Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Old Testament Essays

versión On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versión impresa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.27 no.2 Pretoria 2014

ARTICLES

Mysticism and understanding: Murmurs of meaning(fulness) - unheard silences of Psalm 11

Christo Lombaard

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

In this paper, two contributions are made. First, the aspect of faith impulses behind the text of Ps 1 are traced, also as an indication of this aspect being overlooked in recent research reviews on Psalter scholarship. Second, the seeming oversimplification of questions of theodicy in this Psalm is characterised here as not ignorance on the part of its author/s, but as taking a considered stance within a highly complex philosophical-theological debate within post-exilic Israel. Such a realisation however requires careful "listening" to the implied religious situation to which the text spoke, an exercise which is methodologically difficult, yet which is historically and theologically important.

A post-secularist paper.

Post-secularism: when relationality/relativity are no truer than the truths they reject.

A PSSST! THE SPIRITUAL PSALTER (OR: FOLLOW THE MONEY FAITH)

There is a strong tradition of reading Psalms for faith, that is, of reading the Bible "for all its worth"2 in popular religious circles. Despite personal a-religious commitments, at times pretenses, and the deep seated reservations inherent in modernism on the relationship between religion and academia,3 the popular interest in reading Psalms for faith is not always that far removed from what happens in research circles, though with a different configuration of motivations (which may for the moment be summarised by the famous "three publics" of theology indicated by Tracy).4 This intellectual interest in particularly the Psalter for more than purely exegetical reasons, but also with a view to the experiential, is indicated for instance by the four books on the spirituality of the Psalms that appeared in quick succession early in the new millennium.5 This however was no new turn, but was rather a return to earlier scholarship, with already some of the early critical sources such as Herder6 (1782/1783) and De Wette7 (1811) seeking to give expression to "the 'feeling' or 'spirit' of the Psalms."8

The historical search for the experiential life/faith world from which the Psalms came, and seeking the contemporary experiential life/faith world the Psalms interactively inspire in modern readers, have never quite been outside the ambit of Psalms scholarship. These two aspects of Biblical Spirituality- the ancient and the modern faith-text interaction, which is precisely the bifocal terrain of the discipline of Biblical Spirituality9-have however seldom received mainstream scholarly recognition

Recent research overviews of the Psalms for instance tend to focus on Psalm research having transformed into Psalter research,10 with the focus of the latter on the composition of the corpus as a whole rather than on single Psalms. The word "composition" here is ambiguous, which is in this case appropriate: these two trends in Psalms research, the earlier and the newer, reflect in some broad way11 still the earlier tension between historical-critical12 and canonical approaches13 to exegetical work. There is namely at the moment a kind of slightly awkward understanding in which it is accepted that the individual Psalms had had complicated growth histories, but that the Psalms book as is ought now to be the research focus. It turns out, however, that the Psalms collection had also had an involved history of editorial/redactional development. While some of these developments can be traced, it has become clear that, as is the case with all historical work, it will not be possible with precision to pinpoint all the evolutionary twists and turns of this corpus. The non-historical meaning of the term "composition" leaves open the possibility for scholars not interested in or disheartened by the diachronical approaches to study the Psalms compendium as collection.14

Across both approaches, however, a foreseeable15 broad consensus has developed that Ps 1 plays an introductory role to the Psalms as corpus.16 What exactly that introductory role is, however, remains open to question. Is it simply a fairly innocuous introductory "chapter" (along with Ps 2, or not)17 to a Book of 150 (or perhaps not)?18 Or is it a purposively designed, late, Torah theology addition to the collection-in-development in order to help cast the whole of the Book within its wake as holy law teaching, thus contributing to the process that moreover divided the Psalms collection into five sections following the pattern of the Pentateuch?19 The latter seems a more accurate characterisation, given the rising importance of Torah theology in Second Temple Judaism as one of the main competing theological currents within Persian period Judea, taking its cue from the kind of impetus we find described in Neh 8.20

There is a strong possibility that it is directly this religious impulse that lies behind both the composition of this Psalm and its placement as "Eingangsportal"21 to the Psalter. Although the opening Psalm has variously been characterised as, usually, wisdom, but also as for instance royal or benediction text,22 if the greater faith/life world (i.e. the post-exilic religious-social-cultural-political context) is taken into account, this is primarily a Psalm with an express theological intent. If we follow the faith, in this case, we find the heart of the Psalm - the impetus for its writing. Namely: within the intensely contestatory theological environment in which Ps 1 found its birth and place - or to misappropriate a phrase from modern terminology: within its atmosphere of "spiritual warfare" - with this Psalm, broadly, "the Torah became a kind of mediator between God and [humanity]";23 the placement of this psalm as opening verse to the Psalms book, implies the same characterisation for the collection as a whole.

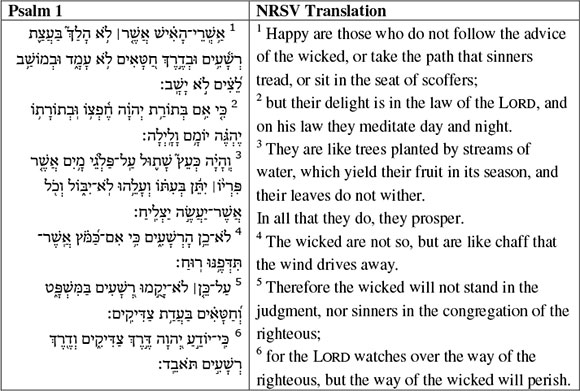

B PSALM 1: TEXT, TRANSLATION, THEOLOGY

Though this Psalm seems to present itself with a reasonably simple structure, the way in which the final form of Ps 1 has been pieced together clearly lies in the eye of the scholarly beholder.24 The central message of the text is that "there is no direct interaction between Yahweh and the righteous other than through the Torah,"25 and not the too easily assumed binary opposition between the righteous and the wicked. That "happiness means having the right spiritual relationship with Yahweh"26 is clearly specified: only by way of the Torah.

