Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.27 n.2 Pretoria 2014

ARTICLES

Subversion of power: Exploring the Lion metaphor in Nahum 2:12-141

Wilhelm J. Wessels

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The short book of Nahum has posed many questions to the scholarly community. For many the book represents an unacceptable display of nationalism and for others the violence in Nahum is too much to bear. The book also stirs emotions with its humiliating references to women to depict weakness and rejection. The book of Nahum also raises the question of YHWH as the aggressor committing acts of violence. These issues are all valid concerns that need to be entertained by scholars. However, the poetic nature of the Nahum text cannot go unnoticed. The view taken is that Nahum should be read as "resistance poetry " similar to struggle poems and songs that function in oppressive contexts. The argument promoted in this article is that the rhetoric of the book serves the purpose of enticing the Judean people to imagine victory in spite of their oppression and victimisation by the Assyrian forces. The text of Nahum is an excellent display of power battles with the sovereign power YHWH overpowering the Assyrian powers with Nineveh and the Assyrian king as symbols of power. YHWH acts on behalf of the Judean people, who feel powerless in their confrontation with the Assyrians. With this in mind, it will be illustrated that some metaphors in Nahum are used as a means to undermine the power of the enemy. A case will be put forward that the metaphor of the lion, which represents power par excellence, is used in Nah 2:12-14 in a taunt song to subvert the idea of power inherent in this very image. The idea is to illustrate how a metaphor depicting power is used creatively to achieve the exact opposite by subverting that power.

A INTRODUCTION2

The book of Nahum has posed many questions to the scholarly community. For many the book represents an unacceptable display of nationalism and for others the violence in Nahum is too much to bear. The book also stirs emotions with its humiliating references to women to depict weakness and rejection. The book of Nahum also raises the question of YHWH as the aggressor committing acts of violence. These issues are all valid concerns that need to be entertained by scholars.

However, the poetic nature of the Nahum text cannot go unnoticed.3 Although Nahum is a short book, one should not underestimate the multifaceted nature of the book. It is presented in the canon of the HB as a prophetic book, but the literary splendour is even more striking and more significant than regarding it as prophetic literature in the classical sense of the word. Han4 has indicated that the book of Nahum was in particular attractive to those interpreters who held to a view of the future realisation of these prophecies. The argument presented here is that the emphasis should rather be on the literary qualities of Nahum, than on a restrictive view of its prophetic significance. In a way Nahum is similar to the book of Jonah which should be appreciated more for its literary significance rather than for its so-called prophetic classification. The power of the book Nahum is in its message carried by the artistic literary qualities of the text.5 McConville remarks "The power of the prophecy as rhetoric lies in its effective use of poetry and metaphor."6 This article intends to illustrate how the metaphor of the lion is effectively used to subvert the power of the Assyrian leadership. The key to arrive at some form of understanding of the Nahum text is not to be found in its prophetic classification, but in its poetic nature.

The viewpoint expressed above of reading Nahum as the work of a literary artist opens up the possibility to regard the text not so much as an attempt to present a historical account of events in eighth century Judah, but a literary work7 using historical events from a specific period to address certain issues.8 These issues concern power and contra-powers. They concern oppression, violence and in particular how all of these relate to the deity, in the case of Nahum, YHWH . Rogerson9 says of Nahum "the book contains magnificent imagery as it contrasts the awesome majesty of God with the ultimate nothingness of some of the highest achievements of human civilization up to that point in human history." Although this is an accurate observation of what the book is all about, modern interpreters still need to be critical of the close association of YHWH to acts of violence. To conclude as Robertson10 does when he says of the message of Nahum "this unbroken note of judgment may provide a ministry today that is greatly needed by those who put their trust in the one true God. A recognition of the reality of divine vengeance provides a sobriety that ought always to characterize the relations of human beings and nations," is unacceptable and dangerous. In the next paragraph I will suggest a way of reading the Nahum text that will take account of the nature of the book of Nahum.

The view taken here is that Nahum should be read as a form of "resistance poetry" similar to struggle poems and songs that function in oppressive contexts.11 The idea of resistance corresponds with the view expressed by Timmer12 that the book of Nahum is "a minority voice that bears on the place of the seventh century kingdom of Judah in the imperialism of the Ancient Near East." He further says "not only is there a resistance to and rejection of the Assyrian Other, but Nahum even contemplates the elimination of the Other in the near future."13 The association of Nahum with the idea of resistance is therefore not strange. In many instances the so-called "resistance poetry" or "songs of resistance" express a yearning for liberation and freedom of oppression. It is not surprising to find that these calls for liberation have a religious undertone with a call to the deity to intervene in circumstances. The resistance songs or poetry usually have a provocative nature with the purpose of uniting people to the struggle and the vision for liberation. If the contents of these songs or poetry are taken literally, it will leave many listeners disturbed and uneasy. If understood correctly, it seems that the intention is not so much to mobilise people to commit acts of violence, although the risk of violence is always looming, but to unite people in striving towards a desirable outcome of freedom.14 It serves the purpose of lifting people who are dismayed and hopeless out of such a mood to perceive a possible outcome of liberation and freedom. This view of comparing current day resistance songs and poetry to an ancient text such as Nahum can be regarded as perhaps reading too much into the text with which we are dealing. However, entertaining such a comparison can serve the purpose of making the text of Nahum relevant to a society in which oppression is a reality. If there is some value in the view presented that the Nahum text, displaying a historical situation of Assyria oppressing and threatening the people of Judah, was appropriated in a post-exilic historical context in which the people experienced oppression or lack of freedom,15 then it is not far-fetched to assume that people in contexts of oppression could relate to the Nahum text. It should be understood in no uncertain terms, that relating the text of Nahum to a modern day context of oppression, is not a matter of condoning violence or the incitement to commit acts of violence in the name of a deity. The idea of the comparison is an honest attempt to understand how such similar forms of text functioned in a particular society and to show that there are similarities even in modern day societies. O'Brien16 has acknowledged the worth of reading Nahum as "resistance poetry," but also justly mentioned that the complexities of the text of Nahum and the issues involved in the book need to be treated with great circumspection. The text of Nahum is complex and certainly went through processes of editing which are difficult to reconstruct with any sense of certainty.17 This article will consider the complexities inherent in Nah 2:12-14. The results of the text analysis with the lion metaphor in focus will be interpreted within the framework of resistance to power and oppression. A comprehensive treatment of all the issues involved in engaging the text of Nahum is not possible in this article of limited scope. The appropriation of such texts should be submitted to stringent ideological critical scrutiny and evaluated in terms of ethical norms and acceptable behaviour ranging in a particular society. This is not possible within the scope of this article and should be considered at some point in time.

