexham and Gerhardus C. Oosthuizen, eds., History and Traditions Centered on Ekuphakameni and Mount Nhlangakazi (vol. 1 of The Story of Isaiah Shembe; Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press,1996), 224-25.

9 Kwame Bediako, Christianity in Africa: The Renewal of a Non-Western Religion (Edinburgh and Maryknoll, N.Y.: Edinburgh University and Orbis, 1995), 91-92; for a fuller discussion see Gerald O. West, "African Culture as Praeparatio Evangelica: The Old Testament as Preparation of the African Post-Colonial," in Postcolonialism and the Hebrew Bible: The Next Step (ed. Roland Boer; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 193-220.

10 Gerald O. West, "Early Encounters with the Bible among the Batlhaping: Historical and Hermeneutical Signs," BibInt 12 (2004): 251-81.

11 Alissa J. Nelson, Power and Responsibility in Biblical Interpretation: Reading the Book of Job with Edward Said (Sheffield: Equinox 2012), 58. Here and below I follow the contours of Jones Nelson's astute biblical studies appropriation of Said.

12 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 63, note 43.

13 Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (London: Chatto and Windus, 1993), 19; cited by Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 62-63.

14 Said, Culture, 63.

15 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 63.

16 For Said's insistence on the latter's inclusion see Said, Culture, 63.

17 Said, Culture, 36; cited by Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 66.

18 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 66.

19 Said, Culture, 58; cited by Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 66.

20 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 66.

21 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 67; quoting Said, Culture, 113.

22 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 74.

23 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 79.

24 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 87. In many respects the Old Testament Society of South Africa, particularly since the late 1980s, has been such a contrapuntal space. It is in this space that Herrie van Rooy has been one of my contrapuntal companions, bringing other kinds of biblical scholarship into dialogue with mine. I offer this article in his honour.

25 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 101.

26 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 107.

27 Nelson, Power and Responsibility, 118.

28 Duncan Brown, "Religion, Spirituality and the Postcolonial: A Perspective from the South," in Religion and Spirituality in South Africa: New Perspectives (ed. Duncan Brown; Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2009), 9.

29 Takatso Mofokeng, "Black Christians, the Bible and Liberation," JBT 2 (1988): 40.

30 Gerald O. West, "Liberation Hermeneutics," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation (ed. Steven L. McKenzie; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 507-15.

31 See for example Itumeleng J. Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology in South Africa (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989).

32 See for example Musa W. Dube, Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2000); Makhosazana K. Nzimande, "Reconfiguring Jezebel: A Postcolonial Imbokodo Reading of the Story of Naboth's Vineyard (1 Kings 21:116)," in African and European Readers of the Bible in Dialogue: In Quest of a Shared Meaning (ed. Hans de Wit and Gerald O. West; Leiden: Brill, 2008), 223-58.

33 I am drawing here on Cari Carpenter and K. Hyoejin Yoon's elaboration of Walter Benjamin's work on juxtaposition; see Cari M. Carpenter and K. Hyoejin Yoon, "Rethinking Alternative Contact in Native American and Chinese Encounters: Juxtaposition in Nineteenth-Century Us Newspapers," CL 41/1 (2014): 8-42.

34 Phyllis Trible, Rhetorical Criticism: Context, Method, and the Book of Jonah (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994): .

35 Andrew Lincoln, "The Promise and the Failure: Mark 16:7, 8," JBL 108/2 (1989): 283-300.

36 Ehud Ben Zvi, "Jonah 4.11 and the Metaprophetic Character of the Book of Jonah," JHebS 9/5 (2009): 2. See also Ehud Ben Zvi, Signs of Jonah: Reading and Rereading in Ancient Yehud (JSOTSup 367; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003), 14, note 1. In many respects the article builds on the work done in the book.

37 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 2-3.

38 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 3.

39 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 4.

40 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 5, note 10.

41 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 5.

42 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 6-7.

43 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 8.

44 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 8 - 9.

45 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 10.

46 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 10.

47 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 10.

48 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 10-11.

49 Ben Zvi, "Jonah," 12-13.

50 Philippe Guillaume, "Rhetorical Reading Redundant: A Response to Ehud Ben Zvi," JHebS 9/6 (2009): 2.

51 Guillaume, "Rhetorical Reading Redundant," 8. See also Philippe Guillaume, "The End of Jonah Is the Beginning of Wisdom," Bib 87 (2006): 243-50.

52 Guillaume, "Rhetorical Reading Redundant," 5-6.

53 Guillaume, "Rhetorical Reading Redundant," 6. Citing Yvonne Sherwood's work concerning "the Christian colonization of the book of Jonah," he includes later Christian readers in this category, for whom "Jonah prefigures the forgiveness offered through Christ"; see Guillaume, "Rhetorical Reading Redundant," 9; and Yvonne Sherwood, A Biblical Text and Its Afterlives: The Survival of Jonah in Western Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

54 I will return to notions of postcolonial appropriation later in this article.

55 Thomas M. Bolin, "Jonah 4,11 and the Problem of Exegetical Anachronism," SJOT 24/1 (2010): 100.

56 Yael Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11): The Function and Status of Animals in the Book of Jonah," JHebS 10/6 (2010): 3.

57 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 3-4.

58 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 4. She draws here on the ecological hermeneutic work of Raymond F. Person, "The Role of Nonhuman Characters in Jonah," in Exploring Ecological Hermeneutics (ed. Norman C. Habel and Peter Trudinger; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008), 85-90.

59 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 8.

60 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 5-8.

61 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 17.

62 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 17.

63 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 17.

64 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 17.

65 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 18.

66 See also Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 104-06.

67 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 20-22.

68 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 22.

69 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 24.

70 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 24.

71 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 25.

72 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 25.

73 Shemesh, "'And Many Beasts' (Jonah 4:11)," 25, note 91.

74 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 99.

75 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 100.

76 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 100. Though he does not offer a fully-fledged ecological reading of the final phrase, Raymond Person counters allegations of exegetical anachronism by arguing that "we cannot assume that we are the only humans in every time and place that have questioned the value of anthropocentrism"; see Person, "The Role," 90.

77 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 100.

78 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 100-01.

79 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 103, note 17. See especially Kathryn McClymond, Beyond Sacred Violence: A Comparative Study of Sacrifice (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2008).

80 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 103.

81 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 103.

82 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 104, 06.

83 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 106.

84 Bolin, "Jonah 4,11," 106. See also Lowell Handy, Jonah's World: Social Science and the Reading of Prophetic Story (London: Equinox, 2007), 92, cited by Bolin.