This message is not one-dimensionally a pious expression of an innocuous, agreed-upon spiritual conviction. It at once also expresses a contentious theological position, set over against other theological stances in an inner-religious arena of fluctuating possibilities within post-exilic Yahwism. In both senses of the term, this was spirited debate.

Although the two main exegetical problems related to Ps 1 had been its relation to Ps 2 and its nature as either a poetic or a prose text,27 there has been another, almost silenced matter that seems more difficult to deal with: the complete simplicity of its theological account28 en route to expressing its core message. How can it be that the challenging questions related to suffering, theodicy and a meaning-full existence seem to be glossed over, with Ps 1 offering an all too easy explanation of the good life?29 This is even more noticeable, given that the expressed view is one that we know from the debates within Wisdom literature that it would have been contentious.

My suggestion that this Psalm be understood as having an inherent, but not explicitly stated, educative intent30 has received fairly wide support,31 since it solved the problem of the seeming over-simplification of complex questions of theodicy in this Psalm. This is an understanding I keep to, but now within an expanded framework.

It has of late become increasingly clear that great parts of the OT texts were in the Persian period brought into deliberate discussion with one another, reflecting a post-exilic era of intense theo-socio-political contestation in and around Jerusalem.32 Such deliberations included the debate within wisdom theology on whether good things happened to good people and bad to bad, versus the more cynical, less retributive and non-determinative "Vergel-tungslehre"-view33 that actions and fate are not automatically correlated.34 This is a dispute that had been ongoing within ancient Israel, reflecting the same philosophical alternatives within the broader ancient Near East35 of - again to misappropriate currently popular terms - karma versus randomness.

The author/s of Ps 1 could not have been unaware of this debate:36 this Psalm is namely so drenched in the ambience of wisdom theology that it has in modern scholarship become the most frequent genre identification for this Psalm. The silence within the Ps 1 text on the underlying, implicit philosophical deliberations ought to be read charitably - not for any apologetic reasons on the part of modern readers, but for the sake of critical, historical scholarship. To assume from the silence on this debate within Ps 1 that its author/s had in some way been cut off from the broader discursive context (which found expression in e.g. Job, Ecclesiastes, and Deuteronomistic theology), would amount to less-than-thorough scholarship: what is unheard in the Psalm as we have it cannot be assumed to have been unheard of by its author/s. Methodologically precarious as it may be,37 the murmurs of ancient-contextu-ally implied meanings, which would have been understood implicitly by at least an important part of the intended post-exilic audience of Ps 1-by extension, also the audience of the now reinterpreted Psalter and more,38 with Ps 1 along with Pss 19, 119, and less frequently acknowledged as Torah Psalms, 137 and even 3 339 casting their reinterpretative net-must be included in our undertakings to understand this text more fully.40 We have to listen out for these murmurs of meaning, silently but materially embedded in the text, in order for us to understand more fully the intent and implications of this Psalm.

C THE TORAH WHISPERERS

The post-exilic Judean, inner-Yahwistic competition for theological influence and dominance had been both complex41 and intense.42 Within an involved matrix of contending theological currents, the Torah ideology pushed to the fore mainly though the identity constructing work of the priestly group (cf. Neh 8), which in time came either to dominate or to incorporate the rival religious constructs (or currents or, perhaps, schools).

Three of these now subsumed theologies are evident in the first Psalm:

(i) The long noticed amalgamation within Ps 1 of wisdom and Torah theologies is evidently the result of a mild kind of consolidation between these two, in which the new arrival (of Moshe-come-lately), Torah theology, incorporates the much older and much wider-spread wisdom stream.43 This is accomplished in Ps 1 by defining wisdom henceforth in Torah terms-a move that runs parallel to the process of inserting Yahwistic expressions into the Proverbs collection at that time.44 This theological union could never be fully successful, since law and wisdom entail two quite different ways of human co-existence. In addition, the divine mandate legitimising them is largely incompatible: with law, God's will is firmly and directly indicated; with wisdom, God is only vaguely, when at all, present in the background of accumulated, reflected-upon human experience. However, because Torah has also the implication of "teaching," which is close enough to the intent of all wisdom, the Torah-wisdom link was nevertheless strong enough for the bond to hold. Here in Ps 1, one instance among a few in respectively the Psalter and wisdom literature is found of Torah theology gathering wisdom under its wing.

(ii) The fact that quite a few Torah Psalms found their way into the final Psalms collection, with the magnum opus of Ps 119 being the last among them,45 indicates that the particular group editing the Psalms was both socially powerful enough and ideologically sufficiently committed to Torah theology to see this process through and then, ultimately, to canonise the result attained. As one instance of this editorial strategy: by placing Ps 1 at the front of the Psalms collection and by thus recasting the book as a whole as Torah, or at the very least as being under the light of the Torah, the temple liturgical service which most actively employed the Psalms is essentially brought under new management. Now, "[t]he law is God's Word and so is the Psalter."46 In this way, two at least parallel, but perhaps in some ways alternate theological currents - law and Psalms - are brought neatly under the fold of the former. Psalm talk becomes Torah talk.