The argument promoted in this article is that the rhetoric of the book serves the purpose of enticing the Judean people to imagine victory in spite of their oppression and victimisation by the Assyrian forces.18 The text of Nahum is an excellent display of power battles with the sovereign power YHWH overpowering the Assyrian powers with Nineveh and the Assyrian king as symbols of power. YHWH acts on behalf of the Judean people, who feel powerless in their confrontation with the Assyrians. It should be acknowledged that Assyria is stereotyped as the evil oppressor and Judah stereotyped as the oppressed victim.19 With this in mind, it will be illustrated that some metaphors in Nahum are used as a means to undermine the power of the enemy. A case will be put forward that the metaphor of the lion, which represents power par excellence, is used in Nah 2:12-14 in a taunt song to subvert the idea of power inherent in this very image. The idea is to illustrate how a metaphor depicting power is used creatively to achieve the exact opposite by subverting that power.

B NAHUM 2:12-14 IN CONTEXT

2:1-2:14 The downfall of Nineveh

- 2:2-3 Salvation and liberation

- 2:4-11 Conquest and plundering of Nineveh

- 2:12-13 Satirical song about Nineveh and its king

- 2:14 Threatening speech about Nineveh

Nahum 2 describes a scene in which an invading enemy wages battle against Nineveh.20 At first, in an endeavour to create suspense, the name of the city (Nineveh) is not mentioned. It only becomes clear that the battle is actually against Nineveh when the city is mentioned in 2:9. In 2:4-5 the fearsomeness of the invading force is portrayed by describing their soldiers with their armoury that includes shields, spears and even chariots. Under this onslaught all Nineveh's defences fail (2:6-9) and she is ransacked. The reactions to this are cries of desperation, resulting in 2:11 with a depiction of the people of the once dominating power with melting hearts, knees that give way, trembling bodies and pale faces - in a terrible state. Nahum 2:12-14, the focus of this article, uses the lion metaphor to describe the eventual fate of the leadership of Nineveh (Assyria) and YHWH 's involvement in their demise. Han21 regards these verses as "a dirge over the destroyed city."22 Perhaps it will be more accurate to say that these verses mock the dire situation of the city. The focus however seems to be on the leadership of Nineveh, since there is a gradual build up from describing the fate of the city (2:6-10) to the impact of the devastation on people of Nineveh (2:11) and finally the destiny of the leadership of the city (2:12-14). An attempt will be made to substantiate this view in the main section of this article.

C ANALYSIS OF NAHUM 2:12-14

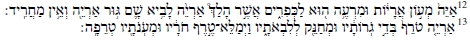

11 Where is the lions' den (lair) now, den the feeding place of the young lions, feeding place where the lion goes, the lioness was there, the lion's cub, with no one to cause fear.

12The lion has torn enough for his whelps and strangled (prey) for his lionesses; he has filled his caves with prey caves and his dens (lairs) with torn flesh. dens

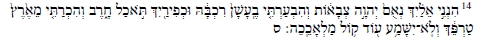

13 See, I am against you, says the LORD of hosts, I will burn your chariots in smoke, and the sword shall devour your young lions; I will cut off from the earth your tearing, and the voice of your messengers shall be heard no more.23

1 Text Analysis of Nahum 2:12-14

The sections preceding Nah 2: 12-14 not only portray the demise of the city Nineveh, but also the devastating emotional effects on the people of Nineveh. The new section introduced in v. 12 starts with a particle interrogative, posing questions regarding the den and the feeding place of lions. There is therefore a shift from the city and the people to the image of lions and their prey. In this unit vv. 12 and 13 belong together, followed by v. 14 introduced by a particle interjection with the first person singular suffix. The verbs to follow are also referring to a first person singular subject, to YHWH as the one who will take action. Verse 14 not only announces judgement as response to the destructive actions of the lions, but serves as the concluding climax to ch. 2 with the focus on YHWH 's actions. A new section is introduced in Nah 3:1 by the particle interjection הוי, setting a tone of lament. The focus shifts to a lament of the city in total disarray due to social depravity.

As mentioned before, v. 12 commences with a question about the den and feeding place of a lion. In the context of the chapter, this should be taken as a reference to Nineveh that is no longer a safe haven.24 The question implies that these places no longer exist. Some propose that the word "feeding place" (מרעה) should be replaced by the word "cave"  25 There seems to be a chiasm consisting of: den (a) feeding place (b) - caves (b) dens (a) that serve the purpose of binding vv. 12 and 13 together. The suggestion by the Septuagint (lxx) and other versions that the word "lioness" be replaced by the verb "to go" should not be accepted because according to Spronk26 there is strong support from the text 4QpNah that the word lioness should remain in the Masoretic Text (MT) and also the use of lioness and young lions next to each other in Isa 5:29.