(iii) There is however also a third subjugated theological stream present here, not referred to by name, but calculatingly implicated into compliance under the priests' now ever more presiding Torah theology. That is namely the prophetic group(s). Torah theology found itself in post-exilic Yahwism in contestation with the prophetic legacies on the most valid form in which God addressed Israel:47 indirectly, but more manifestly, through holy law, or by direct communication, though with less tangible results, through prophetic revelation? The underlying urgency stirring the debate is that the group - that is, the priests or the prophetic tradents - who are the carriers and/or guarantors of the most valid form divine communication - that is, written law or prophetic revelation -will in a society with strongly theocratic tendencies become the most powerful, socio-politically. In Ps 1 (as elsewhere), Torah trumps Prophecy. The subtle, dual manner in which this is done may, from the multiple references in Ps 1 to the Pentateuch and to the Prophets,48 for the moment be summarised as follows:

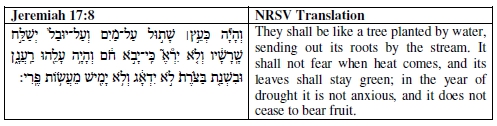

- Psalm 1 employs poetic imagery49 from Jer 17:850, but does not do so innocently. Psalm 1 namely places the positive tree-river-leaves-fruit language now not as the result of trusting in Yahweh, directly, but specifies a theological avenue: Torah piety.51 Not uninterceded interaction with Yahweh (à la the prophetic imagination), but a mediated spirituality, filtered through the Torah, elicits blessings. Thus, the preferred priestly way is, through the refined rhetorics of the first Psalm, put forward over against prophetic inclinations.

- Apart from placing itself over against prophetic theology by means of this subversive reception of its material, the Torah theology in Ps 1 also aligns itself with the Pentateuch by quoting with approval52 from, for instance, Josh 1:8.53 This meditation on the law, or in some interpretations: the continuous murmuring of the words from the Torah, is an expression of faith which stands in a direct line with the Torah spirituality put forward in Neh 8. By first setting this reference as the Torah centered faith model which should be aspired to (Ps 1:2) and by then altering the Jer reference in order to fit into this model (Ps 1:3), a sophisticated argument is built, namely by implication. The orthodox and not the charismatic, that is: explication and application of the Torah rather than direct divine intervention is henceforth principally to guide faith expression within ancient Israel.

The Torah Psalms are therefore no minor afterthought to the Psalms,54 but rather evidence an attempted reengineering of the extant, vying faith constellations within post-exilic Yahwism. In what seems from the outside to be a small, simple Psalm, we find contextually more accurately a major theological move being made. Psalm 1 is not a blatant "plea for obeying the written law";55 rather, we find in it whispered theological absorption, reinterpretation and refutation of alternatives (numbered i, ii, and iii above, respectively). Whispered, only for us; these messages would have been heard much more loudly and clearly within the time of its composition and incorporation into the Psalter.

Although it is possible still to discern inner world theological thinking in Ps 1,56 related to personal piety, more important to understanding this Psalm is the outer context to which it reacts - its life/faith world. The theology of the Psalm and its central message come alive most clearly when we perceive the alternate theological reflections against which Ps 1 expresses itself. Theology always has these two experiential aspects which make it valid for its context: the inner experience of faith and the outer impulses to which it in various ways reacts.

D SOMEWHAT MYSTIC METHODOLOGY

Although the point is well known that faith and reading the Scriptures in a scholarly fashion need not be divorced,57 the methodological move explicitly to search for faith impulses that had found their way into the ancient texts is much less commonly found. The unspoken and often quietly understood search by scholars for faith expressions in and from the Psalms has not disappeared;58 however, this aspect of scholarship seems never to be reflected on much in research overviews.

Conversely, such searches for faith impulses have become a constituent part of the young and still diminutive discipline of Biblical Spirituality.59 Not to be confused with the pre-scientific, a- or anti-critical, and a- or anti-historical sentiments that are often popularly assumed of the term "spirituality," rather, within this academic discipline, it is precisely via these scholarly avenues that new insights can be suggested, as had been attempted above with Ps 1. Thus, exegesis becomes at once more historical and more spiritual: not only the usual analytical and interpretative work on the textual and historical aspects of a text is undertaken, but even more is required. Now also included is the scholarly search for faith impulses and their effects.

In the previous broad cultural phases in Western(ised) societies of modernism and post-modernism, this kind of scholarly search had been difficult:60 within modernism, faith/spirituality had because of its kind of truth claims often been afforded no proper or a foundationally questionable intellectual place; within post-modernism, faith/spirituality additionally had because of its assigned languaged nature been afforded less than reasonable existential validity. Within the Bible sciences the genres of scholarship of Theology and History of Religion had in some ways tried to fill the felt vacuum on reconstructing in some ways the faith of ancient Israel. Now, though, in the currently unfolding broad cultural phase of post-secularism, in which faith/spirituality is no more or no less intellectually respectable than other expressions of the human condition, there is no reason that the study of faith in its experiential form should not be advanced.

Methodologically, much development is required on this route. To put in scholarly terms, to the highest intellectual standards, aspects such as spiritual experience - the ways in which faith impulses are internalised and given expression to - and mystic encounter - the peak experience of finding oneself in an unmediated (or less mediated) engagement with the Ultimate - will require a different kind of rigour-and-flexibility. Some strides have been made, with for instance Waaijman's work on methodology in the study of Spirituality61 and with Kourie's work in relation to Mysticism and the Bible.62 However, a good fit between the methodological precision of Exegesis and the methodological abstraction required of Spirituality Studies has yet to be found.63 For Exegesis to adopt Spirituality's sensitive language for formulating the nature of a faith expression encountered behind a biblical text, as it is manifested interactively within the text itself and in its historical context, is as demanding as it is for Spirituality Studies through critical-comparative and other analytical tools to put the elusive yet at once ever-present phenomenon it engages with into more than appreciative terms. Different kinds of intellectual resonance are at work. How do we bring such dissimilar scholarly registers closer together?