25 There seems to be a chiasm consisting of: den (a) feeding place (b) - caves (b) dens (a) that serve the purpose of binding vv. 12 and 13 together. The suggestion by the Septuagint (lxx) and other versions that the word "lioness" be replaced by the verb "to go" should not be accepted because according to Spronk26 there is strong support from the text 4QpNah that the word lioness should remain in the Masoretic Text (MT) and also the use of lioness and young lions next to each other in Isa 5:29.

Various words to describe the lion family appear in v. 12 and continue in v. 13. There is mention of the male lion (twice), the young lions, the lioness and the unweaned cub of the lion in v. 12. The male lion and the lioness are again mentioned in v. 13 and then also another reference to a lion whelps, supposedly weaned whelps. In v. 14 the young lions are mentioned again.

From the scene describing the settlement of the lion family in v. 12, the focus shifts in v. 13 to the lions' feeding. The root טרף is repeated no less than three times in this verse, first as a qal verb participle masculine singular form of the word (to tear), then as a noun masculine singular absolute (prey) and in the third instance as a noun feminine singular absolute (prey). There is a fourth reference to the root טרף in v. 14 (טרף noun common masculine singular construct suffix 2nd person feminine singular) which clearly demonstrates that this word is a key concept in the section and run as a common thread through the section, linking vv. 12-14 together. I agree with Spronk27 that the different forms that are used for "cub" and "lioness" are deliberately employed by the poet who composed this verse. Most probably the poet also intentionally used the male and female forms of the same words (see the use of prey first in the masculine form in v. 13b and then at the end of the verse in the feminine form) as a form of poetic license. In a lengthy discussion on the issue of gender and identity in the book of Nahum, Lanner28 has overviewed many of the different views held by scholars. There seems to be no consensus on a solution for the problem, but Lanner prefers to retain the ambiguity caused by the changes of gender in some verses.29 At one stage she remarks "one can only hope that for clarity's sake the book of Nahum was written as a chorus for different voices."30

Nahum 2:12-14 ends in v. 14 with an announcement of judgement. The verse is introduced by a particle interjection with first person singular suffix. YHWH in the first person singular is the subject of the verbs in this verse and the object is in the second person feminine singular. The feminine object referred to in v. 14 is probably the city Nineveh. There are also three sets of bicola as was the case in v. 11. The introductory formula "I am against you"31 (הנני אליך) is known a as the "Herausforderungsformel" that serves the purpose of YHWH summoning the opponent to a deciding battle.32 Many different suggestions which seem attractive are made for a better reading of the word "her chariot," but with the Vulgate, the MT version should remain as is, since there are several other references to the word chariot in the book. Spronk33 has indicated that the poet probably intended to match the gender of the nouns עשן ו-כפירקן - (masculine) with חרב ־ ךכבה (feminine).34 The suggestion to regard טרפך not as a noun, but as an infinitive makes sense. This can happen if a slight change in the vocalisation is made.35 The change will imply that the act of tearing is perceived instead of the focus on the prey. The Hebrew form of the reference to the messengers is unfamiliar and therefore leads to many suggested amendments by scholars.36 None really seem to convince, therefore it is perhaps wise to accept the MT as it stands and assume that the poet intended this unfamiliar form. The reference to messenger however corresponds to the reference of the messenger in 2:1.

2 Exposition of Nahum 2:12-14

The questions to be answered now are to what do the settlement references refer, who are the different categories of lion and who are the young lions mentioned together with the sword, and finally what or who are the prey?

Nahum 2:12-13 will not make much sense if it is read in isolation. These two verses speak of lions, dens, feeding places and prey. Verse 14 sheds some light on the interpretation of vv. 12 and 13 by indicating that the lions refer to more than fierce animals, but in actual fact to a feminine subject who possesses chariots. This feminine subject also has messengers which signal to the audience or readers that the lions, the prey, the den and feeding places all have referential meaning. The broader context of ch. 2 also reveals that references to the city Nineveh are in the feminine form of the word. There are however differences of opinion whether it is indeed Nineveh that is referred to in v. 12. Coggins37 for instance takes the lion in this verse as a reference to YHWH and the lair to Jerusalem. This seems unlikely since the passages preceding the section under discussion quite clearly talk about Nineveh.38 Nahum 2:9 explicitly refers to Nineveh. If vv. 12 and 13 indeed refer to the city of Nineveh, then the lions most likely refer to the king and his family or even the hierarchy of the Assyrians.39 There is therefore a strong indication in v. 14 that the verdict against the feminine object is against the city of Nineveh. This will make sense when this verse speaks of her chariots that will go up in smoke. The lion motif in v. 14 links back to vv. 12 and 13 and seems to refer to an enemy of YHWH . The messengers would then also be the spokespeople for the city Nineveh as the seat of power. It is then also not far-fetched to assume that the reference to the young lions would probably be to people associated with the city. The references to the prey would therefore also imply that people are in mind.

The text analysis above has revealed various references to lions. The main focus is on the male lion who is the main actor in the scenery painted to the audience and readers of Nah 2: 12-14. Besides references to the male lion, there is also reference to the lionesses, the young lions, the unweaned cubs and whelps or cubs. From the argumentation above it seems logic that the various forms of lions are referring to different categories of people. It seems that the author had the royal family40 and the hierarchy of the Assyrian people in mind.41 The references to the den most probably will then also be to the safe place of these people and in the context of ch. 2 then referring to Nineveh as their safe haven. This city was the place where the people of Assyria felt secure and which they regarded as a place where no enemy could threaten them. They operated from this location to conquer and exploit neighbouring nations.

Verse 13 describes a fearsome wild animal killing at will, providing for all those who are dependent on him and could benefit from his dominance and power. What is described here is a depiction of unmatched brutality and exploitation of people. The lion has torn his prey to pieces, strangled his victims and filled his caves with prey and torn flesh. In the next section the discussion of the lion metaphor will be informed from three different perspectives, namely from the current context in Nahum, from the ANE and HB context and finally from a conceptual point of view.

D ANALYSIS OF THE LION METAPHOR

1 The Lion Metaphor in the Current Context

we can learn a great deal about the lion and the lion family by simply analysing what is at hand in vv. 12 and 13. First of all it is said that the lions have dens and feeding places and secondly that a family structure of lions interdependent from each other is in focus. There is reference to the male lion, the lioness, the young lions, the unweaned cubs and finally the cubs. Verse 12 describes an environment in which the lioness and young lions and cubs could exist without fear from an enemy threatening them.

we also learned from v. 13 that the male lion is regarded as the provider of food and in doing so is portrayed as vicious, fearsome, powerful and crude.42 He has the ability to tear his prey apart and strangles the prey caught by him to death. The lion as a destructive force is emphasised by not simply saying that he kills the prey, but that their flesh were torn apart.

2 The Lion Metaphor in Ancient Near Eastern and Hebrew Bible Context

The brief overview presented here of the occurrence of the lion symbol and metaphor in the ANE and the HB, will inform our understanding of the lion metaphor in Nah 2:12-14. Both the Assyrians and the Israelites formed part of the ane cultural background, therefore their views on lions as a symbol could be quite informative.

It is well documented that lions were renowned in the ANE. Many descriptions and depictions of lions are to be found in Mesopotamia, Egypt and also Israel. Lions were often hunted by the kings of Assyria and Egypt and testify to the greatness of the kings who were able to hunt such ferocious beasts down. Kings who were victorious in battle often presented themselves as mighty lions.43 There are quite a number of references to lions in Israel as well, but these references were more metaphorical in nature.44 Proverbs 30:30 regard lions as fierce and brave. Two of the well-known stories where lions feature prominently are in Judg 14 with the killing of the lion at Samson's wedding and in Dan 6 with Daniel in the pit with lions.

Besides the depictions of real lions, many references to lions as symbols, similes and metaphors in the ANE can be found. Many such references portray the might of either gods or the kings. We find such references in Egypt, Mesopotamia, a few references in Syria and in Palestine. There are many references to YHWH as a lion in the Hebrew Scriptures.45 In Israel princes as well as royalty are portrayed by the symbol of the lion. Prinsloo46 has also shown that the enemies of Israel and individual Israelites relate to the lion symbol. Johnston47 refers to Ezek 32:1-15 where there is reference to the king of Egypt who roams the earth like a lion. It alludes to the strength and the power of the lion, but in this case reversing the metaphor to indicate that the Egyptian king will be hunted down like a lion. Important for the discussion in this article is Isa 5:29 where Assyria is called a "roaring lion" similar to what Nah 2:12-13 does. Johnston48 is convinced that the lion metaphor in Nah 2 alludes to the motif of the lion in Neo-Assyrian literature and art. According to him Assyrian literature and art use this metaphor to depict the king as a mighty warrior and as a relentless hunter.49 He argues that in Nahum the lion metaphor alludes to King Ashurbanipal as a ferocious ruler hunting down his enemies. Lions also served as statues decorating the palace. All of this was to depict the king as powerful. Another important reference is Isa 30:6 where the lion represents danger (also Prov 22:13; 26:13; Cant 4:8; Ps 91:13 and Joel 1:6). The lion symbol also functions as a symbol for strength and courage (2 Sam 1:13 and 17:10).50 As Strawn51 has concluded, "the lion is a trope of threat and power." In the HB the lion image is often used for YHWH, but also frequently to refer to the enemies.

3 The Lion Metaphor as Conceptual Metaphor

It is clear from the context in Nah 2 that the writer wanted to communicate much more than describing what lions do and how they act. The metaphor of the lion has much to offer for our discussion and is a powerful image.

Cognitive linguistics has offered some new insights when referring to metaphors. This approach is interested in "the mental concepts that our minds form and express about the world through language."52 We use language to communicate, but meaning has cognitive concepts as a base. Dobrić53 says that "metaphorical concepts represent interwoven basic structures of human thought, social communication and concrete linguistic manifestation through a rich semantic system based on the human physical, cognitive and cultural experience."54 The function of metaphors is to "conceptualise one element of a conceptual structure using elements of a different conceptual structure."55 Metaphors approached this way should be treated as conceptual constructs. The usual way of looking at metaphors is to regard them as stylistic devices, but the discussion here are interested in the conceptual structures underlying metaphors. Following this line of thinking about metaphors, Jindo has argued that a metaphor however can also function as "a representational component, as a mode of orientation."56 He continues by saying that a metaphor can be very valuable as a creative component, "as a means to convey a poetic insight."57 This article is interested in the underlying cognitive concepts that the poet or a writer wanted to reveal or disclose by using the lion metaphor. In metaphor theory58 the language used to explain how metaphorisation operates is to speak of a source conceptual domain and a target conceptual domain. The source domain is concrete whilst the target domain is more abstract. In terms of the lion metaphor the concept of the lion would be the concrete source domain that is transferred onto the more abstract target, in this case a person. The semantic concept underlying the lion metaphor would then be Lion is a Person, but in more general terms people are animals.59 The question would then be what the conceptual structures situated in the lion source domain are that are mapped onto a person who forms the target domain. If we take into account people's experiences of lions and cultural perceptions of lions, concepts such as power, pride, protection, brutality and danger come to mind.

Not many of us would disagree that these concepts can be associated with the image of a lion. In terms of metaphor theory, the mentioned concrete concepts are intended to be transferred onto human beings as targets. In terms of the context in the book of Nahum, and in particular Nah 2, the people in mind most probably are the king and perhaps the queen, the king's officials and also his military personnel. All of them could be associated with the capital city Nineveh.