Cupitt64 believes that all mystic experiences from the past can only be accessed in mediated form, that is, via texts. The validity of this point hinges to some extent on the penchant within post-modernism to relate everything to language (this, after the disillusionment within modernism that everything cannot after all be related to an unfettered mind). There is however more to a spiritual experience or mystic encounter than the text that reports it. There had indeed been something there, behind the text, a life occurrence of such substance on its own that it led, secondarily, to the creation of a text. It is in these deeply meaningful life occurrences that primary experiences of the divine are found. There is more to such a God experience than only the text from it.

In this respect, examining religiosity/spirituality/mysticism is not unlike other aspects of historical study, namely that the occurrences lie irrevocably behind us, and beyond us, in a way that they cannot be resuscitated, recuperated, revived, relived. To have in any way at all access to such events - and then still by non-direct means - requires imaginative historical inquiry, based on a living into / feeling oneself into the past65 through well-informed spiritual empathy.66 Along with other factors such as phenomenological parallels and analogies between the ancient context and ours, thorough consideration of philosophical hermeneutics, the (though per definition stretched) experienced historical continuation of the same faith stream across time, informed historical imagination can in some ways internalise the ancient within the contemporary, from where it can be actualised (always with great circumspection) within the present.

Most people reading a holy text for all its worth regularly engage in exactly that almost-impossibility, independent of from within whichever of the naïvetés it is done. To experience in some way a community of faith, or even a communion of faith across the ages, communicated behind, in and via the holy texts,67 remains always both profound and fleeting.68 Not to romanticise the dynamics of such an event: such experiences should not be taken always to be incidences of coherence (faith remains more active than usual when under criticism or threat - cf. Ps 1 as read above) or of clarity (faith usually involves more questions than answers). The existential encounter with a text, with the holiness event that may lie behind it, and with the God of that event, is however of such significance that scholarship ought to take the uncertain steps now also to investigate those experiences and their consequences, ancient and contemporary.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamo, David. "Reading Psalm 109 in African Christianity." Old Testament Essays 21/3 (2008): 575-92. [ Links ]

Albertz, Rainer. Vom Exil bis zu den Makkabäern. Volume 2 of Religionsgeschichte Israels in alttestamentlicher Zeit. Supplements to Das Alte Testament Deutsch / Grundrisse zum Alten Testament 8/2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992. [ Links ]

Auffret, Pierre. "Comme un Arbre... Etude Structurelle du Psaume 1." Biblische Zeitschrift 45/2 (2001): 256-64. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. Spirituality of the Psalms. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002. [ Links ]

Barbiero, Gianni. Il regno di JHWH e del suo Messia: Salmi Scelti dal Primo Libro del Salterio. Roma: Città Nuova, 2008. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil. "Interpreting 'Torah' in Psalm 1 in the Light of Psalm 119." HTS Teologiese Studies /HTS Theological Studies 68/1 (2012): 7 pages. DOI: 10.4102/hts.v68i1.1274. [ Links ]

______. "Intertextuality and the Interpretation of Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 18/3 (2005): 503-20. [ Links ]

______. "The Ideological Interface Between Psalm 1 and Psalm 2." Old Testament Essays 18/2 (2005): 189-203. [ Links ]

______. "The Junction of the Two Ways: The Structure and Theology of Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 4 (1991): 381-96. [ Links ]

Botha, Phil and Henk Potgieter. "'The Word of Yahweh is Right': Psalm 33 as a Torah-Psalm." Verbum et Ecclesia 31/1 (2010): 8 pages. DOI: 10.4102/ve .v31i1.431 [ Links ]

Childs, Brevard. Introduction to the Old Testament as Scripture. London: SCM, 1979. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James. Old Testament Wisdom: An Introduction. 3rd ed. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010. [ Links ]

Cupitt, Don. Mysticism after Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1998. [ Links ]

De Wette, Wilhelm. Commentar über die Psalmen. Heidelberg: Mohr & Zimmer, 1811. [ Links ]

Fee, Gordon and Douglas Stuart. How to Read the Bible for all its Worth: A Guide to Understanding the Bible. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003. [ Links ]

Firth, David. Hear, o Lord: A Spirituality of the Psalms. Calver: Cliff College Publishing, 2005. [ Links ]

______. "The Teaching of the Psalms." Pages 159-174 in Interpreting the Psalms: Issues and Approaches. Edited by David Firth and Philip Johnston. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2005. [ Links ]

Gericke, Jaco. The Hebrew Bible and Philosophy of Religion. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2012. [ Links ]

Gosse, Bernard. "Le Livre des Proverbes, la Sagesse, la Loi et le Psautier." Etudes Théologiques et Religieuses 81 (2006): 387-94. [ Links ]

Grogan, Geoffrey. Psalms. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008. [ Links ]

Gunkel, Hermann. Die Psalmen. 5th ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, 1968. [ Links ]

Helberg, Jaap. "Die Bron van Lewensvreugde volgens Psalm 1 en wat dit vir Gereformeerde Prediking Inhou." In die Skriflig 43/4 (2009): 841-59. [ Links ]