If one thinks in conceptual terms about a lioness, most probably concepts such as provision, care, hunter and tenacious come to mind. Young lions would be associated with concepts such as courageous, arrogant, inquisitive and dependent. One would most probably think along the lines of dependence, playfulness and vulnerability as concepts to be associated with lion cubs.

Looking at the lion metaphor from a perspective of cognitive metaphor theory was a worthwhile exercise and provided useful insights. There is however the danger of overanalysing the metaphor. In this regard the context in which the metaphor is applied should set the parameters.

E APPLICATION OF THE LION METAPHOR

The lion metaphor rendered many concepts that are of great value for the exposition and determination of meaning of Nah 2:12-14. Some knowledge was obtained from the context in which the lion family was portrayed and we have gained valuable information of how the lion as a symbol was regarded in the Ancient Near East and in the Hebrew Scriptures. Analysing the lion metaphor as cognitive concepts has also proved worthwhile. Basic concepts associated with lions are power, pride, protection, danger and brutality evolved as source concepts to be transferred in the process of metaphorisation onto the target domain. In referring to Aristotle, Gill60 says the following about cognitive metaphors - "good metaphors will surprise and puzzle us: while they have familiar elements, their relevance and meaning will not be immediately clear." This is true of the lion metaphor in Nahum as well. The lion is not an unfamiliar element, but the meaning in the context in Nah 2:12-14 is not as obvious as it seems at first sight.

In the discussion of the broader context in which we have to read Nah 2:12-14, it became clear that an enemy was threatening the Assyrians, that Nineveh no longer served as a stronghold for the people of Assyria and that the palace was threatened. Scenes of panic and despair are portrayed, women lamenting and people fleeing the city of Nineveh. The city known for its wealth and riches is plundered and robbed of all its precious possessions. Verse 11 is striking and reads as follows: "devastation, desolation, and destruction! Hearts faint and knees tremble, all loins quake, all faces grow pale!" (NRSV). Nineveh used to be a safe haven where the king of Assyria ruled and planned his dominance over his neighbours. It was the place where the spoils of his military campaigns were kept and displayed. What the people of Judah should imagine, is that it is no longer the case. YHWH has intervened for the sake of his people against their oppressor. It is against this background that this short passage in vv. 12-14 should be understood.

Nahum 2:12 asks the question about what happened to the den and feeding place of the lion family. From the context it is clear that the question is about conditions in Nineveh, the place where the king once ruled and the people lived safely. The lion metaphor resembles power, pride, fierceness, danger and provider of sustenance. This is what the metaphor transfers or mapped onto the person, most probably the ruler in Nineveh. The lion in the metaphor had torn the prey apart, providing and stocking up an abundance of food for those dependent on him. In the process of doing so the lion has displayed his mighty power by ferociously killing his prey and strangling his victims. The picture to be imagined here is that of a ruthless and powerful conqueror who caused nations to fear him. As Johnston61 has argued, this description of how the lion went out to kill his prey alludes to the Neo-Assyrian depiction of the king as hunter. What is said about the lion in this metaphor alludes to a ruthless display of power by the ruler of Nineveh over those who have fallen victim to his campaigns. He brought the booty gained to the city and provided wealth and prosperity to everyone who was dependent on him. The metaphor of the lion as source of basic cognitive concepts formed by life and cultural experience found expression in concepts such as power, pride, protection and ferocity. The Assyrian king as ruler has hunted his enemies down, oppressed neighbouring nations, looted their cities and provided wealth and prosperity to the people of Nineveh and Assyrian. The rhetorical question in v. 12 brings the audience and readers to the point where they should ask: is it still the case?

An observation from the text that perhaps should be entertained is how the male lion is portrayed in v. 13. The focus is on the male lion as the main aggressive and powerful hunter. He is described as the one who would tear his prey to pieces, strangle the prey for the lionesses and the one who is the provider of food for the family (pride?) of lions. This portrayal of the lion is somewhat surprising in terms of what the role of lionesses is in reality and the basic concepts associated with the lioness. The real hunters are actually the lionesses who work in tandem to make the kill and provide the food. In a book such as Nahum where gender concerns are a real issue, this observation perhaps shows how power and provision are wrongly associated with males alone. I have attempted to illustrate in the discussion of the various references to the variety of lions, that a variety of different basic concepts can be associated to the various groupings of lions. The text of Nah 2:12-13 however determines that the main focus is on the male lion. This perhaps links up with what O'Brien62 has in mind with the remark about metaphors when she says. "What aspects of this situation does the metaphor obscure or ignore?" The metaphor of the lion in Nahum projects the perspective of the male and it grants power to the male.

The question to be considered is whether the subordinate role of the lionesses in the act of killing the prey and providing the food for the pride is innocent. Perhaps there is more to the underplaying of the role of the lioness than meets the eye. Timmer63 made the point that the role of Nineveh and the goddess Ishtar have overlapped during the time of the reign of King Ashurbanipal. He remarked that Ishtar in Ashurbanipal's reign was associated with economic prosperity as well as victory in war. There is support from Lanner64 for associating the lioness with the goddess. Ishtar's chariot was drawn by a lion and it is said that she also rides the lions. Lanner65 even entertains the possibility that the chariot in v. 14 "belongs to the goddess of Nineveh or is an epithet for a goddess." If this is true, then the possibility should be entertained that the secondary role allotted to the female characters in Nahum and in particular in the metaphor of the lioness is a deliberate ploy by the writer or writers to downplay the power associated with the female goddess. The denial of the female counterpart of the lion, whether it is the queen or the female deity, her rightful share in power associated with the lion metaphor, is then perhaps a deliberate attempt to shame the female component of the society.

There is however a twist in the tale which is already alluded to by the interrogative particle in v. 12. The prophet or poet is asking what has happened to all that can be associated with the lion, what the lion represents and to those who form part of the lion family and their living space. Things were looking good for the lion and those dependent on him (v. 13- abundance), but is it still the case? The answer is no. The question is raised now about the power, dominance and security of the lion. Verse 14 puts everything in perspective.