Herder, Johann. Vom Geist der ebräischen Poesie: Eine Anleitung für die Liebhaber derselben und der ältesten Geschichte des menschlichen Geistes. Dessau: Buchhandlung der Gelehrten, 1783. [ Links ]

Human, Dirk. "Psalms and Canon in the Hebrew Bible." Paper presented at the annual Pro Psalms Conference, University of Pretoria, 29-30 August 2013. [ Links ]

Knoppers, Gary N. and Bernard M. Levinson. "How, When, Where and Why Did the Pentateuch Become Torah?" Pages 1-19 in The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding its Promulgation and Acceptance. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007. [ Links ]

Kraus, Hans-Joachim. Geschichte der historisch-kritischen Erforschung des Alten Testaments. 3rd, reworked ed. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1982. [ Links ]

Kriegshauser, Laurence. Praying the Psalms in Christ. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Kourie, Celia E. T. "Mysticism: a Way of Unknowing." Pages 59-75 in The Spirit that Empowers: Perspectives on Spirituality. Acta Theologica Supplementum 11. Edited by Pieter de Villiers, Celia E. T. Kourie and Christo Lombaard. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State Press, 2008. [ Links ]

______. "Transformative Symbolism in the New Testament." Myth & Symbol 3 (1998): 3-24. [ Links ]

Kynes, Will. My Psalm has Turned into Weeping: Job's Dialogue with the Psalms. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2012. [ Links ]

Le Roux, Jurie. "Historical Understanding and Rethinking the Foundations." HTS Teologiese Studies /HTS Theological Studies 63/3 (2007): 983-98. [ Links ]

Lombaard, Christo. "The Word or the Word? The Divine Experience as Mediated or Direct - A Perspective from Biblical Spirituality." Keynote address at the "Religious Experience and Tradition International Interdisciplinary Conference," Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 11-12 May 2012; Presented in altered form at the Annual General Meeting of the Spirituality Association of South Africa, Pretoria, 31 January 2013. Publication forthcoming, 2014. [ Links ]

______. "'Let's get Together and Feel All Right' (Bob Marley - 'One Love'): A Response to Prof. Dirk van der Merwe." 5 Pages. Cited 5 Nov. 2013. Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10500/13541. [ Links ]

______. "Getting Texts to Talk: A Critical Analysis of Attempts at Eliciting Contemporary Messages from Ancient Holy Books as Exercises in Religious Communication." Paper presented at the 11th Annual International Conference on Communication and Mass Media, Athens Institute for Education and Research, Greece, 13-16 May 2013. Publication forthcoming: Ned. Geref. Teologiese Tydskrif, 2014. [ Links ]

______. "Dating and Debating: Late Patriarchs and Early Canon." Paper presented at the 21st congress of The International Organisation for the Study of the Old Testament, Munich, 4-9 August 2013. Publication forthcoming: Scriptura, 2014. [ Links ]

______. The Old Testament and Christian Spirituality: Theoretical and Practical Essays from a South African Perspective. International Voices in Biblical Studies 2. [ Links ]

Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2012. [ Links ]

______. "Biblical Spirituality and JH Eaton." Verbum et Ecclesia 33/1 (2012): 5 pages. DOI: 10.4102/ve.v33i1.685. [ Links ]

______. "Biblical Spirituality, the Psalms, and Identification with the Suffering of the Poor: A Contribution to the Recent African Discussion on Psalm 109." Scriptura 110 (2012): 273-81. [ Links ]

______. "Having Faith in the University? Aspects of the Relationship Between Religion and the University." Pages 49-65 in Faith, Religion and the Public University. Acta Theologica Supplementum 14. Edited by Rian Venter. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State Press, 2011. [ Links ]

______. "Biblical Spirituality and Interdisciplinarity: The Discipline at Cross-Methodological Intersection." Religion & Theology 18 (2011): 211-25. [ Links ]

______. "Fleetingness and Media-ted Existence: From Kierkegaard on the Newspaper to Broderick on the Internet." Communicatio 35/1 (2009): 17-29. [ Links ]

______. "Elke Vertaling is 'n Vertelling: Opmerkings oor Vertaalteorie, Geïllustreer aan die Hand van die Chokmatiese Ratio Interpretations." Old Testament Essays 15/3 (2002): 754-65. [ Links ]

______. "By implication: Didactical strategy in Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 12/3 (2000): 506-14. [ Links ]

McCann, Clinton. "The Shape of Book I of the Psalter and the Shape of Human Happiness." Pages 340-48 in The Book of Psalms: Composition & Reception. Edited by Peter Flint and Patrick Miller. Leiden: Brill, 2005. [ Links ]

______. A Theological Introduction to the Book of Psalms: The Psalms as Torah. Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Mowinkel, Sigmund. The Psalms in Israel's Worship. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004. [ Links ]

Otto, Eckart. "Scribal Scholarship in the Formation of Torah and Prophets: A Postexilic Scribal Debate between Priestly Scholarship and Literary Prophecy - the Example of the Book of Jeremiah and its Relation to the Pentateuch." Pages 171-84 in The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding its Promulgation and Acceptance. Edited by Gary Knoppers and Bernard Levinson. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem. Van Kateder tot Kansel: 'n Eksegetiese Verkenning van Enkele Psalms. Pretoria: NG Kerkboekhandel, 1988. [ Links ]

Richter, Wolfgang. Exegese als Literaturwissenschaft: Entwurf einer alttestamentliche Literaturtheorie und Methodologie. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1971. [ Links ]