Verse 14 is introduced by an interjection, indicating that an announcement is about to be made in response to the previous two verses. Rudolph66 states "Am ende nimmt Jahwe selbst das Wort und bestätigt, was sein Prophet gesagt hat." In this verse judgement is announced by YHWH to a second person singular feminine object, in all probability to the city Nineveh. Judgement on the city also entails judgement on the ruler, its officials, the military and the people of the city. Rudolph67 regards the proclamation of judgement as a futuristic event and warns that the lively visionary description should not be misinterpreted as if it already happened. The view promoted in this article is that the prophet is indeed appealing to the imagination of the Judean people as if events have already realised and YHWH 's defeat of the enemy is a done deal. Verse 14 expresses the fact that YHWH has taken action against the stronghold and its inhabitants and will take action by means of burning their chariots and killing the young lions, supposedly the military troops of the Assyrian ruler. The first person singular verbs indicate that YHWH is the one taking action against this powerful ruler and his city and that he will break their power by destroying the military equipment like the chariots and cause the soldiers to die by the sword, meaning in battle. In the process the king will lose his power and will no longer be able to dominate his prey, meaning people of other nations, including the people of Judah. The powerful lion will become powerless when faced with the sovereign power of YHWH . The messengers who used to come back with messages of victory in battle, their voices will be silenced because there will be no good news to announce.68 The ruler who took pride in the splendour of his city and the force of his military will experience how this will fade away because of his encounter with the real true power, YHWH . What was implied in v. 12 with the question has come to reality. The powerful and ruthless ruler who once went out on campaigns displaying his power by tearing his enemies to pieces is no longer in a position to do so. Once he embarked on campaigns, destroying and subduing his enemies and looting their cities, but is no longer able to do so.

The function of the lion metaphor was to place the focus on the aspect of power and related to that the consequences of the power exercised. The association of the lion as a symbol of power in the Assyrian context proved to be a suitable image to use to drive home a verdict on this oppressive power.

In Nah 2:12-14 the poet has craftily used the technique of reversal to drive his message home. What was admired and feared about the lion will change with YHWH 's intervention. Whereas the symbol of the lion represented power and pride, the writer has used the same metaphor to allude to the loss of power and pride. The metaphor of the lion is used in this context as a means of undermining the power of Judah's enemy. The very symbol that represents power and pride is used to illustrate the loss of power and pride. The hunter will become the hunted. Timmer69 remarks on 2:14 saying, "Yahweh brings Assyria's propagandistic and self-glorifying use of leonine language against it in an ironic threat of total destruction." The metaphor of the lion in Nah 2:1214 takes the form of a taunt song to subvert the idea of power inherent in this very image.70 A metaphor depicting power is used creatively to achieve the exact opposite by subverting that power. Not only had the king lost his power, but all others depending on his power lost whatever power, position and pride they had. once he provided for everyone, but he will be humiliated by no longer being able to do so. This includes the royal household, Nineveh, the hierarchy and the female deity, in sum Assyria as such.

F CONCLUSION

The case was made to read the book of Nahum as perhaps similar to resistance literature, such as resistance poetry and resistance songs. I admit that the impetus to do so is due to contextual experiences. It is also an honest attempt to make some sense of a beautifully written, but disturbing text. The desire to gain some form of understanding of the text does not imply in any sense condoning the content. What should be acknowledged is that though the content of this short book makes uneasy reading, it does have the benefit of putting important issues such as violence and gender matters on the table for discussion.

Language is a powerful way of expressing ideas and communicating to people. Poetic language is even more effective in gripping the imagination of people and to effect change in people's minds and attitudes. Nahum 2:12-14 is an excellent example of how the reversal of the implied meaning of a metaphor is used mockingly to subvert the power of an oppressing enemy.71 McConville fittingly remarks "The power of prophetic poetry to evoke the fine line between great strength and utter weakness is nowhere greater than here."72 Nahum appeals to an oppressed people to imagine how the power and pride of the ruler can be lost through an intervention by YHWH the sovereign power. Stulman & Kim73 render support to the idea of reading Nahum as songs and poetry by saying "The poetic images of devastation of the seemingly impregnable city of Nineveh in Nahum 2:1-13 are graphic expressions of triumph, songs chanted by the oppressed. . . " The sheer enjoyment of mockingly singing or reciting a poem on the demise of the power of an oppressor also affects the subversion of that ruler's power and pride.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Basson, Alec. "'Rescue Me from the Young Lions': An Animal Metaphor in Psalm 35:17." Old Testament Essays 21/1 (2008): 9-17. [ Links ]

Coggins, Richard J. and Re'emi, S. Paul. Israel Among the Nations: A Commentary on Nahum, Obadiah, Esther. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1985. [ Links ]

Coggins, Richard and Jin H. Han. Six Minor Prophets Through the Centuries. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [ Links ]

DesCamp, Mary T. Metaphor and Ideology: Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum and Literary methods through a cognitive lens. Leiden: Brill, 2007. [ Links ]

Dobrić, Nikola. "Theory of Names and Cognitive Linguistics - The Case of the Metaphor." Filozofija i društvo 21/1 (2010): 31-41. [ Links ]

Floyd, Michael H. Minor Prophets Part 2. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2000. [ Links ]

Gill, Roger. Theory and Practice of Leadership. London: Sage Publications, 2011. [ Links ]

Jindo, Job Y. Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered: A Cognitive Approach to Poetic Prophecy in Jeremiah 1-24. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2010. [ Links ]

Johnston, Gordon H. "Nahum's Rhetorical Allusions to the Neo-Assyrian Lion Motif." Bibliotheca Sacra 158 (2001): 287-307. [ Links ]