Sæbø, Magne. Sprüche. Das Alte Testament Deutsch 16/1. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012. [ Links ]

Scheffler, Eben. "Pleading Poverty (or Identifying with the Poor for Selfish Reasons): on the Ideology of Psalm 109." Old Testament Essays 24/1 (2011): 192-207. [ Links ]

Snyman, Fanie. "Suffering in Post-Exilic Times - Investigating Maleagi 3:13-24 and Psalm 1." Old Testament Essays 20/3 (2007): 786-97. [ Links ]

Stuhlmueller, Carroll. The Spirituality of the Psalms. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2002. [ Links ]

Tracy, David. The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism. New York: Crossroad, 1981. [ Links ]

Terrien, Samuel. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2003. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, Jan. "Biblical Spirituality: Spirituality in Two Early Christian Communities." Guest lecture at the Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 5 November 2013. [ Links ]

Veldsman, Daniel P. "Diep Snydende Vrae, met Antwoorde Gebore uit Weerloosheid: N.a.v. Jurie le Roux se 'Spirituele Empatie.'" Verbum et Ecclesia 34/2 (2013). 7 pages. DOI: 10.4102/ve.v34i2.786. [ Links ]

Vos, Cas. Theopoetry of the Psalms. Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2005. [ Links ]

Waaijman, Kees. Mystiek in de Psalmen. Baarn: Ten Have, 2004. [ Links ]

______. Grundlagen. Volume 2 of Handbuch der Spiritualität. Mainz: Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, 2000. [ Links ]

Waltke, Bruce and James Houston. The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010. [ Links ]

Walton, John. "Retribution." Pages 647-55 in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. Edited by Tremper Longman and Peter Enns. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008. [ Links ]

Weber, Beat. "Von der Psaltergenese zur Psaltertheologie: der nächste Schritt der Psalterexegese?! Einige grundsätzliche Überlegungen zum Psalter als Buch und Kanonteil." Pages 733-44 in The Composition of the Book of Psalms. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum theologicarum Lovaniensium 238. Edited by Erich Zenger. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

______. Die Psalmen 1 bis 72. Volume 1 of Werkbuch Psalmen. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001. [ Links ]

Welzen, Huub. "Contours of Biblical Spirituality as a Discipline." Pages 37-60 in The Spirit that Inspires: Perspectives on Biblical Spirituality. Acta Theologica Supplementum 15. Edited by Pieter de Villiers and Lloyd Pietersen. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Wenham, Gordon. Psalms as Torah: Reading Biblical Song Ethically. Studies in Theological Interpretation. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012. [ Links ]

Yarchin, William. "Is There an Authoritative Shape for Sefer Tehillim? Profiling the Manuscripts of the Hebrew Psalter." Paper presented at the Sixteenth World Congress of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem, 28 July-1 August 2013. [ Links ]

Zenger, Erich. "Psalmenexegese und Psalterexegese: Eine Forschingsskizze." Pages 1765 in The Composition of the Book of Psalms. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum theologicarum Lovaniensium 238. Edited by Erich Zenger. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2010. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Christo Lombaard

Is Professor of Christian Spirituality at the University of South Africa

P.O. Box 392, Unisa, Pretoria, 0003, South Africa

E-mail: ChristoLombaard@gmail.com

1 I am honoured herewith to contribute to the Festschrift for Harry van Rooy, one of the leaders in Old Testament and cognate studies in South Africa. He has for me personally been an example in many ways, and I wish herewith to honour him for the ways in which he has led through his example the next generations of scholars.

2 Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for all its Worth: a Guide to Understanding the Bible (3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003).

3 Cf. Christo Lombaard, "'Let's get Together and Feel All Right' (Bob Marley -'One Love'): A Response to Prof. Dirk van der Merwe," 5 pages. Cited 5 November 2013. Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10500/13541; and Christo Lombaard, "Having Faith in the University? Aspects of the Relationship between Religion and the University," in Faith, Religion and the Public University (AcTSup 14; ed. Rian Venter; Bloemfontein: University of the Free State Press, 2011), 49-65.

4 David Tracy, The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism (New York: Crossroad, 1981), 3-46.

5 Carroll Stuhlmueller, The Spirituality of the Psalms (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2002); Walter Brueggemann, Spirituality of the Psalms (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002); Kees Waaijman, Mystiek in de Psalmen (Baarn: Ten Have, 2004); David Firth, Hear, o Lord: A Spirituality of the Psalms (Calver: Cliff College Publishing, 2005); cf. Christo Lombaard, The Old Testament and Christian Spirituality: Theoretical and Practical Essays from a South African Perspective (IVBS 2; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2012), 53-82.

6 Johann G. Herder, Vom Geist der ebräischen Poesie: Eine Anleitung für die Liebhaber derselben und der ältesten Geschichte des menschlichen Geistes (Dessau: Buchhandlung der Gelehrten, 1783).

7 Wilhelm De Wette, Commentar über die Psalmen (Heidelberg: Mohr & Zimmer), 1811.

8 Christo Lombaard, "Biblical Spirituality and JH Eaton," VetE 33/1 (2012): 4.

9 Cf. Huub Welzen, "Contours of Biblical Spirituality as a Discipline," in The Spirit that Inspires: Perspectives on Biblical Spirituality (AcTSup 15; ed. Pieter G. R. de Villiers and Lloyd K. Pietersen; Bloemfontein: University of the Free State Press, 2011), 37-60 for a succinct overview.

10 Cf. Dirk Human, "Psalms and Canon in the Hebrew Bible" (paper presented at the annual Pro Psalms Conference, University of Pretoria, 29-30 August 2013); Erich Zenger, "Psalmenexegese und Psalterexegese: Eine Forschingsskizze," in The Composition of the Book of Psalms (BETL 238; ed. Erich Zenger; Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2010), 24-30.

11 So too Beat Weber, "Von der Psaltergenese zur Psaltertheologie: Der nachste Schritt der Psalterexegese?! Einige grundsatzliche Uberlegungen zum Psalter als Buch und Kanonteil," in The Composition of the Book of Psalms (BETL 238; ed. Erich Zenger; Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2010), 734.

12 E.g. Hans-Joachim Kraus, Geschichte der historisch-kritischen Erforschung des Alten Testaments (3rd reworked ed.; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1982).

13 Most famously, Brevard Childs, Introduction to the Old Testament as Scripture (London: SCM, 1979); related directly the Psalms, cf. e.g. Wolfgang Richter, Exegese als Literaturwissenschaft: Entwurf einer alttestamentliche Literaturtheorie und Methodologie (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1971); and Willem Prinsloo, Van Kateder tot Kansel: 'n Eksegetiese Verkenning van Enkele Psalms (Pretoria: NG Kerkboekhandel, 1988).

14 E.g. Gordon Wenham, Psalms as Torah: Reading Biblical Song Ethically (STI; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012).

15 Cf. Bruce Waltke and James Houston, The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010), 118.

16 Beat Weber, Die Psalmen 1 bis 72 (vol. 1 of Werkbuch Psalmen; Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001), 3; cf. Phil Botha, "Intertextuality and the Interpretation of Psalm 1," OTE 18/3 (2005): 503, following e.g. Clinton McCann, "The Shape of Book I of the Psalter and the Shape of Human Happiness," in The Book of Psalms: Composition

& reception (ed. Peter W. Flint and Patrick D. Miller; Leiden: Brill, 2005), 341.

17 Cf. e.g. Phil Botha, "The Ideological Interface Between Psalm 1 and Psalm 2," OTE 18/2 (2005): 189-92.

18 Cf. William Yarchin, "Is There an Authoritative Shape for Sefer Tehillim? Profiling the Manuscripts of the Hebrew Psalter," (paper presented at the "Sixteenth World Congress of Jewish Studies," Jerusalem, 28 July - 1 August 2013).

19 Cf. e.g. Weber, "Von der Psaltergenese," 737.

20 Lombaard, Old Testament, 124-5.

21 Weber, Psalmen I, 3.

22 Cas Vos, Theopoetry of the Psalms (Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2005), 56; Sigmund Mowinkel, The Psalms in Israel's Worship (Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004), xxxii; Waltke and Houston, The Psalms, 120; Weber, Psalmen I, 1; Hermann Gunkel, Die Psalmen (5th ed.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, 1968), 1.

23 Phil Botha, "The Junction of the Two Ways: the Structure and Theology of Psalm 1," OTE 4 (1991): 394.

24 Cf. e.g. Gunkel, Psalmen, 1; Pierre Auffret, "Comme un arbre... Etude structurelle du psaume 1," BZ 45/2 (2001): 256-64 and Waltke and Houston, The Psalms, 132; Samuel Terrien, The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003), 701; and Jaap Heiberg, "Die Bron van Lewensvreugde Volgens Psalm 1 en wat dit vir Gereformeerde Prediking Inhou," IDS 43/4 (2009): 842 list more; Botha, "Junction," 383-91 presents the most thoroughgoing analysis in this respect.

25 Botha, "Junction," 394.

26 Vos, Theopoetry, 53.

27 Botha, "Junction," 381.

28 Cf. Terrien, The Psalms, 75-6; Helberg, "Die Bron," 844.

29 E.g. Weber, Psalmen I, 4.

30 Christo Lombaard, "By Implication: Didactical Strategy in Psalm 1," OTE 12/3 (2000): 506-14.

31 E.g. Will Kynes, My Psalm has Turned into Weeping: Job's Dialogue with the Psalms (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2012), 158; Gianni Barbiero, Il Regno di JHWH e del suo Messia: Salmi Scelti dal Primo Libro del Salterio (Roma: Citta Nuova, 2008), 45; David Firth, "The Teaching of the Psalms," in Interpreting the Psalms: Issues and Approaches (ed. David G. Firth and Philip S. Johnston; Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 169; perhaps Vos, Theopoetry, 56, 58?

32 Cf. e.g. Christo Lombaard, "The Word or the Word? The Divine Experience as Mediated or Direct - a Perspective from Biblical Spirituality" (keynote address at the "Religious Experience and Tradition International Interdisciplinary Conference," Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 11-12 May 2012; presented in altered form at the Annual General Meeting of the Spirituality Association of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 31 January 2013; publication forthcoming, 2014); drawing on Eckart Otto, "Scribal Scholarship in the Formation of Torah and Prophets: a Postexilic Scribal Debate between Priestly Scholarship and Literary Prophecy - the Example of the Book of Jeremiah and its Relation to the Pentateuch," in The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding its Promulgation and Acceptance (ed. Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007), 17184; Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson, "How, When, Where and Why did the Pentateuch Become Torah?" in The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding its Promulgation and Acceptance (ed. Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007), 13; and others.

33 Gunkel, Psalmen, 1.

34 Cf. John Walton, "Retribution," in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings (ed. Tremper Longman III and Peter E. Enns; Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008), 647-55.

35 Cf. e.g. James Crenshaw, Old Testament Wisdom: An Introduction (3rd ed.; Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 23-39, 251-72.