Lanner, Lauren. "Who Will Lament Her?" The Feminine and the Fantastic in the Book of Nahum. New York: T & T Clark, 2006. [ Links ]

McConville, J. Gordon. Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Prophets. Downers Grove, I11.: InterVarsity Press, 2002. [ Links ]

McGlone, Matthew S. "What is the Explanatory Value of Conceptual Metaphor?" Language & Communication 27/2 (2007): 109-126. [ Links ]

O'Brien, Julia M. Nahum. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002. [ Links ]

______. "Nahum-Habakkuk-Zephaniah: Reading the 'Former Prophets' in the Persian Period." Interpretation 61/2 (2007): 168-183. [ Links ]

______. Challenging Prophetic Metaphor: Theology and Ideology in the Prophets. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2008. [ Links ]

Pinker, Aron. "Nahum - The Prophet and his Message." Jewish Bible Quarterly 33/2 (2005): 81-90. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Gert T. M. "Lions and Vines: The Imagery of Ezekiel 19 in the Light of Ancient Near-Eastern Descriptions and Depictions." Old Testament Essays 12/2 (1999): 339-359. [ Links ]

Roberts , Jim J. M. Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah: A Commentary. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1999. [ Links ]

Robertson, O. Palmer. The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1990. [ Links ]

Rogerson, John W. "Nahum." Pages 708-709 in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Edited by James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Rudolph, Wilhelm. Micha - Nahum - Habakuk - Zephanja. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn, 1975. [ Links ]

Serfontein, Johan and Wilhelm J. Wessels. "Hearing the 'Good News' in the Book of Nahum: A Socio-Rhetoric Enquiry." Journal for Semitics 22/1 (2013): 177-192. [ Links ]

Spronk, Klaas. Nahum. Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1997. [ Links ]

Strawn, Brent A. What is Stronger than a Lion? Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg, 2005. [ Links ]

Stulman, Louis and Hyun C. P. Kim. You are My People: An Introduction to Prophetic Literature. Nashville: Adingdon Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Timmer, Daniel C. "Boundaries Without Judah, Boundaries Within Judah: Hybridity and Identity in Nahum." Horizons in Biblical Theology 34 (2012): 173-189. [ Links ]

Troxel, Ronald L. Prophetic Literature: From Oracles to Books. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. [ Links ]

Wessels, Wilhelm. "Nahum: An Uneasy Expression of Yahweh's Power." Old Testament Essays 11/3 (1998): 615-628. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Prof. wilhelm J. wessels

Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, University of South Africa

P. O. Box 392, Unisa, 0003

Email: wessewj@unisa.ac.za

1 In English translations this section is Nah 2:11-13.

2 This article is dedicated to Professor Herrie van Rooy, a highly respected scholar and true servant of the ot guild both locally and internationally.

3 In Richard Coggins and Jin H. Han, Six Minor Prophets through the Centuries (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 9, Han refers to Nahum as "the 'poet laureate' of the Minor Prophets." He continues to mention several authors and sources who have lauded the poetic quality of the book of Nahum.

4 Coggins and Han, Six Minor Prophets, 8.

5 J. Gordon McConville, Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Prophets (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2002), 208.

6 McConville, Exploring the Old Testament, 208.

7 Ronald L. Troxel, Prophetic Literature: From Oracles to Books (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 114 argues that there is ample evidence of scribal activity in the book and therefore regards Nahum as a literary creation. See also Michael H. Floyd, Minor Prophets Part 2 (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2000), 17.

8 Cf. Julia M. O'Brien, Challenging Prophetic Metaphor: Theology and Ideology in the Prophets (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2008), 22. Notice should also be taken of the view of Floyd, Minor Prophets 2,14 who regards the genre of Nahum as a maśśā, defined as "a kind of revelation that serves to interpret the present applicability of a previous revelation."

9 John W. Rogerson, "Nahum," in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (ed. James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson; Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2003), 708.

10 O. Palmer Robertson, The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1990), 56-57.

11 I have suggested and argued this approach and coined the terminology in an article in 1998, cf. Wilhelm Wessels, "Nahum: An Uneasy Expression of Yahweh's Power," OTE 11/3 (1998): 615-628.

12 Daniel C. Timmer, "Boundaries Without Judah, Boundaries Within Judah: Hybridity and Identity in Nahum," HBT 34 (2012): 174.

13 Timmer, "Boundaries Without Judah," 176.

14 Louis Stulman and Hyun C. P. Kim, You are My People: An Introduction to Prophetic Literature (Nashville: Adingdon Press, 2010), 219 call the book of Nahum "a survival text that invites readers to celebrate divine shalom." The Nahum text reflects the pain and suffering of an oppressed people.

15 Cf. Julia M. O'Brien, "Nahum-Habakkuk-Zephaniah: Reading the 'Former Prophets' in the Persian Period," Int 61/2 (2007): 175-176.

16 Julia M. O'Brien, Nahum (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002), 112-117.

17 Cf. Floyd, Minor Prophets 2, 4-9 who offers an insightful overview of opinions on the composition of the Nahum text.

18 O'Brien, Nahum, 22-23 also reads the text of Nahum with and interest of "how names rhetoric invites readers to envision Assyria, Judah, Yahweh, and other characters, and how those images shape a reader's thoughts and, perhaps, behaviors." She says "I'm interested not only in what Nahum does to the reader but also how he does it. What are the tricks of Nahum's rhetorical trade?"

19 Timmer, "Boundaries Without Judah," 178-179; 188-189.

20 Coggins and Han, Six Minor Prophets, 27-29.

21 Coggins and Han, Six Minor Prophets, 29.

22 Wilhelm Rudolph, Micha - Nahum - Habakuk - Zephanja (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn, 1975), 173 calls it a "Spottlied auf Ninive."