36 Cf. Clinton McCann, A Theological Introduction to the Book of Psalms: The Psalms as Torah (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993), 34-5.

37 Cf. Christo Lombaard, "Biblical Spirituality and Interdisciplinarity: The Discipline at Cross-Methodological Intersection," R&T 18 (2011): 211-25 for a broader methodological context.

38 Cf. e.g. McCann, Theological Introduction, 40.

39 Phil Botha and Henk Potgieter, "'The Word of Yahweh is Right': Psalm 33 as a Torah-Psalm," VetE 31/1(2010): 1-8; DOI: 10.4102/ve.v31i1.431.

40 For this reason, the increasing importance too of understanding for instance the philosophical frameworks-cf. e.g. Jaco Gericke, The Hebrew Bible and Philosophy of Religion (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2012), 243-451-within which the ot texts spoke.

41 Christo Lombaard, "Dating and Debating: Late Patriarchs and Early Canon," (paper presented at the 21st congress of the International Organisation for the Study of the Old Testament, Munich, 4-9 August 2013; publication forthcoming: Scriptura, 2014).

42 Lombaard, "The Word," 2014.

43 Cf. Bernard Gosse, "Le Livre des Proverbes, la Sagesse, la Loi et le Psautier," ETR 81 (2006): 387-94.

44 Christo Lombaard, "Elke Vertaling is 'n Vertelling: Opmerkings oor Vertaalteorie, Geïllustreer aan die Hand van die Chokmatiese Ratio Interpretations," OTE 15/3 (2002): 756.

45Phil Botha, "Interpreting 'Torah' in Psalm 1 in the Light of Psalm 119," HvTSt 68/1 (2012); Art. #1274, 7 pages; DOI 10.4102/hts. v68i1.1274.

46 Geoffrey Grogan, Psalms (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008), 42 .

47 Cf. e.g. Otto, "Scribal Scholarship," 171-84; Knoppers and Levinson "How?" 13.

48 Cf. e.g. Fanie Snyman, "Suffering in Post-Exilic Times - Investigating Maleagi 3:13-24 and Psalm 1," OTE 20/3 (2007): 786-97; Vos, Theopoetry, 57; Botha, "Interpreting," 1; Gunkel, Psalmen, 3.

49 Cf. e.g. Gunkel, Psalmen, 3.

50

51 Cf. Rainer Albertz, Vom Exil bis zu den Makkabäern (vol. 2 of Religionsgeschichte Israels in alttestamentlicher Zeit; ATDSup / GAT 8/2; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992), 623-33; Magne Sæbø, Sprüche (ATD 16/1; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012), 104.

52 Laurence Kriegshauser, Praying the Psalms in Christ (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), 14.

53

54 McCann, A Theological Introduction to the Book of Psalms, 25.

55 Terrien, The Psalms, 75.

56 McCann, Theological Introduction, 27.

57 E.g. Weber, "Von der Psaltergenese," 743-44.

58 Cf. e.g. Christo Lombaard, "Biblical Spirituality, the Psalms, and Identification with the Suffering of the Poor: A Contribution to the Recent African Discussion on Psalm 109," Scriptura 110 (2012): 273-81, on David Adamo, "Reading Psalm 109 in African Christianity," OTE 21/3 (2008): 575-92 and Eben Scheffler, "Pleading Poverty (or Identifying with the Poor for Selfish Reasons): On the Ideology of Psalm 109," OTE 24/1 (2011): 192-207.

59 Cf. Welzen, "Contours," 37-60.

60 The analysis offered here is freely acknowledged as being too brief; the ideas summarised here will be explored more fully elsewhere.

61 Kees Waaijman, Grundlagen (vol. 2 of Handbuch der Spiritualität; Mainz: Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, 2000), 239-95.

62 E.g. Celia E. T. Kourie, "Mysticism: A Way of Unknowing," in The Spirit that Empowers: Perspectives on Spirituality (AcTSup 11; ed. Pieter de Villiers, Celia E. T. Kourie, and Christo Lombaard; Bloemfontein: University of the Free State Press, 2008), 59-75; Celia E. T. Kourie, "Transformative Symbolism in the New Testament," M&S 3 (1998): 3-24.

63 Lombaard, "Spirituality and Interdisciplinarity," 211-25.

64 Don Cupitt, Mysticism after modernity (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1998), 60; cf. Jan van der Watt, "Biblical Spirituality: Spirituality in Two Early Christian Communities," (guest lecture at the Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 5 November 2013).

65 Cf. e.g. Jurie le Roux, "Historical Understanding and Rethinking the Foundations," HvTSt 63/3 (2007): 983-98.

66 Cf. Daniël P. Veldsman, "Diep Snydende Vrae, met Antwoorde Gebore uit Weerloosheid: N.a.v. Jurie le Roux se 'Spirituele Empatie,'" VetE 34/2 (2013): 3-4; DOI: 10.4102/ve.v34i2.786.

67 Cf. Christo Lombaard, "Getting Texts to Talk: A Critical Analysis of Attempts at Eliciting Contemporary Messages from Ancient Holy Books as Exercises in Religious Communication" (paper presented at the 11th Annual International Conference on Communication and Mass Media, Athens Institute for Education and Research, Greece, 13-16 May 2013. Publication forthcoming: Ned. Geref. Teologiese Tydskrif, 2014).

68 Cf. Christo Lombaard, "Fleetingness and Media-ted Existence: From Kierkegaard on the Newspaper to Broderick on the Internet," Communicatio 35/1 (2009): 17-29.