23 The translation is informed by several translations, but structuring is that of the author.

24 Robertson, Books of Nahum, 95.

25 Suggestion mentioned in the text critical notes in Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (bhs) version.

26 Klaas Spronk, Nahum (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1997), 105.

27 Spronk, Nahum, 106.

28 Laurel Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" The Feminine and the Fantastic in the Book of Nahum (New York: T & T Clark, 2006), 80-100.

29 Cf. Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" 94-96.

30 Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" 96.

31 This phrase further occurs only in Jer 21:13; 23:30, 31, 32 50:31; 51:25 and Ezek 5:8; 13:8; 21:8; 26:3; 28:22; 29:3, 10; 30:22; 34:10; 35:3; 38:3 and 39:1.

32 Spronk, Nahum, 107 and Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" 96, who regards it as a challenge to combat.

33 Spronk, Nahum, 108.

34 Interestingly the change from masculine (דג) to feminine (דנה) also occurs in the book of Jonah.

35 Cf. Spronk, Nahum, 109.

36 Spronk, Nahum, 109 has discussed the various suggested amendments in detail.

37 Richard J. Coggins and S. Paul Re'emi, Israel Among the Nations: A Commentary on Nahum, Obadiah, Esther (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1985), 44.

38 Cf. Jim J. M. Roberts, Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah: A Commentary (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1991), 62; Spronk, Nahum, 104-105.

39 Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" 96.

40 Robertson, Books of Nahum, 95 regards it as a reference to the royalty of Nineveh.

41 Many attempts have been made to link the various lion categories to specific people or groups of people. Spronk, Nahum, 105-106 overviewed the various suggestions by scholars such as the royal family, the royal family, the nobles and the citizens. The young lions probably signify the nobles. Some see the lioness as referring to the queen and the cub to the royal prince. O'Brien, Nahum, 62 regards attempts to identify the various categories of lions with members of the royal family as forced.

42 Cf. Robertson, Books of Nahum, 96.

43 Gordon H. Johnston, "Nahum's Rhetorical Allusions to the Neo-Assyrian Lion Motif," BSac 158 (2001): 290; also Robertson, Books of Nahum, 95.

44 Gert T. M. Prinsloo, "Lions and Vines: The Imagery of Ezek 19 in the Light of Ancient Near-Eastern Descriptions and Depictions," OTE 12/2 (1999): 340-342. See also Johnston, "Nahum's Rhetorical Allusions," 287-307 who has done a comprehensive study of the lion motif in the ANE and in particular the book of Nahum.

45 Cf. Amos 1:12; 3:4, 8; Hos 4:14; 5:14-15; 13:7-8; Jer 49:9; Ps 50:22; Isa 38:13; Lam 3:10-11; also Isa 31:4 and Hos 11:10-11; Prinsloo, "Lions and Vines," 343-345.

46 Prinsloo, "Lions and Vines," 346.

47 Johnston, "Nahum's Rhetorical Allusions," 292-295.

48 Johnston, "Nahum's Rhetorical Allusions," 296-307.

49 Rudolph, Micha , 173 also mentions the fact that Assyrian kings have associated themselves with the lion symbol. He for example refers to Esarhaddon who said "Wie eine Lowe wütete ich."

50 Cf. Prinsloo, "Lions and Vines," 346.

51 Brent A. Strawn, What is Stronger than a Lion? Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East (Friboug: Academic Press Fribourg, 2005), 65.

52 Nikola Dobrić, "Theory of Names and Cognitive Linguistics - The Case of the Metaphor," Fil 21/1 (2010): 31-41.

53 Dobrić, "Theory of Names," 34.

54 In building on thoughts from Matthew S. McGlone, "What is the Explanatory Value of Conceptual Metaphor?" L&C 27/2 (2007): 109-126, Alec Basson, "'Rescue Me from the Young Lions': An Animal Metaphor in Psalm 35:17," OTE 21/1 (2008): 11 says ". . . conceptual metaphor theory suggests that our most highly structured experiences are with the physical world and the patters we encounter and develop through interaction of our bodies with the physical environment serve as our most basic source domains."

55 Dobrić, "Theory of Names," 34; also Mary T. DesCamp, Metaphor and Ideology: Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum and Literary Methods Through a Cognitive Lens (Lei-den: Brill, 2007), 21, who states that "Metaphor imposes structure on thinking, and allows one to reason about, not just talk about, one thing in terms of another." Hu-mans need metaphor to reason and speak about abstracts things in terms of concrete cognitive concepts.

56 Job Y. Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered: A Cognitive Approach to Poetic Prophecy in Jeremiah 1-24 (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2010), 21.

57 Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered, 21.

58 Basson, "'Rescue Me,"' 10-12 offers a brief but insightful discussion on conceptual metaphor theory.

59 Cf. Basson, "'Rescue Me,"' 11.

60 Roger Gill, Theory and Practice of Leadership (London: Sage Publications, 2011), 284.

61 Johnston, "Nahum's Rhetorical Allusions," 301.

62 O'Brien, Challenging Prophetic Metaphor, 150.

63 Timmer, "Boundaries Without Judah,"181-182.

64 Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" 96, 138-140.

65 Lanner, "Who Will Lament Her?" 140.

66 Rudolph, Micha, 173.

67 Rudolph, Micha, 174.

68 Johan Serfontein and Wilhelm J. Wessels, "Hearing the 'Good News' in the Book of Nahum: A Socio-Rhetoric Enquiry," JSem 22/1 (2013): 183.

69 Timmer, "Boundaries Without Judah," 180.

70 Cf. O'Brien, "Nahum-Habakkuk-Zephaniah," 176.

71 Cf. Aron Pinker, "Nahum - The Prophet and his Message," JBQ 33/2 (2005): 81, 88-90.

72 McConville, Exploring the Old Testament, 208.

73 Stulman and Kim, You are My People, 219.